Abstract

Eco-anxiety has emerged as a significant psychological response to the climate crisis. Yet its relationship with pro-environmental behavior remains far from settled, with findings ranging from behavioral paralysis to active engagement and seemingly contradictory evidence accumulating across studies. To clarify both the magnitude of this association and the conditions under which it holds, we conducted a systematic review and three-level random-effects meta-analysis. We systematically searched five databases (ProQuest, APA PsycArticles, PubMed, among others) through April 2025, identifying 20 independent studies that contributed 60 effect sizes (N = 34,206). The pooled results revealed a significant, small-to-moderate positive association between eco-anxiety and pro-environmental behavior (r = 0.24, 95% CI [0.15, 0.32], p < 0.001). So far, fairly straightforward. The complication emerged when examining heterogeneity: we observed substantial variation across studies (I2 = 95.4%), with a 95% prediction interval ranging from −0.22 to 0.61. What this tells us is that eco-anxiety does not uniformly predict action across contexts; the variability is considerable and meaningful. Moderator analyses offered important clarification. The association proved significantly stronger for public and collective behaviors, such as activism and advocacy (r = 0.36), compared to private sphere actions (r = 0.22). Beyond this, effects were more robust in adult samples (r = 0.30) than among adolescents (r = 0.18). These findings suggest something worth emphasizing: eco-anxiety appears to function not merely as a pathological burden but as an adaptive, context-sensitive correlate of collective engagement. Put differently, the distress people experience in response to climate change may channel productively into systemic action, particularly when social and collective pathways are available. What this means for practice is significant. Future interventions, in this perspective, should focus on channeling climate distress toward collective, structural engagement rather than defaulting to individual behavioral prescriptions alone.

1. Introduction

Global warming is having a significant impact on the planet. There is strong evidence that human activities, particularly greenhouse gas emissions, are contributing to rising temperatures in the atmosphere, oceans, and land. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC 2023), these changes are reflected in the increasing frequency of extreme events such as heat waves, heavy rainfall, droughts, and tropical cyclones. Copernicus’ Global Climate Highlights 2024 report confirms that 2024 has been the hottest year on record, and the first in which the global annual mean temperature exceeded 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels.

Climate change has significant impacts on both physical and mental health (Gawrych 2022; Charlson et al. 2021) and contributes to the emergence of psychoterratic syndromes (Albrecht 2011), including eco-anxiety. The American Psychological Association (APA) defines eco-anxiety as “a chronic fear of environmental doom” (Clayton et al. 2017, p. 71). More broadly, eco-anxiety may be conceptualized as a pervasive concern regarding the deteriorating relationship between humanity and the natural environment. Recent research has identified neurological correlates of eco-anxiety (Carlson et al. 2024), and its manifestations have been documented in both children (Léger-Goodes et al. 2022) and adolescents (Niedzwiedz et al. 2023).

The concept of eco-anxiety encompasses a broad spectrum of definitions, including emotions such as guilt, fear, worry, despair, shame, and hopelessness (Kurth and Pihkala 2022; Cianconi et al. 2023; Coffey et al. 2021; Pihkala 2020). It is possible to differentiate at least three distinct behavioral responses: an anxiety-type response characterized by nervousness and fear, a self-reflective response involving shame and guilt, and a pain-oriented response manifesting as anger and distress (Pihkala 2022).

In this context, elevated levels of climate anxiety can lead to eco-paralysis, a state of behavioral stagnation characterized by feelings of helplessness or fatalism (Albrecht 2011). However, eco-anxiety should not be regarded solely as a pathological reaction; it can also be interpreted as an existential and political response to the ongoing climate crisis, reflecting a natural reaction to increased awareness of environmental and climatic threats (Verplanken and Roy 2013). This form of anxiety manifests through a range of emotional, cognitive and physiological responses in individuals (Malboeuf-Hurtubise et al. 2024).

In this sense, it signals both the urgency for change and the potential to inspire pro-environmental activism (Banwell and Eggert 2024). Pro-environmental activism appears to have increased in recent years, particularly among younger generations, partly influenced by the prominent figure of Greta Thunberg (Hickman et al. 2021).

Pro-environmental behavior (PEB), also referred to as green, sustainable, or eco-friendly behavior, is defined as a set of deliberate actions undertaken by individuals to benefit the environment (Lange and Dewitte 2019; Olya and Akhshik 2019). PEB can manifest in private actions, such as adopting consumption patterns that conserve natural resources, as well as in public actions, including participation in demonstrations or signing petitions that advocate for policies promoting or enabling pro-environmental lifestyles (Stern 2000).

Climate change anxiety has been positively associated with increased engagement in climate change activism (Latkin et al. 2022; Kurth and Pihkala 2022) and, more broadly, with increased pro-environmental behavior (Anneser et al. 2024; Ogunbode et al. 2022; Maran and Begotti 2021; Verplanken and Roy 2013).

Specifically, eco-anxiety can be regarded as an adaptive coping mechanism operating at both individual and collective levels (Bakul et al. 2025; Ágoston et al. 2022; Clayton 2020). The literature contains numerous studies examining the impact of climate change-related distress, often referred to as “eco-distress,” on pro-environmental behavior (Urbild et al. 2023). Specific emotions, such as fear, are associated with increased pro-environmental behavior, while emotions like guilt and anger are linked to participation in protests (Stollberg and Jonas 2021). Other climate-related emotions, including eco-guilt and eco-grief, eco-rage (Contreras et al. 2024), eco-fear (Von Gal et al. 2024), and eco-worry (Vecina et al. 2025; Lenhard et al. 2024; Parmentier et al. 2024), have also been shown to promote pro-environmental actions.

Today, climate change is an undeniable reality, so pressing that addressing its impacts has become a central objective of the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda (Romano et al. 2024). A study by (Kleres and Wettergren 2017) argues that emotions such as fear, hope, anger and guilt underpin climate activism. How these emotions are managed influences activists’ motivations and mobilization strategies. This argument is grounded in the theoretical premise that emotions serve to energize and direct all forms of action. Specifically, fear functions as a motivator by heightening awareness of the threat of climate catastrophe. However, the paralyzing potential of fear is mitigated by hope: hope motivates action, and collective action, in turn, reinforces hope and helps manage fear. Regarding other potential predictors of climate action, based on Social Identity Theory (Worley 2021). (Wright et al. 2022) proposed that engagement in environmental collective action is more likely for people who can clearly imagine what a sustainable world would look like. In terms of pro-environmental behavior specifically, (Hamann and Reese 2020) suggest that self-efficacy, collective efficacy and participatory efficacy tend to predict pro-environmental behavior. Specifically, self-efficacy predicts private PEB, and participatory efficacy predicts public PEB. Despite increasing attention to eco-anxiety and its psychological effects, current research offers fragmented and sometimes contradictory evidence regarding its influence on pro-environmental behavior. This meta-analysis provides an original contribution by systematically integrating and quantifying the existing literature, while explicitly examining the role of moderators that may shape this relationship. By addressing these moderating factors, our study offers a deeper understanding of when and how eco-anxiety can translate into environmental action.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

A preliminary search was conducted on Google Scholar to survey the existing literature on the topic. This search revealed a considerable amount of popular material; however, the research required the identification of scholarly articles specifically investigating the construct through studies that administered validated questionnaires to target populations.

Subsequently, a systematic search was carried out between December 2024 and April 2025 through the use of multiple academic databases, including PubMed, ProQuest, APA PsycArticles, ScienceDirect, and PMC.

The following keywords were used: “eco-anxiety” OR “climate change anxiety” AND “pro-environmental behavior.” This search yielded a total of 1170 articles. There are validated eco-anxiety measurement tools available. The decision to include only studies employing these validated instruments is essential to enable the comparison of measurable dimensions of the construct. Additionally, we prioritized studies that provided empirical data, focused on human participants, and were published in peer-reviewed journals. Studies lacking sufficient methodological detail, using non-validated measures, or not directly addressing eco-anxiety were excluded. These criteria allowed us to narrow the pool to studies that are methodologically sound and directly relevant to understanding the construct, ensuring the reliability and interpretability of our synthesis.

The breakdown of results by database is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Distribution of Search Results by Database.

2.2. Research Questions and Analytical Approach

The primary aim of this meta-analysis is to establish the magnitude and direction of the association between eco-anxiety and pro-environmental behavior.

Drawing on prior meta-analytic evidence and theoretical models, we hypothesize a small to moderate positive association between eco-anxiety and pro-environmental behavior (r = 0.20–0.35). This expectation is grounded in existing meta-analyses reporting generally positive associations (Heeren et al. 2022): r = 0.41; (Becht et al. 2024): β = 0.10–0.36) and theoretical frameworks such as problem-focused coping and values-beliefs-norms theory, which suggest that eco-anxiety should motivate action. However, the anticipated effect size remains modest, given competing psychological mechanisms, including paralysis, avoidance, and substantial individual differences in anxiety responses documented in the literature.

Beyond establishing the overall effect, several moderator analyses will be conducted to explore conditions under which the relationship between eco-anxiety and pro-environmental behavior varies. A central question concerns whether the type of pro-environmental behavior moderates this relationship. We hypothesize that the association will be stronger for public and collective behaviors, such as activism, advocacy, and policy support, compared to private individual behaviors like recycling or energy conservation. This expectation is informed by findings from (Becht et al. 2024) indicating stronger effects for public behaviors (β = 0.36) than private behaviors (β = 0.10). Theoretically, collective action may provide greater perceived efficacy and social support for coping with anxiety, while anxious individuals may perceive public actions as more impactful in addressing climate threats. Conversely, we anticipate weaker associations for policy support compared to direct behavioral engagement, as policy support represents a more abstract and potentially less psychologically reinforcing coping mechanism.

Population type presents another theoretically relevant moderator. We will examine whether the association differs across developmental stages, hypothesizing stronger effects among adolescents and young adults compared to general adult populations. This hypothesis is based on the developmental salience of future-oriented concerns in younger populations and the role of identity formation and moral development in enhancing anxiety-behavior coupling. However, a competing hypothesis posits that adults may show stronger effects due to greater behavioral autonomy and resources, while an alternative possibility suggests similar associations across age groups if eco-anxiety operates as a universal motivator regardless of developmental stage.

A particularly important question concerns the dimensional structure of eco-anxiety and whether specific facets show differential associations with pro-environmental behavior. We hypothesize that personal impact, anxiety, and rumination will demonstrate stronger associations with behavior than affective symptoms or functional impairment. This expectation draws on recent findings showing that rumination and personal impact uniquely predicted pro-environmental behavior in path models (Hogg et al. 2024). Rumination reflects sustained cognitive engagement with climate threats, while personal impact captures perceived self-relevance, both of which should theoretically motivate behavioral responses. Conversely, affective and functional impairment dimensions, which tend to correlate more strongly with mental health problems than behavioral engagement, are expected to show weaker or non-significant associations. These symptomatic dimensions may reflect eco-paralysis or avoidance rather than motivation.

Methodological characteristics of included studies will also be examined as potential moderators. We anticipate that cross-sectional studies will yield larger effect sizes than longitudinal studies, consistent with the known inflation of correlations due to common method bias in cross-sectional designs. Longitudinal studies, which control for baseline behavior and isolate true predictive effects, have shown more modest associations in available evidence (Pavani et al. 2023): cross-lagged β = 0.15), and we expect this pattern to emerge across the broader literature.

Geographic and cultural context will be explored, though existing literature shows substantial underrepresentation of Global South samples. We hypothesize similar associations across contexts, suggesting universal psychological processes linking anxiety and behavior. However, competing hypotheses suggest that structural barriers such as limited resources and infrastructure in Global South contexts could weaken the translation of anxiety into behavior, or conversely, that greater resources and privilege in Global North contexts enable stronger behavioral responses.

Two exploratory questions warrant attention despite methodological limitations. The first concerns the possibility of a curvilinear, inverted-U relationship between eco-anxiety and pro-environmental behavior, as suggested by the eco-paralysis hypothesis (Albrecht 2011; Wullenkord and Reese 2021). While some evidence suggests curvilinearity (Becht et al. 2024) and moderation showing weaker effects at high anxiety levels (Heeren et al. 2022), other studies report linear effects. Given that meta-analysis cannot directly test curvilinearity without individual-level data, we will instead examine whether studies explicitly testing for quadratic effects report different mean effects than those assuming linearity.

Finally, the measurement approach represents a potentially meaningful distinction. We hypothesize that trait eco-anxiety, which captures stable individual differences, will show stronger associations with pro-environmental behavior than state anxiety measures. This expectation is grounded in theoretical considerations that stable individual differences drive more consistent behavioral patterns than context-dependent affective states, and receives support from within-person studies showing smaller state-level effects compared to between-person trait associations (Lutz et al. 2023).

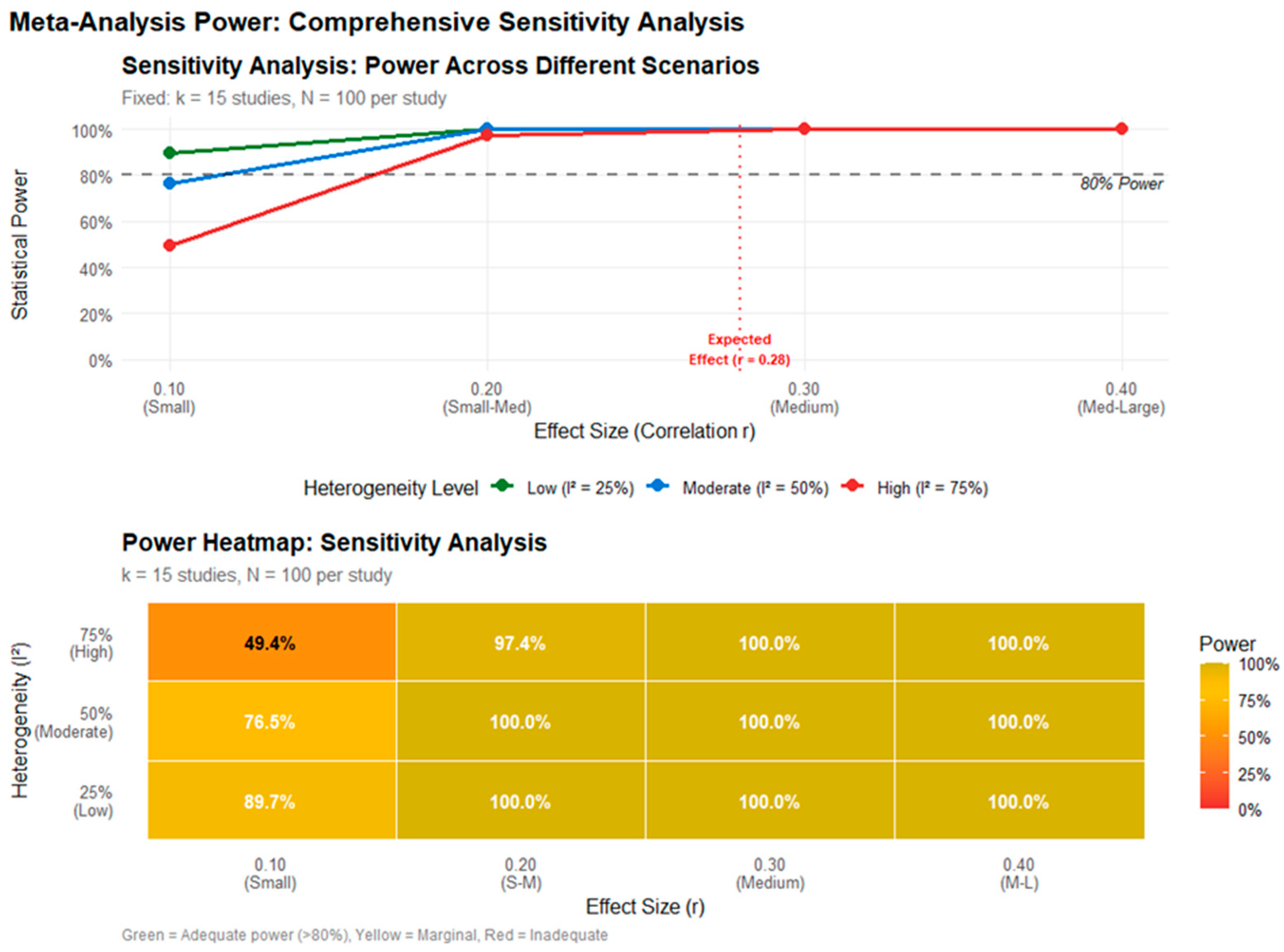

First of all, an a priori power analysis was conducted using version 0.2.2 of the metapower R package. Based on Cohen’s (1988) benchmarks and effect sizes reported in prior meta-analyses in environmental psychology (Bamberg et al. 2015; Klöckner 2013), an effect size of r = 0.28 was anticipated. Given the diversity in populations, measurement instruments, and study designs, high heterogeneity (I2 = 75%) was expected.

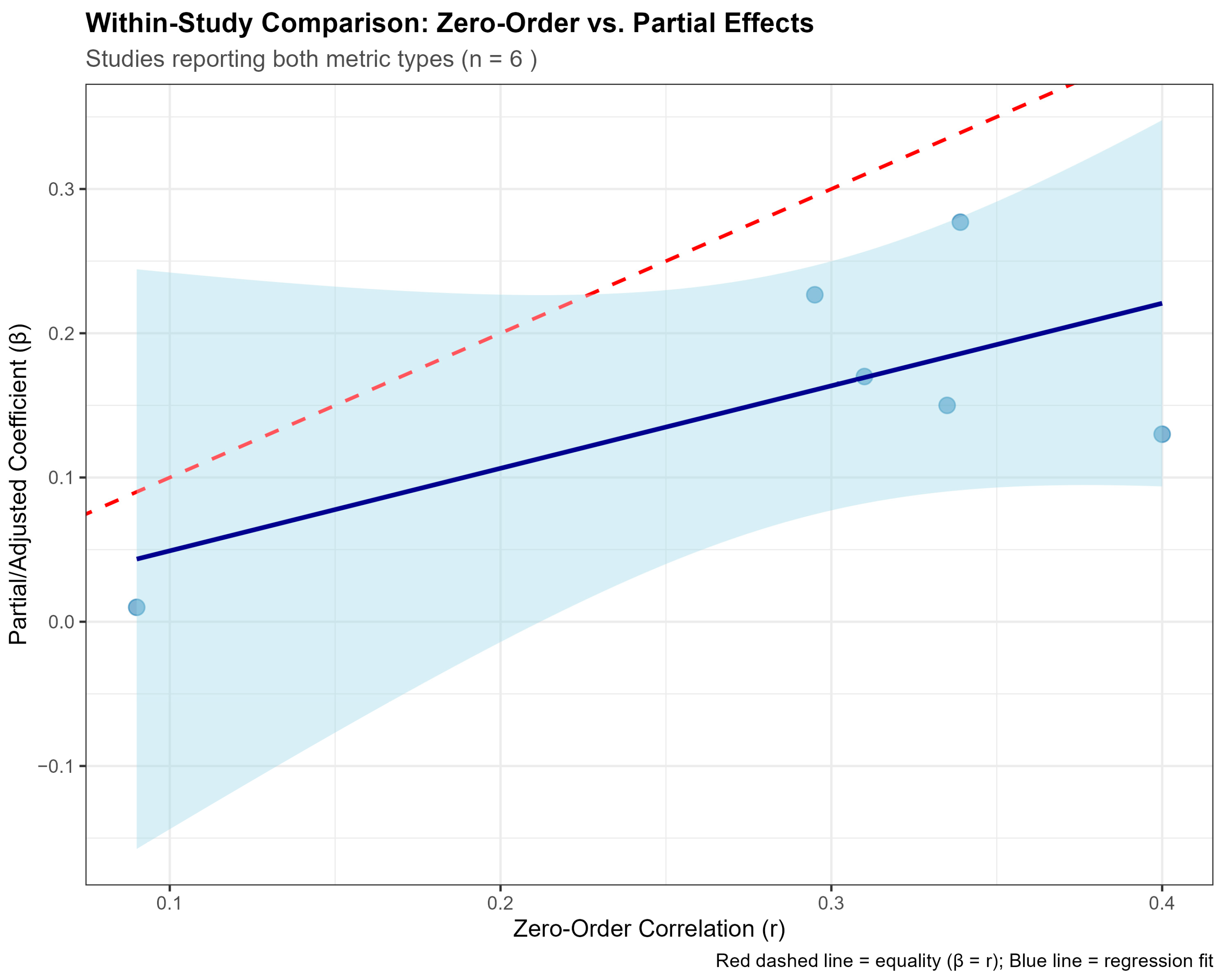

For the minimum threshold scenario of k = 15 studies with N = 100 participants per study, the analysis indicated excellent statistical power, exceeding 99%, to detect the expected effect, as shown in Figure 1. Sensitivity analyses revealed that power remains adequate (above 80%) for medium effects (r ≥ 0.30) across all heterogeneity levels. However, power drops below this threshold for small effects (r < 0.20) when heterogeneity is high.

Figure 1.

The upper panel displays statistical power curves across varying effect sizes and heterogeneity levels, with the expected effect (r = 0.28) marked by a vertical dashed red line. The lower panel presents a heatmap of power values for the same parameters. All analyses assume a fixed scenario of k = 15 studies and N = 100 participants per study.

For each eligible study, we extracted sample characteristics (e.g., sample size, age, geographic region), study design, anxiety measures, and pro-environmental behavior (PEB) types. PEB measures were categorized into four domains: General/Mixed, Private Sphere, Public Sphere, and Specific. Geographic regions were classified as Global North or Global South.

2.3. Data Analysis Strategy

2.3.1. Effect Size Calculation and Aggregation

The primary effect size metric was the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient (r). All effect sizes were transformed to Fisher’s z scale for analysis and back-transformed for reporting. To manage statistical dependency in studies reporting multiple effect sizes for the same sample without a global index, we adopted a conservative synthetic aggregation procedure. Specifically, for the study by Leite et al. (2023), which reported a correlation matrix between four anxiety subscales and three behavioral domains without a composite score, we avoided simple arithmetic averaging, which would introduce bias. Instead, we applied Fisher’s r-to-z transformation to all pertinent zero-order coefficients (k = 12), calculated the mean z value, and back-transformed the result into a single composite coefficient (r = 0.339). We opted for this synthetic aggregation strategy to preserve the independence of the sampling unit. This approach prevents the inflation of Type I error rates that can occur when treating multiple correlated effect sizes from the same sample as independent observations.

2.3.2. Three-Level Meta-Analytic Model

To account for the hierarchical structure of the data, where multiple effect sizes were often nested within the same study, we conducted a Three-Level Random-Effects Meta-Analysis. This model decomposes variance into sampling variance (Level 1), within-study variance (Level 2), and between-study variance (Level 3), preventing the inflation of Type I error rates associated with treating dependent effects as independent (Cheung 2014). Heterogeneity was assessed using Q and I2, and 95% Prediction Intervals (PI) were calculated to estimate the range of true effects in future studies.

2.3.3. Sensitivity Analysis: Metric Type and Robustness

A sensitivity analysis was explicitly conducted to test the robustness of findings across metric types. We rigorously distinguished between zero-order correlations and partial coefficients to create two distinct models: Model B (Zero-Order): Included only pure bivariate correlations to estimate the raw association. Model C (Adjusted): Included estimates derived from multivariate models. To ensure the robustness of Model B, we strictly excluded estimates derived from mixed models or multiple regressions, allocating them instead to Model C. For example, the study by Mathers-Jones and Todd (2023), despite providing a convertible t-value, was derived from a Linear Mixed Model controlling for intra-subject variance; it was therefore classified as a multivariate effect rather than a zero-order correlation.

2.3.4. Software and Packages

All statistical analyses were conducted using the R statistical computing environment (Version 4.4.1, 2024) and RStudio (Version 2024.09.0+375). The primary analyses were executed using the metafor package (Version 4.6-0). Data manipulation was performed using dplyr and stringr.

2.3.5. Data Extraction and Coding

For each eligible study, we extracted a comprehensive set of variables including bibliographic details (authors, year of publication, title) and sample characteristics, specifically sample size, age range, geographical context, and gender distribution. Regarding the primary constructs, we recorded the specific scales used to measure climate anxiety and pro-environmental behaviors, as well as the specific type of behavior assessed. Statistical data extraction focused on effect sizes (correlations or beta coefficients), standard errors (SE), confidence intervals (CI), and relevant methodological notes.

This process was conducted by two independent coders using a standardized form developed for this meta-analysis. The form was piloted on a subset of studies and refined prior to full implementation. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion and, where necessary, consultation with a third reviewer. The inter-rater reliability for the extraction process was excellent, with an intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.92.

2.3.6. Risk of Bias Assessment

The quality of included studies was assessed using an adapted version of the Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies (Effective Public Health Practice Project 2003) [68], which evaluates studies on selection bias, study design, confounders, blinding, data collection methods, withdrawals and dropouts, intervention integrity, and analysis. Each study was rated as strong, moderate, or weak on each domain, and an overall rating was assigned. Two independent reviewers conducted the quality assessment, and disagreements were resolved through discussion. The inter-rater reliability for the quality assessment was calculated using weighted kappa (κw = 0.84), indicating strong agreement. Publication bias was assessed using funnel plots, Egger’s test, and trim-and-fill analysis. These methods allowed for a comprehensive evaluation of potential publication bias and its impact on the meta-analytic results.

2.4. Data Synthesis and Statistical Analysis

2.4.1. Effect Size Calculation

For the primary meta-analysis, Pearson correlation coefficients (r) between climate anxiety and pro-environmental behaviors were used as the effect size measure. When studies reported other statistics (e.g., standardized regression coefficients, odds ratios), these were converted to correlation coefficients using established formulas. When multiple effect sizes were reported within a single study (e.g., for different subscales or outcomes), these were averaged to create a single effect size per study to ensure independence of observations. All correlation coefficients were transformed using Fisher’s z transformation to normalize the distribution and stabilize the variance, following standard meta-analytic procedures. The transformation formula used was z = 0.5 × ln[(1 + r)/(1 − r)]. Standard errors for the transformed effect sizes were calculated based on sample size using the formula: SE = 1/√(N − 3).

After analysis, the results were back-transformed to the correlation metric for ease of interpretation.

2.4.2. Meta-Analytic Model

A random-effects model was employed using the restricted maximum likelihood (REML) estimation method to account for heterogeneity between studies. This approach assumes that the true effect sizes vary across studies due to differences in study characteristics and not just sampling error, which is appropriate given the expected heterogeneity in this field. Heterogeneity was assessed using the Q statistic, which tests whether observed differences in results are compatible with chance alone, and the I2 statistic, which describes the percentage of variation across studies due to heterogeneity rather than chance. I2 values of 25%, 50%, and 75% were interpreted as low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively, following Higgins et al. (2003). Additionally, the between-study variance (τ2) was reported to quantify the true variance in effect sizes.

2.4.3. Moderator and Sensitivity Analyses

To investigate whether the association between climate anxiety and pro-environmental behaviors varied as a function of study characteristics, we conducted subgroup analyses and, where appropriate, meta-regression. We examined three potential moderators: the instrument used to assess climate anxiety (e.g., CCAS, HEAS), the geographical region in which the study was conducted (North America, Western Europe, Asia, Oceania), and the age group of participants (youth/adolescents vs. adults). For categorical moderators, we used the QB statistic to test for between-group differences in effect sizes. For continuous moderators (when available), we fitted random-effects meta-regression models to examine the relationship between the moderator and the observed effect sizes.

To assess the robustness of the findings, we conducted a series of sensitivity analyses. First, we performed an influence analysis using a leave-one-out procedure to identify studies exerting disproportionate impact on the pooled effect. Second, we re-estimated the overall association after excluding studies that had been rated as “weak” in the quality assessment. Third, we examined the consequences of alternative correlation pre-processing decisions, comparing models that included all effect sizes separately with models based on correlations averaged within studies. Finally, we fitted a fixed-effect model and contrasted its results with those of the primary random-effects model.

All analyses were carried out in R version 4.2.0 using the metafor package (Viechtbauer 2010), the meta package (Balduzzi et al. 2019), and metaviz (Kossmeier et al. 2020). Forest plots, funnel plots, and other graphical displays were produced with ggplot2 (Wickham 2016), using a custom theme aligned with APA 7 guidelines.

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics and Descriptive Statistics

The final dataset comprised 60 effect sizes extracted from 20 independent studies, representing a total of 34,206 participants. Sample sizes ranged from 96 to 2080 participants (Median = 476). The majority of effect sizes were derived from cross-sectional designs (k = 53, 88.3%), with the remainder from longitudinal studies (k = 7, 11.7%). Thirty-three effect sizes (55%) were zero-order correlations, while 27 (45%) were partial or standardized coefficients from multivariate models. Geographically, most studies were conducted in Global North contexts (k = 47, 78.3%), with limited representation from Global South countries (k = 5, 8.3%) and mixed samples (k = 8, 13.3%). Specifically, the studies included in the meta-analysis are heavily concentrated in Western and industrialized countries, with Australia, Canada, and Portugal accounting for the largest number of studies. Additional contributions were drawn from the United States, China, and France, and a small number of other countries. The most common population types were adults (k = 42, 70%), followed by adolescents (k = 9, 15%), students (k = 3, 5%), and mixed samples (k = 6, 10%). Effect sizes ranged from −0.44 to 0.60, with a mean of 0.24 (SD = 0.21). Pro-environmental behaviors were categorized as general/mixed (k = 27, 45%), public/collective actions (k = 16, 26.7%), private/individual behaviors (k = 12, 20%), or specific behaviors (k = 5, 8.3%).

3.2. Overall Effect Size

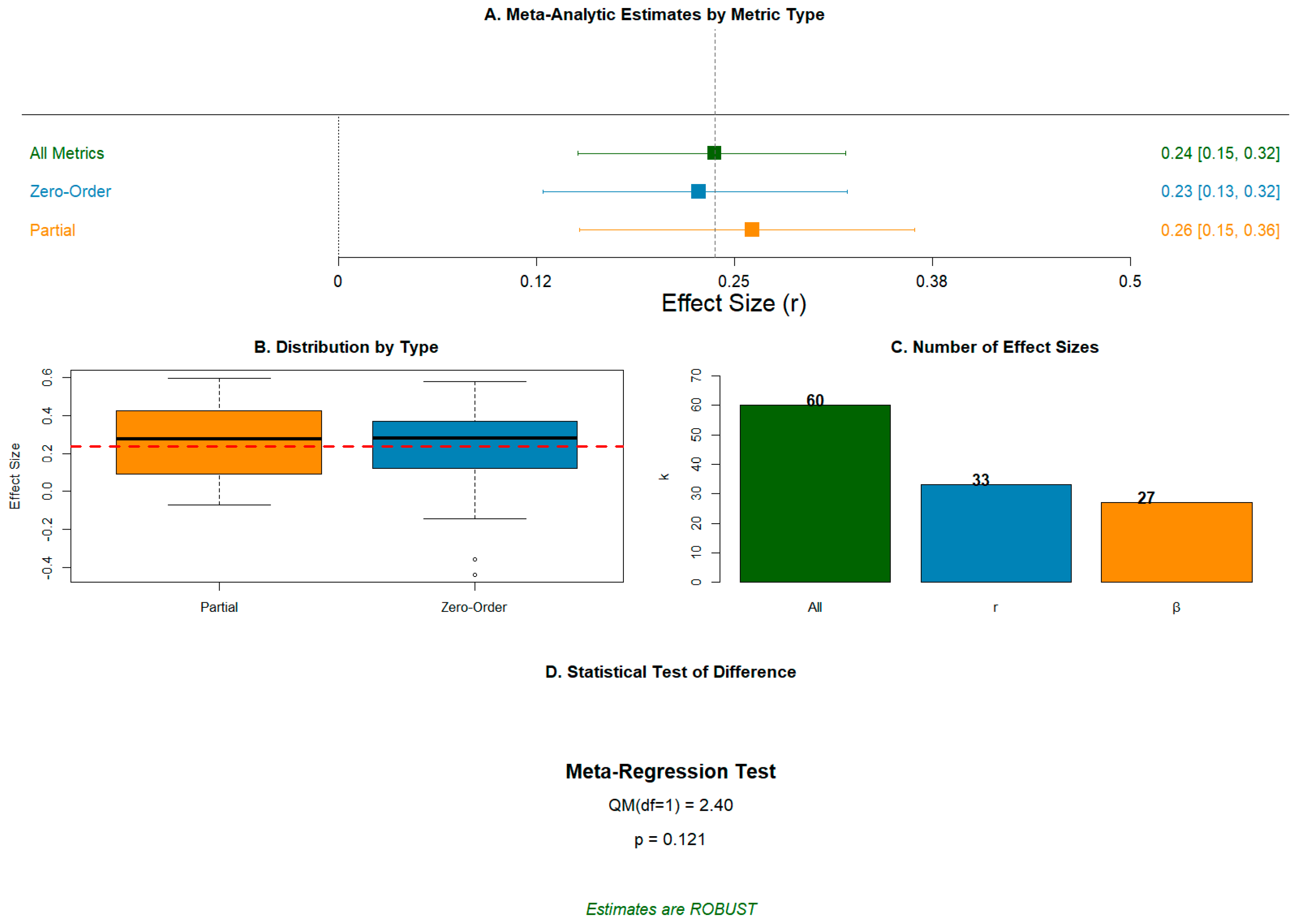

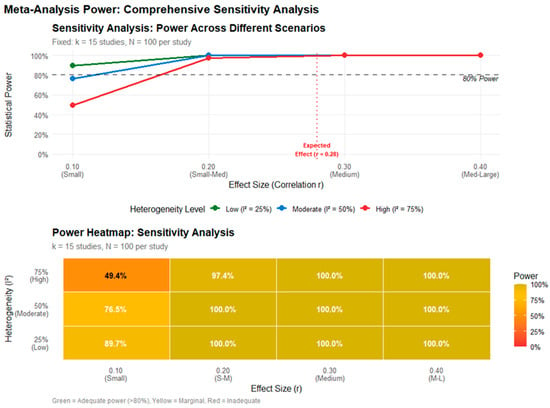

A three-level random-effects meta-analysis (effect sizes nested within studies) was conducted using restricted maximum likelihood (REML) estimation. The overall pooled effect size was r = 0.237 (95%CI [0.151, 0.320], z = 5.28, p < 0.001), indicating a small-to-moderate positive association between eco-anxiety and pro-environmental behavior (see Table 1 and Figure 2). This effect explained approximately 5.7% of the variance in PEB (R2 = 0.057). The 95% prediction interval was wide, ranging from r = −0.220 to r = 0.610, suggesting substantial variability in true effects across different contexts and populations. This considerable heterogeneity was confirmed by statistical tests: Q (59) = 2255.80, p < 0.001, with total I2 = 95.4%, indicating that 95.4% of the observed variance reflected true heterogeneity rather than sampling error. Decomposition of variance components revealed that 49.9% of total variance was attributable to within-study heterogeneity (σ2 = 0.0315) and 45.2% to between-study heterogeneity (σ2 = 0.0259), with only 4.9% due to sampling variance. This substantial heterogeneity justified the exploration of potential moderators.

Figure 2.

Section A: Forest plot showing meta-analytic estimates by metric type. Panel displays pooled effect sizes for all metrics combined (r = 0.24, 95% CI [0.15, 0.32]), zero-order correlations (r = 0.23, 95% CI [0.13, 0.32]), and partial/adjusted coefficients (β = 0.26, 95% CI [0.15, 0.36]). Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. This forest plot displays the pooled effect size estimates with their 95% confidence intervals across three analytical groupings. Zero-Order (blue square): When considering only zero-order correlations (simple bivariate associations without statistical control), the pooled effect size is r = 0.23, with a confidence interval of [0.13, 0.32]. This is marginally lower than the overall estimate and slightly narrower in its confidence bounds. Partial (orange square): Partial correlations (associations controlling for additional variables) yield an effect size of r = 0.26, with the widest confidence interval of [0.15, 0.36]. This higher point estimate suggests a slightly stronger relationship after accounting for confounding variables, though the wider interval reflects greater variability or heterogeneity among partial correlation studies. The vertical dashed line at r = 0.24 anchors the overall effect estimate. The substantial overlap of all three confidence intervals—combined with the non-significant meta-regression test in Section D (p = 0.121)—indicates that the choice of metric type does not produce meaningfully different conclusions about the underlying phenomenon. All three estimates converge on a small-to-moderate positive effect (using conventional effect size interpretation), suggesting robust evidence regardless of methodological approach. Section B: This box plot compares the distribution of effect sizes between two metric types: Partial and Zero-Order. The visualization reveals that both metric types produce similar median effect sizes (indicated by the horizontal line in each box), clustering around 0.2. However, Partial metrics display a notably wider distribution with greater variability (larger interquartile range), spanning from approximately 0 to 0.4, while Zero-Order metrics show a more concentrated distribution. Both distributions contain outliers (shown as individual dots), particularly evident in the Zero-Order metrics where one outlier extends below the lower whisker. The red dashed line at approximately 0.22 represents the overall mean effect size across both groups, demonstrating the central tendency of the combined data. Section C: This bar chart presents the frequency of effect sizes across three analytical levels. The sample comprises 60 total effect sizes, with the distribution broken down as follows: 60 studies contributed the “All” metrics category, 33 studies provided individual correlation coefficients (r), and 27 studies reported standardized regression coefficients (β). This hierarchical structure indicates that not all studies reported both correlation and regression estimates—a common pattern in meta-analyses where studies may employ different statistical reporting conventions. The declining frequency reflects the methodological heterogeneity of the source literature, with zero-order correlations being reported more frequently than partial correlations. Section D: This section presents the results of a meta-regression test comparing effect sizes across metric types. The test statistic (QM with 1 degree of freedom) equals 2.40, and the associated p-value is 0.121. Since the p-value exceeds the conventional significance threshold of 0.05, the result is not statistically significant. This indicates that the difference in mean effect sizes between Partial and Zero-Order metrics is not statistically distinguishable—in other words, both metric types yield comparable population effect estimates. The notation "Estimates are ROBUST" (shown in green text) suggests that the meta-analytic estimates have been computed using robust variance estimation methods, which increases confidence in the stability of these findings despite potential heterogeneity across studies.

3.3. Sensitivity Analysis

To evaluate whether the choice of effect size metric influenced the overall results, a sensitivity analysis was conducted comparing zero-order correlations (Model B) and partial/adjusted coefficients (Model C). As detailed in Table 1, the meta-analytic estimates remained robust across specifications. Specifically, the pooled effect size for zero-order correlations (r = 0.227) did not differ significantly from that of partial coefficients (β = 0.261), as indicated by the substantial overlap in their 95% confidence intervals (Model B: [0.133, 0.318]; Model C: [0.151, 0.365]). Although the point estimate for the partial coefficients was slightly higher, suggesting that controlling for covariates did not attenuate the observed relationship, this difference was not statistically meaningful. A meta-regression testing metric type as a moderator revealed no significant difference (QM (1) = 2.40, p = 0.121). Notably, partial coefficients were numerically larger than zero-order correlations (Δr = +0.034), particularly for private behaviors where partial coefficients (β = 0.295) were more than double the zero-order correlations (r = 0.124). This suggests a potential suppression effect, whereby controlling for general demographic or ideological variables (such as political orientation) reveals a stronger underlying link between anxiety and private behavior that was otherwise masked in the raw zero-order correlations. Heterogeneity remained high across all models (I2 > 94%), implying that the variation in effect sizes is driven by factors other than the metric type alone.

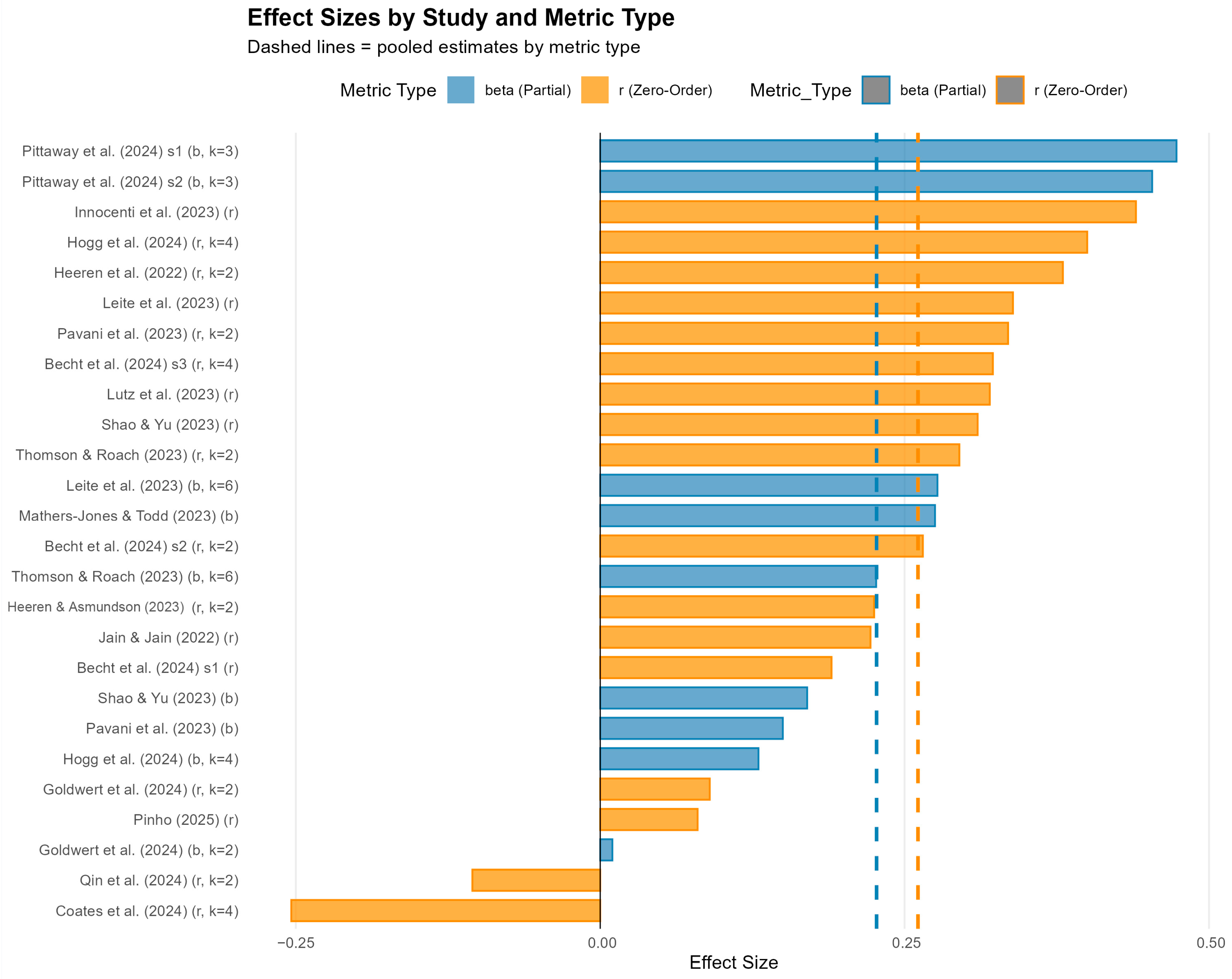

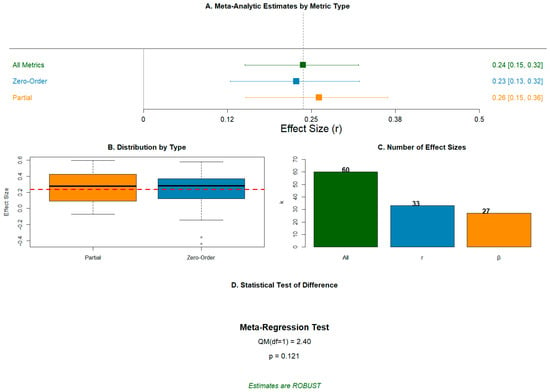

To provide a granular view of the dataset underlying the meta-analytic models, Figure 3 displays the aggregated effect sizes for each study, stratified by metric type. The visualization underscores the substantial heterogeneity observed, with estimates ranging from moderate negative associations (e.g., Coates et al. 2024; Qin et al. 2024) to strong positive effects (e.g., Pittaway et al. 2024). Despite this variability, a clear directional trend is evident: the vast majority of studies cluster in the positive region, supporting the hypothesis of a link between eco-anxiety and PEB. The vertical dashed lines represent the pooled estimates for partial coefficients (blue) and zero-order correlations (orange); their proximity visually confirms that, on average, the metric choice does not drastically alter the global conclusion, even though individual study estimates fluctuate significantly.

Figure 3.

The bar chart displays the mean effect size for each study included in the meta-analysis. Blue bars represent partial or otherwise adjusted coefficients (β), whereas orange bars correspond to zero-order correlations (r). Vertical dashed lines indicate the grand mean (pooled estimate) for each metric type, allowing visual comparison between individual studies and the overall effect. Studies are ordered by magnitude of effect size, and when a study contributed multiple independent samples or metrics, the number of contributions is reported in parentheses next to the study label (e.g., k = 3). (Pittaway et al. 2024; Innocenti et al. 2023; Hogg et al. 2024; Heeren et al. 2022; Heeren and Asmundson 2023; Leite et al. 2023; Pavani et al. 2023; Becht et al. 2024; Lutz et al. 2023; Shao and Yu 2023; Thomson and Roach 2023; Mathers-Jones and Todd 2023; Jain and Jain 2022; Goldwert et al. 2024; Pinho 2025; Qin et al. 2024; Coates et al. 2024).

Whether analyzing all studies together or examining zero-order and partial coefficients separately, the estimated effect size remains consistently small, positive, and statistically significant, consequently the aggregation of these metrics in the primary model (Model A) appears methodologically justified (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Sensitivity Analysis: Meta-Analytic Estimates by Effect Size Metric.

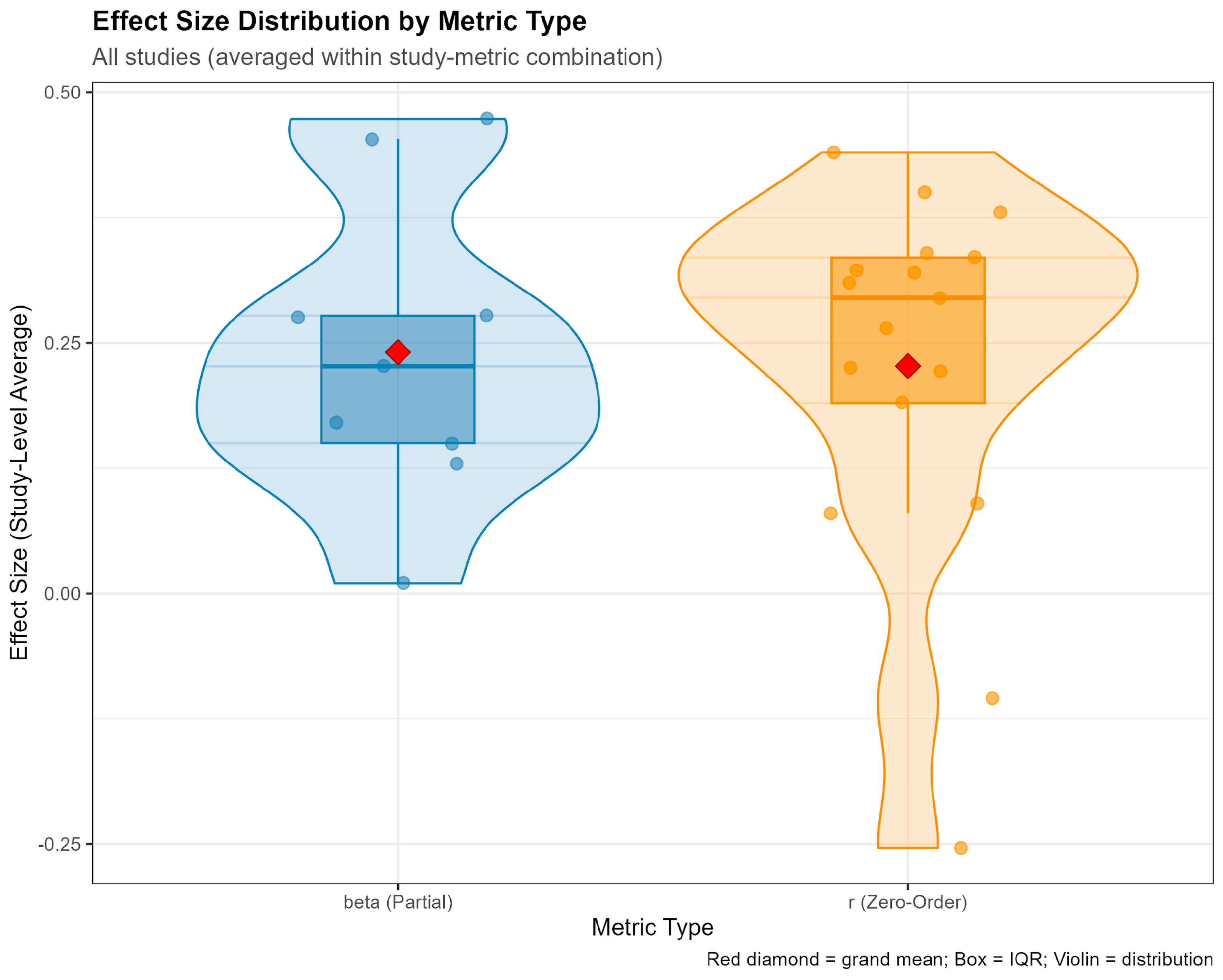

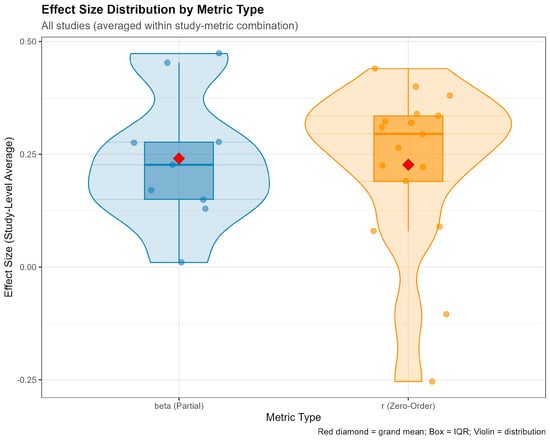

Figure 4 also provides crucial insight into the underlying data structure. Both distributions are wide, with individual effect sizes ranging from near zero to approximately 0.6. This visual spread of data points directly reflects the high heterogeneity observed in the meta-analysis (I2 > 94% for all models), indicating that while the average effect is small and positive, individual studies vary widely in their reported magnitudes. The distribution for partial coefficients appears slightly broader, suggesting potentially greater variability in effect sizes when other variables are statistically controlled for, though both distributions exhibit substantial spread.

Figure 4.

Violin plots display the density distribution of effect sizes for partial/adjusted coefficients (left, blue) and zero-order correlations (right, orange). Individual data points are overlaid to illustrate the spread of the observed effects (k = 60).

3.4. Moderator Analyses

3.4.1. Type of Pro-Environmental Behavior

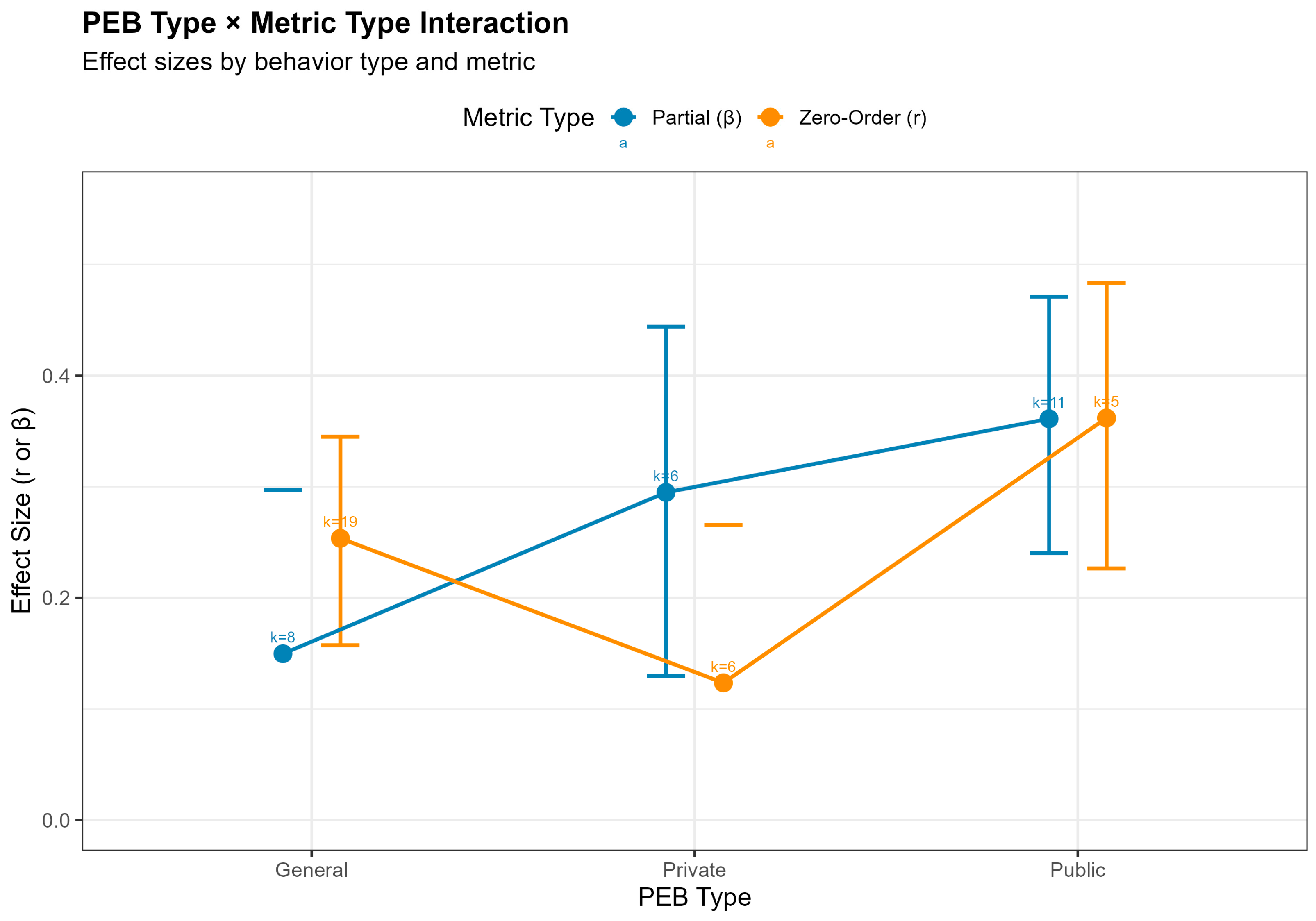

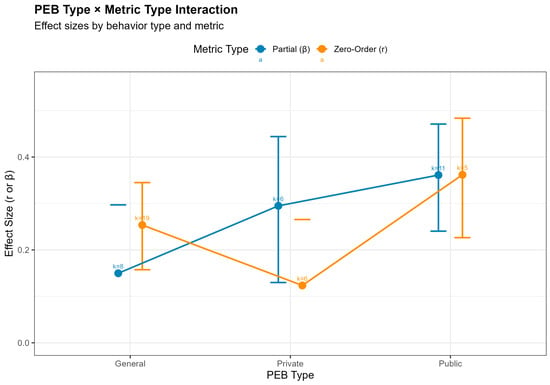

The association between eco-anxiety and pro-environmental behavior (PEB) differed significantly across behavioral domains (QM (2) = 47.42, p < 0.001). As shown in Figure 4, public or collective behaviors (e.g., activism, advocacy, policy support) exhibited the strongest association, r = 0.359, 95% CI [0.258, 0.452]. This estimate was significantly larger than those for private behaviors (r = 0.218, p = 0.022) and for general PEB measures (r = 0.228, p < 0.001). Pairwise comparisons indicated that the association with public behaviors exceeded that with private behaviors by Δr = 0.141 (approximately a 66% increase), supporting the hypothesis that eco-anxiety more strongly motivates collective forms of action than individual behavioral changes (see Figure 5).

Figure 5.

The plot illustrates the interaction between the type of pro-environmental behavior (General, Private, Public) and the effect size metric. Blue markers represent partial/adjusted coefficients (β), while orange markers represent zero-order correlations (r). Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. The number of effect sizes (k) is reported above each data point. Note the divergence in estimates for Private PEB, where partial coefficients significantly exceed zero-order correlations. Note. a: Zero-order (r) and Partial (β) correlations show unequivalent patterns across pro-environmental behavior types, where Public behaviors show stronger associations with eco-anxiety (r/β ≈ 0.36) than private behaviors (r/β ≈ 0.17–0.30), regardless of metric type.

Beyond these domain-level differences, effect-size estimates also varied as a function of the outcome metric (zero-order correlations vs. partial regression coefficients). For Public PEB, the relationship was highly consistent across metrics, with both zero-order correlations and partial coefficients converging on a relatively large effect (r ≈ β ≈ 0.36). For Private PEB, zero-order correlations were more modest (r ≈ 0.22, k = 6), whereas partial coefficients were considerably larger (β ≈ 0.29, k = 6), a pattern compatible with a suppression effect whereby controlling for covariates reveals a stronger underlying link between eco-anxiety and private behavioral change. For General PEB, the opposite pattern emerged: partial coefficients were attenuated relative to zero-order correlations (β ≈ 0.15 vs. r ≈ 0.25), suggesting that simple correlations may overestimate the association when broad, non-specific behavioral indices are used. Taken together, although public behaviors yielded the highest absolute estimates, the distinction between public and private domains becomes less pronounced once methodologically more rigorous partial coefficients are taken into account.

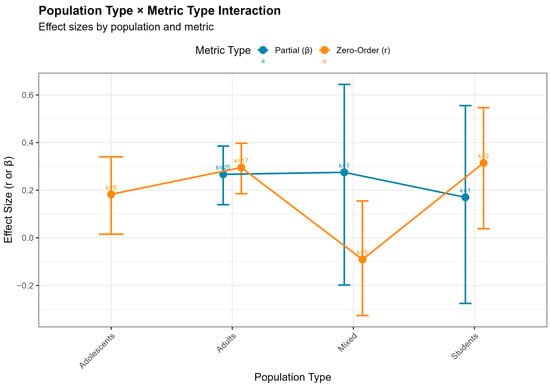

3.4.2. Population Type

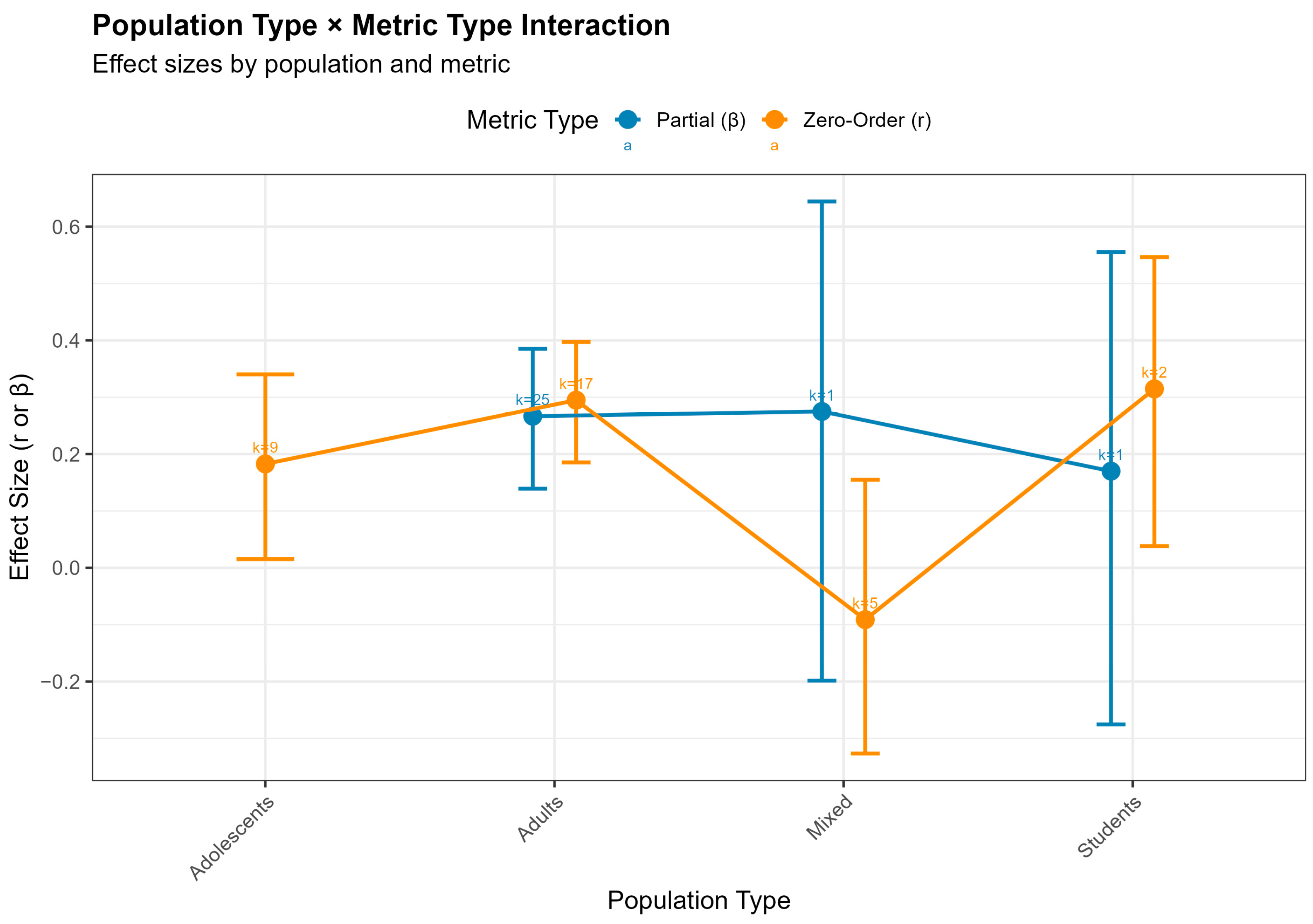

The strength of the eco-anxiety–PEB relationship varied significantly across population types, QM(3) = 36.22, p < 0.001. As depicted in Figure 5, adult samples yielded the most robust estimates, r = 0.295, 95% CI [0.199, 0.386], with zero-order correlations and partial regression coefficients closely aligned (r ≈ β). This convergence across metrics suggests that, in adult populations, the association is relatively stable and unlikely to be merely an artefact of confounding variables.

Findings for the other groups call for a more cautious reading, as shown in Figure 6. University students showed a strong pooled association, r = 0.272, yet visual inspection indicates a divergence whereby partial coefficients tend to be weaker than zero-order correlations, pointing to possible confounding processes that may inflate simple correlations in this sub-population. Adolescents exhibited a moderate effect, r = 0.184; however, this estimate rests entirely on zero-order correlations, as no study reported partial coefficients for this age group, which limits the extent to which confounding can be ruled out. Finally, mixed-age samples produced inconsistent and non-significant results, r = −0.007, p = 0.978, a pattern likely driven by substantial heterogeneity in sampling strategies and age compositions across studies.

Figure 6.

The interaction plot displays effect size estimates across four population categories. Blue markers represent partial/adjusted coefficients (β), while orange markers indicate zero-order correlations (r). Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals, and the number of effect sizes (k) is reported above each data point. Note the high stability of estimates for the Adult group compared to the Student group, and the absence of partial coefficients for Adolescents. Note. a: Zero-order (r) and Partial (β) correlations represent different analytic approaches to the same underlying relationship. Zero-order correlations are simple bivariate associations without statistical control. Partial/standardized coefficients are from multivariate models controlling for additional variables (e.g., demographics, environmental attitudes). Both metrics are displayed on the same scale (correlation magnitude) for comparison. The non-significant interaction (p = 0.121) indicates these patterns are equivalent across metric types. k = number of effect sizes per group.

3.4.3. Study Design and Geography

Longitudinal studies (r = 0.282, p = 0.011) yielded numerically larger, though not significantly different, effect sizes compared to cross-sectional studies (r = 0.229). Effect sizes were statistically equivalent between Global North (r = 0.241) and Global South contexts (r = 0.241), although the confidence interval for Global South samples was substantially wider due to limited data.

3.5. Publication Bias Assessment

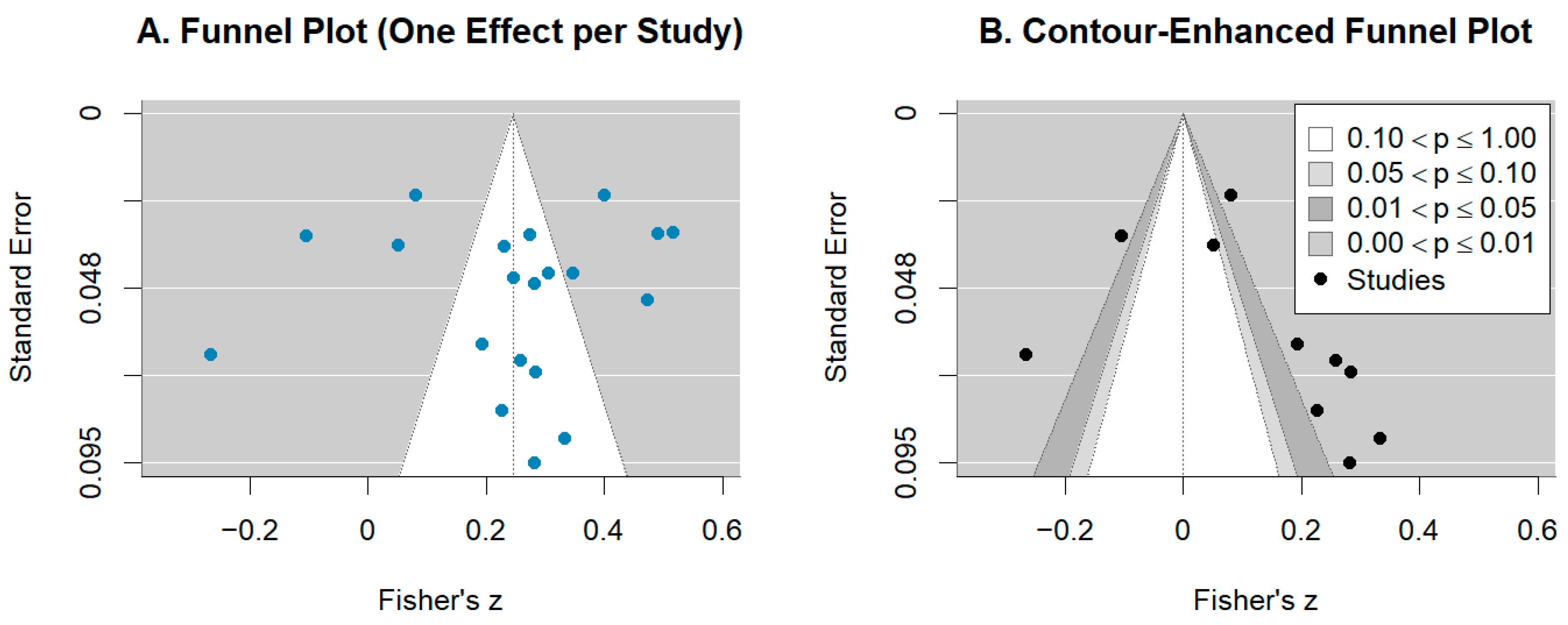

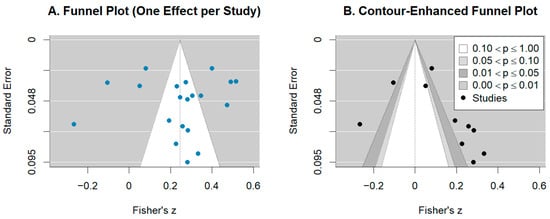

Potential publication bias was evaluated using both visual inspection of funnel plots and statistical tests. As shown in Figure 7A, the standard funnel plot displays a noticeable asymmetry, with a scarcity of small studies on the left side of the mean effect. This visual impression was statistically confirmed by Egger’s regression test (p = 0.021), indicating the presence of small-study effects.

Figure 7.

Funnel plots for publication bias assessment. Panel (A) displays the standard funnel plot, where each dot represents a study’s effect size (Fisher’s z) plotted against its standard error; the asymmetry suggests potential small-study effects. Panel (B) presents the contour-enhanced funnel plot, with shaded regions indicating levels of statistical significance: dark grey (p < 0.01), medium grey (p < 0.05), light grey (p < 0.10), and white (p > 0.10). The scarcity of studies in the white (non-significant) region supports the presence of publication bias.

To further investigate the source of this asymmetry, a contour-enhanced funnel plot was generated Figure 7B. This visualization overlays regions of statistical significance onto the funnel plot. The inspection reveals that “missing” studies are predominantly located in the non-significant regions (white area, p > 0.10). This pattern is consistent with classic publication bias, where smaller studies yielding non-significant results are less likely to be published. Consequently, while the aggregate effect size is robust, the magnitude of the effect may be slightly overestimated due to the selective reporting of significant findings.

However, the Trim-and-Fill analysis identified zero potentially missing studies, leaving the adjusted estimate identical to the original (r = 0.240). Similarly, the PET-PEESE correction yielded a bias-adjusted estimate of r = 0.239, remaining statistically significant.

Given the indications of asymmetry in the funnel plots, we conducted additional sensitivity analyses to probe the robustness of the findings. Rosenthal’s fail-safe N suggested that 5161 unpublished null studies would be required to reduce the overall effect to non-significance (overall p > 0.05). This corresponds to a tolerance ratio of approximately 258:1 relative to the number of observed studies, a value that far exceeds conventional critical thresholds and is difficult to reconcile with a trivial or purely artifactual association.

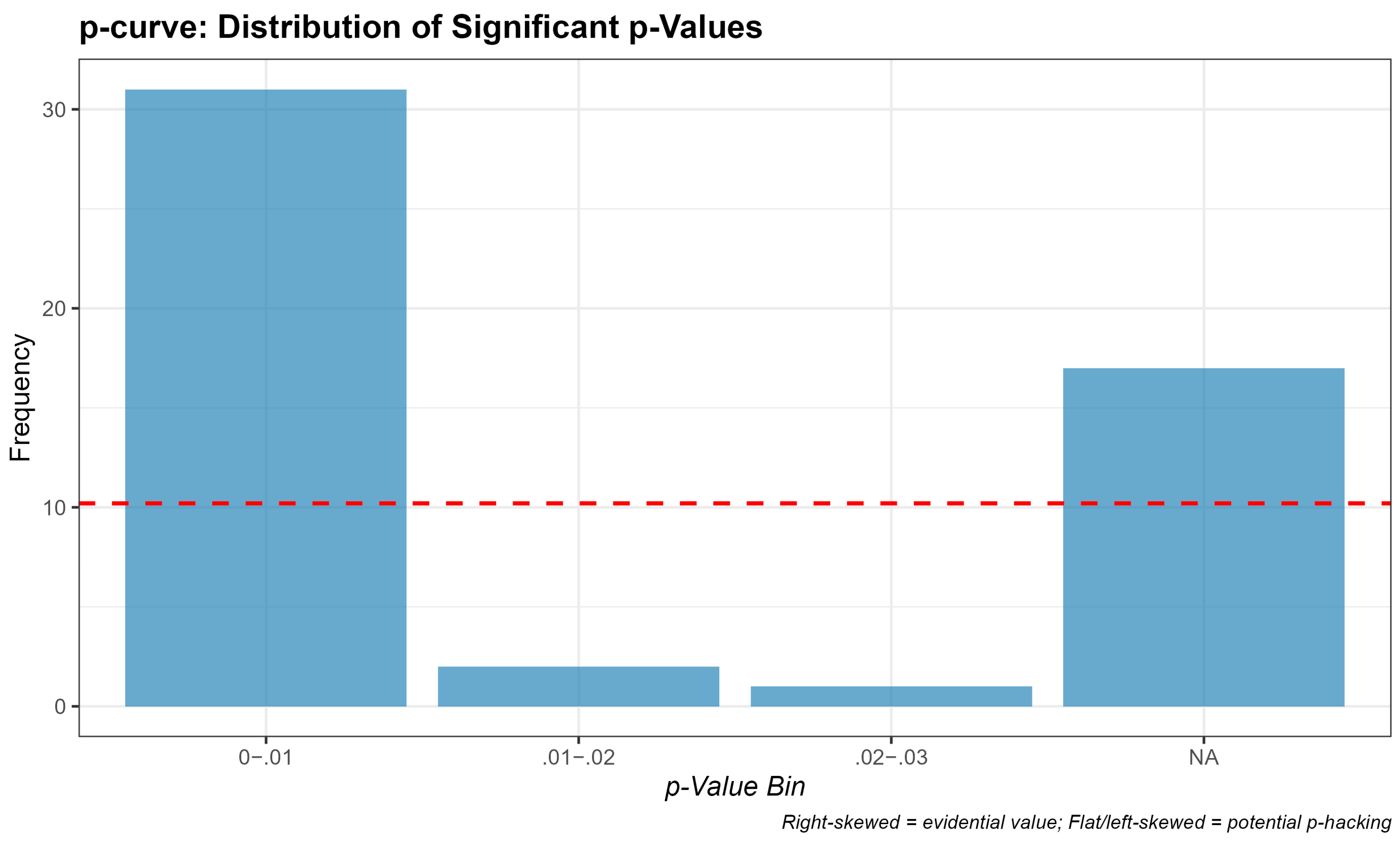

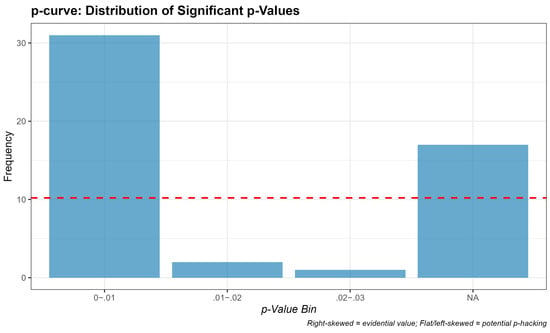

We also performed a p-curve analysis on the subset of statistically significant results (k = 51) to examine evidential value and the possibility of p-hacking. As illustrated in Figure 8, the distribution of p-values is clearly right-skewed, with the highest frequency in the p < 0.01 bin. Such a pattern is more consistent with a genuine underlying effect than with aggressive specification searching or selective reporting. Taken together, these diagnostics suggest that, although some degree of small-study effects cannot be entirely ruled out, the core association between eco-anxiety and pro-environmental behavior is likely to be robust and substantively meaningful rather than an artefact of publication bias.

Figure 8.

The histogram displays the distribution of statistically significant p-values (p < 0.05) extracted from the included studies. The red dashed line represents the expected distribution under the null hypothesis (uniform distribution). The observed distribution is strongly right-skewed (full blue bars), particularly in the p < 0.01 range, indicating the presence of evidential value rather than p-hacking (which would typically result in a left-skewed or flat distribution near 0.05).

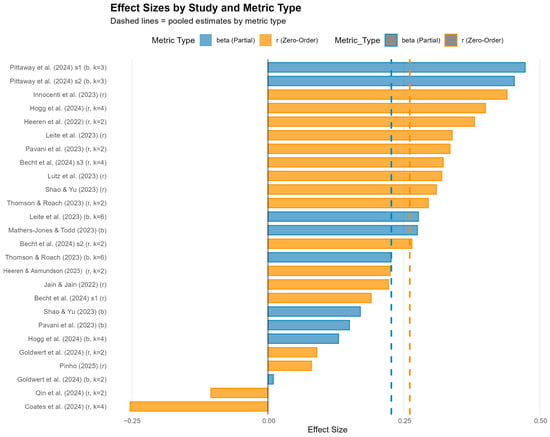

3.6. Within-Study Metric Comparison

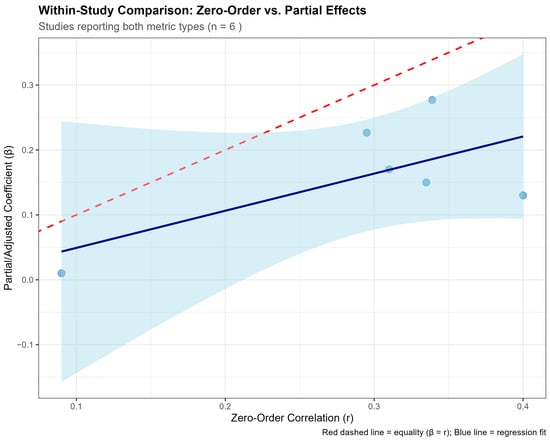

To rigorously assess whether the choice of metric introduced systematic bias, we focused on the subset of studies that reported both zero-order correlations and partial coefficients for the same sample (k = 6). This paired design allowed a direct comparison of effect sizes while holding sample characteristics constant. As illustrated in Figure 9, the meta-regression revealed no statistically significant difference between the two metric types, Qm(1) = 2.40, p = 0.121. Visually, the regression line (solid blue) lies slightly below the line of equality (dashed red), suggesting a minor tendency for covariate adjustment to attenuate the effect size. However, the 95% confidence bands broadly overlap the equality line, indicating that partial adjustment does not systematically inflate or deflate the eco-anxiety–PEB association relative to zero-order correlations.

Figure 9.

Scatter plot displaying paired effect sizes from the six studies that reported both metrics. The x-axis represents zero-order correlations (r), and the y-axis represents partial/adjusted coefficients (β). The red dashed line indicates perfect equality (y = x). The solid blue line represents the linear regression fit, with the shaded area indicating the 95% confidence interval. The overlap between the confidence region and the equality line supports the interchangeability of the metrics in this dataset.

3.7. Summary

In summary, this meta-analysis provides robust evidence for a small-to-moderate positive association between eco-anxiety and pro-environmental behavior. This relationship is significantly moderated by behavior type, with public/collective actions showing substantially stronger associations than private behaviors. Effects were robust across different measurement approaches and sensitivity analyses. The wide prediction interval underscores that the eco-anxiety–PEB relationship is highly context-dependent, with moderators accounting for meaningful variation in effect magnitude.

4. Discussion

Climate change represents one of the most pressing challenges of the 21st century, posing significant risks to ecosystems, human societies, and the global economy. Driven primarily by human activities such as fossil fuel combustion, deforestation, and industrial processes, it has led to rising global temperatures, more frequent and severe weather events, and disruptions to natural systems (Bhatti et al. 2024). Despite the concerning trajectory of climate change, evidence suggests that positive trends remain possible. For instance, using climate model simulations, (Iles et al. 2024) demonstrated that deep, rapid, and sustained reductions in greenhouse gas emissions could significantly slow global warming within two decades, with measurable improvements in atmospheric composition observable within just a few years. These findings underscore the importance of fostering behaviors and attitudes that support environmental sustainability, further highlighting the need to analyze how eco-anxiety can act as a catalyst for pro-environmental actions. While eco-anxiety has often been framed as a negative psychological burden, recent theoretical developments challenge a unidimensional view of such distress. Rather than inevitably undermining action, eco-anxiety could serve as an ‘activating emotion’, catalyzing pro-environmental responses when individuals perceive climate threats as relevant, personal and changeable, taking into account contextual variability, the limits of generalizability and high heterogeneity. Such a perspective aligns with emotion-theoretical models that see anxiety not merely as pathological, but also as a functional signal prompting coping or preparatory behavior in face of threat (Pavani et al. 2023).

Against a background of fragmented empirical findings, with some studies reporting negligible or negative associations between eco-anxiety and PEB, and others finding small-to-strong positive associations, the present meta-analysis sought to synthesize the evidence, estimate the overall effect size, and clarify boundary conditions (behavioral type, population, methodological factors), thereby testing the hypothesis that eco-anxiety, under many circumstances, functions as a meaningful predictor of PEB.

The meta-analysis revealed a small-to-moderate but consistently positive association between eco-anxiety and PEB (r = 0.24), statistically significant and robust across analytic approaches. Both zero-order correlations and partial regression coefficients yielded similar pooled estimates, with overlapping confidence intervals. This convergence suggests that the observed association is not merely an artifact of insufficient covariate control or confounding by general pro-environmental attitudes or socio-demographic variables. Indeed, in many cases, partial coefficients (i.e., effect sizes after adjusting for covariates) for private PEB were even slightly larger than zero-order correlations, indicating a possible suppression effect. Once broader attitudes or demographic predispositions are accounted for, the unique motivational contribution of eco-anxiety emerges more clearly.

4.1. Factors Influencing the Relationship Between Eco-Anxiety and PEBS

A key moderator of the association was the type of behavior. Public or collective behaviors, activism, policy engagement, advocacy, exhibited the strongest associations with eco-anxiety (r = 0.36), surpassing both private (e.g., household consumption, personal lifestyle changes) and general behaviors. This behavioral specificity carries important theoretical implications. Collective behaviors provide individuals with avenues for moral expression, social identity enactment, and a sense of group-based efficacy; they also make climate-related distress more meaningful by channeling it into socially visible, normatively valued action (Fielding and Hornsey 2016). In this light, eco-anxiety, as anticipatory, morally charged, and future-oriented distress, becomes especially mobilizing when structural and social affordances for collective action are available, enabling individuals to translate personal concern into systemic engagement. These dynamics mirror theoretical accounts from social psychology that emphasize the role of identity, moral norms, and collective efficacy in motivating activism. Conversely, private behaviors appear more weakly associated with eco-anxiety. Such behaviors tend to be more constrained by structural, economic, and habitual factors, making them less sensitive to emotional motivation. Nevertheless, the fact that partial coefficients for private PEB were often larger than zero-order correlations suggests that simple bivariate associations may underestimate the motivational role of eco-anxiety once competing predictors are controlled. In addition, it is important to note that the strong association between eco-anxiety and collective action may be partially explained by underlying third variables, such as environmental identity or collective efficacy, rather than anxiety acting as a sole driver. Combined with the substantial heterogeneity observed (I2 > 95%) and wide prediction intervals (−0.22 to 0.61), these findings should be viewed as a probability of action rather than a guaranteed outcome. For a significant minority of individuals or contexts, anxiety likely leads to paralysis rather than engagement. Future primary studies should employ structural equation modeling to disentangle the unique contribution of anxiety from these socio-cognitive factors. Population characteristics also moderated the strength of the eco-anxiety–PEB link. Adult samples demonstrated the most stable and robust positive effects, with close convergence between zero-order and adjusted estimates. By contrast, younger populations, adolescents or young adults (e.g., university students), presented more mixed and variable effects. For instance, in studies among adolescents, some found a negative or nonsignificant relationship between climate change anxiety and PEB, with additional mediating variables (e.g., future self-continuity, self-efficacy) playing a role (Hickman et al. 2021). Among young adults, eco-anxiety has been reported to motivate PEB and even promote well-being via behavioral mediation, but also to correlate with reduced life satisfaction and increased distress, highlighting a complex emotional outcome (Hickman et al. 2021). On the other hand, (Qin et al. 2024) found that adolescents who felt a strong connection to their future selves were more likely to engage in pro-environmental behaviors despite experiencing anxiety. In this vein, a critical gap emerged from our results regarding adolescent populations: despite moderate correlations, the complete absence of partial effect sizes (k = 0) prevented us from ruling out spurious relationships.

There is a small body of references connecting eco-anxiety with young people’s views on environmental sensitivity, environmental action, and climate change activism (D’Uggento et al. 2023; Parry et al. 2022; Bury et al. 2020).

Future research on youth must employ multivariate designs to isolate the specific contribution of eco-anxiety to pro-environmental behavior, independent of developmental or contextual confounders.

Research identifies several factors that may influence the relationship between eco-anxiety and pro-environmental behavior. (Pittaway et al. 2024) found that environmental cognitive alternatives can shape the connection between eco-anxiety and behavioral intentions. Specifically, perceiving climate change as a threat may prompt individuals to envision alternative realities in which society is structured to prevent environmental catastrophe. Their study examined two aspects of time orientation: consideration of future and immediate consequences. Results indicated that greater consideration of future consequences, coupled with lesser attention to immediate consequences, was associated with intentions to engage in conventional pro-environmental actions, both directly and indirectly via cognitive environmental alternatives. In contrast, consideration of future and immediate consequences was only indirectly related to intentions to engage in radical action. (Leite et al. 2023) highlighted the moderating roles of hope, despair, and perceived consequences of climate change in the relationship between climate change anxiety and pro-environmental behavior. Hope and perceived consequences were positively correlated with eco-anxiety, whereas despair showed a negative correlation. These findings suggest that lower levels of despair strengthen the relationship between eco-anxiety and pro-environmental behavior, while higher levels of hope similarly enhance this relationship. Furthermore, self-efficacy has been identified as a key mediator in this relationship (Innocenti et al. 2023). When eco-anxiety induces feelings of helplessness or hopelessness, individuals’ sense of capacity to effect meaningful change may be diminished, creating a barrier to engagement in pro-environmental behaviors. Reduced self-efficacy can produce a self-reinforcing cycle of distress and inaction, sometimes conceptualized as “eco-paralysis” or the limitations of green self-efficacy (Pihkala 2020; Stanley et al. 2021). Finally, Mathers-Jones and Todd (2023) demonstrated that attentional bias variability moderates the eco-anxiety–pro-environmental behavior relationship, emphasizing the role of cognitive processes in determining whether concern translates into action. These findings collectively indicate that eco-anxiety alone is not a sufficient predictor of pro-environmental behavior. Rather, its influence depends on the interplay of psychological resources (e.g., self-efficacy, hope, coping capacity), cognitive processes (e.g., attention, consideration of future consequences, environmental cognitive alternatives), and structural or social affordances. Eco-anxiety functions as a potentially activating emotion only when individuals possess the internal and external resources necessary to channel concern into constructive behavioral responses.

Taken together, these results support a theoretical reframing of eco-anxiety not as uniformly debilitating, but as a potentially adaptive, context-sensitive emotional driver. This view aligns with broader emotion theory that distinguishes functional from dysfunctional distress and emphasizes the role of context, coping capacity, and social structure in shaping outcomes (Crandon et al. 2024).

In summary, our study makes an innovative contribution by quantitatively synthesizing the evidence on the link between eco-anxiety and pro-environmental behavior, while also exploring key moderators that influence this association. This approach clarifies inconsistencies observed in individual studies and highlights factors that can either enhance or hinder the behavioral impact of eco-anxiety. These insights provide a solid empirical foundation for designing targeted interventions and policies that account for the psychological dimensions of climate change.

4.2. Practical Implications

The implications for clinical practice and research are significant. From a clinical perspective, identifying the levels of eco-anxiety and the factors that moderate pro-environmental behavior is crucial for effective intervention.

These findings further carry significant implications for environmental communication, public policy, mental health and climate engagement interventions. First, communication strategies might benefit from acknowledging eco-anxiety as a legitimate emotional response rather than pathologizing it. Framing climate concern as a rational, morally situated anxiety may validate individuals’ feelings and encourage engagement rather than avoidance. In contexts where collective behaviors offer meaningful outlets, messages could emphasize social identity, community involvement, political efficacy, and collective agency. This may harness eco-anxiety’s motivational potential and channel it into systemic action. Even among people who are similar to each other, there are individual variables that influence whether they are active or passive. These include personality traits, subjective motivations, family culture and specific life events.

Second, private pro-environmental behaviors, such as sustainable consumption, energy saving, and recycling, may not respond robustly to emotional appeals alone. Given their weaker associations with eco-anxiety, effective interventions here may need to address structural and material constraints: improving accessibility, affordability, infrastructure, and convenience. Relying solely on emotional motivators may prove insufficient.

Third, in educational or clinical contexts, eco-emotional literacy might be incorporated: helping individuals transform distress into agency, fostering coping strategies (e.g., social support, collective engagement), and supporting identity formation around climate-relevant values. The various dimensions of eco-anxiety, including rumination, personal impact and functional impairment, can be alleviated with the help of psychological support. In particular, psychotherapy interventions involving various approaches and models (Davì et al. 2024) can enhance psychological well-being when there is an appropriate therapeutic response.

For younger populations, adolescents and young adults, creating structured opportunities for collective involvement (e.g., school-based climate clubs, community engagement, youth assemblies) may be particularly beneficial to prevent eco-anxiety from culminating in disengagement or despair.

Fourth, mental health practitioners and policymakers should pay attention to the dual nature of eco-anxiety: as a psychological burden and as a potential catalyst for positive change. Interventions might aim not to eliminate eco-anxiety per se, but to provide pathways for constructive expression and coping. Developing skills related to self-awareness and body awareness could be useful, as this would motivate action (Cannavò et al. 2025).

4.3. Limitations

The primary limitation of the present study is the exclusion of research exploring other emotions related to the construct of eco-anxiety, which could have provided a more comprehensive understanding of the relationship between climate change experiences and pro-environmental behavior. Although these tools are not yet widely used, they may offer valuable insights for future research. Additionally, the small number of selected studies is another constraint, underscoring the need for further research to better understand how eco-anxiety influences pro-environmental behavior. Further exploration of these areas is necessary to fully understand the relationship between eco-anxiety and pro-environmental behavior. This meta-analysis also has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. First, most of the included studies used cross-sectional designs, which limit the ability to establish causal relationships between climate anxiety and pro-environmental behaviors. Future research should employ longitudinal designs to examine how climate anxiety and pro-environmental behaviors influence each other over time. Second, most studies relied on self-report measures of both climate anxiety and pro-environmental behaviors, which may be subject to social desirability bias or other response biases. Future research should incorporate objective measures of pro-environmental behaviors or experimental designs to address this limitation. Third, the meta-analysis focused on the linear relationship between climate anxiety and pro-environmental behaviors, but some studies have suggested a potential non-linear relationship (Coates et al. 2024). Future research should explore this possibility in more detail, examining whether moderate levels of climate anxiety are indeed more effective in promoting pro-environmental behaviors than very low or very high levels. As research on climate anxiety and pro-environmental behaviors continues to grow, future meta-analyses should include a larger and more diverse set of studies. Fourth, the lack of data from the Global North is a limitation of the research. Generally speaking, more data on eco-anxiety is available in the Global North because academic research and surveys tend to focus on regions where awareness of, and public debate surrounding, climate change are more developed. Finally, the meta-analysis focused on the relationship between climate anxiety and pro-environmental behaviors, but did not fully explore the role of potential mediators or moderators of this relationship. Future research should explore additional factors that may influence this relationship, such as coping strategies, efficacy beliefs, social norms, or political orientation.

4.4. Future Directions

Given these limitations, future research should aim to deepen and refine our understanding of eco-anxiety and its behavioral consequences. First, longitudinal and experimental designs are crucial to disentangle causality and temporal dynamics: does eco-anxiety predict sustained behavior over time, or is the association transient and context-dependent? Second, research should expand into underrepresented populations, particularly in Global South and climate-vulnerable regions, as well as among socio-economically disadvantaged groups, to assess whether the adaptive potential of eco-anxiety holds across diverse cultural and structural contexts. Third, future studies should systematically examine mediators (e.g., coping strategies, social support, perceived collective efficacy, identity processes, moral emotions) and moderators (e.g., self-efficacy, socio-economic constraints, policy and infrastructure context, cultural values) that shape whether eco-anxiety leads to action or paralysis. Fourth, interdisciplinary research combining psychological, sociological, and policy perspectives could elucidate how structural factors (economic opportunity, policy frameworks, social inequality) interact with psychological variables to facilitate or hinder behavior. Finally, intervention studies, in educational, community, or clinical settings, could test whether eco-emotional literacy, collective engagement programs, social support networks, or self-efficacy training can channel eco-anxiety into sustainable engagement without exacerbating psychological distress.

5. Conclusions

In sum, the present meta-analysis provides compelling evidence that eco-anxiety is a meaningful, reliable, and theoretically coherent predictor of pro-environmental behavior. Although the average effect is modest, its consistency across methodologies, the convergence between zero-order and adjusted estimates, and the strong associations for public and collective behaviors underscore the potential of eco-anxiety as an emotional engine of engagement. Far from being uniformly debilitating, eco-anxiety—under appropriate psychological, social, and structural conditions—can motivate individuals toward meaningful environmental action. The findings support a paradigm shift: rather than treating eco-anxiety purely as a psychological burden to be alleviated, it may be more accurate and useful to understand it as an adaptive, context-sensitive response that can catalyze behaviors essential for societal transformation. Recognizing and harnessing this potential, while mitigating the risks of distress and paralysis, may prove crucial for fostering climate engagement at both the individual and collective level.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.D., C.L.D. and F.M.; methodology, D.D. and F.M.; software, F.M.; validation, FM., D.D. and C.L.D.; formal analysis, F.M. and D.D.; data curation, F.M.; writing—original draft preparation, D.D.; writing—review and editing, D.D. and C.L.D. supervision, C.L.D.; funding acquisition, D.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Albrecht, Glenn. 2011. Chronic Environmental Change: Emerging ‘Psychoterratic’ Syndromes. In Climate Change and Human Well-Being, a cura di Inka Weissbecker. International and Cultural Psychology. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anneser, Elyssa, Peter Levine, Kevin J. Lane, and Laura Corlin. 2024. Climate Stress and Anxiety, Environmental Context, and Civic Engagement: A Nationally Representative Study. Journal of Environmental Psychology 93: 102220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ágoston, Csilla, Benedek Csaba, Bence Nagy, Zoltán Kőváry, Andrea Dúll, József Rácz, and Zsolt Demetrovics. 2022. Identifying types of eco-anxiety, eco-guilt, eco-grief, and eco-coping in a climate-sensitive population: A qualitative study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19: 2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakul, Fariea, Eamin Zahan Heanoy, Antara Das Antu, Faria Khandakar, and Shahin Ahmed. 2025. Assessing the relationship between climate change anxiety, ecological coping, and pro-environmental behavior: Evidence from Gen Z Bangladeshis. Acta Psychologica 254: 104847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balduzzi, Sara, Gerta Rücker, and Guido Schwarzer. 2019. How to Perform a Meta-Analysis with R: A Practical Tutorial. Evidence Based Mental Health 22: 153–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, Sebastian, Jonas Rees, and Sebastian Seebauer. 2015. Collective Climate Action: Determinants of Participation Intention in Community-Based pro-Environmental Initiatives. Journal of Environmental Psychology 43: 155–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banwell, Nicola, and Nadja Eggert. 2024. Rethinking Ecoanxiety through Environmental Moral Distress: An Ethics Reflection. The Journal of Climate Change and Health 15: 100283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becht, Andrik, Jenna Spitzer, Stathis Grapsas, Judith van de Wetering, Astrid Poorthuis, Anouk Smeekes, and Sander Thomaes. 2024. Feeling Anxious and Being Engaged in a Warming World: Climate Anxiety and Adolescents’ Pro-environmental Behavior. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 65: 1270–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatti, Uzair Aslam, Mughair Aslam Bhatti, Hao Tang, M. S. Syam, Emad Mahrous Awwad, Mohamed Sharaf, and Yazeed Yasin Ghadi. 2024. Global Production Patterns: Understanding the Relationship between Greenhouse Gas Emissions, Agriculture Greening and Climate Variability. Environmental Research 245: 118049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bury, Simon M., Michael Wenzel, and Lydia Woodyatt. 2020. Against the odds: Hope as an antecedent of support for climate change action. The British Journal of Social Psychology 59: 289–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cannavò, Michele, Dario Davì, and Brenda Cervellione. 2025. Gestalt Therapy and Somatic Symptom Disorder: Clinical Reflections on Embodiment, Contact, and Relational Field. The Journal of Humanistic Counseling. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, Joshua M., John Foley, and Lin Fang. 2024. Climate Change on the Brain: Neural Correlates of Climate Anxiety. Journal of Anxiety Disorders 103: 102848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlson, Fiona, Suhailah Ali, Tarik Benmarhnia, Madeleine Pearl, Alessandro Massazza, Jura Augustinavicius, and James G. Scott. 2021. Climate Change and Mental Health: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18: 4486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, Mike W.-L. 2014. Modeling dependent effect sizes with three-level meta-analyses: A structural equation modeling approach. Psychological Methods 19: 211–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cianconi, Paolo, Batul Hanife, Francesco Grillo, Sophia Betro’, Cokorda Bagus Jaya Lesmana, and Luigi Janiri. 2023. Eco-emotions and Psychoterratic Syndromes: Reshaping Mental HealthAssessment Under Climate Change. The Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine 96: 211–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clayton, Susan. 2020. Climate anxiety: Psychological responses to climate change. Journal of Anxiety Disorders 74: 102263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, Susan, Christie Manning, Kirra Krygsman, and Meighen Speiser. 2017. Mental Health and Our Changing Climate: Impacts, Implications, and Guidance. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, and ecoAmerica. Available online: https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/2017/03/mental-health-climate.pdf (accessed on 24 January 2026).

- Coates, Zac, Michelle Kelly, and Scott Brown. 2024. The Relationship between Climate Anxiety and Pro-Environment Behaviours. Sustainability 16: 5211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffey, Yumiko, Navjot Bhullar, Joanne Durkin, Md Shahidul Islam, and Kim Usher. 2021. Understanding Eco-Anxiety: A Systematic Scoping Review of Current Literature and Identified Knowledge Gaps. The Journal of Climate Change and Health 3: 100047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Jacob. 1988. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc., p. 19. [Google Scholar]

- Contreras, Alba, M. Annelise Blanchard, Camille Mouguiama-Daouda, and Alexandre Heeren. 2024. When Eco-Anger (but Not Eco-Anxiety nor Eco-Sadness) Makes You Change! A Temporal Network Approach to the Emotional Experience of Climate Change. Journal of Anxiety Disorders 102: 102822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crandon, Tara J., James G. Scott, Fiona J. Charlson, and Hannah J. Thomas. 2024. A theoretical model of climate anxiety and coping. Discover Psychology 4: 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davì, Dario, Claudia Prestano, and Nicoletta Vegni. 2024. Exploring therapeutic responsiveness: A comparative textual analysis across different models. Frontiers in Psychology 15: 1412220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Uggento, Angela Maria, Alfonso Piscitelli, Nunziata Ribecco, and Germana Scepi. 2023. Perceived climate change risk and global green activism among young people. Statistical Methods & Applications 32: 1167–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fielding, Kelly S., and Matthew J. Hornsey. 2016. A Social Identity Analysis of Climate Change and Environmental Attitudes and Behaviors: Insights and Opportunities. Frontiers in Psychology 7: 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawrych, Magdalena. 2022. Climate change and mental health: A review of current literature. Psychiatria Polska 56: 903–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldwert, Danielle, Kimberly C. Doell, Jay J. Van Bavel, and Madalina Vlasceanu. 2024. Climate change terminology does not influence willingness to take climate action. Journal of Environmental Psychology 100: 102482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamann, Karen R. S., and Gerhard Reese. 2020. My Influence on the World (of Others): Goal Efficacy Beliefs and Efficacy Affect Predict Private, Public, and Activist Pro-environmental Behavior. Journal of Social Issues 76: 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heeren, Alexandre, and Gordon J. G. Asmundson. 2023. Understanding climate anxiety: What decision-makers, health care providers, and the mental health community need to know to promote adaptative coping. Journal of Anxiety Disorders 93: 102654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heeren, Alexandre, Camille Mouguiama-Daouda, and Alba Contreras. 2022. On Climate Anxiety and the Threat It May Pose to Daily Life Functioning and Adaptation: A Study among European and African French-Speaking Participants. Climatic Change 173: 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hickman, Caroline, Elizabeth Marks, Panu Pihkala, Susan Clayton, R Eric Lewandowski, Elouise E Mayall, Britt Wray, Catriona Mellor, and Lise van Susteren. 2021. Climate Anxiety in Children and Young People and Their Beliefs about Government Responses to Climate Change: A Global Survey. The Lancet Planetary Health 5: e863–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, Julian P. T., Simon G. Thompson, Jonathan J. Deeks, and Douglas G. Altman. 2003. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. bmj 327: 557–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, Teaghan L., Samantha K. Stanley, Léan V. O’Brien, Clare R. Watsford, and Iain Walker. 2024. Clarifying the Nature of the Association between Eco-Anxiety, Wellbeing and pro-Environmental Behaviour. Journal of Environmental Psychology 95: 102249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iles, Carley E., Bjørn H. Samset, Marit Sandstad, Nina Schuhen, Laura J. Wilcox, and Marianne T. Lund. 2024. Strong Regional Trends in Extreme Weather over the next Two Decades under High- and Low-Emissions Pathways. Nature Geoscience 17: 845–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innocenti, Matteo, Gabriele Santarelli, Gaia Surya Lombardi, Lorenzo Ciabini, Doris Zjalic, Mattia Di Russo, and Chiara Cadeddu. 2023. How can climate change anxiety induce both pro-environmental behaviours and eco-paralysis? The mediating role of general self-efficacy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20: 3085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]