Abstract

Background/Objectives: Currently, the type of population reproduction in China has changed to “low birth, low death, low growth”. Additionally, as the number of single people has increased and the number of women of childbearing age has decreased, the growth of the total population was bound to show a negative trend. Therefore, this study aimed to understand what factors influence fertility intentions from the perspective of single, unmarried women. Methods: We designed our own online questionnaire and collected information on fertility intentions from single, unmarried women of childbearing age (18–49 years). A total of 741 questionnaires were collected, with a valid response rate of 92.6%, and the Theory of Planned Behavior model was integrated into the questionnaire survey. Statistical analysis was performed via SPSS 24.0, and AMOS 24.0 software’s analysis of variance was used to determine whether there were differences in attitudes towards fertility intentions among respondents. Structural equation models were constructed via AMOS software for validation factor analysis and path analysis. Results: There was a significant difference (p < 0.05) in “monthly income”, “net family income”, “health status”, and “only-child status”. Structural equation modelling revealed that fertility attitudes (β1 = 0.301, p < 0.05), subjective norms (β2 = 0.295, p < 0.05), and perceived behavioural control (β3 = 0.146, p < 0.05) positively influence fertility intentions. Conclusions: The fertility intentions of single, unmarried women of childbearing age in China are influenced by many factors. Therefore, society should pay more attention to the rights and interests of single, unmarried women and provide a better social environment for childbearing; in addition, it is possible to appropriately relax the fertility policy of single births to improve the low fertility rate in China.

1. Introduction

The low-fertility phenomenon has become a global trend, and the population crisis is gradually spreading from developed countries in Europe and the United States to developing countries. The period 1991–2021 was a period of stable population development. Under the dual influence of economic and social development and family planning policies, the population growth rate gradually declined and levelled off. During this period, the national population increased from 1.16 billion in 1991 to 1.41 billion in 2021, an increase of 250 million, with an average annual growth rate of 8.48 million. However, in 2022, China’s population growth began to show a negative trend, and the number of new births in China in 2023 was predicted to be 9.02 million, with a natural growth rate of −1.48 per thousand. The nature of population reproduction in China has changed from “high births, low deaths and high growth” to “low births, low deaths and low growth” (National Bureau of Statistics of China 2024). To address the current fertility situation, the Chinese government introduced the “two-child policy” and the “three-child policy” between 2013 and 2021 (Marois et al. 2021; Zeng and Hesketh 2016). However, the open-ended fertility policy has not been able to mitigate China’s negative population growth trend, and the fertility rate has continued to decrease in recent years. The modern demographic transition has been completed, and China has entered a new stage of population development. It is expected that negative population growth will continue beyond the end of this century, with a slow trend in the short term and a fast trend in the long term. Faced with the pressure of continued fertility decline, it has become imperative to accelerate research on solutions to the low-fertility problem that are adapted to the national conditions in China to improve the fertility policy support system and to build a fertility-friendly society.

In addition, as the main population affecting fertility rates, women are the primary factor in determining fertility. According to the China Population and Employment Statistics Yearbook 2023, the population of single individuals in China exceeded 240 million by the end of 2022; this population is expected to reach 300 million by 2024, with approximately 116 million single women (National Bureau of Statistics of China 2023). Single women are defined as women who live alone without a spouse after reaching adulthood and include unmarried, divorced, and widowed women. Women of childbearing age are defined as women who are capable of giving birth, and the age of a woman of childbearing age is generally defined as 15–49 years; however, the number of women of childbearing age decreased from 360 million in 2010 to 320 million in 2020 and 310 million in 2022 (National Development and Reform Commission 2023). Therefore, the number of women of childbearing age will continue to decrease during the 14th Five-Year Plan period, and the trend of negative population growth in society as a whole will inevitably be observed (Cao 2024). Women of childbearing age constitute the main component of the population. In addition to their individual attitudes towards childbearing, other factors, such as the state, society and family status, affect single, unmarried women’s willingness to give birth; for example, at the current legal level, there are certain restrictions on childbearing among single women (Li et al. 2023), and the current situation of delayed marriage also affects the willingness to give birth (Yang et al. 2022). Therefore, more attention should be given to the fertility intentions (FIs) of single, unmarried women of childbearing age to understand the current fertility situation.

Previous research has focused on the perceptions and attitudes of different groups of people towards fertility, for example, the attitudes of married women of childbearing age towards having two or three children and the FIs of young university students (Song and Xiao 2024; Yang et al. 2023b; Zhang et al. 2022a); on the other hand, research focusing on measuring FIs via different research methods, such as the use of online public opinion data to infer changes in the public’s propensity to have children, and the literature suggest that the use of the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) model is a more effective way to measure FIs (Miller and Pasta 1995; Yargawa et al. 2021; Zheng 2012). At present, only a small number of studies have investigated the FIs of single and unmarried women; in addition, in terms of research methodology, most studies have used mediating effect analysis and structural equation modelling to investigate the extent of the influence of various variables on FIs, whereas a small number of studies have used the TPB model, which is not a very mature model in the field of FIs.

Therefore, in order to research the reasons for the current low fertility rate in China and to find ways to alleviate the problem, the aims of this study were to integrate factors related to the state, society, family and individual affecting FIs into the TPB model in light of China’s current fertility policy and social background; to optimize the structural equation model through information from the literature; and to investigate the target group of single and unmarried women of childbearing age in China to determine which factors affect FIs from the perspective of single and unmarried women.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

The target population of this study was single, unmarried Chinese women of childbearing age, so the age of the respondents was defined as 18–49 years old, and single women were defined as adult women living alone without a spouse, including unmarried, divorced, and widowed women. In the legal sense, a single woman is a woman who is not legally married, so married and pregnant women were excluded from this study. The survey was conducted via the online data collection website Questionnaire Star, and the sample size was calculated on the basis of the minimum sample size formula (Equation (1)) Minimum sample size formula:

where Zα/2 is the value of the Z statistic when the confidence level is 1 − α, corresponding to the 95% confidence level of the Z value, that is, 1.96; P is the expected probability of success or proportion, set to 50%; and E is the allowable error. This study used a value of 5%, which was substituted into the formula, and a sample size of 384 was obtained. In addition, the sample size could be empirically multiplied by the “design effect” of 1.2 (Ni et al. 2010), i.e., the minimum sample size was 384 (*) × 1.2 = 461. In this study, 800 questionnaires were distributed, and 741 questionnaires were returned, with an effective return rate of 92.6%.

The questionnaires were collected anonymously from June to August 2024 on the ‘Wenjuanxing’ website (https://www.wjx.cn) (Accessed on 2 May 2024), and the distribution of questionnaires was conducted through prominent social media platforms, including WeChat and Weibo. The sample was mainly collected using simple random sampling. The target population for the questionnaire was single, unmarried women of childbearing age. The questionnaire was distributed to the target population via a targeted distribution on forums. The 741 respondents were made aware of the purpose and content of the survey and signed an informed consent form before completing the questionnaire. All participants were assured that their data would be kept confidential. They could withdraw from the study at any time as their participation was entirely voluntary.

Furthermore, according to the notice issued by the China Healthcare Commission, Article 32 states that the use of human information data or biological samples for life sciences and medical research involving humans may be exempt from ethical review under certain circumstances, provided it does not cause harm to individuals or involve sensitive personal information or commercial interests. Therefore, our study did not require further ethics committee approval as it did not involve animal or human clinical trials and was not unethical. No potential competing interests were reported by the author(s).

2.2. Questionnaire Design

Part 1: Sociodemographic characteristics

A sociodemographic background information questionnaire was edited and used for data collection. This questionnaire contains a total of eight questions on age, household, place of residence, education level, monthly income, annual income of the family of origin, health status, and only-child status.

Part 2: Fertility intentions

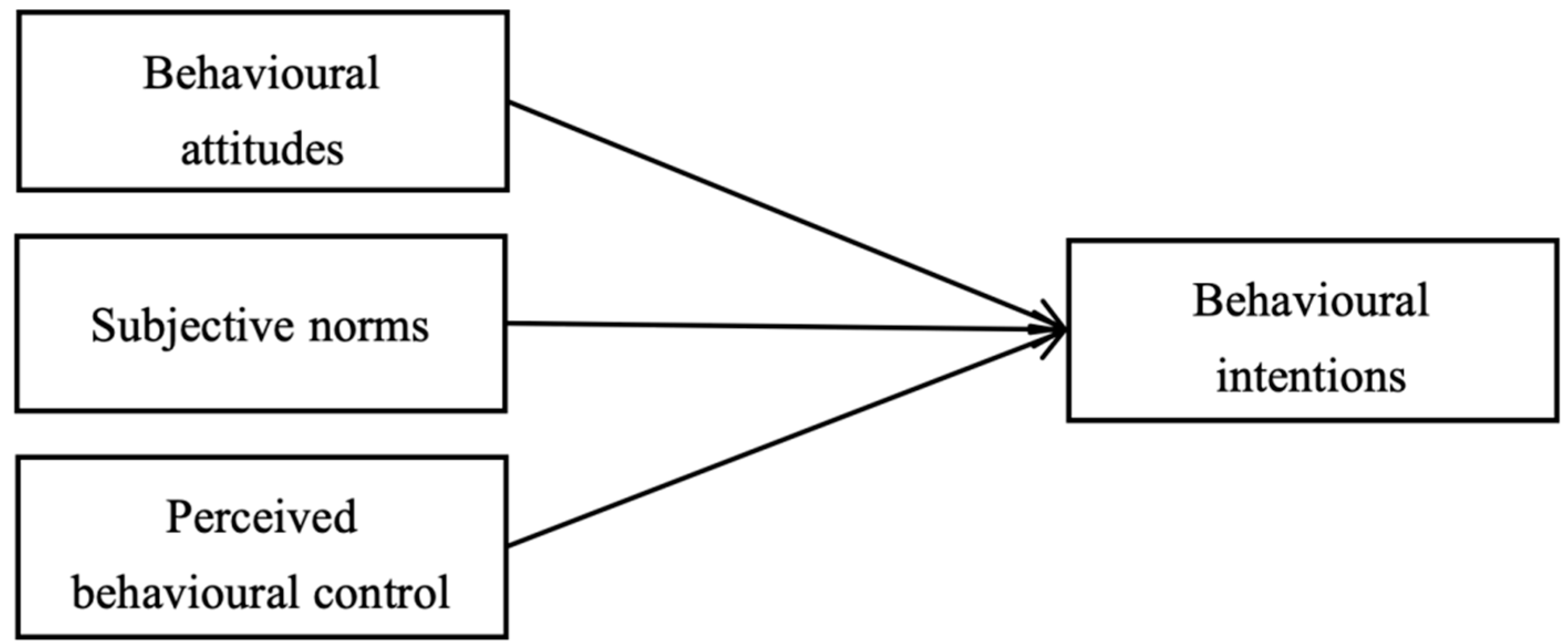

The FI section of the questionnaire incorporates the TPB model. The TPB model is a theory of rational behaviour that was developed by Ajzen and Fishbein. The theory posits that behavioural intentions are influenced by behavioural attitudes, subjective norms (SNs), and perceived behavioural control (PBC) as direct determinants of actual behaviour and aims to predict and explain intentional behaviour in specific situations (Ajzen 2002; Mao and Luo 2013).

Fertility attitudes (FAs) refer to the assessment of the degree of agreement or disagreement an individual holds towards having a child, and an individual’s attitudes towards having a child can have a significant effect on their motivation to carry out the act; this section is divided into six sections to measure respondents’ attitudes towards having a child, and the items are scored via a five-point Likert scale ranging from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’.

SNs are the social pressures that individuals feel when making fertility decisions and are influenced by family members, friends, colleagues, and social opinion in the decision-making process. This section is divided into six parts with questions on a five-point Likert scale from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’.

PBC refers to the degree of control an individual perceives that they have over their reproductive behaviour, in terms of the ability, resources, opportunities, etc., to carry out reproductive behaviour. This includes economic conditions, health status, caregiver availability, inclusive policies, etc. The section is divided into nine parts, and the items are scored using a five-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”.

FIs were defined as the wishes of single, unmarried women of childbearing age with respect to whether they want to have children. FIs were evaluated via a questionnaire consisting of four parts; the items are on a five-point Likert scale ranging from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’.

The framework diagram of the structural equation model is shown below (Figure 1):

Figure 1.

The structural equation model.

Therefore, on the basis of the TPB model, we propose the following three hypotheses:

H1.

Fertility attitudes affect fertility intentions.

H2.

Subjective norms affect fertility intentions.

H3.

Perceived behavioural control affects fertility intentions.

2.3. Data Analysis

Questionnaire data were pre-processed for screening and allocation. The quality of the questionnaire was assured using the questionnaire reliability test and statistically analyzed via SPSS 24.0 and AMOS 24.0. We used descriptive analysis to describe the sociodemographic characteristics of the single, unmarried women of childbearing age and analysis of variance to determine whether there were differences in attitudes towards FIs among the respondents. Finally, structural equation models were constructed via AMOS software for validation factor analysis and path analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Characteristics

A total of 741 respondents were surveyed: the population mainly comprised women aged 25–29 years (39.41%), women from urban households (59.37%), women living in the city (95.41%), women with undergraduate degrees (52.09%), women with an income of 9000 RMB or more (27.26%), women with a family income of CNY 100,000–500,000 (31.04%), women with an outstanding health status (35.9%), and women who were not only children (55.60%) (Table 1). The results of the analysis of differences between basic demographic information and FIs revealed that the FIs of single, unmarried women of childbearing age in China significantly differed (p < 0.05) and fell into in the following categories: “age”, “residence permit”, “education level”, “monthly income”, “annual net family income”, “health status”, and “only-child status”.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the respondents (n = 741).

3.2. Convergent Validity Analysis

According to the results of the aggregated validity analysis shown in Table 2, the absolute value of the standardized loading coefficients of each measurement relationship was greater than 0.6 and statistically significant, which indicates that the measurement relationships had good performance. Moreover, this validated confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) included four factors and 25 analysis items. As shown in the table, the average variance extracted (AVE) values of these four factors were greater than 0.5, and the composite reliability (CR) values were greater than 0.7. These indicators indicate that the data have strong convergent validity, indicating that the measurement tool used has good reliability and validity in capturing the underlying factors.

Table 2.

Reliability and validity analysis.

3.3. Distinguishing Validity Analyses

Table 3 shows the results of the discriminant validity analysis. For FIs, the AVE square root value was 0.7578, which was greater than the maximum absolute value of the interactor correlation coefficient of 0.314, indicating good discriminant validity. The AVE square root of PBC was 0.7622, which was greater than the maximum absolute value of the correlation coefficient between the factors (0.393), indicating good discriminant validity. The square root AVE value of SNs was 0.7355, which was greater than the maximum absolute value of the interactor correlation coefficient of 0.461, indicating that it has good discriminant validity. The AVE square root value of FAs was 0.7893, which was greater than the maximum value of the absolute value of the interactor correlation coefficient of 0.461, indicating good discriminant validity.

Table 3.

Distinguishing validity analyses.

3.4. Structural Equation Modelling

The structural model was evaluated by testing goodness-of-fit indices and variance explained estimates. The goodness-of-fit indices of the structural model, which indicated that the model was well fitted, were as follows: χ2/df = 3.569; GFI = 0.891; root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.059; comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.930; and NFI = 0.906. Despite the GFI value of 0.891 being marginally lower in this study than the conventional standard of 0.90, the CFI (0.930), and the RMSEA (0.059) indicate an adequate model fit. Additionally, references have been made indicating that a GFI greater than 0.8 is also acceptable (Baumgartner and Homburg 1996; William et al. 1994). Table 4 shows the path coefficients of the structural model. The results show that the p-values are less than 0.05, which means that there is a significant relationship between the path coefficients of all the variables, and H1 shows the relationship between FAs and FIs. Structural equation modelling revealed that FAs (β1 = 0.301, p < 0.05) positively influenced the FIs of single, unmarried women of childbearing age, and H1 was supported. Similarly, SNs (β2 = 0.295, p < 0.05) and PBC (β3 = 0.146, p < 0.05) both had positive effects on FIs, and the H2 and H3 were supported.

Table 4.

Structural equation model of the study hypotheses.

4. Discussion

This study focused on single, unmarried women of childbearing age to examine the current situation of FIs and their influencing factors in contemporary China. We used an online questionnaire to collect data. Online questionnaires have been used in various academic research fields, but the quality of data from online questionnaires is still questioned. Some studies have shown that data quality control can be carried out at different stages of questionnaire collection, for example, at the sampling stage, respondent-driven and other methods that allow statistical inference are used to improve the scientific nature of sampling in response to the fact that online questionnaires are mostly used in non-probability sampling studies (Yu et al. 2019). Therefore, to ensure the randomness of the data, this questionnaire uses an algorithm to randomly assign survey links when distributing the questionnaire to ensure the breadth and representativeness of the invitation; in addition, the random distribution of questionnaire links through multiple channels (such as websites, forums, social media, emails, etc.) avoids an aggregation effect in a particular group of people, thus ensuring the randomness of the questionnaire and the quality of the data.

This survey revealed the fertility intentions of single, unmarried Chinese women of childbearing age in terms of “age”, “residence permit”, “education level”, “monthly income”, “annual net family income”, “health status”, and “only-child status”. We found that single, unmarried women aged 35–39 years had the highest FIs, but some studies have shown that the fertility rate of women gradually decreases from approximately 32 years of age and that fertility gradually decreases with age, with the fertility rate among women decreasing faster after 37 years of age (American College 2014; Vollenhoven and Hunt 2018), which is different from our findings. In addition, studies have shown that in recent decades, there has been a significant increase in the proportion of women delaying childbearing beyond the age of 35 years, a gradual decrease in the fertility rate, a shift in the age of childbearing and an increase in the proportion of middle-aged and older mothers (Balasch and Gratacós 2011). This also shows that with the development of assisted reproductive technology and the awareness of women of childbearing age, women are more empowered to decide whether to have a child (Upadhyay et al. 2014).

Furthermore, respondents residing in rural households exhibited higher fertility intentions, a finding corroborated by extant studies (Yang et al. 2023a). This phenomenon may be attributed to the cultural preference for sons in rural Chinese societies, where families often have more children to ensure the continuity of the male lineage (Jiang et al. 2016). In addition, this study showed that single, unmarried women of childbearing age with lower education and income levels have greater FIs, which is consistent with the findings of a study examining the relationship between women’s socioeconomic levels and FIs, where higher socioeconomic levels (e.g., higher education) were associated with lower FIs among Chinese women who had already given birth to one child (Zheng et al. 2016). Only-child status also affects FIs, with studies showing that having more siblings increases the intention to have more children, suggesting the importance of trust in the relationship with siblings and their fertility-related support in influencing FIs (Yang et al. 2023a).

The present study revealed that FAs significantly influence the FIs of single, unmarried women of childbearing age. FAs refer to an individual’s assessment of the degree to which he or she approves or disapproves of the act of childbearing, and an individual’s attitude towards the act of childbearing can have a significant effect on his or her motivation to perform the act. A study of the FIs of a young Chinese population in the context of the three-child policy revealed that women expressed high levels of anxiety about childbearing and childbirth, which influenced their decision to have children (Zhang et al. 2022a). In addition, the women’s fear of childbirth led them to doubt their fertility (Nilsson and Lundgren 2009). A study by the China Social Condition Survey (CSCS) revealed that the family concepts of young people in China are still more traditional, that there is no tendency towards individualistic family concepts, and that young people’s willingness to have children is still relatively strong; however, their willingness to have children does not effectively translate into reproductive behaviour, and inconsistencies in and behaviour towards childbearing are common among the urban youth group (Gong et al. 2023). These results contrast with the results of our study, which may be due to differences in socioeconomic status. Women’s attitudes towards childbearing have become more understood, as childbearing is not only for the sake of family succession but also related to a woman’s own choice and basic rights. However, in terms of the personal value of childbearing, few studies have explored the impact of different cultural or family value backgrounds on childbearing (Arpino and Tavares 2013; Shreffler et al. 2019), and there is a lack of research on the impact and significance of childbearing on personal values.

SNs are the social pressures that individuals face when making fertility decisions and are influenced by family, friends, colleagues and social opinion. Some studies have concluded that women’s FIs are influenced by their parents and other family members; for example, parents or in-laws may influence women’s fertility decisions or behaviour through emotional support or social pressure (Bernardi 2003; Zhang et al. 2022b), and a Chinese study showed that Chinese mothers with one child are more likely to plan for a second child if the grandparents’ preferences for the number or sex of their grandchildren are not met (Jin et al. 2018). The results of all these studies are similar to those of the present study. In addition, the present study highlights the influence of public opinion on FIs. A study on whether online public opinion on China’s “three-child policy” affects people’s FIs revealed that attitudes towards the “three-child policy” are more negative than those towards the “two-child policy”. The percentage of people with negative and neutral attitudes towards the three-child policy increased, and the percentage of those with positive attitudes decreased (Chen et al. 2023). This confirms that although the two-child policy was enacted in 2013, its impact on the fertility rate has not been favourable. According to the National Census, the number of births in 2015 was approximately 330,000 fewer than the number of births in 2014, a decrease of 2% (Liu and Zhang 2021; National Bureau of Statistics of China 2020). After the promulgation of the “three-child policy”, China’s negative population growth continued to worsen, which may indicate that public opinion and policies to encourage childbearing do not increase women’s willingness to have children. Therefore, more research is needed to determine what types of policies can further decrease negative population growth.

The results show that PBC also significantly affects the FIs of single, unmarried women of childbearing age; however, the effect of PBC on FIs is less strong. PBC refers to the degree of control that a woman feels over her fertility behaviour, such as ability, resources, and opportunities to carry out fertility behaviour. Some studies have shown that women’s fertility is influenced by many individual factors as well as external factors, of which socioeconomic factors have a greater weight; for example, 47.7% of Chinese women of childbearing age reported that economic barriers were the main obstacle to having a second child (Zhao et al. 2017). At the same time, some scholars have emphasized that health insurance is an important way of protecting individuals and the economy against the loss of the basic right to health care and that increasing the participation rate of migrant women in health insurance, especially maternity insurance, can help increase their willingness to have a second child (Liu et al. 2019; Xiong et al. 2022).

Social security also affects attitudes towards childbearing. Single women are discriminated against in the workplace and at a legal level, such as through the current ban on the use of all assisted reproductive technologies for single women under current Chinese law (Zhang et al. 2022c; Zhao and Fu 2023). Research suggests that to increase fertility effectively, China needs to create a more conducive environment for childbearing. This includes measures to remove barriers to employment for mothers and mitigate work–family conflict; in addition, expanding access to favourable fertility policies, particularly those that support pregnant women, is critical to increasing the desirability of reproduction (Qiao et al. 2024), which is consistent with the findings of this study. In addition, related research has indicated that governments can mitigate the financial and temporal demands associated with childbearing intentions by implementing childcare subsidies and enhancing family support services (Guo et al. 2025). Currently, women of childbearing age have a low overall desire to have children (Li et al. 2024). Although there are some influences from external policies and social security or resources, attitudes towards childbearing are negative regardless of the context, and better-targeted demographic incentives may be needed to improve China’s low fertility rate.

At present, the field of assisted human reproduction technology in China shows different attitudes towards the equal rights of frozen eggs and frozen sperm. In addition to the emphasis on nationality, voluntariness and health, the majority of egg donors are restricted to women who must be married, which inevitably excludes unmarried women, reflecting a kind of gender differentiation and making it impossible for women who want to be single but also want to have a child to realize the reproductive rights they should enjoy (Wu 2006). In addition, in 2003, the Chinese Ministry of Health issued a Circular on the Revision of Technical Specifications, Basic Standards and Ethical Principles for Assisted Human Reproductive Technology and Human Sperm Banks, which prohibits assisted human reproductive technology for single women, and if a woman wants to use the technology, she must have a marriage certificate, ID card and birth certificate, as well as a hukou (household registration) booklet and contact information for local family planning departments. Both the technology and the legal norms, etc., have limited the process of realizing the reproductive rights of single women, making the protection of the reproductive rights of single women face great difficulties (National Health Commission of China 2003). At the international level, Article 1 of the 1979 United Nations Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) explicitly states that ‘women, irrespective of their marital status, shall enjoy or exercise these human rights and fundamental freedoms on the basis of equality of men and women’, which means that single women are not excluded from using assisted reproductive techniques (ART) because of their status. In 1991, the United Kingdom adopted the Artificial Reproductive Technology Act (ARTA); in 2016, the Swedish Parliament passed a law allowing single women to use assisted reproductive technology; in addition, Belgium, Bulgaria, Denmark, Finland, Russia, Spain, India, Sweden, and other countries allow single women to give birth with the help of assisted reproductive technology (Yu 2021). With the revision and improvement of relevant laws in China, we believe that single women should no longer be turned away from the door of assisted reproduction technology, which will further satisfy the fertility desire of this part of the population and thus achieve the purpose of increasing the fertility rate.

The innovation of this study lies in the fact that single, unmarried women of childbearing age were taken as the research subjects, and the TPB model and structural equation modelling were used to construct a model of FIs, which was not performed in previous studies; on the other hand, this study also explored issues related to the reproductive rights of single women, and in light of the current fertility rate in China, we believe that more targeted population policies should be developed to alleviate the low fertility rate. In addition, this study has several limitations. This was a random sample survey. In China’s actual situation, the present sample was relatively small, and there may be geographical or other aspects of bias that affect the results of the study. Secondly, it should be noted that online surveys distributed randomly over the internet may not be fully representative of all single women in China. For example, women residing in rural areas or those with limited internet access may be underrepresented in the sample. In addition, this study investigated only the willingness to give birth and did not investigate actual reproductive behaviour, so the TPB model can be further deepened. Therefore, the TPB model can be further deepened, and the structural equation model of FIs can be analyzed by integrating different factors and in more detail. Finally, there is the discrepancy between intentions and actions: not all intentions result in the actual act of having children. Consequently, future research will need to employ longitudinal studies to track whether these explicit intentions to have children lead to childbearing. Moreover, qualitative studies will be required to explore the motivations behind these numbers.

5. Conclusions

This study revealed the FIs of single, unmarried Chinese women of childbearing age in terms of “age”, “residence permit”, “education level”, “monthly income”, “annual net family income” “health status”, and “only-child status”. In addition, the structural equation model showed that FAs (β1 = 0.301, p < 0.05), SNs (β2 = 0.295, p < 0.05), and PBC (β3 = 0.146, p < 0.05) all positively affect FIs. This study demonstrates that the decline in fertility in China in recent years has been partly influenced by changes in the fertility behaviour of single, unmarried women. This is due to the fact that single, unmarried women’s fertility intentions tend to decrease under certain socioeconomic conditions. This is further evidenced by the growth in the number of single women in the population. Therefore, to alleviate the current situation of the low fertility rate in China, society should pay more attention to the rights and interests of single and unmarried women, such as medical insurance and employment security, to provide good protection for them before and after childbearing and to provide a better social environment for childbearing. It is the contention of this study that the government should consider relaxing the fertility policy for single, unmarried women and formulate a targeted population policy to improve the low fertility rate in China. In addition to this, it is recommended that single women be permitted to have children through assisted reproduction, as this may be conducive to improving the current fertility environment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Z. and Y.B.; methodology, Y.Z. and Y.B.; formal analysis, Y.Z.; investigation, Y.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Z.; writing—review and editing, Y.B.; supervision, Y.B.; funding acquisition, Y.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by 3 research grants awarded to YB from the University of Macau (UM; MYRG2019-00044-ICMS, QRCM-IRG2022-001, and SKL-QRCM-IRG2023-032).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Our study did not require further ethics committee approval as it did not involve animal or human clinical trials and was not unethical. In accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki, all participants provided informed consent before participating in the study. Furthermore, according to the notice issued by the China Healthcare Commission, Article 32 states that the use of human information data or biological samples for life sciences and medical research involving humans may be exempt from ethical review under certain circumstances, provided it does not cause harm to individuals or involve sensitive personal information or commercial interests. The anonymity and confidentiality of the participants were guaranteed, and participation was completely voluntary.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The authors will provide relevant data upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TPB | Theory of Planned Behavior |

| FAs | Fertility Attitude |

| SNs | Subjective Norm |

| PBC | Perceived Behavioral Control |

References

- Ajzen, Icek. 2002. Perceived behavioural control, self-efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned behaviour. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 32: 665–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Gynecologic Practice and Practice Committee. 2014. Female age-related fertility decline. Committee opinion no. 589. Fertility and Sterility 101: 633–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arpino, Bruno, and Lara Patrício Tavares. 2013. Fertility and values in Italy and Spain: A look at regional differences within the European context. Population Review 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasch, Juan, and Eduard Gratacós. 2011. Delayed childbearing: Effects on fertility and the outcome of pregnancy. Fetal Diagnosis and Therapy 29: 263–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, Hans, and Christian Homburg. 1996. Applications of Structural Equation Modeling in Marketing and Consumer Research: A review. International Journal of Research in Marketing 13: 139–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardi, Laura. 2003. Channels of social influence on reproduction. Population Research and Policy Review 22: 427–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Ying. 2024. A Factors affecting urban youth’s reproductive behaviour in the context of low fertility: A study of 7312 young residents in urban area. Jianghan Academic 43: 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Tinggui, Peixin Hou, Xiaofen Wu, Jianjun Yang, and Guodong Cong. 2023. Changes of people’s fertility attitudes based on analysis of online public opinion on three-child policy in China. Biodemography and Social Biology 68: 166–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Shun, Mo-Lin Ma, and Meng-Ting Zhao. 2023. A Study on the Inconsistency between attitudes and behaviours of contemporary Chinese youth in childbearing. Journal of Chinese Youth Social Science 42: 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Xinghong, Mingze Ma, Yiyang Chen, Zhaoyang Fang, Jingru Liu, Shuming Yan, Yifei Feng, Xinya Cheng, Jian Wu, and Beizhu Ye. 2025. Prediction and unsupervised clustering of fertility intention among migrant workers based on machine learning: A cross-sectional survey from Henan, China. BMC Public Health 25: 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Quanbao, Ying Li, and Jesús J. Sánchez-Barricarte. 2016. Fertility Intention, Son Preference, and Second Childbirth: Survey Findings from Shaanxi Province of China. Social Indicators Research 125: 935–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, Yong-Ai, Meng-Han Zhao, and Jian Song. 2018. Parental influence on women’s second-birth plan in urban China. Population Research 42: 17–29. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Qin, Rui Yang, Zehong Zhou, Weiping Qian, Jian Zhang, Ze Wu, Lei Jin, Xueqing Wu, Cuilian Zhang, Beihong Zheng;, and et al. 2024. Fertility history and intentions of married women, China. Bull World Health Organ 102: 244–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Taoying, Long Zheng, Jianjiang Zhang, and Qiang Chen. 2023. Obstacles to Exercising Reproductive Rights for Single Women in China and Legal Recommendations. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy 16: 2125–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Jianghua, and Lianchao Zhang. 2021. Fertility intention-based birth forecasting in the context of China’s universal two-child policy: An algorithm and empirical study in Xi’an City. Journal of Biosocial Science 54: 516–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Jue, Min Liu, Shikun Zhang, Qiuyue Ma, and Qiaomei Wang. 2019. Intent to have a second child among Chinese women of childbearing age following China’s new universal two-child policy: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Sexual & Reproductive Health 46: 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Jongyan, and Hao Luo. 2013. Differences in Fertility Intention and Fertility Behaviour of Women Complying with the Two-Child Policy—An Empirical Study Based on the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Population Research 37: 84–93.2. Available online: https://www.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CJFD&dbname=CJFD2013&filename=RKYZ201301011&uniplatform=OVERSEA&v=W0zXm-VF2VLxE1mkVbNoLRFzpNNbQBCrQf36jonnaYc2RrfDiEe8J3uUhbokqdIV (accessed on 6 November 2024).

- Marois, Guillaume, Stuart Gietel-Basten, and Wolfgang Lutz. 2021. China’s low fertility may not hinder future prosperity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 118: e2108900118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Warren B., and David J. Pasta. 1995. How does childbearing affect fertility motivations and desires? Social Biology 3: 185–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. 2020. National Statistical Data on Annual Population Size and Birth Rate. Available online: http://Data.stats.gov.cn/adv.htm?m=advquery&cn=C01 (accessed on 6 November 2024).

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. 2023. China Population and Employment Statistics Yearbook 2023. Available online: https://www.stats.gov.cn/zs/tjwh/tjkw/tjzl/202302/t20230215_1908006.html (accessed on 6 November 2024).

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. 2024. National Data. Available online: https://data.stats.gov.cn/easyquery.htm?cn=C01 (accessed on 6 November 2024).

- National Development and Reform Commission. 2023. Data Overview: Population-Related Data for 2022. Available online: https://www.ndrc.gov.cn/fggz/fgzy/jjsjgl/202301/t20230131_1348088.html (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- National Health Commission of China. 2003. Circular on the Revision of Technical Specifications, Basic Standards and Ethical Principles for Assisted Human Reproductive Technology and Human Sperm Banks. Available online: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/wjw/gfxwj/201304/b2c02b9bf1fc427586fc3905c5c2df87.shtml (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Ni, Ping, Jingli Chen, and Na Liu. 2010. Sample size estimation for quantitative studies in nursing research. Chinese Journal of Nursing 45: 378–80. Available online: https://www.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CJFD&dbname=CJFD2010&filename=ZHHL201004044&uniplatform=OVERSEA&v=_mzYsfYfp2SxbIHgMl1Vyke1sD_n-sbxVa15nYgninVKBJgFJ8b-mmq7bmcNuWa2 (accessed on 5 December 2024).

- Nilsson, Christina, and Ingela Lundgren. 2009. Women’s lived experience of fear of childbirth. Midwifery 25: e1–e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, Yuting, Jiangli Di, Sidi Chen, and Huanqing Hu. 2024. Fertility Intentions Among Reproductive-Age Women—Three Provinces. China CDC Weekly 6: 778–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shreffler, Karina M., Stacy Tiemeyer, Julia McQuillan, Arthur L. Greil, and Tiffany Spierling. 2019. Partner congruence on fertility intentions and values: Implications for birth outcomes. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 36: 2307–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Jin-Han, and Yong-hong Xiao. 2024. Effects of fertility support on fertility intentions of married women of childbearing age under the three-child policy. Modern Preventive Medicine 51: 2982–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, Ushma D., Jessica D. Gipson, Mellissa Withers, Shayna Lewis, Erica J. Ciaraldi, Ashley Fraser, Megan J. Huchko, and Ndola Prata. 2014. Women’s empowerment and fertility: A review of the literature. Social Science & Medicine 115: 111–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollenhoven, Beverley, and Sarah Hunt. 2018. Ovarian ageing and the impact on female fertility. F1000Research 7: 1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- William, J. Doll, Weidong Xia, and Gholamreza Torkzadeh. 1994. A confirmatory factor analysis of the end-user computing satisfaction instrument. MIS Quarterly 18: 453–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Jie. 2006. Research on the Problem of Single Women’s Reproductive Rights. Science and Technology Information (Academic Edition) 2006: 24–25. Available online: https://www.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CJFD&dbname=CJFD2006&filename=KJXI200602012&uniplatform=OVERSEA&v=B9rT2xRzQPVEE6FTxn9Fn_qVsmJlbPdjY8Mm0nb4xpD91B08fspnOVCfnTpJO2aY (accessed on 9 October 2024).

- Xiong, Yan, Guojin Jiao, Jiaming Zheng, Jian Gao, Yaqing Xue, Buwei Tian, and Jingmin Cheng. 2022. Fertility intention and influencing factors for having a second child among floating women of childbearing age. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 9: 16531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Hanmo, Runlin Han, and Zhenjie Wang. 2023a. Third-child fertility intention and its socioeconomic factors among women aged 20–34 years in China. BMC Public Health 23: 821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Shucai, Quanbao Jiang, and Jesús J. Sánchez-Barricarte. 2022. China’s fertility change: An analysis with multiple measures. Population Health Metrics 20: 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Yu, Rongxin He, Ning Zhang, and Liming Li. 2023b. Second-Child Fertility Intentions among Urban Women in China: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20: 3744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yargawa, Judith, Kazuyo Machiyama, Victoria Ponce Hardy, Yeetey Enuameh, Edward Galiwango, Kassahun Gelaye, Kaiser Mahmud, Sanne M. Thysen, Damazo T. Kadengye, Vladimir Sergeevich Gordeev, and et al. 2021. Pregnancy intention data completeness, quality and utility in population-based surveys: EN-INDEPTH study. Population Health Metrics 19 S1: 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Fuqiang, Penghui Hu, and Shasha Du. 2019. Research on data quality control of online questionnaire survey. Statistics and Decision Making 35: 10–14. Available online: https://www.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CJFD&dbname=CJFDLAST2019&filename=TJJC201916003&uniplatform=OVERSEA&v=wbm3ez-uF5nfOFj4nDrGzMpLfsY2g0fKFZyRfHVT42DvhA1G3lS6qIptxSisFOug (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Yu, Jing. 2021. Exploring the Problem of Single Women’s Reproductive Rights. Journal of China University of Political Science and Law 2021: 25–36. Available online: https://www.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CJFD&dbname=CJFDLAST2021&filename=PZGZ202101003&uniplatform=OVERSEA&v=N7GyjowzUgBwKifCCMqnkyjowPF5f7r0ol2X3GZofB6oFZOHYkExxGg2cjEprUSP (accessed on 11 December 2024).

- Zeng, Yi, and Therese Hesketh. 2016. The effects of China’s universal two-child policy. Lancet 388: 1930–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Chenyun, Lingling Wei, Yinyan Zhu, Li Teng, Wenchang Zhang, Jia Xu, Mengqi Qin, Na Jiang, Haridah Alias, and Li Ping Wong. 2022a. Fertility intentions among young people in the era of China’s three-child policy. A national survey of university students. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 22: 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Jiakai, Lun Wei, Xiaoling Deng, Chao Luo, Qianmeng Zhu, Shucheng Lu, and Caiping Mao. 2022b. Current status and reflections on fertility preservation in China. Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics 39: 2835–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Lianchao, Jianghua Liu, and Virpi Lummaa. 2022c. Intention to have a second child, family support and actual fertility behaviour in current China: An evolutionary perspective. The American Journal of Human Biology 34: e23669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Jianlin, Nan Shan, Xiaochang Yang, Qin Li, Yinyin Xia, Hua Zhang, and Hongbo Qi. 2017. Effect of second child intent on delivery mode after Chinese two child policy implementation: A cross sectional and prospective observational study of nulliparous women in Chongqing. BMJ Open 7: e018823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Yue, and Huixian Fu. 2023. Social egg freezing for single women in China: Legal and ethical controversies. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy 16: 2379–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Yumei, Jingqin Yuan, Tan Xu, Mei Chen, Hui Liang, Donovan Connor, Yongqing Gao, Wenjie Sun, Nivedita Shankar, Chuanwen Lu, and et al. 2016. Socioeconomic status and fertility intentions among Chinese women with one child. Human Fertility 19: 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Zhenzhen. 2012. Fertility Intentions Under China’s Below—Replacement Fertility: Evidence from Jiangsu. Proceedings of Forum of Fertility Intention, Fertility Behaviour and Fertility Level, 12–31. Available online: https://www.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CYFD&dbname=CYFD2013&filename=N2012010058000076&uniplatform=OVERSEA&v=K9_J__EWHVTQeT7uiaf5WtdLC4K0fFU_kdc6aQj6CP4Ul3hVKH1QwDtb_Xukla4S-1EKOH0RCNw%3d (accessed on 6 October 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).