Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has fundamentally transformed workplace dynamics worldwide. Within this context, emerging patterns in job demand and job resources necessitate a thorough examination of how these workplace changes affect work–family interference and employee well-being across diverse occupational categories. The current study investigates the differential impact of job characteristics on job satisfaction and work stress during the COVID-19 pandemic, comparing blue-collar and white-collar occupations in China. Drawing from the Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS) database, we conducted a cross-sectional analysis using data from two time periods, 2015 and 2021, encompassing 10,968 and 8148 valid samples, respectively. Through bootstrapping analysis, we tested the indirect effects of job characteristics on employee well-being, mediated by work–family interference. The results reveal distinct patterns across occupational categories. Blue-collar workers demonstrated increased susceptibility to work-related stress, primarily due to the compounding effects of dual workload demands that intensified their work–family interference. Conversely, white-collar employees maintained a positive relationship between job autonomy and job satisfaction, despite the negative mediating influence of work–family interference.

1. Introduction

On 11 March 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 a pandemic, signifying not only a public health crisis but also one that would affect every sector (World Health Organization 2020). The health crisis has evolved into a global economic and social crisis, resulting in unprecedented damage to the world of work. According to the estimates from the International Labor Organization (ILO), global hours worked during the year decreased by nearly 9 percent compared to the last quarter of 2019, and labor income was down by 8.3 percent in 2020 compared to pre-pandemic levels (International Labour Organization 2021). These factors have combined to disproportionately impact vulnerable and disadvantaged individuals. Lockdown measures and social-distancing protocols have created significant barriers for lower-income workers, those in alternative work arrangements, and individuals with lower educational attainment (Adams-Prassl et al. 2020; Blundell et al. 2022; Zhang et al. 2022). This impact has been especially pronounced in sectors such as hospitality, health care, and retail, where remote work options are limited. The evidence demonstrates a clear pattern of disproportionate impact across different workforce segments, highlighting the pandemic’s role in exacerbating existing labor market inequalities.

During the pandemic, some professional roles transitioned to remote work, while manual jobs necessitated on-site presence. Simultaneously, employees in critical professions might have encountered a significantly increased workload, coupled with additional workplace stressors and health risks (Cotofan et al. 2021). Consequently, the alterations to workplace dynamics prompted by the crisis are likely to have varied impacts on employee well-being across different job categories. For example, individuals engaged in remote work may experience distinct changes in workplace conditions compared to those working on-site during the COVID-19 crisis. Previous studies have revealed paradoxical outcomes of remote work on employee stress and engagement. Virtual work offers employees greater job autonomy, encouraging their active involvement, yet may diminish work engagement because of reduced emotional support (Etheridge et al. 2020; Sardeshmukh et al. 2012). Conversely, remote work can alleviate stress by saving time and money on commuting, but it may also lead to overwork due to the expectation of constant online availability (Weinert et al. 2014). On the other hand, workers in essential industries, where physical presence is often mandatory, face heightened safety concerns due to the inherent nature of their work (Loustaunau et al. 2021). In summary, the evolving workplace environment under the COVID-19 pandemic may either amplify or alleviate work stress and job satisfaction depending on the nature of the job. In this study, we aim to elucidate the relationship between job characteristics and employee well-being across different job types, employing a research design grounded in the job demands–resources (JD-Rs) model (Demerouti et al. 2001).

The growing prevalence of work–family conflict in contemporary society is a consequence of heightened demands in workplaces and a gradual increase of dual-career couples (Greenhaus et al. 1989). Global economic interconnectedness has led to increased competition and pressure in the workplace, exacerbated by economic fluctuations and market dynamics that can contribute to job insecurity among workers. This, in turn, may result in more demanding job roles and further contribute to more work–family conflict. Consequently, numerous studies have highlighted the challenges faced by the working population and dual-earner couples in achieving a balance between work and private life (Geurts and Demerouti 2003; Hwang and Ramadoss 2017). Moreover, advancements in technology have transformed the nature of work, transitioning from traditional physical office settings to a virtual workspace. While some studies have shown that remote working can mitigate work–family interference (Allen and Finkelstein 2014; Gajendran and Harrison 2007), others have found that telecommuting increases susceptibility to work–family interference due to the blurring boundaries between work and family responsibilities (Boswell and Olson-Buchanan 2007; Wang et al. 2021). With unexpected job demand and job resources emerging during the pandemic, it is crucial to explore whether the evolving workplace landscape triggers work–family interference, subsequently impacting the level of work stress and job satisfaction across different job types.

To address these research gaps, the current study utilizes the cross-sectional data from the Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS) to investigate the evolving relationship between job characteristics, employee well-being, and work–family interference during the COVID-19 pandemic. The context and timing of this research are distinctive in several aspects. Data for this study were collected during the middle phases of the pandemic (June 2021), coinciding with five major COVID-19 outbreaks that occurred throughout the year (Zha et al. 2022). During this period, employees experienced heightened stringency measures, including school closures, workplace closures, travel bans, cancellation of public events, restrictions on public gatherings, closures of public transport, stay-at-home requirements, public information campaigns, restrictions on internal movements, lockdowns, social-distancing orders, travel restrictions, distance education, and distance-working arrangements, among others (Hale et al. 2021). Many individuals encountered adverse events within their families, workplaces, communities, and countries, potentially resulting in unprecedently changes to existing work–life balance and overall quality of life.

This article makes four main contributions. Theoretically, it contributes by being one of the first studies to examine the antecedents of employee well-being across different job types using the JD-R model within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Secondly, by using a combined CGSS database in 2015 and 2021, this study addresses a gap in the literature by compensating for the tendency of previous research on the JD-R model to focus primarily on the pandemic period. By comparing data from before and during the pandemic, the study sheds light on changes in employee well-being in a non-Western society. Thirdly, the study adds empirical evidence by exploring the underlying mechanisms linking job characteristics and employee well-being. Specifically, it investigates whether work–family interference plays a different mediating role in the relationship between job characteristics and employee well-being across different job types, given the radical changes in work–family conditions brought about by the pandemic. Lastly, this study offers practical implications by serving as a guideline for policymakers seeking to mitigate work–family interference and enhance employee well-being across different job types, particularly in the context of a pandemic emergency.

2. Definition

Job demands are defined as the physical, psychological, social, or organizational aspects of a job that necessitate sustained physical and/or psychological effort and are thus associated with certain physiological and/or psychological costs (Demerouti et al. 2001). Conversely, job resources encompass the physical, psychological, social, or organizational aspects of a job that facilitate the achievement of work goals; reduce job demands and the associated physiological and psychological costs; or foster personal growth, learning, and development (Bakker and Demerouti 2007). Work–family interference is characterized as “a form of inter-role conflict in which the role pressures from the work and family domains are mutually incompatible in some respect” (Greenhaus and Beutell 1985, p. 77). This definition implies that work can impact family life and vice versa. Work–family interference arises when work-related demands encroach upon home responsibilities, whereas family–work interference occurs when family obligations impede work activities (Frone et al. 1992). Scholars have acknowledged the bidirectional nature of conflict between these two spheres and have distinguished between work interference with family (WIF) with family interference with work (FIW) (Greenhaus and Powell 2003). Research consistently indicates that WIF tends to be more prevalent than FIW due to the greater permeability of the family role compared to the work role (Bellavia and Frone 2005). Given that the antecedent factors of WIF and FIW are domain-specific, the current study focuses solely on the mediating effect of WIF on the relationship between job characteristics and employee well-being.

Workers are often categorized using various classifications, with two of the most common being blue-collar and white-collar workers (Investopedia 2023a). Consequently, this study divides classifications into two types, low-skilled blue-collar, and professional and white-collar workers. Low-skilled blue-collar workers are traditionally characterized by wearing blue shirts; possessing lower levels of education; and working in settings such as plants, mills, and factories. They are typically compensated hourly or through piecework and are primarily employed in industries such as manufacturing, construction, transportation, and certain services (Investopedia 2023b). On the other hand, Professional and white collars are known for earning higher average salaries and engaging in highly skilled work that requires advanced education and training, typically in professional, managerial, and administrative roles (Investopedia 2022). Following the skill-level classification of the International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO-08), low-skilled blue-collars typically require skill Level 1 and Level 2, involving the performance of simple physical or manual tasks and a high level of manual dexterity, such as operating machinery and driving vehicles. Professional and white collars, on the other hand, require skill Level 3 and Level 4, involving the performance of complex technical and problem-solving based on theoretical knowledge in a specialized field (International Labour Organization 2012, pp. 12–14). Therefore, in this study, low-skilled blue-collar workers refer to Major Group 5–9, while professional and white-collar workers refer to Major Group 1–4 in ISCO-08 (International Labour Organization 2012, pp. 87–337).

3. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

3.1. Job Demand–Resource Model and Employee Well-Being During the COVID-19

The primary aim of this study is to investigate the relationship between job demand, job resources, and employee well-being, employing the JD-R model as the conceptual framework. This occupational stress model demonstrates that strain emerges when individuals experience an imbalance between workplace demands and their available resources to address these demands (Bakker and Demerouti 2007). This model has been widely adopted by Occupational Health and Workplace Safety agencies globally to guide psychosocial activities and risk assessment approaches (Bakker and Demerouti 2017). It operates on the premise that while every occupation may possess its unique working characteristics, these can generally be categorized into two overarching domains, job demands and job resources, forming a model applicable across various occupational settings (Demerouti et al. 2001). To date, the JD-R model has demonstrated its utility not only invariant across different occupational groups (Bakker et al. 2003; Korunka et al. 2009) but also across diverse countries (Hakanen et al. 2006; Llorens et al. 2006). Additionally, the model posits that job demands and resources give rise to two distinct processes: a health-impairment process and a motivational process (Demerouti et al. 2001). Previous studies have highlighted that job resources such as workplace social support and job control are strongly associated with job satisfaction, whereas job demands such as quantitative workload, work contents, and the physical work environment primarily influence emotional exhaustion (Janssen et al. 2004; Hakanen et al. 2008).

Economic downturns during the pandemic crisis have the potential to significantly impact the global labor market and the well-being of workers worldwide (Cotofan et al. 2021). Lower-income and lower-skilled workers are particularly vulnerable, as they are more likely to be employed in jobs and sectors that have been adversely affected by the pandemic. Industries such as accommodation and food service, transportation, and recreation, which were directly impacted by lockdowns and supply chain disruptions, struggled to maintain regular operations during the early phases of the pandemic, resulting in job insecurity for workers (Eurostat 2022). Consequently, low-income and low-skill workers experienced reduced working hours and greater earning losses compared to high-income and professional workers (Benzeval et al. 2020; Kikuchi et al. 2021). As job security diminishes and income inequality widens, workers in low-wage positions report significantly lower job satisfaction than their counterparts in professional roles (Johnson and Whillans 2022). Moreover, in sectors like healthcare, construction, and accommodation, factors such as lack of workplace safety, heavy workloads, home situations, and concerns about job stability further contribute to work-related stress (Leo et al. 2021; Pamidimukkala and Kermanshachi 2021; Vo-Thanh et al. 2022). Specifically, the well-being of low-skilled blue-collar workers may be disproportionately affected during the pandemic compared to professional and white-collar workers. Based on these observations, we propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1.

There is a difference in the level of work stress and job satisfaction between years (before and during the COVID-19 pandemic) and job types.

Hypothesis 2.

There is an interaction effect between years (before and during the COVID-19 pandemic) and job types on the level of work stress and job satisfaction.

Research examining workplace changes during COVID-19 has revealed significant insights into job satisfaction and work-related stress. Studies indicate that several key factors enhance job satisfaction among remote workers: flexible work schedules, supportive management, having a suitable workspace, receiving digital social support, benefiting from appropriate monitoring mechanisms, and having job autonomy (Blundell et al. 2020; Yu and Wu 2021). Conversely, research shows that pandemic-related work intensification has emerged as the primary contributor to work stress, leading to elevated burnout symptoms (Küppers et al. 2024; Corrente et al. 2024). The JD-R model has provided a valuable framework for analyzing remote work outcomes during the pandemic, though its application remains limited. Research applying this model has demonstrated that job autonomy positively correlates with job satisfaction (Wood et al. 2022), whereas increased workload contributes to heightened emotional exhaustion (Wang et al. 2021).

These findings collectively underscore the significant influence of job autonomy and workload on remote employees’ well-being during the pandemic. However, there is limited research focusing on the well-being of workers employed in lower-wage and lower-skilled jobs that require physical presence in the workplace (Johnson and Whillans 2022). Therefore, this study aims to build upon existing research by employing the JD-R model to examine whether the relationships between job demand, job resources, and employee well-being apply to both professional and white-collar workers and low-skilled blue-collar workers during the COVID-19 crisis. As such, we propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 3.

Job demands demonstrate a direct positive relationship with employee work stress, and this relationship remains consistent across different occupational categories.

Hypothesis 4.

Job resources demonstrate a direct positive relationship with employee job satisfaction, and this relationship remains consistent across different occupational categories.

3.2. The Mediation Role of Work–Family Interference During Pandemic

The second aim of this study is to investigate the role of WIF as a specific mediator in the relationships between job characteristics and employee well-being across different job types. According to the effort–recovery perspective, work–family conflict may arise when a worker’s functioning and recovery in the family domain are impeded by job demands accumulated in the work domain (Meijman and Mulder 1998). A high level of work–family interference suggests that recovery in the home situation may be compromised, subsequently affecting personal well-being (Geurts and Sonnentag 2006). Empirical evidence supporting the role of WIF as a mediator between job demands, job resources, and well-being has been documented in various studies, particularly those conducted in occupation-specific contexts (Geurts et al. 2003; Gözükara and Çolakoğlu 2016; Janssen et al. 2004; Mostert et al. 2011; Verhoef et al. 2021). For instance, Mostert et al. (2011) investigated low-wage non-professional workers in South Africa and found that job demands were partially related to burnout, both directly and indirectly through negative WIF. In a study involving 270 participants, Gözükara and Çolakoğlu (2016) demonstrated that job autonomy had a positive effect on job satisfaction, whereas WIF had a negative mediating effect on this relationship. These findings underscore the importance of considering WIF as a mediator in understanding the impact of job characteristics on employee well-being across different social contexts.

The COVID-19 pandemic has precipitated significant shifts in the labor market, potentially influencing work–family interference and employee well-being among different job types in distinct ways. Previous research has highlighted the challenges faced by employees during the COVID-19 pandemic, including fears of transmitting the infection to their families, difficulty in managing childcare responsibilities, increased levels of anxiety and depression, and disruption to social and family life being affected (Şişman et al. 2023). Professional and white collars, who transitioned to remote work during the pandemic, experienced newfound flexibility in managing their schedules to accommodate family responsibilities (Martucci 2023). Yet this shift presented complex implications for work–family dynamics. Research indicates that remote work arrangements created a complex dynamic in work–family relationships. While working from home facilitated greater engagement in family-related tasks, WIF emerged as a significant challenge, primarily due to increasingly blurred boundaries between professional and personal domains (Hu et al. 2023; Kerman et al. 2022). This finding is further supported by a Chinese case study, which revealed that WIF served as a mediating factor between workload and emotional exhaustion (Wang et al. 2021). Given these nuanced findings regarding remote work’s impact on WIF and employee well-being, additional research is warranted to better understand WIF’s mediating role during the pandemic.

Low-skilled blue-collar workers, whose jobs often require physical presence, were unable to benefit from the flexibility of remote work. Instead, they faced additional risks associated with commuting and physical interaction in the workplace (Tayal and Mehta 2023). This limitation may have made it challenging for them to address family needs while fulfilling work obligations. The pandemic also disrupted traditional working schedules in field-based settings, further compromising work–family equilibrium for blue-collar employees (Jeleff et al. 2022). In conclusion, both theoretical frameworks and empirical studies support WIF’s mediating role in the relationship between job demands, job resources, and employee well-being across various occupational contexts. Nevertheless, a significant research gap exists regarding WIF’s mediating function specifically for lower-wage and lower-skilled workers during the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly in how job characteristics influenced employee well-being through WIF in these populations. Therefore, we propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 5.

Job demands exhibit an indirect relationship with work stress through WIF, and this mediating effect varies across occupational categories.

Hypothesis 6.

Job resources exhibit an indirect relationship with job satisfaction through WIF, and mediating effect varies across occupational categories.

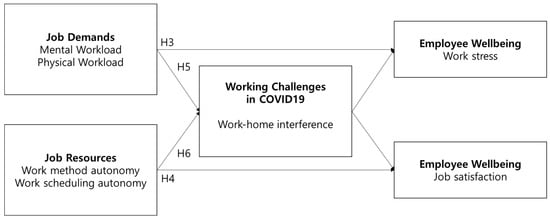

The research model guiding the present research is presented in Figure 1. The model illustrates relationships through direct arrows connecting job characteristics (e.g., job demand and job resources) to employee well-being outcomes (e.g., work stress and job satisfaction), as well as indirect pathways from job characteristics to employee well-being through work–family interference. Specifically, we expected that WIF plays a partially mediating role in the relationship between two indicators of job demand (e.g., physical workload and mental workload) and work stress, as well as between two indicators of job resources (e.g., work-method authority and work-scheduling authority) and job satisfaction across different occupational categories.

Figure 1.

Research model.

4. Method

4.1. Data Source and Sample Characteristics

The research data are cross-sectional data from the Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS). The CGSS, launched in 2003, is the earliest national representative continuous survey project, and it aims to systematically monitor the changing relationship between social structure and quality of life in both urban and rural China. Social structure involves demographic and socioeconomic variables, such as age, education, class, income, etc. Quality of life involves five dimensions related to the well-being of a family or an individual, including health, demographic, psychological, socioeconomic, and political/community. The project adopts a multi-stage stratified random sampling procedure to conduct a household face-to-face survey, with counties serving as primary sampling units, urban communities, and rural villages as secondary sampling units, and households randomly selected using a mapping sampling method (Bian and Li 2012). The urban–rural ratio of all target samples is 6:4, basically consistent with the actual situation in China. To facilitate horizontal–longitudinal cross-cultural comparative research, part of its survey content is consistent with that of the International Social Survey Program (ISSP) and the East Asian Social Survey (EASS).

In order to catch the change of working circumstance before and during the COVID19 pandemic, we examined the CGSS data 2015 and 2021 together. The 2015 data were publicly released on 1 January 2018, including 10,968 valid samples, covering 478 communities from 28 provinces (including major metropolitan cities and autonomous regions), consisting of A to F modules. In particular, both C (EASS) and D (ISSP) modules contain specific information about working conditions and employee well-being, such as job type, job demand, and job satisfaction. The 2021 data were publicly released on 1 March 2023, comprising 8148 valid samples, including the A core module, and B and C theme modules, covering the comprehensive impact on working conditions and health behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic. The survey project spanned 5 months, and participants from 21 provinces (including major metropolitan cities and autonomous regions) were recruited. These variables are directly relevant to the research objectives of this study. For more detailed information, please refer to the provided source: http://cgss.ruc.edu.cn/ (accessed on 19 February 2024).

4.2. Measurements

This study focused on two main employee well-being outcomes, job satisfaction and work stress developed by Demerouti et al. (2001). Job satisfaction was measured using “In general, are you satisfied with your present job?” on a five-point Likert scale, from 1 “very satisfied” to 5 “very dissatisfied”. Work stress was measured using “How frequently do you experience stress in your work?” on a four-point Likert scale, from 1 “always” to 4 “seldom”. Both of the two responses were reverse-coded to ease the interpretation. A higher score resembles a higher level of job satisfaction and work stress.

Job demands consist of two variables adapted from Demerouti et al. (2001): physical workload and mental workload. The workload was measured by a two-item scale based on asking respondents, “Does the physical workload happen frequently in your work?” and “Does the mental workload happen frequently in your work?” using a four-point Likert scale, from 1 “always” to 4 “seldom”. Both of the two responses were reverse-coded to ease the interpretation. A higher score represents a higher workload level.

Job resources were assessed using a modified version of job autonomy developed by Morgeson and Humphrey (2006). The work-method autonomy and work-scheduling autonomy scale consist of three questions for participants: “The extent to which you can determine the specific way in which you work?” ranging from 1 to 4 (1 = completely autonomous decision, 4 = completely unable to decide); “When will your boss inform you about your schedule?” ranging from 1 to 5 (1 = anytime in a day, 5 = two weeks or more in advance); and “How is your usual work schedule organized?” ranging from 1 to 5 (1 = regular day shift, 2 = regular night shift, 3 = alternating holiday system, 4 = frequently changing work schedules, and 5 = other work schedules). We reverse-coded scores in the first and the third items to associate higher scores with higher values of resources. Responses consisting of “don’t know” and “refuse to answer” were treated as missing data.

Work–family interference was measured using questions from Wood et al. (2022), which were adapted from Voydanoff (1988), “In general, how often did you feel work interfered with your family affairs?” This item reflects the recent experiences of WIF during the pandemic. The response options range from 1 to 5 (1 = always, 5 = never). We reverse-coded the score, and a higher score represents a higher conflict level.

Control variables: Previous studies suggested that individual characteristics and socioeconomic status significantly affect the employees’ well-being (Tsen et al. 2023). To obtain the effect of job demand, job resources, and work–family interference on employee well-being, some control variables were used in this study, including age, gender, marital status, health status, education, family socioeconomic status, and residential regions. In addition, from a life-cycle perspective, we also added parents of children under 18 years old as a control variable (Le Vigouroux et al. 2022; Zuzanek 1998). Age was a continuous variable, ranging from 19 years old to 65 years old. Gender, marital status, and residential regions were coded as dummy variables (“female” = 0 and “male” = 1 for gender; “others” (divorced, widowed, or separated) = 0 and “married/single” = 1 for marital status; and “west region” = 0 and “north/east/middle region” = 1 for residential regions). Considering the characteristics of the survey areas in the CGSS 2021, the 19 areas were divided into four regions: “North” (Beijing, Hebei, Shanxi, Neimenggu, Liaoning), “East” (Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Shandong, Fujian), “Middle” (Anhui, Jiangxi, Henan, Hubei, Hunan), and “West” (Guangxi, Chongqing, Shaanxi, Gansu, Ningxia). Level of education, family socioeconomic status, and health status was measured using an ordinal scale (“no education and graduated from primary school” = 1 to “master’s degree or higher” = 13 for education; “far below the average level” = 1 to “far above the average level” = 5 for family socioeconomic status; “very unhealthy” = 1 to “very healthy” = 5 for health status). The occupation classification in CGSS 2021 adopted the criteria of ISCO-08. Thus, in this current study, the occupations belonging to professional and white collars included “Major Group 1–4”, such as Managers, Professionals, Technicians and Associate Professionals, and Clerical Support Workers. Low-skilled blue collars included “Major Group 5–9”, such as Services and Sales Workers, Skilled Agricultural, Forestry and Fishery Workers, Craft and Related Trades Workers, Plant and Machine Operators and Assemblers, and Elementary Occupations. According to 2021 data from the Chinese Bureau of Statistics, the annual salaries of middle-level and above managers are three times higher than those of manufacturing and social production services. Annual salaries of professional and technical staff are two times higher than those of manufacturing and social production services (National Bureau of Statistics 2022). Thus, low-skilled blue collars have relatively lower salaries than professional and white collars in the Chinese Context.

4.3. Analysis Techniques

We conducted our analyses using two waves of cross-sectional data from the CGSS. Firstly, we focused on the years 2015 and 2021 to investigate differences in employee well-being before and during the pandemic. Specifically, we examined employee well-being between job types, collapsed across years. Subsequently, we explored whether differences between jobs changed due to the pandemic by looking at the interaction between year with job type. Secondly, to assess the significance and strength of the relationships between job demands, job resources, work–family interference, and well-being, we employed a two-tailed Pearson’s correlation test utilizing the data from 2021. Additionally, we utilized the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) to examine multicollinearity among the variables. Thirdly, we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to evaluate the model fit. We compared a null model, assuming no correlation between predictor variables and latent variables, with a proposed model categorizing variables into “job demands”, “job resources”, and “work–family interference”. The null model assumes that the models’ predictor variables and latent variables are uncorrelated. Fourthly, to explore the effect of job characteristics on overall employee well-being across job types, we split each job type and conducted a series of multiple regressions to compare the relative magnitude of each job component on overall well-being. Finally, to further examine the indirect effects of job characteristics and employee well-being via work–family interference, we used the bootstrapping method through Hayes’s PROCESS program (Hayes 2018). All analyses were performed with SPSS.

5. Results

5.1. Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 provides an overview of worker demographics categorized by job types. Consistent with our classification of workers in low-skilled blue collars and professional and white collar categories, individuals in blue-collar jobs tended to be older than those in professional occupations (M = 43 vs. M = 38), were more likely to have a lower level of academic attainment (M = 5 (vocational high school) vs. M = 9 (college)), more likely to have lower socioeconomic status (M = 2.62 vs. M = 2.87), and were more likely reside in relatively underdeveloped region (36.6% vs. 22.8%) within the Chinese context. However, it is important to note that we controlled for these demographic variables across our models, indicating that these characteristics cannot account for the results observed. Table 2 presents correlations between the major variables examined in this study. All job demands, job resources, and work–family interference variables show significant correlations with employee well-being, with the exception of work-method autonomy and work-scheduling autonomy1. Given that these two variables exhibit lower correlation values with other variables, this study only utilizes work-scheduling autonomy2 for subsequent mediation analyses.

Table 1.

Employee demographics by job types (restricted to ages 19–65).

Table 2.

Correlation of variables.

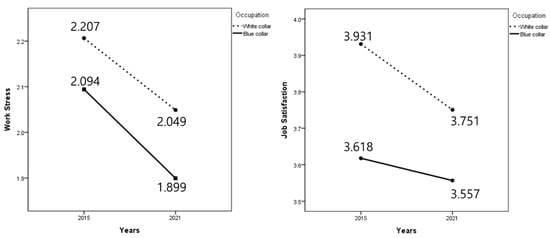

5.2. Two-Way ANOVA Tests

A series of two-way ANOVA tests were conducted to evaluate the effects of years (before and after COVID-19 pandemic) and job types (low-skilled blue collars; professional and white collars) on work stress and job satisfaction. Regarding work stress, the results revealed a significant main effect for years (F(1) = 14.34, p < 0.001) and job types (F(1) = 7.91, p < 0.01), but no significant interaction between years and job types (F = 0.158, p > 0.05). The means plot depicting employee work stress across years and job types displayed two declined lines between white-collar and blue-collar across different survey years, indicating that the level of work stress decreased in 2021 compared to that of 2015 (see Figure 2). Concerning job satisfaction, the results showed a significant main effect for years (F(1) = 8.29, p < 0.01) and job types (F(1) = 36.57, p < 0.001), with no significant interaction between years and job types (F = 2.03, p > 0.05). Similar to work stress, the means plot illustrating employee job satisfaction across years and job types exhibited two declining lines between white-collar and blue-collar workers across different survey years, suggesting that the level of job satisfaction was lower in 2021 compared to 2015 (see Figure 2). Thus, the differences observed in work stress and job satisfaction between the two survey years were consistent across both job types. Consequently, Hypothesis 1 was supported, while Hypothesis 2 was rejected.

Figure 2.

Means plot of employees’ well-being by year and occupation.

5.3. Multiple Regression Analyses

To test Hypotheses 3 and 4, regression analyses were conducted to assess the relationships between job characteristics and employee well-being across different job types. The F statistics indicated that all regression models were statistically significant. Moreover, the Durbin–Watson statistics fell between 1.876 and 2.054, suggesting no autocorrelation in the sample. As depicted in Table 3, nearly all the workloads (mental and physical) were correlated with work stress across different job types. Specifically, a significantly positive connection was found between mental workload and work stress for both white-collar (β = 0.325, p < 0.001) and blue-collar workers (β = 0.273, p < 0.001). Physical workload exhibited a positive relationship with work stress only among blue-collar workers (β = 0.262, p < 0.001). Similarly, a significantly positive relationship was observed between autonomy and job satisfaction. Work-scheduling autonomy showed differential correlations across worker types. For white-collar workers, both measures of work-scheduling autonomy were positively correlated with job satisfaction (β = 0.064, p < 0.05; β = 0.109, p < 0.001). In contrast, for blue-collar workers, only one measure of work-scheduling autonomy demonstrated a positive correlation with job satisfaction (β = 0.06, p < 0.01). Work-method autonomy showed no significant correlation with job satisfaction for either worker type. Hence, Hypotheses 3 and 4 received partial support.

Table 3.

Multiple regression estimates of employee well-being’s Standardized Beta.

5.4. Mediation Analyses

To further investigate the indirect effects of job characteristics on employees’ well-being through work–family interference, mediation analysis was conducted to assess the mediating role of WIF in the relationship between workload and work stress, and the relationship between job autonomy and job satisfaction. As presented in Table 4 (only the significant results are demonstrated), the results unveiled a series of significant indirect effects of WIF between job characteristics and employee well-being. First, mental workload had a positive effect on work stress via WIF for both white collars (0.014 [0.004, 0.027]) and blue collars (0.025 [0.005, 0.047]). Physical workload had a positive effect on work stress via WIF only for blue collars (0.029 [0.015, 0.045]). These findings indicate that elevated job demands significantly impact work stress, particularly when employees lack adequate recovery time outside of work hours. During the pandemic environment, blue-collar workers faced increasing mental and physical demands, making them especially susceptible to work–family role conflicts. The insufficient recovery from competing pressures in both work and family domains appears to result in higher psychological strain for blue-collar workers compared to their white-collar counterparts. Second, job autonomy had a positive effect on job satisfaction via WIF only for white collars (0.015 [0.004, 0.03]). The findings demonstrate a complex relationship in the pandemic remote work environment. When organizations increased employee autonomy, it led to reduced work-to-family interference, establishing a negative relationship between these variables. Interestingly, this reduction in work-to-family interference subsequently resulted in decreased job satisfaction, creating another negative relationship. However, the overall indirect effect reveals that enhanced employee autonomy ultimately improved job performance through the work-to-family interference pathway. This mediation pattern, while counterintuitive, highlights the sophisticated nature of vocational behavior, where variables can generate competing effects through different pathways. Hence, Hypotheses 5 and 6 received partial support.

Table 4.

Mediation analyses summary.

6. Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic has introduced a distinctive scenario, compelling employees to either work remotely or remain at physical locations amid the risk of infection. This situation prompts a reevaluation of the relevance of existing knowledge regarding workplace environments across diverse job types. Therefore, there is a critical need to explore the major challenges encountered by both remote and onsite workers within this evolving context, as well as the resultant impacts on their well-being. Herein, we examine the key implications of our findings.

Firstly, this study is the inaugural exploration into whether the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted the experiences of workers in low-skilled blue-collar roles and professional and white-collar roles. Leveraging two years of national data from CGSS, we aimed to discern whether changes in the workplace environment during the pandemic exerted a greater effect on the level of work stress and job satisfaction compared to the pre-pandemic period, across different job types. Our findings reveal that both low-skilled blue-collar workers and professional and white-collar workers experienced reduced work stress and job satisfaction during the pandemic years. Throughout both periods, employees in low-skilled blue-collar positions consistently reported lower job satisfaction compared to their counterparts in professional roles. Consequently, our results suggest that the pandemic has perpetuated and exacerbated pre-existing disparities between job types, in line with emerging research indicating increased dissatisfaction among workers in low-wage jobs (Johnson and Whillans 2022). Conversely, professionals consistently exhibited higher levels of work stress compared to blue-collar workers. Prior studies have noted that during the COVID-19 pandemic, lockdown measures and work-from-home policies have negatively impacted the physical activity and sedentary behavior levels of professionals (Ráthonyi et al. 2021). Particularly, individuals with higher socioeconomic status tended to become more sedentary due to work-from-home/standby-at-home arrangements, subsequently experiencing heightened anxiety related to the pandemic (Nagata et al. 2021).

Secondly, based on the statistical findings, we identified two job characteristics that are correlated with employees’ well-being in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Overall, our results align with the established literature on the JD-R model (Bakker and Demerouti 2017; Demerouti et al. 2001). The outcomes of our study bolster the notion that job characteristics are context-specific and impact workers’ stress levels and job satisfaction differently. Specifically, we observed that mental workload was positively correlated with work stress among white-collar workers, whereas both physical workload and mental workload were positively correlated with work stress among blue-collar workers. The COVID-19 pandemic posed a unique set of challenges for blue-collar workers, such as heightened occupational infection risks and financial losses, which may not have been as prevalent in white-collar industries. Prior research suggests that for blue-collar workers, being unable to work from home can lead to financial strain, while continuing to work outside the home may increase concern about infecting loved ones (Vyas 2022). Consequently, blue-collar workers may experience both physical and mental workloads in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, we only found that scheduling autonomy had a positive effect on job satisfaction for both job categories. Previous research indicates that autonomy reflects the degree to which a job allows individuals to schedule work, make decisions, and choose task methods (Wall and Jackson 1995). As the pandemic altered the workplace environment, both white-collar and blue-collar workers had to adjust their working schedules to adapt to the new circumstances. Therefore, individuals with greater scheduling autonomy may have more opportunities to enhance job engagement and improve job satisfaction amidst these changes.

Third, in line with previous studies, we confirmed that WIF challenges are correlated with employees’ well-being in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically, workload acted as a demand, increasing work–family interference and thereby aggravating employees’ level of work stress. Conversely, job autonomy, serving as job resources, helped employees cope with work–family interference challenges, thereby enhancing job satisfaction (Geurts et al. 2003; Janssen et al. 2004). Significantly, we also uncovered findings that appear to be unique in the pandemic context. First, blue-collar workers appear to experience heightened work–family interference due to both mental and physical workload demands, consequently leading to elevated work stress compared to white-collar employees. This increased strain suggests a compounding effect where the dual nature of their work responsibilities creates more significant challenges in maintaining work–life balance. Second, research conducted during the pandemic period showed that remote workers were grappling with work–family interference as a significant challenge, which could not be effectively mitigated by job autonomy alone (Wang et al. 2021). In the pandemic context, professionals working from home may experience frequent role transitions, intensifying the challenge of WIF. However, our study demonstrated that job autonomy can alleviate work–family conflicts for remote workers, subsequently improving employee job satisfaction.

The study holds some theoretical and practical implications. Theoretically, this paper contributes by validating the JD-R model in the changing workplace landscape. Our findings reveal distinct patterns of connection between job characteristics and employee well-being across different job types, thereby addressing a research gap wherein the existing literature predominantly focuses on employees working from home, overlooking those working onsite during the pandemic. Furthermore, this study delves into uncovering potential mechanisms linking job characteristics and employee well-being. We present evidence indicating that job demands may heighten work stress, while job resources may alleviate job satisfaction through the mediation effect of work–family interference across diverse job types.

In terms of practical implication, this study yielded two significant findings with important implications for organizational practice. First, our analysis confirmed that work–family interference demonstrated a stronger association with the negative outcome of emotional exhaustion compared to the positive outcome of job satisfaction across both job categories. This finding underscores the critical need for organizations to carefully evaluate their workplace policies, particularly in remote work environments. A comprehensive understanding of these complex relationships can guide the development of management strategies that effectively balance employee autonomy, work–family dynamics, and performance outcomes. Second, our research suggests targeted interventions for low-skilled blue-collar workers. Improving structural aspects of work, such as ensuring safe working conditions and addressing job insecurity, could significantly reduce work–family interference. Regarding mental workload management, organizations should implement comprehensive support systems. These should include creating a supportive work environment, providing skill development opportunities, and ensuring access to mental health assistance programs. Furthermore, organizations would benefit from implementing family-friendly policies that address both immediate and long-term needs. These policies should encompass paid parental leave, childcare assistance programs, and eldercare support. Such comprehensive support systems provide employees with essential resources to manage their family responsibilities more effectively, thereby reducing work–family interference and potentially improving both individual and organizational outcomes.

7. Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic has necessitated a reexamination of the job demands–resources model across different occupational categories, particularly regarding its application in changing workplace circumstances. This research explores the mediating role of work–family interference in the relationship between job characteristics and employee well-being, contributing significantly to the occupational health psychology literature by illuminating these dynamics during a global health crisis in China.

Our study advances existing research by quantifying distinct well-being trajectories across occupational categories. The findings reveal that blue-collar workers experienced more pronounced declines in well-being compared to their white-collar counterparts. Specifically, blue-collar workers faced heightened vulnerability to work-related stress due to dual workload pressures intensifying their work–family interference. In contrast, while work–family interference demonstrated a negative mediating effect, white-collar employees maintained a positive association between job autonomy and job satisfaction.

These findings have informed the implementation of comprehensive family-friendly workplace policies, including paid parental leave and subsidized childcare assistance programs, aimed at mitigating work–family interference and enhancing employees’ capacity to manage familial responsibilities. Notably, since work–family interference represents a negative stressful experience, it appeared to have a limited impact on the positive relationship between job resources and performance outcomes.

This study has several limitations. First, since it was not initially designed as a quasi-experimental study and primarily utilizes cross-sectional pooled data analysis, the findings should be interpreted with caution. Future research would benefit from utilizing panel data and incorporating interaction terms between year dummy variables and job types to better examine changes in working dynamics attributable to COVID-19. Additionally, our results indicate that the positive relationship between job resources and job satisfaction outcomes remained largely unaffected by work–family interference. This suggests an opportunity for future research to explore positive work–home factors, such as work–family facilitation, to uncover potential partial mediating effects in the relationship between job characteristics and employee well-being. Such an expanded scope would provide a more comprehensive understanding of workplace dynamics in evolving organizational contexts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.C. and C.L.T.; methodology, N.C.; software, C.L.T.; validation, N.C. and C.L.T.; formal analysis, N.C.; investigation, N.C.; resources, N.C.; data curation, N.C.; writing—original draft preparation, N.C.; writing—review and editing, N.C. and C.L.T.; visualization, N.C.; supervision, C.L.T.; project administration, C.L.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study as this research has followed ethical guidelines and principles established for social non-interventional studies by the Declaration of Helsinki. The data used in this paper comes entirely from the Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS) project led by the Chinese Survey and Data Center at Renmin University of China. The project number for the Chinese General Social Survey 2021 is 65635422. Data collection was carried out without data that would allow the subjects to be identified and the participants were informed of the anonymous collection and processing of their data.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the first author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Adams-Prassl, Abi, Teodora Boneva, Marta Golin, and Christopher Rauh. 2020. Inequality in the impact of the coronavirus shock: Evidence from real time surveys. Journal of Public Economics 189: 104–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, Tammy D., and Lisa M. Finkelstein. 2014. Work–family conflict among members of full-time dual-earner couples: An examination of family life stage, gender, and age. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 19: 376–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, Arnold B., and Evangelia Demerouti. 2007. The Job Demands-Resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology 22: 309–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, Arnold B., and Evangelia Demerouti. 2017. Job demands-resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 22: 273–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, Arnold B., Evangelia Demerouti, Toon W. Taris, Wilmar B. Schaufeli, and Paul J. G. Schreurs. 2003. A multigroup analysis of the Job Demands-Resources Model in four home care organizations. International Journal of Stress Management 10: 16–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellavia, Gina M., and Michael K. Frone. 2005. Work-family conflict. In Handbook of Work Stress. Edited by Julian Barling, E. Kevin Kelloway and Michael R. Frone. Thousand Oaks: Sage, pp. 113–47. [Google Scholar]

- Benzeval, Michaela, Jonathan Burton, Thomas F. Crossley, Paul Fisher, Annette Jäckle, Hamish Low, and Brendan Read. 2020. The Idiosyncratic Impact of an Aggregate Shock: The Distributional Consequences of COVID-19. London: Institute for Fiscal Studies. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, Yanjie, and Lulu Li. 2012. The Chinese General Social Survey (2003–2008). Chinese Sociological Review 45: 70–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blundell, Richard, Monica Costa Dias, Jonathan Cribb, Robert Joyce, Tom Waters, Thomas Wernham, and Xiaowei Xu. 2022. Inequality and the COVID-19 Crisis in the United Kingdom. Annual Review of Economics 14: 607–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blundell, Richard, Monica Costa Dias, Robert Joyce, and Xiaowei Xu. 2020. COVID-19 and Inequalities. Fiscal Studies 41: 291–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boswell, Wendy R., and Julie B. Olson-Buchanan. 2007. The use of communication technologies after hours: The role of work attitudes and work-life conflict. Journal of Management 33: 592–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrente, Melissa, Jungwee Park, Henrietta Akuamoah-Boateng, Jelena Atanackovic, and Ivy Lynn Bourgeault. 2024. Work & life stress experienced by professional workers during the pandemic: A gender-based analysis. BMC Public Health 24: 1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotofan, Maria, Jan-Emmanuel De Neve, Marta Golin, Micah Kaats, and George Ward. 2021. Work and well-being during COVID-19: Impact, inequalities, resilience, and the future of work. In World Happiness Report 2021. Edited by John F. Helliwell, Richard Layard, Jeffrey D. Sachs and Jan-Emmanuel De Neve. Sustainable Development Solutions Network. London: King’s College London, pp. 153–90. Available online: https://worldhappiness.report/ed/2021/ (accessed on 19 February 2024).

- Demerouti, Evangelia, Arnold B. Bakker, Friedhelm Nachreiner, and Wilmar B. Schaufeli. 2001. The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology 86: 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etheridge, Ben, Yikai Wang, and Li Tang. 2020. Worker Productivity During Lockdown and Working from Home: Evidence from Self-Reports. ISER Working Paper Series 2020–2012; Osaka: Institute for Social and Economic Research. Available online: https://www.iser.essex.ac.uk/research/publications/working-papers/iser/2020-12 (accessed on 19 February 2024).

- Eurostat. 2022. Monitoring Report on the Employment and Social Situation in the EU Following the Outbreak of the COVID-19 Pandemic. EU: The Employment Committee & The Social Protection Committee. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/social/BlobServlet?docId=24075&langId=en (accessed on 19 February 2024).

- Frone, Michael R., Marcia Russell, and M. Lynne Cooper. 1992. Antecedents and outcomes of work-family conflict: Testing a model of the work-family interface. Journal of Applied Psychology 77: 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajendran, Ravi S., and David A. Harrison. 2007. The good, the bad, and the unknown about telecommuting: Meta-analysis of psychological mediators and individual consequences. Journal of Applied Psychology 92: 1524–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geurts, Sabine A. E., and Evangelia Demerouti. 2003. Work/Nonwork Interface: A Review of Theories and Findings. In Handbook of Work and Health Psychology. Edited by Cary Lynn Cooper, Marc J. Schabracq and Jaques A. M. Winnubst. Hoboken: Wiley, pp. 279–312. [Google Scholar]

- Geurts, Sabine A. E., and Sabine Sonnentag. 2006. Recovery as an explanatory mechanism in the relation between acute stress reactions and chronic health impairment. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health 32: 482–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geurts, Sabine A. E., Michiel A. J. Kompier, Susan Roxburgh, and Irene L. D. Houtman. 2003. Does Work–Home Interference mediate the relationship between workload and well-being? Journal of Vocational Behavior 63: 532–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gözükara, İzlem, and Nurdan Çolakoğlu. 2016. The Mediating Effect of Work Family Conflict on the Relationship between Job Autonomy and Job Satisfaction. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences 229: 253–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhaus, Jeffrey H., and Gary N. Powell. 2003. When work and family collide: Deciding between competing demands. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 90: 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhaus, Jeffrey H., and Nicholas J. Beutell. 1985. Sources and conflict between work and family roles. Academy of Management Review 10: 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhaus, Jeffrey H., Saroj Parasuraman, Cherlyn Skromme Granrose, Samuel Rabinowitz, and Nicholas J. Beutell. 1989. Sources of work-family conflict among two-career couples. Journal of Vocational Behavior 34: 133–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakanen, Jari J., Arnold B. Bakker, and Wilmar B. Schaufeli. 2006. Burnout and engagement among teachers. Journal of School Psychology 43: 495–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakanen, Jari J., Wilmar B. Schaufeli, and Kirsi Ahola. 2008. The Job Demands-Resources model: A three-year cross-lagged study of burnout, depression, commitment, and work engagement. Work & Stress 22: 224–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, Thomas, Noam Angrist, Rafael Goldszmidt, Beatriz Kira, Anna Petherick, Toby Phillips, Samuel Webster, Emily Cameron-Blake, Laura Hallas, Saptarshi Majumdar, and et al. 2021. A global panel database of pandemic policies (Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker). Nature Human Behaviour 5: 529–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, Andrew F. 2018. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Jia, Jack Ting-Ju Chiang, Yihao Liu, Zheng Wang, and Yating Gao. 2023. Double challenges: How working from home affects dual-earner couples’ work-family experiences. Personnel Psychology 76: 141–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Woosang, and Kamala Ramadoss. 2017. The Job Demands–Control–Support Model and Job Satisfaction Across Gender: The Mediating Role of Work–Family Conflict. Journal of Family Issues 38: 52–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Labour Organization. 2012. ISCO 08. International Standard Classification of Occupations. Structure, Group Definitions and Correspondence Tables. Available online: https://webapps.ilo.org/ilostat-files/ISCO/newdocs-08-2021/ISCO-08/ISCO-08%20EN%20Vol%201.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- International Labour Organization. 2021. Work in the Time of COVID. International Labour Conference (109th, Geneva, Switzerland). Available online: https://labordoc.ilo.org/discovery/fulldisplay/alma995128992102676/41ILO_INST:41ILO_V2 (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Investopedia. 2022. White Collar: Definition, Types of Jobs, and Other “Collar” Types. Available online: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/w/whitecollar.asp (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Investopedia. 2023a. Blue-Collar vs. White-Collar: What’s the Difference? Available online: https://www.investopedia.com/articles/wealth-management/120215/blue-collar-vs-white-collar-different-social-classes.asp (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Investopedia. 2023b. What Is Blue Collar? Definition and Job Examples. Available online: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/b/bluecollar.asp (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Janssen, Peter P. M., Maria C. W. Peeters, Jan de Jonge, Inge Houkes, and Gladys E. R. Tummers. 2004. Specific relationships between job demands, job resources and psychological outcomes and the mediating role of negative work-home interference. Journal of Vocational Behavior 65: 411–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeleff, Maren, Marianna Traugott, Elena Jirovsky-Platter, Galateja Jordakieva, and Ruth Kutalek. 2022. Occupational challenges of healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative study. BMJ Open 12: e054516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Elizabeth R., and Ashley V. Whillans. 2022. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Satisfaction of Workers in Low-Wage Jobs. Harvard Business School Working Paper, No. 23-001. Available online: https://www.hbs.edu/faculty/Pages/item.aspx?num=62684 (accessed on 19 February 2024).

- Kerman, Katja, Christian Korunka, and Sara Tement. 2022. Work and home boundary violations during the COVID-19 pandemic: The role of segmentation preferences and unfinished tasks. Applied Psychology 71: 784–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi, Shinnosuke, Sagiri Kitao, and Minamo Mikoshiba. 2021. Who suffers from the COVID-19 shocks? Labor market heterogeneity and welfare consequences in Japan. Journal of the Japanese and International Economies 59: 101–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korunka, Christian, Bettina Kubicek, Wilmar B. Schaufeli, and Peter Hoonakker. 2009. Work engagement and burnout: Testing the robustness of the Job Demands-Resources model. The Journal of Positive Psychology 4: 243–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küppers, Lucas, Julian Göbel, Benjamin Aretz, Monika A. Rieger, and Birgitta Weltermann. 2024. Associations between COVID-19 Pandemic-Related Overtime, Perceived Chronic Stress and Burnout Symptoms in German General Practitioners and Practice Personnel-A Prospective Study. Healthcare 12: 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leo, Carlo Giacomo, Saverio Sabina, Maria Rosaria Tumolo, Antonella Bodini, Giuseppe Ponzini, Eugenio Sabato, and Pierpaolo Mincarone. 2021. Burnout among healthcare workers in the COVID-19 era: A review of the existing literature. Frontiers in Public Health 9: 750529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Vigouroux, Sarah, Astrid Lebert-Charron, Jaqueline Wendland, Emilie Boujut, Céline Scola, and Géraldine Dorard. 2022. COVID-19 and parental burnout: Parents locked down but not more exhausted. Journal of Family Issues 43: 1705–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llorens, Susana, Arnold B. Bakker, Wilmar Schaufeli, and Marisa Salanova. 2006. Testing the robustness of the Job Demands-Resources model. International Journal of Stress Management 13: 378–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loustaunau, Lola, Lina Stepick, Ellen Scott, Larissa Petrucci, and Miriam Henifin. 2021. No choice but to be essential: Expanding dimensions of precarity during COVID-19. Sociological Perspectives 64: 857–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martucci, Sara. 2023. He’s working from home and I’m at home trying to work: Experiences of childcare and the work–family balance among mothers during COVID-19. Journal of Family Issues 44: 291–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meijman, Theo F., and Gijsbertus Mulder. 1998. Psychological aspects of workload. In Handbook of Work and Organizational Psychology. Edited by Pieter Johan Diederik Drenth and Henk Thierry. London: Psychology Press, pp. 5–33. [Google Scholar]

- Morgeson, Frederick P., and Stephen E. Humphrey. 2006. The Work Design Questionnaire (WDQ): Developing and validating a comprehensive measure for assessing job design and the nature of work. Journal of Applied Psychology 91: 1321–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostert, Karina, Maria Peeters, and Izel Rost. 2011. Work–home interference and the relationship with job characteristics and well-being: A South African study among employees in the construction industry. Stress and Health 27: e238–e251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagata, Shohei, Hiroki M. Adachi, Tomoya Hanibuchi, Shiho Amagasa, Shigeru Inoue, and Tomoki Nakaya. 2021. Relationships among changes in walking and sedentary behaviors, individual attributes, changes in work situation, and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan. Preventive Medicine Reports 24: 101640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Bureau of Statistics. 2022. Average Annual Wages of Employees Above the Scale in 2021. Available online: https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/zxfb/202302/t20230203_1901474.html (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Pamidimukkala, Apurva, and Sharareh Kermanshachi. 2021. Impact of COVID-19 on field and office workforce in construction industry. Project Leadership and Society 2: 100018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ráthonyi, Gergely, Karolina Kósa, Zoltán Bács, Kinga Ráthonyi-Ódor, István Füzesi, Péter Lengyel, and Éva Bácsné Bába. 2021. Changes in workers’ physical activity and sedentary behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability 13: 9524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardeshmukh, Shruti R., Dheeraj Sharma, and Timothy D. Golden. 2012. Impact of telework on exhaustion and job engagement: A job demands and job resources model. New Technology, Work and Employment 27: 193–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şişman, Hamide, Esma Gökçe, Refiye Akpolat, Dudu Alptekin, Derya Gezer, and Sevban Arslan. 2023. Survey on the effects of work in COVID-19 clinics on anxiety-depression and family-work conflicts. Journal of Family Issues 44: 2981–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayal, Deeksha, and Aasha Kapur Mehta. 2023. The struggle to balance work and family life during the COVID-19 pandemic: Insights based on the situations of working women in Delhi. Journal of Family Issues 44: 1423–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsen, Mung Khie, Manli Gu, Chee Meng Tan, and See Kwong Goh. 2023. Homeworking and employee job stress and work engagement: A multilevel analysis from 34 European countries. Social Indicators Research 168: 511–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoef, Nico. C., M. De Ruiter, Robert J. Blomme, and Emile. C. Curfs. 2021. Relationship between generic and occupation-specific job demands and resources, negative work−home interference and burnout among GPs. Journal of Management & Organization 30: 972–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo-Thanh, Tan, Thinh-Van Vu, Nguyen Phong Nguyen, Duy Van Nguyen, Mustafeed Zaman, and Hsinkuang Chi. 2022. COVID-19, frontline hotel employees’ perceived job insecurity and emotional exhaustion: Does trade union support matter? Journal of Sustainable Tourism 30: 1159–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voydanoff, Patricia. 1988. Work role characteristics, family structure demands, and work/family conflict. Journal of Marriage and Family 50: 749–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyas, Lina. 2022. “New normal” at work in a post-COVID world: Work–life balance and labor markets. Policy and Society 41: 155–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, Toby D., and Paul R. Jackson. 1995. New manufacturing initiatives and shopfloor job design. In The Changing Nature of Work. Edited by A. Howard. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, pp. 139–74. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Bin, Yukun Liu, Jing Qian, and Sharon K. Parker. 2021. Achieving effective remote working during the COVID-19 pandemic: A work design perspective. Applied Psychology 70: 16–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinert, Christoph, Christian Maier, Sven Laumer, and Tim Weitzel. 2014. Does teleworking negatively influence IT professionals?: An empirical analysis of IT personnel’s telework-enabled stress. Paper presented at the SIGSIM-CPR ’14. Proceedings of the 2014 Conference on Computers and People Research, Singapore, May 9. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, Stephen, George Michaelides, Ilke Inceoglu, Karen Niven, Aly Kelleher, Elizabeth Hurren, and Kevin Daniels. 2022. Satisfaction with one’s job and working at home in the COVID-19 pandemic: A two-wave study. Applied Psychology, advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. 2020. Director-General’s Opening Remarks at the Media Briefing on COVID19-March 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020 (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Yu, Jun, and Yihong Wu. 2021. The impact of enforced working from home on employee job satisfaction during COVID-19: An event system perspective. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18: 13207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, Hao, Yuxi Zhang, Hui Zhou, Lijun Wang, Zihan Zhang, Zijia Tan, Longmei Deng, and Thomas Hale. 2022. Chinese Provincial Government Responses to COVID-19 (BSG-WP-2021/041). BSG Working Paper Series. Available online: https://www.bsg.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2022-01/BSG-WP-2021-041-v2.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Zhang, Qi, Xinxin Zhang, Qi Cui, Weining Cao, Ling He, Yexin Zhou, Xiaofan Li, and Yunpeng Fan. 2022. The unequal effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on the labour market and income inequality in China: A multisectoral CGE model analysis coupled with a micro-simulation approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19: 1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuzanek, J. 1998. Time use, time pressure, personal stress, mental health, and life satisfaction from a life cycle perspective. Journal of Occupational Science 5: 26–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).