Abstract

Grounded in the dual frame of reference theory and a life-course perspective, this study explores how migrants’ past work experiences shape the perceptions of their actual work in the host country. The study examines pre- and post-migration working conditions and life satisfaction and compares them to perceptions of decent work (DW). Additionally, the study also compares the DW perceptions of migrants with prior work experience in their home country with those of migrants who lack such experience and started to work in the host country. Using the Decent Work Questionnaire (DWQ), the study analyzes responses from 137 participants. A two-step cluster analysis identified three distinct groups of migrants living in Italy with pre-migration work experience in their home country. These clusters have been labeled as follows: (1) “Better Life, Better Work”, (2) “Better Life, Worse Work”, and (3) “Same Life, Worse Work”. ANOVA results showed that the better life, better work group reported significantly higher overall DW perceptions, as well as higher scores on five out of the seven dimensions of the DWQ. Socio-demographic characteristics were further analyzed to explain variations across clusters. These findings highlight the complex interplay between pre- and post-migration experiences and their impact on migrants’ DW perceptions in their current roles. Additionally, such clusters were compared with a control group that does not have prior work experience in the home country. Results suggest that time-sensitive factors but also other factors, such as expectations, may determine those perceptions. Finally, the study offers practical recommendations for improving workplace conditions and provides insights for organizations and policymakers aiming to better support economic migrants’ integration in the workplaces.

1. Introduction

Migration is frequently driven by the promise of improved economic opportunities and better living conditions. Many migrants leave their home countries with the expectation that life and work in the destination country will offer greater economic stability (Fofanova et al. 2020), professional growth (Hoppe and Fujishiro 2015), and overall well-being (Calvo and Cheung 2018; Gao and Smyth 2011). However, the post-migration reality faced by migrants often diverges from those expectations, leading to a complex evaluation of their new circumstances (LeLouvier et al. 2022). The gap between expectations and actual experiences plays a crucial role in shaping migrants’ perceptions of their work conditions (Hoppe and Fujishiro 2015; Jasinskaja-Lahti and Yijälä 2011; Mähönen and Jasinskaja-Lahti 2013). Migrants who seek better job opportunities may become disillusioned if their employment does not meet their expectations, which negatively affects how they perceive and experience their work environment (Janta et al. 2011; Wright and Clibborn 2019).

One key framework for assessing the perception of one’s work environment is the concept of decent work (DW), which includes employment that is productive and offers fair income, security, social protection, and equal opportunities for personal development and participation in decision-making (International Labor Organization 1999, 2012). However, achieving DW is challenging for many migrants, who often face exploitative or precarious working conditions, such as low wages, insufficient social protection, and limited opportunities for career advancement (Guild and Barylska 2021). Furthermore, migrant workers frequently report experiencing discrimination and encountering barriers to professional development (Farashah and Blomquist 2020). Migrants are disproportionately employed in “3D jobs”—dirty, dangerous, and difficult—characterized by monotony, intense work rhythms, and higher risks in sectors such as construction, heavy industry, and agriculture (Mucci et al. 2019). When jobs in which migrant workers are employed fall below DW standards, they may experience not only diminished well-being and job satisfaction but also difficulties with successful integration into the host country (Shirmohammadi et al. 2023; Wright and Clibborn 2019). Such ineffective integration in the host country also poses significant risks to their physical health. For example, a systematic review highlighted that migrant workers face increased risks of infectious diseases, metabolic and cardiovascular conditions, and a generally lower quality of life, often because of the challenges in accessing local health services (Mucci et al. 2019). When, on the other hand, migrants are employed with secure, fair, and supportive conditions, they are more likely to contribute economically and socially, with benefits both for the workers and the host country as a whole (Han et al. 2022; Huang et al. 2022).

Given the significant risks associated with poor working conditions, understanding how migrants perceive their work environment is essential. However, considering these perceptions requires focusing not only on current work experiences of migrant workers but also on the specific expectations they have, before their arrival in the host country, about life and work. In fact, migrants often arrive in the host country with expectations that play a key role in how they evaluate their employment conditions (LeLouvier et al. 2022). Therefore, we argue that it is critical to consider pre-migration expectations when studying migrant workers’ perceptions of DW. Existing research in work and organizational psychology (WOP) has predominantly focused on migrant workers’ experiences after their arrival in the host country, often overlooking the influence of pre-migration expectations. As Fujishiro and Hoppe (2020, p. 24) note, migrants are typically studied only after they arrive in the receiving country, with little attention paid to the hopes, goals, and aspirations they bring with them. These pre-existing beliefs and expectations may significantly shape how migrants perceive their job satisfaction, well-being, and overall integration into the new environment. In this context, a more comprehensive approach is needed in WOP studies—one that integrates both pre- and post-migration factors to better understand migrant workers’ experiences and perceptions of DW.

A recent study, part of the interdisciplinary European project PERCEPTIONS, examined migrants’ views before and after their migration to Europe between 2015 and 2023 (LeLouvier et al. 2022). The study showed a common perception among migrants that Europe is a land of prosperity, economic opportunities, and high living standards. However, the reality that migrants encounter often falls short of these expectations. Upon arrival, they frequently face significant economic and administrative barriers, such as delays in obtaining residency permits (which hinder access to jobs and associated benefits like social security) and, even after securing employment, living costs, taxes, and the inability to save or send remittances home. Furthermore, migrants reported that the quality of jobs found often does not align with their qualifications or expectations, leading to low wages and poor working conditions.

Building on these insights, the current study seeks to explore how migrant workers’ evaluations of their pre- and post-migration working conditions, along with their life satisfaction, could be associated with different perceptions of decent work in their current roles in the host country.

In this study, to measure such perceptions, we used the Decent Work Questionnaire, which assesses the quality of work and is composed of different dimensions, such as fulfilling and productive work, meaningful remuneration, health and safety, and social security (Ferraro et al. 2018). To achieve this, the dual frame of reference (DFR) theory (Suárez-Orozco and Suárez-Orozco 1995) offers a useful lens for understanding how migrants’ work perceptions are formed. This theory posits that migrants evaluate their current work conditions not only against the standards of their host country but also in comparison to the conditions they experienced before migrating. This dual comparison enriches our understanding of how migrants assess their actual work conditions in the host country, which could lead to differing views of decent work depending on their pre-migration expectations.

In addition to the DFR theory, the life-course perspective serves as a guiding framework (Fujishiro and Hoppe 2020). This perspective emphasizes the importance of considering an individual’s entire life trajectory—before, during, and after migration—when examining well-being and work experiences. Through this lens, migrants bring with them a set of experiences, aspirations, and goals that shape how they perceive their new environment. Their decision to migrate is influenced by social, personal, and historical contexts (Elder 1994), such as economic conditions, life stage, or family dynamics, all of which play a role in shaping their migration journey, including their expectations of work and life in the destination country.

Therefore, considering all these points, the research questions guiding this study are as follows:

- Do pre-migration work and life experiences differentiate migrants into distinct groups? What type of socio-demographic, work, family, and migration-related characteristics define these groups?

- Do perceptions of decent work vary among these groups of migrants?

- Do migrants with prior work experience in their home countries differ in their perceptions of decent work compared to those without such experience?

Pursuing these research questions, this study addresses previous calls to contextualize migrant workers’ lives as a continuous trajectory (Fujishiro and Hoppe 2020), expanding research on decent work for this specific workforce. Furthermore, this study aligns with emerging research that challenges the prevailing assumption that economic migrants automatically view the working conditions in the host country as an improvement over those in their home countries (e.g., Antonijević et al. 2011; Hendriks and Burger 2020; Sippola 2014). Instead, it broadens the scope by allowing migrants to assess not only their previous working conditions but also life satisfaction in their home country. In doing so, it highlights the significance of the DFR, where migrants assess their current life and work against their pre-migration experiences, offering a richer perspective on how they perceive decent work. Given the diversity of experiences present among economic migrants, a quantitative cluster analysis approach was used in order to process multiple types of data and, possibly, identify different groups of migrants on the basis of their work and life characteristics (Marko and Mooi 2019). Finally, by comparing the decent work perceptions of migrants with prior work experiences in their home country and those without this experience, this study adds a new dimension to the dual frame of reference (DFR) theory, incorporating a comparative lens that includes a control group of migrants who lack prior work experience, thereby offering a more comprehensive understanding of how pre-migration experiences—or the absence thereof—shape perceptions of decent work in the host country.

1.1. Dual Frame of Reference Theory

The dual frame of reference (DFR) theory offers a valuable lens for understanding how migrants evaluate their post-migration life and work conditions by comparing them to the experience they had in their home countries (Magaña Lopez and Rye 2023). Suárez-Orozco and Suárez-Orozco (1995) argue that a comparative perspective is crucial for how migrants evaluate their experiences in the host country, which is often perceived as a land of opportunity (Andreeva 2023). Although the living conditions in the receiving country may appear inadequate by local standards, migrants frequently emphasize the improvements in their circumstances compared to those experienced in their home country (Suárez-Orozco 1989). For instance, wages that may be regarded as low in the host country can still be viewed positively when contrasted with earnings in their country of origin. This relative assessment significantly influences migrants’ perceptions of their overall situation, fostering a sense of progress despite the difficulties encountered in the host country (Nieswand 2014). This point is best illustrated in the “status paradox of migration”, which refers to the tension between two opposing dynamics. On one hand, migrants often face potential downward mobility in the host country’s labor market, taking jobs that may not align with their qualifications or previous status. On the other hand, they experience perceived social advancement in the eyes of their home country peers. This perceived success is frequently symbolized by remittances sent back to family members, which serve as tangible evidence of their achievements abroad (Nieswand 2012).

The DFR further illustrates that migrants evaluate not only the economic but also the non-economic aspects of life in the host country. For example, Louie (2012) discovered that migrants facing similar or even worse financial situations than in their home country still expressed optimism regarding the broader benefits of living in the United States of America. Their comparative evaluations considered factors such as personal safety, national security, and freedom, which were perceived as significant improvements over the conditions they had left behind. Thus, DFR explains that some migrants may accept substandard working conditions in the host country because their frame of reference remains rooted in their prior experiences. Over time, these comparisons evolve, as first-generation migrants continually reassess their circumstances in light of changing conditions in both their home and host countries (Piso 2016).

Building on this theoretical foundation, the present study applies the DFR framework to explore how migrant workers assess their experiences both prior to and following migration. Specifically, the study focuses on two key variables to capture the pre- and post-migration phases: cross-national life satisfaction—which involves comparing life satisfaction before and after migration—and cross-national working conditions—which involves comparing working conditions before and after migration. Notably, the latter comparison is applicable only to migrants with prior work experience. These variables were selected because they reflect the central premise of the DFR framework: the comparative evaluation of migrants’ current life and work conditions relative to their pre-migration experiences. By analyzing these comparative assessments, the study aims to (a) identify distinct groups of migrant workers and (b) explore whether these groups differ in their perceptions of decent work. Moreover, the study also includes a control group of individuals without prior work experience in their home country to further enrich the theoretical understanding of the DRF framework. Migrants without pre-migration work experience often lack a reference point to evaluate the quality of their job in the host country. The absence of a baseline can lead to higher expectations regarding work conditions and wages, derived from idealized perceptions of opportunities abroad (Magaña Lopez and Rye 2023). Studies have shown that such migrants may enter labor markets with the assumption that their new environment will inherently provide better opportunities and improved work standards. However, when reality does not align with these expectations, dissatisfaction can arise, and jobs may be perceived as less decent (Wright and Clibborn 2019). Unmet expectations can be particularly pronounced among migrants in low-wage or precarious jobs. The lack of prior experience often positions them as more vulnerable to marginalization and mistreatment in industries with poor labor protections. Consequently, they may feel a greater sense of disillusionment compared to migrants with prior work experience, who might better anticipate labor market challenges (Treuren et al. 2020). Additionally, the absence of pre-migration work experience amplifies the challenges of adapting to work environments in host countries, especially when combined with limited local knowledge and weak social networks. This often translates into jobs that are more precarious and less satisfying, further exacerbating perceptions of indecency and inadequacy in the workplace (Bélanger and Giang 2013).

1.2. Life-Course Perspective

The life-course perspective also provides a valuable framework for understanding the complex interplay of factors that shape migrant workers’ experiences, from the pre-migration phase to their adaptation in the host country. When examining individuals’ well-being and work outcomes, this perspective emphasizes the importance of considering individuals’ entire life trajectories, including personal, social, and historical contexts, such as, for instance, age, family situation, or socio-economic status (Elder 1994). The life-course perspective suggests that these elements are not isolated but deeply interconnected, shaping how individuals navigate migration and its challenges.

For instance, age plays a crucial role in shaping the migration experience, presenting both positive aspects and unique challenges for each age group. Younger individuals, in the early stages of their careers, typically aspire to achieve higher education and secure employment. However, policy barriers can hinder their success (Priyadharshini and Watson 2012). In contrast, older individuals rely heavily on social ties within ethnic or cultural associations, which provide a sense of social embeddedness. Yet, their challenges may include discrimination and inadequate access to institutionalized care (Palmberger 2016). Middle-aged migrant workers, on the other hand, often benefit the most from social integration, as research indicates that they experience more positive outcomes compared to their younger and older counterparts. This suggests that younger workers experience different psychosocial dynamics compared to middle-aged and older individuals (Zhou et al. 2022). Thus, age significantly influences both the perceptions and aspirations of migrant workers, with varying challenges and benefits emerging at different life stages. These differences can ultimately lead to diverse perceptions of decent work.

Moreover, it is essential to consider the role of generational dynamics, which significantly shape migrant experiences by influencing both adaptation to host societies and engagement with homelands (Berg and Eckstein 2015). For instance, a study conducted by Foner (2015) in New York City underlines that the experience of immigrant parents and their U.S.-born children differ, reflecting both historical constraints and opportunities. This study highlights the importance of considering age cohort differences, as this generational shift reflects the evolving nature of the immigrant experience over time, and underlines that different cohorts navigate distinct challenges and opportunities in their adaptation processes. For instance, first-generation migrants often exhibit higher levels of trust in host country public institutions compared to their second-generation counterparts, who, over time, show weaker levels of trust as they become more acculturated and familiar with the host country’s institutional performances (Röder and Mühlau 2012).

In addition, migrants’ socio-economic status prior to migration, particularly their education and skill levels, significantly influences both their decision to migrate and their post-migration experiences. Highly skilled workers often expect to find fulfilling, productive work in the host country, while those with lower skill levels may prioritize financial security (De Haas 2023). However, many migrants face challenges when their education or skills are not fully recognized, leading to underemployment and lower wages. For instance, highly educated Polish migrants in the UK often find themselves in jobs requiring lower qualifications, resulting in dissatisfaction and limited socio-economic mobility (Nowicka 2014). This education-occupation mismatch forces many skilled migrants into low-paying, low-skilled jobs, regardless of their qualifications, which could significantly affect their perceptions of decent work.

Another important characteristic that could explain differences in economic migrants’ experiences in the host country is the situation and location of their families. For instance, migrants who leave their families behind in their home country often have fewer immediate household responsibilities, allowing them to focus more on their employment (Ndlovu and Tigere 2018). However, this separation can lead to emotional strain and feelings of isolation, affecting their overall well-being (Ahmed 2020; Griffiths et al. 2018; Richter et al. 2020). Conversely, migrants who bring their families with them to the host country face different pressures, such as the economic burden of supporting a household in a new environment. For instance, migrants in Jordan who relocated with their families faced significant financial challenges in the host country due to higher costs for housing, education, and healthcare (Kamiar and Ismail 1991). These family dynamics influence migrants’ perceptions of decent work, particularly regarding meaningful remuneration and adequate working time. Migrants who bring children with them often face additional financial strain from integrating their children into local education systems and addressing their social adaptation needs (Starovojtova and Demidova 2020). Moreover, housing and employment difficulties are primary challenges for migrant families. Finding stable, affordable housing in high-cost urban areas can severely deplete financial resources, and securing well-paying jobs that meet the economic needs of the family can be equally challenging (Liversage and Jakobsen 2010). Therefore, overall, migrants who relocate with their families encounter heightened economic and social challenges that may influence how they perceive their working conditions.

In light of the insights from the DFR and life-course perspective frameworks, this study aims to explore whether evaluations of pre- and post-migration work and life experiences aggregate into different groups and whether these groups are characterized by different socio-demographic characteristics, such as age and family location, along with other work and family-related factors. The research also seeks to understand if sociodemographic and work-family characteristics are associated with the distinct clusters that emerged and to understand the extent to which migrants belonging to these clusters believe their actual work is a decent one. Furthermore, this study examines the relevance of pre-migration work experience in assessing decent work by including, as a form of control group, migrants who lack work experience in their home country. While these latter individuals do not have direct access to personal work experiences from their country of origin, they can draw on the work experiences of their social network (e.g., extended family or friends), which have been shown to play a significant role in shaping migrants’ perceptions of work, compensating for the absence of firsthand experience (Delaporte and Piracha 2018). The absence of firsthand experience may lead these migrants to rely on alternative points of reference, such as interactions with compatriots or host-country citizens or observations of local working conditions (Bélanger and Giang 2013). Migrants without pre-migration work experience may therefore apply more rigorous standards when evaluating the decency of their current roles, particularly if their expectations are shaped by idealized perceptions of work abroad (Magaña Lopez and Rye 2023). However, given the exploratory nature of this study—guided by its third research question—we aim simply to observe differences between migrants with and without pre-migration work experience, without making definitive claims at this stage.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample and Procedure

An online survey, posted on Qualtrics, was proposed to migrants’ associations and labor unions that provide support to migrants in Italy, which were invited to inform migrant workers to participate in the survey; an invitation to participate was also posted on social media, and, finally, a snowball sampling technique, leveraging the researchers’ network, was also used. Participants accessed the online survey either by scanning a QR code from flyers distributed in print or via a secure link shared on social media platforms. The first page of the survey provided detailed information about the study and underlined the anonymity and confidentiality of responses, the voluntary nature of participation, and contact details of the researchers in case participants had any questions. After giving their consent, participants completed the survey, which took approximately 20 min. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the ethics committee of the University of Bologna Data collection took place from March to June 2024.

The sample comprised 137 migrants legally residing and working in Italy. The majority of participants were female (59.9%), the mean age was 32.3 years (SD = 10.55), and a substantial percentage of respondents had high educational qualifications (30.7% master’s degree or higher, nearly 22% bachelor’s degree, while 29.9% completed high school). In terms of region of origin, the vast majority of participants were Africans (75.9%), and in terms of religion, they were predominantly identified as Muslim (75.2%). Regarding residency status, 36.5% had acquired Italian citizenship, and 29.9% held long-term residence permits. A high level of Italian language proficiency was reported among the participants, with 44.5% rating their proficiency as excellent. This high proficiency is due to the duration of residence in Italy, which was, on average, of approximately 15 years (SD = 10.52). Further sociodemographic characteristics of the sample are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the sample in descending order (N = 137).

In terms of employment characteristics, the most represented sector was that of services (social services, hospitality, cleaning, and maintenance, 37.9%), followed by manufacturing (15.3%), transportation and logistics (10.2%), building and construction (8.8%), retail (5.8%), and other sectors, such as IT, healthcare, or agriculture below 5% of respondents. The majority reported a blue-collar type of job (55.5%), about half reported employment in small companies (49.6%), and nearly half of the participants (48.3%) held permanent contracts. Regarding earnings, the majority of the sample (36.5%) reported a monthly income ranging between 1000 and 1500 euros. Additional employment characteristics of the respondents are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Employment characteristics of the sample.

2.2. Measures

The questionnaire was available in Italian, French, and Arabic languages to accommodate the linguistic diversity of participants. The translation process followed a rigorous translation and back-translation procedure to ensure linguistic and conceptual equivalence across languages (Brislin 1970). The following scales were used.

2.2.1. Decent Work

Perceptions of decent work were measured using the Decent Work Questionnaire (DWQ) by Ferraro et al. (2018). This scale has 31 items, and the Italian validated version was used (Ferraro et al. 2021). It comprises seven dimensions: (1) fundamental principles and values at work—refers to fairness, dignity, and just treatment in the workplace and is measured with six items (e.g., “In general, decision-making processes about my work are fair”); (2) adequate working time and workload—gathers items that correspond to sound management of working time that allows a balance between work, family, and personal life and is assessed with four items (e.g., “My work schedule allows me to manage my life well”); (3) fulfilling and productive work—addresses the perception of individuals that their work contributes to the future, allowing them personal and professional development and sense of accomplishment, and consists of five items (e.g., “My work contributes to my personal and professional fulfillment”); (4) meaningful remuneration for the exercise of citizenship—concerns a remuneration that enables the worker to live autonomously, with dignity, and to take care of her/his dependents, and it groups four items (e.g., “The financial earnings from my work are fair”); (5) social protection—expresses the perception of being protected in case of loss of work or illness or the family being protected through a system of social security and the prospects for a decent retirement, and it is measured with four items [e.g., “I believe that I will have a retirement without financial worries (government or private pension system)”]; (6) opportunities—perception of job opportunities, entrepreneurship, and prospects for career growth, and it gathers four items (e.g., “Currently, I think there are work/job opportunities for an individual like me”); and (7) health and safety—individual perception of health and security in the work environment, and it has four items (e.g., “I have all the resources and support that I need to work safely”). Each item is answered on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 = “I do not agree” to 5 = “I completely agree.” Scale reliability and mean scores are reported in Table 3.

Table 3.

Means, standard deviations, Cronbach’s alphas, and zero-order correlations for all study variables.

2.2.2. Contextual Factors Related to Pre-Migration Experiences of Migrant Workers

Pre-Migration Work Experience

Participants were asked about their work experience in their home country before immigrating to Italy. The question was straightforward: “Did you have any work experience in your home country before moving to Italy?” Participants could answer either “Yes” or “No”. If yes, the Qualtrics platform presented them with the cross-national evaluation of work and life satisfaction—the following two questions.

Cross-National Working Conditions

Participants were required to evaluate their current work conditions compared to those in their country of origin. They following question was posed them: “Reflecting on your current working conditions and comparing them with those in your country of origin, what would best describe your current work situation compared to the past?” Participants chose one of the following three options: (1) “My current work situation is worse than in my country of origin”, (2) “My current work situation is the same as in my country of origin”, and (3) “My current work situation is better than the one in my country of origin”.

Cross-National Life Satisfaction

Then a question was asked about participants’ current level of life satisfaction relative to life in their home country. The aim was to capture changes in subjective well-being following migration. Participants were asked the following: “Considering your overall experience here in Italy and comparing it with your life experiences in your country of origin, how satisfied are you with your current life?” Response options included the following: (1) “Less satisfied than my life before”, (2) “As satisfied now as my life before”, and (3) “More satisfied now than before”.

2.3. Data Analysis

The analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics (version 24). Given the exploratory nature of this study, a two-step cluster analysis was used to identify natural groupings among respondents. A two-step cluster analysis is particularly suited to this purpose, as it can handle both categorical and continuous variables and efficiently identify groups, highlighting similarities within groups and maximizing differences between groups, ensuring an accurate segmentation of the sample population (Marko and Mooi 2019). The clustering was based on two categorical variables: cross-national working conditions and cross-national life satisfaction. To further investigate the associations between the identified clusters and various socio-demographic and employment characteristics, additional statistical tests were conducted. Given the small sample size and the low expected frequencies in some cells, traditional chi-square tests were not suitable for this analysis. Instead, the likelihood-ratio test (LRT) was used as a more robust alternative, as it provides a reliable approach in cases where the assumptions of the chi-square test are violated (Agresti 2002). The LRT compares the likelihood of the observed data under different models, making it particularly useful for complex models or sparse data, and helps ensure more accurate inferential conclusions (McCullagh and Nelder [1989] 2019; Hosmer and Lemeshow 2000; Rao 1973). Moreover, an ANOVA with bootstrapping test (given the limited sample size and variability in response rates) was used as a further analysis to examine differences in decent work perceptions across clusters, covering both overall perceptions and specific dimensions. To address limitations related to missingness, bootstrapping was chosen, as it enhances the robustness of the analysis by resampling the data multiple times, providing more reliable estimates of test statistics and confidence intervals. This approach is particularly useful when dealing with small samples, as it helps mitigate potential violations of the assumptions of traditional parametric tests, such as normality and homogeneity of variance (Efron and Tibshirani 1993; Mooney et al. 1993).

3. Results

The means, standard deviations, and correlations among key variables of the study are presented in Table 3.

3.1. Cluster Analysis and Migrant Workers’ Profile Descriptions

The two-step cluster analysis was conducted to identify distinct groupings within the dataset. The analysis included two input variables (i.e., cross-national working conditions and cross-national life satisfaction) and resulted in the identification of three clusters. The silhouette measure of cohesion and separation was approximately 0.7, indicating good cluster quality (Marko and Mooi 2019). This suggests that the clusters were well-separated, with a strong degree of internal cohesion and minimal overlap between clusters. The distribution of cases across these clusters is as follows: cluster 1 comprised 46% of the sample (n = 23), cluster 2 contained 22% of the sample (n = 11), and cluster 3 included 32% of the sample (n = 16). The clusters varied in size, indicating different patterns among the respondents.

3.1.1. Cluster 1: Better Life, Better Work

This cluster includes migrant workers who reported higher life satisfaction (i.e., cross-national life satisfaction) and better working conditions compared to their home country (i.e., cross-national working conditions). Men constituted 56.5% of the participants, while women accounted for 43.5%. A majority held a university degree (56.5%), followed by 34.8% with a high school education or less, and 8.7% who had vocational training. In terms of family status, 56.5% of workers had children, and 43.5% did not. Most workers in this cluster had permanent contracts (52.2%), while 43.5% were on fixed-term contracts, and a smaller proportion (4.3%) held seasonal contracts. Blue-collar roles were prevalent (60.9%), with a smaller portion of workers in white-collar positions (39.1%).

3.1.2. Cluster 2: Better Life, Worse Work

This cluster included migrant workers who experienced higher life satisfaction compared to their home country but faced worse working conditions, hence the label “Better Life, Worse Work”. Women constituted a slight majority at 54.5%, with men accounting for 45.5%. The educational background showed that 63.6% had a university degree, 27.3% completed high school or less, and 9.1% had vocational training. A larger proportion of workers had children (63.6%), while 36.4% did not. In terms of employment contracts, 57.1% had permanent contracts, while 28.6% were on fixed-term contracts, and 14.3% had seasonal contracts. Blue-collar jobs dominated (54.5%), while white-collar roles made up 36.4% of the workforce.

3.1.3. Cluster 3: Same Life, Worse Work

This cluster consisted of migrant workers who reported neutral life satisfaction in comparison to their home country but enjoyed better working conditions, leading to the label “Same Life, Better Work”. Men comprised 56.3% of the group, with women representing 43.8%. A notable 68.8% of participants had a university degree, 25% had a high school education or less, and 6.3% had vocational training. A smaller percentage of workers had children (37.5%), while a majority (62.5%) did not. Workers in this cluster had the highest proportion of fixed-term contracts (60%), followed by 40% with permanent contracts, and no seasonal contracts were reported. White-collar roles slightly outweighed blue-collar positions, at 50% and 43.8%, respectively.

3.2. Association Between Sociodemographic and Employment Characteristics and Cluster Membership

The likelihood-ratio test (LRT) identified statistically significant associations between cluster membership and several socio-demographic variables. In particular, age group showed a significant association with cluster membership, χ2(6) = 13.75, p = 0.033, indicating that age distribution differed meaningfully across the clusters. Migrant workers’ family location (living in Italy vs. living in the home country) also displayed a significant association, χ2(2) = 7.59, p = 0.026, suggesting that where participants’ families resided was related to cluster groupings. Additionally, migration status (citizenship vs. residency permit) was found to be significantly associated with cluster membership, χ2(2) = 6.64, p = 0.036, indicating that visa status varied across the clusters.

For employment characteristics, a significant association was observed for work time status (full-time vs. part-time), χ2(2) = 7.31, p = 0.030, suggesting that the distribution of employment types was meaningfully related to cluster membership. Table 4 provides a summary of the significant variables’ distributions across the clusters.

Table 4.

Distribution of significant socio-demographic and employment characteristics across the three clusters (percentages).

No other socio-demographic or employment characteristics showed significant associations with the clusters.

3.3. Migrant Workers’ Profile Comparisons with Decent Work

Table 5 presents the means and standard deviations of DW dimensions across the different migrant profiles, along with the corresponding ANOVA values. The first section of the table (a) provides a comparison among migrant workers with prior work experience in their home country (i.e., clusters 1, 2, and 3). The second section (b) compares these individuals with those who lack such experiences (i.e., the control group, group 4). The results are further elaborated and discussed in the following subsections.

Table 5.

Mean scores of the clusters on DW dimensions and ANOVA results of the comparisons among clusters 1 to 3 (section a) and among clusters 1 to 4 (section b).

3.3.1. DW Perceptions Among Migrants with Home Country Work Experiences (Three Clusters)

As shown in Table 5, section a, the mean scores of clusters are significantly different for global DW perceptions (F(47, 2) = 5.5; p < 0.05), fundamental principles and values at work (F(47, 2) = 4.37 p < 0.05), adequate working time and workload (F(47, 2) = 8.13; p < 0.05), fulfilling and productive work (F(47, 2) = 3.79; p < 0.05), meaningful remuneration for the exercise of citizenship (F(47, 2) = 3.96; p < 0.05), and health and safety (F(47, 2) = 5.91; p < 0.05). The bootstrapped Bonferroni post hoc analysis revealed significant differences in decent work perceptions across the three clusters. For global DW, cluster 1 (“Better Life, Better Work”) scored significantly higher than both cluster 2 (“Better Life, Worse Work”) and cluster 3 (“Same Life, Worse Work”), with 95% confidence intervals of [0.42, 1.29] and [0.11, 1.15], respectively. Similar patterns were observed for fundamental principles and values at work and adequate working time and workload, where cluster 1 consistently reported higher scores than clusters 2 and 3, indicating more favorable working conditions in these dimensions.

Significant differences were also found for fulfilling and productive work, with cluster 1 scoring higher than cluster 2 [0.20, 1.51] and cluster 3 [0.02, 1.30]. In the domain of meaningful remuneration, participants in cluster 1 perceived their compensation as more meaningful compared to cluster 3, with a confidence interval of [0.22, 1.58]. Additionally, health and safety scores were significantly higher for cluster 1 relative to cluster 2 [0.56, 1.82] and cluster 3 [0.12, 1.43].

In contrast, no significant differences were found in the social protection and opportunities dimensions, indicating similar perceptions across clusters. These findings suggest that cluster 1 exhibited more favorable decent work perceptions across most dimensions, reflecting better overall working conditions compared to the other clusters.

3.3.2. DW Perceptions Among Migrants with and Without Work Experience in the Home Country (Control Group: Group 4)

- (a)

- Description of the control group (group 4): no previous work experience in home country

This group consisted of migrant workers who reported having started their first work experience in the host country, leading to the label “No Previous Work Experience in home Country”. Females made up 71.01% of the group, and 91.3% of this group were under the age of 39 (55.3% were in the 25–29 age group). Almost half of the group (40.58%) had a university degree, and a remarkable 49.28% had a high school education. Workers in this group had the highest proportion of fixed-term contracts (47.83%), followed by 43.48% with permanent contracts and 8.7% with seasonal contracts. Blue-collar jobs slightly outnumbered white-collar jobs, accounting for 57.97% of the group, and 65.20% of this group had a full-time working status. The majority of these workers lived with their own family in Italy (84.6%), and 59.42% had the nationality of the host country.

- (b)

- Association between socio-demographic and employment characteristics, and migrant profiles including group 4

The likelihood-ratio tests (LRTs) confirm the statistically significant associations between membership of the four groups of workers (clusters 1, 2, and 3 and group 4) and the socio-demographic variables previously considered for the three clusters of migrant workers (presented in Table 4). Specifically, the distribution of age group still showed a significant association with cluster membership, χ2(9) = 40.00, p < 0.01. The location of the migrant workers’ families (living in Italy vs. living in the home country) also showed a significant association, χ2(3) = 30.97, p < 0.01. In terms of migration status (citizenship vs. residence permit), the LRT results showed a significant association between this variable and membership of the four groups, χ2(6) = 39.72, p < 0.01. A significant association was also observed for work time status (full-time vs. part-time), χ2(3) = 11.53, p < 0.01.

We also tested the association with other socio-demographic or employment characteristics for the four groups of economic migrants. Table 6 shows the results of the LRTs. The four groups of workers were statistically associated with migrants’ level of education χ2(9) = 25.50, p < 0.01, with parental status χ2(3) = 12.71, p < 0.01, and with providing financial support to one’s family χ2(3) = 8.24, p = 0.04. No significant associations were found between membership of the four groups and workers’ average monthly income (measured in euros).

Table 6.

Distribution of significant socio-demographic and employment characteristics across the three clusters and the control group (percentages).

- (c)

- Multiple group comparisons of DW

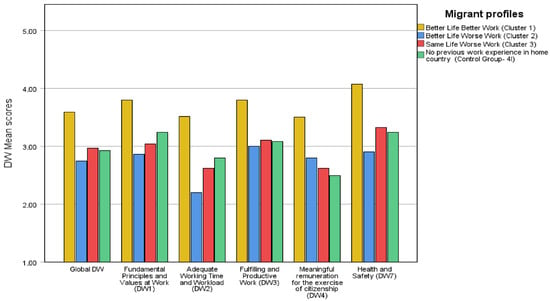

Similar to the findings reported in Table 5, section a, section b also reveals significant mean differences in decent work (DW) dimensions between group 4 (migrants without prior work experience in their home country) and those with prior experience (clusters 1, 2, and 3). Figure 1 provides a graphical summary of DW significant average scores across the different migrant profiles. Specifically, significant differences were observed in global DW perceptions, F(107, 3) = 4.73, p < 0.05; fundamental principles and values at work, F(107, 3) = 3.36, p < 0.05; adequate working time and workload, F(107, 3) = 5.34, p < 0.05; fulfilling and productive work, F(107, 3) = 3.36, p < 0.05; meaningful remuneration for the exercise of citizenship, F(107, 3) = 5.35, p < 0.05; and health and safety, F(107, 3) = 4.84, p < 0.05.

Figure 1.

Mean scores on DW dimensions for which significant differences are observed across clusters.

Similarly, the bootstrapped Bonferroni post hoc analysis revealed significant differences in perceptions of decent work (DW) across migrant profiles (clusters 1, 2, and 3 and group 4). Cluster 1 (“Better Life, Better Work”) consistently exhibited the highest perceptions of DW, even when group 4 (migrants with no prior work experience in their home country) was included as a control group. Specifically, cluster 1 reported significantly higher overall perceptions of DW compared to cluster 2 (“Better Life, Worse Work”) and group 4, with 95% confidence intervals of [0.07, 1.61] and [0.14, 1.17], respectively. Migrants in cluster 1 also demonstrated significantly higher perceptions of fundamental principles and values at work compared to cluster 2, with a 95% confidence interval of [0.01, 1.86]. Regarding adequate working time and workload, cluster 1 outperformed clusters 2 and 3, as well as croup 4, with 95% confidence intervals of [0.33, 2.27], [0.02, 1.74], and [0.06, 1.36], respectively. For the fulfilling and productive work dimension, migrants in the “Better Life, Better Work” cluster reported significantly more favorable perceptions than those in group 4, with a 95% confidence interval of [0.07, 1.36]. Similarly, participants in cluster 1 reported more positive perceptions of meaningful remuneration compared to group 4, with a 95% confidence interval of [0.32, 1.67]. Additionally, cluster 1 scored significantly higher on health and safety compared to both cluster 2 and group 4, with 95% confidence intervals of [0.17, 2.16] and [0.17, 1.49], respectively.

In contrast, no significant differences were observed in the dimensions of social protection, F(107, 3) = 2.03, p > 0.05, and opportunities, F(107, 3) = 0.59, p > 0.05, indicating similar perceptions across migrant profiles, consistent with findings within the three clusters. These results suggest that cluster 1 displayed more favorable perceptions of decent work across most dimensions, even when the control group (group 4) was included. This reflects better overall working conditions for migrants in cluster 1 compared to other profiles.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to explore how migrant workers’ pre-migration life and work experiences and the extent of their improvement or deterioration post-migration influence their overall perceptions of decent work and its specific dimensions. The two-step cluster analysis identified three distinct groups: “Better Life, Better Work”, “Better Life, Worse Work”, and “Same Life, Worse Work”. In the following discussion, we examine the characteristics of migrant workers within each cluster and consider how these attributes shape their perceptions of decent work. While some sociodemographic characteristics, such as age and family location, showed significant associations with cluster membership, others, such as gender and job type (blue collar vs. white collar), did not reach statistical significance. Therefore, we will focus on the significant associations to explain how socioeconomic characteristics influence perceptions of decent work.

First, it is important to note that the differences in DW perceptions among clusters cannot be attributed to a single factor only. Instead, these differences arise from a combination of characteristics that shape how workers perceive their job conditions. Factors such as employment type, age group, and family location compose a profile that collectively shape more or less favorable perceptions of work. For example, while younger workers may adapt more easily to physically demanding tasks, it is the combination of stable employment and fewer family-related pressures in the host country that increases the overall perception of DW in cluster 1. Here we offer possible explanations for the higher scores in DW perceptions of cluster 1 compared to cluster 2 and cluster 3 and, as well, to the control group (group 4). We do so by focusing on the significant associations between DW dimensions and socioeconomic factors.

A first social factor that plays a key role in shaping DW perceptions is age. Younger workers (25–39 years old), predominant in cluster 1, reported higher perceptions of Fundamental principles and values at work, which include fairness, respect, and adherence to workplace principles. Research suggests that younger workers are generally more adaptable and better equipped to handle the demands of modern workplaces, leading to more favorable perceptions of workplace fairness and respect (Brienza and Bobocel 2017; Steinberg et al. 1996). Their physical resilience seems also to contribute to better perceptions of Health and safety (i.e., the perception of being protected from risks to physical health and of having safe environmental conditions at the workplace), compared to older workers (Jones et al. 2011), who constitute the majority of cluster 2.

A second social factor contributing to overall higher DW perceptions of cluster 1, compared to clusters 2 and 3, is full-time employment, a defining feature of cluster 1. Full-time workers benefit from more stable working conditions, including structured roles, opportunities for skill development, and greater job security (Gyansah and Guantai 2018), which enhance perceptions of Fulfilling and productive work. Full-time employees tend to experience less job insecurity, which positively impacts their overall job satisfaction and sense of productivity. Moreover, workers in cluster 1, whose families mostly reside in their home country, likely experience fewer daily pressures related to childcare and household management, allowing them to focus more on work and perceive Adequate working time and workload more positively (Dyer et al. 2011). This aligns with previous research showing that migrant workers living in crowded spaces with family members have limited opportunities to rest after long hours, restricting their ability to restore personal resources (Jones et al. 2024; Huang and Yi 2015). Additionally, not having family responsibilities in Italy may reduce living expenses, leading to higher perceptions of Meaningful remuneration for the exercise of citizenship. In contrast, workers in clusters 2 and 3, who mostly had family members living with them in Italy, likely faced greater financial pressures to support their households in the host country. Increased living costs, such as housing and daily expenses, might diminish the perceptions of the financial rewards of their work. This result highlights the importance of family location in shaping perceptions of Meaningful remuneration. Workers in cluster 1 have higher probability to send remittances to support their families back home while maintaining a more cost-effective lifestyle in Italy (Mahadi et al. 2017).

A second important result concerns the absence of significant differences in DW perceptions between cluster 2, “Better Life, Worse Work”, and cluster 3, “Same Life, Worse Work”. The two clusters share the “worse work” perception and differ in their cross-national life satisfaction (i.e., evaluation of life compared to their home country). Cluster 2 reported being generally more satisfied with their life compared to their home country, whereas cluster 3 expressed neutral feelings, indicating no significant improvement or decline in life satisfaction after migrating. However, this difference in life satisfaction does not appear to significantly influence their decent work perceptions. This could suggest that while life outside of work may be perceived as better in cluster 2, the actual working conditions—characterized by “worse working conditions” for both groups—are the primary drivers of their DW evaluations. It is possible that any perceived improvement in life circumstances for cluster 2 (such as better public services, or health care system) may not be enough to offset the challenges posed by their working conditions, especially in the context of the economic pressures and job limitations that both clusters face related to both having their families living in Italy. Thus, the “better life” perception does not seem to extend into their work environment, resulting in similar DW perceptions as in cluster 3.

At the same time, there may be other unmeasured factors contributing to the similar DW perceptions between cluster 2 and cluster 3. For example, personal aspirations and career growth expectations could play a significant role. Workers in both clusters have similar educational backgrounds—most hold university degrees (even though education was not significantly associated with cluster membership) but feel that their current job, whether blue collar or white collar, does not align with their aspirations. This mismatch between qualifications and the types of jobs available in the host country can lead to dissatisfaction, particularly if workers held higher-ranking positions in their home country but experienced a downgrade after migrating. This phenomenon, often referred to as occupational downgrading, has been documented in migration research as a common challenge faced by skilled migrants who often end up in jobs below their qualifications (Crollard et al. 2012; Fernando and Patriotta 2020; Nikolov et al. 2021). This mismatch could help explain why, despite different life satisfaction evaluations outside of work, both clusters report similar dissatisfaction with their working conditions.

Another result concerns the absence of significant differences across groups in the social protection and opportunities dimensions of decent work perceptions. This lack of significant differences might indicate that all groups perceive social protection and opportunities similarly, regardless of their cluster membership. Given that most participants hold residency permits and regular work time contracts, according to Italian legislation, they experience stable access to the national social welfare system. Similarly, equal scores on perception of opportunities could be due to the stability of work contracts, which minimizes perceived barriers to advancement. In other words, if work regulations, company policies, or work conditions related to these dimensions are standardized, it is reasonable that individual perceptions do not vary substantially.

Finally, the results of the multiple group comparisons with group 4, migrants with no previous work experience in their home country, suggest that perceptions of DW in the host country are shaped not only by prior work experiences in the home country but also by alternative points of reference and other factors. These factors may include family influences, individual characteristics such as education level, and exposure to precarious working conditions. The comparison of the three clusters of economic migrants with group 4 revealed notable differences in DW perceptions. Specifically, group 4 mainly consisted of young, second-generation female workers with a high school education or a university degree who lived with their families in Italy and often held citizenship of the host country, where they also had their first work experience. ANOVA results demonstrated that migrants belonging to group 4 exhibited lower scores than cluster 1 in five of the seven DW dimensions: global DW, adequate working time and workload, fulfilling and productive work, meaningful remuneration for the exercise of citizenship, and health and safety. These findings align with the hypothesis advanced by Orupabo et al. (2020), which posits that the dual frame of reference (DFR) differentially influences the work perceptions of immigrant children. Specifically, as second-generation immigrants acculturate to the host country context and internalize its work culture, the influence of DFR diminishes, and host country-based frames of reference gain greater prominence (Perez 2004). The DW perceptions of group 4 seems to support this hypothesis, indicating that second-generation immigrants evaluate their working conditions differently from first-generation workers, predominantly represented in the other clusters. This difference may be explained by the fact that migrants in the “no previous work experience” group are less influenced by a dual frame of reference when assessing their work achievements and conditions compared to their counterparts who have prior work experience in the home country. Instead, their evaluations seem to be more closely aligned with host-country norms and expectations, shaped by their integration into the local cultural and labor market context. These findings underscore the importance of considering generational status and prior work experience when analyzing the work perceptions of migrant populations, as these factors significantly influence how individuals evaluate their working conditions and achievement.

This result aligns with earlier research by Röder and Mühlau (2012), who found that first-generation immigrants tend to exhibit higher trust in public institutions compared to natives, a trend linked to the better quality of the institutional performance in the host country in contrast to that in their home country. Trust in institutions is also crucial in shaping perceptions of decent work, because, for instance, migrants consider the fairness, reliability, and support of the systems that govern labor markets and employment conditions. In first-generation immigrants, high trust in institutions may lead to more positive evaluations of their work conditions. In second-generation immigrants, as they acculturate, this trust in host institutions weakens as they compare institutional performance not with that of the country of origin but with that of the country of residence (Röder and Mühlau 2012), which may result in more critical assessments of their working environments.

4.1. Limitations and Future Directions

This study underscores the importance of considering both individual and contextual factors when examining migrant workers’ experiences. Pre-migration expectations, as well as personal factors such as age and family situation, significantly shape post-migration experiences and influence how migrants perceive decent work in the host country. This approach offers a holistic understanding of the evolving nature of migrant workers’ lives, highlighting the need to account for both personal circumstances and the broader socio-historical contexts in which these experiences unfold.

One of the key methodological limitations of this study lies in the reliance on self-reported data, which may introduce response bias, particularly when exploring subjective perceptions such as life satisfaction or decent work (DW). Migrant workers’ responses may have been influenced by their expectations or aspirations, which could skew their evaluations of work conditions and life satisfaction post-migration. Additionally, the cross-sectional design limits the ability to infer causal relationships between pre-migration experiences, post-migration conditions, and DW perceptions.

Longitudinal research would offer a more solid understanding of how migrant workers’ perceptions evolve over time and how shifts in employment status or family dynamics impact their DW evaluations. Migrants at different stages of life and settlement may face different challenges and opportunities that affect their employment stability, social mobility, and future expectations. For example, middle-aged workers (40–54 years old) and older workers (55+ years old), who predominantly characterize cluster 2, may develop different career prospects and adaptation strategies than younger workers in clusters 3 and 4 who entered the labor market in the same historical period. Given these differences, future research should examine how factors such as age, length of stay in the host country, and employment stability interact in shaping work and life expectations and integration pathways over time. A longitudinal framework would also allow a more comprehensive life course perspective to better understand the evolving needs of migrant working populations. Future studies should incorporate the temporal dimension by collecting data before and after migration, as well as during key career and life events. These may include changes in marital status, becoming a parent, acquiring citizenship of the host country, securing a stable or recognized job, or experiencing job loss. This approach would allow researchers to track changes in migrants’ work expectations over time, providing valuable insights into how and when psychosocial processes related to the dual frame of reference develop and shape perceptions of DW.

Another significant limitation is the relatively small sample size (137 participants), particularly due to participant loss during the data collection phase. An additional notable number of participants were excluded from the analysis because they did not have prior home-country work experience. This reduction in sample size affected the robustness of the cluster analysis and limits the generalizability of the findings. In addition, African migrants are overrepresented (75.9%) in the sample in comparison to other ethnic groups, limiting even more the generalizability of the findings. Although the results of this exploratory analysis are promising, future studies should address these limitations by replicating the study with larger and more representative samples of migrant workers. The country of origin of migrant workers and the related national culture about work, such as meaning of work, might affect the perception of decent work. Furthermore, it is important to ensure that the size of the clusters is increased for a more comprehensive understanding of DW perceptions across different groups.

Furthermore, the study did not account for certain potentially influential variables, such as personal aspirations, career growth expectations, and access to social networks. These unmeasured factors likely play a significant role in shaping migrant workers’ job satisfaction and turnover intentions, particularly for those experiencing occupational downgrading. While the study acknowledges the role of aspirations and occupational mismatch, it does not delve deeply into how these factors contribute to DW perceptions across clusters. Future research should aim to explore these variables in greater depth, perhaps through qualitative interviews or mixed-methods approaches. Moreover, longitudinal studies that follow migrant workers over time would help to capture changes in their DW perceptions and career trajectories, particularly in relation to occupational mobility or skill utilization in the host country. Additionally, future studies should incorporate a more comprehensive analysis of structural barriers such as discrimination, labor market segmentation, and limited career mobility that migrants often face. Investigating how these barriers intersect with the socio-demographic factors explored in this study could provide a richer understanding of the challenges migrants encounter in securing decent work. Integrating established theories, such as the psychology of working theory (PWT) or precarity theory, would offer a more robust framework for examining the impact of both structural and psychological factors on migrants’ work experiences. These frameworks could also be used to explore the role of job insecurity and social connectedness in moderating the relationship between DW and turnover intentions, further advancing the study of migrant labor dynamics.

4.2. Practical Implications

This study suggests actionable steps for HR managers, employers, and practitioners aiming to improve decent work among migrant workers. One key priority is enhancing job security through full-time employment. Stable, full-time roles foster positive perceptions of fulfilling and productive work and adequate working time and workload, underlining the value of transitioning part-time or precarious workers to secure, full-time positions to reduce job insecurity and improve their sense of productivity and fulfillment. Fostering an inclusive workplace culture is also vital. When migrant workers perceive fairness and respect (i.e., fundamental principles and values at work), their overall job satisfaction improves. Employers can achieve this by implementing cultural sensitivity training, anti-discrimination policies, and inclusive leadership practices, creating an environment where migrant workers feel acknowledged and valued. Encouraging open communication between migrant and native employees also helps bridge cultural gaps, build social connections, and reduce feelings of isolation.

Finally, ensuring a safe and healthy work environment is crucial. While younger workers reported higher satisfaction with working conditions, older workers, especially those in cluster 2, may face greater physical demands or health concerns. Employers can address these issues by creating ergonomic workspaces, providing regular health and safety training, and offering appropriate resources and equipment to minimize physical strain, thus supporting well-being across all ages. In addition, considering migrant workers of clusters 2 and 3, who share a “worse work” perception but, at the same time, a high rate of high education, offering targeted training programs to address skill mismatches or skill gaps might increase workers’ fit to the job, job satisfaction, and, consequently, firm productivity. At the same time, being aware of and recognizing the qualifications and previous experience and expertise of these workers, as well as the offer of mentoring opportunities, might be, again, beneficial both for the migrant workers and for the company itself, as it would take full advantage of migrant workers’ resources.

By focusing on these areas—job security, inclusivity, health and safety, and training—employers can improve the working conditions for migrant workers. These efforts not only enhance job satisfaction and retention but also contribute to a healthier, more productive workforce, benefiting both workers and organizations alike.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: M.Y.S. and S.Z.; data analysis: M.Y.S. and S.D.; writing—original draft preparation: M.Y.S.; writing—review and editing, M.Y.S., S.D. and S.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of University of Bologna (protocol code 0001237 and 4 January 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Agresti, Alan. 2002. Categorical Data Analysis, 2nd ed. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Sarah. 2020. Women Left Behind: Migration, Agency, and the Pakistani Woman. Gender & Society 34: 597–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreeva, Larisa. 2023. Realization of Opportunities as a Driver of African Economic Migration to Europe. Asia and Africa Today, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonijević, Dragana, Ana Banić Grubišić, and Marija Krstić. 2011. Guest Workers–From Their Own Perspective. Narratives About Life and the Socio-Economic Position of Migrant Workers. Etnoantropološki Problemi/Issues in Ethnology and Anthropology 6: 983–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, Mette Louise, and Susan Eckstein. 2015. Introduction: Reimagining migrant generations. Diaspora: A Journal of Transnational Studies 18: 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bélanger, Danièle, and Linh Tran Giang. 2013. Precarity, gender and work: Vietnamese migrant workers in Asia. Diversities 15: 5–20. [Google Scholar]

- Brienza, Justin P., and D. Ramona Bobocel. 2017. Employee age alters the effects of justice on emotional exhaustion and organizational deviance. Frontiers in Psychology 8: 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, Richard W. 1970. Back-translation for cross-cultural research. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 1: 185–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, Rocío, and Felix Cheung. 2018. Does Money Buy Immigrant Happiness? Journal of Happiness Studies 19: 1657–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crollard, Allison, A. B. De Castro, and Jenny Hsin-Chun Tsai. 2012. Occupational Trajectories and Immigrant Worker Health. Workplace Health & Safety 60: 497–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Haas, Di Hein. 2023. How Migration Really Works: A Factful Guide to the Most Divisive Issue in Politics. New York: Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Delaporte, Isaure, and Matloob Piracha. 2018. Integration of humanitarian migrants into the host country labour market: Evidence from Australia. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44: 2480–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, Sarah, Linda McDowell, and Adina Batnitzky. 2011. Migrant work, precarious work–life balance: What the experiences of migrant workers in the service sector in Greater London tell us about the adult worker model. Gender, Place & Culture 18: 685–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efron, Bradley, and Robert J. Tibshirani. 1993. An Introduction to the Bootstrap. Boca Raton: Chapman & Hall/CRC. [Google Scholar]

- Elder, Glen H., Jr. 1994. Time, human agency, and social change: Perspectives on the life course. Social Psychology Quarterly 57: 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farashah, Ali Dehghanpour, and Tomas Blomquist. 2020. Exploring employer attitude towards migrant workers: Evidence from managers across Europe. Evidence-Based HRM 8: 18–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, Dulini, and Gerardo Patriotta. 2020. “Us versus them”: Sensemaking and identity processes in skilled migrants’ experiences of occupational downgrading. Journal of World Business 55: 101109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraro, Tânia, Leonor Pais, Nuno Rebelo Dos Santos, and João Manuel Moreira. 2018. The Decent Work Questionnaire: Development and validation in two samples of knowledge workers. International Labour Review 157: 243–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraro, Tânia, Nuno Rebelo Dos Santos, Leonor Pais, Salvatore Zappalà, and João Manuel Moreira. 2021. The Decent Work Questionnaire: Psychometric properties of the Italian version. International Journal of Selection and Assessment 29: 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fofanova, K. V., A. A. Sychev, and D. M. Borisov. 2020. Factors of the Economic Adaptation of Migrants. Paper presented at International Scientific Conference “Far East Con” (ISCFEC 2020), Vladivostok, Russia, October 1–4; Vladivostok: Atlantis Press, pp. 2698–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foner, Nancy. 2015. Mobility Trajectories and Family Dynamics: History and Generation in the New York Immigrant Experience. Diaspora: A Journal of Transnational Studies 18: 24–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujishiro, Kaori, and Annekatrin Hoppe. 2020. Toward a life-course perspective of migrant worker health and well-being. In Health, Safety and Well-Being of Migrant Workers: New Hazards, New Workers. Edited by Francisco Díaz Bretones and Angeli Santos. London: Springer, pp. 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Wenshu, and Russell Smyth. 2011. What Keeps China’s Migrant Workers Going? Expectations and Happiness among China’s Floating Population. Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy 16: 163–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, Sian M., Dong Dong, and Roger Yat-nork Chung. 2018. Forgotten needs of children left behind by migration. Lancet 392: 10164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guild, Elspeth, and Anita Magdalena Barylska. 2021. Decent work for migrants? Examining the impacts of the UK frameworks of gangmasters legislation and modern slavery on working standards for irregularly present migrants. Global Public Policy and Governance 1: 279–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyansah, Samuel Tieku, and Hellen Kiende Guantai. 2018. Career Development in Organizations: Placing the Organization and the Employee on the Same Pedestal to Enhance Maximum Productivity. European Journal of Business and Management 10: 40–45. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Mingyan, Maolong Zhang, Enhua Hu, and Hongmei Shan. 2022. Decent work among rural-urban migrant workers in China: Evidence and challenges. Personnel Review 52: 916–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriks, M., and M. J. Burger. 2020. Unsuccessful Subjective Well-Being Assimilation Among Immigrants: The Role of Faltering Perceptions of the Host Society. Journal of Happiness Studies 21: 1985–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppe, Annekatrin, and Kaori Fujishiro. 2015. Anticipated Job Benefits, Career Aspiration, and Generalized Self-Efficacy as Predictors for Migration Decision-Making. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 47: 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosmer, David W., and Stanley Lemeshow. 2000. Applied Logistic Regression, 2nd ed. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Wanting, Lei He, and Hongxing Lan. 2022. The Impact of Self-Employment on the Health of Migrant Workers: Evidence from China Migrants Dynamic Survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19: 5868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Youqin, and Chengdong Yi. 2015. Invisible migrant enclaves in Chinese cities: Underground living in Beijing, China. Urban Studies 52: 2948–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Labor Organization. 1999. Decent work. In Report of the Director-General at 87th Session of International Labor Conference. Geneva: International Labor Office. [Google Scholar]

- International Labor Organization. 2012. Decent Work Indicators: Concepts and Definitions. Available online: https://webapps.ilo.org/public/libdoc/ilo/2012/470465.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Janta, Hania, Adele Ladkin, Lorraine Brown, and Peter Lugosi. 2011. Employment experiences of Polish migrant workers in the UK hospitality sector. Tourism Management 32: 1006–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasinskaja-Lahti, Inga, and Anu Yijälä. 2011. The model of pre-acculturative stress—A pre-migration study of potential migrants from Russia to Finland. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 35: 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, Katharine, Anita Ghimire, and Yvonne Khor. 2024. Living at work: Migrant worker dormitories in Malaysia. Work in the Global Economy 4: 89–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, Melanie K., Paul L. Latreille, Peter J. Sloane, and Anita Staneva. 2011. Work-Related Health in Europe: Are Older Workers More at Risk? IZA Discussion Papers, No. 6044. Bonn: Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiar, M. S., and H. F. Ismail. 1991. Family ties and economic stability concerns of migrant labour families in Jordan. International Migration 29: 561–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeLouvier, Kahina, Alagie Jinkang, Sara Carrasco Granger, Fiona-Kathrina Seiger, Lorenza Villani, Maha Yomn Sbaa, Valentina Cappi, Rut Bermejo, Gabriele Puzzo, Sergei Shubin, and et al. 2022. The PERCEPTIONS Handbook: A Guide to Understanding Migration Narratives & Addressing Migration Challenges. Available online: https://www.perceptions.eu/handbook/ (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Liversage, Anika, and Vibeke Jakobsen. 2010. Sharing Space-Gendered Patterns of Extended Household Living among Young Turkish Marriage Migrants in Denmark. Journal of Comparative Family Studies 41: 693–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louie, Vivian. 2012. Keeping the Immigrant Bargain: The Costs and Rewards of Success in America. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Magaña Lopez, Miriam, and Johan Fredrik Rye. 2023. Dual frames of reference: Naturalization, rationalization and justification of poor working conditions. A comparative study of migrant agricultural work in Northern California and South-Eastern Norway. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 50: 1428–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahadi, Syed Abdul Razah, Hanafi Hussin, and Abdullah Khoso. 2017. Linkages Between Income Resources, The Cost of Living and the Remittance: Case of Indonesian Migrant Workers in Sabah Malaysia. Borneo Research Journal 11: 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marko, Sarstedt, and Erik A. Mooi. 2019. A Concise Guide to Market Research the Process, Data, and Methods Using IBM SPSS Statistics. Berlin: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Mähönen, Tuuli Anna, and Inga Jasinskaja-Lahti. 2013. Acculturation Expectations and Experiences as Predictors of Ethnic Migrants’ Psychological Well-Being. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 44: 786–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullagh, P., and J. A. Nelder. 2019. Generalized Linear Models, 2nd ed. New York: Chapman & Hall. First published 1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooney, Christopher Z., and Robert D. Duvall. 1993. Bootstrapping: A Nonparametric Approach to Statistical Inference. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Mucci, Nicola, Veronica Traversini, Gabriele Giorgi, Giacomo Garzaro, Javier Fiz-Perez, Marcello Campagna, Venerando Rapisarda, Eleonora Tommasi, Manfredi Montalti, and Giulio Arcangeli. 2019. Migrant Workers and Physical Health: An Umbrella Review. Sustainability 11: 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndlovu, Everson, and Richard Tigere. 2018. Economic migration and the socio-economic impacts on the emigrant’s family: A case of Ward 8, Gweru Rural district, Zimbabwe. Jàmbá: Journal of Disaster Risk Studies 10: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieswand, Boris. 2012. Theorising Transnational Migration: The Status Paradox of Migration. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]