Abstract

Labor markets worldwide are increasingly strained by skill shortages, mismatches, and migration pressures, disrupting workforce stability and economic growth. This study conducts a comparative sectoral analysis in North Macedonia, Türkiye, Ethiopia, and Ukraine, focusing on the manufacturing, information and communication technology, and hospitality sectors, to examine the root causes and economic consequences of these challenges. Using a qualitatively driven mixed-methods approach, the research integrates expert interviews, surveys, and labor market data to assess skill gaps, workforce imbalances, and the role of migration. The findings reveal education–industry misalignment, inadequate vocational training, and low wages as persistent drivers of shortages. Additionally, the war in Ukraine, internal conflicts in Ethiopia, and refugee inflows in Türkiye amplify workforce instability, while North Macedonia faces severe emigration, particularly in the sectors of manufacturing and information and communication technologies. These insights are essential for policymakers, industry leaders, and educators in designing labor market interventions that foster workforce resilience. The study recommends national qualification reforms, industry–education collaboration, and improved wage structures to mitigate talent loss and strengthen labor market sustainability. By offering empirical evidence from diverse socio-economic contexts, this research contributes to global discussions on workforce development, migration economics, and labor policy reforms.

1. Introduction

Skill shortages and skill mismatches, accompanied by the potential economic threats from rising global migration, are some of the most complex and protruding issues in contemporary labor markets worldwide. These inter-related factors can rarely be observed independently. As Aluttis et al. (2014) point out, one of the key factors contributing to skill shortages and mismatches is globalization and the subsequent migration of skilled individuals from low- to high-income countries, which disrupts workforce distribution. Additionally, skill mismatches arise from a disconnect between the skills possessed by workers and those demanded by employers (Cappelli 2015), influenced by labor market characteristics that prioritize job-specific skills over general educational attainment (Desjardins and Rubenson 2011). Furthermore, the asymmetric global distribution of talent and varying national policies regarding skilled migration complicate the ability of countries to effectively utilize their human resources, leading to persistent skill gaps (Kerr et al. 2016). However, historical experience indicates that economies with rigid labor markets struggle more with unemployment and skill mismatches, thus highlighting the need for more flexible systems that can adapt to the continuously changing labor demands (Schioppa 1991). As there is an increased emphasis on the importance of workforce adaptability and lifelong learning (Tikkanen 2014; Lim et al. 2024; Radovan 2024), it is crucial to understand how such skill shortages and mismatches occur. This should, in turn, help in formulating efficient, sustainable, and inclusive labor market policies, especially in economies that struggle with these considerable challenges (Cedefop 2023; ILO 2021).

Against the global backdrop, this study examines how these labor market phenomena occur in four very distinct country contexts, namely in North Macedonia, Türkiye, Ukraine, and Ethiopia. Their selection was justified based on the variability in their individual socio-economic, geographic, and migration contexts. North Macedonia, Ukraine, Türkiye, and Ethiopia exhibit diverse economic structures and migration dynamics, making them critical case studies for examining the interplay of skill shortages, mismatches, and labor migration. As countries of origin for substantial migrant populations, North Macedonia and Türkiye face labor market pressures rooted in high unemployment, low wages, and even regional disparities, while Ukraine and Ethiopia struggle with economic instability and conflict (martial law)-driven workforce outflows, exacerbating the challenges of sustaining skilled labor and fostering inclusive economic growth. Consequently, this research offers unique insight into how skill shortages and mismatches influence, and are influenced by, migration patterns. While sector-specific factors can often be overlooked, this paper highlights the importance of such an approach, as it has been noted as being key to mapping labor market needs and educational outputs, as well as workforce mobility (McGuinness et al. 2017; World Bank 2021a).

Despite the global growth of the literature on this topic, much existing research has focused on developed countries, leaving gaps in our understanding of how skill shortages, mismatches, and threats of migration are manifested in countries such as North Macedonia, Türkiye, Ukraine, and Ethiopia. To fill this gap, the study was designed to be qualitative and comparative. A combination of primary and secondary data was used to study the problem at hand. Statistical data for the last decade were obtained from national and international databases to understand the skill shortages and mismatches of each country’s individual labor market, as well as their domestic education and emigration. The findings are supported by a qualitative content analysis of primary data obtained through standardized, open-ended question-based interviews with key stakeholders, i.e., companies, higher education institutions (HEIs) and vocational education and training (VET) institutions, policy creators in the domain of education and the labor market, labor market intermediaries, and social partners. This approach was conducted with at least 40 participants from each country.

The aims of this study are threefold. First, we systematically assess the prevalence and characteristics of skill shortages across the manufacturing, information and communication technology (ICT), and hospitality sectors in the four countries, providing significant novelty to the global academic nexus. Second, the paper aims to analyze the extent to which migration (namely emigration) shapes labor market imbalances. Third, the study provides targeted policy recommendations based on strengthening qualification frameworks, enhancing industry–education collaboration, addressing wage and labor standards to retain local talent, and leveraging migration to mitigate the adverse effects of these labor market phenomena. The study was designed to provide insights and findings in relation to three predominant research questions: (1) What are the sector-specific skill shortages and mismatches in the four countries? (2) How do different forms of migration increase or decrease those shortages and mismatches? (3) Which policy instruments hold the greatest promise for closing the widening labor market gaps emerging through inadequate education and pronounced migration?

The findings point out significant skill mismatches, labor shortages, and migration challenges in the four countries. North Macedonia struggles with emigration and a misalignment between education and labor market needs, and would benefit from modernized curricula, public–private collaboration, and return migration incentives. Ukraine, amid war and economic instability, shows emerging positive trends in workforce adaptation, emphasizing the need for it to align its qualification framework with European Union (EU) standards and improve adult education. In Türkiye, skill mismatches, brain drain, and inadequate on-the-job training require sustainable VET models and better integration of education with sector demands. Ethiopia witnesses skill shortages at higher levels, with graduates lacking the requisite competencies to take over the jobs that the labor market provides. Conversely, local markets also fail to provide decent jobs that could retain skilled workers.

This paper is structured as follows. Section 2 elaborates on the conceptual theoretical framework of the conducted study by focusing on shortages, mismatches, threats of migration, and the theoretical and empirical findings of related studies. In Section 3, we provide a detailed overview of the methodology employed. We present the data sources and the comparative design of the study, as well as the usage of case-specific methods for Ukraine. In Section 4, we conduct a sectoral approach, whereby the manufacturing, ICT, and hospitality sectors are investigated in detail. Section 5 is reserved for cross-country comparative analysis and policy recommendations, respectively. The paper discusses investments in skill development, migrant skill recognition, and sector-specific initiatives. Finally, Section 6 concludes the research by summarizing the findings and outlining the future research agenda, emphasizing the need for continued study at the intersection of skill development and migration in order to foster more resilient and equitable labor markets.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Skill Shortage

Skill shortages arise when the demand for skills within the labor market exceeds the available supply of workers who possess those skills. This can be a consequence of several factors, including rapid technological advancements, evolving industry needs, and demographic shifts (OECD 2023). The concept of skill shortages is inherently dynamic, as highlighted by the European Training Foundation (2017), emphasizing that these shortages are not static, but change with economic and technological developments. A key aspect of skill shortages is their link to wage dynamics. As Duszczyk and Kaczmarczyk (2022) find in their study on migration from Ukraine to Poland, when labor markets face shortages in specific skill sets, it often results in upward pressure on wages for those skills, as also suggested by the findings of the State Employment Service (2024) on registered labor demand in Ukraine. A similar case has been confirmed for German establishments, as per Kölling (2022). This dynamic can be further complicated by global trends such as migration, where the movement of skilled labor across borders can either alleviate or exacerbate shortages in both origin and destination countries (European Training Foundation 2021). For example, Gulek (2024) provides an example of this occurring in the Türkiye labor market after it accepted refugees in the last decade, suggesting that this slowed down salary increases at the time. Understanding the nature and implications of skill shortages is essential in order for policymakers to devise effective strategies for education, training, and labor market interventions. The European Commission (2024) similarly suggested, in its report about Türkiye, that the effects of such dynamics and other aspects related to the labor market must also be considered and inspected regularly to be able to develop policies further.

2.2. Skill Mismatch

Skill mismatches, which can be either vertical or horizontal, occur when there is a discrepancy between the skills possessed by individuals and those required by the jobs available on the market. Vertical mismatch occurs when workers are either overeducated or undereducated for their jobs, while horizontal mismatch occurs when the type of education or skills do not align with job requirements, even if the education level is appropriate (Ege and Erdil 2023). This phenomenon is present in all four corners of the world. It is more visible and less easy to eliminate in developing countries; for example, a study conducted by the Ministry of Commerce (2024) indicates that despite the measures taken in previous years, the negative effects of skill mismatches are still highly visible in Türkiye. However, skill mismatches also affect developed countries like the European Union (EU) and its member states. The recent publication “Commission Staff Working Document for Ukraine” (European Commission 2024) indicates the need to address this phenomenon as well. As indicated in the North Macedonian report published by the European Training Foundation, one of the main issues leading to these high levels of mismatch is pressure stemming from structural unemployment and poverty (European Training Foundation 2017). As in the case of North Macedonia, a significant share of Türkiye’s workforce is in informal employment (OECD 2023), which exacerbates this mismatch. The high presence of informality prevents efficient adjustments and policies for formal employment. Thus, informality is considered one of the major causes of skill mismatches (European Union 2024).

This phenomenon is not limited to developing economies; it is a global issue that affects labor markets worldwide (ILO 2023). The consequences of skill mismatches are far-reaching, impacting not only individual career prospects and job satisfaction, but also firm productivity and overall economic growth (Mojsoska-Blazevski 2017). Research indicates that skill mismatches can lead to inefficiencies in the labor market, reduced job satisfaction, and increased turnover rates as individuals seek positions that better match their skills and qualifications. A study conducted by Onozuka (2022) highlights that mismatches tend to produce wage heterogeneities, with workers in jobs that are unrelated to their major field of study earning significantly lower wages than those in field-related jobs. Moreover, skill mismatch can impede innovation and the adoption of new technologies (European Commission 2024), highlighting the critical need for educational and training systems to be responsive to the evolving demands of the labor market.

2.3. Threats of Migration

Migration, particularly the emigration of skilled workers, presents a complex set of challenges and opportunities for both the origin and destination countries. The movement of skilled workers, often referred to as “brain drain”, can lead to significant skill shortages in the home country (DİSK 2019), affecting various sectors, including healthcare, education, and technology. This emigration is driven by a multitude of factors, such as higher wages, better living conditions, and more advanced professional opportunities abroad (Türkstat 2024). Conversely, destination countries often benefit from an influx of skilled labor, which can contribute to economic growth and innovation. However, this can also lead to increased competition for jobs and potentially depress wages for native-born workers with similar skill levels. Additionally, migration can influence demographic changes, social integration, and cultural diversity in both origin and destination countries. For example, the huge influx of war refugees into Poland has led to significant demographic shifts, which must be considered when making long-term plans (Duszczyk and Kaczmarczyk 2022). The challenge of managing immigration from different origins to preserve social integrity while helping those in need highlights the importance of this discussion (Pham et al. 2023). As a final remark on the issue of threats of migration, there are other examples of how certain migration agreements can fail due to economic or social reasons, such as that observed in the case of the short-term effects of Syrian refugees on the Türkiye labor market, and how an influx of migrants can influence these factors (Gulek 2024).

Even though the comparative design of our study is founded on four countries that are considered origins of migration, several distinct characteristics are notable that contribute towards a greater risk of human capital depletion. For instance, even though North Macedonia has struggled with emigration historically, this trend has increased since 2018, affecting nearly all levels of educational attainment. Notably, brain drain remains a critical issue for North Macedonia. It is estimated that annually 2500 highly educated individuals emigrated from the country between 2013 and 2021, for which the country invested approximately 5 billion MKD (81.3 million EUR) on average every year (State Audit Office of the Republic of North Macedonia 2024). Moreover, the cost of brain drain of highly educated personnel from North Macedonia is estimated at 0.8% of GDP annually, and the loss of GDP due to emigration is estimated to be between 5.15% and 8.34% of the nominal GDP each year.

On the other hand, Türkiye can be considered both a country of origin and a country of destination for labor migration. Currently, Türkiye is reported to host 3,9 million migrants and refugees, 90% of whom are Syrians, who are subject to temporary protection regulations (IOM Türkiye 2025). There has also been an increase in the rate of migration from Türkiye. According to TURKSTAT (2023), the number of people migrating from Türkiye in 2023 increased by 53% compared to the previous year, and reached 714,579. Most of those who migrate abroad from Türkiye are qualified laborers, which leads to brain drain and employment gaps.

In Ukraine, the context is rather different. The war has had a significant impact on the processes of labor migration, both within the country and beyond. Between 2022 and 2024, the number of Ukrainians who moved abroad to EU countries (Poland, Germany, the Czech Republic, Italy, Spain, etc.) increased sharply. A certain share of citizens emigrated to the aggressor country for various reasons. Many EU countries have adopted special programs to support Ukrainian refugees, facilitating access to the labor market. Challenges such as the uncertainty of war, the narrowing of employment, structural and qualitative changes, forced migration, and large-scale mobilization movements have deepened employment problems.

Finally, higher education in Ethiopia is closely linked to increased migration for better economic opportunities (Schewel and Fransen 2018). Skill mismatches, more so than socio-economic or political factors, drive emigration. Over 40% of university graduates struggle to find relevant jobs, prompting both skilled and unskilled workers to migrate, primarily to Northern European countries, the Middle East, and Africa. In Africa’s second-most-populous nation, with 54% of the population of working age, but 19% unemployed, internal displacement, rural–urban migration, and outward flows to Europe create chronic shortages of advanced technical and digital skills. The case of Ethiopia represents a low-income, high-growth context where demographic pressure meets limited job creation—a fundamentally different context to the other three cases.

2.4. Theoretical and Empirical Findings

The study of labor migration, skill shortages, and mismatches has yielded a rich body of theoretical and empirical research. Theoretical models often draw upon human capital theory, which posits that education and training are investments that enhance an individual’s productivity and, consequently, their earning potential (Gulek 2024). Empirical studies provide evidence of a “brain drain” from less-developed to more-developed regions, driven by the search for better economic opportunities and higher returns on human capital investments (Pham et al. 2023). This phenomenon can significantly impact the availability of skilled workers in the labor market, especially in the case of developing countries. It has been observed that brain drain can hinder economic growth and innovation in the countries of origin (Marchiori et al. 2013), and since it diminishes the human capital in these countries, it can reflect negatively on the adoption of technological advancements, which is key to economic competitiveness. Simultaneously, labor market gaps are created that are difficult to fill, especially in specialized sectors (Ghazali et al. 2015). As per Chen et al. (2024), it is often considered that weak institutional capacities and inadequate policies in developing countries, which we also seem to observe in our cases, contribute to brain drain by failing to prevent the outflow of domestic talent. Moreover, education policies that are aimed at increasing the skill level of the national workforce are less effective (Pires 2015), as the benefits of such policies are often lost when qualified individuals emigrate.

Research also indicates that migrants often face challenges in the recognition of their qualifications and skills in the destination country, which can lead to occupational downgrading and underutilization of their human capital (Gökbayrak and Çalışır 2024; Hrynkevych et al. 2023). By employing various economic models and detailed statistical analyses, researchers aim to quantify the impacts of migration on wages, employment levels, and economic growth. For instance, studies have analyzed the effects of migration on labor market outcomes, such as with regard to the influx of Syrian refugees in Türkiye (Gulek 2024) and the challenges faced by workers in adapting to new environments (Kavak 2023).

Global mobility trends are shaped by a confluence of factors, including conflicts, economic disparities, demographic changes, and policy environments. The ongoing conflict in Ukraine, for instance, has led to significant displacement, with millions fleeing to neighboring countries and beyond (Duszczyk and Kaczmarczyk 2022; ILO 2022). Global mobility trends reflect the dynamic interplay between economic opportunities, social factors, and policy frameworks. The movement of people across borders is influenced by the search for better employment prospects, higher wages, and improved living conditions (ILO 2023). Technological advancements and the rise of digital platforms have also facilitated mobility, enabling individuals to seek opportunities beyond their immediate geographical confines. The European Training Foundation (2017) highlights that significant migration flows are driven by both push factors in countries of origin, such as political instability, economic hardship, and lack of opportunities, and pull factors in destination countries, including demand for specific skills and better living standards.

Regional contexts significantly influence migration patterns and the integration of migrants into labor markets. For example, the Western Balkans have experienced substantial emigration, driven by factors such as high unemployment, low wages, and political instability (OECD 2022). The European Commission’s report on Ukraine (European Commission 2024) emphasize the impact of regional conflicts and economic conditions on migration flows. Deimantas and Şanlıtürk (2023) highlight the challenges faced by Ukrainian refugees in Lithuania, particularly in terms of language barriers and recognition of qualifications. Similarly, studies by the State Audit Office of the Republic of North Macedonia (2024) and TEPAV (2023) underscore the importance of addressing regional disparities and enhancing the capacities of local institutions to manage migration effectively. Crucially, North Macedonia, Ukraine, Türkiye, and Ethiopia, to a certain degree, have aligned their national qualifications frameworks with the European Qualifications Framework (EQF). Besides the notable aspirations of the first three countries for EU integration and alignment with the European labor market, this is essential for labor migration. After all, it facilitates the recognition of domestic credentials abroad and, symmetrically, return migration, because it eases individuals’ reintegration into domestic labor markets after acquiring skills and qualifications abroad.

The complex interplay between labor migration, human capital, and labor market outcomes necessitates a multifaceted approach to policy interventions. The findings from various studies and reports underscore several key themes:

Education and Skill Mismatch: The mismatch between the skills acquired by workers and those demanded by the labor market remains a significant challenge. Efforts to align educational curricula with labor market needs are crucial for reducing this gap. This includes promoting vocational education and training (VET) programs that are responsive to industry demands and ensuring that workers have opportunities to upskill and re-skill throughout their careers.

Impact of Conflict and Displacement: Conflicts and displacement, such as the wars in Ukraine and Ethiopia, have profound effects on migration patterns and labor markets. These events necessitate both immediate humanitarian responses and long-term strategies for integrating displaced populations into host labor markets. The integration challenges are multifaceted, involving issues of language, recognition of qualifications, and social cohesion.

Policy Coherence and Institutional Capacity: Effective migration management requires coherent policies that address the various dimensions of migration, including labor market integration, social inclusion, and protection of migrants’ rights. Strengthening institutional capacities, particularly in regions with high emigration rates, is essential for implementing these policies effectively.

Role of Diaspora and Remittances: Diasporas can play a significant role in the economic development of their countries of origin through remittances, investments, and knowledge transfer. Policies that facilitate diaspora engagement and promote their contributions can enhance development outcomes.

Data and Research: Further research is needed to understand the dynamics of migration and its impacts on both origin and destination countries. This includes longitudinal studies on the outcomes of migration for individuals and communities, as well as analyses of the effectiveness of different policy interventions.

Addressing the challenges posed by migration requires a comprehensive approach that considers the interplay between education, labor markets, and migration policies. By fostering an environment that supports the development of human capital, facilitates the integration of migrants, and promotes inclusive growth, countries can better manage migration flows and harness their potential for economic and social development.

So far, studies have rarely merged skill shortages, mismatches, and migration all together and looked at how these phenomena interact in the context of low- and middle-income countries as the origin of migration (McGuinness et al. 2018). Comparative studies that do look at this nexus still focus on OECD members, even though emerging evidence shows that the simultaneity of shortages, mismatches, and emigration can suppress productivity growth by as much as one percentage point a year in non-EU transition states (Cedefop 2015; World Bank 2021b). This being the case, there is a growing need for a multi-country exploration that can provide insights into the different contexts and mechanisms that form mismatches, shortages, and overall labor migration.

Our study adopts a comparative case approach that integrates countries that vary in terms of their demographic, income level, conflict exposure, and even the characteristics of their migration flows. Combining stakeholder interviews with secondary labor market microdata allows us to capture a firm-level labor environment that is invisible in official statistics, but can be decisive for policy design (Korstjens and Moser 2017). Qualitative content analysis embedded in a mixed-methods framework (Creswell and Plano Clark 2018) has repeatedly been shown to outperform purely quantitative diagnostics when institutional data are characterized by having low quality or high measurement error, as is the case in our four country cases (Bartlett and Vavrus 2017). By pairing this methodology with a sectoral approach that compares capital-, skill-, and labor-intensive industries, the study can isolate specific factors, contexts, and policy responses to skill mismatches and shortages. Subsequently, the following methodological approach is justified in cases such as these, where rich microdata is unavailable and conventional methodologies cannot be applied.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Framework and Research Design

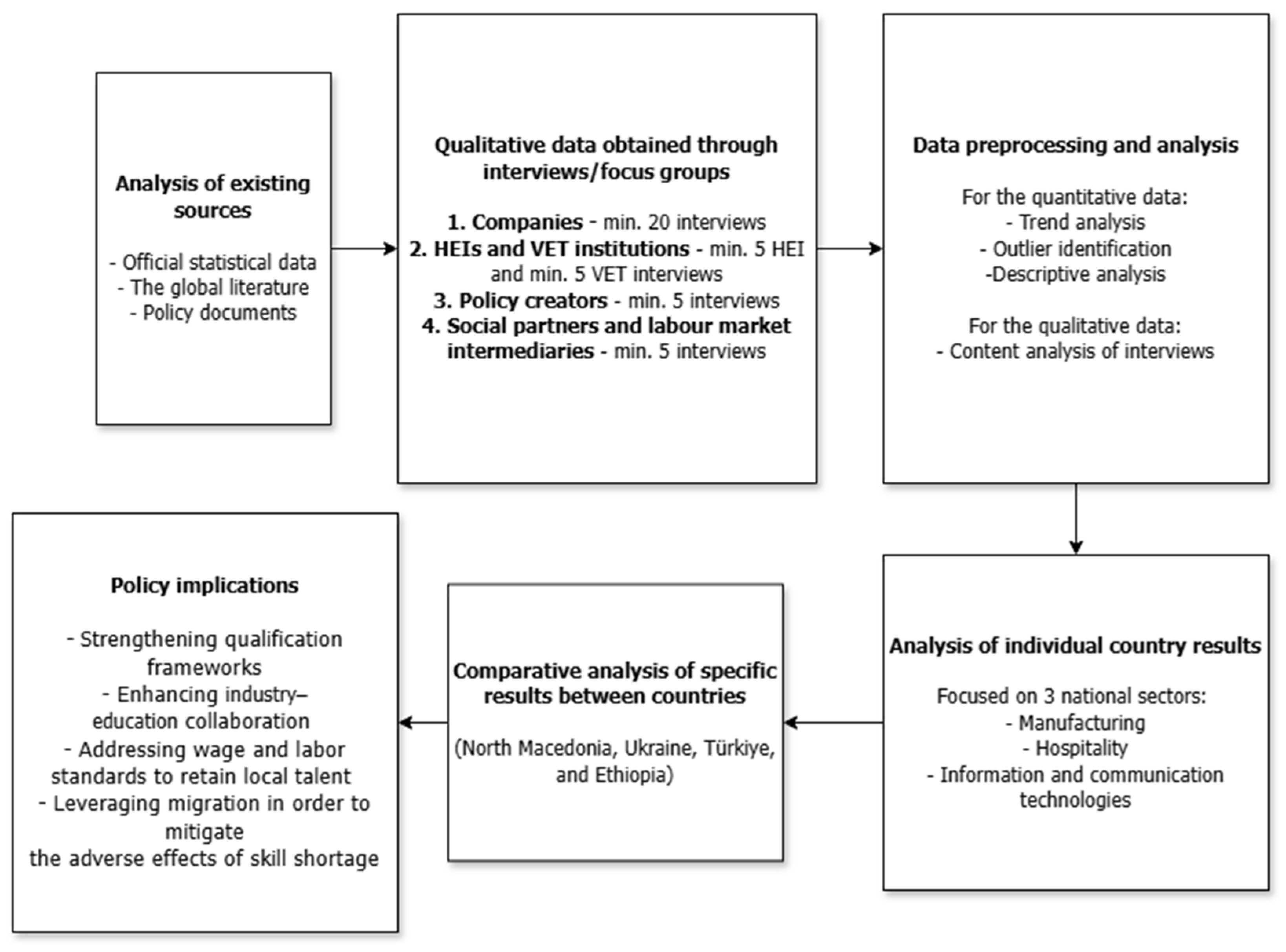

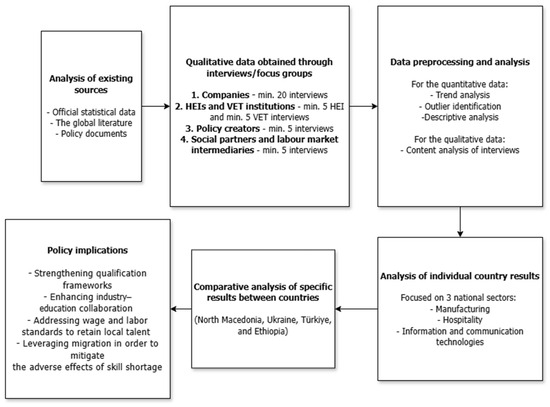

Researchers from North Macedonia, Türkiye, Ethiopia, and Ukraine carried out the methodology of the study in 4 blocks of tasks, including the following: (1) preparation of the methodology and research tools; (2) analysis of available official statistical data and specialized publications; (3) conducting interviews and focus groups with stakeholders on changes in the demand and supply of qualified labor in the national economy; and (4) analysis of the data obtained and preparation of a comparative study. For this purpose, a dual methodological approach was utilized, involving descriptive and trend analysis of secondary data obtained through international and national statistical databases, and by conducting an open-ended question-based interview with companies, educational institutions (HEIs and VET institutions), policy creators, and labor market intermediaries, while focusing on the manufacturing, hospitality, and information and communication technology sectors. The study considered a sample of respondents (namely companies) who were selected to create a heterogeneous group based on their size, their sectoral importance, and the importance of their provided products or services to the national economy, while taking into consideration the regional distribution across the four countries. Subsequently, the study employed a maximum variation sampling strategy (Patton 2015) to capture the diversity in firm sizes and ownership forms within each economy. This approach is widely recommended in comparative labor market studies, because it allows heterogeneous patterns, while still retaining contextual saturation with relevant information. The minimum number for the total respondents of all segments was set to 40. This was conducted ex ante to ensure a small but analyzable sample for each country–sector stratum, thus satisfying the cross-case recommendations of Yin (2018) for multiple-case designs. The design of the methodological approach is visually portrayed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The workflow of the methodological approach.

3.2. Procedure and Data Collection

Several general approaches and criteria were methodologically defined for conducting the interviews with companies’ representatives. These included that the duration of interviews conducted through a face-to-face approach or with a focus group should not exceed 1 hour, and that the online questionnaire should be presented in English or the national language. Online distribution was conducted only in cases where physical contact could not be established, and was designed to help Ukrainian companies participate in the study. The content of the research questionnaires was designed to fully comply with common ethical standards, with permission to conduct the survey and protection of personal data considered the most important factors. In this regard, the subsequent content analysis of qualitative results does not allude to any of the respondents, and commonly refers to each participant just as a “respondent”. Notably, each country could add country-specific questions in addition to the mandatory set of questions, with their number being limited to a maximum of 25% of the mandatory set.

To study opinions on the matching of qualifications to the needs of the labor market, a standard questionnaire was used, consisting of 21 profile questions grouped into 5 thematic blocks. To study the opinions of representatives of educational service providers, a standard questionnaire was used, consisting of 25 thematic questions grouped into 8 thematic blocks. The criteria for selecting respondents for higher education institutions were different types of universities (classical, national, state, municipal or private, etc.); regional location/representation and/or the presence of separate structural units; the availability of a large number of areas of training, particularly, specialties significant for the entire country; and the respondent’s affiliation to positions no higher than the faculty. For vocational education and training institutions, the criteria were training in multidisciplinary and consolidated qualifications; training of workers for the service sector and types of economic activity in the region of location; absence of reputational risks; and recognition among users and consumers of specialized educational services. The interviews of policy providers (at the national and regional levels) in the field of employment and labor market policy and in the field of education and training covered a wide range of state and regional policies in the fields of education, employment, the labor market, education and training, labor and forced migration, and interaction with stakeholders at different levels of government. The core questionnaire consisted of 13 questions across 6 thematic blocks for the first group, while for the second group of respondents, the total number of questions was 15, across 6 segments.

3.3. Country-Specific Adjustments

It should be noted that each country included in the study, primarily North Macedonia and Türkiye, applied specific national variations, in addition to typical methodological approaches. For Ethiopia, the results were presented under three main categories: findings from companies, HEIs and TVET colleges, and policy providers and social intermediaries. It was more difficult for the researchers from Ukraine to adhere to typical methodological approaches. This is because virtually all spheres of the country’s socio-economic life have 2 periods of development: before 2022 and during the active war. Indicators, trends, strategies, and plans before the war have, in many cases, lost their relevance. The decline in gross domestic product, jobs, employment rate, and the standard of living of the population during the war has fallen from a third to half.

Ukrainian researchers analyzed statistical and bibliographic data from early 2022 to mid-2024, while occasionally incorporating pre-2022 comparisons for employment and educational indicators. Notable labor shortages or surpluses in the aforementioned sectors were identified using a proprietary methodology (based on current data from the State Employment Service of Ukraine) that calculates the ratio of supply and demand for qualified personnel by profession. The researchers also adapted four standard questionnaires to Ukraine’s wartime context, expanding them by about 20–25% of the total number of questions to address issues such as the impact of conflict on training, forced displacement, digitalization of workplaces, and the use of female labor in difficult work conditions.

Our approaches to comparing the results of the studies in the 4 countries and compiling them into a single research thematically observe several aspects. First, we summarize and compare the lists and descriptions of publications on the labor market, the market of educational services, qualifications, and migration, which were formed by selecting the most significant published materials for each country, according to their international recognition and use. Published results of comprehensive studies dedicated to migration processes and problems with their regulation in the country of departure and countries of arrival of migrants of different categories are described separately. When selecting publications, preference was given to those published in English, although national documents of key importance were also considered. Second, the analysis of key indicators and the results of statistical and other studies on the development of qualifications, their application, shortages or surpluses, outflow of skilled labor outside the countries of origin, etc., were interpreted by firstly comparing comparable values by demonstrating extreme values, dynamic series, and lists of trends of interstate similarity or, conversely, differences; and secondly, compiling a separate description of the key characteristics of countries where there are specific factors of influence, for example, Ukraine and Ethiopia. Third, based on the answers to the interviews of key stakeholders from the 4 countries, content analysis, and careful systematization and analysis of the answers, conclusions were formed on the topic of the study based on similar questions, and similarities or differences in the responses of stakeholders were determined. Additionally, the results of interviews with experts on problems specific to a particular country are highlighted as examples.

The methodological approach was conducted in two linked steps. In the first step, secondary labor market data sourced from national and international databases were used as a scoping device to indicate the sectors deemed the most significant to the national economy, and the presence of skill mismatches or shortages, thus identifying that the ICT, manufacturing, and hospitality sectors are mutually important for the four countries. Next, in the second step, interview transcripts and open-ended questionnaire responses were read repeatedly by two researchers per country, who used manual, line-by-line coding and constant comparison to surface recurring concepts (Braun and Clarke 2006). Coded pieces were then sorted into themes based on the questions at hand, discussed in several team debriefings, and refined until a final version was built. A simple Excel matrix listed themes (represented by the questions in the survey segmented in rows) against stakeholder groups (in columns), allowing for a transparent cross-case comparison of convergent and divergent findings (Miles et al. 2014).

3.4. Respondent Distribution Across Countries and Sectors

The final sample studied per country was as follows. In North Macedonia, 29 companies’ representatives were interviewed across five main sectors: manufacturing (10); electricity, gas, steam, and air conditioning supply (2); financial services (6); information and communication technologies (7); and accommodation and food services, i.e., the hospitality sector (4). Consequently, the three sectors at the focal point of this accounted for 75% of all the companies studied. Regarding the education institutions, a total number of 6 HEIs and 4 VET institutions were interviewed. On the other hand, we interviewed 5 core respondents from each of the remaining two target groups, i.e., policy creators and labor market intermediaries, and social partner organizations.

In Türkiye, 37 interviews were conducted in total. Based on the sectors with labor shortages in the last five years, as indicated by İŞKUR, a total of 19 company managers were interviewed, from sectors such as furniture (1), welding (1), textiles (2), footwear (1), administrative and support services (private security, 5), accommodation and food services (hotel, 1), education (3), and software (5). Regarding the educational institutions category, interviews were conducted with 15 educational institution administrators working at secondary education, higher education, and vocational education centers. Finally, in the policymaker category, three participants from national and regional policy providers and social partners contributed to the research.

In Ukraine, 22 representatives of companies in five main sectors were interviewed: manufacturing (12); information and communication technologies (5); electricity, gas, steam, and air conditioning supply (3); and financial services (2). Thus, the two sectors that are in the spotlight and most characteristic of the country account for 77.2% of all companies surveyed. Regarding educational institutions, it should be noted that a total of 12 providers of educational services were interviewed, of which 6 represented universities, and 6 represented vocational colleges and vocational schools. Seven lead respondents from each of the two target groups were also interviewed, i.e., policymakers, labor market intermediaries, and social partner organizations. In addition, 35 stakeholders were additionally interviewed in Ukraine from among employees and workers of enterprises, institutions, institutions, and organizations of various types of economic activity that use digital devices, technologies, and communication tools in their work. People responsible for adult education, including in-service training, were covered, as well as those dedicated to the role of digitalization in changing learning in extreme (pandemic, war) conditions.

Similarly, in Ethiopia, 20 companies were included in the study across key economic sectors: manufacturing industries (10), construction industries (2), and service sectors (8) including financial sectors, Telecom, health, education, and hospitality. Regarding the training providers, a total of 5 HEIs and 6 VET institutions were included in the study. In addition, we collected data from 9 key informants drawn from policymakers, labor market intermediaries, and social partners.

4. Results

4.1. Manufacturing Sector

4.1.1. The Importance of the Manufacturing Sector and Ukraine’s Case Under Martial Law

Since the full-scale war began in 2022, Ukraine’s manufacturing sector has faced severe disruptions. Despite a slight economic revival in 2023, challenges persist, particularly a mismatch between worker qualifications and employer needs. War-related uncertainties, migration, and mobilization have further narrowed employment opportunities, deepening labor market structural shifts. Many enterprises have adapted by shifting from civilian to military or strategically critical production, driving demand for specialized skills in defense, logistics, IT, and energy. Employers are increasingly adopting innovative technologies and automation, requiring workforce upskilling to enhance competitiveness. However, despite an overall labor surplus, industries struggle to fill vacancies due to skill mismatches. Statistically, the sector has experienced a notable contraction in job openings in recent years. From 2020 to 2023, the State Employment Service recorded a 60.3% drop in overall registered vacancies (from 829,653 to 329,436) in Ukraine, with the manufacturing sector alone losing 85,000 vacancies during this period. This significant reduction was most pronounced in the food industry (by 21,638 vacancies), in the production of other non-metallic mineral products (by 8790 vacancies), and in the wood processing industry (by 6245 vacancies). The most affected subsectors include the food industry, non-metallic mineral production, and wood processing. By 2023, only about 40.4% of the manufacturing vacancies present in 2020 remained. Concurrently, the relocation of businesses and people to safer regions has led to an uneven distribution of jobs, altering the demand structure for various skills and professions. For example, the number of vacancies in the occupational group “Workers for the maintenance, operation, and monitoring of the operation of process equipment, assembly of equipment and machines” in 2023 was 18.4% of the total number of vacancies, a decrease compared to its peak value of 24.9% in 2022.

The Macedonian labor market is facing the dual challenges high unemployment and significant labor and skill shortages, which are continuously emphasized. One of the main drivers of the national economy is the manufacturing sector; however, significant challenges persist. For instance, the National Employment Strategy (Ministry of Labour and Social Policy 2021) highlights a clear wage gap in manufacturing, where women are predominantly employed (especially in textile production), contributing to gender discrepancies. Also, based on data from the Employment Service Agency (2023), 45.6% of employers were expected to create 14,915 new jobs within the following 12 months, with large employers (250 or more employees) accounting for 43.1%, and the manufacturing sector was expected to contribute the largest proportion of new jobs (51.2% in total). Full-time employment was pronounced, with almost 99% of all employees in this sector. Related to skills and occupation demand, employers emphasized the demand for workers with primary and secondary education, particularly in the manufacturing and retail sectors. For example, 45.5% of new jobs in manufacturing were expected to require primary education, while 44.5% required secondary education. This demand was notably pronounced for general laborers, machine operators, and tailors. Discrepancies in the Macedonian manufacturing sector have existed for years, where, until 2017, a lower statutory minimum wage was employed compared to other sectors.

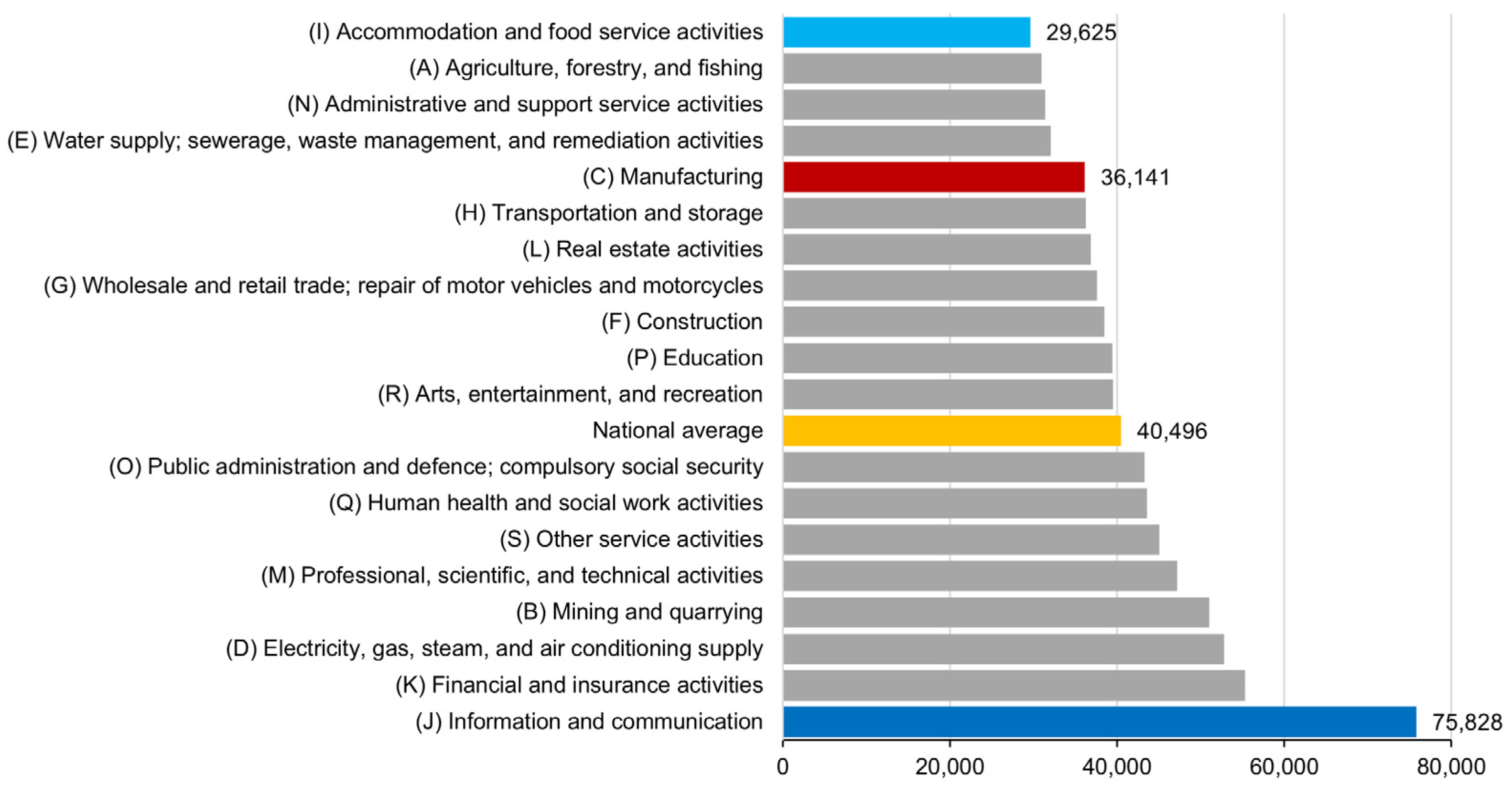

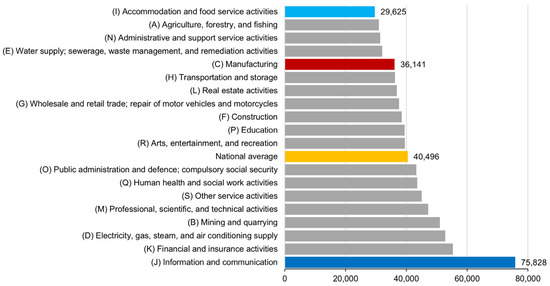

Based on data from the State Statistical Office, men tend to experience longer duration spent unemployed, which should, in turn, be significantly reflected in industries requiring specific skills, such as manufacturing. Moreover, with an average wage of MKD 20,911.2 (approximately EUR 340), the manufacturing sector in North Macedonia is consistently among the lower-paid sectors, well below the national average. When designing this study, it was also interesting to observe how the hospitality and the ICT sectors rank on this scale, and to understand the combination of both top and bottom earners, as shown in Figure 2. In turn, employees in such sectors tend to be the top candidates for the emphasized emigration in the country. Nevertheless, the manufacturing sector contributes roughly 25% of the total occupied jobs, which highlights its importance to the national economy. On the contrary, with roughly 30% of total job vacancies on average (1.89% job vacancies), the manufacturing sector remains the most significant in this segment, with plant and machine operators and assemblers being among the top vacant positions.

Figure 2.

Average net wage paid by sectors of activity in North Macedonia, in Macedonian Denars.

4.1.2. Labor Migration and Its Impact on Manufacturing—Why Does Türkiye Stand Out?

Migration continues to both exacerbate and mitigate sectoral challenges. Highly qualified workers fleeing abroad create workforce shortages in crucial industries, while internal displacement saturates job markets in safer regions, intensifying the need for robust vocational training. As a result, there is strong demand in manufacturing, particularly in clothing production. Yet, factors such as insufficient pay, declining job prestige among youth, and disrupted production lines due to the war have worsened the skills gap. In the qualitative study conducted, roughly 38.5% of participating companies blamed labor shortages on the forced relocation of workers, which highlights the crucial role of conflict-induced migration in reshaping Ukraine’s manufacturing labor market.

Migration is one of the key drivers of Türkiye’s labor market discrepancies. Characterized by significant emigration, leading to brain drain (estimated at 4.4% in manufacturing and construction) and employment gaps, the Turkish economy is supported by immigrants who predominantly come from the Syrian Arab Republic. The textile, garment, leather, and shoe industries are the most common employment areas for refugees in the manufacturing industry (Ministry of Labour and Social Security 2023). Syrians work mostly in informal work conditions and in sectors such as trade, construction, and manufacturing, which account for 79.1% of their work, and these are followed by the informality-based textile, clothing, leather, and footwear industries, where 30% of working Syrians are employed (Pinedo Caro 2020). The manufacturing sector, as indicated by Donat (2024) grew at almost a stagnant rate in 2023, with an annual growth of 0.8%. Its importance lies in the fact that it is one of the sectors with the highest numbers of paid employees (a total of 4,648,371 employees as of January 2024). According to the past five labor market reports by İŞKUR, among the highest jobs in demand are those related to the garment industry, with sewing machine operators, and the manufacturing sector, where welders are insufficient in number.

According to the OECD (2023 p. 102), more than 80% of employers in Türkiye face difficulty in filling vacant positions, especially in middle-level skills and blue-collar jobs. Such shortages are especially notable in the manufacturing sector (notably in the garment manufacturing industry), with most vacant positions remaining unfilled due to a lack of professional skills or insufficient work experience. As noted by a respondent in the study, the reasons for the labor shortage for occupational groups (sewing machine operators in the textile industry, manufacturing workers, welders, and wooden furniture carpenters) are mainly as follows:

“…lack of applications, dissatisfaction with the work environment and conditions, lack of professional skills, and inexperience”.

The qualitative analysis offers a unique insight into Türkiye’s labor market situation regarding the manufacturing sector. Out of the analyzed 19 companies, 89.5%, stated that they experienced problems in sourcing skilled labor for their sectors or companies. Respondents noted that “processes in administrative units progress more smoothly compared to production departments”, and that they face a small number of responses across all areas and departments of production. It was also noted that among the easiest professions and qualifications to find are unskilled jobs, such as warehouse workers and manual labor, that do not require expertise. Professions such as machine operators in the manufacturing sector are noted to be among the most easily filled roles, despite having issues related to qualifications, attributed to an oversupply of trained workforce in these fields, combined with deficiencies in their training processes.

Labor shortages in Türkiye’s manufacturing sector are mostly compensated by hiring migrant workers. However, there were notable cases of respondents indicating that they avoiding hiring migrants due to challenges such as language barriers, legal difficulties, and skill mismatches. In the manufacturing sector, there were notable findings alluding to gender discrepancies, with one respondent noting that

“Women are generally preferred for garment production, packaging…”

The interviews with enterprise representatives point out that there is a shortage of qualified workers in the production and service sector, such as garments, weavers, furniture masters, machine operators, and those in professions that can be regarded as intermediate staff.

In Türkiye, companies noted the importance of migrants in low-skilled manufacturing or hospitality occupations, but complained about the “loss of highly qualified employees” to the European and North American markets. In Ethiopia, even though a less pronounced trend of emigration to Western countries was noted compared to the other three countries, intense internal displacement due to ongoing conflicts was noted. This worry was emphasized by one of the respondents, who noted:

“Many employees are withdrawing from local companies and migrating to Arab countries… This challenge will continue and be stronger”.

In the qualitative study, it was found that the manufacturing industry contributed 32% of all analyzed companies. Respondents mentioned a limited supply of “welder, coil winders, transformer fitters, transformer testers”, with some of these occupations being more difficult to find as they are “dying out”, and some pointed out occupations such as “C-class drivers and manual labor”. Approximately 39% of companies believed that there had been no new qualifications in demand in the recent period, with nearly 45% of them being from the manufacturing sector. It is encouraging that out of the analyzed sample of firms, approximately 75% reported actively collaborating with educational institutions to enhance skill development. Internships and practical training programs are widely implemented, especially in the manufacturing industry. In the sector, 77.8% of respondents perceived emigration as a serious threat to operations, and companies mainly mentioned investing in employee training and collaboration with educational institutions to tackle skill shortages and mismatches.

4.1.3. Skill Mismatches and the Role of Ethiopian TVET Institutions

Ethiopia has faced a growing demand for skills, driven by economic restructuring and technological advancements. This has been mostly spurred by the government’s ambitions to transform the country into a middle-income economy, with the manufacturing and construction sectors being the main drivers. Each year, the Ethiopian labor market is expanded by 2 million new entries, on average. There has been a notable rise in mid- and high-level qualifications, especially in the manufacturing sector. Additionally, job postings requiring tertiary education increased from 25% to 40% between 2015 and 2020. Vocational qualifications have also gained importance in construction and agriculture, emphasizing technical ability (African Development Bank 2020; World Bank 2021b, 2024). On the other hand, Ethiopia’s growing pool of graduates highlights a mismatch between educational outputs and market needs. It is worth noting that TVET institutions contribute to skill development, but face challenges in meeting demand in manufacturing and construction. Based on the qualitative findings, almost all employers, including those in the service sector, interviewed expressed a high demand for employees with technical and practical skills who can lead and execute operations. For example, manufacturing companies find it difficult to gain access to applicants with high qualifications and the advanced technical skills needed to “effectively manage the production process and finishing”, as one respondent noted. Also, the respondents in the qualitative part of the study noted that machine operators are tough to find, and such experts are mostly imported, with one of the core problems found in the lack of practical work during education. Similarly to the cases of the other studied countries, it was noted that graduates attain mostly theoretical knowledge, which, in turn, creates a skill mismatch when entering the labor market. This was noted as one of the main reasons for underemployment in the country.

4.1.4. Shortages and Migration-Induced Workforce Gaps in Manufacturing

The persistence in skill shortages and labor market mismatches seems to be induced by several key aspects, such as insufficient practical training and the ongoing mismatch between educational outputs and labor market needs. For instance, in the manufacturing sector, employers across the analyzed countries seemed to note that traditional and more technical education lacks hands-on experience, which is necessary for advanced industrial processes. An Ethiopian manufacturing firm representative who was interviewed explicitly noted this problem, where graduates possess sufficient theoretical, rather than practical, knowledge:

“No university or polytechnic colleges are graduating professionals that meet our company’s expectations… All new employees have one thing in common: they lack practical skills”.

This leads to a lack of a skilled workforce in machine operation and machine maintenance, and even of workers who possess knowledge of the next-generation technologies in this sector. Notably, this is spurred by pronounced migration. For instance, a respondent from Ukraine highlighted the difficulties faced in maintaining production lines:

“It is a rather serious challenge today. We face difficulties in attracting and retaining personnel due to the effects of war… The shortage of labor is caused by the departure of qualified workers abroad and by internal migration”.

Ethiopian manufacturers, for instance, noted the scarcity of high-level machine operators, while Macedonian employers highlighted the difficulty of finding specific occupations that seem to be “dying out”, such as welders, coil winders, and transformer fitters. In the hospitality sector, a shortage of trained service workers, such as cooks, waiters, and receptionists, is quite common.

In Ukraine, war-related challenges have introduced skill mismatches and forced relocations and emigration, hampering an already strained manufacturing sector. Meanwhile, Türkiye faces labor shortages amid a brain drain, partially offset by the influx of migrant workers, particularly Syrians, who fill entry-level positions, but face challenges due to pronounced informality and legal constraints. North Macedonia’s modest wages and persistent skill deficits similarly fuel emigration, especially among manufacturing employees. Across these contexts, migration both worsens and mitigates workforce imbalances. The emigration of trained personnel intensifies shortages, while incoming workers ease some labor demands, although not always in line with employers’ specific needs. The manufacturing sector in Ukraine is characterized by war-induced sectoral shifts, where some firms transition to defense production and specialized logistics, which potentially create new skill gaps (e.g., advanced engineering and IT-based manufacturing). As one Ukrainian employer notes,

“Mobilization, frequent alarms, power outages, lack of analysis of the real needs of the labor market… are big challenges”.

However, even besides the forced migration, official data show a 60% drop in overall registered vacancies since 2020, with the food and mineral product subsectors most affected. In Türkiye, garment manufacturing, footwear, and textiles rely heavily on refugees, even despite language barriers and legal hurdles. Additionally, Welders, machine operators, and carpenters remain high in demand. One interviewee observes that

“At the end of our interviews, if we cannot find personnel with the required qualifications, we prefer to end our search… rather than leave the position unfilled”.

With an average wage of approximately EUR 340 in manufacturing, many skilled workers in North Macedonia opt for jobs abroad. As already noted, welders, tailors, and coil winders seem to be job positions that are increasingly hard to fill. In Ethiopia, rapid manufacturing expansions reveal a shortage of advanced machine operators and technical engineers.

4.1.5. Common Sector-Wise Challenges

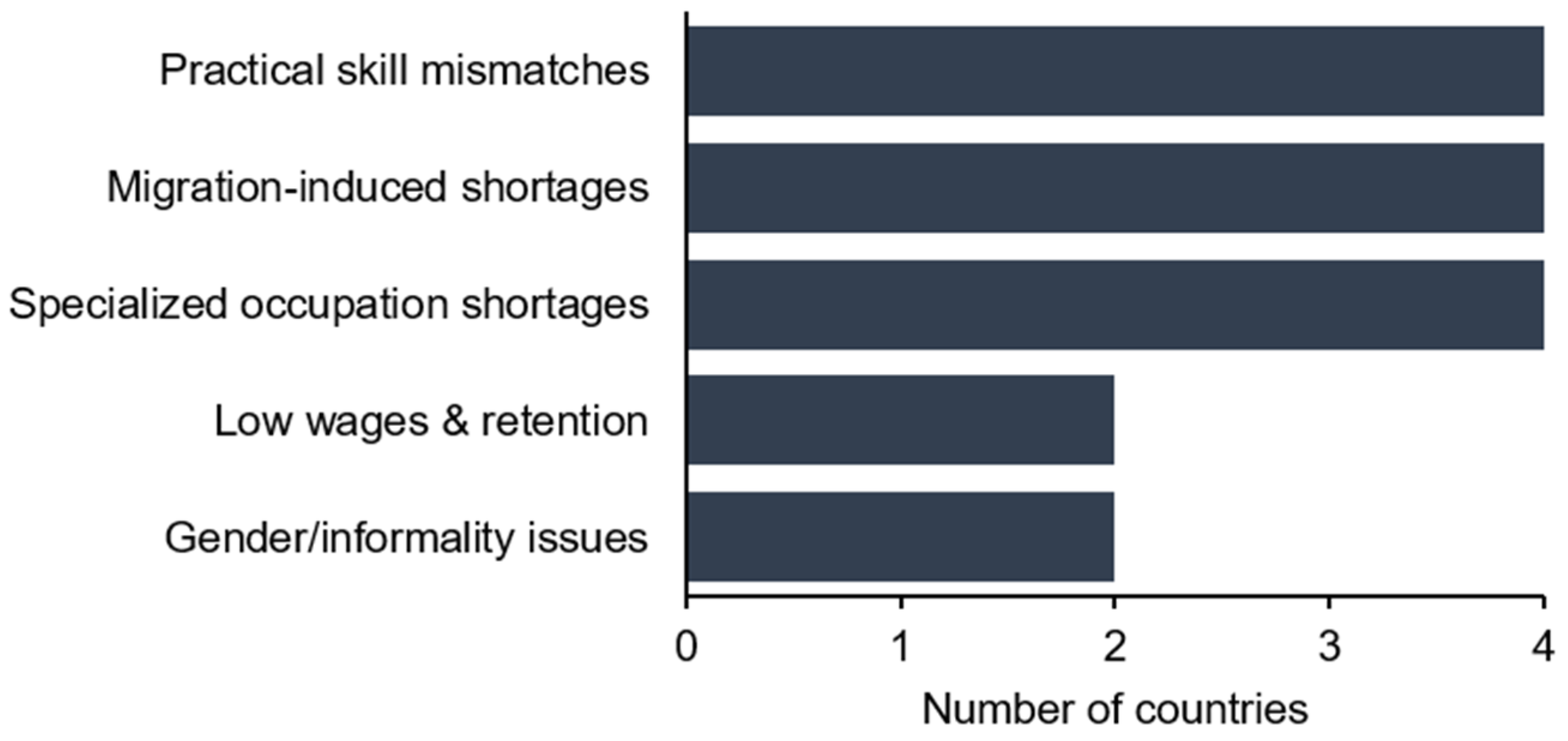

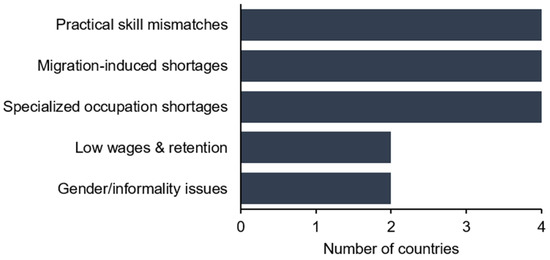

Even though the four countries’ cases are distinct by default, the study shows that common challenges exist when the manufacturing sector is analyzed. For instance, even though, in two cases, low wages and gender/informality issues arise explicitly, it is more common for the manufacturing sector to experience practical skill mismatches, migration-induced shortages, and specialized occupational shortages (see Figure 3). This can be partially attributed to overly theoretical educational systems producing graduates that require sufficient investment in additional training, and both internal (typical for Ukraine and Ethiopia) and external displacement (North Macedonia and Türkiye) of the labor force actively seeking better job opportunities.

Figure 3.

Cross-cutting challenges in the manufacturing sector.

Table 1 summarizes the key challenges identified for the manufacturing sector across the interviews with stakeholders. Across the four countries, the manufacturing sector faces acute labor shortages, with difficult-to-fill roles including defense engineers, machine operators, tailors, welders, and technical engineers. On the other hand, skill mismatches are driven by diverse challenges. For instance, Ukraine faces war-induced shifts in demand, North Macedonia suffers from wage-related retention issues, Türkiye struggles with unattractive mid-level-skilled jobs and poor training, and Ethiopia’s training capacity lags behind its rapid industrial growth. Migration exacerbates shortages in all countries, ranging from mass emigration and internal displacement in Ukraine and Ethiopia, to brain drain and refugee labor (predominantly Syrian) in Türkiye. Wage-related issues are significant in North Macedonia and Türkiye, while in Ethiopia, the problem lies more in applicant qualifications, rather than pure wages. It is also worth noting that common challenges identified across all contexts are deficits in practical training, high demand for technical roles, and reliance on upskilling, automation, or migrant labor as coping strategies for persistent shortages.

Table 1.

Key manufacturing sector challenges identified in the interviews.

4.2. Information and Communication Technology Sector

In the study, independently conducted across the four partner countries (North Macedonia, Türkiye, Ethiopia, and Ukraine), information and communication technology appeared as a highly relevant qualification and occupation, demanding and harboring many employees and supporting the economy of the respective countries. In North Macedonia, IT is recognized and treated as a core economic sector and a cross-cutting qualification required by all economic sectors. Conversely, IT appeared as a cross-cutting qualification for all sectors in Türkiye, Ethiopia, and Ukraine, with varying levels of significance.

Moreover, IT plays a mediating role across the different economic sectors of the four countries. For example, industries and employing organizations are aggressively implementing IT products and services in the production process, management of products, and service provision to remain competitive and productive in their sectors (see Ministry of Labour and Social Policy (2021), for North Macedonia; (Ethiopian Statistical 2021 Service), concerning Ethiopia; Akin and Karadas (2023), in the case of Türkiye; and Schnitzer (2023), concerning Ukraine). With this understanding, the demands, supply, and shortages of IT skilled workers in connection to migration will be presented, comparing the four countries’ current experiences.

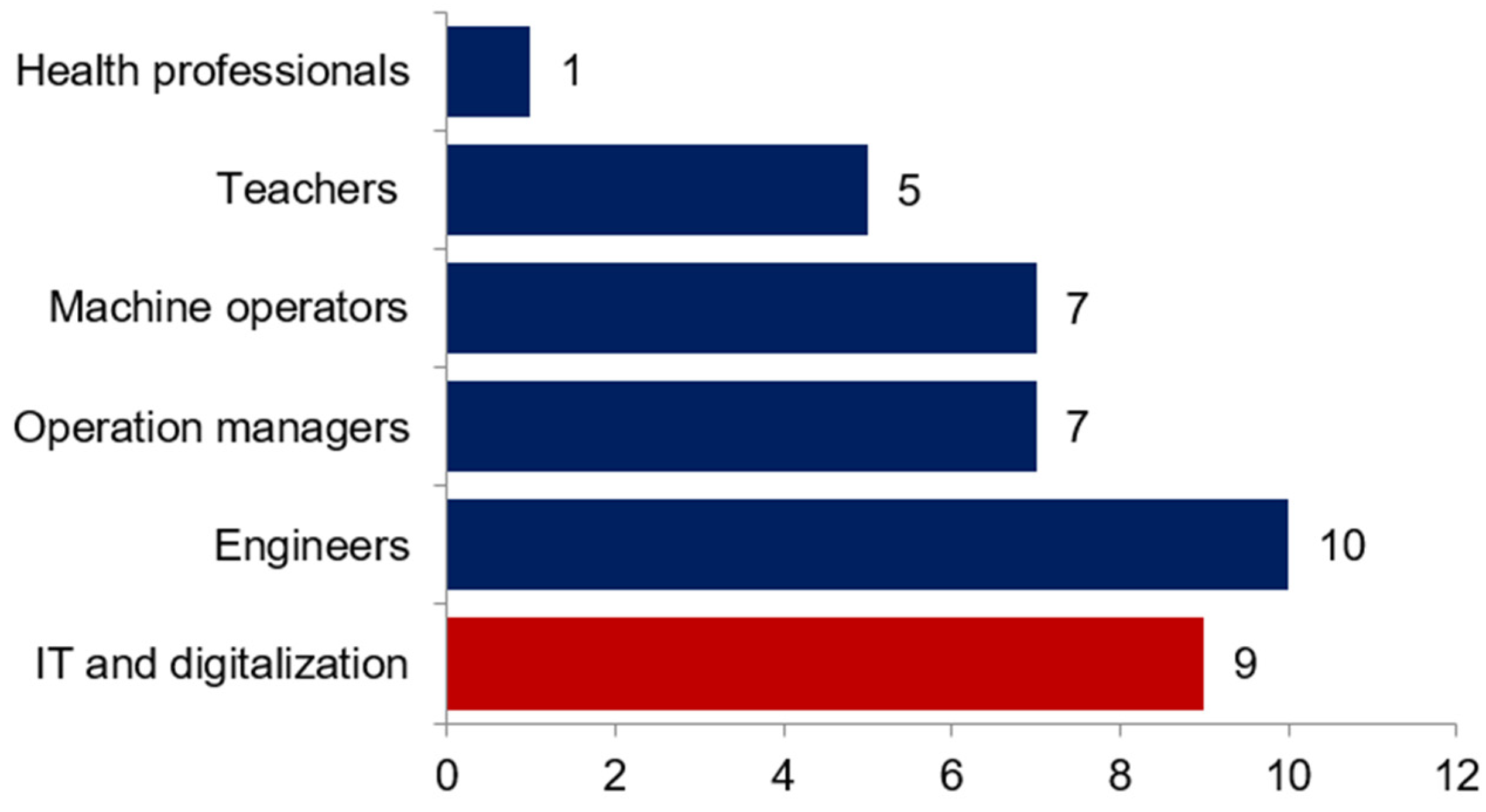

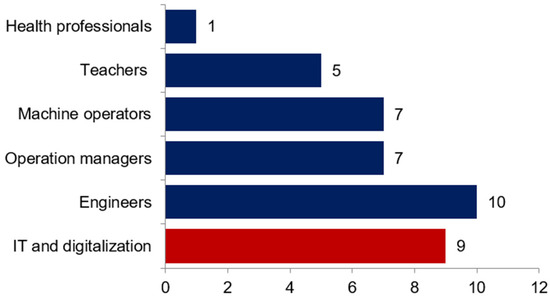

The demand and supply of IT professionals in the partner countries can be considered from two perspectives: high-skilled and low-skilled IT professionals. Low- and medium-skilled ICT professionals who can support companies’ administrative and routine activities are readily available in the market. Evidence from the four countries shows that HE and VET graduates can handle these jobs with a small amount of capacity-building support. For instance, in North Macedonia, IT professionals for software development and web design roles are easily available. In Ethiopia, fresh IT graduates and IT professionals for supporting administrative tasks are readily available from the market, and IT professionals are noted among the top occupations demanded in the Ethiopian labor market, based on the interview responses (see Figure 4). Similarly, employers in Türkiye can access software and computer engineers locally. Lastly, Ukraine has a large pool of IT professionals, though the ongoing war has led many of them to evacuate (Schnitzer 2023).

Figure 4.

The top occupations demanded in the case of Ethiopia.

Therefore, the supply of new graduates from IT-related programs and IT professionals for medium- and low-level technical tasks exceeds the demand, leading to skill mismatches, whereby degree holders perform tasks that can be accomplished by non-degree holders.

4.2.1. Demand for ICT Professionals Across the Four Countries

The most critical skill shortage in the four countries is of high-level IT skilled professionals. The high demand for this profession has also made it one of the highest-paid. Companies across the four countries face challenges in accessing these professionals. For example, 32% of companies interviewed in North Macedonia reported difficulties in finding suitable professionals, including highly skilled IT personnel. International and large companies in Ethiopia are often forced to recruit highly skilled IT professionals from abroad, resulting in a drain of hard currency. In Türkiye, the shift towards automation, the application of artificial intelligence, and robotization have ultimately increased the demand for IT professionals. In war-ridden Ukraine, there is a growing demand for a large number of highly skilled IT professionals, particularly in the areas of security and ICT firms.

Advanced IT skills are also reported to remain the most wanted profession in the future if companies wish to cope with the technology-mediated, ever-changing labor market dynamics. Thus, the labor market dynamic requires not just a few employees with highly sophisticated IT skills per company to develop and manage the software behind production, management, and service provision processes, but also necessitates that the remaining employees be equipped to operate those technologies.

High demand for, concurrent with a limited supply of, sophisticated IT skills remains a common agenda across the four countries, though the nature, degree of demand, and coping mechanisms differ. Addressing the nature and reasons behind this change would support efforts to establish mutually beneficial and sustainable solutions.

The first reason behind the demand for skilled IT professionals in the four countries is the fact that all competitive industries worldwide have already moved towards, or are moving towards, integrating high-tech tools and products into their systems, which demands specialized IT professionals across all levels of production. Thus, specialized IT professionals are not only demanded by IT firms, but by all companies. The lack of graduates in both quality and quantity from training providers exacerbates the situation.

4.2.2. The Impact of Education on Emerging Gaps in the ICT Sector

The relevance, up-to-date, and practicality of curricula and teaching provided by HE and VET providers is the second reason for the skills gaps created. The study reports from North Macedonia, Türkiye, and Ethiopia show gaps from this perspective. Training providers have limitations in creating and conducting teaching that equips graduates with the high-level IT skills demanded by industries. Ukraine is in a relatively good position, as it takes decisive measures to attract competent students with a strong mathematics background and train them to become competent IT professionals, though the war with Russia has negatively influenced the process and the availability of graduates.

4.2.3. Migration of ICT Professionals

Internal displacement due to natural and man-made factors is another reason behind the low supply of highly skilled IT professionals. Firstly, war, as a man-made factor, and natural disasters, like earthquakes, disrupt the teaching and learning process, which affects both the quantity and quality of graduates. Secondly, in the context of turmoil, highly demanded and skilled workers are the first to leave their areas, either permanently or temporarily. They are in demand all over the country or internationally, so they easily move to safer areas. In North Macedonia, employers view emigration as a “serious threat”, and this was specifically emphasized for the interviewed manufacturing and ICT firms. One respondent from the ICT sector in North Macedonia noted that

“Emigration represents one of the biggest threats to the labor market in North Macedonia”.

It is also a process that ICT firms usually do not have a strategy for. One of the respondents even mentioned that the problem might be systematic, by pointing out that

“From my perspective, it is an unstoppable process. People who leave are usually revolted by the system in the country (health, politics, education, etc.), not by the conditions in the company”.

In Türkiye, natural disasters like earthquakes, in Ukraine, the war with Russia, and in Ethiopia, the ongoing internal conflict over the last six years have typically displaced professionals, including IT experts, from their workstations, causing gaps. Therefore, North Macedonia is the only country among the four that has not recently experienced internal displacement due to war or natural disasters.

Another critical factor for the shortage of highly skilled IT professionals is migration. As indicated above, internal displacement due to conflict and natural disasters leads employees to move to safer areas where they can find job opportunities. Accordingly, skilled workers from Ethiopia and Ukraine have reported moving from conflict-ridden areas to safe regions or countries offering protection and work opportunities. Jobs in these areas are also closed or suspended and force workers to flee. For example, almost all companies in the conflict-ridden areas in Ethiopia experienced suspension of work. Similarly, in Ukraine, job opportunities were reduced by 30% compared to the pre-war level, and 4.6 million people lost jobs through the involvement of forced migration.

Beyond this, highly skilled IT professionals are in demand by developed countries, which offer better salaries and working conditions. This factor drains IT skilled workers from North Macedonia, Türkiye, and Ukraine to other European countries. In Ethiopia, better salaries are also a significant reason for the attrition and retention of employees with advanced technical skills.

4.2.4. Addressing Shortages in the ICT Sector

Different lessons have been drawn from each of the four partner countries’ attempts to address shortages of highly skilled IT professionals due to migration and contemporary issues. Ukraine is working hard on creating resilient companies by continuously training and upskilling workers and IT facilities, despite the loss of skilled workers due to migration and war. As a result, the qualifications of workers, especially in critical national security sectors, such as defense, logistics, IT, and energy, have increased. Additionally, all workers are provided with capacity-building training on new technologies and cyber security. Similarly, in-house training is used by companies in Ethiopia, where workers with advanced-level IT skills hired from abroad come with a mandate to train and coach local experts with similar training backgrounds, so that they can take over the roles after some time.

Migration of professionals to better-paying organizations and countries is inevitable, as long as the free movement of skilled workers is allowed. In these circumstances, the better way to attract and retain domestic skilled workers and returnees is by creating comparable working conditions at home. In this regard, the attempts of companies from North Macedonia and Türkiye can be taken as examples. One of the Macedonian ICT firms notes the following:

“We [the company] solve the problems with lack of qualifications and skills by cooperating with the continuous implementation of training workshops internally and in cooperation with external experts in the field, as well as by visiting conferences that are established at the world level, to monitor innovations and trends”.

Another respondent highlights the role that training centers have, by pointing out the following:

“We [the company] use all possible channels for recruitment, we emphasize the use of social networks for greater availability and personal recommendations from employees. We have cooperation with universities and Academies. Academies also produce candidates with great potential”.

A sustainable solution for skill shortages arises when education and training providers integrate high-level IT skills into their education and research. In this regard, North Macedonia’s plan to expand digital training across multiple age groups, as well as Ethiopia’s plan to integrate IT as a separate learning subject across all levels of education and its integration into each subject, can serve as examples. From an academic research perspective, Türkiye’s plan to integrate IT-related issues and innovation into postgraduate research has significant potential for fostering successive technology-oriented innovation.

IT firms or other companies in need of high-level IT skills can also close the skills gap by closely working with training providers. In this regard, companies can approach training providers with the specific skills they require, and curricula can be jointly developed. Students’ practice and research can be jointly supervised, resulting in benefits for the graduates, companies, and training providers. One IT-based company involved in the Ethiopia study successfully addressed the existing gaps by co-creating two master’s programs with a training provider.

4.2.5. Common Characteristics and Challenges in the ICT Sector

Across North Macedonia, Türkiye, Ethiopia, and Ukraine, the ICT sector is viewed as a vital and transversal skill base, which is crucial for growth, automation, industrial upgrading, and strategic functions such as defense (especially relevant for Ukraine) and cybersecurity. Table 2 summarizes the identified challenges faced by the four economies and how stakeholders respond to them, based on interview findings. While low- and medium-skilled IT talent remains relatively abundant across all contexts, high-skill shortages are severe. Countries face critical gaps in advanced roles, such as senior software developers, data scientists, cloud experts, and cybersecurity developers, driven by curriculum lags, emigration, and rapid tech adoption and progress on a global scale. Furthermore, labor migration, whether it is conflict-driven or economic, intensifies talent loss across all four countries. Such a phenomenon is especially pronounced in a work-flexible field such as ICT, where employees can work remotely or freelance and are not border-restricted. Despite these common challenges, firms predominantly adapt through upskilling, continuous development of university–industry partnerships, expert mentoring, and greater integration of IT into education. However, the recurring pattern is clear. While basic IT skills are adequately supplied, high-level talent remains scarce, and outdated curricula cannot keep pace with technological change. Cross-country coping strategies increasingly emphasize the rising need for education reform and internal workforce development, which, a priori, requires sufficient investment.

Table 2.

Key ICT challenges and responses across the four study countries.

4.3. Hospitality Sector

4.3.1. Labor Shortages in the Hospitality Sector

Considering the labor market demand over the last five years, the hospitality sector is one of the most highly demanded in North Macedonia, Ethiopia, and Türkiye, but not in Ukraine. The companies surveyed were small and localized in the three countries, and nearly all of them stated that they had faced serious difficulties in finding skilled labor. A participant in Ethiopia identified the lack of skilled labor as the reason for this challenge, stating that

“It is difficult to find an employee suitable for your desired purpose without further training... There are many job seekers, but very few have the necessary skills. Forget about skills, some of them are not even trainable”.

In North Macedonia, the hospitality sector shows relatively high vacancy rates, possibly due to turnover, seasonality, and persistent skill gaps. One respondent stated that

“The five qualifications in which there is a shortage… are waiters, cooks, pizza and pastry chefs, as well as receptionists”.

Occupation-level data show the strongest demand growth for service and sales workers, who typically require moderate or intermediate qualifications.

Türkiye presents a similar situation to North Macedonia, with a labor shortage in the hospitality sector, particularly for positions requiring medium-level skills that do not require higher education. As one respondent noted, “We face difficulties in finding certain professions. The professions where we have trouble finding personnel are, in order, cooks and cleaners”. The reasons for the labor shortage in the hospitality sector are attributed to a lack of applications, dissatisfaction with the work environment and labor conditions, lack of professional skills, and lack of experience (İŞKUR 2023). However, positions such as cleaning staff, restaurant service staff, baggage and valet services, receptionists, and cooks in the service sector are noted to be easier to fill, despite issues related to qualifications. This may be attributed to an oversupply of trained workers in these fields, combined with deficiencies in their training processes.

Under the theme of “Labor Shortage and Gender Inequality,” shared opinions indicate that while no gender discrimination is applied in recruitment, gender inequality is more prevalent in blue-collar roles compared to white-collar roles. Some companies encourage female participation in technical roles, while others claim that a spontaneous and natural balance has emerged without specific interventions. One respondent commented on this issue as follows:

“We don’t have gender discrimination, but certain jobs are more gender specific. For instance, in cleaning work, men tend to be less thorough, while women work with greater attention to detail and honesty. For this reason, we prefer women for cleaning jobs. In other roles, the gender of employees doesn’t matter. We find that our female employees are much more successful than male employees”.

In Türkiye and Macedonia, it was stated that women are preferred in certain areas due to their natural success, while in Ethiopia, this situation was described as a government policy. Positive gender representation is a government policy. However, the availability and interest of female candidates are important. For example, in training programs such as accounting, office management, ICT, and tourism and hotel management, you can find many female interns and trainers. However, it is difficult to find women in programs that focus on hard skills, such as those related to machinery, technological skills, and agriculture. For example, in our agricultural processing training program, the representation of female interns is less than 10%.

The inadequacy of the education system is emphasized by all respondents as a significant factor contributing to the lack of skilled labor. Company executives stated that education programs are heavily theoretical, disconnected from practical applications, and not aligned with the real needs of the business world, leading to a lack of quality in workforce training. A common issue mentioned is the lack of practical skills among graduates, combined with an overproduction of inadequately prepared graduates, which saturates the market with individuals lacking practical knowledge. One respondent noted that while the theory is sound, it is not readily applicable without hands-on experience, while others criticized the overproduction of ill-prepared staff. About 25% of respondents stressed that slow curriculum updates hinder skill relevance. A minority (18%) of respondents from North Macedonia acknowledged recent improvements, such as the inclusion of data analytics and digital marketing, but still found the updates to be too slow.

Finally, the hospitality sector also has its specificities. Cooks, waiters, cleaners, and mid-level service managers are in perpetual demand. A Turkish firm noted that

“We face some difficulties in finding certain professions… The professions where we have trouble finding personnel are cooks and cleaners”.