Abstract

Urban bail systems rely heavily on cash bonds to secure the pretrial release of criminal defendants awaiting trial, despite longstanding criticism that this practice disproportionately incarcerates indigent defendants solely because they cannot afford to pay. Many large jurisdictions employ bail bond schedules that assign monetary amounts based primarily on the seriousness of the offense. Using data on 5322 defendants released on bail in 35 large urban counties, this study examines whether bail amount or a defendant’s prior criminal history better predicts pretrial failure, defined as pretrial rearrest and failure to appear. Results show that prior criminal history is a substantially stronger and more consistent predictor of pretrial failure than bail amount. Bail amount also exhibits no meaningful association with rearrest and only a modest relationship with failure to appear. These findings suggest that community safety may be better served by substantially reducing reliance on cash bail and placing greater emphasis on prior criminal history in pretrial release decisions.

1. Introduction

Urban bail systems rely heavily on cash bonds to secure the pretrial release of criminal defendants awaiting trial, despite longstanding criticism that this practice disproportionately incarcerates indigent defendants and exacerbates racial and economic inequality (Digard and Swavola 2019; Dobbie et al. 2018; Donnelly and MacDonald 2018). By conditioning release on a defendant’s ability to post a monetary bond, cash bail frequently results in wealth-based detention, confining individuals before conviction solely because they lack financial resources. In many large urban jurisdictions, bail amounts are set by bail bond schedules that assign fixed monetary amounts based primarily on the seriousness of the charged offense. As offense severity increases, so too does the prescribed bail amount. When defendants lack the financial means to post bail or are charged with more serious offenses, judges may modify bail at an initial court appearance. Nevertheless, monetary conditions of release remain the dominant mechanism governing pretrial liberty.

The reliance on cash bail has been widely criticized for producing racial and economic disparities in pretrial detention, constraining judicial discretion, undermining due process, and failing to improve public safety meaningfully (Digard and Swavola 2019; Dobbie et al. 2018; Donnelly and MacDonald 2018; Wylie and Grawert 2024). Because monetary bail conditions for release are based on a defendant’s financial resources rather than on empirically grounded risk indicators, individuals with limited economic means are disproportionately detained pretrial regardless of their likelihood of rearrest or failure to appear (FTA). As a result, cash bail often functions less as a risk-management tool than as a mechanism of wealth-based incarceration in large urban court systems.

Against this backdrop, a growing body of research calls into question the effectiveness of bail amount and offense seriousness as predictors of pretrial outcomes. Although bail schedules are premised on the assumption that higher bail amounts deter pretrial misconduct and enhance public safety, empirical evidence increasingly suggests that offense severity is a weak predictor of pretrial failure. In contrast, prior research indicates that a defendant’s prior criminal record is a far stronger and more consistent predictor of pretrial rearrest and court nonappearance than the amount of bail imposed (D’Alessio and Stolzenberg 2021).

Building on this literature, the present study evaluates the usefulness of a defendant’s prior criminal history in predicting pretrial failure, defined as pretrial rearrest and failure to appear, while accounting for bail amount, offense seriousness, and other legally relevant factors. Using data from the State Court Processing Statistics (SCPS) program, the analysis focuses on defendants released on bail in large urban counties, where reliance on monetary bail and bond schedules remains most entrenched. By directly comparing the predictive power of criminal history and bail amount, this study contributes to ongoing debates about the efficacy, fairness, and legitimacy of contemporary pretrial release practices.

The findings generated in this study speak to a central question in bail reform. Is community safety better served by financial conditions of release or by greater reliance on legally relevant, empirically grounded indicators of risk, particularly prior criminal record? Clarifying this issue is especially salient for large urban jurisdictions seeking to balance public safety, due process, and equity in pretrial decision-making.

2. Literature Review

On any given day, approximately 2.2 million individuals are incarcerated in the United States, with nearly 30% confined in local jails (Kaeble and Cowhig 2018). Notably, the majority of the jail population has not been convicted of a crime. An estimated 65% of the individuals confined in jail are being held pretrial (Davis 2022). This extensive reliance on pretrial detention is primarily attributable to the widespread use of cash bail and a corresponding decline in release on recognizance, in which defendants are released based solely on their promise to appear for scheduled court proceedings (Bechtel et al. 2012).

Cash bail refers to the conditional release of an arrested defendant secured by a monetary bond, intended to incentivize court appearance and deter new criminal activity during the pretrial period while allowing defendants to avoid punishment prior to conviction (Carroll 2020). In practice, however, monetary bail functions as a central institutional mechanism structuring pretrial release decisions, particularly in large urban jurisdictions, where high caseloads and administrative pressures encourage standardized decision-making.

A substantial body of research documents the adverse consequences of pretrial detention. Defendants detained prior to trial are more likely to plead guilty, face higher conviction rates, receive harsher sentences, and experience elevated post-disposition recidivism compared to similarly situated defendants who are released (Digard and Swavola 2019; Dobbie et al. 2018; Heaton et al. 2017; Leslie and Pope 2017; Stevenson 2018; Williams 2003). These outcomes are frequently attributed to the coercive conditions of jail confinement, including overcrowding, limited access to legal counsel and family support, and disruptions to employment, housing, and social stability (Lerman et al. 2022; Turney and Conner 2019; Wildeman et al. 2018). Although jail stays are typically shorter than prison sentences, pretrial jail confinement differs in important ways, as it involves greater uncertainty about release, fewer rehabilitative resources, and less procedural stability, which can intensify the disruptive effects of even brief periods of detention. While this literature is critical for understanding the downstream effects of detention, the present study is more directly concerned with how pretrial release decisions are structured and which legally relevant factors best predict pretrial outcomes among defendants who are released.

Accordingly, the discussion that follows focuses on the institutional mechanisms and decision inputs that shape pretrial decision-making in large jurisdictions, specifically bail bond schedules, commercial bail practices, offense seriousness, and prior criminal history.

2.1. Bail Bond Schedules and Commercial Bail

Many large U.S. jurisdictions rely on bail bond schedules to promote efficiency and uniformity in pretrial release decisions (Allen 2017). Approximately 64% of U.S. counties employ such schedules (Heaton et al. 2017). Bail schedules assign fixed monetary amounts to bailable offenses, facilitating rapid case processing without individualized judicial assessment. Proponents argue that these schedules promote consistency, reduce jail overcrowding, and conserve judicial resources in high-volume court systems. They are also defended as transparent mechanisms that limit overt discretion by ensuring defendants charged with similar offenses face comparable bail amounts.

Defendants unable to post full bail may secure release through commercial bail agents, who typically charge a nonrefundable premium, often 10% of the bail amount, and may require collateral or a cosigner (Cohen and Reaves 2007; Liu et al. 2018). However, even these reduced financial requirements remain prohibitive for many defendants. Estimates suggest that nearly 90% of defendants cannot afford bond premiums (Reaves 2013), rendering nominal eligibility for release functionally meaningless for a substantial portion of the pretrial population.

Recent scholarship further demonstrates that commercial bail practices produce racialized and gendered consequences that extend beyond formally accused defendants. Ethnographic and qualitative studies show that Black women are disproportionately burdened as cosigners or financial guarantors for detained family members (Deckard 2024; Page et al. 2019). Through these mechanisms, commercial bail extends carceral control into households and kinship networks, enrolling women, often women of color, into regimes of financial responsibility and surveillance despite not being the accused party. As a result, ostensibly neutral financial conditions of release can reproduce and intensify racial and gender inequalities.

2.2. Inequality, Discretion, and Legal Concerns

The burdens imposed by monetary bail are unevenly distributed across criminal defendants. A substantial body of research demonstrates that race and socioeconomic status substantially influence bail decisions and outcomes (Demuth 2003; Donnelly and MacDonald 2018; Freiburger et al. 2010; Monaghan et al. 2022; Williams 2016). Income disparities, particularly among Black men, further constrain access to the financial resources necessary to secure pretrial release. Using nationally representative labor-market data, Wilson and Darity (2022) found that Black–White wage gaps persist even after accounting for differences in education, experience, and occupational characteristics. They speculated that this situation reflected structural inequality rather than job mismatch. It is argued that monetary bail frequently functions less as a risk-management tool than as a mechanism of wealth-based detention, amplifying existing racial and economic inequalities in pretrial detention (Wooldredge et al. 2015).

Beyond concerns about affordability, bail bond schedules have been criticized for limiting judicial discretion and failing to account for individualized risk (Carlson 2011). Critics argue that fixed bail amounts may conflict with constitutional principles articulated in Stack v. Boyle (1951), which requires that bail be set according to standards relevant to ensuring court appearance. Because indigent defendants’ inability to pay results in detention, bail schedules have also been criticized on Due Process and Equal Protection grounds (Allen 2017; Heaton et al. 2017; Hurley 2016), despite their continued prevalence in large jurisdictions (Murtha 2024).

2.3. Offense Seriousness, Bail Amount, and Pretrial Risk

A further critique of bail bond schedules concerns their limited effectiveness in promoting public safety. Offense seriousness, the primary basis for determining bail amounts, is a relatively weak predictor of pretrial misconduct. In contrast, a growing body of empirical research identifies prior criminal history as a far stronger and more consistent predictor of both pretrial rearrest and failure to appear (Bechtel et al. 2011; Leslie and Pope 2017).

For example, using data from the State Court Processing Statistics program, D’Alessio and Stolzenberg (2021) examined whether higher bail amounts, based on offense seriousness, reduced pretrial rearrest among defendants released in Miami-Dade County. Analyzing more than 23,000 felony cases, they found that higher bail amounts were positively associated with rearrest, whereas prior criminal history was a substantially stronger predictor of pretrial misconduct. If monetary bail effectively enhances public safety, the amount of bail should be negatively associated with pretrial failure. Nevertheless, empirical evidence consistently fails to support this assumption.

Based on previous literature, there appears to be a persistent misalignment between the formal structure of pretrial decision-making and empirically grounded risk indicators. While bail schedules emphasize offense seriousness and monetary conditions, research consistently demonstrates that prior criminal history furnishes a more reliable indicator of pretrial risk. Emphasizing prior criminal history reflects a return to earlier generations of structured risk assessment that prioritized legally relevant indicators of risk, rather than relying on contemporary actuarial instruments that incorporate extralegal characteristics.

Contemporary critiques of pretrial risk assessment instruments (PRAs) further contextualize these findings. A substantial body of scholarship has raised concerns regarding PRAs. While PRAs typically consider a defendant’s criminal history, they also rely on extralegal and potentially subjective factors, such as employment status, housing stability, age, and family ties, that may reproduce structural inequalities under the guise of actuarial objectivity (Forrest 2021; Hannah-Moffat 2017; Starr 2014). The use of criminal history as a central indicator of pretrial risk does not represent a novel departure from prior practice but rather reflects a return to earlier generations of risk assessment that prioritized official criminal records over broader social characteristics. Second- and third-generation risk tools focused primarily on criminal history, with early pretrial instruments developed by the Vera Institute in the 1960s integrating criminal record information alongside limited stability factors (Taxman and Dezember 2017). At the same time, reliance solely on criminal history cannot eliminate prediction error. Even this approach must be understood as probabilistic rather than determinative, warranting continued caution in pretrial decision-making.

3. The Present Study

The present study builds on prior research by assessing the usefulness of a bailed defendant’s prior criminal record in explaining pretrial failure, defined as pretrial rearrest and failure to appear, while explicitly accounting for offense seriousness, bail amount, and other legally relevant factors. If prior criminal history is a stronger predictor of pretrial failure than offense severity or bail amount, it would suggest that community safety may be better enhanced by reducing reliance on monetary bail and placing greater emphasis on criminal history in pretrial release decisions.

It should be noted that emphasizing a defendant’s prior criminal record is not legally problematic because the state may legitimately consider factors relevant to flight risk and public safety. Criminal history is also readily accessible to judicial decision-makers, avoiding reliance on extralegal characteristics commonly embedded in pretrial risk assessment instruments. Although such instruments are gaining traction in guiding release decisions (Jannetta and Duane 2022), concerns persist regarding racial bias and the overprediction of pretrial failure (Chouldechova 2017; Moore 2022). Prior criminal history may therefore offer a more transparent, legally defensible, and empirically grounded foundation for pretrial decision-making in large urban jurisdictions.

4. Data and Methods

This study uses data from the 2009 State Court Processing Statistics (SCPS) program, administered by the Bureau of Justice Statistics (2014). The SCPS program provides nationally representative information on felony defendants prosecuted in the 75 most populous urban counties in the United States. SCPS employs a two-stage stratified sampling design in which felony cases filed during a single month are randomly selected within sampled counties and then followed for approximately one year. This design permits systematic examination of pretrial processing across jurisdictions while capturing key stages of case progression.

The dataset includes detailed measures of defendant demographics, offense characteristics, criminal history, bail and pretrial release decisions, and case outcomes, including failure to appear and pretrial rearrest (Bureau of Justice Statistics 2014). These features make SCPS particularly well-suited to evaluating the relationship among bail practices, criminal history, and pretrial outcomes in large urban jurisdictions.

The present analysis uses data from the most recent year (2009) of the State Court Processing Statistics (SCPS) program. The dataset includes 5974 felony defendants released on bail prior to trial in 35 of the 75 sampled large urban counties. Defendants released on bail constitute approximately 39% of all felony defendants processed in the sample, indicating a substantial subset of defendants subject to monetary bail decisions in large urban jurisdictions. These counties, listed in Appendix A, were included in this study because they consistently reported the information required to operationalize the key dependent and independent variables. The final analytic sample comprises 5322 defendants, reflecting listwise deletion of cases with missing values on any included variable in the multivariate regression models. Missing data were limited overall. Three control variables exhibited higher levels of missingness and were therefore modeled using missing-indicator variables to preserve sample size (Cohen and Cohen 1983). The missing data did not materially impact estimates of the focal independent variable. The data are publicly archived at the Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR) (Bureau of Justice Statistics 2014).

4.1. Dependent Variables

Pretrial failure is operationalized using two distinct but conceptually related outcomes: (1) pretrial rearrest and (2) pretrial failure to appear (FTA). These outcomes correspond directly to the dependent variables reported in Table 1 and Table 2 and capture the two primary forms of misconduct that pretrial release conditions are designed to prevent. These forms of misconduct include new criminal activity and failure to appear at required court proceedings during the pretrial period.

Table 1.

Description of variables used in the analysis.

Table 2.

Logistic regression results predicting pretrial rearrest and failure to appear.

Pretrial rearrest is measured as a dichotomous variable indicating whether a defendant was arrested for a new offense while released prior to adjudication of the original case. Defendants who were rearrested during the pretrial period are coded as 1, whereas those who were not rearrested are coded as 0.

Pretrial failure to appear is also measured as a dichotomous variable indicating whether a defendant failed to appear for at least one scheduled court appearance prior to case disposition. Defendants who missed any required court appearance during the pretrial period are coded as 1, while those who appeared as required are coded as 0.

Consistent with prior research, these outcomes are analyzed separately rather than combined into a single index of pretrial failure, as pretrial rearrest and failure to appear reflect distinct behavioral processes and may be influenced by different legal, social, and institutional mechanisms (Bechtel et al. 2011; Monaghan et al. 2022). Examining both outcomes independently also allows for a more nuanced assessment of pretrial risk by providing clearer insight into whether prior criminal history and bail amount differentially predict new criminal activity versus court noncompliance.

4.2. Independent Variables

The primary independent variable in the analysis is the defendant’s prior criminal record. The SCPS dataset includes multiple indicators of criminal history, including total prior arrests, prior felony arrests, prior misdemeanor arrests, total prior convictions, prior felony convictions, prior misdemeanor convictions, prior prison incarcerations, and prior jail incarcerations.

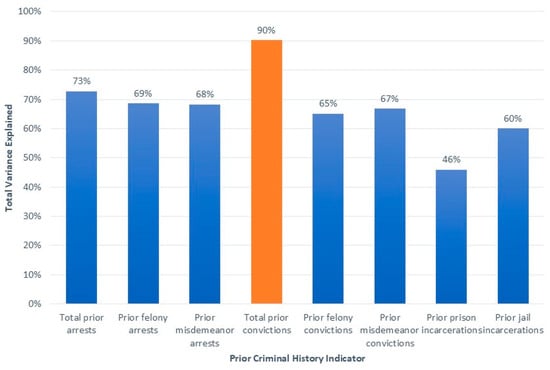

To identify the most empirically informative measure of criminal history and to avoid multicollinearity arising from the inclusion of highly correlated indicators, we conducted a principal component analysis (PCA). This approach enables a systematic assessment of shared variance among criminal history measures and facilitates a more parsimonious model specification. The results of the PCA, presented in Figure 1, indicate that the total number of prior convictions represents the dominant dimension of criminal history, accounting for approximately 90% of the total variance across the available indicators.

Figure 1.

Total variance explained by prior criminal history indicators in 35 U.S. counties (N = 5322).

Based on these results, and to enhance model interpretability while reducing redundancy and the risk of overfitting, we operationalize criminal history using the total number of prior convictions. This decision is consistent with prior research identifying convictions as a particularly salient indicator of cumulative criminal involvement and ensures that the estimated effect of criminal history is not obscured by overlapping or collinear measures.

The prior convictions variable ranges from 0 to 10 or more convictions, with higher values indicating a more extensive criminal record. This measure is treated as a continuous variable and is included in all multivariate models reported in Table 2.

In addition to the focal independent variable, the models include a comprehensive set of legally relevant control variables capturing offense seriousness, bail amount, number of arrest charges, criminal justice status at arrest, type of legal representation, time from arrest to release, and defendant demographic characteristics. For control variables with more than 10% missing data, corresponding missing-indicator variables were included to preserve sample size. This strategy, reflected in the regression specifications and table notes, helps ensure that the estimated association between prior criminal history and pretrial outcomes is not driven by systematic case attrition.

The seriousness of the defendant’s original offense is associated with the likelihood of pretrial rearrest (Bechtel et al. 2011; Williams 2003) and is therefore explicitly controlled in the analysis. Rather than relying on a single ordinal severity scale, offense seriousness is operationalized using dummy-coded offense categories, thereby allowing the models to account for systematic differences in risk across offense types. This approach provides a flexible and transparent means of controlling for offense seriousness without imposing arbitrary assumptions about the relative severity of offenses.

Consistent with the classification scheme reported in Table 1 and employed in the multivariate models, offenses are grouped into five mutually exclusive categories: violent, serious property, minor property, drug, and public-order offenses. Public-order offenses serve as the reference category in all regression analyses, such that the coefficients for the remaining offense categories capture differences in pretrial rearrest risk relative to lower-severity public-order charges.

Prior research has also examined the relationship between bail amount and pretrial outcomes, with evidence suggesting that higher bail amounts are associated with increased, rather than reduced, pretrial rearrest rates (D’Alessio and Stolzenberg 2021; Monaghan et al. 2022). The number of arrest charges is included as an additional control, as defendants facing multiple charges may be perceived as posing a greater risk and may therefore be subject to heightened surveillance or enforcement, increasing the likelihood of rearrest (Tartaro and Sedelmaier 2009). Similarly, defendants who are under active criminal justice supervision at the time of arrest, such as probation, parole, or other custodial or supervisory statuses, exhibit higher rates of pretrial recidivism than those without such statuses (Cohen and Reaves 2007), reflecting both elevated baseline risk and increased system monitoring.

The models also control for the type of legal representation, as whether a court-appointed attorney or private counsel represents a defendant serves as a proxy for socioeconomic status, which is correlated with criminal justice involvement (Imran et al. 2018). In addition, time from arrest to release is included to account for variation in exposure to pretrial detention, which prior research has shown can exacerbate subsequent criminal behavior and increase the likelihood of rearrest even after release (Dobbie et al. 2018; Heaton et al. 2017; Leslie and Pope 2017).

Finally, demographic characteristics are included as control variables because prior research consistently demonstrates their association with recidivism patterns. Specifically, age (Rakes et al. 2018), race (McGovern et al. 2009), gender (Collins 2010), and Hispanic ethnicity (McGovern et al. 2009) have each been shown to correlate with reoffending outcomes. Including these variables reduces the risk of omitted-variable bias and ensures that the estimated relationship between prior criminal history and pretrial failure is not spurious due to correlated demographic factors.

4.3. Analytical Strategy

We employed logistic regression in SPSS Version 25 (IBM 2017) to examine whether a released defendant’s prior criminal history affects the likelihood of pretrial failure, defined as pretrial rearrest and failure to appear. Logistic regression is appropriate given the binary nature of the dependent variables and allows for the inclusion of both continuous and categorical predictors.

The bail amount and the number of days from arrest to release exhibited substantial positive skewness. These variables were natural-log transformed, with a constant added to the latter variable to accommodate same-day releases. All multivariate regression models include county fixed effects to account for unobserved jurisdictional heterogeneity across the sampled urban counties. Variance inflation factor (VIF) diagnostics indicated no evidence of problematic multicollinearity among the independent variables. Statistical significance was assessed using two-tailed tests at the alpha level of 0.05.

5. Descriptive Analysis Results

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for the variables included in the logistic regression analyses. The final analytical sample consists of 5322 felony defendants released prior to trial in 35 large urban counties. Among these defendants, 14% were rearrested during the pretrial period, and 14% failed to appear (FTA) for at least one scheduled court appearance prior to case disposition.

Regarding criminal history, defendants averaged 2.28 prior convictions (SD = 3.17). Values ranged from 0 to 10 or more convictions, indicating substantial heterogeneity in prior criminal involvement. The mean bail amount was $22,077 (SD = $58,473), reflecting extreme dispersion, with amounts ranging from $10 to approximately $2.5 million. Defendants faced an average of 2.32 arrest charges (SD = 2.64), with charges ranging from 1 to 72.

The demographic characteristics of the sample indicate that approximately 81% of defendants were male, with a mean age at arrest of 31.27 years (SD = 10.90; range = 15–83). Slightly more than half of the defendants (52%) were identified as Black, and 19% as Hispanic. Approximately 57% of the defendants were represented by a court-appointed attorney, consistent with the socioeconomic profile of pretrial defendants in large urban jurisdictions.

Additional variables capture defendants’ legal status and exposure to pretrial detention. Approximately 20% of defendants were under active criminal justice supervision at the time of arrest, such as probation, parole, or other custodial or supervisory conditions. The mean number of days from arrest to release was 13.60 (SD = 33.45), with a maximum of 667 days, indicating substantial variation in pretrial processing time. Table 1 also reports offense categories, with drug offenses (33%) and violent offenses (23%) constituting the most common charge types, followed by minor property (18%), public-order (16%), and serious property (10%) offenses.

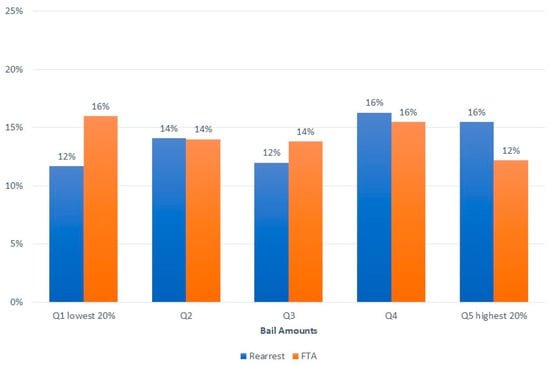

Figure 2 depicts the bivariate relationship between bail amount and both measures of pretrial failure, pretrial rearrest and failure to appear, using unadjusted proportions calculated within bail-amount categories. Across the bail categories shown, rates of rearrest and failure to appear vary only modestly, indicating little bivariate association between bail amount and either outcome. This descriptive pattern suggests that higher bail amounts do not meaningfully reduce the likelihood of pretrial misconduct among defendants released prior to trial.

Figure 2.

Pretrial rearrest and failure to appear rates by bail amounts in 35 U.S. counties (N = 5322).

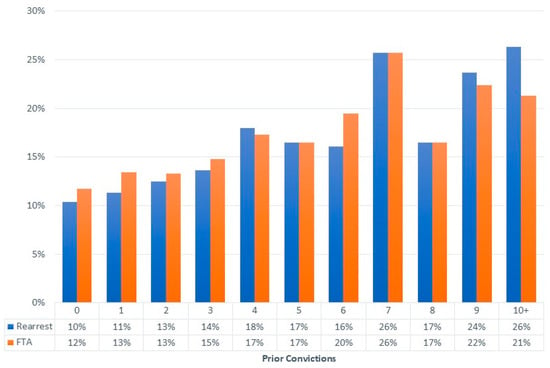

In contrast, Figure 3 shows a strong, monotonic relationship between prior convictions and both measures of pretrial failure. As the number of prior convictions increases, the proportions of defendants who are rearrested or fail to appear during the pretrial period rise sharply. Defendants with more extensive criminal histories experience substantially higher rates of both forms of pretrial failure, underscoring the central role of cumulative criminal history in predicting pretrial misconduct.

Figure 3.

Pretrial rearrest and failure to appear rates by prior convictions in 35 U.S. counties (N = 5322).

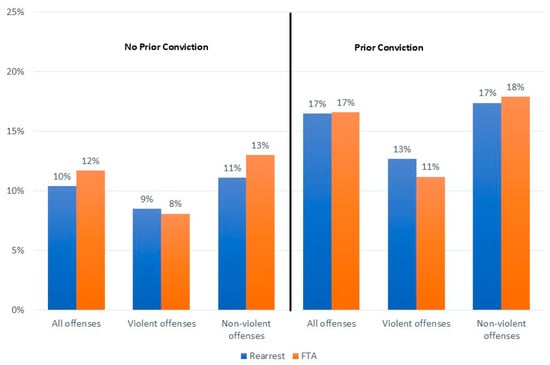

Figure 4 further examines rates of pretrial failure by prior conviction status and offense type. Across all offense categories, defendants with prior convictions exhibit higher rates of both rearrest and failure to appear than defendants without prior convictions. This disparity is particularly pronounced for nonviolent offenses, where the gap in pretrial failure between defendants with and without prior convictions is largest. Even among defendants charged with violent offenses, prior convictions are associated with substantially elevated rates of pretrial failure.

Figure 4.

Pretrial rearrest and failure to appear rates by offense type and prior conviction in 35 U.S. counties (N = 5322).

Finally, Figure 5 presents rates of pretrial failure by the most serious arrest charge. Rates of these outcomes vary across offense types, with drug-related and property offenses exhibiting the highest levels of pretrial failure. Notably, the figure suggests a negative bivariate relationship between offense seriousness and pretrial failure, such that defendants charged with more serious offenses appear less likely to be rearrested or fail to appear while released pretrial. This descriptive pattern challenges the assumption that offense severity alone provides a reliable proxy for pretrial risk.

Figure 5.

Pretrial rearrest and failure to appear rates by most serious arrest charge in 35 U.S. counties (N = 5322).

The descriptive patterns displayed in Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5 motivate the multivariate logistic regression analyses that follow. These analyses formally assess whether prior criminal history predicts pretrial rearrest and failure to appear net of bail amount, offense type, and other legally relevant control variables.

6. Logistic Regression Results

Table 2 reports the results of the logistic regression analyses predicting pretrial rearrest and failure to appear (FTA) among defendants released prior to trial. Because both the bail amount and the time from arrest to release exhibit substantial positive skewness, these variables are entered into the models in natural-log form. The time-to-release variable was adjusted by adding +1 prior to transformation because a substantial proportion of defendants were released on the same day as arrest (coded as 0), and the natural logarithm of zero is undefined. Variance inflation factors (VIFs) were examined to assess multicollinearity among the independent variables, and the diagnostics indicated no evidence of problematic multicollinearity.

Consistent with the descriptive analyses, prior criminal history emerges as the strongest and most consistent predictor of both forms of pretrial failure. Each additional prior conviction increases the odds of pretrial rearrest by approximately 11% and the odds of failure to appear by approximately 6%, net of all other covariates. In contrast, bail amount (logged) is not significantly associated with pretrial rearrest. However, bail amount is negatively and significantly associated with FTA, indicating that higher bail amounts are modestly associated with a reduced likelihood of failing to appear in court.

The number of arrest charges is positively associated with pretrial rearrest, though the magnitude of this effect is small and not statistically significant for FTA. Defendants under active criminal justice supervision at the time of arrest, such as probation, parole, or other custodial or supervisory statuses, have much higher odds of both pretrial rearrest and failure to appear than defendants without such statuses.

The type of legal representation also plays a noteworthy role in pretrial outcomes. Defendants represented by a court-appointed attorney exhibit significantly higher odds of both rearrest and failure to appear relative to those represented by private counsel. In addition, defendants with missing information on attorney type show substantially elevated odds of FTA, suggesting systematic differences between cases with complete and incomplete representation data.

Several demographic characteristics are appreciably associated with pretrial outcomes. Male defendants have higher odds of pretrial rearrest, though gender is not significantly related to failure to appear. Age at arrest has an inverse effect on both outcomes, indicating that older defendants are less apt to be rearrested or fail to appear during the pretrial period. In contrast, race and Hispanic ethnicity are not markedly associated with either pretrial rearrest or FTA once legally relevant factors and criminal history are taken into account.

The logged time from arrest to release has a positive and statistically significant effect on both pretrial rearrest and failure to appear, indicating that longer periods of pretrial detention prior to release are associated with an increased risk of subsequent pretrial failure. Missing-indicator variables for time to release do not exert independent effects on either outcome.

Offense seriousness is controlled using dummy-coded offense categories, with public-order offenses serving as the reference group. Compared with public-order offenses, serious property offenses are associated with higher odds of pretrial rearrest. In contrast, violent offenses are associated with lower odds of both rearrest and failure to appear. Most offense-category coefficients, however, are not statistically significant. Such a finding reflects substantial heterogeneity across offense types and indicates that offense seriousness accounts for considerably less variation in pretrial failure than prior criminal history.

Overall, the models explain a modest but meaningful proportion of variance in pretrial outcomes, with Nagelkerke R2 values of 0.131 for rearrest and 0.143 for failure to appear. Such levels of model fit are consistent with prior research on pretrial outcomes and reflect the inherent difficulty of predicting relatively low-base-rate events such as pretrial failure. Although a substantial share of pretrial failure remains unexplained, the results consistently show that prior criminal history outperforms both bail amount and offense severity as a predictor of pretrial outcomes among defendants released in large urban counties.

7. Discussion and Conclusions

Bail reform has been a central issue in U.S. criminal justice policy for nearly six decades, beginning with the Bail Reform Act of 1966 and continuing through contemporary reform efforts. Because the State Court Processing Statistics data analyzed in this study are drawn exclusively from large urban counties, the findings should be interpreted as most applicable to highly populated jurisdictions rather than generalized to the entire criminal justice system. Within these urban contexts, the 1966 Act marked a significant shift in pretrial policy by encouraging release on recognizance for noncapital defendants and reducing reliance on financial conditions. Its core objective was to minimize unnecessary pretrial detention by emphasizing flight risk rather than a defendant’s ability to pay. Despite this reform-oriented intent, subsequent decades witnessed a renewed and expanded reliance on monetary bail, particularly through the widespread adoption of bail bond schedules, effectively reintroducing wealth as a primary determinant of pretrial liberty in many large jurisdictions.

Pretrial release decisions inherently involve balancing public safety concerns against the fundamental principle that individuals are presumed innocent and should not be punished prior to conviction. Persistent concerns remain about the fairness and effectiveness of monetary bail systems, particularly given their disproportionate impact on indigent defendants awaiting trial. Because conditions for release hinge primarily on a defendant’s ability to post a monetary surety, individuals with limited financial resources are frequently detained pretrial regardless of their actual risk of misconduct. Empirical evidence from urban jurisdictions indicates that a substantial proportion of arrested individuals are detained pretrial due solely to an inability to afford bail, with these burdens falling disproportionately on people of color.

Critics further argue that the routine use of monetary bail in large jurisdictions constrains judicial discretion and fails to align pretrial release decisions with empirically grounded risk indicators in a meaningful way. Nevertheless, despite sustained legal and empirical critiques, many urban jurisdictions continue to rely heavily on bail bond schedules to determine monetary conditions of release.

The results generated in this study present a consistent, policy-relevant story within the context of large urban counties. Across both descriptive and multivariate analyses, a defendant’s prior criminal record emerges as a substantially stronger predictor of pretrial failure than bail amount. Prior convictions are strongly and consistently associated with both pretrial rearrest and failure to appear. Findings also show that bail amount is not correlated with rearrest and is only modestly linked with court appearance. These findings challenge the premise that increasing bail amounts enhances public safety and call into question the effectiveness of monetary bail as a primary mechanism for managing pretrial risk.

It is important to recognize that implementing a pretrial release framework that places greater emphasis on a defendant’s prior criminal history is neither legally problematic nor administratively burdensome. Criminal history constitutes a legally relevant factor directly tied to assessments of public safety and flight risk and is readily accessible to judicial decision-makers. By contrast, many contemporary risk assessment instruments incorporate extralegal characteristics, such as age, gender, employment status, or residential stability, that raise normative and constitutional concerns. Although such factors may demonstrate statistical predictive value, they do not constitute criminal conduct, and reliance on self-reported information further undermines transparency and legitimacy in pretrial decision-making.

The strong and consistent association between prior criminal record and pretrial rearrest observed in this study is theoretically consistent with labeling theory (Becker 1963; Matsueda 1992) and related perspectives on cumulative disadvantage and reintegrative shaming (Braithwaite 1989). From this perspective, formal criminal labeling can trigger processes of secondary deviance by restricting access to legitimate social and economic opportunities, increasing exposure to criminal justice surveillance, and reinforcing stigmatized identities. These mechanisms may increase the likelihood that an individual will remain in contact with the criminal justice system, including pretrial rearrest.

In sum, our findings suggest that meaningful bail reform in large urban jurisdictions should focus on decreasing reliance on monetary bail while strengthening the use of legally relevant, empirically supported criteria, particularly prior criminal history, in pretrial release decisions. Such an approach would mitigate wealth-based detention, improve fairness and transparency, and better align pretrial practices with actual risk. This can also be accomplished without defaulting to expanded pretrial incarceration.

7.1. Study Limitations

While the findings presented here contribute to the literature on bail and pretrial decision-making in large urban jurisdictions, several limitations warrant consideration. A primary concern is the use of rearrest to measure pretrial failure. Although rearrest is commonly employed as an indicator of new criminal activity during the pretrial period, it reflects official police action rather than confirmed offending behavior. Rearrest may thus partially capture enforcement practices as well as actual criminal conduct.

Prior research demonstrates that individuals with a criminal record are substantially more likely to be arrested than similarly situated individuals without a record, even after controlling for case-specific and situational factors. For example, Stolzenberg et al. (2021) found that suspects with prior criminal records were dramatically more likely to be arrested than those without such records, a pattern they attribute in part to the stigmatizing effect of prior criminal labeling on police decision-making. Consequently, some defendants classified as having failed pretrial in the present study due to rearrest may have been arrested not because of more substantial evidence of wrongdoing, but because their prior records heightened police suspicion or scrutiny. This limitation is particularly salient given that prior criminal history is the focal explanatory variable in the analysis and may therefore amplify the observed association between criminal record and rearrest.

A related limitation is that the analysis does not account for the temporal distance between a defendant’s prior convictions and the current arrest. Prior criminal history is treated cumulatively, without distinguishing between recent and distant convictions. Research on desistance and redemption suggests that the predictive value of criminal history declines substantially as time since the last offense increases. For instance, Kurlychek et al. (2006) found that individuals who had remained offense-free for six to seven years exhibited reoffending rates comparable to those with no prior criminal record. Similarly, Blumstein and Nakamura (2009) documented a decline in rearrest risk over time, consistent with life-course perspectives emphasizing aging, social integration, and diminishing criminogenic propensity. Failure to account for the time from the last conviction may therefore overstate the risk posed by individuals whose prior offenses occurred many years earlier.

Finally, although this study includes failure to appear as a second measure of pretrial failure, limitations remain in entirely disentangling the distinct mechanisms underlying rearrest and court nonappearance. While both outcomes are legally relevant, they may be driven by different behavioral, structural, and institutional factors. Future research would benefit from more refined measures of pretrial misconduct, such as post-release convictions or adjudicated violations, thereby reducing reliance on arrest-based indicators and providing a more direct assessment of offending behavior.

Taken together, these limitations suggest that the findings should be interpreted with appropriate caution. Although prior criminal history emerges as a strong predictor of pretrial outcomes, part of this relationship, specifically for rearrest, may reflect differential surveillance and enforcement rather than criminal behavior alone. Addressing these limitations in future research would further clarify the role of criminal history in pretrial decision-making and strengthen the empirical foundation for bail reform policy.

7.2. Future Research

Several avenues for future research emerge from this study’s findings. A critical extension involves examining the temporal dimension of prior criminal history. Although the present analysis demonstrates that the cumulative number of prior convictions is a strong predictor of pretrial failure, it does not distinguish between recent and distant convictions. A substantial body of research indicates that the risk of reoffending declines markedly with increasing time since the last offense, consistent with redemption, desistance, and life-course perspectives (Blumstein and Nakamura 2009; Kurlychek et al. 2006). Future studies should therefore incorporate measures of time since last conviction to determine whether the predictive power of criminal history diminishes with prolonged offense-free periods and whether pretrial risk assessments can more accurately distinguish persistent from desisting offenders.

A second area warranting further investigation concerns the measurement of pretrial failure. While rearrest is a commonly used and policy-relevant indicator, it reflects official police action rather than confirmed criminal behavior. Prior research demonstrates that individuals with criminal records are disproportionately likely to be arrested independent of actual offending, raising concerns about enforcement bias and differential surveillance (Stolzenberg et al. 2021). Future research would benefit from incorporating alternative outcome measures, such as post-release convictions, adjudicated violations, or combined indicators that distinguish between arrest and conviction, to provide a more direct assessment of criminal behavior during the pretrial period and to better isolate behavioral risk from enforcement practices.

Finally, future research should more directly examine the institutional and contextual factors that shape pretrial decision-making across jurisdictions. Although this study focuses on large urban counties, meaningful variation likely exists in how bail schedules are implemented, how discretion is exercised, and how pretrial supervision is structured. Comparative analyses that account for jurisdictional practices, court culture, prosecutorial norms, and local reform environments would help clarify whether the relationships observed here generalize across legal contexts and whether reforms emphasizing legally relevant criteria can be implemented consistently and equitably at scale.

In sum, these extensions would refine the measurement of pretrial risk, strengthen causal inference, and improve the policy relevance of future research on bail reform and pretrial decision-making.

7.3. Policy Implications

The findings from this study have important implications for bail reform policy in large urban jurisdictions. First, lessening the routine reliance on monetary bail would directly address the inequities it creates for indigent defendants, who are disproportionately detained pretrial due to an inability to post financial bond. The results presented here indicate that bail amount is not meaningfully associated with pretrial rearrest and is only modestly associated with failure to appear, calling into question the use of financial resources as a primary mechanism for promoting public safety or managing pretrial risk.

Importantly, reducing reliance on monetary bail does not imply that individuals deemed to pose a higher risk should be categorically detained pretrial. Such an approach would risk expanding pretrial incarceration and undermining the presumption of innocence. Rather, the findings support constraining the use of financial conditions of release while preserving judicial discretion and maintaining a range of noncustodial release options grounded in legally relevant criteria.

Second, the evidence suggests that a defendant’s prior criminal record should play a central role in pretrial release decisions. Criminal history is legally relevant and empirically robust in predicting pretrial rearrest and failure to appear. It also offers a clear and administratively feasible basis for judicial decision-making. Pretrial policies that stress prior criminal record rather than monetary surety, while continuing to allow release under appropriate nonfinancial conditions, would likely improve fairness and efficiency and better align release decisions with actual risk.

Third, these findings raise concerns about the growing reliance on pretrial risk assessment instruments that incorporate extralegal factors such as employment status or housing stability. Although such factors may demonstrate statistical predictive value, they lack clear legal relevance and risk reproducing structural inequalities in the pretrial process. Grounding release decisions in factors that are both legally legitimate and empirically supported, like prior criminal history, would enhance transparency, consistency, and institutional legitimacy without defaulting to increased detention.

Taken in their totality, our results suggest that meaningful bail reform in large urban jurisdictions should focus on limiting the use of monetary bail to circumstances in which it serves a clear and justified purpose, while expanding pretrial practices that rely on legally relevant, empirically grounded criteria and noncustodial release options. Such an approach would help mitigate the disproportionate harm associated with cash bail while promoting fairness, efficiency, and public safety in pretrial decision-making.

7.4. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that monetary bail has no substantive impact on pretrial rearrest, whereas a defendant’s prior criminal record is a far stronger and more consistent predictor of pretrial failure. Reliance on cash bail disproportionately penalizes indigent defendants and people of color while failing to enhance public safety or meaningfully reduce pretrial misconduct. By contrast, emphasizing legally relevant factors, particularly prior criminal history, offers a more transparent, equitable, and empirically grounded approach to pretrial decision-making.

A pretrial system that minimizes financial conditions of release and prioritizes legally legitimate indicators of risk would reduce wealth-based detention, improve procedural fairness, and better align pretrial practices with the goals of community safety and due process. Within large urban jurisdictions, where bail schedules and monetary conditions remain deeply entrenched, these findings underscore the need for reform strategies that move beyond cash bail and toward evidence-based, legally defensible pretrial policies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.C. and S.J.D.; methodology, L.S.; software, L.S.; validation, E.C., S.J.D. and L.S.; formal analysis, L.S.; investigation, E.C.; resources, E.C.; data curation, L.S.; writing—original draft preparation, E.C.; writing—review and editing, S.J.D.; visualization, L.S.; supervision, S.J.D.; project administration, L.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study are publicly available from the Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR), State Court Processing Statistics, 1990–2009: Felony Defendants in Large Urban Counties (ICPSR 2038). https://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR02038.v5.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

U.S. counties included in the analytical sample (N = 35).

Table A1.

U.S. counties included in the analytical sample (N = 35).

| Baltimore (County), Maryland | Middlesex, New Jersey |

| Broward, Florida | Milwaukee, Wisconsin |

| Cook, Illinois | Montgomery, Maryland |

| Cuyahoga, Ohio | Oakland, Michigan |

| Dallas, Texas | Orange, California |

| El Paso, Texas | Orange, Florida |

| Essex, New Jersey | Pima, Arizona |

| Fairfax, Virginia | Prince George, Maryland |

| Franklin, Ohio | Salt Lake, Utah |

| Hamilton, Ohio | San Bernardino, California |

| Hartford, Connecticut | Shelby, Tennessee |

| Harris, Texas | St Louis, Missouri |

| Hillsborough, Florida | Suffolk, New York |

| Honolulu, Hawaii | Tarrant, Texas |

| King, Washington | Ventura, California |

| Los Angeles, California | Wake, North Carolina |

| Maricopa, Arizona | Wayne, Michigan |

| Marion, Indiana |

References

- Allen, Joshua A. 2017. Making bail: Limiting the use of bail schedules and defining the elusive meaning of excessive bail. Journal of Law & Policy 25: 637–86. [Google Scholar]

- Bechtel, Kristen, Christopher T. Lowenkamp, and Alexander Holsinger. 2011. Identifying the predictors of pretrial failure: A meta-analysis. Federal Probation 75: 78–87. [Google Scholar]

- Bechtel, Kristen, John Clark, Matthew R. Jones, and Douglas J. Levin. 2012. Dispelling the Myths: What Policymakers Need to Know About Pretrial Research. Baltimore: Pretrial Justice Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, Howard S. 1963. Outsiders: Studies in the Sociology of Deviance. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Blumstein, Alfred, and Kiminori Nakamura. 2009. Redemption in the presence of widespread criminal background checks. Criminology 47: 327–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braithwaite, John. 1989. Crime, Shame and Reintegration. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bureau of Justice Statistics. 2014. State Court Processing Statistics, 1990–2009: Felony Defendants in Large Urban Counties (ICPSR 2038) [Data Set]; Ann Arbor: Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research. [CrossRef]

- Carlson, Lindsey. 2011. Determining bail: A study of bail bond schedules. Criminal Justice Policy Review 22: 438–63. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, John E. 2020. The due process of bail. Wake Forest Law Review 55: 757–92. [Google Scholar]

- Chouldechova, Alexandra. 2017. Fair prediction with disparate impact: A study of bias in recidivism prediction instruments. Big Data 5: 153–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Jacob, and Patricia Cohen. 1983. Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Thomas H., and Brian A. Reaves. 2007. Pretrial Release of Felony Defendants in State Courts: State Court Processing Statistics, 1990–2004. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, Renee E. 2010. The effect of gender on violent and nonviolent recidivism: A meta-analysis. Journal of Criminal Justice 38: 675–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Alessio, Stewart J., and Lisa Stolzenberg. 2021. Higher Money Bail Doesn’t Lead to Greater Public Safety. The Crime Report (July 15). New York: The Center on Media, Crime, and Justice at John Jay College. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, Daniel. 2022. Care of justice-involved populations. Missouri Medicine 119: 208–12. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Deckard, Faith M. 2024. Surveilling sureties: How privately mediated monetary sanctions enroll and responsibilize families. Social Problems 72: 1651–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demuth, Stephen. 2003. Racial and ethnic differences in pretrial release decisions and outcomes: A comparison of Hispanic, Black, and White felony arrestees. Criminology 41: 873–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Digard, Leon, and Elizabeth Swavola. 2019. Justice Denied: The Harmful and Lasting Effects of Pretrial Detention. New York: Vera Institute of Justice. [Google Scholar]

- Dobbie, Will, Jacob Goldin, and Crystal S. Yang. 2018. The effects of pretrial detention on conviction, future crime, and employment: Evidence from randomly assigned judges. American Economic Review 108: 201–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, Elizabeth A., and John. M. MacDonald. 2018. The downstream effects of bail and pretrial detention on racial disparities in incarceration. Journal of Criminal Law & Criminology 108: 775–814. [Google Scholar]

- Forrest, Kelly B. 2021. When Machines Can Be Judge, Jury, and Executioner: Justice in the Age of Artificial Intelligence. Singapore: World Scientific. [Google Scholar]

- Freiburger, Tina L., Cheryl D. Marcum, and Matthew Pierce. 2010. The impact of race on the pretrial decision. American Journal of Criminal Justice 35: 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannah-Moffat, Kelly. 2017. Purpose and context matters: Creating a space for meaningful dialogues about risk and need. In Handbook on Risk and Need Assessment: Theory and Practice. Edited by Faye S. Taxman. London: Routledge, pp. 431–46. [Google Scholar]

- Heaton, Paul, Sandra Mayson, and Megan Stevenson. 2017. The downstream consequences of misdemeanor pretrial detention. Stanford Law Review 69: 711–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurley, Gregory. 2016. The Constitutionality of Bond Schedules. Williamsburg: National Center for State Courts. [Google Scholar]

- IBM. 2017. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0. Armonk: IBM. [Google Scholar]

- Imran, Mohammad, Mohammad Hosen, and Mohammad A. F. Chowdhury. 2018. Does poverty lead to crime? Evidence from the United States of America. International Journal of Social Economics 45: 1424–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jannetta, Jesse, and Megan Duane. 2022. Risk Assessment and Structured Decisionmaking for Pretrial Release. Washington, DC: Urban Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Kaeble, Danielle, and Mary Cowhig. 2018. Correctional Populations in the United States, 2016. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Kurlychek, Megan C., Robert Brame, and Shawn D. Bushway. 2006. Scarlet letters and recidivism: Does an old criminal record predict future offending? Criminology & Public Policy 5: 483–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerman, Amy E., Alice L. Green, and Patricio Dominguez. 2022. Pleading for justice: Bullpen therapy, pretrial detention, and plea bargains in American courts. Crime & Delinquency 68: 159–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leslie, Emily, and Nicolas G. Pope. 2017. The unintended impact of pretrial detention on case outcomes: Evidence from New York City arraignments. The Journal of Law and Economics 60: 529–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Patrick, Ryan Nunn, and Jay Shambaugh. 2018. The Economics of Bail and Pretrial Detention. Washington, DC: The Hamilton Project. [Google Scholar]

- Matsueda, Ross L. 1992. Reflected appraisals, parental labeling, and delinquency: Specifying a symbolic interactionist theory. American Journal of Sociology 97: 1577–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGovern, Virginia, Stephen Demuth, and James E. Jacoby. 2009. Racial and ethnic recidivism risks: A comparison of post-incarceration rearrest, reconviction, and reincarceration among White, Black, and Hispanic releasees. The Prison Journal 89: 309–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monaghan, Jennifer, van E. J. Holm, and Christopher W. Surprenant. 2022. Get jailed, jump bail? The impacts of cash bail on failure to appear and re-arrest in Orleans Parish. American Journal of Criminal Justice 47: 56–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, Katherine. 2022. Pretrial Justice Without Money Bail or Risk Assessments. New York: Thurgood Marshall Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Murtha, Michael. 2024. Warning: Civil rights in California may vary by county due to unconstitutional bail schedules. University of the Pacific Law Review 55: 313–41. [Google Scholar]

- Page, Joshua, Victoria Piehowski, and Joe Soss. 2019. A debt of care: Commercial bail and the gendered logic of criminal justice predation. RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences 5: 150–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakes, Sarah, Stephanie G. Prost, and Susan J. Tripodi. 2018. Recidivism among older adults: Correlates of prison re-entry. Justice Policy Journal 15: 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Reaves, Brian A. 2013. Felony Defendants in Large Urban Counties, 2009. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Stack v. Boyle, 342 U.S. 1. 1951. Available online: https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/342/1/ (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Starr, Sonja B. 2014. Evidence-based sentencing and the scientific rationalization of discrimination. Stanford Law Review 66: 803–72. [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson, Megan T. 2018. Distortion of justice: How the inability to pay bail affects case outcomes. The Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization 34: 511–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolzenberg, Lisa, Stewart J. D’Alessio, and Jamie L. Flexon. 2021. The usual suspects: Prior criminal record and the probability of arrest. Police Quarterly 24: 31–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tartaro, Christine, and Christopher M. Sedelmaier. 2009. A tale of two counties: The impact of pretrial release, race, and ethnicity upon sentencing decisions. Criminal Justice Studies 22: 203–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taxman, Faye S., and Ashley Dezember. 2017. The value and importance of risk and need assessment (RNA) in corrections and sentencing: An overview of the handbook. In Handbook on Risk and Need Assessment: Theory and Practice. Edited by Faye S. Taxman. London: Routledge, pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Turney, Kristin, and Elizabeth Conner. 2019. Jail incarceration: A common and consequential form of criminal justice contact. Annual Review of Criminology 2: 265–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wildeman, Christopher, Megan D. Fitzpatrick, and Alexander W. Goldman. 2018. Conditions of confinement in American prisons and jails. Annual Review of Law and Social Science 14: 29–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, Marvin R. 2003. The effect of pretrial detention on imprisonment decisions. Criminal Justice Review 28: 299–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, Marvin R. 2016. From bail to jail: The effect of jail capacity on bail decisions. American Journal of Criminal Justice 41: 484–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, Valerie, and William Darity, Jr. 2022. Understanding Black-White Disparities in Labor Market Outcomes Requires Models That Account for Persistent Discrimination and Unequal Bargaining Power. Washington, DC: Economic Policy Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Wooldredge, John, James Frank, Nicole Goulette, and L. Edward Travis, III. 2015. Is the impact of cumulative disadvantage on sentencing greater for Black defendants? Criminology & Public Policy 14: 187–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wylie, Sean, and Adrian Grawert. 2024. Challenges to Advancing Bail Reform: Lessons from Five States. New York: Brennan Center for Justice. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.