Abstract

This study proposes an electromagnetic balance-based structural design and shim plate application to improve the response characteristics of an electromagnetic brake. Electromagnetic brakes typically experience response delay due to inductive effects and residual magnetic flux after power-off. To address this issue, the inner and outer thicknesses of the stator were parameterized to achieve balanced magnetic flux distribution, and a non-magnetic shim plate (SUS 304) was applied to reduce residual flux within the electromagnet. Finite element analysis (FEA) was conducted to evaluate the influence of structural parameters on the magnetic flux balance and attractive force. The optimized stator geometry provided a stable electromagnetic balance, and the shim plate effectively reduced the response delay and improved the overall response performance compared with the conventional design. These findings demonstrate that the proposed electromagnetic balance design combined with shim plate application is an effective approach to enhance the reliability and control responsiveness of electromagnetic brakes, with potential applicability to robotic and industrial actuator systems.

1. Introduction

With the growing demand for automation and safety in various industrial applications, the requirement for braking systems offering fast response and high operational reliability has increased significantly. Electromagnetic brakes (EMBs) are widely utilized in military, robotic, medical, and automotive systems, as they can provide fail-safe braking in power-off conditions or dynamic braking during emergency operations, depending on their structural design. An EMB typically comprises a solenoid-type configuration consisting of an armature, spring, coil winding, and stator. Unlike conventional hydraulic brake systems that rely on fluid transmission, EMBs operate solely via magnetic actuation and are inherently free from failure modes such as fluid leakage or pressure loss, resulting in higher reliability and reduced maintenance requirements [,].

Solenoid-based electromagnetic brakes (EMBs) require a continuous holding current to maintain their engaged state, making it essential to generate sufficient magnetic force and establish efficient magnetic flux paths through proper electromagnetic design. However, due to the inductive characteristics of the solenoid coil, a delay in current rise occurs when voltage is applied, resulting in slower dynamic responses during both attraction (pull-in) and release operations. During the release phase, the current decay after power-off leaves residual magnetic flux trapped in the stator core, which prolongs the release delay time and adversely affects the overall response and safety of the braking system. In addition, various mechanical factors and magnetic force asymmetry can induce imbalance between the inner and outer regions, which deteriorates braking uniformity and dynamic stability [,,]. To overcome these limitations, this study proposes a structural optimization approach for the electromagnetic brake. The optimization aims to enhance magnetic balance and improve mechanical symmetry while minimizing the delay caused by residual magnetism. In particular, a shim-assisted configuration is introduced between the armature and stator. The inserted shim functions as a controlled stroke gap that helps to equalize the magnetic flux distribution, suppress residual magnetic effects, and reduce the release delay time. This configuration ultimately improves both the electromagnetic responsiveness and operational reliability of the brake.

2. Principle and Design of Electromagnetic Brake

2.1. Principle of the Electromagnetic Brake

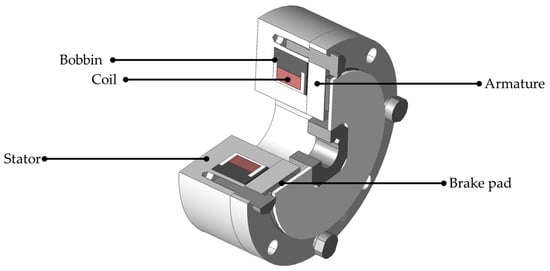

The structure of the electromagnetic brake is shown in Figure 1. The brake consists of a stator, armature, coil, bobbin, brake pad, etc. A winding is wound around the stator, and when current is applied, the stator becomes magnetized and acts as an electromagnet. The resulting magnetic attraction force pulls the armature toward the stator, enabling the braking mechanism.

Figure 1.

Structure of the proposed electromagnetic brake.

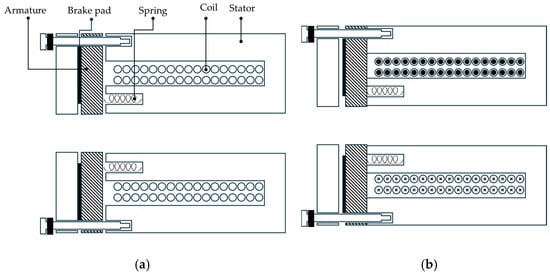

The operating principle of the brake is illustrated in Figure 2a, which shows the braking mode, in which the power is not applied. In this state, the spring restoring force presses the armature toward the brake pad, generating the braking torque. In contrast, Figure 2b shows the release mode, where the power is applied. When current flows through the coil, a magnetic field is generated, and the armature is attracted toward the stator, causing the friction surfaces to separate and allowing the rotor shaft to rotate freely.

Figure 2.

Working states of conventional spring-friction brake. (a) “power off” state (b) “power on” state.

The electromagnetic brake operates through the interaction between magnetic attraction and spring restoring force depending on whether the power is applied or not.

This operating principle is mathematically formulated in Section 2.2.

2.2. Fundamental Theoretical Equations of the Electromagnetic Brake

The braking characteristics of an electromagnetic brake are determined by the interaction among electromagnetic attraction force, spring restoring force, and frictional force. To quantitatively analyze these characteristics, this section formulates the fundamental operating principles of the electromagnetic brake. The braking torque is generated by the compressive force of the spring and the friction coefficient at the contact surface, while during power-on conditions, the magnetic attraction force produced by the coil current overcomes the spring restoring force, thereby releasing the brake.

Therefore, the braking torque and magnetic attraction force are the key physical quantities that govern the brake’s performance, and their mathematical relationships are presented in this section.

2.2.1. Calculation of Braking Torque

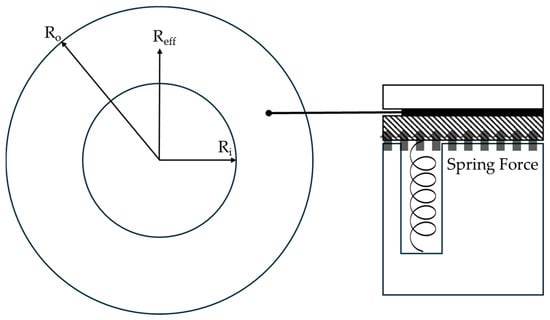

To calculate the holding torque required for brake design, the braking torque can be determined from the effective radius of the friction surface and the coefficient of friction. Figure 3 shows the relationship between the friction surface and the spring force. and represent the outer and inner radii of the friction surface, respectively, and the effective radius is approximated as . Although in practical electromagnetic brake designs the normal force is concentrated near the outer region due to spring placement, the uniform-wear assumption is adopted here to simplify the torque derivation. This assumption provides a reasonable approximation of the effective braking radius. The braking torque is derived from the relationship between the frictional force and the effective radius of the contact surface. Equations (1)–(3) present the step-by-step formulation of the spring force and normal pressure acting on the friction surface, and the final expression for the braking torque is obtained in Equation (4) based on these parameters. denotes the coefficient of friction of the brake pad, is the spring restoring force, is the spring constant, is the number of springs, and represents the spring compression displacement [].

Figure 3.

Principle of Braking Torque.

2.2.2. Calculation of Electromagnetic Attraction Force

The electromagnetic brake moves the armature by using the magnetic force of the electromagnet to counteract the restoring force of the spring.

The attractive force generated in this process is derived through the Maxwell stress tensor, and the total force acting on an arbitrary surface in the magnetic field is defined in Equation (5).

is the Maxwell stress tensor, is the magnetic flux density vector, is the identity matrix, and is the permeability of free space. The total attractive force is calculated by integrating the stress tensor over the stroke gap surface, as expressed in Equation (6).

is the surface area, and is the normal vector of the surface. Since the electromagnetic brake has an axisymmetric cylindrical structure, Equation (6) can be simplified in cylindrical coordinates as shown below.

Assuming that the magnetic flux density in the stroke gap is uniformly distributed, Equation (7) can be simplified into an approximate expression using the average magnetic flux density, and the total attractive force is expressed as Equation (8).

where represents the effective area of the stroke gap, over which the Maxwell stress is integrated to obtain the total attractive force [,,].

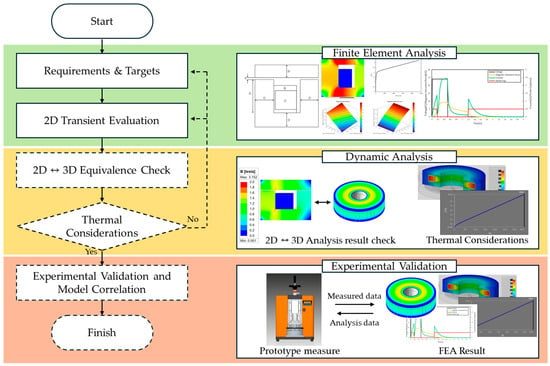

2.3. Workflow of the Proposed Electromagnetic Brake Design

The design procedure employed in this study is summarized in Figure 4. The sections indicated by solid lines represent the scope actually conducted in this work, which includes defining the design requirements, performing 2D transient finite element analysis, and verifying the equivalence between 2D and 3D models for the selected geometry. Through these steps, the fundamental electromagnetic characteristics of the brake were evaluated.

Figure 4.

Brake Design Workflow.

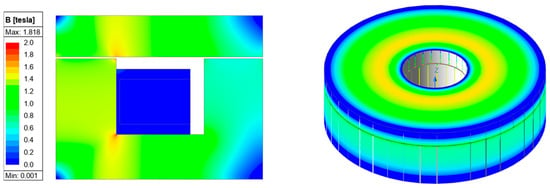

As shown in Figure 5, the attractive force of the brake was compared using both 2D and 3D Ansys Maxwell simulations. The resulting forces were 3.04 [kN] (2D) and 3.06 [kN] (3D), demonstrating that the two results are quantitatively very similar. In contrast, the computation time required for the 3D simulation was significantly longer than that of the 2D model under identical conditions. Considering the axisymmetric geometry of the brake and the strong numerical agreement between the 2D and 3D results, it is reasonable to adopt the 2D analysis as the primary design tool during the initial design and parameter-study stages, particularly from the perspective of computational efficiency. Meanwhile, the steps indicated by dashed lines represent extended research activities planned for future studies. These include thermal considerations—such as evaluating the effect of temperature rise on electromagnetic performance—as well as prototype fabrication and benchtop experiments for model correlation.

Figure 5.

Magnetic flux density comparison of the 2D and 3D models.

In the present study, the focus was placed on analyzing the fundamental structure and response characteristics of the electromagnetic brake, and the derived design results will be used as the basis for subsequent experimental validation and coupled thermal–electromagnetic analysis.

2.4. Comparison of Solenoid Structures

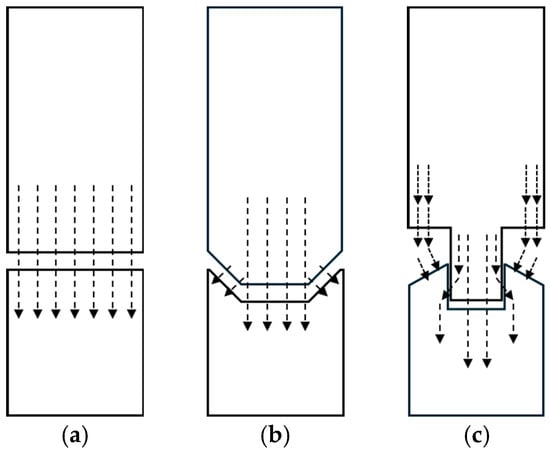

The solenoid geometry directly affects the magnetic flux distribution and the attractive force characteristics. As shown in Figure 6, typical solenoid configurations include flat, conical, and proportional structures. Among them, the flat and conical types are applicable to electromagnetic brake designs, and their characteristics are as follows.

Figure 6.

Solenoid structures: (a) Flat type, (b) Conical type, and (c) Proportional type.

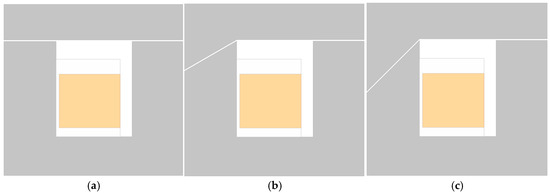

The flat structure has a planar contact surface between the stator and the armature, resulting in a uniform magnetic flux distribution and a simple geometry that requires low machining precision. Since the total magnetic flux is transferred through a constant area, the magnetic saturation occurs gradually. In the conical structure, the inclined magnetic path allows the magnetic flux to be concentrated, resulting in a higher initial attraction force under the same current condition []. However, this effect tends to decrease as the stroke gap increases. This configuration was applied to the electromagnetic brake, as shown in Figure 7 [,].

Figure 7.

Comparison of electromagnetic brake geometries. (a) Flat type, (b) Conical type (30°), and (c) Conical type (45°).

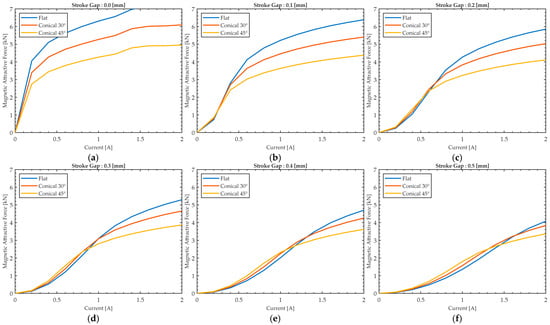

To evaluate how these geometric differences influence the magnetic attraction force, a finite element analysis (FEA) was performed using Ansys Maxwell. In this study, two types of electromagnetic simulations were conducted:

(1) Magnetostatic analysis, used for parametric and sensitivity studies to examine how variations in geometry and excitation affect flux distribution and attraction force; and (2) Transient analysis, used to capture time-dependent electromagnetic behavior, including pull-in and release responses.

A current-source-based parametric study was conducted across the following ranges: excitation current from 0 to 2 A, stroke gap from 0 to 0.5 mm, and conical pole angle from 0° to 45°. The resulting attraction-force characteristics for each geometry are shown in Figure 8, which illustrates how the three models behave across varying stroke gap lengths. When the stroke gap is relatively large (0.2–0.5 mm) or the excitation current is small (below approximately 0.8 A), the conical models exhibit a slightly higher attractive force than the flat model. This occurs because the inclined magnetic path effectively reduces the local stroke gap and increases flux linkage in the low-excitation regime. However, as the current increases or the stroke gap decreases, this advantage diminishes and eventually reverses. At higher current levels, the flat model produces a slightly larger attractive force due to its more uniform flux distribution and delayed magnetic saturation. For example, at a stroke gap of 0.5 mm and an excitation of 0.4 A, the 45° conical model produces approximately 16.4% greater force than the flat model; however, at 2.0 A, the flat model exhibits approximately 9.8% greater force than the 45° conical model.

Figure 8.

Comparison of attraction forces according to stroke-gap length. (a) 0.0 [mm] (b) 0.1 [mm] (c) 0.2 [mm] (d) 0.3 [mm] (e) 0.4 [mm] (f) 0.5 [mm].

Therefore, the conical pole shape provides a small advantage in the low-current or large-gap region, whereas the flat structure becomes more efficient in the high-current or small-gap region due to its uniform flux distribution and lower susceptibility to early saturation.

3. Performance Improvement Analysis Through Electromagnetic Balance and Shim Structure Application

This section presents a stator design approach aimed at improving the performance of the electromagnetic brake. Since the brake operates based on the attractive force generated by the electromagnet, an imbalance in the stroke gap magnetic flux can degrade control stability and reduce the maximum achievable attractive force [,]. In addition, residual magnetic flux remaining in the stator core after power-off may cause a response delay.

To mitigate these issues, this study proposes an electromagnetic design method that ensures a balanced and symmetric stroke gap flux distribution, together with a shim-assisted structure that reduces the response delay induced by residual flux.

3.1. Design Considering Electromagnetic Balance

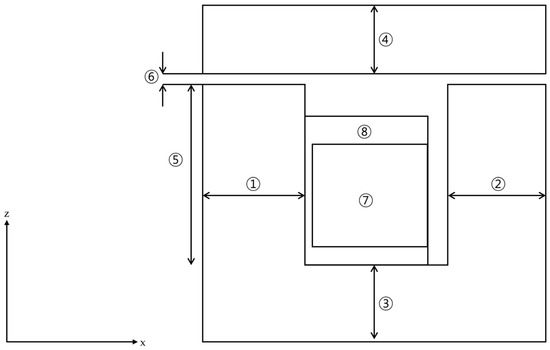

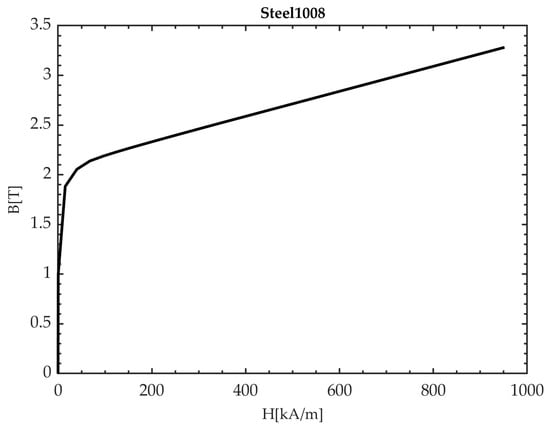

The analysis was performed using magnetostatic finite element analysis to investigate the electromagnetic balance between the stator and the armature. To achieve a uniform distribution of magnetic flux density, the inner length (①) and outer length (②) of the stator, as indicated in Figure 9, were selected as the primary design variables. The overall geometry and definitions of the geometric parameters are shown in Figure 9, and their corresponding numerical values are summarized in Table 1. Parametric simulations were then carried out by varying the ratio between these two parameters to evaluate their effects on the magnetic flux distribution and attractive force characteristics. Figure 10 presents the B–H curve of Steel 1008, which is used as the magnetic material for both the stator and the armature. The material also exhibits an electrical conductivity of approximately 2.0 × 106 S/m, reflected in the finite-element analysis. The magnetic flux density of the electromagnet is determined by this material property in combination with the applied current and number of coil turns.

Figure 9.

Geometry of the electromagnetic brake model and definition of geometric parameters (①–⑧ correspond to the parameters listed in Table 1).

Table 1.

Geometric parameters of the electromagnetic brake model.

Figure 10.

B–H curve of Steel 1008.

In this study, the inner–outer balance of the electromagnetic attractive force is evaluated using the ratio of the inner attractive force to the total attractive force, as defined in Equation (9).

Here, the inner attractive force corresponds to the force generated in the region labeled as Area ① (inner region), and the outer attractive force corresponds to Area ② (outer region), as illustrated in Figure 9.

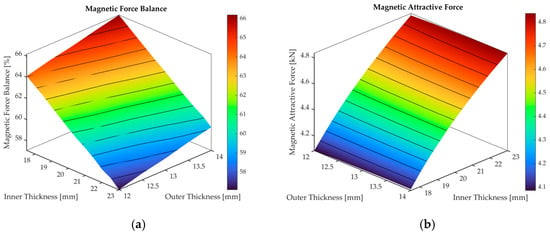

By setting the inner and outer lengths of the stator as variables, the conditions for achieving electromagnetic balance were derived through the analysis of magnetic flux distribution and attractive force variations. The magnetic flux path and attractive force characteristics for each parameter combination were compared. The degree of balance in the magnetic attraction force was evaluated by calculating the ratio of the inner attractive force to the total attractive force. A smaller ratio indicates a more uniform flux distribution and a better electromagnetic balance between the stator and armature. The results are shown in Figure 11, where the configuration with the lowest ratio and highest total attraction force was selected as the optimal model. Consequently, the most balanced magnetic performance was achieved when the inner length was 23 [mm] and the outer length was 13 [mm].

Figure 11.

Magnetic analysis results according to the variation in inner and outer thickness of the stator. (a) magnetic force balance (b) magnetic attractive force distribution.

3.2. Analysis of Response Characteristic Improvement by Shim Plate Application

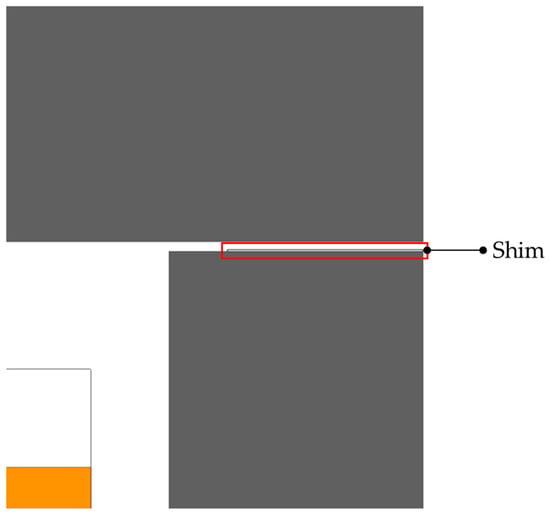

Residual magnetism remaining in the stator after power-off prolongs the release delay time, which not only degrades dynamic responsiveness but also limits the achievable precision of brake control. To alleviate this limitation, a shim-assisted structure is introduced to accelerate magnetic flux decay and reduce the delay induced by residual magnetism. A shim plate is a thin, non-magnetic spacer typically employed for alignment or gap adjustment. In this study, SUS 304 was selected as the shim material because its relative magnetic permeability is nearly equal to that of air (μ ≈ μ0), allowing it to act as a controlled magnetic barrier rather than a flux carrier. The electrical conductivity of SUS 304 is approximately 1.4 × 106 S/m, which is considerably lower than that of magnetic steels. To suppress eddy-current effects and isolate the geometric influence of the shim, it was modeled as an electrically non-conductive layer in the finite element analysis. This modeling approach ensures that the shim’s influence on the magnetic circuit arises solely from its geometry and magnetic permeability, excluding any induced-current interaction. When a shim of 0.1 mm thickness is inserted between the stator and the armature, a small initial magnetic separation is introduced, which prevents complete magnetic saturation and reduces the retention of residual flux. As shown in Figure 12, the shim was placed between the stator and the armature to implement this configuration. Although this modification slightly decreases the maximum attractive force due to the increased magnetic reluctance, it dramatically improves the release response. The apparent 0.4 mm armature displacement observed during release originates from the nonlinear relationship between magnetic force and stroke gap length—once the magnetic attraction drops below a critical level, the restoring spring rapidly pulls the armature back. In addition to its magnetic effect, the shim also functions as a mechanical alignment aid, ensuring a consistent and uniform stroke gap during assembly. This alignment compensation mitigates flux imbalance caused by mechanical tolerances, thereby enhancing both the magnetic and mechanical stability of the brake. Consequently, the proposed shim mechanism provides a favorable trade-off: it slightly reduces the holding force but significantly shortens the release delay, leading to faster and more stable braking performance.

Figure 12.

Shim Structure.

The simulation results were compared with those of the conventional brake model. When the power supply is switched off, the current decay in the excitation coil follows the first-order RL differential equation, as shown in Equation (10).

where and denote the inductance and resistance of the coil, respectively. Solving Equation (9) yields the exponential decay expression given in Equation (11).

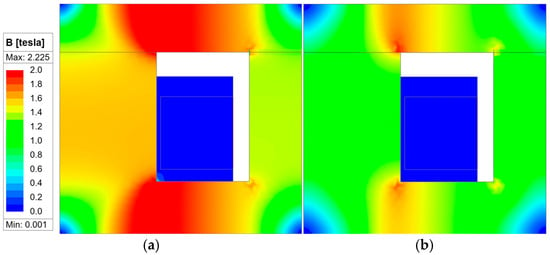

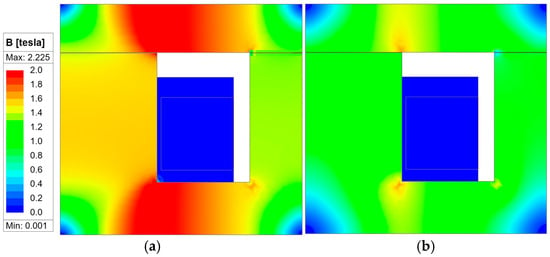

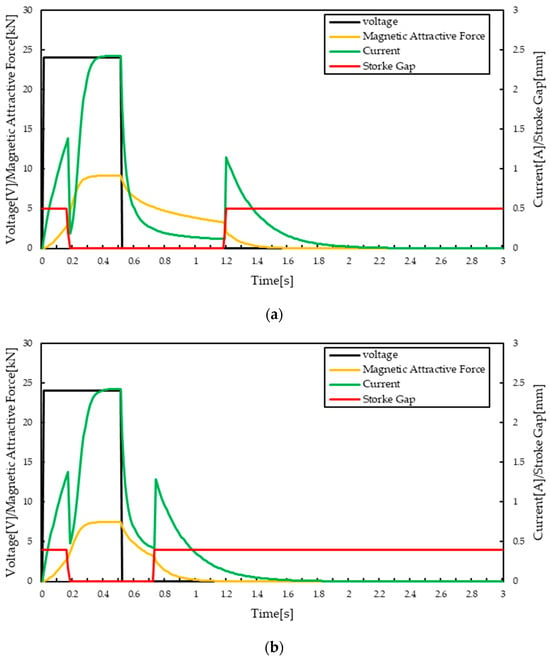

This result indicates that the electrical time constant τ, defined as τ = L/R, governs the rate at which the magnetic field collapses during power-off. A larger inductance or smaller resistance increases τ, resulting in a slower decrease in magnetic flux and consequently a longer release delay. In contrast, the proposed shim-assisted structure reduces magnetic retention in the stator core, enabling the flux to dissipate more rapidly than expected from the electrical time constant alone. Figure 13 and Figure 14 show the magnetic flux density distributions of the conventional and shim-assisted models, respectively, at t = 0.71 s, corresponding to the power-off phase when the coil current begins to decay. In the conventional model, strong magnetic saturation remains concentrated in the stator core, indicating residual magnetic flux that delays the release of the armature. In contrast, the shim-assisted model exhibits a visibly reduced flux density and weaker saturation near the stator–armature interface. This confirms that the introduction of the non-magnetic shim facilitates faster demagnetization by interrupting the magnetic path, leading to shorter release delay and improved response behavior. Furthermore, transient finite element analysis was performed to validate the dynamic electromagnetic response predicted by the RL model. The transient results confirmed that the shim-assisted configuration exhibits a faster decay of coil current and magnetic flux density during the power-off phase, which corresponds to the shortened release delay observed in the simulation. As shown in Figure 15 and Table 2, the conventional brake exhibited a release delay of 680 [ms] with a peak attractive force of 9.14 [kN], whereas the model incorporating the shim reduced the delay to 210 [ms] with a peak force of 7.49 [kN]. Although the introduction of the non-magnetic shim decreases the maximum attractive force due to the increased magnetic reluctance, the overall braking performance is enhanced because the faster demagnetization enables a quicker and more stable release behavior. This result demonstrates that the shim effectively trades a reduction in holding force for a substantial improvement in dynamic response speed.

Figure 13.

Magnetic Flux Saturation Distribution of the Conventional Model (a) 0.5 [s] (b) 0.71 [s].

Figure 14.

Magnetic Flux Saturation Distribution of the shim Model (a) 0.5 [s] (b) 0.71 [s].

Figure 15.

Transient Electromagnetic and Mechanical Response of the Brake. (a) Conventional model (b) shim model.

Table 2.

Comparison of response delay characteristics of the electromagnetic brake with and without the shim structure.

4. Conclusions

In this study, a design approach based on electromagnetic balance and the application of a shim plate were proposed to improve the overall performance of an electromagnetic brake. The stator geometry was optimized to maximize the attractive force, and the validity of the design was verified through finite element analysis (FEA). The analysis results confirmed that adjusting the ratio between the inner and outer thicknesses of the stator can balance the magnetic flux distribution and minimize the variation in attractive force. Furthermore, to address the release delay caused by residual magnetic flux after power-off, a non-magnetic shim plate (SUS 304) was applied, resulting in a significant reduction in release delay time and enhanced operational responsiveness. Although the shim reduces the maximum attractive force due to increased magnetic reluctance, it does not compromise braking capability or stability. Instead, it accelerates the collapse of residual flux and enables faster and more reliable release behavior.

Overall, the combination of electromagnetic-balance-based stator design and shim application proves to be an effective method for improving both the performance and operational stability of electromagnetic brakes. Future work will incorporate thermal considerations and experimental validation to further substantiate the simulation results and evaluate temperature-dependent effects under practical operating conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.-H.K., H.-J.P. and H.-J.L.; methodology, D.-H.K.; investigation, D.-H.K.; resources, C.-H.K. and H.-J.L.; writing—original draft, D.-H.K.; writing—review and editing, D.-H.K., C.-H.K., H.-J.P. and H.-J.L.; supervision, H.-J.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported in part by the Materials and Components Technology Development Program through the Korea Evaluation Institute of Industrial Technology (KEIT) (RS-2004-00432477) and in part by the Human Resource Development Program for Industrial Innovation (GLOBAL) through the Korea Institute for Advancement of Technology (KIAT) (RS-2024-00435841), both funded by the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy (MOTIE).

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Li, C.; Zhuo, G.; Tang, C.; Xiong, L.; Tian, W.; Qiao, L.; Cheng, Y.; Duan, Y. A Review of Electro-Mechanical Brake (EMB) System: Structure, Control and Application. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Ju, H.; Yang, Y.; Guo, Z. An Optimized Permanent Magnet Brake Mechanism in Robot Joints. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 18278–18286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.-Y.; Li, G.-X.; Wang, L.; Wang, W.-H.; Gao, Q.-X.; Wang, J. Effects of structure parameters on the static electromagnetic characteristics of solenoid valve for an electronic unit pump. Energy Convers. Manag. 2016, 113, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’ANdrea, M.; Di Domenico, G.; Macera, D.; Fiume, F. Electromagnetic brakes in electromechanical actuators for aerospace applications. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Symposium on Power Electronics, Electrical Drives, Automation and Motion (SPEEDAM), Sorrento, Italy, 24–26 June 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 484–488. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.; Jia, S.; Ji, W.; Yang, C. Analytical Calculation and Verification of Radial Electromagnetic Force Under Multi-Type Air Gap Eccentricity of Hub Motor. World Electr. Veh. J. 2025, 16, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.-J.; Lee, J.-K.; Lee, K.-D.; Jung, D.-H. A Study on the Design of a Variable Power Electromagnetic Brake for Industrial Applications. Machines 2025, 13, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, H.; Yi, B.J. A New Design of Spherical Electro-Magnetic Brake System. In Proceedings of the 2018 15th International Conference on Ubiquitous Robots (UR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 26–30 June 2018; pp. 220–222. [Google Scholar]

- Plavec, E.; Filipović-Grčić, B.; Vidović, M. The impact of plunger angle and radius on the force and time response of DC solenoid electromagnetic actuator used in high-voltage circuit breaker. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2020, 118, 105767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, A.; Qaraei, P.Y. Cylindrical electromagnets: Modeling, analysis, simulation and implementation. COMPEL 2024, 43, 50–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, O.; Ulm, J. Theory of Proportional Solenoids and Magnetic Force Calculation. In Proceedings of the 2011 COMSOL Conference in Stuttgart, Stuttgart, Germany, 26–28 October 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Cheng, T.; Xuan, D.; Shen, Y. Force characteristic of a magnetic actuator for separable electric connector based on conical airgap. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2015, 7, 1687814015568941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, Y.; Kitamura, T.; Nakamura, K.; Takao, T. Levitation Force Improvement by Effective Magnetic Interaction in Two Magnetic Levitation Systems with HTS Coil and Bulks. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2020, 30, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, A.; Zainuri, M.A.A.M.; Che, H.S.; Ibrahim, A.A.; Rahim, N.A.; Alaas, Z.M.; Ahmed, M.M.R. A systematic review on current research and developments on coreless axial-flux permanent-magnet machines. IET Electr. Power Appl. 2022, 16, 1095–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).