Abstract

This research aims to investigate the practicality and feasibility of pneumatic muscle actuators (PMAs) applied in the pneumatic servo system. The mechanism consists of closed symmetrical planar robotic arms driven by two pairs of opposing PMAs, whose structure is similar to human arms. Importantly, the two distal links (or wrist parts) are combined into a collective end-effector, whose desired position is controlled only by the two shoulder angle joints. When two pairs of PMAs are attached to the upper arms, they actuate each shoulder and assist in the movement of the arms. However, the nonlinear behavior, high hysteresis, low damping, and time-varying characteristics of PMAs significantly limit their controllability. Therefore, to effectively address these challenges, a Fourier series-based adaptive sliding mode controller with (FSB-ASMC + ) is employed to achieve accurate path tracking of the PMAs. This control approach not only compensates for approximation errors, disturbances, and unmodeled dynamics but also ensures the desired positioning performance of the overall system. The controller method can not only effectively prevent approximation errors, disturbances, and un-modeled dynamics but can also ensure the required positioning performance of the whole system. Thus, the results of the experiment showed that the control strategy for the system collocating the FSB-ASMC + can attain excellent control performance.

1. Introduction

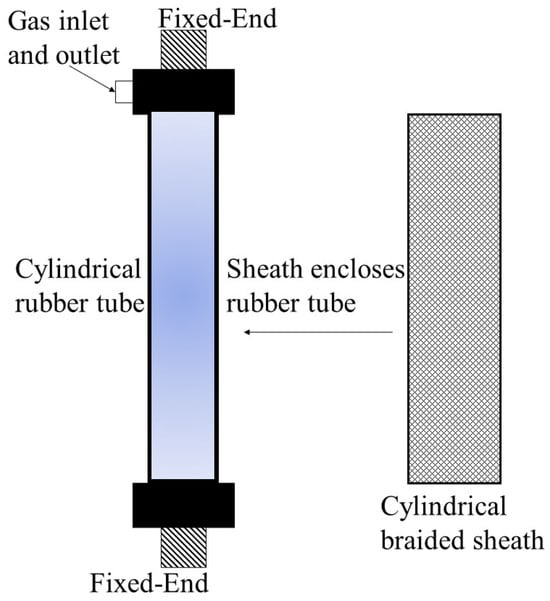

Pneumatic actuators have been widely applied in industrial automation since the mid-20th century, which emphasizes their reliability, low cost, high power-to-weight ratio, easy maintenance, cleanliness, and safety in operation. In recent years, the accessibility of low-cost microprocessors and pneumatic components has been made possible by using more complicated control methods in servo pneumatic control systems. One well-known type of pneumatic actuator is the McKibben artificial muscle, also referred to as the pneumatic muscle actuator (PMA), which possesses all the advantages of traditional pneumatic actuators (i.e., cheapness, lack of friction, and high power/weight and power/volume ratios). For this reason, PMAs have been used in robotics to perform manipulator tasks [1]. They consist of an inner rubber tube surrounded by a braided sheath with helical winding and both ends connected to the fitting. As shown in Figure 1, when the inner rubber tube is pressurized, the assembly diameter of the sheath and tube easily increases in the radial direction, and the PMA shortens in the axial direction, therefore generating the axial force.

Figure 1.

Structure of pneumatic muscle actuator.

The PMA system is inherently a passive device and classified as a “soft actuator” (due to its compliance). In case of structural failure, the risk of human injury is very low. One of the current trends is that the PMA system is used to actuate human exoskeleton suits (muscle suits) to enhance physical support and mobility assistance for humans. Such a muscle suit is usually designed to help patients who normally need assistance. It is also useful for manual work and rehabilitation [2,3,4]. However, it is difficult to control PMA technology in precision or forced applications. This is because they are nonlinear, hysteresis, and time varying. In order to overcome this problem, intelligent control approaches are currently being developed.

According to the past research on mathematical models of the PMA, Chou et al. [5] described static and dynamic characteristics of braided PM and modeling of pneumatic circuit dynamics. Reynolds et al. [6] developed a new phenomenological model for the dynamics of PM actuators. The model is a parallel arrangement of a spring element, damping element, and contractile force element. Davis et al. [7] have shown a new model of the force/displacement profile of pneumatic muscle-type actuators. Saga et al. [8] proposed the dynamic equilibrium conditions for the thickness of rubber and used Young’s modulus of artificial muscle contraction. Moreover, much research has been conducted on the performance of a dual pneumatic muscle system, where two opposing muscles are connected by a flexible, non-stretching timing belt over a pulley. When different air pressures are supplied to the muscles, the different equilibrium lengths cause changes in the equilibrium angle of the joint. Extensive use of PMA requires precise actuator control. Adaptive control [9,10], learning vector quantization neural network control [11], variable structure control [12], energy-efficient control [13], robust PID control [14], and self-organizing fuzzy control [15] have been applied to control the classified system, which was successful in addressing smooth actuator motion in response to step and/or sinusoidal inputs. A McKibben-type sleeve pneumatic muscle and integrated mechanism for improved stroke length was investigated [16]. A detailed overview of PAM force modeling, including static and dynamic models, and survey control strategies such as PID, adaptive, and model predictive control, was introduced [17].

Recently, conventional theoretical studies of robots controlled by PMAs, including industrial robots and wearable/rehabilitation robots, have shown the similarities with human arm motions. Many two-DOF SCARA robots have been proposed which are actuated by two pairs of PMAs. Sliding mode control [18], adaptive self-organizing fuzzy sliding mode control [19], PID control [20], and active force with fuzzy logic control [21] have been used to control a two-joint planar arm with opposing pairs of four PMAs. It shows simulation and experiment spatial tracking responses of the end-effector, including sinusoidal spline, vertical line, and circle motion. Furthermore, Kato et al. [22] developed a four-DOF pneumatic robot arm as a gripper, which incorporates two two-DOF modules as the slave system. In addition, they developed a main controller system that allows for the intuitive control of operation. One development in robotics is to use them to assist in activities of daily life. Kobayashi et al. [2] developed a wearable robot for physical support or human assistance, which achieved a new connection mechanism and a smooth shoulder movement. Tsai et al. [3] proposed the design and control of a one-DOF robotic lower-limb system driven by a single pneumatic artificial muscle. After that, Tsai et al. [4] continued to develop a two-DOF lower limb rehabilitation assistance training robot system driven by pneumatic artificial muscle systems. Muramatsu et al. [23] developed a wearable muscle suit, which enabled manual workers to lift weight and has indicated quantitative evaluation results for direct and physical motion support.

In the 1950s, the theory of variable structure control was developed by the Soviet Union scientist V. I. Emelyanov. The concept of this theory is to change the control system structure to handle uncertainty and external disturbance efficiently during transients [24,25]. Sliding mode control is one of the variable structure controls. With a discontinuous changing signal, the controller will force the system to approach the specific sliding surface and move forward to the target. In 1984, Slotine et al. [26] proposed the sliding mode control and applied the theory to real systems. Because of the characteristics of sliding mode control, currently, it is widely used in controlling nonlinear systems. Adaptive control is used by variable laws to overcome unknown parameters of a system. It can help us design the controller by estimating the uncertain parameters. But the uncertain parameters of traditional adaptive control must be constant or slowly time-varying. In 2006, Chen and Huang [27] applied an adaptive sliding controller in a vibration isolating system. To deal with these uncertainty problems, Fourier’s series-based functional approximation techniques have been used. Huang et al. [28] have suggested an adaptive sliding controller with a Fourier series-based functional approximation technique, which can handle the nonlinear system containing time-varying, uncertain parameters. Tsai et al. [29] proposed a FAT-based adaptive controller for pneumatic servo systems with variable payload and uncertain disturbances. Chiang et al. [30] proposed a Fourier series-based adaptive sliding mode controller with tracking performance (FSB-ASMC + ) for the rod-less pneumatic cylinder system. The proposed method can not only effectively prevent approximation errors, disturbances, and un-modeled dynamics, but can also guarantee a desired tracking performance for the overall system. Chiang et al. [31] applied the FSB-ASMC + controller to design the path tracking controllers with three vertical servo pneumatic actuators to realize the 3D path tracking control of the end-effector.

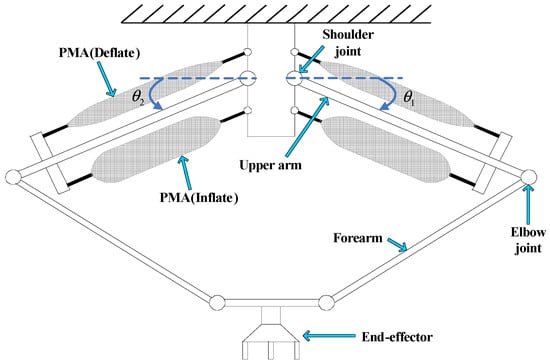

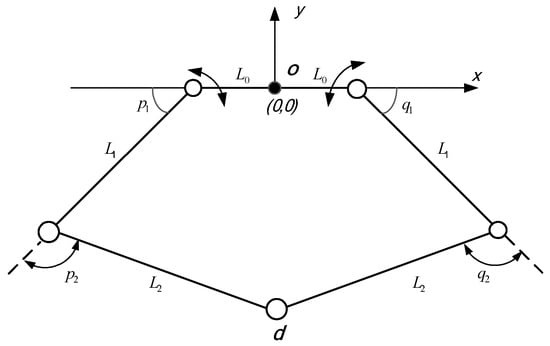

This study aimed to develop closed symmetric planar robotic arms driven by two pairs of opposing PMAs as shown in Figure 2. The robotic structure is configured in analogy to human arms, where two terminal linkages are mechanically coupled to form a unified end-effector. The end-effector’s desired position is regulated through the coordinated actuation of the shoulder joint angles. When two pairs of PMAs are attached to the upper arms, each shoulder is actuated and this could assist in arms movement. Therefore, the control errors of each joint are not accumulated and the system remains robust even when the arms operate at high speed with the end-effector carrying a payload, and the forearms carry no actuator-borne load. In the control system, the FSB-ASMC + tracking performance is first used to design the PMAs path tracking controller. Finally, the novel closed symmetrical robotic arms system driven by PMAs is implemented and verified experimentally.

Figure 2.

The structure of closed symmetrical planar robotic arms driven by two pairs of opposing PMAs.

2. Test Rig Layout

The schematic model of closed symmetrical planar robotic arms is driven by four PMAs with a dual three-rotational shoulder joint mechanism. A photograph is shown in Figure 3. The mechanism is designed with three respective rotational joints: the two side joints link the opposing PMAs and the middle joint links the upper arms. When the differential pressure passes through the contraction and extension of opposing PMAs, the rotational torque can be generated and then drive the three joints to rotate. Thus, the shoulder angle and the end-effector position of robot arms are changed at the same time. Therefore, we can calculate the angular motion for tracking control by using the inverse kinematics.

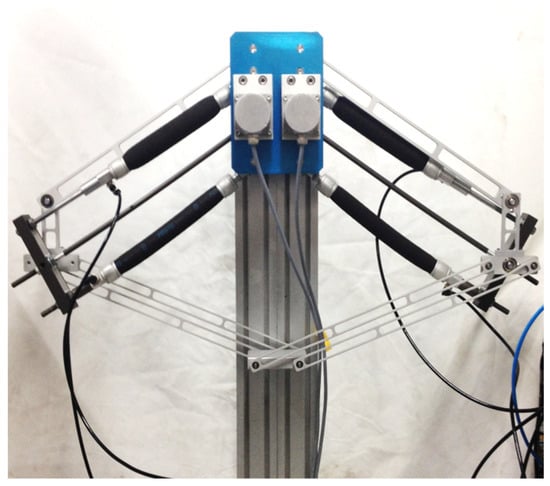

Figure 3.

Photograph of the test rig.

The pneumatic servo PMAs contain a pneumatic source, four PMAs, and four proportional servo valves. The PMAs have 20 mm of rubber tube diameter and 250 mm of length in two upper arms. The proportional servo valve is made by Festo with model MPPES-3-1/for four PMAs. The air pressure is set as 6 bar.

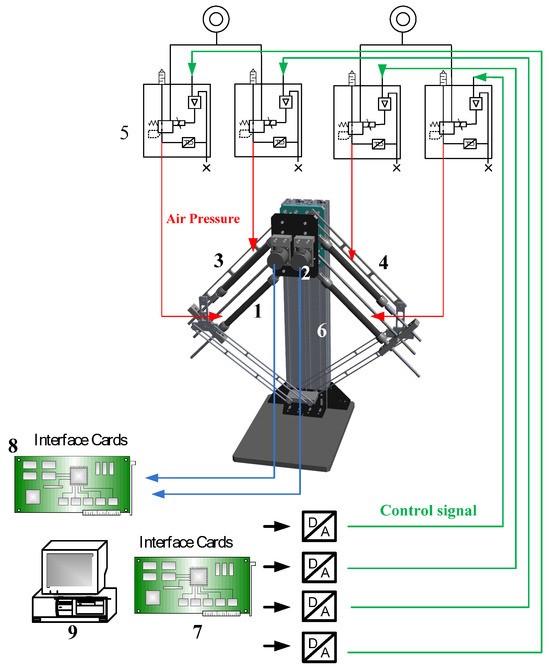

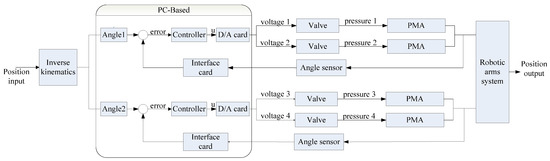

Table 1 shows the specifications of the test rig. The experimental procedure of the PMAs system is described and shown in Figure 4. The PC-based control unit contains the experimental software developed and compiled in Dev-C++ 5.0(4.9.9.2): two angular sensors, an AD/DA interface card, and an encoder card. The control signal computed by the PC-based control unit drives the proportional pressure servo valve via an AD/DA interface card with a sampling time of 1 ms and then actuates the PMAs. Thus, the end-effector can move in a two-dimensional motion via arms driven by the four PMAs. In addition, the two angular sensors with a resolution of 0.018-degrees are required for measuring the shoulder angle of each arm. The measuring signals of the angular sensors are fed back to the PC-based control unit via an encoder card. The control algorithm discussed in Section 3.3. is calculated to control the end position of the robot arms’ end-effector to achieve the path tracking control by controlling the angle of both right and left robot arms.

Table 1.

Specifications of the test rig.

Figure 4.

Layout of the servo dual-axial PMAs robot system. 1. Pneumatic muscle; 2. Angular sensor; 3. Left arm; 4. Right arm; 5. Proportional servo valve; 6. Base; 7. PCL-726; 8. PCL-833; 9. PC-based controller.

3. System Mechanism Analysis

3.1. Forward Kinematic Analysis

Figure 5 shows the simplified structure diagram of a dual-axial PMAs robot system, where L0 is 75 mm, L1 is 400 mm, and L2 is 500 mm.

Figure 5.

Geometrical model of robotic arms.

Since the left and right arms have a collective terminal point, the position of the end-effector can be written as

For the geometric model obtain .

Therefore, when q1 and p1 are known, the position can be solved:

where , , , .

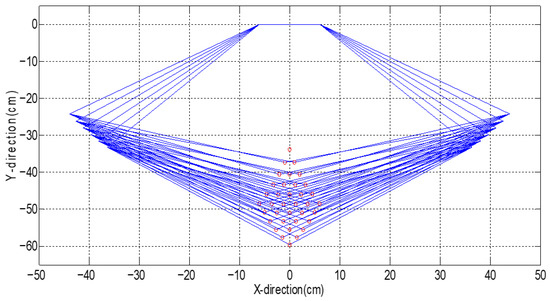

The simulated analysis of the available motion range of the robot arm is calculated by forward kinematics and simulated by MATLAB (v2020) performance, where the starting shoulder angle is 32.5-degrees and each downward rotation range is 15-degrees, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Available motion range for robotic arms, where red circle is the position of end effector.

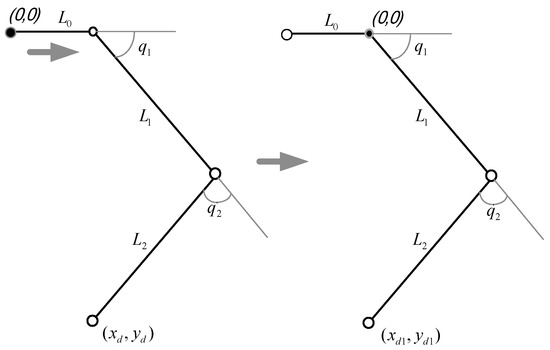

3.2. Inverse Kinematic Analysis

Figure 7 shows the simplified structural diagram of the dual-axial PMAs robotic system used for inverse kinematics. In the inverse kinematic formulation, the coordinate origin is translated to the right-hand reference point in order to facilitate the computation of joint angles and end-effector position.

Figure 7.

Inverse kinematics analysis of robot arm.

Then the position of and can be expressed as

Take the square of Equation (3) and add them to each other:

Then we can obtain

Solve Equation (4), and q2 can be calculated:

If the spatial trajectory (, ) of the desired end-effector is given, according to the inverse kinematics of two-DOF arms, the requirements of the spatial path are equivalent to the joint trajectory:

3.3. Control Strategy

In order to develop the path controller for the four pneumatic servo actuators, a Fourier series-based adaptive sliding mode controller with tracking performance (FSB-ASMC + ) [28] is used in this study to solve the high nonlinearity and time-varying problems. The FSB-ASMC + controller includes the Fourier series-based adaptive sliding mode controller and tracking performance design technique. The Fourier series-based adaptive sliding mode controller can handle the high nonlinear and time-varying problems.

A general nonlinear system is shown as

where y(t) is the output of the system, and are unknown time-varying functions, and u(t) is the control input of the system. The functional approximation technique to approximate the functions and , and Equation (8) can be rewritten as

where and are approximations of the uncertain time-varying functions and ; and are the truncation errors of the approximations of and . Define the output error as

where is a given bounded reference signal. The sliding surface is described as

where are chosen such that is a Hurwitz polynomial.

Then

Let , and the error dynamics will become

Assume that the Dirichlet conditions are satisfied, and the control input u can be chosen as

In addition, the tracking performance design technique is proposed to reduce the chattering effect affected by sliding control. Therefore, the control input is chosen as

where and are the estimations of and ; denotes elements of P satisfying the Lyapunov matrix equation , and is the design constant for attenuation level [29].

Given that the adaptive laws are chosen as

where and ( and ) are the adaptation gain matrix, the following result holds for s and e: as .

The Lyapunov function is defined as:

where

Differentiate Equation (14), and we can obtain

By substituting Equations (13) and (14) into Equation (16) and choosing , , we can obtain

From Barbarlet’s lemma, we can prove that when , and .

3.4. Controller Design

In this study, the control input is chosen as:

where and is position error. The initial values of Fourier coefficients and are and ; and . The controller parameters are shown in Table 2. Furthermore, Figure 8 shows the control block diagram of the dual-axial PMAs robotic arms system.

Table 2.

Controller parameters of the robotic arms system for path tracking control.

Figure 8.

Control block diagram of the dual-axial PMAs robotic arms system.

4. Experiments

To ensure the feasibility of the mechanism design and the controller of the novel dual-axial PMAs robotic arms system, the experiments for different kinds of path tracking control were implemented. In addition, the end-effector specific path tracking control was also performed.

In order to avoid the loss of sensor signal (due to high-speed moving of the system), the path tracking control is used instead of the step response. Thus, the transient and steady-state responses can be considered. For that, the path profile of 5th order polynomial is designed as [32]:

where

, and are the position, velocity, and acceleration when ;

, and are the position, velocity, and acceleration when .

4.1. Experiment for Single-Axial PMAs System with Path Tracking Control

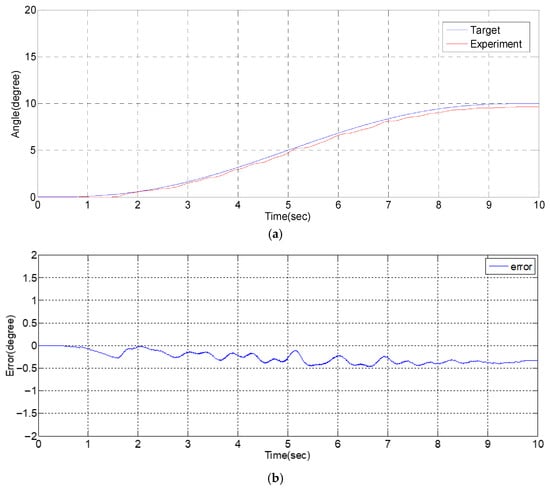

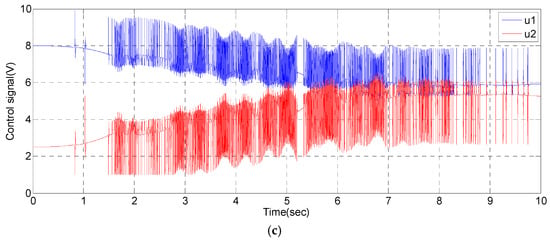

Due to the influence of gravity and the asymmetric nonlinearity in the PMAs system, an initial pressure is applied to the actuators at the beginning of operation. In the experimental setup, the driving signal is designed such that an input of 0–10 V corresponds linearly to a pressure range of 0–6 bar. Accordingly, an initial voltage of 8 V (equivalent to 4.8 bar) is applied to the upper PMAs, while 3 V (equivalent to 1.8 bar) is applied to the lower PMAs. Then, the control signals are given to the PMAs, such as (8 − u) V to the upper PMAs (voltage 1) and (3 + u) V to the lower PMAs (voltage 2). Therefore, the 5th order path tracking control with two different angular strokes, 10-degrees in 10 s and 1-degree in 15 s, is shown in Figure 9 and Figure 10, respectively. The experimental results show that the average tracking error can be controlled within 0.25-degrees and the ratio of error is 5%.

Figure 9.

Experimental results of 5th order angular path tracking control for a single-axial PMAs robotic system with stroke of 10-degrees in 10 s: (a) angular path response; (b) angular tracking error; (c) control signal.

Figure 10.

Experimental result of 5th order angular path tracking control for a single-axial PMAs robotic system with stroke of 15-degrees in 15 s: (a) angular path response; (b) angular tracking error; (c) control signal.

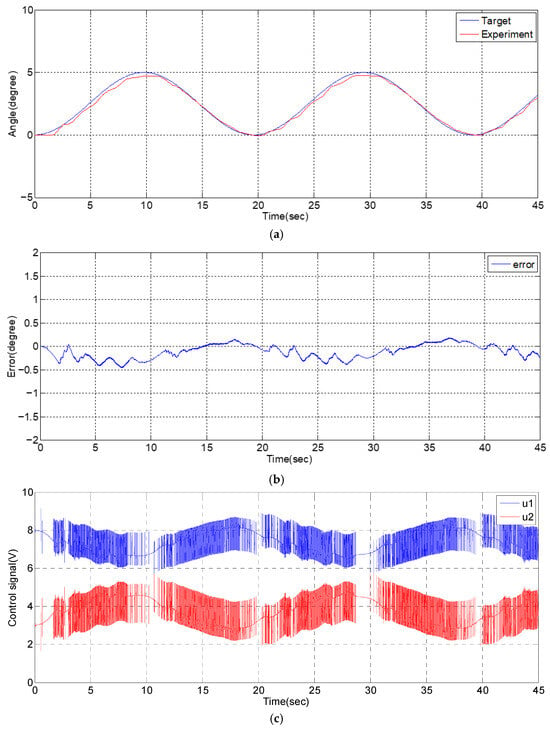

4.2. Experiment for Single-Axial PMAs System with Sinusoidal Path Tracking Control

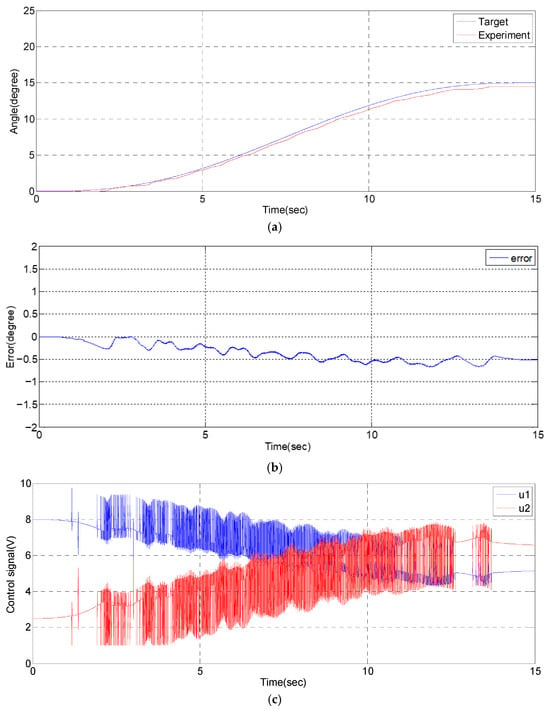

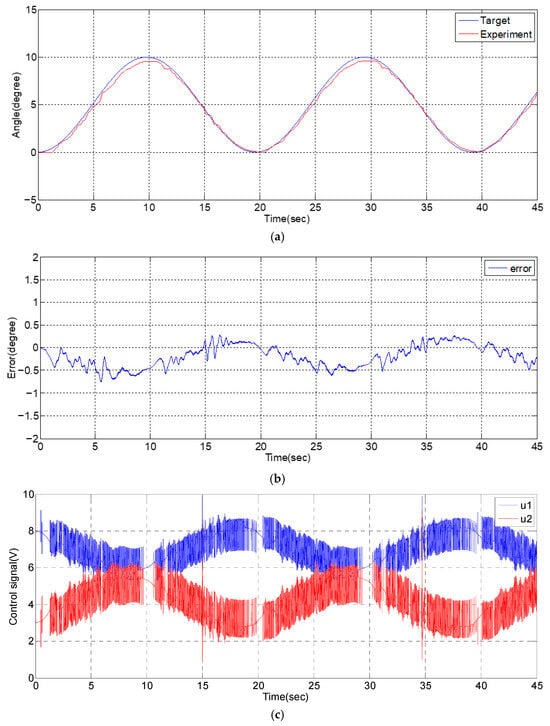

For sinusoidal path tracking control, the path with a frequency of 0.05 Hz and amplitudes of 10-degrees and 5-degrees are considered. The experimental results are shown in Figure 11 and Figure 12, where the average tracking error can be controlled within about 0.3-degrees and the ratio of error is 3%.

Figure 11.

Experimental results of angular path tracking control for a single-axial PMAs robotic system with a sinusoid trajectory of 10-degrees amplitude and 0.05 Hz: (a) angular path response; (b) angular tracking error; (c) control signal.

Figure 12.

Experimental results of angular path tracking control for a single-axial PMAs robotic system with a sinusoid trajectory of 5-degrees amplitude and 0.05 Hz: (a) angular path response; (b) angular tracking error; (c) control signal.

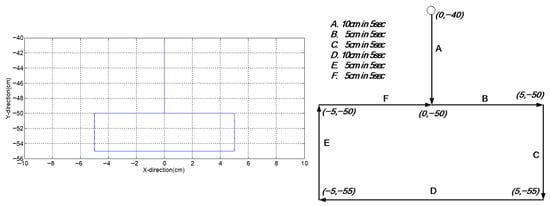

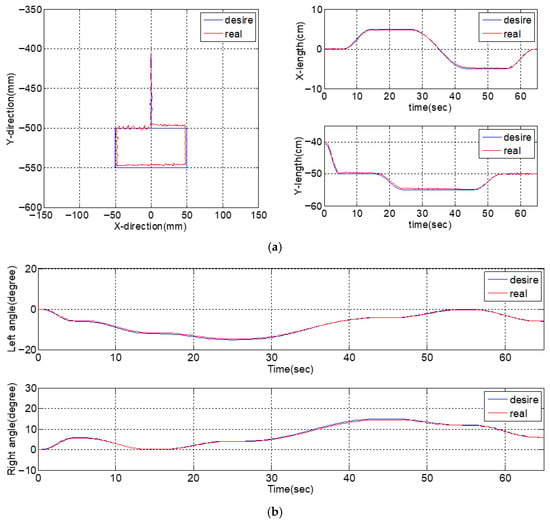

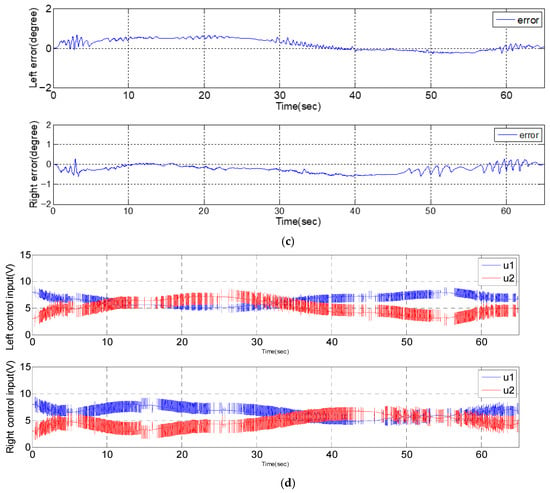

4.3. Experiment for Dual-Axial PMAs System with Specific Path Tracking Control

According to the previous experimental results and considering the limit of the system, the specific path for the end-effector of the robotic arms is designed for tracking control. We derived an equation by the inverse kinematics from Section 3, and the tracking shoulder angles of both right and left side arms are obtained.

The experimental setup is illustrated in Figure 13. The end-effector is initially positioned above and outside the rectangular trajectory, corresponding to a shoulder joint angle of 32.5° at the highest configuration. From this initial position, the end-effector first moves downward along a straight vertical path, then turns right to follow the rectangular trajectory defined by the sequence of points A, B, C, D, E, and F. The experimental results, shown in Figure 14, indicate that the average tracking error can be maintained within approximately 0.25-degrees, and thereby verifying the system’s effective trajectory tracking performance.

Figure 13.

The designed tracking path of the end-effector of the robotic arms.

Figure 14.

Experimental results of the dual-axial PMAs robotic system with end-effector trajectory of a specific path: (a) end-effector path tracking performance; (b) angular response of right and left arms; (c) angular error of right and left arms; (d) control signals of right and left arms.

5. Conclusions

In this study, a closed symmetrical robotic arm system driven by pneumatic muscle actuators (PMAs), referred to as the dual-axial PMA robotic system, was proposed and experimentally verified. The mechanism consists of closed symmetrical planar robotic arms actuated by two pairs of opposing PMAs. The distal links are mechanically coupled to form a collective end-effector, whose desired position is governed solely by the angular motion of the two shoulder joints. However, the nonlinear behavior, high hysteresis, low damping, and time varying in PMA could still limit its controllability. For that, the Fourier series-based adaptive sliding mode controller with (FSB-ASMC + ) was used to control the path tracking of the PMAs. The control strategy can not only effectively prevent approximation errors, disturbances, and un-modeled dynamics but also ensure the required positioning performance of the whole system. In order to implement the experimental verification, a full-scale test rig of the dual-axial PMAs robot system with a novel closed symmetrical planar robotic arm driven by PMAs was set up. Therefore, the experimental results showed that the control strategy for the system collocating the FSB-ASMC + can achieve good control performance in 5th order path and sinusoid path tracking of a single-axial PMAs robot system and the end-effector trajectory control of a specific path in a dual-axial PMAs robotic system.

In addition, the study analyzed the mechanism, resolved the kinematics problem of the robotic arms, and overcame the high-nonlinearity and hysteresis problems of the PMAs system. The experimental results showed that the system can achieve satisfactory and feasible control performance, including that the path tracking ratio of error is 5% in 15-degrees stroke, the sinusoidal path tracking ratio of error is 3% in a frequency of 0.05 Hz and amplitude of 10-degrees, and the coordinate motion trajectory tracking error can be controlled within about 0.25-degrees.

Author Contributions

M.-H.C. conceived and designed the experiments; C.-W.C. performed the experiments and analyzed the data; M.-H.C. and C.-W.C. wrote the paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was sponsored in part by the National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan under grant MOST 109-2221-E-002-111.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PMA | Pneumatic muscle actuator |

| FSB-ASMC + | Fourier series-based adaptive sliding mode controller with |

References

- Lilly, J.H. Adaptive tracking for pneumatic muscle actuators in bicep and tricep configurations. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2003, 11, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, H.; Suzuki, H. Development of a new shoulder mechanism for a muscle suit. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Mechatronics and Automation, Niagara Falls, ON, Canada, 29 July–1 August 2005; Volume 2, pp. 1051–1056. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, T.-C.; Chiang, M.-H. Design and control of a 1-DOF robotic lower-limb system driven by novel single pneumatic artificial muscle. Appl. Sci. 2019, 10, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, T.-C.; Chiang, M.-H. A lower limb rehabilitation assistance training robot system driven by an innovative pneumatic artificial muscle system. Soft Robot. 2023, 10, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, C.P.; Hannaford, B. Measurement and modeling of Mckibben pneumatic artificial muscles. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 22–28 April 1996; Volume 12, pp. 90–102. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, D.B.; Repperger, D.W.; Phillips, C.A.; Bandry, G. Modeling the dynamic characterisitcs of pneumatic muscle. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2003, 31, 310–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, S.; Tsagarakis, N.; Canderle, J.; Caldwell, D.G. Enhanced modelling and performance in braided pneumatic muscle actuators. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2003, 22, 213–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saga, N.; Nakamura, T.; Yaegashi, K. Mathematical model of pneumatic artificial muscle reinforced by straight fibers. J. Intell. Mater. Syst. Struct. 2007, 18, 175–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medrano-Cerda, G.A.; Bowler, C.J.; Caldwell, D.G. Adaptive position control of antagonistic pneumatic muscle actuators. Intell. Robot. Syst. 1995, 1, 378–383. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell, D.G.; Medrano-Cerda, G.A.; Goodwin, M. Control of pneumatic muscle actuators. IEEE Control Syst. Mag. 1995, 15, 40–48. [Google Scholar]

- Ahn, K.K.; Thanh, T.D.C.; Ahn, Y.K. Intelligent switching control of pneumatic artificial muscle manipulator. JSME Int. J. Ser. C 2005, 48, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tondu, B.; Lopez, Y. Modeling and control of Mckibben artificial muscle robot actuators. IEEE Control Syst. Mag. 2005, 20, 15–38. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, S.; Han, Z. Energy- efficient control of pneumatic muscle actuated biped robot joints. In Proceedings of the 6th World Congress on Intelligent Control and Automatic, Dalian, China, 21–23 June 2006; Volume 2, pp. 8881–8885. [Google Scholar]

- Jutras, D.; Bigras, P. Control of an actuator made of two antagonist Mckibben muscles via LMI optimization. IEEE Int. Symp. Ind. Electron. 2006, 4, 3072–3077. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, M.K.; Yen, P.L.; Yuan, T.H. Angle control of a one-dimension pneumatic muscle arm using self-organizing fuzzy control. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man and Cybernetics, Taipei, Taiwan, 8–11 October 2006; Volume 5, pp. 3834–3838. [Google Scholar]

- Lilly, J.H.; Quesada, P.M. A two-input sliding-mode controller for a planar arm actuated by four pneumatic muscle groups. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2004, 12, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullinan, M.F.; Bourke, E.; Kelly, K.; McGinn, C. A McKibben type sleeve pneumatic muscle and integrated mechanism for improved stroke length. J. Mech. Robot. 2017, 9, 011013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalita, B.; Leonessa, A.; Dwivedy, S.K. A Review on the Development of Pneumatic Artificial Muscle Actuators: Force Model and Application. Actuators 2022, 11, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.K. An adaptive self-organizing fuzzy sliding mode controller for a 2-DOF rehabilitation robot actuated by pneumatic muscle actuators. Control Eng. Pract. 2010, 18, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anh, H.P.H. Online tuning gain scheduling MIMO neural PID control of the 2-axes pneumatic artificial muscle (PAM) robot arm. Expert Syst. Appl. 2010, 37, 6547–6560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahanabadi, H.; Mailah, M.; Md-Zain, M.Z.; Hooi, H.M. Active force with fuzzy logic control of a two-link arm driven by pneumatic artificial muscles. J. Bionic Eng. 2011, 8, 474–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, T.; Higashi, T.; Shimizu, K. Teleoperation of a Robot Arm System Using Pneumatic Artificial Rubber Muscles: Teleoperation over the Internet Using UDP and a Web Camera. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Broadband, Wireless Computing, Communication and Applications, Fukuoka, Japan, 4–6 November 2010; pp. 714–718. [Google Scholar]

- Muramatsu, Y.; Kobayashi, H.; Sato, Y.; Jiaou, H.; Hashimoto, T.; Kobayashi, H. Quantitative performance analysis of muscle suit—Estimation by Oxyhemoglobin and deoxyhemoglobin. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Biomimetics, Karon Beach, Thailand, 7–11 December 2011; pp. 293–298. [Google Scholar]

- Utkin, V.I. Survey Paper Variable Structure Systems with Sliding Modes. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 1977, 22, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, J.Y.; Gao, W.; Hung, J.C. Variable structure control: A survey. Industrial Electronics. IEEE Trans. Mechatron. 1993, 40, 2–22. [Google Scholar]

- Slotine, J.J.E. Sliding controller design for non-linear systems. Int. J. Control 1984, 40, 421–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.C.; Huang, A.C. Adaptive Sliding Control of Active Suspension Systems with Uncertain Hydraulic Actuator Dynamics. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 2006, 44, 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, A.C.; Kuo, Y.S. Sliding control of nonlinear systems containing time-varying uncertainties with unknown bounds. Int. J. Control 1999, 74, 252–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, Y.C.; Huang, A.C. Multiple-Surface Sliding Controller Design for Pneumatic Servo Systems. Mechatronics 2007, 18, 506–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, M.H.; Lee, L.W.; Kuo, C.F.; Chen, Y.N. A H∞ Tracking-Based Adaptive Sliding-Mode Controller for Nonlinear Pneumatic Path Tracking Systems via a Functional Approximation Approach. J. Chin. Soc. Mech. Eng. 2009, 24, 507–515. [Google Scholar]

- Chiang, M.H.; Lin, H.T. Development of a 3D Parallel Mechanism Robot Arm with Three Vertical-Axial Pneumatic Actuators, Large Stroke and Nanometer Accuracy. Sensors 2011, 11, 11476–11494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, J.J. Introduction to Robotics Mechanics and Control; Addison-Wesley Publishing Company: Boston, MA, USA, 1989; pp. 237–238. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).