1. Introduction

Alta, the exhausted warrior at the center of Ivy Road’s Wanderstop, explains in the cinematic opening cutscene how hard she trained, how thoroughly she defeated all opponents, and how, despite it all, she has begun to lose fight after fight. Tortured by this unacceptable failure, Alta begins the game racing through a forest to find a legendary warrior who can help her get back on track. But she keeps slowing down, unable to keep running. The player gets their first choice: “Rest a moment” or “Keep Moving.” If the player chooses to keep moving, Alta’s self-hating internal monologue starts right back up: “I was lazy, I let myself get complacent. I have to ensure it never happens again. That’s all that matters.” Eventually, she runs until she collapses.

When she wakes, she’s sitting on a bench next to Boro, a kind tea-maker who wears an apron and holds a wooden spoon. Alta tries immediately and repeatedly to get back to her mission—run to the forest, find her trainer, push herself until she starts winning again—but it doesn’t work. If the player tries to push her the way she demands, she will keep collapsing and returning to the bench. Boro offers another option: “What is there to lose by spending a few easy minutes making tea?” He says the choice “is entirely up to you. Please take your time and be well,” but the player can’t effectively choose another option. Alta can run around the vibrant clearing or try the forest path as many times as she likes, but the result is the same. Physically, she cannot keep going, and therefore, she must stop.

Wanderstop was created by the new studio Ivy Road, made up of Davey Wreden (

The Stanley Parable,

The Beginner’s Guide), Karla Zimonja (who directed

Gone Home, produced

Tacoma, and co-wrote

Wanderstop), and C418 (who, among other accomplishments, did the music and sound design for

Minecraft). In other words, Ivy Road is composed of legendary indie videogame creators, artists who know what it’s like to be driven to succeed at the height of their chosen fields. Wreden has spoken explicitly about his mental health and the major depressive episode he experienced after the surprise mega-success of his first game,

The Stanley Parable (

Wreden 2015). Especially because Wreden plays a character named Davey Wreden in

The Beginner’s Guide, a previous game that also explores the intersection between creative drive, accomplishment, and depression, players may come to

Wanderstop with the impression that the burnout depicted in the game is semi-autobiographical in Wreden’s case.

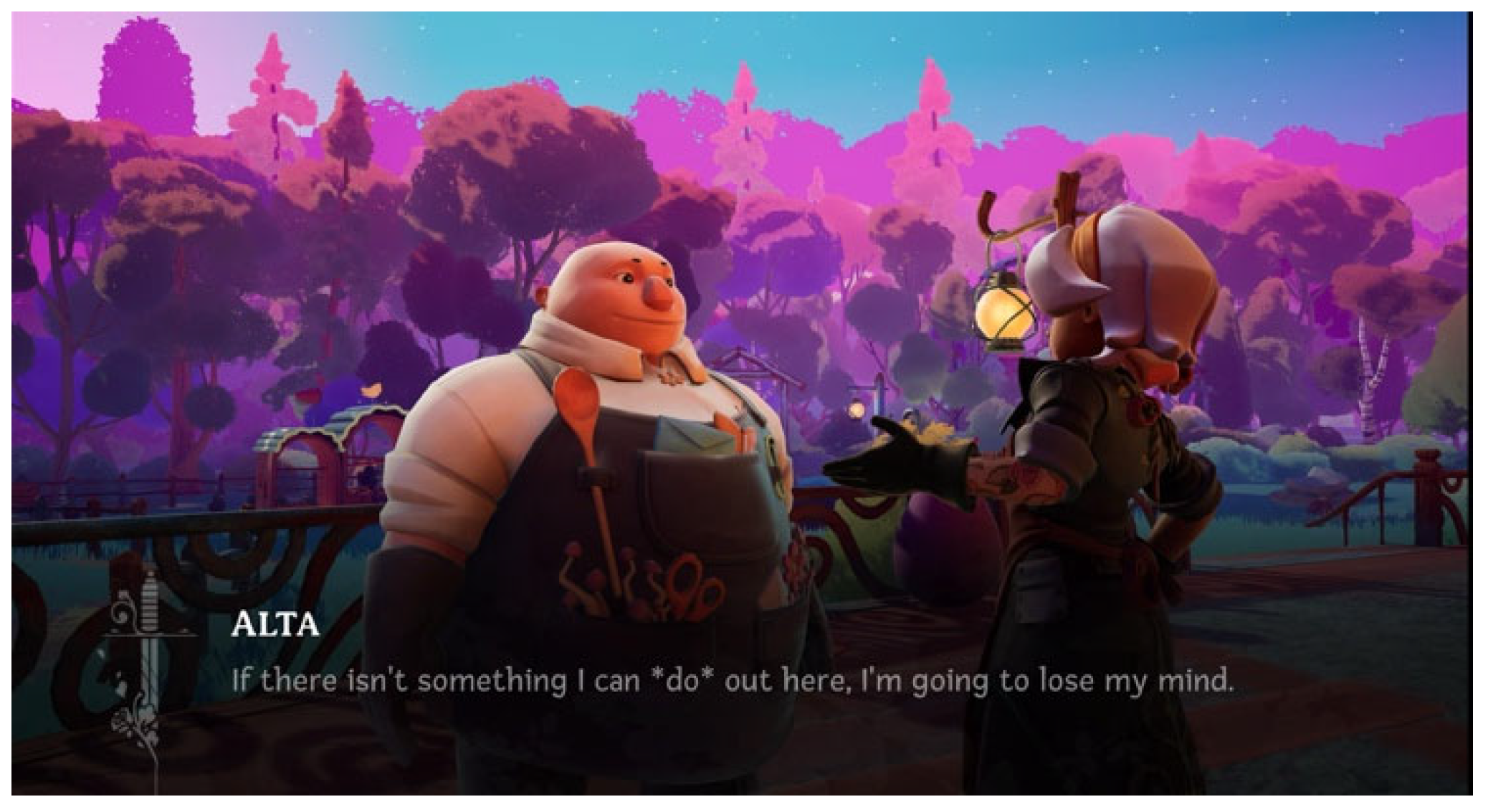

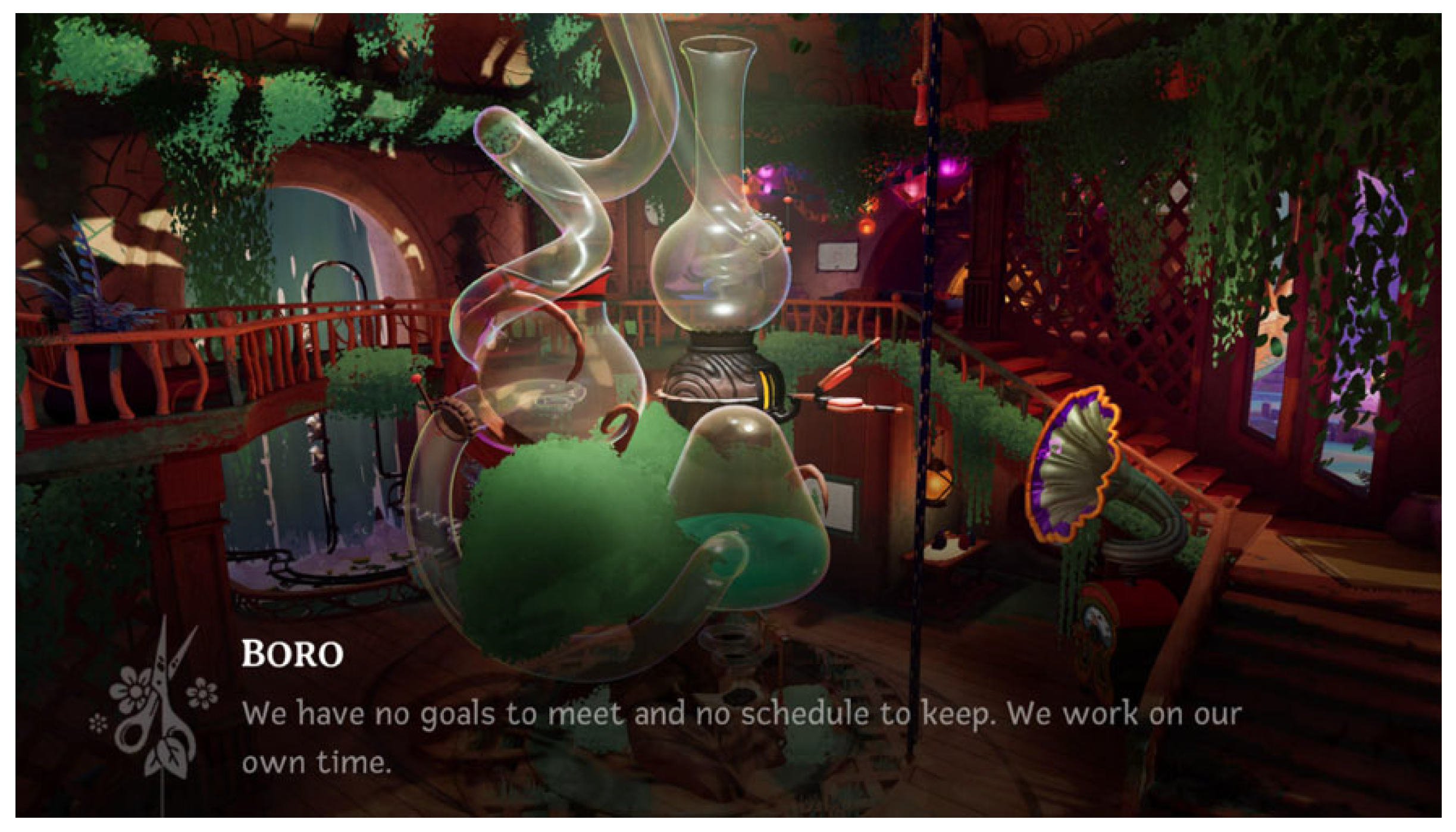

Our player character Alta really doesn’t love the idea of making tea or any of the self-directed, untimed components of the process: collecting tea plants, drying the tea, growing the flavoring ingredients, chatting with the customers. Grumpily, however, she agrees to learn to make tea and then tries to be excellent at a task that acknowledges simple completion rather than perfection. She tries too hard to help the tea shop customers, bullying them to order tea so that she can have the comfort of an accomplishable task rather than the much more amorphous and uncertain pleasure of personal connection. The player, too, might be relating with Alta’s annoyance at the game’s lack of defined goals. Alta can clearly identify her problem: she keeps losing fights. If the player thinks just a bit more abstractly, the exhaustion, burnout, and workaholism that have led her here might be the actual problem to solve. But either way, what can she (or we)

do about it? What can the player

do, what

action can they take to ameliorate this problem? As Alta tells Boro, “If there isn’t something I can *do* out here, I’m going to lose my mind” (

Figure 1). Despite the charming pink trees and Boro’s sweet calm, the “implied player” feels just as frustrated (

Aarseth 2007). Throughout

Wanderstop, Alta is framed as an emotional stand-in for a disgruntled player who would prefer to be playing a combat-oriented game, the same way that Alta would prefer still to be living her combat-oriented life. The implied player doesn’t want to be trapped in a cozy game any more than Alta wants to be too weak to leave Wanderstop.

So, what can the player do? They can wander and they can stop. Wanderstop, like Minecraft, is a game that announces in its title the two verbs in its core game loop. As Anthropy and Clark write in A Game Design Vocabulary,

“Games are made of rules. Verbs…are the rules that give the player liberty to interact with the other rules of the game…Rules are how we [the game designers] communicate. Verbs are the rules that allow [the player] to communicate back. The game is a dialogue between game and player, and the rules we design are the vocabulary with which this conversation takes place”.

The verbs in a gameplay loop are the only way the player can engage with the world of the game. When players in a First Person Shooter open a door by shooting it, the action makes intuitive sense: the player’s core verb, the way they’ve been given to interact with this world, is shoot, and so shoot is the player’s sole way of communicating within a game even when there are other, more physically realistic ways to open doors. The core verbs of most videogames are well-defined, active activities—shoot, mine, jump, craft, run. But what to make of a game with the far more passive verbs of wander and stop?

In analyzing the game through these two primary verbs, I don’t mean to suggest there aren’t other verbs at play in Wanderstop, which is essentially a cozy game that critiques cozy games. As such, it works great as a cozy game, with all the homemaking activities typical to that genre—the play can plant, garden, prepare tea, drink tea, serve tea, wash dishes, talk, read, and decorate, among other tasks, and is often distracted into a series of entertaining side quests. But it feels as if the game offers so many small tasks in deference to Alta’s cranky discontentment, which masks her (and the player’s) deeper anxiety about what a lack of measurable objectives does to her need for meaning and purpose in her life. If she’s not doing something to move towards her goals, who is she? The game is interested in persuading Alta and her player to realize that they are asking the wrong question, but these small tasks serve a transitional function by gently giving the player time to get frustrated, have realizations, and reframe their conception of productivity until they understand how radical genuine coziness—genuine rest—would be.

Indeed, this profusion of small cozy tasks, rather than comforting the player with easy, light productivity in the way of most cozy games, instead confronts the player. Confrontational coziness, as I will explain in the

Section 1 of this article, jolts the player into presence, pushing them to pay attention to each task, each customer, each moment. To do so, the game must interrupt the player’s forward progress, stopping them again and again, until it becomes clear that these interruptions are the point of the game. Consequently, the

Section 2 of the paper analyzes

stop as a core game verb, grounding it within the interpretive frame of Degrowth, a social movement beginning in early 21st century France “as a project of voluntary societal shrinking of production and consumption aimed at social and ecological sustainability” (

Demaria et al. 2013, p. 192).

Wanderstop begins with a forced stop, a break in the narrative of Alta’s life, and then slowly makes it clear that this break will be permanent. The game argues that the limitations of this world (and our world) simply make constant upward growth an impossibility, such that the challenge of the game becomes grappling with acceptance rather than overcoming difficulty. Whereas most game verbs delineate actions the player wants to undertake,

Wanderstop gives us verbs we’d rather avoid, then gently shows us that, unfortunately, we cannot.

2. Wander

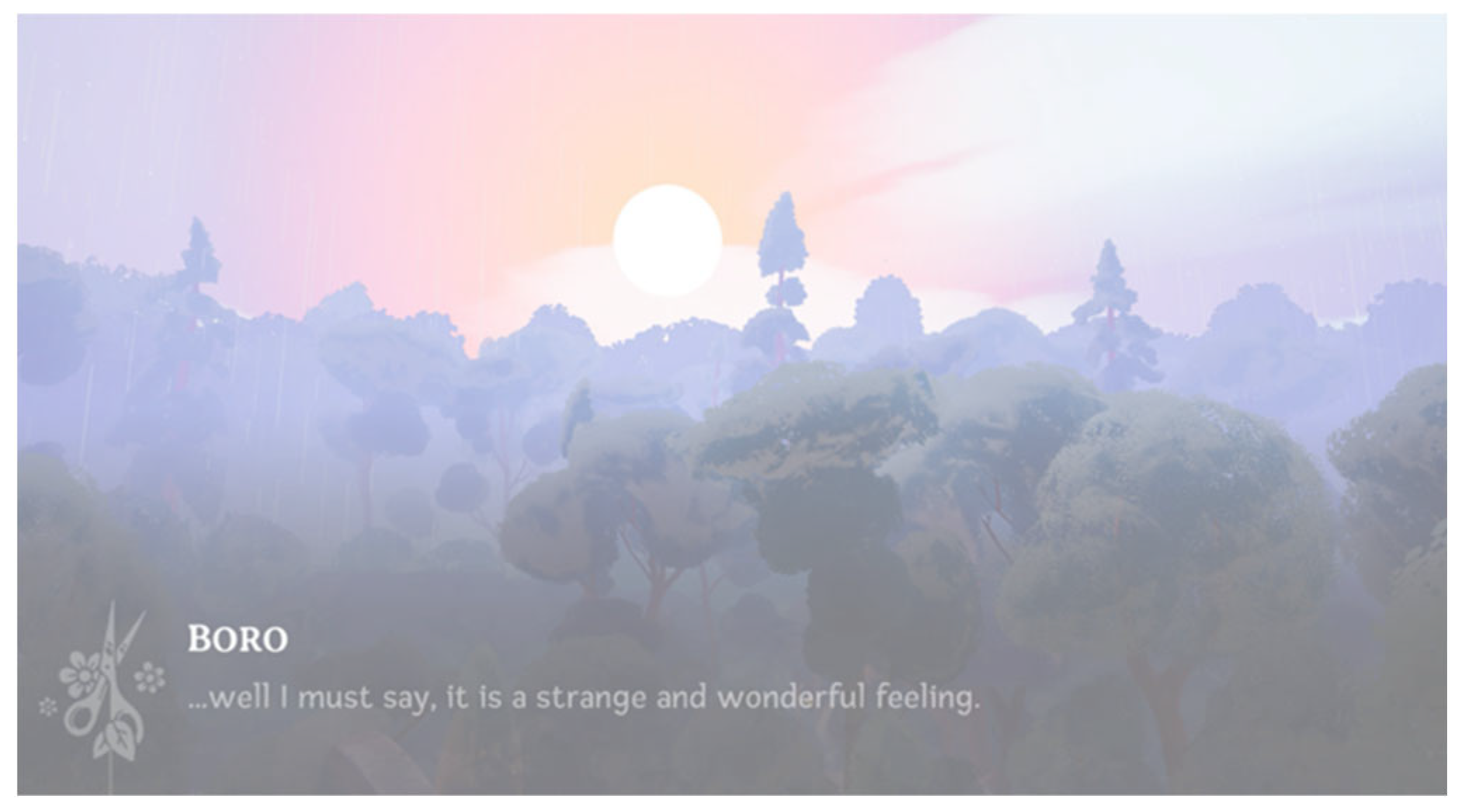

Alta might not want to be trapped in the purgatorial tea shop of

Wanderstop, but it is undeniably both an odd and beautiful place to experience (

Figure 2). Both its strangeness and its beauty matter for its designed provocation: to engage the player in a deep experience of wandering. In offering a familiar, comforting experience and then defamiliarizing the mundane,

Wanderstop grounds the player in presence. The player is deprived of the comfort of heading towards a goal and charged, instead, to live fully in the sequence of moments the game provides. It is in delivering this experience of presence that the game develops its first core verb,

wander.

On the surface, it’s clear how

wander is a main verb. Rather than engaging in goal-oriented linearity, the player curiously explores, spending their time meandering around the valley. To wander in a game can mean anything from “mimetic walking” to “something more like escaping, traversing, meandering, erring, resisting, returning, marching, or journeying” (

Kagen 2022, p. 3). But generally, it implies a goal-less, autotelic, introspective experience, a type of movement opposed to more efficient, directed ways of going through the world. Instead, wandering is a form of movement that attunes the wanderer to wherever they are at that moment, focusing on their present experience rather than a future point of arrival. When Alta runs straight ahead through the forest in the game’s opening scene, she has a goal to accomplish as quickly as possible. But she wakes and finds herself unable to move except through wandering around the valley—indirectly, contemplatively, unable to rush through the tea-making process, the interactions with the customers, and the five seasons that will not advance until she learns whatever she was meant to learn.

To make

wander a core verb, the game must ground the player’s experience in presence, to remind them that they are not traveling towards a destination but compelled to exist as and where they are. When wandering, the intent is not to get from one place to another with efficiency but to move step-by-step, the path of one’s journey animated not by a predetermined objective but by the moment-to-moment choice of where next to place one’s foot. In the long tradition of digressive texts, in a wandering game, “the player is not wandering away from the point; the wandering

is the point” (

Kagen 2022, p. 22). By attuning the walking body to wherever it currently is, rather than where it’s been or wherever it intends to go, wandering is about presence. Rebecca Solnit, in her exceptional book

Wanderlust, writes about the connection between wandering and thinking, noting that “unstructured, associative thinking is the kind most often connected to walking, and it suggests walking as not an analytical but an improvisational act” (

Solnit 2000, p. 21). Improvisation can only happen in, and in response to, the current moment. Solnit draws from

Husserl’s (

[1931] 1981) essay, “The World of the Living Present and the Constitution of the Surrounding World External to the Organism” to explain “walking as the experience by which we understand our body in relationship to the world…The body, he said, is our experience of what is always here, and the body in motion experiences the unity of all its parts as the continuous “here” that moves toward and through the various ‘theres’” (

Solnit 2000, p. 27). To wander is to be continuously present, no matter whether the wandering is done as a body the physical world or as a player character in a digital world.

The problem, however, is that Wanderstop is a cozy game, a genre whose purpose is to deliver a sensation of the familiar. Lulled into complacency by cute characters, a vividly lush valley, and gameplay focused on growing fruits and brewing teas, the player could be expected to relax into the experience rather than remain in a state of presence. But Wanderstop’s defamiliarization techniques, including one that I’m calling confrontational coziness, pricks the player into awareness of presence.

To understand how it does so, we need to backtrack into cozy game scholarship. The cozy game is characterized by “safety, abundance, and softness,” according to the definition established by Short et al.’s Project Horseshoe report in 2018. By safety, the authors explain there is an “absence of danger and risk… Familiarity, reliability, and one’s ability to be vulnerable and expressive without negative ramification all augment the feeling of safety….players [should] never feel the threat of coercion” (

Short et al. 2018). By abundance, they mean “lower level Maslow needs (food, shelter) are met or being met, providing space to work on higher needs….Nothing is lacking, pressing or imminent” (

Short et al. 2018). And by softness, the authors explain that cozy games have “strong aesthetic

signals that tell players they are in a

low stress environment….gentle and comforting stimulus….[these] stimuli impl[y] authenticity, sincerity, and humanity” (

Short et al. 2018).

Wanderstop obviously fits this profile of a cozy game. It includes no possibility of physical danger: no NPC will attack Alta, and the character cannot die through any means in the game. The familiar environment and activities—a tea shop and garden, customers to serve, the ever-placid presence of Boro—all actively encourage vulnerability and expression (which indeed receives positive feedback from the game rather than any negative response). On the question of abundance, Alta never needs to meet lower-level Maslow needs (she’s never hungry, tired, thirsty, in need of shelter, or in any physical danger) and can fully focus on needs on the higher steps on the hierarchy—connectedness, self-reflection, and self-actualization. As for softness, nearly all stimuli are adorable and promise a low-stress environment: the lusciously colored landscape of the valley, filled with whimsical plants, the chicken-like pluffins, the harmonious soundtrack, etc.

Games that index the hallmarks of coziness, however, are not uniformly comfortable. A common way that cozy games can tip into discomfort is through their association with the uncanny (or, in its German original, the

unheimlich (un-home-like)): the unsettling sensation that something that seems intimate and familiar is not quite right. As John Sanders has written on the concept of the haunted cartridge, the uncanny surfaces when errors, glitches, and a general sense of wrongness enter nostalgic or seemingly gentle games, “distorting once familiar digital spaces with the disquieting efficiency of an unseen hand”(

Sanders 2018, p. 135). We can see games like

Strange Horticulture as this kind of strange-cozy amalgamation, featuring many of the indicia of coziness—rain outside, cat snoozing in the window, an unkillable player character, so many plants, a chatty plant-shop setting—but jolted into an unsettling, uncanny realm by the hybrid animal-plant monster that’s been called from the netherworld to terrorize the community (

Minnen and Kagen 2026). Agata Waszkiewicz and Martyna Bakun have pointed to a disjoint between the cozy aesthetics and the serious, difficult content frequently featured in cozy games (like Shane’s depression and suicidal ideation in

Stardew Valley, Henry’s struggle to process his wife’s early onset dementia and death in

Firewatch, or Mae’s post-college disaffection and ennui in

Night in the Woods) (

Waszkiewicz and Bakun 2020). They accordingly categorize “three types of relationship between cozy aesthetics and its narrative function or impact:

coherent, where cozy aesthetics accompany cozy message;

dissonant, where cozy aesthetics are employed in order to introduce difficult themes mostly relating to mental health issues; and

situational, where coziness is a quality of a singular sequence rather than the entire game” (

Waszkiewicz and Bakun 2020, p. 233). In a dissonant cozy game, the game’s coziness, like a spoonful of sugar, helps the challenging themes go down easier.

That said, recent scholarship on cozy games has admitted that “cozy game” as a popular and academic signifier has been watered down to the point where the term is, if not meaningless, then “widely variable, socially constructed, and often personal” (

Boudreau et al. 2025, p. 2645).

de Pan and Bosman (

2024, p. 4) contend that “so much of what defines cozy games is dependent on a player’s personal experience of coziness,” such that the term becomes an expression of individual taste rather than a clear genre distinction. Boudreau, Consalvo, and Phelps acknowledge that, “while there are core elements that could be implemented to meet the fundamental characteristics of what makes a game cozy, there is no consensus between game designers, academics, game and mainstream press, and most importantly, the player and fanbase of what constitutes a fully defined, pure ‘cozy game’” (

Boudreau et al. 2025, p. 2653). And Waszkiewicz and Tymińska note that, while “cozy aesthetics are quite unmistakable,” every aspect of a cozy game beyond aesthetics is negotiable—flexibly identified as cozy or not depending on player and community preference (

Waszkiewicz and Tymińska 2024, p. 8). The dream of a pure definition suffers from the slippage between ‘cozy game’ and ‘game that comforts me,’ the latter of which is dependent on a player’s familiarity, nostalgia, and inclination rather than particular qualities of a game.

In all of these cases, however, most scholars seem to agree that the coziness is not the uncomfortable part. Plenty of cozy games piquantly provide a tension between uncozy themes—mental health struggles, light uncanny horror—and cozy aesthetics. But with Wanderstop, we encounter a kind of coziness that intends to confront rather than comfort, delivering an experience of such extreme safety, abundance, and softness that the player feels uncomfortable rather than eased. In other words, the coziness is not designed to support the player encountering uncomfortable topics; the coziness itself is used to make the player uncomfortable, to challenge the player to confront the paradigms that brought about Alta’s breakdown in the first place. Instead of a comfort, the coziness becomes a confrontation. The game offers so much safety that Alta cannot even lift her sword, much less use it to fight against danger and risk, an overabundance of safety that eventually comes to a head when a customer, Ren, who idolizes Alta for her past victories in battle, asks her to fight him for training, and she must painfully admit that she cannot. The game’s safety has the feeling of a padded room in a psychiatric hospital. In terms of abundance, the valley’s provisions for basic needs like food, drink, and shelter mean that Alta is forced into a reckoning with self-reflection (by drinking cups of tea and monologuing about her past traumas and relationships), connectedness (by begrudgingly getting to know the customers well enough to serve them the drinks they need), and self-actualization (propelled resentfully through a transformative hero’s journey). And the truly gorgeous softness of the valley is, to Alta at the start of the game, a cloying misery that traps her and keeps her from her mission. Wanderstop is a cozy game that takes the elements of coziness so seriously that it forces its player and PC into an unpleasant confrontation with the real meaning of breakdown and rest. Short et al., in their original report, note that the safety of a cozy game should mean that “players never feel the threat of coercion” (2018). But what if the coercive force is the coziness itself?

In Wanderstop, what happens is that the confrontational coziness jolts the player into awareness, startling them into reconsidering what was previously mundane. Wanderstop’s sense of presence draws from the Russian futurist philosophy of Viktor Shklovksy, who famously argued that art’s function is to defamiliarize the ordinary and reattune people to the sensations of life, creating a sharp sense of presence:

“Habitualization devours work, clothes, furniture, one’s wife, and the fear of war. If the whole complex lives of many people go on unconsciously, then such lives are as if they had never been. And art exists that one may recover the sensation of life; it exists to make one feel things, to make the stone stony. The purpose of art is to impart the sensation of things as they are perceived and not as they are known. The technique of art is to make objects “unfamiliar,” to make forms difficult, to increase the difficulty and length of perception because the process of perception is an aesthetic end in itself and must be prolonged” (emphasis mine).

The repetitive activities of a cozy game often feel mundane or even, as

Alharthi et al. (

2018) have argued, boring. Players are habituated to performing the same activities over and over, and the repetition can be either soothing, mind-numbing, or both. But in

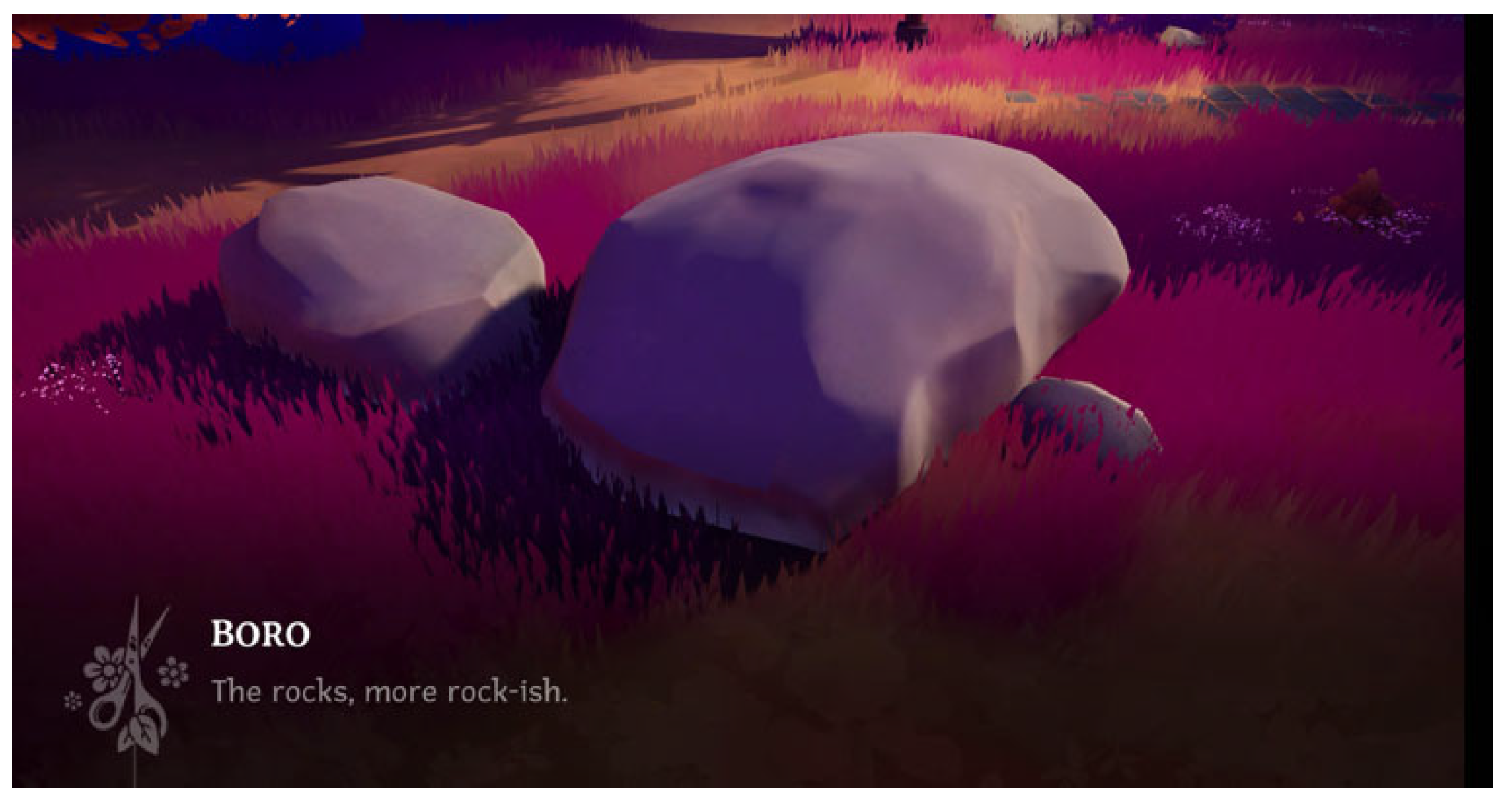

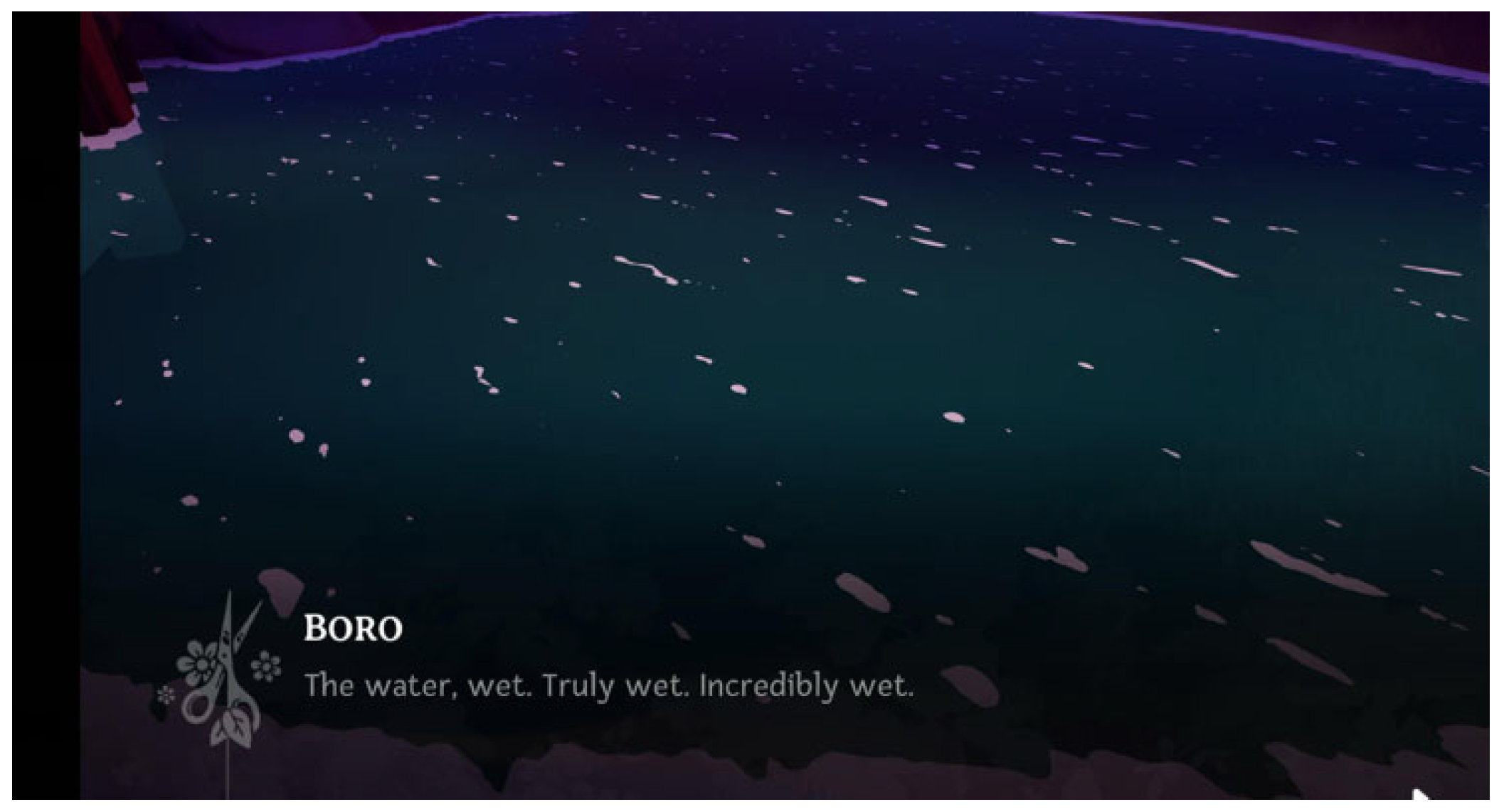

Wanderstop, the player is defamiliarized by the uncomfortable confrontation with coziness, resulting in the sense of presence Shklovsky describes as the purpose of art. As Boro says, as though quoting Shklovsky directly, “this makes the rocks, more rock-ish. The water, wet. Truly wet. Incredibly wet” (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4).

Wanderstop, with its self-consciously cottagecore simplicity and its affected emphasis on mundane everydayness, turns out to be the perfect vehicle for Shklovskian defamiliarization. Take the tea machine: a two-story tall, wildly curlicueing system of flasks and beakers, requiring a ladder to operate, perched precariously on a living tree (the excess tea waters the roots). To operate the machine, the player must puff the fire alive with a bellows, run up and down the ladder, grab the ingredients and toss them into the brewing flask (and be careful lest the pluffins steal them from the counters, and put a fresh mug under the spout after washing the dishes by them in a series of fish mouths running on a track under a waterfall. The whimsy of these appliances and the complicated set of steps make the chores fresh and fantastical, imbuing the mundane act of brewing tea with new awareness and appreciation (

Figure 5).

Drinking the tea is also an act of defamiliarization. When customers make their orders and Alta completes their drinks, she can also choose to pour herself a cup. Each new tea triggers a different reflection, and Alta’s monologue with each cup shares something intimate about her past, her feelings, her traumas—words that might be spoken to a dear friend, in a house of worship, or on a therapist’s couch. The camera zooms up and out to take in the whole valley, and the player loses control over their movement. Each cup of tea requires a pause, and each slow, quiet moment that follows separates the player briefly from their busy care tasks. They might have the chance to notice what they otherwise would not: a beautiful plant, some squabbling pluffins, Boro standing still on the porch. It is a meditative breath, another way that the game “makes the stone stony.” It also recalls

Scully-Blaker’s (

2019) description of the bench in

Animal Crossing: Pocket Camp where the player can sit and “wait for nothing in particular” as the camera pans out. Scully-Blaker describes this as “a moment to perform leisure for leisure’s sake within the virtual world of a videogame which is itself ostensibly a leisure object.”

1Finally, Alta cannot keep anything that she’s accomplished or acquired during a season, and this is fundamentally a defamiliarization of abundance. After each season, she opens her eyes to a clearing with a different color scheme and physical arrangement. The customers from the previous scene have disappeared (often never to return), the knickknacks and mugs she’s collected around the shop are no longer available, her painstakingly grown garden has vanished, and any multicolored pluffin or flower-planting configuration the player devised in the previous season are all wiped away. When Alta complains to Boro and wonders aloud whether there’s any purpose to beautifying the shop when the next season will just remove her decorations, he responds with a profound rhetorical question reminding the player that the point is to be present in the current season, not endlessly preparing for a future that may or may not arrive: “But Miss Alta…should we really stop making things beautiful simply because they may disappear in the future?” (

Figure 6) Again, the player is jolted into the experience of presence.

Wanderstop’s confrontational coziness draws from critiques of productivity culture, skewering the notion that cozy games are resistant to capitalist ideology by showing how much the comfort of cozy games typically relies on the satisfaction of completing task after task. As Andrea Andiloro has written, “cozy games are sometimes framed as reactions to broader political and environmental issues, and therefore discussed as coping, or even resistant mechanisms for life under capitalism as a socioeconomic structure responsible for those issues, providing alternatives to core capitalist tenets revolving around profit accumulation, constant growth, competition, and individualism” (

Andiloro 2024, p. 80). He points to many scholars who read cozy games as a radical challenge to capitalism and the valorization of productivity (

Fizek 2022;

Waszkiewicz and Bakun 2020;

Shin 2022;

Short et al. 2018;

Scully-Blaker 2019;

Linnet 2011;

Bille 2019). But, as he argues,

“cozy games do not challenge the capitalist status quo, but rather act as an ideological pressure relief valve for life under capitalism… it would be more appropriate to categorize them as breaks rather than rejections… Hygge and coziness are instances of ‘relaxing’ transgressions: small, consumptive pockets of time within life under capitalism that serve to ‘recharge one’s batteries’ and re-enter the production requirements of capital. These interludes do not represent resistance but are instead an expected, even welcomed, part of capitalist ideology, which encourages individuals to take pleasure in these harmless transgressions (

Žižek 2006)”.

From this perspective, we can see most cozy games as offering a fantastical respite from capitalism, but only the better to rejuvenate a worker for another day of clocking into work. Moreover, the rewards for productivity at the center of so many games is also comfortably available in cozy play; it’s just that, rather than enemies killed or new levels reached, a cozy gamer produces more and more crops for their farm, better relationships with their neighbors, or crafts more trinkets to sell at the market. A game like

Stardew Valley, typically considered a paradigmatic cozy game, can just as easily be seen as a bootstrappy reification of hypercapitalist industriousness, as Sydney Crowley has pointed out, than as a challenge to capitalism (

Crowley 2023).

Instead, the kind of coziness in

Wanderstop reads as a confrontation because it deeply challenges productivity culture. In this, its politics are related to Tricia Hersey’s Nap Ministry installation project, in which luxurious beds in public spaces invite people of color to rest (

Figure 7). Hersey’s subsequent book,

Rest is Resistance, further articulates the philosophy of the movement, standing against

“the toxic idea that we are resting to recharge and rejuvenate so we can be prepared to give more output to capitalism. …Our drive and obsession to always be in a state of ‘productivity’ leads us to the path of exhaustion, guilt, and shame. We falsely believe we are not doing enough and that we must always be guiding our lives toward more labor…We are not resting to be productive. We are resting simply because it is our divine right to do so”.

With its confrontational coziness, Wanderstop asks Alta and the player to fully internalize this shift in mindset. By the end of the game, it’s clear that Alta has not been resting so as to return to her old life, however much that was her initial goal; instead, she has been transformed, her goals altered, her veneration of grind culture toppled by her experiences in the valley. Her transformation is best symbolized by Ren, the customer who first idolizes her and then expresses his severe disappointment when she tells him she can’t go questing with him because she simply must rest. He sees it as a character failure, accuses her of quitting, and leaves the valley angrily. But soon after, Ren returns, having lost an arm during his travels, and even so, he says he intends to keep going. As a representative of Alta’s old mindset, Ren encapsulates how

“[g]rind culture has normalized pushing our bodies to the brink of destruction. We proudly proclaim showing up to work or an event despite an injury, sickness, or mental break. We are praised and rewarded for ignoring our body’s need for rest, care, and repair. The cycle of grinding like a machine continues and becomes internalized as the only way”.

Hersey’s rest is resistance framework resembles Rainforest Scully-Blaker’s theory of “radical slowness,” developed in his analysis of Animal Crossing: Pocket Camp. Scully-Blaker describes how slowness begins as an intentional value in earlier Animal Crossing games but becomes, in Pocket Camp, a forced wait-time designed to frustrate the player and entice them to buy Leaf Tokens (with real money) to avoid the wait. Scully-Blaker argues that therefore “slowness can be a site of resistance” and suggests engaging in “radical slowness”: “a deliberate failure to ‘keep up’ with the ever-accelerating rhythm of capitalist society as a political act. It is a reclamation of slowness from the financially-enforced division between taking one’s time and having one’s time taken through what might be called a virtual refusal of virtual labour” (Scully-Blaker 103).

While the player of Animal Crossing must misplay the game to engage in radical slowness, the player of Wanderstop cannot help but slow down. The entire game engages in “a deliberate failure to ‘keep up’ with the ever-accelerating rhythm of capitalist society,” with the site of resistance located in the player character’s frustrated irritation with enforced slowness rather than within an anti-capitalist player’s refusal to buy leaf tokens. Wanderstop does not offer but rather demands that the player find a way to live outside of Hersey’s grind culture. The next section explores how it does so by turning stop into a core verb.

3. Stop

As C. Thi Nguyen has argued, games “are special, as an art, because they engage with human practicality—with our ability to decide and do” (

Nguyen 2020, p. 6). When

Wanderstop frustrates Alta’s agency, the barrier is more poignant and painful than it would be in a book or film, art forms without the expectation of a participant’s agency. To design a game, Nguyen writes, is to “sculpt the shape of the activity” the player is engaged in (

Nguyen 2020, p. 18). Like a sculptor shapes clay, the game designer shapes agency, so much so that games become in their simplest evocation “a method for capturing forms of agency” (

Nguyen 2020, p. 25). Since the only meaningful expression of a player’s experience is the ways a game affords or denies the player agency, the player’s attempts to comprehend and enact their agency (in the form of finding and using their core verbs) becomes more understandably existential. With

Wanderstop, the player is primarily denied rather than afforded agency, blocked again and again from

doing and guided instead towards a nuanced kind of

not doing.

In elevating

stop to the level of an active game verb, the game captures the late Capitalist dilemma—even when what you’re doing is destroying you and the world around you, how do you stop? Alta must rethink her relationship to

doing over and over again, in a dozen different ways, with each new season in the Wanderstop café humbling her into reframing what she considers success.

Stop is a worthy challenge, difficult even to contemplate. “Alta, if we stop now, something horrible will happen,” her alter-ego threatens mid-way through the game (

Figure 8). Even as Alta passes out from overexertion consistently whenever she tries to run from the teashop, her fear of stopping remains stronger than her self-preservation until late in the game.

Wreden’s main two previous games,

The Stanley Parable and

The Beginner’s Guide, engage playfully with the expectation that players should be able, indeed entitled, to do things in a videogame, and the latter explicitly confronts and rejects that expectation.

2 In

The Beginner’s Guide, the narrator (voiced by the actual Davey Wreden) introduces himself as “Davey Wreden” and explains that the following piece is a compilation of short games made by his friend, Coda. Davey says that Coda has incomprehensibly stopped making games (seemingly out of depression), but if this collection gains approval, that could perhaps draw Coda from self-imposed retirement. Coda’s games are complex, abstract, and sometimes unplayable, but Wreden’s voiceover maintains a friendly narration throughout—respectfully introducing the mini-games, explaining what they mean, and tinkering with the code sometimes if Coda has produced something unplayable or just unpalatable (in one game, for example, the player is locked in a jail cell which, Wreden says, stayed locked for a full hour in Coda’s original. But he kindly opens it for us immediately, with a wink and a nod). As the games get weirder and sadder, Wreden starts to worry audibly about his friend. Coda’s depression seems to be increasing, and his games get stranger and less playable. This is why, Wreden says, he has sent out these games to colleagues, to give Coda a bit of reassurance and positive feedback. Coda then sends Davey one final, unplayable game that ends with short texts written on walls down a hallway:

“Dear Davey, Thank you for your interest in my games. I need to ask you not to speak to me anymore.” Another wall: “Would you stop taking my games and showing them to people against my wishes? [Stop] Giving them something that is not yours to give? [Stop] Violating the one boundary that keeps me safe?” And another: “Would you stop changing my games? Stop adding lampposts to them?” (emphasis mine)

Davey saw a problem (Coda’s social alienation and lack of professional success) and wanted to help solve that problem. As a game designer, he expected to be able to help by doing something—by exerting his own agency to make Coda’s games playable, comprehensible, and accessible to popular audience. But at the end, Coda explicitly tells Davey to stop rather than to do something else. The lampposts throughout the game have been one of the player’s few constants, the only way the player knows each mini-game is over. These lampposts were apparently added by Davey, one of the many ways he did rather than didn’t.

In Wanderstop, the player learns immediately that there is no alternative to stopping. However much Alta wants to keep going, she must keep stopping: stop leaving the clearing (she’ll only pass out in the forest), stop fighting, stop bullying the customers into ordering tea, stop trying to win this unwinnable experience, stop looking for a quick fix, stop hating herself, stop and have a cup of tea, stop rushing towards the end, stop trying to hold on to what she makes and does, stop picking all the fruits so fast they wither and die, stop misremembering, stop running away from what she’s done and face her past crimes, stop imagining she’ll be able to go back to her old life. Again, she does not choose any of this voluntarily; after experiencing a breakdown, she physically cannot do what she previously could and spends the game coming to terms with her new reality.

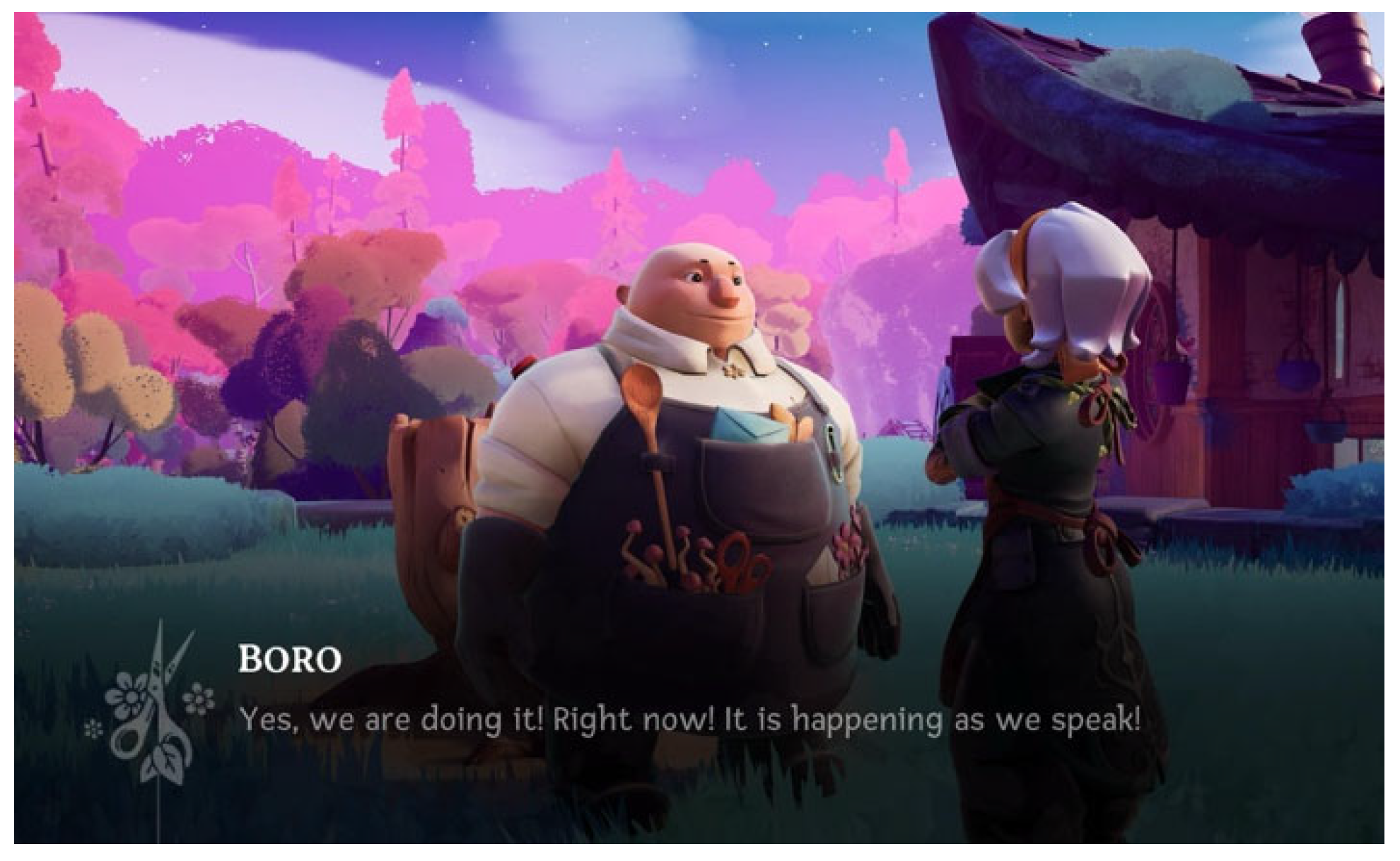

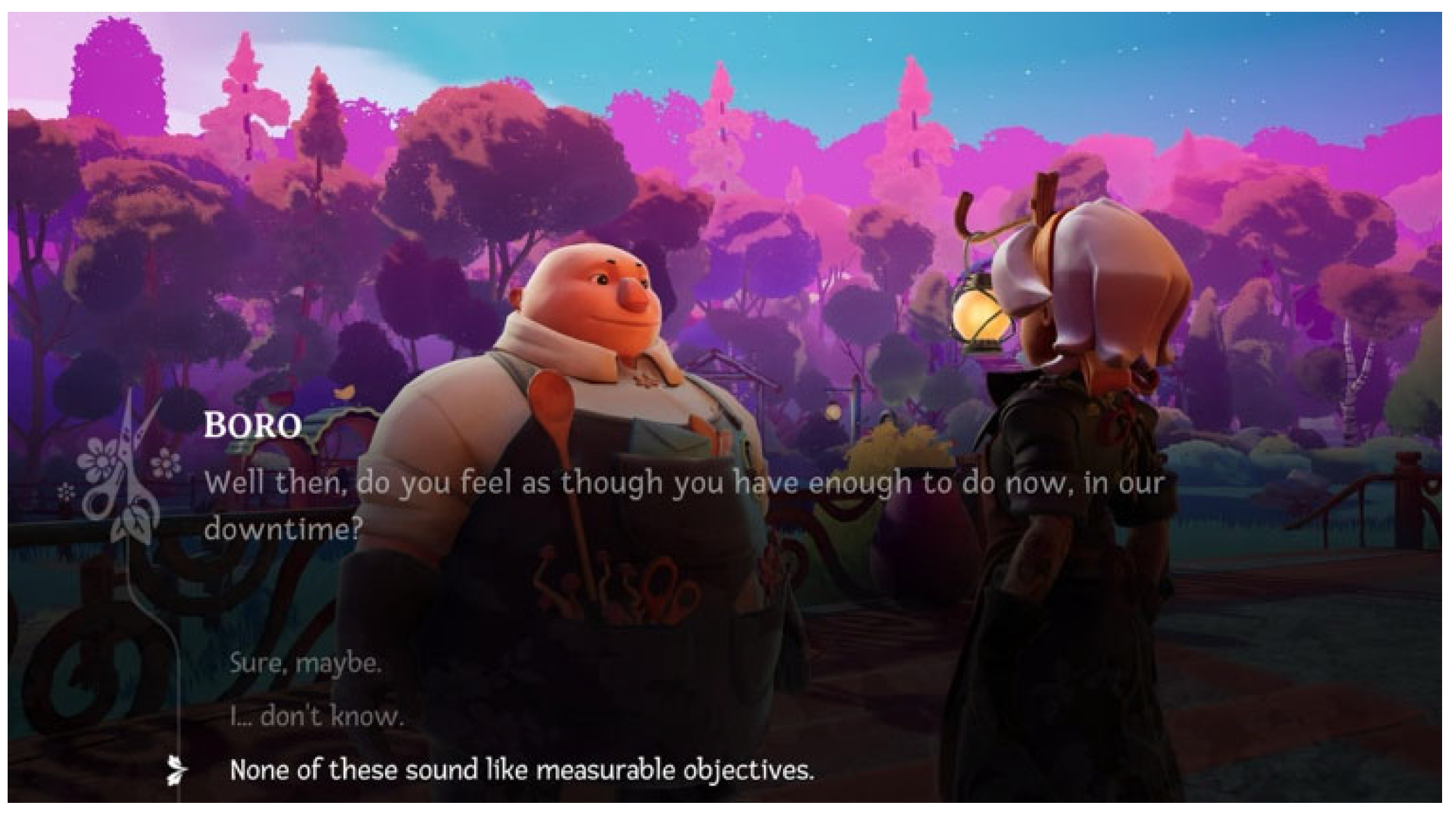

Wanderstop focuses the player’s attention on Alta’s thwarted agency, illustrated by her difficulty not doing what she would prefer to be doing and her confusion about what kind of agency—what verb—is hers. To start, Alta’s way of moving through the world is rough, fast, and violent, and the motion she uses to grab a teacup or harvest plants still looks like a warrior swiping a sword. Kill used to be her primary verb; we can see it in the way she executes her peaceable actions now, even though her objects are teacups and plants instead of axes and daggers. Then, as she recognizes that her goal now must be rest and recovery, Alta focuses on controlling the rules of recovery: customers must order tea, the tea must be possible to brew, and she wants to get it done as efficiently as possible. In other words, she’s reconciled herself to a new set of verbs—tend and befriend, the cozy game classic combo—and she’s frustrated when Boro tells her to stop badgering the customers into ordering tea. “My one responsibility is to put tea in people’s hands. That’s it,” Alta complains. But, again, the game resists letting her do the very thing it seems to be telling her to do. When we eventually learn the traumatic memory Alta has been suppressing—that she did already find her mentor Master Winters in the forest but stabbed her when Winters refused to help her train—we can understand both the horror of the act and its inevitability. Before coming to Wanderstop, Alta had only one core verb, the same verb that animates nearly every combat game: kill. Though that verb did not suit the interaction she was having with Winters, she had no other verb to pick.

Instead of finding a new verb, a new way of

doing using the active language she’s always used, she must practice

not doing instead, somehow reorienting herself to the intrinsic value of

not doing (and voicing the player’s parallel discomfort). One of her first difficulties is the lack of measurability in her existence at Wanderstop. She keeps asking Boro what she should be doing and his answer is often along the lines of “Yes, we are doing it! Right now! It is happening as we speak!”(

Figure 9) Alta isn’t satisfied: “What’s the value of living that way? How do you know it’s enough? There’s no indicator.” In another conversation, Boro explains “downtime” to Alta and asks her “do you feel as though you have enough to do now, in our downtime?” To which the player can pick between three responses: “Sure, maybe.” “I…don’t know.” And, my favorite, “None of these sound like measurable objectives” (

Figure 10).

Wanderstop holds space for Alta’s cranky discontentment, both in the snarky responses she can make to Boro’s monk-like non-answers and in the many smaller goals the game enables and encourages to help her find something measurable she can accomplish (my favorite I discovered: the first time Alta pours precisely the right amount of tea into a mug, the game rewards her with an acknowledgement). The anxious player can also use traditional user interface tools to orient themselves in their immediate goals (tapping R2 on a PS controller to highlight the location of Alta’s customers, who each have a symbol above their head if they have a live request, or looking up recipes in the field guide). But the game also steadily reminds the player that these tasks are not Alta’s real goal, nor is it finding Master Winters, as Alta would identify it during the first half of the game. Once when she says that goal aloud, Boro responds, “No, not that one. The bigger goal.” The bigger goal is to learn how to stop.

In its focus on stopping and retrenching into a more sustainable mode of existence, then,

Wanderstop exemplifies a degrowth game. Degrowth, as a social and theoretical movement, promotes radically reducing the consumption of resources and philosophically decouples measures of a country’s growth (like its GDP) from its success. Instead, the successful degrowth society is one that is imagined as balanced, sustainable, and post-capitalist, incorporating various social critiques (

Latouche 2009;

Schmelzer et al. 2022). It “is premised on the view that capitalism and its growth imperative are irreconcilable with the emergence of ecologically sustainable and socially equitable societies” (

Buch-Hansen 2025). Despite its utopian appeal, degrowth remains more theoretical than practiced, in part because growth remains so highly valued as a cultural norm. Through games, as Katherine Busa of the Degrowth Game Design Project has argued, we can work on the imaginative shift required to move from a growth to a degrowth society: “If our culture believes in limitless growth, we reinforce that belief whenever we play games….If we learn to love growth through games, then wouldn’t altering or downsizing or mutating games for degrowth help us understand and imagine what degrowth could mean?” (

Busa 2025).

Busa lays out several degrowth game principles which beautifully describe the ethic of

Wanderstop. “Degrowth games start at the end, not the beginning” (

Busa 2025). Alta begins at a moment when her career as a fighter is ending, though she is not yet ready to admit it. Once she does, her task is to begin from that ending. In a degrowth game, rather than building up in terms of accomplishments, acquisitions, upgrades, and skill trees, degrowth “is about working with what we already have…[it] is about care, cultivation, and collectivity” (

Busa 2025). We see these qualities in Alta’s work in the tea shop and garden, and especially in her interactions with the customers. Early on, she demands they order tea to give her a purpose. By the game’s ending, she has realized that her work with the customers is a kind of cultivation, another sort of plant that must be carefully tended and cannot be controlled or demanded. “In degrowth games,” Busa writes, “the winner never takes all. Hoarding is asking for it” (

Busa 2025). We can see this principle in how the game gently prevents her (and the player) from defaulting to a growth mentality by removing all inducement to hoard. If Alta tries to harvest fruit from the plants too frequently, the plants will stop giving fruit. If Alta works around this limitation and collects more fruits than she needs, the game gives her limited space to store them and, if she stores them in most usual locations, the pluffins will eventually eat them. Even if she does manage to stockpile fruits somewhere, the turn of the season will disappear her efforts. As Víctor Navarro-Remesal writes, a

“rhetoric of degrowth [in videogames]…would require systems and discourses that did not reward infinite accumulation, that pointed out the damage of excessive consumption in the whole virtual world, reward moderation, showed imbalances between regions, and/or recognized the waste produced by the action of the player. A system of limited resources that…encouraged players, by means of strategies of compassion, to be conscious of its limits”.

This is where the player finds themselves in

Wanderstop: encouraged by strategies of compassion (from Boro, from the customers, and eventually from Alta) to become conscious of the limits of this world and, consequently, to learn how to live within them. As Busa concludes, “sometimes degrowth isn’t a game, but a play style. The designer’s job is not to make growth impossible, but to make degrowth

meaningful” (

Busa 2025). Whether or not Alta or the player might like to acquire more fruits, artworks, or customers, it is her transition from a growth to a degrowth mindset that makes the game meaningful.