Payment of Participants with Disability in Research: A Scoping Review and Framework

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Researcher Positioning

4. Results

5. Discussion

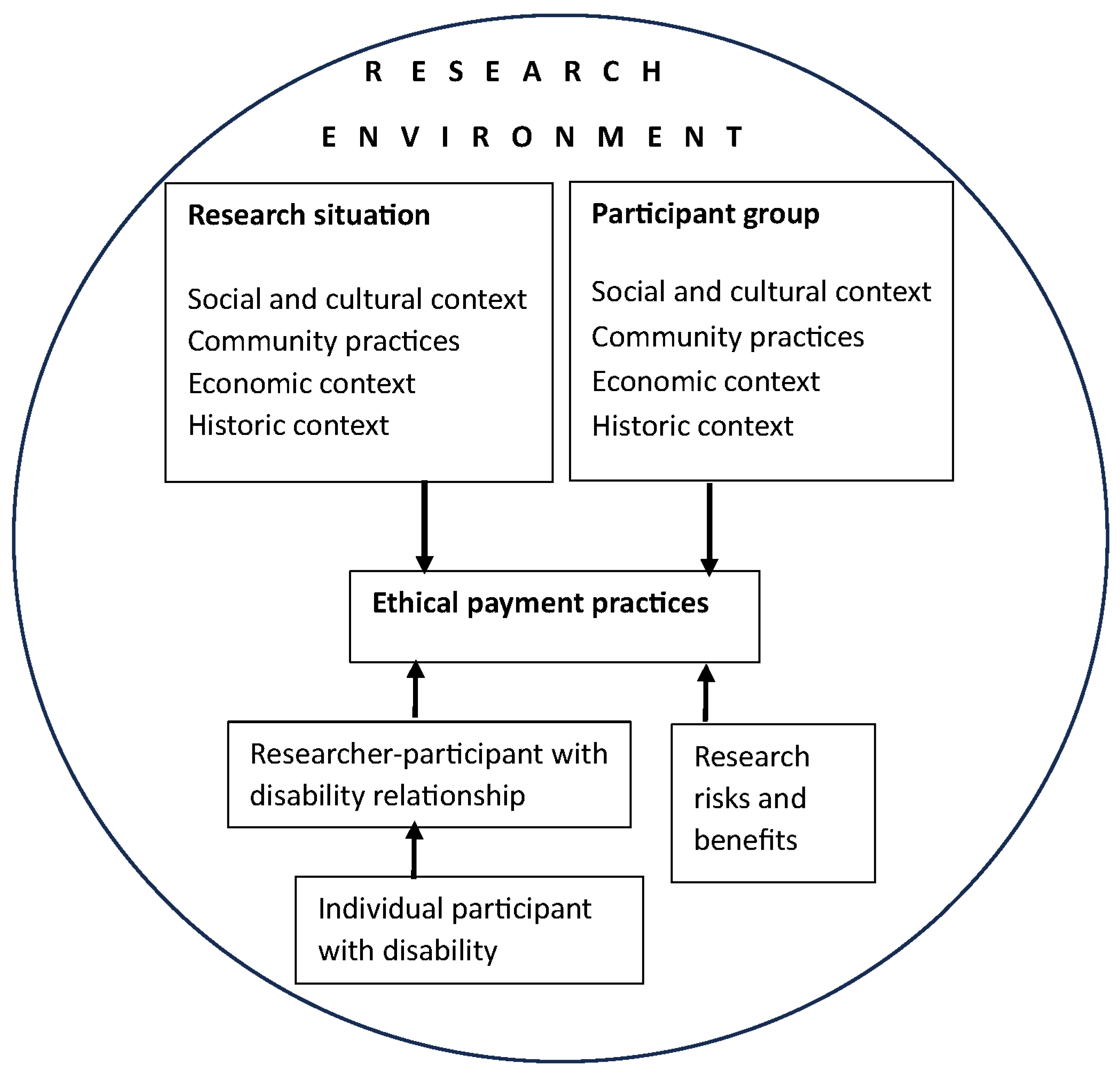

5.1. Factors Influencing Decision-Making Around Payment

5.2. Key Ethical Concepts

5.3. Utility of Existing Guidelines and the Need for a Contextual Framework for Decision-Making

5.4. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aldridge, Jo. 2019. “With Us and About Us”: Participatory Methods in Research with “Vulnerable” or Marginalized Groups. Singapore: Springer, pp. 1919–34. [Google Scholar]

- Arksey, Hilary, and Lisa O’Malley. 2005. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 8: 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsenault-Gallant, Hannah. 2025. Uncovering Ableism in Martha Fineman’s Ontological Vulnerability and Resilience Theory: A Critical Disability Theory Perspective. Critical Disability Discourses 10: 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailie, Jodie, Nicola Fortune, Karleen Plunkett, Julie Gordon, and Gwynnyth Llewellyn. 2023. A call to action for more disability-inclusive health policy and systems research. BMJ Global Health 8: e011561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballantyne, Angela. 2008. Benefits to research subjects in international trials: Do they reduce exploitation or increase undue inducement? Developing World Bioethics 8: 178–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, Malou. 2024. Empowering Vulnerability: The Social Model of Disability and Digital Government. Technology and Regulation 2024: 273–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, Kirsten, and Amy Salmon. 2011. What women who use drugs have to say about ethical research: Findings of an exploratory qualitative study. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics 6: 84–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, Valarie, Steve Joffe, and Eric Kodish. 2011. Harmonization of ethics policies in pediatric research. The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics 39: 70–78. [Google Scholar]

- Blödt, Susanne, Claudia M. Witt, and Christine Holmberg. 2016. Women’s reasons for participation in a clinical trial for menstrual pain: A qualitative study. BMJ Open 6: e012592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracken-Roche, Dearbhail, Emily Bell, and Eric Racine. 2016. The “vulnerability” of psychiatric research participants: Why this research ethics concept needs to be revisited. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 61: 335–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Brandon, Logan Marg, Zhiwei Zhang, Dario Kuzmanović, Karine Dubé, and Jerome Galea. 2019. Factors Associated With Payments to Research Participants: A Review of Sociobehavioral Studies at a Large Southern California Research University. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics 14: 408–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capri, Charlotte, and Leslie Swartz. 2018. ‘We are actually, after all, just children’: Caring societies and South African infantilisation of adults with intellectual disability. Disability & Society 33: 285–308. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, Alexandra B., Carol Strike, Adrian Guta, Rosalind Baltzer Turje, Patrick McDougall, Surita Parashar, and Ryan McNeil. 2017. “We’re giving you something so we get something in return”: Perspectives on research participation and compensation among people living with HIV who use drugs. International Journal of Drug Policy 39: 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connon, Irena L. C., and Edward Hall. 2021. ‘It’s not about having a back-up plan; it’s always being in back-up mode’: Rethinking the relationship between disability and vulnerability to extreme weather. Geoforum 126: 277–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, Kay, and Karl Nunkoosing. 2008. Maintaining dignity and managing stigma in the interview encounter: The challenge of paid-for participation. Qualitative Health Research 18: 418–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cseko, Gary C., and William J. Tremaine. 2013. The role of the institutional review board in the oversight of the ethical aspects of human studies research. Nutrition in Clinical Practice 28: 177–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, Peter, Bruce Bradbury, and Melissa Wong. 2022. Poverty in Australia 2022: A Snapshot. Sydney: Australian Council of Social Service (ACOSS) and UNSW Sydney. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, Laura B., Daniel S. Kim, Ian E. Fellows, and Barton W. Palmer. 2009. Worth the risk? Relationship of incentives to risk and benefit perceptions and willingness to participate in schizophrenia research. Schizophrenia Bulletin 35: 730–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ells, Carolyn. 2001. Lessons about autonomy from the experience of disability. Social Theory and Practice 27: 599–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, Maurice A., J. Bosett, C. Collet, and P. Burnham-Riosa. 2014. Where are persons with intellectual disabilities in medical research? A survey of published clinical trials. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 58: 800–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fricker, Miranda. 2007. Epistemic Injustice: Power and the Ethics of Knowing. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fry, Craig L., Alison Ritter, Simon Baldwin, Kathryn J. Bowen, Paul Gardiner, Tracey Holt, Rebecca Jenkinson, and Jennifer Johnston. 2005. Paying research participants: A study of current practices in Australia. Journal of Medical Ethics 31: 542–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garland-Thomson, Rosemarie. 2012. The case for conserving disability. Journal of Bioethical Inquiry 9: 339–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelinas, Luke, Sarah A. White, and Barbara E. Bierer. 2020. Economic vulnerability and payment for research participation. Clinical Trials 17: 264–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goyal, Namrata, Matthew Wice, and Joan G. Miller. 2017. Ethical issues in cultural research on human development. In Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences. Singapore: Springer, pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Grady, Christine. 2005. Payment of clinical research subjects. The Journal of Clinical Investigation 115: 1681–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Head, Emma. 2009. The ethics and implications of paying participants in qualitative research. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 12: 335–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, Matthew R., and Beatrice Godard. 2013. Beyond procedural ethics: Foregrounding questions of justice in global health research ethics training for students. Global Public Health 8: 713–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iltis, Ana S. 2009. Payments to normal healthy volunteers in phase 1 trials: Avoiding undue influence while distributing fairly the burdens of research participation. Journal of Medicine and Philosophy 34: 68–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagoe, Caroline, Caitlin McDonald, Minerva Rivas, and Nora Groce. 2021. Direct participation of people with communication disabilities in research on poverty and disabilities in low and middle income countries: A critical review. PLoS ONE 16: e0258575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuper, Hannah, Shaffa Hameed, Veronika Reichenberger, Nathaniel Scherer, Jane Wilbur, Maria Zuurmond, Islay Mactaggart, Tess Bright, and Tom Shakespeare. 2021. Participatory research in disability in low-and middle-income countries: What have we learnt and what should we do? Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research 23: 328–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, Sally, Kristina Fuentes, Sharmigaa Ragunathan, Luiza Lamaj, and Jaclyn Dyson. 2023. Ableism within health care professions: A systematic review of the experiences and impact of discrimination against health care providers with disabilities. Disability and Rehabilitation 45: 2715–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macklin, Ruth. 1981. ‘Due’ and ‘undue’ inducements: On pasing money to research subjects. IRB: Ethics & Human Research 3: 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- McGregor, Kirsty, Bethan Taylor, and Lisa Oakley. 2023. Power, Participation, Payment and Platform: Ethical and Methodological Issues in Recruitment in Qualitative Domestic Abuse Research. Journal of Family Violence 38: 1029–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellifont, Damian, Jennifer Smith-Merry, and Kim Bulkeley. 2023. The employment of people with lived experience of disability in Australian disability services. Social Policy & Administration 57: 642–55. [Google Scholar]

- Mellifont, Damian, Jennifer Smith-Merry, Helen Dickinson, Gwynnyth Llewellyn, Shane Clifton, Jo Ragen, Martin Raffaele, and Paul Williamson. 2019. The ableism elephant in the academy: A study examining academia as informed by Australian scholars with lived experience. Disability & Society 34: 1180–99. [Google Scholar]

- Mertens, Donna M. 2012. Ethics in qualitative research in education and the social sciences. In Qualitative Research: An Introduction to Methods And Designs. Edited by Stephen D. Lapan, MaryLynn T. Quartaroli and Frances J. Riemer. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, pp. 19–39. [Google Scholar]

- Milford, Cecilia, Tammany Cavanagh, Yolandie Ralfe, Virginia Maphumulo, Mags Beksinska, and Jennifer Smit. 2022. How is Clinical Trial Reimbursement Money Spent? South African Trial Participants’ Reported Reimbursement Spending Patterns and Perceptions of Appropriate Reimbursement Amounts. Aids and Behavior 26: 604–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mustaniemi-Laakso, Maija, Hisayo Katsui, and Mikaela Heikkilä. 2023. Vulnerability, disability, and agency: Exploring structures for inclusive decision-making and participation in a responsive state. International Journal for the Semiotics of Law-Revue internationale de Sémiotique Juridique 36: 1581–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research. 1979. The Belmont Report: Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects of Research; Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

- National Health and Medical Research Council. 2007. National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research. Canberra: National Health and Medical Research Council. [Google Scholar]

- National Health and Medical Research Council. 2019. Payment of Participants in Research: Information for Researchers, HRECs and Other Ethics Review Bodies. Canberra: National Health and Medical Research Council. [Google Scholar]

- Ottati, Victor, Galen V. Bodenhausen, and Leonard S. Newman. 2005. Social Psychological Models of Mental Illness Stigma. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, pp. 99–128. [Google Scholar]

- People with Disability Australia. 2025. Language Guide. Available online: https://pwd.org.au/resources/language-guide/ (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Phillips, Trisha B. 2011. A living wage for research subjects. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics 39: 243–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillai, Pooja, Meenal Rawat, Sumeet Jain, Rachelle Anne Martin, Kakul Shelly, and Kaaren Mathias. 2023. Developing relevant community mental health programmes in North India: Five questions we ask when co-producing knowledge with experts by experience. BMJ Global Health 8: e011671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polacsek, Meg, Gayelene Boardman, and Terence V. McCann. 2017. Paying patient and caregiver research participants: Putting theory into practice. Journal of Advanced Nursing 73: 847–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roca, Teresa, and Peter Bates. 2014. Uncovering the values that motivate people in relation to payments for involvement in research. Mental Health and Social Inclusion 18: 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, Wendy. 2013. Vulnerability and Bioethics. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Scully, Jackie Leach. 2013. Disability and Vulnerability. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Merry, Jennifer. 2019. Inclusive Disability Research. In Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences. Edited by Pranee Liamputtong. Singapore: Springer, pp. 1935–52. [Google Scholar]

- Snipstad, Øyvind Ibrahim Marøy. 2022. Concerns regarding the use of the vulnerability concept in research on people with intellectual disability. British Journal of Learning Disabilities 50: 107–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soldatic, Karen. 2018. Disability poverty and ageing in regional Australia: The impact of disability income reforms for indigenous Australians. Australian Journal of Social Issues 53: 223–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Jieun, Robert S. Dembo, Leann Smith DaWalt, Carol D. Ryff, and Marsha R. Mailick. 2023. Improving Retention of Diverse Samples in Longitudinal Research on Developmental Disabilities. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities 128: 164–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steele, Linda. 2023a. Ending disability segregated employment:‘modern slavery’law and disabled people’s human right to work. International Journal of Law in Context 19: 217–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, Linda. 2023b. Law and Disability ‘Supported’ Employment in Australia: The Case for Ending Segregation, Discrimination, Exploitation and Violence Against People with Disability at Work. Monash University Law Review 49: 43–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stineman, Margaret G., and David W. Musick. 2001. Protection of human subjects with disability: Guidelines for research. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 82: S9–S14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surmiak, Adrianna. 2020. Ethical concerns of paying cash to vulnerable participants: The qualitative researchers’ views. The Qualitative Report 25: 4461–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swan, Nicola, and Trevor Long. 2011. Ethics in a Developing Country Context. Paper presented at the 10th European Conference on Research Methodology for Business and Management, Caen, France, June 20–21. [Google Scholar]

- Tishler, Carl L., and Suzanne Bartholomae. 2002. The recruitment of normal healthy volunteers: A review of the literature on the use of financial incentives. The Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 42: 365–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, Andrea C., Erin Lillie, Wasifa Zarin, Kelly K. O’Brien, Heather Colquhoun, Danielle Levac, David Moher, Micah D. J. Peters, Tanya Horsley, and Laura Weeks. 2018. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine 169: 467–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. 2005. Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights. Geneva: The United Nations. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. 2013. The Principle of Respect for Human Vulnerability and Personal Integrity: Report of the International Bioethics Committee of UNESCO (IBC). Geneva: The United Nations. [Google Scholar]

- VanderWalde, Ari, and Seth Kurzban. 2011. Paying human subjects in research: Where are we, how did we get here, and now what? Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics 39: 543–58. [Google Scholar]

- Vanyoro, Kudakwashe. 2023. Rethinking Power and Reciprocity in the “Field”. In The Palgrave Handbook of South–South Migration and Inequality. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 105–23. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, Rebecca L., Douglas MacKay, Margaret Waltz, Anne D. Lyerly, and Jill A. Fisher. 2023. Ethical Criteria for Improved Human Subject Protections in Phase I Healthy Volunteer Trials. Ethics & Human Research 44: 2–21. [Google Scholar]

- Warnock, Rosalie, Faith MacNeil Taylor, and Amy Horton. 2022. Should we pay research participants? Feminist political economy for ethical practices in precarious times. Area 54: 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, Chloë, Graham Baker, Nanette Mutrie, Ailsa Niven, and Paul Kelly. 2020. Get the message? A scoping review of physical activity messaging. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 17: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Medical Association. 2013. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. JAMA 310: 2191–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author(s) and Date | Study Location | Low- or Middle-Income Setting | Study Population | Context of Study | Methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blake et al. (2011) | US, Japan, and European Union | No | Children as participants in clinical trials. | Examines the creation of harmonised guidelines for paediatric clinical trial research. Focus on research broadly but discusses payment as part of this. | Commentary based on comparative policy analysis. Discussion of regulation with examples. |

| Song et al. (2023) | US | No | Parents of children with developmental disability vs. those without. | It is about retention of parents of children with developmental disability in studies generally. Discusses payment as part of the overall paper. | Quantitative methods. Secondary data analysis examining retention data from a longitudinal study. |

| Collins et al. (2017) | Canada | No | People with HIV who also use drugs. | Focus is on equity in compensation and the place of compensation in research for this group, who are often positioned as vulnerable. | Qualitative. Focus groups. |

| Milford et al. (2022) | South Africa | Yes | People involved in clinical trials. | Examines how participants spent money provided to them for participation in research. Examines acceptable reimbursement levels. | Mixed methods—qualitative and quantitative. Questionnaire and focus groups with women involved in a clinical trial. |

| Bell and Salmon (2011) | Canada | No | Women who use drugs. | Talks to women who use drugs about their motivations for being involved in research and attitudes to research participation, and ideas about what ethical research is in their context. | Qualitative. Focus groups. |

| Dunn et al. (2009) | US, San Diego | No | Middle aged and older people with schizophrenia in supported accommodation. | Uses scenarios to understand how incentives operate in relation to choices about research participation for people with schizophrenia. | Quantitative. Vignette-based survey responses. |

| Cook and Nunkoosing (2008) | Australia, Melbourne | No | Older people living in poverty. | Reflects on research where participants were provided payment and the impact of this on the research encounter. Interested in how this impacts the interview. | Qualitative. Interviews and reflexive response. |

| Swan and Long (2011) | India | Yes | Non-government organisations, funders, recipients of development in rural communities in India. | Looks broadly at ethical issues in ethnography in developing countries but includes a discussion of payment. | Critical reflection on an ethnographic study. |

| Ballantyne (2008) | Developing countries | Yes | People in developing countries. | Examines exploitation and inducement in international externally sponsored studies conducted in developing countries. | Expert discussion. Critical discussion based on examples. |

| Walker et al. (2023) | No specific location | No | Healthy volunteers. | General discussion of ethical criteria in phase one ‘healthy volunteer’ trials but discusses payment as part of that. | Expert discussion. |

| Tishler and Bartholomae (2002) | No specific location | No | Normal health volunteers. | Examines payment and motivations of ‘normal healthy volunteers’ and possible economic vulnerability. | Qualitative. Narrative literature review. |

| Roca and Bates (2014) | United Kingdom, East Midlands | No | Health research stakeholders. | Considers health researcher views on payment, including reasoning for payment and rates of payment. | Quantitative. Survey of health stakeholders. |

| Surmiak (2020) | Poland | No | Researchers. | Researchers who conduct qualitative research with people in vulnerable groups to understand their motivations for and against payment. | Qualitative. In-depth interviews. |

| Iltis (2009) | US | No | Normal health volunteers. | Addresses low payment in the context of recruitment. | Expert discussion. |

| Gelinas et al. (2020) | No specific location | No | Economically vulnerable individuals. | Discusses economic vulnerability in relation to payment, particularly in research undertaken in areas to reduce costs. | Expert discussion. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Smith-Merry, J.; Mellifont, D. Payment of Participants with Disability in Research: A Scoping Review and Framework. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 374. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14060374

Smith-Merry J, Mellifont D. Payment of Participants with Disability in Research: A Scoping Review and Framework. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(6):374. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14060374

Chicago/Turabian StyleSmith-Merry, Jennifer, and Damian Mellifont. 2025. "Payment of Participants with Disability in Research: A Scoping Review and Framework" Social Sciences 14, no. 6: 374. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14060374

APA StyleSmith-Merry, J., & Mellifont, D. (2025). Payment of Participants with Disability in Research: A Scoping Review and Framework. Social Sciences, 14(6), 374. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14060374