Avant-Texts, Characters and Factoids: Interpreting the Genesis of La luna e i falò Through an Ontology

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. State of the Art

2.1. The Question of the Avant-Text and Its Theoretical Approaches

Biographie et correspondance de l’auteur, connaissance de l’œuvre dans son ensemble, témoignages de tiers, événements historiques, tout cela nous renseigne sur les conditions externes dans lesquelles se situe une genèse. Même les plus farouches adeptes du “ tous les manuscrits et rien que les manuscrits “ font, heureusement, cette incursion biographico-historique qui, cependant, ne permet qu’un constat, non une explication. Mais là où ce type d’investigation serait plus intéressant, c’est-à-dire dans l’évaluation de l’exogenèse et son éventuelle interférence avec le processus d’écriture à proprement parler, les outils nous font cruellement défaut.15.

2.2. The Question of Incompleteness and Processuality of Avant-Text and Its Ontological Modeling

2.3. The Question of Modeling Statements in the Literary Field

- -

- An agent, person or collective entity, creating the factoid.

- -

- A document inspiring the factoid.

- -

- A state of affairs, what the factoid discusses.

3. Real-to-Fictional Ontology

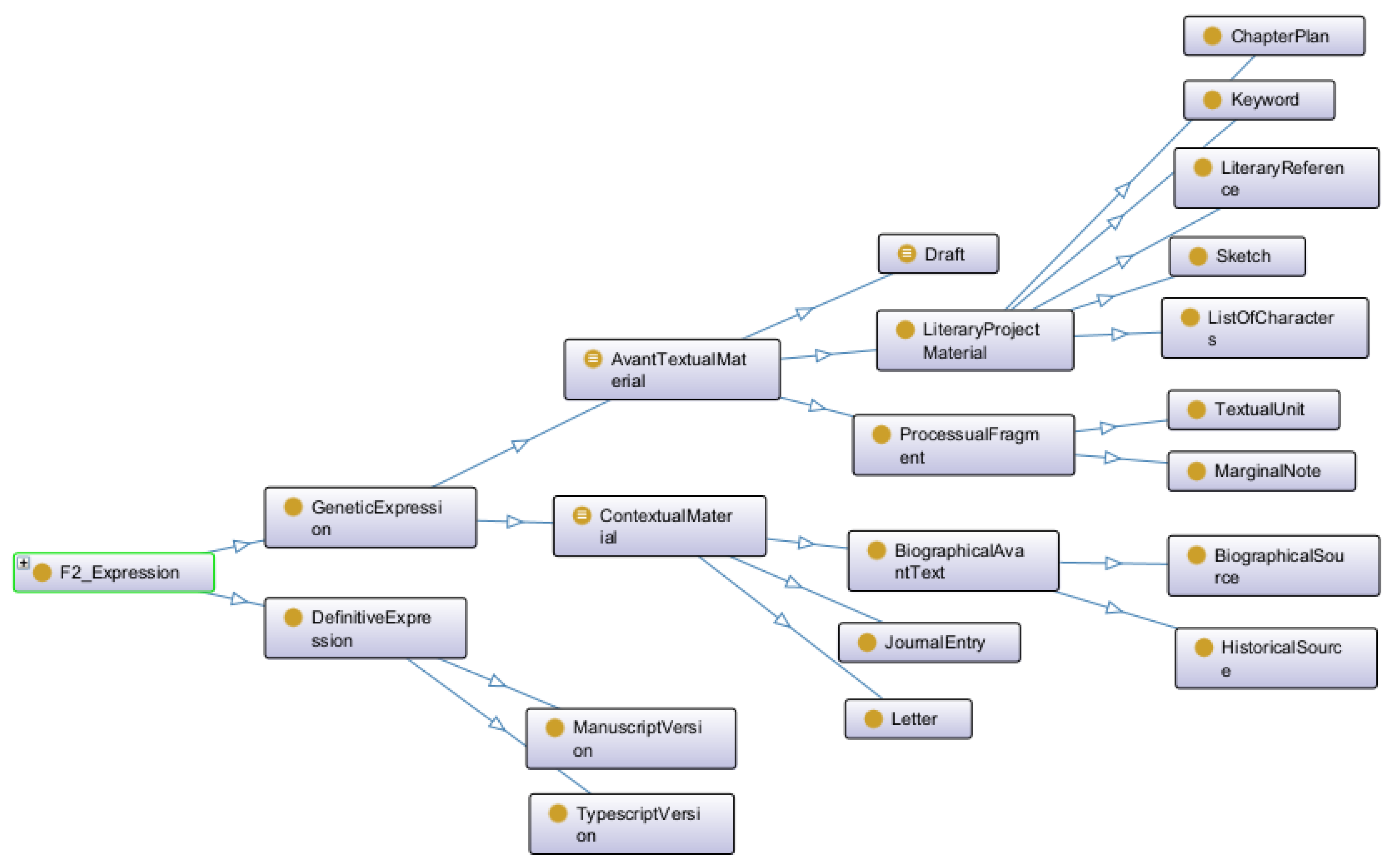

3.1. Semantic Avant-Texts

3.2. Semantic Interpretation

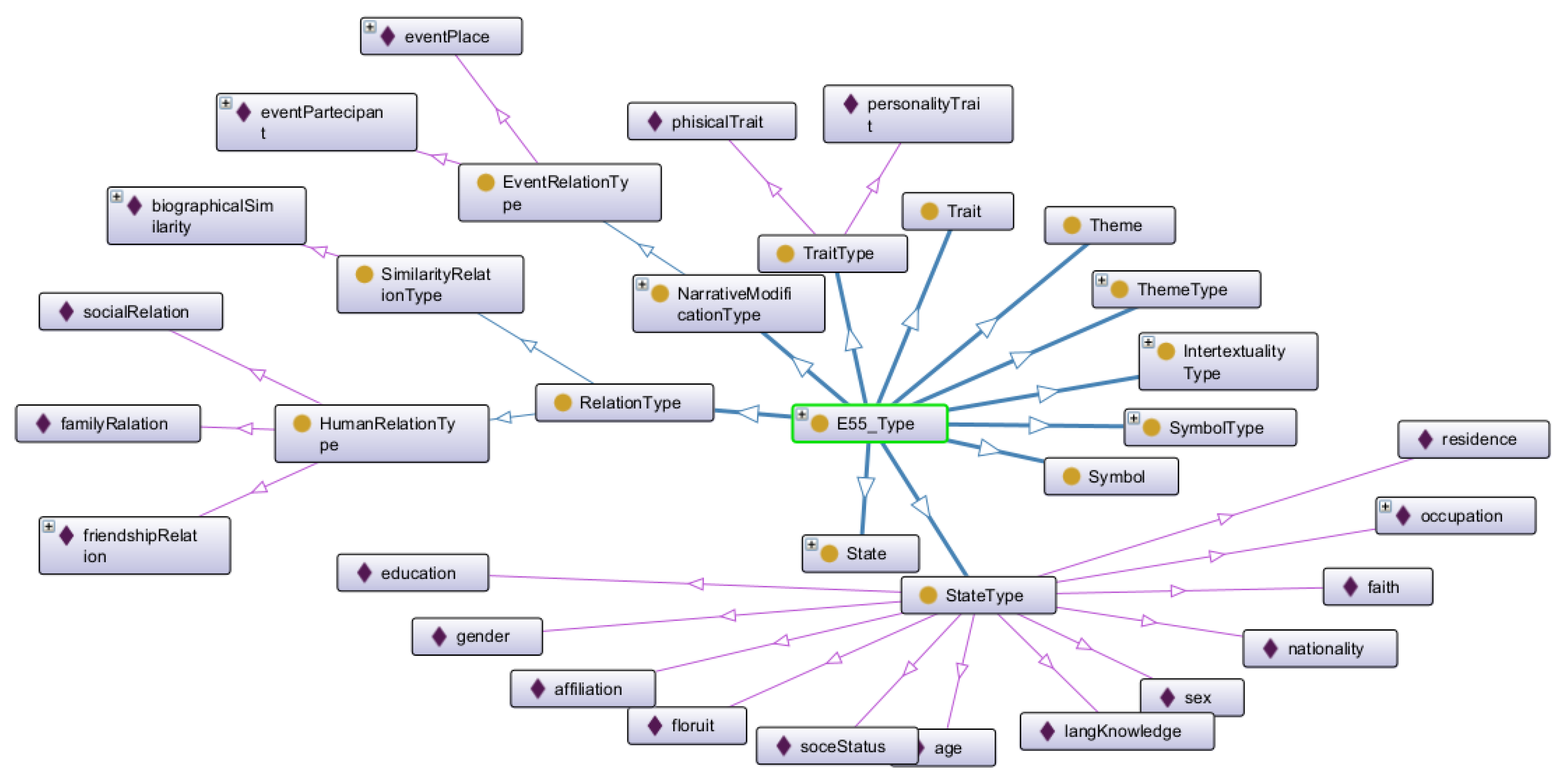

3.2.1. Some Real or Fictional Entity

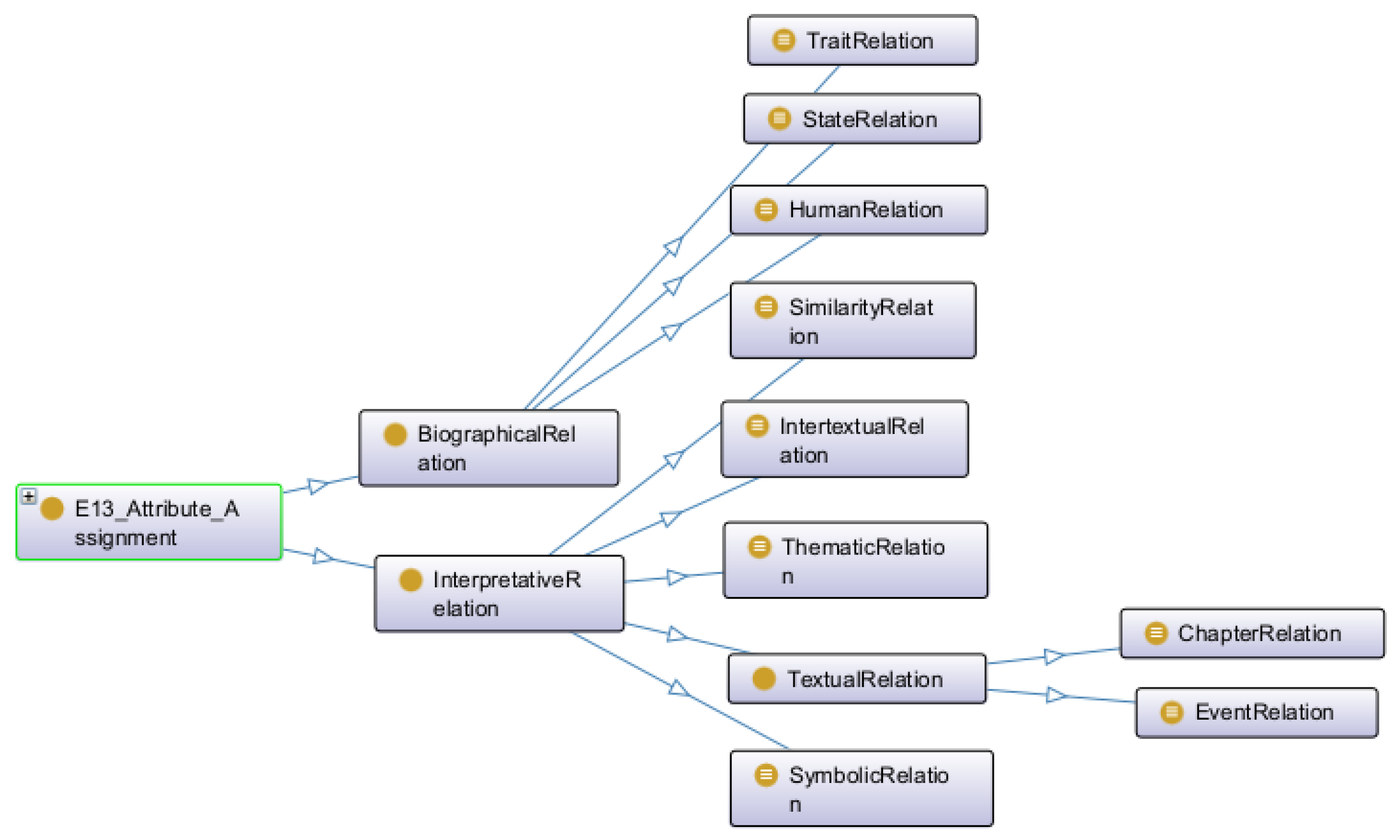

3.2.2. Some Real or Fictional Interpretation

- -

- rtfo:InterpretativeRelation, representing assertions that link real sources to fictional elements. Its subclasses include rtfo:SymbolicRelation, which connects symbols to thematic meanings; rtfo:IntertextualRelation, which maps references to other literary works; rtfo:SimilarityRelation, which links elements based on similarities; rtfo:ThematicRelation, which connects themes to passages or between fictional entities; and rtfo:TextualRelation, which indicates attributes that relate to the text. It has as subclasses rtfo:ChapterRelation, which connects fictional events to the chapter hypothesized in the author’s outlines or later described in a chapter of the final work, and rtfo:EventRelation, to establish which places or participants relate to a specific event.

- -

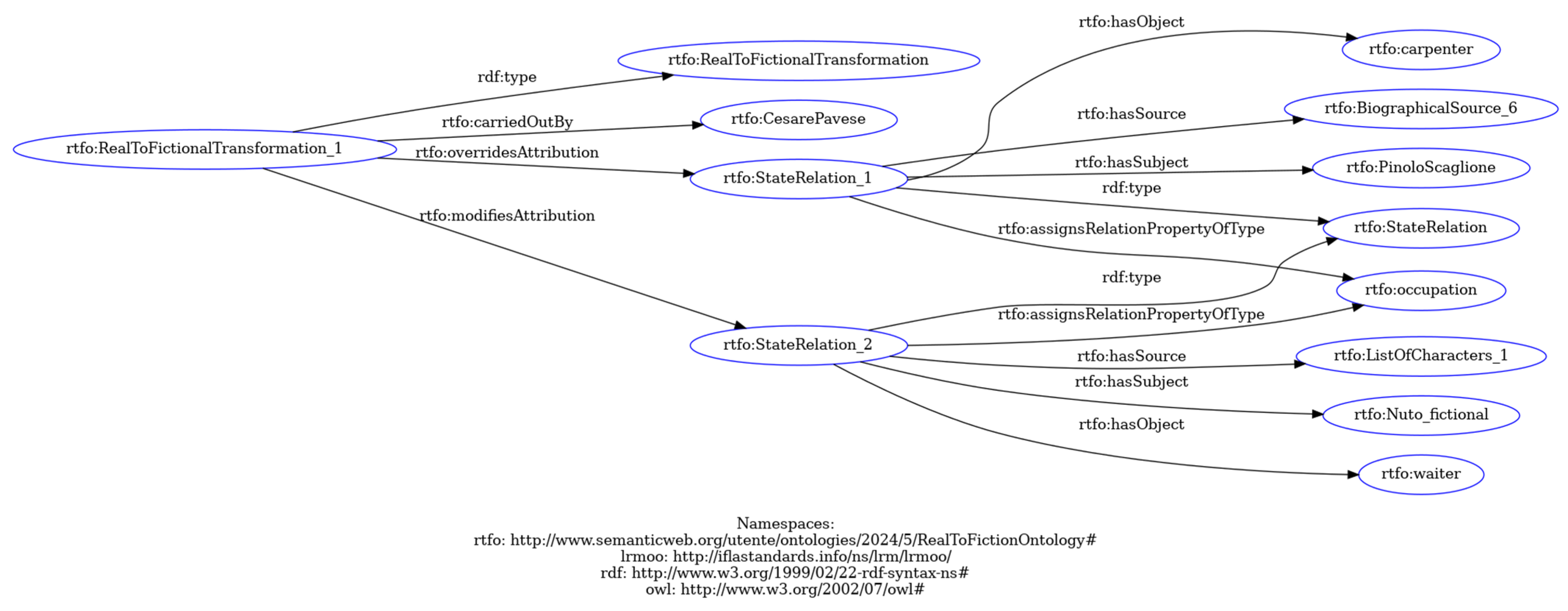

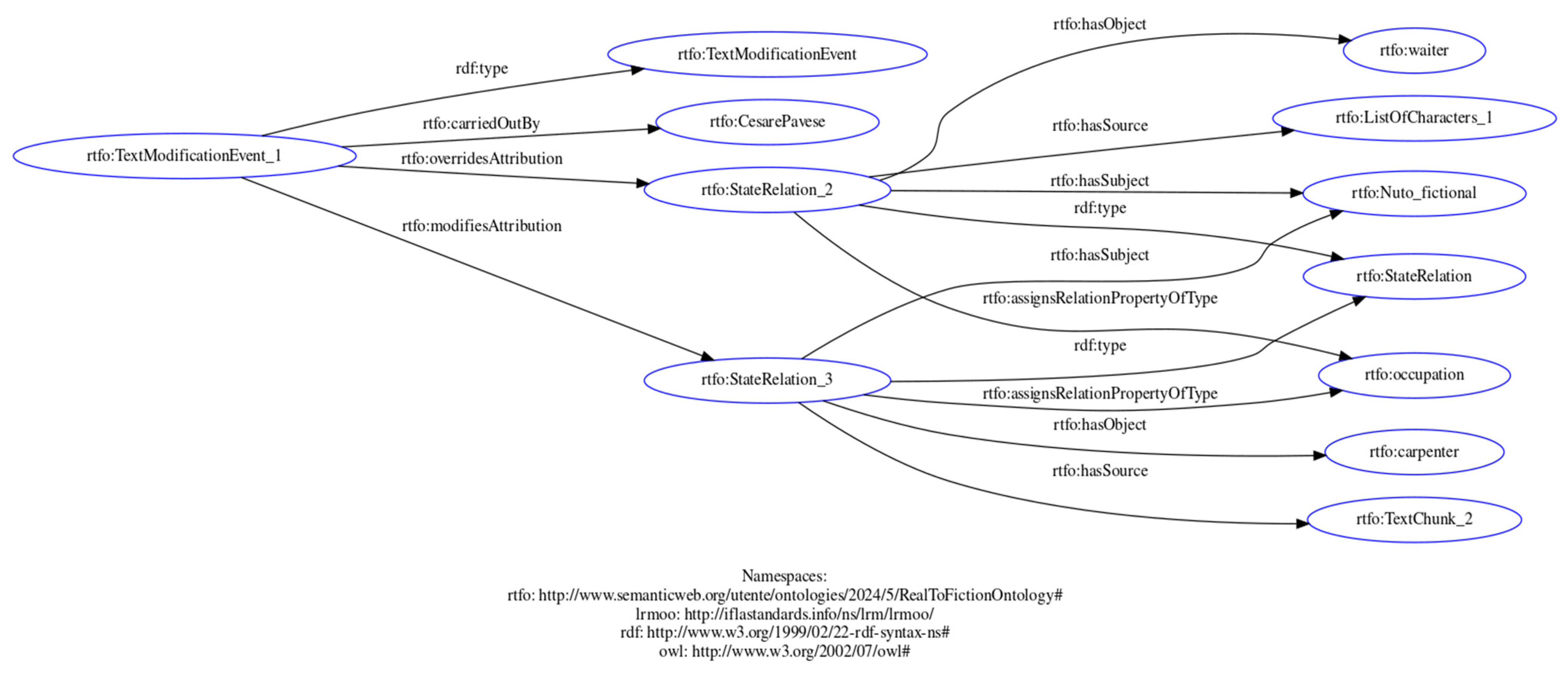

- rtfo:BiographicalRelation, which links real and fictional entities to their characteristics. Its subclasses include rtfo:HumanRelation, which assigns a type of social interaction between two entities; rtfo:StateRelation, which assigns a state to an entity; and rtfo:TraitRelation, which assigns a specific trait to an entity. For example, rtfo:StateRelation can assign Pinolo Scaglione’s occupation ‘carpenter’ to the individual rtfo:Nuto_fictional.

- -

- Subject: the entity whose attribute is being articulated. It is indicated through the object property rtfo:hasSubject, subproperty of P140_assigned_attribute_to, from CIDOC-CRM.

- -

- Object: the type or value assigned to that entity, which must itself be an E55_Type (for traits, states, symbols, themes, etc.). It is indicated through the object property rtfo:hasObject, subproperty of P141_assigned, from CIDOC-CRM.

- -

- rtfo:hasSource, which indicates the textual or historical source of a relationship, under P17_was_motivated_by, from CIDOC-CRM.

- -

- rtfo:assignsRelationPropertyOfType, which assigns a type of property to a relation, under P177_assigned_property_of_type, from CIDOC-CRM.

3.2.3. SWRL Rules

4. Methodology

- −

- CQ1. What preparatory materials are related to the genetic development of the novel La luna e I falò? See Query.A1, in Appendix A.

- −

- CQ2. What participants and places were assigned to the corpse discovery episode during the creative process? See Query.A2, in Appendix A.

- −

- CQ3. What materials from the biographical avant-text of Pinolo Scaglione influenced the preparatory materials and the creation and writing of the novel? See Query.A3, in Appendix A.

4.1. La luna e i falò and Two Case Studies

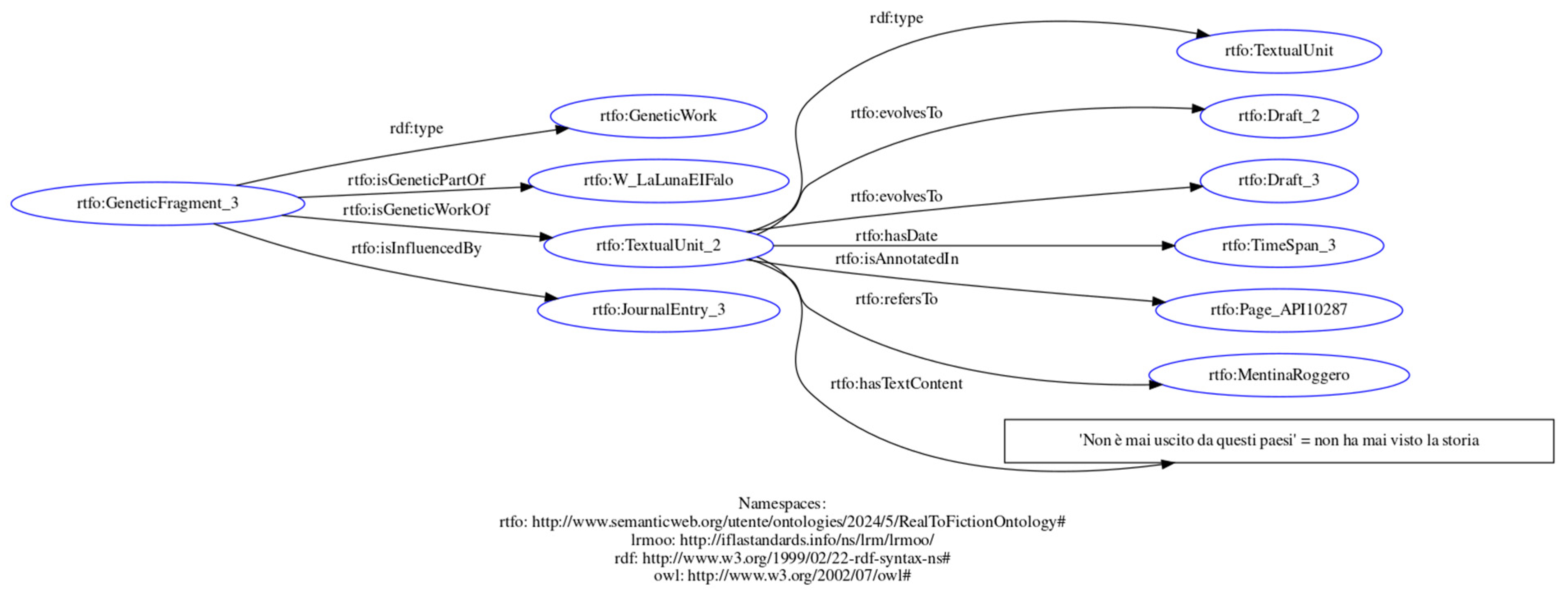

4.1.1. Case Study 1: Mentina Roggero or Nuto or Valino?

- −

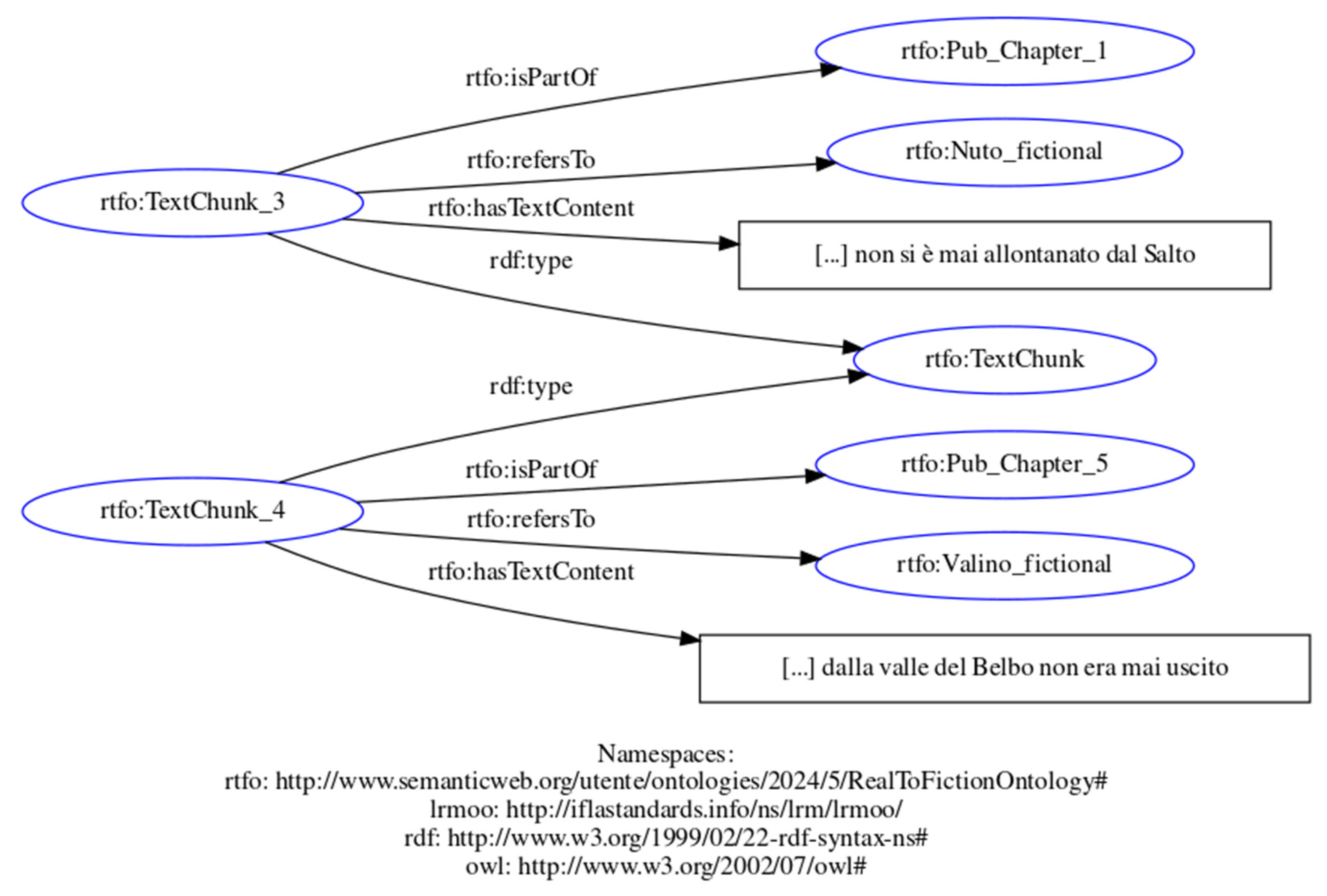

- rtfo:Draft_2, annotated on manuscript page AP I 10, 10 and part of chapter 1 of the manuscript, which refers to the character of Nuto. This draft later evolves into rtfo:TextChunk_3 in chapter 1 of the published novel, where Nuto is described as someone who “[…] never left the Salto” (See Figure 6).

- −

- rtfo:Draft_3, annotated on manuscript page AP I 10, 44 and part of chapter 5 of the manuscript, which refers to the character of Valino. It evolves into rtfo:TextChunk_4 in chapter 5 of the published novel, where it says that Valino “[…] from the Belbo Valley had never left” (See Figure 6).

4.1.2. Case Study 2: Pinolo, Waiter or Carpenter?

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| PREFIX rtfo: <http://www.semanticweb.org/utente/ontologies/2024/5/RealToFictionOntology#> PREFIX cidoc-crm: <http://www.cidoc-crm.org/cidoc-crm/> PREFIX lrmoo: <http://iflastandards.info/ns/lrm/lrmoo/> SELECT DISTINCT ?fragment ?avantText ?draft ?textChunk ?manifestation WHERE { { ?work a rtfo:Novel; rtfo:hasTitle “La luna e i falò”. ?fragment rtfo:isGeneticPartOf ?work; a rtfo:GeneticWork. OPTIONAL { ?fragment rtfo:isGeneticWorkOf ?avantText. ?avantText a ?avantTextClass. FILTER(?avantTextClass! = owl:Nothing) ?avantTextClass rdfs:subClassOf* rtfo:AvantTextualMaterial. OPTIONAL { ?avantText rtfo:evolvesTo ?draft. ?draft a rtfo:Draft. OPTIONAL { ?draft rtfo:evolvesTo ?textChunk. ?textChunk a rtfo:TextChunk; rtfo:isPartOf ?chapter. ?chapter rtfo:isPartOf rtfo:M_LaLunaEIFalo. } } } } UNION { ?work a rtfo:Novel; rtfo:hasTitle “La luna e i falò”; lrmoo:R3_is_realised_in ?expression. ?manifestation lrmoo:R4_embodies ?expression; a ?manifestationType. FILTER(?manifestationType IN (rtfo:Manuscript, rtfo:Typescript)) } } | (Query.A1) |

| PREFIX rtfo: <http://www.semanticweb.org/utente/ontologies/2024/5/RealToFictionOntology#> PREFIX cidoc-crm: <http://www.cidoc-crm.org/cidoc-crm/> PREFIX lrmoo: <http://iflastandards.info/ns/lrm/lrmoo/> SELECT DISTINCT ?participant ?place ?source ?text WHERE { ?eventRelation a rtfo:EventRelation; rtfo:hasSubject rtfo:DiscoveryCorpses_fictional; rtfo:hasObject ?participant; rtfo:hasSource ?source. ?source rtfo:hasTextContent ?text. ?eventRelation2 a rtfo:EventRelation; rtfo:hasSubject rtfo:DiscoveryCorpses_fictional; rtfo:hasObject ?place; rtfo:hasSource ?source. ?source rtfo:hasTextContent ?text. FILTER(?participant! = ?place) } | (Query.A2) |

| PREFIX rtfo: <http://www.semanticweb.org/utente/ontologies/2024/5/RealToFictionOntology#> PREFIX cidoc-crm: <http://www.cidoc-crm.org/cidoc-crm/> PREFIX lrmoo: <http://iflastandards.info/ns/lrm/lrmoo/> SELECT DISTINCT ?biographicalMaterial ?influencedWork ?event ?source ?text WHERE { { ?biographicalMaterial a ?class; rtfo:isStatedBy rtfo:PinoloScaglione; rtfo:hasTextContent ?text. ?class rdfs:subClassOf rtfo:BiographicalAvantText. ?influencedWork a rtfo:GeneticWork; rtfo:isInfluencedBy ?biographicalMaterial. } UNION { VALUES ?event { rtfo:ManuscriptWriting rtfo:CreationLaLunaEIFalo } ?event rtfo:hasSource ?source. ?source rtfo:isStatedBy rtfo:PinoloScaglione; rtfo:hasTextContent ?text. } } ORDER BY ?event | (Query.A3) |

| 1 | This is a digital, multilingual, collaborative lexicon that collects definitions on the broad topic of philology from academic sources, existing essays, not reworking them, but quoting them in the original language; https://lexiconse.uantwerpen.be/ (accessed on 20 July 2025). |

| 2 | Within the LexiconSE, two immediate differences emerge: the choice of documents taken into consideration—all documents for French criticism, only those in relation to the final text for Italian—and the consequent different methodological approach—full publication in edition for works of genetic criticism and separate appendix for drafts that do not fall under apparatus for authorial philology (Dillen et al. 2016, pp. 191–96). |

| 3 | As exemples, the site dedicated to Flaubert and his work, founded in 2001 by Yvan Leclerc at the University of Rouen, https://flaubert.univ-rouen.fr/ (accessed on 20 July 2025); la Digitale Kritische Gesamtausgabe Werke und Briefe (eKGWB), on the work and letters of Nietzsche, edited by Paolo D’Iorio and published by Nietzsche Source, which is run by the HyperNietzsche association, a non-profit organisation based at the École normale supérieure in Paris, http://doc.nietzschesource.org/de/ (accessed on 20 July 2025); Manzoni online portal dedicated to the writings and library of Alessandro Manzoni, a project that sees the collaboration of scholars from the Universities of Parma, Milan, Pavia, Lausanne (Switzerland), Bologna and Rome with the Biblioteca Nazionale Braidense (BNB) and the Centro Nazionale di Studi Manzoniani (CNSM), https://www.alessandromanzoni.org/ (accessed on 20 July 2025). |

| 4 | The Semantic Web was conceived to structure web content in a computer-readable way via RDF, a framework that describes properties and relationships between entities through triples (subject–predicate–object), uniquely identified by IRIs (Berners-Lee et al. 2001). This approach resolves data ambiguity and facilitates automation and interoperability (Shadbolt et al. 2006). Ontologies—models for formalizing a knowledge domain (Gruber 2009)—describe concepts and relationships using controlled vocabularies expressed in languages like RDFs and OWL, with formal constraints for coherent use. |

| 5 | https://github.com/giu-arena/RTFO (accessed on 20 July 2025). |

| 6 | In-depth research was conducted on the theoretical aspects of organizing avant-texts. This was followed by a survey of materials related to the ontology’s domain, namely the philological materials of La luna e i falò. For Pinolo Scaglione’s biographical avant-text materials, the volume Fumatori di Carta by Franco Vaccaneo, which includes a first unpublished transcription of some of Pinolo’s autograph manuscripts, as well as transcriptions of interviews, articles by Pinolo and detailed biographies of his life in relation to Pavese’s, has turned out to be fundamental (Vaccaneo and Antonicelli 1999). But we also considered other sources (Lajolo 2008; Vaccaneo 1989). |

| 7 | Antonio Di Silvestro (Di Silvestro 2021, p. 173) mentions the term relatively properly in relation to Pinolo Scaglione and the drafts of the poem Fumatori di carta. The draft copy of the poem, written in August–September 1932 and published in Lavorare stanca in 1936, is read again by Pavese on 30 July 1949 and reports some verses deleted in the diary: “Ho rivisto la luna d’agosto tra ontani e canneti/sulle ghiare del belbo e riempirsi d’argento/ogni filo di quella corrente. Ma il chiuso compagno/che sedeva su un tronvo con me, non vedeva quel cielo/non sentiva le piante. Sapevo che intorno/tutt’introno s’alzavano le grandi colline…” (Pavese 2020, p. 372). This verses take up the great themes that will belong to La luna e i falò, and the poem as a whole represents the first literary description of his friend Pinolo (Di Silvestro 2021, pp. 166–68). |

| 8 | https://cidoc-crm.org/lrmoo (accessed on 20 July 2025). Version 1.0. |

| 9 | https://cidoc-crm.org/ (accessed on 20 July 2025). Version 7.1.3. |

| 10 | “[…] an avant-text is a certain reconstruction of what preceded a text, established by a critic using a specific method, to be the object of a reading in continuity with the definitive data”. Translation by the author. |

| 11 | “a set of written documents that can be attributed in retrospect to a specific writing project, regardless of whether or not it resulted in a published text”. Translation by the author. |

| 12 | Maria Corti, while having the merit of having first used, in Italy, the term avantesto, does so with an interpretation far from that with which Bellemin Noël unified the term. Corti investigates the problem of the distinction between poetic and non-poetic, of the creative energy that imputs the avantesto and has the poetic text as output, taking into account the idea of text as ‘approximation to value’ from Gianfranco Contini’s theories (Corti 1976, pp. 98–106). These arguments are then taken up in Basile (Basile 1979). On the debate, Segre writes: “Ogni abbozzo o prima copia è, dal punto di vista linguistico, un testo, con la sua coerenza. Anche se si allineano tutti i testi anteriori di un’opera in ordine cronologico non si ottiene una diacronia, ma una serie di sincronie successive. Quando un manoscritto sia stato ritoccato piú volte in tempi diversi, sarebbe corretto considerarlo come una sovrapposizione di sincronie, e di testi. Perciò, se il concetto di avantesto ambisse a indicare la produttività letteraria o poetica in opera, si sarebbe destinati a grandi delusioni. È invece sicuro che, considerando ogni testo come un sistema, i testi successivi possono apparire come l’effetto di spinte presenti in quelli precedenti, mentre a loro volta contengono spinte di cui i testi successivi saranno il risultato. In questo modo l’analisi della storia redazionale e delle varianti ci fa conoscere parzialmente il dinamismo presente nell’attività creativa” (Segre 1985, p. 79). |

| 13 | “[…] the set of material data relating to everything that preceded the text”. Translation by the author. |

| 14 | “[…] one must distinguish, as far as possible, between preparatory materials and texts, that is, for example, between a list of Sicilian proverbs and the manuscripts where I Malavoglia begins to take shape”. Translation by the author. |

| 15 | “The author’s biography and correspondence, knowledge of the work as a whole, third-party testimonies, historical events—all these provide information about the external conditions in which a genesis takes place. Fortunately, even the most zealous adherents of the ‘all manuscripts and nothing but the manuscripts’ approach make this biographical-historical incursion, which, however, only allows us to make an observation, not an explanation. But where this type of investigation would be more interesting, i.e., in the evaluation of exogenesis and its possible interference with the actual writing process, the tools are cruelly lacking”. Translation by the author. |

| 16 | The autograph manuscript of La luna e i falò, belonging to the Fondo Sini and marked “AP I 10”, comprises 286 pages, almost all of them grainy, 272 × 206 mm, signed on the recto, with Pavese autonomously numbering the pages in each of the 32 chapters of the novel. The pages of the avant-text (287–301), of various formats, contain notes, notes, diagrams, literary plans and sketches that have more or less directly to do with the chronologically parallel process of writing the novel. Sometimes the patterns of the chapters plotted do not actually match the draft. Within the same paper there may be several notes, dated at different time points. The notes often have erasures. The typescript, belonging to the Einaudi Fund and marked “FE 16—Romanzi IV”, includes 133 pages, of mm 287 × 210, written in black ink. The text has a limited number of corrections. The printed edition, included in the series “Coralli nell’aprile del 1950”, was supervised by the author, but two errors were corrected in the reprint of October (Masoero and Sensi 2000). The text of the second edition is that followed by the 2021 edition Mondadori, curated by Antonio Sichera and Antonio Di Silvestro, chosen as the base text for the study of this research work (Pavese 2021). For a more detailed description of the materials of the avant-text, see the critical edition of La luna e i falò edited by Miryam Grasso, who describes them for the first time, following their thematic and textual development, and offers a transcription in the appendix (Grasso 2020). |

| 17 | https://gen-o.github.io/ (accessed on 20 July 2025). |

| 18 | https://www.w3.org/TR/prov-o/ (accessed on 20 July 2025). |

| 19 | https://marilenadaquino.github.io/hico/ (accessed on 20 July 2025). |

| 20 | This approach, developed in research projects such as those at King’s College London since the 1990s, comes from prosopography, a historical methodology that analyzes premodern individuals and societies through fragmentary sources (Ciula and Marras 2023, p. 59). The term was first used within the article A factoid is not a small fact (Marsh 2014). |

| 21 | Bradley also created a more structured ontology for prosopography, the Factoid Prosopography Ontology, https://github.com/johnBradley501/FPO (accessed on 20 July 2025), with the goal of being interoperable among different projects at King’s College London. Since it is a ‘minimal core’, it is possible to extend it with additional subclasses and properties (in fact, no project uses it as is) and link it to standards such as CIDOC-CRM, FRBRoo and TEI for dates, while not implementing them directly. https://www.kcl.ac.uk/factoid-prosopography/ontology (accessed on 20 July 2025). |

| 22 | https://www.w3.org/TR/swbp-n-aryRelations/ (accessed on 20 July 2025). |

| 23 | For a complete description of the complex axioms of these classes and all properties not described in this paper, please refer to the OWL file of RTFO on GitHub. |

| 24 | Anticipating future integration of the ontology into a digital critical edition of the materials and the novel, we attempted to follow Text Encoding Initiative (TEI) guidelines, particularly for structuring biographical prosopographical data, https://www.tei-c.org/release//doc/tei-p5-doc/it/html/ND.html#NDPERS (accessed on 20 July 2025): <state></state>, “characteristics or states which hold true only at a specific time”; <trait></trait>, “characteristics or traits which do not, by and large, change over time”; <event></event>, “events or incidents which may lead to a change of state or, less frequently, trait”. Tags from Personal Characteristics, https://www.tei-c.org/release//doc/tei-p5-doc/it/html/ND.html#NDPERSEpc (accessed on 20 July 2025) became individuals of the class rtfo:StateType. |

| 25 | https://www.w3.org/submissions/SWRL/ (accessed on 20 July 2025). |

| 26 | In Il mestiere di vivere, Pavese notes on 17 November 1949: “9 nov. finito la Luna e i Falò. Dal 18 sett. quando realmente Pavese iniziò la stesura del romanzo sono meno di due mesi. Quasi sempre un capitolo al giorno. É certo l’exploit più forte sinora. Se risponde, sei a posto” (Pavese 2020, p. 375). To Aldo Camerino on 30 May 1950, after the publication of the novel, he writes: “Effettivamente La luna è il libro che mi portavo dentro da più tempo e che ho goduto di più scrivere. Tanto che credo credo che per un pezzo—forse sempre—non farò più altro. Non conviene tentare troppo gli dèi” (Pavese 1966, p. 532). |

| 27 | Unsurprisingly, it has been described as an “autobiografia simbolica” (Nay and Zaccaria 2000, p. 1110) or “realismo simbolico” (Scioli 2021, p. 25), where the grand themes of Pavese’s work intersect the public and private in a confessional dimension. For a summary of the interpretative difficulties of the work, between the symbolic dimension and the historical–social dimension, see also (Catalfamo 2012). |

| 28 | From a radio investigation conducted by the journalist Mario Pogliotti, aired on 15 August 1960. Following the intervention of Pinolo Scaglione: “È stato io credo nel ‘49, verso il ‘49. Per scrivere questo libro è venuto due o tre volte più del solito a Santo Stefano: ha voluto sapere da me la storia di tutte queste case: ci siamo fermati durante una passeggiata su un colle, il Brich di Min. Giunto su questo colle, mi invita a raccontare qualche cosa di questi posti. Allora, dalla prima casa che ha colpito il mio occhio, io ho narrato… ho raccontato qualche cosa degli abitanti di questa casa, ma sono andato indietro nei miei ricordi, e poi mi son spostato a un’altra, a un’altra, a un’altra… Cesare prende una matita e un foglio di carta: fa un circolino e tante ramificazioni, a mano a mano che io parlavo, faceva una lineetta… tracciava una lineetta e metteva dei nomi e faceva dei segni. Mi ha lasciato parlare parecchio e poi mi detto: beh, per questa mattina ne abbiamo abbastanza. Abbiamo preso la strada e siamo ritornati a casa. Questo qui è stato il principio della Luna e i falò” (Pogliotti 1999, p. 254). |

| 29 | “To Pinolo this book—perhaps the last one I will ever write—where he is talked about, apologizing for the inventions”. Translation by the author. |

| 30 | https://www.ldf.fi/service/rdf-grapher (accessed on 20 July 2025). |

References

- Andrews, Tara L. 2024. «The medieval Mediterranean in… data? Interpretation, conjecture and digital methods». In Me.Te. Digitali. Mediterraneo in rete tra testi e contesti, Proceedings del XIII Convegno Annuale AIUCD2024. di Antonio Di Silvestro e Daria Spampinato. Catania: AIUCD. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, Tara L., Marius Deierl, and Carla Ebel. 2024. «Gender Assignment as an Event—A Contemporary Approach for the Adequate Depiction of Historical Gender Categories». Digital Scholarship in the Humanities 39: 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baillie, James, Tara L. Andrews, Maxim Romanov, Daniel Knox, and Maria Vargha. 2021. «Modelling Historical Information with Structured Assertion Records». Digital History Berlin, February 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartalesi, Valentina, Carlo Meghini, and Daniele Metilli. 2016. «Steps Towards a Formal Ontology of Narratives Based on Narratology». 7th workshop on Computational Models of Narrative (CMN 2016). Wadern: Schloss Dagstuhl–Leibniz-Zentrum für Informatik. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartalesi, Valentina, Nicolò Pratelli, Carlo Meghini, Daniele Metilli, Gaia Tomazzoli, Leyla MG Livraghi, and Michelangelo Zaccarello. 2022. «A Formal Representation of the Divine Comedy’s Primary Sources: The Hypermedia Dante Network Ontology». Digital Scholarship in the Humanities 37: 630–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basile, Bruno. 1979. «Verso una dinamica letteraria: Testo e avantesto». Lingua e Stile XIV: 395–410. [Google Scholar]

- Bekiari, Chryssoula, Martin Doerr, Patrick Le Boeuf, and Maja Žumer. 2024. LRMOO Object-Oriented Definition and Mapping from the IFLA Library Reference Model. Available online: https://cidoc-crm.org/sites/default/files/LRMoo_V1.0.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Bellemin-Noël, Jean. 1972. Le texte et l’avant-texte. Les brouillons d’un poème de Milosz. Paris: Larousse. [Google Scholar]

- Bellemin-Noël, Jean. 1977. «Reproduire le manuscrit, présenter les brouillons, établir un avant-texte». Littératures 18: 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellemin-Noël, Jean. 1979. Vers l’inconscient du texte, 1st ed. Ecriture. Paris: Puf. [Google Scholar]

- Bellemin-Noël, Jean. 2004. «Psychoanalytic Reading and the Avant-texte». In Genetic Criticism: Texts and Avant-Textes. Edited by Jed Deppman, Daniel Ferrer and Michael Groden. Material Texts. Philadelphia: PENN, University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Berners-Lee, Tim, James Hendler, and Ora Lassila. 2001. «The Semantic Web: A New Form of Web Content That Is Meaningful to Computers Will Unleash a Revolution of New Possibilities». Scientific American Magazine 284: 34–43. Available online: https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3591366.3591376 (accessed on 20 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- Cadioli, Alberto. 2017. «Brevi considerazioni sul confronto tra critica genetica e filologia d’autore». Sistemi in Movimento. Avantesto e Varianti dal Laboratorio D’autore al Laboratorio Critico 57: 189–94. [Google Scholar]

- Catalfamo, Antonio. 2012. «Cesare Pavese: Storia, territorio e simbolo ne “La luna e i falò”». In Cesare Pavese: Mondi e sottomondi: Undicesima Rassegna di Saggi Internazionali di Critica Pavesiana, 2nd ed. a cura di Antonio Catalfamo. I Quaderni del CE.PA.M. Catania: CUECM. [Google Scholar]

- Christen, Alessio, and Elena Spadini. 2019. «Modeling Genetic Networks. Gustave Roud’s Œuvre, from Diary to Poetry Collections». Umanistica Digitale 7: 77–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciotti, Fabio. 2012. «Web semantico, linked data e studi letterari: Verso una nuova convergenza». Quaderni Digilab 2: 243–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciotti, Fabio. 2016. «Toward a Formal Ontology for Narrative». Matlit Revista Do Programa de Doutoramento Em Materialidades Da Literatura 4: 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciula, Arianna, and Cristina Marras. 2023. «Modelli, metamodelli e modellizazione nelle Digital Humanities». In Digital Humanities: Metodi, Strumenti, Saperi, 1st ed. a cura diFabio Ciotti. Studi superiori; Teoria della letteratura e critica letteraria 1376. Roma: Carocci editore. [Google Scholar]

- Ciula, Arianna, Øyvind Eide, Cristina Marras, and Patrick Sahle. 2023. Modelling Between Digital and Humanities: Thinking in Practice, 1st ed. Cambridge: Open Book Publishers. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corti, Maria. 1976. Principi Della Comunicazione Letteraria. Prima edizione. Studi Bompiani 17/Il campo semiotico (a cura di Umberto Eco). Milan: Bompiani. [Google Scholar]

- Daquino, Marilena, and Francesca Tomasi. 2015. «Historical Context Ontology (HiCO): A Conceptual Model for Describing Context Information of Cultural Heritage Objects». In Metadata and Semantics Research. Edited by Emmanouel Garoufallou, Richard J. Hartley and Panorea Gaitanou. Communications in Computer and Information Science. Cham: Springer International Publishing, vol. 544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daquino, Marilena, Valentina Pasqual, Francesca Tomasi, and Fabio Vitali. 2022. «Expressing Without Asserting in the Arts». Paper presented at IRCDL 2022: 18th Italian Research Conference on Digital Libraries, Padova, Italy, February 24–25; CEUR Workshop Proceedings. Available online: https://ceur-ws.org/Vol-3643/paper7.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- De Biasi, Pierre-Marc, and Ingrid Wassenaar. 1996. «What is a Literary Draft? Toward a Functional Typology of Genetic Documentation». Yale French Studies 89: 26–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillen, Wout, Elena Spadini, and Monica Zanardo. 2016. «Il “Lexicon of Scholarly Editing”: Una bussola nella Babele delle tradizioni filologiche». Ecdotica 13: 169–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Silvestro, Antonio. 2021. «Nota al testo». In La luna e i falò. Edited by Cesare Pavese, Antonio Sichera and Antonio Di Silvestro. Milan: Mondadori. [Google Scholar]

- Doerr, Martin. 2003. «The CIDOC Conceptual Reference Module: An Ontological Approach to Semantic Interoperability of Metadata». AI Magazine 24: 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasso, Miryam. 2020. La luna e i falò, edizione critica a cura di. Avellino: Edizioni Sinestesie. [Google Scholar]

- Grésillon, Almuth. 1994. Éléments de critique génétique: Lire les Manuscrits Modernes. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. [Google Scholar]

- Grésillon, Almuth. 1998. «La Critique Génétique: Origines et méthodes». In Genesi, Critica, Edizione: Atti del Convegno Internazionale di Studi, Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa, 11–13 Aprile 1996. Edited by Paolo D’Iorio and Nathalie Ferrand. Pisa: Edizioni della Normale. [Google Scholar]

- Groth, Paul, Andrew Gibson, and Jan Velterop. 2010. «The Anatomy of a Nanopublication». Information Services & Use 30: 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, Tom. 2009. «Ontology». In Encyclopedia of Database Systems. Edited by Ling Liu and M. Tamer Özsu. Berlin: Springer. Available online: https://tomgruber.org/writing/definition-of-ontology.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Italia, Paola. 2020. Editing Duemila: Per una Filologia dei Testi Digitali. Strumenti per l’università 9. Rome: Salerno editrice. [Google Scholar]

- Italia, Paola, and Giulia Raboni. 2010. Che cos’è la Filologia D’autore, 1st ed. Le bussole Studi linguistico-letterari 408. Rome: Carocci Editore. [Google Scholar]

- Jordanous, Anna, K. Faith Lawrence, Mark Hedges, and Charlotte Tupman. 2012. «Exploring Manuscripts: Sharing Ancient Wisdoms across the Semantic Web». Paper presented at 2nd International Conference on Web Intelligence, Mining and Semantics, Craiova, Romania, June 13; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowaleski, Maryanne. 2021. «A New Digital Prosopography: The Medieval Londoners Database». Medieval People: Social Bonds, Kinship, and Networks 36: 311–22. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/27206826 (accessed on 30 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- Lajolo, Davide. 2008. Il Vizio Assurdo: Storia di Cesare Pavese. Turin: Piazza. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, David. 2014. «A Factoid Is Not a Small Fact. Fact». Media. The Guardian. January 17. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/media/mind-your-language/2014/jan/17/mind-your-language-factoids (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Masoero, Mariarosa, and Claudio Sensi. 2000. «Notizie sul testo». In Tutti i romanzi. Edited by Cesare Pavese and Marziano Guglielminetti. Biblioteca della Pléiade, n. 34. Turin: Einaudi. [Google Scholar]

- Massari, Arcangelo, Silvio Peroni, Francesca Tomasi, and Ivan Heibi. 2025. Representing Provenance and Track Changes of Cultural Heritage Metadata in RDF: A Survey of Existing Approaches. Digital Scholarship in the Humanities, fqaf076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nava, Beatrice. 2023. «Siamo tutti bédieriani? Prospettive per le edizioni genetiche digitali». Umanistica Digitale 6: 19–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nay, Laura, and Giuseppe Zaccaria. 2000. «La luna e i falò: Nota». In Tutti i romanzi. Edited by Cesare Pavese and Marziano Guglielminetti. Biblioteca della Pléiade, n. 34. Turin: Einaudi. [Google Scholar]

- Orlandi, Fabrizio, Damien Graux, and Declan O’Sullivan. 2021. «Benchmarking RDF Metadata Representations: Reification, Singleton Property and RDF». Paper presented at 2021 IEEE 15th International Conference on Semantic Computing (ICSC) Laguna Hills, January 27–29; pp. 233–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasin, Michele, and John Bradley. 2015. «Factoid-Based Prosopography and Computer Ontologies: Towards an Integrated Approach». Digital Scholarship in the Humanities 30: 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavese, Cesare. 1950. La luna e i falò. I Coralli 48. Turin: Einaudi. [Google Scholar]

- Pavese, Cesare. 1966. Lettere. 1945–1950. Edited by Italo Calvino. Turin: Einaudi. [Google Scholar]

- Pavese, Cesare. 2020. Il mestiere di vivere: Diario 1935–1950. Edited by Marziano Guglielminetti and Laura Nay. ET Scrittori. Turin: Einaudi. [Google Scholar]

- Pavese, Cesare. 2021. La luna e i falò. Edited by Antonio Sichera and Antonio Di Silvestro. Milan: Mondadori. [Google Scholar]

- Pogliotti, Mario. 1999. «Un paese vuol dire…». In Fumatori di carta: Nuto e Pavese. Edited by Franco Vaccaneo and Franco Antonicelli. Turin: Omega. [Google Scholar]

- Poveda-Villalón, María, Alba Fernández-Izquierdo, Mariano Fernández-López, and Raúl García-Castro. 2022. LOT: An Industrial Oriented Ontology Engineering Framework. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 111: 104755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanfilippo, Emilio M. 2021. «Ontologies for Information Entities: State of the Art and Open Challenges». Applied Ontology 16: 111–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanfilippo, Emilio M., and Roberta Ferrario. 2024. D3.1—Observations Modeling: State of the Art. Project Report. May 31. Available online: https://www.loa.istc.cnr.it/mite/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/MITE_D3_1.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Sanfilippo, Emilio M., Antonio Sotgiu, Gaia Tomazzoli, Claudio Masolo, Daniele Porello, and Roberta Ferrario. 2023. «Ontological Modeling of Scholarly Statements: A Case Study in Literary Criticism». In Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence and Applications. Edited by Nathalie Aussenac-Gilles, Torsten Hahmann, Antony Galton and Maria M. Hedblom. Amsterdam: IOS Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanfilippo, Emilio M., Laura Antonietti, and Elena Pierazzo. 2024. «Texts and Works: Ontology-Based Modeling Patterns». Atto di convegno presented a JOWO 2024 The Joint Ontology Workshops. Paper presented at Joint Ontology Workshops (JOWO)—Episode X: The Tukker Zomer of Ontology, and Satellite Events Co-Located with the 14th International Conference on Formal Ontology in Information Systems (FOIS 2024), Enschede, The Netherlands, July 15–19; Available online: https://ceur-ws.org/Vol-3882/yoda-2.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Scaglione, Giuseppe. 1970. «L’infelice esistenza del poeta e scrittore Cesare Pavese raccontata da un suo amico artigiano». «La Voce dell’Artigiano», organo dell’Associazione artigiani della Provincia di Cuneo XIV: 3. [Google Scholar]

- Schöch, Christof, Maria Hinzmann, Julia Röttgermann, Katharina Dietz, and Anne Klee. 2022. «Smart Modelling for Literary History». International Journal of Humanities and Arts Computing 16: 78–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, Daniel L., Nathan P. Gibson, and Katayoun Torabi. 2022. «Modeling a Born-Digital Factoid Prosopography Using the TEI and Linked Data». Journal of the Text Encoding Initiative. Rolling Issue. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scioli, Stefano. 2021. «Introduzione». In La luna e i falò. Edited by Cesare Pavese. Milan: Feltrinelli. [Google Scholar]

- Segre, Cesare. 1985. Avviamento all’analisi del testo letterario. Turin: Einaudi. [Google Scholar]

- Segre, Cesare. 1995. «Critique des variantes et critique génétique». Genesis 7: 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segre, Cesare. 1998. «Critica genetica e studi sulle fonti». In Genesi, critica, edizione: Atti del convegno internazionale di studi, Scuola normale superiore di Pisa, 11–13 Aprile 1996. Edited by Paolo D’Iorio and Nathalie Ferrand. Pisa: Edizioni della Normale. [Google Scholar]

- Shadbolt, Nigel, Tim Berners-Lee, and Wendy Hall. 2006. «The Semantic Web Revisited». IEEE Intelligent Systems 21: 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stussi, Alfredo. 2011. Introduzione agli studi di filologia italiana, 4th ed. Manuali. Bologna: Il Mulino. [Google Scholar]

- Tomasi, Francesca. 2022. Organizzare la conoscenza: Digital humanities e web semantico: Un percorso tra archivi, biblioteche e musei. Biblioteconomia e scienza dell’informazione 39. Milan: Editrice Bibliografica. [Google Scholar]

- Tuominen, Jouni, Eero Hyvönen, and Petri Leskinen. 2017. «Bio CRM: A Data Model for Representing Biographical Data for Prosopographical Research». Paper presented at Second Conference on Biographical Data in a Digital World 2017, Linz, Austria, November 6–7; Edited by A. Fokkens, S. ter Braake, R. Sluijter, P. Arthur and E. Wandl-Vogt. CEUR Workshop Proceedings. Aachen: RWTH Aachen University, vol. 2119. Available online: http://ceur-ws.org/Vol-2119/paper10.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Vaccaneo, Franco. 1989. Cesare Pavese: Biografia per immagini: La vita, i libri, le carte, i luoghi, 3rd ed. Biografie per immagini 1. Cavallermaggiore: Gribaudo. [Google Scholar]

- Vaccaneo, Franco. 1999. «Tra Nuto e Pavese». In Fumatori di carta: Nuto e Pavese. Edited by Franco Antonicelli and Franco Vaccaneo. Turin: Omega. [Google Scholar]

- Vaccaneo, Franco, and Franco Antonicelli. 1999. Fumatori di carta: Nuto e Pavese. Turin: Omega. [Google Scholar]

- Van Hulle, Dirk. 2004. Textual Awareness: A Genetic Study of Late Manuscripts by Joyce, Proust, and Mann. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hulle, Dirk. 2019. «Modern Manuscripts». In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Literature. Edited by Dirk Van Hulle. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arena, G. Avant-Texts, Characters and Factoids: Interpreting the Genesis of La luna e i falò Through an Ontology. Humanities 2025, 14, 162. https://doi.org/10.3390/h14080162

Arena G. Avant-Texts, Characters and Factoids: Interpreting the Genesis of La luna e i falò Through an Ontology. Humanities. 2025; 14(8):162. https://doi.org/10.3390/h14080162

Chicago/Turabian StyleArena, Giuseppe. 2025. "Avant-Texts, Characters and Factoids: Interpreting the Genesis of La luna e i falò Through an Ontology" Humanities 14, no. 8: 162. https://doi.org/10.3390/h14080162

APA StyleArena, G. (2025). Avant-Texts, Characters and Factoids: Interpreting the Genesis of La luna e i falò Through an Ontology. Humanities, 14(8), 162. https://doi.org/10.3390/h14080162