Abstract

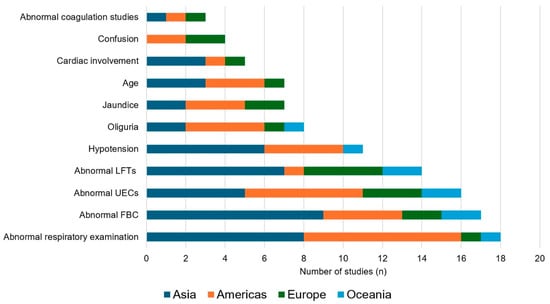

This scoping review of original literature published before 1 March 2025 examined the demographic and simple clinical and laboratory findings associated with the development of severe leptospirosis. The definition of severe leptospirosis varied in different studies, but for the purposes of this review it included death or patients with a more complicated clinical course. There were 35 articles that satisfied the review’s inclusion criteria. Increasing age was associated with severe disease in 7 studies. Abnormal respiratory examination findings (18 studies), hypotension (11 studies), oliguria (8 studies), jaundice (7 studies) and altered mental status (4 studies) also helped identify high-risk patients. Abnormal laboratory tests—specifically the complete blood count (17 studies), measures of renal function (16 studies) and liver function (14 studies)—were also associated with severe disease. There was geographical heterogeneity in the clinical phenotype of severe disease, but the presence of hypotension, respiratory or renal involvement had prognostic utility in all regions. Simple bedside findings and basic laboratory tests can provide valuable clinical information in patients with leptospirosis. Integration of these indices into early risk stratification tools may facilitate recognition of the high-risk patient and expedite escalation of care in resource-limited settings where most cases of life-threatening leptospirosis are seen.

1. Introduction

Leptospirosis is a globally distributed zoonotic disease which is caused by pathogenic bacterial spirochaetes from the Leptospira genus [1]. It was estimated in 2015 that, globally, there were approximately 1 million annual cases of the disease with 60,000 deaths [2]. There is no effective vaccine for human leptospirosis, avoiding exposure to the pathogen is challenging, and chemoprophylaxis is not a practical public health strategy. While most cases of leptospirosis are mild and self-limiting, severe disease can occur with a case fatality rate that can exceed 50% [1,3].

Severe leptospirosis can develop in otherwise well individuals, presenting as a rapidly progressive multisystem illness with clinical manifestations that include shock, respiratory failure, pulmonary haemorrhage and acute kidney injury (AKI). Multimodal critical care support including vasopressors, mechanical ventilation and renal replacement therapy may be required to ensure survival [4]. However, leptospirosis disproportionately affects people living in rural and resource-limited settings, where this sophisticated critical care is often unavailable. In these locations, earlier identification of the patient at highest risk of deterioration can inform clinical management and can expedite transfer to referral centres for delivery of life-saving critical care support.

But of course, the rural and remote healthcare facilities where individuals with leptospirosis first present also frequently lack the diagnostic resources that help identify the high-risk patient. In these locations, where there is often limited access to laboratory and radiology support, clinicians must frequently rely on bedside clinical assessment to determine which patients need prompt referral for escalation of care and which patients can avoid unnecessary and costly transfers.

Researchers from different parts of the world have identified a variety of demographic factors, clinical features and simple laboratory investigations that identify the high-risk patient. However, there are approximately 300 different pathogenic serovars of Leptospira and the serovars that are prevalent in different regions vary greatly. This may contribute to a variation in the clinical phenotypes of leptospirosis that are seen in different parts of the world and the clinical signs that have prognostic utility [5,6,7].

This scoping review was performed to define the demographic characteristics, the clinical findings and the simple laboratory investigations that were most associated with a complicated clinical course in patients with leptospirosis in different parts of the world. The review aimed to determine if there were any patterns in the presentation of individuals with more severe disease and if any clinical or laboratory features had universal prognostic utility. It was hoped that this would provide data to inform the optimal clinical care of this unique, life-threatening pathogen in the resource-limited settings where it is most encountered.

2. Methods

2.1. Scoping Review

This scoping review aimed to identify the demographic, clinical and simple laboratory characteristics of patients presenting with laboratory-confirmed leptospirosis that were most associated with the subsequent development of severe disease. On 2 March 2025, we conducted a search of published literature from five databases, PubMed, Medline (Ovid), Emcare (Ovid), CINAHL (EBSCO) and Scopus, with the search strategy outlined in Supplementary File S1. The search strategy was developed in consultation with a medical librarian with expertise in scoping review methodology. In addition, we examined the references of the articles and other reviews to identify other publications which had not been identified in our initial search. The review was registered with Open Science Framework (http://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/YAGSB) and reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines (Supplementary File S2) [8].

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

Prospective or retrospective studies of individuals with laboratory-confirmed leptospirosis were eligible for inclusion. For an individual to have a laboratory-confirmed diagnosis, it was necessary to satisfy at least one of the following criteria: (1) Leptospira organisms isolated from blood culture; (2) detection of Leptospira in blood or urine by polymerase chain reaction (PCR); (3) microscopic agglutination test (MAT) results which satisfied the local definition of confirmed disease. Studies were excluded if there was no comparison between severe and non-severe groups or if no statistically significant findings were discovered; duplicate publications were also excluded.

2.3. Study Selection

The searches were completed twice, independently, by two reviewers, P.R. and L.J. Reference management software (Endnote version 9) was utilised to manage references and to identify duplicates. The two reviewers screened all potentially eligible studies independently and aimed to reach agreement about their inclusion. If uncertainty remained, a consensus was achieved during discussions with the senior authors (J.H., I.I., S.S.) until agreement was reached.

2.4. Data Extraction and Outcomes

Relevant data from each included study were extracted and collated. These data included the year of publication, the type of study, the geographical location of the study, the number of study participants, the characteristics of the hospital, the definition of severe disease and the factors that the study’s authors identified as being associated with severe disease.

2.5. Bias Assessment

The risk of bias for each study was evaluated using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) (Supplementary File S3) [8]. Two reviewers (P.R. and L.J.) independently assessed study quality, considering factors such as study design, participant selection, sample representativeness, method of case verification, and adequacy of control selection and adjustment. Discrepancies in scoring were resolved by discussion until a consensus was reached.

For case–control and cohort studies, the standard NOS criteria were applied, and scores ranged from 0 to 9, with 7–9 stars determined to be low risk of bias, 4–6 stars as being moderate risk of bias and 0–3 stars being high risk of bias. For cross-sectional studies, an adapted version of the NOS was used to ensure appropriate evaluation of study characteristics specific to this design [9]. This adaptation focused on the selection of participants, comparability of study groups, and ascertainment of the outcome (Supplementary File S3).

3. Results

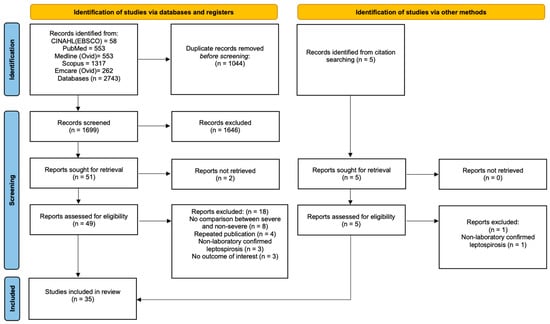

We identified 1704 potentially eligible studies; 35 satisfied criteria for inclusion in the review (Figure 1). These 35 studies, stratified by their continent of origin, are summarised in Table 1, Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4 and Figure 2.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of the study selection process. CINAHL, cumulative index of nursing and allied health; EBSCO, Elton B. Stephens Company.

Table 1.

Summary of the findings of the 15 studies from Asia that were included in this scoping review.

Table 2.

Summary of the findings of the 10 studies from the Americas that were included in this scoping review.

Table 3.

Summary of the findings of the 6 studies from Europe that were included in this scoping review.

Table 4.

Summary of the findings of the 4 studies from Oceania that were included in this scoping review.

Figure 2.

The association of selected variables with severe Leptospirosis, stratified by global region. UECs: Urea electrolytes and creatinine; FBC: Full blood count; LFTs: Liver function tests.

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

3.1.1. Age

Multiple studies have found that disease severity is correlated with increasing age. Age cut-offs have varied in different reports, but seven studies in our review identified an association between older age and the risk of severe disease [10,11,14,26,27,28,35]. A Thai multicentre study of 2188 participants by Suwannarong et al. found that death and morbidity (jaundice, haemorrhage, cardiac and pulmonary involvement) were 1.3 times more likely in those over 36 years of age [10]. A multicentre retrospective Malaysian study with 525 participants by Al Hariri et al. reported that death was more common in patients greater than 40 years of age [11]. These findings were corroborated by three Brazilian multicentre retrospective studies which found older age (greater than 40 and 60 years in the different series) was associated with an increased risk of death [26,27,28]. A French study of 160 patients requiring ICU admission, with a median age of 54, also found that increasing age was associated with in-hospital mortality [35].

3.1.2. Gender

The incidence of leptospirosis is higher in males than in females; in many studies infection in males is nearly ten times more likely than in females, which is felt to be explained by differences in occupational and recreational exposures [2,45]. However, almost all studies have found no statistically significant difference between males and females in the rates of disease severity or death [10,11,12,18,19,20,23,24,27,29,30,31,35,36,37,43]. In our review, we could identify only one study from the Philippines with 203 participants which reported a significant association between gender and disease severity. In this series, men had an odds ratio (OR) of 3.3 (95% confidence interval (CI): 1.2–12.6) for the composite endpoint of AKI, requirement for dialysis, pulmonary haemorrhage and transaminitis [15].

3.2. Clinical Findings

3.2.1. Comorbidities and Lifestyle Factors

Very few papers found an association between comorbidities and severe disease. Two single-centre studies in Guadeloupe and France found that chronic alcohol misuse increased the risk of death [31,35]. In the study from Guadeloupe, a history of hypertension was also a risk factor for death [31]. The Malaysian study by Al Hariri et al. identified that chronic kidney disease was an independent risk factor for deterioration [11]. Meanwhile, a New Caledonian study of 176 patients found that a history of smoking was a risk for death, disease requiring intensive interventions (including renal replacement therapy (RRT), mechanical ventilation, vasopressor support and blood transfusion) or alveolar haemorrhage [43].

3.2.2. Symptoms

A retrospective multicentre Chinese study identified dyspnoea as the strongest independent predictor for ICU admission (OR (95% CI): 19.1 (1.2–692.7)) [18]. A prospective Sri Lankan study of 79 patients also found that dyspnoea at presentation was associated with end organ failure (OR (95% CI): 7.1 (1.3–38.4)) [21]. A 2008 Brazilian study reported that individuals with pulmonary involvement (which included dyspnoea as well as haemoptysis, pulmonary rales on physical examination, and intubation) were 9 times (95% CI 5–17) more likely to die than those without pulmonary involvement [27].

3.2.3. Vital Signs

Blood Pressure

Thai, Taiwanese, Malaysian, Sri Lankan, Caribbean, Brazilian and Australian studies have identified an association between hypotension and severe disease [12,13,16,19,20,24,28,29,30,41,43]. A large case–control study of 480 patients from Thailand studies showed that blood pressure < 90/60 mmHg within the first day of admission was associated with death, renal and respiratory insufficiency (OR (95% CI): 17.3 (6.9–43.6)) [12]. A small, retrospective multicentre Taiwanese study of 57 patients determined that blood pressure was the only independent predictor for severity (OR (95% CI):14.8 (3.0–73.6)) of over 50 variables analysed [22].

Respiratory Rate

A 2016 Brazilian study of 206 patients found tachypnoea (>25 breaths per minute) was associated with pulmonary haemorrhage (OR (95% CI): 13 (1.3–132)) [29]. Another 2010 Brazilian study which examined respiratory rate as a continuous variable found that a rising rate increased the risk for ICU admission (OR (95% CI): 1.1 (1.1–1.2)) [30]. A study from the French West Indies also found that a respiratory rate over 20 breaths/min increased the risk of death by 11.7 (95% CI 2.8–48.5) [34].

Level of Consciousness

The role of altered mental status in predicting severe disease was explored in four studies across the Americas and Europe, but in no study from Asia or Oceania [30,31,35,39]. A French retrospective study conducted with 160 patients admitted to ICU found confusion as a predictor for death [35]. A Turkish study found that altered mental status raised risk of subsequent death by 8.9 (95% CI: 1.6–50.7) [39]. A Brazilian study with a focus on pulmonary haemorrhage determined that a Glasgow Coma Score (GCS) < 15 was associated with a 7.7 (95% CI 1.3–23.0) times the risk of pulmonary haemorrhage and, after shock at presentation, was the most predictive factor of this complication [30]. Finally, a study from Guadeloupe found that impaired consciousness was associated with death, requirement for dialysis or mechanical ventilation (OR (95% CI): 3.8 (1.1–13.2)) [31].

Heart Rate, Temperature and Pulse Oximetry

Our search strategy did not find any papers examining the independent prognostic value of heart rate, temperature or pulse oximetry.

3.2.4. Bedside Examination Findings

Jaundice

Jaundice was identified as a predictive factor for severe disease in seven studies from Brazil, France and the French West Indies, Sri Lanka and Thailand [12,21,25,31,32,35,40]. A small, single-centre French cohort study of 62 patients found that patients with jaundice at any point during admission were 10.1 times (95% CI 1.8–56.8) more likely to require ICU admission or RRT than patients without jaundice [40]. In another French study of patients admitted to ICU, the risk of death was greater in those with than without jaundice [35]. A retrospective Thai study of 480 patients showed the presence of jaundice at admission raised the likelihood of death and renal and respiratory failure threefold (95% CI: 1.7–5.7) [12].

Respiratory Auscultation Abnormalities

Studies from Australia, Guadeloupe, Malaysia, Martinique and Thailand have reported that patients presenting with any abnormality on respiratory auscultation have more severe disease than those without changes on auscultation [13,16,31,32,41]. Most of these studies included any changes detected on auscultation in their definition; only one prospective Thai study of 121 patients reported pulmonary rales specifically as a risk for death (RR (95% CI): 5.2 (1.4–19.9)) [16].

Oliguria

Reports from Australia, Brazil, the French West Indies, Sri Lanka, Thailand and Ukraine have reported that oliguria (defined in different studies as a daily urine output below 400 or 500 mL) is associated with severe disease and death [16,21,27,31,32,34,37,41,46]. Authors of a retrospective Australian study of 402 adults found that oliguria had the greatest independent prognostic utility of any of the clinical variables they analysed (OR (95% CI): 16.4 (6.9–38.8)) [41]. A French West Indies group found that patients with oliguria at presentation had an OR (95% CI) of 9.0 (2.1–37.9) for death [34].

3.3. Laboratory Findings

3.3.1. Haematology

An Australian study found that anaemia, leucocytosis and thrombocytopenia were all associated with ICU admission [41]. A Sri Lankan study also showed that anaemia, leucocytosis and thrombocytopaenia were associated with severe disease, but this study also showed that leucopoenia was associated with disease severity [14,42]. A Ukrainian case–control study which found leucocytosis and thrombocytopaenia were associated with disease severity, as did studies from the Philippines and Puerto Rico [15,33,37].

A Chinese retrospective multicentre study of 95 patients discovered a neutrophilia to be the only laboratory variable that independently predicted ICU admission (OR (95% CI):1.6 (1.0–2.5)) [18]. Similarly, a Sri Lankan study identified that not only leucocytosis >11,000 mm3 (OR (95% CI): 3.6 (1.3–9.9) but also a neutrophil percentage of >75% (OR (95% CI):13.4 (1.7–108.1)) correlated with disease severity [21].

Studies in Brazil, Malaysia and Thailand identified that a lower haematocrit was associated with severe disease [12,13,28]. The Brazilian study found that when haematocrit was below 30%, the risk of deterioration increased by a factor of 3.5 (95% CI 1.6–7.6) [28].

Studies in Malaysia, Martinique and Türkiye all found a link between a prolonged prothrombin time (PT) and disease severity [11,32,39]. In the study from Türkiye, 66.7% of the patients who died had a prolonged PT compared to only 22.2% of survivors. In the Malaysian study by Al Hariri et al., both PT and activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) were associated with disease severity; however it showed that a prolonged PT was more frequent in the cohort (179/525 (34%) had a prolonged PT compared to 40/525 (7.6%) who had a prolonged aPTT) [11,39].

3.3.2. Biochemistry

Urea and Creatinine

An elevated serum creatinine at presentation was associated with severe disease in studies from Australia, Brazil, Puerto Rico, and Ukraine [21,27,30,33,37,41,42]. Acute Kidney Injury (AKI, variably defined across studies) was seen in multiple studies across Brazil and Malaysia as a predictor of ICU admission and death, with the Brazilian cohort study finding it raised the risk of ICU admission 14-fold (95% CI 1.3–150) [20,29]. The multicentre Malaysian study of 525 patients by Al Hariri et al. found that over 80% of the fatal cases had AKI compared to only 42.8% of the survivors [11]. Multiple studies found that an elevated creatinine was associated with a complicated disease course, like a New Caledonian study which found a serum creatinine > 200 µmol/L raised likelihood of death or requirement for intensive medical intervention by 5.86 times (95% CI 1.6–21.3) [43]. This was echoed in a Sri Lankan study which found that an elevated serum creatinine >120 μmol/L in a small cohort of 79 patients was the strongest predictor of severe disease with an OR of 29.1 (95% CI 6.1–140.2) [21].

Electrolytes

A Sri Lankan study found that a serum sodium < 131 mEq/L at presentation independently predicted severe disease (OR (95% CI): 6.4 (1.4–30.4)) [14]. A Brazilian study showed an association between hyperkalaemia and pulmonary haemorrhage, whilst a prospective cohort study in Thailand found that hyperkalaemia was independently associated with death (RR (95% CI): 5.9 (1.7–21)) [16,30].

Bilirubin

Studies from Sri Lanka, Ukraine and from France and its overseas territories have each identified a correlation between bilirubin levels at admission and the risk of subsequent deterioration [21,35,36,37]. A single-centre New Caledonian study of 47 patients found bilirubin >35 µmol/L increased the risk of death and need for dialysis fivefold (95% CI 1.3–20) [44].

Other Liver Function Tests

A Malaysian study found that a serum ALT > 50 IU/L increased the likelihood of a patient having AKI or pulmonary involvement (OR (95% CI): 2.9 (1.2–7.2)) [20]. A Sri Lankan study identified that an ALT > 70 IU/L at presentation was the strongest risk factor for death, ICU admission, and prolonged hospital stay [14]. Another 2023 Sri Lankan study that examined 88 patients found that an elevated AST was associated with subsequent death (OR (95% CI): 5.3 (1.6–17.1)) [19]. A multicentre retrospective Indian study of 101 patients found that the AST:ALT ratio was the only laboratory finding to predict severe disease [17].

3.4. Other Investigations

3.4.1. Chest Radiological Findings

One study of 68 patients in the French West Indies found that the presence of alveolar infiltrates on chest X-ray at presentation increased the risk of death by 7.3 times (95% CI 1.7–31.7) [34].

3.4.2. Electrocardiogram Changes

A retrospective Malaysian study found that non-specific T wave changes, conduction abnormalities and atrial fibrillation (AF) on electrocardiogram (ECG) were significantly associated with death [11]. A prospective Sri Lankan study of 88 patients found that AF was the only ECG abnormality that was associated with death [19]. A retrospective multicentre study from the French West Indies reported that ECG repolarization abnormalities predicted death [21,34]. Finally, a French group examined a cohort of 62 patients and looked for ECG abnormalities and clinical and laboratory evidence of cardiac involvement (including shock, myocarditis or pericarditis), discovering that the presentation of this cardiac involvement increased the risk of ICU admission or dialysis by 31.2 times (95% CI 1.8–550) [40].

4. Discussion

This review illustrates that bedside findings and simple laboratory tests can rapidly identify patients with leptospirosis who are at greatest risk of a more complicated disease course. Although the studies were performed in different continents and examined a diverse range of variables in both resource-rich and resource-limited settings, it was notable that patients with hypotension, signs of respiratory involvement or evidence of renal involvement were consistently identified as the patients who were at greatest risk of deterioration and death. The presence of these findings should, in the appropriate clinical context, encourage clinicians to consider escalation of care or, in resource-limited settings, transfer to a referral centre. Their presence can also inform the supportive care that these patients receive during their hospitalisation with this life-threatening disease.

The presence of respiratory involvement predicted severe disease in 18 of the studies, emphasising its reputation as perhaps the most feared manifestation of leptospirosis [19,47]. The definition of respiratory involvement varied in the different studies; although the presence of abnormal findings on auscultation was examined most commonly, tachypnoea and changes on plain chest X-ray also had prognostic utility. The manifestations of pulmonary leptospirosis range from mild dyspnoea and cough to life-threatening pulmonary haemorrhage and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) [48]. These clinical findings reflect the underlying pulmonary oedema and haemorrhage that are seen in patients with lung involvement. Although the pathophysiology of respiratory involvement is incompletely understood, it is believed to result from increased permeability due to vascular injury and impaired fluid handling [49,50,51]. The presence of lung involvement may not only suggest that a patient is at risk of, sometimes rapid, deterioration but it should also discourage clinicians from delivering aggressive fluid resuscitation that might exacerbate incipient pulmonary oedema [52]. We did not find any studies examining the utility of pulse oximetry in the management of patients with leptospirosis, although intuitively it would appear to be well suited to the resource-limited settings where most cases of leptospirosis are seen [2,53,54]. This may be a focus for future studies.

AKI is another classic manifestation of severe leptospirosis that is associated with significant morbidity and mortality [14,55,56]. Laboratory evidence of renal involvement—most commonly an elevated serum creatinine—had prognostic utility in 16 studies. Meanwhile the bedside finding of oliguria—more suitable to settings where there is limited laboratory support—predicted a more complicated disease course in 8 studies. It is important to recognise AKI promptly as it is life-threatening and can evolve rapidly, but it can be successfully treated with—an often short course of—RRT, which may require early transfer to a referral centre [1,36,57,58]. Hypotension—one of the five so-called “vital signs” which can be measured at presentation and followed sequentially—was also frequently of prognostic value. This also has a simple remedy in the form of cautious fluid resuscitation and early vasopressor support [4,35,36]. If hypotension is recognised and addressed promptly, adverse sequelae can be minimised [59].

For many clinicians, the perception persists that severe leptospirosis is characterised by jaundice; indeed severe leptospirosis is commonly referred to as icteric leptospirosis (or Weil’s disease) in the literature [1,60]. Hepatic involvement (jaundice, deranged liver function tests or hepatomegaly) was a predictor of severe disease in every European study in our review; however, it is assuredly the case that patients with life-threatening leptospirosis are not always icteric [6,61]. In Australia, for instance, less than 10% of patients with severe leptospirosis have jaundice [41,42,57]. The explanation for this apparent geographical heterogeneity in the clinical phenotype of severe leptospirosis is likely to be multifactorial, but it may be at least partly explained by variation in the locally prevalent serovars. Infection with Leptospira interrogans serogroup Icterohaemorrhagiae was associated with severe disease in studies from Martinique (where 75% of the patients with severe disease had jaundice) and New Caledonia (where over 85% of patients with severe disease had jaundice) [32,43]. In contrast, serovars from the Pyrogenes, Australis and Sejroe serogroups are identified most commonly in tropical Australia where jaundice is uncommon in patients with severe disease [57,62].

But it is important to note that icteric patients with leptospirosis also frequently have hypotension, respiratory involvement and AKI, and it is these complications—not the hepatic dysfunction—that are most commonly responsible for patient death [16,30,32,43,47,63]. These three variables have been incorporated into the SPiRO score, a simple disease severity score that has been devised in Australia [41]. One of the advantages of the SPiRO score is that its three elements—systolic blood pressure < 100 mmHg, abnormal auscultatory findings on respiratory examination and oliguria—can be determined at the bed side in resource-limited settings by even junior health workers in less than a minute. An absence of any of the three clinical variables of the SPiRO score at presentation had a negative predictive value for the subsequent development of severe disease of 97%. The score was derived in tropical Australia’s well-resourced heath system and requires validation in other settings but our review suggests that it may have greater global utility—and be easier to use in clinical practice—than the Brazilian QuickLepto score, another score devised to predict death in leptospirosis patients at hospital admission [28]. The QuickLepto score has prognostic utility, but has five variables and requires the haematocrit which may not be accessible as rapidly in the locations where leptospirosis is most commonly seen [2,28].

However, an important caveat to consider when assessing the clinical utility of the SPiRO and the QuickLepto scores is that they were derived from cohorts of patients with an established diagnosis of leptospirosis [1]. While epidemiological and clinical findings may lead health workers to suspect leptospirosis in a patient—and in many high-incidence settings the majority of patients will have leptospirosis suspected at presentation—the actual diagnosis is often not confirmed for several days, even in high-income settings [1,57]. The clinical and laboratory findings that are suggestive of leptospirosis can also be seen in patients with many other infections encountered in rural and remote tropical settings, including dengue, malaria, Q fever and rickettsial disease, and it is unwise to use a prediction score developed for patients with leptospirosis in a patient who may have a quite different condition [64,65,66,67]. This limits the practical applicability of the leptospirosis-specific scores which, perhaps relevantly, have not been shown to be better at identifying patients at risk of deterioration than commonly used prediction scores such as the National Early Warning Score 2 (NEWS2), the Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (SIRS) score and the Universal Vital Assessment (UVA) score [68,69,70,71,72]. As hypotension and respiratory involvement are associated with poorer outcomes in patients with leptospirosis, it might be anticipated that these validated, simple disease severity scores will also assist the triage of patients with leptospirosis, well before their diagnosis is established. The relative utility of commonly used general scores (like NEWS2, SIRS and UVA) and leptospirosis-specific scores (like SPiRO, THAI-LEPTO and QuickLepto) in resource-limited settings where the diagnosis of leptospirosis is not confirmed should be a focus of future studies [24].

Our study has many limitations. While we did our best to identify as many relevant studies as possible, it is likely that we have missed some, particularly those that were not published in English. The definition of severe disease—and the prognostic factors that were examined in each of the reports—was not standardised, although we do not feel that this would necessarily change the main findings of our report. This methodological flexibility also allowed us to compare cohorts managed in different health systems where there may be differences in access to care and the advanced critical care support that sometimes may be necessary for survival. While cardiac involvement and altered consciousness were not identified as common predictors of severe disease, both of these findings are associated with a higher risk of mortality and should always be sought in a patient in whom leptospirosis is a possible diagnosis [7,73]. As ever, patient management should always be informed by thoughtful and repeated clinical assessment and tailored to the individual patient and the health system in which they are managed [74]. Our report had a biomedical focus and did not examine the social determinants of health and their role in disease outcomes, although they undoubtedly contribute [75,76,77,78]. We also did not examine pathogen-related factors such as the infecting serovar, although it is only possible to determine this in regions with access to advanced laboratory support and this information is not available in a timely enough manner to inform patient triage and clinical care, which were the focus of this study [1,48]. Importantly, serologic analysis—which is most commonly used to infer the infecting serovar—has poor sensitivity and specificity for the identification of the infecting serovar in individual cases of leptospirosis in humans and have not been shown to have a role in the management of patients with the disease [65,79].

In future prospective studies, it will be important to define the relative contributions of host, pathogen and environmental factors to the clinical phenotype of leptospirosis. This will also provide important insights into the pathophysiology of severe leptospirosis and the utility of different adjunctive therapies. It will be important to define, in particular, the independent contribution of the responsible serovar for the patients’ clinical phenotype and how much this explains the variation in the clinical presentation that exists across regions [80]. There is growing interest in the prognostic utility of quantitative PCR in leptospirosis as well as a range of biomarkers including plasma neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) and long pentraxins [32,43,81,82]. The relationship between these variables, clinical phenotypes and patient outcomes will also provide greater insights into the pathophysiology and the optimal therapy of severe leptospirosis which remains incompletely defined [83,84,85,86,87]. More practically, it is also important to determine the independent contribution of access to quality care and time to presentation on disease severity and outcomes [15,17,31,43]. Finally, it remains to be seen whether the identification and management of the high-risk patient with leptospirosis is substantially different to the management of patients with other serious infections [59,88].

5. Conclusions

A range of simple clinical and laboratory indices can identify the patient with leptospirosis who is at greatest risk of deterioration. Although there is some geographical variation in the clinical phenotype of severe leptospirosis, the presence of hypotension, respiratory involvement and renal involvement have been repeatedly associated with severe disease across diverse populations. Thorough assessment of patients to identify these findings in patients with suspected leptospirosis should expedite recognition of the patients at greatest risk of deterioration and encourage the clinician to consider escalation of their care. Importantly, these manifestations can be identified rapidly and inexpensively in the resource-limited settings where patients with leptospirosis are most commonly seen, enabling the prompt delivery of optimal supportive care for this life-threatening infection.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/pathogens14121268/s1, Supplementary File S1: Database Search strategy. Supplementary File S2: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA). Supplementary File S3: Risk of bias assessment using the Newcastle-Ottawa score.

Author Contributions

Conception and design initiated by J.H. and S.S. Research question, methods, results interpretation and manuscript writing completed by P.R. and J.H. Data collection and data analysis by P.R., L.J., J.H. and S.S. Article drafted and revised critically for intellectual content and final approval of the version to be published by P.R., J.H., S.S. and I.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

As this is a scoping review, it did not require ethical approval.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the Far North Queensland Human Research Ethics Committee. (contact via email fnq_hrec@health.qld.gov.au) for researchers who meet the criteria for access.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Stephen Anderson and Zinat Mohammadpour for their invaluable assistance during the manuscript’s preparation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| aPTT | activated partial thromboplastin time |

| AKI | Acute Kidney Injury |

| ALT | Alanine transaminase |

| AST | Aspartate aminotransferase |

| CKD | Chronic kidney Disease |

| FBC | Full blood count |

| Hb | Haemoglobin |

| ICU | Intensive Care unit |

| IU | International units |

| LFTs | Liver function tests |

| NEWS2 | National Early Warning Score 2 |

| PCV | Packed Cell Volume |

| PT | Prothrombin time |

| RRT | renal replacement therapy |

| SIRS | Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome |

| SGOT | Serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase |

| SOFA | Sequential organ failure assessment |

| UECs | Urea electrolytes and creatinine |

| ULN | upper limit of normal |

| UVA | Universal Vital Assessment |

| WBC | White blood cell |

References

- Rajapakse, S.; Fernando, N.; Dreyfus, A.; Smith, C.; Rodrigo, C. Leptospirosis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2025, 11, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, F.; Hagan, J.E.; Calcagno, J.; Kane, M.; Torgerson, P.; Martinez-Silveira, M.S.; Stein, C.; Abela-Ridder, B.; Ko, A.I. Global Morbidity and Mortality of Leptospirosis: A Systematic Review. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2015, 9, e0003898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, V.; Trivedi, T.H.; Yeolekar, M.E. Epidemic of leptospirosis: An ICU experience. J. Assoc. Physicians India 2004, 52, 619–622. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, S.; Liu, Y.H.; Carter, A.; Kennedy, B.J.; Dermedgoglou, A.; Poulgrain, S.S.; Paavola, M.P.; Minto, T.L.; Luc, M.; Hanson, J. Severe leptospirosis in tropical Australia: Optimising intensive care unit management to reduce mortality. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2019, 13, e0007929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katz, A.R.; Ansdell, V.E.; Effler, P.V.; Middleton, C.R.; Sasaki, D.M. Assessment of the clinical presentation and treatment of 353 cases of laboratory-confirmed leptospirosis in Hawaii, 1974–1998. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2001, 33, 1834–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, S.J.; Tsai, C.C.; Holmes, K.; Fresh, J.W.; Watten, R.H. Sporadic anicteric leptospirosis in South Vietnam. A study in 150 patients. Ann. Intern. Med. 1973, 79, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, A.I.; Reis, M.G.; Dourado, C.M.R.; Johnson, W.D., Jr.; Riley, L.W. Urban epidemic of severe leptospirosis in Brazil. Salvador Leptospirosis Study Group. Lancet 1999, 354, 820–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, G.A.; Shea, B.; O’Connell, D.; Peterson, J.; Welch, V.; Losos, M.; Tugwell, P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomized Studies in Meta-Analysis; Ottawa Hospital Research Institute: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Patra, J.; Bhatia, M.; Suraweera, W.; Morris, S.K.; Patra, C.; Gupta, P.C.; Jha, P. Exposure to second-hand smoke and the risk of tuberculosis in children and adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 18 observational studies. PLoS Med. 2015, 12, e1001835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwannarong, K.; Singhasivanon, P.; Chapman, R.S. Risk factors for severe leptospirosis of Khon Kaen Province: A case-control study. J. Health Res. 2014, 28, 59–64. [Google Scholar]

- Al Hariri, Y.K.; Sulaiman, S.A.S.; Khan, A.H.; Adnan, A.S.; Al-Ebrahem, S.Q. Determinants of prolonged hospitalization and mortality among leptospirosis patients attending tertiary care hospitals in northeastern state in peninsular Malaysia: A cross sectional retrospective analysis. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 887292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pongpan, S.; Thanatrakolsri, P.; Vittaporn, S.; Khamnuan, P.; Daraswang, P. Prognostic Factors for Leptospirosis Infection Severity. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2023, 8, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandhu, R.S.; Ismail, H.B.; Ja’afar, M.H.B.; Rampal, S. The Predictive Factors for Severe Leptospirosis Cases in Kedah. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2020, 5, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajapakse, S.; Weeratunga, P.; Niloofa, M.R.; Fernando, N.; Rodrigo, C.; Maduranga, S.; Fernando, N.L.; de Silva, H.J.; Karunanayake, L.; Handunnetti, S. Clinical and laboratory associations of severity in a Sri Lankan cohort of patients with serologically confirmed leptospirosis: A prospective study. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2015, 109, 710–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, N.; Kitashoji, E.; Koizumi, N.; Lacuesta, T.L.V.; Ribo, M.R.; Dimaano, E.M.; Saito, N.; Suzuki, M.; Ariyoshi, K.; Parry, C.M. Building prognostic models for adverse outcomes in a prospective cohort of hospitalised patients with acute leptospirosis infection in the Philippines. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2017, 111, 531–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panaphut, T.; Domrongkitchaiporn, S.; Thinkamrop, B. Prognostic factors of death in leptospirosis: A prospective cohort study in Khon Kaen, Thailand. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2002, 6, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, R.P.; Goswami, R.P.; Basu, A.; Tripathi, S.K.; Chakrabarti, S.; Chattopadhyay, I. Predictors of mortality in leptospirosis: An observational study from two hospitals in Kolkata, eastern India. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2014, 108, 791–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Liang, H.; Yi, R.; Xiao, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Chang, Q.; Zhou, L.; Liu, B.; He, J.; Liu, T.; et al. Clinical characteristics and prognosis of patient with leptospirosis: A multicenter retrospective analysis in south of China. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 1014530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseka, C.L.; Dahanayake, N.J.; Mihiran, D.J.; Wijesinghe, K.M.; Liyanage, L.N.; Wickramasuriya, H.S.; Wijayaratne, G.B.; Sanjaya, K.; Bodinayake, C.K. Pulmonary haemorrhage as a frequent cause of death among patients with severe complicated Leptospirosis in Southern Sri Lanka. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2023, 17, e0011352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philip, N.; Lung Than, L.T.; Shah, A.M.; Yuhana, M.Y.; Sekawi, Z.; Neela, V.K. Predictors of severe leptospirosis: A multicentre observational study from Central Malaysia. BMC Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisansala, G.G.T.; Weerasekera, M.; Ranasinghe, N.; Gamage, C.; Marasinghe, C.; Fernando, N.; Gunasekara, C. Predictors of severe leptospirosis on admission: A Sri Lankan study. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2023, 134, S18–S19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.K.; Lee, M.H.; Chen, Y.C.; Hsueh, P.R.; Chang, S.C. Factors associated with severity and mortality in patients with confirmed leptospirosis at a regional hospital in northern Taiwan. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2020, 53, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budiono, E.; Riyanto, B.S.; Hisyam, B.; Hartopo, A.B. Pulmonary involvement predicts mortality in severe leptospirosis patients. Acta Medica Indones. 2009, 41, 11–14. [Google Scholar]

- Ajjimarungsi, A.; Bhurayanontachai, R.; Chusri, S. Clinical characteristics, outcomes, and predictors of leptospirosis in patients admitted to the medical intensive care unit: A retrospective analysis. J. Infect. Public Health 2020, 13, 2055–2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, A.F.D.; Figueiredo, K.; Falcão, I.W.; Costa, F.A.; da Rocha Seruffo, M.C.; de Moraes, C.C.G. Study of machine learning techniques for outcome assessment of leptospirosis patients. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 13929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daher, E.D.F.; Soares, D.D.S.; Galdino, G.S.; Macedo, Ê.S.; Gomes, P.E.A.D.C.; Pires Neto, R.D.J.; da Silva, G.B., Jr. Leptospirosis in the elderly: The role of age as a predictor of poor outcomes in hospitalized patients. Pathog. Glob. Health 2019, 113, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spichler, A.S.; Vilaça, P.J.; Athanazio, D.A.; Albuquerque, J.O.; Buzzar, M.; Castro, B.; Seguro, A.; Vinetz, J.M. Predictors of lethality in severe leptospirosis in urban Brazil. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2008, 79, 911–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galdino, G.S.; de Sandes-Freitas, T.V.; de Andrade, L.G.M.; Adamian, C.M.C.; Meneses, G.C.; da Silva, G.B., Jr.; de Francesco Daher, E. Development and validation of a simple machine learning tool to predict mortality in leptospirosis. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 4506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Francesco Daher, E.; Soares, D.S.; de Menezes Fernandes, A.T.B.; Girão, M.M.V.; Sidrim, P.R.; Pereira, E.D.B.; Rocha, N.A.; da Silva, G.B., Jr. Risk factors for intensive care unit admission in patients with severe leptospirosis: A comparative study according to patients’ severity. BMC Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marotto, P.C.; Ko, A.I.; Murta-Nascimento, C.; Seguro, A.C.; Prado, R.R.; Barbosa, M.C.; Cleto, S.A.; Eluf-Neto, J. Early identification of leptospirosis-associated pulmonary hemorrhage syndrome by use of a validated prediction model. J. Infect. 2010, 60, 218–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann-Storck, C.; Saint Louis, M.; Foucand, T.; Lamaury, I.; Deloumeaux, J.; Baranton, G.; Simonetti, M.; Sertour, N.; Nicolas, M.; Salin, J.; et al. Severe leptospirosis in hospitalized patients, Guadeloupe. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2010, 16, 331–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochedez, P.; Theodose, R.; Olive, C.; Bourhy, P.; Hurtrel, G.; Vignier, N.; Mehdaoui, H.; Valentino, R.; Martinez, R.; Delord, J.M.; et al. Factors Associated with Severe Leptospirosis, Martinique, 2010–2013. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2015, 21, 2221–2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharp, T.M.; Rivera García, B.; Pérez-Padilla, J.; Galloway, R.L.; Guerra, M.; Ryff, K.R.; Haberling, D.; Ramakrishnan, S.; Shadomy, S.; Blau, D.; et al. Early Indicators of Fatal Leptospirosis during the 2010 Epidemic in Puerto Rico. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2016, 10, e0004482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupont, H.; Dupont-Perdrizet, D.; Perie, J.L.; Zehner-Hansen, S.; Jarrige, B.; Daijardin, J.B. Leptospirosis: Prognostic factors associated with mortality. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1997, 25, 720–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miailhe, A.F.; Mercier, E.; Maamar, A.; Lacherade, J.C.; Le Thuaut, A.; Gaultier, A.; Asfar, P.; Argaud, L.; Ausseur, A.; Ben Salah, A.; et al. Severe leptospirosis in non-tropical areas: A nationwide, multicentre, retrospective study in French ICUs. Intensive Care Med. 2019, 45, 1763–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmas, B.; Jabot, J.; Chanareille, P.; Ferdynus, C.; Allyn, J.; Allou, N.; Raffray, L.; Gaüzere, B.A.; Martinet, O.; Vandroux, D. Leptospirosis in ICU: A Retrospective Study of 134 Consecutive Admissions. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 46, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petakh, P.; Isevych, V.; Griga, V.; Kamyshnyi, A. The risk factors of severe leptospirosis in the Transcarpathian region of Ukraine—Search for “red flags”. Arch. Balk. Med. Union. 2022, 57, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gancheva, G. Age as prognostic factor in leptospirosis. Ann. Infect. Dis. Epidemiol. 2016, 1, 1006. [Google Scholar]

- Esen, S.; Sunbul, M.; Leblebicioglu, H.; Eroglu, C.; Turan, D. Impact of clinical and laboratory findings on prognosis in leptospirosis. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2004, 134, 347–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abgueguen, P.; Delbos, V.; Blanvillain, J.; Chennebault, J.M.; Cottin, J.; Fanello, S.; Pichard, E. Clinical aspects and prognostic factors of leptospirosis in adults. Retrospective study in France. J. Infect. 2008, 57, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.; Kennedy, B.J.; Dermedgoglou, A.; Poulgrain, S.S.; Paavola, M.P.; Minto, T.L.; Luc, M.; Liu, Y.H.; Hanson, J. A simple score to predict severe leptospirosis. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2019, 13, e0007205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craig, S.B.; Graham, G.C.; Burns, M.A.; Dohnt, M.F.; Smythe, L.D.; McKay, D.B. Haematological and clinical-chemistry markers in patients presenting with leptospirosis: A comparison of the findings from uncomplicated cases with those seen in the severe disease. Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 2009, 103, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tubiana, S.; Mikulski, M.; Becam, J.; Lacassin, F.; Lefèvre, P.; Gourinat, A.C.; Goarant, C.; d’Ortenzio, E. Risk factors and predictors of severe leptospirosis in New Caledonia. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2013, 7, e1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikulski, M.; Boisier, P.; Lacassin, F.; Soupé-Gilbert, M.E.; Mauron, C.; Bruyère-Ostells, L.; Bonte, D.; Barguil, Y.; Gourinat, A.C.; Matsui, M.; et al. Severity markers in severe leptospirosis: A cohort study. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2014, 34, 687–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puca, E.; Pipero, P.; Harxhi, A.; Abazaj, E.; Gega, A.; Puca, E.; Akshija, I. The role of gender in the prevalence of human leptospirosis in Albania. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2018, 12, 150–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petakh, P.; Kamyshnyi, O. Oliguria as a diagnostic marker of severe leptospirosis: A study from the Transcarpathian region of Ukraine. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1467915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajapakse, S.; Rodrigo, C.; Haniffa, R. Developing a clinically relevant classification to predict mortality in severe leptospirosis. J. Emerg. Trauma. Shock. 2010, 3, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sykes, A.; Smith, S.; Stratton, H.; Staples, M.; Rosengren, P.; Brischetto, A.; Vincent, S.; Hanson, J. Lung Involvement in Patients with Leptospirosis in Tropical Australia; Associations, Clinical Course and Implications for Management. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2025, 10, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolhnikoff, M.; Mauad, T.; Bethlem, E.P.; Carvalho, C.R. Leptospiral pneumonias. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 2007, 13, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicodemo, A.C.; Duarte, M.I.; Alves, V.A.; Takakura, C.F.; Santos, R.T.; Nicodemo, E.L. Lung lesions in human leptospirosis: Microscopic, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural features related to thrombocytopenia. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1997, 56, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, L.; Rodrigues, A.C.; Sanches, T.R., Jr.; Souza, R.B.; Seguro, A.C. Leptospirosis leads to dysregulation of sodium transporters in the kidney and lung. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 2007, 292, F586–F592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, J.D.; Semler, M.W.; Rice, T.W. Fluid Management in Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2019, 40, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jubran, A. Pulse oximetry. Crit. Care 2015, 19, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbert, L.J.; Wilson, I.H. Pulse oximetry in low-resource settings. Breathe 2012, 9, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daher, E.D.F.; Abreu, K.L.S.D.; da Silva, G.B., Jr. Leptospirosis-associated acute kidney injury. J. Bras. Nefrol. 2010, 32, 408–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, A.; Kumar, T.P.; Vinod, K.S.; Boodman, C.; Bhat, R.; Ravindra, P.; Chaudhuri, S.; Shetty, S.; Shashidhar, V.; Prabhu, A.R.; et al. Kidney involvement in leptospirosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Infection 2025, 53, 785–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratton, H.; Rosengren, P.; Kinneally, T.; Prideaux, L.; Smith, S.; Hanson, J. Presentation and Clinical Course of Leptospirosis in a Referral Hospital in Far North Queensland, Tropical Australia. Pathogens 2025, 14, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade, L.; Cleto, S.; Seguro, A.C. Door-to-dialysis time and daily hemodialysis in patients with leptospirosis: Impact on mortality. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2007, 2, 739–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, L.; Rhodes, A.; Alhazzani, W.; Antonelli, M.; Coopersmith, C.M.; French, C.; Machado, F.R.; Mcintyre, L.; Ostermann, M.; Prescott, H.C.; et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: International guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock 2021. Intensive Care Med. 2021, 49, e1063–e1143. [Google Scholar]

- Day, N.P.J. Leptospirosis: Epidemiology, Microbiology, Clinical Manifestations, and Diagnosis. UpToDate [Internet]. 2025. Available online: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/leptospirosis-epidemiology-microbiology-clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Trevejo, R.T.; Rigau-Pérez, J.G.; Ashford, D.A.; McClure, E.M.; Jarquín-González, C.; Amador, J.J.; de los Reyes, J.O.; Gonzalez, A.; Zaki, S.R.; Shieh, W.J.; et al. Epidemic leptospirosis associated with pulmonary hemorrhage-Nicaragua, 1995. J. Infect. Dis. 1998, 178, 1457–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smythe, L.; Dohnt, M.; Norris, M.; Symonds, M.; Scott, J. Review of leptospirosis notifications in Queensland 1985 to 1996. Commun. Dis. Intell. 1997, 21, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niwattayakul, K.; Homvijitkul, J.; Niwattayakul, S.; Khow, O.; Sitprija, V. Hypotension, renal failure and pulmonary complications in leptospirosis. Ren. Fail. 2002, 24, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izurieta, R.; Galwankar, S.; Clem, A. Leptospirosis: The “mysterious” mimic. J. Emerg. Trauma. Shock. 2008, 1, 21–33. [Google Scholar]

- Haake, D.A.; Levett, P.N. Leptospirosis in humans. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2015, 387, 65–97. [Google Scholar]

- Price, C.; Smith, S.; Stewart, J.; Hanson, J. Acute Q Fever Patients Requiring Intensive Care Unit Support in Tropical Australia, 2015–2023. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2025, 31, 332–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gavey, R.; Stewart, A.G.A.; Bagshaw, R.; Smith, S.; Vincent, S.; Hanson, J. Respiratory manifestations of rickettsial disease in tropical Australia; Clinical course and implications for patient management. Acta Trop. 2025, 266, 107631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, C.C.; Hazard, R.; Saulters, K.J.; Ainsworth, J.; Adakun, S.A.; Amir, A.; Andrews, B.; Auma, M.; Baker, T.; Banura, P.; et al. Derivation and validation of a universal vital assessment (UVA) score: A tool for predicting mortality in adult hospitalised patients in sub-Saharan Africa. BMJ Glob. Health 2017, 2, e000344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Royal College of Physicians. National Early Warning Score (NEWS) 2: Standardising the Assessment of Acute-Illness Severity in the NHS; Royal College of Physicians: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Minn, M.M.; Aung, N.M.; Zaw, T.T.; Chann, P.N.; Khine, H.E.; McLoughlin, S.; Kelleher, A.D.; Tun, N.L.; Oo, T.Z.C.; Myint, N.P.S.T.; et al. The comparative ability of commonly used disease severity scores to predict death or a requirement for ICU care in patients hospitalised with possible sepsis in Yangon, Myanmar. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 104, 543–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bone, R.C.; Balk, R.A.; Cerra, F.B.; Dellinger, R.P.; Fein, A.M.; Knaus, W.A.; Schein, R.M.; Sibbald, W.J. Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. Am. Coll. Chest Physicians Soc. Crit. Care Med. Chest 1992, 101, 1644–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lal, S.; Luangraj, M.; Keddie, S.H.; Ashley, E.A.; Baerenbold, O.; Bassat, Q.; Bradley, J.; Crump, J.A.; Feasey, N.A.; Green, E.W.; et al. Predicting mortality in febrile adults: Comparative performance of the MEWS, qSOFA, and UVA scores using prospectively collected data among patients in four health-care sites in sub-Saharan Africa and South-Eastern Asia. EClinicalMedicine 2024, 77, 102856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navinan, M.R.; Rajapakse, S. Cardiac involvement in leptospirosis. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2012, 106, 515–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, J.; Patkar, V.; Chronakis, I.; Begent, R. From practice guidelines to clinical decision support: Closing the loop. J. R. Soc. Med. 2009, 102, 464–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felzemburgh, R.D.; Ribeiro, G.S.; Costa, F.; Reis, R.B.; Hagan, J.E.; Melendez, A.X.; Fraga, D.; Santana, F.S.; Mohr, S.; dos Santos, B.L.; et al. Prospective study of leptospirosis transmission in an urban slum community: Role of poor environment in repeated exposures to the Leptospira agent. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2014, 8, e2927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalil, H.; Santana, R.; de Oliveira, D.; Palma, F.; Lustosa, R.; Eyre, M.T.; Carvalho-Pereira, T.; Reis, M.G.; Ko, A.I.; Diggle, P.J.; et al. Poverty, sanitation, and Leptospira transmission pathways in residents from four Brazilian slums. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2021, 15, e0009256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamu, S.; Neela, V. Systematic review of the environmental and socioeconomic factors of leptospirosis transmission. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2023, 130, S139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teles, A.J.; Bohm, B.C.; Silva, S.C.M.; Bruhn, F.R.P. Socio-geographical factors and vulnerability to leptospirosis in South Brazil. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levett, P.N. Leptospirosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2001, 14, 296–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthias, M.A.; Lubar, A.A.; Lanka Acharige, S.S.; Chaiboonma, K.L.; Pilau, N.N.; Marroquin, A.S.; Jayasundara, D.; Agampodi, S.; Vinetz, J.M. Culture-Independent Detection and Identification of Leptospira Serovars. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e02475-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickramasinghe, M.; Chandraratne, A.; Doluweera, D.; Weerasekera, M.M.; Perera, N. Predictors of severe leptospirosis: A review. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2025, 30, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, C.; Roy-Chowdhuri, S. Quantitative Real-Time PCR: Recent Advances. Methods Mol. Biol. 2016, 1392, 161–176. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Zanzi, C.; Dreyfus, A.; Limothai, U.; Foley, W.; Srisawat, N.; Picardeau, M.; Haake, D.A. Leptospirosis—Improving Healthcare Outcomes for a Neglected Tropical Disease. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2025, 12, ofaf035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagliero, J.; Villanueva, S.; Matsui, M. Leptospirosis Pathophysiology: Into the Storm of Cytokines. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2018, 8, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samrot, A.V.; Sean, T.C.; Bhavya, K.S.; Sahithya, C.S.; Chan-Drasekaran, S.; Palanisamy, R.; Robinson, E.R.; Subbiah, S.K.; Mok, P.L. Leptospiral Infection, Pathogenesis and Its Diagnosis—A Review. Pathogens 2021, 10, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evangelista, K.V.; Coburn, J. Leptospira as an emerging pathogen: A review of its biology, pathogenesis and host immune responses. Future Microbiol. 2010, 5, 1413–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petakh, P.; Oksenych, V.; Kamyshnyi, O. Corticosteroid Treatment for Leptospirosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salaveria, K.; Smith, S.; Liu, Y.H.; Bagshaw, R.; Ott, M.; Stewart, A.; Law, M.; Carter, A.; Hanson, J. The Applicability of Commonly Used Severity of Illness Scores to Tropical Infections in Australia. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2021, 106, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).