1. Introduction

Immigration policy is one of the areas with the highest levels of tension in international politics within recent academic literature. There are several approaches to the issue, ranging from social policies (

Ataç and Rosenberger 2019) to those of integration (

Bauböck and Tripkovic 2017), as well as migration securitization (

Bourbeau 2013). States have proven incapable of controlling migration flows due to economic globalization and the human rights discourse (

Mair 2009). The control of borders and the development of effective migration policies have sparked a debate on the current conditions of dealing with refugees, asylum seekers, and displaced persons (

Czaika and De Haas 2013). This article analyzes the way in which cities of Europe and the United States have responded to the phenomenon of research within a political context of populism and nationalism. The main argument is that cities, along with their citizens and mayors, have taken a political position contrary to the Trump doctrine that criminalizes migration. From the United States to Spain, and continuing through the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, and Italy, cities are proposing alternative public policies contrary to the crime prevention strategy. Cities offer a policy of

fait accompli, as immigrants have chosen to live in urban settings according to their legal status. Faced with an aggressive Trump-style discourse, which includes the use of social networks and the media, urban leaders offer an integrated vision of migrants as members of the local community. The fundamental argument of this study is the relevance of cities as a frontline defense against the Trump doctrine, with examples that include the diverse urban areas involved, different practices, and various social demands throughout Europe and the United States.

Over the last decade, the dynamics and pressure of migration have had an impact on elections with diverse political options and voting results in municipal, state, and European electoral districts. Immigration is one of the truly significant issues in election campaigns, as it mobilizes voters and is mediatized for propagandistic purposes (

Krzyżanowski et al. 2018). The political response to migration varies at the municipal and national levels. It is a question of legitimacy (who really cares about immigrants and social cohesion?), authority (who is in control of borders or diasporas?), and innovation (what are the best practices for governance?).

On the one hand, central governments have increased restrictive measures against migration. Populist or nationalist political parties have criticized the arrival of immigrants and have developed a discourse regarding identity, social services, and the cost to the public treasury. The discourse on the legality of migrants and their relationship to a multitude of crimes is recurrent among these political representatives and elected officials. On the other hand, a trade-off between migration and social welfare (

Wright 2016) has been proposed, which would please the most nationalistic and conservative electorate. In his State of the Union Address in 2020, Donald Trump made the following statement: “Last year, our brave ICE officers arrested more than 120,000 criminal aliens charged with nearly 10,000 burglaries, 5000 sexual assaults, 45,000 violent assaults, and 2000 murders. Tragically, there are many cities in America where radical politicians have chosen to provide sanctuary for these criminal illegal aliens.” Santiago Abascal, leader of the right-wing Spanish party known as VOX, expresses his opinion regarding the aggressive deportations back to Morocco at the borders of Ceuta and Melilla: “Spain has to send a message to the world that if you want to come and live with us, you have to do it by knocking at the door and respecting our laws, not by jumping fences or fighting with our security forces.” On his Facebook account, Matteo Salvini, who served as Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of the Interior from 2018 to 2019, describes immigration as an illegal mafia business. “

Azzerare l’immigrazione clandestine” (Stop illegal immigration), he says repeatedly. The crimmigration speech is a combination of criminal and immigration law (

Stumpf 2006).

From another perspective, cities have integrated the migrant population based on facts, with different levels of commitment and diverse attitudes. The Mediterranean refugee crisis has accelerated the actions taken by urban areas, who refer to themselves as “refugee cities”, as a way of denouncing the inaction of central governments. Barcelona Mayor Ada Colau speaks of refugee cities as follows: “Despite obstruction by the state, and the ‘incompetence’ of the Popular Party government, the number of people arriving in our city in search of refuge is increasing.” (2018)

In 2016, there were more than 2000 immigrants, 67% more than the previous year… Let us hope that there are thousands, and even hundreds of thousands more, so the world knows that Barcelona will not be resigned to its own competencies, nor to the incompetence of European governments. “#VolemAcollir, més i millor!!” (We welcome people generously, and more effectively). Daniël Termont, president of EUROCITIES and mayor of Ghent, published an open letter to the European Council as follows: “We need a humane response to the situation of migrants in Europe. Cities have to respond quickly and efficiently to the arrival of asylum seekers and refugees. We provide essential services for social inclusion, such as housing, health care, education, language, and orientation courses” (2018).

The urban goal is not the granting of nationality and passports, but the establishment of new procedures that encourage a human rights perspective. The literature describes the actions of sanctuary cities as “policies and practices that generally serve the purpose of accommodating illegal migrants and refugees in urban communities” (

Bauder 2016, p. 174). Another appropriate designation is municipal activism, defined as “actions taken to promote access to services for irregular migrants in spite of, and to a certain extent by mitigating, national legal and policy frameworks that are restrictive” (

Spencer and Delvino 2019, p. 27).

This is an ambiguous and polysemous concept, the definition of which is more similar to a process than an objective or a pre-determined set of actions. Motomura’s definition is consistent with this broad perspective: “Laws, policies, or other actions by governments and non-governmental actors that have the effect of insulating immigrants from immigration law enforcement. The immigrants who could be insulated are mostly undocumented non-citizens” (

Motomura 2018, p. 437).

Villazor (

2010) defined sanctuary cities as those that adopt policies of non-cooperation in the prosecution of undocumented residents. This approach has challenged the migration governance model from the standpoint of state policy. Garcés and Eitel explain the situation as follows: “Cities that declare themselves to be sanctuary cities want to be present. They want to be able to speak out and take action. They challenge the state monopoly on who can stay, and under what conditions. They do this in their own territory, protecting those whom the state wants to deport, thereby creating a more inclusive concept of ‘us’, and preparing to welcome those who are not legally under their jurisdiction, but who find themselves on their streets. However, these cities also take action internationally, forming urban alliance networks and demanding a larger role for cities in decision-making at the supra-national level.” (

Garcés and Eitel 2019).

The city has become the preferred space for the implementation of migration policies. Consequently, the division between national and local policy is clearly visible. They have accepted responsibility for the arrival of successive waves of immigrants who have come for economic improvement, employment opportunities, or because of war or natural disasters. Migration to cities should not be idealized, since “people do not often mobilize and struggle for abstract or universal ideals” (

Isin 2013, p. 22). Cities respond to the massive arrival of immigrants with specific social policies, regardless of the motivation or cause of displacement (political, economic, etc.). They access public services, use the transport system, find employment, and rent housing. In practice, this means that people need access to basic services (schools, water, medical care), and decent housing. Thus, cities are active participants in implementing migration policies and expanding the activity of what the word ‘global’ means for local governments. These are not isolated, central government decisions, nor the result of multilateral agreements, because migrants usually arrive in specific cities where previous communities have already settled. A similar language, culture, or religious tradition may determine where migrant groups can be found. The city is the environment in which all citizens have quick access to the same services and opportunities. International mobility tends to flow toward and converge on metropolitan areas. According to

Lee (

2017), the population density of cities facilitates finding jobs and securing better housing, as well as access to familiar cultural networks and anonymity. Consequently, “migrants tend to remain in cities once they have arrived in their destination country, and they become an important stimulus to the growth of the urban economy and population. In fact, as many as 92% of immigrants in the United States, 95% in the United Kingdom and Canada, and 99% in Australia live in urban areas” (

WEF 2017, p. 26).

The confrontation between national governments and cities has been aggravated by the incorporation of the populist narrative (

Bevelander and Wodak 2019;

Waisbord 2018), which converts migrants into refugees, illegal aliens, or asylum seekers, thereby rejecting their essential condition as citizens of a city. Denigrating messages multiply (

Ott 2017), and hostile policies, together with police intervention, are taken to an extreme. On the other hand, cities designated as sanctuaries use friendly language in their institutions and in statements made by municipal representatives. The discourse is built upon specific municipal policies that confer a kind of “enacted citizenship” on migrants regardless of national policies or passports. In a city, the inhabitants are citizens regardless of their legal status. They are considered as such by their basic right to citizenship, a concept that is consistent with the idea of the “right to the city” (

Lefebvre 1968).

The status of a sanctuary city is the political result of independent urban participation in the implementation of migration policies. The use of public transport, access to basic electricity and water services, political participation, and environmental quality are urban rights of a city’s inhabitants. Afterward, these rights are extended to identity policies.

In this context, defined by Trump-style political practices, this study attempts to analyze the current situation of sanctuary cities at a moment when populism and nationalism are on the rise. Some of these issues include pressure from state policy on municipal actions, the financial stifling of such initiatives, or the increasing blame being placed on migrants as a source of populist rhetoric.

For this reason, the following research question has been posed: What is the role of cities in migration policies in the age of Trump? The President announced the “launch of a nationwide crackdown on sanctuary cities” (

Abramson 2017), pressuring local governments with the threat of withholding federal funds. And in Europe? How has the phenomenon of sanctuary cities evolved in the face of an increase in populist governments?

This article is structured as follows. Firstly, it reviews the tension involved in national policies that try to restrict immigration. The Trump administration is the recurrent example of this type of policy, which is populist and nationalistic in nature, although Italy and the United Kingdom have also witnessed a proliferation of statements and actions that have created a hostile environment toward immigration policy. Faced with hostility, cities act defiantly in expanding the “right to the city” to new migrant groups. The article also explains how cities resist the temptation to engage in populist discourse through social policies that deal with real problems that are close to home. It also includes a critical review of the temptation to be labeled as a sanctuary, or place of refuge, without having a real effect on citizenship. Next, the three central concepts in identifying sanctuary cities in the Trump era are described, which are as follows: (1) The implementation of local public policy focused on managing the needs of immigrants through public services, as well as the renouncement of penal or punitive actions through the use of police tactics that jeopardize peaceful community coexistence; (2) explicit disagreement with foreign policy, especially when this entails the expulsion of one’s neighbors (this point has been impaired by Trump’s threats to reduce local financial support); and (3) the social demand for acceptance and the evolution of the digital diaspora. The study concludes with a review of the challenges facing sanctuary cities.

3. Results: Sanctuary Cities in the Trump Era

San Francisco calls itself a sanctuary city, considering the following to be attributes of such a status in its Admin. Code (12I.1):

“Respect[], uphold[], and value[] equal protection and equal treatment for all of [its] residents, regardless of immigration status. Fostering a relationship of trust, respect, and open communication between City employees and City residents is essential to the City’s core mission of ensuring public health, safety, and welfare, and serving the needs of everyone in the community, including immigrants.”

The sanctuary city has three characteristics of its own that make it a highly relevant phenomenon for resistance to populism and Trump-style politics. These are as follows (

Artero 2019):

- (1)

Implementation of the consequences of migration policy through local governments and institutions;

- (2)

Disagreement with the state’s foreign policy;

- (3)

Social demand.

The requisites for becoming a sanctuary city begin with the municipal legislative body, which passes laws or ordinances according to local competencies. Since 1985, San Francisco has become a sanctuary city after passing the City of Refuge resolution and the City of Refuge ordinance (1989). Their self-designation avoids a legal definition with regard to the question of nationality or an irregular situation, but describes a broad policy approach toward immigrants, asylum seekers, and refugees (

O’Brien et al. 2019;

Bauder 2016), promoting a “culture of hospitality” (

Squire and Bagelman 2012). This is a practice as well as a public opinion debate, not a regulatory response nor a specific set of goals. The city does not allow immigration policies to be used in investigations involving local law enforcement. The procedures vary from city to city (

Lasch et al. 2018), but they include the denial of entry to local jails by Immigration and Customs Enforcement officials, or not sending fingerprints to Homeland Security. Passing ordinances to forbid cooperation protects the local police and civil services from federal prosecution. Immigration laws do not merit local cooperation because their implementation could disrupt both societal and local services. By taking these actions, the city encourages social services (schooling, medical care, etc.) and reduces the number of immigrants who are not able to access public services. In fact, similarly to Amsterdam, city officials refuse to check the residence status of those who report a crime in police stations (

Delvino 2017). However, the literature lacks unity on this issue. The definition is an adaptive sum of urban aspects (legal, administrative, identity orientation), rather than a closed list of legal items.

There are no specific international agreements among cities, but best practices are widely shared. Cities are the first to receive immigrants who need a practical solution to basic issues of health care, housing, education, social services, and employment. The implementation of a practical solution in conformance with capabilities and the political project is organized at the local level (

Brandt 2018). The degree of autonomy of such decisions is low compared to the level of responsibility cities have for migrants. Even so, more than twenty cities in the United States have a municipal agency dedicated to immigration issues. The study of immigration policy precisely reflects how local policies support decisions with international repercussions. The need to help migrants is based on their de facto status as members of the community (

de Graauw 2014). For municipal issues, San Francisco, Chicago, Los Angeles, and New York have granted city ID cards to immigrants. It is not an alternative to the national ID card, but a tool for providing basic local services (schooling, law enforcement, payment of local taxes, tenancy, etc.). In Barcelona (Spain), the ID card acknowledges the neighborhood where the migrants live as well as their integration into the city by identifying links with regard to family, work, professions, and social aspects. The project does not grant any other qualification regarding nationality or legal processes, but it helps in managing local programs. In terms of social cohesion, the ID card reduces the invisibility of migrants in making local decisions (budget, priorities, and local policing). In Vancouver, the policy entitled “Access to City Services Without Fear” includes public health and emergency services. In Montreal, the Intervention and Protection Unit allows undocumented immigrants to report crimes, job-related injustice, or sexual abuse. The immigration status is quite different from neighborhood status, or the so-called “ius domicili” (right to a domicile), which is available to all residents regardless of whether their status is regular or not (

Kaufmann 2019, p. 443). Irregular immigrants cannot vote, but they are a policy target group. Urban citizenship is not a passport, but it demonstrates residence and affiliation with the local community.

The implementation of migration policies in local institutions adheres to a social justice model that has support at all levels and in all local administrations (

Yukich 2013). Sub-national governments have a responsibility for the welfare of immigrants and the growing number of shanty towns. Local, regional, and federal governments establish immigration proceedings, not only symbolically or by enacting laws. Frequently, implementing immigration solutions may include procedures such as economic development, public safety, community building, diverse employment, non-profit or public school partnerships, and advisory councils (

Brenner 2009).

This is not to say that there is no internal opposition within the municipality or regional government, but rather that international solidarity is not usually an area of confrontation among local leaders. Xenophobic and exclusion-oriented rhetoric is risky, except among the most radical voters. On the contrary, global cities often extend rights to all of their inhabitants regardless of status (legal, illegal, or partially legal) or nationality. Local public services (transport, shelter, and education) do not compete with hard power, but instead reflect a repertory of soft actions. Another issue would be to consider and evaluate the way that initiatives are financed, which is a space where the dissenting voice can indeed gain support.

The lack of cooperation in enforcing federal immigration laws is based on an open rationale. Most sanctuary cities believe that criminal and civil immigration violations can be controlled through local law enforcement. Consequently, federal government authority is not mandatory. If an immigrant population feels that they are viewed suspiciously, they will not access local services, thereby becoming an invisible population in town halls, counties, and even nations. Open schools and access to typical urban spaces (sport centers, religious institutions) build trust and prevent discrimination. In cases of collaboration, such as that of Barcelona or Geneva, local officials work together with NGOs to extend the local status of migrants in order for them to be eligible for regularization. Decisions are made within the context of the particular city in question, as there is no systematic approach or standard model of collaboration (

Strunk and Leitner 2013).

The following aspect of the sanctuary city, or place of refuge, is the most relevant in terms of political economy. Refuge or sanctuary cities disregard federal or state regulations in order to deal with and support immigration, regardless of legal status (

City of Sanctuary 2017). Other initiatives, such as the New Sanctuary Movement or the City of Sanctuary crusade, launched advocacy campaigns after 9/11 and the Patriot Act. In practice, the status of a sanctuary can be found at the city, county, and national levels. The use of power allows for alignment with the authority of state and international organizations, or active dissent in the form of political practice contrary to government guidelines, breaking the unity of action in foreign policy. This internal city discord with the state first appeared in the United States during the Vietnam War. Deserters found protection in the city of Berkeley, strongly rooted in the counter-culture struggle and the “hippy” movement, which displayed activist values of a city narrative outside the elite system of Washington (

Ridgley 2008). Later, in 1983, the Madison city council in Wisconsin passed a law to provide shelter to Central American illegal immigrants seeking asylum, and tried to avoid deportation measures.

Disagreement with the state’s foreign policy, which is the backbone of hard and soft diplomacy, represents a qualitative step forward in the use of city power to transform national migration policy (

Bauder 2016). Local driving forces based on direct assistance challenge the authority and legitimacy of the state in making decisions that will affect the local territory in a practical way. Faced with a model that involves exclusion and control of migratory flows along with the use of barriers that are typical of hard power (passports, border control, consulate policy), the global city undertakes its own foreign policy. Of course, these cities do not act alone. Instead, they are organized in networks that strengthen decisions. The network structure is a real alternative that has power (it represents the direct will of the citizens of the participating cities), and it also has autonomy (local or regional governments, financial capability). The migration issue offers an extensive assortment of these networks (

Bauder 2016), highlighted by the Mayors’ Migration Council. In the USA, the network entitled “Welcoming America’s Welcoming Cities” is an example of how cities share best practices (

Huang and Liu 2018). Created in 2013, the organization now includes as many as 50 cities, among which are Chicago, San Francisco, Washington D.C., and Nashville. The goal is to share policies and initiatives that attend to specific immigration needs. Other cities use self-designation as an “Inclusive City” (McMinville) or a “Human Rights City” (Richmond). In Canada, the City of Toronto carried out the Cities of Migration project. In Europe, Barcelona led the European Network of Cities of Refuge, an inter-municipal space for sharing local services regarding the arrival and reception of immigrants, after it lead the Mayoral Forum on Mobility, Migration, and Development in 2014. The Eurocities initiative serves as an open forum for 140 European cities in order to share best practices in migrant integration.

National immigration policies are facing political resistance from a growing number of cities, which argue that certain immigration laws violate constitutional law. The range of resistance actions varies in each of the four states, including 39 cities and 364 counties, which have adopted pro-immigration policies inspired by sanctuary doctrine. In the USA, approximately three hundred local governments refuse to collaborate with US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). Local civil services, including police departments, are not allowed to collaborate in the implementation of such policies. The Trump administration ordered an intensification of its enforcement efforts, including daily surveillance operations. Surveillance of homes and workplaces has increased, especially in cities where the local police do not cooperate. Thus, between February and April of 2020, 500 additional officers from other units were deployed. The deployment of agents from BORTAC (an elite Border Patrol team) in urban territory has sent a message of tough measures of control and surveillance. The appearance of such tactics has been denounced by the American Civil Liberties Union as a trade-off between collaboration and coercion: “This is transparent retaliation against local governments for refusing to do the administration’s bidding. It will put lives at risk by further militarizing our streets. Local governments should not be punished for focusing on local community needs and using taxpayer money responsibly, and they should not be pressured into helping deport and detain community members” (

ACLU 2020).

The Trump administration threatened to exclude cities from federal funding and increase the authority of Homeland Security to designate a city as a sanctuary jurisdiction. Executive Order 13.768, entitled “Enhancing Public Safety in the Interior of the United States,” declared that “Sanctuary jurisdictions across the United States willfully violate Federal law in an attempt to shield aliens from being removed from the United States. These jurisdictions have caused immeasurable harm to the American people and to the very fabric of our Republic.” If local entities do not help to enforce federal law, they will not receive federal funding. The amounts in question are not high. For example, there are those of the Edward Byrne Memorial Justice Grant Program (Department of Justice). The State of California is being asked for $10.4 million; the City of Chicago and Cook County, $2.3 million; Philadelphia, $1.7 million; and New York City, $4.3 million. These are small amounts for the respective city budgets, but they are a direct attack on the independent judgement of cities. In addition to this fund, Global Entry and several other Trusted Traveler Programs for all New York state residents have been suspended.

The city of San Francisco and Santa Clara County became the first city and county to file a lawsuit against the constitutionality of the Executive Order as an abuse of federal power. San Francisco estimated a loss of about $1 billion in federal funding, while Santa Clara County calculated approximately $1.7 billion in losses. As argued by San Francisco’s representatives, forcing the city and the county to cooperate in the enforcement of immigration laws by arbitrarily coercing state and local officials would threaten public safety, as it would diminish the trust between local authorities and immigrants in their daily contact, an example of which is reporting crimes or serving as witnesses. Other cities such as Seattle and Richmond have filed similar lawsuits as well.

The key point here is that the US federal system exerts power when faced with protest and dissent, including opposition to national policies. Blocking Trump’s initiatives in court means that constitutional authority is not hierarchical, but rather an example of multi-governance according to rights and regulations. The judicial order in the case of San Francisco vs. Trump was a victory for American cities because opposition to federal administration is now more protected. Moreover, the decision may encourage local immigration policies similar to those of San Francisco rather than those of the Trump administration.

Despite the court decision, the response by the Justice Department has not changed. An intensification of judicial processes is on the rise, and inspectors have been sent to review the extent of collaboration with federal police. More lawsuits have been filed against both local and federal institutions. The Justice Department sued the Governor and Attorney General of California for interfering with the performance of federal immigration authorities. Similarly, the Justice Department also sued the Governor and Attorney General of New Jersey for prohibiting the sharing of information about the immigration status of detainees. The dynamics of judicial and economic persecution represent a punishment for sanctuary cities and other political institutions that do not agree with the immigration policies of the Trump administration. In his State of the Union address in 2020, President Trump called on Congress to pass a new law establishing civil liability for sanctuary cities.

Social demand is a response to campaigns organized by social movements in favor of welcoming immigrants if there is local interest involved.

Mayer (

2017) refers to this phenomenon as an outgrowth of the hospitality culture through a social rather than political structure. However, social demand has an impact on specific responsibilities at the local level. Moreover, the professionalization of hospitality ends up affecting municipal services, or being moved to that department, which is run by civil servants rather than volunteers. Providing social services and assistance has a financial cost, even if the cost only involves coordinating and organizing the initiatives. Irregularity, nationality, and illegality are categories in state policies, but they are not relevant instruments for defining city policy (

Bauder and Gonzalez Dayana 2018). City policy may express a desire to open the city to diversity and develop inclusive guidelines, which becomes urban policy in any case. It is the citizens who create the slogans and put pressure on local institutions to promote a welcoming culture through action networks. Local voices can create national and international cases. Toronto’s program known as DADT (Don’t Ask Don’t Tell) launched an advocacy campaign in 2004 that included road shows in Germany and Switzerland to promote the enactment of sanctuary ordinances by the City Council, which was carried out in 2013. The Barcelona City Council promoted the City of Refuge initiative and established the European Network of Refuge Cities, offering an approach that was different from national asylum policies.

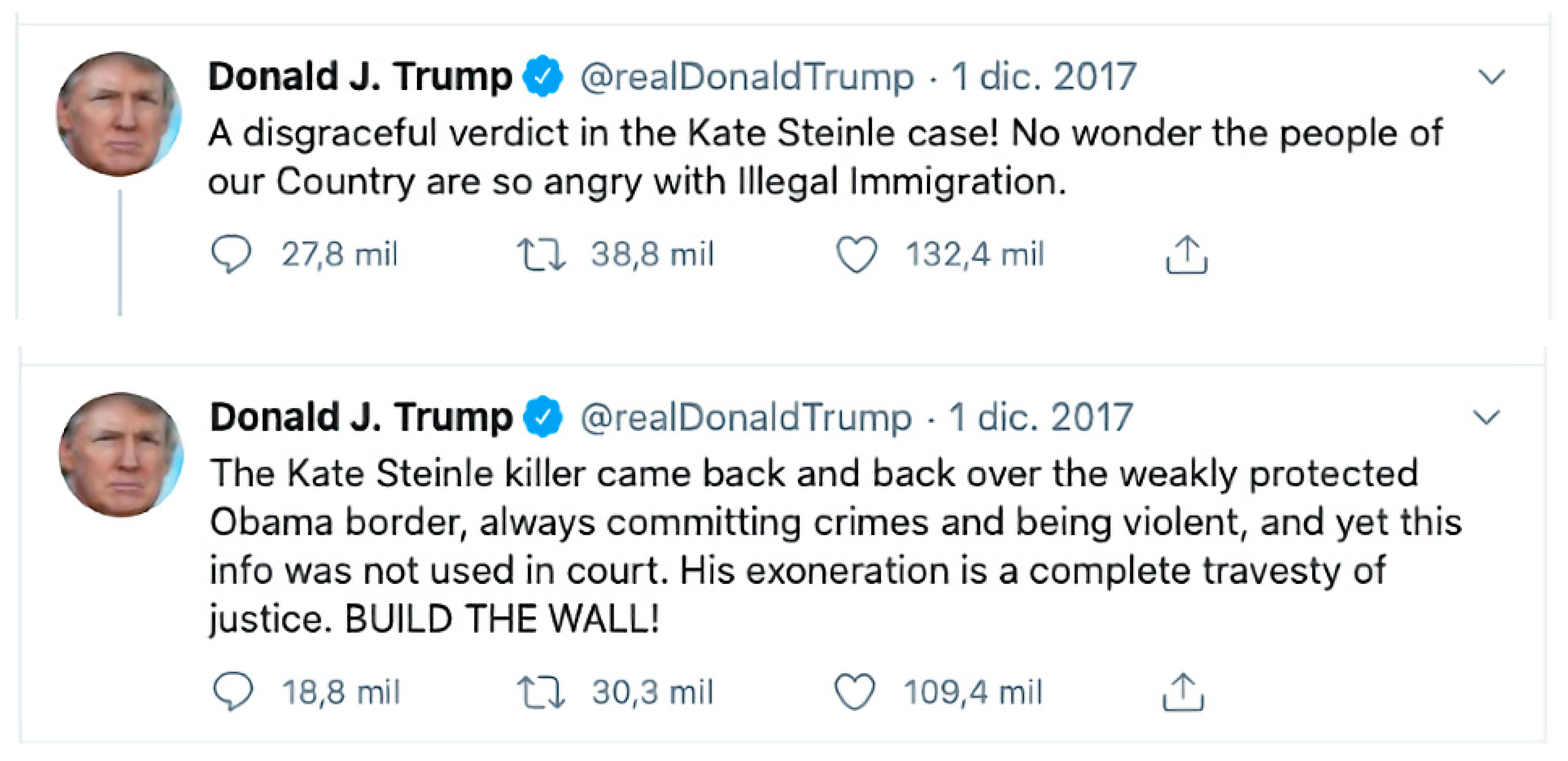

Pro-sanctuary idealism has spread through social media and digital diasporas. The spatial turn has been reflected online through hashtags and online campaigning. Fox News and right-wing advocacy groups run campaigns against sanctuary policies by exploiting isolated cases of crime, protests, and riots. In fact, “Breitbart News was a highly influential source of news coverage on sanctuary cities within the United States” (

McBeth and Lybecker 2018, p. 876). The agenda-setting choice “that was achieved betrays the depth of the association between immigrants and crime… This association has been building up for years—the crimmigration association era continued to solidify the idea, but did not create it. Moreover, this association is all the more troubling because of its detachment from reality” (

Lasch 2016, p. 187). “The American who is ‘white and civilized’ is in line with Donald Trump’s Twitter activity and the rise of the ‘crimmigration’ enforcement regime” (

Lasch et al. 2018).

Sanctuary cities constitute a two-level soft power instrument. At the level of authority, citizen movements are involved in the debate on foreign policy at their own level of activity, which is local policy. Pressure and campaigning prompt local institutions to take a course of action that is distinct from that of federal entities. In many European cities, signs with a slogan that reads “Refugees Welcome” have been hung with clear animosity toward European and national foreign policy. In terms of legitimacy, the care of immigrants is an active measure of justice that does not attack the foundations of sovereignty. Solidarity in the form of reception and educational campaigns allows local representatives to participate within their own level of authority in public deliberations on foreign policy.

In the case of San Francisco, social demand requires resources to be devoted to local priorities, given the government’s autonomy. The local agenda for immigration policy is not in line with Trump’s policy. Consequently, the local body gives priority to city ordinances, including health and safety. Rotterdam offered basic health coverage, including vaccine packages, for practical reasons. The withdrawal of funding may cause considerable harm to this political project, as crime is lower in sanctuary cities compared to non-sanctuary cities, so the benefit in terms of social progress will be higher (

Wong 2017;

Lyons et al. 2013). However, actions taken by sanctuary cities are not generally accepted. “Sanctuary city procedures and the relations between local and federal law enforcement is an area of legitimate policy disagreement. But the current rhetoric opposing sanctuary cities reflects political opportunism and fearmongering rather than reasoned argument about the merits of sanctuary city policies (

Johnson 2019, p. 613)”.

4. Conclusions

Sanctuary cities develop public policies that integrate basic domains (housing, schools, medical care) with symbolic decisions, such as self-labeling and the promotion of self-recognition diasporas. City networks are common ways to share best practices and to identify implementation processes. There is no standard definition of a sanctuary city, as it seems to be more of an ongoing process rather than a closed regimen. From asylum seekers to domestic workers, the migration trend will continue, and cities will increase their responses under different labels. Sanctuary, solidarity, refuge, or city of human rights will be on the international agenda. As the urban migration phenomenon is expected to continue in the coming years, cities are now organizing a police response regardless of the sovereignty issue. The continued federal policy of exerting pressure undermines the autonomy of cities in carrying out their political and budgetary decisions. A city is inhabited by neighbors who consume resources. If a migrant is living in a city and accessing local public services and facilities, being in possession of a passport, or legal status, is not an issue. For this reason, pressure from the Trump administration is unprecedented in terms of freedom of initiative in matters of public policy. Judicial persecution, though irrelevant in budgetary terms, is retrogressive in the design and execution of public policy. The US legal scope and federal pressure cannot be exported to Spain, Canada, the United Kingdom, or Italy, where migration policy is established as part of national policy. However, cities such as Barcelona, Amsterdam, The Hague, and Toronto are adapting and innovating their own sanctuary practices. All four cities are good examples of the softening of migration laws to the benefit of proposals for adaptation. In populist-style politics, cities have withstood government restrictions and hostility to a great extent. There is no harassment through financial means, which has allowed cities to continue maintaining certain immigration policies of their own.

Trump’s aggressive speech may politicize migration decisions even more. Consequently, policymakers, NGOs, and voters will undoubtedly express their social demands according to the local context. Governing a city in the face of federal pressure will require more united voices in implementing public policies for the migration phenomenon. According to the analysis of this study, the correlation between sanctuary policy and city safety is one of the keys in developing local policies for migrant adaptation. Instead of crimmigration, the ID card system represents a practical feature in identity formation, as it makes the city accessible to migrants. Moreover, religious centers, sports camps, and libraries are city spaces connected to everyday life.

Thirdly, the role of mayors in shaping the migration media coverage bears mentioning. The role of a mayor as a spokesperson for an electoral trend against harassment is relevant because they publish and distribute arguments against populism and immigration restriction. Moreover, President Trump makes the difference on this point. The use of Twitter and the continuous reference to Fox News benefits his crimmigration comments. The challenge for sanctuary city mayors is to create an alternative narrative that avoids city marketing culture.

In conclusion, sanctuary cities have proliferated during the Trump era as a reliable alternative to the hostile environment that populism has ignited against migration policies. They certainly merit the name of Resistance Cities when confronted with the political retrogression of Trump-style politics in both the United States and Europe.