Abstract

This article explores the concept of textuality as embedded within contemporary architecture, understood as the capacity of buildings to generate meanings, narratives, and interpretations that transcend their physical and functional dimensions. An interdisciplinary approach is adopted, integrating architectural theory, semiotics, hermeneutics, and cultural studies, positioning architecture as a form of symbolic production deeply intertwined with current social and technological contexts. The primary aim is to demonstrate how certain paradigmatic buildings operate as open texts that engage in dialogue with their users, urban surroundings, and cultural frameworks. The methodology combines theoretical analysis with an in-depth study of three emblematic cases: the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, the Centre Pompidou in Paris, and the Seattle Public Library. The findings reveal that these buildings articulate multiple layers of meaning, fostering rich and participatory interpretive experiences that influence both the perception and construction of public space. The study concludes that contemporary architecture functions as a narrative and symbolic device that actively contributes to the shaping of collective imaginaries. The article also identifies the study’s limitations and proposes future research directions concerning architectural textuality within the context of emerging digital technologies.

1. Introduction

Textuality has traditionally been understood as a property intrinsic to written language and verbal discourse, with the text conceived as a coherent unit of language that is read, interpreted, and analyzed, that is, one that must be materially instantiated (Oliveira et al. 2025).

Moreover, the study of texts has been primarily addressed within disciplines such as literature, linguistics, the philosophy of language, and even sociology (van Dijk 1983). This classical conception focuses on the semantic and syntactic dimensions of language, where the text consists of a linear sequence of linguistic signs that produce meaning through grammatical rules and cultural conventions.

However, since the mid-twentieth century, the humanities have undergone a profound transformation in their understanding of what may be considered a text and how meaning is generated within complex cultural contexts (Borges 2021). The development of semiotics as a discipline, founded by Ferdinand de Saussure (1959) and Charles Sanders Peirce (1932), alongside the rise of poststructuralist literary theory and the philosophy of language, expanded the notion of text to encompass broader semiotic systems, in which any system of signs—not exclusively linguistic—can be analyzed in terms of meaning production (García Molina 2020). Notably, Roland Barthes in 1977, with his proposition of the “death of the author” (Barthes 1986), initiated the opening of the text to multiple interpretations, transforming the act of reading into an active, polyphonic, and plural process (Higgins 2025). Similarly, Julia Kristeva in 1980 developed the concept of intertextuality, demonstrating that every text is interwoven with other texts and cultural discourses, emphasizing the relational and dynamic nature of meaning (Iqbal and Rizwan Malik 2025). According to Kristeva, every text is a mosaic of quotations in which multiple prior texts intersect and are transformed. This implies that meaning is not fixed, but contingent upon the cultural contexts from which it is interpreted. Consequently, the concept of text expands beyond the written word to encompass oral, visual, or bodily practices, depending on the conventions of each culture.

These theoretical developments enabled the conception of textuality as a much broader phenomenon—one that encompasses not only written or spoken language but also visual, spatial, material, performative, and multisensory manifestations (Eco 1989). This expansion of the concept of text entails acknowledging that meaning can be generated not only through verbal language but also through broader semiotic systems such as the moving body, gesture, spatial arrangement, or the materiality of objects, all of which operate within diverse cultural contexts. Consequently, a text may be a visual artwork, an image, a space, a gesture, or a combination of multiple semiotic codes that produce meaning through their interrelation and contextual embeddedness (Gambier and Lautenbacher 2024).

Within this expanded field of meaning, architecture can be reconsidered as a paradigmatic domain of expanded textuality. Traditionally, architectural studies have oscillated between formal, functional, and technical analyses, focusing on constructive, utilitarian, stylistic, or historical aspects, yet often without sufficiently addressing the symbolic and communicative dimensions of buildings and spaces (Durán 1926).

However, architecture is simultaneously a technical practice, an art form, and a mode of cultural communication (Brykova et al. 2021). Built environments and architectural spaces do not merely respond to functional needs; they also inscribe, within their form and material values, ideologies, collective memories, and social narratives (Lefebvre 1991). From this perspective, architecture can be interpreted as a complex system of signs and discourses—that is, as a text. This idea, initially explored by authors such as Umberto Eco (1979), Charles Jencks (2002), and Anthony Vidler (1992), suggests that architectural reading must consider not only the physical form but also the cultural and symbolic codes that the building articulates, as well as the sensory and social experience it generates among its users.

The notion of expanded textuality in architecture thus implies that a building is not a static object but rather a dynamic phenomenon in constant dialogue with its social, cultural, and spatial context—and, consequently, with the user. In this sense, architecture articulates meaning through multiple layers: materiality, form, spatial arrangement, perceptual experience, and cultural symbolism. These layers constitute a polysemic text that opens up multiple interpretive pathways and demands an interdisciplinary reading for its full comprehension (Zumthor 2020). For this reason, it is essential to incorporate the phenomenological philosophy of spatial experience, which emphasizes the importance of the multisensory and embodied perception of architectural space (Ji Yi and Heidari Matin 2025). Architecture is not merely visually contemplated—it is experienced through touch, sound, temperature, and movement, dimensions that enrich and complicate its textuality (Böhme 2018). In this way, textuality is expanded to include lived and embodied experience, transcending mere visual or intellectual reading.

Moreover, architectural space is socially produced and embedded within relations of power, identity, and culture, as Henri Lefebvre argues (Lefebvre 1991). This implies that architectural textuality is intertwined with social and political processes, and that the building can act as an active agent in the construction of collective memory, identity representations, and hegemonic or counter-hegemonic discourses (Zukin 1996). Cultural globalization and postmodernity have further produced an urban and architectural landscape marked by plurality, hybridity, and symbolic complexity (Medvegy et al. 2023). In this context, architecture is no longer confined to a homogeneous formal language; rather, it becomes a space of negotiation and articulation of multiple discourses, historical references, identities, and cultural practices. Textualized architecture opens itself to diversity and multiplicity of meaning, functioning as an open text (Eco 1989) in the sense that its meaning is polysemic and continuously constructed by users and spectators.

In this regard, iconic buildings constructed in the contemporary era—such as the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, the Centre Pompidou, and the Seattle Public Library—can be analyzed from this perspective to reveal how architecture produces meaning through the interaction of form, material, technology, and experience. These buildings not only fulfil utilitarian functions but also act as cultural agents that actively participate in the construction of identity narratives and in the shaping of social space (Jencks 2002).

For example, the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao has been studied as a global icon that articulates a discourse of urban and cultural regeneration, integrating organic forms that engage in dialogue with both the industrial and natural context, and generating a multisensory experience that transcends mere visual contemplation (Lorente 2023). In the case of the Centre Pompidou, the exposure of structural and functional elements translates into an architectural text that symbolizes political transparency and cultural democratization (Proto 2006). Finally, the Seattle Public Library is a paradigmatic example of expanded textuality, articulating the fragmentation and complexity of contemporary knowledge through an architecture that is both read and experienced as a multifaceted and interactive text (Mattern 2016).

This article therefore argues that expanded textuality is a key concept for understanding contemporary architecture as a multidimensional phenomenon that integrates form, materiality, experience, and cultural discourse. This interdisciplinary perspective connects literary theory, semiotics, and the philosophy of experience to offer a robust and relevant analytical framework for the study of architecture in the twenty-first century.

The central aim of this work is to develop this interdisciplinary theoretical framework and apply it to the critical analysis of the three aforementioned paradigmatic cases of contemporary architecture, demonstrating how architectural textuality unfolds across multiple dimensions and how this textuality contributes to contemporary cultural production.

This analysis also seeks to reflect on the social, cultural, and political implications of expanded textuality in architecture, highlighting the active role that buildings and constructed spaces play in shaping identities, memories, and urban discourses, as well as in the sensory and social experience of their users.

In sum, this research is situated at the intersection of literary theory, semiotics, phenomenological philosophy, and architectural criticism, proposing an innovative approach to understanding contemporary architecture as a complex and dynamic textual system.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Semiotics and Architecture

Semiotics, as the science of signs, is fundamental for understanding how architecture produces meaning. Ferdinand de Saussure (1959) defined the sign as the inseparable combination of a signifier—that is, the perceptible form—and a signified, the concept itself (de Saussure 1959). Charles Sanders Peirce (1932) expanded this definition by introducing the idea that the sign can operate on different levels as an icon, index, or symbol, depending on the relationship between the sign and its referent (Peirce 1932).

In architecture, this semiotic theory has been applied to analyze how formal elements—volume, shape, materials, colours—function as signs that communicate messages and cultural values (Unwin 2003). For example, the choice to use stone in a building can symbolize solidity and tradition—especially in Western cultural contexts, where stone has historically been the predominant material in emblematic and monumental constructions—and is thus associated with permanence and cultural heritage (Barišić et al. 2019). Conversely, glass communicates transparency and modernity, a meaning reinforced in contemporary societies where technology and spatial openness are central values, and where glass symbolizes lightness, visual accessibility, and a break from the heaviness and enclosure of the past (Abdulahaad et al. 2023). Moving a step further, architectural semiotics has also explored how spaces are organized as systems of signs. For instance, Christian Norberg-Schulz (1979), drawing from phenomenology, described how the genius loci (Norberg-Schulz 1979), that is, the spirit of place (Carruthers 2008), is articulated through environmental signs perceived by users that give meaning to their spatial experience. Architecture thus becomes an open text that dialogizes with its natural and cultural contexts.

2.2. Expanded Textuality: Beyond the Written Text

Expanded textuality refers to the broadening of the concept of text beyond the written word to include multisensory and multidimensional semiotic systems (Eco 1989). Juhani Pallasmaa (2005) emphasizes that architectural experience is inherently multisensory and embodied, where the senses of touch, hearing, and spatial memory are as important as vision (Pallasmaa 2005). Architecture is thus “read” through the body, and this bodily reading adds new layers of meaning that enrich the architectural text (Behbahani et al. 2022).

Moreover, Zumthor (2020) highlights the importance of “atmospheres” in architecture, understood as sensitive qualities emerging from the interaction between light, materials, sound, and space. These atmospheres are an essential part of the expanded text, as they emotionally affect the user and contribute to the production of meaning (Zumthor 2020).

Furthermore, expanded textuality also considers the active role of the user/reader as a co-creator of meaning (Hayles 2003). This connects the notion with literary reception theory, which emphasizes that the text only fully exists in the act of reading and interpretation (Iser 1995). In architecture, this implies that the building’s meaning is constructed through everyday experience, use, and collective memory, not solely through the architect’s intention nor through purely formal or structuralist readings that typically dominate modern and contemporary architectural analyses (Fraile Narváez 2025).

2.3. Interdisciplinarity: Connections Between Literature, Philosophy, and Architecture

Expanded textuality requires an interdisciplinary perspective that integrates literary theory, philosophy of language, phenomenology, and cultural studies to analyze architecture (Hass 2018).

Literary theory provides tools to understand how texts construct meaning through narrative structures, metaphors, and rhetorical figures (Genette 1980).1 This perspective allows architecture to be seen as a spatial narrative, where the sequence and organization of spaces generate a temporal and experiential reading.

Phenomenology, especially within the tradition of Edmund Husserl and Maurice Merleau-Ponty, offers a profound understanding of the lived and embodied experience of space (Farajpour et al. 2024). This is crucial for analyzing how architectural space is perceived and inhabited, and how this experience generates meaning beyond the merely visual (Fang 2022).

Cultural and social studies, in turn, situate architecture within a political and cultural context, analyzing how buildings reflect and reproduce power relations, collective identities, and historical memories. This is fundamental to understanding architecture as a text in dialogue with society (Harries et al. 1988).

2.4. Experience as Text: The Sensory and Temporal Dimension

An essential dimension of expanded textuality is the user’s experience, which transforms space into a lived and dynamic text (Pallasmaa 2005). Architectural experience unfolds through time and the body, configuring a spatial narrativity that can be analyzed from literary theory.

Various studies have explored how architecture can be read as a performative text, where the journey, in the manner of Le Corbusier’s architectural promenade (Alemán Alonso et al. 2021), and the user’s interaction with the space constitute simultaneous acts of reading and writing. This approach relates to Lefebvre’s (1991) concept of spatial practices, which considers space as socially produced through practice and use (Boneff Gutiérrez et al. 2022).

Here, we propose a conception of the user not as an abstract or idealized entity but as a situated and plural subject actively participating in the production of architectural meaning. In this sense, and particularly within public architecture, the user may be understood as a regular visitor, a reader, a building employee, an occasional tourist, or a citizen who appropriates the space through everyday use. Each of these profiles interprets architecture through different bodily, cultural, social, and historical frameworks. Consequently, this experience is not uniform but shaped by variables such as movement rhythm, personal memory, familiarity, exclusion, or desire. Thus, architectural meaning is configured at the intersection between design and the body navigating it, in a dialogic and mutable process. This approach aligns with the work of Sim (2019), who argues that the diversity of users in public spaces contributes to fostering a greater sense of community.

In other words, movement through space, variations in light and shadow, changes in scale and materiality configure a spatial narrative that can be understood as an expanded, multisensory, and dynamic text (Pallasmaa 2005).

2.5. Architecture as a Political and Social Text

Finally, expanded textuality includes the political and social dimension of architecture. Buildings carry discourses that legitimize or challenge power structures (Lefebvre 1991).

Architecture can function as a hegemonic textuality that reinforces national identities, political ideologies, or economic relations (Harvey 1992). Alternatively, it can be a space of resistance and subversion (Granados Manjarrés 2020), a counter-hegemonic text that questions the established order.

Contemporary examples show how architecture participates in processes of urban branding, producing complex and often contradictory meanings (Gönüllüoğlu and Selçuk 2024). Therefore, the analysis of architectural textuality must be critical and aware of these dynamics.

3. Objectives and Methodology

3.1. Research Objectives

The present study aims primarily to analyze and deepen the concept of expanded textuality in contemporary architecture, understanding built spaces as multisensory, dynamic, and polysemic texts that emerge through interaction with their users and social contexts. It focuses on how forms, materials, sensory experiences, and usage practices converge to generate multiple meanings, acknowledging the interpretative agency of the user and the evolving nature of the architectural text over time.

The specific objectives of this research are as follows:

- To define and delimit the concept of expanded architectural textuality, based on the interaction between form, materiality, and user experience.

- To analyze three paradigmatic cases of contemporary architecture to identify concrete examples of how meanings are produced, highlighting the symbolic function of materials, design, and public use.

- To reflect on the dynamic and contextual nature of architectural textuality, emphasizing the interpretative agency of the user and the temporal evolution of meaning.

- To propose interpretative guidelines that enable understanding architecture not merely as a physical object but as a cultural and communicative phenomenon in constant dialogue with its environment and users.

Thus, this study endeavours to contribute to the field of architectural and cultural theory by providing new tools for the interpretation and design of spaces that recognize the semiotic and experiential complexity inherent in architecture.

3.2. Methodology

The research is structured around a qualitative, interpretative, and multidisciplinary approach that combines theoretical analysis, case studies, and critical observation. This mixed-methods research design is best suited to address complex phenomena such as expanded textuality, where a deep understanding of contextual and experiential meanings is essential (Barrio Fraile and Enrique 2018).

The theoretical analysis is based on a critical review of the literature in the fields of semiotics, literary theory, phenomenology, and cultural studies applied to architecture, as outlined in the previous sections of this research. A detailed study of key concepts such as textuality, intertextuality, sensory experience, spatial atmosphere, and the social production of space is conducted, providing the foundation for conceptualizing the phenomenon under study.

The literature review follows criteria of exhaustiveness and academic rigour, utilizing primary and secondary sources of recognized prestige, including books, peer-reviewed scientific articles, and specialized conference proceedings. Academic databases such as JSTOR, Scopus, and Google Scholar, among others, are used to ensure the quality and currency of references.

Although architectural textuality is presented in the theoretical framework as a broad and multidimensional phenomenon encompassing visual, spatial, performative, and multisensory aspects, this work concretely and rigorously implements this approach throughout the study. Specifically, the detailed analysis of the buildings in this study applies these concepts to examine how materials, forms, spaces, and uses contribute to constructing complex discourses and meanings. The methodology incorporates a hermeneutic reading that considers the interaction between architecture and its users, exploring not only form or function but also the experiences and practices that re-signify the architectural text. Therefore, the theory is not confined to a static conceptual framework but is operationalized through a comparative and contextualized analysis that reveals textuality in action. This approach allows for linking symbolic, cultural, and temporal dimensions with actual perception and practical experience, accounting for the interpretative agency of subjects and the living, dynamic character of the architectural text, as exemplified in the results.

3.2.1. Case Analysis

To materialize theory into practice, several contemporary architectural projects are selected that exemplify different aspects of expanded textuality. The selection of these buildings as case studies follows specific criteria: priority is given to paradigm examples of contemporary architecture with broad scientific and media dissemination, offering typological and spatial diversity among them, and reflecting varied interactions between space, urban context, and the user. Additionally, the cases are chosen to demonstrate how contemporary technological innovation can be interpreted and analyzed through symbolic narratives. Furthermore, the selection emphasizes iconic public cultural spaces, crucial for studying architectural textuality from social and symbolic perspectives. These works not only provide cultural functions but also act as symbolic devices that articulate collective identity, urban narratives, and social and spatial regeneration. Thus, when a cultural building attains public and symbolic stature, its visual and cultural impact becomes more determinant than its functionality (Ye 2019).

These criteria enable an exploration of different dimensions of architectural textuality and its polysemy.

The case analysis includes the following:

- Formal and contextual description of the project.

- Identification of semiotic and narrative elements in the design.

- Evaluation of the proposed sensory and bodily experience.

- Interpretation of the implied political and social discourse.

Primary sources such as plans, models, and photographs are used alongside critical studies and previous analyses to build a comprehensive and multidimensional perspective.

3.2.2. Critical-Interpretative Analysis

The interpretation of data extracted from primary sources is conducted through a critical analysis that considers the multiple dimensions of the architectural text. Hermeneutics is employed as the methodological framework to understand how the various elements and experiences intertwine in the production of meaning (Ahmed 2024).

This analysis also incorporates contemporary critical perspectives that situate architecture within its relationships to power, identity, and social memory. Thus, the aim is to reveal both the manifest intentions of the project and its latent and contradictory readings.

3.3. Limitations and Scope

The study acknowledges certain limitations, such as the inherent subjectivity of qualitative analyses and the limited selection of cases, which are intended to be exemplary rather than exhaustive. Nevertheless, the richness of the sources and methodological rigour enable the attainment of solid and relevant conclusions for the understanding and development of the concept.

The scope focuses on contemporary architecture, understood as works and practices from the late twentieth century to the present, where technological and cultural advances have expanded the possibilities of textuality and spatial experience.

4. Case Analysis: Contained Textuality in Contemporary Architecture

Contemporary architecture has established itself as a domain where material construction transcends mere function to become a complex language—a multidimensional text that can be “read” and interpreted from multiple perspectives. This contained textuality is present in form, structure, materiality, and the relationship with the urban and social context, producing a semiotic fabric that amplifies the meaning of the built space.

This section analyses three paradigmatic cases of contemporary architecture, selected for their formal, conceptual, and contextual relevance, as well as for their capacity to exemplify contained textuality: the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao (designed by Frank Gehry, opening 1997), the Centre Pompidou in Paris (designed by Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers, opening 1977), and the Seattle Public Library (designed by Rem Koolhaas, opening 2004).

The selection of these three buildings is based on the criteria previously outlined in the methodology, as they represent paradigmatic milestones due to the following reasons:

- Formal and conceptual relevance: Each building constitutes an internationally recognized architectural landmark noted for its innovation in form, structure, and architectural language, allowing for the analysis of different approaches to textuality.

- Historical and urban contextualization: All three buildings are located in diverse and significant urban settings, where architecture has played a disruptive or regenerative role, reshaping the relationship between built space and social environment.

- Scientific visibility and dissemination: These case studies have been widely documented in academic, critical, and media discourses, ensuring the possibility of an in-depth, multidimensional analysis grounded in well-established primary and secondary sources.

- Typological representativeness: The selection includes different types of public buildings with diverse functions (museum, cultural centre, library), thus expanding the analytical scope regarding how textuality is manifested across various uses and spatial experiences.

- Technological and symbolic innovation: The buildings incorporate technologies and concepts that redefine the architectural and cultural practices of their respective eras, enabling the study of architecture as a living, polysemic text.

Through a rigorous analysis, the implicit textual dimensions of these buildings are explored, unravelling the semiotic complexity they encompass.

In general terms, the main data of the three selected examples are summarized below (see Table 1):

Table 1.

General data of case studies.

4.1. Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, (Designed by Frank Gehry, Opening 1997)

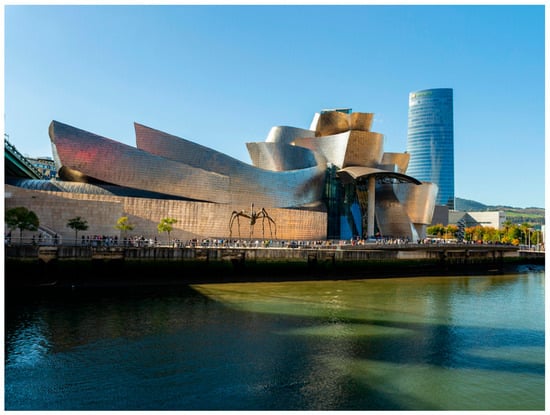

The Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao (see Figure 1) stands as one of the paradigmatic cases of contemporary architecture, characterized by a profound contained textuality.2 From its formal conception to its urban integration and spatial experience, the building emerges as an open text, capable of generating multiple readings and interpretations by both the city’s inhabitants and international visitors.

Figure 1.

Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Frank Gehry. Source: (Vives 2025). Note: Figure free to use. Licence: https://www.pexels.com/es-es/license/. Accessed on 22 June 2025.

Formally, the Guggenheim in Bilbao breaks with the orthogonal compositional logic of traditional architecture through a fragmented and fluid geometry. The interplay of curved volumes clad in titanium panels creates a dynamic, iconic, and socially recognizable surface that responds to light and atmospheric conditions, producing a constantly transforming visual perception. This quality renders the building a “dynamic text,” whose appearance and meaning are continuously rewritten through the sensory experience of the observer (Eco 1989). As Haarich et al. (2009) point out, this formal polysemy allows architecture to be understood not merely as a sculptural object but as an open narrative system, charged with symbolic references that evoke both the fluidity of the Nervión River and the historical transformation of Bilbao (Haarich et al. 2009).

The material employed in the cladding, titanium, is key in constructing this textuality. Beyond its technical properties, titanium functions as a visual sign of temporality and change, acting as a material that, in this sense, embodies allure in contemporary architecture (Muñoz Pérez 2013). Within the cultural context of the late twentieth century, the use of titanium also evokes a post-industrial and technological sensibility, associated with material advancement, formal innovation, and an aesthetic of the unfinished or mutable. Its application in avant-garde architecture, as seen in the Guggenheim Bilbao, embodies a deliberate break from historicist traditions and a symbolic commitment to dynamism, transformation, and openness toward the future. Likewise, its ability to reflect light, the immediate environment and its transformation over time, leading to the development of a patina on its surface (Juaristi 2011), introduce a temporal and sensory dimension into architecture, enriching its character as an open text (Eco 1989). The constant variation in colours and reflections contributes to an ever-changing perception, integrating the building into an ongoing dialogue with its urban and natural context. Actually, Gehry and his team ultimately chose titanium after observing how it completely changed appearance depending on the light and weather conditions—“Sometimes it can be gold, sometimes it can be pink, silver… all different colors” (Gil and Zils 2017)—thus making the cladding a sign of sensory transformation and culturally situated temporality.

The meaning of the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao is not limited solely to its innovative form and materials but is actively constructed through the experience and movement of its visitors. The interior spatial distribution of the museum reinforces this narrative strategy. Gehry rejects the conventional museum model, which is based on linear and hierarchical routes, in favour of a fragmented and fluid structure. The interior spaces are organized non-linearly, inviting visitors to construct their own narrative through active exploration. The multiplicity of possible paths transforms the visit into an act of individual reading, where each visitor selects, orders, and interprets the spatial fragments that compose the whole (Lorente and García 2022). Users engage in an ongoing dialogue with the architectural space, where their perceptions, movements, and emotional responses contribute to the re-signification of the architecture, positioning them as co-authors of the architectural text. This dynamic interaction underscores the building’s open textuality and its capacity to generate multiple interpretations that vary according to context and moment of experience. Within this framework, the museum’s programming is strategically organized into diverse thematic routes that facilitate the exploration of both the exhibited content and the architectural container, thereby fostering plural and enriched readings by visitors (Routes—Guggenheim Museum Bilbao n.d.).

Elements such as the variability of scale among the different interior volumes, the interplay between natural and artificial light, and the shifting arrangement of exhibition spaces reinforce the open and polysemic nature of the experience. Each room, passage, and fold of the building functions as a textual fragment contributing to a broader narrative about the relationship between art, architecture, and city. In this sense, the museum is configured as a complex semiotic system in which function, emotion, and meaning converge.

The urban context in which the Guggenheim is inserted is fundamental to understanding its textual dimension. The building actively participates in rewriting Bilbao’s urban narrative, a city that has transitioned from an industrial past to a present defined by culture and tourism. As Lorente (2025) emphasizes, the museum acts as a public text embodying the city’s economic and social regeneration (Lorente 2025).

Its location alongside the Nervión River, in visual dialogue with the La Salve Bridge and the former industrial infrastructures, reinforces this symbolic function. The architecture not only provides a new cultural space but also constitutes an urban gesture laden with meaning, integrating memories of the past with aspirations for a future grounded in cultural innovation.

Within this framework, the Guggenheim in Bilbao transcends the role of a mere art container to become an active agent in the production of meaning. The building’s fluid morphology, its open spatial organization, its symbolic interaction with the environment, and its evocative materiality transform it into an architectural text that articulates discourses of identity, transformation, and memory. Its impact goes beyond aesthetic or functional value, establishing itself as a global benchmark for the narrative and semiotic potential of contemporary architecture.

Its symbolism has proven culturally and socially recognizable; even the use of metallic material visually alludes to fish scales, an intentional reference to the city’s maritime and industrial past. Gehry has frequently noted that the material evokes fishing nets as well as rusted ship hulls, transforming the building into a floating metaphor embodying Bilbao’s transition from an industrial port to a global cultural hub (Gehry 2004). Its organic form, resembling a stranded ship or a fish in motion, further reinforces this symbolism. The embodied experience of the visitor, circling and penetrating the building as if navigating a marine sculpture, reactivates this symbolism with each movement.

4.2. Centre Pompidou, Paris, (Designed by Renzo Piano, and Richard Rogers, Opening 1977)

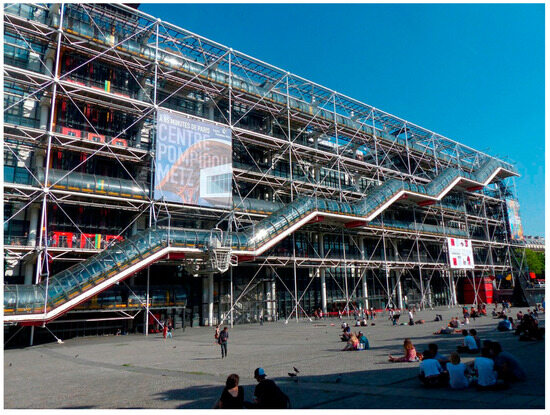

The Centre Pompidou (see Figure 2) has become a hallmark of contemporary architecture by breaking away from traditional architectural conventions and externalizing its structural, technical, and functional systems, transforming these elements into visible signs that form part of the architectural text.

Figure 2.

Centre Pompidou, Paris, Renzo Piano, and Richard Rogers. Source: (Pixabairis 2025). Note: Figure free to use. Licence: https://pixabay.com/es/service/license-summary/. Accessed on 22 June 2025.

Departing from the principles of conventional architecture—where technical elements are usually concealed behind ornate facades or neutral cladding—the architects chose to externalize and make visible the building’s structure and infrastructure (Dal Co 2016). Thus, the very skin of the facade becomes a visual script, that is, an architectural text that makes legible the internal logic of the construction itself. Elements such as steel beams, ventilation ducts, water and electrical pipes, and escalators located on the exterior are transformed into visible signs that constitute a technical, yet symbolic language imbued with deliberate intentions. This inverted structure, by exposing what is normally concealed, symbolizes the openness of knowledge and the decentralization of expertise. More specifically, the zigzagging circulation tubes visible from the exterior function as an architectural sign of the constant flow of bodies and ideas: a symbol of cultural mobility.

This gesture produces an architecture that functions as an exposed text, where the building’s functional anatomy is not only displayed but also invites the viewer to read and understand its internal processes as an integral part of a complete architectural experience (McGraw 1978). The structural and technical transparency establishes a visual language that communicates both the building’s complexity and its commitment to flexibility and adaptability, transforming the visitor’s experience into a continuous act of interpretation.

This conception extends into the interior through an open spatial configuration. The large, open-plan spaces, supported by a modular structure, allow a high degree of versatility in the organization of exhibitions, events, and diverse uses. The Pompidou Centre not only redefines architectural aesthetics through an exhibition-oriented and industrial logic embedded in its very organizational structure, but this is complemented and completed by the actions of the public. Visitors, by choosing how to move through the space, which areas to occupy, how long to stay, and from which perspectives to observe, generate individual and evolving interpretations of the place. This active dimension positions the user at the core of the building’s semiotic framework, where every action—whether conscious or unconscious—contributes to the continual re-signification of the space.

This adaptability makes the building itself a mutable text, open to new writings according to the cultural, technological, and social needs of each era3. In this regard, the architecture of the Pompidou behaves as a postmodern text: open, unstable, and polyphonic, whose legibility emerges through the direct interaction between the body, perception, and cultural environment.

Such spatial flexibility is not merely an operational resource; it also constitutes a constructed metaphor of contemporary society, characterized by fluidity, fragmentation, and constant transformation. The Centre Pompidou reflects in its configuration and operation the multiplicity of discourses, uses, and meanings that shape modern urban culture, acting as a symbolic container of plurality and diversity.

The adjacent public space, the Beaubourg Plaza, extends this textuality outward into the city. Far from being a mere functional setting, the plaza operates as an open urban forum, socially participatory, where the building actively engages in dialogue with its social and urban contexts (Zhang 2023). Through the hosting of cultural events, public demonstrations, and spontaneous gatherings, the plaza becomes an extension of the architectural text, reinforcing the idea of architecture integrated within the social production of space. Thus, the building itself transforms the plaza into a genius loci embedded within the contemporary city and integrates the visitor’s body into a visible urban choreography, emphasizing public access to knowledge as a democratic value.

Finally, the industrialized and modular conception of the Centre anticipates a unique temporal dimension. This approach, derived from industrial assembly logic, enables not only rapid construction and maintenance but also the capacity to modify the building without altering its fundamental structure. The building was designed to be easily updated and transformed, allowing technical and functional modifications and adaptations over time. Thus, far from being a closed, rigid, or definitive architectural object, the Pompidou presents itself as a living text, in constant evolution, capable of expressing and containing shifting cultural, social, and technological discourses. Moreover, from the perspective of temporality, the Centre Pompidou was initially perceived as a symbol of technological innovation and a break with architectural tradition, but over time it has acquired meanings associated with popular culture, civic appropriation of public space, and urban transformation. This mutability constitutes a defining feature of postmodern textuality, where the reader/user becomes an active agent of interpretation, capable of resignifying the architectural text based on individual and collective experiences.

For these reasons, it can be considered one of the most representative paradigms of contained textuality in contemporary architecture.

4.3. Seattle Public Library, (Designed by Rem Koolhaas, Opening 2004)

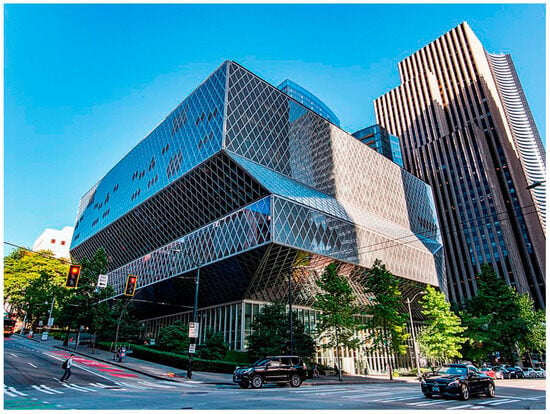

The Seattle Public Library (see Figure 3) emerges from the hybridization of traditional library functions with the demands of a networked society, in which information flows through multiple channels and formats. In this sense, the building is not limited to being a space for book storage but is conceived as a multifunctional ecosystem housing reading areas, auditoriums, social meeting spaces, digital platforms, and zones for experimentation with new technologies (Haddadi-Zambrano 2022).

Figure 3.

Seattle Public Library, Rem Koolhaas. Source: (Ɱ 2025). Note: Figure free to use. Licence: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Seattle_Library_01.jpg. Accessed on 22 June 2025.

This programmatic combination translates into a polyphonic architectural text that reflects the profound transformations of contemporary culture, where the production and circulation of knowledge occur within complex and heterogeneous networks. Koolhaas’s design embodies this condition through an architectural form that breaks with the conventional models of monumental or introverted libraries, favouring instead an open, transparent, and fragmented building.

All these volumes are externally realized through a distinctive skin. Its façade symbolically represents a network, previously mentioned multiple times, both in a literal and figurative sense. The steel and glass structure, shaped as a three-dimensional network, symbolizes digital connectivity, the exchange of information, and institutional transparency. In a society defined by the virtual, the building stands as an icon of open access to knowledge: its lightweight materiality, labyrinthine form, and spiral circulation embody the contemporary modes of information production and consumption. The user’s body navigates the library akin to a spatial hyperlink, embodying an experience of expanded reading.

The spatial language of the library is structured around a set of interrelated prismatic volumes, whose fragmented design generates a heterogeneous spatiality and invites multiple readings. Each volume responds to different uses and types of content, ranging from the main reading hall to spaces dedicated to technology or social interaction. This arrangement creates a spatial polysemy: visitors face an open architectural text capable of offering diverse experiences depending on the path they choose and how they interact with the various environments (Florio and Tagliari 2024). In this sense, spatial fragmentation operates as a language that emphasizes the building’s complexity and enriches its contained textuality.

The integration of advanced technology is an essential aspect of this expanded textuality (Díaz-Guerra et al. 2021). The Seattle Public Library incorporates digital solutions in its operations, from automated systems for collection management to multimedia interfaces and constant connectivity with computer networks. This hybridization between the material and the virtual generates an architectural text that transcends the physical boundaries of the building and connects with a global information universe. Consequently, the user’s spatial experience is expanded and mediated by these digital elements, which add new layers of meaning and redefine the very concept of the library in the digital age. Far from a traditional conception of the building as a neutral container of books, Koolhaas proposes a system of circulation, visibility, and use that transforms the reader into an active interpreter of the space.

Moreover, the library’s architecture promotes the active participation of the user in constructing meaning. Following the idea of the open text, the experience is not limited to passive perception but invites dynamic interpretation (Seamon 2016). The user is key to understanding the building as an architectural text: circulation through its ramps, the free choice of routes, access to open or compartmentalized reading areas, and the appropriation of informal spaces (such as viewpoints or rest areas) transform the experience of the place into an act of active interpretation. It is not merely about accessing the information contained in the books but about participating in a spatial narrative that reflects and questions transformations in knowledge, digital accessibility, and the democratization of learning. The fragmented and vertical arrangement of the programmes, far from being a simple functional device, introduces multiple layers of reading that the user reorganizes with each journey, thereby contributing to an architecture that does not communicate fixed meanings but is constituted through everyday inhabitation. Therefore, the building does not communicate unidirectionally but enables reading conditions that are always open and contextualized, reinforcing its semiotic and performative dimension. The user acts as a co-author of the architectural text by interacting with the spaces, the contents, and the available technologies, thus generating a personalized and mutable experience.

Ultimately, the Seattle Public Library exemplifies architecture that incorporates the cultural, technological, and social complexity of contemporary society, constructing a polyphonic spatial text in constant evolution, an interwoven network, which fosters new forms of interaction among the building, its users, and the surrounding environment.

5. Discussion

The analysis of textuality in contemporary architecture, based on the cases of the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, the Pompidou Centre in Paris, and the Seattle Public Library, reveals multiple layers of meaning within the built space. These buildings exemplify how architecture, beyond its materiality, is configured as a system of signs—interpretable and capable of generating narratives that engage both individuals and collectives.

This phenomenon responds to broader transformations in architectural theory and practice. Since the second half of the twentieth century, architecture has transcended functionalist and formalist conceptions, embracing the discursive nature of space. Thus, iconic buildings such as those studied here are not mere technical constructions but rather “texts” that participate in complex cultural, social, and political processes.

In comparative terms, the three selected and analyzed buildings are summarized as textual elements in the following table (see Table 2):

Table 2.

Comparative analysis of textualities.

The following discussion articulates the main interpretative lines arising from this analysis, focusing on three interrelated axes:

- Architecture as an open and polysemic text.

- The interaction between space, context, and user.

- The temporal and evolutionary dimension of architectural textuality.

The analysis of the three selected works reveals a series of common interpretative threads concerning the notion of contained textuality. These buildings are not closed or self-referential objects; rather, they act as open texts, deeply connected to their context, user experience, and temporal evolution.

Firstly, the three cases demonstrate an approach to architecture as an open text. According to Eco (1989), a text of this nature does not convey a single meaning but allows for multiple interpretations.

The Guggenheim Bilbao exemplifies this condition through its fluid volumetry, metallic surfaces that shift with the light, and a non-hierarchical spatial arrangement that generates a plurality of readings: from natural evocations of the Nervión River to narratives of urban transformation and individual aesthetic experiences.

The Pompidou Centre, however, adopts a different strategy: it externalizes its technical and structural systems, making the building’s anatomy visible. This deliberate transparency enables a direct and collective reading of the architecture, integrating functional elements as part of its visual message. Here, what is usually concealed becomes a sign, and the building presents itself as a text legible by all users.

In turn, the Seattle Library radicalizes this openness through the incorporation of principles of hypertextuality. Its formal fragmentation, multiplicity of functions, and integration of digital elements produce an architectural space that reflects the plural and networked nature of contemporary knowledge. Each volume and functional area offer the user distinct spatial experiences, constructing a polyphonic text open to multiple and simultaneous readings.

In all these cases, architecture approaches cultural forms such as postmodern literature or conceptual art, which privilege ambiguity and active participation.

Secondly, it is evident how these buildings establish a meaningful interaction with their urban context and their users. In contrast to the autonomist ideals of the Modern Movement, these works demonstrate a profound embedding within their surroundings and promote participatory experiences. The Guggenheim, conceived as a driver of urban regeneration, articulates a spatial narrative that links the river landscape, the city’s industrial memory, and its contemporary identity. Its presence transforms the city, becoming an urban landmark imbued with deep significance.

The Pompidou Centre extends its textuality into the public space by generating continuity between the building’s interior and the Place Beaubourg. This open space functions as a cultural and social extension of architecture, blurring the boundaries between building and city and fostering spontaneous dynamics of appropriation.

The Seattle Library further emphasizes the participatory dimension. Its design allows users to act as co-authors of the space and its meaning. The integration of digital technologies facilitates personalized pathways and cognitive experiences that expand the traditional function of a library. Thus, it reflects a contemporary vision of knowledge as a collaborative, networked process rather than a mere hierarchical accumulation.

Finally, these buildings exhibit an evolving textuality that transforms over time. The Guggenheim Bilbao introduces this dimension through the perceptual mutability of its titanium surfaces, which change with light and seasons, the gradual patina resulting from the passage of time, and through the construction of cultural meanings that deepen over time. The Pompidou Centre, with its modular structure and programmatic flexibility, is designed to continuously adapt to new uses and narratives. The Seattle Library, fully embedded in global flows of digital information, is a text in constant reconfiguration, in dialogue with technological and cultural changes.

Based on the conducted analysis, three key interpretative guidelines are proposed to approach the architectural textuality of a building from an expanded perspective:

- Symbolic reading of materiality: Analyze how the materials employed not only fulfil constructive or technical functions but also act as cultural signs that evoke values such as innovation, transparency, tradition, monumentality, or temporality in relation to the specific sociocultural context. This involves performing a semiotic analysis of the building’s materials, supported by bibliographic sources that contextualize their cultural meanings. Direct observation and graphic documentation complement this to understand how these materials function as signs within their context.

- Public function and discursive dimension: Consider the intended use of the building (museum, library, cultural centre) as an essential part of its message. The use of public and culturally themed buildings situates the architecture within political, social, and educational discourses, making it a device that conveys ideology, memory, or collective identities. To this end, official documents and related texts should be studied to comprehend the building’s social and political role. Additionally, public use of the space and social practices occurring therein are observed and interpreted through cultural and urban theoretical frameworks.

- Corporeal interaction and semantic mutability: Explore how architectural meaning is co-constructed with the users who traverse, use, and perceive the space. This experiential and performative dimension enables understanding the building as an open text whose meanings evolve over time, across audiences, and through inhabiting practices. Participant observation is proposed to capture users’ experiences and their interaction with the space. Movements and spatial practices, as well as the temporal evolution of interpretations and uses, are analyzed to comprehend the building’s dynamic and open character.

These guidelines constitute a critical reading tool to comprehend architecture as a situated and dynamic language, capable of producing meanings beyond the visual or functional, and deeply rooted in cultural contexts.

Together, these examples define architecture understood as a palimpsest—a multi-layered text wherein each interaction, use, and perception add new layers of meaning. The contained textuality resides not only in formal or visual aspects but also in experiential, social, and temporal dimensions. In this way, architecture becomes an active part of a collective, open, and unfinished interpretive process that engages with contemporary cultural and social transformations

6. Conclusions

The analysis conducted in this study has facilitated a reflection on the contained textuality in contemporary architecture, surpassing the traditional view of the building as a mere physical object by positioning it as a complex system of cultural signification. Architecture not only constructs spaces but also produces discourses, generates multiple interpretations, and maintains dynamic relationships with its social and cultural context. This approach broadens its scope beyond the dichotomy between form and function or technique and art, recognizing it as a symbolic practice capable of communication and dialogue.

The comparative analysis of the proposed examples has evidenced that buildings should be treated as open texts, in which, just as a text depends on the reader, there is no closed message but rather a multiplicity of meanings anchored in the user, context, and historical moment. In these architectural texts, users are active participants who, through their routes and practical experiences, contribute to the continuous and variable generation of meaning. Thus, architectural textuality moves away from the notion of fixed meaning and presents itself as a living process from individual, collective, and even temporal perspectives.

One of the central aspects emerging from this analysis is the polysemy of contemporary architecture. The buildings studied demonstrate how architectural design can foster interpretative ambiguity. This open character turns architecture into a cultural phenomenon that approaches other artistic forms, such as postmodern literature, where ambiguity, receiver participation, and the decentralization of meaning are essential. Consequently, contemporary architecture can be understood as a complex visual language in which each element contributes a system of meanings that is not exhausted by immediate perception but rather invites reflection.

Another fundamental dimension of this architectural textuality is the interaction between the built space, its urban and social context, and the users themselves. Buildings do not exist autonomously but are embedded within urban fabrics and respond to social transformations. This approach represents a shift from traditional architecture. Contemporary architecture thus emerges as a stage where multiple narratives intersect, and where the user is not a passive receiver but an agent who re-signifies space. The relationship between building and user is dialogic, and the meaning of the architectural text is updated through use.

This dialogue also implies a redefinition of the city as a setting. The analyzed buildings not only occupy a physical place but also contribute to transforming collective representations of the urban environment, creating new imaginaries, and shaping the cultural identity of communities. Architecture, as an open text, functions as an instrument of symbolic and social regeneration, capable of articulating discourses that both reflect and shape processes of change. Thus, architectural space can be considered both a product and a producer of culture.

Furthermore, architectural textuality is characterized by its temporal and evolutionary dimension. Far from being fixed or closed texts, the buildings studied in this research constitute palimpsests in which multiple layers of meaning are inscribed over time. Architecture is written and rewritten through interaction with its users, material transformations, and cultural shifts. Surfaces, functions, pathways, and uses change, generating new interpretations that enrich the original text. This capacity to adapt and transform endows architecture with its own vitality and prolonged cultural resonance.

This temporal evolution reveals that textuality is not a static attribute but a dynamic one, dependent on collective memory and everyday practices. Buildings act as containers of historical experiences, symbols in process that can be re-signified at different times and by different actors. From this perspective, architecture can be understood as a cultural process in constant motion, absorbing social and technological transformations to remain relevant and open to new readings.

However, despite the findings of this research, the present study reveals certain limitations. The analysis has focused on iconic buildings designed by renowned architects, widely disseminated in academic and media contexts. Although these are paradigmatic examples for understanding architectural textuality, future research should include more common typologies and less recognizable buildings to explore how textuality operates in everyday contexts. Furthermore, the cultural and hermeneutic approach requires a critical perspective that more thoroughly incorporates the political, economic, and social conditions influencing the production and reception of architecture; given that architectural textuality is deeply inscribed within power dynamics, urban policies, and economic imaginaries. Likewise, emerging digital technologies (hybrid environments, smart cities, augmented reality) are reconfiguring the reading of built space. Investigating how textuality transforms in this new scenario is considered essential for future studies.

Finally, this study reinforces the consideration of architecture as a foremost cultural and symbolic field, beyond its technical, functional, or artistic roles. Buildings do not merely house bodies or promote flows, but they also construct narratives, generate affects, and contribute to shaping urban and social imaginaries. Understanding architecture as text means recognizing its unique capacity to articulate the material and the symbolic, the spatial and the narrative, the visual and the experiential, in a complex textual synthesis. This perspective broadens the comprehension of the role architecture plays in contemporary society.

In a world saturated with fleeting images and ephemeral narratives, architecture continues to offer a space for embodied experience, sustained interpretation, and the collective construction of meaning. The buildings analyzed exemplify how contemporary architecture can continue to generate open, living, and meaningful textualities, inviting citizens to become active readers who participate in the ongoing rewriting of the urban narrative collectively, while also constructing individual stories. Within this capacity lies one of the deepest values of current architecture: its potential to open new ways of reading, understanding, and building the shared world.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data created for the analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Contemporary scholarly perspectives affirm the possibility that buildings possess textual properties, a concept closely related to the notion of architecture parlante coined by Kaufmann (1955). These investigations have led architectural thought to both draw from and contribute to a diverse array of approaches, terminologies, and methodologies originating from the humanities, especially philosophy and literary theory (Topolovská 2022). Hence, literary terms such as those mentioned are applicable from an architectural standpoint. One of the most representative examples of architecture parlante is the project of the Temple of Equality, designed in 1794 by Alexis-François Bonnet for the Sacred Mountain of Paris. A notable aspect of this proposal is the accompanying explanatory text, presented as a narrative in which the author details the ideas the building intends to convey. In this description, Bonnet interprets each symbol and metaphor embedded in the temple: for instance, the figure of Hercules represents the triumphant people, while other elements function as metaphors for Reason or the struggle against Tyranny (Trzeciak 2015). |

| 2 | By “contained and profound textuality” is understood the quality of the building that, while not presenting itself explicitly or literally as a direct message, encloses complex layers of meaning revealed through prolonged observation, bodily experience of the space, and cultural contextualization. |

| 3 | These social needs can be understood as shifts in modes of inhabiting and participating in public culture: ranging from demands for greater inclusion and accessibility (such as the incorporation of resources for people with disabilities or the redesign of spaces to accommodate diverse audiences) to the emergence of new forms of digital and technological interaction (including interactive installations or hybrid physical–digital tours), as well as the use of cultural spaces as platforms for activism, protest, or collective advocacy. The building responds to these changes not merely as a functional container but as a symbolic stage that enables and reflects new forms of citizenship and social agency. |

References

- Abdulahaad, Enas Salim, Vian Abd Al-Baseer M. Hasan, and Zainab Hussein Ra’ouf. 2023. Reconsidering the Transparency of Contemporary Architecture and Sustainability Through Development of Glass Technology. International Journal of Design & Nature and Ecodynamics 18: 1111–19. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, Sirwan R. 2024. Semiotics and Hermeneutics in the Art of Painting and Contemporary Architecture. Erbil Province as an Example. Koya University Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences 7: 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemán Alonso, Edgar Manuel, Fernando N. Winfield Reyes, and Daniel R. Martí Capitanachi. 2021. La Architectural Promenade de Le Corbusier: Hacia una nueva percepción de la arquitectura. e-RUA 13: 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barišić, Slobodan, Vladica Cvetković, Nevena Debljović Ristić, Jelena Ivanović-Šekularac, Dušan Mijović, and Nenad Šekularac. 2019. The Use of Natural Stone as an Authentic Building Material for the Restoration of Historic Buildings in Order to Test Sustainable Refurbishment: Case Study. Sustainability 11: 4009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrio Fraile, Estrella, and Ana María Enrique. 2018. Guía para implementar el método de estudio de caso en proyectos de investigación. In Propuestas de Investigación en Áreas de Vanguardia. Edited by José Borja Arjona Martín and Estrella Martínez Rodrigo. Barcelona: Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, pp. 159–68. [Google Scholar]

- Barthes, Roland. 1986. The Rustle of Language. New York: Hill and Wang. [Google Scholar]

- Behbahani, Homa Irani, Amirmasoud Dabagh, Roshina Shahhoseini, and Vahid Shaliamini. 2022. Analyzing the Characteristics of Cultural Meanings of Architectural Elements in Semiotic Layers. The Culture of Islamic Architecture and Urbanism 7: 209–28. [Google Scholar]

- Boneff Gutiérrez, Erika Ingrid, Diego Orlando La RosaBoggio, Karen Pesantes Aldana, Luis Enrique Tarma Carlos, and Carlos Eduardo Zulueta Cueva. 2022. La materialidad en la arquitectura. Cuadernos del Centro de Estudios en Diseño y Comunicación Ensayos 175: 201–8. [Google Scholar]

- Borges, Rosa. 2021. Prácticas filológicas en la edición de textos del siglo XX: Experiencias de un grupo de investigación. (an) ecdótica 5: 41–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhme, Gernot. 2018. The Aesthetics of Atmospheres (Ambiances, Atmospheres and Sensory Experiences of Spaces). London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Brykova, N., M. Dymchenko, and I. Lokonova. 2021. Architectural form as a subject of cultural communication. Paper presented at IV International Scientific Conference “Construction and Architecture: Theory and Practice of Innovative Development” (CATPID-2021 Part 1), Nalchik, Russia, July 1–5, vol. 281, pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Carruthers, Mary. 2008. The Book of Memory: A Study of Memory in Medieval Culture. London: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dal Co, Francesco. 2016. Centre Pompidou. Renzo Piano, Richard Rogers, and the Makinf of a Modern Monument. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- de Saussure, Ferdinand. 1959. Course in General Linguistics. New York: Phisolophical Library. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Guerra, Belén Butragueño, Javier Francisco Raposo Grau, and María Asunción Salgado de la Rosa. 2021. Polyhedral communication in architecture. Advances in Building Education 5: 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán, Miguel. 1926. El simbolismo en la arquitectura. Notas al margen de un libro. Arquitectura. Revista Mensual—Órgano Oficial de la Sociedad Central de Arquitectos 8: 179–85. [Google Scholar]

- Eco, Umberto. 1979. A Theory of Semiotics. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eco, Umberto. 1989. The Open Work. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, Ying. 2022. Spatial Narrative in Fiction: “Spatialization” of Fiction Narrative. In Spatial Literary Studies in China. Geocriticism and Spatial Literary Studies. Edited by Ying Fang and Tally Robert. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 107–25. [Google Scholar]

- Farajpour, Maryam, Mehrdad Matin, Nayer Tahoori, and Zahra Khodaee. 2024. An overview of phenomenological theories and its impact on the atmosphere of architecture from the perspective of architectural thinkers and philosophers. International Journal of Urban Management and Energy Sustainability 5: 60–76. [Google Scholar]

- Florio, Wilson, and Ana Tagliari. 2024. The Dynamic Labyrinth of Rem Koolhaas. Revisiting Le Corbusier’s Promenade Architecturale. In Contemporary Heritage Lexicon. Springer Tracts in Civil Engineering. Edited by Cristiana Bartolomei, Alfonso Ippolito and Simone Helena Tanoue Vizioli. Cham: Springer, pp. 227–47. [Google Scholar]

- Fraile Narváez, Marcelo Alejandro. 2025. Fenomenología y sentido: Hacia una arquitectura sensible y transformadora. Revista M. Revista de la División de Ingenierías y Arquitectura 20: 22–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambier, Yves, and Olli Philippe Lautenbacher. 2024. Text and context revisited within a multimodal framework. Babel 70: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Molina, Bartolo. 2020. Una mirada crítica a la teoría del signo. Ciencia y Sociedad 45: 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehry, Frank. 2004. Guggenheim Museum Bilbao: Architecture and Design. Bilbao: Guggenheim Museum Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Genette, Gerad. 1980. Narrative Discourse. An Essay in Method. New York: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gil, Iker, and John Zils. 2017. Building the Symbol of a Remarkable Transformation. Mas Context. Available online: https://mascontext.com/issues/bilbao/building-the-symbol-of-a-remarkable-transformation?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 2 August 2025).

- Gönüllüoğlu, Sedat, and Semra Arslan Selçuk. 2024. City branding in the context of architecture, tourism, culture, and cultural identity interaction—Bibliometric analysis of literature. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy 21: 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granados Manjarrés, Maritza. 2020. Crear: Especular y subvertir. Contexto 14: 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haarich, Silke N., Beatriz Plaza, and Manuel Tironi. 2009. Bilbao’s Art Scene and the “Guggenheim effect” Revisited. European Planning Studies 17: 1711–29. [Google Scholar]

- Haddadi-Zambrano, Salvador. 2022. Crono-espacios en la obra de Rem Koolhaas. Capacidad de cambio y transformación de los edificios híbridos. Constelaciones (2340-177X) 10: 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harries, Paul, Alan Lipman, and Stephen Purden. 1988. Meaning in architecture: Post-Modernism, hustling and the big sell. In Environmental Perspectives. Edited by David Canter, Martin Krampen and David Stea. London: Routledge, pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, David. 1992. The Condition of Postmodernity. An Enquiry into Origins of Cultural Change. Cambridge: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Hass, Andrew W. 2018. Poetics of Critique. The Interdisciplinarity of Textuality. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hayles, Nancy Katherine. 2003. Translating Media: Why We Should Rethink Textuality. The Yale Journal of Criticism 16: 263–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, Ian. 2025. Claude Rawson: An Overview and Appreciation, and Other Observations. Interdisciplinary Studies of Literature 9: 5–18. [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal, Shahid, and Muhammad Rizwan Malik. 2025. Intertextual Cartographies of Migration: A Critical Study of Literary, Religious, and Mythological Allusions in Mohsin Hamid’s Exit West. Annual Methodological Archive Research Review 3: 94–99. [Google Scholar]

- Iser, Wolfgang. 1995. Interaction between Text and Reader. In Readers and Reading, de Andrew Bennett. London: Routledge, pp. 106–19. [Google Scholar]

- Jencks, Charles. 2002. The New Paradigm in Architecture. London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ji Yi, Ye, and Negar Heidari Matin. 2025. Perception and experience of multisensory environments among neurodivergent people: Systematic review. Architectural Science Review, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juaristi, Joseba. 2011. La ciudad superficial. El concepto de pátina y su aplicación al medio urbano. Fabrikart 6: 136–59. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann, Emil. 1955. Architecture in the Age of Reason Baroque and Post-Baroque in England, Italy, and France. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, Henri. 1991. The Production of Space. Cambridge: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Lorente, Jesús Pedro. 2023. Reviewing the “Bilbao effect” inside and beyond the Guggenheim: Its coming of age in sprawling cultural landscapes. Curator: The Museum Journal 67: 365–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorente, Jesús Pedro. 2025. Symbol of an era?: The Guggenheim Bilbao as an epitome of new museum tendencies at the turn of the millennium. Museum, Materials and Discussions. Journal of Museum Studies 2: 95–114. [Google Scholar]

- Lorente, Jesús Pedro, and Natalia Juan García. 2022. El efecto Guggenheim, en su 25 aniversario. Espacio Tiempo y Forma. Serie VII, Historia del Arte 10: 249–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ɱ. 2025. «https://commons.wikimedia.org/.» https://commons.wikimedia.org/. Available online: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/2c/Seattle_Library_01.jpg/960px-Seattle_Library_01.jpg?20200117032014 (accessed on 22 June 2025).

- Mattern, Shannon. 2016. Just how public is the Seattle Central Library? Publicity, posturing, and politics in public design. In Take One Building: Interdisciplinary Research Perspectives of the Seattle Central Library. Edited by Ruth Conroy Conroy Dalton and Christoph Hölscher. Oxfordshire: Taylor & Francis, pp. 5–18. [Google Scholar]

- McGraw, Eugene T. 1978. France’s Pompidou Center: A Case for User Evaluation. Journal of Interior Design Education and Research 4: 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medvegy, Gabriella, Chao Ren, and Jinding Yuan. 2023. Applied research on cultural symbols in landscape architectural design. Pollack Periodica 18: 166–69. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz Pérez, Laura. 2013. Aplicaciones constructivas y expresivas del metal en la arquitectura contemporánea: Del ocaso del hierro al imperio del acero. ASRI: Arte y Sociedad. Revista de Investigación 4: 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Norberg-Schulz, Christian. 1979. Genius Loci: Towards a Phenomenology of Architecture. New York: Rizzoli. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, Davi Alves, Hernane Borges de Barros Pereira, and Lêda Maria Braga Tomitch. 2025. Revisão sistemática de definições e caracterizações de texto: Uma proposta de definição operacional. Linguagem em (Dis)curso 25: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallasmaa, Juhani. 2005. The Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses. Oxford: John Wiley & Sons Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Peirce, Charles Sanders. 1932. Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce, Volumes I and II: Principles of Philosophy and Elements of Logic. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pixabairis. 2025. «https://pixabay.com/.» https://pixabay.com/. Available online: https://cdn.pixabay.com/photo/2014/11/13/23/58/center-pompidou-530069_960_720.jpg (accessed on 22 June 2025).

- Proto, Francesco. 2006. The Pompidou Centre: Or the hidden kernel of dematerialisation. The Journal of Architecture 10: 573–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Routes—Guggenheim Museum Bilbao. n.d. Available online: https://www.guggenheim-bilbao.eus/en/routes (accessed on 2 August 2025).

- Seamon, David. 2016. A phenomenological and hermeneutic reading of Rem Koolhaas’s Seattle Central Library: Buildings as lifeworlds and architectural texts. In Take One Building: Interdisciplinary Research Perspectives of the Seattle Central Library. Edited by Ruth Conroy Dalton and Christoph Hölscher. London: Routledge, pp. 83–110. [Google Scholar]

- Sim, David. 2019. Soft City: Building Density for Everyday Life. Washington, DC: Island Press. [Google Scholar]

- Topolovská, Tereza. 2022. Reading buildings: The textual turn of architecture as a parallel to the spatial turn in literary studies. Ars Aeterna 14: 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trzeciak, Kataryna. 2015. The Petrified Utopia: Monumental Propaganda, Architecture Parlante, and the Question about (De)Materialisation of Monuments. Philosophy Study 5: 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Unwin, Simon. 2003. Análisis de la Arquitectura. Barcelona: Gustavo Gili. [Google Scholar]

- van Dijk, Teun A. 1983. La Ciencia del Texto. Un Enfoque Interdisciplinario. Barcelona: Paidós Ibérica. [Google Scholar]

- Vidler, Anthony. 1992. The Architectural Uncanny. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vives, David. 2025. «www.pexels.com.» www.pexels.com. Available online: https://images.pexels.com/photos/10473395/pexels-photo-10473395.jpeg (accessed on 22 June 2025).

- Ye, Xi. 2019. The Pragmatic Role of Iconic Buildings in Promoting Social Engagement: A Case Study of Sage Gateshead Music Centre, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK. Athens Journal of Architecture 5: 33–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Wenyu. 2023. Centre Pompidou: The Reproduction of Parisian History and Culture in a Postmodernist Building. Studies in Art and Arquitecture 2: 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zukin, Sharon. 1996. The Cultures of Cities. Hoboken: Blackwell Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Zumthor, Peter. 2020. Atmospheres: Architectural Environments—Surrounding Objects. Basel: Birkhäuser. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).