Abstract

Past literature on mental health has extensively discussed the effect of interpersonal relationships on mental health, but studies have yet to systematically investigate the meaning and influence of group membership. This study thereby focuses on the influence of group membership that individuals form through private groups on mental health. We particularly explore the possibility that the positive influence of the number of memberships on mental conditions turns negative when individuals suffer from excessive obligations and requirements from the groups they engage. Using data from the 2023 Korea Social Integration Survey, results from ordered logistic regression analyses suggest that the relationship between group membership and mental distress shows a U-shape. While one’s membership in private groups is negatively associated with anxiety, depressive symptoms, and suicidal thoughts even after controlling for interpersonal contact network as well as other socio-demographic characteristics, the association becomes positive when one engages in an excessive number of groups. Furthermore, we find this U-shape relationship to be significant only in urban communities, not smaller local communities. Our study provides implications for understanding how and under which social conditions membership in social groups shape one’s mental health.

1. Introduction

How are mental health conditions influenced by the social relationships individuals form through group membership? Previous literature on mental health has suggested that interpersonal networks established with others play a critical role in enhancing one’s mental health (Kawachi and Berkman 2001; Thoits 2011; Wickramaratne et al. 2022). It is a well-established finding that those who maintain regular contact and social interaction with others tend to exhibit lower levels of depression and suicidal ideation (Berkman et al. 2000; Cohen and Janicki-Deverts 2009; Cornwell and Waite 2009; Ertel et al. 2009; Lin et al. 1999; Umberson and Montez 2010). More recently, however, scholars have begun to examine the darker side of interpersonal networks by focusing on how excessive social relationships can lead to increased social stress and aggravate mental health problems (Song et al. 2021; Villalonga-Olives and Kawachi 2017).

While past research has extensively discussed the influence of interpersonal relationships on mental health, the role of the social networks one forms through groups should be distinguished from that of interpersonal networks. Individuals participate in and commit to various types of organizations, including community or religious associations, private clubs related to cultural activities, and professional or alumni associations. Social relationships formed through membership in groups have distinct characteristics in two important respects. First, the relationships one establishes through social groups represent a unique combination of strong and weak ties that do not necessarily translate into dyadic relationships (Breiger 1974; Feld 1981; McPherson 1983). Members affiliated with the same social group may form a distinctive type of relationship that exists only within the group. Second, the duality between groups and members should be considered when examining group membership (Brashears et al. 2017; Breiger 1974). Social groups are sustained by the ongoing efforts of organizers and provide a sense of belonging to their members. While interpersonal networks can be dissolved by the absence of either individual, social groups persist among members despite turnover in their membership and dissolve only when the group itself is disbanded (Cornwell and Waite 2009).

Social groups in local communities are identified as a critical source of social capital (McPherson et al. 2006; Sampson et al. 2002). As these groups provide a conducive environment for interaction, the presence of numerous social groups is often seen as a sign of a healthy and vibrant community (Bourdieu 1986; Putnam 1995; Verba et al. 1995). Empirical studies have shown that individuals living in communities with high levels of social capital are more likely to trust each other, engage in volunteering, pay attention to civic matters, and report higher levels of happiness (Driskell et al. 2008; Lim and MacGregor 2012; Putnam 1995, 2000; Suh et al. 2012; Verba et al. 1995). In relation to social relationships formed through such groups, previous studies have suggested that individuals who belong to social groups tend to have better mental health due to an enhanced sense of belonging (Cornwell and Waite 2009; Lim and Putnam 2010; Thoits and Hewitt 2001; Umberson and Montez 2010).

While recent research has highlighted the positive relationship between group membership and mental health, the literature has yet to examine whether group membership exerts an unexpected negative effect on mental health distress. Group membership may enhance mental health by providing access to resources, useful information, and emotional support from others who share common affiliations (Cornwell and Waite 2009; Thoits and Hewitt 2001; Umberson and Montez 2010), but at the same time, multiple group affiliations may deteriorate mental health by giving feelings of overwhelming obligation and emotional exhaustion due to potential intragroup conflicts (Suh et al. 2023). Therefore, extending the literature on interpersonal relationships, this study explores the possibility that excessive social relationships through group membership may lead to greater social stress and mental health problems. We define excessive membership not simply in terms of the amount of time devoted, but rather as a situation in which individuals feel compelled to devote time to organizational participation due to external group pressure, despite doing so reluctantly.

Additionally, we consider the size of local communities in our analysis of multiple group affiliations. By distinguishing between urban and local communities, we investigate whether the curvilinear relationship between the number of group memberships and mental health issues is particularly salient in urban areas with high population density. Our rationale is that the social stress and obligations associated with group participation may be salient for individuals living in urban communities having larger and more complex social groups (Fischer 1982; Simmel [1903] 2016; Wellman 1979). In urban settings, membership in larger social groups may intensify perceived social stress due to increased status competition and potential interpersonal conflict, relative to the experience within smaller, local groups.

We select South Korea as an empirical case to test our theoretical expectations regarding the influence of group membership. South Korea has experienced rapid industrialization and democratization over the past few decades (Woo-Cumings 1999). During this time, the gap between metropolitan areas such as Seoul and other local areas has widened in terms of both economic development and population size (Kim and Han 2012). Due to the larger size of social groups and the potential for status competition among members in urban areas, South Korea provides an ideal case to examine whether group membership follows a U-shaped relationship with mental health problems, particularly in urban communities.

We use data from the 2023 Korea Social Integration Survey due to its comprehensive coverage of both urban and rural populations based on stratified sampling design (Korea Institute of Public Administration 2023). The dataset contains a comprehensive set of survey items, including a series of questions on mental health conditions, interpersonal networks, group membership, and other socio-demographic attributes, including information on residential location. Compared to objective measures, social surveys have both advantages and limitations. Surveys are appropriate for capturing subjective states such as perceived psychological distress and well-being. These self-reported responses are related to one’s experiences and not measurable through clinical records. At the same time, however, it is true that survey-based measures are susceptible to reporting biases and that these measures are not validated through external, behavioral measures.

To estimate mental health problems in a comprehensive manner, we consider both less severe issues such as anxiety and more severe forms of mental distress, including depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation. Results from ordered logistic regression analyses suggest that the association between group membership and mental distress is indeed U-shaped. While one’s membership in private social groups is negatively associated with anxiety, depressive symptoms, and suicidal thoughts even after controlling for interpersonal contact network as well as other socio-demographic characteristics, the association becomes positive when one engages in an excessive number of groups. Furthermore, we find this U-shape relationship to be significant only in metropolitan cities, not in smaller cities, towns, or villages. Our study provides a nuanced understanding both on the curvilinear relationship between group membership and mental health and on the social conditions under which this association becomes salient. In conclusion, we discuss the theoretical implications that our study provides for social networks and mental health.

2. Theoretical Backgrounds

2.1. Interpersonal Networks and Mental Health

In contemporary societies, individuals seek to overcome personal difficulties through the social relationships they form with others. People receive social and emotional support from others through sustained interpersonal contacts. Family members as well as intimate friends serve as a buttress for those in personal crises (Coleman 1988; Lin 2001). In addition, individuals obtain necessary resources and nascent information from those who are not necessarily close to them (Granovetter 1973). Relying on their social relationships, individuals also avoid the penalties and disadvantages they may incur from being isolated from others (Chappell and Badger 1989).

Past literature on mental health has long discussed the effect of interpersonal relationships on mental health. Empirical studies have identified interpersonal networks as a critical factor to enhance mental health (Smith and Christakis 2008; Kawachi and Berkman 2001; Thoits 2011; Wickramaratne et al. 2022). The social and emotional support one receives from others is known to decrease one’s level of depression and deter suicidal thoughts and behaviors from escalating (Berkman et al. 2000; Cohen and Janicki-Deverts 2009; Cornwell and Waite 2009; Ertel et al. 2009; Lin et al. 1999; Umberson and Montez 2010).

In the past decades, however, social network studies have begun to illuminate the dark side of social relationships. While individuals formulate social networks to avoid isolation, empirical studies have suggested that maintaining excessive social relationships unintentionally enhances mental distress (Song et al. 2021; Umberson and Montez 2010; Villalonga-Olives and Kawachi 2017). These studies have noted that the social stress that individuals feel by maintaining too many relationships can lead to higher levels of mental health problems (Falci and McNeely 2009; Portes 1998; Qu 2024). Therefore, the social network literature has begun to focus on the likelihood that the effect of interpersonal networks on mental health conditions is not linear but rather curvilinear (Maier et al. 2015).

2.2. Group Membership and Mental Health

In addition to interpersonal relationships, social groups present a conducive milieu for interacting with others and maintaining interpersonal relationships (Bourdieu 1986; Putnam 2000). By belonging to groups, individuals establish affiliation networks with other group members and, thereby, receive social support and develop a sense of belonging (Umberson and Montez 2010). The affiliation networks that one forms through group membership cannot simply translate into direct relationships between individuals since those networks with other group members may only be maintained within groups (Brashears et al. 2017; Breiger 1974). Without establishing an intimate interpersonal relationship with others, members of a common group can maintain a unique type of strong or weak relationship under the group (Feld 1981; McPherson 1983; Suh et al. 2016).

Regarding affiliation to social groups, previous studies have noted that one’s group membership has a positive impact on an individual’s mental health conditions. These studies have suggested that individual engagement with social groups can improve one’s mental health by enhancing one’s sense of belonging (Jung 2014; Lim and Putnam 2010). Moreover, at the community level, past literature has emphasized that various forms of civic and religious associations can enhance the level of social capital in communities (Putnam 1995, 2000). By participating in these associations, individuals can enhance their trust in others, form greater interest in local affairs, build a stronger sense of community, and feel a higher level of happiness (Driskell et al. 2008; Lim and MacGregor 2012; Putnam 1995, 2000; Verba et al. 1995).

While the previous literature on mental health has extensively discussed the effect of interpersonal relationships, empirical studies have yet to systematically investigate the influence of group membership. Studies are yet to examine whether the effect of social group membership is linear or curvilinear. To expand our understanding on membership, this study focuses on the number of memberships that individuals hold through private groups on their mental health conditions.

2.3. Theoretical Model and Hypotheses

The social networks literature has recently revealed a U-shaped relationship between interpersonal networks and mental distress, but little attention has been paid to the potential curvilinear effects of group membership. This study explores the possibility that although group membership can protect against mental health distress, an excessive number of group affiliations may instead be detrimental to mental well-being. We posit that individuals generally benefit from social relationships established through group memberships. These networks provide access to resources, useful information, and emotional support from others who share common affiliations. Mental health may be enhanced not only through direct support but also through the sense of belonging fostered by group participation (Cornwell and Waite 2009; Thoits and Hewitt 2001; Umberson and Montez 2010). Accordingly, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1.

The number of group memberships is negatively associated with mental health distress.

At the same time, however, we draw attention to the potential dark side of group membership by examining how an excessive number of group memberships may harm mental health. As individuals participate in multiple social groups, the social stress they experience may offset—and even outweigh—the emotional and instrumental support they receive. Multiple group affiliations can lead to feelings of overwhelming obligation and unmanageable demands. Also, individuals may experience emotional exhaustion due to status competition and potential intragroup conflicts (Suh et al. 2023). Moreover, such pressures are often inescapable, especially when individuals occupy meaningful or central roles within these groups. Therefore, we hypothesize as follows:

Hypothesis 2.

An excessive number of group memberships is positively associated with mental health distress.

While the combination of Hypotheses 1 and 2 underpins our theoretical expectation of a U-shaped relationship between group membership and mental health problems, we further examine the local conditions under which this curvilinear association becomes salient. Specifically, we differentiate between urban and rural communities, based on the premise that the dynamics of social group involvement may vary across distinct local contexts (Simmel [1903] 2016). Social groups in urban areas tend to be larger and more complex than those in rural communities (Fischer 1975, 1982; Wellman 1979). Consequently, individuals residing in densely populated urban settings may experience heightened social stress and obligations associated with group participation. In particular, intensified status competition and a higher likelihood of intragroup conflict within urban groups may amplify perceived social stress, especially when compared to the relatively smaller and more cohesive groups typically found in rural contexts. Accordingly, we propose as follows:

Hypothesis 3.

The curvilinear effect of group membership on mental health distress is more salient in urban communities relative to rural communities.

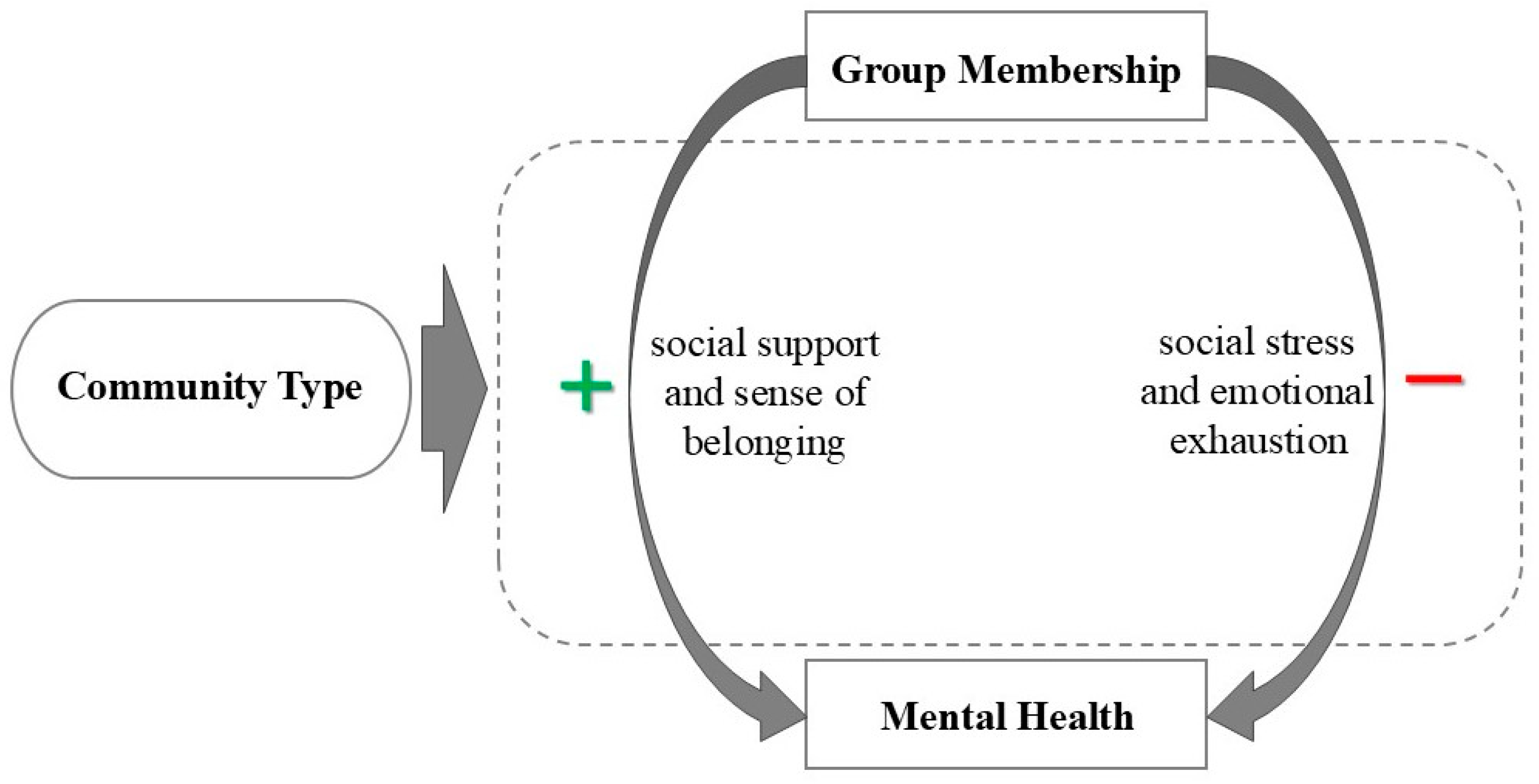

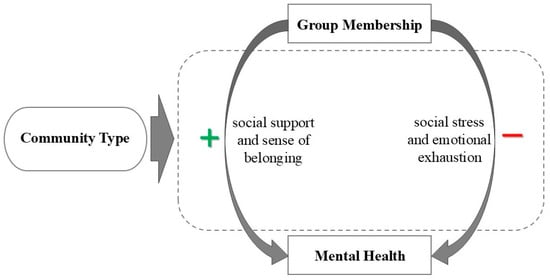

Figure 1 presents the theoretical model linking group membership, community type, and mental health, from which the three hypotheses are derived.

Figure 1.

Theoretical model on group membership, community type, and mental health.

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Data

We chose South Korea as an empirical case to test our theoretical expectations related to the effect of group membership. While South Korea has experienced rapid successful industrialization in the last few decades, the gap between metropolitan areas and other localized areas has widened in terms of economic development. Due to the high population density in metropolitan cities, social groups in those cities, such as Seoul, are known to be large in size and more complex in their structure compared to groups located in smaller cities, towns, or villages (Kim and Han 2012). Accordingly, the potential for status competition and intragroup conflict is also greater among members in urban areas in contrast to local areas. Therefore, we believe that South Korea is an ideal case to test the relationship between social group membership and mental health problems.

Among various social surveys conducted in South Korea, this study utilizes data from the 2023 Korea Social Integration Survey (KSIS). Administered by the Korea Institute of Public Administration (KIPA), a government-affiliated research institution, the KSIS is a nationally representative dataset targeting South Korean citizens aged 19 and older residing within the country (Korea Institute of Public Administration 2023). The survey employs a stratified two-stage probability sampling method, ensuring population representativeness across key regional and demographic strata. Data were collected through face-to-face interviews, excluding individuals requiring self-administered questionnaires. A total of 8221 respondents participated in the survey, all of whom are included in our analysis.

We draw on the KSIS for its methodological rigor and comprehensive coverage of both urban and rural populations, made possible through its stratified sampling design. The dataset contains rich information on respondents’ membership in social groups, interpersonal contact networks, mental health conditions, subjective wellbeing, and a range of socio-demographic variables. Notably, it captures multiple dimensions of mental health, including self-reported levels of anxiety, depressive symptoms, loneliness, suicidal ideation, happiness, and life satisfaction. Self-reported mental health measures have both strengths and limitations. Although self-reported measures may understate mental distress and are susceptible to individual reporting biases, they nonetheless capture individuals’ subjective experiences and perceived anxiety, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation. The data also include detailed measures of social networks, encompassing both interpersonal contact networks with others and social relationships based on group membership.

The dependent variables used to assess mental health distress are levels of anxiety, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation. Together, these variables capture both minor and severe mental health problems. Anxiety and depressive symptoms were measured on 11-point scales in response to the following questions: “To what extent did you feel anxious yesterday?” and “To what extent did you feel depressed yesterday?” Response options ranged from 0 (“not at all”) to 10 (“very much”), with higher scores indicating greater levels of anxiety or depression. Suicidal ideation was assessed with the item: “How do you respond to the statement, ‘I sometimes have thoughts of wanting to end my life’?” Responses were measured on a 4-point scale from 0 (“not at all”) to 3 (“very much”). To address the limitations of cross-sectional data, all dependent variables are time-bounded in their reference period.

The main independent variable captures the number of social groups in which respondents actively participate. Group membership was operationalized as the number of private groups in which respondents reported active involvement. In the survey question on social group participation, respondents were originally asked whether they were active in the group, held membership without meaningful participation, or were not members at all. We recoded this variable by combining latent membership and no membership into a single category, “no membership.”

Private groups included religious organizations, private clubs (e.g., sports, leisure, and cultural activities), community or civic associations, alumni associations, and volunteer groups. Regarding the causal mechanisms behind the relationship between group membership and mental distress, we relied on a membership-count measure due to data limitations, but additional information on the intensity of participation in various groups across multiple organizations may serve as another important measure to test our mechanisms.

A key control variable is the size of respondents’ interpersonal contact networks. This was measured as an ordinal variable reflecting the number of non-family members with whom respondents typically have contact on a weekday. Contact was defined as personal interaction—face-to-face or via telephone, text message, online platforms, postal mail, or other means. Response categories were: none (0), 1–2 persons (1), 3–4 persons (2), 5–9 persons (3), 10–19 persons (4), and 20 or more persons (5). In the analytical models, this variable was treated as continuous. In addition, an important contextual variable in our study is community type. The operationalization of community type is based on administrative regions. After the respondents self-reported their full residential addresses, the urban/rural community indicators were coded by the survey team based on these addresses.

Additional control variables included socio-demographic attributes, health condition, and generalized social trust. Socio-demographic controls added to the models were age (in years), biological sex at birth (1 = female), one’s level of education (1 = elementary school or less to 4 = college or higher), household income (1 = less than 1 million KRW to 7 = 600 million KRW or more), and one’s marital status (1 = married or living with spouse). In addition, we included individuals’ self-rated physical health, as it is closely linked to mental health. This variable was measured on a 5-point scale from 1 (“very bad”) to 5 (“very good”) to test whether group membership remained significant after accounting for self-reported health. Also, marital status is included given the well-established role of spousal relationships as a key social resource influencing mental health (Dehle et al. 2001). Finally, generalized interpersonal trust was measured by the question: “Generally speaking, how much do you think people can be trusted?” with responses ranging from 0 (“not at all”) to 3 (“very much”), given its documented associations with both mental health and social networks (Ferlander 2007; Uslaner 2002; Wang et al. 2009). Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for all dependent, independent, and control variables.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the variables (N = 8221).

3.2. Analytic Strategy

Highlighting both the benefits and drawbacks of social networks, this study investigates the curvilinear relationship between social networks and mental health, with a particular focus on group membership. Given the ordinal nature of the dependent variables, the assumptions underlying ordinary least squares (OLS) regression are not met. Accordingly, we employed ordinal logistic regression models based on the proportional odds assumption to test our hypotheses (Long and Freese 2006). The models estimate the coefficients of the number of group memberships, interpersonal contact networks, the squared terms of both membership count and interpersonal networks, and socio-demographic controls. Regression coefficients are reported as logit estimates, representing the change in the log-odds of the dependent variable associated with a one-unit change in the independent variable. For ease of interpretation, we also present percentage changes in Section 4.

To test the first two hypotheses concerning the curvilinear association between social networks and mental health, we first estimate models examining the effects of interpersonal networks and group membership separately, and then include both variables in a saturated model. Levels of anxiety, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation are examined in Models 1–3, 4–6, and 7–9, respectively. Then, to test the third hypothesis on community context, we assess the non-linear effect of group membership on mental health separately for metropolitan cities (i.e., big cities), non-metropolitan cities (i.e., small and mid-sized cities), and towns and villages. The subsample sizes are 3543 for metropolitan cities, 2996 for non-metropolitan cities, and 1682 for towns and villages.

To assess potential multicollinearity between group membership and the quadratic terms, we examined variance inflation factors (VIFs), and VIF values for group membership and its squared term were below the conventional threshold of 5, suggesting that multicollinearity is unlikely to be a serious concern. As a robustness check, we additionally mean-centered the group membership variables and re-estimated all models, and the results remained substantively unchanged across all three dependent variables.

4. Results

What is the relationship between group membership and mental health distress? Table 2 presents evidence supporting our hypotheses regarding a curvilinear association between the two. Models 1–3, 4–6, and 7–9 report the results of ordered logistic regression analyses for levels of anxiety, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation, respectively.

Table 2.

Ordered logistic regression analysis on the levels of anxiety, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation.

Regarding the level of anxiety, Model 1 shows that, consistent with prior studies on interpersonal networks, a one-unit increase in interpersonal contact networks is associated with a 42.8% decrease (β = −0.559, p < 0.001) in anxiety, whereas a one-unit increase in the squared term corresponds to a 9.5% increase (β = 0.091, p < 0.001). Similarly, Model 2 reveals that a one-unit increase in the number of group memberships is associated with a 23.6% decrease (β = −0.269, p < 0.001) in anxiety, while the squared term predicts a 4.6% increase (β = 0.045, p < 0.01). In Model 3, which includes both contact networks and group membership variables, the curvilinear association between group membership and anxiety remains, though the magnitude decreases slightly to a 21.0% decrease (β = −0.236, p < 0.001) for the linear term and a 4.0% increase (β = 0.039, p < 0.05) for the squared term. Results in Models 1–3 indicate that the size of social networks exhibits a U-shaped relationship with mental health problems, even after controlling for one’s age and biological sex assigned at birth, education and income, physical health conditions, marital status, and generalized interpersonal trust.

For depressive symptoms (Models 4–6), the U-shaped relationship for group membership is also observed, though less pronounced than for anxiety. Specifically, the number of group memberships predicts a 17.1% decrease (β = −0.188, p < 0.001) in depression in Model 5 and a 14.9% decrease (β = −0.161, p < 0.01) in Model 6, while the squared term is associated with a 3.7% increase (β = 0.036, p < 0.05) and a 3.1% increase (β = 0.031, p = 0.053), respectively. Although the statistical significance of the squared term in Model 6 slightly exceeds the 0.05 level, the overall pattern continues to suggest a curvilinear relationship. These results again align with prior literature, showing that contact network size is negatively, and its squared term positively, associated with depression.

Turning to suicidal ideation (Models 7–9), group membership count is linked to a 37.2% decrease (β = −0.465, p < 0.05) in suicidal ideation before controlling for interpersonal networks and a 34.8% decrease (β = −0.427, p < 0.05) afterward. The squared term is associated with a 6.6% increase (β = 0.064, p < 0.05) and a 5.9% increase (β = 0.057, p < 0.05), respectively. In other words, both contact networks and group memberships display a U-shaped association. Taken together, results across all three dimensions of mental health—anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation—support our first two hypotheses: group membership count is negatively associated with mental health distress (H1), but an excessively large number of group memberships is positively associated with it (H2).

As to the control variables, the results presented in Table 2 indicate that respondents’ age is negatively associated with levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms, while no significant relationship is observed with suicidal ideation. Furthermore, educational attainment is significantly and positively associated with suicidal ideation, whereas household income is significantly related to higher levels of anxiety. Among the control variables, the most robust and consistent predictor of mental health distress is respondents’ physical health; subjective health status is significantly and negatively associated with anxiety, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation. Marital status also appears relevant, as married individuals are less likely to experience depressive symptoms and suicidal thoughts. Finally, generalized social trust is significantly and negatively associated with anxiety and depressive symptoms.

While our primary measure captures the social networks respondents form through active participation in social groups, we conducted a sensitivity analysis in Models 2 and 3 by including both passive membership and active involvement as the key independent variable. The results indicate that the statistical significance of the squared term of group membership disappears for both anxiety and depression. These findings suggest that mental distress arises only from active and excessive involvement in multiple social groups, rather than mere passive membership.

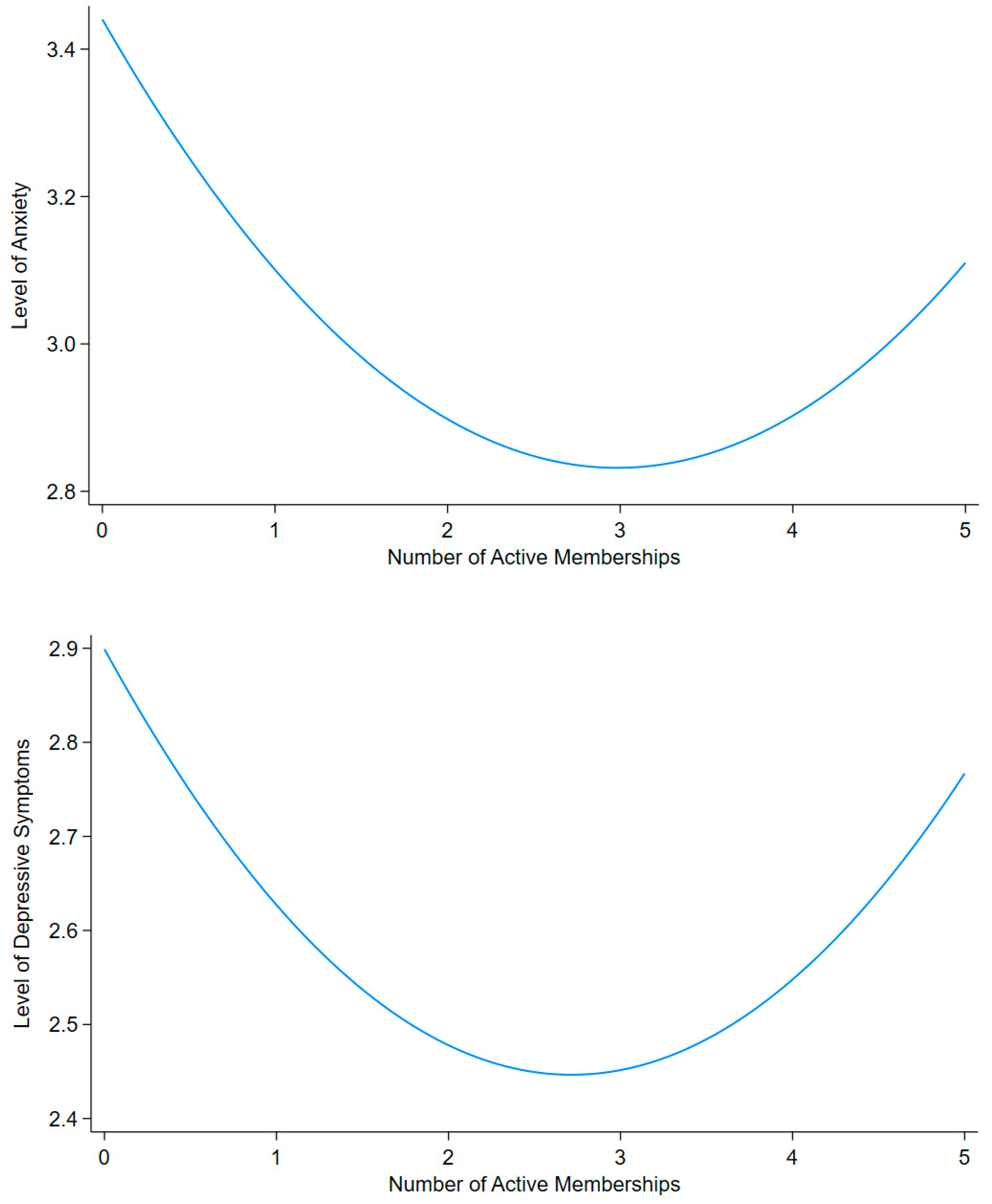

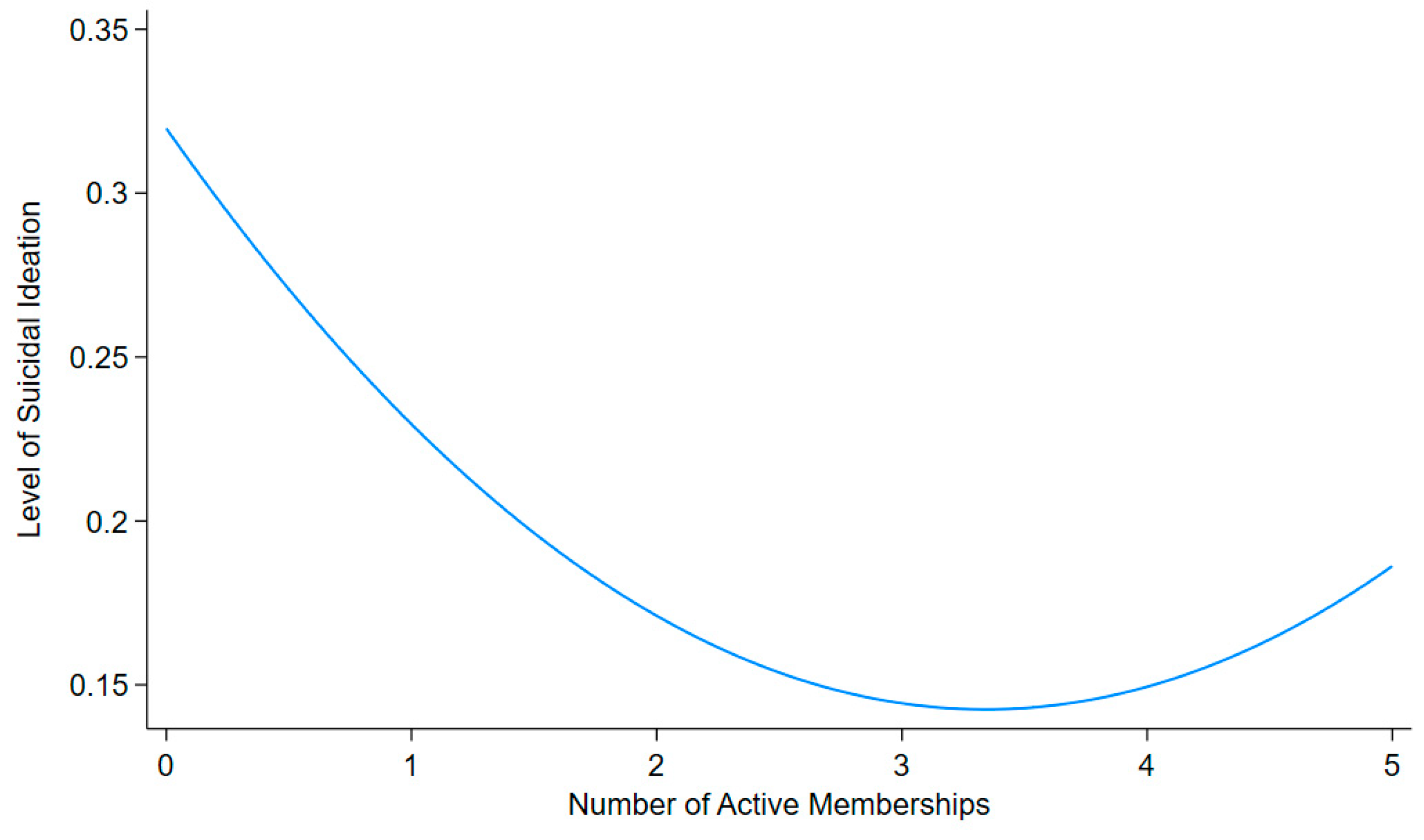

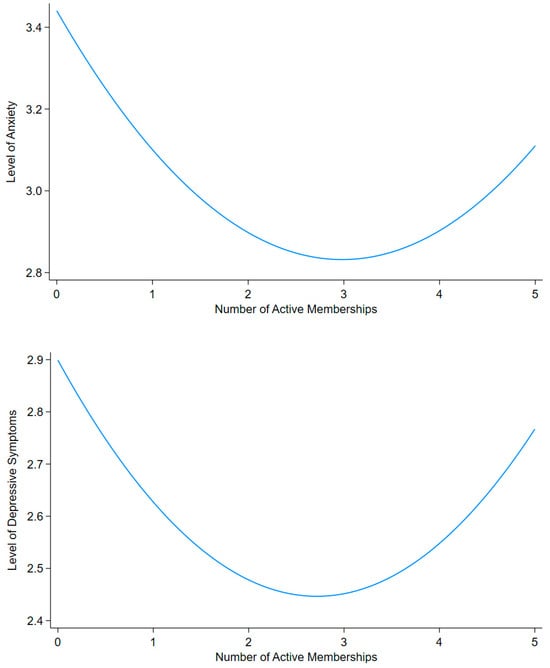

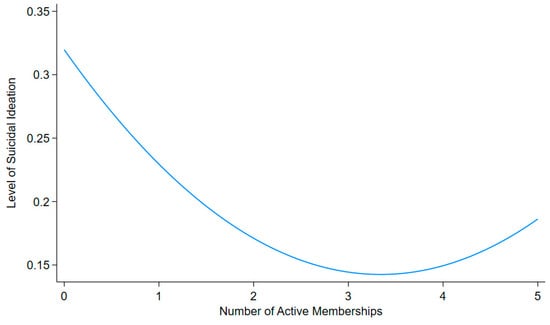

To visualize the curvilinear relationship between group membership and mental health distress, we compute predicted levels of anxiety, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation based on individuals’ number of group memberships, holding all other control variables at their mean values. Figure 2 presents these predicted values and clearly depicts the U-shaped association.

Figure 2.

Predicted Probabilities of the effect of the number of active memberships on anxiety, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation.

As shown in the figure, social relationships formed through group membership are negatively associated with mental health distress up to a threshold, beyond which the association becomes positive. More specifically, when the number of active group memberships exceeds three, the association gradually shifts from negative to positive. This curvilinear pattern is evident for both anxiety and depressive symptoms. For suicidal ideation, the U-shape remains, but the shift from negative to positive is less pronounced.

Next, we investigate how community type reshapes the U-shaped relationship between social group membership and mental health problems. Table 3 presents the results of our analyses by community type, dividing the sample into metropolitan cities, smaller non-metropolitan cities, and towns/villages.

Table 3.

Ordered logistic regression analysis on the levels of anxiety, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation by communities.

Regarding anxiety, the first three models reveal a marked difference between interpersonal contact networks and social group membership. While the U-shaped association between interpersonal networks and anxiety is consistently observed across all three community types, the curvilinear relationship between group membership and anxiety emerges only in metropolitan cities. Specifically, a one-unit increase in the number of group memberships is associated with a 34.2% decrease (β = −0.419, p < 0.001) in anxiety, whereas the squared term predicts a 7.4% increase (β = 0.071, p < 0.01). This pattern is not statistically significant in non-metropolitan cities or in towns and villages.

For depressive symptoms, Table 2 showed no clear curvilinear relationship for social group membership, and disaggregating the sample by community type in Table 3 confirms this absence. The U-shaped pattern does not appear in metropolitan cities, non-metropolitan cities, or towns and villages. In contrast, for suicidal ideation, the curvilinear association between group membership and suicidal thoughts is again evident in metropolitan cities. Here, group membership count is related to a 33.6% decrease (β = −0.409, p < 0.01) in suicidal ideation, while the squared term is associated with a 7.9% increase (β = 0.076, p < 0.05). It is also noteworthy that, at least for suicidal ideation, the U-shaped association for interpersonal contact networks appears only in metropolitan cities and is absent in smaller communities.

Overall, the results of the ordered logistic regression models support our third hypothesis, indicating that the U-shaped relationship between group membership and mental health distress is more pronounced in urban communities than in local communities. This curvilinear relationship between group membership and mental health problems among metropolitan residents is most evident in anxiety levels, but it is also notably present in the case of suicidal ideation.

Finally, regarding the control variables, the effect of age does not vary across urban and rural communities. Education level is negatively associated with mental health distress, particularly in towns and villages, whereas household income contributes to mental health problems in these rural communities. Moreover, the strong protective influence of physical health on mental health distress is consistent across different community types. Lastly, the effects of marital status and generalized social trust remain stable across varying community environments.

Whereas our main analysis emphasizes community size as a critical factor reshaping the relationship between group membership and mental health problems, we also adopt a gendered perspective as a sensitivity test. When dividing the sample by sex rather than community type, the U-shaped relationship emerges more clearly among females. Although the negative association between group membership and mental health distress is consistent for both sexes, the curvilinear association is statistically significant only for females, specifically in relation to anxiety and also to suicidal ideation to some extent. These results suggest that, in the South Korean context, women may bear a disproportionate psychological burden from excessive social affiliation compared to men.

5. Conclusions and Implication

By actively participating in social groups, individuals in contemporary society cultivate social relationships and foster a sense of belonging (McPherson et al. 2006; Sampson et al. 2002). This form of affiliation network, developed through group membership, is distinct from, though not mutually exclusive with, one-on-one relationships (Breiger 1974; Feld 1981). Focusing on group membership while controlling for interpersonal contact networks, this study examines their curvilinear effect on mental health. Findings from ordered logistic regression models indicate that, across anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation, the number of group memberships is negatively associated with mental health distress up to a certain threshold, beyond which the association becomes positive. This pattern holds even after controlling for physical health conditions, generalized interpersonal trust, and other socio-demographic attributes. Moreover, the U-shaped effect of group membership is more pronounced in metropolitan cities than in smaller cities or local communities, particularly with respect to anxiety and suicidal ideation. These results offer insights into how, and under which social conditions, social group membership shapes mental health outcomes.

First, we extend the existing literature by demonstrating that not only interpersonal networks but also social relationships formed through group membership exert an ambivalent and paradoxical influence on mental distress. While prior research has shown that excessive interpersonal relationships can heighten social stress and exacerbate mental health problems (Falci and McNeely 2009; Maier et al. 2015; Portes 1998; Qu 2024), our study highlights the detrimental effects of excessive group memberships. Although the emotional support and sense of belonging provided through group membership generally enhance mental well-being, our findings suggest that an overabundance of private group memberships can offset these benefits through feelings of overwhelming obligation, unmanageable demands, emotional exhaustion from status competition, and potential intragroup conflict.

Second, our study suggests that the paradoxical influence of group membership is primarily an urban phenomenon. This contrasts with interpersonal contact networks, for which no clear differences are observed between urban and rural communities. In densely populated urban settings, social groups tend to be larger and more complex than those in local communities (Simmel [1903] 2016; Wellman 1979). As a result, residents participating in private groups in metropolitan areas may face greater obligations and social stress stemming from intensified status competition and a higher likelihood of intragroup conflict. These findings underscore the importance of examining how different local contexts shape the ways in which social networks affect individual lives.

Notwithstanding its contributions to the study of social networks and mental health, this research has several limitations. To begin with, the data used in this study were collected through cross-sectional annual surveys, but endogeneity remains a concern in our analyses, particularly because individuals with poorer mental health may self-select out of group participation. Longitudinal data would enable a more rigorous examination of the causal relationship between the number of group memberships and mental health distress. Future research using longitudinal data should address potential selection and reverse causality by employing lagged independent and dependent variables as well as fixed-effects models.

Next, social surveys are appropriate for capturing subjective states such as perceived psychological and mental distress, but self-reported measures are susceptible to reporting biases and they are not validated through external, behavioral measures. Future research would benefit from combining survey data with objective and expert-based measures to further validate and extend the current research.

Also, detailed information on the specific private groups in which individuals participate within a given local community would enable a more precise assessment of the effects of affiliation networks. While this study employs nationally representative, ego-centric data to measure social relationships based on the number of private group memberships, two-mode data on social groups and their members could be transformed into dyadic data, allowing for the computation of individuals’ positions within the network (Borgatti and Everett 1997; Wasserman and Faust 1994). Using centrality measures, researchers could then examine the curvilinear association between individuals’ positions in affiliation networks and mental health outcomes with greater precision—although such findings may not be nationally representative. Incorporating additional psychological variables could also provide a more comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms linking group participation to mental health. Moreover, greater attention to gender and age differences may be warranted, as the patterns and dynamics of social group participation vary across these demographic categories.

In addition, future research should delve into how different local environments reshape the relationship between group membership and mental health. While this study demonstrates that the number of group memberships differentially influences mental health distress, qualitative approaches could complement these findings by exploring how group dynamics differ between larger, more complex groups in urban communities and smaller, more cohesive groups in rural settings. In-depth, in-person interviews could also shed light on how experiences of group participation vary between urban and rural residents.

Furthermore, one’s engagement in online communities is increasingly important in contemporary societies, but online social groups are qualitatively different from face-to-face local communities. Cutting across urban–rural distinctions, online platforms do not tend to involve lower levels of accountability pressure and weaker role expectations than offline organizations. While our proposed mechanisms linking excessive group membership to mental health, such as high obligations and social friction costs, may not be applicable to online membership, incorporating online communities represents an important and promising avenue for future research.

Finally, we tested our theoretical expectations regarding the effect of group membership using the case of South Korea, but future research could expand the literature by conducting empirical examinations in other countries. South Korea is distinctive for its rapid industrialization and successful democratization (Woo-Cumings 1999); nevertheless, we expect the curvilinear association between group membership and mental health problems to emerge in any context where private groups thrive within communities. In particular, in countries that exhibit pronounced urban–rural disparities in economic development and population density, we anticipate that the paradoxical influence of social group membership will be especially evident in urban contexts. Despite these limitations in terms of data and context, this study opens new avenues for future research on the dark side of group membership.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.H.; methodology, S.H.; software, S.H.; validation, S.H.; formal analysis, S.H.; investigation, C.S.S.; resources, C.S.S.; data curation, S.H.; writing—original draft preparation, S.H.; writing—review and editing, C.S.S.; visualization, S.H.; supervision, C.S.S.; project administration, C.S.S.; funding acquisition, C.S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Chung-Ang University Graduate Research Scholarship in 2024. Also, this work was supported by the IITP (Institute of Information & Communications Technology Planning & Evaluation)-ITRC (Information Technology Research Center) grant funded by the Korea government (Ministry of Science and ICT) (IITP-2025-RS-2024-00437633). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are publicly available from the Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs (KIHASA). The 2023 Korea Social Integration Survey (KSIS) can be accessed through the official data portal (https://www.kihasa.re.kr/en) after user registration and approval. No special privileges were required to obtain the data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Berkman, Lisa F., Thomas Glass, Ian Brissette, and Teresa E. Seeman. 2000. From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Social Science & Medicine 51: 843–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgatti, Stephen P., and Martin G. Everett. 1997. Network analysis of 2-mode data. Social Networks 19: 243–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1986. The Forms of Capital. In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education. Edited by John G. Richardson. New York: Greenwood, pp. 241–58. [Google Scholar]

- Brashears, Matthew E., Michael Genkin, and Chan S. Suh. 2017. In the organization’s shadow: How individual behavior is shaped by organizational leakage. American Journal of Sociology 123: 787–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiger, Ronald L. 1974. The duality of persons and groups. Social Forces 53: 181–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappell, Neena L., and Mark Badger. 1989. Social isolation and well-being. Journal of Gerontology 44: S169–S176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Sheldon, and Denise Janicki-Deverts. 2009. Can we improve our physical health by altering our social networks? Perspectives on Psychological Science 4: 375–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, James S. 1988. Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology 94: S95–S120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornwell, Erin York, and Linda J. Waite. 2009. Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and health among older adults. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 50: 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehle, Crystal, Debra Larsen, and John E. Landers. 2001. Social support in marriage. American Journal of Family Therapy 29: 307–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driskell, Robyn L., Larry Lyon, and Elizabeth Embry. 2008. Civic engagement and religious activities: Examining the influence of religious tradition and participation. Sociological Spectrum 28: 578–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertel, Karen A., M. Maria Glymour, and Lisa F. Berkman. 2009. Social networks and health: A life course perspective integrating observational and experimental evidence. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 26: 73–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falci, Christina, and Clea McNeely. 2009. Too many friends: Social integration, network cohesion and adolescent depressive symptoms. Social Forces 87: 2031–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feld, Scott L. 1981. The focused organization of social ties. American Journal of Sociology 86: 1015–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferlander, Sara. 2007. The importance of different forms of social capital for health. Acta Sociologica 50: 115–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, Claude S. 1975. Toward a subcultural theory of urbanism. American Journal of Sociology 80: 1319–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, Claude S. 1982. To Dwell Among Friends: Personal Networks in Town and City. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Granovetter, Mark S. 1973. The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology 78: 1360–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, Jong Hyun. 2014. Religious attendance, stress, and happiness in South Korea: Do gender and religious affiliation matter? Social Indicators Research 118: 1125–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawachi, Ichiro, and Lisa F. Berkman. 2001. Social ties and mental health. Journal of Urban Health 78: 458–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Hyung Min, and Sun Sheng Han. 2012. Seoul. Cities 29: 142–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korea Institute of Public Administration. 2023. Korea Social Integration Survey 2023 [Data Set]. Seoul: Korea Institute of Public Administration. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, Chaeyoon, and Carol Ann MacGregor. 2012. Religion and volunteering in context: Disentangling the contextual effects of religion on voluntary behavior. American Sociological Review 77: 747–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Chaeyoon, and Robert D. Putnam. 2010. Religion, social networks, and life satisfaction. American Sociological Review 75: 914–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Nan. 2001. Social Capital: A Theory of Social Structure and Action. Cambridge: Cambridge University. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Nan, Xiaolan Ye, and Walter M. Ensel. 1999. Social support and depressed mood: A structural analysis. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 40: 344–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, J. Scott, and Jeremy Freese. 2006. Regression Models for Categorical Dependent Variables Using Stata. College Station: Stata Press, vol. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Maier, Christian, Sven Laumer, Andreas Eckhardt, and Tim Weitzel. 2015. Giving too much social support: Social overload on social networking sites. European Journal of Information Systems 24: 447–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPherson, Miller. 1983. An ecology of affiliation. American Sociological Review 48: 519–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPherson, Miller, Lynn Smith-Lovin, and Matthew E. Brashears. 2006. Social isolation in America: Changes in core discussion networks over two decades. American Sociological Review 71: 353–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portes, Alejandro. 1998. Social Capital: Its Origins and Applications in Modern Sociology. Annual Review of Sociology 24: 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, Robert D. 1995. Tuning in, tuning out: The strange disappearance of social capital in America. PS: Political Science & Politics 28: 664–83. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, Robert D. 2000. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon and Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, Tianyao. 2024. A bridge too far? Social network structure as a determinant of depression in later life. Social Science & Medicine 345: 116684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, Robert J., Jeffrey D. Morenoff, and Thomas Gannon-Rowley. 2002. Assessing “neighborhood effects”: Social processes and new directions in research. Annual Review of Sociology 28: 443–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmel, Georg. 2016. The metropolis and mental life. In Social Theory Re-Wired. London: Routledge, pp. 469–77. First published 1903. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Kirsten P., and Nicholas A. Christakis. 2008. Social networks and health. Annual Review of Sociology 34: 405–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Lijun, Philip J. Pettis, Yvonne Chen, and Marva Goodson-Miller. 2021. Social cost and health: The downside of social relationships and social networks. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 62: 371–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, Chan S., Matthew E. Brashears, and Michael Genkin. 2016. Gangs, clubs, and alcohol: The effect of organizational membership on adolescent drinking behavior. Social Science Research 58: 279–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, Chan S., Paul Y. Chang, and Yisook Lim. 2012. Spill-Up and Spill-Over of Trust: An Extended Test of Cultural and Institutional Theories of Trust in South Korea. Sociological Forum 27: 504–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, Chan S., Yisook Lim, and Harris Hyun-soo Kim. 2023. Ready to rumble? Popularity, status ambiguity, and interpersonal violence among school-based children. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 38: 3612–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thoits, Peggy A. 2011. Mechanisms linking social ties and support to physical and mental health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 52: 145–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thoits, Peggy A., and Lyndi N. Hewitt. 2001. Volunteer work and well-being. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 42: 115–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umberson, Debra, and Jennifer Karas Montez. 2010. Social Relationships and Health: A Flashpoint for Health Policy. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 51: S54–S66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uslaner, Eric M. 2002. The Moral Foundations of Trust. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Verba, Sidney, Kay Lehman Schlozman, and Henry E. Brady. 1995. Voice and Equality: Civic Voluntarism in American Politics. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Villalonga-Olives, Ester, and Ichiro Kawachi. 2017. The dark side of social capital: A systematic review of the negative health effects of social capital. Social Science & Medicine 194: 105–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Hongmei, Mark Schlesinger, Hong Wang, and William C. Hsiao. 2009. The flip-side of social capital: The distinctive influences of trust and mistrust on health in rural China. Social Science & Medicine 68: 133–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasserman, Stanley, and Katherine Faust. 1994. Social Network Analysis: Methods and Applications. Cambridge: The Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge. [Google Scholar]

- Wellman, Barry. 1979. The community question: The intimate networks of East Yorkers. American Journal of Sociology 84: 1201–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickramaratne, Priya J., Tenzin Yangchen, Lauren Lepow, Braja G. Patra, Benjamin Glicksburg, Ardesheer Talati, Prakash Adekkanattu, Euijung Ryu, Joanna M. Biernacka, Alexander Charney, and et al. 2022. Social connectedness as a determinant of mental health: A scoping review. PLoS ONE 17: E0275004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo-Cumings, Meredith. 1999. The Developmental State. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.