Abstract

We can trace the convergence of electronic literature and narrative games through a focus on critical methods and experiential frameworks rather than relying on typologies or ontologies. This article offers examples of digital literary works that we experience across a literary–ludic continuum. The first section traces some historical markers of convergence between electronic literature and narrative games with reference to conference keynotes from the institutional history of the Electronic Literature Organization (ELO). The next sections will present two case studies. The first, Kentucky Route Zero by Cardboard Computer is a narrative game that benefits from a literary-critical method and rewards interpretative insights. The second, This is a COVID-19 Announcement by Peter Wills, is an analysis of a playable simulation that indulges the pleasures of iterative ludic engagement against a backdrop of narrative (yet not plot-centric) comforts. Just as literature enriches games and games enrich literature, the critical methodologies and imaginative experiences they engender can be mutually productive when understood across a continuum of literary and ludic practice.

1. Introduction

While attending the media arts exhibition at the 2025 Electronic Literature Organization (ELO) conference, I noticed a table in the center of the room on which sat several black spheres amid a thicket of plugs and cables. The exhibited work was The Indistinguishable-from-Magic Eight Ball by Chris Arnold, in which he retrofitted classic fortune-telling Magic 8 Balls with computer processors. Each would run a randomized text generator when their built-in sensors registered rotation to their display. According to the curatorial description, one text “will provide readers with a prophecy in the style of Nostradamus,” one will return “a bilingual Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, and another is “a potential breakthrough in psychiatry, giving readers a diagnosis from the DSM-5.” I confess I do not recall exactly which messages I conjured up. I was too busy conjuring a ludologist’s lament that I had read roughly 25 years ago: “If I throw a ball at you I don’t expect you to drop it and wait until it starts telling stories” (Eskelinen 2001). Emerging from a debate about the place of narrative in the ascendant field of game studies, the statement indexed a larger polemic against the perceived failure of literary studies, theater studies, and film studies to approach computer games on their own terms and the imposition of narrative-centric frameworks with little regard to media-specificity. That polemic, both despite and because of its extremes, proved formative for game studies as a field and ludology as a critical practice. But in that moment of interfacing with Arnold’s exhibit (as I dared not drop the storytelling ball), I could not resist asking the following: have we come full (hermeneutic) circle? Or perhaps we have at least moved a few squares along the “haphazard hopscotch” of creative media’s perpetual present?1

A reflection on the convergence of electronic literature and narrative games is welcome and well-timed. In the contemporary media ecology, these strands of cultural production show not only a strengthening of family ties in terms of shared audiences and platforms in the present day, but also evoke, retrospectively, further connections in familial origins in their kindred pursuit of expressive computing. My starting point includes the assumptions that both narrative and play are fundamental frameworks for imaginative experience, rooted in what philosopher Kendall Walton calls our propensity for games of “make-believe” (Walton 1990). Both narrative and play have deep histories for humans in an evolutionary and anthropological sense and likely carry significant adaptive value. Both can be harnessed for art forms, and it is impossible to fully disentangle them in human activity. Fictional play, whether delivered in the form of novels, films, or video games, can provide, in Denis Dutton’s terms, “cognitive maps and regulative templates” that allow us to negotiate social and media terrain in the 21st century (Dutton 2009, p. 126).

In the spirit of family relationships, we might cast the art forms in question—print literature, electronic literature, and video games—in terms of first-born, middle-child, and last-born siblings. That ordering reflects the institutional imprint of those forms, of their associated bodies of criticism, and how they came to establish themselves in (or as) dedicated disciplinary areas or departments. As the first-born, “literature” maintains a serious disposition, conscious that it will need to be the model for those next in line; at the same time, it struggles with influence anxiety and a mortal fear of failure. It also remains the most structured and conservative of the siblings. The last-born, “game studies,” is the most outgoing and extroverted; it constantly seeks attention, takes risks, and engages in systematic manipulation in order to get its way. Stuck in the middle, “electronic literature” has learned to adapt on the fly and people-please. But even with its refined diplomatic streak, it harbors a sense of rebelliousness that betrays a latent need to stand out.

This exercise in (admittedly stereotypical and now outdated)2 psychological profiling transcends scholarly play: it underscores electronic literature’s precarious position on this timeline of academic and institutional domestication. It was not long after the field of “hypertext” and what came to called electronic literature gained a foothold in academia (with some luminaries framing it as the “word’s revenge on television”) (see Joyce 1995, p. 47) that game studies entered its first year—at least nominally—with the launch of the Game Studies journal as “the first academic, peer-reviewed journal dedicated to computer game studies” (Aarseth 2001). While electronic literature thus faced rejection from its older sibling as not literary enough, its younger sibling saw it as too literary, too entrenched in a serious Modernist sensibility, and was likewise reluctant to play. Nonetheless, as everyone grew up and grew more comfortable in their young adult identities, electronic literature established lasting kindred bonds with both. They all came to better appreciate how games can be “serious” (which is to say pedagogical, political, activist, and literary). And after the first-born shared his favorite book, Warren Motte’s Playtexts: Ludics in Contemporary Literature (Motte 1995), they were all reminded how literature can be playful, which is also to say game-like and equally politicized. At the same time, they each continued to cultivate their own ways of doing things—their own methodologies.

My contribution to the present collection will focus on critical methods and experiential frameworks rather than typologies and ontologies of stories and games in the digital domain. In doing so, I acknowledge the so-called narrative (or interactive) paradox (see Aylett 2000; Ryan 2018), which casts the pleasure of plot-centric storytelling and the pleasure of player agency in inverse—if not adverse—relation; but I see this paradox as a productive and indelible tension and, therefore, do not endeavor to resolve it (see Louchart and Aylett 2003) or see the need to do so.3 I will offer examples of digital literary works that we experience across a continuum running from ludic to literary, or configurative to interpretive—and often back again. The first section traces some historical markers of convergence between electronic literature and narrative games. With reference to conference keynotes from the institutional history of the Electronic Literature Organization (ELO), I will survey the field’s ongoing negotiation of both literary and gaming cultures. I will suggest that “electronic literature” itself continues to function as a metaphor and meta-commentary on the convergence of literary and ludic practice. The next sections will present two case studies. The first, Kentucky Route Zero (Cardboard Computer 2013–2020), is a narrative game that benefits from a literary-critical method and rewards interpretative insights. Focusing on the dialogue mechanic, I develop a notion of narrative experientiality in which choice mechanics are read not as mutually exclusive outcomes but rather as a performance of social cognition. The second case is an analysis of a playable simulation that indulges the pleasures of iterative ludic engagement against a backdrop of narrative (yet not plot-centric) comforts. Made in the Twine authoring platform, This is a COVID-19 Announcement (Wills 2021) illustrates how the hermeneutic practice of reading for the plot is superseded by the practice of playing for higher systematic understanding. Just as literature enriches games and games enrich literature, the critical methodologies and imaginative experiences they engender can be mutually productive when understood across a continuum of literary and ludic practice.

2. E-Literary Self-Consciousness

Unlike, say, geologists who intuit on a concrete level what the object of their field of study is, scholars of electronic literature spend some amount of cognitive overhead explaining what electronic literature is to the uninitiated.4 We then turn that preoccupation inward in an attempt to explain it to ourselves, through dedicated debates, articles, and conference panels that have spawned what we might call an identity crisis genre in their own right. Yet no sooner have we done that than ever-new digital tools and platforms expand the field and force a rethink. It cycles in a heuristically healthy and inclusive rather than vicious way.

My focus, however, falls instead on what electronic literature has historically and strategically defined itself in relation to, and my method for this task makes recourse to keynote addresses over the course of the Electronic Literature Organization’s conference history. The ELO most certainly has valuable institutional peers and parallels. For example, the community that has coalesced around the International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling (ICIDS) has direct relevance for narrative-theoretical approaches to electronic literature. Using disciplinary inputs ranging from media studies and literary theory to cybernetics and systems theory—and the foundational digital-literary work of Murray (1997) in particular—scholar Harmut Koenitz has developed a framework for “interactive digital narrative” (IDN) (Koenitz 2023). Arguably, both electronic literature and IDN are vectors for a convergence of narratives and games. They diverge, nonetheless, in significant ways. Electronic literature remains broader in terms of aesthetics and genre: it includes non-narrative forms (such as digital poetry and code poetics, chatbots and generative texts that are not story-driven, and digital art installations). IDN, at the same time, remains broader in mode and medium—it is medium-agnostic in its systems-oriented approach. (My focus falls on ELO given its longer institutional history—of roughly a decade—and given the concerns of this Special Issue. But I suggest the same methodology of keynote barometers could be applied productively to an analysis of ICIDS’ own intellectual and institutional evolution in another 10 years or so).

Keynotes, in their degree of self-consciousness with regard to the state of their field, can serve as barometers of the cultural convergence between electronic literature and narrative or literary games. Through this lens, we can demarcate major phases or indeed concerns that ELO scholars have sought to confront. We might refer to these in shorthand as legitimization, in relation to the academy and the literary establishment, and integration, when articulating a concerted alignment to video games and gaming cultures, with the plural underscoring the range of cultures from commercial to open-source or anti-establishment movements inflected by digital literary practice. Any approach along these lines is necessarily patchy and incomplete, and will to some degree reflect overlapping and continuing historical phases rather than discrete and punctual ones.5 Yet the idea is that zooming in on these transformations reveals something useful about disciplinary self-consciousness and strategic negotiation.

The first academic conference of the ELO was, in fact, reflexively titled “The State of the Arts.” That 2002 event featured N. Katherine Hayles, Robert Coover, and publisher Jason Epstein as keynotes. Hayles’s address celebrated the promise of electronic literature but at the same time called on critics to abandon sweeping claims for radically reconfigured (digital) subjectivity. It was time to undertake the “next step” of “micro-analyses” of individual works that demonstrate how “their precise and rigorous stylistic and technological effects” actually manifest such reconfigured subjectivity (Hayles 2002).6 Although her call led to a raft of “second wave” digital literary criticism,7 it is worth noting this was carried out under the auspices of traditional literary critical foundations—of close reading—that was sure to be intelligible to the literary establishment. Coover’s address reflected his concern with the fate of storytelling in full-blown multimedia environments, so much so that “the word” became “the hero” of his keynote. He noted that in his electronic writing workshops at Brown University,

The word is still privileged, for in our perversely archaic love of storytelling and poetry, we cherish still the peculiar qualities of our restless little hero, its intimacy, his subtlety, her vast expressive range, and through its very transparency, his power to stimulate thought and imagination, and then to reflect upon what she has done. It’s true that the whole world is a text to be read, but it’s also true that written literary text, standing alone on the tablet, the parchment, the page, the screen, is a unique and wondrous thing, nor so fragile as one might fear.(Coover 2002)

Coover’s ambivalence over the fate of the word, moreover, underscores an equally ambivalent coupling of electronic literature and the literary tradition of postmodernism—a tradition in which Coover himself is typically cast. Despite the text-dominant and comparably long-form immersivity of some hypertext fiction, not to mention the Norton anthology’s inclusion of hypertext fiction excerpts in its 1998 collection of Postmodern American Fiction, the association was problematic. The postmodernist fiction stratagem foregrounds the artifice of language and defamiliarizes a medium whose conventions have long been internalized by print culture. By contrast, electronic literature was starting with “new media” that were already defamiliarized. (We can recall that Lyotard’s The Postmodern Condition warned of the dehumanizing effects of technoculture (Lyotard [1979] 1984).) Hypertext author Michael Joyce and postmodernist author John Barth both disavowed the idea of electronic literature as postmodernist by default. For Joyce, postmodernism came to suggest “flatness, lackluster bubbles from day-old champagne” (Joyce 2000, p. 127), whereas for Barth, notwithstanding his decades-long fascination with it, framed hypertext as an “intermedia” gimmick.8 In any case, electronic literature was not to enter the literary establishment by default through the postmodernist side door.

Matthew Kirschenbaum refers directly to the crisis of literary legitimization in his 2017 ELO keynote address and suggests that an e-literary engagement with “seriousness” inevitably facilitated its institutionalization. Careful to emphasize that this engagement went beyond hypertext’s own branding as “serious”, as reflected in the promotional tagline for early hypertext publisher Eastgate Systems, Kirschenbaum notes that “difficulty, seriousness, and conceptual density are all characteristics that have served to gain e-lit a firm institutional purchase in academia, where difficulty and seriousness are rewarded.” He adds that “the exceptionalism on which the electronic literature community has so often traded is completely normative in this wider institutional frame” (Kirschenbaum 2017). In the decade or so before Kirschenbaum’s (2017) retrospective take on the field and after N. Katherine Hayles’ second ELO keynote in 2007—in which she asked, “Is the Future of Electronic Literature the Future of the Literary?”—electronic literature had found homes in academia: in English and literary studies departments, media studies, art and design programs at first, then also under the rubric of digital humanities. In fact, by that stage, there was some evidence of an anti-establishment homecoming, this time in response to the instrumentalizing forces of the “digital humanities” juggernaut. As Illya Szilak puts it in her 2014 ELO keynote:

To a certain extent, digital literature has been locked up in an ivory tower of academia where it threatens to be crushed under the weighty designation of ‘digital humanities.’ It’s human to want legitimacy, but might I suggest that rather than agree to these terms legitimate and illegitimate, writers of digital literature seek to become ‘illegitimately legitimate’ or ‘legitimately illegitimate’ and in doing so, create an alternative, more open, fluid system for artmaking, criticism, education, and economic exchange.(Szilak 2015)9

From the formal announcement of its self-creation at the start of the millennium, game studies had also managed to create an academic identity to accompany what Espen Aarseth notably described as a billion-dollar industry without a dedicated research program (Aarseth 2001). But for the ELO, in its formative stages, games were a love that dared not speak its name. In fact, across the corpus of ELO keynotes, there was little mention of the word “game” itself before 2014.10

Digital literary scholars invested in game narratives operated as if on a separate, albeit parallel track. Some wrote speculatively on a “literary turn” in contemporary video games (Ciccoricco 2007). In retrospect, we might identify a first literary turn, circa 2005, that was marked by a popular awakening to story in the mainstream industry—think Shadow of the Colossus (Ueda 2005), which laces moral ambiguity through its core gameplay, and God of War (Sony Computer Entertainment America 2005), which rewards level completion with narrative backstory (and features a vengeful demi-god warrior who still finds time to journal his thoughts and feelings). Then we might locate a second turn, circa 2012, driven more explicitly by social justice imperatives, political activism, and comparably more democratizing ideals in terms of cultural production and reception. The controversy of #gamergate and the rise of the Twine authoring platform (and Twine games such as Quinn’s (2013) Depression Quest) index such a movement. While some scholars of electronic literature were indulging the pleasures of getting “lost in” a game, so to speak, and taking a critical stance toward those story-driven games that would invite it, game studies was pursuing other priorities—other critical pleasures—at the start of the millennium. As Stuart Moulthrop wrote in 2004,

Like all so-called movements, the partisans of digital game theory or ludology comprise a loose and fractious community, but most share at least one premise. We feel that narrative in certain conventional senses—mainly defined by the theater, the novel, and cinema—no longer animates the work we find most interesting as creators and/or critics.(Moulthrop 2004)

A step change from around 2014 to 2020, however, reflects a more self-conscious institutional integration of games and game studies for the ELO. Szilak’s own keynote wove Interactive Fictions (a formal locus classicus of the story/game tension), indie games, and digital narratives into a discussion of “minor literary forms” of electronic literature. That same year, Astrid Ensslin codified a systematic approach to literary gaming in her landmark Literary Gaming (Ensslin 2014) that introduced the notion of a literary–ludic spectrum; she would deliver an ELO keynote in 2019 that similarly treated electronic literature and games as inseparable in name and operating along a continuum. As one crude measure of this step change, a keyword search for “game” in some form in the 2014 ELO conference program reveals two hits (one announcing the progressively consilient panel on “Literary Games”). By contrast, the 2015 ELO conference program returns nearly 200. That year, the conference featured a joint keynote by Moulthrop and Aarseth, which reflected that the ELO was now more than just game-curious; it was building critical infrastructure along the literary–ludic spectrum. A plenary panel at ELO 2016 continued the trend by highlighting the politically charged discourse around games and feminism.11

Three keynotes for ELO 2020 signaled the most overt engagement to date with game studies and the question of games as electronic literature. As a hypertext practitioner and hypertext theorist active in the decade before ELO’s “Year One” in 2021, and a scholar equally at home in literary theory and game studies, Moulthrop is among the best placed in telling this story—or playing this game—of convergence. His 2020 ELO keynote address, “The Hypertext Years”, adapts the authoring platform Twine as its mechanism to deliver an address of technocultural promise that also directly confronts troublesome “racial-cultural” moments along the way (Moulthrop 2020). Noah Wardrip-Fruin’s keynote, “Games, Hypertext, and Meaning,” asks what topics “games can meaningfully address,” and he applies his model of “operational logics” toward that end (Wardrip-Fruin 2020). In her keynote that year, Shira Chess’s “How to Play Like a Feminist in 2020” revisits her own book of that name in post-pandemic contexts and advocates for modes of “playful protest” and “radical play” (Chess 2020). This overt engagement continued in 2024, with Edmond Chang’s keynote challenging the “technonormativity” of digital texts, video games, code, and AI (Chang 2024). The ELO was now not only in a position to take video games as “seriously” (Kirschenbaum 2017) as it took itself, but it was also ready to describe certain commercial indie games as electronic literature—or at least meta-tag them as such—volume IV of the Electronic Literature Collection (Berens et al. 2022) includes Kentucky Route Zero (Cardboard Computer 2013–2020) and 80 Days (Inkle 2014).

In one sense, a focus on ELO keynotes is overdetermined given its inevitably narrow corpus; in another sense, the approach speaks to the core of the field’s perpetual drive for self- and re-definition. Citing narrative theorist Gérard Genette’s concept of paratext, Friedrich Block, in his 2017 ELO keynote, claimed that

Block’s observation is consistent with the way in which “electronic literature” functions semantically as a self-conscious metaphor and a meta-commentary on the convergence of literary and ludic practice.There would be no electronic literature without self-description, and that—much more than in ‘literature’ or ‘art’ as such—the social construction of ‘electronic literature’ is dominated by the paratextual, poetological or academic description of e-lit. This paratextual construction basically works with the ascription of the genre name ‘electronic literature’ and discursive descriptions or reflections [on] phenomena of artistic practice and has been institutionalized in no small part by the Electronic Literature Organization […].(Block 2017)

3. Dialogical Happenings

Although it would be futile to argue for any definitive categorical distinction between “electronic literature” and “narrative games,” it is possible to suggest they each yield distinct experiences and pleasures along a literary and ludic spectrum and call for different critical methodologies in turn. Even ostensibly opposing critical modes, moreover, can derive mutual benefit. For instance, Alan Liu’s notable Literature+ class demonstrated that we might first approach a work of classic literature such as a Shakespeare play by reconfiguring it as a “model, simulate, map, visualize, encode, text-analyze, blog, or redesign as a database, hypertext, multimedia construct, virtual world, or social network” (Liu 2017, p. 134).12 Such critical making can recursively yield new interpretations. Conversely, we might start with a playable simulation, such as Vi Hart and Nicky Case’s popular Parable of the Polygons (Hart and Case 2014), which explores structural racism and social segregation in housing neighborhoods, and see what a close reading of its variables or source data might yield. Such interpretative work might trigger new ways of playing.

For a more detailed case study, Kentucky Route Zero can illustrate how narrative games can serve as a playground for literary theorizing—and more specifically—cognitive literary analysis. It is a “point and click” adventure game released in installments between 2013 and 2020 and developed by Cardboard Computer; it is text-driven, with user interaction coming mainly in the form of dialogue choices. Players can point and click to direct the main player-character, delivery driver Conway, to various locations around the game’s monochromatic magic realist settings. We also point and click to interact with objects, including the navigation of Conway’s truck along the game’s schematic map. Players initiate dialogue sequences by clicking on the bubble tabs that appear over non-player characters. The same tabs can include an eye icon, which displays a narrative description when selected; for example, when selecting the eye icon over “Dog,” it returns “And old hound in a straw hat. Both have seen better days” (Act I, Scene I). Conway must make one final delivery to an address on “Route Zero,” which everyone appears to know about, but few know exactly how to get there. His labyrinthine search for the Zero serves as an analogue for those who find themselves lost in a bureaucratic and corporate abyss of a dystopian Americana. Kentucky Route Zero offers an arguably loaded example for analysis in that the game’s dialogic mechanic trains us to understand our decisions will not dramatically sway the plot; rather, they add texture and nuance to narrative in a manner that is often described in game reviews with analogies to “directing” a play.13 While the game certainly invites this reading, by way of parenthetical stage directions and its presentation in “acts” and “scenes,” there are other ways to read the dialogue we see and the choices we make. After all, we inevitably experience paths not taken, given that we read them in order to decide not to take them. It is plausible to read many of the decision points and dialogue trees in Kentucky Route Zero, however, as conveying what characters think but do not voice.

For example, in Act III, Conway is accompanied by Shannon, a TV repair specialist who is the first to join him in search of the Zero; Ezra, a precocious boy we meet in Act II who is estranged from his family (except for Julian, a giant eagle who he says is his brother); and musicians Junebug and Johnny, androids who defected from a work crew of robots manufactured by Consolidated Power to work the mines. Act III marks the transition from Conway driving along a ghostly highway into the even more surreal underground landscape of the Hall of the Mountain King—first by way of a bridge that has crumbled away from the road, then along a ramshackle boardwalk that takes players into the fire-lit and cathedral-like hall. There, we encounter the ageing techno-visionary Donald and his life’s work, the wildly ambitious and barely functional “Xanadu Project.” At one point during our exchange, he says, “Do you have any idea what it’s like to spend your life building something, then sit powerlessly as your work declines into ruin?” (Act III, Scene III). Here, players have four dialogue options, one for Conway, Shannon, Ezra, and Junebug:

CONWAY: I drive deliveries for a small antique shop, and we’re closing down.SHANNON: I fix TVs and I’m about to lose the lease on my workshop.EZRA: My family disappeared; Julian and me don’t know what to do.JUNEBUG: Not really. (Act III, Scene III)

In this scenario, it is possible to experience these lines not as mutually exclusive outcomes, but instead as exactly what each character has in mind to say. What happens in the actual fictional world, then, is simply that someone says what they are thinking before any of the others say what they are thinking to say. It is a familiar game of social cognition, where speed and status can contribute to a winning outcome, at least for those who wish to speak.

The same idea can work for single characters. At an earlier juncture, when Shannon asks about Donald’s software, players have two choices: (1) “You were about to tell us about the software,” which is the one I chose, or (2) “I’m just interested in the mold computer” (Act III, Scene III). Both choices trigger the same path from Donald explaining Xanadu, with only one line containing a minor variation differentiating them. Players can experience the two choices as options Shannon is effectively giving herself. Here again, rather than a mutually exclusive plot point, the dialogue offers two different ways she might engage Donald with varying degrees of propriety or discretion. The same approach can also account for instances where all the characters vocalize their given dialogue options, the player-character hears them in the gameworld, and the player must select one. Such is the case when playing the section that is structured as an Interactive Fiction game within the game, which is called Xanadu and narrated by Xanadu. At the computer terminal keyboard, Conway passively types in directives from the others who are calling out commands. He will type the dialogue options players choose. For example, in the story world of the game within the game, players first arrive at a “massive hole” that we presume is an entrance to a cave system. Shannon suggests several rational methods with which to potentially access the cave. At the same time, Ezra calls out, “Yell into the hole first to see if there are pirates!” (Act III, Scene IV). It is the first in a series of attempts to engage the scene playfully instead of rationally. Next, Xanadu tells the player, “You are inside a building, a storage shed for the national park service. There is a sensible, modern electric lantern nearby” (Act III, Scene IV, emphasis added). Players can choose between Shannon, whose directive is “Get the lantern,” or Ezra, who calls out, “That’s boring. Go back to the forest!” (Act III, Scene IV). Although the narration clearly frames Shannon’s option as the practical one, Ezra offers disruptive alternatives, which repeatedly result in dead ends. When Conway types “Enter forest,” Xanadu returns, “That’s not something you can enter” (Act III, Scene IV). Ezra’s impulsivity and low boredom threshold not only reflect his juvenile character but also, through the game-within-the-game format, stage the prototypical mix of reward and frustration in classic text adventures.

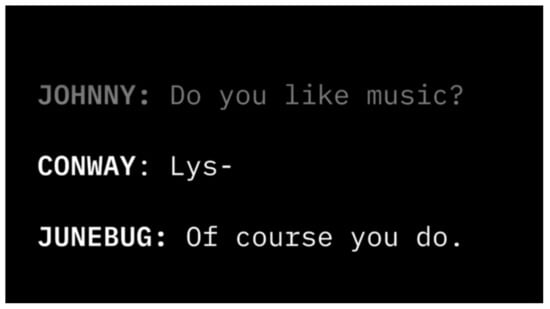

At times, it is of no consequence what dialogue decisions players make—at least in the sense that the selected text is not uttered by anyone. For example, in an effort to attract Conway, Shannon, and Ezra to their gig, Johnny and Junebug ask if they like music. Players can respond as any one of the three characters:

CONWAY: Lysette used to sing in taverns on the weekend. Beautiful stuff.SHANNON: Sometimes I like to leave the radio dialed between stations.EZRA: I don’t like music, but I do like sounds. (Act III, Scene I)

Ezra’s quirky kid response offers a micro-celebration of the weird stuff kids say. Shannon’s reads like a confession of an oddball technophile; she is, after all, an electronics repair worker, and the fact that her name evokes iconic information scientist Claude Shannon, who famously popularized the distinction between signal and noise, makes her response even more resonant. Conway’s reminiscence strikes his typically wistful and resolutely non-confrontational chord. However, none of the options really matter; that is, none of the characters get a turn. Junebug cuts off any response by answering for them with “Of course you do” (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Screenshot of dialogue Act III, Scene I.

In Kentucky Route Zero, we therefore choose one option but experience them all, and conceivably all options play out in a dance of social cognition even when they are not “vocalized” by virtue of selection.

4. Great Permutations

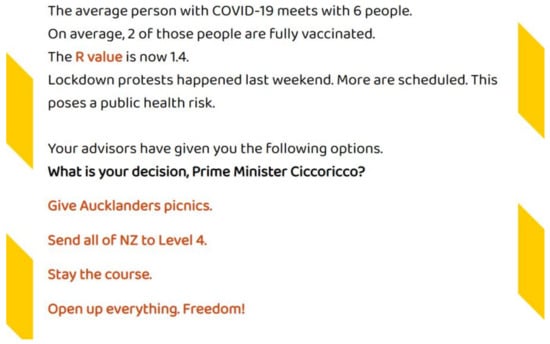

Whereas Kentucky Route Zero encourages varied readings of its dialogue mechanic as social performativity, the playable simulation This is a COVID-19 Announcement (Wills 2021) encourages iterative analysis of a choice-based mechanic about political consequences. Its overall design is oriented more toward imparting systemic understanding of data flows than instilling narrative catharsis. In 2021, during New Zealand’s second major lockdown due to the COVID-19 pandemic, high school science teacher Peter Wills created a short text-based game using the open-source digital authoring platform Twine. The narrative positions you as NZ’s Prime Minister and, using statistical modelling available at the time on projected case numbers, hospitalizations, and deaths, it leaves you in charge of the nation, as well as the government’s daily 1pm news briefing.

It begins with a disclaimer: “Please note that this is a work of fiction. Any similarity to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events, is purely coincidental. You are not the real Prime Minister. Unless you are, in which case, please ignore the last two sentences. Let the country know who is in charge” (Wills 2021). Then it calls for a single configurative act: the final sentence links to a text box that asks for our name, after which point we are addressed with “Prime Minister” preceding whatever name we have provided. From there, after a briefing from the nation’s Director-General of Health, an explorative mode predominates as readers choose from cycles of four options, which present a range of political perspectives (see Figure 2). Each choice we make advances the narrative by one week.

Figure 2.

Screenshot of the initial set of options for the player-character Prime Minister.

This is a COVID-19 Announcement gained national media attention—the first (and conceivably last) time a Twine game would make the headlines in New Zealand (see Jay 2021). Self-described as “a work of fiction,” the game nonetheless employs the names of actual NZ government and celebrity figures in a kind of political drama unfolding in real-time. The game was, in fact, created and released after a particularly bad week of reported case numbers while the country was in a lockdown. Its conclusion is set at the fictional Prime Minister’s family Christmas lunch, where your family members come clean about what they each think of your policies. Launched in early October of 2021, tens of thousands of Kiwis were playing toward a fictional December 2021 as they neared the actual one. Its uptake reflects the Twine community’s knack for timely engagement with critical socio-political moments.

The game’s modeling of probabilistic systems is inspired by a paper published by scientists Nicholas Steyn, Michael Plank, and Shaun Hendy, who became household names for their statistical work in support of NZ’s on-the-fly political policymaking. The light-hearted humor of the narrative resonated with readers, and it compels us to think not only of complex data flows but also the affective flows among the human actors involved (we witness a tipping in societal entropy when the South Island secedes). This is a story about how one human actor, placed in this predicament, invariably fails to make the right or righteous choice. For the Prime Minister, it is always a matter of damage control at best.

Conventional narrative experience, however, does not animate the work as a whole. I found myself playing not for an overall story to find out what happens, but rather for an understanding of the system’s behavior. I cycled through a number of play styles to see what the numbers would tell me in turn. More specifically, I played in what we might call an “official” way that mirrored the actual response of the government, in a “whimsical” way that selected whatever struck me as the most humorous option, and in a “reckless” way that took as much of a hands-off public health response as possible. Overall, our ludic experience of This is a COVID-19 Announcement reveals the two competing goals that inhere for the simulation and the nation’s leader: (1) keep case numbers and deaths down as much as you can (and vaccination numbers up) and (2) keep your job. Ultimately, we need the numbers to communicate an inverse relation between personal happiness and collective safety. We might invoke the completionist ethic from game studies to describe iterative attempts toward mastery, but calling Wills’ creation a game is problematic given the lack of any winning outcome and the fact that actually playing all the possible permutations is mathematically but not practically possible. Or we might entertain a sense of hacktivism in reverse engineering system design, though Twine’s open-source economy already makes such moves possible by way of access to its authoring maps and code.

Ultimately, such playable simulations clearly articulate a different kind of pleasure—one that remains a textual pleasure but is befitting of what theorist of digitally interactive narratives Noam Knoller describes as “userly texts.” Such an experience, for Knoller, “affords repetition and replay, and interpretation, foregrounding playing not for the plot but for higher order systemic understanding of the complex interrelations between different userly performances and their variable outcomes” (Knoller 2019, p. 111). Knoller offers a welcome update for outmoded psychoanalytic notions of narrative desire, such as Brooks’ (1984) alignment of narrative metonymy with Eros (the pleasure principle) and narrative metaphor with Thanatos (the death drive), all in the service of what he calls “full predication” of narrative meaning. Theorists of digital textuality are also well practiced in articulating forms of “userly” pleasure. In his 1995 Of Two Minds: Hypertext Pedagogy and Poetics, Michael Joyce likened the embodied experience of reading hypertext to proprioception—an exploration of our sense of ourselves in space. Moulthrop proposed a model of “itinerant desire” in 1997, writing:

… hypertextual discourse solicits iteration and involvement. While this is certainly a property of all narrative fiction, one can argue that hypertextual writing seduces narrative over or away from a certain Line, thus into a space where the sanctioned repetitions of conventional narrative explode or expand, no longer at the command of logos or form, but driven instead by nomos or itinerant desire.(Moulthrop 1997, p. 273)

Also in 1997, Aarseth published his landmark Cybertext; its focus on “user functions” is foundational for Knoller’s or any subsequent theory of interactive, participatory texts, and its engagement with cybernetic discourse and feedback loops in particular has opened new lines of inquiry into play with complex systems. Despite the typological ends of cybertext theory, moreover, Aarseth considered expanding the notion of narrative desire rather than abandoning it: “The tensions at work in a cybertext, while not incompatible with those of narrative desire, are also something more: a struggle not merely for interpretative insight but also for narrative control (Aarseth 1997, p. 4). Nonetheless, nearly three decades on, it is probably worth revisiting the format of his index entry for “Desire, narrative vs. ergodic,” to question whether the strict opposition still holds, or ever held, in practice (Aarseth 1997, p. 198, emphasis added).

Playable simulations, such as This is a COVID-19 Announcement, animate the iterative seductions of complex systems. The higher-order systemic understanding we glean is not necessarily narrative-driven, nor does it guarantee “full predication” or closure. At the same time, any such critical gesture amounts to more than a media-specific update, and more than mere indulgence in the joy of (electronic) text. Indeed, Knoller’s description underscores a kind of replay value for interpretation itself. We may ultimately find that we “reassert the regime of interpretation,”14 but that might not be such a bad thing—that is, perhaps it is not the kind of regime that needs changing. Both too much and too little theory are dangerous in different ways, but when we have too much, at least self-awareness gives us a better chance to wittingly retreat from abstraction and reenter the realm of action. Given the increasing need to communicate (hyper)complex global systems to the wider populace (Knoller 2019, p. 103)—from political to environmental domains—the task of reading simulations critically and reading what we might call “critical simulations” in turn, takes on added urgency. It is possible to suggest that playable simulations are now displacing traditional representational modes—such as the encyclopedic novel—for narrating complexity.15 We arguably offload the complexity of discourse onto that of choice-making and structural permutation. Or we shift the locus of meaning from agent-centric entities (character-subjects) to complex assemblages. But rather than a case of supersession, it is more likely that cultivating a synthesis of varied sense-making strategies will prove vital in maintaining literary and narrative theory’s service to today’s readers.

5. Conclusions

In a broad sense, the convergence of electronic literature and games over the last two decades grew out of a shift away from efforts to legitimize and individuate respective fields, disciplines, and communities, and toward a focus on shared origins and family connections. Strategic and self-conscious conference keynotes from the Electronic Literature Organization have provided some insight into the field’s developmental trajectory. A new shared focus might be the implications of generative AI for the critical methods we apply across electronic literature and games. Whether it is in its adolescence, its prime, or its golden years, electronic literature and narrative games can now lay claim to a tradition of algorithmic creativity—from parser-based cycles of textual input and output in Interactive Fiction to the guard fields that structured the reading experience of early hypertext fiction in the 1990s, and on to experiments with generative AI for narrative, poetry, and game design in the contemporary moment.

Moreover, the academic orientation of electronic literature per se has long served as an asset in negotiating the human/machinic divide. A requisite addition to any discussion of the field’s transformative phases, then, might be an ongoing process of post-humanization in response to the current surge of generative AI. On the one hand, that entails reckoning with fears of the dehumanizing implications of AI applications (from the creative front to the job front). On the other hand, it presents an opportunity to rearticulate what humanity is and what it means to express it through art and culture.16 ELO’s ongoing negotiation of the “literary” might take on renewed purpose and urgency in that AI calls into question ideas of style, voice, and identity—all things that have traditionally taken up residence in the notion of human subjectivity. Through narrative and play, creative works like Kentucky Route Zero and This is a COVID-19 Announcement will continue to encourage reflection on our common humanity, our political reality, and the choices we make in the face of it. As case studies, both point-and-click action games and playable simulations in Twine represent already cross-bred forms that fall somewhere in the middle of a literary–ludic spectrum. The digital literary diversity they represent points to a healthy ecology of creative media. If such examples also signal a convergence of creative cultures and communities, then that does not diminish the distinctive experiential frameworks we derive from storytelling and gameplay.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

New data was not generated for this article.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the special issue editor for his helpful comments on this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The phrase comes from Shelley Jackson’s now classic hypertext fiction Patchwork Girl (Jackson 1995), in a passage mediating on the experience of digital textuality reflexively titled “this writing.” |

| 2 | For the origins of psychologizing birth order, see (Adler 1927). |

| 3 | I also do not wish to reduce or equate experiential frameworks to narrative experience (see (Caracciolo 2014) for a comprehensive treatment of this topic); the emphasis on experientiality as an analytical framework in game studies by scholars such as Pearce (2004) and Salen and Zimmerman (2004) attests to the wide application of “experientiality.” |

| 4 | Electronic (or digital) literature makes creative use of computational media for aesthetic ends and typically involves some element of textual interactivity or system responsivity. |

| 5 | I acknowledge the narrative-centric approach of my discussion in light of the present collection’s focus on narrative games, and recognize the ELO’s rich engagement with poetry and poetic traditions. |

| 6 | Many of the keynote addresses cited for this article are not publicly available, and have been sourced through online conference archives requiring ELO membership. I have also attended many of the original keynote lectures directly and relied on personal notes in my discussion. For keynote addresses that have been subsequently published, I have cited the published source in the References list while referring to it as an ELO keynote in my discussion. |

| 7 | See Ensslin’s (2019) ELO keynote address for a historical discussion of second wave digital literary criticism (a published version of the address is available here: https://electronicbookreview.com/publications/these-waves-writing-new-bodies-for-applied-e-literature-studies/, accessed on 13 December 2025). |

| 8 | See John Barth’s trio of essays: “The Literature of Exhaustion” (Barth [1967] 1982a), “The Literature of Replenishment” (Barth 1982b), and “The State of the Art” (Barth 1996). |

| 9 | The citation is to her 2015 paper published from the keynote. |

| 10 | These are all punctual landmarks for the sake of historicizing. Of course scholars taught and studied games critically before the 21st millennium, and the formal launch of Game Studies journal was not an immaculate conception of the field. |

| 11 | The panel, titled “Prototyping Resistance: Wargame Narrative and Inclusive Feminist Discourse,” included Jon Saklofske, Acadia University Anastasia Salter, University of Central Florida Liz Losh, College of William and Mary Diane Jakacki, Bucknell University Stephanie Boluk, UC Davis. |

| 12 | The class was offered from 2006 at the University of California Santa Barbara at undergraduate and graduate levels and ran for over a decade. |

| 13 | See, for instance, these game site reviews at Haywire Magazine (https://haywiremag.com/features/pulling-strings/, accessed on 13 December 2025), Games Radar (https://www.gamesradar.com/the-making-of-kentucky-route-zero/, accessed on 13 December 2025), and Game Developer (https://www.gamedeveloper.com/design/kentucky-route-zero-and-play-as-theatrical-performance, accessed on 13 December 2025). |

| 14 | See Moulthrop’s discussion of Janet Murray’s notion of “electronic closure,” which he explains as “the moment at which the reader of an interactive text understands the rationale of its design and likely limits of its productive capacity.” Electronic closure, which Murray finds much less fulfilling than plot-driven pleasures, arguably “reasserts the regime of interpretation” in that, in her view, “configuration serves interpretation” (Moulthrop 2004). |

| 15 | The question of representing narrative complexity has attracted much attention across disciplines, from philosophy of mind, cognitive science, and evolutionary theory to media and film studies. For a narrative-theoretical collection that aims to gather these lines of inquiry, see Grishakova and Poulaki’s (2019) Narrative Complexity: Cognition, Embodiment, Evolution; for a full study specific to narrating complexity in interactive digital narratives, see Hartmut Koenitz’ Understanding Interactive Digital Narrative: Immersive Expressions for a Complex Time (Koenitz 2023). |

| 16 | In 2021, one ELO keynote tracked the limitations and the bias of creative AI, with Lai-Tze Fan’s “Unseen Hands: On the Gendered Design of Virtual Assistants and the Limits of Creative AI” (Fan 2021); another explored AI’s potential for creative communitizing and prosocial change with Archana Prasad’s “RadBots: AI Augmented Writing towards Radical Video Bots” (Prasad 2021). |

References

- Aarseth, Espen. 1997. Cybertext: Perspectives on Ergodic Literature. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Aarseth, Espen. 2001. Computer Game Studies, Year One. Game Studies 1: 1. Available online: https://gamestudies.org/0101/editorial.html (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- Adler, Alfred. 1927. Understanding Human Nature. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Aylett, Ruth. 2000. Emergent Narrative, Social Immersion and ‘Storification’. Paper presented at the Narrative and Learning Environments Conference NILE00 (2000), Edinburgh, UK, August 6–9. [Google Scholar]

- Barth, John. 1982a. The Literature of Exhaustion. Special Bound Edition. Northridge: Lord John Press. First published 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Barth, John. 1982b. The Literature of Replenishment. Special Bound Edition. Northridge: Lord John Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barth, John. 1996. The State of the Art. The Wilson Quarterly 20: 36–46. [Google Scholar]

- Berens, K. I., J. T. Murray, L. Skains, R. Torres, and M. Zamora, eds. 2022. Electronic Literature Collection, Volume 4. Orlando: Electronic Literature Organization. Available online: https://collection.eliterature.org/4/ (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- Block, Friedrich. 2017. Keynote Address for the 2017 Electronic Literature Organization (ELO) Conference, Porto, Portugal. Available online: https://eliterature.org/conference.eliterature.org/archive/2017/conference.html (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- Brooks, Peter. 1984. Reading for the Plot: Design and Intention in Narrative. New York: Vintage Books. [Google Scholar]

- Caracciolo, Marco. 2014. The Experientiality of Narrative: An Enactivist Approach. Berlin: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Cardboard Computer. 2013–2020. Kentucky Route Zero. West Hollywood: Anapurna Interactive. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Edmond. 2024. Keynote Address for the 2024 Electronic Literature Organization (ELO) Conference, Orlando, Florida (Online). Available online: https://eliterature.org/conference.eliterature.org/ (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- Chess, Shira. 2020. Keynote Address for the 2020 Electronic Literature Organization (ELO) Conference, Orlando, Florida (Online). Available online: https://eliterature.org/2020/ (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- Ciccoricco, David. 2007. Play, Memory: Shadow of the Colossus and Cognitive Workouts. Dichtung-Digital 37. Available online: https://mediarep.org/entities/article/25425d54-4c19-46fb-a945-5728b1b88527 (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- Coover, Robert. 2002. Keynote Address for the 2002 Electronic Literature Organization (ELO) Symposium, Los Angeles, CA, USA. Available online: https://eliterature.org/state/home.shtml (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- Dutton, Denis. 2009. The Art Instinct: Beauty, Pleasure, and Human Evolution. New York: Bloomsbury Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ensslin, Astrid. 2014. Literary Gaming. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ensslin, Astrid. 2019. Keynote Address for the 2019 Electronic Literature Organization (ELO) Symposium, Cork, Ireland. Available online: https://eliterature.org/2019/ (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- Eskelinen, Markku. 2001. The Gaming Situation. Game Studies 1: 1. Available online: https://www.gamestudies.org/0101/eskelinen/ (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- Fan, Lai-Tze. 2021. Keynote Address for the 2021 Electronic Literature Organization (ELO) Conference, Orlando, Bergen, Norway and Aarhus, Denmark (Online). Available online: https://eliterature.org/2020/11/cfp-elo-2021-conference-and-festival-platform-post-pandemic/ (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- Grishakova, Marina, and Maria Poulaki, eds. 2019. Narrative Complexity: Cognition, Embodiment, Evolution. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, Vi, and Nicky Case. 2014. Parable of the Polygons. Available online: https://ncase.me/polygons/ (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- Hayles, N. Katherine. 2002. Keynote Address for the 2002 Electronic Literature Organization (ELO) Symposium, Los Angeles. Available online: https://eliterature.org/state/home.shtml (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- Inkle. 2014. 80 Days. Cambridge: Inkle. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, Shelley. 1995. Patchwork Girl. Watertown, MA: Eastgate Systems. [Google Scholar]

- Jay, Ellie. 2021. Game Puts Players in Charge of COVID-19 Response. Radio New Zealand. October 12. Available online: https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/national/453357/game-puts-players-in-charge-of-covid-19-response (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- Joyce, Michael. 1995. Of Two Minds: Hypertext Pedagogy and Poetics. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Joyce, Michael. 2000. Othermindedness: The Emergence of Network Culture. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kirschenbaum, Matthew. 2017. Keynote Address for the 2017 Electronic Literature Organization (ELO) Conference, Porto, Portugal. Available online: https://eliterature.org/conference.eliterature.org/archive/2017/conference.html (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- Knoller, Noam. 2019. Complexity and the Userly Text. In Narrative Complexity: Cognition, Embodiment, Evolution. Edited by Marina Grishakova and Maria Poulaki. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, pp. 98–120. [Google Scholar]

- Koenitz, Hartmut. 2023. Understanding Interactive Digital Narrative: Immersive Expressions for a Complex Time. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Alan. 2017. Teaching ‘Literature+’: Digital Humanities Hybrid Courses in the Era of MOOCs. In Teaching Literature: Text and Dialogue in the English Classroom. Edited by Ben Knights. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 133–53. [Google Scholar]

- Louchart, Sandy, and Ruth Aylett. 2003. Solving the Narrative Paradox in VEs—Lessons from RPGs. In Intelligent Virtual Agents. IVA 2003. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Edited by Thomas Rist, Ruth S. Aylett, Daniel Ballin and Jeff Rickel. Berlin: Springer, vol. 2792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyotard, Jean-François. 1984. The Postmodern Condition. Translated by Geoffrey Bennington, and Brian Massumi. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. First published 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Motte, Warren. 1995. Playtexts: Ludics in Contemporary Literature. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. [Google Scholar]

- Moulthrop, Stuart. 1997. No War Machine. In Reading Matters: Narrative in the New Ecology of Media. Edited by Joseph Tabbi and Michael Wutz. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, pp. 269–92. [Google Scholar]

- Moulthrop, Stuart. 2004. From Work to Play. Electronic Book Review, May 20. Available online: https://electronicbookreview.com/publications/from-work-to-play/ (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- Moulthrop, Stuart. 2020. Keynote Address for the 2020 Electronic Literature Organization (ELO) Conference, Orlando, Florida (Online). Available online: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/elo2020/ (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- Murray, Janet H. 1997. Hamlet on the Holodeck: The Future of Narrative in Cyberspace. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, Celia. 2004. Toward a Game Theory of Game. Electronic Book Review, July 8. Available online: https://electronicbookreview.com/publications/towards-a-game-theory-of-game/ (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- Prasad, Archana. 2021. Keynote Address for the 2021 Electronic Literature Organization (ELO) Conference, Bergen, Norway and Aarhus, Denmark (Online). Available online: https://eliterature.org/2020/11/cfp-elo-2021-conference-and-festival-platform-post-pandemic/ (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- Quinn, Zoë. 2013. Depression Quest. The Quinnspiracy. Available online: https://store.steampowered.com/app/270170/Depression_Quest/ (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- Ryan, Marie-Laure. 2018. Narrative in Virtual Reality? Anatomy of a Dream Reborn. Facta Ficta Journal of Narrative, Theory & Media 2: 91–110. [Google Scholar]

- Salen, Katie, and Eric Zimmerman. 2004. Rules of Play: Game Design Fundamentals. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sony Computer Entertainment America. 2005. God of War. San Mateo: Sony Computer Entertainment. [Google Scholar]

- Szilak, Illya. 2015. Towards Minor Literary Forms: Digital Literature and the Art of Failure. Electronic Book Review, August 2. Available online: https://electronicbookreview.com/publications/towards-minor-literary-forms-digital-literature-and-the-art-of-failure/ (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- Ueda, Fumito. 2005. Shadow of the Colossus. San Mateo: Sony Computer Entertainment. [Google Scholar]

- Walton, Kendall L. 1990. Mimesis as Make-Believe: On the Foundation of the Representational Arts. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wardrip-Fruin, Noah. 2020. Keynote Address for the 2020 Electronic Literature Organization (ELO) Conference, Orlando, Florida (Online). Available online: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/elo2020/ (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- Wills, Peter. 2021. This Is A COVID-19 Announcement. Available online: https://kiaoramrwills.com/COVID-19.html (accessed on 13 December 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.