Abstract

The research aims to explore the key components of an ideal grassroots-based digital urbanisation strategy for Türkiye. This exploration seeks to shed light on the most effective digital urbanisation strategies for Türkiye. Data were collected through a literature review, in-depth interviews with experts and psychometric testing methods, and analysed through psychometric assessment and document content analysis. The research indicates that an ideal grassroots-based digital urbanism strategy for Türkiye should focus on people, use technology to ease everyday activities, maintain personal data privacy, be adaptable, encourage diversity, provide freedom and opportunities, protect the city’s heritage, and strive for sustainability. By aligning with these essential elements, revisiting the national strategy documents crafted by the Turkish authorities to enhance the digitalisation process will allow future action plans to be grounded in a more practical framework.

1. Introduction

Digitalisation extends far beyond simply converting analogue information into a digital format; it involves the transformative influence of digital technologies on social, economic, environmental, and physical systems. This transformation includes the reimagining of product and service innovations, methods of creating value, and business models (Valenduc and Vendramin 2017; Spath et al. 2022). The roots of digitalisation trace back to the 1960s, marked by the widespread adoption of computers, which sparked a revolutionary shift in data management due to increased computing capabilities. The internet boom of the 1990s further accelerated digitalisation, significantly altering business operations and consumer habits (Terras 2011; Hahn 2021). In the present day, sophisticated technologies like artificial intelligence, big data analytics, and the internet of things have turned digitalisation into more than just a technical process; it is now a strategic opportunity. This change is reshaping the way people, companies, and communities engage with one another, having increasingly significant impacts on the economy, as well as on both natural and man-made surroundings.

Digitalisation has become a crucial element of the evolution of urban areas. Countries are investigating optimal methods to incorporate digitalisation to enhance community governance and ensure a higher quality of urban living for their inhabitants in the future. The swift progress of technological innovations and the transition of societies towards the digital realm have placed grassroots digitalisation strategies at the forefront of discussions in democratic nations. The primary aim of a grassroots-based digitalisation strategy is to deliver efficient, inclusive, and sustainable digital solutions that consider the socio-cultural requirements and desires of citizens (Vadiati 2022).

The shift towards digitalisation is prompting democratic societies around the globe to rethink their urban development plans, leading to a sense of uncertainty. A key issue is grasping the impact of digitalisation on social frameworks and creating a dependable base. Numerous nations are in search of a clear approach to harmonise the integration of technology and advanced digital tools into everyday urban life (Ray and Ojha 2024). To ensure an inclusive digital transformation, approaches centred on human needs must take into account various socio-economic groups and cultural aspects (Tan 2022). By enhancing stakeholder involvement and considering the needs of local communities, it is essential for each country to conduct community-focused, critical, comprehensive, and innovative research to craft its distinct digital urbanisation strategy.

Türkiye is among the nations aligning with this primary goal. Recently, the Turkish Government has crafted national strategy documents and action plans to enhance the management of the digitalisation journey. These include the Digital State Strategy (2024–2030), the National Artificial Intelligence Strategy (2021–2025), and the National Smart Cities Strategy (2024–2030) (DTO 2024; ÇŞİDB 2024). These national strategy documents, which prioritise the needs and expectations of Turkish society, are crucial for ensuring that the digitalisation process progresses in a manner that maximises social benefits within the country. They encompass a vision that supports not only technological advancements but also a data-driven government structure and public service delivery centred on community experience. Türkiye’s digitalisation strategy, while building on a strong foundation, requires more clarity, a comprehensive action plan, and a multidisciplinary approach. The strategy documents prepared by the Turkish Government on digitalisation have significant potential in the digital transformation process and are supported by a strong political will and centralised administrative structure. However, the uncertainties in the current documents, particularly the lack of clarity regarding objectives and responsibilities, restrict the feasibility of the strategies. Nonetheless, steps taken in areas such as open data policies and the integration of databases contribute to Türkiye’s goal of creating a data-driven public sector (OECD 2023). There is a need for evidence-based research using innovative methodologies that will enhance the effectiveness of the digital transformation process, improve the quality of public services, and elevate the living standards of citizens.

This study aims to explore the key components of an ideal grassroots-based digital urbanisation strategy for Türkiye. This exploration is significant as it highlights Türkiye’s position within the traditional–transition–digital society spectrum and the human–space interactions that Turkish society typically favours or shuns during the digital transformation. It is anticipated that the research outcomes will contribute to enhancing and establishing a more practical foundation for the existing national strategy documents and action plans that Türkiye has developed to guide the digitalisation process.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Digital Society and Dilemmas Arising in Society–Space Relations

The world is moving towards becoming a digital society. Widespread and diverse applications of digital technology bring about significant social and urban transformations (Runnel et al. 2013). This progress impacts numerous aspects of city life, influencing how individuals reside, work, and interact within urban environments (Cureton 2022). To comprehend this transformation more thoroughly, a host of researchers from social and spatial disciplines are investigating the ways in which digital technology shapes and interacts with geographical spaces (Ash et al. 2018). According to Datta (2018) and Chiappini (2020), it is not solely urbanisation that is undergoing a digital transformation; societies powered by digital advancements are also on the brink of a structural shift. A society progressing in this manner is termed a transition society.

Harvey (2012) discusses the concept of a ‘transition society’ as a period where people explore a genuine alternative to the digital world. This phase is characterised by efforts to transform urban areas into spaces that are non-commercial, democratic, fair, enjoyable, and meaningful for the community. The journey from a modern to a digital society is a multifaceted transformation propelled by technological advancements (Levin and Mamlok 2021). Within this evolving society, digitalisation opens up new avenues for employment and income, yet it also brings numerous challenges at every turn (Legner et al. 2017). As society embraces digitalisation, traditional structures and norms are undergoing changes, social roles are being redefined, and issues such as digital inequality, cyber-security, and the diverse digital skills of individuals are gaining importance (Eren 2016; Judijanto et al. 2024). Should digitalisation proceed at its present pace, the world might gradually edge closer to becoming a fully digital society (Dufva and Dufva 2019).

The concept of a ‘digital society’ describes a new social framework where technology is at the heart of daily life, with the internet and digital tools being integral to how individuals and groups connect. This society is characterised by the swift exchange of information across global networks at remarkable speeds (Redshaw 2020). It heralds a fresh era of techno-social living that is quite different from previous times (Andrushchenko et al. 2022). As noted by Schwarz (2021), Fuchs (2022), and Nassehi (2024), this marks a shift away from modernity. Some experts link the idea of a digital society with a future where freedoms might be curtailed, individuals are overseen by a central power, and the social fabric is tightly regulated (Frantz et al. 2020; Feldstein 2021). While the appealing aspects of digitalisation draw people in, the potential risks it poses also lead to certain concerns. At this juncture, it becomes crucial to explore the tensions people face between apprehension and optimism during the digitalisation journey and to comprehend the human–place connections that societies either embrace or shy away from at this digital crossroad.

2.2. Digital Urbanism, Smart Governance and Grassroots-Based Strategies

Digital Urbanism involves integrating digital technologies into city environments, significantly altering how urban spaces are constructed, experienced, and governed. At the heart of this idea is the use of data and technology platforms to boost efficiency, connectivity, and life quality (Moss et al. 2021). It explores how urban spaces and technology interact, examining the social and spatial impacts of these connections. The focus is on advancements in spatial planning driven by digital data and algorithms, with an emphasis on machine learning and artificial intelligence in urban decision-making (Coletta et al. 2017). Numerous examples from around the world can illustrate the tangible and feasible aspects of digital urbanisation. For instance, Singapore’s “Smart Nation” project optimises traffic flow within the city and reduces energy consumption by using data analytics and IoT technologies. This project has significantly reduced waiting times during peak hours by adjusting traffic lights with real-time data. Barcelona achieves energy savings and enhances city safety through streets equipped with smart lighting systems and sensors. Estonia’s e-government applications facilitate citizens’ access to public services, speeding up bureaucratic processes and increasing transparency. The smart water management system in Amsterdam supports environmental sustainability by using methods to collect and recycle rainwater, thus utilising water resources more efficiently.

In the sphere of digital urbanism, urban limits are influenced by the digital actions of tech companies, service providers, and users (Kitchin and Lauriault 2018). Some might say that digital urbanism has a more abstract nature (Kitchin et al. 2015; Shelton et al. 2015; Barns 2018; Leszczynski 2018). This approach offers a range of urban services, including employment, transport, consumption, governance, civic participation, and infrastructure (Rosenblat 2018). Within digital urbanism, cities become testing grounds where people incorporate technology into their everyday lives (Vadiati 2022). The effectiveness of introducing technological solutions in urban areas largely depends on public perceptions (Sokolov et al. 2019).

Smart Governance involves creatively using digital tools to manage city resources and engage citizens in decision-making processes (De Hoop et al. 2021). This concept encourages openness, involvement, and collaboration between local authorities, businesses, and the community. The aim is to create a governance system that is more effective and inclusive, moving away from traditional top-down methods (Azzari et al. 2018). At this stage, bottom-up strategies become prominent and take on greater significance (Eren and Henneberry 2021).

Grassroots strategies for governance emphasise empowering both local and national communities to participate in governance and shape urban development. This approach underscores the significance of citizens in crafting urban areas that mirror their needs and aspirations, rather than merely adhering to directives from above. Grassroots initiatives for smart governance frequently utilise digital platforms to organise and mobilise individuals, providing communities with a unified voice in both local and national governance (Li et al. 2022). Further research is necessary to identify grassroots strategies within digital urbanism (Sinclair and Bramley 2011). Angelidou (2014) proposes that to identify grassroots strategies, it is vital to first understand what is already established within a society and how it can be improved. The key principles in this process are selectivity, synergy, and prioritisation.

3. Research Methodology, Data Collection and Analysis

3.1. Research Methodology and Methods

In this study, data were collected by literature review, in-depth interviews with experts and psychometric test methods. A literature review was conducted by scanning academic articles, books and reports on digital urbanism, smart governance and grassroots-based strategies (Appendix A Table A1). Then, face-to-face in-depth interviews were conducted with thirteen experts working on the possible socio-spatial changes that innovative technologies may bring about in Türkiye (Appendix B Table A2). In these interviews, experts were asked for their opinions on the effects of smart technologies on human life in cities soon. The data gathered from a literature review and from conducting interviews with experts underwent document content analysis. This was carried out to identify the challenges that the people of Türkiye might encounter in the future and the types of decisions they will need to make concerning the relationship between humans and their environment (Appendix C Table A3). More importantly, the content analysis of documents obtained from the literature review and in-depth interviews with experts have revealed the dilemmas people face regarding their interactions with physical environments as digitalisation progresses. Six different dilemmas discovered as a result of expert interviews are presented below, each explained separately, along with the evidence gathered from document content analysis.

The first dilemma is finding harmony between physical and mental spaces. With the growth of remote work and online platforms, the dependency on physical spaces for work, socialising, and education has begun to wane (Mütterlein and Fuchs 2019). Physical spaces are increasingly seen as extensions of our digital experiences. This transformation has amplified the importance of mental space, where our thoughts and feelings reside. While physical spaces are still vital, digital environments offer numerous new ways to interact (De Vos 2020).

The second dilemma significantly impacts our capacity to share data and keep data private. This dilemma influences both societal and personal views on how digital data is stored, accessed, and managed (Thouvenin et al. 2018). The persistent nature of digital data makes keeping personal data private a difficult task. Digital footprints, social media activities, and online interactions often bring past memories back to the forefront, potentially infringing on privacy and compelling individuals to revisit past mistakes or uncomfortable situations (Vervier et al. 2017).

The third dilemma is balancing our physical selves with our digital engagements. The number of people becoming dependent on digital devices and accustomed to syncing with them is growing daily (Lyons et al. 2018). As we journey further into the digital world, the urge to stay continuously linked grows ever stronger. This results in a blend of comfort and discomfort, as we relish the benefits of online life while being concerned about possibly losing control over our daily routines.

The fourth dilemma lies between the robust places/goods and vulnerable places/goods. Robust places/goods are enduring, functional, and provide a sense of security. In contrast, vulnerable places/goods are technologically advanced but prone to rapid deterioration and lack durability. This raises issues about the resilience and sustainability of physical spaces that incorporate digital infrastructure (Rubio and Wharton 2020).

The fifth dilemma exists between the adaptability of digital tools and the constraints of physical spaces. Thus, the fifth dilemma involves single-function versus multi-functional spaces. Single-function spaces excel at their designated purpose but lack adaptability. Digitalisation allows spaces to serve multiple functions simultaneously. This can increase efficiency but might also cause distractions and lower productivity (Corbet et al. 2019).

The sixth dilemma is between natural and smart systems. The blending of nature and technology affects our lives and relationships. Natural systems include ecosystems, various species, and natural resources. Smart systems employ digital tools and data, such as automation and AI. This underscores the necessity to balance nature with technological progress. The convenience of smart systems often prompts individuals to reconsider their commitment to nature (Mondejar et al. 2021).

It is seen that as digitalisation advances, people face a range of dilemmas concerning their engagement with physical environments. These dilemmas should be viewed as interconnected elements rather than opposing forces (Lane 2018; Lub and Lub 2018; Mulder et al. 2019). A unique psychometric test was prepared based on these six dilemmas.

3.1.1. Psychometric Test

Psychometric tests are an important part of selection and assessment processes today. These tests are also called “trend research” (Hammond 2006). There are no right or wrong answers in psychometric tests. The answers given by the community (norm group) are checked to which side and to what extent, that is, their tendency. In these tests, the most important issue is to understand the participant’s degree of consideration for the options (Cripps 2017). A good psychometric test is one that has high validity and credibility, reads the group norms well and interprets the results. Validity means whether the test fully fulfils its purpose. Credibility means that the test is reliable, consistent and gives a complete measurement. If the test is repeated on the same group, a similar result should be obtained. The norm reference looks at a person’s interpretation success when performing the test. It is important that everyone who takes the test understands the same question in the same way and answers accordingly. It is expected that the test will choose a correct sample population and evaluate the results in terms of this sample population fairly and without prejudice (DeVon et al. 2007). Psychometric tests are used to save time and cost in research where face-to-face interviews are difficult and the sample size is large. Psychometric tests can be short, intense, or challenging. It should take no more than thirty minutes. These tests, which are mostly performed online, ask questions about how close the person feels to a certain preference (Mellett 2019). A psychometric test, which is developed to determine the relational preferences and tendencies of a society with technology and space in the digital urbanisation process, can be an innovative tool to analyse the technological future (DiCerbo et al. 2017).

Utilising insights gathered from document analysis and interviews with experts, a psychometric test tailored for this research was crafted. This test, designed in line with the aforementioned criteria, comprises fifty-eight questions divided into six main headings and can typically be completed in about twenty minutes. The main headings of the test, the number of questions under each heading, and the psychometric assessment specific to each topic are presented in Table 1 below.

Table 1.

The main headings of the psychometric test, how many questions there are under each heading, and the psychometric analysis specific to each topic.

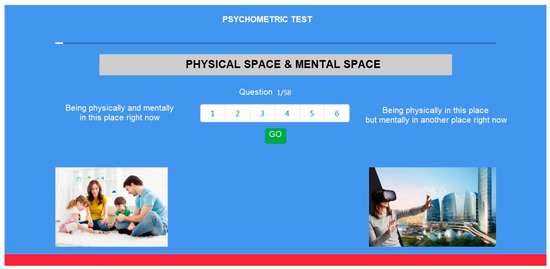

The questions asked under which headings in the psychometric test are given in Appendix D in detail in Table A4, Table A5, Table A6, Table A7, Table A8 and Table A9. The psychometric assessment, designed for online engagement, begins with a participant information screen. This screen displays the research title, outlines its scope, explains the principles of scientific research ethics, provides the researchers’ contact details, and features the logo of the university conducting the study. After clicking “I have read all the information and I want to participate in the test voluntarily”, participants can start the test. Figure 1 shows an example of what the psychometric testing environment might look like. In the example provided, you will notice a main dilemma heading on a grey background positioned towards the top centre of the screen. Beneath this title, there are two choices displayed on either side. Underneath these options, images are shown to help the participant better understand the question. To continue with the test, the participant selects one of the numbers from one to six in the middle of the screen, according to which side s/he feels closer to, and then clicks the progress button to move on to the next question.

Figure 1.

An example of the psychometric test environment screen view. Source: (prepared by the authors 2024).

3.1.2. Psychometric Assessment

After the psychometric test software was prepared, it was initially pilot-tested on a subset of 30 people. The pilot test run helped fine-tune the psychometric assessment tool prior to its wider release, making it possible to spot and fix any statements that participants found unclear or confusing. Subsequently, the revised psychometric test was distributed widely across Türkiye. The tests were conducted all over Türkiye using various avenues like universities, student groups, online chat forums, professional business networks, personal connections, and social media platforms. This method of distribution may have resulted in missing representation of groups from certain geographical regions in the country and excluding some demographic groups with low digital skills. However, due to time and financial constraints, this distribution method had to be adopted in the research.

The psychometric test was applied online for 6 months to individuals aged 18–65 with an official ID number living in Türkiye. Due to time and cost constraints, not all nationals completed the test. The psychometric test was applied to 3636 selected people. A deviation of ±1.8 in the 95 percent confidence interval was defined as the “margin of error”. To achieve Türkiye-wide results, it is aimed to reach a certain number of participants from every geographical region of the country. A number of people were contacted to represent the population in each geographical area with a specific percentage, making sure there was an even regional distribution of participants.

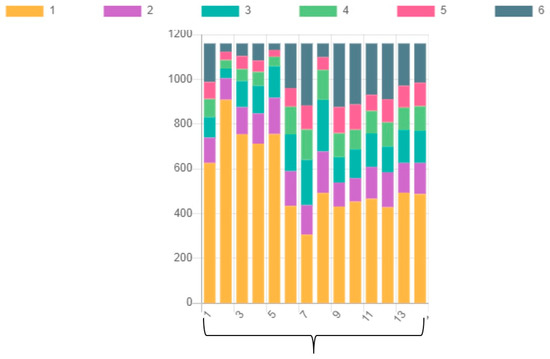

The data obtained with the test were analysed with the psychometric assessment method. First, the validity of the answers given to the test was checked with several statistical techniques. To measure test–retest reliability, a random sample of 100 from 3636 participants was selected and asked to complete the test again after twenty days. Statistical analyses were made using the “SPSS for Windows 25.0” program. The reliability and validity of the test were measured using the following analyses. The choice patterns for fifty-eight questions in the test were looked at, and if more than 80 percent of people picked the same answer, that answer was removed from the analysis. To calculate the Discrimination Coefficient, the total score for each participant was calculated and ranked. The answers in the top 25 percent and the bottom 25 percent of the total scores were determined and the average score for each question of these two sections was calculated. The difference between the two average scores is the discrimination coefficient for each question. The larger the difference, the greater the discrimination coefficient. A minimum discrimination coefficient value of 0.5 was accepted in the answers, and answers with a higher coefficient value were not included in the analysis. Exploratory Factor Analysis was used to understand the factor structure of the test. Factor extraction was carried out using main-axis factoring. Cattell’s scree plot analysis and an eigenvalue greater than 1 determined the number of factors retained in the test. Content Validity Ratio formula was used to evaluate content validity. In the formula “CVR = (ne − N/2) ÷ N/2”, ne represents the number of participants who answered “essential” for each question of the test, and N represents the total number of participants. The CVR value was greater than “0 (zero)” in 85 percent of the answers given to the test. This showed that most of the participants found the questions important. The internal consistency of the test was evaluated with the Cronbach’s Alpha Technique, the answers with an α value below 0.7 were deleted and not included in the analysis. The Corrected Item-Total Correlation technique, which is used to compare the correlation coefficient between the scores of each question of the test and the scores of the remaining questions, was used, the answers with a value of 0.3 or less were deleted and not included in the analysis. As a result of the statistical validity checks, 2476 of the 3636 answers given to the test were not evaluated, and the psychometric assessment was carried out on 1160 valid answers.

The answers to each question in the test were graded as 1–2–3–4–5–6, and the answers were scored as follows:

If 1 is marked (−3) points

If 2 is marked (−2) points

If 3 is marked (−1) points

If 4 is marked (+1) points

If 5 is marked (+2) points

If 6 is marked (+3) points

In the psychometric test, scoring 1 or 2 nudges Türkiye towards a more traditional (or modern) society. Scoring 3 or 4 leans Türkiye towards a transitional society, while scoring 5 or 6 shifts Türkiye closer to a digital society.

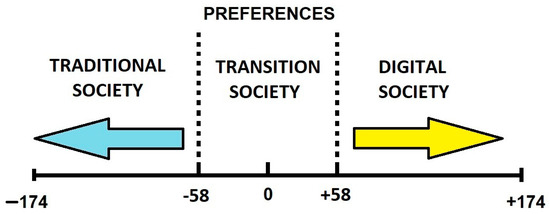

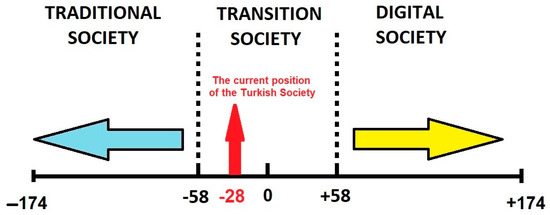

The answers given to the psychometric test questions were calculated according to the maximum value of 58 × 3 = 174 and the direction in which the individuals tended was analysed within a scoring scale of ±174. The answers given were grouped under 6 main headings and evaluated. Should the combined outcomes of the responses to each question in the test yield a negative value, it indicates a preference and inclination towards traditional society corresponding to that negative value. Conversely, if the total result is a positive value, it suggests a preference and leaning towards digital society (Figure 2). Since there cannot be a clear distinction between traditional and digital society and there are intertwined situations, an intermediate period called transitional society was defined. To reach meaningful and distinctive results between binary and multiple variables, comparative and cross-analysis were performed on the answers given to the test. Separate analyses were made according to age, gender, and geographical region, respectively, under each main heading. The age ranges of ‘18–25’, ‘26–39’ and ‘40–65’ were used. Men and women were used as the gender categories. As the geographical region category, seven geographical regions of Türkiye, Mediterranean, Eastern Anatolia, Aegean, South-eastern Anatolia, Central Anatolia, Black Sea, and Marmara were used (Figure 3). Consequently, by analysing the responses provided by the participants to the test queries, it was assessed how Türkiye aligns with either a traditional, transitional, or digital society and the direction in which participants are inclined toward various socio-spatial dilemmas.

Figure 2.

Psychometric test scoring scale. Source: (prepared by the authors 2024).

Figure 3.

Geographical regions of Türkiye (NFKU 2024).

4. Results

In this section, the results of the psychometric assessment are given. The analysis was broken down into six key categories: the Physical vs. Mental Space Dilemma, the Sharing vs. Privacy Dilemma, the Natural Body vs. Body Dependent on Digital Dilemma, the Robust vs. Vulnerable Places/Goods Dilemma, the Single-Function vs. Multi-functional Space Dilemma, and the Natural vs. Smart Systems Dilemma. These explore potential future interactions between society and space, along with those aspects that Turkish society seems inclined to avoid.

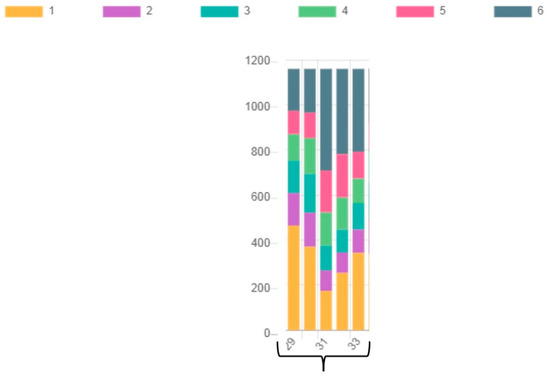

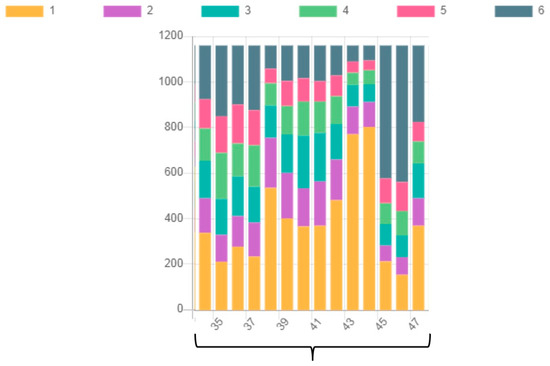

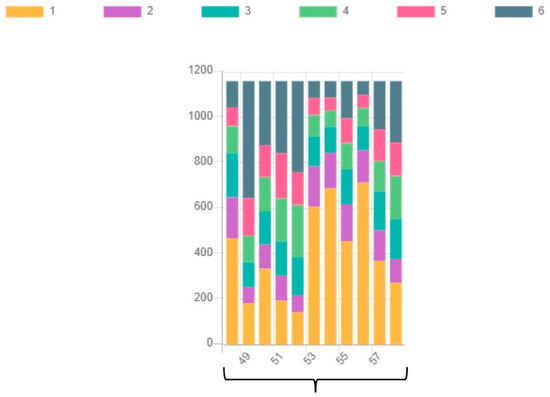

Two separate figures are presented for each subheading in this section. The first figure shows the total result of the answers given by all participants to questions related to a certain dilemma. It can be understood from the first figure to which side of a certain dilemma the participants’ answers are closer. The second figure shows the average score given by all participants for each question related to a certain dilemma. The figures presented in this section gain meaning when examined together with Table A4, Table A5, Table A6, Table A7, Table A8 and Table A9 presented in Appendix D: Questions in the Psychometric Test.

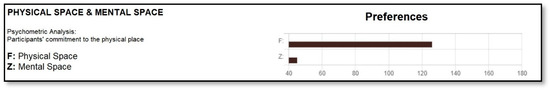

4.1. Physical Space and Mental Space Dilemma

In the physical space and mental space dilemma, the commitment of the participants to the real (physical) space was analysed. Participants’ physical space preferences scored an average of 126 points, while their mental space preferences scored an average of 45 (Figure 4). This result shows that the participants prefer being in a physical place 2.8 times more than being in a mental place. In other words, Turkish society is almost three times more inclined and dependent on physical space than mental (virtual) space.

Figure 4.

The total result of the answers of all participants to 14 questions under the title of physical space and mental space dilemma.

It is seen that the participants prefer physical space in individual activities and mental space in communication technologies (Figure 5). Turkish people often seek an active lifestyle by engaging in tangible personal activities. However, when it comes to interacting with others, they prefer to use technology and focus on mental engagement. According to this result, digital urbanisation should work to provide a more inclusive and interactive social life by balancing individuals’ physical and mental space needs. For example, in a city, outdoor sports areas can be integrated with digital platforms, allowing users to track their physical activities and engage in social interactions. Additionally, digital urbanisation can enable local people to organise events virtually while suggesting suitable venues for face-to-face meetings to strengthen social bonds. In this way, digital urbanisation can offer a more holistic life experience by considering both physical and mental spaces; it can play a role in enriching urban life by supporting individuals’ pursuit of physical activity and increasing digital interaction.

Figure 5.

Graph showing which average score all participants gave to which question under the title of physical space and mental space dilemma.

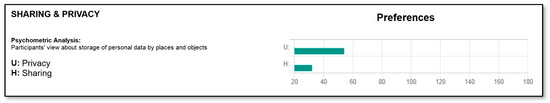

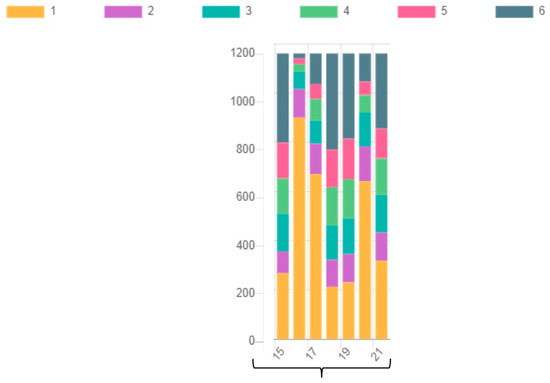

4.2. Sharing and Privacy Dilemma

Participant opinions about the storage of personal data by space and objects in the sharing and privacy dilemma were analysed. While the participants’ preferences for sharing received an average of 54 points, their preferences for privacy scored an average of 32 points (Figure 6). This result shows that Turkish people do not want their movement data in a space to be recorded by that space.

Figure 6.

The total result of the answers given by all participants to 7 questions under the title of sharing and privacy dilemma.

After looking at the graph that displays the average scores that participants assigned to each question under the ‘sharing & privacy dilemma’ heading, it becomes clear that people feel uneasy about the venue collecting their personal information. They generally prefer a place that keeps data private (Figure 7). However, when the participants are given the right to control and store their personal data in person, the participants are willing to choose the sharing place. According to this result, digital urbanisation should respond to individuals’ demands to protect and control their personal data. For example, digital city applications can offer centralised platforms where users can securely store and manage their data. These platforms increase transparency by allowing users to see what information is collected and how it is used. Digital loyalty programs developed for local businesses can be designed in a way that gives users the right to share and manage their own data. Additionally, personal data protection training offered at community centres can help increase citizens’ digital literacy, enabling them to make informed choices.

Figure 7.

Graph showing which average score all participants gave to which question under the sharing and privacy dilemma.

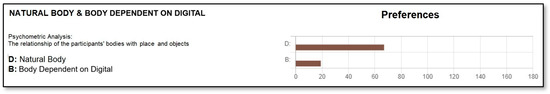

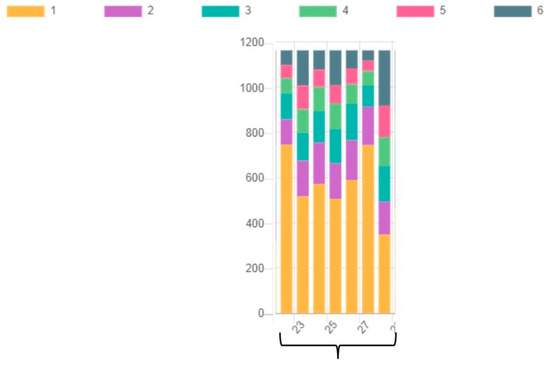

4.3. Natural Body and Body Dependent on Digital Dilemma

In the natural body and body dependent on the digital dilemma, the relationship of the participants’ bodies with space and objects was analysed. The participants’ natural body preferences scored an average of 67 points, while their dependent body preferences scored an average of 19 points (Figure 8). This result shows that with a significant difference, the participants tend not to want any apparatus to be attached to their bodies and to have their biological bodies connect with the space.

Figure 8.

The total result of all participants’ answers to 7 questions under the title of natural body and body dependent on digital dilemma.

The graph analysis, which illustrates the average scores given by all participants to each question under the theme of the natural body versus body dependent on the digital dilemma, indicates that people are concerned with maintaining their bodies in their natural form. Again, the participants want to benefit from technology in their daily routine work (Figure 9). This result reveals that Turkish society prefers the facilitating side of technology and does not generally focus on its controlling and intervening side. According to this result, digital urbanisation should aim for integration with technology while preserving the natural lifestyles of society. For example, smart park systems can be used to increase green spaces; these systems can optimise the maintenance of parks while enhancing people’s interaction with nature. Digital bicycle rental systems integrated with health applications can help individuals adopt a healthy lifestyle. Smart waste management systems can increase environmental awareness by promoting recycling. Digital market platforms supporting local producers can bring communities together while also ensuring economic sustainability.

Figure 9.

Graph showing which average score all participants gave to which question under the natural body and body dependent on digital dilemma.

4.4. Robust Places/Goods and Vulnerable Places/Goods Dilemma

The durability of places and goods used by the participants in the robust places/goods and vulnerable places/goods dilemma was analysed. The robust places/goods preferences of the participants received an average of 100 points, while their vulnerable places/goods preferences scored an average of 66 points (Figure 10). The outcome clearly indicates that people generally favour stable, lasting, and robust environments. In other words, Turkish society appears to be somewhat distant and cautious about the digital and delicate elements of the spaces they occupy.

Figure 10.

The total result of the answers of all participants to the 5 questions under the title of robust and vulnerable places/goods dilemma.

The figure illustrating the average scores given by all participants to each question under the theme of the robust places/goods and vulnerable places/goods dilemma reveals that people value the robustness and durability of their living spaces. Nonetheless, Turkish society is open to the concept of adapting and altering their environment to suit their needs and preferences (Figure 11). According to this result, digital urbanisation should offer solutions that make living spaces in Turkish society more functional and personalised. For example, digital home systems may allow users to optimise their energy consumption while also customising their living spaces according to their needs. Through mobile applications, community members can evaluate the areas around them and contribute to the improvement of shared living spaces by making suggestions. Digital city applications can integrate transportation systems, facilitating citizens’ daily lives while creating a city structure resilient to environmental changes with durable infrastructures.

Figure 11.

Graph showing which average score all participants gave to which question under the robust and vulnerable places/goods dilemma.

4.5. Single-Function Space and Multi-Functional Space Dilemma

In the single-function space and multi-functional space dilemma, the issue of how the participants use the place for what was analysed. While the participants’ single-space preferences received an average of 29 points, their multi-functional space preferences received an average of 30 points (Figure 12). Based on these findings, Turkish society takes a middle-ground approach to this issue and does not lean heavily towards either extreme.

Figure 12.

The total result of the answers given by all participants to 13 questions under the single-function space and multi-functional space dilemma.

The figure illustrating the average scores participants assigned to each question regarding the single- versus multi-functional space dilemma reveals that people in Türkiye have a personal preference for owning spaces and items for their private use. However, they are also open to the concept of sharing spaces and belongings for public use when needed (Figure 13). According to this result, digital urbanisation should support the understanding of private property in Turkish society while also encouraging a culture of sharing. For example, through digital sharing platforms, individuals can share unused items or vehicles with their neighbours, thereby achieving economic gains and preventing waste. Additionally, by developing digital reservation systems for shared spaces, more effective use of places such as parks or sports areas can be ensured. Shared office spaces provide an affordable working environment for freelancers while also creating opportunities for community building.

Figure 13.

Graph showing which average score all participants gave to which question under the single-function space and multi-functional space dilemma.

4.6. Natural Systems and Smart Systems Dilemma

The significance of technology in participants’ lives in the natural systems and smart systems dilemma was analysed. Participants’ natural system preferences scored an average of 78 points, while their smart system preferences scored an average of 51 points (Figure 14). Based on this outcome, it seems that Turkish society has chosen to stick with the current way of life and continue moving forward naturally.

Figure 14.

Total results of all participants’ answers to 11 questions under the natural systems and smart systems dilemma.

The graphic analysis illustrating the average scores participants assigned to each question regarding the natural systems versus smart systems debate shows a lack of complete trust in technology for decision-making (Figure 15). People in Türkiye prefer the human mind to operate in its natural state, leaning more towards biological systems. However, they are open to using technology, specifically smart systems, to tackle issues that could harm human life, like illnesses and disabilities, or those that demand a lot of effort. According to this result, digital urbanisation should use digital systems to enhance health and quality of life while preserving the natural lifestyles of Turkish society. For example, smart health monitoring devices can enable early diagnosis of diseases by tracking individuals’ health conditions in real time. Smart transportation systems designed for individuals with disabilities can support their independent living by facilitating access to public transportation. Virtual support services offered through mobile applications can be used to ease the daily tasks of elderly individuals.

Figure 15.

Graph showing which average score all participants gave to which question under the natural systems and smart systems dilemma.

5. Conclusions and Discussion

5.1. How Can the Relationship of Turkish Society with Space Be Best Shaped in the Process of Moving Towards a Digital Society?

The research has shown that in the traditional–transition–digital society divide, Türkiye stands at the transition society section with a score of [−72 + 44] = −28 as of today. It can be seen that Türkiye is no longer a traditional (or modern) society, but it is in the early stages of the transition society (Figure 16). In the psychometric test, the average of participant preferences in the direction of ‘traditional society’ under six main headings is [(−126 – 32 – 67 – 100 – 29 − 78) ÷6] = −72. In the psychometric test, the average of participant preferences in the direction of ‘digital society’ under six main headings is [(45 + 54 + 19 + 66 + 30 + 51) ÷6] = +44.

Figure 16.

Where Turkish society stands today in the traditional–transition–digital society divide. Source: (prepared by the authors 2024).

The findings of the research provide some clues on how to build urban environments that relate to the cultural codes and value system of the Turkish society in the process of moving towards a digital society. As of 2024, some generalisations that can be reached based on the weighted opinion and tendency of the society are given below.

Society tends to favour tangible experiences and prefers to uphold social interactions through direct, face-to-face engagement within the same environment. The Turkish community is generally averse to being physically present in one location while mentally occupied elsewhere. In Türkiye, both women and men have the common idea of” keep my personal data with me, do not share it with others!”. In Turkish society, there is a strong preference for places to keep personal data private. People believe that personal information should be accessible only to its owner and that technology should be used in a private and secure manner. There is a general hesitance towards creating a database of personal data that is available and openly shared with everyone. The community values the natural state of their bodies and the ability to move freely without external influence. They prefer to maintain personal autonomy over their mental space. The idea of merging technology with the human body is not warmly received. People are against spaces that adapt their shape according to bodily movements or establish a digital link between the body and the environment. There is a general avoidance of discussions about embedding tiny technological devices into the human body or carrying items that constantly transmit data within the body.

In Turkish society, there is a preference for big, roomy homes with sturdy, long-lasting surfaces in both living and working spaces. People tend to shy away from using soft, delicate, and digital materials in these environments. They appreciate having a clear distinction between work and home life yet are open to designing workspaces within their homes. There is a belief that living and working spaces can be both permanent and adaptable. Activities like living, working, and enjoying leisure time can occur in the same location or in separate ones. Business meetings might be held in one consistent spot or in various changing locations. The society embraces the idea of physically reaching spaces through movement and accessing digital spaces through thought. However, there is a lack of trust in digital technology for making decisions, with a preference for people to hold decision-making power. They believe that human willpower should remain as it is. At the same time, there is a desire for smart technology to tackle issues affecting human life and requiring effort, using these systems to simplify life. Energy conservation and recycling are expected to be managed by smart systems, though there is a cautious stance on letting smart devices and robots handle all household duties. The idea of all objects being interconnected and interactive is met with some hesitation.

The study also includes findings based on gender, age, and location. It found that men and women in Türkiye generally have similar views on digital urbanism, with no major gender-based differences in preferences. The study indicated that people aged 40 and above in Türkiye tend to align more with traditional (or modern) society, whereas those under 40 lean towards a digital society. If Türkiye continues its strong push towards becoming a digital state, which has been ongoing since 2008, it might soon shift away from being a transitional society and start to show more characteristics of a digital society. The research highlighted that each region in Türkiye has its own preferences when dealing with the socio-spatial challenges brought on by the digital shift. The results showed that the Aegean, Mediterranean, and Central Anatolia regions are more inclined towards traditional society, while South-eastern Anatolia and Eastern Anatolia are more inclined towards a digital society.

5.2. What Are the Key Components of an Ideal Grassroots-Based Digital Urbanism Strategy for Türkiye?

The key components of an ideal grassroots-based digital urbanisation strategy for Türkiye are as follows:

- In Türkiye, people generally do not focus on the controlling and intrusive aspects of technology. They prefer the aspects of technology that make daily life easier. Therefore, the country’s strategy for digital urbanisation should focus on tech that boosts convenience, ramps up efficiency, and takes care of regular chores automatically.

- Although there is a general unease in Turkish society about personal data collection, this discomfort eases if individuals can control and manage their own information. Therefore, Türkiye’s strategy for digital urbanisation should protect personal data ownership and establish clear, honest policies for data gathering and usage.

- Turkish society emphasises that people are not machines but intelligent beings with feelings and thoughts. Thus, Türkiye’s digital urbanisation strategy should prioritise societal needs and aspirations, adopting a human-focused approach.

- Recognising that cities evolve through the contributions of their inhabitants, Turkish society suggests that Türkiye’s digital urbanisation strategy should be adaptable and flexible, catering to the ever-changing demands and technologies of urban life.

- Believing that cities are places where diversity thrives, Turkish society recommends that Türkiye’s digital urbanisation strategy should aim to foster an environment where different cultures and lifestyles coexist, creating a sense of belonging for all.

- Turkish society views cities as arenas of interaction, exploration, freedom, and opportunity. Hence, Türkiye’s digital urbanisation strategy should encourage creativity and innovation, supporting the development and exchange of fresh ideas within urban areas.

- Understanding that cities, people, communities, and civilisations have their own stories, Turkish society advises that Türkiye’s digital urbanisation strategy should connect individuals with their heritage and ensure the city’s narrative is preserved for the future.

- Aware that cities are part of the natural world, Turkish society suggests that Türkiye’s digital urbanisation strategy should integrate eco-friendly technologies and aim to create a sustainable urban environment.

To sum up, studies suggest that an ideal grassroots-based digital urbanisation strategy for Türkiye should focus on people, use technology to ease everyday activities, maintain personal data privacy, be adaptable, encourage diversity, provide freedom and opportunities, protect the city’s heritage, and strive for sustainability. By aligning with these essential elements, revisiting the national strategy documents crafted by the Turkish authorities to enhance the digitalisation process will allow future action plans to be grounded in a more practical framework.

Türkiye’s digitalisation strategy documents partially include the fundamental components of an ideal grassroots-based digital urbanisation strategy as outlined above, but more depth and scope are needed in some areas. Firstly, the current strategies emphasise the potential of technology to facilitate daily life, but there is a noticeable lack of concrete implementation plans and focus on user experiences to achieve this goal. Additionally, concerns regarding personal data protection are included in the strategies, yet clearer and more transparent policies need to be developed to strengthen individuals’ control over their data. Although a human-centred approach emerges as a fundamental element of the strategies, it is important to provide flexibility and adaptation to better reflect the needs of different segments of society. Moreover, it appears necessary to take more concrete steps in promoting cultural diversity and preserving the identity of cities. Ecological sustainability is mentioned in the existing documents, but more innovative and integrated solutions need to be developed to achieve this goal. In this regard, it would be beneficial to revise Türkiye’s digitalisation strategy documents by adopting a more holistic and detailed approach to better meet the needs and expectations of Turkish society.

To effectively communicate the key findings of this research to the public, a detailed communication strategy should be created. To start, using infographics and short videos across various media platforms such as television, radio, and social media can help reach a broad audience. Additionally, hosting events at local community centres and universities can facilitate direct interaction with stakeholders and the public. During these gatherings, presenting the study’s outcomes and encouraging feedback will help gauge the community’s interests and concerns. This method can enhance public engagement with digital urbanisation efforts by fostering both information sharing and participation. By integrating feedback loops and regularly conducting this psychometric test within Turkish society, the national digital urbanisation strategy can continuously evolve. This will ensure that the implementation stays aligned with Türkiye’s changing technological and social landscape.

Türkiye’s strategy for grassroots digital urbanisation mirrors trends seen across the globe. In the USA, there is a push for personal control over data, which matches Türkiye’s focus on data ownership. Over in Europe, digitalisation is driven by human-centred methods, showing that both areas value individual thoughts and feelings (Park and Yoo 2023). Similarly, India’s blend of traditional values with digital advances reflects Türkiye’s own societal transition, while China’s centralised data management and surveillance issues echo privacy concerns in Türkiye (Murray and Datta 2020; Zhao et al. 2023). Singapore’s emphasis on social involvement, despite its focus on sustainability and efficiency in urban digitalisation, supports Türkiye’s findings (Tan 2022). In the Global South, development is influenced by wider socio-economic contexts, highlighting the need for Türkiye to create adaptable strategies that address local needs (Datta 2023). As Türkiye works towards a digital urbanisation strategy that is both human-centred and sustainable, it must also consider the varied demands stemming from global social and cultural differences, as well as local dynamics.

5.3. Limitations of the Study

This document offers valuable insights into the essential elements of an ideal grassroots-based digital urbanisation strategy for Türkiye and the application of psychometric digital urbanisation assessments, but it does have some drawbacks. The pilot test was conducted with only 30 individuals, which might not be enough to fully validate the test; a bigger and more varied group could have given a better representation of the test’s perceptions. Even though the psychometric test has shown its reliability and validity through statistics, the fact that only 1160 out of 3636 participants provided valid results could lead to questions about how representative the sample is. Efforts to achieve geographical balance are crucial, yet the study might have missed out on representing certain demographic groups, such as those from rural areas. The online nature of the test might have excluded some people, like those with low digital skills. The limited consideration of social and psychological factors that could affect participants’ responses might restrict how widely the results can be applied. In the future, research might explore in greater detail the essential elements of an ideal digital urbanisation strategy that is rooted in grassroots efforts for society. To do this, a larger and more representative sample should be used to capture opinions from people of diverse socio-economic and cultural backgrounds. Furthermore, incorporating various data collection methods, like in-depth interviews and workshops, and including qualitative data in the analysis could provide a richer understanding of participants’ experiences in digital urbanisation. Finally, comparative studies in different regions could explore whether digital urbanisation strategies vary in local contexts. Such research would offer a stronger data foundation for policymakers, improving the effectiveness of their actions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.E.; methodology, F.E.; software, F.E. and K.Ç.; validation, F.E. and K.Ç.; formal analysis, F.E. and K.Ç.; investigation, F.E. and K.Ç.; resources, K.Ç.; data curation, K.Ç.; writing—original draft preparation, F.E. and K.Ç.; writing—review and editing, F.E.; visualization, F.E. and K.Ç.; supervision, F.E.; project administration, F.E.; funding acquisition, F.E. and K.Ç. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The paper was produced from Kübra ÇAY’s Master’s Thesis titled “Possible Changes in the Relationship of Turkish Society with Space in the Transition to Digital Society: A Social Tendency Survey” conducted at Konya Technical University Institute of Graduate Studies under the academic supervision of Assoc.Prof.Dr. Fatih EREN. This MSc thesis was financially supported by the Scientific Research Projects Coordinatorship of Konya Technical University with the project numbered 191021029. In addition, the theoretical framework of this paper has been produced by utilizing the scientific research project titled “The spatiality of Istanbul city from the eyes of a digital platform” conducted under the code MAB-2023-44885 at Istanbul Technical University, with Assoc.Prof.Dr. Fatih Eren as the project manager. The funding sources had no role (were not involved) in the production of this paper.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This article does not require an ethics committee approval and/or legal/special permission. In the study, a psychometric test consisting of 58 questions was used as a data collection tool. The prepared psychometric test was administered online to individuals aged 18–65 living in Türkiye. The psychometric test was filled out only by those who voluntarily agreed to complete the test and be part of the study, and who marked the official consent/signature box. No personal sensitive information was requested from the participants in the psychometric test. The results of the psychometric test were analysed collectively to understand general societal trends rather than individually.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Since the data used in the study were collected and analysed with a copyrighted psychometric test software developed originally, the data set is not suitable for sharing with third parties or open access.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Document Analysis

Table A1.

Document analysis based on key concepts before conducting in-depth interviews with experts and developing the psychometric test.

Table A1.

Document analysis based on key concepts before conducting in-depth interviews with experts and developing the psychometric test.

| Digitalisation | Digital Urbanism | Digital Society and Smart Governance | Grassroots-Based Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ash et al. (2018) | Barns (2018) | Angelidou (2014) | Leszczynski (2018) |

| Cureton (2022) | Chiappini (2020) | Shelton et al. (2015) | Vadiati (2022) |

| Datta (2018) | Coletta et al. (2017) | De Hoop et al. (2021) | Sinclair and Bramley (2011) |

| Runnel et al. (2013) | Moss et al. (2021) | Azzari et al. (2018) | Li et al. (2022) |

| Chiappini (2020) | Kitchin and Lauriault (2018) | Redshaw (2020) | Schwarz (2021) |

| Harvey (2012) | Kitchin et al. (2015) | Andrushchenko et al. (2022) | Fuchs (2022) |

| Levin and Mamlok (2021) | Vadiati (2022) | Mütterlein and Fuchs (2019) | Nassehi (2024) |

| Legner et al. (2017) | Barns (2018) | De Vos (2020) | Frantz et al. (2020) |

| Judijanto et al. (2024) | Leszczynski (2018) | Thouvenin et al. (2018) | Feldstein (2021) |

| Dufva and Dufva (2019) | Rosenblat (2018) | Vervier et al. (2017) | |

| Sokolov et al. (2019) | Lyons et al. (2018) | ||

| Rubio and Wharton (2020) | |||

| Corbet et al. (2019) | |||

| Mondejar et al. (2021) |

Source: Produced by the authors (2024).

Appendix B. In-Depth Interviews with Experts

Table A2.

Basic characteristics of the experts who were interviewed in-depth to produce the psychometric test content.

Table A2.

Basic characteristics of the experts who were interviewed in-depth to produce the psychometric test content.

| Respondent Code | Profession | Age Range | Gender | Education Background | Years of Working Experience | Field of Expertise |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G1 | Chairman of the Futurists Association High Advisory Board | 40–50 | Male | Industrial Engineering | 21 | Digital strategy, development of digital assets, digital transformation, digital urbanism |

| G2 | Member of the Supervisory Board of the Futurists Association | 50–60 | Male | Entrepreneurship | 35 | Entrepreneurship, market research and analysis, futurism, digitalisation |

| G3 | Young Futurists Chairman of the Board | 30–40 | Female | Political Science and International Relations | 12 | Blockchain, sustainability, web3, futurism, digital leadership, management and organisation, digital society |

| G4 | Industry 4.0 Digital Transformation Association Project Coordinator | 50–60 | Male | Industrialist | 32 | Industry 4.0, industry–university–private sector ecosystem, digital transformation, digitalisation |

| G5 | Software engineer | 40–50 | Female | Software Engineering | 18 | Advanced technology solutions, global software services, telecommunications, smart city |

| G6 | Futurist and Strategist | 50–60 | Male | Strategy Expert | 37 | Internet, media, and information technologies, international strategic analysis, platform urbanism |

| G7 | Researcher, Author, and Trainer | 50–60 | Male | Nuclear Energy Engineering | 35 | Quantum physics and time, mythology, paganism, digital society |

| G8 | Strategist and futurist | 60–70 | Male | Electrical Electronics Engineering | 37 | Futurism, storytelling, strategy development, digital transformation, smart governance |

| G9 | Film producer, screenwriter, and director | 60–70 | Male | Education and Linguistics | 27 | Creative content production, scriptwriting, digitalisation, futurism, grassroots-based strategy |

| G10 | Academician and Author | 50–60 | Female | Political Science and International Relations | 37 | International relations, terrorism and security, political psychology, smart governance |

| G11 | Strategic Communications Consultant | 60–70 | Male | Journalism and Public Relations | 46 | Strategic communication, reputation management, corporate social responsibility, grassroots-based strategy |

| G12 | Journalist and Writer | 70–80 | Male | Journalism and Public Relations | 42 | Sociology, history, politics, grassroots-based strategy |

| G13 | Environmental Scientist | 40–50 | Male | Geological Engineering | 30 | Ecology, conservation biology, economics, system theory, complexity, platform urbanism |

Source: Produced by the authors (2024).

Questions posed to experts during in-depth interviews:

- What is your individual, social and spatial predictions about the cities of the future?

- What dimension do you think the society–space relationship will gain in the near future?

- In what ways will the technologies of the near future enter the cities (indoor and outdoor) and the daily life of individuals?

- How are the smart technologies produced today integrated into the space?

- What dilemmas will people be stuck between in the cities of the near future, indoors and outdoors? What choices will people be forced to make?

- In what way and how will the smart technologies of the future change people’s lifestyles?

- How will the interior and exterior spaces be shaped and used in the near future?

- What kind of demands will people have in indoor and outdoor spaces in the cities of the near future?

- What could be the dark sides of technology to which Turkish society will react negatively and act shyly?

Appendix C. Content Analysis

Table A3.

Example of content analysis applied to verbal and written texts.

Table A3.

Example of content analysis applied to verbal and written texts.

| Text Type | Paragraph/Quote | Exploration of Dilemma | Explanation of Dilemma | Tendency/Preference in Psychometric Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Written Text | “Real space is the nature, the cosmos, the physical space on which one lives. Mental space, which includes logical and formal abstractions, is imagined space. The primary space is real and the secondary space is imaginary” (Barns 2018) | Physical Space and Mental Space | “Spatial attachment refers to the ties that people share with places” (Vadiati 2022) | Participants’ commitment to the physical place |

| Verbal Text | “When digital memory is articulated with tangible and physical space, memory comes to life in a space. Technology allows space to cumulatively store individual and social memory. Some places now have a digital memory.” From the interviews | Sharing and Privacy | “Having your data in the hands of others, such as the government or a company, may be harmful to democracy and human rights.” From the interviews | Participants’ view about storage of personal data by places and objects |

Source: Produced by the authors (2024).

Appendix D. Questions in the Psychometric Test

Table A4.

Questions about the physical space–mental space dilemma in the psychometric test.

Table A4.

Questions about the physical space–mental space dilemma in the psychometric test.

| Being physically and mentally in this place right now | QUESTION 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 | Being physically in this place now and mentally in another place |

| Physically visiting the place, you want to visit | QUESTION 2 1 2 3 4 5 6 | Mentally visiting the place, you want to visit |

| Physically going to the required place to perform an activity | QUESTION 3 1 2 3 4 5 6 | Performing an activity in a virtual space |

| Being physically and mentally in a single environment, being completely there and feeling it | QUESTION 4 1 2 3 4 5 6 | Being physically and mentally in a semi-virtual/semi-real environment interacting with all abstract/concrete elements |

| Living with the tangible and real | QUESTION 5 1 2 3 4 5 6 | Living with the abstract and the virtual |

| Existence of limiting factors such as time, place, work, school to travel | QUESTION 6 1 2 3 4 5 6 | Being able to travel virtually wherever and whenever you want |

| Expressing the contemporary equivalents of the concepts of distance and proximity | QUESTION 7 1 2 3 4 5 6 | Far is near and near is far |

| Maintaining all social relations face to face | QUESTION 8 1 2 3 4 5 6 | Maintaining all social relations without being in the same environment with people |

| Ensuring communication by phone and video call | QUESTION 9 1 2 3 4 5 6 | Providing communication with hologram technology |

| A doctor’s surgery on a person in the place where s/he is physically present | QUESTION 10 1 2 3 4 5 6 | Remote surgery on a person in another part of the world, different from the place where a doctor is |

| Walking somewhere | QUESTION 11 1 2 3 4 5 6 | Getting the destination to our feet |

| Physically going to school | QUESTION 12 1 2 3 4 5 6 | Being in school mentally while being in another place physically |

| Same country where you live and work | QUESTION 13 1 2 3 4 5 6 | The country you work in is different from the country you live in |

| Same city where you live and work | QUESTION 14 1 2 3 4 5 6 | The city you work in is different from the city you live in |

Source: Produced by the authors (2024).

Table A5.

Questions about the sharing and privacy dilemma in the psychometric test.

Table A5.

Questions about the sharing and privacy dilemma in the psychometric test.

| The place cannot not keep (store) your personal data | QUESTION 15 1 2 3 4 5 6 | The place can keep (store) your personal data |

| Protection and confidentiality of information about you | QUESTION 16 1 2 3 4 5 6 | Sharing information about you transparently with everyone |

| Only you have the right to access your data | QUESTION 17 1 2 3 4 5 6 | Persons and institutions that you give permission to have access to your data |

| Your spatial behaviour data is not recorded and measured | QUESTION 18 1 2 3 4 5 6 | Regular recording and analysis of your spatial behaviour data |

| Items are passive and have only functions to meet current needs | QUESTION 19 1 2 3 4 5 6 | Items are active in use of personal information to provide services |

| Using technology within private and secure limits | QUESTION 20 1 2 3 4 5 6 | Benefiting from all the benefits of technology in a transparent and sharing way |

| Effortlessly accessing knowledge about the physical environment through personal experience | QUESTION 21 1 2 3 4 5 6 | Digital and ready availability of information about the physical environment always |

Source: Produced by the authors (2024).

Table A6.

Questions about the natural body–body dependent on digital dilemma in the psychometric test.

Table A6.

Questions about the natural body–body dependent on digital dilemma in the psychometric test.

| Keeping the body in its natural state | QUESTION 22 1 2 3 4 5 6 | Attaching a technological apparatus to the body |

| The movement of the individual according to the place s/he is in | QUESTION 23 1 2 3 4 5 6 | Changing the shape of the space depending on the body movements of the individual |

| The ability of your body to move in its natural state as independent of space | QUESTION 24 1 2 3 4 5 6 | Establishing a kind of digital connection between your body and space |

| The fact that technological tools are in today’s dimensions and portable | QUESTION 25 1 2 3 4 5 6 | Integration of technological tools into the human body in micro dimensions |

| Carrying objects that provide continuous data flow out of your body | QUESTION 26 1 2 3 4 5 6 | Carrying objects that provide continuous data flow into your body |

| Always have the control of your personal mind and will in the space you are in. | QUESTION 27 1 2 3 4 5 6 | Temporarily leaving personal mind and will control to a smarter device/robot in the space you are in |

| Doing daily chores by oneself | QUESTION 28 1 2 3 4 5 6 | Basic daily work done by artificial intelligence and robots |

Source: Produced by the authors (2024).

Table A7.

Questions about the robust places/goods and vulnerable places/goods dilemma in the psychometric test.

Table A7.

Questions about the robust places/goods and vulnerable places/goods dilemma in the psychometric test.

| Having a large, spacious, built-in home | QUESTION 29 1 2 3 4 5 6 | Having a portable home that is small enough to meet your needs |

| Covering the contactable parts of the living and working environment with hard and durable surfaces | QUESTION 30 1 2 3 4 5 6 | Covering the touchable parts of the living and working environment with soft, sensitive, digital surfaces |

| Having a traditional, permanent, unchanging house type | QUESTION 31 1 2 3 4 5 6 | To have a house type that can be expanded and changed according to demand and need |

| The walls and ceiling of the place to be fixed | QUESTION 32 1 2 3 4 5 6 | The walls and ceiling of the place can be moved and relocated according to demand and need. |

| Cultivating certain vegetables and fruits on certain lands and offering them to the public through markets | QUESTION 33 1 2 3 4 5 6 | Having common agricultural areas where everything can be grown |

Source: Produced by the authors (2024).

Table A8.

Questions about the single-function space–multi functional space dilemma in the psychometric test.

Table A8.

Questions about the single-function space–multi functional space dilemma in the psychometric test.

| Having workplaces separate from home | QUESTION 34 1 2 3 4 5 6 | Working places inside the house, designing it together with the home |

| The working place is single, limited and within the rules. | QUESTION 35 1 2 3 4 5 6 | Multiple, unlimited, and flexible rules in every sense of the workplace |

| The place where you live, and work is fixed | QUESTION 36 1 2 3 4 5 6 | Moving and changing the place where you live and work |

| Preserving and maintaining the habitual established spatial order | QUESTION 37 1 2 3 4 5 6 | Using it by changing the spatial layout |

| Realization of living, working and entertainment in different physical environments/spaces | QUESTION 38 1 2 3 4 5 6 | Living, working, and having fun in the same physical environment/space |

| Holding business meetings in your own spaces | QUESTION 39 1 2 3 4 5 6 | Holding business meetings in constantly changing and rented venues |

| Cities where physical/bodily actions are dominant and intense | QUESTION 40 1 2 3 4 5 6 | Cities where mental acts are dominant and intense |

| The need for bodily movement to access physical spaces | QUESTION 41 1 2 3 4 5 6 | Accessing digital spaces with mental movement |

| Permanently owning a place | QUESTION 42 1 2 3 4 5 6 | Using the properties, you do not own by subscribing or renting |

| Having your own home | QUESTION 43 1 2 3 4 5 6 | Living in homes that do not belong to you with a subscription or term rental system |

| Having your own vehicle | QUESTION 44 1 2 3 4 5 6 | Using a car that does not belong to you with a subscription or term rental system |

| Continuation of passport and visa applications for international travels | QUESTION 45 1 2 3 4 5 6 | Removal of passport and visa applications for international travels |

| Use of currency that varies between countries | QUESTION 46 1 2 3 4 5 6 | Use of a single currency valid worldwide |

| Value judgments that change from society to society, from culture to culture | QUESTION 47 1 2 3 4 5 6 | Universal value judgments |

Source: Produced by the authors (2024).

Table A9.

Questions on the natural systems–smart systems dilemma in the psychometric test.

Table A9.

Questions on the natural systems–smart systems dilemma in the psychometric test.

| Being responsible for everything in the house | QUESTION 48 1 2 3 4 5 6 | Delegation of responsibility for everything in the house to smart devices and robots |

| Energy saving and recycling by individuals | QUESTION 49 1 2 3 4 5 6 | Energy saving and recycling by smart buildings |

| Being in control of traffic | QUESTION 50 1 2 3 4 5 6 | Control in traffic by driverless, autonomous vehicles |

| Objects are independent of each other and only related to their own functions | QUESTION 51 1 2 3 4 5 6 | Objects being connected and interacting with each other |

| A life without internet | QUESTION 52 1 2 3 4 5 6 | A life with unlimited internet |

| Deciding by yourself | QUESTION 53 1 2 3 4 5 6 | Everything is decided by artificial intelligence that knows you completely and knows what you like and don’t like. |

| Progress of social relations by meeting one-on-one | QUESTION 54 1 2 3 4 5 6 | Obtaining information about people through a general scoring system in social relations |

| Going to a certain place personally, communicating with the employees face to face and following the process personally | QUESTION 55 1 2 3 4 5 6 | Handling the processes by devices/robots with artificial intelligence |

| Having authority and decision-making power in humans | QUESTION 56 1 2 3 4 5 6 | Having the authority and decision-making authority in robots with artificial intelligence |

| Informing local government in person orally or in writing about your opinions on the city you live in | QUESTION 57 1 2 3 4 5 6 | Obtaining your opinions on the city you live in through digital data belonging to you by local government |

| Collecting and processing human-made data in the urban planning process | QUESTION 58 1 2 3 4 5 6 | Collection of digital data and processing of data by artificial intelligence in the urban planning process |

Source: Produced by the authors (2024).

References

- Andrushchenko, Victor, Irina Yershova-Babenko, Dina Kozobrodova, Anna Seliverstova, and Irina Lysakova. 2022. Digitalization of society: Implications and perspectives in the context of the psycho-dimensionality of social reality/psychosynertics. Amazonia Investiga 11: 183–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelidou, Margarita. 2014. Smart city policies: A spatial approach. Cities 41: 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ash, James, Rob Kitchin, and Agnieszka Leszczynski. 2018. Digital turn, digital geographies? Progress in Human Geography 42: 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzari, Margherita, Chiara Garau, Paolo Nesi, Michela Paolucci, and Paola Zamperlin. 2018. Smart city governance strategies to better move towards a smart urbanism. In Computational Science and Its Applications–ICCSA 2018: 18th International Conference, Melbourne, VIC, Australia, July 2–5. Proceedings, Part III 18. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 639–53. [Google Scholar]

- Barns, Sarah. 2018. Platform urbanism rejoinder: Why now? What now. Mediapolis. A Journal of Cities and Culture 3. [Google Scholar]

- Chiappini, Letizia. 2020. The urban digital platform: Instances from Milan and Amsterdam. Urban Planning 5: 277–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coletta, Claudio, Liam Heaphy, Sung Yueh Perng, and Laurie Waller. 2017. Data-driven cities? Digital urbanism and its proxies: Introduction. TECNOSCIENZA: Italian Journal of Science & Technology Studies 8: 5–18. [Google Scholar]

- Corbet, Heidi, Ian Caldwell, Ian Goodfellow, Michael Riebel, and Oliver Milton. 2019. Changing Spaces. In Future Campus. London: RIBA Publishing, pp. 29–37. [Google Scholar]

- Cripps, Barry. 2017. Psychometric Testing: Critical Perspective. West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- ÇŞİDB. 2024. Türkiye National Smart Cities Strategy and Action Plan. Republic of Türkiye Ministry of Environment, Urbanization and Climate Change. Available online: https://www.akillisehirler.gov.tr/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Taslak-Eylem_Plani.pdf (accessed on 11 September 2024).

- Cureton, Paul. 2022. Augmented Reality: Robotics, Urbanism and the Digital Turn. In The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Urban and Regional Future. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, Ayona. 2018. The digital turn in postcolonial urbanism: Smart citizenship in the making of India’s 100 smart cities. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 43: 405–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, Ayona. 2023. The digitalising state: Governing digitalization-as-urbanization in the global south. Progress in Human Geography 47: 141–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Hoop, Evelien, Timothy Moss, Adrian Smith, and Emanuel Löffler. 2021. Knowing and governing smart cities: Four cases of citizen engagement with digital urbanism. Urban Governance 1: 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vos, Jan. 2020. The Digitalization of (Inter) Subjectivity: A Psy-Critique of the Digital Death Drive. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- DeVon, Holli A., Michelle E. Block, Patricia Moyle-Wright, Diane M. Ernst, Susan J. Hayden, Deborah J. Lazzara, Suzanne M. Savoy, and Elizabeth Kostas-Polston. 2007. A psychometric toolbox for testing validity and reliability. Journal of Nursing Scholarship 39: 155–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiCerbo, Kristen E., Valerie Shute, and Yoon Jeon Kim. 2017. The future of assessment in technology rich environments: Psychometric considerations. In Learning, Design, and Technology: An International Compendium of Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DTO. 2024. Türkiye Digital State Strategy & National Artificial Intelligence Strategy. Presidency of the Republic of Türkiye Digital Tranformation Office. Available online: https://cbddo.gov.tr/en/ (accessed on 11 September 2024).

- Dufva, Tomi, and Mikko Dufva. 2019. Grasping the future of the digital society. Future 107: 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eren, Fatih. 2016. The re-specification of concepts in the morphogenetic approach for property market research. ICONARP International Journal of Architecture and Planning 4: 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eren, Fatih, and John Henneberry. 2021. The glocalisation’ of Istanbul’s retail property market. Journal of European Real Estate Research 15: 278–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]