Abstract

Leishmania (L.) infantum infections in dogs can cause severe recurrent disease. The aim of this study was to investigate different parameters for early detection of disease relapses in L. infantum-infected dogs in Germany. Fifty-two dogs naturally infected with L. infantum were enrolled. During the one-year study period, all dogs remained outside of endemic areas and attended study appointments every three months, including physical examination, blood pressure measurement, complete blood count with differential, serum biochemistry with symmetrical dimethylarginine and C-reactive protein, complete urinalysis including urine protein-to-creatinine ratio, L. infantum PCR, and antibody ELISA. Disease relapse was defined as deterioration of clinical or laboratory parameters in dogs that had achieved complete or partial remission before. Univariable and multivariable Bayesian logistic regression were used to identify predictors of disease relapse. Lymphadenopathy (p < 0.01; OR = 6.93), seborrhea/hypotrichosis (p = 0.02; OR = 8.02), and proteinuria (p < 0.01; OR = 9.14) were significantly associated with upcoming disease relapses (n = 10; 9/52 dogs), while associations between higher antibody levels and upcoming disease relapses trended towards significance (p = 0.06; OR = 1.03). Different parameters are important for an early diagnosis of disease relapse in canine leishmaniosis and should thus be regularly assessed and interpreted accordingly in the monitoring of L. infantum-infected dogs.

1. Introduction

Canine leishmaniosis is the manifestation of Leishmania (L.) infantum infection in dogs and occurs endemically in different countries all over the world [1]. The endemicity of the disease is linked to the occurrence of phlebotomine sandflies, which serve as the protozoan parasites’ vector [2,3,4,5]. Manifestation of the disease is commonly linked to an exuberant humoral immune response to the intracellular pathogen, with an excessive production of non-protective antibodies [6,7,8,9]. Together with free Leishmania antigens, antibodies form circulating immune complexes. Tissue deposition of immune complexes is one of the main pathological mechanisms underlying signs of canine leishmaniosis, besides other inflammatory and immune-mediated reactions [10,11,12]. Various organ systems can be affected; therefore, a variety of clinical signs and/or laboratory alterations can emerge, even several years after infection [10,13,14]. Thus, close monitoring of infected dogs is considered essential for early recognition of new signs and implementation of appropriate countermeasures [15,16].

To relieve the signs of disease and reduce the parasitic burden, different therapeutic interventions are applied [17,18,19,20]. Commonly, the l leishmanistatic drug allopurinol is used, either alone or in combination with and/or following leishmanicidal treatment with miltefosine or meglumine antimoniate [15]. Since dogs serve as reservoir hosts for L. infantum, infections usually cannot be cleared [21,22,23,24], and the re-emergence of disease signs after an initial improvement in response to treatment is common [25,26].

Thus, disease relapses, i.e., their prevention, diagnosis, and treatment, are an important aspect in the management of canine leishmaniosis [27,28,29,30,31,32]. Nevertheless, studies on this topic are scarce. In endemic countries, it is often difficult to differentiate relapse from re- or superinfection. Therefore, studies on relapse in non-endemic countries are highly beneficial. Thus, the aim of this prospective longitudinal study, in which dogs were monitored over a one-year observation period with predefined follow-up appointments, was to evaluate various clinical and laboratory parameters of canine leishmaniosis for their use as predictors of disease relapses in L. infantum-infected dogs living in a non-endemic country.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This prospective longitudinal clinical study was authorized by the ethical committee of the Centre for Clinical Veterinary Medicine of the LMU Munich (Government of Upper Bavaria, reference number 244-06-12-2020) and was conducted between 2021 and 2023.

2.1.1. Enrollment

Prior to enrollment, the following inclusion criteria had to be fulfilled: (1) proof of L. infantum infection, diagnosed by the referring veterinarian, based on a positive PCR (at an external laboratory) or antibody ELISA or IFAT result (according to the respective laboratories’ cut-off values) (Supplementary Table S1); (2) indication of antileishmanial treatment [15]; (3) agreement of dog owners to attend study appointments every three months and not to take their dogs to endemic countries during the observation period. Dogs were excluded from enrollment in case of (1) systemic immunosuppressive treatment or domperidone, (2) severe concomitant disease, or (3) untreated Ehrlichia (E.) canis or Dirofilaria (D.) immitis co-infections.

Investigations at the time point of enrollment (study day 0) included a qualitative point-of-care (POC) test for E. canis, D. immitis, Borrelia burgdorferi, and Anaplasma phagocytophilum/platys (SNAP® 4Dx Plus, IDEXX Laboratories Inc., Westbrook, ME, USA) and an abdominal ultrasound screening to exclude (severe) concomitant diseases and untreated E. canis or D. immitis co-infections. The enrollment further included a physical examination, non-invasive blood pressure measurement, complete blood count, serum biochemistry including symmetric dimethylarginine (SDMA) and C-reactive protein (CRP), complete urinalysis including urine protein-to-creatinine ratio (UPC) L. infantum antibody ELISA, and quantitative PCR of conjunctival swabs. Conjunctival swab samples were collected from both eyes by rubbing a sterile cotton swab along the conjunctival surface.

During the study course, each dog received treatment according to its individual clinical signs. Antileishmanial treatment was applied in standard dosing regimens described in the current literature [15,21,33,34], including allopurinol at 10 mg/kg q12h PO (consideration of dose reduction in case of urinary tract adverse events (Supplementary Figure S1)) and, when indicated, miltefosine at 2 mg/kg q24h PO for 4 weeks or meglumine antimoniate at 100 mg/kg q24h SC for 4 weeks. A low-purine diet was recommended for the prevention of xanthine urolithiasis [33,35]. Supportive symptomatic treatment was applied as needed.

A total of 52 dogs infected with L. infantum were enrolled (Supplementary Table S1). The dogs were more often female (n = 32) than male (n = 20) and mixed breed (n = 36) than purebred (n = 16), with ages ranging between 11 months and 14 years. All dogs had a travel history or originated from an endemic country. Regarding their L. infantum infections prior to inclusion, the dogs either (1) never had severe signs of the disease (n = 17), (2) had achieved (n = 16) or had not (yet) achieved (n = 12) remission by treatment after previous disease manifestation, or (3) had signs of the disease but had not received treatment before (n = 7). At enrollment, 40 dogs presented with mild to moderate disease (LeishVet stage I (n = 33) or stage II (substage IIa: n = 6; substage IIb: n = 1)), whereas 12 dogs were classified as severely affected (LeishVet stage III (n = 9) or stage IV (n = 3)) [36].

2.1.2. Study Appointments

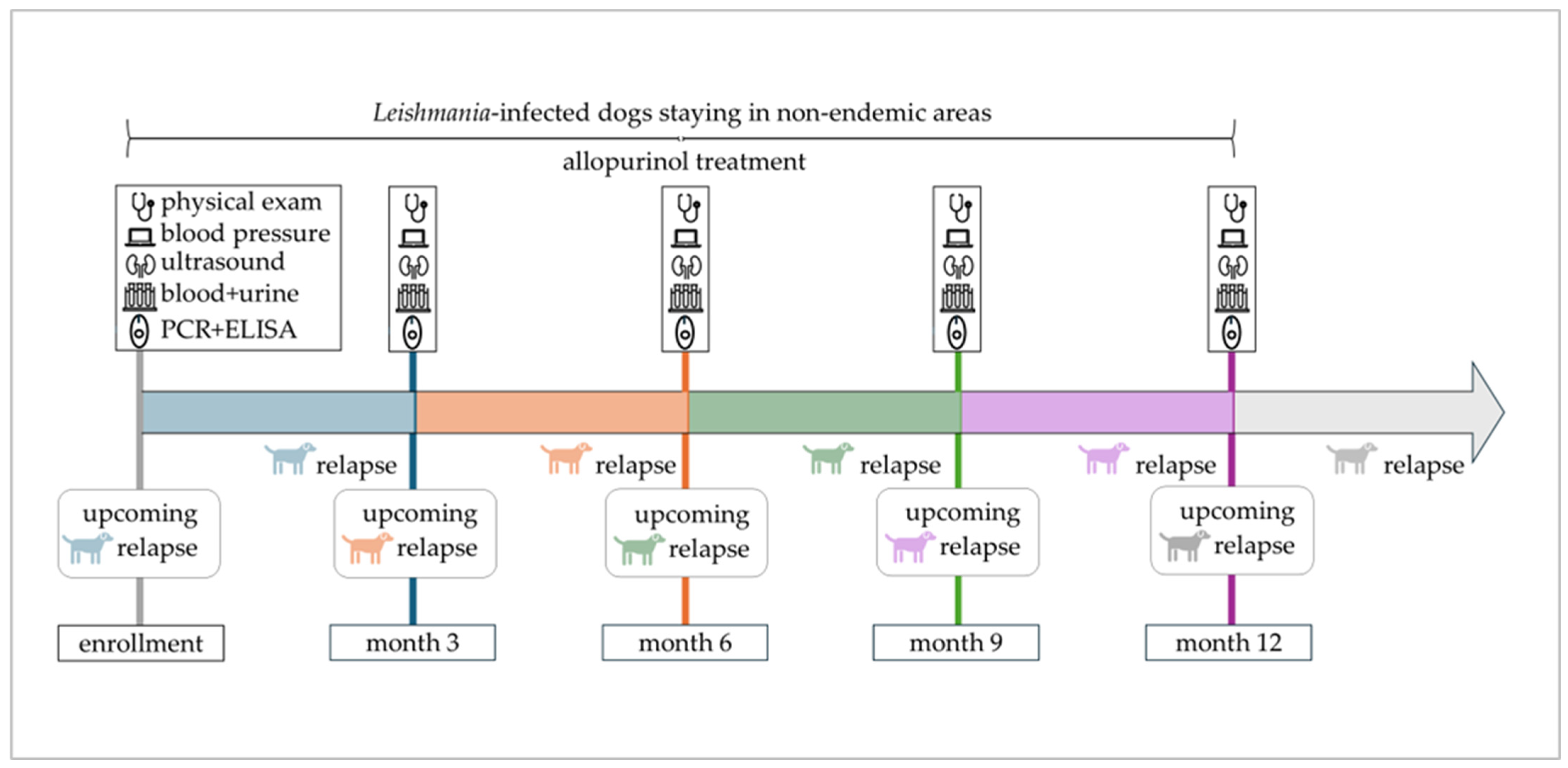

After enrollment, the one-year study period included four appointments at three-month intervals at the LMU Small Animal Clinic in Munich (Figure 1). Each appointment consisted of a thorough physical examination, non-invasive blood pressure measurement, ultrasound of the urinary tract, complete blood count, serum biochemistry including SDMA and CRP, complete urinalysis including UPC, L. infantum antibody ELISA, and quantitative PCR (as described for enrollment) of conjunctival swabs.

Figure 1.

Timeline of the one-year study period with scheduled study appointments. Enrolled dogs remained in non-endemic areas, were treated with allopurinol, and attended study appointments every three months. An upcoming relapse indicates the emergence of disease relapse within 3 months after a scheduled study appointment.

2.1.3. Laboratory Methods and Instruments Used

For every study appointment, hematological analysis was performed with an automated in-house analyzer (Sysmex XT-2000iV; Sysmex Corporation, Kobe, Japan, or ProCyte Dx, IDEXX Laboratories Inc., Westbrook, ME, USA). Urine specific gravity was determined by an optical refractometer, and urine dipstick analysis was performed using IDEXX UA test strips read by the IDEXX UA Analyzer (IDEXX Laboratories Inc., Westbrook, ME, USA). For urine sediment analysis, an automated in-house device was used (SediVue, IDEXX Laboratories Inc., Westbrook, ME, USA).

Blood biochemistry, UPC, L. infantum antibody, and PCR were evaluated in an external laboratory (IDEXX GmbH, Kornwestheim, Germany). Leishmania spp. DNA was detected by a validated real-time PCR (IDEXX Laboratories) targeting the glycoprotein gp63 gene as previously described [37]. The assay included quantitative PCR-positive and PCR-negative controls, negative extraction controls, a quantitative internal DNA quality control f (host 18S rRNA), a positive internal control (added to the lysis solution), and a monitoring control for environmental contamination [37]. For the sample shipment, which was performed on the day of sampling, cooled aliquots of urine and serum, as well as conjunctival swabs, were packed in an isolated container. Any surplus material was stored at −80 °C.

2.2. Disease Relapse

Disease relapse was defined as either (1) appearance of new clinical or clinicopathological abnormalities, or (2) reappearance of clinical or clinicopathological abnormalities that had been present but had been cleared, or (3) worsening of clinical or clinicopathological abnormalities that had been stable or had improved previously. This applied to dogs that achieved complete remission (restoration of all clinical and laboratory parameters) or partial remission (improvement but no complete restoration of all clinical and laboratory parameters) following previous therapeutic intervention. Differential diagnoses were ruled out whenever dogs presented with new or worsening signs. To identify predictors for disease relapse, clinical and laboratory parameters at the study appointment preceding the relapse within the following three months were considered (Figure 1). Accordingly, disease relapses observed at the first study appointment were not included in predictor analysis due to missing preceding data.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using R statistical software (version 4.3.1). All study appointments were treated as independent events. If dogs were withdrawn from the study before completion of the observation period, data obtained up to the time of exclusion were included in the analyses.

Associations between upcoming disease relapses and clinical signs, as well as laboratory alterations, were analyzed by univariable and multivariable logistic Bayesian regression. After univariable analysis, parameters with p-values < 0.2 were included in the corresponding multivariable model [38]. Model selection was performed by an automated model selection and multimodel inference (brute-force) approach using the R package “glmulti” [39,40]. Model performance was evaluated by the corrected Akaike Information Criterion (AICc); models with the lowest AICc were selected, and only the remaining predictors in the final multivariable models were analyzed. Statistical significance was defined as p ≤ 0.05, with 0.05 < p ≤ 0.1 indicating a trend towards significance.

3. Results

3.1. Study Course

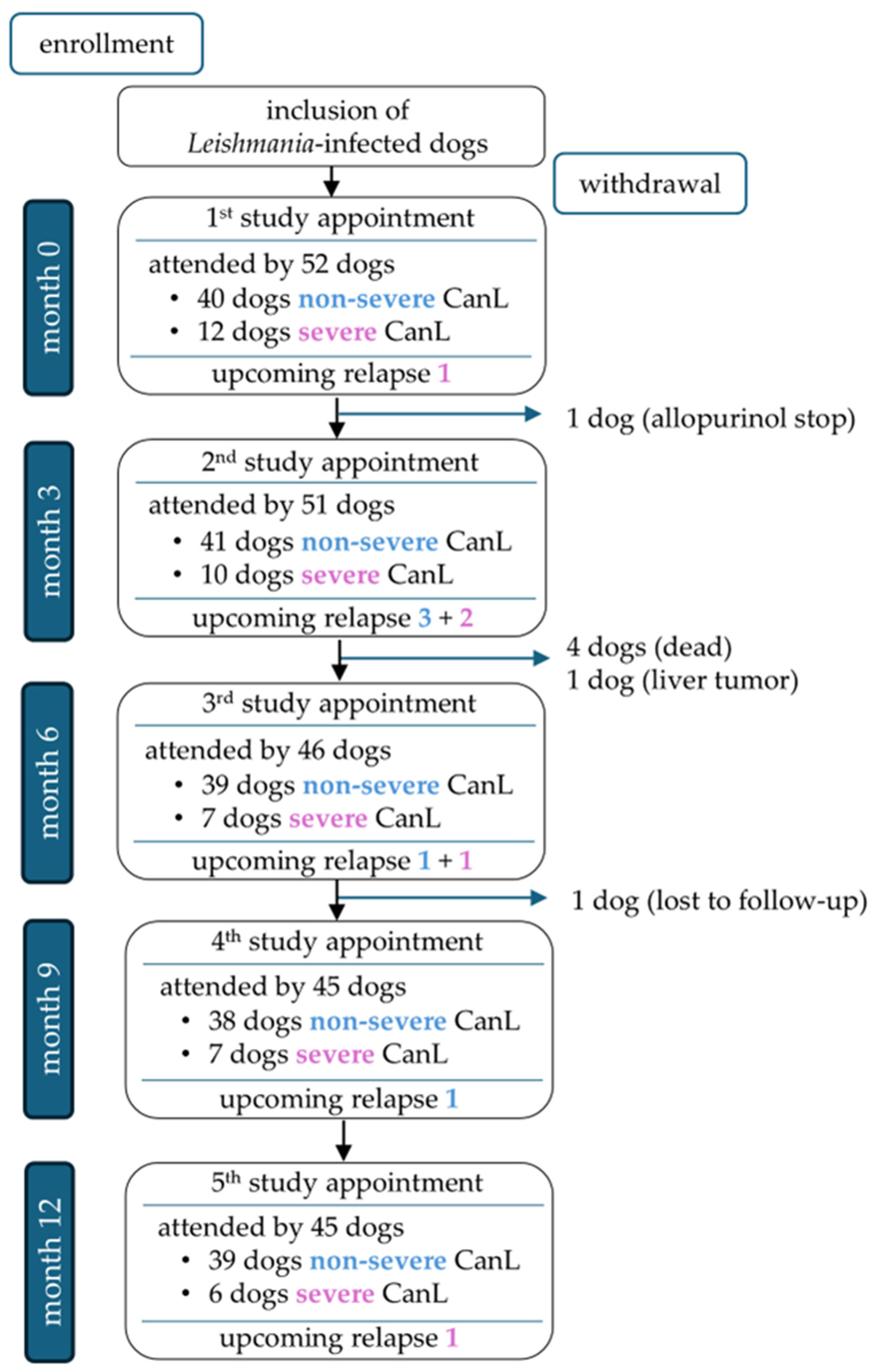

A total of 45/52 dogs completed the one-year study period (Figure 2). Seven of 52 dogs were unable to complete the study for the following reasons: One dog died during a disease relapse that was associated with severe non-regenerative anemia and azotemia and occurred approximately 4.5 months after an initial improvement following leishmanicidal and supportive symptomatic treatment. One dog was euthanized with progressive chronic kidney disease, and one dog was diagnosed with a liver tumor. Two dogs died acutely due to unclarified underlying causes. Another dog was withdrawn from the study due to discontinuation of allopurinol treatment, and one dog was lost to follow-up. Overall, 177 appointments were eligible for statistical analysis of relapse predictors; 10/177 study appointments of 9/52 dogs were followed by disease relapses after 1.5–3 (median 2.4) months (Supplementary Table S2 and Figure S2).

Figure 2.

Overview of dogs attending the study appointments at months 0, 3, 6, 9, and 12, divided into non-severe cases (blue font; LeishVet stages I–II) and severe cases (pink font; LeishVet stages III–IV) [33], including upcoming relapses per group.

3.2. Predictors of Disease Relapse

Various clinical and laboratory parameters were evaluated as predictors of emerging disease relapses (Table 1). Univariable logistic regression (UVA) of clinical signs identified lymphadenopathy (p < 0.01), seborrhea/hypotrichosis (p < 0.01), and skin ulcers (p = 0.04) as significant predictors of upcoming relapse. Based on a preselection threshold of p < 0.2, papules/nodules (p = 0.08) were also included in the multivariable model, whereas conjunctivitis/blepharitis (p = 0.44) was excluded from further analysis. In multivariable logistic regression, lymphadenopathy (OR = 6.93; 95% CI: 1.80–26.7; p < 0.01) and seborrhea/hypotrichosis (OR = 8.02; 95% CI: 1.43–44.9; p = 0.02) remained significant predictors. Specifically, patients with lymphadenopathy had 6.93-fold increased odds of upcoming relapse compared to those without. Similarly, patients with seborrhea/hypotrichosis had 8.02 times higher odds of upcoming relapse. Papules/nodules and skin ulcers were eliminated from the final model during automated model selection based on the corrected Akaike Information Criterion (AICc).

Table 1.

Univariable and multivariable logistic Bayesian regression of clinical and laboratory parameters as predictors of upcoming disease relapses in Leishmania-infected dogs in Germany.

In terms of laboratory alterations, UVA identified proteinuria (p < 0.01), Leishmania antibody levels (p = 0.05), and hypoalbuminemia (p = 0.05) as significant predictors of upcoming relapse. In addition, hyperproteinemia (p = 0.06), hyperglobulinemia (p = 0.07), monocytosis (p = 0.06), and non-regenerative anemia (p = 0.17) were included in the multivariable analysis (p < 0.2). Thrombocytopenia, neutropenia, lymphopenia, lymphocytosis, renal azotemia, and increased levels of SDMA and CRP were excluded from further analysis (p > 0.2). In multivariable logistic regression, proteinuria (OR = 9.14; 95% CI: 2.41–34.6; p < 0.01) remained the only significant predictor of upcoming relapse. Specifically, patients with proteinuria had 9.14-fold increased odds of upcoming relapse compared to those without. Associations between Leishmania antibody levels and upcoming relapse trended towards significance (OR = 1.03; 95% CI: 1.00–1.05; p = 0.06). Hypoalbuminemia, hyperproteinemia, hyperglobulinemia, monocytosis, and non-regenerative anemia were eliminated from the final model during automated model selection based on the corrected Akaike Information Criterion (AICc).

4. Discussion

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first prospective study investigating prognostic parameters for upcoming disease relapses in dogs with L. infantum infections in non-endemic countries. With a prevalence of 17% (9/52 dogs), the emergence of disease relapses evaluated in the present study population was comparable to a previous study in an endemic area, with approximately 20% of dogs experiencing relapse, although within a two-year period [26]. However, overall relapse rates vary widely in different previous studies and were reported to even exceed 70% [16], but the extent to which re- or superinfection contributes to worsening and relapse diagnosis in dogs in endemic areas remains unclear [14]. Nevertheless, it points to the relevance of a close monitoring of L. infantum-infected dogs and the need for long-term studies performed in non-endemic areas, without risk of re-exposure to the pathogen. To ensure timely therapeutic interventions and counteract an upcoming deterioration, a proper assessment of disease relapse is essential but lacks standardization [27]. According to a survey among 155 veterinarians in Portugal, the majority (approximately 60%) always considered the reappearance or worsening of clinical signs to establish a diagnosis of relapse, while only a minor percentage of veterinarians always considered laboratory parameters in this context [27]. The relevance of laboratory findings for relapse diagnosis was, however, emphasized by a recent retrospective study; besides higher total clinical scores, anemia, dysproteinemia, and high antibody titers (IFAT) were significantly associated with an increased risk of disease relapses in naturally infected dogs in Spain [41]. To account for the gradual disease progression, which is commonly observed rather than a sudden onset [14,42,43,44], the present study evaluated different clinical and laboratory parameters for their use as predictors of disease relapse. Despite the longitudinal study design over a one-year period, the number of dogs with relapse was relatively low (n = 9), which might have influenced statistical results.

With regard to the present study’s findings on clinical signs, dogs with lymphadenopathy were found to be significantly (approximately seven times) more likely to experience disease relapse in the following three months than dogs without. Indeed, lymphadenopathy was also identified as the earliest clinical sign emerging in experimentally infected dogs transitioning to overt disease [42,43], which, according to the findings of the present study, might also apply to disease relapse.

Although not pathognomonic for canine leishmaniosis, enlargement of lymph nodes is one of the most common clinical signs of canine leishmaniosis [45,46,47,48] and was even identified as a predictive factor for diagnosing the disease in 713 dogs examined as part of a cross-sectional study performed in a veterinary teaching hospital in Brazil [30]. Accordingly, lymphadenopathy was shown to be a clinical sign prompting suspicion of canine leishmaniosis among veterinarians in endemic countries [49]. Histopathologically, lymph node enlargement has been linked to indirect and direct responses to L. infantum infections. These included hyperplasia of lymphoid follicles related to the proliferation of antibody-producing B-cells [50,51] and/or enhanced proliferation of macrophages [50,52,53] and granulomatous inflammation, which is assumed to occur at sites of parasitic infections with a proliferation and/or infiltration of histiocytes, plasma cells, lymphocytes, and in some cases neutrophils and eosinophils [6,12]. Thus, it seems reasonable that disease relapse, which is assumed to result from enhanced parasite replication and/or a shift towards a Th2-predominated immune response [24,25,31,44], is reflected early in lymph node enlargement.

Besides lymphadenopathy, dogs presenting with seborrhea and/or hypotrichosis in the present study were found to have an approximately eight times higher likelihood of upcoming disease relapses than dogs without. In canine leishmaniosis, seborrhea is variably associated with hypotrichosis (to alopecia) and commonly attributable to exfoliative dermatitis [8], presumed to emerge through hematogenous spread of parasites [12,54,55]. Histopathologically, exfoliative dermatitis can be characterized by (interstitial, perivascular, nodular, or periadnexal) granulomatous inflammation including infiltrates of macrophages, lymphocytes, and plasma cells, accompanied by orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis of the epidermis and follicles [12,54,56,57,58]. Since this inflammatory pattern could also be observed in macroscopically non-lesioned skin of Leishmania-infected dogs [55,58,59], microscopic alterations might precede (or persist without) macroscopic lesions [55,56,58,60,61]. It could thus be assumed that in case of an emerging disease relapse, an uncontrolled parasite replication leads to dermal inflammation, the macroscopic manifestation of which might be an early indicator of the relapse-associated immunological shift towards a Th2-predominated immune response.

Notably, seborrhea and hypotrichosis/alopecia seem to already constitute a relevant parameter in the clinical monitoring of dogs suspected to be infected with Leishmania spp. At least in endemic European countries, exfoliation and alopecia were reported by veterinarians as signs suggestive of canine leishmaniosis [49]. Furthermore, exfoliation and alopecia were shown to be associated with the diagnosis of L. infantum infections in high-prevalence areas in Spain [62]. In Brazil, periorbital alopecia was identified as a clinical sign significantly associated with canine leishmaniosis in dogs [30]. Thus, as indicated by the present results, seborrhea and/or hypotrichosis/alopecia are of prognostic relevance not only for diagnosing the disease but also for disease relapse.

Regarding laboratory alterations, proteinuria was the only significant predictor of disease relapse in the present study. Proteinuria is estimated to affect approximately 50% of naturally L. infantum-infected dogs [17,28,33,45]; it occurs primarily due to immune complex deposition and the associated inflammatory immune response in glomeruli [63] and can cause renal failure, the most common cause of death in canine leishmaniosis [10,29,33,64]. Previous studies have proved proteinuria in dogs with leishmaniosis to be linked to poor prognosis and reduced survival time [17,28,65]. Thus, the onset of adequate therapeutic measures, which commonly include antileishmanial and symptomatic antiproteinuric treatment, is considered essential to counteract proteinuria in dogs with leishmaniosis [33,66]. To counteract the immunopathogenic aspect of glomerulonephritis, i.e., lower the inflammatory response to immune complex deposition, the (additional) use of immunosuppressive drugs is frequently discussed and applied by some veterinarians [33,67]. In general, treatment of glomerulonephritis is considered successful if UPC decreases to ratios below 0.5 or by at least 50% [66]. However, in case of irreversible renal damage, proteinuria might persist despite any treatment. Persistent proteinuria was also observed in several dogs in the present study and should be taken into account when interpreting the results, particularly with regard to upcoming disease relapse. Nevertheless, given that proteinuria represents a risk factor for the progression of renal impairment and is also linked to a higher probability of disease relapse, early recognition of any deterioration in UPC ratios must be ensured through routine assessment of UPC ratios at each monitoring appointment. In a study on apparently healthy dogs infected with L. infantum, 31/87 dogs (35.6%) were found to have proteinuria; therefore, awareness of this topic is important [9]. Of concern, however, is the fact that the relevance of proteinuria for disease and relapse prognosis might still be neglected in clinical practice; according to a questionnaire-based study among veterinarians in Portugal, less than 30% of all respondents always assessed UPC in the monitoring of dogs with canine leishmaniosis and commonly did not even prioritize it when caregivers were financially restricted [27]. To overcome this diagnostic gap, regular urine dipstick monitoring by either the owners at home or the veterinarian might offer a cost-effective alternative. It was proven to be a reliable, sensitive, although not specific, method to assess urinary protein loss in dogs, even if results might be influenced by urine specific gravity and active sediment. Due to low specificity, a protein loss indicated by a urine dipstick should always be confirmed by complete urinalysis and UPC measurement [64,68].

In the present study, higher Leishmania antibody levels trended towards a significant association with upcoming disease relapses. In previous studies, increasing antibody titers were shown to be associated with disease relapse [25,41]. Accordingly, the monitoring of antibody titers and suspicion of disease relapse in case of a marked (more than twofold) increase is suggested by current guidelines [15] and is implemented by (some) veterinarians, at least in endemic countries; in a questionnaire-based study in Portugal, approximately 25% of the veterinarians that responded always considered increasing antibody titers for relapse diagnosis [27]. However, findings on antibodies in dogs in endemic areas might not be directly comparable to studies performed in non-endemic countries, since seasonal variations in antibody titers without clinical relevance, possibly related to a re-exposure to the pathogen, were observed in dogs living in endemic areas [69,70]. Inconclusive findings also exist on the prognostic relevance of antibody measurement. Commonly, high antibody levels are observed in dogs in severe disease stages, which are estimated to have an overall guarded to poor prognosis [16,71,72]. This is attributed to the fact that dogs presenting with high antibody titers mount a Th2-dominated immune response, which lacks protective effects against intracellular parasite replication and favors the formation of immune complexes, thereby promoting the development of disease signs [6,11]. Nevertheless, antibody titers were not associated with survival time of dogs with canine leishmaniosis in a retrospective study in a non-endemic country [17]. Overall, interpretation of antibody titers might also be complicated by previous therapeutic measures; high antibody titers were shown to persist for up to six months or even longer after treatment, despite clinical improvement [15,16,64,73]. In conclusion, increasing and/or high antibody titers might need to be interpreted cautiously in pre-treated dogs (and should not justify the initiation of leishmanicidal treatment on their own, at least in non-endemic countries).

Levels of acute phase proteins are discussed to provide information on disease severity in dogs with leishmaniosis and are thus often included in the monitoring of dogs with leishmaniosis [64,74]. However, high levels of acute-phase proteins were not identified as predictors for upcoming disease relapse in the present study.

Furthermore, results of Leishmania PCR (qualitative and quantitative) have been proposed as a tool for monitoring and assessment of dogs infected with Leishmania spp. [61,64,75,76], but an association with upcoming relapse could not be evaluated in the present study due to a surprisingly low number of PCR-positive conjunctival swabs. A previous study conducted in dogs living in a non-endemic country revealed an adequate sensitivity (78.4%) of conjunctival swab PCR and substantial to moderate correlation with lymph node and bone marrow PCR [77]; variations in applied PCR techniques could have contributed to the observed discrepancy between the aforementioned and the present study’s result. Further studies on diagnostic and prognostic values of positive PCR results for disease relapse, including other low-invasively collected specimens such as vulvar and oral swabs [42,78] and/or different tissues, e.g., lymph nodes [79,80], would be valuable.

One limitation of the present study was the overall low number of dogs that experienced disease relapse during the study period. In addition, none of the dogs that died underwent necropsy, and thus, an association with Leishmania infection and potentially missed disease relapses cannot be ruled out with certainty.

5. Conclusions

Lymphadenopathy, seborrhea, and/or hypotrichosis, as well as proteinuria, were identified as predictors for relapse of disease in the present study on L. infantum-infected dogs in a non-endemic country. In addition, associations might exist with antibody titers measured by ELISA, but subsequent studies are necessary to evaluate their prognostic relevance. The findings emphasize the routine monitoring and the importance of including these predictors as part of routine monitoring in dogs with L. infantum infections to ensure an adequate follow-up, an early recognition of disease relapse, and concomitantly the onset of adequate therapeutic measures to prevent deterioration.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/pathogens14121282/s1, Table S1: Baseline characteristics of dogs before and at the time of enrollment; Table S2: Disease parameters of dogs with relapse of canine leishmaniosis during the one-year study period; Figure S1: Treatment of the 52 dogs included in the study guided by the therapeutic tree for dogs with Leishmania infections in non-endemic areas according to Kaempfle et al., 2025 [21]; Figure S2: Occurrence of upcoming relapse of canine leishmaniosis in 52 dogs during the one-year study period.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.K. and M.B.; methodology, M.K., K.H. and M.B.; software, not applicable; validation, M.B.; formal analysis, M.K. and Y.Z.; investigation, M.K., R.D. and M.B.; resources, K.H. and M.B.; data curation, M.K.; writing—original draft preparation, M.K.; writing—review and editing, R.D., Y.Z., K.H. and M.B.; visualization, M.K. and M.B.; supervision, K.H. and M.B.; project administration, R.D. and M.B.; funding acquisition, K.H. and M.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The doctoral position and parts of the laboratory analyses were funded by IDEXX Laboratories Inc., Westbrook, ME, USA.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Centre for Clinical Veterinary Medicine of the LMU Munich (Government of Upper Bavaria, reference number 244-06-12-2020) on 11 February 2021.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from the animals’ owners.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

There is no commercial conflict of interest, as the information generated here is solely for scientific dissemination. IDEXX Laboratories Inc. (Westbrook, ME, USA) funded parts of the study (see Funding) but had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Cosma, C.; Maia, C.; Khan, N.; Infantino, M.; Del Riccio, M. Leishmaniasis in Humans and Animals: A one health approach for surveillance, prevention and control in a changing world. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2024, 9, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, R.; Garcês, A.; Silva, A.; Brilhante-Simões, P.; Martins, Â.; Duarte, E.L.; Coelho, A.C.; Cardoso, L. Distribution of and relationships between epidemiological and clinicopathological parameters in canine leishmaniosis: A retrospective study of 15 years (2009–2023). Pathogens 2024, 13, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priolo, V.; Ippolito, D.; Rivas-Estanga, K.; De Waure, C.; Martínez-Orellana, P. Canine leishmaniosis global prevalence over the last three decades: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2024, 112, 102211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, D.; Moeller, P.; Thomas, S.M.; Naucke, T.J.; Beierkuhnlein, C. Combining climatic projections and dispersal ability: A method for estimating the responses of sandfly vector species to climate change. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2011, 5, e1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morales-Yuste, M.; Martín-Sánchez, J.; Corpas-Lopez, V. Canine leishmaniasis: Update on epidemiology, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, M.J. The immunopathology of canine vector-borne diseases. Parasit. Vectors 2011, 4, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbiéri, C.L. Immunology of canine leishmaniasis. Parasite Immunol. 2006, 28, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, R.R.; Michalick, M.S.M.; da Silva, M.E.; Dos Santos, C.C.P.; Frézard, F.J.G.; da Silva, S.M. Canine leishmaniasis: An overview of the current status and strategies for control. Biomed. Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 3296893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxarias, M.; Jornet-Rius, O.; Donato, G.; Mateu, C.; Alcover, M.M.; Pennisi, M.G.; Solano-Gallego, L. Signalment, immunological and parasitological status and clinicopathological findings of Leishmania-seropositive apparently healthy dogs. Animals 2023, 13, 1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutinas, A.; Koutinas, C. Pathologic mechanisms underlying the clinical findings in canine leishmaniosis due to Leishmania infantum/chagasi. Vet. Pathol. 2014, 51, 527–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cacheiro-Llaguno, C.; Parody, N.; Escutia, M.R.; Carnés, J. Role of circulating immune complexes in the pathogenesis of canine leishmaniasis: New players in vaccine development. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saridomichelakis, M.N. Advances in the pathogenesis of canine leishmaniosis: Epidemiologic and diagnostic implications. Vet. Dermatol. 2009, 20, 471–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maia, C.; Campino, L. Biomarkers associated with Leishmania infantum exposure, infection, and disease in dogs. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2018, 8, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva, G.; Scalone, A.; Foglia Manzillo, V.; Gramiccia, M.; Pagano, A.; Di Muccio, T.; Gradoni, L. Incidence and time course of Leishmania infantum infections examined by parasitological, serologic, and nested-PCR techniques in a cohort of naive dogs exposed to three consecutive transmission seasons. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2006, 44, 1318–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solano-Gallego, L.; Miró, G.; Koutinas, A.; Cardoso, L.; Pennisi, M.G.; Ferrer, L.; Bourdeau, P.; Oliva, G.; Baneth, G. LeishVet guidelines for the practical management of canine leishmaniosis. Parasit. Vectors 2011, 4, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roura, X.; Fondati, A.; Lubas, G.; Gradoni, L.; Maroli, M.; Oliva, G.; Paltrinieri, S.; Zatelli, A.; Zini, E. Prognosis and monitoring of leishmaniasis in dogs: A working group report. Vet. J. 2013, 198, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geisweid, K.; Mueller, R.; Sauter-Louis, C.; Hartmann, K. Prognostic analytes in dogs with Leishmania infantum infection living in a non-endemic area. Vet. Rec. 2012, 171, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solano-Gallego, L.; Di Filippo, L.; Ordeix, L.; Planellas, M.; Roura, X.; Altet, L.; Martínez-Orellana, P.; Montserrat, S. Early reduction of Leishmania infantum-specific antibodies and blood parasitemia during treatment in dogs with moderate or severe disease. Parasit. Vectors 2016, 9, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miró, G.; Gálvez, R.; Fraile, C.; Descalzo, M.A.; Molina, R. Infectivity to Phlebotomus perniciosus of dogs naturally parasitized with Leishmania infantum after different treatments. Parasit. Vectors 2011, 4, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noli, C.; Auxilia, S.T. Treatment of canine Old World visceral leishmaniasis: A systematic review. Vet. Dermatol. 2005, 16, 213–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaempfle, M.; Hartmann, K.; Bergmann, M. Treatment of Leishmania infantum infections in dogs. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsakmakidis, I.; Lefkaditis, M.; Zaralis, K.; Arsenos, G. Alternative hosts of Leishmania infantum: A neglected parasite in Europe. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2024, 56, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miró, G.; Petersen, C.; Cardoso, L.; Bourdeau, P.; Baneth, G.; Solano-Gallego, L.; Pennisi, M.G.; Ferrer, L.; Oliva, G. Novel areas for prevention and control of canine leishmaniosis. Trends Parasitol. 2017, 33, 718–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarquis, J.; Parody, N.; Montoya, A.; Cacheiro-Llaguno, C.; Barrera, J.P.; Checa, R.; Daza, M.A.; Carnés, J.; Miró, G. Clinical validation of circulating immune complexes for use as a diagnostic marker of canine leishmaniosis. Front. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 1368929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manna, L.; Corso, R.; Galiero, G.; Cerrone, A.; Muzj, P.; Gravino, A.E. Long-term follow-up of dogs with leishmaniosis treated with meglumine antimoniate plus allopurinol versus miltefosine plus allopurinol. Parasit. Vectors 2015, 8, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miró, G.; Segarra, S.; Cerón, J.J.; Ferrer, L.; Solano-Gallego, L.; Montell, L.; Costa, E.; Teichenne, J.; Mariné-Casadó, R.; Roura, X. New immunomodulatory treatment protocol for canine leishmaniosis reduces parasitemia and proteinuria. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2024, 18, e0012712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.A.; Santos, R.; Nóbrega, C.; Mega, C.; Cruz, R.; Esteves, F.; Santos, C.; Coelho, C.; Mesquita, J.R.; Vala, H.; et al. A questionnaire-based survey on the long-term management of canine leishmaniosis by veterinary practitioners. Animals 2022, 12, 731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Jong, M.K.; Rappoldt, A.; Broere, F.; Piek, C.J. Survival time and prognostic factors in canine leishmaniosis in a non-endemic country treated with a two-phase protocol including initial allopurinol monotherapy. Parasit. Vectors 2023, 16, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, M.A.; Santos, R.; Oliveira, R.; Costa, L.; Prata, A.; Gonçalves, V.; Roquette, M.; Vala, H.; Santos-Gomes, G. Prognostic factors and life expectancy in canine leishmaniosis. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouvêa, M.V.; Mendonça, I.L.; Cruz Mdo, S.; Costa, C.H.; Braga, J.U.; Werneck, G.L. Predictive factors for Leishmania infantum infection in dogs examined at a veterinary teaching hospital in Teresina, State of Piauí, Brazil. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2016, 49, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa Gonçalves, R.; Alves de Pinho, F.; Dinis-Oliveira, R.J.; Azevedo, R.; Gaifem, J.; Larangeira, D.F.; Ramos-Sanchez, E.M.; Goto, H.; Silvestre, R.; Barrouin-Melo, S.M. Mathematical modelling using predictive biomarkers for the outcome of canine leishmaniasis upon chemotherapy. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz, C.R.; Sarquis, J.; Daza, M.; Miró, G. Exploring the impact of epidemiological and clinical factors on the progression of canine leishmaniosis by statistical and whole genome analyses: From breed predisposition to comorbidities. Int. J. Parasitol. 2024, 54, 401–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roura, X.; Cortadellas, O.; Day, M.J.; Benali, S.L.; Zatelli, A. Canine leishmaniosis and kidney disease: Q&A for an overall management in clinical practice. J. Small Anim. Pract. 2021, 62, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budde, J.A.; McCluskey, D.M. Plumb’s Veterinary Drug Handbook; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kaempfle, M.; Bergmann, M.; Koelle, P.; Hartmann, K. High performance liquid chromatography analysis and description of purine content of diets suitable for dogs with Leishmania infection during allopurinol treatment—A pilot trial. Animals 2023, 13, 3060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeishVet. LeishVet Fact Sheet: Practical Management of Canine Leishmaniosis. Available online: https://www.leishvet.org/canine-leishmaniosis-guidelines/ (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Cannon, S.H.; Levy, J.K.; Kirk, S.K.; Crawford, P.C.; Leutenegger, C.M.; Shuster, J.J.; Liu, J.; Chandrashekar, R. Infectious diseases in dogs rescued during dogfighting investigations. Vet. J. 2016, 211, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dohoo, I.R.; Martin, S.W.; Stryhn, H. Veterinary Epidemiologic Research, 2nd ed.; VER, Inc.: Charlottetown, PEI, Canada, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Buckland, S.T.; Burnham, K.P.; Augustin, N.H. Model selection: An integral part of inference. Biometrics 1997, 53, 603–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calcagno, V.; de Mazancourt, C. glmulti: An R package for easy automated model selection with (generalized) linear models. J. Stat. Softw. 2010, 34, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarquis, J.; Raposo, L.M.; Sanz, C.R.; Montoya, A.; Barrera, J.P.; Checa, R.; Perez-Montero, B.; Rodríguez, M.L.F.; Miró, G. Relapses in canine leishmaniosis: Risk factors identified through mixed-effects logistic regression. Parasit. Vectors 2024, 17, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández, L.; Montoya, A.; Checa, R.; Dado, D.; Gálvez, R.; Otranto, D.; Latrofa, M.S.; Baneth, G.; Miró, G. Course of experimental infection of canine leishmaniosis: Follow-up and utility of noninvasive diagnostic techniques. Vet. Parasitol. 2015, 207, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Gomes, G.M.; Rosa, R.; Leandro, C.; Cortes, S.; Romão, P.; Silveira, H. Cytokine expression during the outcome of canine experimental infection by Leishmania infantum. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2002, 88, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, A.B.; Martins-Filho, O.A.; Teixeira-Carvalho, A.; Carvalho, M.G.; Mayrink, W.; França-Silva, J.C.; Giunchetti, R.C.; Genaro, O.; Corrêa-Oliveira, R. Parasite density and impaired biochemical/hematological status are associated with severe clinical aspects of canine visceral leishmaniasis. Res. Vet. Sci. 2006, 81, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meléndez-Lazo, A.; Ordeix, L.; Planellas, M.; Pastor, J.; Solano-Gallego, L. Clinicopathological findings in sick dogs naturally infected with Leishmania infantum: Comparison of five different clinical classification systems. Res. Vet. Sci. 2018, 117, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noli, C.; Saridomichelakis, M.N. An update on the diagnosis and treatment of canine leishmaniosis caused by Leishmania infantum (syn. L. chagasi). Vet. J. 2014, 202, 425–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciaramella, P.; Oliva, G.; Luna, R.D.; Gradoni, L.; Ambrosio, R.; Cortese, L.; Scalone, A.; Persechino, A. A retrospective clinical study of canine leishmaniasis in 150 dogs naturally infected by Leishmania infantum. Vet. Rec. 1997, 141, 539–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foglia Manzillo, V.; Di Muccio, T.; Cappiello, S.; Scalone, A.; Paparcone, R.; Fiorentino, E.; Gizzarelli, M.; Gramiccia, M.; Gradoni, L.; Oliva, G. Prospective study on the incidence and progression of clinical signs in naïve dogs naturally infected by Leishmania infantum. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2013, 7, e2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdeau, P.; Saridomichelakis, M.N.; Oliveira, A.; Oliva, G.; Kotnik, T.; Gálvez, R.; Foglia Manzillo, V.; Koutinas, A.F.; Pereira da Fonseca, I.; Miró, G. Management of canine leishmaniosis in endemic SW European regions: A questionnaire-based multinational survey. Parasit. Vectors 2014, 7, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, W.G.; Michalick, M.S.; de Melo, M.N.; Luiz Tafuri, W.; Luiz Tafuri, W. Canine visceral leishmaniasis: A histopathological study of lymph nodes. Acta Trop. 2004, 92, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baneth, G.; Petersen, C.; Solano-Gallego, L.; Sykes, J.E. 96—Leishmaniosis. In Greene’s Infectious Diseases of the Dog and Cat, 5th ed.; Sykes, J.E., Ed.; W.B. Saunders: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2021; pp. 1179–1202. [Google Scholar]

- Mylonakis, M.E.; Papaioannou, N.; Saridomichelakis, M.N.; Koutinas, A.F.; Billinis, C.; Kontos, V.I. Cytologic patterns of lymphadenopathy in dogs infected with Leishmania infantum. Vet. Clin. Pathol. 2005, 34, 243–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giunchetti, R.C.; Martins-Filho, O.A.; Carneiro, C.M.; Mayrink, W.; Marques, M.J.; Tafuri, W.L.; Corrêa-Oliveira, R.; Reis, A.B. Histopathology, parasite density and cell phenotypes of the popliteal lymph node in canine visceral leishmaniasis. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2008, 121, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrer, L.; Rabanal, R.; Fondevila, D.; Ramos, J.; Domingo, M. Skin lesions in canine leishmaniasis. J. Small Anim. Pract. 1988, 29, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solano-Gallego, L.; Fernández-Bellon, H.; Morell, P.; Fondevila, D.; Alberola, J.; Ramis, A.; Ferrer, L. Histological and immunohistochemical study of clinically normal skin of Leishmania infantum-infected dogs. J. Comp. Pathol. 2004, 130, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saridomichelakis, M.N.; Koutinas, A.F. Cutaneous involvement in canine leishmaniosis due to Leishmania infantum (syn. L. chagasi). Vet. Dermatol. 2014, 25, 61–71, e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saridomichelakis, M.N.; Baneth, G.; Colombo, S.; Dantas-Torres, F.; Ferrer, L.; Fondati, A.; Miró, G.; Ordeix, L.; Otranto, D.; Noli, C. World association for veterinary dermatology consensus statement for diagnosis, and evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for treatment and prevention of canine leishmaniosis. Vet. Dermatol. 2025, 36, 723–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadogiannakis, E.I.; Koutinas, A.F.; Saridomichelakis, M.N.; Vlemmas, J.; Lekkas, S.; Karameris, A.; Fytianou, A. Cellular immunophenotyping of exfoliative dermatitis in canine leishmaniosis (Leishmania infantum). Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2005, 104, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordeix, L.; Dalmau, A.; Osso, M.; Llull, J.; Montserrat-Sangrà, S.; Solano-Gallego, L. Histological and parasitological distinctive findings in clinically-lesioned and normal-looking skin of dogs with different clinical stages of leishmaniosis. Parasit. Vectors 2017, 10, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brachelente, C.; Müller, N.; Doherr, M.G.; Sattler, U.; Welle, M. Cutaneous leishmaniasis in naturally infected dogs is associated with a T helper-2-biased immune response. Vet. Pathol. 2005, 42, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manna, L.; Reale, S.; Viola, E.; Vitale, F.; Foglia Manzillo, V.; Pavone, L.M.; Caracappa, S.; Gravino, A.E. Leishmania DNA load and cytokine expression levels in asymptomatic naturally infected dogs. Vet. Parasitol. 2006, 142, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galán-Relaño, Á.; Maldonado, A.; Gómez-Gascón, L.; Tarradas, C.; Astorga, R.J.; Luque, I.; Huerta, B. Pre-test probability and likelihood ratios for clinical findings in canine leishmaniasis. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2022, 69, 3540–3547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zatelli, A.; Borgarelli, M.; Santilli, R.; Bonfanti, U.; Nigrisoli, E.; Zanatta, R.; Tarducci, A.; Guarraci, A. Glomerular lesions in dogs infected with Leishmania organisms. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2003, 64, 558–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paltrinieri, S.; Gradoni, L.; Roura, X.; Zatelli, A.; Zini, E. Laboratory tests for diagnosing and monitoring canine leishmaniasis. Vet. Clin. Pathol. 2016, 45, 552–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, F.; Boretti, F.S.; Gerber, B. Prognostic factors in dogs with common causes of proteinuria. Schweiz. Arch. Tierheilkd. 2022, 164, 525–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.; Elliott, J.; Francey, T.; Polzin, D.; Vaden, S. Consensus recommendations for standard therapy of glomerular disease in dogs. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2013, 27, S27–S43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteiro, M.; Prata, S.; Cardoso, L.; Pereira da Fonseca, I.; Leal, R.O. Dogs with leishmaniosis: How are we managing proteinuria in daily practice? A Portuguese questionnaire-based study. Parasit. Vectors 2022, 15, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zatelli, A.; Paltrinieri, S.; Nizi, F.; Roura, X.; Zini, E. Evaluation of a urine dipstick test for confirmation or exclusion of proteinuria in dogs. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2010, 71, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalera, M.A.; Uva, A.; Carbonara, M.; Mendoza-Roldan, J.A.; Roura, X.; Cerón, J.J.; Otranto, D.; Zatelli, A. Seasonal variation of anti-Leishmania infantum antibodies and laboratory abnormalities in dogs with leishmaniosis. Parasit. Vectors 2025, 18, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalera, M.A.; Iatta, R.; Panarese, R.; Mendoza-Roldan, J.A.; Gernone, F.; Otranto, D.; Paltrinieri, S.; Zatelli, A. Seasonal variation in canine anti-Leishmania infantum antibody titres. Vet. J. 2021, 271, 105638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solano-Gallego, L.; Koutinas, A.; Miró, G.; Cardoso, L.; Pennisi, M.G.; Ferrer, L.; Bourdeau, P.; Oliva, G.; Baneth, G. Directions for the diagnosis, clinical staging, treatment and prevention of canine leishmaniosis. Vet. Parasitol. 2009, 165, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, B.; Romano, A.; Zanatta, R.; Spina, S.; Mignone, W.; Ingravalle, F.; Barzanti, P.; Ceccarelli, L.; Goria, M. Serum indirect immunofluorescence assay and real-time PCR results in dogs affected by Leishmania infantum: Evaluation before and after treatment at different clinical stages. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 2019, 31, 222–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miró, G.; Oliva, G.; Cruz, I.; Cañavate, C.; Mortarino, M.; Vischer, C.; Bianciardi, P. Multicentric, controlled clinical study to evaluate effectiveness and safety of miltefosine and allopurinol for canine leishmaniosis. Vet. Dermatol. 2009, 20, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceron, J.J.; Pardo-Marin, L.; Caldin, M.; Furlanello, T.; Solano-Gallego, L.; Tecles, F.; Bernal, L.; Baneth, G.; Martinez-Subiela, S. Use of acute phase proteins for the clinical assessment and management of canine leishmaniosis: General recommendations. BMC Vet. Res. 2018, 14, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manna, L.; Reale, S.; Vitale, F.; Picillo, E.; Pavone, L.M.; Gravino, A.E. Real-time PCR assay in Leishmania-infected dogs treated with meglumine antimoniate and allopurinol. Vet. J. 2008, 177, 279–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francino, O.; Altet, L.; Sánchez-Robert, E.; Rodriguez, A.; Solano-Gallego, L.; Alberola, J.; Ferrer, L.; Sánchez, A.; Roura, X. Advantages of real-time PCR assay for diagnosis and monitoring of canine leishmaniosis. Vet. Parasitol. 2006, 137, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geisweid, K.; Weber, K.; Sauter-Louis, C.; Hartmann, K. Evaluation of a conjunctival swab polymerase chain reaction for the detection of Leishmania infantum in dogs in a non-endemic area. Vet. J. 2013, 198, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalera, M.A.; Zatelli, A.; Donghia, R.; Mendoza-Roldan, J.A.; Gernone, F.; Otranto, D.; Iatta, R. Conjunctival swab real time-PCR in Leishmania infantum seropositive dogs: Diagnostic and prognostic values. Biology 2022, 11, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lombardo, G.; Pennisi, M.G.; Lupo, T.; Migliazzo, A.; Caprì, A.; Solano-Gallego, L. Detection of Leishmania infantum DNA by real-time PCR in canine oral and conjunctival swabs and comparison with other diagnostic techniques. Vet. Parasitol. 2012, 184, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aschar, M.; de Oliveira, E.T.; Laurenti, M.D.; Marcondes, M.; Tolezano, J.E.; Hiramoto, R.M.; Corbett, C.E.; da Matta, V.L. Value of the oral swab for the molecular diagnosis of dogs in different stages of infection with Leishmania infantum. Vet. Parasitol. 2016, 225, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).