Abstract

Pneumatic Artificial Muscles (PAMs) are soft actuators that mimic the contractile behavior of biological muscles through fluid-driven deformation. Originating from McKibben’s 1950s braided design, PAMs have evolved into a diverse class of actuators, offering high power-to-weight ratios, compliance, and safe human interaction, with applications spanning rehabilitation, assistive robotics, aerospace, and adaptive structures. This review surveys recent developments in actuation mechanisms and applications of PAMs. Traditional designs, including braided, pleated, netted, and embedded types, remain widely used but face challenges such as hysteresis, limited contraction, and nonlinear control. To address these limitations, researchers have introduced non-traditional mechanisms such as vacuum-powered, inverse, foldable, origami-based, reconfigurable, and hybrid PAMs. These innovations improve the contraction range, efficiency, control precision, and integration into compact or untethered systems. This review also highlights applications beyond conventional biomechanics and automation, including embodied computation, deployable aerospace systems, and adaptive architecture. Collectively, these advances demonstrate PAMs’ expanding role as versatile soft actuators. Ongoing research is expected to refine material durability, control strategies, and multifunctionality, enabling the next generation of wearable devices, soft robots, and energy-efficient adaptive systems.

1. Introduction

Pneumatic Artificial Muscles (PAMs) are a class of soft actuators that mimic the contractile behavior of natural muscles through pressurized deformation [,,,,]. Initially inspired by McKibben’s 1950s braided bladder design [], PAMs have evolved into a broad family of actuators used in fields ranging from rehabilitation and assistive robotics [,,,] to aerospace [,,], embodied computation [] and kinetic arts []. PAMs provide a distinctive blend of high power-to-weight performance, compliance, and safe interaction with humans, advantages not easily achieved with traditional rigid actuators.

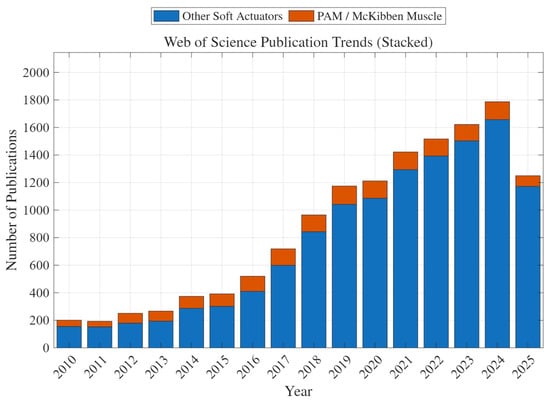

Recent bibliometric analysis of publication trends from the Web of Science [] indicates a substantial overall rise in research related to soft actuator technologies since 2010. The annual number of publications referencing “soft actuators” increased more than six times, from approximately 200 in 2010 to over 1700 in 2024, reflecting the field’s rapid diversification and interdisciplinary growth. In comparison, publications specifically referencing “Pneumatic Artificial Muscles” or “McKibben muscles” show a steady level of activity since around 2017, averaging about 120–130 papers per year. This pattern, illustrated in Figure 1, shows that while overall interest in soft actuators continues to grow, PAM research has remained steady and continues to be an important topic within the field.

Figure 1.

Annual publication trends (2010–September 2025) for soft actuators and pneumatic artificial muscle (PAM) actuators, based on Web of Science data.

Alongside this surge in scientific output, the design space of pneumatic artificial muscles has expanded significantly. Traditional PAMs, typically actuated by compressed air or hydraulic fluids, have long been established in industrial and biomechanical applications [,,,]. However, recent years have seen rapid expansion in design and functionality. Researchers have developed non-traditional actuation methods such as vacuum-driven systems [,,,,], foldable [,,] and origami-based geometries [,,,], inverse actuation modes [,], and hybrid configurations [,,]. These innovations have improved contraction strain, hysteresis, and actuation bandwidth, enabling PAMs to expand into new domains such as deployable aerospace structures, reconfigurable robots, portable wearables, and complex shape-morphing soft systems.

Recent reviews have examined multiple aspects of pneumatic artificial muscles (PAMs), including modeling, control, and application developments, such as the force modeling and classification review [], the material- and geometry-based comparison of linear PAMs [], the survey of soft pneumatic actuator architectures and constitutive modeling [], the system-integration perspective of PAM-driven robotic platforms [], and the optimization-based modeling framework []. A bibliometric review [] further assessed global research trends across 1743 papers and 1925 patents, identifying leading contributors and emerging materials such as shape memory alloys (SMAs), carbon nanotubes (CNTs), and graphene.

However, a systematic gap remains in categorizing recent PAM actuation principles and evaluating their influence on emerging multidisciplinary applications. This review addresses this gap through a comprehensive analysis structured along two main axes: (1) advances in actuation mechanisms, covering conventional pneumatic and novel vacuum-driven, hybrid, and reconfigurable models; and (2) their applications across established domains such as robotics, prosthetics, and rehabilitation, as well as emerging areas including morphing aerodynamics and soft bio-inspired systems. Through a systematic comparison of technologies and performance trade-offs, this work provides a comprehensive framework to guide future PAM design and implementation across disciplines.

2. Actuation Mechanisms

Based on their operating principles, PAMs can be broadly classified into traditional and non-traditional actuation mechanisms.

2.1. Traditional Actuation Mechanisms

Traditional actuation mechanisms for artificial muscles rely primarily on pneumatic or hydraulic systems. The core principle involves inflating an elastic bladder surrounded by a braided mesh, which contracts longitudinally and expands radially when pressurized, mimicking the contraction of biological muscles. This section outlines the fundamental pneumatic and hydraulic mechanisms that form the basis of most practical artificial muscle designs.

2.1.1. Pneumatic Artificial Muscles (PAMs)

Compressed air is the most widely used actuation medium in PAM systems. A typical setup includes an air compressor and a pressure regulation circuit that delivers controlled airflow to the actuator through valves []. Based on their construction and operating principles, PAMs are categorized into braided, pleated, netted, and embedded muscle actuators [,]. Among these, the braided type, patented in the early 1950s [], remains the most widely adopted configuration due to its high specific power, low weight, and biomimetic contraction characteristics.

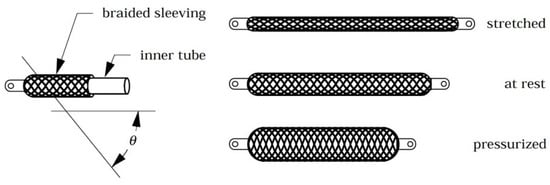

A McKibben muscle consists of an elastic inner bladder enclosed by a helically braided sleeve, typically woven at a pitch angle with respect to the actuator axis, as shown in Figure 2. When internal pressure increases, the bladder expands radially and exerts pressure on the inextensible braid, which transforms the circumferential expansion into axial contraction. The axial force F can be expressed by the geometrical form of the virtual work principle [,]:

where is the muscle diameter at rest and P is the internal pressure. The nonlinear term captures the geometric coupling between the braid angle and the contraction behavior. As decreases from approximately 45° to 20°, the axial contraction ratio increases, but the available output force decreases [,]. Experimentally, an optimal range of 25°–30° provides balanced force and stroke characteristics, yielding contractions of 20–30% under 400–600 kPa.

Figure 2.

Schematic of the McKibben-type pneumatic artificial muscle [].

Despite its simplicity, the McKibben actuator exhibits pronounced nonlinearities and hysteresis, primarily caused by the frictional interaction between the woven fibers and the expanding bladder. During pressurization, the fibers experience inter-thread compression, generating distributed dry friction that resists relative sliding within the braid []. This frictional behavior produces a hysteretic force response, in which extension yields higher forces than contraction at the same pressure. Experimental studies have reported effective friction coefficients of approximately 0.01–0.02 for typical synthetic braids, corresponding to hysteresis levels of about 10–15% of the peak output force []. The dynamic frictional behavior can be described by a combined Coulomb–viscous model []:

where and denote the static (Coulomb) and viscous friction coefficients, respectively. Experimental analyses indicate that the frictional term contributes up to 20% of the total contraction force, consistent with observed hysteresis loops in quasi-static and dynamic tests [,].

Further modeling refinements introduced correction factors to account for end-cap geometry, radial elasticity, and localized shape distortion near the termination regions, improving predictive accuracy by 30–50% compared with earlier formulations []. Collectively, these studies demonstrated that the nonlinear force–displacement behavior of pneumatic artificial muscles originates from three coupled mechanisms: geometric nonlinearity associated with braid-angle variation, frictional losses within the sleeve–bladder interface, and elastic energy storage in the rubber liner.

While these features contribute to the characteristic compliant behavior of McKibben-type actuators, they also introduce several drawbacks. The dry friction between the braided sleeve and the bladder produces hysteresis and energy losses, whereas the nonlinear force–length relationship complicates precise control without advanced feedback schemes [,,]. Additionally, a threshold pressure is required to initiate contraction, reducing responsiveness at low pressures, and the achievable force-to-weight ratio remains limited compared to more recent muscle architectures.

Netted muscles are similar to braided muscle types in terms of their structure. The main difference is the density of the external mesh outside the membrane: netted muscles feature a mesh with comparatively large openings, a concept originating from early fluid actuator designs [,]. Membranes are usually either stretching or rearranging types, where the stretching membrane accommodates the looser mesh at low pressures and the rearranging membrane (typically non-stretchable) regroups its structure upon inflation at higher pressures []. Similar to the braided muscle type, the disadvantages of the netted muscle include high hysteresis, localized stress concentrations, and limited stroke.

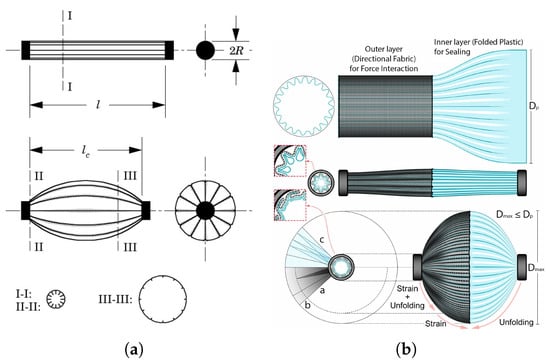

In contrast, pleated muscle, known as Pleated Pneumatic Artificial Muscle (PPAM), uses a pleated membrane that inflates without material stretching or friction, addressing key drawbacks of braided designs [,]. This PPAM operates through smooth membrane unfolding, minimizing energy loss and leading to more efficient, consistent performance. It also offers a greater contraction range, achieving up to 45% stroke compared to the typical 20–30% in braided muscles. Its lightweight structure and high strength-to-weight ratio make it well-suited for wearable and mobile applications.

Recent work has introduced pleated fabric-based PAMs (pfPAMs) tailored for soft wearable robots, achieving up to 40% contraction, a high force-to-weight ratio, and low-pressure operation, significantly improving their suitability for exosuits and rehabilitation devices []. Figure 3 illustrates both the original pleated designs reported in earlier studies [,] and the latest pfPAM concept from 2024 [], highlighting the progression of pleated actuator technology.

Figure 3.

(a) Pleated PAM: uninflated (top) and inflated (bottom) []. Pressurization unfolds the membrane, shortening the actuator (from l to ) and generating radial expansion (III-III), as shown in the cross-sectional views. (b) The final pfPAM design and the layer-by-layer transformation of the shells’ shape and dimensions from two perspectives [].

In embedded muscle actuators, the load-bearing structure is integrated within the membrane itself. An early design consists of a rubber tube reinforced with fibers aligned axially or in a double helix [,,]. This design results in low hysteresis and a very low threshold pressure compared to traditional braided muscle actuators. However, radial expansion is significant, limiting operational pressures to 10–100 kPa. Modern Festo PAMs (e.g., DMSP series []) are conceptually similar to embedded designs, using an integrated elastomeric membrane with embedded aramid fibers and optimized connectors. These actuators can achieve forces up to 6000 N, operate at pressures up to 0.6–0.8 MPa, and allow contractions of up to 25% depending on size []. Recent modeling efforts also confirm that such embedded-fiber constructions provide superior force consistency and reduced error in static force prediction compared to traditional McKibben actuators [].

Paynter [] introduced the Hyperboloid Muscle, featuring an elastomeric membrane shaped as a hyperboloid of revolution and reinforced with straight, inextensible fibers connecting the end fittings. When pressurized, the actuator transitions from a slender hyperboloidal form to a near-spherical shape, generating axial contraction with low hysteresis and moderate radial expansion. The prototype achieved a contraction of approximately 25% and an output force of 500 N at 200 kPa for a 25 mm long, 12.5 mm diameter sample [].

Building on this concept, a hyperboloidal pneumatic artificial muscle (h-PAM) was recently developed, featuring a silicone hyperboloidal tube reinforced with straight Ni-Ti alloy fibers []. The prototype achieved up to 15% contraction at 50 kPa, about 2.5 times greater than a McKibben muscle of the same dimensions, while maintaining structural flexibility and compactness. A summary of key performance characteristics for various traditional PAM designs is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Performance comparison of traditional PAM designs.

While compressed air remains the conventional working medium for PAM actuation, some researchers have explored the use of incompressible fluids to achieve higher forces and improve actuator performance. These approaches are discussed next.

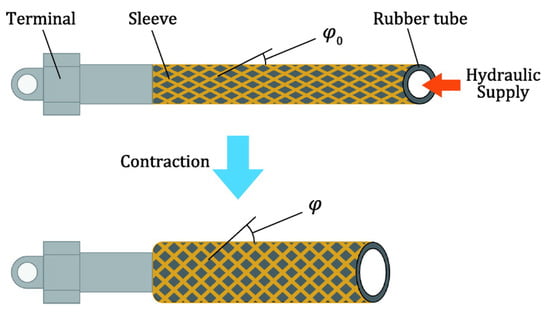

2.1.2. Hydraulic Artificial Muscles (HAMs)

In hydraulic artificial muscles (HAMs), incompressible fluids such as oil or water replace compressed air as the working medium, which enables significantly higher force output and energy density. By leveraging hydraulic pressures exceeding 4 MPa, they can achieve force outputs up to 28 kN in large-scale designs (4 cm diameter, 70 cm length) []. The core structure resembles traditional McKibben muscles, comprising an elastomeric tube surrounded by a high-strength braided sleeve; however, critical design enhancements are required to withstand hydraulic pressures. These include ultra-high-strength sleeve materials, such as p-phenylene-2,6-benzobisoxazole (PBO) fibers [,], which offer 5.8 GPa tensile strength and superior resistance to heat and friction compared to conventional polyester or aramid fibers. A contraction force of 8.8 kN at 5 MPa and force density per mass (FDM) of 17.5 kN/kg was achieved by the HAM fabricated using oil-resistant nitrile rubber and aramid fiber sleeves [], shown below in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Structure and actuation mechanism of the HAM [] (Copyright © 2018 Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group and The Robotics Society of Japan, reprinted by permission of Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group).

Unlike pneumatic muscles, hydraulic systems avoid energy losses from fluid compressibility, resulting in higher stiffness, improved position accuracy, and greater stability during dynamic loading [,,]. This enables HAMs to achieve force densities of and energy densities of , surpassing conventional hydraulic cylinders and pneumatic muscles by factors of 1.7–33. Key heavy-duty applications include rescue robots, forestry machinery, and shape-adaptable power hands capable of grasping 230 kg objects [].

Despite their advantages, HAMs face challenges such as fluid leakage risks, complex hydraulic infrastructure (e.g., pumps, valves), slower dynamic response (∼1 Hz bandwidth) and precise sleeve fabrication requirements. For instance, braided sleeves must maintain optimal spiral angles (e.g., 25°–30°) to optimize the balance between contraction ratio and radial expansion []. Additionally, end-fixing mechanisms, such as C-clamps and reinforced plugs, are critical to prevent sleeve slippage under high pressures. A comparative summary of pneumatic and hydraulic artificial muscles is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Performance comparison between pneumatic and hydraulic artificial muscles.

2.2. Non-Traditional Actuation Mechanisms

In recent years, researchers have proposed a wide range of non-traditional actuation mechanisms for pneumatic artificial muscles (PAMs), expanding their functional capabilities and addressing key limitations of conventional designs. These approaches retain the core principle of fluid-induced deformation but introduce novel design concepts, materials, and operating modes to overcome issues such as radial expansion, limited operational precision, hysteresis, and dependence on bulky pneumatic systems. Notable examples include vacuum-powered PAMs (VPAMs), inverse PAMs, foldable and origami-based PAMs, non-inflatable PAMs, and hybrid structures. This section reviews recent advancements in these alternative actuation strategies.

2.2.1. Vacuum-Powered PAMs

Vacuum-powered PAMs (VPAMs) invert the typical operating principle of traditional PAMs by employing negative pressure to induce actuation. When internal pressure is reduced below the ambient, the flexible structure collapses inward, generating longitudinal contraction []. This mode of operation offers several intrinsic advantages, including fail-safe behavior (muscle relaxes on vacuum loss), reduced risk of membrane rupture, lower energy consumption, and improved safety for human-robot interaction.

Recent studies have demonstrated a wide range of VPAM architectures. For example, Kresling origami-based VPAMs [] achieve up to 62% contraction using a lightweight 3D-printed thermoplastic elastomer structure. Negative pressure folds the origami creases, generating rapid contraction (0.18 s) and allowing the actuator to lift loads up to three times its own weight with high energy efficiency. This makes the design especially attractive for portable and battery-powered systems.

A low-profile VPAM (LP-VPAM), specifically designed for infant rehabilitation [], is shown below in Figure 5. It achieves a 61% contraction ratio and generates 26 N of force at low vacuum pressures (up to −40 kPa), enabling safe and comfortable actuation for pediatric applications. The actuator’s compact (10 mm height), lightweight construction makes it well-suited for wearable therapeutic systems.

Figure 5.

Low-profile VPAM (LP-VPAM) actuating an infant leg model under −40 kPa. Unactuated state (a), actuated state (b) [].

A modular origami-inspired VPAM [] achieved greater than 80% relative deformation at −80 kPa. The design combines 2D membrane-shell structures with origami-inspired folding to yield exceptional load-to-weight performance, lifting 4 kg (455 times its own weight) while maintaining rapid dynamic response (∼1 s) and achieving energy conversion efficiency up to 20.5%. Its fold-based mechanism also minimizes friction losses and enables scalable, low-cost fabrication, supporting applications in wearable robotics and healthcare. This performance significantly exceeds that of conventional silicone-based actuators.

Building upon these concepts, a novel Hyperbaric Vacuum-Based Artificial Muscle (Hyper-VAM) was recently introduced []. This design combines the advantages of vacuum-driven actuation with a positively pressurized outer chamber, enabling simultaneous use of negative and positive pressures. By exploiting a total pressure differential of 150 kPa, the Hyper-VAM achieves an exceptional 89.1% contraction ratio and can lift loads up to 80 kg (corresponding to ∼784 N output force), while maintaining compliance and rapid response (full contraction in 0.31 s). The actuator exhibits a peak output power of 101 W and a specific power of 675 W/kg, significantly surpassing conventional VPAMs and comparable pneumatic systems.

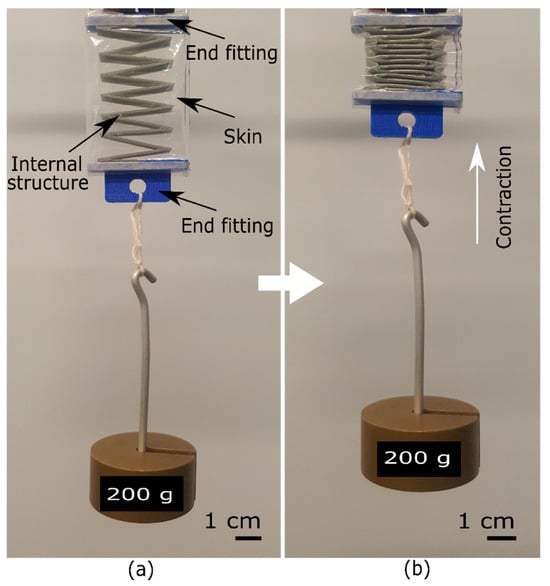

Finally, the ultralight hybrid pneumatic artificial muscle (UH-PAM) [] merges a vacuum-driven bellow-shaped elastomeric skin with foam segments and rigid rings, which achieves a 50% contraction ratio and can lift 3 kg with a rapid contraction phase (0.5 s). The hybrid design offers enhanced axial stiffness while preserving compliance and outperforms conventional McKibben muscles in both energy density (66.3 W/kg) and strength density (1.64 kN/kg). A summary comparison of vacuum-powered PAM characteristics is provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

Performance comparison of vacuum-powered pneumatic artificial muscle (VPAM) designs.

Across these recent designs, VPAMs demonstrate promising performance, with contraction ratios of 50–80%, low hysteresis, and exceptional load-to-weight ratios. Their inherent safety, structural compactness, and potential for portable integration make them highly attractive for emerging applications. However, challenges remain in optimizing dynamic response (particularly the release phase), improving membrane durability, and achieving precise control under varying loads.

2.2.2. Inverse PAMs

Inverse pneumatic artificial muscles (IPAMs) and eversive pneumatic artificial muscles (EPAMs) represent a class of actuators that operate on the principle of elongation under positive pressure, in contrast to the contraction observed in traditional McKibben muscles. These mechanisms leverage controlled radial expansion and eversion to convert internal pressure into axial extension.

Inverse pneumatic artificial muscles (IPAMs) elongate under positive pressure by constraining radial expansion with embedded fiber structures. An earlier related configuration, known as the reverse pneumatic artificial muscle (rPAM), exhibited similar extensile behavior under pressurization by relieving the pre-strain in helically reinforced silicone tubes []. The rPAM achieved approximately 50% axial elongation at pressures up to 190 kPa and generated antagonistic motion in a single-degree-of-freedom joint, demonstrating reliable position control through sliding-mode and feed-forward algorithms.

Early work introduced the Soft Inverse Pneumatic Artificial Muscle (SIPAM) capable of large elongations up to 200% and passive contraction of about 67% under 180 kPa []. Later designs incorporated piezoresistive conductors for self-sensing, achieving 40% active strain and 13.6 N pulling force at comparable pressures []. These developments enable bidirectional actuation and adaptability for exosuits and robotic manipulators, though challenges remain with hysteresis and material creep. Their nonlinear pressure–strain response requires advanced control, but IPAMs provide enhanced compliance and geometric flexibility compared to McKibben muscles.

Eversive pneumatic artificial muscles (EPAMs) employ an eversion mechanism, where a fabric bladder unfolds outward under pressure to generate extension []. This architecture allows elongation up to 100% at safe, low pressures (∼83 kPa), with efficient force transmission and high compliance. EPAMs thus enable lightweight, human-safe actuation for wearable and medical applications, outperforming conventional PAMs in achievable strain.

A key distinction between eversive PAMs (EPAMs) and pleated PAMs (PPAMs) lies in their actuation roles. While PPAMs achieve efficient contraction through pleat unfolding, EPAMs specialize in extensile motion via fabric eversion. This minimizes nonlinear counteracting forces and enables greater angular displacement and load handling under similar pressures []. A summary of inverse and eversive PAM characteristics is provided in Table 4.

Table 4.

Performance comparison of inverse and eversive pneumatic artificial muscle designs.

The EPAM architecture introduces an extensile actuation concept for soft robotics. Owing to its lightweight, compliant, and scalable design, it has potential for applications such as rehabilitation and wearable assistive devices [].

2.2.3. Foldable and Fabric-Based PAMs

Foldable and fabric-based pneumatic artificial muscles represent a subclass of actuators designed to minimize internal friction, simplify construction, and enable highly deployable soft robotic systems. Unlike conventional McKibben muscles, these designs avoid multilayer bladders or braided sheaths by leveraging anisotropic fabric properties or programmed folding geometries.

The Foldable Fabric PAM (fPAM) [] eliminates both bladders and sheaths through the use of a single layer of silicone–urethane-coated ripstop nylon, bias-cut at 45° and sealed with flexible adhesive. Upon pressurization, the bias-cut fabric expands radially and contracts longitudinally, mimicking McKibben-like contraction but with substantially reduced hysteresis and friction. Reported performance metrics include ultra-low hysteresis (<1%), rapid contraction (∼0.03 s), durability exceeding 100,000 cycles, and a high force-to-weight ratio. Demonstrated applications include continuum “vine” robots and foldable robotic arms, where fPAMs provide speed and compactness beyond traditional PAMs.

A related concept, the Folded Pneumatic Artificial Muscle (foldPAM) [], employs thin-film air pouches with programmable folding geometries. Unlike fPAMs, where actuation arises from material anisotropy, foldPAMs achieve tunable contraction through lateral folding patterns that control end constraints. By varying the fold ratio (folded width normalized to initial width), foldPAMs can shift between high-force/low-strain and low-force/high-strain behaviors. Experiments demonstrated a design space spanning 2–37% strain and force reductions of up to 80% with increasing fold ratio.

Both fPAMs and foldPAMs advance soft actuation by reducing reliance on frictional interfaces and enabling compact, efficient contraction. While fPAMs excel in speed, simplicity, and deployability, foldPAMs provide enhanced adaptability and geometric programmability.

2.2.4. X-PAMs

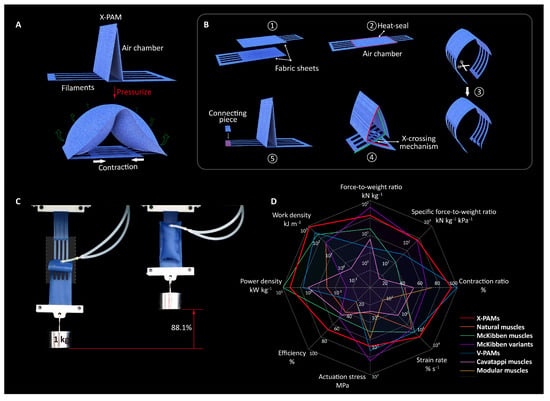

Despite progress in foldable and fabric-based PAMs, achieving extreme contraction ratios and multi-axis motion within lightweight, compact designs remains challenging. X-crossing pneumatic artificial muscles (X-PAMs) address this limitation by introducing an innovative architecture that enables high-speed, large-range contraction and versatile deformation without radial expansion []. It is constructed from two TPU-coated fabric sheets with interlocking filaments. Upon pressurization, the air chamber expands linearly, forcing the filaments to slide past one another in an X-crossing pattern, mechanically analogous to the sliding of actin and myosin filaments in muscle fibers (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

X-crossing pneumatic artificial muscles: (A) actuation principle; (B) filament-based structure; (C) lifting 1 kg with 88.1% contraction; (D) comparative performance with plotted values corresponding to indicators reported in Table S1 of the original publication [].

This mechanism achieves contraction ratios up to 92.9%, far exceeding the typical of McKibben muscles. Additional performance metrics include a high force-to-weight ratio, rapid response (peak strain rate 1603%/s), and specific power of 5.7 kW/kg []. The design is tunable through the width-to-length (W/L) ratio: higher W/L values favor greater force output (e.g., 134.7 N at 150 kPa for 2:1), whereas lower ratios maximize contraction (up to 92.9% at reduced forces for 1:2).

They also demonstrate versatility across robotic systems. In joint actuation, an X-PAM-powered robotic elbow achieved flexion angles over 125° at 100 kPa, outperforming McKibben actuators (typically <60°). In dynamic locomotion, a 337 g robot with a single X-PAM achieved a vertical jump of 34.1 cm (6.9 times its height). Lightweight grippers as small as 1.9 g successfully lifted loads of 56.9 g (45 times their own weight) while handling fragile items such as eggs and electronic components.

Durability and robustness further distinguish X-PAMs. They operate reliably between −20 °C and 100 °C, withstand 5000 cycles at 100 kPa, and even survived rollover by a 1500 kg vehicle without structural failure []. These properties make them attractive for outdoor robotics, wearable devices, and industrial automation in variable environments.

A summary comparison of foldable and fabric-based PAM designs, including the X-PAM, is provided in Table 5.

Table 5.

Performance comparison of foldable and fabric-based PAM designs, including X-PAMs.

Taken together, fPAMs, foldPAMs, and X-PAMs illustrate complementary approaches toward compact, deployable, and high-performance soft actuation systems.

2.2.5. Grouped and Bundled PAMs

Arranging multiple pneumatic artificial muscles in parallel or series provides an effective strategy for enhancing actuator performance, adaptability, and safety. Bundled configurations emulate the organization of biological muscle groups, improving force output, redundancy, and motion versatility. Parallel arrangements increase compliance and scalable force capacity, while serial configurations support advanced functionalities such as self-sensing and multi-axis actuation.

A recent study presented a bundled PAM system designed for elbow exoskeletons targeting post-stroke rehabilitation []. It employs multiple parallel PAMs arranged side by side, mimicking skeletal muscle fiber bundles. Each PAM contributes to overall contraction, while the distributed structure enhances compliance, redundancy, and anatomical adaptability. Compared to a single large-diameter PAM, smaller bundled PAMs conform more effectively to human joint geometries and respond faster. Redundancy further improves safety and reliability, as underperforming or failed actuators do not compromise system function.

The Multi-connection Pneumatic Artificial Muscle (MPAM) extends this approach by integrating six McKibben muscles via modular Y-shaped valves []. The MPAM achieved a contraction ratio of 28%, while remaining lightweight (35 g) and compact. By selectively activating 2, 4, or 6 fibers, the actuator allows flexible trade-offs between force and speed: fewer fibers improve responsiveness, while full activation maximizes force. The design also demonstrated reduced hysteresis and improved energy efficiency, though nonlinear force-displacement effects and limited high-strain load capacity remain challenges.

Recent developments have extended bundled PAM concepts to multi-DOF joints with integrated sensing []. A 2-DOF parallel joint driven by six antagonistic McKibben muscles around a universal hinge used a spring-tendon sensing mechanism for real-time orientation feedback. It achieved precise closed-loop control over ±45° pitch and yaw motion, offering compliant and accurate performance suitable for wearable and assistive robots.

Bundled PAMs also enable continuum soft manipulators. Liu et al. [] introduced a manipulator with two muscle groups: external McKibben PAMs (2.0 mm diameter) for positional control, and internal PAMs (1.3 mm) for stiffness modulation. Radial placement of three external muscle groups enabled bending up to 80°, while six internal PAMs modulated stiffness independently (0–147 N/m). Experiments showed stiffness could be increased by 50% at fixed positions, enabling decoupled stiffness and position control, a longstanding challenge in soft robotics.

Alternative grouped designs further extend functionality. The Bidirectional Curl PAM (BCPAM) [] employs a dual-chamber configuration with anisotropic fabric sheaths. Antagonistic pressurization of the semi-elliptic chambers achieves bidirectional curling up to 82.7° and torque generation of 34.1 Nm at 400 kPa. This compact design provides efficient torque-to-weight performance and scalable multi-DOF actuation, ideal for wearable exoskeletons and bionic robotic systems.

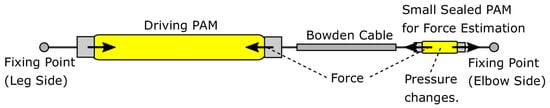

Serial configurations can also provide advanced sensing capabilities. One study proposed connecting a primary driving PAM with a smaller, sealed PAM in series, where the secondary PAM acted as a force sensor equipped with an internal pressure transducer, as shown in Figure 7 []. In this setup, variations in the sealed chamber pressure correlated with axial tension, enabling self-sensing without external load cells. Coupled with hybrid feedforward-feedback control, the configuration improved force-tracking accuracy (NRMSE < 5%) and reduced phase delay. Such approaches hold promise for adaptive rehabilitation devices and wearable teaching suits.

Figure 7.

Force estimation using the inner pressure of the serial-connected small PAM [].

A refined model for serially connected pneumatic muscles was later [], where the framework extended pleated-PAM mechanics to serial thin-film segments, accurately capturing nonlinear force-strain behavior and enabling predictive design of continuum actuators. This model-based approach provides guidelines for tailoring stiffness and curvature distribution in multi-segment soft manipulators.

Grouped and bundled PAMs thus expand the design of soft actuation by enabling scalable force, redundancy, adaptive stiffness, and integrated sensing. A summary comparison of these configurations and their key parameters is presented in Table 6 below.

Table 6.

Performance comparison of grouped and bundled pneumatic artificial muscle (PAM) architectures.

Future research is expected to refine modular control strategies, improve energy efficiency, and develop hybrid architectures that combine parallel and serial arrangements.

2.2.6. Reconfigurable PAMs

Recently, a major trend in soft robotics has been the development of reconfigurable pneumatic artificial muscles capable of adapting their morphology, stiffness, and functionality on demand. Reconfigurable designs allow a single actuator to support multiple motion modes, task-specific customization, and modular assembly, thereby enhancing versatility, reducing hardware redundancy, and improving adaptability to dynamic environments. Modularity addresses long-standing limitations of fixed-function actuators by enabling flexible reconfiguration and reuse.

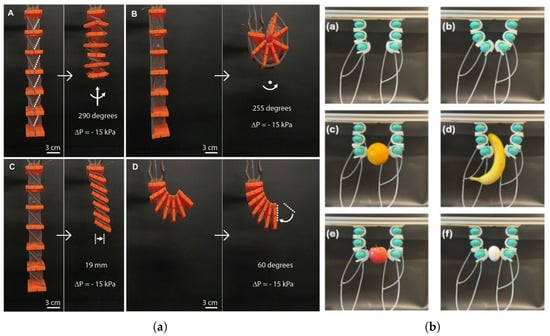

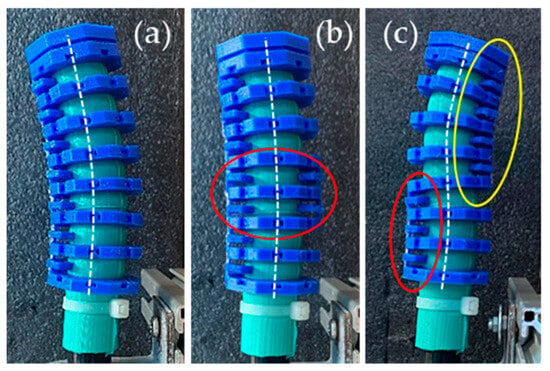

A representative example is a vacuum-powered PAM design with manually reconfigurable external reinforcements []. In this system, stacked elastomeric air chambers are constrained by rigid rings and a flexible membrane. By replacing external reinforcement elements, the actuator can generate bending, twisting, shearing, or rotary motions. In a six-chamber configuration, see Figure 8a, the actuator achieved 290° twisting and 255 ° bending, demonstrating its potential for bioinspired motion tasks such as crawling robots.

Figure 8.

(a) Complex motions achieved by a six-chamber modular VPAM actuator (bending, twisting, and rotary actions) []. (b) Reconfiguration of six-cell actuators into two three-cell units, shown unpressurized/pressurized and grasping delicate objects (orange, banana, apple, egg) [].

A similar design was used for a modular rotary soft actuator, in which each unit comprises an inflatable inner balloon reinforced by a flexible arched structure, see Figure 8b []. Pressurization induces rotary motion, and modules can be linked in series or parallel to form bending, extension, or rotary assemblies. Users can increase or reduce actuator length by adding or removing modules, effectively tuning the number of degrees of freedom and motion range.

For wearable robotics, Liu et al. [] introduced a Reconfigurable Self-Sensing PAM (RSPAM) consisting of modular multi-chamber segments mounted on a fabric sheath. Each segment contracts via a braided fabric winding, similar to a McKibben muscle, while maintaining user comfort. The design achieves high contraction ratios (∼71% at 0.3 MPa) and allows sheath length and active segments to be reconfigured for different joint geometries. Integrated liquid-metal strain sensors provide closed-loop feedback, and a positive pressure jamming mechanism locks the actuator when required. In elbow-assist tests, the RSPAM reduced muscle fatigue by over 53%, demonstrating its promise for wearable exosuits.

Reconfigurability has also been demonstrated through external reinforcement structures. One study proposed a silicone rubber tube combined with configurable reinforcement segments that can be rearranged to alter bending direction and stiffness []. Symmetric reinforcement increases rigidity, while asymmetric configurations enable bending (Figure 9). Demonstrations included a soft robotic finger capable of grasping diverse objects (up to 210 g), with fast activation (53.9 ms) and deactivation (29.6 ms). This approach emphasizes cost-effectiveness and rapid reconfiguration, though reinforcement alignment variability and wear remain challenges.

Figure 9.

Reconfigurability demonstration of a modular soft actuator at 0.12 MPa []: (a) all double virtual hinges aligned; (b) four opposed double virtual hinges inhibiting two sectors (red oval); (c) three double virtual hinges along one side (red oval) and the remaining four along the opposite side (yellow circle), enabling different bending responses.

Recent advances have also explored reconfigurable soft pneumatic actuators (SPAs) fabricated from multi-material self-healing polymers []. These actuators combine stretchable and rigid self-healing layers for programmable bending, twisting, and elongation. Self-healing capability supports autonomous recovery after damage, while the reconfigurable design permits post-fabrication adjustment of motion modes. Table 7 summarizes the comparison of key design features of reconfigurable PAMs.

Table 7.

Performance comparison of reconfigurable pneumatic artificial muscle (PAM) designs.

Collectively, reconfigurable PAMs represent a shift toward modular, Lego-like actuation systems: actuators that can be assembled, tuned, and adapted for diverse tasks. These designs enhance versatility, reduce redundancy, and support adaptive robotic platforms.

2.2.7. Origami-Based PAMs

Origami-inspired structures provide a promising pathway for enhancing the performance and versatility of pneumatic artificial muscles by embedding folding patterns into flexible materials. They achieve large, programmable deformations with low material strain and high structural efficiency. Among these, vacuum-driven origami PAMs are particularly noteworthy, as they combine the geometric efficiency of folding with the intrinsic benefits of vacuum actuation, offering energy efficiency and fail-safe operation. While origami-based PAMs could in principle be grouped under vacuum-driven PAMs, they are discussed separately here to highlight their distinctive reliance on folding geometry as the primary design principle.

An early example is the Origami Vacuum PAM (OV-PAM), which demonstrated the potential of combining origami folding geometry with vacuum actuation []. The triangular origami design, with rigid end plates and flexible PVC sidewalls, achieved up to ∼80% linear contraction while maintaining a constant cross-sectional area. The actuator sustained payloads of up to 10 kg and reached system efficiencies of 11–15% using compact diaphragm pumps. Importantly, the OV-PAM was powered successfully with renewable sources, including a 20 W solar panel and a 3.7 V battery, underscoring its suitability for off-grid or field robotics applications.

Building directly on this concept, Reconfigurable Origami Vacuum PAM (ROV-PAM) was introduced later []. The ROV-PAM incorporated six types of actuating modules (contractile, bending, and twisting) and three fluidic supporting modules, all connected via magnet-based couplers. This architecture enabled rapid reconfiguration to alter both functionality and performance. Experimental validation confirmed that ROV-PAM modules could generate contractile strains of up to ∼60–70%, bending angles exceeding 25° under load, and cooperative contraction ratios of ∼75% when multiple modules operated in parallel. By integrating modularity with origami mechanics, the ROV-PAM exemplifies how folding-based architectures can deliver multifunctional and reconfigurable soft actuation within a unified design framework.

Building on these hybrid rigid-flexible platforms, Caiyang et al. [] advanced the concept further by presenting a monolithic 3D-printed soft foldable actuator (SFA) with a Kresling crease pattern fabricated entirely from thermoplastic elastomer. The SFA combined high contraction ratios (62–64%), large blocked forces (∼18 N), and ultralight weight. Tandem SFAs actuated an anthropomorphic leg that simulated a running motion at 1.8 m/s and kicked a football, while additional suction-cup integrations produced versatile grippers.

Collectively, origami-based PAMs offer advantages in compactness, programmability, and integration of sensing (see Table 8). Their ability to leverage folding geometry enables high-performance actuation at low pressures, while modular variants expand adaptability for wearable and robotic systems. Current challenges include modeling nonlinear folding dynamics, improving fabrication repeatability, and extending cyclic durability.

Table 8.

Performance comparison of representative origami-based pneumatic artificial muscle (PAM) designs.

2.2.8. Hybrid PAMs

Hybrid pneumatic artificial muscles combine pneumatic actuation with other energy domains or control strategies to overcome inherent limitations such as slow dynamics, tethering, and limited precision. By integrating thermal, electrical, chemical, or magnetic elements, hybrid PAMs preserve lightweight compliance and safety while enabling untethered operation, improved control bandwidth, and adaptive behaviors.

Thermo-Pneumatic Actuation

Thermo-pneumatic PAMs use thermal energy to expand the enclosed gas and drive actuation without an external air supply. A sealed gas volume is electrically heated, raising internal pressure and deforming the actuator. Shin et al. [] introduced a dual-mode Thermo-PAM capable of both contraction and extension depending on heating configuration. The actuator lifted up to 20 kg in positive mode and 15 kg in negative mode, with actuation speeds up to 5.38 mm/s and relaxation speeds around 1.22 mm/s (typical 8–15 s cycles) at 300 W input power. The negative mode maintained grasps for over 5 h, demonstrating energy-efficient holding. Trade-offs include slow heating/cooling cycles and thermal management, though ongoing improvements in heater design aim to enhance response speed [].

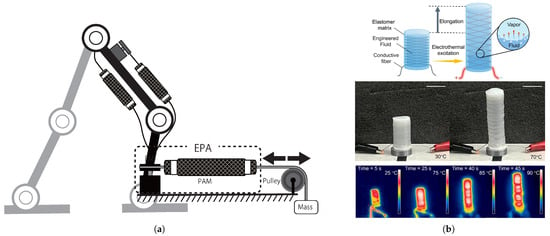

Pneumatic-Electric Hybrids

Pneumatic-electric systems pair PAMs with motors or electromagnetic brakes to combine compliance with precise control. Sharbafi et al. [] proposed the Electric-Pneumatic Actuator (EPA), which uses a PAM alongside a DC motor, as shown below in Figure 10a. Tests on a bipedal robot knee showed improved efficiency and peak power without significant added weight. This PAM serves as a compliance element, while the motor provides accuracy, supported by a validated dynamic model (). Other designs explored macro-mini architectures, combining a PAM with either a DC motor or a magnetic particle brake []. The motor enhanced fine control, while the brake improved safety, reducing impact peak forces by 35%. An electro-pneumatic hybrid actuator [] further integrated a TPU air chamber with electrostatic actuation, achieving 93.5° bending in 60 ms at 6–10 kV, sustaining 20 Hz cyclic motion with silent operation.

Figure 10.

(a) A sample design of an Electric-Pneumatic Actuator (EPA) for bipedal locomotion control and its evaluation setup []. (b) Concept of the electro-conductive fiber-reinforced phase transition actuator (E-FPTA): mechanism, elongation at 70 °C, and infrared imaging [].

Chemically Driven Hybrids

Chemical actuation eliminates pumps by generating pressurized gas through reactions or phase changes. An electrothermal-pneumatic actuator, named electroconductive fiber-reinforced phase transition actuators (E-FPTAs), used embedded stainless-steel heating fibers and Novec fluid to achieve 120% elongation, 16 N output, and multi-mode motion within 50 s []. The concept of E-FPTAs is depicted below in Figure 10b. The demonstrations included a robotic glove with 8 DOFs.

Another design is a hybrid electrolysis-reaction actuator, named Hybrid of Mixed Electrolysis and Fluids Chemical Reaction (HEFR), which combines sodium bicarbonate-acetic acid reactions with electrolysis to generate rapid expansion (25 mm in 1 s, lifting 250 g) []. Such systems are low-cost, scalable, and silent, though challenges remain in controllability, reusability, and safety.

A pioneering example of chemically driven pneumatic actuation is the Reciprocating Chemical Muscle (RCM), developed for Georgia Tech’s insect-scale Entomopter micro air vehicle [,]. The RCM converts chemical energy directly into pneumatic motion via non-combustive catalytic decomposition of monopropellants such as hydrogen peroxide, producing synchronized reciprocation for flapping-wing propulsion. The same process yields usable thermal and electrical energy through integrated thermoelectric elements, enabling a self-contained, multi-modal actuation platform.

Magnetically Induced Phase-Change Hybrids

Magnetically induced hybrid PAMs use alternating magnetic fields to heat magnetite-water mixtures, producing steam to drive actuation. The Magnetically Induced Thermal PAM (MITPAM) achieved 20% strain in 10 s under 2 kg load, with work density (40 kJ/m3) comparable to muscle tissue []. The design operated fully untethered, powered by Li-ion batteries and a portable induction heater, with robust performance over 50 cycles. However, there are certain limitations, such as low energy efficiency and cooling delays.

Hybrid PAMs illustrate the potential of integrating thermal, electrical, chemical, and magnetic domains to overcome PAM limitations. The summary of the hybrid PAM designs is presented below in Table 9.

Table 9.

Performance comparison of hybrid pneumatic artificial muscle (PAM) designs.

2.2.9. Compact, Flat, and Non-Inflatable PAMs

Traditional McKibben muscles exhibit substantial radial expansion and high volumetric demand, limiting their integration in wearable or space-constrained robotic systems. To address this issue, recent research has focused on compact and flat pneumatic artificial muscles that restrict lateral deformation while preserving the compliance, efficiency, and force density characteristic of fluidic actuation. These designs also reduce air consumption and allow modular stacking, making them particularly suitable for exosuits and lightweight manipulators.

The sensorized flat PAM (sFPAM) integrates embedded microfluidic channels filled with eutectic gallium-indium (eGaIn) for self-sensing of force and displacement. Its zero-volume air chamber establishes a direct coupling between pressure and deformation, achieving a contraction of approximately 19.8% and a blocked force of 24 N at 89.7 kPa. This configuration enables intrinsic proprioceptive feedback without external sensors, although mechanical hysteresis was not quantified.

The flat inflatable artificial muscle (FIAM) employs internal constraint layers and outer plates that translate lateral expansion into axial contraction. The actuator achieves up to 55.3% strain at only 30 kPa, producing 25 N of force with moderate hysteresis of around 10–15% arising from interlayer friction. When arranged in arrays within a fully soft lift-assist suit, FIAMs operate in the 10–50 kPa range and generate up to 43 N per actuator, maintaining less than 1.5% performance degradation after 200 cycles, indicating high durability and minimal hysteresis.

The non-inflatable PAM (NI-PAM) eliminates the need for an expanding bladder by using a fiber-reinforced latex tube that contracts axially under negative pressure with negligible radial growth. Despite a modest contraction of about 4%, the actuator produces high output forces up to 90 N at −50 kPa, with an estimated hysteresis of 20–25% due to viscoelastic losses and fiber friction. Its compact geometry and low flow requirement make it suitable for integration in dense or embedded systems where large volumetric expansion is undesirable.

A summary comparison of compact and non-inflatable PAMs is provided in Table 10.

Table 10.

Performance comparison of compact and non-inflatable pneumatic artificial muscle (PAM) designs.

Collectively, these compact and flat PAMs demonstrate how geometric constraint, material layering, and integrated sensing can reconcile the trade-off between actuator thickness and mechanical performance. They offer an effective pathway toward thin, high-output, and self-sensing actuators for wearable and embedded soft robotic platforms.

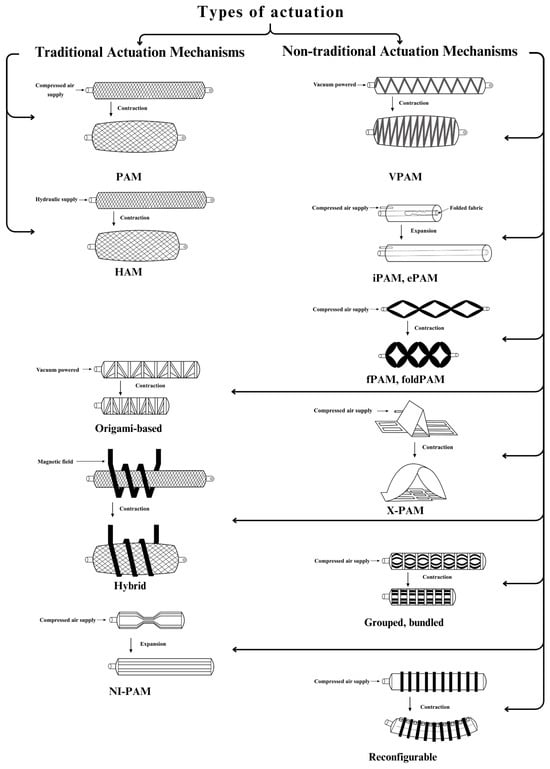

2.2.10. Overall PAM Classification and Comparison

It is important to note that the categorization of actuation mechanisms in this review (Section 2.1 and Section 2.2) follows recent developments in the literature and aims to highlight distinct design philosophies rather than impose rigid boundaries. Many actuators span multiple categories, for example, origami-based VPAMs or reconfigurable origami hybrids, yet they are presented separately to emphasize their primary design focus and contributions. This structured breakdown provides clarity in surveying the diverse and rapidly expanding landscape of PAM architectures while acknowledging the inherent overlap across approaches. Finally, a comprehensive summary of all PAM types is presented in a Table 11 alongside a Figure 11 with simplified schematics of their actuation principles, offering an accessible overview of the design space.

Table 11.

Performance summary of pneumatic artificial muscle (PAM) actuation types.

Figure 11.

Overview of actuation mechanisms in pneumatic artificial muscles (PAMs), categorized into traditional and non-traditional types.

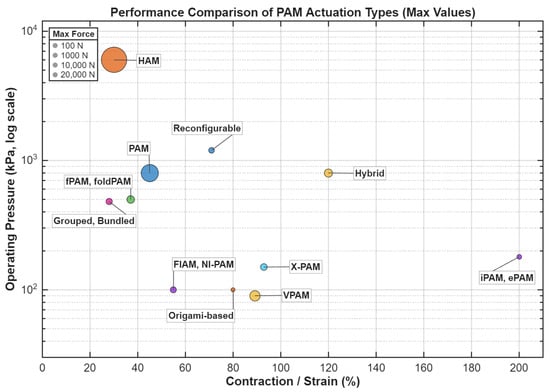

To complement this tabulated overview, Figure 12 visualizes representative performance trends using maximum reported values extracted from Table 11.

Figure 12.

Performance comparison of pneumatic artificial muscle actuation types in terms of contraction/strain and operating pressure (log scale). The plotted data correspond to representative values summarized in Table 12.

In addition to the general classification summarized in Table 11, a more detailed quantitative comparison of all actuator subtypes is provided in Table 12. This extended table consolidates strain ranges, operating pressures, force outputs, force densities, specific power, and actuation speeds, enabling a direct comparison of both traditional and emerging PAM architectures.

Table 12.

Performance summary of various PAM actuation mechanisms and subtypes.

3. Applications

Traditionally, pneumatic artificial muscles have been predominantly used in applications that prioritize their biomimetic properties, such as the development of exoskeletons and soft robotic systems. However, they are inherently lightweight structures with remarkable force-to-weight ratios that extend their applicability to a broader range of innovative fields. For instance, these attributes have been effectively harnessed in emerging areas such as computational storage and adaptive structural systems.

3.1. Traditional Applications

Early applications of PAMs exploited their biomimetic behavior, compliance, and light weight, offering clear benefits over rigid actuators. They have been widely used in biomechanics, rehabilitation, robotic manipulation, exoskeletons, and industrial automation, where safe human-robot interaction and adaptive force control are critical. Traditional systems focused on muscle-like actuation for joint assistance, grasping, or repetitive industrial tasks. Recent advances extend these uses by embedding smart materials, sensing, and advanced feedback control methods, enabling higher precision and adaptive performance.

3.1.1. Biomechanics and Rehabilitation

Pneumatic artificial muscles are widely applied in biomechanics and rehabilitation, where their inherent compliance, lightweight construction, and muscle-like actuation provide advantages over rigid actuators. These features enable safe human-robot interaction and adaptive force control, which are critical for exoskeletons, assistive devices, and rehabilitation robots.

PAMs are frequently used to assist patients with movement disorders [,,,,]. A notable example is the redesign of the CAMOped passive knee rehabilitation device into an active Controlled Active Motion (CAM) system driven by pneumatic artificial muscles []. The original CAMOped used a mechanical brake to provide adjustable resistance during cyclic leg exercises, whereas the updated version incorporated two Festo DMSP-20-353 actuators (Festo Vertrieb GmbH & Co. KG, Esslingen am Neckar, Germany) []. Each muscle operated at a supply pressure of up to 0.6 MPa and could generate foot loads of approximately 100 N (corresponding to a torque range of 0.1–20 Nm about the knee joint). The active configuration enabled real-time switching between assistance and resistance modes and implemented angle-dependent resistance profiles that better replicated physiological torque curves []. Although these improvements enhanced controllability and mechanical versatility, the study did not report quantitative clinical outcome data, such as measured increases in knee-joint range of motion or reductions in treatment duration when compared to the original passive CAMOped. Consequently, the clinical benefits of the PAM-driven system remain to be validated through patient trials.

Further quantitative studies on upper- and lower-limb rehabilitation have reported actuator-level metrics. For instance, twelve PAM variants were compared for elbow rehabilitation, where styrene-based actuators achieved a maximum contraction of 28 mm and a peak force of 328 N, identifying the S12LB configuration as the most suitable for joint-training applications []. In an ankle-rehabilitation robot, hierarchical compliance control allowed continuous modulation of torque and motion to follow the therapist’s guidance []. Likewise, a PAM-parallel-link thumb-rehabilitation device achieved precise flexion/extension with 3-D printed soft joints and pneumatic feedback control [].

Recent efforts emphasize integrating smart-material sensing with PAM-based actuation []. A triboelectric soft pneumatic actuator (TENG-SPA), inspired by a lobster tail, delivered approximately 20 N at 0.1 MPa for hand rehabilitation while simultaneously monitoring spasticity levels []. The embedded triboelectric sensors, coupled with a convolutional neural network, enabled the device to classify patient states and adapt its assistance level in real time (Figure 13). Similarly, compact fabric-integrated artificial muscle (FIAM) suits demonstrated multi-joint control and real-time impedance modulation for wearable rehabilitation assistance [].

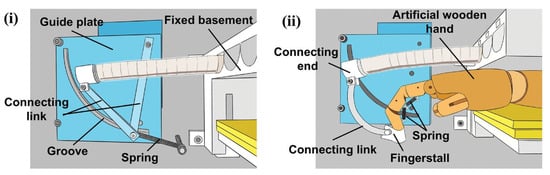

Figure 13.

Experimental platforms for evaluating the electrical output performance of the TENG-SPA []: (i) platform for assessing output under different load resistances; (ii) platform for evaluating electrical output during simulated finger-stretching exercises for spasticity.

Overall, PAM-based rehabilitation systems combine tunable biomechanics, adaptability, and patient safety, offering improved controllability and comfort compared with rigid actuators. However, these devices still face challenges related to hysteresis, air compressibility, and nonlinear force-length behavior, which hinder precise torque tracking and limit bandwidth during fast therapeutic motions [,,]. The need for compressors and tubing also increases system bulk and acoustic noise, while the limited number of clinical trials makes it difficult to quantify long-term therapeutic benefits relative to conventional rehabilitation devices []. Standardized patient studies are therefore needed to validate the clinical effectiveness of PAM-driven rehabilitation systems in improving the range of motion and accelerating recovery.

3.1.2. Human-Machine Interactions

Pneumatic artificial muscles (PAMs) play a central role in human-machine interaction (HMI) systems such as prosthetic limbs, wearable exoskeletons, and assistive devices, where their compliance, biomimetic actuation, and intrinsic safety are key advantages [,,]. Unlike rigid actuators, PAMs can closely mimic the mechanical response of biological muscle, enabling naturalistic movement, reducing impact loads, and improving user comfort. Recent research has focused on optimizing PAMs for wearable systems to increase force density and control precision.

In prosthetic applications, PAMs have been implemented primarily in experimental or prototype systems for transtibial and transfemoral configurations rather than in clinical products. One study developed a high-performance PAM capable of generating a peak force of 2.7 kN at 1.42 MPa with 32% contraction []. This output exceeds the biomechanical requirements of human gait, as in-vivo telemetry data show peak tibiofemoral forces of approximately 1.5–2.0 kN (about 2–3 times body weight for a 70 kg individual) during normal walking, and up to 2.8 times body weight during stair descent [,]. Hence, the actuator provides sufficient margin to replicate knee-joint torque demands (about 70–90 Nm at a 40–45 mm moment arm) through all gait phases, particularly stance and push-off. Innovations such as liquid-rubber coatings prevented bladder rupture under radial expansion, allowing the actuator to withstand forces up to 9 kN before failure. Compared to commercial PAMs from Festo [,] and Shadow Robot [,], the custom design offered greater contraction and force capacity, with nonlinear stiffness profiles that more closely resemble biological muscle behavior []. The Karlsruhe FLUIDHAND III project [] likewise demonstrated a PAM-driven prosthetic prototype before transitioning to electromechanical actuation for improved compactness.

In wearable exoskeletons, PAMs provide lightweight, compliant assistance with precise trajectory control. A PAM-driven elbow exoskeleton achieved over 100 N contraction force under a 7.5 kg load, supported by a parallel gas spring to improve stiffness and energy efficiency []. The system integrated a model-free adaptive controller, maintaining tracking errors below 0.038 rad. Another study compared styrene- and latex-based PAMs for elbow rehabilitation, showing that styrene bladders achieved higher contraction (27.6 mm) and force (328 N), while latex designs reduced hysteresis []. A compact hinge with a torsion spring reduced bulk, enabling 110° angular deflection with safe operation under 5 kg loads.

PAM-based prosthetic and wearable systems combine high force capacity with intrinsic compliance, enabling actuators to reproduce muscle-like motion and safe interaction with users. Their lightweight design and smooth, controllable deformation make them ideal for human-machine interfaces that demand comfort and adaptability. Nevertheless, practical deployment remains limited by pneumatic hardware size, air-supply dependence, and the long-term fatigue of elastomeric materials []. Hysteresis and pressure-rate sensitivity also complicate control, requiring advanced sensing and compensation strategies to achieve stable torque tracking and back-drivable behavior [,,]. These findings confirm that PAMs provide both the compliance and output needed for effective human-machine interaction, while ongoing advances in reconfigurable (Section 2.2.6) and flat or non-inflatable PAM architectures (Section 2.2.9) are expected to yield more compact, efficient, and user-adaptive systems for next-generation prosthetics and assistive technologies.

3.1.3. Soft Robotics

PAMs are central to soft robotics, where their compliance, high force-to-weight ratio, and muscle-like dynamics enable safe and adaptive interaction [,]. They are increasingly used in robotic hands, manipulators, wearable devices, and bioinspired systems.

Miniaturized PAMs have been used for robotic palms, with prototypes as small as 4.1 mm in diameter and 39 mm in length producing forces across 207–552 kPa, confirming their potential for compact, efficient actuation []. Hybrid rigid-soft architectures also leverage PAMs: a recent 7-DOF bioinspired arm integrated PAM-driven joints with servomotor wrists, achieving stable, compliant manipulation suitable for healthcare and industrial tasks [].

PAMs also enable sophisticated bioinspired and bionic soft robotic systems [,,,,,,,,]. Recent applications span a wide range of land, sea, and air bioinspired robots. Examples include a reconfigurable bionic flower [], the PALAM earthworm robot using peristaltic PAM actuation [], shown below in Figure 14, a manta ray swimmer with bistable wings [], and an anguilliform swimmer with data-driven control [].

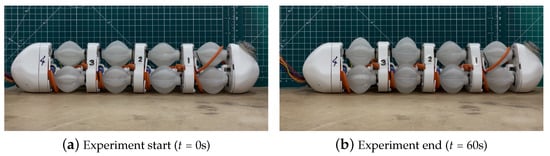

Figure 14.

Peristaltic motion sequence and elongated state of the PALAM robot tested on an uncoated wooden surface. Photos of the start (a) and the end (b) of the experiment (40 mm in 60 s) [].

Large-scale continuum systems also benefit from PAMs: Niikura et al. [] built a giraffe-neck robot with 14 PAM-driven DOFs for adaptive postures, while Doi et al. [] created an octopus-inspired arm with 32 micro-McKibbens for bending, torsion, and stiffness modulation.

Another emerging trend is the integration of secure control architectures into PAM-driven soft robots. A recent study [] addressed cybersecurity for human-centric soft robots by embedding homomorphic encryption into PI controllers, protecting control parameters and signals from cyber-attacks. The system also employed real-time anomaly detection and fail-safe protocols to ensure operational safety in medical and industrial robotics. This work highlights the need for integrating cryptographic security with pneumatic systems to enable safe and trustworthy human-robot interaction in networked environments.

PAM-driven soft robots combine adaptability, safety, and powerful actuation, allowing compliant structures to interact with unstructured environments while maintaining high load capacity relative to weight. Their ability to deform continuously and distribute forces makes them well-suited for applications requiring delicate manipulation or human contact. However, practical deployment is still limited by nonlinear dynamics, hysteresis, and air compressibility, which complicate precise motion control and energy efficiency [,]. Long-term cyclic operation also raises concerns about fatigue and leakage in flexible components, especially under high-frequency actuation []. Together, these advances and remaining challenges highlight PAMs’ versatility in soft robotics, from miniature manipulators to large continuum robots, while ongoing developments in origami-based (Section 2.2.7), hybrid (Section 2.2.8), and reconfigurable designs (Section 2.2.6) continue to enable programmable morphologies, multi-modal actuation, and adaptive, secure control for next-generation biomedical and collaborative robotic systems.

3.1.4. Industrial Automation

PAMs are increasingly adopted in industrial automation due to their high force-to-weight ratio, compliant motion, and safe interaction with humans. Unlike rigid actuators, they adapt force output naturally, making them well-suited for manipulators, grippers, and inspection robots in environments that demand lightweight, flexible, and cost-effective solutions. Current trends emphasize extending actuator lifetime, improving control precision, and integrating PAMs into modular or hybrid systems.

Commercially, one of the most mature examples of pneumatic artificial muscles is the Festo Fluidic Muscle series (DMSP and MAS), representing one of the few fully industrialized PAM products available worldwide. These actuators are explicitly designed as ready-to-install pneumatic drives for industrial use and are mass-produced in diameters ranging from 10 mm to 40 mm and lengths up to 9 m []. They operate at pressures up to 0.8 MPa, generating tensile forces from approximately 600 N (DMSP-10) to 6000 N (DMSP-40), with contraction ratios up to 25% of the nominal length []. The Fluidic Muscle series is used in a wide range of automation systems, including belt tensioning, clamping, vibratory feeders, and positioning units, demonstrating reliable operation at cycle rates up to 150 Hz [].

Festo fluidic muscles have been tested in industrial manipulators []. One system featured a four-link arm capable of vertical and horizontal load positioning under 0.1–0.7 MPa pressures and 2.5–7.5 kg payloads, with hydraulic damping reducing dangerous velocities from 5.7 m/s to 1.5 m/s during sudden load detachment. The actuators demonstrated durability up to five million cycles, while maintaining manual operability (≤50 N), making them attractive for safe and versatile manufacturing applications.

Beyond large-scale actuators such as Festo’s DMSP and MAS series, S-Muscle Co., Ltd. (Kurashiki, Okayama, Japan) has also commercialized miniature pneumatic artificial muscles for wearable and precision applications. Their EM-series thin McKibben muscles, available in diameters of 2–5 mm and operating pressures up to 0.5 MPa, achieve contraction ratios of approximately 25% and endurance exceeding one million cycles at 0.3 MPa [,].

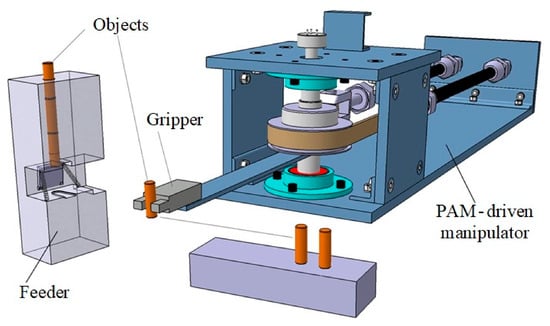

Antagonistic configurations further enable bidirectional torque control and adjustable stiffness. A single-joint manipulator using Festo MAS-10-220 N muscles (Festo Vertrieb GmbH & Co. KG, Esslingen am Neckar, Germany) and proportional valves, shown below in Figure 15, achieved stable angular displacement (±10°) with 2 s settling time, supporting precise gripping and feeding tasks [].

Figure 15.

CAD model of the system for sorting tasks [].

Mechanical refinements, such as eccentric pulleys, help mitigate torque decline at high displacements, while fuzzy adaptive and model-free control strategies improve position accuracy despite nonlinearities and hysteresis.

Beyond manipulators [], PAMs also enable compact robotic platforms for inspection and maintenance. A single-actuator McKibben robot used 3D-printed buckling ribbons to generate directional friction, enabling locomotion through horizontal, vertical, bent, and water-filled pipelines []. The system’s low structural complexity and simple on/off control highlight PAMs’ potential for reliable, low-cost deployment in oil, gas, and chemical industries.

Recent work on bio-inspired Soft Origami Vacuum Actuators (SOVAs) [] also shows strong industrial relevance. Manufactured entirely with low-cost fused deposition modeling (FDM) 3D printers, these actuators achieve bending under negative pressure, eliminating burst risks typical of positive-pressure designs. TPU-based SOVAs demonstrated rapid actuation (up to 4.55 Hz) and durability exceeding 123,000 cycles. Their scalability, modularity, and resilience make them attractive candidates for adaptive grippers, reconfigurable manipulators, and distributed robotic systems where affordability and robustness are critical.

PAM-based actuators have shown broad applicability in industrial automation, enabling manipulators, adaptive grippers, and inspection robots that combine high force output with compliant, inherently safe motion. Their ability to absorb impact and adapt to varying loads makes them well-suited for collaborative and flexible manufacturing environments. However, industrial adoption remains constrained by pneumatic infrastructure requirements, air leakage, and maintenance of elastomeric components, which affect long-term reliability and operating costs [,,]. Achieving repeatable, high-precision positioning also demands advanced control strategies to compensate for hysteresis and compliance. Together, these studies illustrate the versatility of PAMs in industrial automation, spanning manipulators, adaptive grippers, inspection robots, and modular systems. Advances in reconfigurable (Section 2.2.6) and hybrid PAMs (Section 2.2.8) further promote industrial adoption by offering adjustable stiffness, enhanced modularity, and precise control. As material durability and control algorithms continue to mature, PAM-based actuators are expected to play an increasingly important role in safe, flexible, and energy-efficient robotic manufacturing.

3.2. Non-Traditional Applications

Beyond classical roles in rehabilitation, exoskeletons, and industrial automation, pneumatic artificial muscles are increasingly applied in unconventional domains. Their nonlinear dynamics, compliance, and morphological adaptability make them well-suited for emerging areas such as embodied computation, adaptive architecture, and bio-inspired space technologies. At the same time, their expressive and organic motion qualities have attracted interest in art, education, and entertainment, where PAMs are used for interactive installations and kinetic sculptures. These non-traditional applications reflect a shift toward integrating computation, sensing, and actuation directly into actuator bodies, supporting new paradigms of morphological intelligence, responsive environments, and creative robotics. The following subsections highlight representative examples.

3.2.1. Embodied Computation

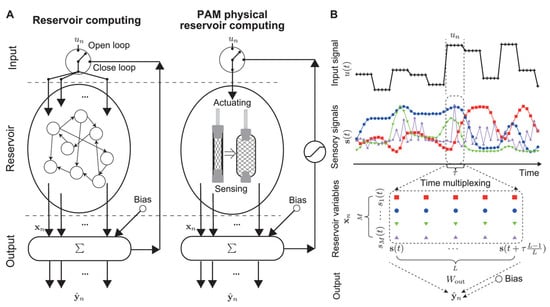

PAMs are increasingly explored as unconventional computational media through the paradigm of physical reservoir computing (PRC). This approach exploits PAMs’ intrinsic nonlinear dynamics, including hysteresis and bifurcation phenomena, to embed information processing directly within their material structure. Instead of serving solely as actuators, PAMs act as high-dimensional reservoirs whose physical states can generate, transform, and adapt dynamic patterns without external controllers (see Figure 16) [].

Figure 16.

(A) Schematic comparison between conventional reservoir computing using a neural network and physical reservoir computing (PRC) implemented with a pneumatic artificial muscle (PAM); solid arrows indicate signal flow and dashed lines denote feedback pathways. (B) Example of a time-multiplexing scheme used to generate reservoir states [].

Recent studies have shown that PAMs trained on chaotic inputs can autonomously produce periodic motions, while load changes (e.g., from 100 N to 250 N) trigger bifurcation-driven transitions between stable, mixed, or chaotic phases []. Such behavior functions as “mechanical reprogramming,” enabling PAMs to generalize across qualitatively different tasks without exhaustive retraining. By leveraging morpho-physical properties such as rubber conductivity or time-multiplexed sensor responses, PRC in PAMs reduces reliance on external pattern generators and silicon hardware.

The integration of computational capability into pneumatic artificial muscles opens new possibilities for adaptive systems that can learn and respond through their physical dynamics. PAM-based physical reservoir computing enables robots to self-adjust grip forces, generate rhythmic motion, and perform complex behaviors such as chaotic terrain navigation without centralized controllers. However, realizing such mechanically intelligent systems requires precise tuning of material properties, stable coupling between sensing and actuation, and mitigation of environmental noise that can destabilize nonlinear responses []. These challenges underscore the need for standardized modeling frameworks to reliably translate dynamic physical states into consistent computational outputs. Nonetheless, the emerging fusion of actuation, sensing, and computation within PAMs embodies the principles of morphological intelligence, resonating with broader innovations in hybrid (Section 2.2.8) and reconfigurable architectures (Section 2.2.6). Together, these developments position PAMs as programmable dynamical systems for adaptive, resilient, and self-organizing soft robotics.

3.2.2. Aerospace and Space Exploration

Pneumatic artificial muscles are increasingly explored for aerospace and space applications, where their high force-to-weight ratio, compliance, and mechanical simplicity provide advantages over conventional actuators. Unlike motors or hydraulics, PAMs deliver lightweight, safe, and adaptable actuation-critical for mass- and energy-limited environments such as spacecraft, aircraft, and planetary rovers.

PAMs are being integrated into smart space suits and wearable exoskeletons to assist astronauts during extravehicular activities (EVAs), where suit stiffness impedes dexterity. Projects like STAMAS have developed biofeedback suits with artificial muscle actuators to mitigate microgravity-induced muscle atrophy and bone loss, providing resistance and assistance during exercise and daily tasks on the ISS []. Wearable PAM-based devices are also being developed to offer resistance training and rehabilitation for astronauts.

Beyond wearables, PAMs are being deployed in robotic arms and manipulators for spacecraft and planetary rovers. Their compliance reduces the risk of damage during unplanned environmental contact: a key advantage for delicate operations in space []. PAMs and other artificial muscles have also been proposed for miniature wipers to clear dust from optical sensors and windows on planetary rovers, maintaining visibility and sensor performance in harsh environments [].

A pioneering aerospace-related application of chemically powered pneumatic muscles was the Reciprocating Chemical Muscle (RCM), developed for Georgia Tech’s micro air vehicle “Entomopter” program [,]. The RCM generated pneumatic pressure through the catalytic decomposition of monopropellants, enabling self-contained flapping-wing propulsion for flight in low-Reynolds-number environments []. This approach demonstrated how chemical-pneumatic hybrid muscles could power small-scale aerial vehicles without external compressors, an early milestone linking soft actuation to bioinspired flight control.

A notable example is the 7-DOF space-rated robotic arm developed by the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory [], which achieved a payload-to-mass ratio exceeding 5:1 by embedding pneumatic control components within the bladder, cutting gas consumption by 40% and outperforming conventional electric arms.

While pneumatic actuation offers high force-to-weight and intrinsic compliance, repeated use of gas-driven PAMs in long-duration missions would require onboard gas recycling or resupply, presenting a trade-off against the gradual energy decay of battery- or solar-based electric actuation. These considerations remain largely unaddressed in current studies and warrant future system-level analysis.

In aeronautics, PAMs enable morphing wings, ailerons, and trailing-edge flaps, supporting real-time aerodynamic surface reconfiguration. X-frame PAM-driven mechanisms have demonstrated 100% wingspan extension, generating forces up to 500 lbs at 90 psi, with ±40° flap deflection at 40 Hz and fatigue endurance exceeding 120 million cycles. Such traits make PAMs promising replacements for hydraulic actuators in flight control systems [,]. Thermal management has also been addressed: embedding perforated metal pipes within PAMs reduced localized heating by up to 30%, extending operational lifespan under repetitive cycles [].

PAMs show significant promise for aerospace and space exploration, where their lightweight construction, high force-to-weight ratio, and inherent compliance offer advantages over conventional electromechanical or hydraulic actuators. Their adaptability makes them well-suited for morphing structures, astronaut-assistive exosuits, and compact robotic manipulators operating under variable pressure and gravity conditions. Nevertheless, practical implementation in these environments remains challenging due to gas storage and recycling requirements, temperature- and radiation-induced material degradation, and stringent reliability standards demanded for long-duration missions [,,]. Overcoming these constraints will require advances in fatigue-resistant materials, closed-loop pneumatic systems, and thermal regulation strategies to ensure consistent performance in extreme conditions. Overall, PAMs exhibit strong potential for aerospace and space exploration, combining lightweight design, fatigue resistance, and adaptable architectures. Ongoing progress in origami-based (Section 2.2.7), hybrid (Section 2.2.8), and reconfigurable PAMs (Section 2.2.6) will further enhance modularity, efficiency, and system-level integration, positioning these actuators as key enablers of future morphing aircraft, astronaut support systems, and space-rated robotic platforms.

3.2.3. Adaptive Architecture

Pneumatic artificial muscles and soft robotic actuators are increasingly explored in adaptive architecture and dynamic building systems, where their compliance, energy efficiency, and programmable deformation provide distinct advantages over rigid mechanisms. This emerging field aims to create kinetic, responsive environments capable of interacting with both occupants and external conditions.

A notable example is the Soft Robotic Pad (SRP) developed by Sun et al. [], a pneumatically driven, fiber-constrained actuator capable of large-scale programmable morphing. Modular SRPs (90 × 90 mm) achieved forces up to 12.9 N at 130 kPa and demonstrated 2D–3D transformations suitable for adaptive facades, airflow regulation, or morphing furniture. Their compliant nature makes them ideal for ergonomic furnishings, partitioning systems, and kinetic art, though challenges such as weatherproofing and pneumatic efficiency remain.

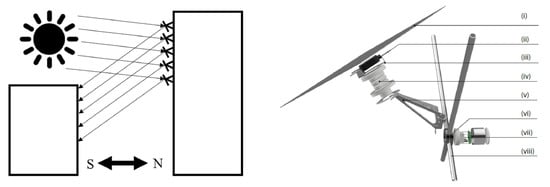

Complementing this work, dynamic photovoltaic (PV) building envelopes powered by hybrid pneumatic actuators with variable stiffness were developed [,]. Their two-axis tracking system increased energy yield by 50% compared to static facades, while providing shading and thermal regulation. Tested under harsh outdoor conditions, the actuators achieved >30,000 cycles with minimal energy consumption, highlighting the feasibility of industrial-scale adaptive facades. The envisioned interactions of reflective adaptive solar facades (RASF) with incoming direct sunlight, as well as the detailed panel design incorporating soft pneumatic actuators, are illustrated in Figure 17 [].

Figure 17.

Envisioned interactions between incoming direct sunlight heat-fluxes and buildings enabled by the RASF (i) PV panel (ii) junction box (iii) panel adaptor (iv) PAM (v) cantilever (vi) electronic and pneumatic plug (vii) electronic shield (viii) rod net structure [].