Abstract

This article aims to present some of the initial work of developing a social science grounded game theory—as a clear alternative to classical game theory. Two distinct independent initiatives in Sociology are presented: One, a systems approach, social systems game theory (SGT), and the other, Erving Goffman’s interactionist approach (IGT). These approaches are presented and contrasted with classical theory. They focus on the social rules, norms, roles, role relationships, and institutional arrangements, which structure and regulate human behavior. While strategic judgment and instrumental rationality play an important part in the sociological approaches, they are not a universal or dominant modality of social action determination. Rule following is considered, generally speaking, more characteristic and more general. Sociological approaches, such as those outlined in this article provide a language and conceptual tools to more adequately and effectively than the classical theory describe, model, and analyze the diversity and complexity of human interaction conditions and processes: (1) complex cognitive rule based models of the interaction situation with which actors understand and analyze their situations; (2) value complex(es) with which actors operate, often with multiple values and norms applying in interaction situations; (3) action repertoires (rule complexes) with simple and complex action alternatives—plans, programs, established (sometimes highly elaborated) algorithms, and rituals; (4) a rule complex of action determination modalities for actors to generate and/or select actions in game situations; three action modalities are considered here; each modality consists of one or more procedures or algorithms for action determination: (I) following or implementing a rule or rule complex, norm, role, ritual, or social relation; (II) selecting or choosing among given or institutionalized alternatives according to a rule or principle; and (III) constructing or adopting one or more alternatives according to a value, guideline, or set of criteria. Such determinations are often carried out collectively. The paper identifies and illustrates in a concluding table several of the key differences between classical theory and the sociological approaches on a number of dimensions relating to human agency; social structure, norms, institutions, and cultural forms; patterns of game interaction and outcomes, the conditions of cooperation and conflict, game restructuring and transformation, and empirical relevance. Sociologically based game theory, such as the contributions outlined in this article suggest a language and conceptual tools to more adequately and effectively than the classical theory describe, model, and analyze the diversity, complexity, and dynamics of human interaction conditions and processes and, therefore, promises greater empirical relevance and scientific power. An Appendix provides an elaboration of SGT, concluding that one of SGT’s major contributions is the rule based conceptualization of games as socially embedded with agents in social roles and role relationships and subject to cognitive-normative and agential regulation. SGT rules and rule complexes are based on contemporary developments relating to granular computing and Artificial Intelligence in general.

1. Introduction

Game theory in its several variants can be viewed as an important contribution to multi-agent modeling, with widespread applications in economics and the other social sciences as well as in engineering, management, and biology. This paper presents briefly classical game theory together with two distinct approaches to socializing—extending—classical game theory: One, a systems approach, social systems game theory (SGT), and the other, Erving Goffman’s interactionist approach (IGT). After a short presentation of classical game theory (Section 2), Goffman’s IGT is presented, followed by a presentation of SGT (both in Section 3). In Section 4, these approaches are compared and contrasted with the classical theory. The two sociological theories take up such issues as communication, negotiation, solidarity based cooperation, deception and fabrication, and much else of social-psychological and sociological significance which were all-too-neglected or ignored by classical game theory (although some of these issues have been addressed in later work (such as that of Thomas Schelling (1960); Colman (2003); Elster (1989); Gintis (2009, 2010); Grossi et al. (2012); among others). However, these issues did not (and still do not) fit naturally into the language and conceptualization of classical theory. On another level, SGT and IGT reject assumptions of super-rationality and one-dimensional utility and recognize the extraordinary knowledgeability of human agents about their institutions, roles, and norms and other rules; they recognize also their mixed-motive and multi-value orientations. Section 5 provides a table comparing and contrasting on a number of key dimensions, SGT and IGT, on the one hand, and classical game theory, on the other hand. The dimensions relate to human agency, social structure, norms and other rules, and patterns of game interaction and outcomes as well as such concerns as trust, conditions of cooperation and conflict, game restructuring and transformation, and empirical relevance, etc. In Appendix A, more formal elaborated features of SGT are presented. Social science inspired game theory, such as the contributions outlined in this article suggest a language and conceptual tools to more adequately and effectively than the classical theory describe, model, and analyze the diversity and complexity of human interaction conditions and processes; it promises, therefore, greater empirical relevance, as we argue and illustrate in this article.

2. Classical Game Theory

Game theory is oriented to modelling strategic interactions between two or more players in a situation defined by fixed rules, and given action alternatives and outcomes (Harsanyi and Selten 1972, 1988; Luce and Raiffa 1957; Nash 1950, 1951, 1953; von Neumann and Morgenstern 1944). The players are interdependent in their actions and the outcomes. The theory and its numerous derivatives are relatively widespread in the social sciences and also in engineering and management. It is highly institutionalized—with very substantial funding supporting courses/educational programs, textbooks, journals, research programs, policy applications, etc.

A few terms and conceptions commonly used in game theory are as follows:

(1) Game: A game consists of a set of players (decision makers) who are governed by a set of rules or constraints and whose actions and action outcomes are interdependent. Otherwise, games and their players are socio-culturally and institutionally context free.

(2) Players: Strategic decision makers within the context of the game. Each player is assumed to be an anomic, self-interested egoist who at the same time acts as a strategist, taking into account how other(s) might respond to her and whether or not her own choice of action is the “best response” to others’ expected actions.

They are presumed to be universal super-rational, anomic agents (that is, without social ties) who implicitly or explicitly lack morality (as well as creative and transformative capabilities).

In other words, each player is not only alien to others with whom she interacts but a supreme egoist who tries to gain the most or to make the best choice for herself, showing no morality, concern or empathy for others ine the game situation. In other words, she merely searches in her action space that particular action which is the best response for herself to “the best choices of other(s)”.

(3) Super-capabilities of individual cognition, judgment, and choice are assumed according to fixed axioms of rationality. Consistency and coherence are taken to be universal.

(4) Perfect or minimally imperfect information is assumed for game players about the game, its players, their options, payoffs, and preference structures or utilities (that is, crisp information, strategies, decisions).

(5) Game structure is assumed fixed or given. Game transformation—or transformation of any kind including that of the material and socio-cultural context—was never conceived in classical game theory. Consistent with the notion of fixed or given game structures, classical games are “closed” (in principle, not transformable except by the game theorist herself; in time, game theorizing developed concepts and illustrations of dynamic and evolutionary games (Axelrod 1984; Gintis 2004; Hardin 1995; Hofbauer and Sigmund 1988; Skyrms 1996; Smith 1982; among others).

(6) Strategy: Each actor has a set of possible instrumental strategies. Each strategy is a complete plan of action a player may take, given the set of circumstances that obtain in the game situation. Typically, actors have multiple strategies, among which they make choices in pursuit of net gains or increased utility. (Many types of action such as ritual and ceremonial action do not make sense in a purely rational instrumental perspective. Moreover, innovative and creative activities are not part of classical repertoires).

(7) Payoff: There is a mapping from a set of strategies to a set of payoffs, one such mapping for each player. The payoff a player receives from a particular outcome can be in any quantifiable form, whether concrete dollars or abstract utility.

(8) Utility function or preference ordering over outcomes (payoffs) is given and exogenous to the game—it is usually seen as one-dimensional in character.

(9) Singular decision modality: As in economics generally, there is the assumption of rationality. Instrumental rationality or “rational choice”—maximization of payoffs or expected utility—is the universal choice and action principle. The “maximum expected utility principle” states that a rational agent should choose an action that maximizes her expected utility in her current action/interaction situation (see Appendix A). The multiple actors (two or more) all follow this principle, consistent with the assumption of game symmetry. Each actor is assumed motivated to be an instrumental rational strategist, taking into account the interdependency of her actions with those of others, and judging how other(s) are likely to respond to her and whether or not her own choice or action is the “best response” to others’ expected actions (see below).

(10) Equilibrium. The point in a game where both players have made their decisions and an outcome is reached. An equilibrium is the “solution” to the game, for instance, the Nash equilibrium in non-cooperative games—without communication or binding agreement. The “Nash Equilibrium (NE)” is the outcome of a game where no player has an incentive to unilaterally deviate from his chosen strategy after considering opponents’ choices. A set of strategies form a NE if, for player i, the strategy chosen by i maximises i’s payoff, given the strategies chosen by all other players in the game.

We take up later in the discussion empirical and conceptual considerations, pointing out several of the limitations of and challenges to classical game theory and the many openings for sociological game theorizing as an alternative (also, see Table 1).

Table 1.

Classical and Sociological Game Theories Compared and Contrasted.

3. Sociological Theories of Games and Interaction

The sociological approaches to game theorizing—and formulating an alternative—are empirically grounded as well as informed by established social science knowledge.1 As would be expected, they emphasize the importance of taking into account and analyzing such factors as the social context, and the social relationships, roles, and norms of the players or “actors”—which contribute to defining many if not most of the “rules of the game.” In this perspective, games or interaction situations are “socially contextualized or embedded” (Burns et al. 1985; Granovetter 1985). We briefly outline the two sociological approaches, IGT and SGT.

3.1. Goffman’s Interaction Game Theory (IGT)

Goffman’s interactionist approach (Goffman 1961, 1969; Manning 1992) to extending classical game theory derives, in part, from his knowledge of the sociological theory of symbolic interactionism (Blumer 1937).2

(1) Goffman focuses as does SGT on multi-agent interaction situations where there are interdependencies among two or more agents.

(2) He makes use of sociological concepts such as rules, norms, roles, and social relationships in his analyses as does SGT.

(3) IGT puts a great deal of stress on communication among actors, the categories and symbol systems the actors use, the shared framing and definitions of their interaction situations.

(4) Goffman applies the concepts of game and strategic action to a variety of social interaction situations, for instance, impression management games; in such games, actors try to manipulate the impressions they give in interactions so as to influence others’ orientations and judgments of them.

(5) As would be expected from the author of “the presentation of self in everyday life” (Goffman 1959), he emphasizes the forms and strategies of self-expression in interaction situations.

(6) IGT considers how actors combine ritual and strategic modalities, often drawing on rich culturally established traditions, in the process producing complex patterns of interaction (see Zelizer 2012).

(7) Especially important for Goffman was the empirical investigation and analysis of concealment, fabrication, and seduction in games, for instance, in his consideration of the “con-artist” (confidence man) who tricks others to put up money in a scheme which enables the con-artist to steal the money using deceptive methods.

(8) Of particular importance in Goffman’s work is his attention to, and elaboration of, social psychological aspects of game “players”: their technical knowledge and competences, their gamemanship, their capabilities of assessing situations, other agents, and themselves. Drawing on psychology and social psychology, Goffman distinguished such aspects or characteristics of players as gameworthiness (ability to set aside personal feelings and emotions—“impulsive inclinations”—in assembling the situation and in following a course of action). The varying capabilities of actors to assess their own situations as well as assess the other player(s)’ situation; the capability of assessing the expressions and communications of others, their trustworthiness. Such capabilities, Goffman suggests, are important to game performance and success.

(9) IGT, like SGT, recognizes the role of nature and/or third parties in structuring games and regulating patterns of interactions and outcomes.

3.2. Social Systems Game Theory (SGT)

In SGT games consist of (1) participating, mutually aware agents whose actions are interdependent; (2) the SGT agents/participants are typically role and normatively directed and constrained; they are, in part, strategic, that is, “rational” but with limited (“bounded”) rationality at the same time that they are innovative and creative as well as transformative beings. (3) rule regimes (cultural and institutional systems) structure and regulate role relationships, games, and interactions; in other words, games are embedded in social institutions and cultural formations (social rule systems as well as material conditions (Burns and Flam 1987; Burns and Hall 2012). and (4) resources (technologies, material conditions) play a substantial part in the actions and interactions. The SGT formulation derives from Actors-Systems-Dynamics, a meta-theory which provides a language, modelling and analytic tools on which investigations of rule systems, cultural formations, institutional arrangements, and social interaction patterns are based (Baumgartner et al. 2014; Burns 2008; Burns et al. 1985; Burns and Flam 1987; Burns and Meeker 1974).

SGT in a nutshell:

(1) SGT theory is applied to multi-agent interaction situations where there are interdependencies among two or more agents (as in classical game theory and IGT) (see footnote 1).

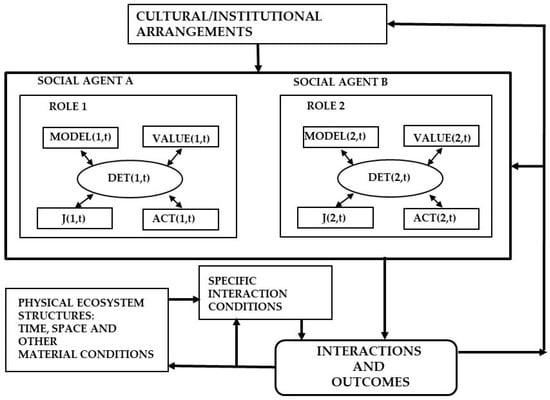

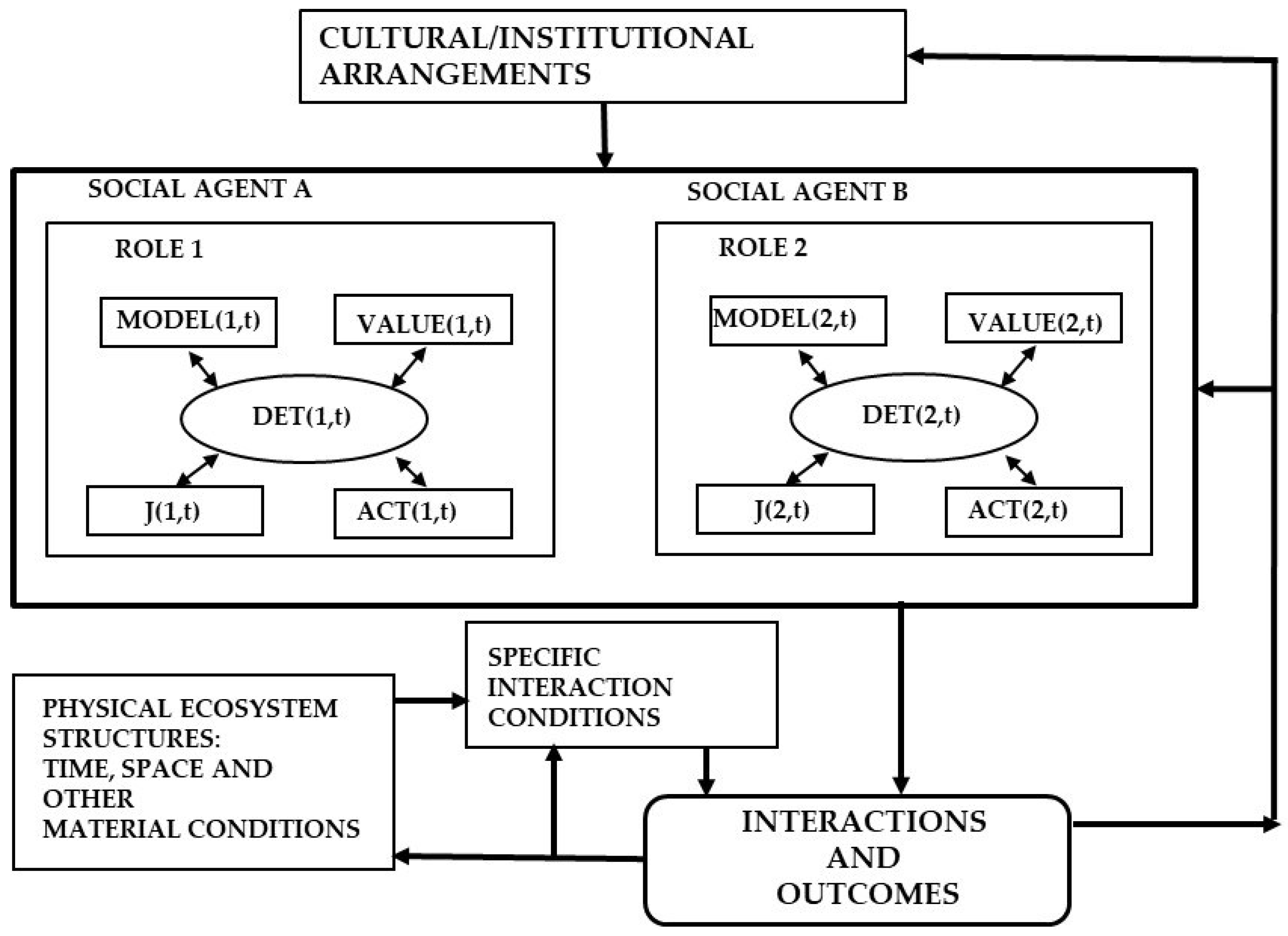

(2) A SGT game consists of a set of actors in diverse roles who interact in complex socio-cultural and psychological contexts, subject to particular rule regimes (institutions, cultural formations (see Figure A1)) as well as material and technological conditions. That is, games are socially embedded—normative, relational, and institutional contexts are identified and taken into account in their influence on interaction conditions and the participating actors’ frames, perceptions, judgments, and actions. Interaction and group behaviour, its outputs and consequences are patterned in large part through actors performing their roles and adhering to norms; at the same time, they may make strategic choices, and take strategic actions to better achieve a goal or to realize a role or norm.

(3) SGT provides then a cultural/institutional basis for the conceptualization and analysis of games in their social context, showing precisely the ways in which social norms and rule complexes of social relationships, values, institutions, and social relationships come into play in shaping and regulating game agents and their interactions. It stresses action and interaction based on social rule systems—typically implementing norms, roles, and institutional arrangements.3

(4) SGT games may be symmetrical or asymmetrical—this is an empirical question relating to the social structure and population of agents involved in the games. For instance, status and power differences correspond to asymmetries in game and rule architecture.

(5) Bounded capabilities of actors. The SGT approach to game theorizing rejects assumptions of super-rationality and maximization of one-dimensional utility. Instead, individuals as well as collective agents are seen as having multiple value and bounded capabilities of cognition, judgment, and choice. Contradiction, incoherence and dilemmas, arise because of multiple values and norms which are not always assumed compatible in any given game situation. Degrees of consistency and coherence are socially structured and regulated, that is, there is an empirical issue not an axiomatic one.

(6) Rules governing communicative actions. Communication conditions and forms are specified by the rules defining action opportunities and repertoires in any given game situation. In whatever ways the norms and institutional arrangements are established and maintained, the SGT approach provides a language and analytic tools to describe and analyze a wide variety of communication situations distinguishable by their particular norms and institutional arrangements. SGT readily articulates the rules of “communication among players” and the making of binding agreements—which are the bases of what are referred to in classical game theory as “cooperative games.” But there is much greater variety and complexity in human communicative activity than the simple but limited distinction (at least seen from a social rule system perspective) between cooperative and non-cooperative games would suggest.

(7) Extraordinary social knowledge. While SGT readily and systematically incorporates the principle that human actors have bounded factual knowledge and computational capability, it emphasizes their extraordinary socio-cultural and institutional knowledge and competencies: in particular, their knowledge of diverse cultural forms and institutions such as in those of family, market, government, business or work organization, hospitals, and educational systems, among others, knowledge which they bring to bear in framing and engaging in their role relationships and game interactions.

(8) Evaluative judgment of actions and outcomes. Strategies and outcomes have properties which are evaluated according to relevant norms and values (the value complex) of actors’ roles as well as the particular game situation itself. Typically, some or many properties of interactions and outcomes are unknown—unanticipated and unintended outcomes of actions and interactions are an inherent part of the SGT conceptualization.

(9) Game closure and openness. SGT distinguishes between open and closed games. The rule regime of a closed game is fixed. In open games, actors have the capacity (“meta-power” (Burns and Hall 2012) to structure, restructure, and transform game components such as the role components or the general “rules of the game”. Even external agents (“third parties”) may have such power to structure and transform games (hence, “the prisoners’ dilemma game has been analysed in SGT as a three-person game” with the district attorney (DA) structuring the 2-person game (Buckley and Burns 1974).4

(10) Role conditions in closed and open games. Each player has one or more roles in a game. In closed games an actor in any given role has a set of available strategies. In open games, she may develop or adopt strategies as the interactions among players evolve. She may change her role(s) or adopt a new role (or roles). In general, actors may to a greater or lesser extent change their strategies or options as well as the rules, roles, norms, players, context, etc.).

(11) Game transformation. Game re-structuring and transformation is conceptualized in SGT through constructive actions of game agents and/or external agents. It is based on the innovative or creative capabilities of game participants. Exogenous agents also engage in shaping and reshaping games. In “open games”, the players may restructure and transform the game, its norms, their roles, and role relationships and, thereby, the conditions of further actions and interactions.

(12) Normative equilibria and solution concepts. SGT re-conceptualizes the notion of “equilibrium” as well as “game solution.” In SGT, games and interaction processes result in the production and manipulation of institutions, social relationships, roles, norms—and these serve, in general, as equilibria—normative equilibria (right actions, distributive justice (Burns et al. 2014)), which is the basis of much social regulation and order. In SGT “solutions” are defined in a particular framework or model of one or more players—or possibly a group or organization. “Solutions” envisioned or proposed by actors operating with different frameworks and interests are likely to be contradictory or incompatible. Under some conditions, however, actors may arrive at “common solutions” or find such “solutions” imposed by external agents, which in both cases are part of the patterning of interaction and game equilibria.

(13) Action determination rule complex: Modalities for determination of action (as a distinct contrasting alternative to maximization of utility which, in any case, is a special case of DET-II modality). The universal motivational factor in SGT is the human drive to realize multiple appropriate rules, norms and values through their actions and interactions in particular contexts. An action determination rule complex DET is utilized by each and every actor to organize the selection and enactment of actions in relation to other agents in any interaction situation (Burns and Roszkowska 2005). The concept of action determination refers here to three analytically distinct bases or modalities on which actors determine what they do: for instance, following a rule or algorithm (which prescribes social actions and interactions), making choices among given alternative actions, and constructing and enacting new actions.5

These modalities are briefly explicated below.6

A. DET-I: This modality entails following or implementing an appropriate or prescribed rule, rule complex, norm, ritual, role, institutional arrangement (with multiple participants), that is, one or more rule complexes or algorithms are implemented. In the activation and effort to realize the rule or rule complex, the performer compares and “matches” the experience or perception of the act with the qualities or details specified by the rule or rule complex (see Appendix A).

Most social action and interaction are routinized, ritualistic; performance or enactment is matched with a specified rule, norm, procedures in a given interaction situation S and game G, with actors i, j, k,…, m. The roles and role relationships as well as general norms and rules are those applying to the particular situation. For instance, two actors, A and B, in a 2-person game have established paired rule complexes to implement, and the interaction is likely to be highly routine, predictable. Even if content changes—within some limits—the interaction is likely to be produced in routine and predictable ways. (Whole production systems operate more or less in this way: organ transplantation model (Machado 1998), hydro-power planning and decision-making model (Burns and Flam 1987); bank-wiring production room (Homans 1950)).

B. DET-II: This modality entails assessing and choosing among established or given multiple courses of action, according to a rule or principle. An agent or group of agents is faced with a “crossroad”, alternative actions, multiple strategies, or modalities of action determination. For instance, the agent is faced with a choice between two or more action alternatives; or a choice has to be made between an action of normative realization or an action promising instrumental gain (possibly illegal). Or the agent chooses between an extreme emotional expression (emotional modality) and an instrumental one (constraining her emotional expression for the purpose of gaining something desirable from another agent such as an employer. Because of a blockage of an established activity, or its failure to do what it is supposed to do, the actor is driven to construct or generate one or more action alternatives. In other words, the agent(s) is (are) engaged in creative and innovative efforts.

Following a rule, procedure or algorithm, the actor selects the alternative from among the possible options. One variant of this entails “matching”—the actor selects the option most similar to a relevant norm or value; in other words, the actor compares the various alternatives to the relevant norm and value complex in the situation, and the degree of similarity is assessed. The actors choose the most similar alternative—or the one that is ranked highest in terms of similarity with the relevant norms and values.

C. DET-III: This modality entails finding or constructing one or more action alternatives in an initial phase, according to a guideline, principle, or set of criteria. Phase 2 entails the decision to approve or accept as well as perform the constructed or derived actions. In case of alternative options, the agent(s) makes an assessment and choice among those alternatives (that is, applies a DET-II modality).

Note that the “action determinations of DET-II and DET-III” are ultimately finalized through DET-I processes of rule following or enactment.

In sum, the action determination concept replaces the more limited notion of “rational decision-making” in classical game theory. It entails, as indicated above, either following or implementing a rule or rule complex such as an algorithm, selecting or choosing among alternatives, and constructing or adopting new rules—such determinations are often realized according to collective specifications and collective performances (see Table A1 in Appendix A).

The sociological approaches of SGT and IGT promise effective description, analysis, and explanation of a wide variety of social interactions and game situations—and specifying as well as explaining interaction patterns and outcomes beyond the capabilities of classical game theory. The sociological toolbox provides a systematic basis to describe, analyze, understand and explain patterns of interaction, their stability and transformation. In some cases, predictions of interaction patterns and outcomes are possible, particularly when institutional arrangements and normative orders are stable; they operate as elaborate social algorithms providing stability, predictability, and the experience of social order among participants. Moreover, interaction contexts and conditions can be distinguished and analysed which are likely to lead to stable patterns of interaction, on the one hand, or to unstable patterns and disorder, on the other hand.

The sociological approaches cover many types of games (in some cases games not ever envisioned or envision-able in classical theory and also, arguably, in its many direct descendants). For instance, SGT researchers have conducted studies of a variety of exchange interactions, conflict and negotiation interactions, organizational relationships such as supervisor-supervisee, and policy games in diverse fields and sectors (Baumgartner et al. 1975, 1977; Buckley et al. 1974; Burns and Flam 1987; Burns 2008; Burns and Roszkowska 2005, 2007). Goffman conducted studies and analyses of gambling casinos, community life, and everyday life interactions: expression-of-self games, games of opposition, games of coordination, negotiation, and contingency, observer-subject games, and interrogation games as well as a variety of games of secrecy, deception and fabrication (Goffman 1969, 1961).

4. Discussion: Applications and Illustrations

This section provides examples and illustrations of the sociological approaches and suggesting contrasts to classical theory. The emphases are on social rules, multiple values, multiple roles, the great variety of games and interaction situations, the patterning of interaction and games as a function of actors’ social relationships and the social context.

4.1. Social Rules and Rule Systems and Their Influence on Behavior

Multiple Norms and Institutional Factors

Norms and norm complexes (rule regimes) are the “bread and butter” materials of much sociological research. It is not surprising that in his work on game theory, Goffman identified a variety of norms operating in any game process. For instance, the norms prior to any game being played as well as those applied in the multiple phases of an interaction process (Goffman 1969, p. 114), for instance: (1) directives (i.e., constraints) to play the game as part of a normative, institutional context as well as to participate in and perform of particular roles in the interaction situation; in other words, participation and role performance in the game interaction situations is expected, even demanded; (2) norms structuring actors choices and payoffs in the interaction situation; (3) norms supporting commitment to actors’ previous moves or promises; (4) norms providing intrinsic payoffs to players, not just the ostensible outcome payoffs. In general, a game or interaction situation is “socially embedded” in, and constrained by, multiple complexes of appropriate rules (Burns et al. 1985; Granovetter 1985). In general, in the perspectives of SGT and IGT, social norms and institutional factors must be an integral part of the description and analysis of game situations and interaction behaviour and provide a reliable basis for explaining and predicting many behavioural patterns (Baumgartner et al. 1975, 1977; Burns and Gomolinska 2000; Burns and Roszkowska 2005). The conceptualizations and analyses in the sociological approaches stress that actors’ group membership and group social relationships play a substantial part in how they act and interact in relation to one another. In general, meaningful other agents and groups influence the thinking, judgment, and behavior of individual players involved in interaction situations and games. Normative and institutional factors are axiomatic in any sociological approach to conceptualizing interaction and game processes. Such factors are largely missing from classical theory, although more recently there have been initiatives to introduce such social factors (see later discussion and footnote 8). In general, in the sociological approaches, social institutional and normative factors are an integral part of the description and analysis of any and all game situations (Baumgartner et al. 1977; Buckley et al. 1974; Burns and Gomolinska 2000; Burns and Meeker 1974).

The sociological approaches to game theory not only distinguishes social rules from other constraints (such as material and technological constraints),7 they broaden and elaborate the conceptions of and distinctions among rules: norms, regulations, institutional arrangements, rituals, traditions, habits of all sorts, among others. Social rules are an underlying code to human behaviour. Goffman emphasized, in particular, ceremonial rules including gestures which guide conduct; often these are viewed by game and rational decision theorists as secondary or even of no significance in their own right (Manning 1992, pp. 53–54). However, the social fabric of sentiments and trust among people is made up of these ceremonial threads (see later discussion about “trust” in social life).

While Sociological approaches readily recognizes informal norms and relations among actors as sources of constraint, it stresses at the same time the importance of formal institutional and legal constraints and regulations on game behaviour Goffman (1969, p. 125) writes: “Under law, a whole range of verbal threats and promises become moves for which actor A can be made liable…. The uttering of self-disbelieved statement under oath is a punishable offense. So also are verbal discourtesies directed at the courts “(or, in many instances, authorities in general). In this way, even words have weights in legally regulated institutional contexts…”.8

4.2. Multiple Values Versus Uni-Dimensional Utility

Actors’ behavior is typically motivated and constrained by multiple values and rationales, motives and factors that go well beyond wanting to maximize the outcome of actions on a single dimension (or “utility”. For instance, they may have to fulfill a specific and complex role such as that of a student, parent, teacher, apprentice, husband, or collaborator in relation to their counterparts. And while engaging in these role based interactions, they may not even try to maximize their own particular payoffs, but instead work to produce or maintain a norm complex, a social relationship or a fragile social order (which may be conceptualized as a particular complex outcome), or they try to accomplish several goals at the same time or in sequence. A world of multiple values results in mixed motive games and decision dilemmas for participants, for instance between instrumental gain, on the one hand, and realization of counter-norm, on the other hand, or conflict between different norms, or between divergent instrumentalities.

In such multiple value contexts, actors experience dilemmas, for instance, between doing the “rational thing” (making particular economic or political gains) versus doing “the right thing” (that is, acting in a normatively appropriate way in the interaction situation) whether that entails applying an appropriate norm or enacting a ritual. In general, human agents are moral beings, much of the time subject to normative and institutional contexts and role relationships—arrangements in large part alien to game theory.

Empathy and Caring for Others

Given that humans are social animals, they display “caring-for-other” behavior, concern with others, putting “others ahead of oneself” (Goffman 1969, p. 92), serving a community, or abstract ideals, such as “the Law,” or “God.” Some or many of their values concern then taking other matters (than themselves) into account and making sacrifices for these others. Certain values belong to a sacred core, grounded in identity, role(s) and role relationships, and institutions to which agents may be strongly committed. Under these conditions, “not everything is negotiable” or “replaceable.” In other words, instrumental, self-interest rationality does not apply universally.

But because of normative dilemmas, “temptations and pressures,” and powerful social and material contextual factors, deviation from institutional arrangements occurs, for instance, in the performance of particular roles and role relationships, as well as norms in general. Under some’ conditions such as revolutionary change, deviation and disruption becomes widespread. There is social disorder; group actors tend to struggle to establish order or possibly a new order.

4.3. Multiple Roles and Shifts in Roles

Goffman pointed out the variety of roles a player can have in many games: a “party”, a “pawn”, “token”, “informant”, “spy”. A “party”, for example can be an individual or group as a player, pawn, token, etc. (Goffman 1969). A given game may be embedded in other games, making for variation in actions and outcomes. Thus, a sexual game with sexually defined roles may be embedded in a business negotiation game with business roles, just as a business game may be embedded in a sexual game.

Asymmetry and Heterogeneity in Roles and Role Relationships

Typically, actors’ roles in a given interaction situation or game differ; they may be differences in positions of status and power; there is also diversity in the role components: value, model, action repertoires, judgment/modality, action determination, etc. (see Appendix A). The actors participating in the same game may operate in different social and psychological contexts—violating one another’s expectations or predictions.

In general, capabilities (endowments, knowledge, cognitive and judgment capabilities) are very unevenly distributed in most groups, organizations, or communities—and all games being played in these contexts will be characterized by varying asymmetries in actor capabilities, knowledge, behavioral inclinations, and performances. This concerns not only expert knowledge and judgment versus the knowledge and judgment capabilities of lay persons. Con-men vis-à-vis their victims have informational, knowledge, and strategic advantages.

4.4. Variety of Interactions and Games

The sociological approaches cover many types of games (in some cases games difficult to envision or to elaborate in classical theory as well as its many direct adaptations). For instance, Goffman conducted studies and analyses of gambling casinos, community life, everyday life interactions such as expression-of-self games, games of coordination and opposition, negotiation games, observer-subject games, and interrogation games as well as a variety of games of secrecy, deception and fabrication (Goffman 1969, 1961). SGT researchers have conducted studies of factory conflict, varieties of exchange interactions, organizational relationships such as that of supervisor-supervisee, and policy games in diverse fields and sectors (Baumgartner et al. 1977, 2014; Burns and Flam 1987; Carson et al. 2009).

4.4.1. Ritual and Ceremonial Types of Interactions

Ritual and ceremonial type of interactions have been particularly emphasized by sociologists; but SGT and IGT in their reformulation of classical game theory recognize and analyze strategic (“rational”) forms of action and interaction combined with rituals and symbolic expressions. In other words, rule following—implementing norms, roles, and institutional arrangements may be combinable with strategic action considerations (but in ways of implementing multiple rules such as “satisficing”, not “maximizing”). Social agents/beings, with their roles, role relationships, obligations as well as rights, and normative context replace “players” as anomic agents, without social relations and normative context (not socially embedded). (See footnote 7 about complex “dances” combining rational/instrumental action together with ritual and normative forms).

The diverse forms of communication and their uses or functions affect game processes and outcomes: for instance, to provide information or to influence the beliefs and judgments of others. Communication also may entail deception and fabrication. Actors “creatively” manipulate information and its interpretation—there are “information wars”, “confidence and other fabrication games.” This is part and parcel of the communication processes among actors. Information exchange and communications among actors may become unintentionally distorted or misunderstood. Research has shown, for instance, that particular technical or complex information provided by physicians to patients is often misunderstood by patients. The impact on behaviour of different degrees of communicative misunderstanding is an empirical question: Actors may or may not use available opportunities in the interaction situation to communicate with one another, as they are assumed able to do in classical “cooperative games” or to follow the rules equally or to the same degree (there are varying degrees of deviance and, in general, these are empirical questions).

4.4.2. Rule and Ritual Based Behavior as Contrasted with Instrumental Rationality

In most interaction situations, actors “follow” rules and rule complexes such as roles, algorithms, and institutional arrangements. People do not universally or even typically try to “maximize” or pursue the best action for a particular value but rather aim for normatively appropriate action or “good enough” or “satisficing” ones. Herbert Simon (1955, 1979) formulated the concept of “bounded rationality”, which is readily and easily incorporated into the social science multi-value and bounded rationality approach to game theory. Even satisficing presumes more rationality than is likely in many social action and interaction situations.

In sum, while instrumental “rationality” has a place in sociological approaches, it shares applicability with other modalities of action driving or motiving human action and interaction. In other words, self-interested rationality, while important in human affairs, plays some role but not in all contexts and at all times. The norms and pressures for such behaviour are role and institutionally dependent.

4.5. The Concepts of Open and Closed Games

As “problem-solvers”, actors/players innovate changing their game structure, its rule regimes, and resources as well as themselves. The action possibilities and outcomes in open games are not all specified or determined—and participants and/or third party or external agents may introduce new options (or eliminate existing options), or change the structure of payoffs or, in general, the “rules of the game” and, thus, the form and character of the game itself. Participants as well, possibly, as external agents may open up or close down a game or game complex. Such processes relate to the high potential creativity of agents. Actors and groups, through their transformative capabilities, adapt and transform rule complexes, taking into account new social, value, or technical considerations as well as excluding older established values and norms. Thus, game actors as well as possibly external actors with sufficient powers can restructure or transform a game, for instance, changing a zero-sum game into a coordination game, or a coordination game into a competitive or zero-sum game. In such terms SGT treated the PDG as a 3-person game with the DA forming the game structure (PD action possibilities of the agents as well as their payoffs) (Buckley and Burns 1974; Buckley et al. 1974). In general, actors—internal and/or external to a given game—may maintain to a greater or lesser extent a closed game.

4.6. Rule-Based Patterns of Interaction and Outcomes

In general, SGT and IGT consider a rich variety of relationships: friendship, mutual hostility, indifferent or neutral relationships, superior-subordinate relationships institutionalized in groups and organizations such as those entailing leadership. Given that games are socio-culturally embedded, one expects diverse patterns in interaction situations since the norms and roles structuring and regulating game behavior vary.

SGT has focused, among other relations, on solidary relationships, which call attention to cooperative norms and norms of distribution (such as forms of “altruism”). Thus, close friends play a prisoners’ dilemma game and more or less readily choose the “cooperative pattern” and avoid the asymmetrical choices as well as the outcome of mutual failure. On the other hand, most status relationships result in asymmetrical patterns of interaction and payoffs. Persons in a status or authority relationship would find appropriate and acceptable the asymmetrical interaction and outcome patterns in the PD or other games with asymmetrical outcomes—in that the patterns are normatively prescribed and expected (of course, disagreements, resentments, and anger may emerge because of differences of interpretation or deviation in one or both actors’ performances) (see Appendix A).

To illustrate how games are played in a social science perspective, consider the role relationship {ROLE(A), ROLE(B)} of actors A and B, respectively, in their positions in an institutionalized relationship in game G(i,t) under conditions t. Such role relationships typically consist of shared as well as interlocked rule complexes. The concept of interlocked complementary rule complexes means that given a particular rule in one actor’s role complex concerning his or her behavior toward the other, there is a corresponding, complementary rule in the other’s actor’s complex. For instance, in the case of a superordinate-subordinate role relationship (Burns and Flam 1987), a subcomplex k(A) in ROLE(A) specifies that actor A has the right to query actor B certain questions, or to make particular evaluations, or to direct B’s actions and to sanction B. In B’s role complex there is a corresponding subcomplexe m(B), obligating B to recognize and respond appropriately to actor A asking questions, making particular evaluations and directing certain actions as well as sanctioning actor B. The couplet (k(A), m(B)) consists of interlocked complementary rule (and role) complexes.

A subordinate B may be ordered by his superior A to come up with an innovation—a new product or process, which A will decide to accept or reject after assessing it, judging whether or not it does what it is supposed to do. This is a particular social order, predictable to a greater or lesser extent based on knowledge of the rule regime structuring and regulating the A-B relationship. Or, consider a similar case but with meritocracy norms prevailing. Rather than A making inquiries, deciding whether to accept or reject B’s innovation, they (and possibly others) engage in a “negotiation” whether or not to accept B’s innovation or either to adapt/modify it or to reject it altogether.

In sum, in a sociologically grounded game theory, actions, interactions, and outcomes are to a great extent a function of the roles and relationships among the actors, which is a particular normatively grounded social order. “Cooperation” and “non-cooperation” are relationally or institutionally contextualized. Actors define, assess, and decide actions and interactions, in large part from the perspective of their particular roles and role relationship. Thus, non-cooperation in a prisoners’ dilemma game (PD) or other interaction situation would in all likelihood be defined and judged as “betrayal” by friends or members of a solidarity group. In general, in groups and organizations with well-defined solidary role relationships, participants in “zero-sum” or PD type situations tend to act cooperatively (and predictably) circumventing the so-called rational pattern of interaction and outcome (mutually destructive) resulting from each choosing the pure self-interest option. On the other hand, in the case of enemies, such behavior would be expected and considered “natural”. In the case of an hierarchical relationship (status/authority), actor A is oriented to and expects to B to behave cooperatively, something B may not want to do, for example carry out a particular loathsome tasks or to make other kinds of sacrifice. Cooperation for the subordinate actor means “compliance” with or acceptance of the superordinate’s directives and the resulting asymmetric outcomes. Even if A’s directive can be understood as a “violation” (in relation to B’s inclinations). Subordinates comply with and make sacrifices for their superiors so that interaction patterns and outcomes are made more or less congruent with their defined hierarchical role relationship, the established social order, and typically they tend to feel good and are recognized and rewarded for their compliance (or, at least, avoid penalties). If there are no options congruent with their role relationship, they are likely to try to restructure or transform the situation. Into one facilitating more congruent patterns; or they try to avoid such interaction situations altogether. In open game situations, actors have opportunities to individually and/or collectively construct new interaction strategies and patterns. In general, actors in solidary relationships will tend to collaborate in solving problems-in-common and work toward mutually satisfying patterns. On the other hand, actors in enmity relations are not likely to collaborate and to work out mutually satisfying patterns under a wide range of circumstances. (See Appendix A for more detailed discussion of these and other interaction patterns).

In making assessments of actions and outcomes, actors do so largely from the perspective of their roles and role relationships; that is, the value complex and action repertoire of the role typically takes precedence over other value complexes. Outcomes may be defined and classified in terms of particular aspects and whether these relate to self, other, or both, or the collective as a whole. This points up the extent to which participants may engage in complex cognitive and modelling activities.

Whyte in his Street Corner Society (Whyte 1943) reports on ways that group lower status members were psychologically and socially driven to lose at bowling when playing with higher status members—regardless of being in some cases unmistakably more capable. These patterns contributed to safeguarding the group’s social structure and ultimately the group’s very existence by consistently acting in ways to maintain the particular social relationships and the group social order. Established status ritual and discourses typically play an important part in such social structuring.

Additionally, social actors with solidarity relationships such as, for example, friendship, as well as for those involving status or authority hierarchies as in the example above from Street Corner Society tend to purposefully avoid situations involving conflicts such as zero-sum situations because those outcomes could entail unacceptable results for self and/or others as well as the group as a whole.

In superordinate-subordinate interactions, we find, in general, the use of multiple rituals: Superordinates generate ritual displays to mark their higher status vis-a-vis subordinates: they carry themselves straight and exude confidence, project high energy without appearing nervous or anxious (they project “coolness”). Subordinates utilize established status interaction rituals to show their awareness of their subordinate position; these rituals express deference and the apparent acceptance of the status quo; at the same time they mayuse deception to conceal feelings of unfairness and humiliation.

When a subordinate commits a faux pau—for instance, overstepping herself vis-à-vis a superior—there are rituals of apology and reemphasis of subordination (for instance, “I’m sorry, I am having my period” or “I am on medication” or there’s been a “death in my family.” On the other hand, if a superior gets carried away and behaves improperly/unacceptably (especially) in a democratic society, they may apologize as well. These rituals of partial apology may be similar to those of a subordinate in relation to her superior, righting a wrong and restoring proper social order again (that is, normative equilibrium).

However, in democratic societies, where equality is a powerful principle, everyone is embarrassed when a subordinate shows excessive obsequiousness. So, the expression of subordination need to be “sufficient enough” to re-assure superiors and to properly maintain the hierarchical order. In these “presentations of self” (communicative acts, constructing gender in the case above, or status difference in a workplace hierarchy) we find identity scripts or algorithms about performing” properly and effectively. Mistakes may be corrected; or, failure at accomplishing this may lead to rupture of the relationship. Maintenance of superordination-subordination in a democratic context requires a delicate balancing, a social skill not necessary in an unabashed authoritarian culture.

This case helps us see how much complexity is involved in many forms of interaction which classical game theory lacks the language and the conceptual tools to effectively describe and analyze.9

4.7. Cooperation, Trust

Trust in social relationships and social institutions has been investigated and analysed in both SGT and IGT. SGT focused on trust in banking and financial situations, established and maintained through particular policies and institutional arrangements to operate instrumentally and ritualistically to reinforce judgments of trust in particular systems, for instance, concerning trust in money or financial systems (Burns and DeVille 2003; Burns and Gomolinska 2001). Goffman (1969, pp. 126ff), on the other hand, focused particularly on situations of interpersonal trust and the role of interpersonal rituals that are utilized in establishing and maintaining trust. He writes (Goffman 1969, p. 130), “In the last analysis, we cannot build another into our plans unless we can rely on him to give his work and keep it and to exude valid expression…. And such trust is based on a social fabric of ceremonial thread. Only through an ‘acceptance’ of the communication of the other (one another) is maximum coordination and collaboration possible, and hence a maximally effective effort”—acting as two members of the same team, or having a common project.

5. Key Points and Conclusions

We have outlined in this article two overlapping sociological initiatives to develop and extend game theory—with an emphasis on social contexts, rules including norms and institutional arrangements, a wide repertoire of actions including diverse forms of cooperation and conflict, communication possibilities, the making of binding agreements, and strategic as well as ritualistic forms of action and interaction. Classical game theory entails a substantially different paradigm (see Table 1).

Among the points we have tried to articulate here, we would like to emphasize the following:

(1) Classical game theory is widespread in the social sciences and also in engineering and management. It is highly institutionalized—with very substantial funding supporting research programs, courses, textbooks, journals, policy applications, etc. Yet, at the same time, it is widely recognized that it is not a genuine empirically based social science theory; it fails to make use of—and to a great extent lacks the language and conceptualizing capacity to make substantial use of—the considerable knowledge available in psychology, social psychology, political science, sociology, anthropology, history, etc. And, therefore, it is unable to adequately describe and analyze systematically the extraordinary variety of human social relations and interaction situations or to consider the rich normative and moral aspects, which are central in all social life. These subjects are given more substantial and proper attention in the sociological approaches grounded in rule based behavior, institutions, and cultural formations.

The limitations of the classical theory are numerous:

(A) Empirical irrelevance. One of the sustained, major criticisms of classical game theory has been its limited empirical irrelevance, the inability to relate it to much of real social life phenomena (Burns 1994, 1990; DiCicco-Bloom and Gibson 2010; Elster 1989; Peterson 1994; Swedberg 2001; among others). In general, game theory makes such unrealistic, overly simplified assumptions about human actors and their interactions that it substantially risks in most applications wrongly conceptualizing and analyzing such interaction.

In general, it lacks an elaborated language and conceptual framework to deal with the varieties of social agents, their roles, role relationships and complex interactions and outcomes. There is a great variety of interaction situations and games neither describable nor analyzable in the classical framework such as interactions of love and romance, interactions of hate and revenge, ritual and ceremonial interactions not characterizable by unidimensional maximizing behavior (as discussed later). In general, a wide variety of empirical phenomena cannot be addressed: for example, the players have a low level of knowledge about or possibly a highly delusional view of the game situation, its participants, the action alternatives and outcomes; in some cases players in a game may not know what game they are in or what role(s) they play vis-à-vis others. Under such conditions, they are likely to be uncertain about their own motives and potential moves, or unable to estimate the likelihood of the various outcomes or the value to be placed on each of them. Even when one knows about her own position, she may be unclear as precisely who she is playing against, and what are the possible implications of playing and of her particular actions. Even knowing her own possible moves, she may be quite unable to make any estimate of the likelihoods of various outcomes or the value to be placed on each of them. Of course, these various difficulties can be dealt with by approximating the possible outcomes along with the value and likelihood of each, and casting the result in a game matrix; but while this is justified as an exercise, the approximations may have (and are often seen to have), woefully little relation to real conditions (Goffman 1969, pp. 149–50).

There are two more or less widely recognized empirical areas of failure from a sociological and social science perspective concern: first, the lack of capability to describe and take into account social relations and social structure and, more generally, the socio-culltural and institutional conditions of games; second, the unrealistic assumptions about game participants’ knowledge, computational and judgment capabilities (“bounded rationality” (Simon 1955, 1979)).

(B) Classical game theory assumes default or very simple social relations where the actors are completely “autonomous” or independent from one another, and the social context is unspecified or ignored. Each actor judges the situation simply in terms of her own desires or values. There is no concern with other actors as such (e.g., empathy). This is illustrated by the classical rational agent who assigns values or preferences to outcomes and the patterns of interactions in terms of their positive implications for herself and tries to maximize her own gain or utility, only taking into account others in order to calculate how best to respond to them and to maximize her own gains.

Players do not have meaningful social relations and do not explicitly experience the constraints that such relations would entail. Rather, they are anomic beings, “strangers, aliens”—with neither roles or role relationships nor explicitly subject to influence of normative and institutional context. This is a very far from what is essential in basic social science theorizing.10

Such an extremely narrow conception of social relationships will not do. Actors are not only interdependent in action terms—as recognized in classical game theory—but in social relational, institutional, and cultural-moral terms. Norms, roles, role relationships, institutional arrangements, and cultural formations all play a role in enabling, constraining, and regulating social action and behavior .in a wide range of interaction situations. Such concepts must not only be a part of a social science oriented game theory but must be distinguishable from the constraints of material and technological structures, infrastructures, and built environments. It is important to point out that game theorists have increasingly recognized and tried to take into account the socio-cultural context (norms/institutions in particular) (see footnote 8), but they tend to conflate these in the “game structure” along with material and technology structures as “game constraints.” Sociologists find it necessary to distinguish social rule constraints which actors may or may not choose to comply with—from material constraints, which often may be fixed or given at least in the medium to short run.

There is a clear and present challenge to possess a rich set of distinctions relating to human agency, rule systems, social structure generally, change mechanisms, and drivers of action and interaction.

(C) Game theory makes heroic and largely unrealistic assumptions about actors: for instance, that they possess complete, shared, and valid knowledge of the game. Also, unrealistic assumptions are made about the abilities of players to compute (for example, assessing payoffs and the maximization of payoffs) and about the consistency of their preferences or utilities. At the same time, it has little or nothing to say about humans as moral beings—participating in moral communities; there is none of the morality that is carried and in many instances practiced by individuals and group. Finally, it lacks a language and concepts to address human creativity and innovative capacity.

Indeed, although mathematically interesting and engaging, it is, speaking generally, poor social science. In the final analysis, it is arguably a social science dead-end, in large part because it lacks an adequate conceptual language and analytic tools essential for the empirical description and analysis of game social structures, a great variety of social agents, and diverse social interactions. Norms, roles, role relationships, institutional arrangements, cultural formations, social power, and transformation, all refer to significant social phenomena. Moreover, it lacks a language and concepts to address the extraordinary human capacities of innovation, creativity, and transformation with respect to themselves and their systems. Finally, classical game theory has also little or nothing to say about humans as moral beings—participating in moral communities.

(2) The presentation here of SGT and IGT has stressed the importance of rules, norms, institutions, social relations and cultural forms such as rituals as well as social and technical algorithms, in theorizing and investigating human interaction behavior. Human behavior is conceptualized as based in large part on enacting or implementing social rule systems: rules, norms, algorithms, roles, institutional arrangements. Our presentation suggested also the rich variety of interaction forms and games as well as games characteristic of particiular institutional settings of, for instance, families, friendship networks, markets, administrative bodies, and policy systems; also, games of secrecy and deception, fabrication and lying, which have been central in IGT’s analyses are neither adequately present-able nor analyzable in the classical approach.

Moreover, the sociological approaches specify a number of special social relational and institutional forms—neglected by classical game theory—such as relations of intimacy and close friendship, solidarity as well as enmity, gender relations, hierarchy, market, and state-citizen relations. In the case of gender relations, many informal gender interactions are typically highly codified, and do not involve a maximization of outcome results, but instead entail the use of cultural scripts and rituals to maintain a particular social order (often underlying the preservation of hegemony by one type of group over the other).11

(3) Sociology approaches such as that of IGT and SGT elaborate the concepts of agency, and role concepts as part and parcel of interaction and game descriptions and analyses. Most conceptual tools of sociology and the social sciences are readily and easily incorporated into the sociological game approaches and can be applied empirically and policy-wise in fruitful ways.

(4) The emerging sociological game paradigm suggests multiple challenges and opportunities for further development. Of course, it still needs to be developed as a theoretical, empirical, and policy alternative of the classical framework.

(5) SGT provides a rule-based mathematics (shared in common with computer science, in particular Artificial Intelligence) and is very different from the mathematics of classical game theory (which concerns optimization). Rule based mathematics provides in a natural manner formal definitions of cultural and institutional forms, games, roles and role relationships, interaction norms and algorithms, etc. (Burns and Gomolinska 2000) (see Appendix A for further specification).

(6) Classical game theory (and rational choice theory) are amoral, if not anti-moral, theories of human behavior in that they fail to stress or fully recognize that human agents are moral beings with moral responsibilities, needs, and motivations. Of course, game theorists (and rational choice theorists) might counter that “morals are incorporated into the preference or utility functions). But this does not make explicit that morals apply in particular special ways in a given interaction situation, often playing a substantial role in interaction behavior, even contradictory roles. Also, groups, communities, and organizations require moral systems as a foundation for their effective functioning and development.

(7) In spite of its many, irredeemable limitations, classical game theory provides a number of methodological tools that have proved useful in social science conceptualizations and model-construction: The 2-person and n-person game matrices; interaction trees, the sociologically extreme cases of agents assumed to be anomic or alienated trying to maximize their narrow, selfish uni-dimensional utility functions, etc.

(8) These sociological developments of game theory provide a robust alternative to classical, game theory with it’s anomic, amoral and uncreative rational choice actors, its lack of specifiable norms and institutions, and without agential capacities in restructuring and transformation. Instead of hyper-rationality, hyper-knowledge, anomic relations, and actors without agency, the sociological variants have conceptualized and enabled the investigation and analysis of—games involving creative, interpretive, transformative, and normatively oriented agents, interacting in their diverse institutional and ritualistic contexts (Burns et al. 1985; Burns and Hall 2012).

Both sociological theories have been empirically applicable to real life situations. Goffman focused mainly on face-to-face interaction situations with a stress on ritual but also genuine strategic behavior in the classical game sense. SGT focused more on normatively and institutionally regulated interactions among parties involved in public policymaking, collaboration and exchange as well as diverse negotiation processes.

The sociological toolbox provides a systematic basis to describe, analyze, understand and explain patterns of interaction, their stability and transformation. In some cases, predictions of interaction patterns are possible because institutional arrangements and normative orders are powerful and stable. Interaction conditions can be analytically specified that are likely to lead to stable patterns, on the one hand, or to unstable patterns and disorder, on the other hand (Burns and Hall 2012).

All of the tools of sociology and the social sciences are readily and easily incorporated in the models—and ultimately in the general theories—and applied empirically and policy-wise. The emerging sociological game paradigm suggests multiple challenges and opportunities for further development.

Table 1 below identifies and remarks several of the key differences between the paradigm of classical game theory and the suggested sociological paradigm on a number of dimensions: the socio-cultural and institutional embeddedness of games; human agency; social structure (social relations, norms and other rules); game structuring, modification and transformation, the rule complex of action determination (as opposed to simple maximization of utility); the rule and context bases of the patterning of interactions and outcomes. This substantial paradigm difference—indeed, incompatibility—is grounded in particular sociological conceptions of human agency (actors not simply following instructions or implementing a simple universal principle, but behaving complexly, creatively, and morally), in games embedded in social structure (rule based culture and institutions), and in a conception of human interaction as highly diverse, dynamic, and not fully predictable (as exemplified in the case of the human use of rule-based language).

In sum, what we are claiming here is that the sociological approaches point to an alternative paradigm based on very different assumptions and propositions than those of classical game theory regarding the social embeddedness of games, social structure and social relationships, human agency, complex cognitive models, multiple often contradictory values, and multiple modalities of choice and action determinations. In the case of SGT even the type of mathematics and formalization differ from that of the classical theory; it is the mathematics of rules and rule complexes and its relationship to granular computing and artificial intelligence (see Appendix A)

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Helena Flam for her remarks and suggestions about earlier parts of this article; we are grateful also to the three anonymous reviewers for their criticisms and suggestions. This research was supported in part by the grant from Polish National Science Centre (2016/21/B/HS4/01583).

Author Contributions

Tom Burns and Ewa Roszkowska are responsible for much of the conceptualization and formalization, particularly of SGT. Machado contributed also to the conceptualization as well as to the designs of Figure A1 and the Tables. Tom Burns and Ugo Corte are responsible for preparation of the material in the article on Goffman.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Elaboration of SGT

Appendix A.1. Foundations

This Appendix specifies SGT further, elaborating the approach. SGT can be characterized as a cultural-institutional as well as a materialistic/technological approach to game conceptualization and analysis (Baumgartner et al. 1975; Burns 1990, 1994; Buckley and Burns 1974; Burns et al. 1985; also see (Ostrom 1990; Scharpf 1997)).27 The contribution of SGT is in its rule-based conceptualization of games as socially embedded with agents in social roles and role relationships and subject to cognitive, normative, and agential regulation.

(1) In SGT, a well-specified game structure is conceptualized in a uniform and general way as a multi-agent interaction rule complex or regime G in which typically the participating players have defined roles and role relationships in a game structure in a specified situation S (Burns and Gomolinska 1998, 1999, 2000, 2001; Gomolinska 2002, 2004, 2005).The rules may be imprecise, possibly inconsistent, and open to a greater or lesser extent to modification and transformation by the participants (as well as by third parties as in the prisoners’ dilemma game). Not all games are necessarily well-defined with, for instance, clearly specified and consistent norms and roles and role relationships. Many such situations can be described and analyzed in “open game” terms (Burns et al. 2017).28

Given an interaction situation St in context t (time, space, social and physical environment), some rules and subcomplexes of the general game structure G(t) are activated and implemented or realized. This G(t) complex includes then as sub-complexes of rules the players’ social roles vis-à-vis one another along with other relevant norms and rules R in the situation S (and context t).

Sociological concepts such as norm, value, belief, role, social relationship, and institution as well as classical game theory concepts can be defined in a uniform way in terms of rules, rule complexes, and rule systems, which are also defined as mathematical objects (see (2) following). These tools enable one to model social interaction taking into account economic, social psychological, and cultural aspects as well as considering games with incomplete, imprecise or even false information.

(2) The development of SGT has entailed the formulation of a mathematical theory of rules and rule systems at the same time combining it with a systematic grounding in key concepts of contemporary social sciences (Burns and Gomolinska 2000; Burns and Roszkowska 2005, 2007). Rules and rule complexes in SGT are then mathematical objects (Burns and Gomolinska 1998, 1999, 2000, 2001; Gomolinska 2002, 2004, 2005). SGT has developed the theory of rule activation and implementation as well as the theory of combining, revising, replacing, and transforming rules and rule complexes.29

SGT (or generalized game theory) based on the notion of a rule complex is a good example of a granular computing framework from the standpoint of Artificial Intelligence (AI). Rule complexes, and one- or multi-level structures built of rules are complex information granules. Granular computing is a computing paradigm in information processing. It is also conceived as an umbrella term for a class of theories, methodologies, and techniques making use of the notion of an information granule, introduced by Lotfi A. Zadeh. According to Zadeh’s definition, an information granule is a clump of objects brought together on the basis of indistinguishability, similarity or functionality. In many cases, computing with information granules rather than with single objects forming these granules proved to be useful in the process of problem solving. In a nutshell, SGT belongs to the class of granular computing frameworks. Granular computing brings together theories, methodologies, and techniques based on the concept of an information granule. The granular computing approach is applicable in problem solving, and such problem solving is a field of Artificial Intelligence.

(3) Game social rules are distinguished from more material and technical constraints. In SGT, there is an explicit game rule complex, G(t)—together with the physical and ecological constraints—that structure and regulate action and interaction.

(4) A well-specified game in the context or situation St at time t, G(t), is an interaction structure in which the participating actors typically have defined roles and role relationships (see Figure A1 and, in general, are subject to the normative regulation of institutions, cultural formations, and specific social relationships.

Sociology recognizes multiple bases for actors to adhere to norms and roles as well as to other rules in their interactions: mutual long-term commitment to a group or relationship embodying the norms, intrinsic value or interest in the norms, third party (a group or specialized unit) enforcement of adherence to the norms; and a strong sense of cognitive and social order arising from rule adherence and rule-following (Burns 2008; Burns and Flam 1987; Burns and Hall 2012). Of particular interest to sociologists are the rituals and the management of rituals in interaction, to establish and maintain rule adherence. Yet, concrete game situations may see actors breaking or deviating from game rules under particular conditions.

(5) A social role is a particular rule complex. An actor’s role complex is specified in SGT in terms of a few basic cognitive and normative components, that is rule subcomplexes, functioning as the basis of the incumbent’s values, perceptions, judgments and actions in relation to other actors in their particular roles in the defined game. Typically, actors play a number of different roles and are involved in multiple social relationships and institutional domains.

An actor’s role (ROLE(i,t) is specified in SGT in terms of a few basic cognitive and normative components presented and discussed below. Rule complexes and subcomplexes are formalized as mathematical objects (Burns and Gomolinska 1998, 1999, 2000, 2001; Gomolinska 2002, 2004, 2005)). The role complex includes, among other things: particular beliefs or rules that define the reality of relevant interaction situations; norms and values relating, respectively, to what is good or bad and what to do and what not to do; repertoires of strategies, programs, and routines; and a complex to determine actions as well as choices in the game. The rule complex(es) of roles in a particular game or social context guide and regulate the participants in their actions and interactions at the same time that in “open games” actors may restructure and transform the game and, thereby, the conditions of their actions and interactions.

(6) Judgment—a core concept in SGT (Burns and Gomolinska 2000, 2001; Burns and Roszkowska 2004; Burns et al. 2005). The major basis of judgment is a process of comparing and determining similarity. The capacity of actors to judge similarity or likeness (that is, up to some threshold, which is specified by a meta-rule or norm of stringency), plays a major part in the construction, selection, and performance of action. In this paper, the focus is on similarity of the properties of an object with the properties specified by a value or norm. But there may also be comparison-judgment processes entailing the similarity (or difference) of an actual pattern or figure with a standard or prototypical representation.

For our purposes here, we have focused on judgments about action. Other types of judgments are distinguished in SGT, for instance, value judgments, factual judgments, action judgments, among others.

The action judgment process can be connected with one option, two options, or a set of options. In case of a single option judgment, each actor i estimates the “goodness of fit” of this option in relation to her values in VALUE(i,t). In the case of two options, the actor judges which of them is better (and possibly how much better). In the case of a set of three or more options, the actor chooses one (or a few) from the set of options as “better than the others”.