Abstract

The purpose of this article is to present findings, relationships, and value added from research on the experiences of women with terrorism in North-East Nigeria to interdisciplinary spaces and practice by using systemist diagrammatic representations. This work is regarded as worthwhile in both substantive and methodological terms for the following reasons: First, respective research projects with policy relevance will be presented in a visual format, highlighting their connectedness—easily digestible, but without losing the depth and breadth of the work. Second, the article provides a combination of diagrams with text (i.e., background methods and findings), making the contents accessible to different kinds of learners. Third, and finally, the visual approach creates clear interdisciplinary connections that provide a sound basis for further research, policy design, and practice without the loss of academic rigor. This article moves forward in seven sections. Section one provides an overview of the study. The second section introduces the systemist approach that will be implemented herein. Sections three through five use systemist graphics to analyze respective publications that focus on women and terrorism. Section six brings the preceding three studies into engagement with each other and addresses the greater significance of the work in the context of multiple disciplines. Seventh and last is the concluding section, which sums up the contributions of this article and offers some ideas for future research.

1. Overview

Conflict driven by terrorism and violent extremism in the Lake Chad Basin area of West Africa is the focus of this article. Violence brought about by terrorist groups has increased significantly over the decades. This escalation has affected women and other vulnerable groups significantly more than others. Disproportionate and negative effects have resulted from a combination of conflicts that have led to displacements and extreme poverty. These developments, in turn, have exacerbated the violation of human rights among women in this geographic area. All of that adds up to a vicious cycle that shows no sign of ending.

North-East Nigeria within the Lake Chad Basin is the location for the research featured in this article. The Lake Chad Basin consists of four countries with borders surrounding that body of water: Nigeria, Cameroon, Niger, and Chad. The main terrorist groups whose activities continue to drive violence in this area include Boko Haram and the ISWA—a division of the ISIS terrorist group.

The purpose of this article is to present findings, relationships, and value added from research on the experiences of women with terrorism in North-East Nigeria to interdisciplinary spaces and practice by using systemist diagrammatic representations. This work is regarded as worthwhile in both substantive and methodological terms for the following reasons: First, respective research projects with policy relevance will be presented in a visual format, highlighting their connectedness—easily digestible, but without losing the depth and breadth of the work. Second, the article provides a combination of diagrams with text (i.e., background methods and findings), making the contents accessible to different kinds of learners. Third, and finally, the visual approach creates clear interdisciplinary connections that provide a sound basis for further research, policy design, and practice without the loss of academic rigor.

This article moves forward in six additional sections. The second section introduces the systemist approach that will be implemented herein. Sections three through five use systemist graphics to analyze respective publications that focus on women and terrorism. The third section is somewhat longer because it introduces material that will not then need to be restated in the fourth and fifth sections. Section six brings the preceding three studies into engagement with each other and addresses the greater significance of the work in the context of multiple disciplines. Seventh and last is the concluding section, which sums up the contributions of this article and offers some ideas for future research.

2. What Is Systemism?

The Visual International Relations Project (VIRP) translates scholarship into graphic representations using the technique of systemism. The VIRP has built an online archive with visual representations for a diverse set of publications in the field of IR that is available to all—over 1000 diagrams and counting. The overall objective of the project is to make the vast amount of scholarship in International Relations (IR) more comprehensible as a whole and build bridges between and among various schools, methods, and substantive topics. This activity, in turn, is expected to push forward interesting questions and advance IR in an innovative way. The systemist technique can be used to create visualizations for cause and effect that have been expressed in words for either an individual publication or a blend of ideas from across works of scholarship. The systemist approach relies on what appear to be traditional ‘box and arrow’ diagrams but with rules that ensure rigor and reproducibility1.

The VIRP has already facilitated useful debates and promoted understanding of the vast and quickly growing knowledge base of IR in a pragmatic way2. This activity aligns with a realization that visual rather than strictly verbal communication is important for progress in the discipline. The idea is to present clear representations of complex ideas from respective sub-disciplines of IR. This work, in turn, builds connections across the various schools of thought, methods, and substantive topics as a platform for interdisciplinarity and constructive discussions. The VIRP’s mission has the potential to move IR forward in an innovative way and increase its applicability in practice.

3. Women, Education, and Violence in North-East Nigeria

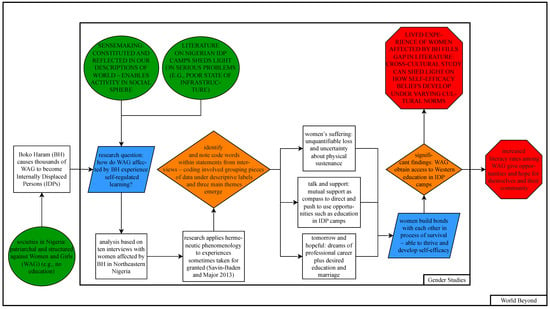

Idika-Kalu (2023) appears as Figure 1, which is available in the VIRP archive (James 2024b)3. The macro and micro levels of Gender Studies as a system, respectively, are the discipline as a whole and individual scholars within it. The World Beyond is the environment for the system of Gender Studies4.

Figure 1.

Women, Education, and Violence: How Women Displaced into Camps in North-East Nigeria Take Up Education (Cecilia Idika-Kalu 2023; Savin-Baden and Major 2013).

Before turning to the specific connections that appear in Figure 1, a few observations about this systemist exposition are in order. First, the diagram includes twelve components in Gender Studies (three for the field as a whole and nine at the level of the individual scholar) and three in the World Beyond. The components in the World Beyond all concern the experiences of individuals and groups. Potential elaboration of the graphic therefore might focus on the actions of states. How might states impact upon the agenda of Gender Studies and vice versa? Second, the distribution of components by type is as follows: three initial, six generic, two divergent, two convergent, and two terminal. There are a total of four points of contingency—two divergent and two convergent components—which combine to reveal that the analytical arguments in this figure are not at all deterministic. Third, and finally, the graphic is nearly complete in terms of the connection types that are possible; the only missing one is macro-to-macro. This gap effectively identifies linkages within Gender Studies as a whole as priorities for elaboration.

Turning to the substantive contents of Figure 1, consider the following question as a point of departure: Why does it make sense to look at the Responsibility to Protect (R2P) in the Boko Haram-generated crises through a gendered lens? True (2003) points to the people at the margins, like displaced women and non-state actors in world politics, and shows how feminist perspectives bring alternative conceptualizations of power. Accordingly, it has also been shown that the most efficient allocation of international development aid often is to provide women with appropriate socio-economic infrastructures such as health, credit, and education resources. Feminist theory therefore can inform ethical guidelines for humanitarian intervention, development aid, and human rights protection, among other global norms and values in application (The preceding observations establish the value of a gendered lens in seeking both pure and policy-related knowledge about women in North-East Nigeria).

Various directions observed in the lives of women, notably existence in displacement after experiencing violence from Boko Haram, are conveyed by Figure 1. The graphic (and Idika-Kalu (2023) in greater detail) looks at how the terrorism of Boko Haram shapes the lived experiences of women in North-East Nigeria. The agency women have experienced, during and after Boko Haram attacks, is analyzed; in particular, ways in which they access and take up education by the process of “sensemaking” and engage their choices in that context are interrogated.

Figure 1 is effective in showing the direct linkages between and among variables that mark the experiences of women. From the point of their encounter with Boko Haram, the diagram shows the interaction of violence unleashed upon women that resulted in homelessness and near hopelessness. The graphic also reveals how education offered in the camps, combined with the community of women with each other, creates a sense of hope within them. Figure 1 therefore is a notable step forward because of its visual representation of the space that women have navigated. The diagram situates the agency exercised by women who aim for, and self-actualize, pursuing an education even within the context of victimhood. Critical features that the visualization offers for this work include (i) positioning the findings clearly within the domain of Gender Studies, with a connection to feminist theory in IR, and (ii) establishing interdisciplinary value for Sociology, Political Science, Development Studies, and International Studies in an inclusive way.

Implications from the experiences of women in North-East Nigeria are explored as well. The main findings from this work include the connections between and among the notion of self-efficacy, the role of the community, and hope in self-actualization for women who have experienced first-hand violence from extremism. These aspects of agency and victimhood in their lives are assessed as women pursue education within their context.

Beginning in 2002, for over two decades, the Boko Haram insurgency—fueled by violent extremism that derives from the Salafi–jihadi ideology and associated worldview—has ravaged North-East Nigeria and the Lake Chad Basin of Africa. This insurgency has been marked by the kidnapping of women and children, the killing of people, and the burning of homes, leaving millions homeless in its wake. The violence impacted women and girls deeply—and in great numbers. For example, in April 2014, Boko Haram kidnapped 276 girls from a school in Chibok, a town in North-East Nigeria, in one fell swoop. Abducted partly for ransom and partly because Boko Haram resents Western education, especially for females, the girls still have not all returned from captivity. Boko Haram has also the reputation of having one of the highest numbers of women as suicide bombers in the history of terrorist groups. It almost goes without saying that, in many instances, mental and physical coercion are applied in order to force women to join in with the violence.

Apart from the “Chibok girls”, as the victims became known in the media, many other women and girls have been kidnapped over the years. Some of them have been able to escape from Boko Haram on their own or through the intervention of the state armed forces. In many cases, a multinational counter-terrorism joint armed force5 operating within the Lake Chad Basin and adjoining Sambisa Forest has played a significant role. Upon their escape from captivity, by whatever means, most of these women and girls have ended up living in Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) camps in neighboring cities like Maiduguri.

How, then, has displacement by the insurgency affected women’s learning and education? Connected to that question is this query, posed already in the literature: How do women affected by Boko Haram experience self-regulated learning that is driven by their experience of the group? Greater understanding of this aspect of their lived experience can create insight into how learning opportunities can be a source of resilience. Put differently, how is resilience for women, at an individual level, affected by violence? To answer that type of question, attention naturally turns to an interview-based approach toward gathering data.

Over two years, ten women aged 18 years or more, living in an IDP camp in North-East Nigeria owing to the violence of the insurgency, agreed to a series of interviews. This repetition of contact made it possible to access the depth, feeling, and evolution of their experience and perception of the same with a phenomenological approach. Phenomenology, a well-established research tradition, has been adopted in order to comprehend what participants with a given experience have in common. This approach is intended not only to uncover what has happened to individuals but how they experience a given phenomenon. In this study, the application consists of researching the phenomenon and its inner forms, which include thoughts and feelings. The most important part of this approach is a sustained appreciation for what the phenomenon means to the participant as she sees and experiences it. This research specifically applies hermeneutic phenomenology, which aims to shed light on experiences that are sometimes taken for granted (Savin-Baden and Major 2013). All of this is in line with a gender-centered lens—focusing on the experiences of women who are left without a voice otherwise.

Hermeneutic phenomenology, as had been expected, turns out to be valuable in understanding experiences interpreted among women affected by Boko Haram. The approach uncovers not just how women are affected by Boko Haram but also how they experience the phenomenon of education in the context of Boko Haram and IDP camps. Data collection relied on semi-structured interviews and focuses on the women’s lived experiences. A snowball sampling strategy recruited participants, with the guidance of reputable organizations in the area who (i) knew and worked with these women and (ii) understood the local environment. The participants had first-hand contact with the Boko Haram fighters and might have received elementary education or none.

Along those lines, the series of interviews served as a means to elicit the depth and breadth of our conversations and, subsequently, the data collected. A thematic analysis of the content from the interviews followed, highlighting salient themes that were further distilled using Bandura’s (1997) self-efficacy and sensemaking theory as a conceptual framework.

The theoretical framework from which this study draws, as proposed by Bandura (1997) on self-efficacy, is critical to a phenomenological understanding of lived experience. It offers a perspective on how confidence is developed via sensemaking—describing the processes of interpretation and production of meaning that individuals and groups utilize to grasp phenomena and produce inter-subjective accounts. In describing self-efficacy, Bandura points out that, if an individual believes something is achievable, their conviction positively affects performance. The theory holds that beliefs about personal self-efficacy move individuals to engage in challenging tasks, endure difficulty, and attain aspirations.

Self-efficacy, Bandura (1997) argues, usually emanates from four distinct sources: (1) mastery experience, drawn from an individual’s success in previous goal-setting; (2) vicarious experiences, whereby a person perceives their own capacity by looking at another individual and comparing their performance; (3) assimilating verbal or social persuasion, perhaps through affirmation and inspiration from others that affect their performance; and (4) emotional and physiological states that contribute to a feeling of accomplishment —self-efficacy grows in this case, via a woman’s knowledge of her ability to overcome a given task and attempt a more challenging one. In the context of self-efficacy theory, mastery experiences are the most important for the completion of more tedious tasks.

Theorizing based on self-efficacy helps to explain what Figure 1 highlights in a vivid way. The experience of loss and deep sadness with deprivation shown in the diagram is an important starting point for understanding how Bandura’s theory becomes relevant. Transitions from that point, to the feelings of hope the women expressed as they began to learn, are clear to see. Following the stages detailed in self-efficacy theory, the women reach the point of feeling hope about potential accomplishments. They describe their ability to dream and hope again as an accomplishment in itself. Understanding the phenomenon of the women’s experience with Boko Haram in a “whole” (i.e., comprehensive) way from their perspective is the major part of this work. Phenomenological research has great utility in capturing these ‘data’ based on personal experience; the systemist figure, in that context, presents an even more effective platform for presenting the dimensions of the study and its findings.

Three main themes and six sub-themes have emerged from this study. One main theme is the “suffering” of the women expressed as unquantifiable loss and worries about physical sustenance, followed by “support” by talking with family and friends. Affirmation is expressed, figuratively speaking, as giving the women a ‘compass’ to guide their lives and encouragement to take advantage of opportunities such as education in IDP camps. Finally, there is the bifurcated theme of “tomorrow”, and “hopes”, Yes, expressed as dreams and future aspirations of a profession or career, and as desired education and marriage. Social relations account for what has influenced the women to hope and aspire for in life beyond confinement. The bonds they built with each other to survive in challenging circumstances helped them thrive, therefore developing self-efficacy.

Before captivity, and subsequent residence in the IDP camp, several women and girls had no access to Western education. Deprivation experienced in former village life ensured that these women and girls would not be able to obtain Western-style education for religious and socio-cultural reasons. Access to schools in IDP camps represented an opportunity for agency, which many of them took by sending their daughters. Limitations and challenges faced by these women in their communities before the attacks by Boko Haram, however, made entry of members of the group remain unwelcome. The space offered to these women in the IDP camps is not considered comfortable; shelter and an opportunity for a fresh start are in place, but problems still exist.

What about the situation now, in an overall sense? According to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC), the number of displaced persons in the African region stood at 6.8 million in 2020 (IDMC 2021). In North-East Nigeria, Mali, and Burkina Faso, the mounting activity of groups connected to Islamist extremism greatly increased displacement and refugee movements as people fled to safety (Werz and Conley 2012). In the IDP camps, fortunately, at the very least, there are non-formal educational activities and opportunities for women and girls where they are taught life skills and a trade with a view to achieving financial independence. These training programs, given the number of new internal displacements due to conflict and violence across the sub-Saharan region, have been focused largely on counteracting the effects of gender-based violence. The programs are delivered in collaboration with non-profit organizations, such as the International Organization for Migration (IOM), which offers training for the response of women and law enforcement agents to gender-based violence in Nigeria’s Borno and Adamawa states (International Organization for Migration 2019).

Formal and informal educational activities in the IDP camps are associated with empowering women to resist and thus reduce their risk of experiencing gender-based violence (Simister 2010). According to Editeur (2023), education can provide specific agency for those living in IDP camps to be able to negotiate their social circumstances and also reduce the risk of experiencing sexual violence in the post-conflict period. Continuing education, both in general and related specifically to the prevention of GBV, is a critical part of any prevention plan (Simister 2010).

What, then, are the key findings? How might the contents of the systemist graphic in Figure 1 be summed up?

First, many women and girls who previously had no access to Western education due to socio-economic challenges can now obtain it via IDP camps. Education became symbiotic with the survival of these women in the almost overwhelming task of rebuilding their lives after direct experience with Boko Haram. The opportunity to learn a valuable curriculum, along with earning a living and raising children, made up their sensemaking process. Ultimately, the interview-based study from Idika-Kalu (2023) shows how the process of violence, displacement, and social relations (i.e., allied to the concrete opportunity of schooling) enabled women to access formal education and create new visions.

Second, networks and friend groups became a critical part of women’s lives, giving them mutual support. These women expressed their self-efficacy together, acknowledging the individual differences in their experiences of terrorism and trauma. The lived experiences of women affected by Boko Haram, as summarized in Figure 1, help to fill a gap in the literature with respect to the lives of this highly threatened population. Interview participants, albeit imperfectly, still represent hundreds of thousands of women of different cultures caught in the crossfire of conflict, having to make sense of life, and forging new meaning in the most desperate circumstances. Self-efficacy supports this sensemaking and survival endeavor, bearing fruit in such ways as the acquisition of Western education as a goal and achievement (Bandura 1997).

Third, and finally, cross-cultural studies on agency and victimhood of women, such as Idika-Kalu (2023), shed light on how self-efficacy beliefs form and grow in relation to varying cultural norms. When the women from the study eventually obtain an education, they become more independent and capable of supporting themselves and helping to rebuild communities devastated by terrorism. Even more importantly, the cultural norms that disadvantage these groups begin to shift, as more women can access the opportunity for education and are able to raise their families in similar ways. Increased literacy rates among women and girls not only give them professional or business opportunities, but these newfound capabilities also foster hope for their future and that of their communities.

4. Weaponized and Displaced Women in Mass Atrocities and the Responsibility to Protect (RtoP)6

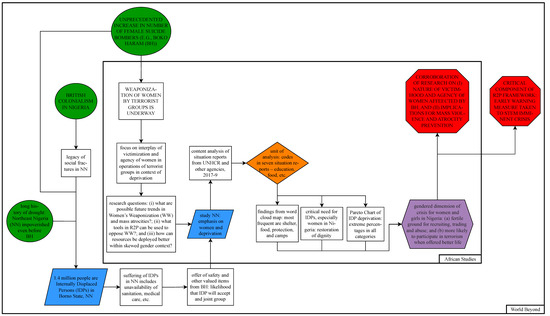

Idika-Kalu (2021) appears as Figure 2 and is available in the VIRP (2024) archive7. The field of African Studies is the system, with the World Beyond as its environment. The macro and micro levels of African Studies, respectively, are the field as a whole and individual scholars within it.

Figure 2.

Weaponised and Displaced Women in Mass Atrocities and the RtoP (Cecilia Idika-Kalu 2021).

Before focusing on the substantive contents of the graphic display, some general properties of it are worth noting. There are eleven components (nine at the level of the individual scholar and two in the discipline as a whole) in African Studies and eight in the World Beyond. The relatively small number for the discipline as a whole suggests that elaboration might focus on African Studies per se. Second, the distribution of components is as follows: three initial, ten generic, one divergent, two convergent, one nodal, and two terminal. With four points of contingency (i.e., adding up divergent, convergent, and nodal), this graphic resembles Figure 1 in the sense that it does not convey a deterministic message about the subject matter. Third, and finally, only one type of component is missing, namely, macro-to-macro. This gap, as in the case of Gender Studies for Figure 1, identifies the discipline as a whole as a priority for elaboration.

Turning to the substantive contents of the article, terrorist groups—like Boko Haram and Al-Shabaab—have emerged in recent years as key drivers of conflict in some African countries. These entities have caused mass casualties from persistent suicide bombings and other attacks. Operations of such groups have come to include the mobilizing and deploying of women in suicide bombings. Women have also been among the most victimized by terrorist groups—as targets, casualties, and internally displaced people. At the heart of this study is the analysis of the preceding twin dynamic by which women are both agents and victims of terrorist groups. We explore what existing knowledge tells us about possible future trends in the ‘weaponization’ of women and mass atrocities. The study also analyzes the utility of the Responsibility to Protect (R2P) tools in seeking to curb the weaponization of women. Connections between and among gender, suicide bombing, and displacement—and what these mean for R2P—round out the analysis of this study.

This work seeks insight, in a broad context characterized by deep deprivation, into the interplay between the victimization and agency of women in the operations of terrorist groups like Boko Haram. To achieve that goal, the focus is on the context and specific details about women internally displaced by Boko Haram activities in Nigeria. The research addresses the question of how displacement connects with Boko Haram activities and the Responsibility to Protect (R2P) as an issue of concern. The R2P is an agreed-upon framework for the protection of people from genocide, crimes against humanity, mass atrocities, and war crimes. The United Nations (UN) endorsed R2P in 2005 and carries the responsibility of protecting ‘at-risk populations’, building capacity for them, and carrying out various preventive measures (UN 2010). The United Nations recognizes the identification of states affected and the execution of an early warning assessment as under its purview.

Specific points of interrogation raised by this study are as follows: (i) What does existing knowledge tell us about possible future trends in the ‘weaponization’ of women and mass atrocities?; (ii) what tools in R2P can be used by state and international actors (i.e., development aid and security agencies) to stem or reverse the current tide of women’s weaponization?; and (iii) how can capacity-building and mediation be better deployed within the currently skewed gender-related context to help?

In engaging IDPs and the case of women and girls affected by terrorism, the question of the potential utility of R2P tools arises. It is important to look more critically at what within the R2P toolkit could be used to stop the rising tide of the weaponization of women in sub-Saharan Africa. Idika-Kalu (2021) highlights the nature of the deprivation experienced by IDPs, especially the female sufferers, and how this misfortune intersects with their weaponization and victimization. The ways in which violent extremism (especially by Boko Haram) is experienced, along with the poverty rife in the region and the roles some women played before finding the IDP camp, create harmful effects.

Indices deployed by the UN, IOM, and other NGOs in administering humanitarian aid are used to operationalize deprivation in the aggregate for Nigeria. Aid is conceptualized as material help in various forms given to IDPs. A content analysis of situation reports released by the UNHCR, the IOM, NEMA, and UNOCHA between 2017 and 2019 was carried out. These reports focus on the humanitarian interventions in the North-East part of Nigeria where Boko Haram has caused mass displacement of people. Analysis of that material aims to facilitate the identification of the most significant areas of deprivation (and attendant needs) for IDP women in Nigeria.

Boko Haram’s extreme Salafi–jihadi ideology puts women to work as killers and facilitates the breeding of prospective suicide bombers (Bukarti and Bryson 2018). Some participate in the group against their will, while others commit to it because they are aligned with the ideology. From my research and interviews with women who have experienced the horrors of Boko Haram, the preachings of imams and other religious scholars have served as a bulwark for women exposed to the extremist ideology of Boko Haram. Religious teachings that emphasize cooperation and peace offer a positive approach to the future. These alternative doctrines create hope as well.

It is important to address the weaponization of women using atrocity prevention frameworks that focus on the structural aspects that eventually lead to mass suffering. According to Jacob (2020), as long as deprivation in the lived experience of IDPs is acknowledged, proposals that include structural prevention in the form of intervention become relevant for the future. Structural prevention, which offers people recourse by directly addressing human rights, is designed to provide long-term solutions to the challenges that lead to mass atrocities.

Initiated as an Africa–European Union joint strategy between 2007 and 2015, the African Peace and Security Architecture is a comprehensive peace and security partnership designed for capacity-building and atrocity prevention in the region (EU 2017). The ECOWAS ECOWARN early warning and response system works closely with civil society groups to cover a spectrum of risk indices connected to atrocity crimes, human rights violations, conflict, and instability. It is important to design gender-intelligent capacity-building programs that directly engage the push and pull factors of terrorism and the ways in which women are affected as victims and agents. This is structural prevention at its best.

With regard to stemming the tide on the weaponization of women, invoking the R2P norms ultimately may become useful—or even critical. While a number of reasons account for the agency of women in violent extremism and the participation of people in general within terrorist groups, rational choice is highlighted here as a precursor. This is because an incentive-based model—which proposes that terrorists, like criminals, are rational individuals who act out of self-interest and with opportunity costs in mind—offers a baseline for further analysis. The dire straits of female IDPs in Nigeria—diverse indignities and lack of well-being—would seem to be key factors informing their agency regarding terrorism. Terrorism, put simply, is a form of behavior rooted in poverty and lack of education (Atran 2003; Becker 1968).

Findings from this study confirm deep deprivation among women who therefore seek safety, protection, provision of income, nutrition, and non-food items—the capacity to live with dignity. If Boko Haram offered these resources, along with some form of Salafist education and orientation to the women, there would be an incentive to become part of the group.

What might be done to head off such outcomes, which would strengthen Boko Haram? World polity theory suggests that the global system is one social system with a cultural framework that can be understood as a ‘world polity’. This perspective takes into account every actor in the world system and interactions with organizations like the UN as a whole, along with its participating states and individuals. The R2P as a norm becomes relevant; its mechanisms are critical for addressing the agency of women in terrorist groups and protecting their human rights and dignity. The global social system is governed by principles and models that shape the course and objectives of social actors and what they do (McNeely 2012; Boli and Thomas 1997).

The global social system is governed by principles and models that shape the course and objectives of social actors and what they do (McNeely 2012; Boli and Thomas 1997). This is connected to the “world polity” theory that suggests that the global system is one social system with a cultural framework that can be understood as a ‘world polity’. This perspective takes into account every actor in the world system and interactions with organizations like the UN as a whole, along with its participating states and individuals. For most outcomes, positive and negative, social actors at this level are influenced directly or indirectly by the global social system.

Policy recommendations and future research include the following:

Future research will explore the agency of women in violent extremism further. This will specifically study the place of capabilities and vulnerabilities in women’s terrorist group participation. Policy recommendations should account for the economic and pecuniary incentives for participation in violent extremism by women. This will counter the appeal of the groups to women. The agency women exercise is influenced by their “immediate community” and support groups. Policy design using bottom-up frameworks should invest in such structures in communities that will counter the narratives used to convert women, among other efforts.

5. Women and Terrorist Recruitment on the Internet

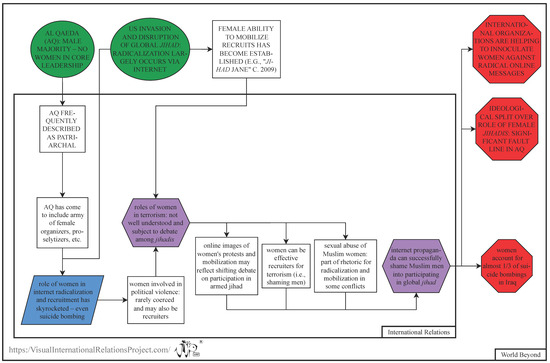

Via Figure 3, I engage with the work of Mia Bloom (2013). The system in this diagram is the field of IR, with the World Beyond as its environment. The macro and micro levels of IR, respectively, are the discipline as a whole and individual scholars within it8.

Figure 3.

In Defense of Honor: Women and Terrorist Recruitment on the Internet (Mia Bloom 2013).

Prior to discussion of the specific contents of the diagram, consider a few informative overall properties. First, there are nine (one at the level of the discipline and eight for individual scholars) components for International Relations and six in the World Beyond. This distribution suggests that elaboration could focus productively on the discipline as a whole. Second, with regard to types of components, there are two initial, seven generic, one convergent, two nodal, and three terminal. The presence of three contingencies (i.e., one convergent and two nodal) demonstrates that the present graphic, like the two preceding it, is not putting forward a deterministic account of the subject area. Third, and finally, two kinds of linkages are absent: macro-to-macro and micro-to-macro. Elaboration therefore might begin with consideration of how the findings of the study connect with IR as a whole, along with processes that emerge within the discipline itself.

At the time of publication for Bloom (2013), gender-based violence (GBV) and the targeting of women by Boko Haram was under-researched. Bloom (2013) engages the question of agency and the roles women play in terrorist groups of their own choosing. To start with the ‘bottom line’, the findings show the dimensions of women’s participation in Al Qaeda and the ways in which they have indirectly contributed immensely to the group’s activities. The study concludes with a review of the ways in which other actors can influence or support women’s choices about violent action.

Women, in the main leadership of Al Qaeda, are not often present. In spite of this ongoing exclusion, women are still among their most passionate advocates. This is especially interesting because the group is reputed to be patriarchal. Women’s participation in Al Qaeda and the roles they play (in)directly have taken different forms. These activities include online recruitment and information dissemination. Some women have even hosted online magazines to spread information on behalf of Al Qaeda.

Online shaming of men is also a major part of the role reserved for women. The message, in this context, would be framed as protection of the women committed to their care from non-believers—a rationale for participation in the group. Apart from propaganda activity, some women also put forward a justification for allowing themselves to become a part of even violent Al Qaeda activities. This is a divisive issue, touching on ideology, as many others connected to the group within and outside the Middle East think differently about the role of women.

Al Qaeda has strong patriarchal traits (Davis 2006), with the main leadership mostly consisting of men—the “al Sulba or the solid foundation” as it is called. However, a loose network of female supporters dispersed across the world has played a critical role that fostering continuity for the group. Women function as fund-raisers, organizers, and teachers and facilitate the discipleship of others. While females may not engage directly in battle or on the frontlines, they take care of critical functions for the group (Cook 2005).

It has been well researched that, in spite of coercion leading to female participation in terrorist groups in some instances, many times that is not the case. According to Mahan and Griset (2008), the role of women in violent extremism falls under four categories or functions: spies, sympathizers, warriors, and dominant other forces. Bloom (2013) also highlighted the work of Graham et al. (1994) that points to women’s social relationships with men becoming an indirect cause for violent behavior—likened to “Stockholm Syndrome”.

Technology and the use of the Internet enable women to go even further for Al Qaeda as supporters, participants, and recruiters. For instance, they contribute to chat rooms and share propaganda materials while remaining anonymous. With anonymity, some can disguise and even engage in actions while posing as men. This activity includes the use of false male names, disguising their voices, and so on. The women take advantage of this surreal form of equality that is available on virtual platforms to overcome gender norms that would otherwise hinder or even prevent their participation.

6. Engagement of Diagrams and Ideas About African Studies, Gender Studies, and Political Science

Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3 show clearly that the pre-existing environment impacts the role that women play in terrorist groups—as suicide bombers or otherwise. Another theme that connects all of the diagrams is the presence of patriarchal structures within which women engage as victims or agents of the groups.

New questions arise as a result of putting the systemist diagrams into contact with each other: What is the role of women and how do they exercise agency in their experience with Boko Haram (and possibly other terrorist entities)? In addition, how can counterterrorism measures be designed more effectively? A key consideration emerging from the systemist figures pertains to the socio-economic condition of women. More specifically, how does that determine the playing out of their victimhood and agency within Boko Haram? Put simply, the degree of economic empowerment emerges as an essential matter in seeking to answer such policy-related questions.

Interesting to ponder, in particular, is a comparison to female/women supporters of Al Qaeda, who sometimes are found to be wealthy. Would women affected by Boko Haram offer support, or seek to turn away, if in a much better financial condition than what is normally seen at present? Of course, there are more variables to consider—obvious examples are personal relationships and connections to the group—but the degree of economic empowerment comes to the forefront in exploring the experiences of women in the world of terrorism.

From all of the systemist figures, the salience of navigating agency as jihadis in Al Qaeda, in comparison with the effects of victimhood in Boko Haram, emerges as relevant to Gender Studies. The intersecting nature of identities based on culture and context, as seen in Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3, is a key concern for that interdisciplinary field as well. As we further study the systemist figures, in the flow from colonization to development challenges in Africa, women’s victimization and agency in terrorist groups stand out as subjects that warrant more attention from African Studies and Political Science.

7. Conclusions

Overall, the systemist figures present a strong translation of theorizing and findings to a format more easily digestible to visual learners and a wider audience outside of the study of terrorism and gender. This graphic platform makes the connections across all three articles easier to see and understand. Implementation of systemist figures makes the specific contexts, general similarities, and recurrent themes across cultures much more intelligible. All of that seems likely to advance African Studies, Gender Studies, and Political Science as fields which, along with many others, contribute insights to International Studies.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data was created in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | A more detailed introduction to systemism, which includes diagram structure and notation, appears in the article that introduces this special issue (Barnoschi 2025; see also Gansen and James 2024). |

| 2 | See James (2024a) for the rapidly expanding list of publications that apply the systemist graphic approach. |

| 3 | |

| 4 | The key words associated with the diagram in the VIRP archive are Boko Haram, education, feminist theory, Gender Studies, and Nigeria. |

| 5 | Multinational joint armed forces are armed force operatives from diverse agencies and neighboring states, acting in cooperation and tasked with combating terrorism in the region. |

| 6 | The acronyms R2P and RtoP are interchangeable. |

| 7 | The keywords listed for the diagram in the VIRP archive are African Studies, Boko Haram, Gender Studies, and UNHRC. This graphic also has been used for the purposes of the “bricolagic bridging” section of Gansen and James (2024). |

| 8 | The keywords for this item in the VIRP archive are Al Qaeda, jihad, radicalization, terrorism, and women. |

References

- Atran, Scott. 2003. Genesis of Suicide Terrorism. Science 299: 534–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, Albert. 1997. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control. New York City: W. H. Freeman. [Google Scholar]

- Barnoschi, Miruna. 2025. Systemism and International Studies. Social Sciences 14: 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, Gary S. 1968. Crime and Punishment: An Economic Approach, An Economic Approach. In The Economic Dimensions of Crime. Edited by N. G. Fielding, A. Clarke and R. Witt. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 13–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, Mia. 2013. In defense of honor: Women and terrorist recruitment on the internet. Journal of Postcolonial Studies 4: 150–95. [Google Scholar]

- Boli, John, and George M. Thomas. 1997. World Culture in the World Polity: A Century of International Non-Governmental Organization. American Sociological Review 62: 171–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukarti, Audu, and Rachel Bryson. 2018. Boko Haram’s Split on Women in Combat. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/334746639_Boko_Haram’s_Split_on_Women_in_Combat (accessed on 13 November 2024).

- Cook, David. 2005. Women Fighting in Jihad? Studies in Conflict and Terrorism 28: 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, Jessica. 2006. Women and terrorism in radical Islam: Planners, perpetrators, patrons. In Emerging Threats to Security in the 21st Century. Halifax: Dalhousie University. [Google Scholar]

- Editeur, Dunod, ed. 2023. Africa’s Critical Choices: A Call for a Pan-African Roadmap, 1st ed. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament. 2017. Joint Africa-EU Strategy, PE603849. Brussels: Directorate-General for External Policies, European Parliament Committee on Development. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2017/603849/EXPO_STU(2017)603849_EN.pdf (accessed on 13 November 2024).

- Gansen, Sarah, and Patrick James. 2024. The Visual International Relations Project. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of International Studies. Edited by Nukhet Sandal. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, Dee L. R., Edna I. Rawlings, and Roberta K. Rigsby. 1994. Loving to Survive: Sexual Terror, Men’s Violence, and Women’s Lives. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Idika-Kalu, Cecilia. 2021. Weaponised and Displaced Women in Mass Atrocities and the RtoP. Africa Development/Afrique et Développement 46: 45–68. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/48630970 (accessed on 13 November 2024). [CrossRef]

- Idika-Kalu, Cecilia. 2023. Women, education, and violence: How women displaced into camps in north-east Nigeria take up education. Development Policy Review 41: e12721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Internal Displacement Monitoring Center. 2021. Global Report on Internal Displacement (GRID). Geneva: IDMC, p. 18. [Google Scholar]

- International Organization for Migration. 2019. IOM Trains Law Enforcement Agents and Women Leaders on Gender-Based Violence in Northeast Nigeria. Available online: https://www.iom.int/news/iom-trains-law-enforcement-agents-and-women-leaders-gender-based-violence-northeast-nigeria (accessed on 13 November 2024).

- Jacob, Cecilia. 2020. R2P as an Atrocity Prevention Framework: Concepts and institutionalization at the global level. In Implementing the Responsibility to Protect. London: Routledge, p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- James, Patrick. 2024a. Visual International Relations Project. “Publications”. Available online: https://visualinternationalrelationsproject.com/publications/ (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- James, Patrick. 2024b. Visual International Relations Project. “Search Diagrams”. Available online: https://visualinternationalrelationsproject.com/search-diagrams/ (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Mahan, Sue, and Pamala L Griset. 2008. Terrorism in Perspective, 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- McNeely, Connie. 2012. World Polity Theory. In Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Globalization. Edited by George Ritzer. New York: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Savin-Baden, Maggi, and Clarie Howell Major. 2013. Qualitative Research: The Essential Guide to Theory and Practice, 1st ed. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simister, Nigel. 2010. Monitoring and Evaluating Capacity Building: Is It Really That Difficult? INTRAC Praxis Paper 23. Available online: https://www.intrac.org/app/uploads/2010/01/Praxis-Paper-23-Monitoring-and-Evaluating-Capacity-Building-is-it-really-that-difficult.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- True, Jacqui. 2003. Gender, Globalization and Postsocialism: The Czech Republic After Communism. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations General Assembly. 2010. A/64/864 14 July 2010, Report of the Secretary-General (English), Early Warning, Assessment, and the Responsibility to Protect, 64th Session, Agenda Items 48 and 114. New York: United Nations General Assembly. [Google Scholar]

- Visual International Relations Project. 2024. Available online: https://visualinternationalrelationsproject.com/ (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Werz, Michael, and Laura Conley. 2012. Climate Change, Migration, and Conflict. Available online: https://www.americanprogress.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2022/06/climate_migration.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).