Abstract

Infective endocarditis classically involves non-sterile vegetations on valvular surfaces in the heart. Feared complications include embolization and acute heart failure. Surgical intervention achieves source control and alleviates valvular regurgitation in complicated cases. Vegetations >1 cm are often intervened upon, making massive vegetations uncommon in modern practice. We report the case of a 39-year-old female with history of intravenous drug abuse who presented with a serpiginous vegetation on the native tricuspid valve and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. The vegetation grew to 5.6 cm by hospital day two, and she successfully underwent a tricuspid valvectomy. Six weeks of intravenous vancomycin therapy were completed without adverse events. To better characterize other dramatic presentations of infective endocarditis, we performed a systematic literature review and summarized all case reports involving ≥4 cm vegetations.

1. Introduction

Infective endocarditis classically involves non-sterile vegetations on valvular surfaces in the heart [1]. Feared complications include embolization, uncontrolled sepsis, destruction of valvular tissue, and acute decompensated heart failure [1]. Current recommendations [2,3,4,5] endorse surgical intervention when certain criteria are satisfied and vegetations exceed 1 cm in length.

We report the case of a 39-year-old female with history of intravenous drug abuse (IVDA) who presented with a serpiginous vegetation on the native tricuspid valve and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) bacteremia. The vegetation grew to 5.6 cm, and she underwent a tricuspid valvectomy. Six weeks of intravenous (IV) vancomycin were completed without adverse events. We performed a systematic literature review and summarized all case reports involving ≥4 cm vegetations.

2. Case Presentation

A 39-year-old female with a history of IVDA and untreated hepatitis C presented to the emergency department with a two-week history of malaise, arthralgias, and myalgias accompanied by a non-productive cough. In the preceding years, she had multiple admissions for MRSA soft tissue abscesses, MRSA septic arthritis, MRSA pneumonia, and one episode of MRSA bacteremia. In the emergency department, she was febrile (40 °C, rectal) and tachycardic. No peripheral stigmata of endocarditis were noted on physical exam. Blood cultures were obtained before empiric IV vancomycin and piperacillin-tazobactam were started.

On admission, laboratory investigations were notable for hyponatremia (126 mmol/L; ref. range 136–144 mmol/L) and an absence of leukocytosis (9900/μL; ref. range 4000–10,000/μL). Transthoracic echocardiography revealed tricuspid regurgitation and a large, serpiginous vegetation on the septal leaflet of the tricuspid valve. Additionally, a chest radiograph demonstrated patchy opacities in multiple lobes, which were concerning for septic emboli.

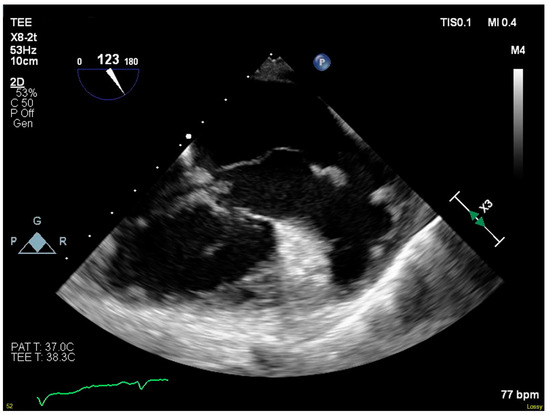

Blood cultures grew MRSA the following day, and antimicrobial therapy was narrowed to IV vancomycin. A transesophageal echocardiogram showed progression to severe tricuspid regurgitation with all three leaflets affected by destructive vegetations. The vegetation on the septal leaflet had grown to 5.6 cm and extended into the right atrium (Figure 1). She was transferred to our institution’s primary hospital for surgical management.

Figure 1.

Serpiginous vegetation on septal leaflet of tricuspid valve.

On hospital day three, she underwent tricuspid valvectomy. A median sternotomy was performed. Ascending aorta and bicaval cannulation were carried out for cardiopulmonary bypass. The right atrium was opened through an oblique atriotomy. Extensive destruction of the tricuspid valve was noted intraoperatively, and all leaflets were excised and debrided down to the tips of the papillary muscles. The annulus was also debrided. Cardiopulmonary bypass was weaned without complication. Stainless-steel wires were used to close the sternum, with absorbable sutures for skin and subcutaneous tissues. Debrided tissue was submitted for culture and subsequently grew MRSA.

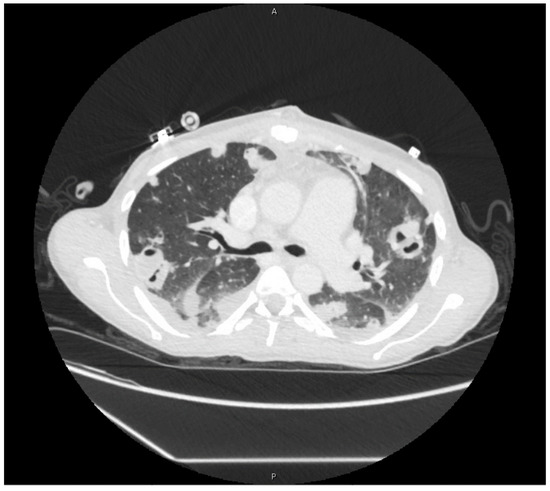

Postoperatively, she required vasopressor support and remained intubated. Her leukocytosis (19,000/μL) peaked on hospital day four, so IV piperacillin-tazobactam was restarted. Blood cultures taken the same day returned positive for MRSA. By hospital day six, she was extubated and weaned from vasopressor support. Antimicrobial therapy was again narrowed to IV vancomycin. Blood cultures taken on hospital day seven returned negative, and a treatment plan to receive six-weeks of IV vancomycin starting from this date was made. Imaging studies in the following days demonstrated cavitary lesions in both lungs (Figure 2) and possible C4–C5 vertebral discitis and osteomyelitis; however, no further surgical interventions were required. She was discharged on hospital day 18.

Figure 2.

Cavitary lesions on computed-tomography scan of chest.

As an outpatient, she was seen 28 days after discharge and had been tolerating vancomycin. She reported resolution of her constitutional symptoms, yet she continued to experience diffuse arthralgias and joint swelling. Her six-week course of vancomycin was completed five days later, and she went on to be diagnosed with seronegative rheumatoid arthritis in the coming months.

The review of medical records was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Yale University (2000028148), and need for informed consent was waived.

3. Discussion

Our case concerned a 39-year-old female with a history of IVDA who presented with infective endocarditis and MRSA bacteremia. A 5.6 cm serpiginous vegetation was visualized on her tricuspid valve, and she successfully underwent tricuspid valvectomy followed by vancomycin monotherapy for six weeks. Large vegetations are associated with higher morbidity and mortality [2,3,4,5], making our case’s successful outcome striking.

To identify all case reports of infective endocarditis in adults with vegetations ≥4 cm, we searched PubMed database using the following operators: [large OR largest OR big OR biggest OR massive OR longest OR enormous OR huge OR exceptional] AND [vegetation OR vegetations] AND [valve] AND [endocarditis]. Only case reports in the English language were included. Table 1 summarizes all reported cases and our case. The mean age was 46 years, and 52% were male. The mean vegetation length was 5.5 cm (range 4–10 cm), and 39% of cases involved native tricuspid valves. Gram-positive bacteria accounted for most cases (14 of 23), and fungal pathogens were identified in 5 of 23 cases. Surgical intervention occurred in 16 of 23 cases, with percutaneous catheter-based intervention used in one case [6]. Length of targeted antimicrobial therapy ranged from <1–10 weeks. Overall mortality was 43% (9 of 21).

Table 1.

Summary of infective endocarditis reports with ≥4 cm vegetations.

4. Conclusions

Our review of four decades of literature demonstrates that ≥4 cm vegetations are exceptional. Overall, advancements in echocardiography and surgical technique have made the diagnosis and management of infective endocarditis more standardized [1]. Nonetheless, massive vegetations are possible and benefit from a multidisciplinary approach to management.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.R. and M.G.; Data curation, J.O.-H; Writing—original draft preparation, C.R.; writing—review & editing, J.O.-H. and M.G.; Supervision, M.G. All authors have read and agree to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Chambers, H.F.; Bayer, A.S. Native-Valve Infective Endocarditis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettersson, G.B.; Coselli, J.S.; Hussain, S.T.; Griffin, B.; Blackstone, E.H.; Gordon, S.M.; Lemaire, S.A.; Woc-Colburn, L.E. 2016 The American Association for Thoracic Surgery (AATS) consensus guidelines: Surgical treatment of infective endocarditis: Executive summary. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2017, 153, 1241–1258.e29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baddour, L.M.; Wilson, W.R.; Bayer, A.S.; Fowler, V.G., Jr.; Tleyjeh, I.M.; Rybak, M.J.; Barsic, B.; Lockhart, P.B.; Gewitz, M.H.; Levison, M.E.; et al. Infective Endocarditis in Adults: Diagnosis, Antimicrobial Therapy, and Management of Complications. Circulation 2015, 132, 1435–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habib, G.; Lancellotti, P.; Antunes, M.J.; Bongiorni, M.G.; Casalta, J.P.; Del Zotti, F.; Dulgheru, R.; El Khoury, G.; Erba, P.A.; Iung, B.; et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of infective endocarditis: The Task Force for the Management of Infective Endocarditis of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Endorsed by: European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS), the European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM). Eur. Heart J. 2015, 36, 3075–3128. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nakatani, S.; Ohara, T.; Ashihara, K.; Izumi, C.; Iwanaga, S.; Eishi, K.; Okita, Y.; Daimon, M.; Kimura, T.; Toyoda, K.; et al. JCS 2017 Guideline on Prevention and Treatment of Infective Endocarditis. Circ. J. 2019, 83, 1767–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abubakar, H.; Rashed, A.; Subahi, A.; Yassin, A.S.; Shokr, M.; Elder, M. AngioVac System Used for Vegetation Debulking in a Patient with Tricuspid Valve Endocarditis: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Case Rep. Cardiol. 2017, 2017, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, R.; Gannon, B.R.; Childs, T.J.; Isotalo, P.A.; Abdollah, H. Aspergillus fumigatus pacemaker lead endocarditis: A case report and review of the literature. Can. J. Cardiol. 2006, 22, 337–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tanaka, M.; Abe, T.; Hosokawa, S.; Suenaga, Y.; Hikosaka, H. Tricuspid valve Candida endocarditis cured by valve-sparing debridement. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 1989, 48, 857–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nt, R.; Bray, N.; Wang, H.; Zelnick, K.; Osman, A.; Vicuña, R. Rare infection of implantable cardioverter-defibrillator lead withCandida albicans: Case report and literature review. Ther. Adv. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2014, 8, 193–201. [Google Scholar]

- Chopra, T.; Dhar, S.; Sobel, J.D.; Afonso, L.; Bhargava, A.; Kumar, S.; Chopra, A. Candida kefyr Endocarditis in a Patient with Hypertrophic Obstructive Cardiomyopathy. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2010, 339, 188–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, W.A.; Isner, J.M.; Bracey, A.W.; Roberts, W.C.; Garagusi, V.F. Disseminated petriellidium boydii and pacemaker endocarditis1. Am. J. Med. 1980, 69, 929–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyata, E.; Satoh, S.; Inokuchi, K.; Aso, A.; Kimura, Y.; Yokoyama, S.; Mori, E.; Nakamura, T.; Matsumoto, T.; Fujino, Y.; et al. Three fatal cases of rapidly progressive infective endocarditis caused by Staphylococcus aureus: One case with huge vegetation. Circ. J. 2007, 71, 1488–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machado, M.N.; Nakazone, M.A.; Takakura, I.T.; Silva, C.M.P.D.C.; Maia, L.N. Spontaneous Bacterial Pericarditis and Coronary Sinus Endocarditis Caused by Oxacillin-Susceptible Staphylococcus aureus. Case Rep. Med. 2010, 2010, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomaszuk-Kazberuk, A.; Sobkowicz, B.; Hirnle, T.; Lewczuk, A.; Sawicki, R.; Musiał, W. Giant right ventricular mural vegetation mimicking a cardiac tumour. Kardiol. Pol. 2011, 69, 587–589. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bernal, J.M.; Gonzalez, I.M.; Miralles, P.J. Prophylactic resection of a tricuspid valve vegetation in infective endocarditis. Int. J. Cardiol. 1986, 12, 255–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straumann, E.; Stulz, P.; Jenzer, H.R. Tricuspid Valve Endocarditis in the Drug Addict: A Reconstructive Approach (“Vegetectomy”). Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 1990, 38, 291–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scarvelis, D.; Malcolm, I. Embolization of a huge tricuspid valve bacterial vegetation. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2002, 15, 185–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birsic, G.W.; Fulcher, J.W.; Fiester, S.E. Embolization of Endocardial Vegetation with Stroke Presentation. Am. J. Forensic Med. Pathol. 2019, 40, 72–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwama, T.; Shigematsu, S.; Asami, K.; Kubo, I.; Kitazume, H.; Tanabe, S.; Matsunaga, Y. Tricuspid Valve Endocarditis with Large Vegetations in a Non-Drug Addict without Underlying Cardiac Disease. Intern. Med. 1996, 35, 203–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.-L.; Lin, W.-C.; Shih, P.-Y.; Huang, C.-H.; Hsu, Y.-C.; Yie, J.-C.; Chen, S.-Y.; Lin, C.-P. Streptococcus agalactiae infective endocarditis with large vegetation in a patient with underlying protein S deficiency. Infection 2012, 41, 247–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koushi, K.; Kitani, K.; Takahashi, A. A large vegetation at the tricuspid valve with gas image. Asian Cardiovasc. Thorac. Ann. 2014, 24, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montenegro-Sá, F.; Guardado, J.; Antunes, A.; Morais, J. A rare late finding in corrected tetralogy of Fallot: A case report. Eur. Heart J. Case Rep. 2018, 2, yty060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, P.K.; Miller, H.I.; Vidne, B.A. Mitral obstruction in bacterial endocarditis. Br. Heart J. 1985, 53, 341–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moorthy, K.; Prakash, R.; Aronow, W.S. Echocardiographic appearance of aortic valve vegetations in bacterial endocarditis due to actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. J. Clin. Ultrasound 1977, 5, 49–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamrah, V.S.; Williams, G.W.; Hughes, C.V.; Rose, H.D.; Tristani, F.E. Haemophilus parainfluenzae mitral valve vegetation without hemodynamic abnormality. Am. J. Med. 1979, 66, 543–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carruthers, M.M. Endocarditis due to enteric bacilli other than Salmonellae: Case reports and literature review. Am. J. Med. Sci. 1977, 273, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salsano, A.; Sportelli, E.; Borile, S.; Santini, F. Proteus mirabilis bioprosthetic tricuspid valve endocarditis with massive right ventricular vegetation: A new entity in the prosthetic valve endocarditis aetiology. Eur. J. Cardio Thorac. Surg. 2016, 50, 581–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).