Abstract

Youth from racial minority backgrounds frequently report encountering racial discrimination within their school. These experiences can create additional barriers to their pursuit of higher education. This study explored whether critical thinking can protect and enhance youth college aspirations despite discrimination. We examined whether critical thinking protects against the impact of racial discrimination on beliefs about future college plans in a racially/ethnically diverse sample of 189 adolescents (Mage = 14.47, SD = 1.402, 66.8% female) using a cross-sectional approach. Results indicated that among adolescents with low and moderate critical thinking skills, higher levels of in-school racial discrimination were linked to lower beliefs in their future college attendance. This suggests that in environments where racial discrimination is prevalent, individuals with lower critical thinking skills are more susceptible to negative effects on their college expectations. Conversely, for adolescents with high critical thinking skills, the relationship between in-school racial discrimination and beliefs about college plans was not significant. These findings emphasize the importance of developing critical thinking skills through interventions and policies to mitigate the adverse effects of in-school racial discrimination and to promote college access and success among underrepresented racial minority youth.

1. Introduction

Adolescence is a critical period marked by significant growth and changes in physical, social, and cognitive domains, making it pivotal for youth to navigate potential challenges (Alderman and Breuner 2019; Galván 2019). For adolescents from racially and ethnically marginalized backgrounds, one of the most persistent challenges is racial discrimination—especially within school environments where identity development and educational aspirations converge (Benner et al. 2018; Gale 2020). Over the past five years, research has increasingly documented the enduring impact of in-school discrimination on adolescents’ well-being and academic trajectories (Azagba et al. 2025; Baysu et al. 2024; Brissett et al. 2025; Kim et al. 2025). These studies show that discrimination not only undermines academic performance and school engagement but also contributes to poorer mental health, diminished school connectedness, and lower aspirations for postsecondary education.

In-school racial discrimination encompasses a wide range of experiences, from biased disciplinary practices and exclusionary classroom interactions to microaggressions from peers and educators (Benner and Graham 2013; Gale and Dorsey 2020). Recent qualitative research further highlights the complexity of these experiences. For instance, Goldie et al. (2025) found that Black middle school students describe discrimination as both overt and subtle, deeply affecting their sense of belonging and trust in teachers. Similarly, McKinnon et al. (2024) argue that racism in schools persists through structural and institutional mechanisms, such as curricular omission and differential treatment, which normalize racial inequities. Together, these findings reinforce that schools are not neutral spaces; they are sociocultural contexts where power, race, and opportunity intersect, shaping students ‘psychological and educational outcomes.

Critical thinking has emerged as a key protective factor that supports adolescents’ development in the face of risk (Fernandez and Benner 2022; Zajda 2022). It enables youth to question assumptions, evaluate evidence, and make reasoned decisions, fostering greater autonomy and resilience. Research shows that critical thinking contributes to positive developmental outcomes, including stronger academic motivation, improved self-regulation, and enhanced problem-solving skills (Ghazivakili et al. 2014). Through these cognitive capacities, adolescents can better navigate complex social and academic environments, reducing susceptibility to negative influences and risky behaviors. While critical thinking has been consistently linked to improved educational outcomes—such as higher achievement and greater persistence—its role in shaping how adolescents envision their futures remains underexplored. Understanding whether critical thinking helps youth sustain confidence in their long-term educational goals, particularly when confronted with discriminatory or inequitable experiences, is therefore essential. This study extends prior research by examining critical thinking as a potential mechanism that strengthens adolescents’ future orientation and college-going aspirations in the face of in-school racial discrimination.

2. Guiding Theoretical Framework

Our study uses risk and resilience frameworks to examine the factors influencing adolescents’ beliefs about future college attendance. According to these frameworks, risk factors can raise the chance of negative outcomes, while protective factors help reduce or counteract these effects (Fergus and Zimmerman 2005; Zimmerman et al. 2013). Fergus and Zimmerman (2005) describe resilience as the process of overcoming risk, highlighting the importance of risk and protective factors in shaping results. These frameworks help us understand how individuals show adaptive qualities after facing various types of adversity and trauma (Greene 2017). Therefore, the framework informs our exploration of how students’ critical thinking skills interact with the relationship between their experiences with in-school discrimination and their college aspirations. While in-school racial discrimination is a risk factor that can hinder students’ educational progress, the theory suggests that critical thinking may lessen its impact on students’ college ambitions by allowing students to critically assess discriminatory experiences, challenge negative assumptions, and stay focused on long-term academic goals. This positions critical thinking as an internal coping skill and, therefore, a resilience factor. Although there is no universally accepted definition of resilience, the literature (Greene 2017) consistently links it to concepts such as coping, recovery, perseverance, and persistence.

Benard (1991) categorizes protective factors for at-risk children as personal, family, and environmental, based on developmental theory emphasizing personal characteristics and contextual influences. Bronfenbrenner and Morris (2006) state that development is affected by proximal and distal experiences, with schools becoming more influential in adolescence (Hamm and Zhang 2010). Personal protective factors include behaviors and beliefs that promote resilience, such as problem-solving skills that help children navigate risks and foster better adult outcomes. Beliefs about oneself or one’s environment also contribute to resilience; for example, racial identity dimensions can lessen racial discrimination’s impact on academic performance (Bynum et al. 2008; Smalls et al. 2007). Since academic success and engagement are linked to perceptions of future college success, protective factors reducing in-school racial bias support positive future orientation. The study uses the protective factor model, proposing assets can offset risks’ negative effects, especially among lower socioeconomic youth facing school racial discrimination.

2.1. In-School Racial Discrimination as a Risk Factor

Racial discrimination within school environments presents profound challenges to adolescents’ adjustment and pursuit of positive educational outcomes, differing in important ways from discriminatory experiences outside of school (DuBois et al. 2002). Context-specific risks—such as those embedded in school climates—can impede youths’ ability to develop the skills and confidence necessary for success (Gale and Dorsey 2020). In-school racial discrimination encompasses discriminatory behaviors, practices, or attitudes within educational settings that target students based on race or ethnicity (Gale 2020). These experiences can include inequitable grading, biased disciplinary practices, exclusion from academic opportunities, and verbal or physical harassment by teachers or peers (Benner and Graham 2013; Felix and You 2011). Such patterns erode students’ sense of belonging and academic engagement, with especially harmful consequences for racially and ethnically marginalized youth.

A growing body of research has demonstrated that in-school discrimination, whether overt or subtle, undermines adolescents’ academic achievement, self-concept, motivation, and belief in their competence (Benner and Graham 2013; Benner et al. 2018; Chavous et al. 2008; Gale and Dorsey 2020). These effects extend across multiple racial and ethnic groups. Latinx adolescents, for example, often experience bias related to language use or immigration status, which predicts lower motivation and weaker school belonging (Benner and Wang 2014; Tummala-Narra and Claudius 2013). Asian American students may be stereotyped as “perpetual foreigners” or held to model minority expectations, experiences that contribute to elevated stress and reduced help-seeking (Cheon and Yip 2019). Indigenous and Native American youth confront systemic discrimination in school policies and curricula that invalidate their cultural identity, resulting in disengagement and lower academic persistence (Whitbeck et al. 2004).

Among youth of color, the cumulative impact of discrimination intersects with socioeconomic and structural inequities that constrain opportunity and shape adolescents’ perceptions of self-efficacy (Benner et al. 2018; Fernandez and Benner 2022). Collectively, these youth navigate educational systems that may fail to affirm their cultural backgrounds or provide equitable access to resources—making the development of protective cognitive and socioemotional skills, such as critical thinking, particularly salient. These patterns underscore that in-school racial discrimination does not occur in isolation but reflects broader structural inequities within educational systems that differentially allocate resources, opportunities, and disciplinary outcomes by race. Recognizing this structural context is essential for understanding how discrimination undermines educational equity and why protective cognitive resources, such as critical thinking, may play a vital role in helping youth of color navigate and challenge these systemic barriers. Understanding the shared and distinct experiences of discrimination across racial and ethnic groups allows for a more comprehensive assessment of how critical thinking functions as a resilience factor. Therefore, while this study builds on prior work focused on Black adolescents, its implications extend to the broader population of racially and ethnically diverse youth who face structural barriers within educational settings.

2.2. Future College-Going Beliefs as a Dimension of Future Orientation

Adolescents’ beliefs about attending college are a key expression of future orientation, capturing the ways in which youth translate long-term aspirations into concrete educational goals. Future orientation, the ability to envision and plan for long-term goals, plays a pivotal role in shaping adolescents’ decisions, behaviors, and overall well-being (Johnson et al. 2014; So et al. 2018). Adolescents with a strong sense of future orientation tend to set goals, make purposeful choices, and persist in actions that align with their aspirations. This forward-looking mindset supports academic achievement, encourages healthy lifestyle choices, and fosters positive relationships (So et al. 2016). It also offers a sense of purpose and direction, enabling youth to navigate challenges with resilience and determination (Seginer 2009).

A key dimension of future orientation is adolescents’ beliefs about their future educational attainment (Chen and Vazsonyi 2013; Ochoa and Constantin 2023; Seginer and Mahajna 2018). These beliefs are consistently linked to measurable academic outcomes; for example, stronger future orientation has been associated with higher final grades in subjects such as mathematics, Arabic, and English (Gale 2021; Ochoa and Constantin 2023). Within this framework, college-going beliefs represent an important dimension of adolescents’ future orientation, reflecting both their expectations and confidence in pursuing postsecondary education. Such beliefs are shaped by a complex interplay of individual, familial, and contextual factors, including school climate, socioeconomic status, and perceived opportunities for advancement (Beal and Crockett 2010; Kerpelman et al. 2012).

For racially and ethnically minoritized youth, these beliefs may hold even greater significance, as they are often formed in the context of structural barriers and discriminatory experiences that can constrain access to opportunity and challenge self-efficacy regarding educational attainment (O’Hara et al. 2012; Seginer and Mahajna 2018). For instance, O’Hara et al. (2012) found that perceived racial discrimination among African American adolescents from low-income backgrounds was strongly associated with lower expectations for college enrollment.

Further, prior research has shown that experiences of racial bias and inequity can diminish adolescents’ sense of belonging and academic motivation, while culturally affirming relationships and messages from family, mentors, and community can strengthen their educational aspirations (Gale 2020; Neblett et al. 2006; Wang and Eccles 2013). Thus, understanding college-going beliefs among youth of color requires attention to both systemic inequities and the cultural and psychological processes that sustain resilience in the face of them.

Building on this body of work, the present study focuses on future college-going beliefs, a specific expression of future orientation reflecting adolescents’ confidence in and commitment to attending college. This perspective aligns with the college aspirations and expectations literature, which emphasizes both the motivational and structural factors shaping students’ postsecondary trajectories. We examine how in-school racial discrimination relates to these beliefs and whether critical thinking can act as a protective factor that sustains or strengthens college-going aspirations in the face of discriminatory experiences.

2.3. The Protective Role of Critical Thinking

As incidents of prejudice and racial discrimination in schools continue to rise, it is critical to identify protective factors that buffer the impact of these harmful experiences (Hong et al. 2021). Adolescents who face prejudice, social exclusion, and in-school discrimination are at increased risk for compromised psychological well-being (Chavous et al. 2008; Costello and Dillard 2019), lower academic achievement (Banerjee et al. 2018; Chavous et al. 2008), and diminished aspirations for higher education (Banerjee et al. 2018). One such protective factor is critical thinking, which has been established in the literature as a key contributor to student achievement and educational outcomes (AkbariLakeh et al. 2018) and as a preventative approach to addressing discrimination in schools (Zajda 2022).

Although critical thinking is frequently conceptualized as a cognitive or academic skill, it also represents a broader metacognitive capacity that allows individuals to reflect on, evaluate, and challenge their social realities (Facione 2020; Lai 2011). In the present study, critical thinking was measured using adolescents’ self-perceptions of their critical thinking ability. While self-report measures do not capture actual reasoning performance, they reflect an individual’s confidence in and awareness of their ability to think critically, components that are themselves theoretically meaningful. Self-perceived critical thinking has been linked to higher motivation, persistence, and engagement in academic and social problem-solving (Heijltjes et al. 2014; Phan 2010). Thus, this measure captures an important dimension of adolescents’ metacognitive self-efficacy, their belief in their ability to question assumptions, assess evidence, and make reasoned judgments, which may be particularly relevant when interpreting and responding to discriminatory experiences. Future research, however, should complement such self-perceived assessments with performance-based or observational measures to more fully capture both the cognitive and behavioral dimensions of critical thinking (Ku 2009).

Past research has documented the influence of critical thinking on educational outcomes. Nur’azizah et al. (2021) reported that among 178 Indonesian 11th graders, higher critical thinking skills were associated with greater learning motivation and academic performance. In the United States, most research on critical thinking focuses on college-aged populations (e.g., Ghazivakili et al. 2014; Nold 2017; Shirazi and Heidari 2019), creating a gap in our understanding of its role among middle and high school students. More recently, Hwang et al. (2023) found that higher critical thinking skills (including inductive and deductive reasoning) predicted improved standardized science assessment scores among 2000 5th graders in 47 Midwestern schools, highlighting the developmental benefits of building these skills early. Yet, research is still needed to explore how critical thinking can buffer against the negative effects of in-school racial discrimination on educational outcomes.

Prior studies have shown that adolescents also use critical thinking in the face of everyday racial discrimination, including biases encountered in community spaces, online environments, and interactions with broader institutions. For example, Hope et al. (2015) found that Black high school students engaged in critical reflection to analyze and challenge structural inequities encountered inside and outside school, supporting their academic engagement and persistence. Likewise, Fernandez and Benner (2022) demonstrated that psychological resources such as critical thinking can mitigate the harmful effects of both in-school and everyday discrimination on adolescents’ academic well-being. Given that in-school discrimination is directly tied to students’ learning environments, relationships with teachers and peers, and sense of belonging, these skills are especially vital. By encouraging multi-perspective thinking—whether through transformative pedagogy at school or through reflective conversations at home—youth can better evaluate complex issues, engage in empathetic discourse, and resist internalizing discriminatory messages. This dual emphasis on family and school environments underscores the importance of coordinated efforts to cultivate critical thinking as a resilience-building tool for adolescents navigating educational inequities.

It is important to note that framing critical thinking as a protective factor does not imply that youth bear responsibility for mitigating the consequences of racial discrimination. Rather, critical thinking develops through the social and educational contexts that encourage reflection, inquiry, and critical consciousness. These skills can help adolescents make sense of inequitable experiences and maintain a sense of agency and hope, but they do not erase the structural realities that create such experiences. The responsibility for reducing and eliminating racial discrimination rests with educational systems and broader institutions. Thus, critical thinking should be understood not as a personal trait that shields youth from harm, but as a contextually nurtured skill that interacts with supportive environments to promote resilience and advocacy.

3. The Present Study

This study examines how critical thinking may protect adolescents from the harmful effects of in-school racial discrimination on their aspirations for higher education. Guided by risk and resilience frameworks, we investigate whether adolescents with stronger critical thinking skills are less susceptible to the negative influence of discriminatory experiences on their college-going beliefs. Although research consistently links critical thinking to academic motivation and achievement (Nur’azizah et al. 2021), little is known about its protective function within the context of racial discrimination in schools. Building on prior work (Seginer and Mahajna 2018), we test whether critical thinking moderates the association between in-school discrimination and future educational aspirations. Critical thinking may act as a resilience resource by enabling youth to interpret and manage discriminatory experiences through reflection, problem-solving, and cognitive coping (American Psychological Association 2018). We hypothesize that adolescents with higher critical thinking skills will show a weaker negative association between discrimination and college-going beliefs. Through this inquiry, we aim to identify cognitive strengths that help adolescents navigate inequitable educational environments and sustain aspirations for higher education.

4. Method

4.1. Procedures

This study drew on data from adolescents participating in a pre-college initiative serving students from public middle and high schools in lower socioeconomic status (SES) and urban areas within a large state on the East Coast of the United States in the summer of 2020. Recruitment occurred across five public school districts representing diverse community contexts, ranging from highly urban centers to smaller suburban areas. These districts vary substantially in income levels and educational resources, with some communities reporting that over 70% of students qualify for free or reduced-price lunch, while others have rates closer to 30–50%. Graduation rates across these districts similarly differ, from below 70% in economically challenged urban areas to over 90% in suburban ones, illustrating structural disparities in educational opportunity.

Participants were selected through a competitive application process that emphasized academic promise, financial need, and first-generation college potential. Eligibility required students to attend a public school in one of the participating districts, demonstrate good academic standing, and meet the federal criteria for free or reduced-price lunch. Students also provided teacher or community recommendations as part of the application process. Once admitted, participants received sustained mentoring and academic support beginning in seventh grade and continuing through high school, including summer enrichment, tutoring, and exposure to college and career opportunities.

4.2. Participants

Data for the current study were drawn from surveys administered during students’ participation in the program. Parental consent and student assent were obtained prior to participation. Although longitudinal data have been collected across multiple years, the current analyses utilize the most complete cross-sectional dataset available to ensure sufficient sample size and data quality for the study’s primary constructs. Earlier and later waves of data collection contained substantial missing information for one or more key variables, including measures of in-school racial discrimination, critical thinking, and future college-going beliefs, which limited their analytic utility. The selected dataset, therefore, represents the wave in which all focal variables were assessed comprehensively and consistently across participants, providing the most reliable and interpretable results for the present analyses.

The analytic sample included 189 adolescents between the ages of 13 and 17 years (M = 14.47, SD = 1.40), 66.8% of whom were female. Participants represented a racially and ethnically diverse group: 46.8% identified as Latinx/Hispanic, 24.9% as Black/African American, 8.9% as Asian, 1.6% as American Indian/Alaska Native, 1.3% as Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, 11.1% as White (including Middle Eastern), and 4.4% as multiracial or other backgrounds. Given the eligibility criteria, the entire sample comprised adolescents from low socioeconomic households.

The current study participants were American Indian/Alaska Native (1.6%), Asian (8.9%), Black/African American (24.9%), Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander (1.3%), White (including Middle Eastern) (11.1%), Latino/Hispanic (46.8%), and Other Race/Ethnicity (4.4%). Given the income requirements for the pre-college program, the entire sample consists of adolescents from low socioeconomic backgrounds.

4.3. Measures

In-school Racial Discrimination. Adolescents reported the frequency of racial discrimination experiences from teachers and peers using a 5-item scale (α = 0.857) adapted from the Maryland Adolescent Development in Context Study (MADICS) research team (Cogburn et al. 2011). A sample item is, “You get disciplined more harshly by teachers than other kids do because of your race/ethnicity?” Items were rated on a Likert scale, with higher scores indicating greater perceived in-school racial discrimination.

Future College-going Beliefs. Adolescents reported their expectations about attending college in the future. This 3-item scale (α = 0.865) was developed by the program as part of the larger initiative from which the present dataset was drawn and captures students’ confidence and perceived likelihood of pursuing postsecondary education. A sample item is, “I believe I will get into college.” Responses were given on a four-point scale ranging from totally disagree (1) to totally agree (4), with higher scores reflecting stronger beliefs in one’s likelihood of attending college.

Critical Thinking. Critical thinking refers to the ability to actively and skillfully analyze, evaluate, and compare ideas to form reasoned judgments and make informed decisions. Adolescents’ self-reported critical thinking skills were measured using the 5-item Critical Thinking subscale from the Skills for Everyday Living Survey (Perkins and Mincemoyer 2002) (α = 0.771). A sample item is, “I compare ideas when thinking about a topic.” Items were rated on a Likert scale, with higher scores representing greater perceived critical thinking skills.

Demographic control variables. Adolescents self-reported their age, gender, and race/ethnicity. Because the race/ethnicity variable reflected the number of categories each student endorsed, it was treated as a continuous covariate rather than a set of dummy-coded indicators; therefore, no reference group was used in the analysis. They also provided their grade point average (GPA) from the previous academic year. Reported GPAs ranged from 1.5 to 4.0 and were recorded using a 5-point scale, where 1 represented a GPA of 1.0 or lower and 5 represented a GPA between 3.5 and 4.0. Higher scores indicated stronger academic performance.

4.4. Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated to summarize participant demographics and key study variables, including measures of in-school racial discrimination, critical thinking, and future college-going beliefs. Bivariate correlations were computed to examine the relationships among the primary variables of interest and to assess potential covariates. To address the study’s primary research question, whether critical thinking moderates the association between in-school racial discrimination and future college-going beliefs, multiple regression analyses were conducted in a single step using IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 29). The moderation model was estimated using Hayes’ PROCESS macro (Model 1; Hayes 2013), which tests conditional effects through ordinary least squares (OLS) regression. All variables, including the independent variable (in-school racial discrimination), moderator (critical thinking), covariates (age, gender, socioeconomic status), and the interaction term (centered variables multiplied), were entered simultaneously. Significant interactions were probed using simple slopes analysis to determine the nature of the moderating relationship.

5. Results

5.1. Descriptives

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics of key study variables for the full sample. On average, adolescents reported a score of 1.20 (SD = 0.43) on the in-school racial discrimination scale, ranging from 1 to 5, suggesting that in-school racial was present but not prevalent among the study participants. The average future college-going score was 3.78 (SD = 0.38) on a scale ranging from 1 to 4. This indicates a strong desire among adolescents to attend college. The average critical thinking score was 3.18 (SD = 0.48) on a scale ranging from 1 to 4. This suggests that adolescents possess a relatively high level of critical thinking skills. Finally, critical thinking positively correlated with future college-going (r = 0.281, p < 0.01), while critical thinking did not correlate with in-school racial discrimination. Future college-going also did not correlate with future college-going.

Table 1.

Correlations and Descriptives for Key Study Variables.

5.2. Regression Analyses

The main research question was tested by estimating a moderated model (Model 1) in the PROCESS macro for SPSS (Hayes 2013). In the moderated model, X is the independent variable (in-school racial discrimination), Y is the dependent variable (future college-going), and W is the moderator (critical thinking). All predictors, including the independent variable, moderator, covariates, and the interaction term, were entered into the model simultaneously. PROCESS was used to estimate conditional effects and interaction terms through ordinary least squares (OLS) regression. Bootstrapping was not employed for this analysis, as the focus was on testing the overall moderated model and the significance of the interaction term using traditional inferential statistics. The results of these analyses are reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

Moderated Effects of Critical Thinking on the Link In-school Racial Discrimination and Future College-Going (N = 189).

The overall regression model was significant F (7, 181) = 5.399, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.173. None of the demographic controls (gender, age, race/ethnicity, and GPA) were related to future college-going. In addition, critical thinking was not directly related to future college-going (β = −0.145, p = 0.314). However, in-school racial discrimination was negatively associated with future college-going (β = −1.157, p < 0.01). Finally, the interaction term of in-school racial discrimination and critical thinking was significantly associated with future college-going (β = 0.323, p < 0.01).

5.3. Post Hoc Analyses

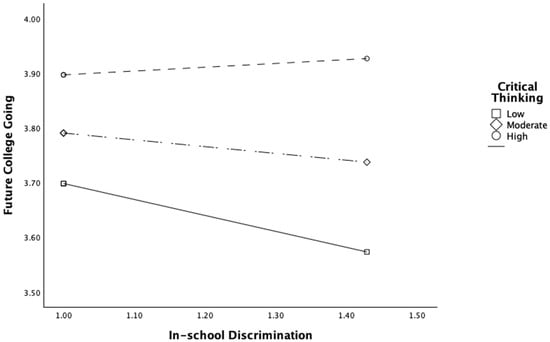

To further examine the significant interaction between in-school racial discrimination and critical thinking, post hoc simple slopes analyses were conducted using the PROCESS macro in SPSS (Model 1; Hayes 2013). The associations between in-school racial discrimination and future college-going beliefs were estimated at one standard deviation below the mean (low), at the mean (moderate), and one standard deviation above the mean (high) levels of critical thinking.

As illustrated in Figure 1, for adolescents with low levels of critical thinking, in-school racial discrimination was significantly and negatively associated with future college-going beliefs (B = −0.63, p < 0.01). For those with moderate levels of critical thinking, the negative association remained significant but weaker (B = −0.33, p < 0.05). In contrast, for adolescents with high levels of critical thinking, the relationship between in-school racial discrimination and future college-going beliefs was nonsignificant (B = 0.04, p = 0.81).

Figure 1.

Conditional effects of critical thinking on the link between in-school discrimination and future college-going.

6. Discussion

Racial discrimination in school environments remains a significant concern for many adolescents, highlighting the need for efforts to protect their mental health. Additionally, discrimination experiences at school can sometimes discourage some adolescents from pursuing higher education (Benner et al. 2018; Fernandez and Benner 2022). These experiences often send harmful messages about students’ worth, competence, and potential, which can have long-lasting effects on their educational and career goals (Hope et al. 2015). Our results provide valuable insights into the complex relationship between in-school racial discrimination, critical thinking, and adolescents’ beliefs about college attendance in the future. In line with our hypothesis, higher levels of critical thinking helped mitigate the negative impact of racial discrimination at school on future college intentions. Thus, these findings suggest another form of support for adolescents facing these challenges.

6.1. In-School Racial Discrimination and Future College-Going

Consistent with prior research suggesting that racial discrimination could discourage some Black students from pursuing higher education (Zajda 2022), our findings showed a negative link between in-school racial discrimination and adolescents’ beliefs about attending college in the future. Previous studies have established a connection between perceived racial discrimination and educational outcomes, especially among African American youth from disadvantaged backgrounds (O’Hara et al. 2012; Zajda 2022). Building on this, our study specifically examined how experiences of in-school racial discrimination affected adolescents’ beliefs about their educational future. This emphasized the widespread impact of discriminatory experiences within educational settings on students’ aspirations and highlighted the need to address systemic inequalities to create an environment that supports academic success and future goals.

Furthermore, our study deepened the research on future orientation by examining how sociocultural factors, such as racial discrimination, affect adolescents’ beliefs about their educational prospects. By identifying and understanding these factors, educators and policymakers can create targeted interventions to lessen the damaging effects of in-school racial discrimination on students’ academic ambitions and promote equal access to higher education for all. Such interventions are crucial not only for reducing risks but also for fostering resilience, maintaining motivation, and ensuring more equitable access to higher education opportunities. Ultimately, placing future orientation within the larger context of structural inequities highlights the importance of systemic changes in education practice and policy to ensure every adolescent can envision and pursue meaningful postsecondary pathways.

Although critical thinking was not directly associated with future college-going beliefs, its moderating effect suggests that these cognitive skills may be most relevant when adolescents encounter challenging or discriminatory experiences. This pattern is consistent with resilience models, which posit that protective factors often exert their influence in the presence of contextual risk rather than as universal predictors of positive outcomes (Fergus and Zimmerman 2005). In this sense, critical thinking may serve as a contextually activated resource—helping adolescents make meaning of unfair treatment, maintain agency, and sustain educational aspirations despite discrimination. Such findings underscore the importance of understanding critical thinking not only as a general academic asset but also as a capacity that can buffer youth against the psychological and motivational costs of in-school inequities.

6.2. Critical Thinking as a Protective Factor

Our findings highlight the importance of critical thinking in influencing how adolescents respond to in-school racial discrimination and their beliefs about future educational opportunities. Among adolescents with lower and moderate critical thinking skills, experiences of racial discrimination at school were linked to a reduced belief in future college attendance, showing a vulnerability to the harmful effects of discriminatory environments on educational ambitions. This emphasizes the need to address disparities in critical thinking abilities to help individuals better navigate and resist the negative impacts of discrimination in schools. Interestingly, for adolescents with higher critical thinking skills, the link between in-school racial discrimination and beliefs about future college attendance was not significant. As previous research (e.g., Seginer and Mahajna 2018; Zajda 2022) suggests, strong critical thinking skills serve as a protective factor, enabling individuals to challenge and lessen the influence of discriminatory experiences on their educational goals.

Our findings further highlight the potential of critical thinking as a resilience factor, providing adolescents with the cognitive and evaluative resources to confront and overcome systemic barriers to educational achievement (Zajda 2022). Additionally, they point to the importance of interventions aimed at developing critical thinking skills among adolescents, especially in settings where racial discrimination is common, to promote fair access to education and empower individuals to pursue their academic goals despite challenges. Further research is needed to explore how critical thinking functions as a buffer against the negative effects of in-school discrimination and to guide targeted interventions that build resilience and foster positive educational outcomes for marginalized youth.

While these findings suggest that critical thinking may serve as a cognitive resource that shapes how adolescents interpret and respond to racial discrimination, they should not be interpreted as placing the burden of adaptation on youth themselves. Rather, these results underscore the importance of schools and communities fostering environments that cultivate critical thinking alongside systemic efforts to address inequities directly. Developing adolescents’ capacity for reflection and analysis may support their well-being and academic engagement, but institutional and policy-level interventions remain essential for dismantling the conditions that produce discrimination in the first place.

6.3. Interpreting Demographic Findings

An unexpected finding in this study was that none of the demographic covariates, gender, age, race/ethnicity, or GPA, were significantly associated with adolescents’ future college-going beliefs. Given the diversity of the sample, this result suggests that shared experiences of navigating educational environments shaped by systemic inequities may transcend differences across specific racial or gender groups. While prior research has shown that students’ school experiences often vary by demographic background (Benner et al. 2018; Eccles and Wigfield 2020), it is possible that, in this context, the common reality of in-school discrimination among youth of color minimized between-group variation. This aligns with evidence that minority stress processes, such as vigilance, stereotype threat, and reduced belonging, can manifest similarly across marginalized groups in settings where institutional support is perceived as limited (Neblett et al. 2006; Seaton et al. 2008).

It is also important to consider that in-school racial discrimination may carry different meanings across racial groups, particularly within the current racial climate in the United States. For racially marginalized youth, perceptions of discrimination often reflect ongoing, lived experiences of interpersonal and structural inequity. In contrast, among some White adolescents, perceptions of being treated “unfairly” may sometimes be shaped less by direct experiences and more by broader sociopolitical narratives circulating in their environments. These qualitative differences in how adolescents interpret and attribute discriminatory treatment help explain why perceptions of discrimination, rather than racial category alone, emerged as the more robust predictor in this analysis.

Another explanation relates to the role of racial socialization and culturally grounded coping mechanisms that may buffer the impact of demographic factors on students’ educational beliefs. Research suggests that messages emphasizing cultural pride, preparation for bias, and community responsibility foster resilience in the face of discrimination (Hughes et al. 2006; Neblett et al. 2012). Although not directly measured in this study, such processes may have reduced differences by race and gender once experiences of discrimination and critical thinking were accounted for. Moreover, self-reports of in-school racial discrimination likely capture a more direct measure of inequity than demographic identifiers alone. Thus, when discrimination and cognitive coping processes are modeled together, demographic variables may explain little additional variance, highlighting that lived experiences of bias, rather than categorical group membership, are more proximally related to students’ perceptions of their educational futures.

6.4. Limitations and Future Directions

While this study advances understanding of how in-school racial discrimination relates to adolescents’ future college-going beliefs, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the sample consisted of middle-school-aged adolescents participating in a college access program, which may limit generalizability. These youth may be more motivated to pursue college and may also have access to additional supports that help sustain their aspirations despite experiences of discrimination. Because the sample reflects both a specific developmental period and a specialized program context, the findings may not generalize to older youth whose cognitive maturity, racial identity development, and interpretations of discriminatory experiences may differ. Future research should therefore draw on more diverse samples—including students outside structured programs and across a wider range of age groups—to strengthen the external validity of these findings.

Second, the cross-sectional design precludes causal inference, making it impossible to determine the temporal sequence among in-school racial discrimination, critical thinking, and college-going beliefs. Longitudinal research is needed to test whether critical thinking prospectively buffers the effects of discrimination and whether these relationships persist over time.

Third, some measures were adapted or developed by the program as part of the larger data collection effort. Although these measures demonstrated strong internal consistency, they have not been extensively validated across racially and ethnically diverse groups. Future studies should assess their construct validity and measurement invariance to ensure consistent interpretation across populations.

Additionally, reliance on self-report data may introduce biases related to social desirability or limited self-awareness. Incorporating perspectives from multiple informants, such as parents, teachers, or program staff, could provide a more comprehensive understanding of adolescents’ experiences and educational beliefs.

Finally, while critical thinking functioned as a protective factor in this study, other supportive processes, such as family, peer, or mentor support, may also buffer the negative effects of discrimination and foster college-going motivation. Future research should examine how these protective factors interact to promote resilience among adolescents navigating educational inequities.

6.5. Implications

These results have important implications for school mental health interventions and policies aimed at promoting resilience and positive outcomes among adolescents facing racial discrimination. Enhancing critical thinking skills through targeted interventions and fostering supportive environments that encourage critical reflection and cognitive empowerment may serve as effective strategies for buffering the harmful effects of in-school racial discrimination on adolescents’ educational aspirations (Zajda 2022). A review by Murphy et al. (2014) suggested that children can develop critical thinking by engaging them in discussions that encourage questioning and reasoning, providing opportunities for problem-solving and decision-making, and exposing them to diverse perspectives and viewpoints.

Yet, it is important to recognize that interventions designed to strengthen youth capacities should complement, not replace, broader institutional efforts to dismantle racism and inequity in schools. Fortifying adolescents with cognitive and socioemotional resources such as critical thinking can help them navigate a range of stressors—including, but not limited to, racial discrimination—but lasting progress requires systemic change that addresses the root causes of these inequities. Thus, critical thinking initiatives should occur in tandem with school and policy reforms that create more inclusive, equitable, and affirming educational environments.

Finally, the current findings also have implications for middle and high-school-aged youth who may experience psychological distress when confronted with racial discrimination in school, experiences which often instigate thoughts of self-doubt, depressive symptoms, and impaired executive functioning (Benner et al. 2018; Fernandez and Benner 2022; Ozier et al. 2019). These have undesirable implications for a young person’s pursuit of future goals, self-concept, and sense of self-efficacy. Critical thinking potentially disrupts those negative cognitions as an exercise of critical and reflective appraisal in which youth identify, assess, and incorporate information to make meaning of harmful experiences.

7. Conclusions

This study contributes to understanding how in-school racial discrimination, critical thinking, and future college-going beliefs intersect for adolescents from underrepresented backgrounds. Consistent with prior research, findings indicate that racial discrimination in school can erode students’ confidence in their ability to pursue higher education—particularly among those with lower critical thinking skills. At the same time, the results highlight the protective potential of strong critical thinking abilities, which appear to buffer against the harmful effects of discriminatory experiences on college-going beliefs. These insights reinforce the need to cultivate critical thinking not only within educational settings but also through family processes that prepare youth to navigate systemic barriers. Adults can foster these skills by encouraging open discussion, exploring multiple perspectives, and engaging adolescents in problem-solving about real-world issues, including discrimination. Such strategies, combined with supportive school and community environments, may help sustain college aspirations despite structural inequities. Future interventions and policies aimed at increasing college access for marginalized youth should integrate both school- and family-based approaches to equip adolescents with the cognitive and emotional tools necessary to maintain their educational goals in the face of adversity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.G. and D.R.H.; methodology, A.G.; writing—original draft preparation, A.G.; writing—review and editing, A.G., D.R.H., E.D.S.J. and J.M.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Rutgers University (protocol code Pro2024002469 and date of approval 8 April 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data are not publicly available due to confidentiality restrictions but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- AkbariLakeh, Maryam, Atefeh Naderi, and Azizollah Arbabisarjou. 2018. Critical thinking and emotional intelligence skills and relationship with students’ academic achievement. Prensa Medica Argentina 104: 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alderman, Elizabeth M., and Cora C. Breuner. 2019. Unique needs of the adolescent. Pediatrics 144: e20193150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychological Association. 2018. APA Dictionary of Psychology. Washington: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Azagba, Sunday, Galappaththige S. R. de Silva, and Todd Ebling. 2025. School climate and perceived discrimination: Associations with teen mental health. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, Meeta, Christy Byrd, and Stephanie Rowley. 2018. The relationship of school-based discrimination and ethnic-racial socialization to African American adolescents’ achievement outcomes. Social Sciences 7: 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baysu, Gulseli, Eva Grew, Jessie Hillekens, and Karen Phalet. 2024. Trajectories of ethnic discrimination and school adjustment of ethnically minoritized adolescents: The role of school diversity climate. Child Development 95: 2215–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beal, Sarah J., and Lisa J. Crockett. 2010. Adolescents’ occupational and educational aspirations and expectations: Links to high school activities and adult educational attainment. Developmental Psychology 46: 258–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benard, Bonnie. 1991. Fostering Resiliency in Kids: Protective Factors in the Family, School, and Community. Northwest Regional Educational Laboratory. National Dropout Prevention Center. Available online: https://dropoutprevention.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Benard_20091110.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Benner, Aprile D., and Sandra Graham. 2013. The antecedents and consequences of racial/ethnic discrimination during adolescence: Does the source of discrimination matter? Developmental Psychology 49: 1602–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benner, Aprile D., and Yijie Wang. 2014. Demographic marginalization, perceived discrimination, and adjustment among Mexican–American adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence 24: 622–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benner, Aprile D., Yishan Wang, Yishan Shen, Allison E. Boyle, Robert Polk, and Yixin Cheng. 2018. Racial/ethnic discrimination and well-being during adolescence: A meta-analytic review. American Psychologist 73: 855–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brissett, Daniela, Jacquelin Rankine, Lisa Mihaly, Romina Barral, Maria V. Svetaz, Alison Culyba, and Marissa Raymond-Flesch. 2025. Addressing Structural Violence in School Policies: A Call to Protect Children’s Safety and Well-Being. Journal of Adolescent Health 76: 752–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bronfenbrenner, Urie, and Pamela A. Morris. 2006. The bioecological model of human development. In Theoretical Models of Human Development: Vol. 1. Handbook of Child Psychology, 6th ed. Edited by Richard M. Lerner and William Damon. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, pp. 793–828. [Google Scholar]

- Bynum, Mia S., Candace Best, Sandra L. Barnes, and E. Thomoseo Burton. 2008. Private regard, identity protection, and perceived racism among African American males. Journal of African American Studies 12: 142–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavous, Tabbye M., Deborah Rivas-Drake, Ciara Smalls, Tiffany Griffin, and Courtney Cogburn. 2008. Gender matters, too: The influences of school racial discrimination and racial identity on academic engagement outcomes among African American adolescents. Developmental Psychology 44: 637–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Pan, and Alexander T. Vazsonyi. 2013. Future orientation, school contexts, and problem behaviors: A multilevel study. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 42: 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheon, Young-Mee, and Tiffany Yip. 2019. Longitudinal associations between racial/ethnic discrimination and ethnic identity processes in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 48: 1736–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cogburn, Cogburn D., Tabbye M. Chavous, and Tiffany Griffin. 2011. School-based racial and gender discrimination among African American adolescents: Exploring gender variation in frequency and implications for adjustment. Race and Social Problems 3: 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, Maureen, and Coshandra C. Dillard. 2019. Hate at School. Montgomery: Southern Poverty Law Center. [Google Scholar]

- DuBois, David, Carol Burk-Braxton, Lance Swenson, Heather Tevendale, and Jennifer Hardesty. 2002. Race and gender influences on adjustment in early adolescence: Investigation of an integrative model. Child Development 73: 1573–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, Jacquelynne S., and Allan Wigfield. 2020. From expectancy-value theory to situated expectancy-value theory: A developmental, social cognitive, and sociocultural perspective on motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology 61: 101859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facione, Peter A. 2020. Critical Thinking: What It Is and Why It Counts. Hayle: Insight Assessment. [Google Scholar]

- Felix, Erika D., and Sukkyung You. 2011. Peer victimization within the ethnic context of high school. Journal of Community Psychology 39: 860–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fergus, Stevenson, and Marc A. Zimmerman. 2005. Adolescent resilience: A framework for understanding healthy development in the face of risk. Annual Review of Public Health 26: 399–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, Celes, and Aprile D. Benner. 2022. Psychological resources as a buffer between racial/ethnic and SES-based discrimination and adolescents’ academic well-being. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 51: 599–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gale, Adrian. 2020. Examining Black adolescents’ perceptions of in-school racial discrimination: The role of teacher support on academic outcomes. Children and Youth Services Review 116: 105173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, Adrian. 2021. Examining the role of social support for adolescents from low socioeconomic backgrounds in a college access program. Adolescents 1: 391–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, Adrian, and Marquita Dorsey. 2020. Does the context of racial discrimination matter for adolescent school outcomes? The impact of in-school racial discrimination and general racial discrimination on Black adolescents’ outcomes. Race and Social Problems 12: 171–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galván, Adriana. 2019. The unrested adolescent brain. Child Development Perspectives 13: 141–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazivakili, Zohre, Nia R. Norouzi, Faride Panahi, Mehrdad Karimi, Hayede Gholsorkhi, and Zarrin Ahmadi. 2014. The role of critical thinking skills and learning styles of university students in their academic performance. Journal of Advances in Medical Education & Profes-sionalism 2: 95–102. [Google Scholar]

- Goldie, Peter D., Beverly Placide, and Sally L. Grapin. 2025. K-12 students’ perspectives on individual and systemic racism: A review of school psychology publications. Contemporary School Psychology 36: 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, Roberta. 2017. Risk and resilience theory: A social work perspective. In Human Behavior Theory and Social Work Practice. Edited by Francis J. Turner. London: Routledge, pp. 315–42. [Google Scholar]

- Hamm, Jill V., and Lei Zhang. 2010. School contexts and the development of adolescents’ peer relations. In Handbook of Research on Schools, Schooling, and Human Development. Edited by Judith L. Meece and Jacquelynne S. Eccles. London: Routledge, pp. 128–45. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, Andrew F. 2013. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heijltjes, Anique, Tamara Van Gog, Jimmie Leppink, and Fred Paas. 2014. Improving critical thinking: Effects of dispositions and instructions on transfer. Educational Research Review 11: 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Jun S., Jungtae Choi, Maha Albdour, Tamarie M. Willis, Jingu Kim, and Dexter R. Voisin. 2021. Future orientation and adverse outcomes of peer victimization among African American adolescents. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma 30: 528–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hope, Elan C., Alexandra B. Skoog, and Robert J. Jagers. 2015. It’ll never be the white kids, it’ll always be us’: Black high school students’ evolving critical analysis of racial discrimination and inequity in schools. Journal of Adolescent Research 30: 83–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, Diane, Jennifer Rodriguez, Evelyn P. Smith, Deborah J. Johnson, Howard C. Stevenson, and Paul Spicer. 2006. Parents’ ethnic-racial socialization practices: A review of research and directions for future study. Developmental Psychology 42: 747–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Jihyun, Brian Hand, and Brian F. French. 2023. Critical thinking skills and science achievement: A latent profile analysis. Thinking Skills and Creativity 49: 101349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Sarah R. L., Robert W. Blum, and Tina L. Cheng. 2014. Future orientation: A construct with implications for adolescent health and wellbeing. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health 26: 459–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerpelman, Jennifer L., Joe F. Pittman, Hans Saint-Eloi Cadely, Felicia J. Tuggle, Marinda K. Harrell-Levy, and Francesca M. Adler-Baeder. 2012. Identity and intimacy during adolescence: Connections among identity styles, romantic attachment, and identity commitment. Journal of Adolescence 35: 1427–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Sookyung, J. Heo, Hyeonkyeong Lee, and Kennedy D. Konlan. 2025. The recent trends in discrimination and health among ethnic minority adolescents: An integrative review. BMC Public Health 25: 21729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, Kelly Y. L. 2009. Assessing students’ critical thinking performance: Urging for measurements using multi-response format. Thinking Skills and Creativity 4: 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Emily R. 2011. Critical Thinking: A Literature Review. Edinburgh Gate: Pearson Research Report. Available online: http://paluchja-zajecia.home.amu.edu.pl/seminarium_fakult/sem_f_krytyczne/Critical%20Thinking%20A%20Literature%20Review.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- McKinnon, Izraelle I., Kathleen H. Krause, Nicolas A. Suarez, Tiffany M. Jones, Jorge V. Verlenden, Yolanda Cavalier, Alison L. Cammack, Christine L. Mattson, Rashid Njai, Jennifer Smith-Grant, and et al. 2024. Experiences of racism in school and associations with mental health, suicide risk, and substance use among high school students—Youth Risk Behavior Survey, United States. MMWR Supplements 73: 61–69. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/73/su/su7304a4.htm?utm (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Murphy, P. Karen, Meredith L. Rowe, Geetha Ramani, and Rebecca Silverman. 2014. Promoting critical-analytic thinking in children and adolescents at home and in school. Educational Psychology Review 26: 561–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neblett, Enrique W., Cheri L. Philip, Courtney D. Cogburn, and Robert M. Sellers. 2006. African American adolescents’ discrimination experiences and academic achievement: Racial socialization as a cultural compensatory and protective factor. Journal of Black Psychology 32: 199–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neblett, Enrique W., Jr., Deborah Rivas-Drake, and Adriana J. Umaña-Taylor. 2012. The promise of racial and ethnic protective factors in promoting ethnic minority youth development. Child Development Perspectives 6: 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nold, Herbert. 2017. Using critical thinking teaching methods to increase student success: An action research project. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education 29: 17–32. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1136016.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Nur’azizah, Rizqiyah, Budi Utami, and Budi Hastuti. 2021. The relationship between critical thinking skills and students’ learning motivation with students’ learning achievement about buffer solution in eleventh grade science program. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 1842: 012038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa, Melissa K., and Katie Constantin. 2023. Impacts of child sexual abuse: The mediating role of future orientation on academic outcomes. Child Abuse & Neglect 145: 106437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hara, Ross E., Frederick X. Gibbons, Chih-Yuan Weng, Meg Gerrard, and Ronald L. Simons. 2012. Perceived racial discrimination as a barrier to college enrollment for African Americans. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 38: 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozier, Elise, Valorie Taylor, and Mary Murphy. 2019. Cognitive effects of experiencing and observing subtle racial discrimination. Journal of Social Issues 75: 1087–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, David F., and Claudia C. Mincemoyer. 2002. Critical Thinking: Educational Material for the Life Skills Resources and Evaluation Program. University Park: The Pennsylvania State University. [Google Scholar]

- Phan, Huy P. 2010. Critical thinking as a self-regulatory process component in teaching and learning. Psicothema 22: 284–92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Seaton, Eleanor K., Enrique W. Neblett, Jr., Rachel D. Upton, Wizdom P. Hammond, and Robert M. Sellers. 2008. The moderating capacity of racial identity between perceived discrimination and psychological well-being over time among African American youth. Child Development 79: 403–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seginer, Rachel, ed. 2009. Future orientation: A conceptual framework. In Future Orientation: Developmental and Ecological Perspectives. Berlin: Springer, pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seginer, Rachel, and Sami Mahajna. 2018. Future orientation links perceived parenting and academic achievement: Gender differences among Muslim adolescents in Israel. Learning and Individual Differences 67: 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirazi, Fatemeh, and Shiva Heidari. 2019. The relationship between critical thinking skills and learning styles and academic achievement of nursing students. Journal of Nursing Research 27: e38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smalls, Ciara, R. White, Tabbye M. Chavous, and Robert M. Sellers. 2007. Racial ideological beliefs and racial discrimination experiences as predictors of academic engagement among African American adolescents. Journal of Black Psychology 33: 299–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, Suzanna, Dexter R. Voisin, Amanda Burnside, and Noni K. Gaylord-Harden. 2016. Future orientation and health related factors among African American adolescents. Children and Youth Services Review 61: 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, Suzanna, Noni K. Gaylord-Harden, Dexter R. Voisin, and Darrick Scott. 2018. Future orientation as a protective factor for African American adolescents exposed to community violence. Youth & Society 50: 734–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tummala-Narra, Pratyusha, and Michelle Claudius. 2013. Perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms among immigrant-origin adolescents: The role of ethnic identity and gender. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology 19: 257–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Ming-Te, and Jacquelynne S. Eccles. 2013. School Context, Achievement Motivation, and Academic Engagement: A Longitudinal Study of School Engagement Using a Multidimensional Perspective. Learning and Instruction 28: 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitbeck, B. Les, Xiaojin Chen, Dan R. Hoyt, and Gary W. Adams. 2004. Discrimination, historical loss and enculturation: Culturally specific risk and resilience factors for alcohol abuse among Native Americans. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 65: 409–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zajda, Joseph. 2022. Discourses of Globalization and Education Reforms: Overcoming Discrimination. Basel: Springer Nature. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, Marc A., Sarah A. Stoddard, Andria B. Eisman, Cleopatra H. Caldwell, Sophie M. Aiyer, and Alison Miller. 2013. Adolescent resilience: Promotive factors that inform prevention. Child Development Perspectives 7: 232–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.