One Health Investigation of a Household Salmonella Thompson Outbreak in Italy: Genomic and Epidemiological Characterization of an Emerging Serotype

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Microbiological Methods for Bacterial Identification and Serotyping

2.1.1. Animals Sample Collection

2.1.2. Human Sample Collection

2.1.3. Microbiological Methods for Salmonella Identification

2.1.4. Serotyping

2.1.5. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (AST)

2.2. Data Collection of Epidemiological Investigation

2.3. Whole-Genome Sequencing and In Silico Analysis

3. Results

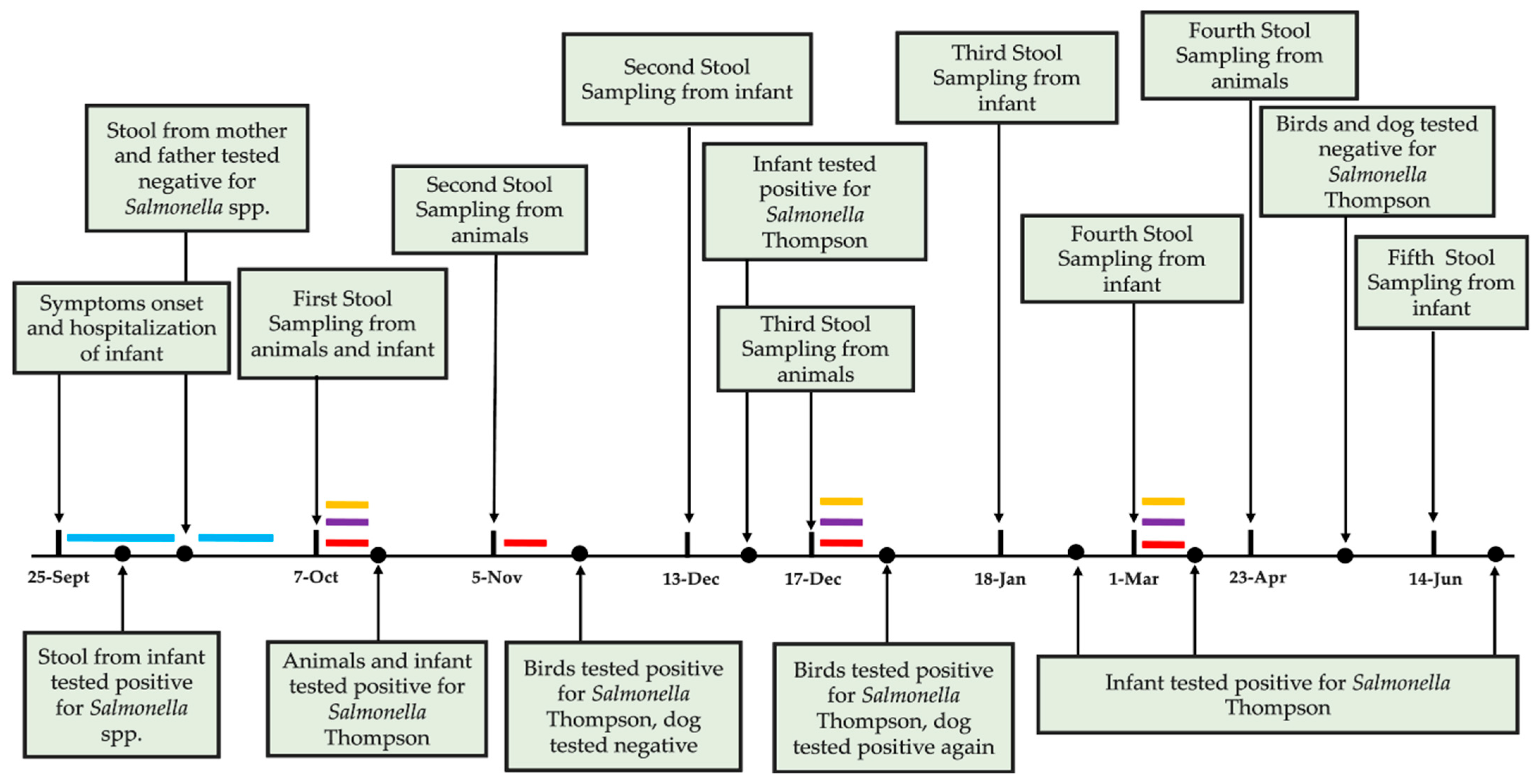

3.1. Case Presentation

3.2. Microbiological Analysis and Strains Characterization

3.3. AST

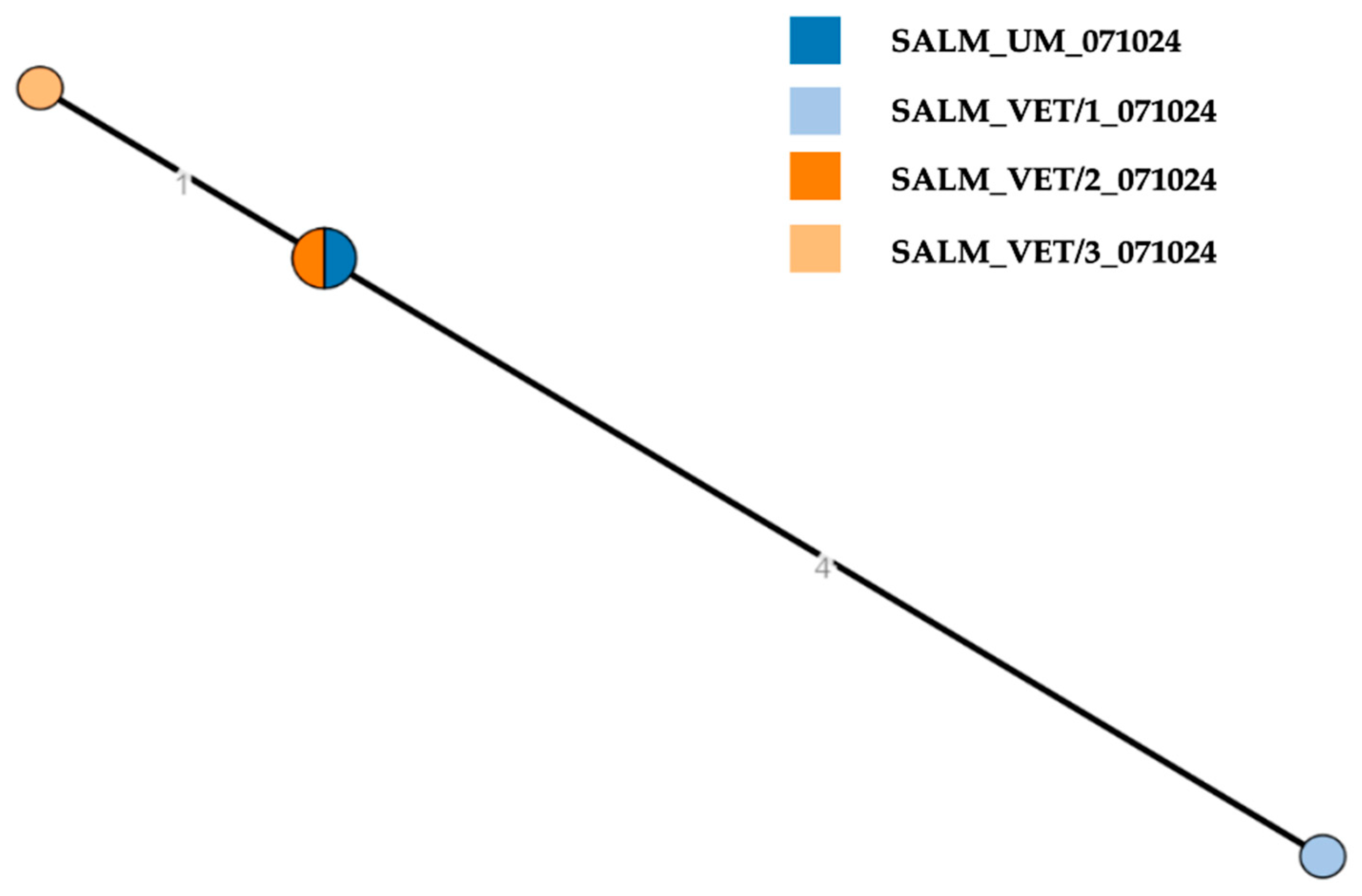

3.4. Whole-Genome Sequencing and In Silico Analysis

3.5. Genetic Basis of AMR/Disinfectant Resistance and Plasmid Replicon Typing

3.6. SPIs and Virulence Genes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WGS | Whole-Genome Sequencing |

| NCBI | National Center for Biotechnology Information |

| IZSLT | Istituto Zooprofilattico Sperimentale di Lazio e Toscana |

| UOT | Territorial Operative Unit |

| BPW | Buffered Peptone Water |

| MSRV | Semi-solid Rappaport-Vassiliadis Agar |

| XLD | Xylose-Lysine-Desoxycholate Agar |

| CRRLm | Regional Reference Center for Listeria monocytogenes |

| CREP | Regional Reference Center |

| AST | Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing |

| NRL-AR | National Reference Laboratory for Antimicrobial Resistance |

| MIC | Minimum Inhibitory Concentration |

| SRA | Sequence Read Archive |

| cgMLST | Core genome Multilocus Sequence Typing |

| MLST | Multilocus Sequence Typing |

| SPIs | Salmonella Pathogenicity Islands |

| CGE | Center for Genomic Epidemiology |

| VF | Virulence factors |

| AMR | Antimicrobial resistance |

| ST | Sequence Type |

| CC | Clonal complex |

| cgST | Core genome sequence type |

| MST | Minimum spanning tree |

| NCPs | National Control Programmes |

| ENTER-NET | Enteric Pathogen Network |

| MDR | Multidrug resistance |

References

- Zizza, A.; Fallucca, A.; Guido, M.; Restivo, V.; Roveta, M.; Trucchi, C. Foodborne Infections and Salmonella: Current Primary Prevention Tools and Future Perspectives. Vaccines 2024, 13, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA (European Food Safety Authority); ECDC (European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control). The European Union One Health 2023 Zoonoses report. EFSA J. 2024, 22, e9106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nygård, K.; Lassen, J.; Vold, L.; Andersson, Y.; Fisher, I.; Löfdahl, S.; Threlfall, J.; Luzzi, I.; Peters, T.; Hampton, M.; et al. Outbreak of Salmonella Thompson Infections Linked to Imported Rucola Lettuce. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2008, 5, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levantesi, C.; Bonadonna, L.; Briancesco, R.; Grohmann, E.; Toze, S.; Tandoi, V. Salmonella in surface and drinking water: Occurrence and water-mediated transmission. Food Res. Int. 2012, 45, 587–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leati, M.; Zaccherini, A.; Ruocco, L.; D’Amato, S.; Busani, L.; Villa, L.; Barco, L.; Ricci, A.; Cibin, V. The challenging task to select Salmonella target serovars in poultry: The Italian point of view. Epidemiol. Infect. 2021, 149, e160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russini, V.; Corradini, C.; Rasile, E.; Terracciano, G.; Senese, M.; Bellagamba, F.; Amoruso, R.; Bottoni, F.; De Santis, P.; Bilei, S.; et al. A Familiar Outbreak of Monophasic Salmonella serovar Typhimurium (ST34) Involving Three Dogs and Their Owner’s Children. Pathogens 2022, 11, 1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Tela, I.; Peruzy, M.F.; D’Alessio, N.; Di Nocera, F.; Casalinuovo, F.; Carullo, M.R.; Cardinale, D.; Cristiano, D.; Capuano, F. Serotyping and evaluation of antimicrobial resistance of Salmonella strains detected in wildlife and natural environments in southern Italy. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frasson, I.; Bettanello, S.; De Canale, E.; Richter, S.N.; Palù, G. Serotype epidemiology and multidrug resistance patterns of Salmonella enterica infecting humans in Italy. Gut Pathog. 2016, 8, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaresma, P.F.; Martins-Duarte, E.S.; Soares Medeiros, L.C. Editorial: One Health Approach in Zoonosis: Strategies to control, diagnose and treat neglected diseases. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 10–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghai, R.R.; Wallace, R.M.; Kile, J.C.; Shoemaker, T.R.; Vieira, A.R.; Negron, M.E.; Shadomy, S.V.; Sinclair, J.R.; Goryoka, G.W.; Salyer, S.J.; et al. A generalizable one health framework for the control of zoonotic diseases. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 8588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Office of Epizootics; Biological Standards Commission; International Office of Epizootics; International Committee. Chapter 3.10.7 Salmonellosis. In Manual of Diagnostic Tests and Vaccines for Terrestrial Animals: Mammals, Birds, and Bees, 13th ed.; Office international des épizooties: Paris, France, 2022; p. 19. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 6579-1:2017 + Amendment 1:2020; Microbiology of the Food Chain—Horizontal Method for the Detection, Enumeration and Serotyping of Salmonella—Part 1: Detection of Salmonella spp. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020.

- Russini, V.; Corradini, C.; De Marchis, M.L.; Bogdanova, T.; Lovari, S.; De Santis, P.; Migliore, G.; Bilei, S.; Bossù, T. Foodborne Toxigenic Agents Investigated in Central Italy: An Overview of a Three-Year Experience (2018–2020). Toxins 2022, 14, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ISO/TR 6579-3:2014; Microbiology of the Food Chain—Horizontal Method for the Detection, Enumeration and Serotyping of Salmonella—Part 3: Guidelines for Serotyping of Salmonella spp. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- ISO 20776-1:2019; Susceptibility Testing of Infectious Agents and Evaluation of Performance of Antimicrobial Susceptibility Test devicespart 1: Broth Micro-Dilution Reference Method for Testing the in vitro Activity of Antimicrobial Agents Against Rapidly. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- Amore, G.; Beloeil, P.; Fierro, R.G.; Rizzi, V.; Stoicescu, A. Manual for reporting 2024 antimicrobial resistance data under Directive 2003/99/EC and Commission Implementing Decision (EU) 2020/1729. EFSA Support. Publ. 2025, 22, 9238E. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bene, A.F.; Russini, V.; Corradini, C.; Vita, S.; Pecchi, S.; De Marchis, M.L.; Terracciano, G.; Focardi, C.; Montemaggiori, A.; Zuffi, M.A.L.; et al. An extremely rare serovar of Salmonella enterica (Yopougon) discovered in a Western Whip Snake (Hierophis viridiflavus) from Montecristo Island, Italy: Case report and review. Arch. Microbiol. 2024, 206, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, M.; Machado, M.P.; Silva, D.N.; Rossi, M.; Moran-Gilad, J.; Santos, S.; Ramirez, M.; Carriço, J.A. chewBBACA: A complete suite for gene-by-gene schema creation and strain identification. Microb. Genomics 2018, 4, e000166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z.; Alikhan, N.-F.; Mohamed, K.; Fan, Y.; Achtman, M. The EnteroBase user’s guide, with case studies on Salmonella transmissions, Yersinia pestis phylogeny, and Escherichia core genomic diversity. Genome Res. 2020, 30, 138–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achtman, M.; Zhou, Z.; Alikhan, N.-F.; Tyne, W.; Parkhill, J.; Cormican, M.; Chiou, C.-S.; Torpdahl, M.; Litrup, E.; Prendergast, D.M.; et al. Genomic diversity of Salmonella enterica-The UoWUCC 10K genomes project. Wellcome Open Res. 2021, 5, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Alikhan, N.F.; Sergeant, M.J.; Luhmann, N.; Vaz, C.; Francisco, A.P.; Carriço, J.A.; Achtman, M. Grapetree: Visualization of core genomic relationships among 100,000 bacterial pathogens. Genome Res. 2018, 28, 1395–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, N.P.; Päuker, B.; Baxter, L.; Gupta, A.; Bunk, B.; Overmann, J.; Diricks, M.; Dreyer, V.; Niemann, S.; Holt, K.E.; et al. EnteroBase in 2025: Exploring the genomic epidemiology of bacterial pathogens. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D757–D762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggel, M.; Horlbog, J.; Nüesch-Inderbinen, M.; Chattaway, M.A.; Stephan, R. Epidemiological links and antimicrobial resistance of clinical Salmonella enterica ST198 isolates: A nationwide microbial population genomic study in Switzerland. Microb. Genom. 2022, 8, 000877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magnet, S.; Courvalin, P.; Lambert, T. Activation of the cryptic aac(6′)-Iy aminoglycoside resistance gene of Salmonella by a chromosomal deletion generating a transcriptional fusion. J. Bacteriol. 1999, 181, 6650–6655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.X.; Zhang, J.F.; Sun, Y.H.; Li, R.S.; Lin, X.L.; Yang, L.; Webber, M.A.; Jiang, H.X. Contribution of Different Mechanisms to Ciprofloxacin Resistance in Salmonella spp. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 663731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadomski, A.; Scribani, M.B.; Tallman, N.; Krupa, N.; Jenkins, P.; Wissow, L.S. Impact of pet dog or cat exposure during childhood on mental illness during adolescence: A cohort study. BMC Pediatr. 2022, 22, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boseret, G.; Losson, B.; Mainil, J.G.; Thiry, E.; Saegerman, C. Zoonoses in pet birds: Review and perspectives. Vet. Res. 2013, 44, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masud, R.I.; Jahan, R.; Bakhtiyar, Z.; Antor, T.H.; Dilruba, A. Role of ornamental birds in the transmission of zoonotic pathogen and AMR A growing public health concern. Ger. J. Microbiol. 2024, 4, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkhoraibi, C.; Blatchford, R.A.; Pitesky, M.E.; Mench, J.A. Backyard chickens in the United States: A survey of flock owners. Poult. Sci. 2014, 93, 2920–2931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentile, N.; Carrasquer, F.; Marco-Fuertes, A.; Marin, C. Backyard poultry: Exploring non-intensive production systems. Poult. Sci. 2024, 103, 103284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dróżdż, M.; Małaszczuk, M.; Paluch, E.; Pawlak, A. Zoonotic potential and prevalence of Salmonella serovars isolated from pets. Infect. Ecol. Epidemiol. 2021, 11, 1975530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Wang, X.; He, J.; Zhou, K.; Xie, M.; Ding, H. Serovar and sequence type distribution and phenotypic and genotypic antimicrobial resistance of Salmonella originating from pet animals in Chongqing, China. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e03542-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boneva-Marutsova, B.; Marutsov, P.; Geisler, M.L.; Zhelev, G. Salmonellosis Outbreak in a Rottweiler Kennel Associated with Raw Meat-Based Diets. Animals 2025, 15, 3196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Liu, F.; Li, H.; Li, M.; Hu, Y.; Li, F.; Xiao, J.; Dong, Y. Emergence and genomic characteristics of multi-drug-resistant Salmonella in pet turtles and children with diarrhoea. Microb. Genomics 2024, 10, 001164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomel, B.B. Emerging and Re-Emerging Zoonoses of Dogs and Cats. Animals 2014, 4, 434–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, W.; Lu, M.; Zhao, L.; Du, P.; Cui, S.; Liu, Y.; Tan, D.; Zeng, X.; Yang, B.; Li, R.; et al. Tracing the evolution: The rise of Salmonella Thompson co-resistant to clinically important antibiotics in China, 1997–2020. mSystems 2025, 10, 582–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, J.; Chen, C.; Wang, Y.; Chen, X.; Li, X.; Xu, F. Resistance and Pathogenicity of Salmonella Thompson Isolated from Incubation End of a Poultry Farm. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbediwi, M.; Tang, Y.; Yue, M. Genomic characterization of ESBL-producing Salmonella Thompson isolates harboring mcr-9 from dead chick embryos in China. Vet. Microbiol. 2023, 278, 109634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peruzy, M.F.; Murru, N.; Carullo, M.R.; La Tela, I.; Rippa, A.; Balestrieri, A.; Proroga, Y.T.R. Antibiotic-Resistant Salmonella Circulation in the Human Population in Campania Region (2010–2023). Antibiotics 2025, 14, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galán, J.E. Salmonella Interactions with Host Cells: Type III Secretion at Work. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2001, 17, 53–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bäumler, A.J.; Tsolis, R.M.; Heffron, F. The lpf fimbrial operon mediates adhesion of Salmonella typhimurium to murine Peyer’s patches. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 279–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorsey, C.W.; Laarakker, M.C.; Humphries, A.D.; Weening, E.H.; Bäumler, A.J. Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium MisL is an intestinal colonization factor that binds fibronectin. Mol. Microbiol. 2005, 57, 196–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sia, C.M.; Pearson, J.S.; Howden, B.P.; Williamson, D.A.; Ingle, D.J. Salmonella pathogenicity islands in the genomic era. Trends Microbiol. 2025, 33, 752–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingsley, R.A.; Humphries, A.D.; Weening, E.H.; De Zoete, M.R.; Winter, S.; Papaconstantinopoulou, A.; Dougan, G.; Bäumler, A.J. Molecular and phenotypic analysis of the CS54 island of Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium: Identification of intestinal colonization and persistence determinants. Infect. Immun. 2003, 71, 629–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghenghi, L.; Ferrini, R.; Vai, L.; Dionisi, A.M.; Filetici, E.; Scalfaro, C.; Luzzi, I. Salmonella Thompson: Episodio epidemico in una mensa scolastica (P6). In IV Workshop Nazionale Enter-Net Italia Sistema di Sorveglianza Delle Infezioni Enteriche—Diagnostica ed Epidemiologia Delle Zoonosi Trasmesse da Alimenti. Istituto Superiore di Sanità. Roma, 25–26 novembre 2004. Riassunti; Caprioli, A., Luzzi, I., Lana, S., Eds.; Istituto Superiore di Sanità: Rome, Italy, 2004; p. 26. [Google Scholar]

- Koutsoumanis, K.; Allende, A.; Alvarez-Ordóñez, A.; Bolton, D.; Bover-Cid, S.; Chemaly, M.; De Cesare, A.; Herman, L.; Hilbert, F.; Lindqvist, R.; et al. Salmonella control in poultry flocks and its public health impact. EFSA J. 2019, 17, e05596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zottola, T.; Montagnaro, S.; Magnapera, C.; Sasso, S.; De Martino, L.; Bragagnolo, A.; D’Amici, L.; Condoleo, R.; Pisanelli, G.; Iovane, G.; et al. Prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility of Salmonella in European wild boar (Sus scrofa); Latium Region—Italy. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2013, 36, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stella, S.; Tirloni, E.; Castelli, E.; Colombo, F.; Bernardi, C. Microbiological evaluation of carcasses of wild boar hunted in a hill area of northern Italy. J. Food Prot. 2018, 81, 1519–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Taranto, P.; Petruzzi, F.; Normanno, G.; Pedarra, C.; Occhiochiuso, G.; Faleo, S.; Didonna, A.; Galante, D.; Pace, L.; Rondinone, V.; et al. Prevalence and Antimicrobial Resistance of Salmonella Strains Isolated from Chicken Samples in Southern Italy. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eun, Y.; Jeong, H.; Kim, S.; Park, W.; Ahn, B.; Kim, D.; Kim, E.; Park, E.; Park, S.; Hwang, I.; et al. A large outbreak of Salmonella enterica serovar Thompson infections associated with chocolate cake in Busan, Korea. Epidemiol. Health 2019, 41, e2019002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, A.Q.; Dalen, A.; Bankers, L.; Matzinger, S.R.; Schwensohn, C.; Patel, K.; Hise, K.B.; Pereira, E.; Cripe, J.; Jervis, R.H. Multistate Outbreak of Salmonella Thompson Infections Linked to Seafood Exposure—United States, 2021. MMWR. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2023, 72, 513–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nahar, S.; Jeong, H.L.; Cho, A.J.; Park, J.H.; Han, S.; Kim, Y.; Park, S.H.; Ha, S. Do Efficacy of ficin and peroxyacetic acid against Salmonella enterica serovar Thompson biofilm on plastic, eggshell, and chicken skin. Food Microbiol. 2022, 104, 103997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM), The Netherlands; Iulietto, M.F.; Evers, E.G. Modelling and magnitude estimation of cross-contamination in the kitchen for quantitative microbiological risk assessment (QMRA). EFSA J. 2020, 18, e181106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilbert, F.; Smulders, F.J.M.; Chopra-Dewasthaly, R.; Paulsen, P. Salmonella in the wildlife-human interface. Food Res. Int. 2012, 45, 603–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sampling Date | Matrix | Species | Sample Type | Sampling Unit | Sample ID | Outcome | Serovar | NCBI Ac. No. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 October 2024 | Feces | Human | Individual | 1 | SALM_UM_071024 § | + | S. Thompson 6,7: k:1,5 O:7 (C1) | SAMN50810632 |

| Feces | Dog | Individual | 1 | SALM_VET/1_071024 § | + | S. Thompson 6,7: k:1,5 O:7 (C1) | SAMN50810633 | |

| Feces | Birds * | Pool n. 1 | 1 | SALM_VET/2_071024 § | + | S. Thompson 6,7: k:1,5 O:7 (C1) | SAMN50810634 | |

| Feces | Birds * | Pool n. 2 | 1 | SALM_VET/3_071024 § | + | S. Thompson 6,7: k:1,5 O:7 (C1) | SAMN50810635 | |

| 5 November 2024 | Feces | Dog | Individual | 1 | SALM_VET/1_051124 | − | n/a | n/a |

| Feces | Birds * | Pool n. 1 | 1 | SALM_VET/2_051124 | − | n/a | n/a | |

| Feces | Birds * | Pool n. 2 | 1 | SALM_VET/3_051124 | + | S. Thompson 6,7: k:1,5 O:7 (C1) | n/a | |

| 13 December 2024 | Feces | Human | Individual | 1 | SALM_UM_131224 | + | S. Thompson 6,7: k:1,5 O:7 (C1) | n/a |

| 17 December 2024 | Feces | Dog | Individual | 1 | SALM_VET/1_171224 | + | S. Thompson 6,7: k:1,5 O:7 (C1) | n/a |

| Feces | Birds * | Pool n. 1 | 1 | SALM_VET/2_171224 | - | n/a | n/a | |

| Feces | Birds * | Pool n. 2 | 1 | SALM_VET/3_171224 | + | S. Thompson 6,7: k:1,5 O:7 (C1) | n/a | |

| 18 January 2025 | Feces | Human | Individual | 1 | SALM_UM_180125 | + | S. Thompson 6,7: k:1,5 O:7 (C1) | n/a |

| 1 March 2025 | Feces | Human | Individual | 1 | SALM_UM_010325 | + | S. Thompson 6,7: k:1,5 O:7 (C1) | n/a |

| 23 April 2025 | Feces | Dog | Individual | 1 | SALM_VET/1_230425 | − | n/a | n/a |

| Feces | Birds * | Pool ^ | 1 | SALM_VET/2_230425 | − | n/a | n/a | |

| Feces | Cat | Individual | 1 | SALM_VET/3_230425 | − | n/a | n/a | |

| 14 June 2025 | Feces | Human | Individual | 1 | SALM_UM_140625 | + | S. Thompson 6,7: k:1,5 O:7 (C1) | n/a |

| SPIs | Isolate ID SALM_ UM_071024 | Isolate ID SALM_ VET/1_071024 | Isolate ID SALM_ VET/2_071024 | Isolate ID SALM_ VET/3_071024 | Virulence Genes | Contig |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPI-2, SPI-5, SP-14, Not_named (Acc.numb. JQ071613) | + | + * | + | + | sopA sopE2 steC sseJ steB sifB steA ssaU ssaT ssaS ssaR ssaQ ssaP ssaO ssaN ssaV ssaM ssaL ssaK ssaJ ssaI ssaH ssaG sseG sseF sscB sseE sseD sseC sscA sseB sseA ssaE ssaD ssaC spiC/ssaB sifA sopB/sigD ^ pipB ^ sopD2 ^ slrP ^, sspH2 §, csgC csgA csgB csgD csgE csgF csgG | 1 |

| SP-1, C63PI (SPI-1), SP-13 | + | + | + | + | pipB2, avrA orgC orgB orgA prgK prgJ prgI prgH sptP sicP sipA/sspA sipD sipC/sspC sipB/sspB sicA spaS spaR spaQ spaP spaO invJ invI invC invB invA invE invG invF invH sopD, mig-14 | 2 |

| SP-3 | + | + | + | + | lpfE, lpfD, lpfC, lpfB, lpfA, misL, mgtB, mgtC | 4 |

| CS54 (SPI-24) | + | + | + | + | sseL, shdA, sinH, ratB, shdA | 5 |

| SPI-5, SPI-14 | − | + | − | − | slrP sopD2 pipB sopB/sigD | 6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bivona, M.; De Bene, A.F.; Russini, V.; De Marchis, M.L.; Di Domenico, I.; Riccardi, F.; Senese, M.; Gasperetti, L.; Campeis, F.; Di Blasi, L.; et al. One Health Investigation of a Household Salmonella Thompson Outbreak in Italy: Genomic and Epidemiological Characterization of an Emerging Serotype. Pathogens 2025, 14, 1285. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121285

Bivona M, De Bene AF, Russini V, De Marchis ML, Di Domenico I, Riccardi F, Senese M, Gasperetti L, Campeis F, Di Blasi L, et al. One Health Investigation of a Household Salmonella Thompson Outbreak in Italy: Genomic and Epidemiological Characterization of an Emerging Serotype. Pathogens. 2025; 14(12):1285. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121285

Chicago/Turabian StyleBivona, Marta, Andrea Francesco De Bene, Valeria Russini, Maria Laura De Marchis, Ilaria Di Domenico, Francesca Riccardi, Matteo Senese, Laura Gasperetti, Francesca Campeis, Luca Di Blasi, and et al. 2025. "One Health Investigation of a Household Salmonella Thompson Outbreak in Italy: Genomic and Epidemiological Characterization of an Emerging Serotype" Pathogens 14, no. 12: 1285. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121285

APA StyleBivona, M., De Bene, A. F., Russini, V., De Marchis, M. L., Di Domenico, I., Riccardi, F., Senese, M., Gasperetti, L., Campeis, F., Di Blasi, L., Carfora, V., Middei, B., Cordaro, G., Adreani, G., Marconi, P., & Bossù, T. (2025). One Health Investigation of a Household Salmonella Thompson Outbreak in Italy: Genomic and Epidemiological Characterization of an Emerging Serotype. Pathogens, 14(12), 1285. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14121285