Abstract

Social trust, understood as a moral evaluation of the trustworthiness or faith in the benevolence of one’s fellow citizens, represents a value that has been the subject of intense debate and growing research attention in recent decades. Nevertheless, the conceptual roots of trust and the opposing arguments that challenge them are rarely examined. This paper takes the necessary step of examining the evolution of the concept of trust. It identifies five distinct sub-perspectives on trust, tracking some of their assumptions, conceptualizations, and dimensions: societal, civic, institutional, personality, and rational choice perspectives. It also provides a brief historical overview of theoretical perspectives and influences among a number of relevant authors. It concludes with a brief discussion of the relevance of conceptual analysis and its connections with ongoing debates on trust. The aim of the article is to address the ambiguity and provide a conceptual framework for researchers to situate their research within the extensive literature on trust.

1. Introduction

“Confusion continues with an increased mixture of approaches and perspectives.”Barbara Misztal (1996, p. 13)

Social trust is one of the core concepts within the social sciences. As a phenomenon of modern societies (Barbalet 2019, p. 13), it serves as a critical indicator of social cohesion (Putnam 1993, 2000; Larsen 2013), operates as a moral compass for evaluating others (Barber 1983, p. 19), manifests as a belief in strangers (Uslaner 2002, p. 4), or functions as a cognitive assessment of the trustworthiness of those with whom we seek relational engagement (Hardin 2006, pp. 3–13). Fundamentally, trust constitutes a foundational element of social interaction and action, as “without trust, we would have been paralyzed by inaction” (Hawley 2012, p. 1).

The study of trust has seen widespread application, with a marked increase in scholarly articles on the topic in recent decades (Uslaner 2018a, p. 5). However, its conceptualization often remains ambiguous and is interpreted in disparate ways (Nannestad 2008, p. 414). This is evident in the numerous forms attributed to trust, such as political trust in institutions, particularized trust between individuals, and generalized social trust (Levi 1998; Stolle 2002; Newton et al. 2018; Newton and Zmerli 2011; Uslaner 2018b).1 These diverse interpretations highlight the evolution of trust as a concept through various theoretical perspectives, yet this historical development has also led to significant conceptual ambiguity, posing challenges for researchers (Misztal 1996, p. 13; Barber 1983; Stolle 2002, p. 400; Uslaner 2018a, pp. 5–6; Bauer 2015, p. 4).

This article aims to provide an overview of the modern historical evolution of trust, facilitating a more structured approach for researchers to position their work within this field. To systematically organize the diverse historical perspectives on trust, I will:

- Identify major streams and perspectives, outlining their defining characteristics, definitions, and key dimensions (see Table 1 for definitions).

- Trace and explain the interconnections and influences among key authors.

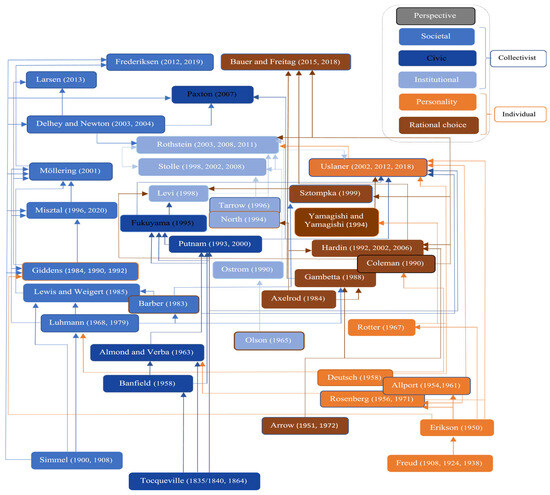

- Map these perspectives and the flow of ideas among representative authors, illustrating their historical development (see Figure 2 Historical Development).

This article is based on two overarching fundamental observations: First, it is theoretically challenging to encapsulate trust within a single, comprehensive definition. As noted by Margaret Levi (1998, p. 79), “Trust is not one thing and does not have one source. It has a variety of forms and causes.” Furthermore, each perspective operates with its corresponding basic assumptions and the prioritized dimensions and forms derived from them. This is reflected in social science debates on trust.

The Section 2 provides a brief overview of the underlying literature on trust that is used as a point of departure. Section 3 discusses and lays out two generally distinct strands of theoretical approaches—individual and collectivist perspectives, with their subsequent five sub-perspectives. These sub-perspectives will be the subject of a more in-depth analysis, with an emphasis on the historical flow of trust concepts among authors. It also identifies some of the key dimensions of trust within each perspective. The section begins with a table of some representative definitions and concludes with a condensed graphical representation of the development of five perspectives. Section 4 concludes the article by briefly discussing some of the patterns of conceptual influence, their connections to ongoing debates, and possible implications for current research on trust.

2. Materials and Methods

A number of overviews and anthologies on the topic of trust up to 2019 will serve as a data basis for comparisons and interpretations—with a quick run-through of some of the more recent contributions that bear relevance. Insights into the works of some relevant authors within the respective perspective will provide further conceptual material for analysis. The initial brief overviews are those provided by Lewis and Weigert (1985), Delhey and Newton (2003, 2004), and Newton et al. (2018). The following anthologies were used as main sources: Gambetta’s (1988b), Cook’s (2001), Uslaner’s (2018b), and Sasaki’s (2019). The monographs employed, which include extensive sections on the conceptual development of trust, are mainly the works of Bernard Barber (1983), Barbara Misztal (1996), Adam Seligman (1997), Piotr Sztompka (1999), Eric Uslaner (2002), Russell Hardin (2002), and Guido Möllering (2006).

3. Tracking the Conceptual Development of Trust

3.1. Individual vs. Collectivist Perspectives on Trust

There are a number of ways to distinguish the main approaches in which authors conceptualize trust. In my view, one of the most analytically comprehensive and useful frameworks for organizing perspectives on trust is proposed by Delhey and Newton (2003, pp. 94–101), who differentiate between (1) individual and (2) collectivist perspectives. Whereas individual approaches view trust as a phenomenon related to individuals, their core personality, rationality, identity, interests, individual dispositions, or social orientations, collective approaches tend to view trust as a property of societies, communities, social systems, and their inherent institutions. Both conceptualizations assume that the study of trust is predominantly either a bottom-up or a top-down research enterprise. Alternatively, as shown in some recent studies (Larsen 2013; Frederiksen 2019) and discussed in the last Section 4, there are advantages and challenges in combining these levels, their perspectives, and underlying dimensions. Nevertheless, it seems reasonable to use the general epistemological orientations of these two schools of thought as an initial starting point for mapping the conceptual development of trust. This classification will, therefore, generally serve as the basis for identifying, mapping, and discussing trust perspectives in the following sections.

3.1.1. Individual Perspectives

The first category, referred to as individual perspectives, conceptualizes trust primarily as a matter of personality or rationality. The first approach, often categorized in the literature as personality theory (Delhey and Newton 2003, p. 95), is here termed:

- Personality perspective: The central premise of this perspective is that trust, as a core personality trait, is predominantly developed during early childhood socialization, with subsequent life experiences, including traumatic events, potentially altering an individual’s trust orientation toward the social environment (Erikson 1950; Uslaner 2002; Delhey and Newton 2003).

- Rationalchoice perspective: In contrast, the second strand within individual perspectives conceptualizes trust not as a personality trait shaped through socialization but as a series of individual events and cognitive evaluations of trustworthiness. This approach, often referred to as the “rational choice perspective” (Dunn 1993, p. 641; Möllering 2001, pp. 412–13; Misztal 2020, pp. 342–47), views trust as a more or less rational pursuit of interests.

3.1.2. Collectivist Perspectives

Opposed to the basic assumptions above, do authors who adhere to collectivist perspectives do not necessarily perceive trust as an inherent attribute, trait, or disposition of individuals? Instead, they regard it as a property of collectives or social systems. For these scholars, trust is fundamentally a matter of norms, rules, and ethical habits that shape society (Fukuyama 1995, p. 7). Furthermore, it is about social reciprocity (Putnam 2000, p. 21), different types of role expectations (Barber 1983), social relations and the obligations inherent to them (Misztal 1996, p. 21), or acknowledging a larger picture, trust permeates social cohesion (Larsen 2013). The underlying epistemological and methodological logic of collectivist perspectives can be seen as inversely mirroring that of individualist approaches to trust. Individualist approaches generally prioritize the analysis of personality and rationality in trust, with varying degrees of consideration for collective norms and social structures. Collectivist perspectives similarly do not disregard the role of individual trust in their research frameworks. However, they tend to view trust as a social and not an individual reality, and as a matter of societal, community, or institutional structures. More specifically, the societal view focuses on social institutions, collectives, or whole societies. The emphasis on communal structures focuses on community or civic culture. Scholars who focus on institutional structures see trust as largely linked to the political institutions of the state. Collectivist threads on trust will thus be divided into three conceptual subcategories: societal, civic, and institutional sub-perspectives:

- A societal sub-perspective: The basic assumptions of this perspective can be subsumed under the view that trust represents a social reality, encompassing emotional, cognitive, and behavioral dimensions of human experience (Lewis and Weigert 1985, 2012). In this vein, trust is primarily related to social circumstances in which individuals act, social institutions in which they participate, and societies with their social orders, divisions, and inequalities in which they live. The theoretical foundations of this perspective can be traced back to the concepts of collective consciousness, division of labor, and organic solidarity within modern societies as articulated by Émile Durkheim and, more explicitly, to Georg Simmel’s inter-subjective sociological analysis of trust. At the beginning of Section 3.2.3, I briefly discuss their influence and trust-related conceptualizations for the societal thread on trust.

- A civic sub-perspective: This perspective differs from the aforementioned societal views in that it places greater emphasis on the role of associative life within communities and their citizens in fostering trust, rather than focusing on the perceived efficacy of modern social institutions or whole societies. The attitudes of “civicness” (Putnam 1993) and “sociability” (Fukuyama 1995), norms of reciprocity, and the trustworthiness of citizens working together on equal footing, which result in the bridging republican culture of trust, are among the principal concerns for these authors. Their contemporary work is largely rooted in the conceptual framework established by Alexis de Tocqueville, exploring the formation of trusting bonds among citizens as the interplay between their participation, civil society, and democratic institutions.

- An institutional sub-perspective: A recent development among the three collective perspectives is the institution-oriented view on trust between citizens. This view explores and largely associates trust with the political institutions of the state and their role in creating or sustaining social trust. Some authors of this perspective conceptualize trust itself as an informal institution (Rothstein 2013, p. 1011). The central trust-related concepts and measures within this thread include the quality of government, corruption, and the perceived impartiality of political institutions (Hooghe and Stolle 2003; Rothstein and Stolle 2008; Rothstein 2013).

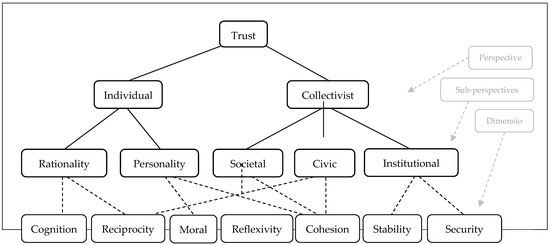

The following section provides a more detailed examination of these five sub-perspectives on trust and their respective developments. This analysis will include an introductory overview of some influential trust conceptualizations and their inherent dimensions (see Table 1), building on from the summary structuring of the above perspectives, sub-perspectives, and some of their inherent dimensions (see Figure 1 below), and a subsequent historical mapping of conceptual influences among some of the seminal authors (Figure 2).

Table 1.

Brief historical overview of trust conceptualizations representing different perspectives and sub-perspectives with their inherent dimensions.

Figure 1.

A mapping of the major perspectives, sub-perspectives, and some of the underlying dimensions of trust.

Figure 2.

Historical mapping of trust perspectives and sub-perspectives with conceptual interactions between authors (Simmel 1900, [1908] 2013; Luhmann 1968, 1979; Barber 1983; Lewis and Weigert 1985; Giddens 1984, 1990, 1992; Misztal 1996, 2020; Möllering 2001; Delhey and Newton 2003, 2004; Larsen 2013; Frederiksen 2012, 2019; de Tocqueville [1835] 1864, [1840] 1956, [1835] 1998; Banfield [1958] 1967; Almond and Verba 1963; Putnam 1993, 2000; Fukuyama 1995; Paxton 2007; Olson [1965] 1971; Ostrom 1990; North 1994; Tarrow 1996; Levi 1998; Stolle 1998, 2002; Rothstein and Stolle 2008; Rothstein 2011, 2013; Arrow 1951, 1972; Axelrod 1984; Gambetta 1988b; Coleman [1990] 1994; Hardin 1992, 2002, 2006; Yamagishi and Yamagishi 1994; Sztompka 1999; Bauer and Freitag 2015, 2018; Freud 1908, 1924, 1938; Erikson 1950; Rosenberg 1956; Rosenberg and Simmons 1971; Allport [1961] 1965, [1954] 1979; Deutsch 1958; Rotter 1967; Uslaner 2002, 2012, 2018a, 2018b).

3.2. Toward a Historical Mapping of Trust’s Main Dimensions

3.2.1. The Individual Personality Perspective Erikson—Allport—Rosenberg—Uslaner: Cohesion and Morality

The contributions of the personality perspective view trust as a personality trait of individuals that is predominantly learned through early childhood socialization (Erikson 1950, pp. 80–81, 219–22; Allport [1961] 1965, pp. 78–79, 89; Uslaner 2002, pp. 77, 92). To illustrate this diverse, originally sociopsychological approach, we can turn to a passage by Gordon Allport ([1954] 1979, p. 299):

“The child who feels secure and loved whatever he does, and who is treated not with display of parental power (…), develops basic ideas of equality and trust. Not required to repress his own impulses, he is less likely to project them upon others (…)”.

Normative influencing factors or the moral dimension of personality formation are generally acknowledged as a valid area of study. Yet, “we do not need to deny the existence of group norms and group pressure in order to insist that each person is uniquely organized” (Allport [1954] 1979, p. 40). The fundamental ideas of this perspective on trust can be traced back to at least the work of Erik Erikson. Some of his ideas extend even further into the domains of anthropology (Erikson 1950, pp. 95–97) and Sigmund Freud’s theory of sexuality (Erikson 1950, pp. 11–13). Erikson’s analysis of basic trust arguably represents one of the most significant sociopsychological accounts of trust from an individual-theoretical perspective (Erikson 1950, pp. 219–22). According to his theory, the child’s introduction to the social world begins with the gradual learning to trust familiar care-providing figures. As Erikson states in his work (Erikson 1950, p. 219): “The infant’s first social achievement, then, is his willingness to let the mother out of sight without undue anxiety or rage, because she has become an inner certainty as well as an outer predictability.”

In parallel with these learning processes, which can facilitate emotional bonding and social cohesion, the initial encounters with moral norms occur. The child’s initial tests of ethical boundaries frequently manifest as biting, frustration, and outbursts of anger. “Out of this, therefore, comes that primary sense of badness,” writes Erikson (1950, p. 220). The gradual establishment of fundamental patterns of trust and moral rules of trustworthiness not only fosters familiarity and a sense of belonging but also contributes to the formation of identity. As summarized by Erikson (1950, p. 221): “This forms the basis in the child for a sense of identity which will later combine a sense of being ‘all right’, of being oneself, and of becoming what other people trust one will become.”

Erikson’s conceptualization of trust is observable in several instances within Allport’s contributions to the field of personality development and prejudice (Allport [1961] 1965, p. 78; [1954] 1979, p. 299). He identifies the development of basic trust as a prerequisite for the formation of a socialized personality and the maintenance of group cohesion. Furthermore, he suggests that the absence of trust may contribute to the formation of prejudices against other out-groups (Allport [1961] 1965, p. 79; [1954] 1979, pp. 297–311). “There is some evidence that children lacking basic trust in early life are prone to develop in later childhood a suspiciousness of nature, including prejudice against minority groups.”

The ideas of the personality perspective on trust can also be found in the political psychological works of Morris Rosenberg (1956). Additionally, he has a significant impact on the other perspectives within empirical trust research (Almond and Verba 1963, p. 261). In his article on misanthropy and political ideology, he developed a scale for measuring “faith in people,” consisting of five questions. The initial question being (Rosenberg 1956, p. 690): “Some people say that most people can be trusted. Others say you can’t be too careful in dealings with people. How do you feel about it?” For Rosenberg, a moral dimension relevant to trusting behavior and attitudes toward human nature appears to be pertinent (Rosenberg 1956, p. 695). Julian Rotter’s “Interpersonal Trust Scale” appears to be in alignment with both Erikson’s and Rosenberg’s conceptualizations of trust as a learned moral attitude toward human nature. He extends the conceptualization of Erikson’s basic trust, which is associated with early childhood learning, to encompass other, later influences on trust (Rotter 1967, p. 653). A subsequent interpretation of this understanding of trust is the observation that “generalized attitudes of trust extend beyond the boundaries of face-to-face interaction and incorporate people who are not personally known” (Stolle 2002, p. 403).

The influence of the individual personality perspective is evident in contemporary trust research within social science. A notable example is the contribution of Eric Uslaner. His conceptual framework includes distinguishing between particularized, strategic, or knowledge-based trust, and generalized, moralistic trust, a conceptualization that is repeatedly explored in his studies (Uslaner 2002, pp. 3–5, 9–11, 21–22; 2012, p. 7; 2018a, p. 4). Uslaner draws upon a diverse range of influences; for instance, in his definition of moralistic trust, he references earlier works by Fukuyama (Uslaner 2002, p. 18) as well as Yamagishi and Yamagishi (Uslaner 2002, p. 16), which methodologically integrate socio-psychological, experimental, social, and rational choice frameworks regarding trust. Here, the moral dimension is prominently highlighted. Uslaner sees moralistic trust as “the belief that others share your fundamental values and therefore should be treated as you wish to be treated by them” (2002, p. 18). Furthermore, Uslaner references Deutsch’s experimental research on trust (Uslaner 2002, pp. 49, 191). He constructs his arguments based on the foundational ideas of Erikson (Uslaner 2002, pp. 76–77) and Rotter (Uslaner 2002, pp. 6, 50), and draws extensively from Allport’s work (Uslaner 2002, pp. 11–24). While Uslaner critiques Rosenberg’s analysis, he also integrates it significantly into his own research framework.2

The proposition arising from the aforementioned threads of influence is as follows: Within the framework of the personality perspective and its varied traditions, it is evident that there are at least two dimensions of trust that are identifiable and significant for this comprehensive analysis. First, the cohesive dimension of trust is primarily related to personality stability, and individual and group identity. Individuals trust others because they feel the bond of belonging to the same imagined community. Second, there is the distinct moral dimension of trust, which is acquired through socialization. Individuals trust others when they feel they share a moral community based on some fundamental values. This demarcates the foundational principles of this tradition from the fundamental concepts of the subsequent influential trust perspective, which is rooted in rational choice assumptions.

3.2.2. Individual Rational Choice Perspective Arrow—Gambetta—Hardin: Cognition and Reciprocity

The theoretical and empirical contributions that I refer to here as the rational choice perspective on trust are based on the premises of “individual preference” (Barbalet 2019, p. 13), the cognition that precedes trusting behavior (Cook and Santana 2018, p. 253), or the “encapsulation of interest” (Hardin 1992, p. 153; 2006, pp. 18–20).3 Trust is fundamentally seen as cognition in the sense of a probabilistic evaluation (Gambetta 1988a, pp. 217–18, 230–35) of trustworthiness—or a “cognitive judgment”, which is based on individually perceived facts (Hardin 2002, p. 110).

Some of the principal concepts of the rational choice perspective are traceable in the works of neoclassical economics that are grounded in “bounded rationality” (Simon 1957). In particular, the analyses of individual decisions and exchanges conducted by Kenneth Arrow demonstrate the influence of this perspective (Arrow 1951, 1972). The latter can perhaps provide a concise illustration of the conceptual trajectory that connects neoclassical economic theory to more contemporary investigations into trust and rationality. Arrow further developed the concept of aggregating social decisions from individual preferences, as observed in market transactions or voting behavior, to encompass the allocation of resources to various public goods. The concept of trust gradually becomes incorporated into this theoretical framework. Arrow (1972, pp. 345–46, 57; [1974] 1997, p. 23) understands trust as a form of intangible public good and an implicit key component of almost every transaction. This insight can be found in a number of subsequent works on trust that largely incorporate this relational perspective, including Gambetta (1988a, p. 229) and Hardin (2006, p. 83), as well as others (see, for example, Knack and Keefer 1997, p. 1252).

Additionally, two conceptual coordinates illustrate the diversity of rational choice approaches to trust.4 These include the evolutionary game theory approach to cooperation by Robert Axelrod (1984) and the sociological structural approach to rationality in James Coleman’s ([1990] 1994) theory of social action. Coleman’s generally probabilistic view of trust—as “nothing more or less than the considerations a rational actor applies in deciding whether to place a bet” (Coleman [1990] 1994, p. 99)—can be demonstrated in a number of subsequent studies. These include Hardin (2002, pp. 13, 17), Piotr Sztompka (1999, p. 25), and more recently Paul Bauer, who places emphasis on the probability, but not the behavioral component, of Coleman’s concept of trust (Bauer 2015, p. 6; Luhmann 1988, pp. 14, 45). In contrast to Coleman’s approach, Axelrod’s analysis emphasizes the role of reciprocity as a crucial substitute for trust in cooperative relationships. He notes (Axelrod 1984, p. 174): “[As in evolutionary process], there is no need to assume trust between the players: the use of reciprocity can be enough to make defection unproductive.” This concept of cooperative permanence as a substitute for or precursor to trust is also present in other presentations of the rational choice perspective on trust. Hardin (2002, pp. 137–38) and Gambetta (1988a, pp. 225–27) provide two illustrative examples.5

In his concluding summary of his interdisciplinary trust compendium, Gambetta synthesizes some conceptual coordinates using this probabilistic definition (Gambetta 1988a, p. 217): “Trust (or, symmetrically, distrust) is a specific level of the subjective probability with which an agent assesses that another agent or group of agents will perform a particular action, (…) before he can monitor such action.” However, the probability component and cognition as a basis for trust cannot always be easily separated from the belief component in Gambetta’s work (Gambetta 1988a, p. 219). Both can be associated with cognitive uncertainty and ignorance. This is due to the fact that the actions of others are inherently uncertain future events. It is not feasible to exercise complete supervision or control over the actions of others.

Alternatively, another approach to trust from the rational choice perspective is presented by Hardin. The primary themes of his approach include the reformulation of trust as trustworthiness, the focus on encapsulated interest, and the emphasis on trust as a context-dependent, cognitive phenomenon of exchange. Hardin posits that the primary requisite for enduring trust relationships is reciprocity in the form of the bundling of mutual interests. In other words, if one wishes for another to fulfill a trust placed in them, it is necessary for the other to “encapsulate” their interest in the interest of the first (Hardin 2006, pp. 13–25).

Both Gambetta and Hardin critically rely on a number of different influences, as previously mentioned, including analyses by Arrow (1951, 1972). He implicitly understands trust as a “public good” and regards trust relationships as essentially based on “agreement” (Arrow [1974] 1997, pp. 23, 26; Hardin 2001, pp. 11, 22). These arguments posit that trust is primarily concerned with cognition, preferences, and the reciprocity of interests between individuals. Furthermore, both Gambetta’s and Hardin’s arguments appear to have a significant bearing on more recent discourse on trust. Gambetta and, more explicitly, Hardin and his trust model of encapsulated interest, provide a conceptual reference point for Yamagishi and Yamagishi in their “theory of trustfulness rather than trustworthiness” (Yamagishi and Yamagishi 1994, p. 139). Correspondingly, more recent integrations of these concepts can be found in the contributions of Paul Bauer and Markus Freitag. Their analyses reflect Hardin’s situation-specific, strategic perspective (Bauer 2015, pp. 5, 7; 2021; Bauer and Freitag 2018, pp. 15–16) and Gambetta’s probabilistic approach to trust and distrust (Bauer 2015, pp. 7, 9).

3.2.3. Collectivist Societal Perspective Simmel–Luhmann–Giddens–Misztal: Cohesion and Reflexivity

Trust is not something that I, as an individual, simply carry around with me and give or withhold; rather, it is a fundamental social mechanism that exists collectively and that we can mutually use—such as in the benevolent leap of faith toward strangers, the bonding and bridging of the intangibility of social relations, social institutions, and society itself. This is the basic assumption of authors analyzing trust from a societal perspective. Some of its core ideas can be traced back to the work of Durkheim and Simmel.

Interestingly, Durkheim does not write explicitly about trust. But he does argue for an important moral element in modern societies. For him, these are based on an ‘organic solidarity’ between individuals, rooted in our interdependence of roles and social division of labor. Durkheim’s position is that every society is in fact a moral society, and this is where although not explicitly mentioned, trust is to be found as a moral collective mechanism of social order in our modern terms (Durkheim 1984, pp. 172–74; Misztal 1996). The influence of his conceptualization can be seen in the association of trust with the boundaries of a ‘moral community’ in contemporary writings on trust. The unconvincing part of this conceptualization is that it does not acknowledge, that in modern societies, a plurality of moral systems actually coexists.

Simmel (1950), on the other hand, explicitly analyses trust in several passages. In his view, as we can see from his highly perceptive but sometimes contradictory writings, societies are rather bricolages of moral systems, and intersubjective pluralism is the name of the game. The phenomenon of trust operates at the macro level of societies or nations, but also at the mezzo and organizational levels within social classes, ethnic groups, or interest-based associations. His work represents the first more explicit examination of trust as a concept within the social sciences and provides an important foundation for the arguments of the societal perspective and others (Misztal 1996, pp. 49–50). To demonstrate this, he identifies three core dimensions of trust, which I summarize as follows:

- Trust is a socially cohesive phenomenon. Simmel (1950, p. 318) states: “Confidence, evidently, is one of the most important synthetic forces within society.” This theme of the cohesive effect of trust is reiterated in subsequent societal-oriented literature on trust and beyond (Luhmann 1979, pp. 18–23; Misztal 1996, pp. 50–51; Uslaner 2002, pp. 1–3).

- Trust is also a cognitive phenomenon. It functions as a hypothesis that frames our future behavior and as an “intermediate between knowledge and ignorance about a man” (Simmel 1950, p. 318). This is one of the most significant observations regarding trust that can be found in contemporary writings and across perspectives.

- Trust is imbued with an enigmatic element of faith. Simmel (ibid.) states: “There is, to be sure, also another type of confidence. (…) This type is called the faith of one man in another.” This component of trust appears in the subsequent literature under various names. For example, Midori and Toshiro Yamagishi refer to it as general trust or “a belief in the benevolence of human nature in general” (Yamagishi and Yamagishi 1994, p. 139).

These fragments of Simmel’s work did not exert any discernible influence for a considerable period of time. The concept of trust as a central theme within social science re-entered contemporary social theory discourse through the exemplary works of Niklas Luhmann and Bernard Barber (see Figure 2). Luhmann, who incorporates the social intangibility of trust into the vocabulary of his systems theory, asserts that system boundaries are in fact trust boundaries. He essentially sees trust as a learned mechanism that reduces the social complexity we are confronted with and restores our symbolic control over the social world (Luhmann 1968, pp. 21–27).

The influence of Simmel can be seen in several places in Luhmann’s analysis (Luhmann 1968, pp. 23, 42, 60; Möllering 2001, pp. 408–9). For example, like Simmel, Luhmann argues that trust contains elements that cannot be fully explained by rationality or purely cognitive processes. Trust is based on incomplete information. This leads to uncertainty, which is overcome by “overstretching” this information through trust, which socially reflexively restores the predictability of social life. For Simmel, as shown above, trust is a complex social phenomenon that encompasses both knowledge and ignorance. Similarly, Luhmann observes that the study of contemporary societies should not be concerned solely with individual micro-events or personal trusting attitudes. He asserts that the important reality of trust extends beyond the individual (Luhmann 1968, p. 43). The essential example of this is systemic trust, which is characterized by the reflexivity of individuals or, as Luhmann persuasively puts it, trust in the trust of others (Luhmann 1968, p. 68).

Barber’s (1983) conceptualization of trust is similar to Luhmann’s. Both tend to examine trust as an expectation with a cohesive effect on the maintenance of social systems which are constituted through the reflexivity of social actors (Luhmann 1968, pp. 22–23; Barber 1983, pp. 10–19). Barber’s essential contribution is the analytical parallel of three dimensions, namely moral, cognitive, and emotional, with three types of trust-related expectations. These types anticipate different types of trust relationships that we encounter in social and institutional contexts (Barber 1983, pp. 9–10). The first example is the ‘moral’ expectation that the natural and moral social order, as we know it, will continue. Second is the more ‘technical’ or cognitive expectation that others, for example, ‘experts’ and politicians, will perform their roles competently. Finally, we expect others to be benevolent and socially inclusive: we feel, hope, and expect them to fulfill what we see as a fiduciary duty, at least sometimes putting our or others’ interests before their own.

Like Simmels, Luhmann’s and Barber’s contributions have been influential in the subsequent societal discourse on trust in the social sciences. David Lewis and Andrew Weigert, to cite the first of many examples, define trust as an “irreducible and multidimensional social reality” (Lewis and Weigert 1985, p. 968). Their typology of trust encompasses two axes of trust formation—emotionality and rationality, both of which are grounded in reflexivity and provide an important unifying social coherence for actors and groups. Anthony Giddens, to name another, positions the concept of trust as a social reality and the notion of reflexivity as its important dimension within his conceptualization of modernity.6 He incorporates Simmel’s perspective by positioning trust between “weak inductive knowledge,” and a form of belief (Giddens 1992, pp. 24–27, 33–34). For Giddens (1992, p. 34), trust is about reliability and reflexivity. It relates to persons or systems. For the former, it is socially materialized as a belief in the affection or love of another, regarding the latter, it aims at the correctness of abstract principles or technical knowledge. This is conceptually parallel to the cognitive expectations of others’ competence in Barber’s typology.

Giddens, like Luhmann, typically associates trust with the characteristics of modernity and distinguishes between personal and systemic trust in abstract systems.7 In Giddens’ view, reflexivity represents a pivotal nexus between modern “disembedding mechanisms” and the indispensable foundation of trust (Giddens 1992, pp. 36–50). In this context, trust is “vested, not in individuals, but in abstract capacities” (Giddens 1992, p. 26). He differs from Luhmann in certain respects, including the manner in which Luhmann associates trust with risk. He posits (Giddens 1992, p. 33): “Trust is basically bound up, not with risk, but with contingency.”

In addition, Barbara Misztal presents an additional conceptualization within the societal perspective on trust. For Misztal, an essential question of trust is that of order (Misztal 1996, p. 25). “In essence, the problem of establishing trust in society is the issue of the conditions necessary for social order and human action to continue.” The fundamental premise of her argument can be summarized as follows (Misztal 1996, p. 95–101): The nature of trust can be examined through the lens of three distinct forms of social order or their constituent elements: (1) stability, (2) cohesion, and (3) cooperation. On the whole, each of these encompasses a range of trust-related practices, including routines for stability, friendships for cohesion, and forms of solidarity for political cooperation.

Furthermore, Misztal makes significant references to Simmel (Misztal 1996, pp. 10, 32, 49–54, 61–63). She interprets Simmel’s concept of trust as “a mechanism which allows us to accept the fiction of order because it functions” (Misztal 1996, p. 63). She links his perspective on trust as “weak inductive knowledge” with the stabilizing function of memory, which both serves to reinforce social cohesion and enables us to cope with uncertainty (Misztal 1996, p. 141). Furthermore, Misztal discusses the role of trust and mistrust as outlined by Luhmann’s theory (Misztal 1996, p. 110). “It seems if there is a need for trust as well as for distrust (Luhmann 1979, pp. 71–75), there is also a need for habit and spontaneity.” She highlights the significant interconnection between systemic trust and reflexivity (Misztal 1996, p. 74).

Some of the more recent authors further develop these arguments from the societal perspective, particularly the concept of reflexivity. Three notable examples are the contributions by Guido Möllering (2001, 2006), Christian Larsen (2013), and Morten Frederiksen (2012, 2019). Möllering draws on the approaches of Simmel, “introducing the concept of suspension (leap) as a mediator between interpretation (bases) and expectation (function)” (Möllering 2001, p. 404). In his interpretation of the leap of faith in the form of a suspension, he also incorporates Giddens’ concepts of active trust, routinization, and reflexivity of the actors (Möllering 2006, pp. 22–26). Larsen’s arguments for social cohesion are based on the perceptions of citizens regarding one another, society, and inequalities. The reflexivity of social actors is of central importance in this context, with trust serving as an indicator of social cohesion. As Larsen (2013, p. 91) puts forth in his argument: “Trust levels and perception of ‘others’ are driven more by social constructions, than by social experience.” Frederiksen, however, employs a different approach to reflexivity, one that is grounded in the ideas of Simmel but also extends them through the lens of Bourdieu’s (1977) concept of disposition and Lamont’s (1992) notion of “boundary work” (Frederiksen 2012). In other words, the reflexive constitution of the “other” is linked to the constitution of “oneself,” “us,” and the formation of identity (Frederiksen 2019, pp. 5–6). The latter, in summary, represents one of the concepts that is importantly intertwined with the trust-related dimension of reflexivity.

3.2.4. The Collectivist Civic Perspective Tocqueville–Banfield–Putnam–Fukuyama: Cohesion and Reciprocity

The basic premise of the communal, or rather civic, perspective on trust can be summarized as follows: Trust is a cohesive phenomenon that is particularly relevant and visible in a community. The rules of associative engagement are important. The social norms and networks at work contribute to the culture of trust. Alexis de Tocqueville is one of the most seminal authors within this tradition. His work is largely concerned with associative life and the “civic sociability” of communities (Putnam 1993, p. 91). Many contemporary authors concerned with trust or social cohesion of modern societies make reference to Tocqueville’s work in one critical way or another (Putnam 1993, p. 11, 88; 2000, p. 24, 48, 78, 122; Uslaner 2002, pp. 4, 31, 83, 87; Misztal 1996, p. 28; Newton et al. 2018, p. 38).

Tocqueville begins his analysis with the egalitarian basis of trusting relationships. Similarly, as with the Scottish moral philosophers from Adam Ferguson to Adam Smith,8 he does not utilize the term ‘trust’ itself, but rather the ‘language of trust’ (Seligman 1997, p. 31). The “equality of conditions” and the mutual recognition of private interests, “properly understood”, are the social premises according to which fellow citizens can trust one other (de Tocqueville [1840] 1956, pp. 1–17; [1835] 1998, pp. 7–29). The emphasis in the civic perspective on trust appears to be primarily on its connection to reciprocity and its associated norms. It is manifested through the associational activities of individuals and can foster the reciprocity of social sentiments. The civic theme of reciprocity as sociability, an essential element in the formation of generalized social trust, can be discerned repeatedly in Tocqueville’s work (de Tocqueville [1840] 1956, pp. 108–9), as in this observation9—”Feelings and opinions are recruited, the heart is enlarged, and the human mind is developed by no other means than by the reciprocal influence of men upon each other. (…) and this can only be accomplished by associations.” The concept of reciprocity emerges later in the civic-oriented social science literature in this vein (Putnam 1993, pp. 182–183): “Generalized reciprocity (… I’ll do this for you now, knowing that somewhere down the road you’ll do something for me’) generates high social capital and underpins collaboration”.

This observation is, therefore, clearly not new. The reciprocal embedding of moral obligations and implicit ethical habits—such as the principle of not cheating—characterizes the investigative interest of authors of the civic perspective who can be placed chronologically between Tocqueville and Putnam, for example, Edward Banfield. His work is an interesting example of a civic perspective. In his analysis, Banfield examines the inverse of social reciprocity. This is the absence of social structures that facilitate the internalization of mutual obligations that extend beyond the immediate interests of the nuclear family. He analyzes Tocqueville’s premises by posing the question of what occurs in the absence of associations (Banfield [1958] 1967, pp. 7–8). Subsequently, Francis Fukuyama refers to this phenomenon as the “missing middle”, describing it as the absence of spontaneous formation of social groups and associations situated “in the region between the family on the one hand and the state on the other” (Fukuyama 1995, pp. 54–55). Banfield illustrates the resilience of this condition as the manifestation of social distrust. The inhabitants of the village community that was the subject of his study adhere to a moral principle that facilitates the self-interest of the nuclear family (Banfield [1958] 1967, p. 85). “Maximize the material, short-run advantage of the nuclear family; assume that others will do likewise.” It would appear that the “familistic” community under discussion is lacking in a civic political culture, as defined by Gabriel Almond and Sidney Verba. These scholars contend that political culture is inherently characterized by trust (Almond and Verba 1963, p. 32). This can be considered a learned and norm-based interpersonal orientation, and, thus, a cultural phenomenon.

The civic perspective thread can broadly be traced from the works of Tocqueville, Banfield, Almond, and Verba to those of Putnam, and beyond.10 Similarly, Fukuyama posits that actors internalize collective expectations by acting beyond their immediate self-interest. The concept of implicit social reciprocity interweaves “all successful economic societies [which] are united by trust” (Fukuyama 1995, p. 9). He makes reference to the sections on the significance of associations as outlined by de Tocqueville ([1840] 1956, pp. 106–10). Fukuyama discusses the “art of associating together” and fundamentally views the level of trust in society as a “single pervasive cultural characteristic” that influences the well-being of nations (Fukuyama 1995, p. 7).

In Putnam’s analysis, social cohesion is a concept that emerges implicitly, while his discussion of social reciprocity is particularly explicit. His conceptualization of social capital is anchored in the premise that social networks have value, particularly in terms of the norms of reciprocity and trustworthiness, as previously discussed by Tocqueville (Putnam 2000, p. 19). Putnam generally considers trust to be a component of social capital and views it as a moral resource that “lubricates cooperation” (Putnam 1993, p. 171). He subsequently develops a valuable conceptual tool for understanding trust mechanisms, namely the distinction between bridging and bonding forms of social capital (Putnam 2000, pp. 22–24).11 For Putnam, reciprocity represents the important component of social capital and is demonstrated by the trust-based principle of cooperation: “I’ll do this for you now, without expecting anything immediately in return” (Putnam 2000, p. 134). It seems to be this reciprocity that underlies civic culture as a kind of sociability. Or, as described by Banfield: The notable absence of the social reciprocity base reveals the communal “inability to create and maintain organization” that would transcend immediate family interests (Banfield [1958] 1967, p. 87).

3.2.5. The Collectivist Institutional Perspective Rothstein—Stolle: Stability and Security

The relatively recent contributions that I call here the institutional perspective on trust are largely concerned with the generation and conditions of trust in relation to political institutions. The argumentative core of this perspective can be summarized as follows: It is the institutional characteristics and perceptions of their impartiality that can influence dimensions such as security and social stability. Such institutions have the potential to influence the level of trust as a social institution among citizens. Order institutions of the state, as defined by Rothstein and Stolle (2008, pp. 445–50), and the officials who represent them can be perceived by citizens as role models for the moral standards of society (Delhey and Newton 2004, p. 4).

In general, the understanding of trust for some institutionally oriented authors does not appear to differ significantly from the more civic or personality-oriented views within social sciences. Bo Rothstein, for instance, as per Uslaner (2002, pp. 9–11, 190–216), Delhey and Newton (2004, pp. 4–5) and indirectly, Douglass North (1994, pp. 359–61)12, asserts (Rothstein 2013, p. 1011) that: “[Trust] can be seen as an informal institution (…) and therefore as a source of social solidarity, creating a belief system according to which the various groups in society have a shared responsibility to provide public goods as well as possibilities for those who happen to be endowed with fewer resources (…)” Institutions—and trust can be in this respect understood as a social, informal institution—provide not only impartiality but also security and stability through rule-based predictability.

Dietlind Stolle also appears to adopt a comparable interpretation of trust (Stolle 2002, p. 397). For numerous authors of this perspective, the question of what constitutes trust is inextricably linked to the question of how trust and social capital can be generated (Rothstein and Stolle, pp. 441–44). Here too, the concept of social capital represents one among a number of frameworks for analysis. However, two key trust-related dimensions appear to be embedded in different ways in arguments from the institutional perspective: stability and security.

In order to facilitate an understanding of conceptual logic, it may be beneficial to provide a brief overview of the historical development of theoretical influences. The theoretical foundations of the institutional perspective can be traced back to two distinct theoretical and empirical streams. The first is social capital theory, as developed by James Coleman ([1990] 1994) and Putnam (1993). The second is the more recent institutionalist-structural approaches in modern political science, as exemplified by Elinor Ostrom (1990), Sidney Tarrow (1996), and Margaret Levi (1998). These approaches generally recognize the role of state institutions as generators of social capital.

Coleman is credited with influencing the rational choice tradition (Cook and Santana 2018, p. 255) and defines social capital in terms of its function. He views social capital as a social structural resource for individuals, embedded “in the structure of relations between persons and among persons” (Coleman [1990] 1994, p. 302). Norms, authority, and trust relationships are integral structural components of social capital (Coleman [1990] 1994, p. 300). Those who adopt an institutional perspective recognize the role of institutions in the embedding of social capital and assess the merits of the civic approach. In his interpretation of Coleman, Rothstein (2011, p. 168) argues: “Social trust as an informal institution is essential if groups or societies are to establish socially efficient formal institutions like the rule of law, impartial civil services, and incorrupt public administrations”.

The second, institutionalist-structural tradition, which is discernible from an institutional perspective, is primarily concerned with the examination of state institutions and their function in democratic participation and legitimacy. Margaret Levi provides an illustrative account of some of the seminal contributions in this regard. Some of the arguments she critically develops are based on different theoretical approaches. These include Fukuyama’s acknowledgment that the state can play a role in fostering social capital among citizens (Levi 1998, p. 83), Coleman’s elaboration of possible mechanisms for building trust through friends’ recommendations or institutional experiences (Levi 1998, p. 84), and Sztompka’s observation of the paradoxes of democracy, where citizens’ distrust can ultimately lead to better institutions (Levi 1998, p. 96). In reference to the historical case of the so-called Canadian conscription crisis during the two world wars, Levi (1998, p. 92) writes: “(…) impartial institutions that include some means to protect minority interests without unduly offending majority concepts of fairness are a necessary but not sufficient condition for the perception of fairness. There must also be some trust built up among conflicting groups.” In his discussion of trust, security, and impartiality, Rothstein draws on her work, as illustrated in this interpretation (Rothstein 2011, p. 94): “Levi shows that large numbers of French Canadians refused to volunteer for the war and that the Quebecois strongly opposed conscription. (…) [possibly believing that] the Anglo-dominated government and army would not treat them impartially. [That] they would be discriminated against or simply used as cannon fodder”.

In the works of Rothstein and Stolle, a number of additional fruitful parallels or significant influences can be identified. The work of Sidney Tarrow (1996; Tarrow and Tilly 2015) and his analyses, which include the argument that “the state plays a fundamental role in shaping civic capacity”, are frequently referenced or interpreted (Tarrow 1996, p. 395) by Rothstein and Stolle (Stolle 2002, p. 10; Rothstein and Stolle 2007, p. 7). In a similar vein, the concepts and contributions of Elinor Ostrom (1990) on the interactions between institutional development and dilemmas of collective action found a foothold in the research and theory of the institutional perspective.13 Similarly, prior to her, the analyses of Mancur Olson ([1965] 1971) with the disentanglement of collective action in relation to public goods, organizations, and group cohesion (Rothstein 2011, p. 48) were also considered.

In summary, the institutional embedding of trust can be defined as the experience of impartiality of state institutions, which creates a sense of fairness, stability, predictability, inclusion, and social security among citizens (Rothstein and Stolle 2008). From fair and respectful officials, people will draw inductive conclusions about fellow citizens and people in general. Feelings of security and stability can, therefore, strengthen generalized social trust and cooperation. Social trust can be seen as an informal institution. While self-interest is important, it does not explain everything. Historical narratives and collective memories are also relevant. However, the perception of others, institutions, and their impartiality can be crucial.

4. Recent Developments and Discussion

4.1. Recent Developments

Different perspectives on trust and their implicitly divergent conceptualizations are still receiving varying degrees of attention from social scientists. Some of their attempts focus on disentangling the pervasive conceptual juggernauts responsible for stalemates, extending research interest to new phenomena such as social disruption or digital environments, or attempting to reconcile constructed conceptual divisions with reframing proposals. As far as the structure of themes and foci is concerned, there are at least four threads of developments in trust research that can be discerned in recent years, with varying degrees of visible association with specific theoretical perspectives or their combinations. (1) The first recent (re)emerging theme is the question of the typology of trust, denoting the revisions and explorations of its different forms and types. (2) The second theme is the issue of methodology, measurement, and ways to better empirically capture and understand trust. (3) The third distinct stream of trust research and conceptualizations is addressing the issues of trust in new digital social environments. The final thread of recent work on trust can be defined as (4) those contributions that extend, reframe and possibly reconcile perspectives on trust.

- (1)

- The focus of recent (and not so recent) typology-oriented efforts is the search for theoretical plausibility and empirical viability of trust concepts. Some of the authors re-examine trust conceptually. Others empirically test the presumed conceptual differences and construct what they believe to be a convincing trust typology. An example of the former is the implementation of Sartori’s (1984) ladder of abstraction, which aims at a universal, interdisciplinary definition of trust (Utthental 2024). Here, trust is differentiated along two axes: one is the distance of the object/subject of trust, and the other is the level of its abstractness/concreteness. The truster’s orientation toward distant, more abstract objects is attributed to the individual’s psychological propensity to trust in general, as seen from the personality perspective, while the second, more concrete trust is assumed to stem from a predominantly evaluative basis of the truster’s capacities, as in trust game experiments from the rational choice perspective.Beyond such efforts associated with a particular perspective on trust, or attempting to bridge them across disciplines, there nevertheless seems to be an emerging general consensus around the formerly divisive perspective-based compartmentalization of what trust is or is not. Most authors seem to generally agree on the conceptual distinction between social trust targeting specific persons, groups, or people, in general, and political trust in varying institutions (Zmerli 2024; Newton et al. 2018).

- (2)

- Methodological discussions arising from or related to different perspectives on trust generally revolve around the question of how to measure and empirically capture trust in a plausible and comprehensive way for such a multidimensional social phenomenon. An exemplary proposal for measurement development methodology is offered by the authors, who build their arguments largely on the premises of the rationality-bound perspective—generally understanding trust as a form of context-dependent subjective probability assessment of the trustworthiness of individuals. Their revisionist measures aim at capturing more specific contextual trust attitudes through additional probing survey questions, such as asking about “parents” instead of “family” in general. This approach is generally based on the rationality-bound universal trust proposition that Truster A trusts Trustee B to do X in context Y (Bauer and Freitag 2018), as opposed to the normative trust assumption that Truster A trusts, as in standard survey questions. This latter approach assumes the existence of an unspecified context-independent general trust attitude among individuals (Uslaner 2015, 2018a). The latter, classically measured with the “most people can be trusted” question or a modification of Rosenberg’s Faith in People Index (Rosenberg 1956), has recently also seen revisionary attempts, such as scaling extensions to 7- or 9-point bipolar scales (Robbins 2024) or the Stranger Face Trust (SFT) questionnaire, which is based on trust responses to specific visual representations of strangers. Once again, these methodological assumptions lean toward more evaluative (rationality-oriented) rather than personality or societal norm-oriented perspectives on trust (Robbins 2019).

- (3)

- After the widespread development of Internet communication and artificial intelligence (AI) since the 1990s, the issue of trust in modern societies faces new research challenges. One of the ubiquitous questions of trust is what trust and its various perspectives actually mean, and how it is generated and maintained in digital social environments. A plethora of studies address and revise the concept of digital trust (Pietrzak and Takala 2021) or relate it to concepts such as reliability, quality, and especially privacy (Paliszkiewicz and Chen 2021). A number of these contributions, such as those focusing on organizational culture, consumer trust in the digital economy, or digital natives’ trust in digital-based systems, seem to build their arguments and models predominantly on the premises of rationality-bound and institutional perspectives on trust. A valid question here is certainly—is there a digital equivalent of offline social trust and online trust as a distinct social reality? What are its main dimensions with respect to historical perspectives on trust? Or is online trust merely an extension of offline social trust with its associated dimensions and perspectives? The study of trust might be experiencing a conceptual and empirical rejuvenation with regard to the increasing application of artificial intelligence models in social life. However, conceptual clarity and empirical viability seem to be lacking in recent studies of digital trust. Here, the topic of AI trustworthiness and trust in specific AI systems, such as health-related expert systems, is fostering empirical research and theoretical rigor (Galle et al. 2021). Nevertheless, it is noteworthy to mention that, as demonstrated before by the conceptual premises of the societal perspective (Section 3.2.3), trust in abstract systems is a concept that is accredited and implicit in the social processes of modernity, and not a novelty phenomenon born specifically with the spread of the Internet and AI systems (cf. Luhmann 1979, 1988; Giddens 1992).

- (4)

- Finally, an important body of recent work is to be found in contributions that extend or reconcile different perspectives on trust. There are a number of papers that generally build on or extend the premises of individual perspectives on trust. As an example, the probabilistic view of trust, which lies within the rationality-bound tradition, has advanced with a number of recent contributions. The majority of these inquiries link the conceptualization of trust to trustworthiness, subjective probability assessment, and cooperation, or are inclined toward a further formalization of trust based on contextual categories (Bauer 2021; Iacono and Testori 2021). The other side of individual-oriented trust research, which is based on the idea of trust as a psychological personality trait, is also experiencing a further vitality of empirical explorations. An exemplary stream of psychological research examines trust as a moral emotion, as in the clinical context of moral injury and the study of trauma and stressor-related disorders (Kadwell and Kerig 2021). Alternatively, regarding the collective perspectives, civic approaches do not seem to be as prevalent as societal and, in particular, institutional-oriented work. Examples of the latter include topics such as the maintenance of social and political trust in institutions in times of profound social or systemic disruptions such as the COVID pandemic (Bargain and Aminjonov 2020; Dhar et al. 2020), the maintenance of organizational trust under conditions of global financial crisis (Gustafsson et al. 2021), or the trust-related relevance of social movements and the state (Fairbrother et al. 2024). Examples of the former, relatively recent work, generally incorporating the premises of societal perspectives, also employs other fruitful trust explorations, such as studies of ethnic diversity, segregation, inequality, and trust among migrants (see Dinesen et al. 2020; Steele et al. 2022). Finally, a considerable amount of effort in recent studies has been directed toward reexamining theoretical assumptions, reconciling divergent perspectives on trust and working against unnecessary or “false dichotomies” (Schilke et al. 2021; Fairbrother et al. 2022; Hadler et al. 2020). One example would be to bring together the streams of research on generalized trust (generally consistent with the societal view) with a focus on more particularized forms of trust (largely consistent with rational choice assumptions).

4.2. Discussion

The literature on social trust, as demonstrated in preceding sections, contains and reflects a variety of theoretical perspectives. In this article, a number of studies are first distinguished according to their respective recognition of trust as an individual trait and capacity or, alternatively, as a collective property (see Section 3.1 and the Figure 1 with colored threads of influences among authors). Secondly, a multitude of distinctive trust-related dimensions are identified within each of these two distinct bodies of literature. These dimensions are conceptualized to amount to different sub-perspectives (in this case, five in total), with their respective underlying assumptions and arguments.

The perspectives on trust do not merely differ. Sometimes, as shown in the mapping of conceptual influences among authors in Section 3 (Figure 1), they also merge dimensions and compatible arguments. It can be seen (see Table 1) that some dimensions, such as cohesion, cognition, or morality, seem to overlap and define trust across perspectives. It is therefore pertinent to inquire as to what impact a re-examination and re-ordering of these conceptual foundations might have on the trajectory of trust research. My initial response is that the clarity of theoretical concepts imbues empirical endeavors with vitality. As Philippe Van Parijs perceptively notes, “It is sound intellectual policy, however, not to make our concepts too fat. Fat concepts hinder clear thinking and foster wishful thinking“ (Van Parijs 2011, p. 1). Moreover, a process of conceptual review and historical mapping may facilitate a more precise positioning of one’s research and an overview of the flow of arguments. It can assist in the provision of pertinent material and reassessments for discussions concerning the measurement of trust (Van Parijs 2011, pp. 1–3; Uslaner 2015). It is therefore important that we gain an understanding of the manner in which trust is measured and interpreted, in conjunction with the ways in which social actors act, reflect, or reason about trust. Furthermore, conceptual historical sketching also serves to remind us that trust, both as a concept and as a social phenomenon, also has a history. This history influences our current understanding and research on the subject (Hosking 2014).

It is evident that there are numerous ways to examine the implications of trust’s conceptual evolution through its mappings. To the extent that it can be discerned from the different framings of the concept of trust within the five sub-perspectives in Section 3, I will briefly discuss three points: (a) the multiplicity of dimensions may suggest different types of trust; (b) differences in vocabularies may obscure possible similarities in dimensions; and (c) can the multiplicity of identified dimensions be compensated for by the use of dualities.

- (a)

- Can dimensions be ascribed to various types of trust?

As shown in Table 1, trust is characterized by a variety of ascribed attributes or underlying dimensions. These components appear to be inextricably linked and constitute a unified individual or social experience of trust. Or are they? The opposing viewpoint is that trust is not a singular entity but instead comprises a number of distinct forms. The question, therefore, arises as to how these distinctions can be made. The apparent conceptual differences between individual and collective perspectives and their variations, as discussed in Section 3.2, indicate that recognizing the variability of trust is not a zero-sum theoretical issue, an either/or epistemological choice, but may reflect a social multiplicity of the phenomenon. This implies that trust, as a concept attributed to social relations, may have undergone a transformation, or at least evolved into different manifestations. It also signifies that if trust has evolved conceptually from a more dispersed yet perceptive interpretation of Simmel to an empirically examined differentiation between social and political trust, this is arguably due to ongoing transformations in modern societies. This is not merely a theoretical issue.

The concept of social trust can be and is studied at different levels of society in a variety of contexts within a variety of relationships. This does not mean, in my view, that a new subtype of trust should be invented for each context of trust, as some formalization efforts bound by the rationality approach seem to aim. Rather, my claim is that trust can potentially be studied empirically along theoretically plausible dimensions. To examine these dimensions, it is necessary to detect, compare, and discuss their presence and relevance in trust relations. One particularly illustrative example is the debate surrounding the distinction between trust as an instrumental and strategic evaluation of known individuals in transactions and trust as a generalized moral predisposition toward strangers as shown in differences between personality and rational choice approaches in Section 3.2.4 and Section 3.2.5. Moreover, the theoretical mapping in Figure 2 (with additional sub-perspective coloring) shows that cognition and morality, as the distinguishing dimensions of these two perspectives, can be conceptualized as two significant, pervasive, but intertwined aspects of trust. In my view, these two dimensions deserve careful consideration when developing a research design.

- (b)

- The use of different vocabularies may obscure our ability to compare underlying dimensions of trust

The second assumption, based on a brief observation of the historical development of trust, is that the authors appear to approach some underlying dimensions of trust with different vocabularies that are pertinent to their schools of thought. As shown in Table 1, societal approaches, as exemplified by Barber’s view, may discuss trust in terms of moral expectations for social actors. In comparison, more individual and personality-oriented approaches, such as Uslaner’s view, discuss this underlying moral dimension of trust in terms of basic ethical assumptions that individuals share. Alternatively, the same concept may be employed to analyze trust, yet it may evoke disparate meanings in accordance with the epistemological position of the author. The dimension of reciprocity provides an illustrative case in point. It is relevant to both the civic and rational choice perspectives on trust, as seen in Section 3.2.2 and Section 3.2.5. However, the authors in question appear to understand this concept in different ways. On the one hand, reciprocity is regarded as a “civic” trust-related moral principle that underpins cooperation (Putnam 1993, p. 183). On the other hand, it is viewed as a potential “cognitive” substitute mechanism for trust (Axelrod 1984, p. 174).

The dimension of stability is also pertinent to the institutional perspective, as discussed in Section 3.2.3. It may be sustained through the perceived impartiality, institutional framing of social relations, and the reliability of institutions that people trust. Conversely, stability is also pertinent to the concept of trust in terms of the stability of conditions conducive to identity formation, as postulated by personality theories in Section 3.2.4. The different emphases on the same concept can be interpreted from a sociological perspective as a distinction in the focus and understanding of institutions, with one, the institutional perspective, emphasizing the state and the other, the personality theories, emphasizing the family. The relative importance of each institution for trust is, again, an issue that can be highlighted but not fully resolved at the theoretical level.

Furthermore, some of the fundamental characteristics of trust analyzed in the literature appear to cut across many perspectives. One such example, as can be seen in Table 1 when comparing different conceptualizations such as Simmel’s, Gambetta’s, or Sztompka’s, is the temporal aspect of trust, or its orientation toward the future (Simmel [1908] 2013, p. 346; Giddens 1992, p. 33; Putnam 1993, p. 172; Sztompka 1999, p. 18; Uslaner 2002, p. 2; Rothstein 2011, p. 160; Bauer 2015, p. 6). Another example is the concept of trust as it relates to the unknown. This understanding of trust as a belief or mechanism for dealing with uncertainty is sometimes extended from the temporality of trust (Simmel [1908] 2013, pp. 345–47; Gambetta 1988a, p. 346; Misztal 1996, pp. 18–19; Hardin 2002, p. 12; Frederiksen 2014, p. 132). Identifying such shared conceptual foundations and differentiating them from the specific dimensions that appear to fluctuate across perspectives, types, or contexts of trust can represent one of the logical focus points for trust research. This leads us to the next point.

- (c)

- A multiplicity of dimensions or dimensional dualities?

Similarly, as with the methodological debates surrounding binary versus multiple scaling, one could argue that merely listing, structuring, and mapping a number of relevant trust dimensions does not necessarily provide clarity for empirical research, and may even hinder it. In this vein, a heuristic reduction in the multitude of dimensions to binary concepts can be a sensible step to take. Lewis and Weigert, as briefly demonstrated in the discussion of the conceptual thread of the societal perspective (see Section 3.2.1; Lewis and Weigert 1985, pp. 972–73), subsume their concept of trust into two fundamental dimensions, namely rationality and emotionality, while also recognizing boundary states. In line with the suggestions of other authors (Nannestad 2008, p. 414; Misztal 2020, p. 335), a reduction in the five sub-perspectives identified in Section 3.2 with their dimensions may be transformed into a duality comprising two broad categories: rationality- and norm-oriented perspectives. On closer inspection (see Table 1 and Section 3.2.1, Section 3.2.2, Section 3.2.3 and Section 3.2.4), the four perspectives—societal, civic, institutional, and personality—are revealed to incorporate the normative component into trust conceptions in opposition to rational choice approaches. The normative dimension is included in various ways. Personality approaches emphasize the idea of learned moral disposition as a socialized phenomenon. Civic perspectives view the normative component of trust as a set of internalized and shared norms that shape the moral landscape of a community. From a societal perspective, social norms are often associated with the reciprocity of beliefs and commitments that bind individuals within a society. Finally, the institutional perspective incorporates the normative aspect through the state as an entity that embeds moral standards through its impartial institutions and can, therefore, influence social trust among citizens. The challenging aspect of this argument is the conceptual residue of binary framings and the need to reframe the boundaries with the introduction of new, relevant dimensions, such as vulnerability (Misztal 2020).

These exemplary points illustrate some of the conceptual ambiguities that need to be unraveled more systematically in the study of trust. They are part of the process resulting from the identification of some major historical currents, theoretical perspectives, and pervasive arguments about trust with their underlying dimensions, which was the initial goal of this article. The aforementioned points, as dimensions of trust themselves, are not necessarily mutually exclusive; they illustrate and possibly stimulate a better and clearer positioning of research within the ever-expanding maze of literature on trust. By possibly providing a heuristic conceptual beacon and historical sketch for researchers. And, in response to the call for greater clarity, they could potentially facilitate the resolution of some of the existing conceptual stalemates.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript/study, no GenAI tools have been used by the author. The author has reviewed and edited the output and takes full responsibility for the content of this publication. The author has read and agrees to the published version of the manuscript. Open Access Funding by the University of Graz.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Such as identity-based trust (Freitag and Bauer 2013, pp. 26–27), empathy-based altruistic trust (Mansbridge [1999] 2010, p. 291), or knowledge-based trust (Yamagishi and Yamagishi 1994, p. 139). |

| 2 | Uslaner’s criticism relates mainly to the other questions in Rosenberg’s 5-item scale, which measure dimensions such as fairness or helpfulness, and not to generalized trust (see e.g., Uslaner 2002, pp. 18, 69). |

| 3 | The fundamental relational mechanics of Hardin’s concept can be summarized in three key elements. Person A places trust in person B, expecting her/him to do (or relate to) X. This trust relation is expressed in the following manner (Hardin 2006, p. 19): “My trust turns, however not on the trusted’s interest per se, but whether my own interests are encapsulated in the interests of the trusted (…)”. |

| 4 | A third example in this regard is the experimental psychology approach, which has its origins in the work of Morton Deutsch (1958). It examines the factors that can affect the trust between Person I and Person II, including individual expectations, reciprocity, and risk-taking (Deutsch 1958, p. 268). |

| 5 | It should be noted that not all of the authors in Gambetta’s anthology utilize the analytical operational vocabulary of the rational choice tradition in their analysis of trust (Gambetta 1988b). While some, such as Niklas Luhmann, employ a system-sociological perspective in his essay (Luhmann 1988), Keith Hart draws upon anthropological insights to examine trust relationships in African slums (Hart 1988), while Anthony Pagden offers a historical analysis of the erosion of social trust in 18th-century Naples (Pagden 1988). |

| 6 | The range of influences on Giddens’ work is wider and beyond the scope of this essay. His interpretation of Erik Erikson’s personality theory of child development in terms of basic, ontological trust still demonstrates a fruitful disciplinary overlap for trust analysis (Giddens 1984, pp. 51–60). |

| 7 | Giddens posits that attitudes of trust, exemplified by the use of expert systems in modern societies, are typically “routinely incorporated into the continuity of day-to-day activities” (Giddens 1992, p. 90). |

| 8 | Seligman proposes that the discussions of Scottish moral philosophers regarding moral sentiments, characterized as “natural sympathy” or “natural benevolence”, can be interpreted as a discourse on trust. Seligman posits “the language of the eighteenth-century Scottish moralists, of Shaftsbury, Millar, Ferguson, Blair, and even Smith, that same language of civil society so often cited in contemporary debates, is really a language of trust (…) based on an idea of trust posited as one of the conditions of civilized society” (Seligman 1997, p. 31). |

| 9 | Uslaner (2002, p. 39) interprets this as “the most famous statement on how socializing builds trust”. In the context of this study, however, the primary focus is on Tocqueville’s emphasis on reciprocity as a distinctive dimension of trust within the communities. |

| 10 | A more recent example of the assumptions of the civic perspective can be found in the work of Pamela Paxton (2007). Her empirical focus can perhaps be described as the reciprocity between associations and trust. In this context, she introduces the distinction between isolated and connected associations in terms of members who participate in more than one network. Her conclusion is that the connectedness of associations through the multiple membership of their members increases the likelihood of trust (Paxton 2007, p. 62). |

| 11 | Robert Putnam and Lewis Feldstein illustrate the distinction between bonding and bridging social capital with clarity (Putnam and Feldstein 2004, p. 2): “If you get sick, the people who bring you chicken soup likely represent your bonding social capital. On the other hand, a society which has only bonding social capital will look like Belfast or Bosnia—segregated into mutually hostile camps. So a pluralist democracy requires lots of bridging social capital, not just the bonding variety”. |

| 12 | North first defines institutions in general as follows (North 1994, p. 360): “Institutions are the humanly devised constraints that structure human interaction”. |

| 13 | See the contributions by (Rothstein 2009, pp. 5, 14–15; Rothstein and Stolle 2008, p. 441). |

References

- Allport, Gordon W. 1965. Pattern and Growth in Personality, 3rd ed. London: Holt, Rinehart & Winston. First published 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Allport, Gordon. W. 1979. The Nature of Prejudice, 25th Anniversary ed. Reading: Addison-Wesley. First published 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Almond, Gabriel A., and Sidney Verba. 1963. The Civic Culture: Political Attitudes and Democracy in Five Nations. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Arrow, Kenneth J. 1951. Alternative Approaches to the Theory of Choice in Risk-Taking Situations. Econometrica 19: 404–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrow, Kenneth J. 1972. Gifts and Exchanges. Philosophy & Public Affairs 1: 343–62. [Google Scholar]

- Arrow, Kenneth J. 1997. The Limits of Organization. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. First published 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Axelrod, Robert. 1984. The Evolution of Cooperation. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Banfield, Edward C. 1967. The Moral Basis of a Backward Society, Paperback ed. New York: The Free Press. First published 1958. [Google Scholar]