Abstract

A wide range of novelties and significant developments in the field of veterinary science to treat helminth parasites by using natural plant products have been assessed in recent years. To the best of our knowledge, to date, there has not been such a comprehensive review of 19 years of articles on the anthelmintic potential of plants against various types of helminths in different parts of the world. Therefore, the present study reviews the available information on a large number of medicinal plants and their pharmacological effects, which may facilitate the development of an effective management strategy against helminth parasites. An electronic search in four major databases (PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar) was performed for articles published between January 2003 and April 2022. Information about plant species, local name, family, distribution, plant tissue used, and target parasite species was tabulated. All relevant studies meeting the inclusion criteria were assessed, and 118 research articles were included. In total, 259 plant species were reviewed as a potential source of anthelmintic drugs. These plants can be used as a source of natural drugs to treat helminth infections in animals, and their use would potentially reduce economic losses and improve livestock production.

1. Introduction

Livestock production plays a key role in the economic development of a country. Helminthiasis caused by a helminth infection is a major constraint in global livestock production. The mortality and morbidity in animal populations owing to infections caused by parasitic helminths are rapidly increasing worldwide [1]. These parasitic worms are categorized into two major groups: roundworms (phylum Nematoda) and flatworms (phylum Platyhelminthes) [2]. Among these parasites, gastrointestinal parasites pose a serious threat to livestock production. In recent decades, continuous and intensive use of synthetic anthelmintics has been the only method to control gastrointestinal nematodes. However, resistance to all available anthelmintic drug classes has been reported in livestock species. Resistance to an anthelmintic drug is often observed within a few years of introduction of the drug, indicating a remarkably high rate of resistance development, which likely results from a combination of large, genetically diverse parasite populations, and strong selection pressure for resistance. Plants are an ideal source of naturally occurring compounds that can be used as alternative dewormers in livestock [3]. Recently, some anthelmintics have demonstrated loss of efficacy owing to anthelmintic resistance [4]; as a result, parasitic load progressively increases, leading to high mortality and morbidity. Traditional use of medicinal plants for controlling helminth infections is more acceptable owing to the eco-friendly nature and sustainable supply of medicinal plants [5].

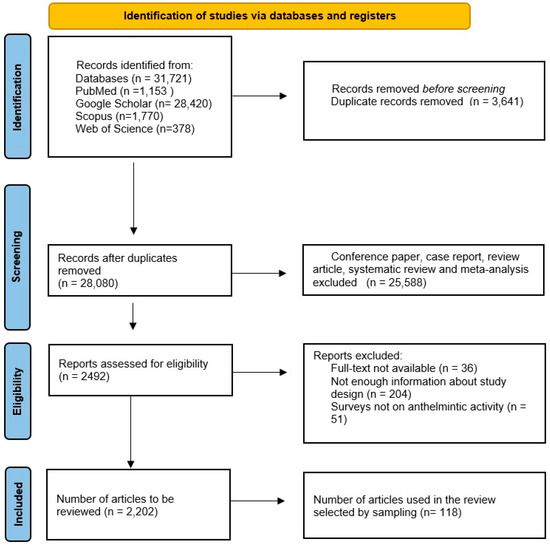

The present review is a comprehensive approach to show a geographical distribution of medicinal plants in a given time period and their anthelmintic potential, which would facilitate their use as an effective management strategy against helminth parasites. An electronic search in four major databases (PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar) was performed for data published between January 2003 and April 2022. Using database-specific strings, different combinations of the following keywords were used: “anthelmintic activity of plants”, “gastrointestinal nematodes”, “Platyhelminthes”, “roundworms”. The studies were required to include information about plant species, local name, plant family, distribution, plant tissue used, and target parasite species. The PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) statement [6] was used as a guide. Prespecified outcome-specific quality criteria were used to judge the admission of each qualitative and quantitative outcome into the appropriate analysis. Two investigators independently reviewed each eligible study and extracted the information and data necessary to carry out the qualitative analysis and the meta-analysis. Disagreements were resolved by consensus among all authors. All relevant studies meeting the criteria were assessed. In some references, multiple lines were used to show them because the authors were working on multiple plant species in the same article. In total, 2202 articles were obtained. However, since not all of them could be included in the current review, it was reduced to 118 articles by sampling (by paying attention to different countries and different plant species and parasites) and used in this review (Figure 1). Finally, 259 plant species from 36 countries worldwide were reviewed as a potential source of anthelmintic drugs. The distribution of the articles used in this review by country is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The PRISMA chart showing the summary of the literature search and query results.

The details of anthelmintic plants and their extracts potentially effective against Platyhelminthes and Nematoda are presented in Table 1 and Table 2, respectively.

Table 1.

List of anthelmintic plants and their extracts effective against flatworms (Platyhelminthes).

Table 2.

List of anthelmintic plants and their extracts effective against roundworms (Nematoda).

2. Chemical Compounds

The literature review revealed that active chemical compounds present in plants were determined using plant volatile essential oils or extracts in ethanol, butanol, methylene chloride, methanol, hydroalcoholic solvents, dichloromethane, chloroform, petroleum ether, or n-hexane. The following active compounds and secondary metabolites were reported: glycosides, tetrahydroharmine, tannins, gallocatechin, epigallocatechin monomers, jacalin, phytohemagglutinin E2L2, phytohemagglutinin L4, phytohemagglutinin E3L, kidney bean albumin, Maclura pomifera agglutinin, Robinia pseudoacacia agglutinin, wheat germ agglutinin, cysteine proteinases, ursolic acid, galactolipid 2 and 3, aporphines, hexylresorcinol, Dolichos biflorus agglutinin, Galanthus nivalis agglutinin, polycarpol, 3-O-acetyl aleuritolic acid, jacalin (jackfruit agglutinin), concanavalin A (jack bean lectin), Maackia amurensis lectin, dichloromethane, and plumbagin (Table 3).

Table 3.

Candidate natural substances with anthelmintic effects.

3. Effect of Plant Extracts in Drug-Resistant Helminths

Medicinal plant extracts have long been used against helminth parasites in humans and livestock; however, scientific support for their application and research on the characterization of active composites remains limited [123]. Numerous studies have investigated anthelmintic resistance, especially in small ruminants. Most studies have used the fecal egg count reduction test (FECRT), which is based on field management practices. Nevertheless, in vivo experiments on drug efficacy have been conducted in areas with high economic importance. Notably, sheep have been studied more extensively than other livestock species, and a broad spectrum of therapeutics have already been developed for sheep [126].

Molecular methods are promising strategies for in vivo and in vitro diagnosis of many infections and may prove to be effective in the detection of parasitic nematodes and anthelmintic resistance [127,128,129,130]. Gaining knowledge about the mechanisms of resistance will ultimately help to reduce anthelmintic drug resistance in parasites. The diagnosis of drug resistance associated with genomic changes using molecular techniques would help in avoiding unnecessary treatments and thus reduce health complications. However, the use of natural plant compounds has the potential to be a complementary control option that can reduce dependence on drug therapy and delay the development of resistance [127,129,131].

In general, many plant secondary metabolites including chalcones, coumarins, terpenoids, tannins, alkaloids, antioxidants, and flavonoids [132,133] possess anthelmintic and neurotoxic properties [134] and inhibit mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation [135,136]. These plant-based compounds typically show higher biological activity than synthetic compounds [137]. In many parts of the world, plants have been used for many generations and are still being used to treat parasitic diseases [138]. The identification of novel compounds from plants as anthelmintics is an emerging field of research. According to a study, between 2000 and 2019, 40 patents were granted for natural-product-based nematicides divided into seven structural classes [139], but none of them have yet been commercialized. However, difficulties in determining the mechanism of action of the main active ingredients in plant extracts are among the main barriers for researchers.

4. Advantages and Disadvantages of Using Plants for Helminth Parasite Control

Limited information is available on gastrointestinal helminth infections in livestock, which remain a major constraint to livestock production worldwide. Nevertheless, a recent study suggests that anthelmintic plants can be used as a potential resource to improve livestock production [38]. The use of plants as anthelmintics has certain benefits over contemporary veterinary treatments, including affordability, lack of adverse effects, and easy accessibility.

Although most of the information available about the antiparasitic properties of medicinal plants is oral and lacked scientific validity until recently, there is now a growing number of controlled laboratory experiments aiming to confirm and quantify anthelmintic plant activity [24]. Plants can be used in the following two manners: 1. plant parts can be used to cure infected animals naturally or 2. plant extracts and concoctions can be tested both in vitro and in vivo for their anthelmintic potential. The advantages of using antiparasitic plants include effectiveness against species resistant to synthetic anthelmintic drugs, limited or no risk of resistance development, and environmentally friendly procedure [42]. A major drawback is that, to date, only a small number of anthelmintic compounds such as macrocyclic lactones, cyclic octadepsipeptides, benzimidazoles, and imidazothiazoles have been identified in plants after decades of research [65]. Another drawback is the inconsistency between in vitro and in vivo studies on the use of plants as anthelmintics, raising questions regarding their validity and reliability [67]. Additionally, neurological effects associated with the dosage and bioavailability of some medicinal plants need to be elucidated before their use. The choice of an appropriate host–parasite system is tricky in in vivo studies because caring for the animal models adequately is expensive, time-consuming, and labor-intensive [100]. Other drawbacks include uncertainty about plant efficacy, nonspecific responses, irreproducible preparations, and potential negative consequences. An alternative strategy is to use plant secondary metabolites with anthelmintic activity [73]. Secondary metabolites exhibit various modes of action for anthelmintic activity. For example, tannins hinder the feeding process of parasites through forming complexes with parasite proteins or deactivating key enzymes [73]. Terpenes block the tyramine receptors of parasites, whereas alkaloids create unfavorable conditions in the host intestine by generating nitrated and free sugars [97,124]. However, it is important to conduct more studies on the underlying molecular mechanisms and adverse effects on the host to improve drug development.

5. Recommendations

An ideal anthelmintic agent should have a broad spectrum of action, a high treatment rate with a single therapeutic dose, low toxicity to the host, and cost-effectiveness. Most currently used synthetic drugs do not meet these requirements. Commonly used drugs have side effects such as nausea, drowsiness, and intestinal disorders. The development of resistance to existing drugs in parasites and the high cost of drugs have led researchers to explore novel anthelmintic effective agents. Ethnobotanical drugs are the source of easily available and effective anthelmintic agents for humans, especially in tropical and developing countries. Thus, people use various herbs or products derived from plants to treat helminth infections. Plants produce secondary metabolites with various ecophysiological functions, such as defense against pathogen attacks and protection against abiotic stresses. These metabolites have potential medicinal effects in humans and animals.

6. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

It is estimated that more than 2.5 billion people are affected with helminth parasites at some stage in their lives. Parasitic diseases remain the major reason of substantial economic loss owing to their impact on livestock health and unexpected deworming costs. According to the literature review, potential anthelmintic plants exhibit great diversity in terms of species and compounds. Nevertheless, initially, all anthelmintics are tested in livestock before being used for human therapy; thus, developments in veterinary anthelmintics could also lead to advancements in human therapy. In addition, studies on nutritional support and vaccination are also required to develop livestock with low parasite susceptibility.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and design, S.S., J.C. and H.A.; analysis and interpretation of data, H.K.K., H.A., F.C., S.G.K. and K.S.A.; writing—original draft preparation, H.A., M.S.A. and W.S.; statistical analysis, S.F.; supervision, S.S. and J.C.; writing—review and editing, H.A., M.S.A., K.S.A., S.F., S.S., J.Z., F.P., S.L. and J.C. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 81971969, 82272369, and 81772225 to JC) and the Three-Year Public Health Action Plan (2020–2022) of Shanghai (No. GWV-10.1-XK13 to JC). The funders had no role in the study design, the data collection, and analysis, the decision to publish, or the preparation of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Nirmal, S.A.; Malwadkar, G.; Laware, R. Anthelmintic activity of Pongamia glabra. Songklanakarin J. Sci. Technol. 2007, 29, 755–757. [Google Scholar]

- Onyeyili, P.; Nwosu, C.; Amin, J.; Jibike, J. Anthelmintic activity of crude aqueous extract of Nauclea latifolia stem bark against ovine nematodes. Fitoterapia 2001, 72, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmoudvand, H.; Kheirandish, F.; Ghasemi Kia, M.; Tavakoli Kareshk, A.; Yarahmadi, M. Chemical composition, protoscolicidal effects and acute toxicity of Pistacia atlantica Desf. fruit extract. Nat. Prod. Res. 2016, 30, 1208–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenberg, R.M. Ca2+ signalling, voltage-gated Ca2+ channels and praziquantel in flatworm neuromusculature. Parasitology 2005, 131, S97–S108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, L.; Bevilaqua, C.; Costa, C.; Macedo, I.; Barros, R.; Rodrigues, A.; Camurça-Vasconcelos, A.; Morais, S.; Lima, Y.; Vieira, L. Anthelmintic activity of Cocos nucifera L. against sheep gastrointestinal nematodes. Vet. Parasitol. 2009, 159, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009, 62, e1–e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minsakorn, S.; Nuplod, K.; Puttarak, P.; Chawengkirttikul, R.; Panyarachun, B.; Ngamniyom, A.; Charoenkul, T.; Jaisa-Aad, M.; Panyarachun, P.; Anuracpreeda, P. The anthelmintic effects of medicinal plant extracts against paramphistome parasites, Carmyerius spatiosus. Acta Parasitol. 2019, 64, 566–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomsen, H.; Reider, K.; Franke, K.; Wessjohann, L.; Keiser, J.; Dagne, E.; Arnold, N. Characterization of constituents and anthelmintic properties of Hagenia abyssinica. Sci. Pharm. 2012, 80, 433–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zibaei, M.; Rostamipour, R.; Nayebzadeh, H. Effect of Pistacia atlantica fruit and leaf extracts on hydatid cyst protoscolices. Recent Pat. Antiinfect. Drug Discov. 2016, 11, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yones, D.A.; Taher, G.A.; Ibraheim, Z.Z. In vitro effects of some herbs used in Egyptian traditional medicine on viability of protoscolices of hydatid cysts. Korean J. Parasitol. 2011, 49, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Daoody, A.A.; Shareef, A.Y.; Hammoshi, M.H. In Vitro Effects of Ethanolic Extract and Crude Alkaloids of Prosopis farcta Leaves on the Viability of Echinococcus granulosus Protoscolices in Comparison to Mebendazole. RJS Rafidain J. Sci. 2006, 17, 43–52. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoudvand, H.; Dezaki, E.S.; Kheirandish, F.; Ezatpour, B.; Jahanbakhsh, S.; Harandi, M.F. Scolicidal effects of black cumin seed (Nigella sativa) essential oil on hydatid cysts. Korean J. Parasitol. 2014, 52, 653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barzinji, R.; Kadir, A.; Mothana, R.A.; Nasher, A.K. Effect of leaf extracts of Dendrosicyos socotrana and Jatropha unicostata on the viability of Echinococcus granulosus protoscoleces. EurAsian J. Biosci. 2009, 3, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouhani, S.; Salehi, N.; Kamalinejad, M.; Zayeri, F. Efficacy of Berberis vulgaris aqueous extract on viability of Echinococcus granulosus protoscolices. J. Investig. Surg. 2013, 26, 347–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gangwar, M.; Verma, V.C.; Singh, T.D.; Singh, S.K.; Goel, R.; Nath, G. In-vitro scolicidal activity of Mallotus philippinensis (Lam.) Muell Arg. fruit glandular hair extract against hydatid cyst Echinococcus granulosus. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Dis. 2013, 6, 595–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, V.C.; Gangwar, M.; Yashpal, M.; Nath, G. Anticestodal activity of endophytic Pestalotiopsis sp. on protoscoleces of hydatid cyst Echinococcus granulosus. Biomed Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 308515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Mercado, J.M.; Ibarra-Velarde, F.; Alonso-Díaz, M.Á.; Vera-Montenegro, Y.; Avila-Acevedo, J.G.; García-Bores, A.M. In vitro antihelmintic effect of fifteen tropical plant extracts on excysted flukes of Fasciola hepatica. BMC Vet. Res. 2015, 11, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; SUNITA, K.; Singh, R.; Singh, D. Fasciola larvae: Anthelmintic activity of medicinal plant Potentilla fulgens against sporocyst, redia and cercaria. Asian J. Adv. Agric. Res. 2020, 3, 24–30. [Google Scholar]

- Vishwakarma, A.; Kumar, P. In vivo Anthelmintic Activity of Medicinal plant Asparagus racemosus against Larva of Fasciola gigantica. Res. J. Agri. Sci. 2021, 12, 675–680. [Google Scholar]

- Onocha, P.; Olusanya, T. Antimicrobial and anthelmintic evaluation of Nigerian Euphorbiaceae plants 3: Acalypha wilkesiana. Afr. Sci. 2021, 11, 85–89. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, B.; Swargiary, A.; Giri, B.R. Alpinia nigra (Family Zingiberaceae): An anthelmintic medicinal plant of north-east India. Adv. Life Sci. 2012, 2, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soren, A.D.; Yadav, A.K. In Vitro Anthelmintic Efficacy of Sesbania sesban var. bicolor, Cyperus compressus and Asparagus racemosus against Gastrothylax crumenifer (Trematoda). Proc. Zool. Soc. 2021, 74, 262–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soren, A.D.; Yadav, A.K. Studies on the anthelmintic potentials of the roots of Asparagus racemosus willd.(Asparagaceae). Clin. Phytoscience 2021, 7, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soren, A.D.; Yadav, A.K. Evaluation of in vitro and in vivo anthelmintic efficacy of Cyperus compressus Linn., a traditionally used anthelmintic plant in parasite-animal models. Future J. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 6, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soren, A.D.; Chen, R.P.; Yadav, A.K. In vitro and in vivo anthelmintic study of Sesbania sesban var. bicolor, a traditionally used medicinal plant of Santhal tribe in Assam, India. J. Parasit. Dis. 2021, 45, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, S.; Lyndem, L.M. An in vitro confirmation of the ethonopharmacological use of Senna plants as anthelmintic against rumen fluke Paramphistomum gracile. BMC Vet. Res. 2019, 15, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shalaby, H.; Soad, N.; Farag, T. Tegumental effects of methanolic extract of Balanites aegyptiaca fruits on adult Paramphistomum microbothrium (Fischoeder 1901) under laboratory conditions. Iran. J. Parasitol. 2016, 11, 396. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lalthanpuii, P.; Zokimi, Z.; Lalchhandama, K. The toothache plant (Acmella oleracea) exhibits anthelmintic activity on both parasitic tapeworms and roundworms. Pharmacogn. Mag. 2020, 16, 193. [Google Scholar]

- Kosalge, S.B.; Fursule, R.A. Investigation of in vitro anthelmintic activity of Thespesia lampas (Cav.). Asian J. Pharm. Clin. Res. 2009, 2, 69–71. [Google Scholar]

- Rabiu, H.; Subhasish, M. Investigation of in vitro anthelmintic activity of Azadirachta indica leaves. Int. J. Drug Dev. Res. 2011, 3, 94–100. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, N.; Ali Shah, S.W.; Shah, I.; Ahmed, G.; Ghias, M.; Khan, I.; Ali, W. Anthelmintic and relaxant activities of Verbascum Thapsus Mullein. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2012, 12, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, N.; Shah, S.W.A.; Shah, I.; Ahmed, G.; Ghias, M.; Khan, I. Cytotoxic and anthelmintic potential of crude saponins isolated from Achillea Wilhelmsii, C. Koch and Teucrium Stocksianum boiss. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2011, 11, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabiul, H.; Subhasish, M. Investigation of in vitro anthelmintic activity of Cinnamomum camphor leaves. Int. J. Drug Dev. Res. 2011, 3, 295–300. [Google Scholar]

- Subhasish, M.; Rabiul, H.; Parag, G.; Debasish, D. Investigation of in vitro anthelmintic activity of Clerodendron inerme. Int. J. Drug Dev. Res. 2010, 2, 826–829. [Google Scholar]

- Lalthanpuii, P.B.; Lalchhandama, K. Phytochemical analysis and in vitro anthelmintic activity of Imperata cylindrica underground parts. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2020, 20, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekwu, E.M.; Bosompem, K.M.; Anyan, W.K.; Appiah-Opong, R.; Owusu, K.B.-A.; Tettey, M.D.; Kissi, F.A.; Appiah, A.A.; Penlap Beng, V.; Nyarko, A.K. In vitro assessment of anthelmintic activities of Rauwolfia vomitoria (Apocynaceae) stem bark and roots against parasitic stages of Schistosoma mansoni and cytotoxic study. J. Parasitol. Res. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, R.N.; Rehder, V.L.G.; Oliveira, A.S.S.; Jeraldo, V.d.L.S.; Linhares, A.X.; Allegretti, S.M. Anthelmintic activity in vitro and in vivo of Baccharis trimera (Less) DC against immature and adult worms of Schistosoma mansoni. Exp. Parasitol. 2014, 139, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godinho, L.S.; de Carvalho, A.; Soares, L.; Barbosa de Castro, C.C.; Dias, M.M.; Pinto, P.d.F.; Crotti, A.E.M.; Pinto, P.L.S.; de Moraes, J.; Da Silva Filho, A.A. Anthelmintic activity of crude extract and essential oil of Tanacetum vulgare (Asteraceae) against adult worms of Schistosoma mansoni. Sci. World J. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, A.F.; de Azevedo, D.P.; dos Santos Mata, R.d.C.; de Mendonça, D.I.D.; Sant’Ana, A.E.G. The lethality of Euphorbia conspicua to adults of Biomphalaria glabrata, cercaria of Schistosoma mansoni and larvae of Artemia salina. Bioresour. Technol. 2007, 98, 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atjanasuppat, K.; Wongkham, W.; Meepowpan, P.; Kittakoop, P.; Sobhon, P.; Bartlett, A.; Whitfield, P.J. In vitro screening for anthelmintic and antitumour activity of ethnomedicinal plants from Thailand. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2009, 123, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.K.; Kumar, P.; Venkatachalam, T. Investigation of anthelmintic activity of Pergularia daemia leaves. Pharmacophore 2014, 5, 44–48. [Google Scholar]

- Lalthanpuii, P.B.; Lalchhandama, K. Chemical composition and broad-spectrum anthelmintic activity of a cultivar of toothache plant, Acmella oleracea, from Mizoram, India. Pharm. Biol. 2020, 58, 393–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dkhil, M.A.; Zreiq, R.; Hafiz, T.A.; Mubaraki, M.A.; Sulaiman, S.; Algahtani, F.; Abdel-Gaber, R.; Al-Shaebi, E.M.; Al-Quraishy, S. Anthelmintic and antimicrobial activity of Indigofera oblongifolia leaf extracts. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 27, 594–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flota-Burgos, G.J.; Rosado-Aguilar, J.A.; Rodríguez-Vivas, R.I.; Borges-Argáez, R.; Martínez-Ortiz-de-Montellano, C.; Gamboa-Angulo, M. Anthelmintic activity of extracts and active compounds from Diospyros anisandra on Ancylostoma caninum, Haemonchus placei and Cyathostomins. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 565103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lalchhandama, K.; Roy, B.; Dutta, B.K. Anthelmintic activity of Acacia oxyphylla stem bark against Ascaridia galli. Pharm. Biol. 2009, 47, 578–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.; Patil, S.; Dharanguttikar, V.; Mohite, S. Anthelmintic Activity of Malvastrum Coromandelianum Leaf Extracts against Pheretima Posthuma and Ascardia Galli. Int. J. Sci. Res. Chemi. 2020, 5, 18–24. [Google Scholar]

- Ezea, B.O.; Ogbole, O.O.; Ajaiyeoba, E.O. In vitro anthelmintic properties of root extracts of three Musa species. J. Pharm. Bioresour. 2019, 16, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.R.; Soelberg, J.; Jäger, A.K. Anthelmintic properties of traditional African and Caribbean medicinal plants: Identification of extracts with potent activity against Ascaris suum in vitro. Parasite 2016, 23, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.R.; Fryganas, C.; Ramsay, A.; Mueller-Harvey, I.; Thamsborg, S.M. Direct anthelmintic effects of condensed tannins from diverse plant sources against Ascaris suum. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e97053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Shakya, S.; Soni, V.K.; Dangi, A.; Kumar, N.; Bhattacharya, S.-M. The n-hexane and chloroform fractions of Piper betle L. trigger different arms of immune responses in BALB/c mice and exhibit antifilarial activity against human lymphatic filarid Brugia malayi. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2009, 9, 716–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, N.; Misra-Bhattacharya, S.; Perumal, V.; Muthuswamy, K. Antifilarial lead molecules isolated from Trachyspermum ammi. Molecules 2008, 13, 2156–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaur, R.; Sahoo, M.; Dixit, S.; Fatma, N.; Rastogi, S.; Kulshreshtha, D.; Chatterjee, R.; Murthy, P. Antifilarial activity of Caesalpinia bonducella against experimental filarial infections. Indian J. Med. Res. 2008, 128, 65. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Misra, N.; Sharma, M.; Raj, K.; Dangi, A.; Srivastava, S.; Misra-Bhattacharya, S. Chemical constituents and antifilarial activity of Lantana camara against human lymphatic filariid Brugia malayi and rodent filariid Acanthocheilonema viteae maintained in rodent hosts. Parasitol. Res. 2007, 100, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujimaki, Y.; Kamachi, T.; Yanagi, T.; Caceres, A.; Maki, J.; Aoki, Y. Macrofilaricidal and microfilaricidal effects of Neurolaena lobata, a Guatemalan medicinal plant, on Brugia pahangi. J. Helminthol. 2005, 79, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okem, A.; Finnie, J.; Van Staden, J. Pharmacological, genotoxic and phytochemical properties of selected South African medicinal plants used in treating stomach-related ailments. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2012, 139, 712–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndjonka, D.; Agyare, C.; Lüersen, K.; Djafsia, B.; Achukwi, D.; Nukenine, E.; Hensel, A.; Liebau, E. In vitro activity of Cameroonian and Ghanaian medicinal plants on parasitic (Onchocerca ochengi) and free-living (Caenorhabditis elegans) nematodes. J. Helminthol. 2011, 85, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katiki, L.M.; Ferreira, J.F.; Gonzalez, J.M.; Zajac, A.M.; Lindsay, D.S.; Chagas, A.C.S.; Amarante, A.F. Anthelmintic effect of plant extracts containing condensed and hydrolyzable tannins on Caenorhabditis elegans, and their antioxidant capacity. Vet. Parasitol. 2013, 192, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Son-de Fernex, E.; Alonso-Díaz, M.Á.; Mendoza-de Gives, P.; Valles-de la Mora, B.; González-Cortazar, M.; Zamilpa, A.; Gallegos, E.C. Elucidation of Leucaena leucocephala anthelmintic-like phytochemicals and the ultrastructural damage generated to eggs of Cooperia spp. Vet. Parasitol. 2015, 214, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osei Akoto, C.; Acheampong, A.; Boakye, Y.D.; Naazo, A.A.; Adomah, D.H. Anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and anthelmintic activities of Ocimum basilicum (Sweet Basil) fruits. J. Chemistry 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Yousef, B.; M Hassan, H.; Zhang, L.-Y.; Jiang, Z.-Z. Anticancer potential and molecular targets of pristimerin: A mini-review. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets. 2017, 17, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiaty, A.M.; Salib, F.A.; El-Gameel, S.M.; Hussien, A.M.; Kamel, M.S. Anthelmintic activity of pomegranate peel extract (Punica granatum) and synthetic anthelmintics against gastrointestinal nematodes in cattle, sheep, goats, and buffalos: In vivo study. Parasitol. Res. 2021, 120, 3883–3893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Medeiros, M.L.S.; de Moura, M.C.; Napoleão, T.H.; Paiva, P.M.G.; Coelho, L.C.B.B.; Bezerra, A.C.D.S.; da Silva, M.D.C. Nematicidal activity of a water soluble lectin from seeds of Moringa oleifera. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 108, 782–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alowanou, G.; Olounladé, P.; Akouèdegni, G.; Faihun, A.; Koudandé, D.; Hounzangbé-Adoté, S. In vitro anthelmintic effects of Bridelia ferruginea, Combretum glutinosum, and Mitragyna inermis leaf extracts on Haemonchus contortus, an abomasal nematode of small ruminants. Parasitol. Res. 2019, 118, 1215–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndlela, S.; Mkwanazi, M.; Chimonyo, M. In vitro efficacy of plant extracts against gastrointestinal nematodes in goats. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2021, 53, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castagna, F.; Piras, C.; Palma, E.; Musolino, V.; Lupia, C.; Bosco, A.; Rinaldi, L.; Cringoli, G.; Musella, V.; Britti, D. Green veterinary pharmacology applied to parasite control: Evaluation of Punica granatum, Artemisia campestris, Salix caprea aqueous macerates against gastrointestinal nematodes of sheep. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piza, M.; Féboli, A.; Augusto, J.; Anjos, L.; Laurentiz, A.; Royo, V.; Alvarenga, F.; Laurentiz, R. In vitro ovicidal and larvicidal activity of Psidium cattleianum Sabine leaves against gastrointestinal nematodes of naturally infected sheep. Bol. Ind. Anim. 2019, 76, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castagna, F.; Britti, D.; Oliverio, M.; Bosco, A.; Bonacci, S.; Iriti, G.; Ragusa, M.; Musolino, V.; Rinaldi, L.; Palma, E. In vitro anthelminthic efficacy of aqueous pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) extracts against gastrointestinal nematodes of sheep. Pathogens 2020, 9, 1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jogpal, B.; Swarnakar, G.; Chouhan, H.S.; Roat, K. In vitro anthelmintic activity of medicinal plant Tinospora cordifolia extract on amphistome Gastrothylax crumenifer. Ecol. Environ. Conserv. 2021, 27, 231–234. [Google Scholar]

- Irum, S.; Ahmed, H.; Mukhtar, M.; Mushtaq, M.; Mirza, B.; Donskow-Łysoniewska, K.; Qayyum, M.; Simsek, S. Anthelmintic activity of Artemisia vestita Wall ex DC. and Artemisia maritima L. against Haemonchus contortus from sheep. Vet. Parasitol. 2015, 212, 451–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, J.; Hildreth, M.B.; Reese, R.N. In vitro screening of forty medicinal plant extracts from the United States Northern Great Plains for anthelmintic activity against Haemonchus contortus. Vet. Parasitol. 2014, 201, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, K.; Chishti, M.; Ahmad, F.; Shawl, A. Anthelmintic efficacy of Achillea millifolium against gastrointestinal nematodes of sheep: In vitro and in vivo studies. J. Helminthol. 2008, 82, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, L.; Castro, P.; Chagas, A.; França, S.; Beleboni, R. In vitro anthelmintic activity of aqueous leaf extract of Annona muricata L.(Annonaceae) against Haemonchus contortus from sheep. Exp. Parasitol. 2013, 134, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, A.M.; Oliveira, J.T.; Rocha, C.Q.; Ferreira, A.T.; Perales, J.; Zanatta, A.C.; Vilegas, W.; Silva, C.R.; Costa-Junior, L.M. Myracrodruon urundeuva seed exudates proteome and anthelmintic activity against Haemonchus contortus. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0200848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.; Laing, M.; Nsahlai, I. In vitro anthelmintic activity of crude extracts of selected medicinal plants against Haemonchus contortus from sheep. J. Helminthol. 2013, 87, 174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alawa, C.; Adamu, A.; Gefu, J.; Ajanusi, O.; Abdu, P.; Chiezey, N.; Alawa, J.; Bowman, D. In vitro screening of two Nigerian medicinal plants (Vernonia amygdalina and Annona senegalensis) for anthelmintic activity. Vet. Parasitol. 2003, 113, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahiya, C.; Mukaratirwa, S.; Thamsborg, S.M. Effects of Acacia nilotica and Acacia karoo diets on Haemonchus contortus infection in goats. Vet. Parasitol. 2003, 115, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamilpa, A.; García-Alanís, C.; López-Arellano, M.; Hernández-Velázquez, V.; Valladares-Cisneros, M.; Salinas-Sánchez, D.; Mendoza-de Gives, P. In vitro nematicidal effect of Chenopodium ambrosioides and Castela tortuosa n-hexane extracts against Haemonchus contortus (Nematoda) and their anthelmintic effect in gerbils. J. Helminthol. 2019, 93, 434–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebai, E.; Serairi, R.; Saratsi, K.; Abidi, A.; Sendi, N.; Darghouth, M.A.; Wilson, M.S.; Sotiraki, S.; Akkari, H. Hydro-ethanolic extract of Mentha pulegium exhibit anthelmintic and antioxidant proprieties in vitro and in vivo. Acta Parasitol. 2020, 65, 375–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhadde Gurunath, S.; Mali Hanmant, S.; Sapate Rohit, B.; Vakhariya Rohan, R.; Raut Indrayani, D.; Nitalikar Manoj, M. Investigation of In-Vitro Anthelmintic Activity of Methanolic Extract of Tylophora Indica Leaves against Haemonchus contortus. J. Univ. Shanghai Sci. Technol. 2021, 23, 37–42. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, A.F.; Junior, L.M.C.; Lima, A.S.; Silva, C.R.; Ribeiro, M.N.; Mesquista, J.W.; Rocha, C.Q.; Tangerina, M.M.; Vilegas, W. Anthelmintic activity of plant extracts from Brazilian savanna. Vet. Parasitol. 2017, 236, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soldera-Silva, A.; Seyfried, M.; Campestrini, L.H.; Zawadzki-Baggio, S.F.; Minho, A.P.; Molento, M.B.; Maurer, J.B.B. Assessment of anthelmintic activity and bio-guided chemical analysis of Persea americana seed extracts. Vet. Parasitol. 2018, 251, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mravčáková, D.; Komáromyová, M.; Babják, M.; Urda Dolinská, M.; Königová, A.; Petrič, D.; Čobanová, K.; Ślusarczyk, S.; Cieslak, A.; Várady, M. Anthelmintic activity of wormwood (Artemisia absinthium L.) and mallow (Malva sylvestris L.) against Haemonchus contortus in sheep. Animals 2020, 10, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.H.; Ejo, M.; Feyera, T.; Regassa, D.; Mummed, B.; Huluka, S.A. In vitro anthelmintic activity of crude extracts of Artemisia herba-alba and Punica granatum against Haemonchus contortus. J. Parasitol. Res. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, M.A.; Islam, M.R.; Lovelu, M.A.; Nahar, S.F.; Dutta, P.K.; Talukder, M.H. In vitro evaluation of anthelmintic activity of tannin-containing plant Artemisia extracts against Haemonchus contortus from goat: Anthelmintic activity of tannin-containing plants Artemisia. J. Bangladesh Agric. Univ. 2019, 17, 363–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoste, H.; Brunet, S.; Paolini, V.; Bahuaud, D.; Chauveau, S.; Fouraste, I.; Lefrileux, Y. Compared in vitro anthelmintic effects of eight tannin-rich plants browsed by goats in the southern part of France. Option Méditerrenéennes 2009, 85, 431–436. [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal, Z.; Lateef, M.; Ashraf, M.; Jabbar, A. Anthelmintic activity of Artemisia brevifolia in sheep. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2004, 93, 265–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tariq, K.; Chishti, M.; Ahmad, F.; Shawl, A. Anthelmintic activity of extracts of Artemisia absinthium against ovine nematodes. Vet. Parasitol. 2009, 160, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manolaraki, F.; Sotiraki, S.; Stefanakis, A.; Skampardonis, V.; Volanis, M.; Hoste, H. Anthelmintic activity of some Mediterranean browse plants against parasitic nematodes. Parasitology 2010, 137, 685–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busari, I.; Soetan, K.; Aiyelaagbe, O.; Babayemi, O. Phytochemical screening and in vitro anthelmintic activity of methanolic extract of Terminalia glaucescens leaf on Haemonchus contortus eggs. Acta Trop. 2021, 223, 106091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eguale, T.; Tadesse, D.; Giday, M. In vitro anthelmintic activity of crude extracts of five medicinal plants against egg-hatching and larval development of Haemonchus contortus. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011, 137, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarza-Albarrán, M.; Olmedo-Juárez, A.; Rojo-Rubio, R.; Mendoza-de Gives, P.; González-Cortazar, M.; Tapia-Maruri, D.; Mondragón-Ancelmo, J.; García-Hernández, C.; Blé-González, E.A.; Zamilpa, A. Galloyl flavonoids from Acacia farnesiana pods possess potent anthelmintic activity against Haemonchus contortus eggs and infective larvae. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 249, 112402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañeda-Ramírez, G.S.; de Jesús Torres-Acosta, J.F.; Sandoval-Castro, C.A.; Borges-Argáez, R.; Cáceres-Farfán, M.; Mancilla-Montelongo, G.; Mathieu, C. Bio-guided fractionation to identify Senegalia gaumeri leaf extract compounds with anthelmintic activity against Haemonchus contortus eggs and larvae. Vet. Parasitol. 2019, 270, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno, F.C.; Gordon, I.J.; Wright, A.; Benvenutti, M.A.; Saumell, C. Efecto antihelmíntico in vitro de extractos de plantas sobre larvas infectantes de nematodos gastrointestinales de rumiantes. Arch. Med. Vet. 2010, 42, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyasse, B.; Ngantchou, I.; Nono, J.-J.; Schneider, B. Antifilarial activity in vitro of polycarpol and 3-O-acetyl aleuritolic acid from cameroonian medicinal plants against Onchocerca gutturosa. Nat. Prod. Res. 2006, 20, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndjonka, D.; Rapado, L.; Silber, A.; Liebau, E.; Wrenger, C. Natural products as a source for treating neglected parasitic diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 3395–3439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakhshandehroo, E.; Asadpour, M.; Malekpour, S.; Jafari, A. The anthelmintic effects of five plant extracts on the viability of Parascaris equorum larvae. Equine Vet. Educ. 2017, 29, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GS, R.I.D.; Yadav, J.; Sapate, R.; Mali, H. In vitro Anthelmintic Activity of crude extract of flowers of Bougainvillea Spectabilis Wild against Pheretima Posthuma. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 17, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Chander, P.A.; Sri, H.Y.; Sravanthi, N.B.; Susmitha, U.V. In vitro anthelmintic activity of Barleria buxifolia on Indian adult earthworms and estimation of total flavonoid content. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Dis. 2014, 4, S233–S235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, H.; Kapadia, M.; Kharat, A. Evaluation of anthelmintic activity of Plumbago zeylanica Linn. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. 2012, 3, 4281. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, V.; Ramos, L.d.A.; da Silva, C.; Nebo, L.; Moraes, D.; Da Silva, F.; Da Costa, N.; Junior, R.d.O.R.; De Souza, L.; Rodrigues, R. In vitro anthelmintic activity of Siparuna guianensis extract and essential oil against Strongyloides venezuelensis. J. Helminthol. 2020, 94, e50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalaby, H.A.; El Namaky, A.H.; Khalil, F.A.; Kandil, O.M. Efficacy of methanolic extract of Balanites aegyptiaca fruits on Toxocara vitulorum. Vet. Parasitol. 2012, 183, 386–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ríos-de Álvarez, L.; Jackson, F.; Greer, A.; Grant, G.; Jackson, E.; Morrison, A.; Huntley, J. Direct anthelmintic and immunostimulatory effects of oral dosing semi-purified phytohaemagglutinin lectin in sheep infected with Teladorsagia circumcincta and Trichostrongylus colubriformis. Vet. Parasitol. 2012, 187, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, A.F.; Fonseca, S.A.; César, F.A.; de Azevedo Albuquerque, M.C.P.; Santana, J.V.; Santana, A.E.G. A penta-substituted pyridine alkaloid from the rhizome of Jatropha elliptica (Pohl) Muell. Arg. is active against Schistosoma mansoni and Biomphalaria glabrata. Parasitol. Res. 2014, 113, 1077–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharifi-Rad, J.; Hoseini-Alfatemi, S.; Sharifi-Rad, M.; Sharifi-Rad, M.; Iriti, M.; Sharifi-Rad, M.; Sharifi-Rad, R.; Raeisi, S. Phytochemical compositions and biological activities of essential oil from Xanthium strumarium L. Molecules 2015, 20, 7034–7047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkari, H.; Ezzine, O.; Dhahri, S.; B’chir, F.; Rekik, M.; Hajaji, S.; Darghouth, M.A.; Jamâa, M.L.B.; Gharbi, M. Chemical composition, insecticidal and in vitro anthelmintic activities of Ruta chalepensis (Rutaceae) essential oil. Ind. Crops. Prod. 2015, 74, 745–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, F.C.; Gordon, I.J.; Knox, M.; Summer, P.; Skerrat, L.; Benvenutti, M.A.; Saumell, C. Anthelmintic efficacy of five tropical native Australian plants against Haemonchus contortus and Trichostrongylus colubriformis in experimentally infected goats (Capra hircus). Vet. Parasitol. 2012, 187, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansur, F.; Luoga, W.; Buttle, D.; Duce, I.; Lowe, A.; Behnke, J. The anthelmintic efficacy of natural plant cysteine proteinases against two rodent cestodes Hymenolepis diminuta and Hymenolepis microstoma in vitro. Vet. Parasitol. 2014, 201, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalani, K.; Kushwaha, V.; Sharma, P.; Verma, R.; Srivastava, M.; Khan, F.; Murthy, P.; Srivastava, S.K. In vitro, in silico and in vivo studies of ursolic acid as an anti-filarial agent. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e111244. [Google Scholar]

- Kushwaha, S.; Roy, S.; Maity, R.; Mallick, A.; Soni, V.K.; Singh, P.K.; Chaurasiya, N.D.; Sangwan, R.S.; Misra-Bhattacharya, S.; Mandal, C. Chemotypical variations in Withania somnifera lead to differentially modulated immune response in BALB/c mice. Vaccine 2012, 30, 1083–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushwaha, S.; Soni, V.K.; Singh, P.K.; Bano, N.; Kumar, A.; Sangwan, R.S.; Bhattacharya, S.M. Withania somnifera chemotypes NMITLI 101R, NMITLI 118R, NMITLI 128R and withaferin A protect Mastomys coucha from Brugia malayi infection. Parasite Immunol. 2011, 34, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sashidhara, K.V.; Singh, S.P.; Misra, S.; Gupta, J.; Misra-Bhattacharya, S. Galactolipids from Bauhinia racemosa as a new class of antifilarial agents against human lymphatic filarial parasite, Brugia malayi. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 50, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magalhães, L.G.; Machado, C.B.; Morais, E.R.; de Carvalho Moreira, É.B.; Soares, C.S.; da Silva, S.H.; Da Silva Filho, A.A.; Rodrigues, V. In vitro schistosomicidal activity of curcumin against Schistosoma mansoni adult worms. Parasitol. Res. 2009, 104, 1197–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.; Nishino, K.; Roberts, M.C.; Tolmasky, M.; Aminov, R.I.; Zhang, L. Mechanisms of antibiotic resistance. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maestrini, M.; Tava, A.; Mancini, S.; Salari, F.; Perrucci, S. In vitro anthelmintic activity of saponins derived from Medicago spp. plants against donkey gastrointestinal nematodes. Vet. Sci. 2019, 6, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maestrini, M.; Tava, A.; Mancini, S.; Tedesco, D.; Perrucci, S. In vitro anthelmintic activity of saponins from Medicago spp. against sheep gastrointestinal nematodes. Molecules 2020, 25, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buza, V.; Cătană, L.; Andrei, S.; Ștefănuț, L.; Răileanu, Ș.; Matei, M.; Vlasiuc, I.; Cernea, M. In vitro anthelmintic activity assessment of six medicinal plant aqueous extracts against donkey strongyles. J. Helminthol. 2020, 94, E147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aremu, A.; Finnie, J.; Van Staden, J. Potential of South African medicinal plants used as anthelmintics–Their efficacy, safety concerns and reappraisal of current screening methods. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2012, 82, 134–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irum, S.; Ahmed, H.; Mirza, B.; Donskow-Łysoniewska, K.; Muhammad, A.; Qayyum, M.; Simsek, S. In vitro and in vivo anthelmintic activity of extracts from Artemisia parviflora and A. sieversiana. Helminthologia 2017, 54, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenebe, S.; Feyera, T.; Assefa, S. In vitro anthelmintic activity of crude extracts of aerial parts of Cissus quadrangularis L. and leaves of Schinus molle L. against Haemonchus contortus. Biomed. Res. Int. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiegler, V.; Hensel, A.; Seggewiß, J.; Lubisch, M.; Liebau, E. Transcriptome analysis reveals molecular anthelmintic effects of procyanidins in C. elegans. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0184656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambodo, P.; Prastowo, J.; Kurniasih, K.; Indarjulianto, S. In vitro potential anthelmintic activity of Biophytum petersianum on Haemonchus contortus. Vet. World. 2018, 11, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thooyavan, G.; Kathikeyan, J.; Govindarajalu, B. Anthelmintic activity of Abutilon indicum leaf extract on sheep tapeworm Moniezia expansa in vitro. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 2018, 7, 317–321. [Google Scholar]

- Zangueu, C.B.; Olounlade, A.P.; Ossokomack, M.; Djouatsa, Y.N.N.; Alowanou, G.G.; Azebaze, A.G.B.; Llorent-Martínez, E.J.; de Córdova, M.L.F.; Dongmo, A.B.; Hounzangbe-Adote, M.S. In vitro effects of aqueous extract from Maytenus senegalensis (Lam.) Exell stem bark on egg hatching, larval migration and adult worms of Haemonchus contortus. BMC Vet. Res. 2018, 14, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braga de Oliveira, M.I.; Rodrigues Brandão, F.; Rocha da Silva, M.J.; Carvalho Rosa, M.; Santana Farias, C.F.; Silva dos Santos, D.; Majolo, C.; Oliveira, M.R.d.; Chaves, F.C.M.; Bizzo, H.R. In vitro anthelmintic efficacy of essential oils in the control of Neoechinorhynchus buttnerae, an endoparasite of Colossoma macropomum. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2021, 33, 509–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, M.A.; Qamar, W.; Yousaf, S.; Mehreen, U.; Shahid, Z.; Khan, M.K.; Qamar, M.F.; Kamran, M. In vitro experiments revealed the anthelmintic potential of herbal complex against Haemonchus contortus. Pak. Vet. J. 2019, 40, 271–273. [Google Scholar]

- Salgado, J.A.; Santos, C.d.P. Overview of anthelmintic resistance of gastrointestinal nematodes of small ruminants in Brazil. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2016, 25, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Samson-Himmelstjerna, G. Molecular diagnosis of anthelmintic resistance. Vet. Parasitol. 2006, 136, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demeler, J.; Küttler, U.; El-Abdellati, A.; Stafford, K.; Rydzik, A.; Varady, M.; Kenyon, F.; Coles, G.; Höglund, J.; Jackson, F. Standardization of the larval migration inhibition test for the detection of resistance to ivermectin in gastro intestinal nematodes of ruminants. Vet. Parasitol. 2010, 174, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beech, R.; Skuce, P.; Bartley, D.; Martin, R.; Prichard, R.; Gilleard, J. Anthelmintic resistance: Markers for resistance, or susceptibility? Parasitology 2011, 138, 160–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demeler, J.; Küttler, U.; von Samson-Himmelstjerna, G. Adaptation and evaluation of three different in vitro tests for the detection of resistance to anthelmintics in gastro intestinal nematodes of cattle. Vet. Parasitol. 2010, 170, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, R.M. Drug resistance in nematodes of veterinary importance: A status report. Trends Parasitol. 2004, 20, 477–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukherjee, N.; Mukherjee, S.; Saini, P.; Roy, P.; P Sinha Babu, S. Phenolics and terpenoids; the promising new search for anthelmintics: A critical review. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2016, 16, 1415–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramirez, B.; Bickle, Q.; Yousif, F.; Fakorede, F.; Mouries, M.-A.; Nwaka, S. Schistosomes: Challenges in compound screening. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2007, 2, S53–S61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geary, T.G.; Sakanari, J.A.; Caffrey, C.R. Anthelmintic drug discovery: Into the future. J. Parasitol. 2015, 101, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castelli, M.V.; Lodeyro, A.F.; Malheiros, A.; Zacchino, S.A.; Roveri, O.A. Inhibition of the mitochondrial ATP synthesis by polygodial, a naturally occurring dialdehyde unsaturated sesquiterpene. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2005, 70, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tritten, L.; Braissant, O.; Keiser, J. Comparison of novel and existing tools for studying drug sensitivity against the hookworm Ancylostoma ceylanicum in vitro. Parasitol. 2012, 139, 348–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman, D.J.; Cragg, G.M.; Kingston, D.G. Natural products as pharmaceuticals and sources for lead structures. Pract. Med. Chem. 2008, 159–186. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, D.J.; Cragg, G.M. Natural products as sources of new drugs over the last 25 years. J. Nat. Prod. 2007, 70, 461–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Bustos, J.F.; Sleebs, B.E.; Gasser, R.B. An appraisal of natural products active against parasitic nematodes of animals. Parasit Vectors. 2019, 12, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).