Abstract

Arenaviruses include multiple human pathogens ranging from the low-risk lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) to highly virulent hemorrhagic fever (HF) causing viruses such as Lassa (LASV), Junin (JUNV), Machupo (MACV), Lujo (LUJV), Sabia (SABV), Guanarito (GTOV), and Chapare (CHPV), for which there are limited preventative and therapeutic measures. Why some arenaviruses can cause virulent human infections while others cannot, even though they are isolated from the same rodent hosts, is an enigma. Recent studies have revealed several potential pathogenic mechanisms of arenaviruses, including factors that increase viral replication capacity and suppress host innate immunity, which leads to high viremia and generalized immune suppression as the hallmarks of severe and lethal arenaviral HF diseases. This review summarizes current knowledge of the roles of each of the four viral proteins and some known cellular factors in the pathogenesis of arenaviral HF as well as of some human primary cell-culture and animal models that lend themselves to studying arenavirus-induced HF disease pathogenesis. Knowledge gained from these studies can be applied towards the development of novel therapeutics and vaccines against these deadly human pathogens.

1. Introduction

Arenaviruses are ambisense RNA viruses that are divided into Old World (OW) and New World (NW) virus groups based on their phylogenetic, serological, and geographical differences. While the prototypic OW arenavirus LCMV with worldwide distribution causes only mild illness in immunocompetent individuals, two other known OW arenaviruses (LASV and LUJV, both found in Africa) can cause severe hemorrhagic fever (HF) in humans. In addition, several of the NW arenaviruses in South America (e.g., JUNV, MACV, SABV, GTOV, and CHPV) can also cause severe hemorrhagic fevers (HF). There are currently limited preventative and therapeutic options for patients infected with these highly pathogenic viruses. Candid #1 is the only vaccine currently available against JUNV infection [1], but is only licensed for the endemic areas in Argentina. Ribavirin, a nucleoside analog, has been used for the treatment of arenavirus infections but has had mixed success and significant toxicity [2].

Besides the aforementioned pathogenic human arenaviruses, there are many other known and emerging arenaviruses that have no known causal roles in humans [3,4], including but not necessarily limited to a new group of snake-borne arenaviruses in the Reptarenavirus genus of the Arenaviridae family [5]. An important question is why some arenaviruses cause severe disease in humans, while others do not. Recent studies using viral reverse genetics, cell-based assays, animal models, and human genome-wide association analyses have revealed several potential mechanisms of arenaviral pathogenicity. We will summarize current understanding of the roles of the different viral and cellular factors that contribute to the degrees of arenavirus virulence in humans.

4. Molecular Mechanisms Contributing to Virus Virulence and HF Disease Pathogenesis

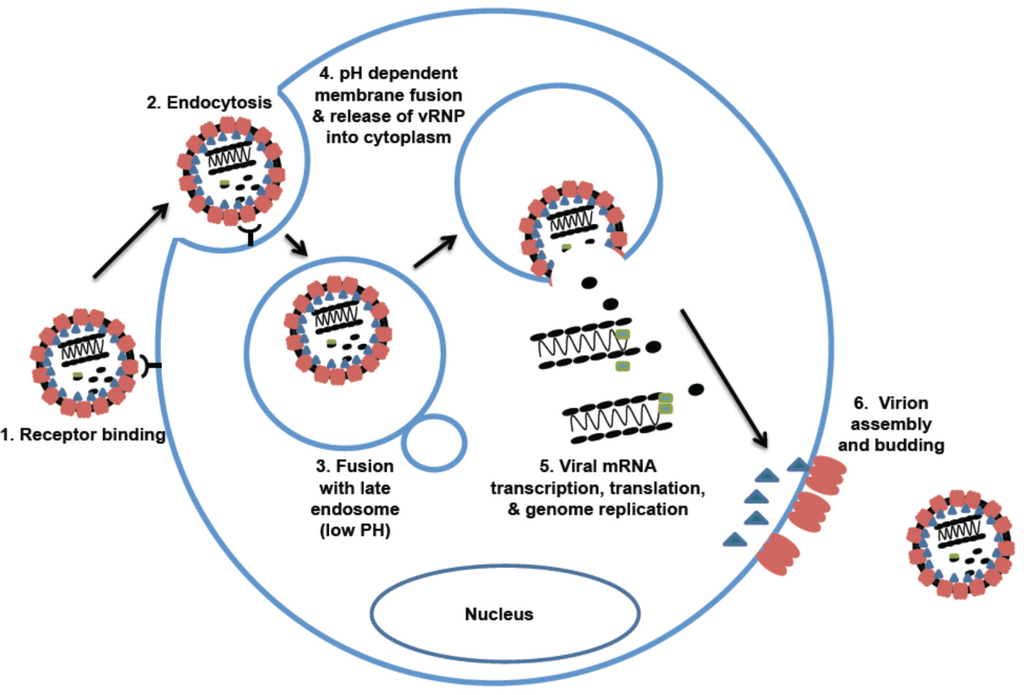

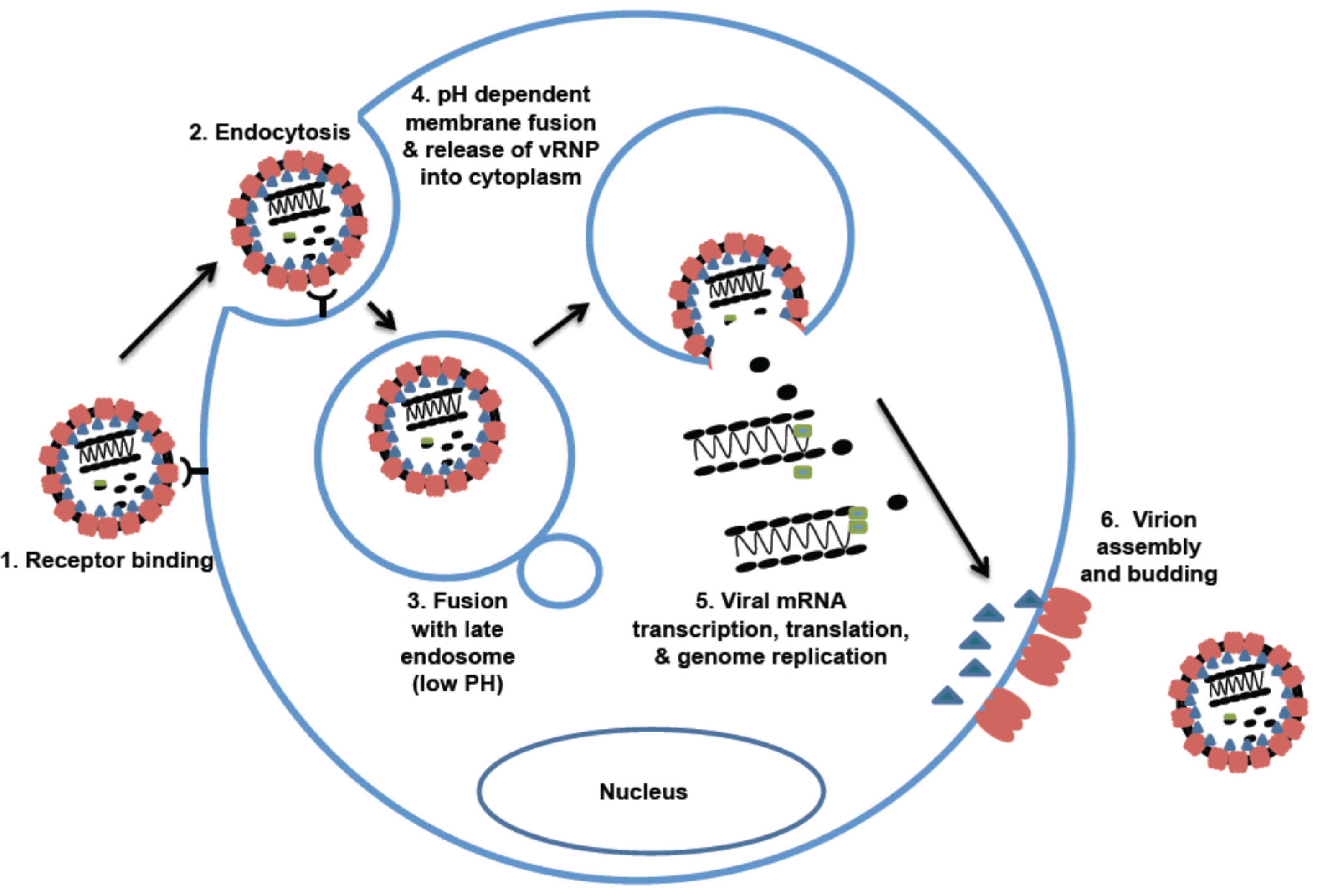

4.1. Roles of the Glycoprotein (GP) and of the Host Cell Receptors in HF Disease Susceptibility and Pathogenesis

The ability of a virus to bind to different cellular receptors via its glycoprotein makes GP an important pathogenic factor. OW and NW clade C arenaviruses use alpha-dystroglycan (αDG) as their receptor for cell entry. The differences in affinity of GP binding to αDG may contribute to differences in the disease outcome. Two strains of LCMV, clone 13 (Cl 13) and Armstrong (ARM), can induce different disease outcomes in mouse models. The Cl 13 strain causes chronic infection, whereas the ARM strain causes acute infection. Studies showed that LCMV with high affinity for αDG, such as the Cl 13 strain, is able to infiltrate the white pulp of the spleen and abolish the cytotoxic T lymphocytes, therefore inducing a persistent infection. During the infection of αDG low affinity strain, ARM strain, the viruses are mainly restricted in the red pulp and are quickly cleared by the strong cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) response [34,100].

A recent analysis of over 3 million human genomic polymorphisms by the International HapMap Project has suggested a natural positive selection in a Nigerian population for allele variants of several human genes, including LARGE, interleukin 21 (IL21), and dystrophin (DMD), which is a cytosolic adaptor protein that is required for the proper function of αDG [101,102]. A high proportion of individuals in this population (21%) have shown evidence of prior exposure to LASV, which may apply selective pressure on the allelic frequencies of these human genes, giving rise to their differential gene expressions, which would confer natural resistance to Lassa fever. These polymorphisms in LARGE and DMD, for example, may have hindered binding and entry of LASV, and thereby protected these individuals from severe LASV infection [101,102].

NW clade B arenaviruses include both pathogenic and non-pathogenic viruses. Among this group of viruses, JUNV, MACV, GTOV, SABV, and CHPV can cause severe and lethal HF in humans [17,18,21,25,103,104]. All five of these pathogenic NW clade B arenaviruses use human transferrin receptor 1 (hTfR1) as their receptor for cellular entry [3]. In contrast, the known NW clade B non-pathogenic viruses can only use the rodent version of TfR1 as their receptor. Likewise, the NW clade A/B viruses also use the host-species-specific TfR1 as their receptors [3]. Virion RNAs with sequence homology to the Whitewater Arroyo virus (WWAV), a clade A/B virus, have been detected in several human cases, suggesting that WWAV might be associated with human infections. While some studies have shown that this virus is unable to use hTfR1 as an entry receptor [105,106], WWAV-like viruses have been shown to potentially use hTfR1 as a receptor [3]. However, it is not clear whether usage of hTfR1 plays any role in disease pathogenesis, as WWAV has not directly been shown to be a causative HF agent.

Further evidence for the involvement of GPC as an important determinant of arenavirus virulence has been demonstrated in the guinea pig model for PICV infection [107]. Two strains of PICV (P2 and P18) can cause vastly different disease outcomes in infected animals [108,109]. Mutational analysis of the virulent (P18) and avirulent (P2) strains has revealed that sequence differences between the GPCs may contribute to the different disease outcomes. Substituting a single amino acid residue at position 140 of GPC from the avirulent P2 into the virulent P18 genome can increase the survival rate of infected animals from 0% to 33%, suggesting that GPC plays an important role in the disease outcomes [107]. A separate study has shown that mutational analysis at residue 427 of the GPC of the attenuated Candid #1 strain of JUNV is largely responsible for the attenuation of this vaccine strain in suckling mice [110]. That the residue change at this site results in increased virus-cell fusion at neutral pH of the Candid #1 strain and also in increased dependence on hTfR1 for entry demonstrates its role in contributing to virus attenuation in humans [111]. The study of the ML29 vaccine, a reassortant virus consisting of the LASV S genomic RNA segment and the Mopeia (MOPV) L genomic RNA segment, shows the attenuate phenotype of this reassortant virus in non-human primates and guinea pigs [112,113]. This data suggests that the major virulence factor(s) of LASV are located on the L segment. Other virus reassortant studies using LCMV or PICV have also implicated the contribution of the L genomic RNA segment in viral pathogenesis [114,115,116]. While the L polymerase gene, encoded on the L segment may play an important role, it is important to note that the L segment also encodes the Z protein with known roles in regulating RNA synthesis and host innate immunity that can participate in disease pathogenesis [77,80,117,118]. Interestingly, sequence analysis of the ML29 viruses isolated from infected animals reveals several important mutations on the S segment, especially within the GP coding sequence. The K272E mutation located between the SKI-1/S1P cleavage site and GP2 fusion domain is one such mutation [119]. It remains to be determined whether this and perhaps other mutations within the GP gene or elsewhere on the S segment of the ML29 vaccine virus contribute to the reduced pathogenic phenotype observed for this reassortant virus.

4.2. Role of the Polymerase (L) Protein in Viral Virulence

A hallmark of severe and lethal arenavirus-induced HF is the high level of viremia. It has been shown that individuals who can control the level of viremia are able to recover from the infection, while those who cannot typically succumb to the disease [120]. A single amino acid in the L polymerase (L1079) of the LCMV Cl13 has been shown to enhance the levels of intracellular viral replication, which can account for the difference of viral replication rates between the ARM and Cl 13 strains [121]. This residue has also been shown to be responsible for generalized immune suppression, which is likely a result of T cell exhaustion caused by the high viral loads, and therefore may be responsible for the difference in acute versus chronic infection by the ARM and Cl 13 strains. A separate study has shown that this same residue is responsible for enhanced viral replication and tropism in macrophages [122]. Using reverse genetics technology, we and other researchers have also demonstrated the role of the L polymerases of LASV and PICV in increasing viral replication and virulence in infected animals [123,124]. We show that the C terminal domain of L polymerase is the virulence determinant of the PICV P18 strain. In particular, three residues (N1906, N1889, and L1839) in the C terminal domain are associated with increased viral replication and pathogenesis in infected animals [124]. It is important to note that all naturally occurring residues found to enhance virus replication in LCMV, LASV, and PICV do not map to the known catalytic domains of the polymerase, and therefore their exact contributions to increased viral RNA synthesis and disease pathogenesis have yet to be determined.

4.3. Role of the Nucleoprotein (NP) in Innate Immune Suppression

Host immune responses to infection have a profound and direct influence on the disease course and outcomes. One of the hallmarks of severe and lethal arenavirus-induced HF is generalized immune suppression, the mechanisms of which are still under intense investigation. The nucleoproteins (NPs) of several arenaviruses have been shown to be capable of inhibiting the host innate immune responses. Specifically, the NPs of the OW arenaviruses LCMV and LASV and the NW arenaviruses JUNV, MACV, WWAV, PICV, TCRV, and LATV have been shown to inhibit the production of interferon-beta (IFNβ) [125,126].

Using X-ray crystallography and various functional assays, we and other researchers have demonstrated that the C terminus of the NPs of LASV, TCRV, and PICV contains a functional 3’–5’ exoribonuclease (RNase) domain that degrades dsRNA in vitro [74,126,127]. We have therefore proposed that NP inhibits type I IFNs by degrading viral pattern-associated molecular pattern (PAMP) molecules that would otherwise be recognized by cellular pattern recognition receptors (PRRs). The fact that the DEDDH catalytic residues are conserved among all known arenaviruses and that its function to suppress IFNβ production has been demonstrated for both pathogenic (e.g., LASV and LCMV) and non-pathogenic arenaviruses (e.g., TCRV and MOPV) suggests that this is a general mechanism of innate immune suppression by these viruses, allowing them to replicate in either their natural hosts (e.g., rodents) or in infected humans.

Amino acid substitutions of the conserved RNase catalytic residues (DEDDH) significantly reduce NP’s ability to inhibit IFNβ production in virus-infected cell cultures and in animals, directly implicating the exoribonuclease function in innate immune suppression [74,126] We have recently generated recombinant PICVs carrying individual NP RNase catalytic mutations (D380, E382, D457, D525, or H520) [128]. In vitro studies of these mutant PICVs show that these viruses induce high levels of IFNβ and grow poorly in the IFN competent A549 cells, but they can grow to similarly high titers as that of the wild-type PICV in IFN-defective Vero cells. All the RNase catalytic mutant viruses show an attenuated phenotype in infected guinea pigs, but show reversion to the wild-type NP sequence in isolates from moribund animals, providing strong genetic evidence for the important role of the NP RNase function in suppressing innate immunity and allowing the virus to replicate in the infected animals. This is consistent with another study in which a recombinant LASV carrying a double-point mutation of the NP RNase catalytic residues (D389 and G392) replicates to lower titers than the wild-type virus partly because it is unable to suppress type I IFNs [129]. The same group of investigators has also recently demonstrated that the LASV NP RNase domain is required to mount an effective antigen-presenting-cell-mediated response in NK cells against virus infection [130]. Other studies have suggested that when NP is overexpressed in cells, they can either prevent activation of the Nuclear Factor Kappa B (NFκB) or directly associate with RIG-I or IKKε in order to inhibit the phosphorylation of the IKKε or of the IFN-responsive gene (IRF3) and its translocation into the nucleus, and thereby negatively regulates type I IFN production [131,132,133]. Taken together, these data confirm the critical role of the arenaviral NP in mediating innate immune suppressive function, which would then allow the virus to replicate unchecked. While the generalized immunosuppression and high viremia are important factors in arenavirus-induced HF pathogenesis, it is important to note that many individuals infected with pathogenic arenaviruses (e.g., LASV) do recover from the infection as a result of a robust cell-mediated immunity [4,6].

4.4. Roles of the Z Protein in Innate Immune Suppression and Viral Pathogenicity

In addition to mediating viral budding and regulating viral RNA synthesis (see above), the Z protein also has immune suppressive function. A previous study has shown that the Z proteins of NW arenaviruses (JUNV, MACV, TCRV, and SABV), but not OW arenaviruses LASV and LCMV, can interact with the cytoplasmic pathogen-recognition-receptor RIG-I to inhibit the type I IFN induction [118]. We have recently conducted a comprehensive analysis of the Z proteins from many known arenaviruses and have found that the Z proteins of all nine known pathogenic arenaviruses, including LASV, LCMV, LUJV, JUNV, MACV, TCRV, SABV, and DANV, can effectively suppress the RIG-I-like receptor (RLR)-induced IFN responses [117]. This Z-mediated RLR inhibition is strongly associated with arenavirus pathogenicity, as only the Z proteins of all known pathogenic arenaviruses, but not any of the 14 non-pathogens, can inhibit human RLRs [117]. The inhibition is mediated by the interaction between the flexible N-terminal domain (NTD) of the pathogenic Z proteins and N-terminal tandem CARD domains of RIG-I/MDA5, thus disrupting the association of the RLRs and the mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein MAVS. Swapping of the 31-residue Z NTD from LCMV into a nonpathogenic PICV genome has led to the inhibition of type I IFN responses and increased viral replication in human macrophages—the early target cells of arenavirus infections. This study indicates that the pathogenic Z-mediated RLR inhibition by arenaviruses may be a common pathogenic mechanism underlying the diverse arenavirus family to cause diseases in humans. While each arenavirus pathogen may have its unique pathogenesis leading to variable disease symptoms in humans, all of them encode a Z protein that can inhibit the RLR signaling and thus, the induction of type-I IFNs.

6. Conclusions

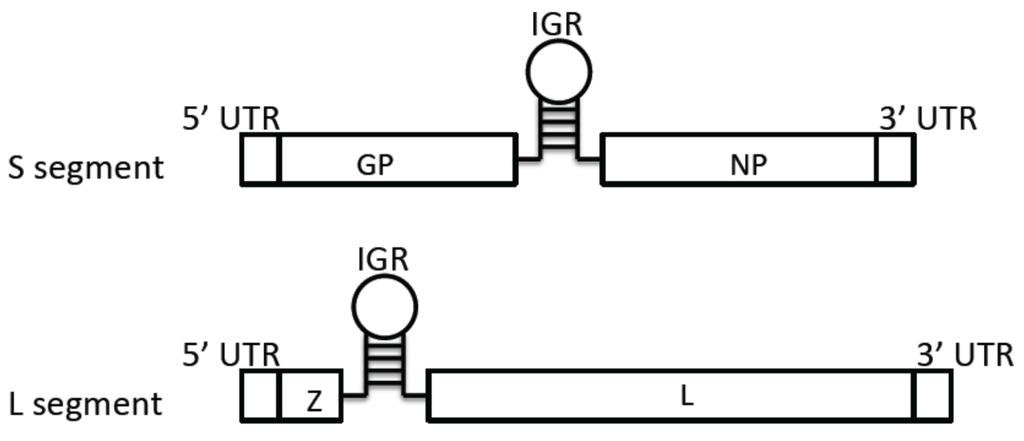

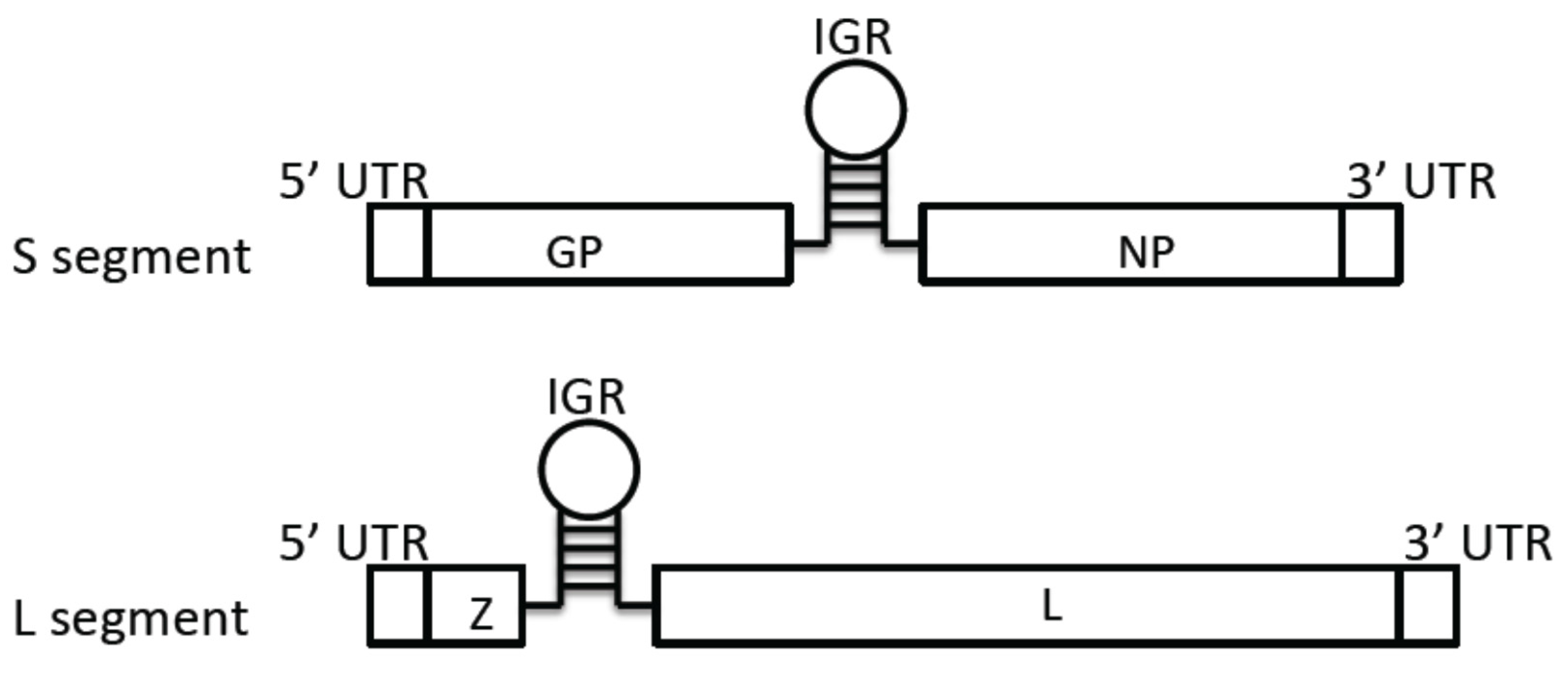

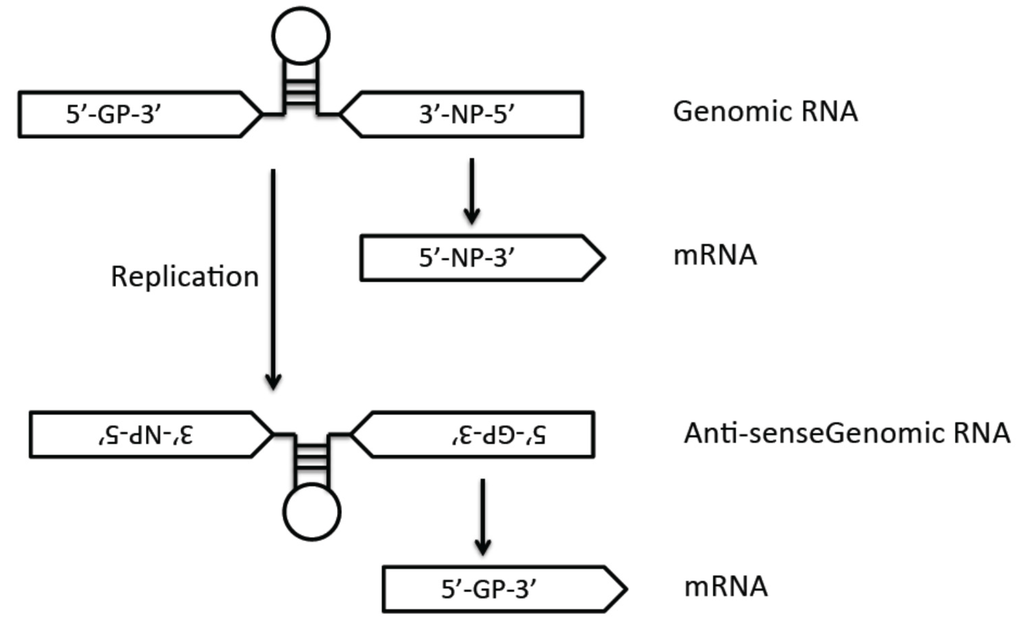

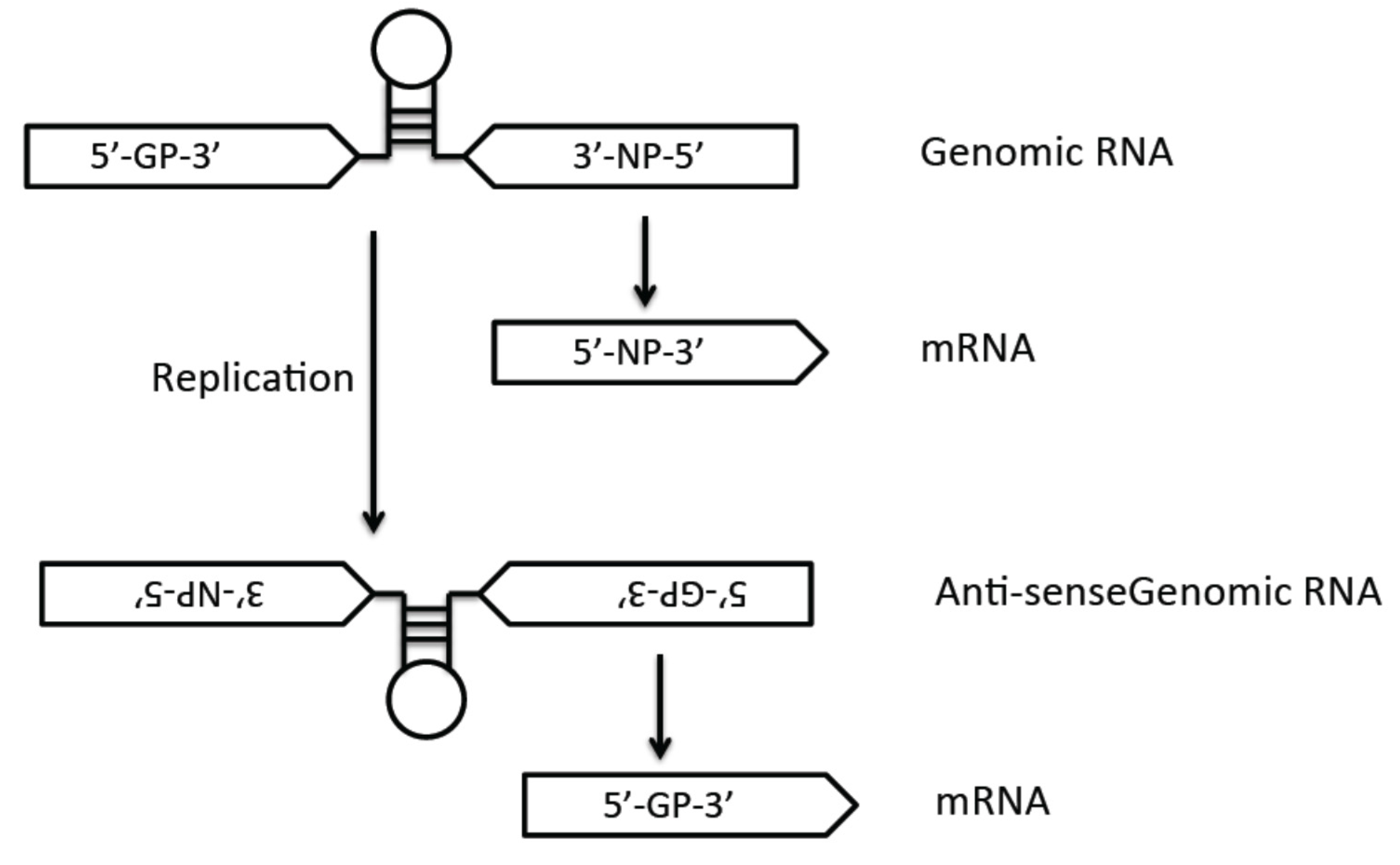

Arenaviruses are RNA viruses with a relatively simple genomic structure but with a complex biology and pathogenic mechanisms. The genome of the viruses encodes for only four genes, but each viral protein has multiple functions in mediating optimal viral replication and is possibly involved in the determination of different disease outcomes in humans. Studies have suggested that arenaviruses can gain virulence in hosts by increasing viral cell entry and replication capacity and by effectively suppressing host innate immune responses. The recent identification of the Z protein as a pathogenicity-associated factor has shed important insights into a common pathogenic mechanism underlying the diverse human arenavirus pathogens. Nevertheless, different human arenavirus pathogens exhibit unique features in basic viral replication mechanisms and disease manifestations [4], suggesting that further studies are warranted in order to understand the virus-specific pathogenic mechanisms for individual arenavirus pathogens. Important insights from recent studies on this group of important human pathogens can be exploited for the development of effective preventative and/or therapeutic modalities that can be tested in some established animal models of arenaviral HF.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH grants R01 AI083409 to Yuying Liang and R01 AI093580 and R56 AI091805 to Hinh Ly. The authors sincerely apologize to colleagues whose work might not have been cited in this article due to space constraint. The authors thank B. Meyer for his excellent and timely editorial assistance. The corresponding author (HL) would like to dedicate this article in loving memory to his mother.

Author Contributions

Hinh Ly conceived the idea for the article. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Maiztegui, J.I.; McKee, K.T.; Oro, J.G.B.; Harrison, L.H.; Gibbs, P.H.; Feuillade, M.R.; Enria, D.A.; Briggiler, A.M.; Levis, S.C.; Ambrosio, A.M.; et al. Protective efficacy of a live attenuated vaccine against Argentine hemorrhagic fever. J. Infect. Dis. 1998, 177, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Günther, S.; Lenz, O. Lassa virus. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2004, 41, 339–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zong, M.; Fofana, I.; Choe, H. Human and host species transferrin receptor 1 use by North American arenaviruses. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 9418–9428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLay, L.; Liang, Y.; Ly, H. Comparative analysis of disease pathogenesis and molecular mechanisms of New World and Old World arenavirus infections. J. Gen. Virol. 2014, 95, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radoshitzky, S.R.; Bao, Y.; Buchmeier, M.J.; Charrel, R.N.; Clawson, A.N.; Clegg, C.S.; DeRisi, J.L.; Emonet, S.; Gonzalez, J.P.; Kuhn, J.H.; et al. Past, present, and future of arenavirus taxonomy. Arch. Virol. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Moraz, M.-L.; Kunz, S. Pathogenesis of arenavirus hemorrhagic fevers. Expert Rev. Anti-infective Ther. 2010, 9, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, D.; McCormick, J.B.; Bennett, D.; Samba, J.A.; Farrar, B.; Machin, S.J.; Fisher-Hoch, S.P. Acute sensorineural deafness in Lassa fever. JAMA: J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1990, 264, 2093–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briese, T.; Paweska, J.T.; McMullan, L.K.; Hutchison, S.K.; Street, C.; Palacios, G.; Khristova, M.L.; Weyer, J.; Swanepoel, R.; Egholm, M.; et al. Genetic detection and characterization of Lujo virus, a new hemorrhagic fever–associated arenavirus from Southern Africa. PLoS Pathogens 2009, 5, e1000455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paweska, J.T.; Sewlall, N.H.; Ksiazek, T.G.; Blumberg, L.H.; Hale, M.J.; Lipkin, W.I.; Weyer, J.; Nichol, S.T.; Rollin, P.E.; McMullan, L.K.; et al. Nosocomial outbreak of novel arenavirus infection, Southern Africa. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2009, 15, 1598–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, C.J. Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus — an old enemy up to new tricks. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 354, 2208–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rousseau, M.C.; Saron, M.F.; Brouqui, P.; Bourgeade, A. Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus in Southern France: Four case reports and a review of the literature. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 1997, 13, 817–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, R.; Johnson, D.; Neumann, M.; Ksiazek, T.G.; Rollin, P.; Keech, R.V.; Bonthius, D.J.; Hitchon, P.; Grose, C.F.; Bell, W.E.; et al. Congenital lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus syndrome: A disease that mimics congenital toxoplasmosis or cytomegalovirus infection. Pediatrics 1997, 100, e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonthius, D.J. Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus: An underrecognized cause of neurologic disease in the fetus, child, and adult. Semin. Pediatr. Neurol. 2012, 19, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, S.A.; Graham, M.B.; Kuehnert, M.J.; Kotton, C.N.; Srinivasan, A.; Marty, F.M.; Comer, J.A.; Guarner, J.; Paddock, C.D.; DeMeo, D.L.; et al. Transmission of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus by organ transplantation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 354, 2235–2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacNeil, A.; Stroher, U.; Farnon, E.; Campbell, S.; Cannon, D.; Paddock, C.D.; Drew, C.P.; Kuehnert, M.; Knust, B.; Gruenenfelder, R.; et al. Solid organ transplant-associated lymphocytic choriomeningitis, United States, 2011. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2012, 18, 1256–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prevention, C.F.D.C.A. Brief report: Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus transmitted through solid organ transplantation - Massachussetts, 2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008, 57, 799–801. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Delgado, S.; Erickson, B.R.; Agudo, R.; Blair, P.J.; Vallejo, E.; Albariño, C.G.; Vargas, J.; Comer, J.A.; Rollin, P.E.; Ksiazek, T.G.; et al. Chapare virus, a newly discovered arenavirus isolated from a fatal hemorrhagic fever case in Bolivia. PLoS Pathogens 2008, 4, e1000047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lisieux, T.; Coimbra, M.; Nassar, E.S.; Burattini, M.N.; Souza, L.T.M.D.; Ferreira, I.B.; Rocco, I.M.; Rosa, A.P.A.T.D.; Vasconcelos, P.F.C.; Pinheiro, F.P.; et al. New arenavirus isolated in Brazil. Lancet 1994, 343, 391–392. [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar, P.V.; Camargo, W.; Vargas, J.; Guevara, C.; Roca, Y.; Felices, V.; Laguna-Torres, V.A.; Tesh, R.; Ksiazek, T.G.; Kochel, T.J. Reemergence of Bolivian hemorrhagic fever, 2007–2008. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2009, 15, 1526–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambrosio, A.; Saavedra, M.; Mariani, M.; Gamboa, G.; Maiza, A. Argentine hemorrhagic fever vaccines. Hum. Vaccines 2011, 7, 694–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charrel, R.N.; Lamballerie, X.D. Arenaviruses other than Lassa virus. Antivir. Res. 2003, 57, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enria, D.A.; Briggiler, A.M.; Sánchez, Z. Treatment of Argentine hemorrhagic fever. Antivir. Res. 2008, 78, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fulhorst, C.F.; Cajimat, M.N.B.; Milazzo, M.L.; Paredes, H.; de Manzione, N.M.C.; Salas, R.A.; Rollin, P.E.; Ksiazek, T.G. Genetic diversity between and within the arenavirus species indigenous to Western Venezuela. Virology 2008, 378, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, L.H.; Halsey, N.A.; McKee, K.T.; Peters, C.J.; Barrera Oro, J.G.; Briggiler, A.M.; Feuillade, M.R.; Maiztegui, J.I. Clinical case definitions for Argentine hemorrhagic fever. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1999, 28, 1091–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manzione, N.D.; Salas, R.A.; Paredes, H.; Godoy, O.; Rojas, L.; Araoz, F.; Fulhorst, C.F.; Ksiazek, T.G.; Mills, J.N.; Ellis, B.A.; et al. Venezuelan hemorrhagic fever: Clinical and epidemiological studies of 165 cases. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1998, 26, 308–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfau, C.J. Arenaviruses. In Medical Microbiology, 4th ed.; Baron, S., Ed.; The University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston: Galveston, TX, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, B.J.; de la Torre, J.C.; Southern, P.J. Arenaviruses: Genomic RNAs, transcription, and replication. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2002, 262, 139–157. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Knipe, D.M.H.; Peter, M. Fields Virology, 5th ed.; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, W.; Henry, M.D.; Borrow, P.; Yamada, H.; Elder, J.H.; Ravkov, E.V.; Nichol, S.T.; Compans, R.W.; Campbell, K.P.; Oldstone, M.B. Identification of alpha-dystroglycan as a receptor for lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus and Lassa fever virus. Science 1998, 282, 2079–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spiropoulou, C.F.; Kunz, S.; Rollin, P.E.; Campbell, K.P.; Oldstone, M.B. New world arenavirus Clade C, but not Clade A and B viruses, utilizes alpha-dystroglycan as its major receptor. J. Virol. 2002, 76, 5140–5146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunz, S.; Campbell, K.P.; Oldstone, M.B. Alpha-dystroglycan can mediate arenavirus infection in the absence of beta-dystroglycan. Virology 2003, 316, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojek, J.M.; Spiropoulou, C.F.; Campbell, K.P.; Kunz, S. Old World and Clade C New World arenaviruses mimic the molecular mechanism of receptor recognition used by α-dystroglycan's host-derived ligands. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 5685–5695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imperiali, M.; Sporri, R.; Hewitt, J.; Oxenius, A. Post-translational modification of {alpha}-dystroglycan is not critical for lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus receptor function in vivo. J. Gen. Virol. 2008, 89, 2713–2722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunz, S.; Sevilla, N.; McGavern, D.B.; Campbell, K.P.; Oldstone, M.B. Molecular analysis of the interaction of LCMV with its cellular receptor [alpha]-dystroglycan. J. Cell Biol. 2001, 155, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunz, S.; Rojek, J.M.; Perez, M.; Spiropoulou, C.F.; Oldstone, M.B. Characterization of the interaction of Lassa fever virus with its cellular receptor alpha-dystroglycan. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 5979–5987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunz, S.; Calder, L.; Oldstone, M.B. Electron microscopy of an alpha-dystroglycan fragment containing receptor sites for lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus and laminin, and use of the receptoid body as a reagent to neutralize virus. Virology 2004, 325, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojek, J.M.; Campbell, K.P.; Oldstone, M.B.A.; Kunz, S. Old World arenavirus infection interferes with the expression of functional α-dystroglycan in the host cell. Mol. Biol. Cell 2007, 18, 4493–4507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, D.; McCormick, J.; Johnson, K.; Webb, P.; Komba-Kono, G.; Elliott, L.; Gardner, J. Pathologic and virologic study of fatal Lassa fever in man. Am. J. Pathol. 1982, 107, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shimojima, M.; Ströher, U.; Ebihara, H.; Feldmann, H.; Kawaoka, Y. Identification of cell surface molecules involved in dystroglycan-independent Lassa virus cell entry. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 2067–2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sullivan, B.M.; Welch, M.J.; Lemke, G.; Oldstone, M.B. Is the TAM receptor Axl A receptor for lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus? J. Virol. 2013, 87, 4071–4074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beier, J.I.; Jokinen, J.D.; Holz, G.E.; Whang, P.S.; Martin, A.M.; Warner, N.L.; Arteel, G.E.; Lukashevich, I.S. Novel mechanism of arenavirus-induced liver pathology. PloS ONE 2015, 10, e0122839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibraghimov-Beskrovnaya, O.; Milatovich, A.; Ozcelik, T.; Yang, B.; Koepnick, K.; Francke, U.; Campbell, K.P. Human dystroglycan: Skeletal muscle cDNA, genomic structure, origin of tissue specific isoforms and chromosomal localization. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1993, 2, 1651–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lukashevich, I.S. Reproduction of Lassa virus in different cell cultures. Acta Virol. 1983, 27, 282–285. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jae, L.T.; Raaben, M.; Herbert, A.S.; Kuehne, A.I.; Wirchnianski, A.S.; Soh, T.K.; Stubbs, S.H.; Janssen, H.; Damme, M.; Saftig, P.; et al. Virus entry. Lassa virus entry requires a trigger-induced receptor switch. Science 2014, 344, 1506–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radoshitzky, S.R.; Abraham, J.; Spiropoulou, C.F.; Kuhn, J.H.; Nguyen, D.; Li, W.; Nagel, J.; Schmidt, P.J.; Nunberg, J.H.; Andrews, N.C.; et al. Transferrin receptor 1 is a cellular receptor for New World haemorrhagic fever arenaviruses. Nature 2007, 446, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flanagan, M.L.; Oldenburg, J.; Reignier, T.; Holt, N.; Hamilton, G.A.; Martin, V.K.; Cannon, P.M. New World Clade B arenaviruses can use transferrin receptor 1 (TfR1)-dependent and -independent entry pathways, and glycoproteins from human pathogenic strains are associated with the use of TfR1. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 938–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojek, J.M.; Kunz, S. Cell entry by human pathogenic arenaviruses. Cell. Microbiol. 2008, 10, 828–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helguera, G.; Jemielity, S.; Abraham, J.; Cordo, S.M.; Martinez, M.G.; Rodriguez, J.A.; Bregni, C.; Wang, J.J.; Farzan, M.; Penichet, M.L.; et al. An antibody recognizing the apical domain of human transferrin receptor 1 efficiently inhibits the entry of all New World hemorrhagic fever arenaviruses. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 4024–4028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radoshitzky, S.R.; Kuhn, J.H.; Spiropoulou, C.F.; Albarino, C.G.; Nguyen, D.P.; Salazar-Bravo, J.; Dorfman, T.; Lee, A.S.; Wang, E.; Ross, S.R.; et al. Receptor determinants of zoonotic transmission of New World hemorrhagic fever arenaviruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 2664–2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Fatal illnesses associated with a New World arenavirus—California, 1999–2000. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2000, 49, 709–711. [Google Scholar]

- Enserink, M. Emerging diseases. New arenavirus blamed for recent deaths in California. Science 2000, 289, 842–843. [Google Scholar]

- Milazzo, M.L.; Campbell, G.L.; Fulhorst, C.F. Novel arenavirus infection in humans, United States. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2011, 17, 1417–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hueffer, K.; Parker, J.S.; Weichert, W.S.; Geisel, R.E.; Sgro, J.Y.; Parrish, C.R. The natural host range shift and subsequent evolution of canine parvovirus resulted from virus-specific binding to the canine transferrin receptor. J. Virol. 2003, 77, 1718–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, S.R.; Schofield, J.J.; Farr, C.J.; Bucan, M. Mouse transferrin receptor 1 is the cell entry receptor for mouse mammary tumor virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 12386–12390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demogines, A.; Abraham, J.; Choe, H.; Farzan, M.; Sawyer, S.L. Dual host-virus arms races shape an essential housekeeping protein. PLoS Biol. 2013, 11, e1001571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choe, H.; Jemielity, S.; Abraham, J.; Radoshitzky, S.R.; Farzan, M. Transferrin receptor 1 in the zoonosis and pathogenesis of New World hemorrhagic fever arenaviruses. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2011, 14, 476–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, M.G.; Bialecki, M.A.; Belouzard, S.; Cordo, S.M.; Candurra, N.A.; Whittaker, G.R. Utilization of human DC-SIGN and l-SIGN for entry and infection of host cells by the New World arenavirus, Junin virus. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2013, 441, 612–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eschli, B.; Quirin, K.; Wepf, A.; Weber, J.; Zinkernagel, R.; Hengartner, H. Identification of an N-terminal trimeric coiled-coil core within arenavirus glycoprotein 2 permits assignment to class I viral fusion proteins. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 5897–5907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallaher, W.R.; DiSimone, C.; Buchmeier, M.J. The viral transmembrane superfamily: Possible divergence of arenavirus and filovirus glycoproteins from a common RNA virus ancestor. BMC Microbiol. 2001, 1, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- York, J.; Nunberg, J.H. Distinct requirements for signal peptidase processing and function in the stable signal peptide subunit of the Junín virus envelope glycoprotein. Virology 2007, 359, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quirin, K.; Eschli, B.; Scheu, I.; Poort, L.; Kartenbeck, J.; Helenius, A. Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus uses a novel endocytic pathway for infectious entry via late endosomes. Virology 2008, 378, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasqual, G.; Rojek, J.M.; Masin, M.; Chatton, J.-Y.; Kunz, S. Old World arenaviruses enter the host cell via the multivesicular body and depend on the endosomal sorting complex required for transport. PLoS Pathogens 2011, 7, e1002232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hass, M.; Gölnitz, U.; Müller, S.; Becker-Ziaja, B.; Günther, S. Replicon system for Lassa virus. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 13793–13803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.J.; Novella, I.S.; Teng, M.N.; Oldstone, M.B.A.; de la Torre, J.C. NP and L proteins of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) are sufficient for efficient transcription and replication of LCMV genomic RNA analogs. J. Virol. 2000, 74, 3470–3477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López, N.; Jácamo, R.; Franze-Fernández, M.T. Transcription and RNA replication of Tacaribe virus genome and antigenome analogs require N and L proteins: Z protein is an inhibitor of these processes. J. Virol. 2001, 75, 12241–12251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vieth, S.; Torda, A.E.; Asper, M.; Schmitz, H.; Günther, S. Sequence analysis of L RNA of Lassa virus. Virology 2004, 318, 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunotte, L.; Lelke, M.; Hass, M.; Kleinsteuber, K.; Becker-Ziaja, B.; Günther, S. Domain structure of Lassa virus L protein. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunotte, L.; Kerber, R.; Shang, W.; Hauer, F.; Hass, M.; Gabriel, M.; Lelke, M.; Busch, C.; Stark, H.; Svergun, D.I.; et al. Structure of the Lassa virus nucleoprotein revealed by X-ray crystallography, small-angle X-ray scattering, and electron microscopy. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 38748–38756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poch, O.; Sauvaget, I.; Delarue, M.; Tordo, N. Identification of four conserved motifs among the RNA-dependent polymerase encoding elements. EMBO J. 1989, 8, 3867–3874. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lehmann, M.; Pahlmann, M.; Jerome, H.; Busch, C.; Lelke, M.; Gunther, S. Role of the C terminus of Lassa virus L protein in viral mRNA synthesis. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 8713–8717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morin, B.; Coutard, B.; Lelke, M.; Ferron, F.; Kerber, R.; Jamal, S.; Frangeul, A.; Baronti, C.; Charrel, R.; de Lamballerie, X.; et al. The N-terminal domain of the arenavirus L protein is an RNA endonuclease essential in mRNA transcription. PLoS Pathogens 2010, 6, e1001038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallat, G.D.; Huang, Q.; Wang, W.; Dong, H.; Ly, H.; Liang, Y.; Dong, C. High-resolution structure of the N-terminal endonuclease domain of the Lassa virus L polymerase in complex with magnesium ions. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e87577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raju, R.; Raju, L.; Hacker, D.; Garcin, D.; Compans, R.; Kolakofsky, D. Nontemplated bases at the 5' ends of Tacaribe virus mRNAs. Virology 1990, 74, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Lan, S.; Wang, W.; Schelde, L.M.; Dong, H.; Wallat, G.D.; Ly, H.; Liang, Y.; Dong, C. Cap binding and immune evasion revealed by Lassa nucleoprotein structure. Nature 2010, 468, 779–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linero, F.; Welnowska, E.; Carrasco, L.; Scolaro, L. Participation of eIF4F complex in Junin virus infection: Blockage of eIF4E does not impair virus replication. Cell. Microbiol. 2013, 15, 1766–1782. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- D'Antuono, A.; Loureiro, M.E.; Foscaldi, S.; Marino-Buslje, C.; Lopez, N. Differential contributions of Tacaribe arenavirus nucleoprotein N-terminal and C-terminal residues to nucleocapsid functional activity. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 6492–6505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornu, T.I.; de la Torre, J.C. Ring finger Z protein of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) inhibits transcription and RNA replication of an LCMV S-segment minigenome. J. Virol. 2001, 75, 9415–9426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornu, T.I.; Feldmann, H.; de la Torre, J.C. Cells expressing the ring finger Z protein are resistant to arenavirus infection. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 2979–2983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornu, T.I.; de la Torre, J.C. Characterization of the arenavirus ring finger Z protein regions required for Z-mediated inhibition of viral RNA synthesis. J. Virol. 2002, 76, 6678–6688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kranzusch, P.J.; Whelan, S.P.J. Arenavirus Z protein controls viral RNA synthesis by locking a polymerase–promoter complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 19743–19748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eichler, R.; Lenz, O.; Strecker, T.; Garten, W. Signal peptide of Lassa virus glycoprotein GPC exhibits an unusual length. FEBS Lett. 2003, 538, 203–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beyer, W.R.; Pöpplau, D.; Garten, W.; von Laer, D.; Lenz, O. Endoproteolytic processing of the lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus glycoprotein by the subtilase SKI-1/S1P. J. Virol. 2003, 77, 2866–2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burri, D.J.; Pasqual, G.; Rochat, C.; Seidah, N.G.; Pasquato, A.; Kunz, S. Molecular characterization of the processing of arenavirus envelope glycoprotein precursors by subtilisin kexin isozyme-1/site-1 protease. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 4935–4946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenz, O.; ter Meulen, J.; Klenk, H.-D.; Seidah, N.G.; Garten, W. The Lassa virus glycoprotein precursor GPC is proteolytically processed by subtilase SKI-1/S1P. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 12701–12705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, K.E.; Spiro, R.C.; Burns, J.W.; Buchmeier, M.J. Post-translational processing of the glycoproteins of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus. Virology 1990, 177, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eichler, R.; Lenz, O.; Garten, W.; Strecker, T. The role of single N-glycans in proteolytic processing and cell surface transport of the Lassa virus glycoprotein GPC. Virol. J. 2006, 3, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loureiro, M.E.; Wilda, M.; Levingston Macleod, J.M.; D'Antuono, A.; Foscaldi, S.; Buslje, C.M.; Lopez, N. Molecular determinants of arenavirus Z protein homo-oligomerization and l polymerase binding. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 12304–12314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bieniasz, P.D. Late budding domains and host proteins in enveloped virus release. Virology 2006, 344, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Im, Y.J.; Kuo, L.; Ren, X.; Burgos, P.V.; Zhao, X.Z.; Liu, F.; Burke, T.R., Jr.; Bonifacino, J.S.; Freed, E.O.; Hurley, J.H. Crystallographic and functional analysis of the ESCRT-I/HIV-1 gag PTAP interaction. Structure 2010, 18, 1536–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freed, E.O. Viral late domains. J. Virol. 2002, 76, 4679–4687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loureiro, M.E.; D’Antuono, A.; Levingston Macleod, J.M.; López, N. Uncovering viral protein-protein interactions and their role in arenavirus life cycle. Viruses 2012, 4, 1651–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capul, A.A.; Perez, M.; Burke, E.; Kunz, S.; Buchmeier, M.J.; de la Torre, J.C. Arenavirus Z-glycoprotein association requires Z myristoylation but not functional RING or late domains. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 9451–9460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casabona, J.C.; Levingston Macleod, J.M.; Loureiro, M.E.; Gomez, G.A.; Lopez, N. The RING domain and the L79 residue of Z protein are involved in both the rescue of nucleocapsids and the incorporation of glycoproteins into infectious chimeric arenavirus-like particles. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 7029–7039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortiz-Riaño, E.; Cheng, B.Y.H.; de la Torre, J.C.; Martínez-Sobrido, L. The C-terminal region of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus nucleoprotein contains distinct and segregable functional domains involved in NP-Z interaction and counteraction of the type I interferon response. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 13038–13048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levingston Macleod, J.M.; D'Antuono, A.; Loureiro, M.E.; Casabona, J.C.; Gomez, G.A.; Lopez, N. Identification of two functional domains within the arenavirus nucleoprotein. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 2012–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Danzy, S.; Kumar, N.; Ly, H.; Liang, Y. Biological roles and functional mechanisms of arenavirus Z protein in viral replication. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 9794–9801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kentsis, A.; Gordon, R.E.; Borden, K.L.B. Self-assembly properties of a model RING domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 667–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolff, S.; Ebihara, H.; Groseth, A. Arenavirus budding: A common pathway with mechanistic differences. Viruses 2013, 5, 528–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinschewer, D.D.; Perez, M.; de la Torre, J.C. Dual role of the lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus intergenic region in transcription termination and virus propagation. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 4519–4526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smelt, S.C.; Borrow, P.; Kunz, S.; Cao, W.; Tishon, A.; Lewicki, H.; Campbell, K.P.; Oldstone, M.B.A. Differences in affinity of binding of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus strains to the cellular receptor α-dystroglycan correlate with viral tropism and disease kinetics. J. Virol. 2001, 75, 448–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, K.G.; Shylakhter, I.; Tabrizi, S.; Grossman, S.R.; Happi, C.T.; Sabeti, P.C. Genome-wide scans provide evidence for positive selection of genes implicated in Lassa fever. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 2012, 367, 868–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabeti, P.C.; Varilly, P.; Fry, B.; Lohmueller, J.; Hostetter, E.; Cotsapas, C.; Xie, X.; Byrne, E.H.; McCarroll, S.A.; Gaudet, R.; et al. Genome-wide detection and characterization of positive selection in human populations. Nature 2007, 449, 913–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, C.J. Human infection with arenaviruses in the Americas. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2002, 262, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Maiztegui, J.I. Clinical and epidemiological patterns of Argentine haemorrhagic fever. Bull World Health Organ 1975, 52, 567–575. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Abraham, J.; Kwong, J.A.; Albariño, C.G.; Lu, J.G.; Radoshitzky, S.R.; Salazar-Bravo, J.; Farzan, M.; Spiropoulou, C.F.; Choe, H. Host-species transferrin receptor 1 orthologs are cellular receptors for nonpathogenic New World Clade B arenaviruses. PLoS Pathogens 2009, 5, e1000358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reignier, T.; Oldenburg, J.; Flanagan, M.L.; Hamilton, G.A.; Martin, V.K.; Cannon, P.M. Receptor use by the Whitewater Arroyo virus glycoprotein. Virology 2008, 371, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, N.; Wang, J.; Lan, S.; Danzy, S.; McLay Schelde, L.; Seladi-Schulman, J.; Ly, H.; Liang, Y. Characterization of virulence-associated determinants in the envelope glycoprotein of Pichinde virus. Virology 2012, 433, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aronson, J.; Herzog, N.; Jerrells, T. Pathological and virological features of arenavirus disease in guinea pigs. Comparison of two Pichinde virus strains. Am. J. Pathol. 1994, 145, 228–235. [Google Scholar]

- Jahrling, P.B.; Hesse, R.A.; Rhoderick, J.B.; Elwell, M.A.; Moe, J.B. Pathogenesis of a Pichinde virus strain adapted to produce lethal infections in guinea pigs. Infect. Immun. 1981, 32, 872–880. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Albariño, C.G.; Bird, B.H.; Chakrabarti, A.K.; Dodd, K.A.; Flint, M.; Bergeron, É.; White, D.M.; Nichol, S.T. The major determinant of attenuation in mice of the Candid1 vaccine for Argentine hemorrhagic fever is located in the G2 glycoprotein transmembrane domain. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 10404–10408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Droniou-Bonzom, M.E.; Reignier, T.; Oldenburg, J.E.; Cox, A.U.; Exline, C.M.; Rathbun, J.Y.; Cannon, P.M. Substitutions in the glycoprotein (GP) of the Candid#1 vaccine strain of Junin virus increase dependence on human transferrin receptor 1 for entry and destabilize the metastable conformation of GP. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 13457–13462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lukashevich, I.S.; Carrion, R.; Salvato, M.S.; Mansfield, K.; Brasky, K.; Zapata, J.; Cairo, C.; Goicochea, M.; Hoosien, G.E.; Ticer, A.; et al. Safety, immunogenicity, and efficacy of the ML29 reassortant vaccine for Lassa fever in small non-human primates. Vaccine 2008, 26, 5246–5254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrion, R.; Patterson, J.L.; Johnson, C.; Gonzales, M.; Moreira, C.R.; Ticer, A.; Brasky, K.; Hubbard, G.B.; Moshkoff, D.; Zapata, J.; et al. A ML29 reassortant virus protects guinea pigs against a distantly related Nigerian strain of Lassa virus and can provide sterilizing immunity. Vaccine 2007, 25, 4093–4102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harnish, D.G.; Dimock, K.; Bishop, D.H.; Rawls, W.E. Gene mapping in Pichinde virus: Assignment of viral polypeptides to genomic L and S RNAs. J. Virol. 1983, 46, 638–641. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Riviere, Y.; Oldstone, M.B. Genetic reassortants of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus: Unexpected disease and mechanism of pathogenesis. J. Virol. 1986, 59, 363–368. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lukashevich, I.S.; Carrion, R., Jr.; Salvato, M.S.; Mansfield, K.; Brasky, K.; Zapata, J.; Cairo, C.; Goicochea, M.; Hoosien, G.E.; Ticer, A.; et al. Safety, immunogenicity, and efficacy of the ML29 reassortant vaccine for Lassa fever in small non-human primates. Vaccine 2008, 26, 5246–5254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xing, J.; Ly, H.; Liang, Y. The Z proteins of pathogenic but not nonpathogenic arenaviruses inhibit RIG-i-like receptor-dependent interferon production. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 2944–2955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, L.; Briese, T.; Lipkin, W.I. Z proteins of New World arenaviruses bind RIG-i and interfere with type I interferon induction. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 1785–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moshkoff, D.A.; Salvato, M.S.; Lukashevich, I.S. Molecular characterization of a reassortant virus derived from Lassa and Mopeia viruses. Virus Genes 2007, 34, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, K.M.; McCormick, J.B.; Webb, P.A.; Smith, E.S.; Elliott, L.H.; King, I.J. Clinical virology of Lassa fever in hospitalized patients. J. Infect. Dis. 1987, 155, 456–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergthaler, A.; Flatz, L.; Hegazy, A.N.; Johnson, S.; Horvath, E.; Löhning, M.; Pinschewer, D.D. Viral replicative capacity is the primary determinant of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus persistence and immunosuppression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 21641–21646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matloubian, M.; Kolhekar, S.R.; Somasundaram, T.; Ahmed, R. Molecular determinants of macrophage tropism and viral persistence: Importance of single amino acid changes in the polymerase and glycoprotein of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus. J. Virol. 1993, 67, 7340–7349. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Albariño, C.G.; Bird, B.H.; Chakrabarti, A.K.; Dodd, K.A.; Erickson, B.R.; Nichol, S.T. Efficient rescue of recombinant Lassa virus reveals the influence of S segment noncoding regions on virus replication and virulence. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 4020–4024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLay, L.; Lan, S.; Ansari, A.; Liang, Y.; Ly, H. Identification of virulence determinants within the L genomic segment of the Pichinde arenavirus. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 6635–6643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Sobrido, L.; Zúñiga, E.I.; Rosario, D.; García-Sastre, A.; de la Torre, J.C. Inhibition of the type I interferon response by the nucleoprotein of the prototypic arenavirus lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 9192–9199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, X.; Huang, Q.; Wang, W.; Dong, H.; Ly, H.; Liang, Y.; Dong, C. Structures of arenaviral nucleoproteins with triphosphate dsRNA reveal a unique mechanism of immune suppression. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 16949–16959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hastie, K.M.; Kimberlin, C.R.; Zandonatti, M.A.; MacRae, I.J.; Saphire, E.O. Structure of the Lassa virus nucleoprotein reveals a dsRNA-specific 3′ to 5′ exonuclease activity essential for immune suppression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 2396–2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Q.; Shao, J.; Lan, S.; Zhou, Y.; Xing, J.; Dong, C.; Liang, Y.; Ly, H. In vitro and in vivo characterizations of the Pichinde viral NP exoribonuclease function. J. Virol. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnec, X.; Baize, S.; Reynard, S.; Diancourt, L.; Caro, V.; Tordo, N.; Bouloy, M. Lassa virus nucleoprotein mutants generated by reverse genetics induce a robust type I interferon response in human dendritic cells and macrophages. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 12093–12097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russier, M.; Reynard, S.; Carnec, X.; Baize, S. The exonuclease domain of Lassa virus nucleoprotein is involved in antigen-presenting-cell-mediated NK cell responses. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 13811–13820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pythoud, C.; Rodrigo, W.W.S.I.; Pasqual, G.; Rothenberger, S.; Martínez-Sobrido, L.; de la Torre, J.C.; Kunz, S. Arenavirus nucleoprotein targets interferon regulatory factor-activating kinase IKKε. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 7728–7738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigo, W.W.S.I.; Ortiz-Riaño, E.; Pythoud, C.; Kunz, S.; de la Torre, J.C.; Martínez-Sobrido, L. Arenavirus nucleoproteins prevent activation of Nuclear factor Kappa b. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 8185–8197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, S.; Cerny, A.M.; Zacharia, A.; Fitzgerald, K.A.; Kurt-Jones, E.A.; Finberg, R.W. Induction and inhibition of type I interferon responses by distinct components of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus. J. Virology 2010, 84, 9452–9462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahanty, S.; Hutchinson, K.; Agarwal, S.; Mcrae, M.; Rollin, P.E.; Pulendran, B. Cutting edge: Impairment of dendritic cells and adaptive immunity by Ebola and Lassa viruses. J. Immunol. 2003, 170, 2797–2801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baize, S.; Kaplon, J.; Faure, C.; Pannetier, D.; Georges-Courbot, M.-C.; Deubel, V. Lassa virus infection of human dendritic cells and macrophages is productive but fails to activate cells. J. Immunol. 2004, 172, 2861–2869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lukashevich, I.S.; Maryankova, R.; Vladyko, A.S.; Nashkevich, N.; Koleda, S.; Djavani, M.; Horejsh, D.; Voitenok, N.N.; Salvato, M.S. Lassa and Mopeia virus replication in human monocytes/macrophages and in endothelial cells: Different effects on IL-8 and TNF-alpha gene expression. J. Med. Virol. 1999, 59, 552–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pannetier, D.; Faure, C.; Georges-Courbot, M.-C.; Deubel, V.; Baize, S. Human macrophages, but not dendritic cells, are activated and produce alpha/beta interferons in response to Mopeia virus infection. J. Virology 2004, 78, 10516–10524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groseth, A.; Hoenen, T.; Weber, M.; Wolff, S.; Herwig, A.; Kaufmann, A.; Becker, S. Tacaribe virus but not Junin virus infection induces cytokine release from primary human monocytes and macrophages. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2011, 5, e1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lukashevich, I.S. The search for animal models for Lassa fever vaccine development. Exp. Rev. Vaccines 2013, 12, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vela, E. Animal models, prophylaxis, and therapeutics for arenavirus infections. Viruses 2012, 4, 1802–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safronetz, D.; Geisbert, T.W.; Feldmann, H. Animal models for highly pathogenic emerging viruses. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2013, 3, 205–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jahrling, P.B.; Smith, S.; Hesse, R.A.; Rhoderick, J.B. Pathogenesis of Lassa virus infection in guinea pigs. Infect. Immun. 1982, 37, 771–778. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Peters, C.J.; Jahrling, P.B.; Liu, C.T.; Kenyon, R.H.; McKee, K.T., Jr.; Barrera Oro, J.G. Experimental studies of arenaviral hemorrhagic fevers. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 1987, 134, 5–68. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Carrion, R., Jr.; Brasky, K.; Mansfield, K.; Johnson, C.; Gonzales, M.; Ticer, A.; Lukashevich, I.; Tardif, S.; Patterson, J. Lassa virus infection in experimentally infected marmosets: Liver pathology and immunophenotypic alterations in target tissues. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 6482–6490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, E.P.; Aronson, J.F. Cytokine patterns in a comparative model of arenavirus haemorrhagic fever in guinea pigs. J. Gen. Virol. 2008, 89, 2569–2579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Y.; Lan, S.; Ly, H. Molecular determinants of Pichinde virus infection of guinea pigs—A small animal model system for arenaviral hemorrhagic fevers. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2009, 1171 Suppl 1, E65–E74. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jahrling, P.B.; Hesse, R.A.; Eddy, G.A.; Johnson, K.M.; Callis, R.T.; Stephen, E.L. Lassa virus infection of rhesus monkeys: Pathogenesis and treatment with ribavirin. J. Infect. Dis. 1980, 141, 580–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lange, J.V.; Mitchell, S.W.; McCormick, J.B.; Walker, D.H.; Evatt, B.L.; Ramsey, R.R. Kinetic study of platelets and fibrinogen in Lassa virus-infected monkeys and early pathologic events in Mopeia virus-infected monkeys. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1985, 34, 999–1007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Callis, R.T.; Jahrling, P.B.; DePaoli, A. Pathology of Lassa virus infection in the rhesus monkey. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1982, 31, 1038–1045. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fisher-Hoch, S.P.; Mitchell, S.W.; Sasso, D.R.; Lange, J.V.; Ramsey, R.; McCormick, J.B. Physiological and immunologic disturbances associated with shock in a primate model of Lassa fever. J. Infect. Dis. 1987, 155, 465–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hensley, L.E.; Smith, M.A.; Geisbert, J.B.; Fritz, E.A.; Daddario-DiCaprio, K.M.; Larsen, T.; Geisbert, T.W. Pathogenesis of Lassa fever in cynomolgus macaques. Virol. J. 2011, 8, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safronetz, D.; Strong, J.E.; Feldmann, F.; Haddock, E.; Sogoba, N.; Brining, D.; Geisbert, T.W.; Scott, D.P.; Feldmann, H. A recently isolated Lassa virus from Mali demonstrates atypical clinical disease manifestations and decreased virulence in cynomolgus macaques. J. Infect. Dis. 2013, 207, 1316–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasmussen, A.L.; Tchitchek, N.; Safronetz, D.; Carter, V.S.; Williams, C.M.; Haddock, E.; Korth, M.J.; Feldmann, H.; Katze, M.G. Delayed inflammatory and cell death responses are associated with reduced pathogenicity in Lujo virus-infected cynomolgus macaques. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 2543–2552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baize, S.; Marianneau, P.; Loth, P.; Reynard, S.; Journeaux, A.; Chevallier, M.; Tordo, N.; Deubel, V.; Contamin, H. Early and strong immune responses are associated with control of viral replication and recovery in Lassa virus-infected cynomolgus monkeys. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 5890–5903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).