Abstract

Avian haemosporidians have been widely studied because they provide important insights into parasite distribution and diversity. However, most available data come from passerines, resulting in gaps regarding other bird groups, primarily due to the difficulty of sampling non-passerines in natural environments. Thus, we aimed to detect infections caused by Plasmodium spp. and Haemoproteus spp. through molecular and morphological analyses of blood samples from non-passerine birds in Midwestern Brazil. We evaluated 344 individuals from 60 species across 16 non-passerine orders. Among them, 18.89% (n = 65) were infected with haemosporidians. Molecular analyses identified four Plasmodium species: P. nucleophilum, which was detected in a broad range of host species; P. juxtanucleare, detected in Gallus gallus; P. paranucleophilum, found to infect Rupornis magnirostris; and P. elongatum in Mustelirallus albicollis. Additionally, an undescribed Plasmodium lineage was detected in Nycticorax nycticorax. We also identified four new Haemoproteus lineages infecting Patagioenas picazuro, Asio clamator, Athene cunicularia, and Tyto furcata. Additionally, the haplotype previously described in Mycteria americana was detected once more in this host. By revealing new lineages and expanding knowledge of parasite biodiversity, this study underscores the importance of non-passerine hosts and the need for further research on their evolutionary and host–parasite relationships.

1. Introduction

Avian hemosporidians are heteroxenous protozoa transmitted to birds by hematophagous dipterans during blood feeding. They are classified into four genera: Plasmodium, Haemoproteus, Leucocytozoon, and Fallisia. These parasites occur in nearly all zoogeographic regions, except Antarctica [1]. Among them, the genera Plasmodium and Haemoproteus are particularly significant because of their worldwide distribution and high prevalence in free-living birds [1,2]. The study of interactions between these pathogens and their avian hosts is frequently used as a model for investigating parasite–host dynamics [3].

Approximately 170 morphospecies of Haemoproteus and 55 species of Plasmodium have been described. However, genetic data are available for only 74 Haemoproteus and 24 Plasmodium species [4,5]. Considering that more than 4600 lineages of avian haemosporidians have been detected, a substantial gap remains between morphological and molecular information [6]. The Neotropical region is regarded as a hotspot for avian and hemosporidian diversity, with numerous species yet to be discovered [7]. Brazil harbors one of the world’s greatest avian diversities, with more than 1900 species recorded [8]. Mato Grosso encompasses three biomes, the Amazon, Cerrado, and Pantanal, which contribute to its high avian biodiversity [9].

Despite the significant diversity of haemosporidians, most existing data focus on Passeriformes, which account for 87% of the records in the Avian Malaria Initiative, MalAvi [3,10]. Because of the challenges in capturing non-passerine birds such as Strigiformes, Galliformes, Cariamiformes, and Falconiformes, considerable gaps remain in our understanding of parasitism in many non-passerine avian hosts. Wildlife hospitals, rehabilitation centers, and zoological institutions significantly contribute to enhancing our understanding of hemosporidian diversity within these often underrepresented avian taxa.

In this study, we investigated the occurrence of haemosporidian parasites in non-passerine birds in the state of Mato Grosso, Brazil. Samples were obtained from the Veterinary Hospital of the Federal University of Mato Grosso (HOVET/UFMT), which receives both free-living and captive birds for clinical care and treatment. The Wild Animal Sector of HOVET/UFMT regularly treats birds from various orders. We conducted morphological and molecular characterizations of Plasmodium and Haemoproteus parasites using microscopy, sequencing, and phylogenetic analyses. Research focusing on non-passerine birds from under-sampled regions such as this could provide valuable insights into the biodiversity of haemosporidians in Brazil.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection and Study Area

All avian blood samples were obtained at the Veterinary Hospital of the Federal University of Mato Grosso (HOVET/UFMT), located in the municipality of Cuiabá, Brazil. Sampling was conducted during the routine treatment of wild animals between October 2021 and March 2024. The hospital receives birds from three main sources: free-living birds rescued by Brazilian environmental agencies (the Secretariat of State for the Environment—SEMA—and the Environmental Military Police of Mato Grosso), captive birds from the Center for Medicine and Research in Wild Animals (CEMPAS/UFMT), and pet birds brought in by the public.

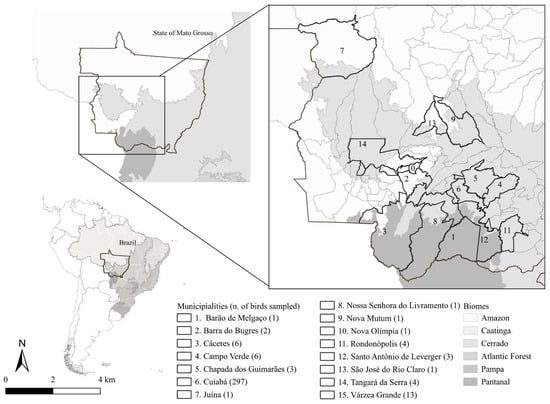

All birds sampled in this study originated from 15 municipalities in the state of Mato Grosso, Brazil (Figure 1). However, most birds sampled in this study originated from the Cerrado biome, with 297 of the 344 individuals (86.34%) collected in Cuiabá, a municipality characterized by a rainy season from October to March, a dry season from April to September, temperatures of 22–27 °C, and an average annual rainfall of ~1500 mm [11]. Only one bird (0.29%) was sampled in the municipality of Juína, within the Amazonia biome, characterized by a super-humid equatorial climate [12]. The remaining 46 birds (13.37%) were collected in municipalities within the Cerrado or in transition zones between the Cerrado and Pantanal biomes. Although the Pantanal is defined by its flood–drought cycle [13], its fauna and flora are similar to those of the Cerrado biome [14].

Figure 1.

Map of Mato Grosso state showing municipalities where birds were screened for Plasmodium spp. and Haemoproteus spp. infections, based on microscopic examination and PCR analysis, from October 2021 to March 2024.

Blood was collected via jugular vein puncture or from another vein deemed more suitable for each species. An aliquot of each blood sample was stored in an EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) tube and frozen at −20 °C until DNA extraction. Additionally, blood smears were prepared using standard procedures and stained with Rosenfeld’s stain [15].

2.2. Microscopic Examination and Morphological Characterization

Blood smears were examined under a Leica DM500 optical microscope at a magnification of 400×. The length of each slide was measured during this process. To image the hemosporidians, an Olympus CX31 light microscope equipped with the Q-Color5 imaging system from Olympus (Tokyo, Japan) and QCapture Pro7 imaging software from QImaging (Surrey, BC, Canada) was used. Microphotographs taken during this examination were used to support the morphological characterization of the observed forms, according to the identification key [1]. Additionally, ImageJ software version 1.54 was employed to measure the parasites, including their structures and positioning within host cells, to aid in species identification [4,5]. Parasitemia was estimated by analyzing 200 microscopic fields at a magnification of 1000× [16]. Only regions of the smears without overlapping erythrocytes were examined, with each field containing approximately 100 cells. The parasitemia intensity was determined by counting the number of parasites per 20,000 total cells.

2.3. Molecular Detection of Plasmodium spp. and Haemoproteus spp.

To diagnose hemosporidians at the molecular level, DNA was extracted using the phenol–chloroform method, followed by isopropanol precipitation, as described by Sambrook and Russell [17]. A total of 20 μL of blood from each bird was used for this process. At the end of the extraction, DNA was eluted in 50 μL of Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer and stored at −20 °C. The extracted DNA was tested using conventional polymerase chain reaction (cPCR), following the methods described by Fallon et al. [18], to detect a 154-base-pair (bp) ribosomal RNA coding sequence within the mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) of haemosporidians in the genera Plasmodium and Haemoproteus. For the PCR reactions, 2 µL of DNA were amplified with primers 343F (5′-GCTCACGCATCGCTTCT-3′) and 496R (5′-GACCGGTCATTTTCTTTG-3′) under thermocycling conditions based on the protocol described by Roos et al. [19]: initial denaturation for 2 min at 94 °C followed by 35 cycles with 1 min denaturation at 94 °C, 1 min annealing at 62 °C, and 1 min 10 s extension at 72 °C, with a final extension for 3 min at 72 °C.

All positive samples were subsequently subjected to nested PCR (nPCR) to amplify a 478 bp fragment of the mitochondrial cytochrome b (cytb) gene of Plasmodium and Haemoproteus, as described by Hellgren et al. [20]. For the first PCR reaction, 2 μL of DNA was combined with the primers HaemNFI (5′-CATATATTAAGAGAAITATGGAG-3′) and HaemNR3 (5′-ATAGAAAGATAAGAAATACCATTC-3′) under thermocycling conditions: 30 s at 94 °C, 30 s at 50 °C, and 45 s at 72 °C for 20 cycles. The samples were incubated before the cyclic reaction at 94 °C for 3 min and after the cyclic reaction at 72 °C for 10 min. In the second reaction, 1 μL of the amplified product from the first reaction was used together with the primers HaemF (5′-ATGGTGCTTTCGATATATGCATG-3′) and HaemR2 (5′-GCATTATCTGGATGTGATAATGGT-3′) under the same conditions as in the first reaction, but with 35 cycles. All PCRs used Plasmodium gallinaceum as the positive control and sterile ultrapure water as the negative control.

The nPCR-positive samples were purified following the protocol described by Sambrook and Russell [17] and sequenced using the dideoxynucleotide chain-termination method originally developed by Sanger et al. [21]. Sequencing was performed at the René Rachou Research Institute in Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil, using an ABI 3730 DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA), a capillary electrophoresis-based automatic sequencer.

2.4. Phylogenetic Analysis

We edited and verified the quality of the recovered sequences using ChromasPro software (Technelysium Pty Ltd., South Brisbane, Australia). These sequences were compared with those available in GenBank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/, accessed on 13 September 2024) and the MalAvi database [6]. The sequences were aligned using MUSCLE in MEGA11 software [22]. A divergence of one or more nucleotides was considered sufficient to describe distinct cytb lineages [23].

The best-fit model for phylogenetic analysis was selected using IQ-TREE software [24], resulting in a partitioned model with the following schemes: partition 1—K3Pu+F+ASC+R2; partitions 2 and 3—GTR+F+ASC+R4. Model selection was based on the most appropriate nucleotide substitution rate for each codon partition. For phylogenetic inferences using Bayesian analysis, Mr.Bayes version 3.2.7 [25] was employed. Two Markov chains were run simultaneously for 1,000,000 generations, with samples taken every 1000 generations. The first 250,000 trees, representing 25% of the total, were discarded, and the remaining trees were used to calculate posterior probabilities. In this analysis, Leucocytozoon cariamae was used as an out-group [26].

3. Results

3.1. Occurrence of Haemosporidian Infection

Overall, 65 of the 344 birds (18.89%) tested positive for Plasmodium or Haemoproteus using at least one of three diagnostic techniques: blood smear, cPCR, and nPCR. Free-living birds comprised the majority of the sample, 61.63% (n = 212), while captive birds represented 38.37% (n = 132) (Table 1). Regarding the origin of the positive birds, 17.92% (n = 38) were wild and 20.45% (n = 27) were captive, indicating that captive birds exhibited a slightly higher infection rate in this study.

Table 1.

Origin of bird species treated in the Wild Animal Sector of the Veterinary Hospital at the Federal University of Mato Grosso, Cuiabá, MT, from October 2021 to March 2024, and screened for the morphological and/or molecular detection of Plasmodium spp. and Haemoproteus spp.

3.2. Molecular and Phylogenetic Analysis of Plasmodium spp.

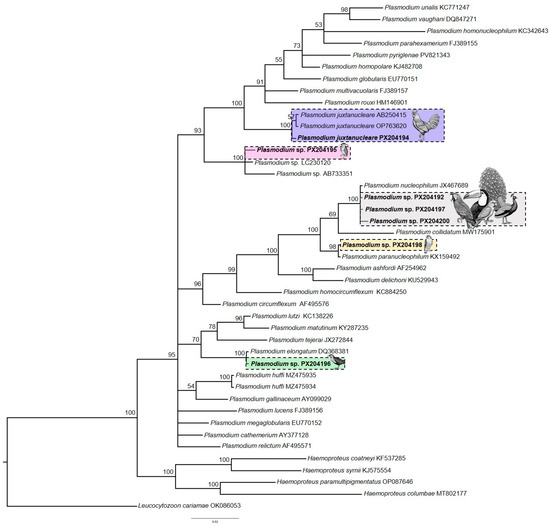

Based on molecular data, we found 11 birds infected with Plasmodium lineages, nine of which yielded sequences of sufficient quality to achieve identity in GenBank. Three sequences showing more than 99% identity with P. nucleophilum were detected in four different host species: Red-and-green Macaw (Ara chloropterus), Indian Peafowl (Pavo cristatus), White-eyed Parakeet (Psittacara leucophtalmus), and Toco toucan (Ramphastos toco) (Table 2). In the phylogenetic reconstruction using Bayesian inference, these sequences clustered with haplotype JX467689, indicating that they belonged to the P. nucleophilum clade (Figure 2). No parasite erythrocytic forms were observed in any of the analyzed individuals.

Table 2.

Positive birds of the hospital routine in the Wild Animal Sector at the Veterinary Hospital of the Federal University of Mato Grosso, Cuiabá, MT, from October 2021 to March 2024, submitted to the morphological and/or molecular detection of Plasmodium spp. and Haemoproteus spp.

Figure 2.

Bayesian phylogenetic inference based on 478 nucleotides of the cytochrome b gene. The Plasmodium sequences identified in this study are highlighted in bold, along with other Plasmodium sequences obtained from GenBank and MalAvi. Leucocytozoon cariamae CARCRI01 (accession No. OK086053) was used as the out-group.

We also detected two Roadside Hawks (Rupornis magnirostris) infected with lineages RUPMAGS-1335 and RUPMAGS-1328 (GenBank accession: PX204193 and PX204198), both of which showed 100% similarity to sequence KX159495 of P. paranucleophilum. Microscopic examination of blood smears revealed parasitemia levels of 0.005% and 0.015% and confirmed the presence of gametocytes, meronts, and trophozoites (see Supplementary Figure S1). P. nucleophilum and P. paranucleophilum are closely related phylogenetically, forming a subclade with P. collidatum (Figure 2).

Sequences of P. juxtanucleare (PX204194) and P. elongatum were identified in the Domestic Chicken (Gallus gallus) and Ash-throated Crake (Mustelirallus albicollis). Although no blood stages of the parasite were observed in the smears, the morphospecies was confirmed based on the recovered sequences, which showed 100% similarity to previously deposited database entries. Another sequence was recovered from a Black-Crowned Night-Heron (Nycticorax nycticorax) individual (PX204195), which clustered phylogenetically within a clade of lineages not yet associated with any described morphospecies (Figure 2). Blood smear analysis revealed 0.12% parasitemia, and only gametocytes were observed, limiting the morphological characterization of this parasite (see Supplementary Figure S1).

3.3. Molecular, Phylogenetic, and Morphological Analysis of Haemoproteus spp.

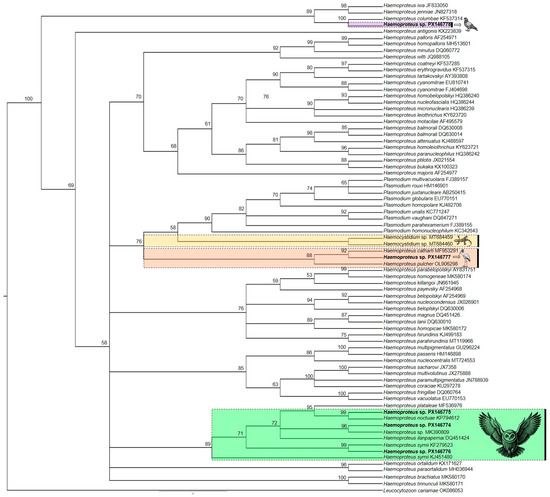

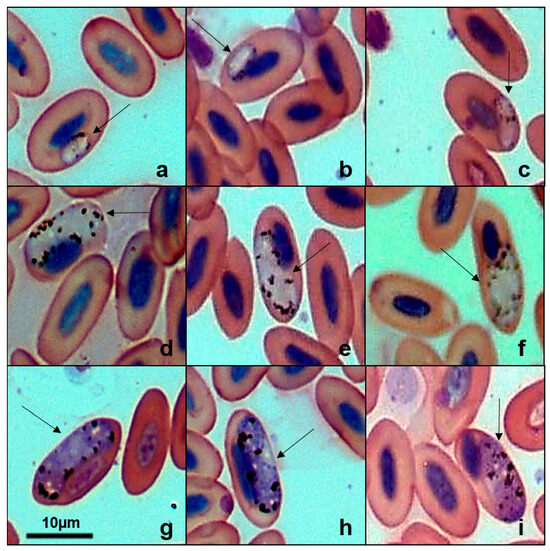

Five lineages of Haemoproteus were found in 344 birds (Table 2), with four new lineages deposited in GenBank: Burrowing Owl (Athene cunicularia) (PX146775), Striped Owl (Asio clamator) (PX146776), Picazuro Pigeon (Patagioenas picazuro) (PX146778), and American Barn Owl (Tyto furcata) (PX146774). The unpublished haplotype identified in P. picazuro showed 98.54% sequence similarity with lineage MN065207 previously reported in Rock Pigeons (Columba livia). Our phylogenetic analysis (Figure 3) clustered these two haplotypes, but it was not possible to determine the morphospecies associated with this lineage. From Wood Stork (Mycteria americana), we recovered the lineage MYCAMES-1685 (GenBank accession: PX146777), which showed 100% similarity with lineage MYCAMH1 (GenBank accession: JX546141). Phylogenetically, this sequence clustered in a distinct clade, separate from other Haemoproteus species, including the morphospecies Haemoproteus catharti and H. pulcher. Examination of blood smears from M. americana revealed gametocytes infecting erythrocytes (Figure 4) with a parasitemia rate of 0.16%. However, we were unable to obtain a detailed morphological description of the parasite.

Figure 3.

Bayesian phylogenetic inference based on 478 nucleotides of the cytochrome b gene. The Haemoproteus sequences identified in this study are highlighted in bold, alongside other Haemoproteus sequences sourced from GenBank and MalAvi. Leucocytozoon cariamae CARCRI01 (accession No. OK086053) serves as the out-group.

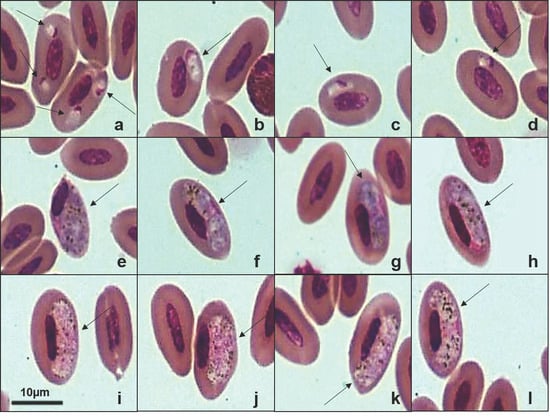

Figure 4.

Plate exhibiting gametocytes of Haemoproteus sp. (GenBank accession: PX146777) from the blood smear of the Wood Stork (Mycteria americana). (a–c): young gametocytes. (d–f): microgametocytes. (g–i): macrogametocytes. The arrows indicate the different parasitic forms inside the red blood cells. Scale bar = 10 μm.

The new lineages detected in A. cunicularia and A. clamator were more than 99% similar to Haemoproteus noctuae and Haemoproteus syrnii (Table 2). However, it was not possible to confirm the morphospecies based on erythrocytic forms. We also identified a new lineage of Haemoproteus sp. (TYTFURS-1384, PX146774) infecting T. furcata, which showed 98.74% sequence identity with lineage MK390809 previously reported in Tyto alba [27]. The host presented gametocytes infecting erythrocytes in blood smears, with a parasitemia rate of 0.2%. Morphologically, these parasites exhibited young oval gametocytes that typically contacted the erythrocyte nucleus and were located in a polar or subpolar position relative to the nucleus (Figure 5a–d). We observed erythrocytes infected with two or more young gametocytes (Figure 5a). Mature gametocytes displayed the classical morphological dimorphism [1] with macrogametocytes having a dense nucleus and more intensely stained cytoplasm compared to microgametocytes. Both microgametocytes and macrogametocytes were elongated and positioned laterally to the erythrocyte nucleus, making contact with the nucleus and cell envelope. The nuclei of the gametocytes were located in distinct areas within the cytoplasm, appearing in both polar (Figure 5h) and central (Figure 5f,l) regions of the parasite. Additionally, malaria pigment and volutin granules were irregularly distributed in both microgametocytes and macrogametocytes. This new haplotype, TYTFURS-1384, is closely related to Haemoproteus ilanpapernai [28] but exhibits distinct morphological characteristics. All Haemoproteus lineages were recovered from the Strigiformes cluster within the same major clade. However, three well-supported subclades separated the morphospecies: H. syrnii, H. noctuae, and H. ilanpapernai. These findings suggest that the parasite infecting T. furcata represents a distinct Haemoproteus species.

Figure 5.

Plate exhibiting gametocytes of Haemoproteus sp. (PX146774) from the blood smear of the American Barn Owl (Tyto furcata). (a–d): young gametocytes. (e–h): macrogametocytes. (i,j,h,l): microgametocytes. The arrows indicate the different parasitic forms inside the red blood cells. Scale bar = 10 μm.

4. Discussion

Most studies on avian hemosporidians have focused on Passeriformes, which are more easily sampled using relatively simple methods such as mist nets [7,29]. Consequently, few studies have encompassed the wide diversity of non-passerine bird orders and species. This study addresses this research gap by examining a diverse range of non-passerine bird species. It revealed a prevalence of haemosporidian infections of 18.89%, with 344 individuals across 60 species and 16 orders in Mato Grosso State, Brazil testing positive. In a related study, Chagas et al. [30] reported a similar prevalence of 18% in free-living birds using PCR-based diagnostic methods, a result very similar to that observed in our wild birds (17.92%). Furthermore, Chagas et al. [31] conducted an extensive study on non-passerines in captivity in São Paulo, including 677 birds from 17 orders and 122 species, and found an infection rate of 12.6% for Plasmodium spp. and/or Haemoproteus spp., therefore lower than the 20.45% infection rate recorded for the captive birds in this study.

To date, no other study in Brazil has examined such a diverse and extensive sample of non-passerine bird species. For example, Belo et al. [32] found that 36% (46 of 127) of avian malaria cases were restricted to captive parrots from three Brazilian zoos. Morel et al. [33] reported an infection rate of 27% (56 of 206) in free-living raptors, whereas Vanstreels et al. [34] detected a prevalence of 64.3% (18 of 28) in captive penguins undergoing rehabilitation. Anjos et al. [35] analyzed 399 birds, most of which belonged to Passeriformes (362 out of 399; 90.7%), and identified only one infected individual among the non-passerines (Apodiformes). In contrast, our study found haemosporidian infections (Haemoproteus and Plasmodium) across 16 non-passerine orders, highlighting the broader host range and ecological significance of these parasites. The data from this bird group in the present study, which presented limited information in the literature, provide relevant insights into haemosporids; however, the lack of morphological data associated with molecular data for some individuals represents a gap that warrants further investigation in future studies.

Detection and characterization of these parasites, as well as understanding their transmission dynamics, are essential to minimizing risks to biodiversity, particularly in species subject to illegal trafficking or facing extinction risk. According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), our sampling included several threatened bird species [36]. Species listed as near threatened (NT), including Harpia harpyja, Alipiopsitta xanthops, Primolius maracana, and Rhea americana, as well as one vulnerable (VU) species, Anodorhynchus hyacinthinus, were sampled for the present study. Although only A. xanthops tested positive for haemosporidians, continued monitoring of these taxa remains crucial for conservation efforts. A large proportion of the IUCN-listed species in our dataset belong to Psittaciformes, a group commonly observed in the wild, maintained in captivity (e.g., zoos), or involved in illegal trade networks [37]. Despite the generally low prevalence of haemosporidian infection in psittaciform birds, these parasites can be pathogenic to them [38,39]. Moreover, environmental and ecological changes may alter parasite–host interactions, potentially affecting bird communities [40].

Over the years, avian Plasmodium species have been recognized as generalist parasites [3]. For example, P. nucleophilum is a cosmopolitan species found in various bird hosts [31]. Using molecular analyses, we identified three distinct sequences from four different hosts that exhibited high similarity and clustered phylogenetically with these morphospecies. However, the lack of morphological data prevented us from confirming whether these birds could serve as competent hosts for the development of P. nucleophilum. Nonetheless, future studies should investigate whether the host species (Ara chloropterus, Pavo cristatus, Psittacara leucophthalmus, and Ramphastos toco) act as potential reservoirs for the spread of this parasite. A. chloropterus and P. leucophthalmus are Neotropical species endemic to the Americas and are frequently targeted in the illegal wildlife trade [41,42,43], which could facilitate parasite transmission. Although P. cristatus is native to India, it is an ornamental species commonly traded and maintained in captivity worldwide [44], potentially contributing to the global distribution of P. nucleophilum. To our knowledge, this is the first report of Plasmodium spp. in A. chloropterus. In the case of P. leucophthalmus, although a report of haemosporidian infection exists, it was not determined whether Plasmodium or Haemoproteus caused the infection. Therefore, this represents the first report of Plasmodium spp. in this host.

Another cosmopolitan and generalist parasite is P. elongatum, a morphospecies that includes several misidentified lineages [4]. In our study, we recovered a lineage identical to sequence DQ368381, which is widely accepted as P. elongatum [4]. Although no morphological data were obtained, M. albicollis should be further investigated as a potential host for this parasite, and this may represent the first report of a hemosporidian infection in this host. We also detected R. magnirostris infections in a lineage associated with the morphospecies P. paranucleophilum. Tostes et al. [45] described P. paranucleophilum in various avian hosts, including R. magnirostris, suggesting a generalist profile. Our findings reinforce the role of R. magnirostris as a competent host of this parasite. In contrast to the generalist species mentioned earlier, we identified a sequence of P. juxtanucleare from its typical host, G. gallus, indicating that this parasite has a more specialized host preference. Despite the strong association between host and parasite, Ferreira et al. [46] reported instances of P. juxtanucleare infecting passerine birds. Given the pathogenic nature of this species, such spillover events are ecologically significant and may lead to increased mortality in wild bird populations.

Additionally, we detected lineage PX204195 in N. nycticorax individuals. Morphologically, this haplotype has not yet been characterized, nor have other sequences clustered within the same clade. These findings indicate the presence of a previously undescribed Plasmodium species or a lineage of a known morphospecies that has not yet been linked to molecular data. It is worth noting that only about half of all Plasmodium morphospecies are currently associated with genetic lineages [3].

In our study, haplotype PX146775 was recorded from A. cunicularia and showed 99.58% identity with H. noctuae (GenBank accession: ON932226). An individual of A. clamator was infected with sequence PX146776, which exhibited 98.74% identity with the H. syrnii sequence (GenBank accession: KJ575554). Phylogenetically, both sequences clustered within the clade represented by H. syrnii and H. noctuae, suggesting that despite the absence of morphological data, the parasites likely belong to this species complex.

Historically, more than ten Haemoproteus species infecting Strigiformes have been described [47]. To “clarify this chaotic situation,” Bishop and Bennett [47] redescribed H. syrnii, H. noctuae, and 11 other Haemoproteus species that infect owls, highlighting the taxonomic confusion within this group. Subsequent studies synonymized many of these species under H. syrnii and H. noctuae due to their high morphological similarity [1,5], resulting in the formation of a species complex. The first molecular sequence of H. syrnii was obtained in 2006, which matched the corresponding morphospecies [3], providing a genetic reference for this taxonomically complex group.

Approximately 100 years after its original description, Karadjian et al. [48] reopened the taxonomic discussion of H. syrnii and other Haemoproteus parasites that can infect owls. The subsequent description of H. ilanpapernai [28], associated with sequence DQ451424 (lineage STSEL01), suggested a possibly greater diversity of species infecting Strigiformes beyond H. syrnii and H. noctuae. Currently, the lineages OTSCO05, STAL02, and CULKIB01 (with respective GenBank accession numbers: KJ451480, KF279523, and KP794611) are commonly used as molecular barcodes for identifying H. syrnii [5].

Our study also reported, for the first time, the occurrence of a Haemoproteus parasite that infects Tyto furcata. The gametocytes observed in blood smears from this host exhibited morphological characteristics distinct from those of H. syrnii and H. noctuae. Notably, the parasite found in our study was shorter in length and contained fewer malarial pigments in the cytoplasm than the two well-characterized species. The gametocytes displace the erythrocyte nucleus without completely encircling it, which distinguishes this parasite from H. noctuae. Furthermore, immature gametocytes lacked volutin granules, a feature that Mayer [49] originally noted as prominent in H. syrnii. H. ilanpapernai gametocytes are smaller than those observed in T. furcata and do not displace the erythrocyte nucleus.

The sequence recovered from T. furcata corresponded to a new lineage, PX146774, which exhibited more than 2.72% genetic divergence compared to sequences attributed to H. syrnii, 2.52% to H. noctuae, and 2.22% compared to H. ilanpapernai. Furthermore, phylogenetic analyses showed that this new lineage of H. ilanpapernai formed a distinct clade separate from the haplotypes of H. syrnii and H. noctuae. Barino et al. [50] conducted a phylogenetic study using different sequences identified as H. syrnii and observed divergence among these lineages, leading to their classification into distinct clades and revealing the paraphyly of the species. Although they did not identify significant morphological differences between the recovered parasites and H. syrnii, they suggested the possible presence of a cryptic species. Giorgiadis et al. [51] evaluated captive Strigiformes in France and identified three haplotypes infecting these birds, corresponding to two distinct morphospecies. Haplotypes A and C were similar to H. syrnii, whereas haplotype B represented a morphologically and genetically distinct species unrelated to other Haemoproteus parasites typically found in Strigiformes.

Our phylogenetic analyses corroborated that the different Haemoproteus morphospecies infecting owl clusters form separate clades, as evidenced by the haplotypes of H. syrnii, H. noctuae, and H. ilanpapernai. Parasites infecting Strigiformes may have a complex history, and recent data have indicated a greater diversity of species than the traditionally recognized H. syrnii and H. noctuae. Although our data do not support the presence of a new species, they do indicate that the differences among Haemoproteus species infecting Strigiformes warrant further investigation. Haemoproteus parasites are classified, based on vector transmission, into two subgenera: Parahamoproteus and Haemoproteus [5]. In general, owls are nocturnal birds, and this could influence the invertebrate host to which these birds are exposed [52]. Due to that, the vectors for those parasites from owls may be distinct from those that infect diurnal animals.

Another finding was the report of a new lineage infecting P. picazuro, which showed 98.74% sequence identity to H. columbae (GenBank accession: LC606013). We could not perform a morphological evaluation. Despite the genetic differences between our haplotype and the sequences available in the database, sequence PX146778 clustered with H. columbae in the phylogenetic analysis. H. columbae was originally described by Kruse [53] and was previously believed to exclusively infect the domestic pigeon, Columba livia [54]. However, subsequent studies have demonstrated that this species can infect several Columbiformes [1,55]. As there are no previous records of P. picazuro infected by H. columbae or any other haemosporidian parasite, future studies should investigate this bird as a potential new host for the parasite.

We also recovered a sequence of Haemoproteus sp., identified as PX146777, which showed 100% identity with the lineage JX546141, as previously reported by Villar et al. [56]. In both studies, the haplotype was recovered from M. americana. Phylogenetic analysis revealed that this haplotype formed a clade with H. catharti and H. pulcher. Genetically, the PX146777 sequence exhibited 2.53% and 5.47% divergence from H. catharti and H. pulcher, respectively. This level of divergence indicates that the sequence from M. americana represents a new species. However, it was not possible to establish a link between the PX146777 lineage and the parasite morphology. Phylogenetically, these lineages clustered in a distinct subclade closely related to Hemocystidium and Plasmodium parasites. Studying the morphospecies and lineages of this clade is important for understanding the evolutionary relationships among haemosporidians.

5. Conclusions

Non-passerine birds exhibit remarkable diversity in avian haemosporidians. However, due to the inherent challenges associated with sampling these hosts, both morphological and genetic data regarding hemosporidian parasites remain limited. It is likely that many undescribed species within the genera Plasmodium and Haemoproteus exist, as suggested by the identification of the PX146774 lineage in T. furcata. Consequently, these avian groups represent significant targets for future research aimed at uncovering the evolutionary history of haemosporidians and their host–parasite interactions. Our study introduces new lineages and provides important insights into the biodiversity of hemosporidian parasites, further highlighting the significance of non-passerine birds in advancing this field.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/pathogens14121286/s1, Figure S1: Plates containing parasites from different hosts. Plasmodium paranucleophilum (lineage CPCT57) from a Roadside Hawk (Rupornis magnirostris), (a): trophozoite; (b,c): meront; (d): gametocyte. Plasmodium sp. (lineage CETASLO-R0263) from a Black-crowned Night Heron (Nycticorax nycticorax); (e,f): trophozoites; (g): microgametocytes; (h): microgametocytes. Haemoproteus syrnii (lineage ASICLAS-1682) was isolated from the blood smear of the Striped Owl (Asio clamator). (i,j): macrogametocytes. (k,l): microgametocytes. The arrows indicate the different parasitic forms inside the red blood cells. Scale bar = 10 μm.

Author Contributions

M.M.H. and L.G.M.A. contributed equally and shared first authorship. Conceptualization, M.M.H. and L.G.M.A. Methodology, M.M.H., L.G.M.A., M.N.A.R., V.L.d.B.S., B.M.R., R.H.d.S.F., S.H.R.C., É.M.B. and R.d.C.P.; Formal analysis, M.M.H., L.G.M.A., M.N.A.R., V.L.d.B.S., B.M.R., R.H.d.S.F., S.H.R.C., É.M.B. and R.d.C.P.; Investigation, M.M.H. and L.G.M.A.; Data curation, M.M.H., L.G.M.A., É.M.B. and R.d.C.P.; Writing—original draft, M.M.H., L.G.M.A., É.M.B. and R.d.C.P.; Writing—review & editing, M.M.H., L.G.M.A., É.M.B. and R.d.C.P.; Supervision, É.M.B. and R.d.C.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by CNPq (Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico) (310002/2022-2 and 310407/2023-0).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The work was approved by the Ethics Committee—Use of Animals (CEUA)—UFMT, protocol number 23108.035844/2021-10 and approval date: 29 October 2021; and the Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade (protocol number 79317-1; approval date: 25 October 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The sequences assemblies were deposited at GenBank repository https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/, accessed on 13 September 2024.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Valkiūnas, G. Avian Malaria Parasites and Other Haemosporidia; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, C.T.; LaPointe, D.A. Introduced avian diseases, climate change, and the future of Hawaiian honeycreepers. J. Avian Med. Surg. 2009, 23, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fecchio, A.; Chagas, C.R.; Bell, J.A.; Kirchgatter, K. Evolutionary ecology, taxonomy, and systematics of avian malaria and related parasites. Acta Trop. 2020, 204, 105364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valkiūnas, G.; Iezhova, T.A. Keys to the avian malaria parasites. Malar. J. 2018, 17, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valkiūnas, G.; Iezhova, T.A. Keys to the avian Haemoproteus parasites (Haemosporida, Haemoproteidae). Malar. J. 2022, 21, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bensch, S.; Hellgren, O.; Pérez-Tris, J. MalAvi: A public database of malaria parasites and related haemosporidians in avian hosts based on mitochondrial cytochrome b lineages. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2009, 9, 1353–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, N.J.; Clegg, S.M.; Lima, M.R. A review of global diversity in avian haemosporidians (Plasmodium and Haemoproteus: Haemosporida): New insights from molecular data. Int. J. Parasitol. 2014, 44, 329–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacheco, J.F.; Silveira, L.F.; Aleixo, A.; Agne, C.E.; Bencke, G.A.; Bravo, G.A.; Brito, G.R.R.; Cohn-Haft, M.; Maurício, G.N.; Naka, L.N.; et al. Annotated checklist of the birds of Brazil by the Brazilian Ornithological Records Committee—Second edition. Ornithol. Res. 2021, 29, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, G.; Higa, T.C.S.; Maitelli, G.T.; Oliveira, A.U.; Vilarinho Neto, C.S.; Leite, C.M.C.; Maitelli, G.T.; Ross, J.; Schwenk, L.M.; Araújo Neto, M.D.; et al. Geografia de Mato Grosso; Entrelinhas Editora: Cuiabá, Brazil, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Durrant, K.L.; Beadell, J.S.; Ishtiaq, F.; Graves, G.R.; Olson, S.L.; Gering, E.; Peirce, M.A.; Milensky, C.M.; Schmidt, B.K.; Gebhard, C.; et al. Avian hematozoa in South America: A comparison of temperate and tropical zones. Ornithol. Monogr. 2006, 60, 98–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klink, C.A.; Machado, R.B. Conservation of the Brazilian cerrado. Conserv. Biol. 2005, 19, 707–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvares, C.A.; Stape, J.L.; Sentelhas, P.C.; Gonçalves, J.D.M.; Sparovek, G. Köppen’s climate classification map for Brazil. Meteorol. Z. 2013, 22, 711–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junk, W.J.; Da Cunha, C.N.; Wantzen, K.M.; Petermann, P.; Strüssmann, C.; Marques, M.I.; Adis, J. Biodiversity and its conservation in the Pantanal of Mato Grosso, Brazil. Aquat. Sci. 2006, 68, 278–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, P.S.; Marquis, R.J. The Cerrado of Brazil: Ecology and Natural History of a Neotropical Savanna; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld, G. Corante pancrômico para hematologia e citologia clínica. Nova combinação dos componentes do May-Grunwald e do Giemsa num só corante de emprego rápido. Mem. Inst. Butantan. 1974, 20, 329–335. [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey, R.D., Jr.; Fedynich, A.M.; Pence, D.B. Quantification of hematozoa in blood smears. J. Wildl. Dis. 1987, 23, 558–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambrook, J.; Russel, D. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, 3rd ed.; Cold Spring Laboratory Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Fallon, S.M.; Ricklefs, R.E.; Swanson, B.L.; Bermingham, E. Detecting avian malaria: An improved polymerase chain reaction diagnostic. J. Parasitol. 2003, 89, 1044–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roos, F.L.; Belo, N.O.; Silveira, P.; Braga, E.M. Prevalence and diversity of avian malaria parasites in migratory Black Skimmers (Rynchops niger, Laridae, Charadriiformes) from the Brazilian Amazon Basin. Parasitol. Res. 2015, 114, 3903–3911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hellgren, O.; Waldenström, J.; Bensch, S. A new PCR assay for simultaneous studies of Leucocytozoon, Plasmodium, and Haemoproteus from avian blood. J. Parasitol. 2004, 90, 797–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanger, F.; Nicklen, S.; Coulson, A.R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1977, 74, 5463–5467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bensch, S.; Péarez-Tris, J.; Waldenströum, J.; Hellgren, O. Linkage between nuclear and mitochondrial DNA sequences in avian malaria parasites: Multiple cases of cryptic speciation? Evolution 2004, 58, 1617–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minh, B.Q.; Trifinopoulos, J.; Schrempf, D.; Schmidt, H.A.; Lanfear, R. IQ-TREE Version 2.0: Tutorials and Manual. Phylogenomic Software by Maximum Likelihood. 2019. Available online: http://www.iqtree.org (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Ronquist, F.; Huelsenbeck, J.P. MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics 2003, 19, 1572–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, L.M.D.C.; Pereira, P.H.O.; da Rocha Vilela, D.A.; Landau, I.; Pacheco, M.A.; Escalante, A.A.; Ferreira, F.C., Jr.; Braga, É.M. Leucocytozoon cariamae n. sp. and Haemoproteus pulcher coinfection in Cariama cristata (Aves: Cariamiformes): First mitochondrial genome analysis and morphological description of a leucocytozoid in Brazil. Parasitology 2023, 150, 1296–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pornpanom, P.; Chagas, C.R.F.; Lertwatcharasarakul, P.; Kasorndorkbua, C.; Valkiūnas, G.; Salakij, C. Molecular prevalence and phylogenetic relationship of Haemoproteus and Plasmodium parasites of owls in Thailand: Data from a rehabilitation centre. Int. J. Parasitol. Parasites Wildl. 2019, 9, 248–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karadjian, G.; Martinsen, E.; Duval, L.; Chavatte, J.M.; Landau, I. Haemoproteus ilanpapernai n. sp. (Apicomplexa, Haemoproteidae) in Strix seloputo from Singapore: Morphological description and reassignment of molecular data. Parasite 2014, 21, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukhin, A.; Palinauskas, V.; Platonova, E.; Kobylkov, D.; Vakoliuk, I.; Valkiūnas, G. The strategy to survive primary malaria infection: An experimental study on behavioral changes in parasitized birds. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0159216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chagas, C.R.F.; Guimarães, L.d.O.; Monteiro, E.F.; Valkiūnas, G.; Katayama, M.V.; Santos, S.V.; Guida, F.J.V.; Simões, R.F.; Kirchgatter, K. Hemosporidian parasites of free-living birds in the São Paulo Zoo, Brazil. Parasitol. Res. 2016, 115, 1443–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chagas, C.R.F.; Valkiūnas, G.; de Oliveira Guimarães, L.; Monteiro, E.F.; Guida, F.J.V.; Simões, R.F.; Rodrigues, P.T.; de Albuquerque, L.E.J.; Kirchgatter, K. Diversity and distribution of avian malaria and related haemosporidian parasites in captive birds from a Brazilian megalopolis. Malar. J. 2017, 16, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belo, N.O.; Passos, L.F.; Júnior, L.M.C.; Goulart, C.E.; Sherlock, T.M.; Braga, E.M. Avian malaria in captive psittacine birds: Detection by microscopy and 18S rRNA gene amplification. Prev. Vet. Med. 2009, 88, 220–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morel, A.P.; Webster, A.; Prusch, F.; Anicet, M.; Marsicano, G.; Trainini, G.; Stocker, J.; Giani, D.; Bandarra, P.M.; da Rocha, M.I.S.; et al. Molecular detection and phylogenetic relationship of Haemosporida parasites in free-ranging wild raptors from Brazil. Vet. Parasitol. Reg. Stud. Rep. 2021, 23, 100521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanstreels, R.E.T.; Kolesnikovas, C.K.; Sandri, S.; Silveira, P.; Belo, N.O.; Ferreira, F.C., Jr.; Epiphanio, S.; Steindel, M.; Braga, E.M.; Catao-Dias, J.L. Outbreak of avian malaria associated to multiple species of Plasmodium in magellanic penguins undergoing rehabilitation in southern Brazil. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e94994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjos, C.C.; Chagas, C.R.; Fecchio, A.; Schunck, F.; Costa-Nascimento, M.J.; Monteiro, E.F.; Mathias, B.S.; Bell, J.A.; Guimarães, L.O.; Comiche, K.J.M.; et al. Avian malaria and related parasites from resident and migratory birds in the Brazilian Atlantic Forest, with description of a new Haemoproteus species. Pathogens 2021, 10, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Available online: https://www.iucnredlist.org/ (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Marzal, A.; Magallanes, S.; Salas-Rengifo, T.; Muriel, J.; Navarro, C.; Vecco, D.; Guerra-Saldaña, C.; Mendo, L.; Paredes, V.; González-Blázquez, M.; et al. Prevalence and diversity of avian malaria parasites in illegally traded white-winged parakeets in Peruvian Amazonas. Anim. Conserv. 2024, 27, 364–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Catedral, L.; Brunton, D.; Stidworthy, M.F.; Elsheikha, H.M.; Pennycott, T.; Schulze, C.; Braun, M.; Wink, M.; Gerlach, H.; Pendl, H.; et al. Haemoproteus minutus is highly virulent for Australasian and South American parrots. Parasites Vectors 2019, 12, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valkiūnas, G.; Pendl, H.; Olias, P. New Haemoproteus parasite of parrots, with remarks on the virulence of haemoproteids in naive avian hosts. Acta Trop. 2017, 176, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warner, R.E. The role of introduced diseases in the extinction of the endemic Hawaiian avifauna. Condor 1968, 70, 101–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collar, N.; Boesman, P.F.D.; Sharpe, C.J. Red-and-green Macaw (Ara chloropterus), version 1.0. In Birds of the World; del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A., de Juana, E., Eds.; Cornell Lab of Ornithology: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collar, N.; Boesman, P.F.D.; Sharpe, C.J. White-eyed Parakeet (Psittacara leucophthalmus), version 1.0. In Birds of the World; del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A., de Juana, E., Eds.; Cornell Lab of Ornithology: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Mercado, A.; Asmüssen, M.; Rodríguez, J.P.; Moran, L.; Cardozo-Urdaneta, A.; Morales, L.I. Illegal trade of the Psittacidae in Venezuela. Oryx 2020, 54, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, K.; McGowan, P. On the current status of Indian peafowl Pavo cristatus (Aves: Galliformes: Phasianidae): Keeping the common species common. J. Threat. Taxa 2009, 1, 106–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tostes, R.; Dias, R.J.P.; Martinele, I.; Senra, M.V.X.; D’Agosto, M.; Massard, C.L. Multidisciplinary re-description of Plasmodium (Novyella) paranucleophilum in Brazilian wild birds of the Atlantic Forest kept in captivity. Parasitol. Res. 2017, 116, 1887–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, F.C., Jr.; de Angeli Dutra, D.; Silveira, P.; Pacheco, R.C.; Witter, R.; de Souza Ramos, D.G.; Pacheco, M.A.; Escalante, A.A.; Braga, É.M. A new pathogen spillover from domestic to wild animals: Plasmodium juxtanucleare infects free-living passerines in Brazil. Parasitology 2018, 145, 1949–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, M.A.; Bennett, G.F. The haemoproteids of the avian order Strigiformes. Can. J. Zool. 1989, 67, 2676–2684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadjian, G.; Puech, M.P.; Duval, L.; Chavatte, J.M.; Snounou, G.; Landau, I. Haemoproteus syrnii in Strix aluco from France: Morphology, stages of sporogony in a hippoboscid fly, molecular characterization and discussion on the identification of Haemoproteus species. Parasite 2013, 20, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, M.A. Über sein Entwicklung von Halteridium. Arch. Fur Schiffs Und Tropenhygiene 1910, 14, 197–202. [Google Scholar]

- Barino, G.T.M.; Rossi, M.F.; De Oliveira, L.; Reis, J.L., Jr.; D’Agosto, M.; Dias, R.J.P. Haemoproteus syrnii (Haemosporida: Haemoproteidae) in owls from Brazil: Morphological and molecular characterization, potential cryptic species, and exo-erythrocytic stages. Parasitol. Res. 2021, 120, 243–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giorgiadis, M.; Guillot, J.; Duval, L.; Landau, I.; Quintard, B. Haemosporidian parasites from captive Strigiformes in France. Parasitol. Res. 2020, 119, 2975–2981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bukauskaitė, D.; Žiegytė, R.; Palinauskas, V.; Iezhova, T.A.; Dimitrov, D.; Ilgūnas, M.; Bernotienė, R.; Markovet, M.Y.; Valkiūnas, G. Biting midges (Culicoides, Diptera) transmit Haemoproteus parasites of owls: Evidence from sporogony and molecular phylogeny. Parasites Vectors 2015, 8, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruse, W. Ueber blutparasiten. Arch. Für Pathol. Anat. Und Physiol. Und Für Klin. Med. 1890, 120, 541–560. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, J.R. Epizootiology of some haematozoic protozoa of English birds. J. Nat. Hist. 1975, 9, 601–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adriano, E.A.; Cordeiro, N.S. Prevalence and intensity of Haemoproteus columbae in three species of wild doves from Brazil. Mem. Do Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 2001, 96, 175–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villar, C.M.; Bryan, A.L., Jr.; Lance, S.L.; Braga, É.M.; Congrains, C.; Del Lama, S.N. Blood parasites in nestlings of wood stork populations from three regions of the American continent. J. Parasitol. 2013, 99, 522–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).