3.1. Gender Expression

Cosplay creates a safe space for gender expression to challenge traditional gender norms. In Japan, society expects women to be gentle and nurturing. They are expected to be soft-spoken, polite, and non-confrontational, maintaining harmony in social settings. The society also wants them to take care of the family. In many anime series, female characters often prepare box lunches for their loved ones. They are expected to avoid much self-expression. Men should be strong and reliable. The society expects them to develop leadership and decision-making ability. They are brave and aggressive. They should avoid feminine expressions (

Kincaid 2013). However, cosplayers serve to restore the image of characters rather than defining femininity and masculinity. They used crossplay to break the traditional gender narrative. Crossplay refers to cosplayers playing roles that are opposite to their biological sex. At the same time, the cosplayers’ performances should align with the original character images. If the bodies of two sexes can achieve the same effect for characters of the same sex, there are no specific gender norms for one gender (

Hutabarat-Nelson 2017). For example, a cosplayer utilized crossplay to challenge traditional gender norms. In

Figure 2, this cosplayer is male. He played a female character in Date a Live, called Tokisaki Kurumi. He played the classic character of Kurumi. She is a slender and petite girl. The black dress decorated with roses looks dignified and elegant. However, she is renowned for the image of killing and creating fear. Her weapon is a pistol, which is used to consume others’ lifespans and replenish her own. Elegance and aggressiveness that belong to two gender expectations appear in the same female character. He effectively captures this tension, showing how male cosplayers can embody both gentleness and boldness of female characters. Men possess decisive and aggressive traits.

Therefore, it is very suitable for a male cosplayer to play such a bellicose female character. His performance breaks the limitations of traditional gender norms and gender expectations. His performance demonstrated that women are not vulnerable and dependent; they can also be powerful and capable of protecting themselves. His eyes and demeanor reveal a resolute image of a combative state. However, he hopes that his makeup can be more feminine to showcase Kurumi’s temperament. He asked the makeup artist to make the lines of his face more delicate and applied bright lipstick. These changes in makeup all enabled him to present a feminine side in his performance, which made his portrayal more in line with Kurumi’s temperament.

His cosplay reflects Erving Goffman’s notion of gender. Erving Goffman claims that gender is doing rather than being. “Being” means the biological sex of the cosplayer is innate and fixed. “Doing” refers to the gender roles that people perform and behave in daily interactions (

Goffman 1959). This male cosplayer displayed the gentle face and elegant posture of the female character by imitating Kurumi’s costume and makeup. However, his crossplay is contrary to the theory advocated by Goffman. Role-playing is the act of people performing roles in life that meet the social expectations of both men and women. Society is a stage, and people play roles like actors (

Goffman 1959). People in Japan often perform expected gender roles to conform to traditional gender norms, but he conceals his well-defined and angular face, which has strong masculine features. Despite being a man, he played a female role that met social expectations. It is a breakthrough of social norms for a male cosplayer to portray an elegant female character. His performance enabled the audience to redefine female identity and feminine traits. The nature of the character reproduced in role-playing balances the doubts and abruptness that his breakthrough might bring. The audience will believe he is playing a character, while considering whether traditional gender norms are the only criteria for constructing the social gender order. Cosplay has become a buffer zone for reconstructing society’s expectations of gender. The breakthrough of cosplayers is based on the degree of character restoration, which protects them from attacks by advocates of traditional gender norms. More importantly, the audience’s cognition has reduced the constraints and limitations of gender norms.

Moreover, cosplayers break the stereotypes of gender expression and enrich the diversity of gender expression. Specifically, cosplayers use crossplay to expand the diversity of gender expression and embrace diverse traits of a gender instead of confining gender expression to a fixed interpretation. Crossplay has nothing to do with their gender identities (

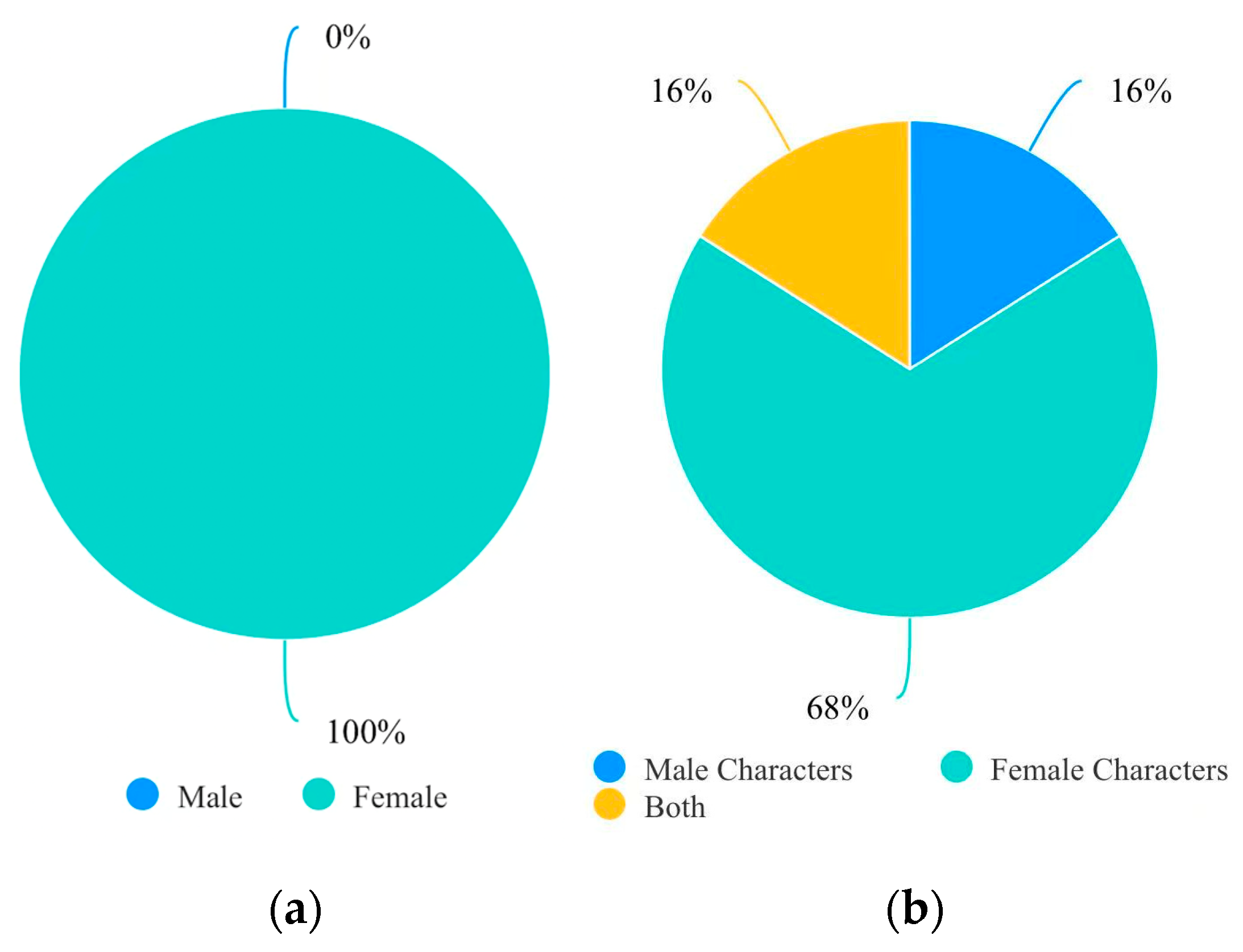

Glasspool 2023). At the ICOS International Comic Con in August 2025, the researcher randomly selected 25 cosplayers to fill out the questionnaire. They are all women, as shown in

Figure 3. However, 16 percent of the participants were good at playing male characters. 16 percent of the participants were proficient in both male and female characters. They show their proficiency and professionalism in crossplay. Female cosplayers often choose androgynous characters or bishōnen to play when selecting male characters, not bellicose and muscular ones. Bishōnen means beautiful youth (

Glasspool 2023). In

Figure 4, a female cosplayer played the male chess player. This chess player is a graceful chess player. He is good at playing chess and providing political strategies. She chose the classic chess player’s outfit. She wore a blue shawl and a robe with plum blossom patterns at the comic convention, presenting the character as ethereal and aloof. The plum blossom also symbolizes the indomitable and noble male character. She thinks she has a neutral appearance and a pair of well-defined masculine brows and eyes exuding aloof grace. Therefore, she believes that playing male roles makes her feel more at ease and more comfortable. Her androgynous appearance and elegant temperament enable her to be more compatible with the character image of “beautiful youth”, which provides her with an opportunity to expand the diversity of gender expression. Men can also be refined and debonair, not necessarily rugged and burly. Her temperament is in line with this role. Her crossplay reduces the stereotype of male images and broadens diverse gender expressions. This image differs from the traditional portrayal of strong male characters shaped by gender norms, but it aligns with her temperament. While finding roles that align with their self-images, they are also breaking gender stereotypes and expanding the diversity of gender expression. Another representative way of gender expression is that cosplayers tend to play cute figures. Kawaii stands for cuteness and innocence. This image is inconsistent with the traditional Japanese stereotype of aggressive and virile male characters (

Glasspool 2023). Many cosplayers play cute male characters according to their preference for characters. These cosplayers reduce the restrictions on gender temperament. The words that previously described female characters can also be used to describe male characters. On cosplay platforms, audiences and other cosplayers consider that they are playing characters and praise the degree of accuracy in restoring anime characters. Audiences don’t question them when cosplayers do not meet audiences’ expectations for the appearance or temperament of men or women. The audience will think their images align with the characters and are derived from the anime. They don’t make designs beyond their characters’ images.

It is more acceptable to express the gender identities of the cosplayers in cosplay. “Trans” cosplay not only expresses cosplayers’ affection for their characters, but also reflects their gender identities. They reveal their true gender to society by playing characters that match their gender identities (

Glasspool 2023). If the characters they present are aligned with the appearances of the characters, the audience will consider that they are playing the characters. Therefore, audiences are more likely to accept cosplayers’ appearance in an image that is different from their biological sex. Their expression of gender identities is harmonious with the image of their characters. A female cosplayer said that her favorite character was Rick Grimes, a male character from The Walking Dead. She indicated that when playing this character, she was able to express herself more freely without being constrained by gender issues in her daily life (

Tompkins 2019). This way naturally expresses her masculinity and gender identity. Her performance vividly portrays the character’s image and respects the character’s temperament. Audiences consider her to be a debonair male figure. When the audience recognizes the masculinity in her, society is more likely to accept her true gender identity. Cosplay serves as a safe channel, making cosplayers feel confident in expressing their gender, which aligns with the definition of cosplay as “playing another role”.

3.2. Mental Health

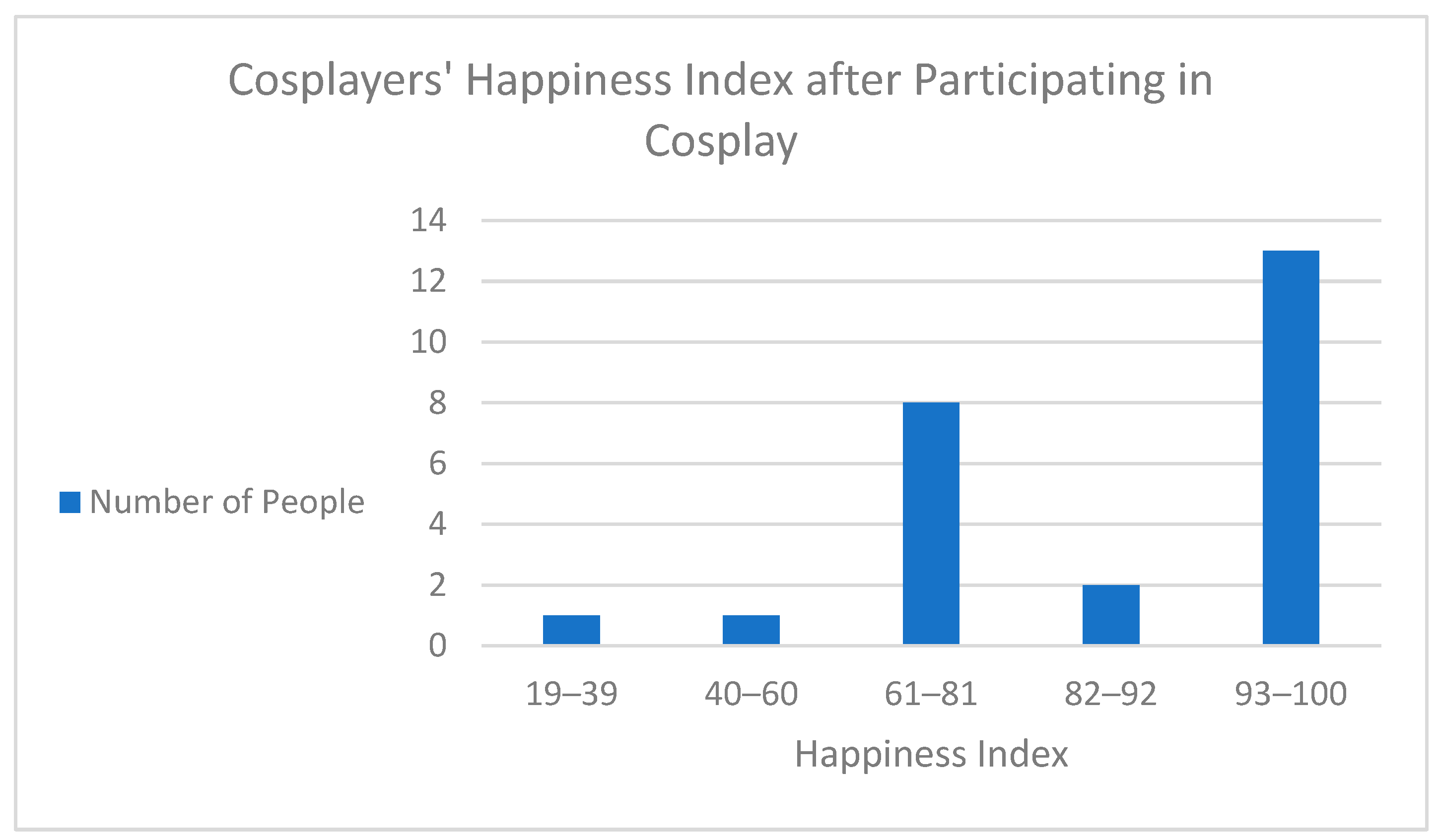

Cosplay helps cosplayers overcome mental pressure in reality through role play. By alleviating mental pressure, cosplay enhances the sense of happiness of cosplayers. In

Figure 5, 92 percent of the participants had a happiness index above 60, among the 25 participants. More than half of the participants had a happiness index between 93 and 100, which demonstrates that cosplay has a positive effect on the mental health of cosplayers. The high happiness indexes after participating in cosplay indicate that cosplay is an effective tool for improving the mental health of cosplayers. The positive impact of cosplay helps improve mental health in Japan. In Japan, a special phenomenon is called jōhatsu.

Jōhatsu refers to individuals in Japan who intentionally vanish from their lives to escape work stress, social pressure, family difficulties, debt, or shame (

Hincks 2017). Shame is associated with feelings of resignation, unemployment, failing exams, and not meeting the expectations of various age groups. Shame culture is pervasive in Japan (

Rooksby et al. 2023). People are highly sensitive to others’ opinions and criticisms. Jōhatsu is usually manifested through depression, social anxiety disorder, and adjustment disorder (

Hincks 2017). Cosplay provides a space for people who have these mental pressures in real life to release and overcome them. Psychological counselors often apply the immersive tendency to help customers relieve stress. Immersive tendency refers to the state where people become entirely immersed in the characters they play and the virtual world. This process of “devoting oneself to the character” allows people to temporarily set aside anxiety, troubles, and self-doubts in real life (

Morris Chambers 2023). Customers develop cognitive resonances with these characters and their stories, which help them get into the characters. This treatment approach is not the way to evade problems but rather to learn the courage to overcome stress from the characters and build the resilience to recover from difficulties. Resilience refers to the capacity to adapt well and recover after experiencing significant stress, adversity, or trauma. Rather than being unaffected, resilient individuals may experience emotional pain. However, they can gradually regain mental calm, solve problems positively and effectively, and seek solutions that help them move forward (

American Psychological Association n.d.). This approach can help the authentic self-emerge from trauma by playing the role of a virtual character.

Furthermore, psychological counselors combine this method with superhero therapy. The characters they choose to play are usually heroic figures in anime. Superheroes all have a common superpower, which is the ability to heal. Most of the current storylines of superheroes are about facing setbacks, quickly recovering from frustration, actively solving problems, and defeating villains (

Rubin 2006). After cosplayers overcome the difficulties faced by the characters they play, they are motivated by this heroic spirit and learn the spirit of overcoming difficulties. In real life, they emulate superheroes’ healing behaviors to save themselves and develop resilience, which alleviates their work and social pressures. The characters they play serve as their role models to guide them to move forward. When they perform other characters and experience their stories, they will imitate the behaviors and personalities of their ideal roles. This phenomenon is called the Proteus Effect (

Yee 2007). This concept goes back to the key point in cosplay: imitation. Playing another character can often enhance the bravery and problem-solving abilities of cosplayers. They consider that they are doing everything in the image of another character rather than themselves. The sense of shame in them would have vanished accordingly. Even if they make mistakes, they will believe it’s the characters’ fault. The characters bear the shame and pressure for them. In addition, by healing the traumas faced by the characters, they are also healing themselves. Cosplayers understand that characters also experience embarrassing emotions after facing shameful events. They understand that this is an instinctive emotional response shared by most people, so they can consider it a normal process, and their emotions can be understandable. Thus, they apply these methods to solve problems and regulate their negative emotions in real life.

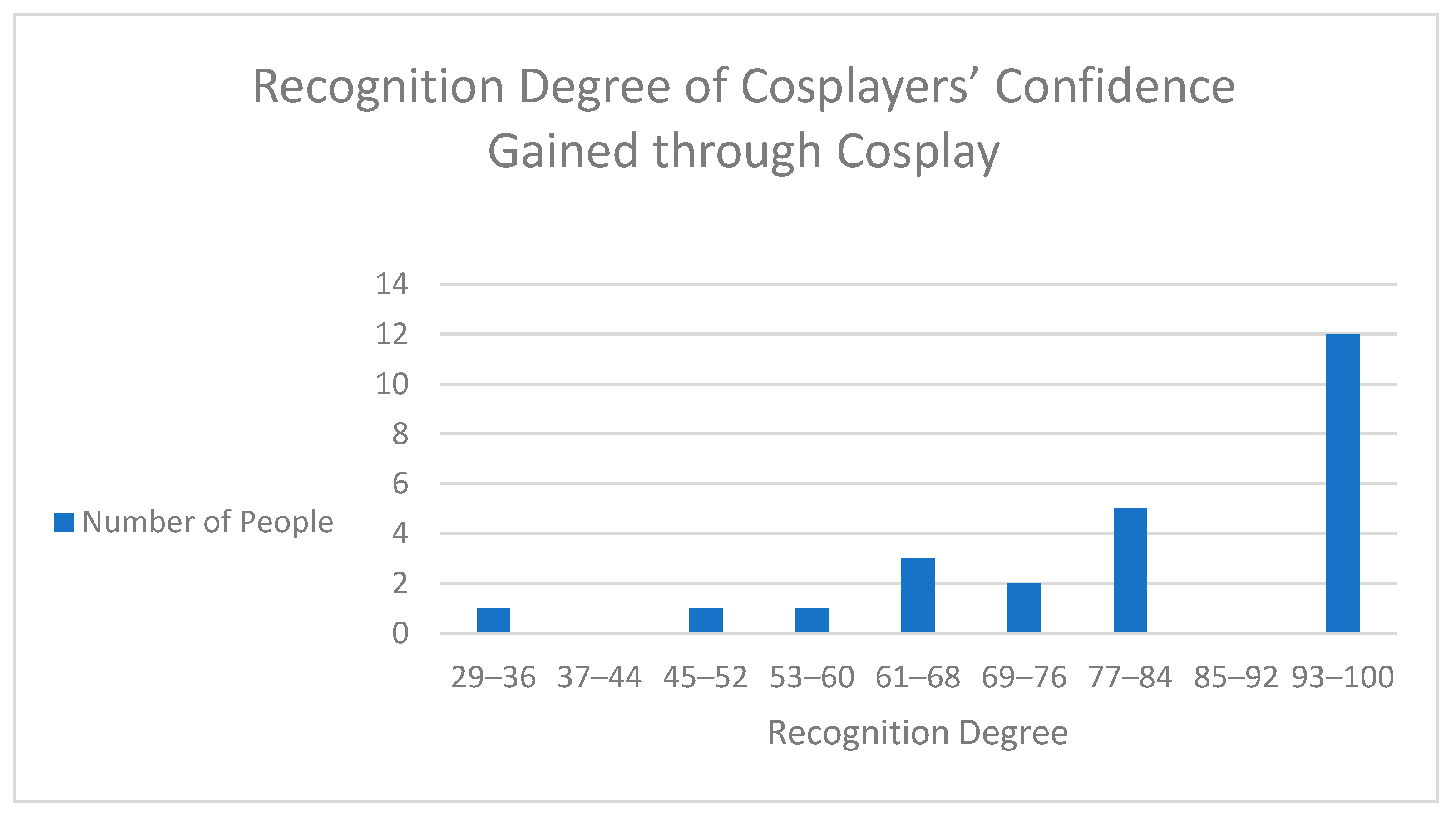

Cosplayers regulate their emotions and gain a sense of achievement by mastering skills through the creation of costumes. Both anxiety and depression in Japan are severe. The reason for the immense pressure is that they haven’t found something that can be mastered and accomplished independently. They have been trapped in a sad mood that renders them feel worthless and unable to shake this mood off. Cosplay focuses more on handcrafting. Many cosplayers designed their costumes. Handmade production requires investments of time and energy. When they complete the whole costume, they will gain a sense of achievement and pride. Even if this is only a small part of it, they independently accomplished them rather than relying on others, which is very important for those who tend to criticize and deny themselves in their daily lives. They affirm themselves and build confidence by making cosplay costumes. In

Figure 6, 88 percent of participants expressed an approval rate of over 60 for gaining more confidence through cosplay among 25 participants. Nearly half of the participants were within the range of 93 to 100 in terms of their recognition degree of gaining confidence. The sense of achievement gained from completing the costumes and wearing them at comic conventions helped them build confidence. This sense of accomplishment enhances the motivation for such pleasant activities. They feel confident about their ability and believe their efforts are worthwhile. In Yorath’s research, a cosplayer emphasized that she thought the costume she made looked bad, but she did create something. Without her dedication, this costume would not exist (

Yorath 2022).

Cosplayers gained confidence and developed problem-solving skills by making costumes. Taking cosplayer Gyaku as an example, he experienced a sense of control and accomplishment through crafting the Faraam costume from Dark Souls II. The materials of the samurai’s helmet and armor are hard to find and too expensive. Gyaku looked for substitutes immediately. He chose handcrafted fiberboard as a substitute, which could be found in small shops. He used a hot melt gun to connect the components of the armor. He drew the patterns required for the vest on the selected fabric, cut it, and colored it by himself. The color balance of blue and yellow needs to be evaluated by Gyaku himself. The entire armor took a week to complete. Gyaku obtained a suit of armor and wore it to the comic convention (

Gyaku 2017). These investments and dedication to cosplay come with material rewards and promote his growth. He independently handled and decided the entire process, from material selection to accessory assembly and coloring. He felt a great sense of achievement and gained the confidence to solve problems. He also received recognition from audiences. In the video’s comment section, viewers expressed their admiration for his ability to produce a complete suit of armor of exceptional quality. They were impressed by how accurately the design and texture of the armor were replicated. These comments boosted his confidence. Therefore, the confidence gained from both internal and external perspectives is a positive indication of mental health. He receives recognition from himself and others simultaneously. He affirms his value and ability. Additionally, the process of making costumes inspires cosplayers to learn new skills. They can apply their creative skills and problem-solving abilities to their lives (

Yorath 2022). Gyaku enjoys the process of making costumes and takes the initiative to solve the problems. Upon discovering that the helmet materials were difficult to obtain, he quickly identified fiberboard as a suitable alternative and replicated the appearance of the armor by applying gray paint. By reducing or solving the things that make him feel anxious or stressed, his mental health naturally improves. As he has experienced the process of solving problems in cosplay, he can apply this problem-solving ability to the predicaments in daily life. Therefore, cosplayers like Gyaku will realize that their costumes are under their control and choice. They can decide how to solve the problems. The reason why they feel stressed in daily life is that others determine their fate, and cosplayers make choices passively. In cosplay, they can independently and actively make character costumes.

Adolescents participating in cosplay need to have a clear and comprehensive understanding of their personal identity, which helps protect their mental health during the transition to adulthood and avoid identity confusion. Most participants in cosplay activities are adolescents, and some are even minors. For young people, the most significant intrinsic motivation to participate in cosplay is the desire to explore self-expression and personal development. Another major intrinsic motivation is the pursuit of a sense of belonging and opportunities to interact with peers within the cosplay community (

Abramova et al. 2021). According to Erikson’s psychosocial stages of development, late adolescence is a critical period for clarifying “who they are” and forming a stable perception of their identities (

Cherry 2024). Both self-expression and group belonging function as practices through which adolescents explore and construct their personal identities. These motivations engage both internal self-perception and external social feedback, reflecting the dual components of identity formation. A clear identity allows adolescents to better understand their strengths, cultural and gender identities, reducing the likelihood of identity confusion in adulthood. Once teenagers develop a stable sense of self, they also recognize that the characters they portray in cosplay represent only one dimension of their personality—often a side that is not expressed in everyday life. When teenagers have a clear understanding of their identities, they will be able to distinguish between the roles they play and their true selves. After participating in conventions, they can comfortably transition out of their character roles without becoming overly attached to their virtual identities or resisting a return to real life. Understanding that their real selves differ from their portrayals enables young cosplayers to form a solid and deep understanding of their gender expression, mental health, and cultural consumption. As a result, they become better equipped to manage and minimize potential negative psychological impacts and identity confusion in cosplay.

3.3. Cultural Consumption

Cosplayers use their characters as cultural consumption to promote the economic industrial chain of cosplay in Japan. Cultural consumption is the process by which individuals or groups select, engage with, and interpret cultural products. Cosplayers both make and purchase costumes of characters. When creating costumes, they consider which materials are more suitable for showcasing the texture of the clothes and the temperament of the characters in the anime. When cosplayers purchase costumes, they will compare different merchants. They also spend several hours practicing the characters’ signature expressions and manners. Their costumes and performance should be as close as possible to the designs of the original characters (

Hutabarat-Nelson 2017). They engage with and reflect on cosplay characters, which is a kind of cultural reinterpretation and reuse. During this process, a large amount of consumption emerges. A great deal of time and energy has been invested in the cultural consumption of cosplay. Cosplayers have devoted a significant amount of time to selecting costumes, producing them, and replicating character movements. Such a large time cost will weaken the stickiness of cosplayers to the cosplay hobby. Recreational activities should be carried out during periods when both the mind and body are not disturbed by work and family (

Seregina and Weijo 2016). Some cosplayers who cannot afford the high prices of costumes will make their own. Their joy in making clothes can be affected by the tight schedule and exhaustion. As life changes, with more time spent on work and family, the time spent on cosplay will inevitably decrease. Some cosplayers sometimes forget to eat because they are overly devoted to costume making (

Seregina and Weijo 2016). The researchers stayed at the comic convention until the end of the program. Most of the cosplayers didn’t go to eat until the program was about to end. Maintaining the character image for a long time in the venue is also a hard and challenging process, which consumes a lot of their physical strength and energy. Therefore, while cosplayers enjoy the cultural consumption of cosplay, they expend considerable energy. Such consumption of time and energy will reduce the consumption stickiness of some cosplayers towards cosplay. If cosplayers want to maintain high stickiness, they should learn to plan reasonably the time for preparing for comic conventions and the learning efficiency of character features.

In addition to investing a great deal of time and energy, Cosplayers spend a lot of money on purchasing costumes. Yano Research Institute estimates the market size of cosplay costumes in Japan for 2024 to be approximately

$1.87 billion. It increased by

$0.32 billion within four years (

Okazaki 2025). Most cosplayers purchase costumes that cost between

$101 and

$200. In pursuit of higher-quality costumes, some cosplayers spend between

$200 and

$600 on each piece. Movie-quality costumes up to

$2000 (

Astute Analytica 2023) (Pune, India). The market size indicates that there is a significant expenditure on cosplay costumes. The following special characteristics of cosplay explain the high prices of the costumes. First, most of the characters’ costumes are handmade. Unlike mass-produced costumes from wholesale factories, handmade costumes require significant time and effort, which results in much higher prices. A piece of costume may take several weeks or even months to make. They need to cut, polish, and sew the fabric according to the pattern of the clothing (

La 2019). These steps require a huge amount of working time and investment costs. In addition, the costumes for cosplay are usually multi-layered. Artisans need to make the linings, corsets, cloaks, and accessories on the arms of the costumes (

Joice 2021). They need to ensure that the materials they choose can meticulously depict the characters’ images in the anime. Different levels of costumes need to be superimposed to form a complete set of costumes that can fit the appearance of a character. The absence of one of these layers affects the appearance and restoration degree of the costumes. Artisans consider many design concepts in the process of making costumes. Rather than paying for the costumes, it is more about paying for the superb skills and dedication of the artisans. Some cosplayers choose to make their costumes to save money, but this option incurs additional expenses. Some cosplayers tried a type of costume that they had never made before. They may make mistakes in material selection and pattern cutting during the production process, which causes them to have to purchase new materials (

Joice 2021). This process of making costumes generates additional costs. Therefore, cosplayers’ purchase and production of costumes generate a large amount of consumption, which promotes Japan’s economic benefits. Moreover, because there are many anime and comics in Japan, each cosplayer prefers different characters. The costumes of the characters are very rare. Some less popular character costumes and props may only be available in two or three. Thus, this rarity can also lead to high prices of costumes. Besides, cosplayers often play multiple characters to attend various comic conventions, so they need to buy different costumes to update their characters. Another reason for frequently updating characters is to remain active in the cosplay community and on social media, which helps to expand their social influence. Beyond the costume itself, related accessories, wigs, and props will also incur expenses (

Suhaeb et al. 2021). They actively consume cosplay in this process. Cosplayers who want to engage with the cosplay culture need to either handcraft or purchase their costumes. They are both creators and consumers. Such dual roles not only bring considerable consumption, but also form a sustainable consumption cycle. A continuous stream of cosplayers joins this consumption cycle based on their demands. Different anime and manga are frequently screened in Japan. New characters also appear in a released anime series. Cosplayers want to play the latest and most popular characters, so they have demands for the new costumes of these characters. As long as there is demand, there will be supply. Some cosplayers also have strong handicraft skills. These cosplayers and custom-made sellers make and sell costumes. Other cosplayers purchase these costumes. This circular cultural consumption has enabled cosplay to be continuously consumed and produced, remaining active in the market. Anime, as a mainstream culture, provides new materials for cosplayers, which promotes the sustainable development of cosplay as a subculture. Therefore, participating in the cosplay culture has brought continuous economic benefits to Japan.

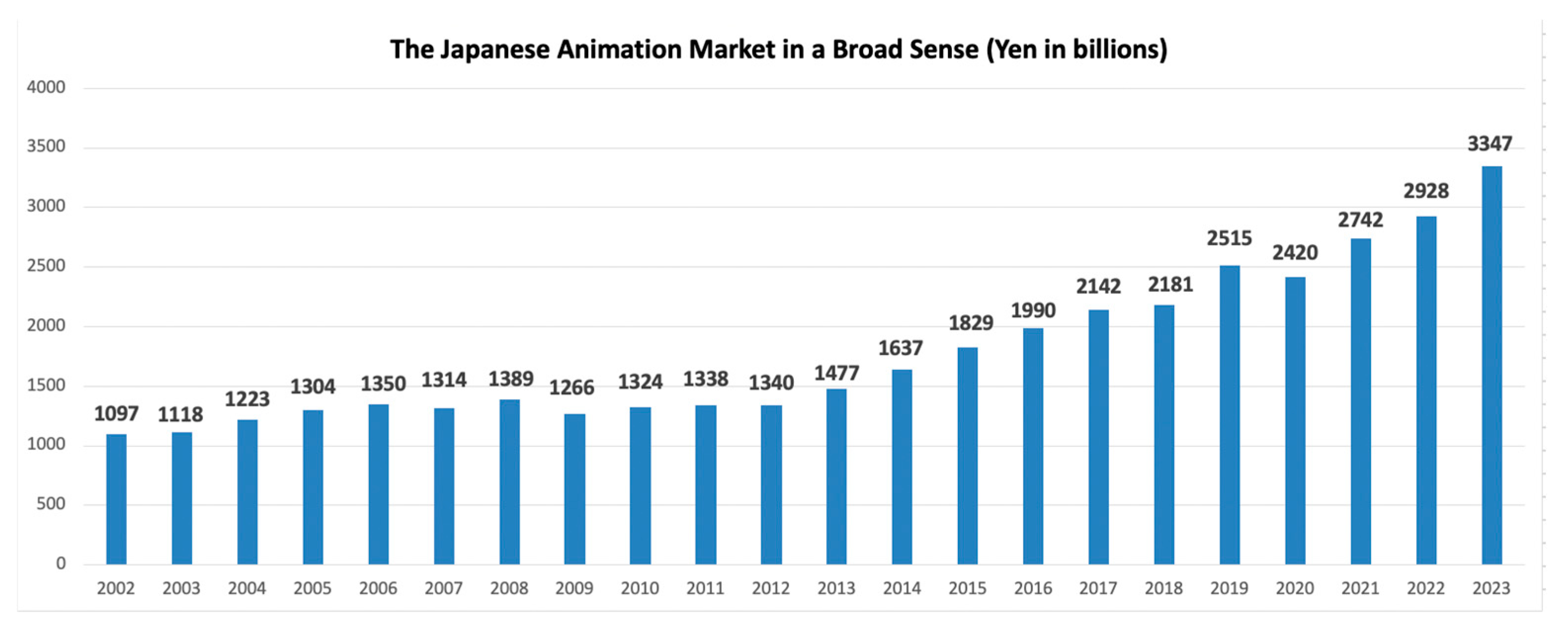

Apart from cosplayers, the audience is also a major consumer group that fosters the economic development of cosplay. In

Figure 7, The Association of Japanese Animation reported the market size of the Japanese animation market in the broad sense has increased gradually since 2002, reaching

$23.09 billion in 2023 (

The Association of Japanese Animations 2024). Broad sense refers not only to animation production itself, but also to the distribution of anime, copyright sales, merchandise, and projects related to animation IP, and so on. The slight decline in the middle part was due to the global financial crisis in 2008. Anime production technology in Japan has undergone significant evolution, from DVDs to digital painting, accompanied by advancements in lighting, color, and drawing techniques. The colors of the animation have become more vivid, and the movements of the characters have become more fluid. The character’s hair and eyes have more details. Additionally, the character designs in Japanese anime are interesting and bring out the charm of the characters. These cartoon characters have superpowers to save the world and fulfill people’s wishes, such as Astro Boy and Doraemon. The fascinating storyline portrays the personalities of each character (

Incredimate 2023). The improvement in picture quality and character design of anime has attracted an increasing number of viewers to watch it. Therefore, the market of Japanese animation has resumed growth and has an increasingly vast influence. Such a profound and rich history of animation promotes the development of subcultures. Japanese anime has gained a group of loyal viewers. A large proportion of viewers interested in anime characters become cosplayers. They decide to do cosplay because of their affection for the anime characters. They achieve a transformation from audience to performers. The development of anime has become an opportunity for cosplay to enter the public eye. Therefore, anime has promoted the development of cosplay, and cosplay has brought huge returns to the anime market. These cosplayers attend comic conventions to showcase their performances. On the one hand, their portrayal of the characters and their costumes attracts the audience at the comic convention. The audience develops an affinity for the characters and wants to know which anime the characters came from. They start to watch these animations and purchase anime merchandise. On the other hand, cosplayers post photos of the roles they play at different comic conventions online (

Ellard 2023). Some audiences develop an interest in cosplay after coming across exquisite cosplay photos online (

Barajas 2018). They engage in entertainment activities related to cosplay. This cultural consumption has led to explosive growth in the sales of anime merchandise. The peripheral products include books, dolls, cards, badges, and others. Japan becomes the world’s largest market for anime merchandise. More than half of the global revenue share of the anime merchandising market is contributed by Japan (

Grand View Research 2023). What’s more, Japan launched the “Cool Japan” policy, as reported by Foreign Policy magazine, aiming to enhance its cultural appeal globally. “Cool Japan” mainly promotes the influence of anime and comics (

Nagata 2012). With the promotion of Japanese popular, cosplayers from other countries have developed a fondness for the performance style of Japanese popular culture. To meet the demands of this fashionable and entertaining lifestyle, cosplayers in Indonesia have begun to purchase anime-related comics, toys, costumes, and so on. They hope to look different from others in their dress, making themselves the center of attention (

Suhaeb et al. 2021). An increasing number of international fans are attracted by anime and join the cosplay community, which has contributed to the growth of the anime merchandising market in Japan. They purchased numerous peripheral products featuring their favorite characters. This participation process in cosplay has brought significant benefits to the global anime merchandising market. The global anime merchandise market size has increased gradually from 2020 to 2024, reaching

$10.9 billion by 2024. According to this trend prediction, the market size is expected to grow at an annual rate of 9.4%. The anime merchandising market include figurine, clothing, board games, toys, posters, books, and others (

Grand View Research 2023). The large market size of the anime merchandising market has enhanced the international influence of Japanese popular culture and generated substantial revenue for the country. More tourists travel to Japan to attend comic conventions, which contributes to Japan’s economic growth.

The cosplay market drives the development of related industries. Theme restaurants and bars are the industries that benefit the most significantly. The decoration and food of the theme restaurant are related to a specific anime. For example, a café named “Baratie” is themed around the anime One Piece. The café’s name, “Baratie,” is derived from a floating restaurant ship in the anime One Piece. The sculpture at the entrance of the café is the character Sanji, who serves as a chef in this anime (

Okamoto Kitchen n.d.). Placing his figure within the restaurant aligns well with the overall theme, which corresponds to his culinary role in the original storyline. The decor of the restaurant is also centered on an ocean theme, featuring numerous ornaments of marine creatures throughout. The latte art of the coffee features character designs from One Piece. The food is designed based on elements that appear in One Piece, such as omelets with pirate hats and chocolate island desserts featuring coconut trees (

Okamoto Kitchen n.d.). The waiters in the restaurant also wear character costumes to provide service, which offers customers an immersive dining experience. Many customers who are fans of One Piece are willing to visit this restaurant for a meal. The theme restaurants not only attract customers who enjoy anime characters, but also provide employment opportunities for cosplayers. Akiko works as a manager of a cosplay bar. She works for the owner of the cosplay bar and holds related events. She often wears character costumes in the bar (

Truong and Gaudet 2020). Customers can interact with service staff dressed in their favorite character costumes during meals. Such a design has solved the employment problem for some people. Some anime enthusiasts without stable jobs can work in themed restaurants like “Baratie”. They are very happy to show their enthusiasm for cosplay while working. Customers also enjoy such immersive services, which encourage them to consume at the restaurant. Through immersive dining experiences, cosplay has contributed to the growth of the catering industry. The interaction between cosplayers and customers places the customers in the anime scenes. Customers will believe that the characters they like are having a conversation with them and creating stories together. Some customers who are not familiar with anime learn about One Piece and cosplay through its decorations and entertainment activities when they come to the restaurant for a meal. If they feel enjoyable in thematic restaurants, they are very likely to watch this anime and explore cosplay.

Additionally, cosplayers often visit themed restaurants to meet their photoshoot needs. Many anime fans also enjoy immersive dining experiences that allow them to taste food inspired by their favorite series. Anime cafés and restaurants represent an innovative sector within the cultural industries. Anime enthusiasts constitute a large potential consumer group, and their spending power has been increasingly recognized. These themed restaurants have identified and responded to such demands. They designed a lot of theme foods that attracted them to take photos as souvenirs. These restaurants also collaborate with many photography studios to attract cosplayers to come and take photos and make purchases (

Hu 2024). Anime-themed cafés provide settings designed after specific series, along with food items incorporating anime elements. Cosplayers are drawn to these locations because the restaurant environment fulfill their expectation for the design of fictional worlds and the environment that their characters live in. Unlike ordinary restaurants, these businesses create anime-inspired food designs and offer immersive interactions with staff members in themed costumes. The emotional value provided by the staff and the aesthetic appeal of the anime setting encourage cosplayers and anime fans to return and continue consuming. Therefore, the rise of this innovative industry helps attract the substantial consumer base formed by cosplayers.

Furthermore, cosplay contributes to the development of the venue rental industry and the photography industry. The organizers of anime expos and art festivals spend a considerable amount of money on renting venues to host events frequently. In February 2011, hundreds of events were held in the Kanto region (

Truong and Gaudet 2020). Moreover, cosplay has driven the economic development of the photography industry. Cosplay events require photo shoots and promotion, so the organizing party hires photographers to take pictures of the cosplayers. The organizers of Sakura-Con 2025 hired photographers from Mahou Photo to shoot for the anime convention. They uploaded the cosplay photos to the official photo booth gallery (

Smith 2025). By releasing photos of the 2025 anime convention, the organizers have begun to attract more cosplayers and audiences to participate in the 2026 event. When users browse the Sakura-Con official website and see the exquisite photos released by the organizers, they will become potential participants in upcoming events and pay more attention to the news on the official website. Therefore, the organizers can sell many tickets to the audience and recruit more cosplayers. Cosplayers also hire photographers to take pictures of the characters they play. They print their photos and take these photos to the comic conventions (

Cowan 2018). They exchange these photos as gifts with other cosplayers or give them to the audience attending the comic convention. These photos enhance cosplayers’ portrayal of the characters and increase their exposure, which helps them remain active in the cosplay community for a long time. Additionally, they post photos on social media of themselves in costume, striking a variety of poses as their characters (

Ellard 2023). By updating photos of their characters and editing the content of their cosplay on social media, they boost their popularity. They attract more fans and earn income in the process of operating social media. They desire to gain more attention and praise, so they constantly have demands for photography and high-quality photos. For these reasons, they frequently hire photographers to take pictures. Whenever they play different roles, they will hire photographers. Depending on the characteristics of different characters, they will also choose the shooting location and environment. The exposure of cosplay and the economy of the photography industry benefit each other, but the expenditure of cosplayers as a consumer group is unstable. Cosplayers are a significant group that bridges the connection between cosplay and the photography industry. As cosplay culture has expanded, photography studios have increasingly recognized cosplayers as a potential consumption group. Many studios design anime-themed rooms and collaborate with cafes, heritage buildings, and other businesses to offer a diverse range of shooting locations (

Hu 2024). These shooting locations met the camera requirements for cosplayers to play different roles. They will also invite some cosplayers to promote their studio. A rental space company named SPS has taken advantage of collaborating with well-known cosplayers on social media, allowing these cosplayers to use the photography studio for free. These cosplayers included the name of their studio and the SPS website in the photos they posted on social media, which helped promote the photography studio (

Hu 2024). Photography studios have reaped substantial profits by capitalizing on the fan economy. When fans browse the posts of well-known cosplayers, they will notice the information about the studio. This promotion attracts many cosplayers to these photography studios for shooting. The benefits gained by the photography studio are far greater than those of these cosplayers.

In addition, the organizers of the comic convention capitalize on the enthusiasm of cosplayers for cosplay to generate substantial profits. Many cosplayers do cosplay based on their interests and hobbies. Many of them are students. These cosplayers need to buy their own tickets, just like tourists, to participate in the comic convention. They are participants rather than performers hired by the comic convention. According to the researchers’ observations, comic conventions often feature dedicated performance activities at specific times. The cosplayers themselves are responsible for preparing the costumes, purchasing tickets, and spending at the comic convention. Such high consumption can easily reduce the stickiness of some cosplayers to the cosplay hobby. The organizers have become the best beneficiaries. The organizers of the comic convention, as decision-makers, failed to alleviate the pressure on cosplayers to consume. The cultural industry has underestimated its efforts. If the cosplay industry wants to address this potential issue of unequal profits, the organizers should provide visible services for cosplayers and cover ticket fees for them. These visible services include the supply of venue food, shooting fees, and support for distributing the surrounding area. The anime convention is a gathering place for cosplayers and audiences. The primary purpose of attending the comic convention is to take photos with their favorite characters and experience the entertainment atmosphere of the convention. Without an abundance of cosplayers participating in the comic convention, the comic convention would not have reaped huge profits. The cultural industry and comic convention organizers should pay more attention to the feelings of consumers to retain the huge customer group of cosplayers. They should respect the efforts of cosplayers and share some of their expenses instead of constantly taking advantage of their enthusiasm for cosplay to consume their value. Cosplayers will continue to create value for the cosplay industry only when they enjoy the benefits of consumption. This mutually beneficial approach can promote the circular development of the industry.