Abstract

Understanding the diversity of pathogenic microorganisms in wild primates is essential for assessing their health and zoonotic risks. In this study, metagenomic sequencing was applied to investigate the composition and seasonal dynamics of potential pathogenic microorganisms in the feces of François’ langurs. A total of 77 potential pathogenic taxa were identified, mainly belonging to Bacillota and Pseudomonadota. The most abundant genera were Streptococcus, Staphylococcus, Salmonella, Listeria, and Pseudomonas, while dominant species included Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Salmonella enterica, Listeria monocytogenes, and Escherichia coli. Significant seasonal differences were detected in both α- and β-diversity indices, with higher microbial diversity in spring and distinct community structures across seasons. Several genera and species, including Vibrio, Chlamydia, Mycobacteroides, Vibrio cholerae, Yersinia enterocolitica, Chlamydia trachomatis, and Mycobacteroides abscessus, showed marked seasonal fluctuations. The findings reveal that the pathogenic microbial community of François’ langurs is strongly shaped by seasonal environmental factors. The detection of multiple zoonotic pathogens suggests a potential risk of cross-species transmission, providing valuable baseline data for primate disease ecology and conservation health management.

1. Introduction

Diseases are major factors influencing the survival, reproduction, and long-term viability of wildlife populations [1,2]. Wild animals are susceptible to a wide range of pathogens, including viruses, bacteria, fungi, and parasites [3,4]. These pathogens can be transmitted through the fecal-oral route, posing potential risks to both wildlife and human health. Studies have identified zoonotic pathogens such as Salmonella spp., Escherichia coli, and Giardia spp. in the feces of various wildlife species [5,6,7]. Non-human primates are of particular interest due to their close genetic relationship with humans, which facilitates the potential transmission of pathogens between species [8,9]. The findings underscore the importance of monitoring fecal pathogens in primate populations to assess health risks and inform conservation and public health strategies. Previous research has documented the presence of several zoonotic pathogens in the feces of wild primates, including enteric bacteria (Salmonella spp., Escherichia coli), protozoan parasites (Giardia spp., Cryptosporidium spp., Entamoeba sp.), and viruses with zoonotic potential (e.g., adenoviruses, simian foamy viruses) [10,11].

Metagenomic sequencing has become a powerful approach for investigating pathogens in wildlife, offering a culture-independent method that enables the simultaneous detection of bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites directly from environmental or fecal samples [12,13,14,15]. Metagenomic sequencing is not only a key tool for pathogen surveillance but also a framework for assessing cross-species transmission risks and ecosystem health. Traditional diagnostic techniques, metagenomics can identify both known and previously uncharacterized microorganisms, thereby broadening our understanding of pathogen diversity and evolution [16,17,18]. Recent applications in wildlife disease ecology have revealed hundreds of novel viral and bacterial taxa from fecal samples of diverse hosts, including herbivores and primates, many of which carry zoonotic potential [19,20]. For primates, metagenomic analyses of feces have uncovered enteric viruses, gut parasites, and microbial dysbiosis associated with anthropogenic disturbance, highlighting both conservation and public health relevance [9,21,22,23].

François’ langur (Trachypithecus francoisi) is a folivorous primate, primarily inhabiting karst limestone forests in southern China and northern Vietnam [24,25]. It is classified as Endangered on the IUCN Red List and as a Class I protected species in China [26] (IUCN, 2023). The habitat of François’ langurs is fragmented and increasingly isolated due to habitat loss and human disturbances [25,27,28]. The Mayanghe National Nature Reserve in Guizhou Province represents one of the most important strongholds for this species in China [24,29,30]. Landscape fragmentation in this region has resulted in highly dispersed habitat patches with complex boundaries, reducing population connectivity and potentially limiting gene flow [31,32]. Seasonal fluctuations in food availability further challenge the health and resilience of these populations [29], with studies indicating that gut microbial diversity varies significantly across seasons, reflecting changes in diet and habitat conditions [33,34]. These insights into habitat and ecological constraints, systematic data on the pathogens and microorganisms carried by wild François’ langurs remain scarce, highlighting a critical knowledge gap for disease surveillance and conservation planning.

In this study, we collected fecal samples from François’ langurs in the Mayanghe National Nature Reserve across four seasons and performed metagenomic sequencing to characterize their gut microbial and pathogenic communities. The objectives were to: (i) identify potential pathogens carried by François’ langurs; (ii) assess seasonal variations in microbial diversity. The findings will provide essential baseline data for monitoring the health of François’ langurs and conservation management of this endangered primate.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Area

This study was carried out in the Mayanghe National Nature Reserve (MNNR) (28°37′30″–28°54′20″ N, 108°3′58″–108°19′45″ E), located in the northeast of Guizhou Province, southwestern China, covering an area of 311.13 km2. The reserve was established in 1987 mainly for the protection of François’ langurs and their karst forest habitat [29]. The altitude ranges from 280 to 1441 m, with a typical subtropical monsoon climate characterized by warm, humid, and rainy conditions and distinct seasonal variation in temperature and precipitation [35]. The vegetation types include evergreen broadleaf forest, coniferous forest, coniferous–broadleaf mixed forest, deciduous broadleaf forest, bamboo forest, and shrubland [36]. Totaling 500–600 individuals, exist in the reserve [37].

2.2. Sample Collection

The study group of François’ langurs consisted of 16 individuals, including 11 adults and 5 infants, inhabiting the southwestern part of MNNR. The langurs are well habituated to human observers. Their natural diet mainly consists of leaves, fruits, flowers, and buds [29]. François’ langurs usually sleep in limestone caves or on cliff platforms and defecate before leaving the site in the morning.

Prior to sampling, the sleeping sites of the langur group were observed and recorded. Fresh fecal samples were collected in the morning under the cliffs after the langurs had left. To minimize duplicate sampling from the same individual, samples were collected at intervals of more than 3 m. Only the inner portion of the feces, which had not been in contact with the external environment, was taken using sterile gloves and germ-free tools such as bamboo skewers. Each sample (3–5 g) was immediately transferred into a sterile, labeled collection tube and preserved in RNAlater solution (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA, USA) to stabilize nucleic acids. Samples were then stored at −80 °C until further processing. Sampling was conducted in October 2023, January 2024, May 2024, and July 2024, representing the four seasons (autumn, winter, spring, and summer). In total, 24 fecal samples were collected for metagenomic analysis, Samples were collected randomly, and individual identity could not be determined in the field; Paired samples from specific individuals were not obtained. The fecal samples used in this study were collected from the same François’ langur group as described in our previously published work [34]. The present study focuses specifically on the seasonal dynamics of pathogenic communities, which were not addressed in the earlier analysis.

2.3. DNA Extraction, Library Preparation, and Sequencing

Genomic DNA (gDNA) was extracted from François’ langur fecal samples using the BIOMICS DNA Microprep Kit (Cat# D4301, Zymo Research, Tustin, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA quality and integrity were assessed by 0.8% agarose gel electrophoresis and an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). DNA concentration was quantified using the PicoGreen dsDNA assay on a Tecan F200 microplate reader [38]. High-quality gDNA was used for library construction with the NEBNext Ultra II DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (Cat# E7645, New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) and NEBNext Multiplex Oligos (Cat# E7600). Fragmentation, end repair, adaptor ligation, and PCR enrichment were carried out following the manufacturer’s protocol. Library quality and fragment size were examined using the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer, and concentrations were determined by quantitative PCR (qPCR). Qualified libraries were sequenced on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform with the NovaSeq 6000 S4 Reagent Kit (300 cycles, Cat# 20039236, Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA), producing 150 bp paired-end reads (PE150). All experiments were conducted under strict quality control to ensure the reliability and reproducibility of metagenomic data.

2.4. Data Processing and Quality Control

Raw reads were quality-filtered using Trimmomaticto remove adapters and low-quality bases [39]. Reads shorter than 100 bp or with average quality scores below Q15 were discarded. A Q15 cutoff was chosen to retain sufficient read coverage for downstream metagenomic assembly and analysis, given the potential fragmentation and variable quality of fecal-derived DNA, while preliminary analyses with a more stringent Q30 cutoff produced highly consistent taxonomic and functional profiles. To eliminate host contamination, filtered reads were aligned to the François’ langur reference genome using BWA (version 0.7.19) [40], and unmapped reads were retained with SAMtools for downstream analyses [41]. Clean reads were assembled de novo using SPAdes (v3.15.3) in metagenomic mode [42], and assembly quality was evaluated with QUAST (v5.0.2) [43]. Open reading frames (ORFs) were predicted using Prodigal (v2.6.3) [44].

2.5. Gene Catalog Construction and Functional Annotation

Predicted genes from all samples were clustered into a non-redundant gene catalog using MMseqs2 (version 15.6f452) with 95% sequence identity and 90% alignment coverage thresholds [45]. The longest sequence in each cluster was selected as the representative. Quality-filtered reads were mapped to the catalog using BBMap (version 39.01), and gene abundances were normalized as TPM or RPKM values [46]. Representative genes were annotated against multiple databases, including NR, UniProt, KEGG, CAZy CARD, VFDB, and PHI-base, to explore microbial diversity, functional profiles, and potential pathogenicity [47,48].

2.6. Microbial Diversity and Statistical Analysis

Taxonomic and diversity analyses were performed in R (v4.0.5). Alpha diversity indices were calculated using the vegan and picante packages, and group comparisons were tested with the Wilcoxon rank-sum test and agricolae for post hoc analysis. Beta diversity was estimated using Bray–Curtis, Jaccard, and UniFrac distances, and visualized via PCA, PCoA, and NMDS. Group differences were assessed with ANOSIM and PERMANOVA (adonis function in vegan). Differentially abundant taxa among seasons were identified using LEfSe (Galaxy platform, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA, USA) [12]. Taxonomic assignments were based on the SILVA 138 database [49], and visualization was completed in R (version 4.2.2) and Python (v3.7.4).

3. Results

3.1. Sequencing Quality

Metagenomic sequencing of 24 François’ langur fecal samples generated ~1.99 billion raw paired-end reads (32.79–54.21 million per sample; Supplementary Table S1). After adapter trimming, Q15 quality filtering (Trimmomatic), and removal of host reads via BWA, 1.98 billion high-quality reads were retained (32.68–54.08 million per sample), ad-dressing reviewer concerns on per-sample read counts. Taxonomic profiles were inferred directly from clean reads using the k-mer–based classifier Kraken2, which provides high-resolution assignments without assembly, explicitly responding to the reviewer’s question on taxonomy determination. For gene prediction and functional annotation, de novo assembly with SPAdes generated 63,766–148,962 contigs per sample (≥1 kb; N50 2.8–11.2 kb; average 4.3 kb). Gene prediction yielded 15.3 million coding sequences, clus-tered into 1.05 million non-redundant genes, forming a comprehensive gene catalog.

3.2. Composition of Potential Pathogenic Microorganisms of François’ langur

Potential pathogenic microorganisms in François’ langur were identified by aligning metagenomic sequencing data against the PHI-base database (http://www.phi-base.org/). After excluding plant and insect pathogens, a total of 77 potential pathogenic microorganisms were detected, spanning 8 Phylum, 13 classes, 25 orders, 38 families, and 49 genuses. In this study, genus and species-level data were selected for subsequent analysis of the composition of pathogenic microorganisms across different samples.

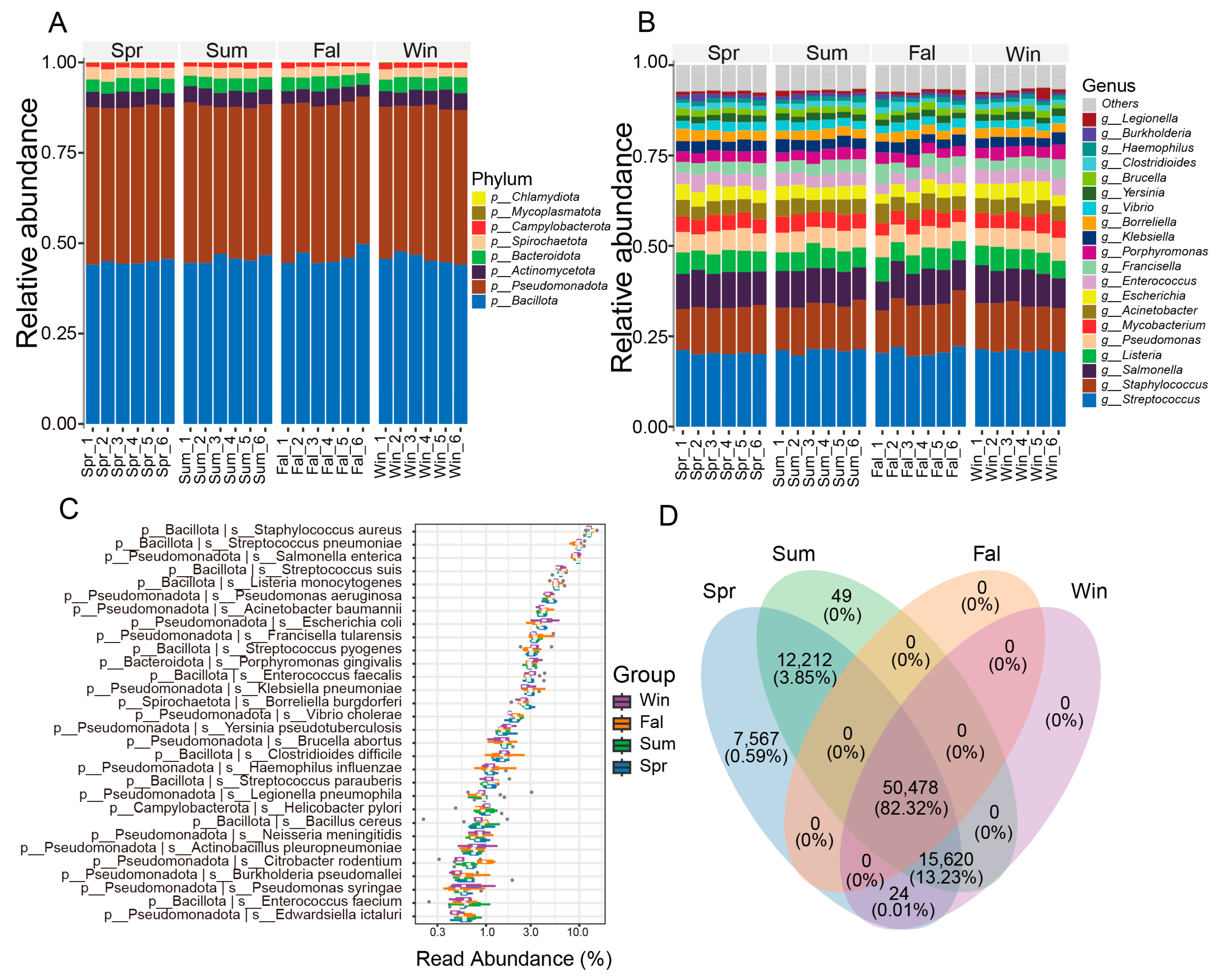

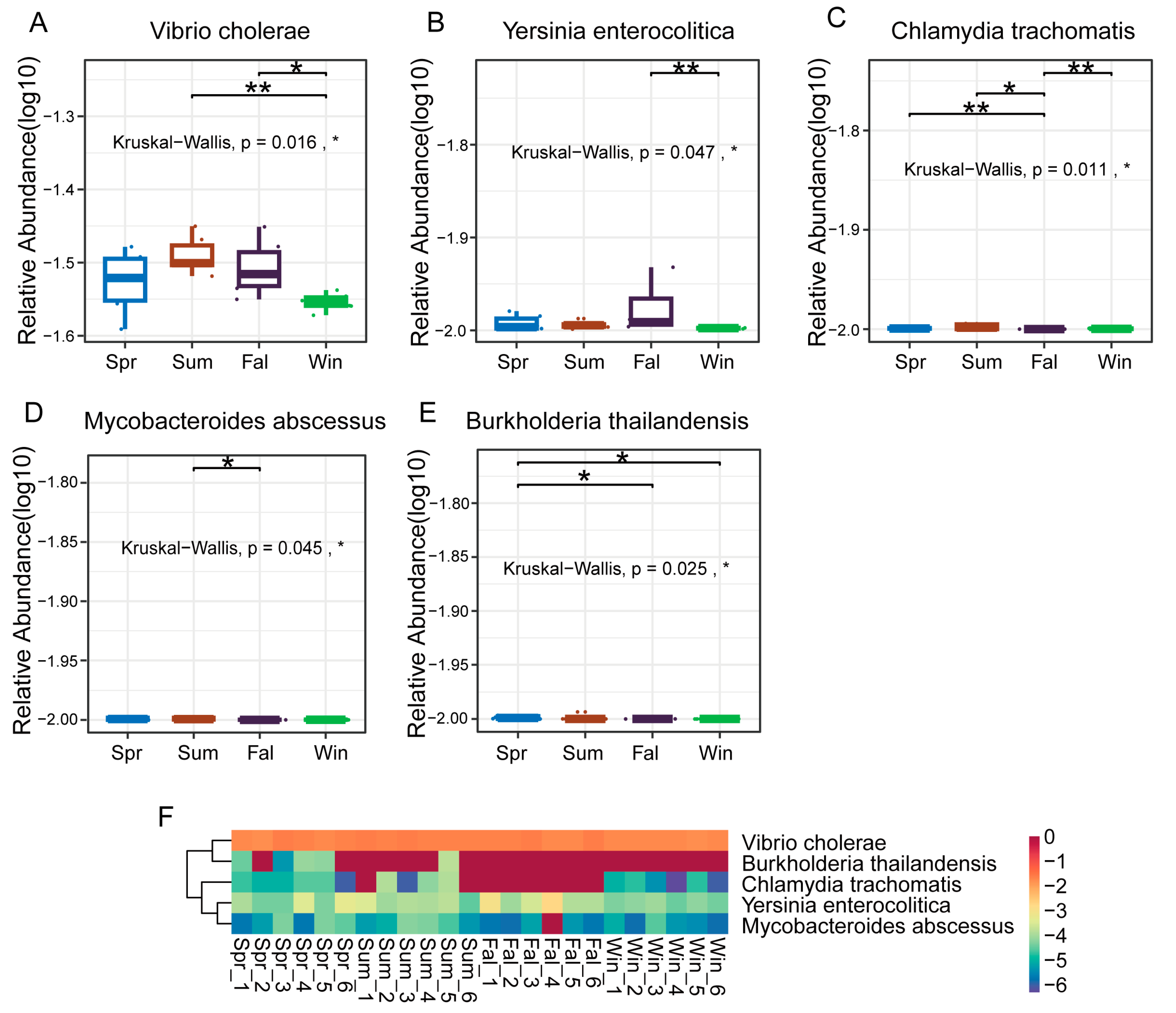

At the phylum level, the pathogenic microorganisms community of François’ langur displayed no seasonal variation (Figure 1A). Bacillota, Pseudomonadota, Actinomycetota, Bacteroidota were the dominant phyla in four seasons. At the genus level, Streptococcus, Staphylococcus, Salmonella, Listeria and Pseudomonas were the top five taxa (Figure 1B). The dominant taxa belonged to Bacillota, mainly Streptococcus, Staphylococcus, Listeria, Enterococcus, and Bacillus, which are common gut or mucosal bacteria with opportunistic pathogenic potential. Members of Pseudomonadota, including Salmonella, Escherichia, Klebsiella, Pseudomonas, and Acinetobacter, were also abundant, reflecting enteric and environmental origins. Other detected genera such as Brucella, Yersinia, Burkholderia, Vibrio, and Haemophilus indicate possible zoonotic relevance.

Figure 1.

Composition and distribution of potential pathogenic microorganisms across seasons. (A) Bar plot showing the relative abundance of major taxa at the phylum level. (B) Bar plot showing the relative abundance of dominant taxa at the genus level. (C) Box plot illustrating the relative abundance of high-abundance pathogenic species among different seasonal groups. (D) Venn diagram showing the numbers of shared and unique OTUs among groups. The numbers represent OTU counts, while the percentages in parentheses indicate the proportion of total sequences contributed by these OTUs relative to the total number of sequences from all OTUs used in this analysis.

At the species level, Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Salmonella enterica, Streptococcus suis, Listeria monocytogenes were the top five species in four seasons (Figure 1C). The community was dominated by members of the phylum Bacillota, including Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Listeria monocytogenes, which are typical opportunistic pathogens causing respiratory and systemic infections in mammals. Other Bacillota species, such as Enterococcus faecalis, E. faecium, and several Streptococcus taxa (S. pyogenes, S. agalactiae, S. suis), were also prevalent. Among Pseudomonadota, Escherichia coli, Salmonella enterica, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa were dominant, reflecting enteric and environmental bacterial sources with known zoonotic potential. Gram-negative pathogens, including Acinetobacter baumannii and Haemophilus influenzae, indicated possible respiratory involvement. Several zoonotic agents, such as Brucella abortus, Leptospira interrogans, and Coxiella burnetii, were detected at lower abundance, implying potential cross-species transmission.

A Venn diagram was generated based on the OTU (Operational Taxonomic Unit) abundance to compare the shared and unique microbial taxa among different seasonal groups (Figure 1D). A total of 50,478 OTUs (82.32%) were shared among all four seasons. Spring contained the highest number of unique OTUs (7567, 0.59%), while no unique OTUs were observed in fall or winter. In addition, 12,212 OTUs (3.85%) were shared between spring and summer, and 15,620 OTUs (13.22%) were shared among spring, summer, and winter. Other combinations contributed negligibly to the total diversity.

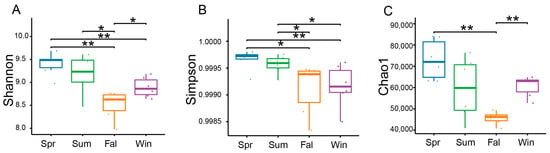

3.3. Analysis of α- and β-Diversity

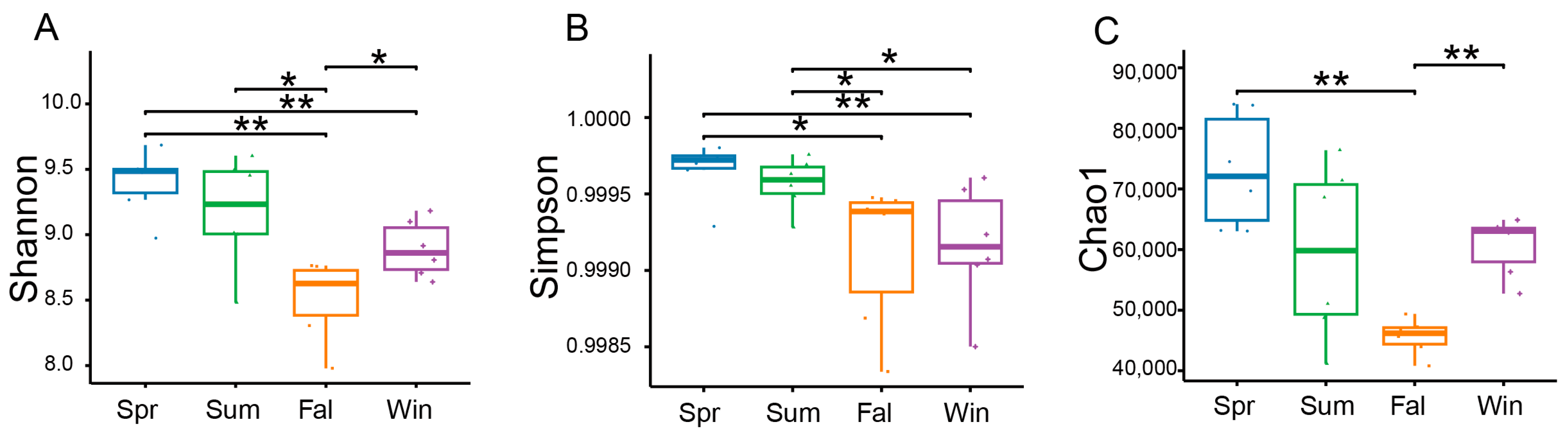

Based on sequencing depth, the potential pathogenic microbial communities exhibited high coverage, four α-diversity indices—including the Shannon index, Simpson index and Chao1—were calculated to assess the diversity and richness of potential pathogenic microorganisms. Seasonal variations in α-diversity were evaluated using linear mixed models. Significant seasonal differences were observed in the α-diversity of potential pathogenic microbial communities. The Shannon index showed clear seasonal fluctuations, with significantly higher diversity in spring samples compared with those collected in fall (Figure 2A). The Simpson index revealed higher diversity in spring relative to fall and winter (Figure 2B). The Chao1 index also varied across seasons, with winter samples exhibiting greater species richness than those from fall (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

Seasonal variation in the α-diversity of potential pathogenic microorganisms in François’ langurs. Box plots illustrating species richness and diversity across samples from different seasons. α-diversity was evaluated using the Shannon (A), Simpson (B), and Chao1 (C). * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 (Wilcoxon rank-sum test).

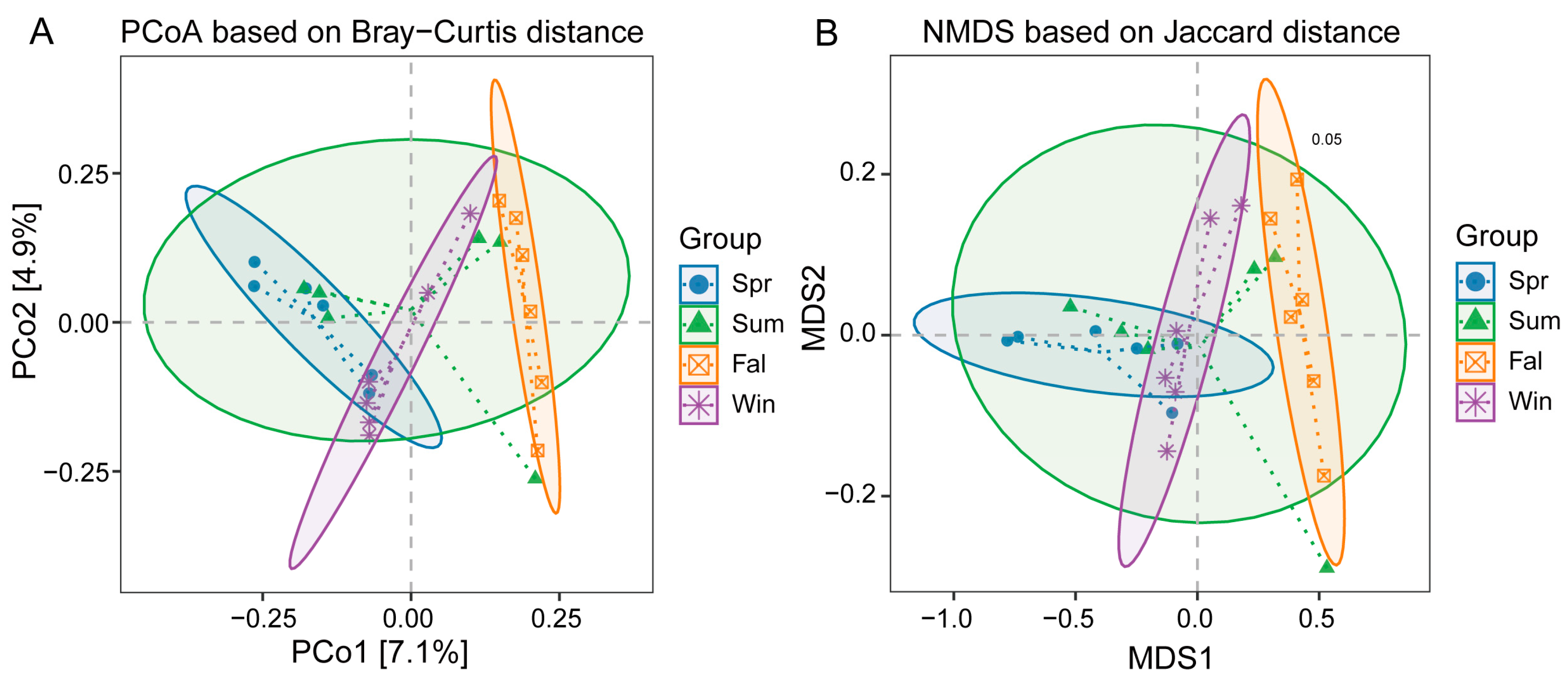

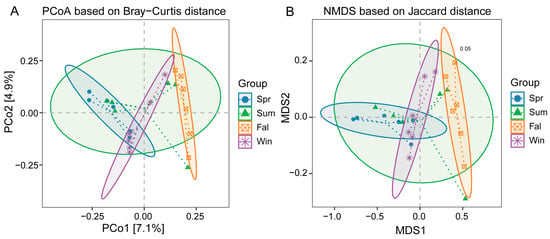

β-diversity analyses were conducted based on species-level relative abundance profiles. Bray–Curtis dissimilarity and both weighted and unweighted UniFrac distance metrics were calculated using QIIME2. Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) showed clear separation among samples from different seasons (Figure 3A). The first two principal coordinates explained 7.1% and 4.9% of the total variation, respectively. Samples from spring and summer clustered closely together, while those from fall and winter were clearly separated, indicating significant seasonal shifts in community composition. The NMDS analysis based on Bray–Curtis distance showed clear separation of microbial communities among the four seasons (Stress = 0.05) (Figure 3B). Spring, summer, fall, and winter samples formed distinct clusters with minimal overlap, indicating strong seasonal variation in community composition.

Figure 3.

β-diversity analysis of potential pathogenic microorganisms in François’ langurs across different seasons. (A) Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) plot based on Bray–Curtis distances among the four seasonal groups. (B) Non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) ordination based on Bray–Curtis distances with group ellipses indicating clustering patterns among seasonal groups.

PERMANOVA results confirmed significant differences in community structure among seasons (Table 1), the composition of potential pathogenic microorganisms differed significantly between spring and fall (R2 = 0.123, p = 0.004), spring and winter (R2 = 0.099, p = 0.023), summer and fall (R2 = 0.099, p = 0.040), fall and winter (R2 = 0.106, p = 0.005). No significant differences were observed between spring and summer (p = 0.069) or summer and winter (p = 0.248).

Table 1.

Results of PERMANOVA (Permutational Multivariate Analysis of Variance) based on Bray–Curtis distance among seasonal groups.

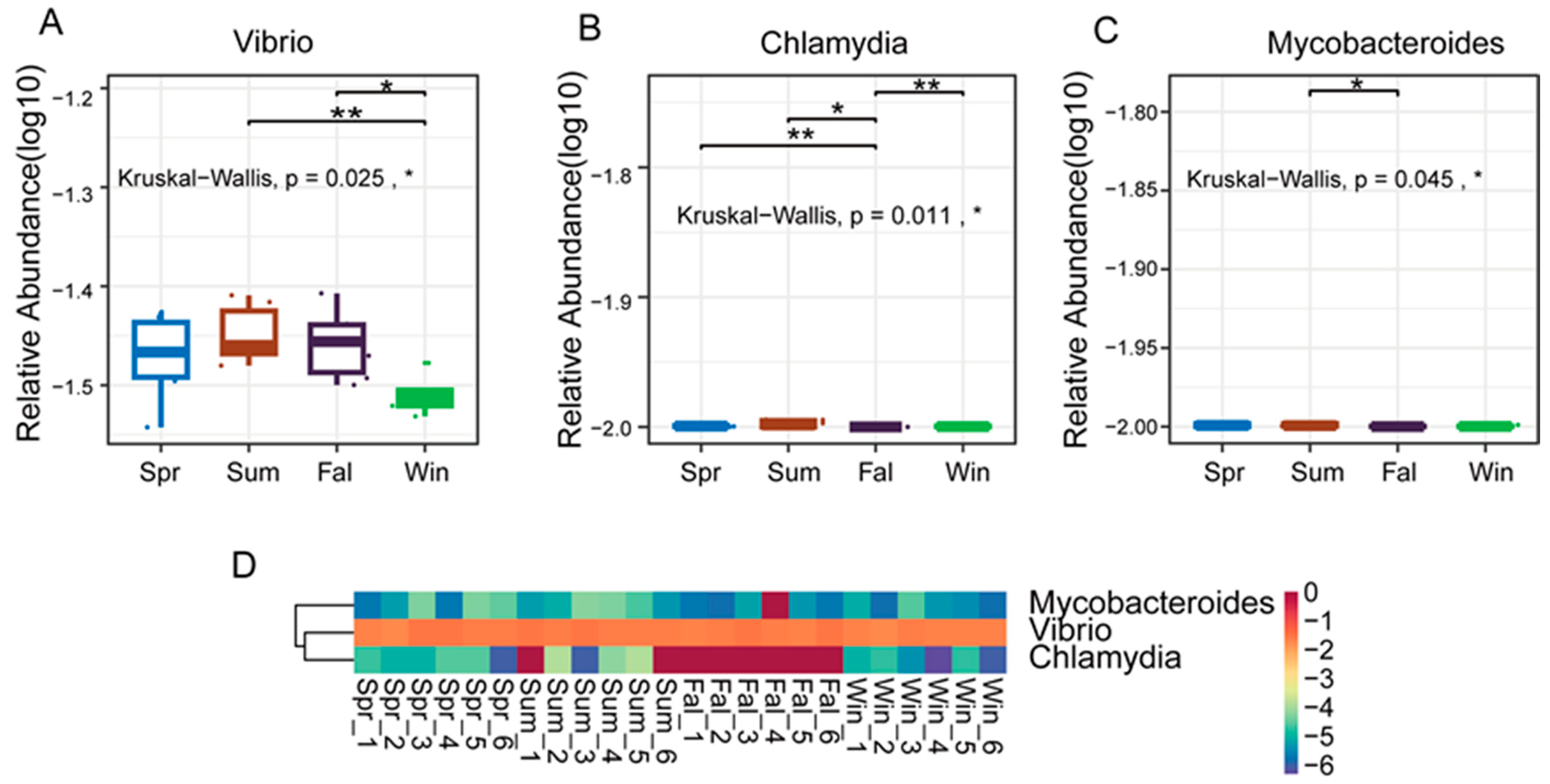

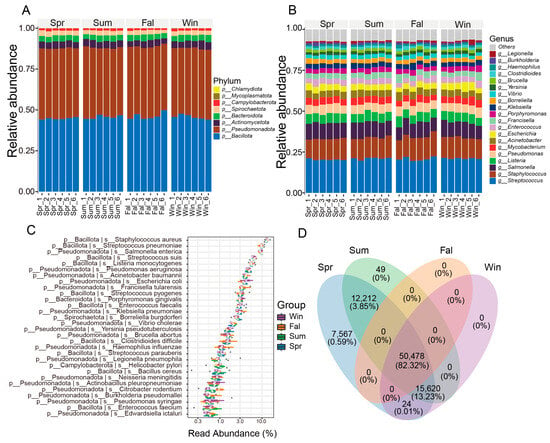

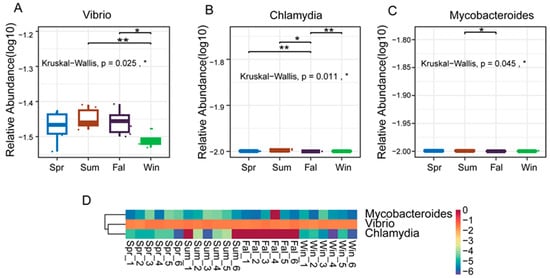

3.4. Differential Species Analysis

The study applied the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis (KW) rank-sum test to evaluate differences in species abundance among groups. Initially, a global KW test was conducted for all species to identify those exhibiting significant overall differences. Subsequently, the top abundant species were subjected to pairwise comparisons between groups. Relative abundance boxplots and heatmaps were generated to visualize the distribution of dominant differential species across groups. At the genus level, three pathogenic genera—Vibrio, Chlamydia, and Mycobacteroides—exhibited significant seasonal differences in relative abundance (p < 0.05). Vibrio showed nearly significant variation between summer and winter (p < 0.01) (Figure 4A), and a significant difference between fall and winter (p < 0.05). Chlamydia displayed nearly significant differences between spring and fall (Figure 4B), fall and winter (p < 0.01), while a significant difference was observed between summer and autumn (p < 0.05). Mycobacteroides demonstrated a significant difference between summer and autumn (p < 0.05). As illustrated in the boxplots and heatmaps (Figure 4C), these genera exhibited distinct seasonal abundance patterns. Vibrio tended to be more abundant in the summer and fall, whereas Chlamydia and Mycobacteroides showed notable fluctuations between transitional and extreme temperature periods.

Figure 4.

Differential analysis of dominant pathogenic genera in François’ langurs across seasons. (A,B,C) Boxplots showing the relative abundance and pairwise seasonal comparisons of the top 10 differential genera. (A) Vibrio, (B) Chlamydia and (C) Mycobanteroides exhibited significant seasonal variation in abundance. (D) Heatmap illustrating the relative abundance patterns of the top 5 differential genera across all samples. Each column represents an individual sample, and each row represents a genus. Color intensity indicates relative abundance levels. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01.

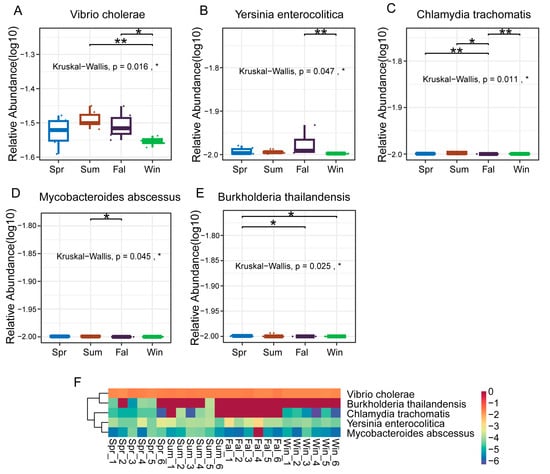

At the species level, five pathogenic species (Vibrio cholerae, Yersinia enterocolitica, Chlamydia trachomatis, Mycobacteroides abscessus, and Burkholderia thailandensis) showed significant seasonal differences in relative abundance. Vibrio cholerae exhibited a significant difference between summer and winter, and between fall and winter (Figure 5A). Yersinia enterocolitica exhibited a highly significant difference between fall and winter (p < 0.01) (Figure 5B). Chlamydia trachomatis showed nearly significant differences between spring and fall, and between autumn and winter (p < 0.01) (Figure 5C), while Mycobacteroides abscessus demonstrated a significant difference between summer and autumn (p < 0.05) (Figure 5D). Boxplots and heatmaps further confirmed these seasonal trends (Figure 5F), indicating that Vibrio cholerae and Yersinia enterocolitica were more abundant in warmer or transitional seasons, whereas Chlamydia trachomatis and Mycobacteroides abscessus fluctuated markedly between seasons.

Figure 5.

Differential analysis of dominant pathogenic species in François’ langurs across seasons. (A–E) Boxplots showing the relative abundance and seasonal differences of the top 10 differential species. (A) Vibrio cholerae, (B) Yersinia enterocolitica, (C) Chlamydia trachomatis, (D) Mycobacteroides abscessus, and (E) Burkholderia thailandensis exhibited significant seasonal variation in relative abundance. (F) Heatmap showing the relative abundance patterns of the top 50 differential species across all samples. Each column represents an individual sample, and each row represents a species. Color intensity indicates relative abundance levels. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01.

4. Discussion

In this study, a rich diversity of pathogenic bacterial genera and species in François’ langurs fecal samples. The dominant genera belonged to Bacillota and Pseudomonadota, mainly Streptococcus, Staphylococcus, Listeria, Enterococcus, Salmonella, Escherichia, Klebsiella, and Pseudomonas. At the species level, notable taxa included Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Escherichia coli, Salmonella enterica, Listeria monocytogenes, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Acinetobacter baumannii, Brucella abortus, Yersinia enterocolitica, Coxiella burnetii, Leptospira interrogans, and Mycobacteroides abscessus. These bacteria are commonly found as gut or mucosal residents but may act as opportunistic pathogens under conditions of physiological stress or immune suppression [50].

The presence of Streptococcus and Staphylococcus genera, especially S. pneumoniae and S. aureus, suggests possible colonization or transmission of respiratory–associated bacteria. Streptococcus is a genus that includes both commensal and pathogenic species and is commonly found in the gastrointestinal tract and on the mucosal surfaces of animals [51,52]. In nonhuman primates, Streptococcus pneumoniae has been reported in some health and disease studies [9,53,54,55]. Lower-abundance genera, including Brucella, Yersinia, Coxiella, and Leptospira, are notable for their role in livestock and wildlife infections. Their detection indicates potential cross-species exposure in shared habitats, highlighting the importance of monitoring primate populations as sentinels for emerging zoonoses.

At both the genus and species levels, Vibrio, Chlamydia, and Mycobacteroides exhibited significant seasonal differences, with Vibrio cholerae and Yersinia enterocolitica being more abundant in warmer or transitional seasons. These patterns are consistent with the known ecology of pathogens, which thrive in humid or nutrient-rich conditions, primates housed in a sanctuary represent an intermediate microbiome state between wild and captive [56,57,58]. Chlamydia trachomatis and Mycobacteroides abscessus showed fluctuations across temperature extremes, possibly related to host immune modulation [59,60]. The presence of these zoonotic bacteria suggests a potential risk of cross-species infection. Although cross-species transmission between humans and macaques is well documented, similar mechanisms may also occur in François’ langurs sharing habitats with humans. Seasonal environmental changes may thus enhance opportunities for pathogen transmission, as observed in other non-human primates and wildlife systems, including wildlife zoonotic and vector-borne EIDs originating at lower latitudes where reporting effort is low [15,61,62]. Continuous surveillance of these pathogens is essential for understanding their ecological drivers and for mitigating potential zoonotic risks to both primate and human health.

Significant seasonal variation was observed in the diversity and composition of potential pathogenic microorganisms in the fecal microbiota of François’ langurs. The higher α-diversity in spring suggests that environmental and dietary factors during this period promote microbial richness, consistent with findings in other wild primates showing seasonal shifts linked to food availability and host physiology [63,64,65,66,67]. β-diversity analyses further revealed clear separation among seasons, indicating that the structure of pathogenic microbial communities changed dynamically over time. These temporal fluctuations likely reflect ecological factors such as temperature, humidity, and resource variation, which can influence bacterial transmission and survival in the environment [68,69,70]. These results reveal distinct seasonal trends in the abundance of key pathogenic genera, implying that shifts in environmental parameters and ecological interactions across different times of the year may play a critical role in shaping pathogen dynamics.

Climatic and ecological factors may influence the occurrence of zoonotic pathogens in wild primates. Seasonal shifts in temperature and resource availability can influence host physiology and gut microbial stability in wild primates. In our study, significant seasonal differences in α- and β-diversity and in the relative abundances of pathogenic taxa (e.g., Vibrio, Chlamydia, Mycobacteroides; Vibrio cholerae, Yersinia enterocolitica, Chlamydia trachomatis) suggest that environmental variation may modulate pathogen dynamics. Climatic stress is known to weaken immune defenses and promote dysbiosis, increasing infection risk. Such instability may affect health and survival in wild primates, especially in species with small or fragmented populations [66,67,71,72].

Given the frequent overlap between François’ langurs habitats and human activity areas, such microbial fluctuations could elevate the risk of cross-species transmission. Seasonal monitoring of pathogen communities can thus provide valuable early indicators of disease emergence and help guide targeted prevention strategies. From a conservation perspective, integrating microbiome-based surveillance into long-term wildlife management programs could enhance early detection of pathogenic threats. Measures such as reducing human–primate contact, maintaining clean water sources, and improving waste management in habitats are essential to minimize zoonotic spillover risks. Microbiome monitoring provides a non-invasive and sensitive tool for assessing ecosystem health, offering new insights for wildlife conservation in changing environments.

Fecal samples were collected from a single social group, and individual identities could not be determined. The findings primarily reflect group-level patterns in pathogen prevalence, while individual-level variation remains to be explored. Future studies incorporating microsatellites or SNP analyses could help reconstruct individual identities and provide more detailed insights. Seasonal changes in food availability and social contact may also vary among groups or years, potentially influencing microbial and pathogen dynamics.

The analyses focused exclusively on DNA-based metagenomics, which allowed characterization of bacterial and DNA viral communities but does not allow conclusions about RNA viruses such as Zika or other arboviruses. Reads shorter than 100 bp or with average quality scores below Q15 were discarded to retain sufficient coverage for metagenomic assembly. Preliminary analyses using a more stringent Q30 cutoff confirmed that taxonomic and functional profiles were highly consistent, supporting the robustness of the results. The study concentrated on bacterial pathogens and excluded plant and insect pathogens, such as Aspergillus and arboviruses, which may also contribute to gut microbial composition. Future work involving multiple groups, long-term sampling, RNA-based analyses, and non-bacterial pathogens will provide a more comprehensive understanding of gut pathogen diversity and seasonal dynamics in François’ langurs.

5. Conclusions

The study presents the first metagenomic characterization of potential pathogenic microorganisms in the fecal microbiota of François’ langurs across four seasons. A total of 77 potential pathogenic taxa were identified, mainly belonging to Bacillota and Pseudomonadota, with Streptococcus, Staphylococcus, Salmonella, Listeria, and Pseudomonas as dominant genera. Both α- and β-diversity analyses revealed clear seasonal variations, with higher microbial diversity in spring and distinct community structures between fall and winter. Several pathogenic taxa, including Vibrio cholerae, Yersinia enterocolitica, Chlamydia trachomatis, and Mycobacteroides abscessus, exhibited marked seasonal fluctuations, reflecting the influence of environmental changes on pathogen dynamics in wild primates. The detection of multiple zoonotic microorganisms highlights the potential risk of cross-species transmission and underscores the need for long-term monitoring to better understand host–microbe–environment interactions and support conservation of endangered primate populations.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/pathogens14121237/s1, Table S1: Summary of metagenomic sequencing data for the 24 François’ langur fecal samples.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.L.; methodology, P.L.; software, D.W.; investigation, P.L. and D.W.; resources, F.Z.; data curation, F.Z., writing—original draft preparation, P.L., writing—review and editing, Q.Z.; visualization, T.W.; project administration, J.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Administration of Mayanghe National Nature Reserve (Grant No. MYH2025-HT027).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study was conducted under the approval of the Administration of Mayanghe National Nature Reserve (Permit No. 202410), with the approval date of 5 October 2023. All fecal samples were collected with permission from the Administration of MNNR.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data in this study have been deposited in the NCBI SAR under accession number PRJNA1335193.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Mayanghe National Nature Reserve Administration for their assistance with data collection and fieldwork.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bailey, J.A.; Eichler, E.E. Primate segmental duplications: Crucibles of evolution, diversity and disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2006, 7, 552–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, B.; Han, S.; He, H. Effect of epidemic diseases on wild animal conservation. Integr. Zool. 2023, 18, 963–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faust, C.L.; Dobson, A.P.; Gottdenker, N.; Bloomfield, L.S.P.; McCallum, H.I.; Gillespie, T.R.; Diuk-Wasser, M.; Plowright, R.K. Null expectations for disease dynamics in shrinking habitat: Dilution or amplification? Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2017, 372, 20160173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fearon, M.L.; Wood, C.L.; Tibbetts, E.A. Habitat quality influences pollinator pathogen prevalence through both habitat-disease and biodiversity-disease pathways. Ecology 2023, 104, e3933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, A.N.; Anderson, J.D.; Mumma, J.; Mahmud, Z.H.; Cumming, O. The association between domestic animal presence and ownership and household drinking water contamination among peri-urban communities of Kisumu, Kenya. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0197587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delahoy, M.J.; Wodnik, B.; McAliley, L.; Penakalapati, G.; Swarthout, J.; Freeman, M.C.; Levy, K. Pathogens transmitted in animal feces in low- and middle-income countries. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2018, 221, 661–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballard, A.M.; Angulo, B.C.; Laramee, N.; Gallagher, J.P.; Haardörfer, R.; Freeman, M.C.; Trostle, J.; Eisenberg, J.N.S.; Lee, G.O.; Levy, K.; et al. Multilevel factors drive child exposure to enteric pathogens in animal feces: A qualitative study in northwestern coastal Ecuador. PLoS Glob. Public Health 2024, 4, e0003604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, N.; Nunn, C.L. Identifying future zoonotic disease threats: Where are the gaps in our understanding of primate infectious diseases? Evol. Med. Public Health 2013, 2013, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patouillat, L.; Hambuckers, A.; Subrata, S.A.; Garigliany, M.; Brotcorne, F. Zoonotic pathogens in wild Asian primates: A systematic review highlighting research gaps. Front. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 1386180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunn, C.L. Primate disease ecology in comparative and theoretical perspective. Am. J. Primatol. 2012, 74, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogarten, J.F.; Calvignac-Spencer, S.; Nunn, C.L.; Ulrich, M.; Saiepour, N.; Nielsen, H.V.; Deschner, T.; Fichtel, C.; Kappeler, P.M.; Knauf, S.; et al. Metabarcoding of eukaryotic parasite communities describes diverse parasite assemblages spanning the primate phylogeny. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2020, 20, 204–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segata, N.; Izard, J.; Waldron, L.; Gevers, D.; Miropolsky, L.; Garrett, W.S.; Huttenhower, C. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol. 2011, 12, R60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Que, T.C.; Pang, X.W.; Huang, H.L.; Chen, P.Y.; Wei, Y.F.; Hua, Y.M.; Liao, H.J.; Wu, J.B.; Li, S.S.; Wu, A.Q.; et al. Comparative Gut Microbiome in Trachypithecus leucocephalus and Other Primates in Guangxi, China, Based on Metagenome Sequencing. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, B.C.; Brown, C.; Gupta, S.; Calarco, J.; Liguori, K.; Milligan, E.; Harwood, V.J.; Pruden, A.; Keenum, I. Recommendations for the use of metagenomics for routine monitoring of antibiotic resistance in wastewater and impacted aquatic environments. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 53, 1731–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houtkamp, I.M.; van Zijll Langhout, M.; Bessem, M.; Pirovano, W.; Kort, R. Multiomics characterisation of the zoo-housed gorilla gut microbiome reveals bacterial community compositions shifts, fungal cellulose-degrading, and archaeal methanogenic activity. Gut Microbiome 2023, 4, e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handelsman, J. Metagenomics: Application of genomics to uncultured microorganisms. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2004, 68, 669–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwok, K.T.T.; Nieuwenhuijse, D.F.; Phan, M.V.T.; Koopmans, M.P.G. Virus Metagenomics in Farm Animals: A Systematic Review. Viruses 2020, 12, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suminda, G.G.D.; Bhandari, S.; Won, Y.; Goutam, U.; Pulicherla, K.K.; Son, Y.O.; Ghosh, M. High-throughput sequencing technologies in the detection of livestock pathogens, diagnosis, and zoonotic surveillance. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2022, 20, 5378–5392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmood, A.; Shama, S.; Ni, H.; Wang, H.; Ling, Y.; Xu, H.; Yang, S.; Naseer, Q.A.; Zhang, W. Viral Metagenomics Revealed a Novel Cardiovirus in Feces of Wild Rats. Intervirology 2019, 62, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ao, Y.; Xu, J.; Duan, Z. A novel cardiovirus species identified in feces of wild Himalayan marmots. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2022, 103, 105347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antinori, S.; Bonazzetti, C.; Giacomelli, A.; Corbellino, M.; Galli, M.; Parravicini, C.; Ridolfo, A.L. Non-human primate and human malaria: Past, present and future. J. Travel Med. 2021, 28, taab036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrillo-Bilbao, G.; Martin-Solano, S.; Saegerman, C. Zoonotic Blood-Borne Pathogens in Non-Human Primates in the Neotropical Region: A Systematic Review. Pathogens 2021, 10, 1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuehrer, H.-P.; Campino, S.; Sutherland, C.J. The primate malaria parasites Plasmodium malariae, Plasmodium brasilianum and Plasmodium ovale spp.: Genomic insights into distribution, dispersal and host transitions. Malar. J. 2022, 21, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Hu, G.; Wu, S.; Cao, C.; Dong, X. A census and status review of the Endangered François’ langur Trachypithecus francoisi in Chongqing, China. Oryx 2013, 47, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, K.; Liu, W.; Xiao, Z.; Wu, A.; Yang, T.; Riondato, I.; Ellwanger, A.L.; Ang, A.; Gamba, M.; Yang, Y.; et al. Exploring Local Perceptions of and Attitudes toward Endangered Francois’ Langurs (Trachypithecus francoisi) in a Human-Modified Habitat. Int. J. Primatol. 2019, 40, 331–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2023. 2023. Available online: https://www.iucnredlist.org (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Luo, Y.; Zhang, M.; Ma, J.; Wu, A.; Wang, S.; Zhang, S. Time Budget of Daily Activity of Francois’ Langur (Trachypithecus francoisi) in Guizhou Province. Acta Theriol. Sin. 2005, 25, 156–162. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, S.Y.; Lin, N.X.; Huang, A.S.; Tong, D.W.; Liang, Y.Y.; Li, Y.B.; Lu, C.H. Feeding Postures and Substrate Use of François’ Langurs (Trachypithecus francoisi) in the Limestone Forest of Southwest China. Animals 2024, 14, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G. Dietary Breadth and Resource Use of Francois’ Langur in a Seasonal and Disturbed Habitat. Am. J. Primatol. 2011, 73, 1176–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.L.; Luo, Y.; Cui, G.F. Sleeping site selection of Francois’s langur (Trachypithecus francoisi) in two habitats in Mayanghe National Nature Reserve, Guizhou, China. Primates 2011, 52, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.L.; Liu, G.H.; Bai, W.K.; Zou, Q.X.; Cao, Y.; Zhou, C.Q.; Williams, G.M. Relationship between Human Disturbance and Habitat Use by the Endangered Francois’ Langur (Trachypithecus francoisi) in Mayanghe Nature Reserve, China. Pak. J. Zool. 2022, 54, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.L.; Zou, Q.X.; Dong, X.; Dong, B.N.; Bai, W.K. Sleeping behavior of the wild Francois’ langur (Trachypithecus francoisi) in Mayanghe Nature Reserve, China. Ethol. Ecol. Evol. 2024, 36, 262–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Yu, Y.; Wu, A.; Zhang, C.; Liu, X.; Qian, C.; Li, J.; Ran, J. The composition and function of the gut microbiota of Francois’ langurs (Trachypithecus francoisi) depend on the environment and diet. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1269492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Zou, Q.; Li, D.; Wang, T.; Han, J. Gut bacterial and fungal communities of François’ langur (Trachypithecus francoisi) changed coordinate to different seasons. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1547955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanya, G. Seasonal variations in the activity budget of Japanese macaques in the coniferous forest of Yakushima: Effects of food and temperature. Am. J. Primatol. 2004, 63, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.J.; Xu, J.L.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, C.F. Habitat Association and Conservation Implications Endangered Francois’ Langur (Trachypithecus francoisi). PLoS ONE 2013, 8, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, K.F.; Xiao, Z.; Wang, B.; Yang, D.; Tan, C.L.; Zhang, P. Population estimates and distribution of françois’ langurs (Trachypithecus francoisi) in Mayanghe National Nature reserve, China. Chin. J. Zool. 2016, 51, 925–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robin, J.D.; Ludlow, A.; LaRanger, R.; Wright, W.; Shay, J. Comparison of DNA Quantification Methods for Next Generation Sequencing. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 24067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1754–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Handsaker, B.; Wysoker, A.; Fennell, T.; Ruan, J.; Homer, N.; Marth, G.; Abecasis, G.; Durbin, R. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 2078–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurk, S.; Meleshko, D.; Korobeynikov, A.; Pevzner, P.A. metaSPAdes: A new versatile metagenomic assembler. Genome Res. 2017, 27, 824–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurevich, A.; Saveliev, V.; Vyahhi, N.; Tesler, G. QUAST: Quality assessment tool for genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 1072–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyatt, D.; Chen, G.L.; Locascio, P.F.; Land, M.L.; Larimer, F.W.; Hauser, L.J. Prodigal: Prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification. BMC Bioinform. 2010, 11, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinegger, M.; Söding, J. MMseqs2 enables sensitive protein sequence searching for the analysis of massive data sets. Nat. Biotechnol. 2017, 35, 1026–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, G.P.; Kin, K.; Lynch, V.J. Measurement of mRNA abundance using RNA-seq data: RPKM measure is inconsistent among samples. Theory Biosci. 2012, 131, 281–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M.; Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lombard, V.; Golaconda Ramulu, H.; Drula, E.; Coutinho, P.M.; Henrissat, B. The carbohydrate-active enzymes database (CAZy) in 2013. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, D490–D495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quast, C.; Pruesse, E.; Yilmaz, P.; Gerken, J.; Schweer, T.; Yarza, P.; Peplies, J.; Glöckner, F.O. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: Improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, D590–D596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Alsayeqh, A.F. Review of major meat-borne zoonotic bacterial pathogens. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 1045599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, S.L.; Reid-Smith, R.; Boerlin, P.; Weese, J.S. Evaluation of the risks of shedding Salmonellae and other potential pathogens by therapy dogs fed raw diets in Ontario and Alberta. Zoonoses Public Health 2008, 55, 470–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abebe, E.; Gugsa, G.; Ahmed, M. Review on Major Food-Borne Zoonotic Bacterial Pathogens. J. Trop. Med. 2020, 2020, 4674235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanders, J.A.; Buoscio, D.A.; Jacobs, B.A.; Gamble, K.C. Retrospective Analysis of Adult-Onset Cardiac Disease in Francois’ Langurs (Trachypithecus francoisi) Housed in us Zoos. J. Zoo Wildl. Med. 2016, 47, 717–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, E.; Sharma, R.S.K.; Cuenca, P.R.; Byrne, I.; Salgado-Lynn, M.; Shahar, Z.S.; Lin, L.C.; Zulkifli, N.; Saidi, N.D.M.; Drakeley, C.; et al. Landscape drives zoonotic malaria prevalence in non-human primates. eLife 2024, 12, RP88616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwanpakdee, S.; Bhusri, B.; Saechin, A.; Mongkolphan, C.; Tangsudjai, S.; Suksai, P.; Kaewchot, S.; Sariwongchan, R.; Sereerak, P.; Sariya, L. Potential Zoonotic Infections Transmitted by Free-Ranging Macaques in Human-Monkey Conflict Areas in Thailand. Zoonoses Public Health 2025, 72, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colwell, R.R. Global climate and infectious disease: The cholera paradigm. Science 1996, 274, 2025–2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naktin, J.; Beavis, K.G. Yersinia enterocolitica and Yersinia pseudotuberculosis. Clin. Lab. Med. 1999, 19, 523–536, vi. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashtanova, D.A.; Popenko, A.S.; Tkacheva, O.N.; Tyakht, A.B.; Alexeev, D.G.; Boytsov, S.A. Association between the gut microbiota and diet: Fetal life, early childhood, and further life. Nutrition 2016, 32, 620–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, J.B.; Vangay, P.; Huang, H.; Ward, T.; Hillmann, B.M.; Al-Ghalith, G.A.; Travis, D.A.; Long, H.T.; Van Tuan, B.; Van Minh, V.; et al. Captivity humanizes the primate microbiome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 10376–10381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clayton, J.B.; Gomez, A.; Amato, K.; Knights, D.; Travis, D.A.; Blekhman, R.; Knight, R.; Leigh, S.; Stumpf, R.; Wolf, T.; et al. The gut microbiome of nonhuman primates: Lessons in ecology and evolution. Am. J. Primatol. 2018, 80, e22867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daszak, P.; Cunningham, A.A.; Hyatt, A.D. Anthropogenic environmental change and the emergence of infectious diseases in wildlife. Acta Trop. 2001, 78, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, K.E.; Patel, N.G.; Levy, M.A.; Storeygard, A.; Balk, D.; Gittleman, J.L.; Daszak, P. Global trends in emerging infectious diseases. Nature 2008, 451, 990–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amato, K.R.; Leigh, S.R.; Kent, A.; Mackie, R.I.; Yeoman, C.J.; Stumpf, R.M.; Wilson, B.A.; Nelson, K.E.; White, B.A.; Garber, P.A. The gut microbiota appears to compensate for seasonal diet variation in the wild black howler monkey (Alouatta pigra). Microb. Ecol. 2015, 69, 434–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Wang, X.; Bernstein, S.; Huffman, M.A.; Xia, D.-P.; Gu, Z.; Chen, R.; Sheeran, L.K.; Wagner, R.S.; Li, J. Marked variation between winter and spring gut microbiota in free-ranging Tibetan Macaques (Macaca thibetana). Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 26035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, K.R.; Ulanov, A.; Ju, K.S.; Garber, P.A. Metabolomic data suggest regulation of black howler monkey (Alouatta pigra) diet composition at the molecular level. Am. J. Primatol. 2017, 79, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, K.R.; Sanders, J.G.; Song, S.J.; Nute, M.; Metcalf, J.L.; Thompson, L.R.; Morton, J.T.; Amir, A.; McKenzie, V.J.; Humphrey, G.; et al. Evolutionary trends in host physiology outweigh dietary niche in structuring primate gut microbiomes. Isme J. 2019, 13, 576–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, B.; Petrzelkova, K.J.; Kreisinger, J.; Bohm, T.; Cervena, B.; Fairet, E.; Fuh, T.; Gomez, A.; Knauf, S.; Maloueki, U.; et al. Gastrointestinal symbiont diversity in wild gorilla: A comparison of bacterial and strongylid communities across multiple localities. Mol. Ecol. 2022, 31, 4127–4145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takemura, A.F.; Chien, D.M.; Polz, M.F. Associations and dynamics of Vibrionaceae in the environment, from the genus to the population level. Front. Microbiol. 2014, 5, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, W.; Liu, G.; Wang, D.; Chen, H.; Zhu, L.; Li, D. Functional convergence of Yunnan snub-nosed monkey and bamboo-eating panda gut microbiomes revealing the driving by dietary flexibility on mammal gut microbiome. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2022, 20, 685–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Jing, S.; Tang, Y.; Li, D.; Qin, M. The effects of food provisioning on the gut microbiota community and antibiotic resistance genes of Yunnan snub-nosed monkey. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1361218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitman, T.; Pepe-Ranney, C.; Enders, A.; Koechli, C.; Campbell, A.; Buckley, D.H.; Lehmann, J. Dynamics of microbial community composition and soil organic carbon mineralization in soil following addition of pyrogenic and fresh organic matter. Isme J. 2016, 10, 2918–2930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eschweiler, K.; Clayton, J.B.; Moresco, A.; McKenney, E.A.; Minter, L.J.; Van Haute, M.J.S.; Gasper, W.; Hayer, S.S.; Zhu, L.; Cooper, K.; et al. Host Identity and Geographic Location Significantly Affect Gastrointestinal Microbial Richness and Diversity in Western Lowland Gorillas (Gorilla gorilla gorilla) under Human Care. Animals 2021, 11, 3399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).