Abstract

The emergent concept of the epigenetic inheritance of trauma across multiple generations has gained widespread attention in popular media, arguably at the cost of sufficient critical evaluation. This oversight risks distorting the complex and multifaceted nature of trauma transmission, with potential consequences for affected individuals and the broader society. Specifically, the prevalence of this oversimplified narrative in social work and healthcare settings underscores the need for a clearer and critical understanding of the science. To address this need, this work aims to support social workers and other healthcare workers that are interested in better understanding the biological basis of epigenetics as they integrate emerging research on trauma transmission into their daily practice. The paper first introduces fundamental concepts in epigenetics for a non-expert audience, clarifying key mechanisms that regulate gene activity. Building on this foundation, the authors examine sociocultural and biological models for trauma transmission, based on the current evidence, drawing on historic examples to highlight the strengths and limitations of each model. Ultimately, the authors encourage social workers to bridge both of these perspectives in trauma-informed care to enable social workers to challenge misconceptions about inherited trauma and foster patient empowerment through accurate education and advocacy, promoting more holistic and effective care.

1. Introduction

In recent decades, the concept that trauma can be transmitted across generations through epigenetic mechanisms has garnered considerable attention across social, scientific, and clinical spheres of influence (Mulligan et al. 2025; Yehuda and Lehrner 2018). For individuals, families, and communities with a history of inter- and/or trans-generational trauma, such compelling narratives offer relief by helping those impacted make sense of long-standing patterns of suffering that previously lacked a clear explanation (Yehuda and Lehrner 2018).

As a result, social workers increasingly encounter these concepts in practice, where engagement with vulnerable individuals and families necessitates sensitivity to trauma histories and an understanding of the plausible mechanisms of trauma transmittance. Such knowledge is essential not only to inform one’s practice and increase efficacy, but also to navigate the implications of such knowledge on the lives of vulnerable individuals (Combs-Orme 2013; Levenson 2017). At the same time, studies investigating the transmission of trauma across generations face inherent difficulties in distinguishing biological inheritance from social and cultural transmission (Yehuda and Lehrner 2018). In other words, study design is limited in its ability to determine whether a particular behaviour results from the environment in which one is raised (social transmission) or from epigenetic determinants (biological transmission). In all likelihood, it is almost always a combination of both factors.

Nevertheless, critically examining the current state of evidence for biological trauma transmission—in light of its preliminary nature—can guide social workers in avoiding the perpetuation of misinformation and tailoring interventions for clients with greater intentionality. This will not only support clients in developing a more accurate understanding of their circumstances, but will help social workers remain up-to-date on the emerging science that may shape the future of trauma-informed care. The molecular biology of epigenetics is very complex and there is an absence of articles aiming to explain the science to non-experts that want to learn. Against this background, herein the aims of this paper will be to provide the following:

- A concise summary of basic epigenetic mechanisms for non-experts in healthcare settings, with a focus on social work, specifically those that want a deeper understanding of the molecular biology.

- A stepwise and simplified explanation of the epigenetic inheritance of trauma.

- A clarification of misunderstandings in the literature regarding the difference between intergenerational and transgenerational epigenetic inheritance.

- A knowledge base to help explain to clients how genetics and epigenetics may influence their living reality as a result of experiences connected to trauma.

2. Genetics

The term genetics originates from the Latin word genesis, meaning “origin,” and was first coined in 1905 by William Bateson to describe a new scientific field focused on understanding heredity (Keynes and Cox 2008). In just over a century since, the modest field of genetics has grown into a transformative discipline, revolutionizing research (Passarge 2021). Although complex at first glance, the foundations of all genetics is captured in the ‘central dogma of molecular biology’ (Cobb 2017).

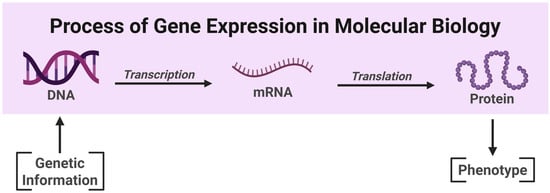

Simply put, the ‘central dogma of molecular biology’ denotes a long-standing foundational theory established during the field’s inception that describes the transmission of genetic information in a biological system rather than a prescriptive or negative form of dogma. Genetic information flows from double-stranded deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), to messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA), and finally to a functional mature protein (Cobb 2017) (Refer to Figure 1). Other types of RNA are also transcribed from DNA, but these do not get translated to protein. To help understand these transitions and structures, it is valuable to consider the following: (1) What is DNA? (2) What is a gene? and (3) How are genes expressed? Throughout this discussion, we will use the commonly applied analogy of a cookbook to make these concepts more digestible (Raz et al. 2019).

Figure 1.

Simplified illustration of the transmission of genetic information in a biological system, known as the central dogma of molecular biology. The RNA can be reverse transcribed and there are other types of RNA that can be produced (for simplicity, not shown here). Image created in Biorender (2025) https://BioRender.com/.

DNA is often described as the instruction manual within each cell, containing all the information essential for development, function, and the maintenance of life (Bell and Dutta 2002; Yuan and Li 2020). DNA can be thought of as a cell’s recipe book that outlines how to produce anything the cell needs to function correctly. Structurally, DNA is a polymer—a large molecule formed of repeating units. The repeating units are four types of nucleotides: adenine, thymine, cytosine, and guanine (often abbreviated, “A, T, C, G”) (Travers and Muskhelishvili 2015).

Importantly, the genetic information is not stored in the chemical structure of a nucleotide, but rather in the specific sequence of these nucleotides in the polymer (Travers and Muskhelishvili 2015). In this sense, the nucleotides (A, T, C, G) can be thought of as letters in a code, where certain combinations form words that outline instructions like words in a cookbook. These instructions are grouped into distinct genomic units called genes, which can be thought of as individual recipes (Pesole 2008). As each recipe produces a specific dish, each gene contains the instructions to yield a specific final gene product (i.e., proteins, Figure 1). These final gene products are responsible for carrying out essential functions which shape one’s traits (e.g., eye color) or also known in scientific terms as the phenotype (Nachtomy et al. 2007).

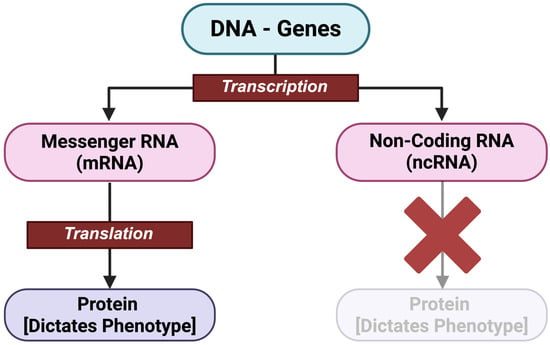

The process of gene expression involves two main steps: transcription, which outlines the flow of genetic information from DNA to RNA, and translation, the process to construct final gene products using the retrieved RNA instructions (Mercadante et al. 2025). During transcription, enzymes produce a copy of the genetic information in a gene in the form of an RNA molecule, also referred to as transcript. The RNA can be messenger RNA (mRNA) or non-coding RNA (ncRNA) (Refer to Figure 2). Non-coding RNAs, such as microRNAs or transferRNAs, do not get translated into protein but rather these ncRNAs are themselves the final product of the gene expression. The role of ncRNAs in gene expression will be discussed in detail in subsequent sections.

Figure 2.

Central Dogma of Biology, illustrating the differences in gene expression between mRNA and ncRNAs. The crossed out arrow shows that ncRNA is not translated. Image made Biorender (2025) https://BioRender.com/.

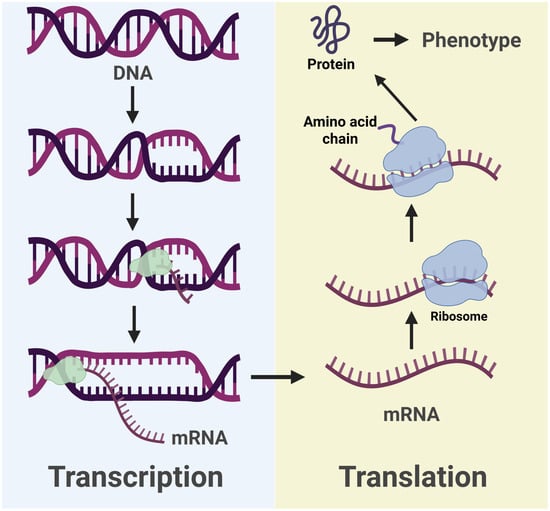

We focus here on messenger RNA (mRNA), as opposed to the other types of RNA which do not get translated. mRNA can be thought of as a recipe card—a temporary copy of the recipe from the cookbook or DNA—which will get translated into a protein. Proteins are one of the four main macromolecules and play an important role in body structure and function. Much like DNA, proteins are composed of repeating smaller units known as amino acids, which are a family of 20 distinct but related chemical structures. During the process of translation, these amino acids are joined side-by-side in distinct, unique, and sometimes repeating orders, to form the various protein enzymes and structural proteins in the body (LaPelusa and Kaushik 2025).

Returning to translation, nucleotides can be thought of as letters in a code, where specific groupings form words that provide instructions—like words on a recipe card. In the mRNA transcript, each triplet of nucleotides, called a codon, codes for a particular amino acid. During translation, a cellular structure known as a ribosome reads the mRNA transcript and acts as a scaffold to build the protein outlined by the codons. This process is aided by the transfer RNA (tRNA) molecules which each carry an amino acid that matches a particular codon. The ribosome matches these tRNAs to each codon in the mRNA transcript to produce a correctly ordered amino acid chain which gives way to a functional protein. The entire process thus encompasses the beginning and termination of gene expression (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Illustration of the key events of transcription and translation involved in gene expression. The arrows represent the flow of genetic information. Image made Biorender (2025) https://BioRender.com/.

Interestingly, although all cell types in the human body contain the same genetic information, they are not identical. This is because different genes are turned on and off, and the level at which each gene is expressed is not the same across cell types (Duncan et al. 2014). These distinct patterns of gene and consequential protein expression create unique molecular profiles that give rise to differences in observable characteristics, or phenotypes, that delineate one cell type from another in a multicellular organism (Barros and Offenbacher 2009).

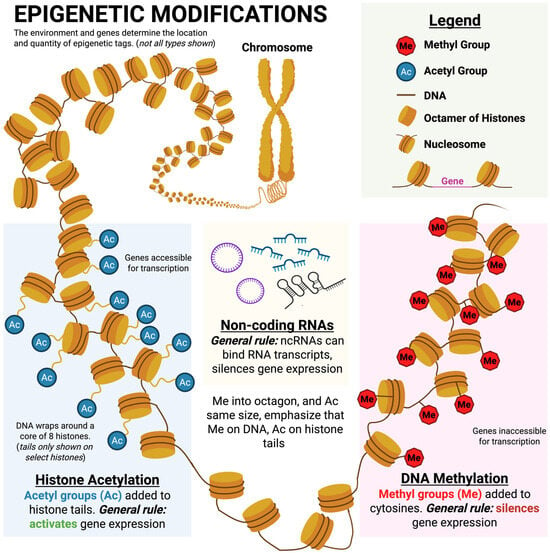

Gene expression is regulated by mechanisms that affect how easily cellular machinery can access DNA to begin transcription, the first step of gene expression (Peaston and Whitelaw 2006). These regulating mechanisms that do not alter the underlying DNA sequence itself, but rather only influence its accessibility, are known as epigenetic modifications (the term “epigenome” was originally coined by Conrad Waddington (Waddington 1942)). To date, a handful of different epigenetic modifications have been identified which include DNA methylation, numerous histone modifications (acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, sumoylation, and more), and non-coding RNAs that interfere with gene expression (Portela and Esteller 2010). These modifications typically occur in response to environmental stimuli which allow an organism to adjust the expression of specific traits without altering the genomic information (Portela and Esteller 2010).

The language used to describe these differences in genetic information are genome and epigenome. The genome classically refers to an organism’s complete set of genetic information, the DNA. The epigenome refers to the collection of modifications to chromatin (DNA + proteins) that alter gene expression without changing the DNA sequence itself (Baduel et al. 2024; Murrell et al. 2005). Both the genome, and in some cases, the epigenome can be passed on to offspring, concepts referred to as genetic and epigenetic inheritance, respectively (Fitz-James and Cavalli 2022).

A variety of environmental factors such as stress, diet, and life experiences alongside cellular and physiological stimuli can encourage epigenetic modifications that alter gene expression and, in turn, a person’s observable traits or phenotype (Roth 2013). As our bodies and brains are entirely composed of cells, changes in gene expression can affect our health, cognition, and behavior. Along these lines, trauma has been proposed to elicit changes in the epigenome that may predispose individuals to maladaptive thoughts and behaviors (Yehuda and Lehrner 2018). Moreover, as these changes act through the epigenome, ongoing discussion persists on whether epigenetic changes can be passed to offspring. Such ideas mirror previously disproved theories of evolution that suggested that organisms could pass down physical traits they acquired in their lifetime to their progeny (Deichmann 2016). To better understand this possibility, it is important to examine how epigenetic modifications occur, whether they are permanent, and to what extent they can be inherited.

3. Epigenetics

As mentioned above, the three main modes of epigenetic modification are DNA methylation, gene silencing via non-coding RNAs, and histone modifications (Figure 4). For each of these mechanisms, we will describe (1) how the modification occurs and (2) how it affects gene expression. While many of these processes involve complex enzymes, for the sake of this discussion, we can think of these enzymes as helpers that facilitate the modification.

Figure 4.

Summary of the three main modes of epigenetic modification. Histone acetylation typically increases gene expression in the affected area, while DNA methylation and non-coding RNAs typically reduce expression of affected genes. Modified from Orton et al. (Orton et al. 2023). Image made Biorender (2025) https://BioRender.com/.

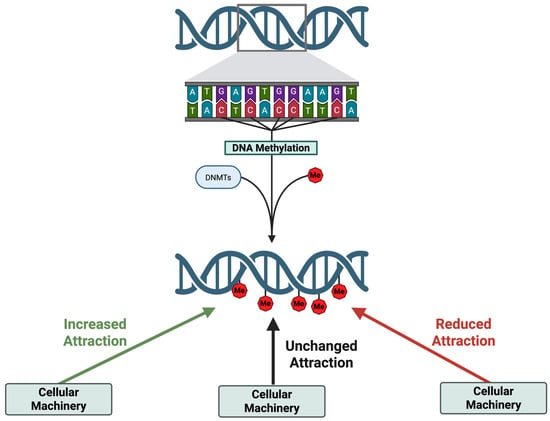

Starting with DNA methylation, one of the best characterized and most prominent epigenetic modifications (Moore et al. 2013). Historically, DNA methylation was first characterized as an epigenetic mechanism in 1975 (Holliday and Pugh 1975; Riggs 1975), involving the addition of a methyl group (CH3) to specific cytosine nucleotides in the DNA (Figure 5). This process is completed by enzymes (Gold et al. 1963a, 1963b; Jin and Robertson 2013). Using the cookbook analogy, DNA methylation can be thought of as placing a sticky note over certain parts of a recipe in a cookbook, making those instructions harder, or even impossible, for the chef to read.

Figure 5.

The impact of methylation on the affinity of cellular machinery and thereby gene expression. Cellular machinery involved in gene expression interacts with target genes based on its affinity (attraction) to that particular region of DNA. This interaction, or affinity, is dependent on the shape of the interacting pieces. Changes in the shape of a chromatin region occur when DNA is de-methylated or methylated, which thus changes the attraction of cellular machinery to that region, leading to decreases or increases in gene expression. Image made Biorender (2025) https://BioRender.com/.

Importantly, not all cytosines are methylated, and the effect of methylating depends on where in the DNA the modification occurs (Dhar et al. 2021; Moore et al. 2013). This is because different cellular machinery interacts with different regions of the DNA—and these interactions are influenced by the presence or absence of methyl groups (Dhar et al. 2021). Along these lines, methylation can attract, repel, or have no effect on gene expression with varying severity (Figure 5).

To extend the cookbook analogy, consider that instead of one chef, there are multiple chefs, each responsible for different parts of the meal preparation—gathering ingredients, preheating the oven, cooking, plating, etc. These chefs represent different cellular machinery involved in gene expression. Each chef also has a different level of vision. Some can see past the sticky notes and continue as usual; others with poor vision are unable to read the recipe at all if a sticky note is present; and some chefs with exceptional vision may even be intrigued by the sticky note and pay extra attention to the recipe, enhancing their engagement. As such, depending on the cellular machinery, or the chef, the methylation or sticky note will have a different effect.

To help illustrate the analogy you can consider the promoter region of a gene. A promoter region is near the beginning of a gene and serves as a site of attachment for the cellular machinery required to begin gene expression (Dhar et al. 2021). In our analogy, this region is like the introduction instructions of a recipe that tells the head chef which sous-chefs are needed to complete a dish. When methylation occurs in the promoter region of a gene, it often prevents gene expression. Returning to the analogy, since the head chef has poor vision and cannot see through the sticky note placed on the recipes introduction, they will fail to recruit the necessary sous-chefs to complete the meal. As a result, the meal (or gene product) in this case is never made.

Similarly, histone modifications influence gene expression by regulating the accessibility of the genome. For context, the entire DNA in a single human cell consists of approximately six billion nucleotides and when stretched out, measures roughly 2 m in length (Piovesan et al. 2019). This is remarkable given that the majority of animal cells are 0.000010–0.000020 m long (Li et al. 2015). This extraordinary packaging is made possible by histones proteins (Simpson et al. 2025). Histones assemble in groups of eight to form positively charged complexes, around which short segments of negative charged DNA are wrapped. Together, this combined structure of eight histones and DNA is referred to as a nucleosome. These nucleosomes then can undergo further coiling of the DNA to form chromatin, which when fully compacted is referred to as chromosomes (Simpson et al. 2025).

The classic analogy used to illustrate DNA packaging is the “beads on a string” analogy. In this model, DNA is represented by the string and a group of eight histones is a bead. A nucleosome is formed when the string is wrapped around a bead. A loosely coiled string of beads is then considered chromatin, while tightly coiled would be considered chromosomes (Baldi et al. 2020).

Histones, being proteins, can undergo post-translational modifications that influence how tightly or loosely DNA is wrapped around them, altering the accessibility of the DNA (Allfrey et al. 1964; Zhang et al. 2021). Several types of these modifications have been described in the literature, such as methylation, acetylation, and many more (Liu et al. 2023). Of these, the majority of histone modifications are methylation or acetylation which tend to decrease and increase gene expression, respectively (Eberharter and Becker 2002; Shirvaliloo 2022). These modifications can occur anywhere along the amino acid chains of histone proteins (Mersfelder and Parthun 2006). It is important to distinguish that, in this context, methylation refers to the attachment of a methyl group to the histone protein, not to the DNA itself as was the case for DNA methylation.

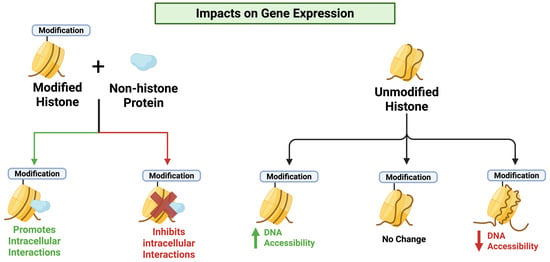

Generally, histone modifications can affect gene expression in the following two ways: (1) by altering the binding of non-histone proteins to DNA, or (2) by structurally altering the nucleosome to expose or hide different regions of DNA (Figure 6) (Lawrence et al. 2016; Liu et al. 2023). Certain modifications attract or repel non-histone proteins, thereby influencing their ability to interact with the underlying DNA in gene expression (Liu et al. 2023). Others alter the nucleosome structure, making previously hidden genes accessible or conversely, concealing formerly exposed genes (Lawrence et al. 2016). In short, different modifications can either promote or inhibit gene expression depending on their nature and context. Importantly, as a single histone can undergo multiple modifications, the overall effect on gene expression reflects the combined influence of all the modifications (Zhang et al. 2021).

Figure 6.

The impact of histone modifications on gene expression. Histone modifications, such as acetylation and methylation, cause changes to the shape of the chromatin (DNA + histone proteins) which changes the way these regions of DNA interact with cellular machinery or vary the DNA accessibility. Image made Biorender (2025) https://BioRender.com/.

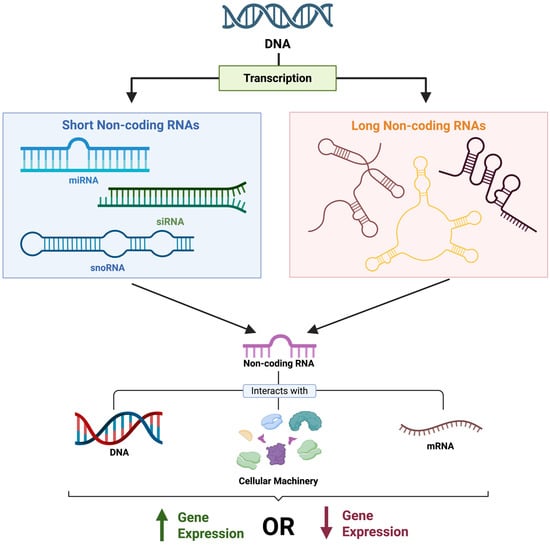

Following suite, non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) influence gene expression in comparable ways to histones and DNA methylation, but through varied modes of action (Figure 7). Although initially overlooked, non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) are now acknowledged as important epigenetic regulators of gene expression (Wei et al. 2017). Unlike protein-coding RNAs, ncRNAs are RNA transcripts that are not translated into protein. Instead, following transcription they act to regulate gene expression through diverse mechanisms (Lam et al. 2015). New types of ncRNAs continue to be discovered with examples including small nuclear RNAs, circular RNAs, and many more (Kumar et al. 2020). Given this diversity, ncRNAs are classically categorized by size into two main groupings: (A) short chain non-coding RNAs which includes siRNAs, miRNAs, and piRNAs, or (B) long non-coding RNAs (Wei et al. 2017). Broadly, ncRNAs impact gene expression by (i) directly interacting with DNA, (ii) binding to cellular machinery (e.g., transcription factors) to prevent or promote gene expression, and (iii) interacting with mRNA transcripts prior to translation (Kumar et al. 2020). Since discussing all ncRNAs is beyond the scope of this discussion, we will focus on microRNAs and long non-coding RNAs, which are among the most characterized and accessible. Moreover, it is noteworthy that there remains debate amongst epigeneticists as to the place of ncRNAs in epigenetic transmission,; however, this is beyond the scope of this work.

Figure 7.

The impact of non-coding RNAs on gene expression. Non-coding RNAs vary structurally and functionally while interacting with different genomic structures and machinery to either promote or inhibit gene expression. Image made Biorender (2025) https://BioRender.com/.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are short ncRNAs, composed of approximately 22 nucleotides, typically involved with gene repression (Kumar et al. 2020). While miRNA formation and function are complex, we will focus on the most relevant aspects. In most cases, a mature miRNA will regulate gene expression by directly binding with its target mRNA- the target being the transcript it was designed to regulate (Ipsaro and Joshua-Tor 2015). This binding can be either perfect or imperfect, and ultimately leads to suppression of gene expression in one of two ways: (1) by destroying the mRNA, or (2) by preventing its translation (Ipsaro and Joshua-Tor 2015). Under certain conditions, miRNAs can also regulate gene expression through interacting with gene promoters, the coding sequence, and other agents (O’Brien et al. 2018).

In comparison, long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), which are approximately 200 nucleotides in length, also play a significant role in gene silencing through mechanisms similar to their shorter counterparts (i.e., miRNAs) (Mattick et al. 2023). However, lncRNAs have been described to have a broader role in regulating gene expression (Statello et al. 2021). For instance, lncRNAs are involved in reorganizing chromatin structure, displacing proteins involved in transcription, or conversely recruiting particular proteins for gene expression (Statello et al. 2021). Through these diverse mechanisms, lncRNAs regulate gene activity, both activating and deactivating, in direct and indirect means.

Albeit different, all epigenetic mechanisms share a common feature of modifying gene expression without altering the DNA sequence itself. One cause of these modifications are environmental factors such as diet, pollutant exposure, stress, and many more (Klibaner-Schiff et al. 2024). As discussed earlier, there is growing interest as to whether these environment induced epigenetic changes can be inherited, passing on unbeknownst to future generations. This idea carries with it significant implications and warrants an understanding of epigenetics and the plausibility of epigenetic inheritance. With this in mind, we will now return to the topic of trauma to consider how its effects might be transmitted to future generations and to address common misconceptions.

4. Trauma and Epigenetics

Currently, there is a wide range of definitions and classifications for trauma based on the nature of the event, experiences, and/or effects on the affected individual (Contractor et al. 2020; Isobel et al. 2019a). For the purposes of this discussion, we will use the term trauma to specifically refer to psychological or mental health trauma. In general, psychological trauma is understood as a harmful event, series of events, or set of circumstances that causes significant physical and/or emotional distress, subjective to the individual, that results in impaired functioning (Feriante and Sharma 2025). Central to this definition is the emphasis on subjectivity, as trauma can be experienced directly or witnessed second-hand, as long as the patient considers the experience distressing (Leung et al. 2023).

From a diagnostic standpoint, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental health disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5), defines diagnosable trauma as involving “actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence” (First 2022, pp. 271–72). As such, this definition restricts the range of stressful events that can qualify as medically recognized trauma, a limitation met with both praise and criticism from experts (Pai et al. 2017). Within this framework, accurately diagnosing trauma relies on the completion of a thorough history and physical examination to identify any traumatic exposures that may have led to behavioral, emotional, or cognitive changes (Feriante and Sharma 2025). Importantly, this process requires a careful and sensitive approach to avoid triggering a traumatic response when gathering details of a patient’s lived experiences. Beyond exposure history, recognizing the symptoms commonly observed in trauma is essential for an accurate diagnosis.

Consistent with its broad definition, the ubiquitous nature of trauma is welldocumented. An epidemiological study conducted across 24 countries on six continents reported approximately 70% of individuals to have experienced at least one traumatic event, and 30% experience four or more traumatic events in their lifespan (Benjet et al. 2016). Similarly, a previous study found that 76% of survey respondents reported having been exposed to at least one traumatic event sufficient to cause PTSD (Van Ameringen et al. 2008). Taken together, these statistics support expert consensus that psychological trauma poses a significant global public health concern that warrants careful management and prevention at the individual, communal, and societal level (Magruder et al. 2017). In response to this concern, researchers have investigated the causes, underlying pathophysiology, and mechanisms of trauma transmission, the latter of which is the focus in this paper.

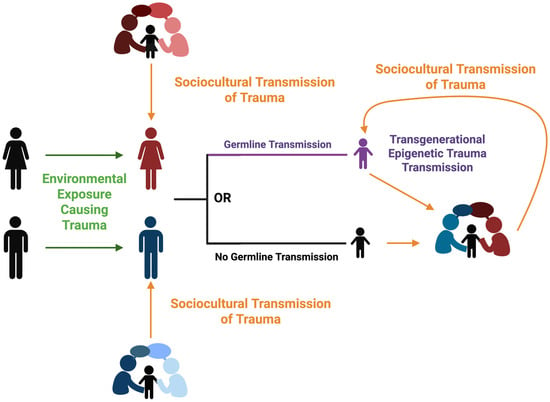

Two dominant mechanisms that have been proposed to explain the transmission of trauma across generations are (1) social/environmental transmission (e.g., parenting styles, attachment, poverty, discrimination, and lack of resources for social determinants of health, etc.) and (2) biological (e.g., epigenetic inheritance) (Figure 8) (Isobel et al. 2019b; Kirkbride et al. 2024; Yehuda and Lehrner 2018).

Figure 8.

Proposed model to explain the role of environmental exposure and sociocultural influence in the mounting and transmission of trauma between generations. Transgenerational epigenetic trauma transmission is depicted to occur from epigenetic mechanisms and/or sociocultural transmission. Image made Biorender (2025) https://BioRender.com/.

Historically, social or behavioral transmission, originating from Freudian psychology, refers to the spread of vulnerability and maladaptive behaviors between generations through learned experiences (Isobel et al. 2019b). In particular, this concept is commonly used to explain relational trauma, which outlines traumatic experiences that take place in the context of relationships, most notably researched in parent-infant attachment interactions (Amos et al. 2011). Notably, seminal research in the field found that adults with histories of relational trauma were at an increased risk of transmitting trauma to their children through maladaptive attachment styles (Fraiberg et al. 1975). Mechanistically, it is thought that a parent’s unresolved relational trauma can compromise their ability to sensitively react to their infant’s needs, increasing the likelihood of the infant developing insecure attachment (Kostova and Matanova 2024). Over time, unconscious displaced emotions shaped by past trauma can lead to maladaptive social patterns that are passed down through social learning to future generations (Isobel et al. 2019a; Barreto-Zarza and Arranz-Freijo 2022).

An important component of social trauma transmission is the environment or external agents that can (i) increase an individual’s vulnerability to trauma and/or (ii) hinder their ability to positively cope with their experiences (Scorza et al. 2019). As these conditions often persist, such environmental influences can be conserved between generations, giving way to both the development and transmission of trauma over time. Social conditions such as poverty, discrimination, exposure to violence, limited access to essential services, and a lack of social support can heighten the risk of trauma and limit its resolution (Scorza et al. 2019). For example, a child growing up in a high-crime area is more likely to experience actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence, the principal criteria for clinical trauma. Concurrently, limited access to therapy, social services, or community support can prevent positive coping and the resolution of trauma, increasing the likelihood that the unresolved trauma will impact future generations. In this way, environmental factors are intricately intertwined with the social transmission of trauma, as external agents guide the exposure to and the ability to recover from trauma.

In recent decades, explanations of trauma transmission have increasingly incorporated biological perspectives including altercations in brain-hormone stress axis, epigenetic mechanisms, or changes in brain structure (Ramo-Fernández et al. 2015). Together, these biological frameworks offer valuable insight that can inform interventions to reduce the impact of trauma transmission across generations. Within the broader biological context, epigenetic inheritance of trauma proposes that trauma-induced epigenetic modifications can be passed down from parent to offspring in the epigenome (Otterdijk and Michels 2016; Yehuda and Lehrner 2018).

As interest in epigenetic explanations has grown, the terms intergenerational and transgenerational have been adopted to describe epigenetic inheritance. However, the usage of these terms has been inconsistent across the field of psychology and molecular biology. Specifically, some researchers have used the terms interchangeably (Kostova and Matanova 2024), while others have distinguished the two on a basis of whether the epigenetic modification was acquired directly through environmental exposure or indirectly through the germ line (Horsthemke 2018; Pang et al. 2017; Perez and Lehner 2019). As a result, this inconsistent terminology has complicated scholarly discourse and contributed to misinformation.

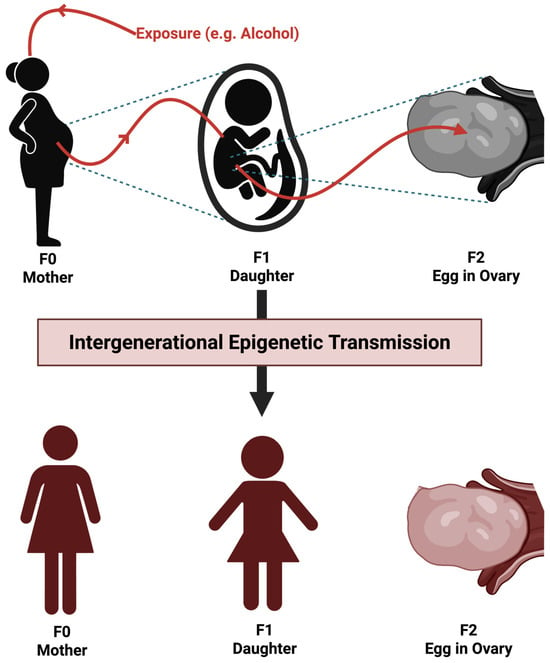

To reduce this confusion, this work clarifies the difference between both terms (Figure 8 and Figure 9). In brief, intergenerational epigenetics refers to epigenetic modifications that occur in both the parent and offspring following direct exposure to an environmental factor (Pang et al. 2017). A common example is prenatal alcohol exposure, in which both the fetus and the fetus’ developing ovaries are directly exposed to ethanol. Consequently, the epigenetic modifications observed in both the child and their eventual offspring would be considered intergenerational epigenetic inheritance.

Figure 9.

Proposed mechanism of intergenerational epigenetic trauma transmission. The image illustrates how a single environmental exposure can cause epigenetic changes across multiple generations, without actual epigenetic inheritance—in other words, the epigenetic changes are directly acquired as opposed to inherited from F0. Image made Biorender (2025) https://BioRender.com/.

In contrast, transgenerational epigenetic inheritance refers to transmission of epigenetic modifications that could not have resulted from direct environmental exposure (Perez and Lehner 2019). Instead, these epigenetic modifications must be passed down through the germline, inherited directly from the parent’s epigenome in light of the absence of a continued environmental exposure (Horsthemke 2018). Accordingly, to be considered true transgenerational epigenetic inheritance, both the altered phenotypes and epigenetic modifications must be observed in a generation that is one or more generations removed from the originally exposed individual (Perez and Lehner 2019).

Currently, there is substantial evidence supporting trauma-mediated intergenerational epigenetic inheritance, but evidence for transgenerational inheritance of trauma remains limited (Heard and Martienssen 2014; Horsthemke 2018; Yehuda et al. 2018). This limitation largely reflects the challenge of demonstrating that an epigenetic marker was truly inherited, rather than being acquired from repeated environmental exposure. This is further complicated by the impact of social and cultural transmission, which are difficult to control in human studies.

Reflecting on the literature, a large body of research is dedicated towards characterizing generational trauma through the lens of major collective historical traumas. While this paper does not aim to provide a comprehensive review of that literature, we will present prominent examples to demonstrate the tangible impact of trauma transmission and methodological challenges involved in this work.

One area of extensive investigation has been the transmission of trauma among Holocaust survivors and their descendants. While the majority of the early research in this field has focused on social mechanisms of trauma transmission, more recent work has begun to explore the plausibility of biological transmission. Focusing on social transmission, a 2019 systematic review reported a higher incidence of mental health problems in children with both parents as holocaust survivors compared to those with only one survivor as a parent (Dashorst et al. 2019). This aligns with broader findings suggesting that historical trauma can impact families for up to three generations, manifesting as emotional and psychological disorders, and altered perceptions of self and traumatic stress (Giladi and Bell 2013; O’Neill et al. 2018).

Importantly, conflicting findings in the literature exist. Some studies have reported no clear association between the psychological and physical distress experienced by Holocaust survivors and that of their children (Letzter-Pouw and Werner 2013). These contradictory findings have been criticized for potential sampling bias. Specifically, systematic reviews indicate that the impact of parental PTSD on offspring outcomes may vary depending on whether the trauma is transmitted through the father, mother, or both (Dashorst et al. 2019). As such, sampling bias in certain studies has been proposed to contribute to non-significant findings. Overall, the current evidence suggests that trauma may be embedded into collective memory and perpetuated via sociocultural mechanisms (Isobel et al. 2019b).

On the other hand, an increasing number of studies have begun to investigate the biological mechanisms of trauma transmission particularly in the context of Holocaust survivors. One area of focus is the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, the central biological system regulating the stress response, which has been found to function differently in Holocaust survivors (Bierer et al. 2020). The HPA axis involves a cascade of hormonal and neuronal responses that activate a stress response (Herman et al. 2016). A key hormone in this process is cortisol, a glucocorticoid, which is elevated during stress responses (Herman et al. 2016).

In the general population, increased DNA methylation of the FKBP5 gene, which encodes a cortisol related protein, has been shown to be associated with elevated cortisol and thereby stress (Naumova et al. 2016). Building on this, Yehuda et al. found that Holocaust survivors exhibited increased levels of DNA methylation for FKBP5 compared to control subjects (Bierer et al. 2020; Yehuda et al. 2016). However, their offspring showed decreased methylation of the same gene relative to the control group.

This pattern of inheritance challenges the current understanding of the epigenetic inheritance of trauma. If the effect of trauma were directly transmitted through the epigenome we would expect elevated methylation in both the survivors and their offspring. Conversely, if no epigenetic transmission took place, the offspring’s methylation pattern should have matched the control. Neither outcome was observed, indicating a more complex interaction may be responsible for the observed trend. While the role of epigenetics cannot be ruled out, findings such as these underscore the need for further investigations to clarify the role of epigenetics in trauma transmission.

It is evident that the mechanisms underlying trauma transmission are complex and multifaceted, with multiple areas requiring further characterization from both a sociocultural and epigenetic perspective. This complexity highlights the need to incorporate sociocultural, environmental, and biological perspectives into trauma-informed care. Such an approach will enable social workers to better understand the needs of their clients, empower clients to make accurate assessments of their own experiences, and encourage the development of holistic and effective interventions. As no single explanation is sufficient to account for trauma transmission alone, embracing humility by incorporating multiple perspectives and recognizing the limitations of each will encourage effective social work.

5. Implications for Social Work

Intergenerational and transgenerational trauma are profound issues within the social work profession and its intersection with clients. In Canada, this is particularly seen with indigenous communities following colonization, the Indian Residential Schools, the over-representation of Indigenous children in child welfare’s care, over representation of Indigenous peoples in carceral systems; all of which was well documented in the 2015 report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada 2015). These issues are also seen in other population groups, such as refugees and racialized populations who have been subject to multi-generational systemic biases, as described by American author Dorothy Roberts (Roberts 2023). At the time of this writing, there are multiple other conflicts around the world (e.g., Sudan, Gaza, Ukraine) where inter- and trans-generational impacts are likely to arise (Stares 2025). The topic of the epigenetic inheritance of trauma is vital so that client stories across generations can make sense in a current context. For example, there are those who may feel that the past traumas within the family and communal systems are biologically determinative of negative expectations for themselves. In this paper, we have explained why this need not be the case, given that it is not evidence-based.

To summarize, sociocultural mechanisms suggest that trauma can be transmitted through learned experiences or maladaptive behaviors formed in response to trauma. In contrast, biological mechanisms propose anatomical or physiological origins that can be directly inherited by offspring. Ultimately, however, examining the evidence for each model demonstrated that no single model is sufficient to capture the entire complexity of trauma transmission to date. Such insights underscore the need for applying an integrated holistic approach to trauma-informed care that draws and creates from both sociocultural and biological perspectives.

Taking a step back, it is essential to recognize the widespread nature of trauma exposure globally, its harmful effects, and the pressing need for modes of intervention (Olff et al. 2025). Psychotherapy experts have shown that any exposure to traumatic stress during childhood increases the risk of adverse health outcomes across multiple domains (Assari 2020). These include post-traumatic stress disorder, complicated grief, anxiety disorders, substance use disorders, sleep disturbances, neurobiological changes, and many more (Olff et al. 2025). To complicate matters further, the impact of traumatic exposure appears to be dose-dependent, with instances of greater exposure associated with worsened outcomes. These outcomes are often multiple and comorbid, underscoring the importance of comprehensive trauma screening (Haering et al. 2024).

Experts increasingly view trauma as a public health challenge, given its complex and unequal associations with socioeconomic status and the justice system (Magruder et al. 2017). Despite ongoing efforts to address disparities, trauma continues to disproportionately affect marginalized and low-income populations, reinforcing patterns of socioeconomic inequality (Abedzadeh-Kalahroudi et al. 2018). Researchers have identified persistent socioeconomic disparities in trauma incidence, trauma-related mortality, trauma care, and other related outcomes, with individuals with low SES consistently placed at a disadvantage (Abedzadeh-Kalahroudi et al. 2018).

Similar structural inequalities are also evident in the justice system, where justice-involved individuals experience higher rates of traumatic exposures across both childhood and adulthood (Jäggi et al. 2016). Although the complex relationship between trauma and the legal system is increasingly acknowledged, punitive approaches continue to dominate over rehabilitative techniques (Mazher and Arai 2025). This emphasis on correctional punishment may perpetuate harm and hinder meaningful reform for incarcerated individuals (Borschmann et al. 2024). To elaborate, the power dynamics inherent in the justice system can mirror past experiences of powerlessness, thus increasing the risk of re-traumatization (Cogan et al. 2025). Furthermore, the hostile nature of the prison environment characterized by frequent exposures to aggression, violence, restraints, bullying, and other malicious factors can expose or re-expose individuals to trauma, compounding on prior traumas. This again underscores the inherent complexity of trauma and the challenges of parsing out the role of epigenetic mechanisms of trauma transmission (both intergenerational and transgenerational) within the context of persistent social and structural inequalities.

The urgent need for new strategies to address trauma as a public health crisis has led to the development of trauma-informed care. This approach seeks to transform organisational practices by replacing interventions that exacerbate the detrimental effects of previous traumas with those that foster resilience and recovery (Bunting et al. 2019). To support this goal, advocates have developed care models that promote holistic and responsive treatment for individuals affected by trauma. These models equip social workers and healthcare professionals to assist individuals in healing from traumatic experiences while minimizing the risk of re-traumatisation (Bunting et al. 2019). Along these lines, trauma-informed care offers a vital opportunity to center client needs and enables social workers to make meaningful and lasting impacts on clients and their families.

To support social workers in this end, this work offered a clear and concise explanation of trauma transmission, with a particular focus on epigenetics. This was motivated by the widespread misinformation in popular media around the epigenetic inheritance of trauma, which required clarification (Orton et al. 2023). In addressing this, we aimed to empower social workers with a more integrated understanding of trauma, enabling holistic approaches in procedures, practice, policies, etc.

A key leader in advancing trauma-informed care is the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), which has operationally defined trauma-informed care based on four core principles: (A) understand the impact of trauma on the individuals and communities served, (B) recognizing the characteristic symptoms of trauma, (C) adapting practices to be trauma-informed, and (D) preventing the re-traumatization of patients receiving care (Grossman et al. 2021). In light of these foundational principles, a holistic understanding of trauma transmission inclusive of both biological and sociocultural perspectives can help social workers more effectively meet these criteria.

As a reminder, this paper reviewed both the epigenetic and sociocultural perspectives on the inheritance of trauma and highlighted the inadequacy of each model when considered in isolation. In suite, a more comprehensive understanding was proposed to emerge from integrating both perspectives, which arguably is better suited at the achievement of a trauma-informed approach. Consider the following benefits on understanding trauma, adapting practices, and preventing re-traumatization from said perspective.

To begin, considering both sociocultural and epigenetics perspectives offers a more accurate and nuanced understanding of how the environment influences trauma transmission. This integrated view acknowledges the role of both social learning and the still-emerging role of biological changes in transmitting trauma between generations. This provides a balanced framework that empowers clients to consider possible biological influences while recognizing the contribution of sociocultural influences that are context-dependent and not determinative of future outcomes. Such an understanding can help social workers consider both biological and cultural factors contributing to trauma in an individual and their associated community, allowing for a more comprehensive coverage of possible impacting factors. Furthermore, communicating this perspective to clients can aid in the processing of their trauma, overcoming feelings of fatalism, and promoting agency in their healing.

Moreover, adopting an integrated framework in social work can enhance the quality of trauma-informed care which is consistent with long standing models in social work such as Bronfenbrenner’s Person in Environment model (Bronfenbrenner and Morris 1998). To clarify, trauma-informed care involves tailoring the supports and resources provided to each client to minimize the risk of re-traumatization. Achieving this goal depends on two key elements: (1) identifying and understanding the types of trauma impacting clients (i.e., individual, interpersonal, communal) and (2) identifying and understanding any historical or collective traumas that have shaped the client’s health (Grossman et al. 2021). Insights from these elements help social workers construct provider-patient relationships that avoid sociocultural dynamics associated with a client’s past traumatic experiences.

This approach can be further strengthened by incorporating an epigenetic perspective that emphasizes the impact of environmental factors such as poverty, abuse, and violence in trauma. Integrating this understanding into one’s practice can better equip social workers to identify and address environmental contributors to a client’s trauma. This poses benefits in the form of facilitating the fostering of supportive environments for care provision to clients and educating clients on the impact and risks associated with remaining in exposure to harmful stimuli. Together, the insights from a combined model can contribute to more holistic and effective social work practice.

In light of these proposed benefits, we encourage social workers to reflect on the following guiding questions when assessing, treating, and evaluating clients suffering from trauma. The questions are listed in order of progression from understanding to applying trauma-informed care:

- What sociocultural and environmental factors have contributed to the client’s individual, interpersonal, and communal traumatic experiences?

- How can I tailor the care I provide to minimize the risk of re-traumatization, given the specific factors implicated in the client’s trauma?

- How can I counsel and support the client on avoiding exposure to trauma-triggering factors as a means of preventing re-traumatization?

- How can I help the client understand the modifiable nature of sociocultural and environmental influences to support a shift from deterministic thinking to non-fatalistic thinking?

Recognizing how environmental factors influence trauma transmission through sociocultural and biological mechanisms can strengthen social worker’s ability to advocate for the affected. This work provided a summary of evidence-based explanations for trauma transmission which offers a strong rationale for justifying the need for systemic social reforms. Factors such as poverty, racism, and inadequate access to social determinants of health play an integral role in perpetuating harmful social learning or possibly contributing to maladaptive epigenetic changes. Regardless of the specifics, a holistic framework supports the development and implementation of interventions that reduce exposures to these risk factors in vulnerable populations. Thus, with this understanding, social workers are equipped to propose and advocate for social changes at the individual, community, and systemic level that limit exposure to risk factors or provide assistance to those most at risk.

6. Conclusions

Social workers are uniquely positioned to share their understanding of trauma with clients in a compassionate way that empowers individuals, families, and communities. This role is especially important given the widespread misinformation in popular media portraying trauma as an unbreakable cycle entrapping generations through unchangeable epigenetic modifications. Such narratives harmfully reinforce fatalism in traumatized patients and risk promoting unfounded ideas. In response to such fallouts, social workers can play a critical role in dispelling these misconceptions and empowering clients to recognize that many of the risk factors involved in trauma can be changed for future generations. By offering an accurate depiction of trauma transmission, social workers not only impact clients but the broader circle of friends, families, and communities affected by similar experiences. Understanding the biology of epigenetics can be daunting for a non-science expert and this review aims to break it down into learnable content.

A review of the literature reveals a clear need to strengthen the connection between psychology and genetics to better characterize the mechanism of trauma transmission. This area of improvement is based on the following two observations: (1) neither discipline alone can capture the full complexity of trauma transmission in human populations, and (2) research in each field is commonly limited by confounding factors rooted in the other. To address these challenges, integrating perspectives from both psychology and molecular science can (i) facilitate the design of more methodological sound studies, (ii) enable more holistic interpretations that account for both psychological and biological dimensions, and (iii) inform balanced trauma-informed policies. Ultimately, the complexity and nuance of the human experience demand a multifaceted approach that can only be achieved through the collaboration of these fields.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.M.O. and P.C.; methodology S.M.O. and P.C.; resources, T.G., S.M.O. and P.C.; writing—original draft preparation, T.G., S.M.O. and P.C.; writing—review and editing, T.G., S.M.O. and P.C.; visualization, T.G., S.M.O. and P.C.; funding acquisition, S.M.O. and P.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by a SSHRC Explore Award and Mount Royal University internal research fund (grant number 103822).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge support from SSHRC and Mount Royal University for funding, and former student Kim Millis for her earlier work with us.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| RNA | Ribonucleic acid |

References

- Abedzadeh-Kalahroudi, Masoumeh, Ebrahim Razi, and Mojtaba Sehat. 2018. The relationship between socioeconomic status and trauma outcomes. Journal of Public Health 40: e431–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allfrey, Vincent G., R. Faulkner, and Alfred E. Mirsky. 1964. Acetylation and methylation of histones and their possible role in the regulation of RNA synthesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 51: 786–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amos, Jackie, Gareth Furber, and Leonie Segal. 2011. Understanding Maltreating Mothers: A Synthesis of Relational Trauma, Attachment Disorganization, Structural Dissociation of the Personality, and Experiential Avoidance. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation 12: 495–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assari, Shervin. 2020. Family Socioeconomic Status and Exposure to Childhood Trauma: Racial Differences. Children 7: 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baduel, Pierre, Iris Sammarco, Rowan Barrett, Marta Coronado-Zamora, Amélie Crespel, Bárbara Díez-Rodríguez, Janay Fox, Dario Galanti, Josefa González, Alexander Jueterbock, and et al. 2024. The evolutionary consequences of interactions between the epigenome, the genome and the environment. Evolutionary Applications 17: e13730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldi, Sandro, Philipp Korber, and Peter B. Becker. 2020. Beads on a string—Nucleosome array arrangements and folding of the chromatin fiber. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology 27: 109–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto-Zarza, Florencia, and Enrique B. Arranz-Freijo. 2022. Family Context, Parenting and Child Development: An Epigenetic Approach. Social Sciences 11: 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, Silvana P., and Steven Offenbacher. 2009. Epigenetics: Connecting Environment and Genotype to Phenotype and Disease. Journal of Dental Research 88: 400–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, Stephen P., and Anindya Dutta. 2002. DNA Replication in Eukaryotic Cells. Annual Review of Biochemistry 71: 333–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjet, Corina, Evelyn Bromet, Elie G. Karam, Ronald C. Kessler, Katie A. McLaughlin, Ayelet M. Ruscio, Vicki Shahly, Dan J. Stein, Maria Petukhova, E. Hill, and et al. 2016. The epidemiology of traumatic event exposure worldwide: Results from the World Mental Health Survey Consortium. Psychological Medicine 46: 327–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bierer, Linda M., Heather N. Bader, Nikolaos P. Daskalakis, Amy Lehrner, Nadine Provençal, Tobias Wiechmann, Torsten Klengel, Iouri Makotkine, Elisabeth B. Binder, Rachel Yehuda, and et al. 2020. Intergenerational Effects of Maternal Holocaust Exposure on FKBP5 Methylation. American Journal of Psychiatry 177: 744–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borschmann, Rohan, Claire Keen, Matthew J. Spittal, David Preen, Jane Pirkis, Sarah Larney, David L. Rosen, Lars Møller, Eamonn O’MOore, Jesse T. Young, and et al. 2024. Rates and causes of death after release from incarceration among 1 471 526 people in eight high-income and middle-income countries: An individual participant data meta-analysis. The Lancet 403: 1779–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bronfenbrenner, Urie, and Pamela A. Morris. 1998. The ecology of developmental processes. In Handbook of Child Psychology. 1: Theoretical Models of Human Development, 5th ed. Edited by Richard M. Lerner. Hoboken: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Bunting, Lisa, Lorna Montgomery, Suzanne Mooney, Mandi MacDonald, Stephen Coulter, David Hayes, and Gavin Davidson. 2019. Trauma Informed Child Welfare Systems—A Rapid Evidence Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16: 2365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cobb, Matthew. 2017. 60 years ago, Francis Crick changed the logic of biology. PLoS Biology 15: e2003243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cogan, Nicola, Dwight Tse, Melanie Finlayson, Samantha Lawley, Jacqueline Black, Rhys Hewitson, Suzanne Aziz, Helen Hamer, and Cherrie Short. 2025. A journey towards a trauma informed and responsive Justice system: The perspectives and experiences of senior Justice workers. European Journal of Psychotraumatology 16: 2441075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combs-Orme, Terri. 2013. Epigenetics and the Social Work Imperative. Social Work 58: 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contractor, Ateka A., Nicole H. Weiss, Prathiba Natesan Batley, and Jon D. Elhai. 2020. Clusters of Trauma Types as Measured by the Life Events Checklist for DSM-5. International Journal of Stress Management 27: 380–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dashorst, Patricia, Trudy M. Mooren, Rolf J. Kleber, Peter J. de Jong, and Rafaele J. C. Huntjens. 2019. Intergenerational consequences of the Holocaust on offspring mental health: A systematic review of associated factors and mechanisms. European Journal of Psychotraumatology 10: 1654065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deichmann, Ute. 2016. Why epigenetics is not a vindication of Lamarckism—And why that matters. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part C: Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences 57: 80–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhar, Gaurab Aditya, Shagnik Saha, Parama Mitra, and Ronita Nag Chaudhuri. 2021. DNA methylation and regulation of gene expression: Guardian of our health. The Nucleus: An International Journal of Cytology and Allied Topics 64: 259–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, Elizabeth J., Peter D. Gluckman, and Peter K. Dearden. 2014. Epigenetics, plasticity, and evolution: How do we link epigenetic change to phenotype? Journal of Experimental Zoology Part B: Molecular and Developmental Evolution 322: 208–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberharter, Anton, and Peter B. Becker. 2002. Histone acetylation: A switch between repressive and permissive chromatin: Second in review series on chromatin dynamics. EMBO Reports 3: 224–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feriante, Joshua, and Naveen P. Sharma. 2025. Acute and Chronic Mental Health Trauma. In StatPearls. St. Petersburg: StatPearls Publishing. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK594231/ (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- First, Michael B., ed. 2022. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5-TR, 5th ed. Text Revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Fitz-James, Maximilian H., and Giacomo Cavalli. 2022. Molecular mechanisms of transgenerational epigenetic inheritance. Nature Reviews Genetics 23: 325–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraiberg, Selma, Edna Adelson, and Vivian Shapiro. 1975. Ghosts in the Nursery. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry 14: 387–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giladi, Lotem, and Terece S. Bell. 2013. Protective factors for intergenerational transmission of trauma among second and third generation Holocaust survivors. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy 5: 384–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, Marvin, Jerard Hurwitz, and Monika Anders. 1963a. The enzymatic methylation of RNA and DNA. I. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 11: 107–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, Marvin, Jerard Hurwitz, and Monika Anders. 1963b. The enzymatic methylation of RNA and DNA, II. On the species specificity of the methylation enzymes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 50: 164–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, Samara, Zara Cooper, Heather Buxton, Sarah Hendrickson, Annie Lewis-O’Connor, Jane Stevens, Lye-Yeng Wong, and Stephanie Bonne. 2021. Trauma-informed care: Recognizing and resisting re-traumatization in health care. Trauma Surgery & Acute Care Open 6: e000815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haering, Stephanie, Marike J. Kooistra, Christine Bourey, Ulziimaa Chimed-Ochir, Nikola Doubková, Chris M. Hoeboer, Emma C. Lathan, Hope Christie, and Anke de Haan. 2024. Exploring transdiagnostic stress and trauma-related symptoms across the world: A latent class analysis. European Journal of Psychotraumatology 15: 2318190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heard, Edith, and Robert A. Martienssen. 2014. Transgenerational Epigenetic Inheritance: Myths and Mechanisms. Cell 157: 95–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, James P., Jessica M. McKlveen, Sriparna Ghosal, Brittany Kopp, Aynara Wulsin, Ryan Makinson, Jessie Scheimann, and Brent Myers. 2016. Regulation of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenocortical Stress Response. Comprehensive Physiology 6: 603–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holliday, Robin, and John E. Pugh. 1975. DNA modification mechanisms and gene activity during development. Science 187: 226–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horsthemke, Bernhard. 2018. A critical view on transgenerational epigenetic inheritance in humans. Nature Communications 9: 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ipsaro, Jonathan J., and Leemor Joshua-Tor. 2015. From guide to target: Molecular insights into eukaryotic RNA-interference machinery. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology 22: 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isobel, Sophie, Melinda Goodyear, and Kim Foster. 2019a. Psychological Trauma in the Context of Familial Relationships: A Concept Analysis. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse 20: 549–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isobel, Sophie, Melinda Goodyear, Trentham Furness, and Kim Foster. 2019b. Preventing intergenerational trauma transmission: A critical interpretive synthesis. Journal of Clinical Nursing 28: 1100–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jäggi, Lena J., Briana Mezuk, Daphne C. Watkins, and James S. Jackson. 2016. The Relationship Between Trauma, Arrest, and Incarceration History Among Black Americans: Findings from the National Survey of American Life. Society and Mental Health 6: 187–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Bilian, and Keith D. Robertson. 2013. DNA Methyltransferases, DNA Damage Repair, and Cancer. In Epigenetic Alterations in Oncogenesis. Edited by Adam R Karpf. New York: Springer, vol. 754, pp. 3–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keynes, Milo, and Tm Cox. 2008. William Bateson, the rediscoverer of Mendel. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 101: 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkbride, James B., Deidre M. Anglin, Ian Colman, Jennifer Dykxhoorn, Peter B. Jones, Praveetha Patalay, Alexandra Pitman, Emma Soneson, Thomas Steare, Talen Wright, and et al. 2024. The social determinants of mental health and disorder: Evidence, prevention and recommendations. World Psychiatry 23: 58–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klibaner-Schiff, Eleanor, Elisabeth M. Simonin, Cezmi A. Akdis, Ana Cheong, Mary M. Johnson, Margaret R. Karagas, Sarah Kirsh, Olivia Kline, Maitreyi Mazumdar, Emily Oken, and et al. 2024. Environmental exposures influence multigenerational epigenetic transmission. Clinical Epigenetics 16: 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostova, Zlatomira, and Vanya L. Matanova. 2024. Transgenerational trauma and attachment. Frontiers in Psychology 15: 1362561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, Subhasree, Edward A. Gonzalez, Pranela Rameshwar, and Jean-Pierre Etchegaray. 2020. Non-Coding RNAs as Mediators of Epigenetic Changes in Malignancies. Cancers 12: 3657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, Jenny K. W., Michael Y. T. Chow, Yu Zhang, and Susan W. S. Leung. 2015. siRNA Versus miRNA as Therapeutics for Gene Silencing. Molecular Therapy-Nucleic Acids 4: e252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaPelusa, Andrew, and Ravi Kaushik. 2025. Physiology, Proteins. In StatPearls. St. Petersburg: StatPearls Publishing. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK555990/ (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Lawrence, Moyra, Sylvain Daujat, and Robert Schneider. 2016. Lateral Thinking: How Histone Modifications Regulate Gene Expression. Trends in Genetics 32: 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letzter-Pouw, Sonia E., and Perla Werner. 2013. The Relationship Between Female Holocaust Child Survivors’ Unresolved Losses and Their Offspring’s Emotional Well-Being. Journal of Loss and Trauma 18: 396–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, Tiffany, Fred Schmidt, and Christopher Mushquash. 2023. A personal history of trauma and experience of secondary traumatic stress, vicarious trauma, and burnout in mental health workers: A systematic literature review. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy 15: S213–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levenson, Jill. 2017. Trauma-Informed Social Work Practice. Social Work 62: 105–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Qiuhui, Kiera Rycaj, Xin Chen, and Dean G. Tang. 2015. Cancer stem cells and cell size: A causal link? Seminars in Cancer Biology 35: 191–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Ruiqi, Jiajun Wu, Haiwei Guo, Weiping Yao, Shuang Li, Yanwei Lu, Yongshi Jia, Xiaodong Liang, Jianming Tang, Haibo Zhang, and et al. 2023. Post-translational modifications of histones: Mechanisms, biological functions, and therapeutic targets. MedComm 4: e292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magruder, Kathryn M., Katie A. McLaughlin, and Diane L. Elmore Borbon. 2017. Trauma is a public health issue. European Journal of Psychotraumatology 8: 1375338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattick, John S., Paulo P. Amaral, Piero Carninci, Susan Carpenter, Howard Y. Chang, Ling-Ling Chen, Runsheng Chen, Caroline Dean, Marcel E. Dinger, Katherine A. Fitzgerald, and et al. 2023. Long non-coding RNAs: Definitions, functions, challenges and recommendations. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 24: 430–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazher, Sania, and Takashi Arai. 2025. Behind bars: A trauma-informed examination of mental health through importation and deprivation models in prisons. European Journal of Trauma & Dissociation 9: 100516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercadante, Anthony A., Manjari Dimri, and Shamim S. Mohiuddin. 2025. Biochemistry, Replication and Transcription. In StatPearls. St. Petersburg: StatPearls Publishing. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK540152/ (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Mersfelder, Erica L., and Mark R. Parthun. 2006. The tale beyond the tail: Histone core domain modifications and the regulation of chromatin structure. Nucleic Acids Research 34: 2653–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, Lisa D, Thuc Le, and Guoping Fan. 2013. DNA Methylation and Its Basic Function. Neuropsychopharmacology 38: 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulligan, Connie J., Edward B. Quinn, Dima Hamadmad, Christopher L. Dutton, Lisa Nevell, Alexandra M. Binder, Catherine Panter-Brick, and Rana Dajani. 2025. Epigenetic signatures of intergenerational exposure to violence in three generations of Syrian refugees. Scientific Reports 15: 5945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murrell, Adele, Vardhman K. Rakyan, and Stephan Beck. 2005. From genome to epigenome. Human Molecular Genetics 14: R3–R10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nachtomy, Ohad, Ayelet Shavit, and Zohar Yakhini. 2007. Gene expression and the concept of the phenotype. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part C: Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences 38: 238–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naumova, Oksana Yu, Sascha Hein, Matthew Suderman, Baptiste Barbot, Maria Lee, Adam Raefski, Pavel V. Dobrynin, Pamela J. Brown, Moshe Szyf, Suniya S. Luthar, and et al. 2016. Epigenetic Patterns Modulate the Connection Between Developmental Dynamics of Parenting and Offspring Psychosocial Adjustment. Child Development 87: 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, Jacob, Heyam Hayder, Yara Zayed, and Chun Peng. 2018. Overview of MicroRNA Biogenesis, Mechanisms of Actions, and Circulation. Frontiers in Endocrinology 9: 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olff, Miranda, Irma Hein, Ananda B. Amstadter, Cherie Armour, Marianne Skogbrott Birkeland, Eric Bui, Marylene Cloitre, Anke Ehlers, Julian D. Ford, Talya Greene, and et al. 2025. The impact of trauma and how to intervene: A narrative review of psychotraumatology over the past 15 years. European Journal of Psychotraumatology 16: 2458406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, Linda, Tina Fraser, Andrew Kitchenham, and Verna McDonald. 2018. Hidden Burdens: A Review of Intergenerational, Historical and Complex Trauma, Implications for Indigenous Families. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma 11: 173–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orton, Sarah M., Kimberly Millis, and Peter Choate. 2023. Epigenetics of Trauma Transmission and Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder: What Does the Evidence Support? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20: 6706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otterdijk, Sanne D., and Karin B. Michels. 2016. Transgenerational epigenetic inheritance in mammals: How good is the evidence? The FASEB Journal 30: 2457–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pai, Anushka, Alina M. Suris, and Carol S. North. 2017. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in the DSM-5: Controversy, Change, and Conceptual Considerations. Behavioral Sciences 7: 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, Terence Yc, Annabel K. Short, Timothy W. Bredy, and Anthony J. Hannan. 2017. Transgenerational paternal transmission of acquired traits: Stress-induced modification of the sperm regulatory transcriptome and offspring phenotypes. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences 14: 140–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Passarge, Eberhard. 2021. Origins of human genetics. A personal perspective. European Journal of Human Genetics 29: 1038–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peaston, Anne E., and Emma Whitelaw. 2006. Epigenetics and phenotypic variation in mammals. Mammalian Genome 17: 365–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, Marcos Francisco, and Ben Lehner. 2019. Intergenerational and transgenerational epigenetic inheritance in animals. Nature Cell Biology 21: 143–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesole, Graziano. 2008. What is a gene? An updated operational definition. Gene 417: 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piovesan, Allison, Maria Chiara Pelleri, Francesca Antonaros, Pierluigi Strippoli, Maria Caracausi, and Lorenza Vitale. 2019. On the length, weight and GC content of the human genome. BMC Research Notes 12: 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portela, Anna, and Manel Esteller. 2010. Epigenetic modifications and human disease. Nature Biotechnology 28: 1057–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramo-Fernández, Laura, Anna Schneider, Sarah Wilker, and Iris-Tatjana Kolassa. 2015. Epigenetic Alterations Associated with War Trauma and Childhood Maltreatment. Behavioral Sciences & the Law 33: 701–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raz, Aviad, Gaëlle Pontarotti, and Jonathan B. Weitzman. 2019. Epigenetic metaphors: An interdisciplinary translation of encoding and decoding. New Genetics and Society 38: 264–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riggs, Arthur D. 1975. X inactivation, differentiation, and DNA methylation. Cytogenetic and Genome Research 14: 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, Dorothy E. 2023. Torn Apart: How the Child Welfare System Destroys Black Families—And How Abolition Can Build a Safer World (First Trade Paperback Edition). New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Roth, Tania L. 2013. Epigenetic mechanisms in the development of behavior: Advances, challenges, and future promises of a new field. Development and Psychopathology 25: 1279–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scorza, Pamela, Cristiane S. Duarte, Alison E. Hipwell, Jonathan Posner, Ana Ortin, Glorisa Canino, Catherine Monk, and Program Collaborators for Environmental Influences on Child Health Outcomes. 2019. Research Review: Intergenerational transmission of disadvantage: Epigenetics and parents’ childhoods as the first exposure. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines 60: 119–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirvaliloo, Milad. 2022. The Landscape of Histone Modifications in Epigenomics Since 2020. Epigenomics 14: 1465–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, Brittany, Connor Tupper, and Nora M. Al Aboud. 2025. Genetics, DNA Packaging. In StatPearls. St. Petersburg: StatPearls Publishing. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534207/ (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Stares, P. 2025. Conflicts to Watch 2025 (Preventive Priorities Survey Results). New York: Council on Foreign Relations. Available online: https://www.cfr.org/report/conflicts-watch-2025 (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Statello, Luisa, Chun-Jie Guo, Ling-Ling Chen, and Maite Huarte. 2021. Gene regulation by long non-coding RNAs and its biological functions. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 22: 96–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travers, Andrew, and Georgi Muskhelishvili. 2015. DNA structure and function. The FEBS Journal 282: 2279–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. 2015. Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future: Summary of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconcilliation Commission of Canada. Winnipeg: Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Van Ameringen, Michael, Catherine Mancini, Beth Patterson, and Michael H. Boyle. 2008. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in Canada. CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics 14: 171–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddington, Conrad. 1942. Canalization of development and the inheritance of acquired characters. Nature 150: 563–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Jian-Wei, Kai Huang, Chao Yang, and Chun-Sheng Kang. 2017. Non-coding RNAs as regulators in epigenetics. Oncology Reports 37: 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yehuda, Rachel, Amy Lehrner, and Linda M. Bierer. 2018. The public reception of putative epigenetic mechanisms in the transgenerational effects of trauma. Environmental Epigenetics 4: dvy018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yehuda, Rachel, and Amy Lehrner. 2018. Intergenerational transmission of trauma effects: Putative role of epigenetic mechanisms. World Psychiatry 17: 243–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yehuda, Rachel, Nikolaos P. Daskalakis, Linda M. Bierer, Heather N. Bader, Torsten Klengel, Florian Holsboer, and Elisabeth B. Binder. 2016. Holocaust Exposure Induced Intergenerational Effects on FKBP5 Methylation. Biological Psychiatry 80: 372–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Zuanning, and Huilin Li. 2020. Molecular mechanisms of eukaryotic origin initiation, replication fork progression, and chromatin maintenance. The Biochemical Journal 477: 3499–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Yanjun, Zhongxing Sun, Junqi Jia, Tianjiao Du, Nachuan Zhang, Yin Tang, Yuan Fang, and Dong Fang. 2021. Overview of Histone Modification. In Histone Mutations and Cancer. Edited by Dong Fang and Junhong Han. Singapore: Springer, vol. 1283, pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.