Abstract

The findings of this Systematic Review suggest that Green Social Work (GSW) is gaining momentum as a framework that integrates environmental sustainability with social and relational justice. In the context of climate emergencies and deepening socio-environmental inequalities, GSW proposes a transformative vision for professional practice and highlights the need to rethink the role of social work in addressing ecological challenges. This article presents a systematic review of academic literature aimed at analyzing the conceptual development, areas of application, and methodological characteristics of GSW. Fifteen peer-reviewed articles were selected through a structured search in five international databases, applying inclusion criteria that required explicit reference to the GSW framework. The review examines how GSW has been implemented in practice, education, community intervention, and policy design. The findings point to emerging patterns in the application of GSW across contexts of environmental vulnerability, such as disaster recovery, rural development, and climate justice, as well as its incorporation into professional training and ethical codes. However, the review also reveals the absence of shared operational definitions and the predominance of qualitative, exploratory studies with limited generalizability. Overall, GSW offers a valuable pathway for strengthening the contribution of social work to ecological and social challenges. Its integration into education, research, and policy can enhance professional responses to complex crises, although clearer operational frameworks and more robust empirical studies are needed to consolidate GSW as a key tool for socio-environmental transformation.

1. Introduction

Deforestation, droughts, and floods are among the main consequences that the environmental crisis is causing in ecosystems. This environmental impact disproportionately affects people in situations of heightened vulnerability. Social vulnerability is defined as the predisposition of an individual or group to suffer harm from external threats, including a lack of adaptive capacity (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) 2014). Issues such as climate change, pollution, biodiversity loss, and the exploitation of natural resources have generated new forms of socio-environmental inequality and vulnerability for disadvantaged populations (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) 2023). These impacts go beyond the physical phenomena of climate change but also manifest within the social, economic, and historical structures that shape people’s capacity to cope with risks.

Consistent with this perspective, environmental sociology has long demonstrated that environmental degradation, vulnerability, and risk emerge from social structures, political economy, and unequal distributions of power rather than from purely biophysical dynamics. Classic work in the field challenged human-exemptionalist assumptions and argued for a sociological perspective that recognizes the dependence of social systems on ecological limits and the feedback effects of environmental change on social inequality (Dunlap and Catton 1979). Subsequent contributions emphasized that environmental problems are embedded within broader patterns of production, consumption, governance, and stratification—central dimensions of the political-economy tradition in environmental sociology (Buttel 1987). These insights align closely with Green Social Work, which interprets socio-environmental crises as expressions of structural inequality and positions social work practice at the intersection of community well-being, ecological sustainability, and environmental justice.

From a social perspective, the main adverse effects include rising inequality and poverty, forced migration, deterioration of public health, conflict and social tension, as well as the loss of cultural identity (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) 2023). The IPCC thus warns that climate change is not only an environmental problem but also deepens social divides and disproportionately affects those with fewer resources. In fact, traditionally marginalized groups such as older adults, children, and persons with disabilities tend to be more severely impacted by climate-related events due to structural inequalities (Birkmann et al. 2022). In addition to these groups, research in environmental justice consistently shows that Indigenous peoples, ethnic minorities, migrants, and racialized communities face disproportionately higher exposure to environmental hazards and are structurally constrained in their capacity to adapt to climate-related risks (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) 2023). These populations experience multiple and overlapping forms of disadvantage, including historical dispossession, spatial segregation, and political underrepresentation, that amplify their vulnerability to environmental crises. Recognizing this broader set of marginalized groups is essential for understanding the socio-environmental inequalities that GSW aims to address.

In rural contexts, the impacts on agricultural livelihoods can be especially severe. A study in Bangladesh found that farming families in flood-prone areas experienced significant income losses due to declines in rice yields (Alamgir et al. 2021). In many regions, climate variability—such as droughts, irregular rainfall, or floods—not only reduces agricultural production but also drives up food prices, affecting the well-being of entire communities (Otto et al. 2017). Measurement systems such as the World Risk Index and the INFORM Index also indicate that mortality linked to floods, droughts, and storms is significantly higher in the most vulnerable countries (Birkmann et al. 2022).

The link between armed conflict and climate change has also been examined through the “vicious cycle” connecting vulnerability, conflict, and climate change. According to Buhaug and von Uexkull (2021), many of the conditions that generate climate vulnerability also increase the risk of armed conflict. In turn, conflict worsens these conditions by destroying infrastructure, forcing displacement, and leading to forced migration, thereby reinforcing a difficult-to-break cycle.

Beyond material and social implications, climate change also affects the cultures of specific populations. The loss of ancestral lands, forced displacement, or the destruction of spiritually significant natural landscapes can generate distress, loss of identity, and emotional suffering (Otto et al. 2017).

Social work has historically engaged with people in vulnerable situations and disadvantaged groups (such as children, older adults, and persons with disabilities). However, the environmental dimension has received limited attention. Richmond (1922), a pioneer in direct intervention with individuals in social work, already acknowledged the importance of understanding the immediate environment (home, school, community, etc.) as key to understanding people’s social circumstances. According to Pardeck (1988), this approach considers that individual problems cannot be understood or addressed in isolation from their physical and social environment. While this initially focused on social factors such as poverty, this perspective laid the groundwork for incorporating the natural and physical environment as key dimensions of human well-being. Along these lines, Jarvis (2013) suggests that, to maintain its relevance and commitment to social justice, social work must integrate the environmental dimension into Richmond’s framework and update it in response to the challenges posed by climate change. In a similar vein, some authors such as Matthies et al. (2001) argue that social work should broaden its scope to include ecological perspectives, emphasizing the interconnections between human well-being, social systems, and the natural environment.

In this regard, the systems model has been fundamental in the development of social work, emphasizing the importance of the environment in the lives of individuals, groups, and communities (Viscarret Garro 2007). Based on Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) ecological theory, it holds that interactions between individuals and their environment are essential to understanding well-being. This approach promotes a holistic understanding of social issues, in which environmental degradation can be seen as a factor that exacerbates pre-existing inequalities and vulnerabilities in society (Dominelli 2018). However, this model has not adequately accounted for the impacts of climate change or environmental degradation on human well-being.

Over time, several concepts have emerged that integrate environmental concerns into social work practice, such as ecological social work, ecofeminist social work, ecospiritual social work, environmental social work, sustainable social work, and green social work (Ramsay and Boddy 2017). These approaches differ in their emphasis on specific aspects, such as the recognition of Indigenous and spiritual knowledge, criticism of anthropocentrism and advocacy for an ecocentric perspective, or the transformation of economic and political systems.

Although the literature offers multiple terms linking social work with environmental issues, this review focuses on Green Social Work (GSW), as it represents one of the most comprehensive approaches within contemporary social work frameworks in relation to the ecological crisis. This approach not only coherently integrates the principles of social and environmental justice but also provides a practical intervention model applicable in diverse contexts such as climate emergency management, community work, or policy advocacy. It also includes established best practices, professional action guidelines, and concrete tools that enable social workers to respond proactively to the challenges of climate change and environmental degradation, while maintaining a focus on human rights and social equity (Dominelli 2012).

Dominelli (2012) developed the GSW model with the aim of reformulating social work practice to address the ecological and social crisis in an integrated manner. This model is based on the premise that environmental degradation affects both ecosystems and community well-being, social justice, and human rights; proposing a necessarily transdisciplinary action framework that incorporates various disciplines at both the practical and theoretical levels. It must also be evidence-based and grounded in a participatory process between practice and research. Furthermore, it should aim to foster social change that enables transformation of the socioeconomic system and the co-production of plans that enhance community resilience in the face of natural disasters and other crises.

Following this theoretical model, Dominelli (2018) outlines a series of steps to implement GSW. The practical model begins with a risk assessment, identifying and analyzing the factors that threaten the well-being of individuals, groups, or communities. Once the risks are identified, a mitigation planning phase follows, in which strategies are designed to reduce or eliminate risks. This is followed by an action plan with preventive measures and strategies to strengthen individual and community resilience. Subsequently, the action plan is implemented, and responses to unforeseen impacts are carried out, along with an evaluation of the plan to allow for necessary adjustments. This model emphasizes the importance of comprehensive, transdisciplinary planning, responding to the changing needs of communities, promoting active participation, and developing resilient strategies.

GSW represents an opportunity for professionals to respond actively to the environmental crisis and its consequences for the well-being of individuals, groups, and communities. However, for this approach to be more than a theoretical framework for practice development, it is essential to examine and analyze what is currently being done in social work, both in direct intervention with vulnerable communities, in the production of knowledge and research, and in the training of future professionals. At a time when the effects of the environmental crisis are increasingly evident, it is crucial to review what is being implemented in social work and propose improvements to professional practice from the perspective of GSW. This systematic review aims to provide an overview of the current state of GSW, analyzing experiences, methodologies, intervention frameworks, and emerging lines of research. Specifically, the objectives of this research are: to assess the actual presence of GSW within the field of social work; to examine whether a clear operational definition of GSW exists; to identify the contexts in which GSW is implemented, in particular those of particular vulnerability; to analyze the extent to which GSW is included in social work education and training; to review the empirical development achieved so far regarding GSW; and to identify the limitations of current research and practice in GSW.

2. Materials and Methods

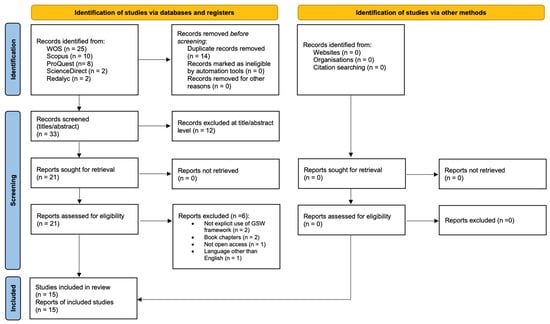

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Page et al. 2021). The completed PRISMA checklist is available in the Supplementary Materials, and the study selection process is illustrated in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1). The review was not prospectively registered in PROSPERO or any other database, and no formal protocol was prepared prior to conducting the review. To mitigate potential risks associated with the absence of preregistration, such as post hoc adjustments to inclusion criteria, the review employed predefined eligibility criteria, independent screening by four reviewers, third-party adjudication, and full transparency regarding excluded studies (Supplementary Table S1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) peer-reviewed empirical studies that explicitly referred to the “Green Social Work” (GSW) framework; (2) published in English; (3) available in full-text open access; and (4) with no restriction on publication date. Restricting the sample to English and open-access publications ensured transparency and replicability but may have reduced epistemic and geographical diversity; this is acknowledged as a limitation and future reviews should broaden linguistic and access criteria.

The exclusion criteria were: (1) review articles or book chapters; (2) documents without full-text access; (3) publications in languages other than English; and (4) studies addressing social work and the environment that did not explicitly employ the GSW framework.

2.2. Search Strategy and Information Sources

An exhaustive search was conducted across five international databases: Web of Science (WOS), Scopus, ScienceDirect, ProQuest, and Redalyc, between 18 October and 25 October 2024. Additionally, manual searches were carried out in the reference lists of the included studies and in specialized journals (e.g., International Social Work, British Journal of Social Work). The last search update was performed on 25 October 2024.

The main search string was: “green social work” OR (“green” AND “social work”).

This string was adapted to the syntax of each database without altering the main keywords. Filters applied included language (English) and document type (article). Table 1 presents the search strings used for each database.

Table 1.

Search terms/combination.

2.3. Study Selection Process

The initial search yielded 47 records: WOS (n = 25), Scopus (n = 10), ProQuest (n = 8), ScienceDirect (n = 2), and Redalyc (n = 2). After removing 14 duplicates, 33 titles and abstracts were screened.

Screening was performed independently by four reviewers. An agreement level of ≥75% (3 out of 4 reviewers) was required; in case of a tie, a fifth reviewer made the final decision. Abstract screening led to the exclusion of three records. Of the remaining 30, 12 were excluded for not meeting the inclusion criteria (e.g., lack of explicit reference to GSW, book chapter, or non-open-access publication). A detailed list of excluded studies and the reason for exclusion is provided in Supplementary Table S1. The final sample consisted of 15 articles.

The overall selection process is summarized in Figure 1 (PRISMA flow diagram).

2.4. Data Extraction and Coding

Data were extracted independently by two reviewers using a standardized extraction form. The information extracted included: Author, Year, Country, Journal, Topics Addressed, Emphasis, Key Authors, Definitions, Fields of Application, Variables Associated with GSW, Objectives, Participants, Instruments, Type of Analysis, Results, and Limitations. In case of discrepancies, a third reviewer verified and resolved the differences by consensus.

The following primary outcomes were collected: definitions of GSW, fields of application (education, community intervention, post-disaster recovery, policy), methodological approaches, reported impacts, participants, instruments, analytical methods, and limitations. Secondary outcomes included: country of study, year of publication, and journal type. When specific information was unclear (e.g., missing funding statement), it was coded as “not applicable” (NA).

2.5. Quality Appraisal and Risk of Bias Assessment

Given that the included studies featured both qualitative and quantitative designs, two methodological appraisal tools developed by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) were applied, selected according to the nature of each study.

For qualitative studies, the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Qualitative Research (Lockwood et al. 2015) was used. This tool assesses the congruence between the philosophical perspective, methodological design, and data analysis and interpretation procedures. It includes ten items that evaluate aspects such as methodological coherence, adequacy in representing participants’ voices, researcher reflexivity, and evidence of ethical approval.

For quantitative studies, specifically analytical cross-sectional designs, the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Analytical Cross-Sectional Studies (Moola et al. 2020) was employed. This checklist comprises eight items focusing on internal and external validity, clarity of inclusion criteria, description of context and sample, identification of confounding factors, and adequacy of statistical analyses.

The results of the appraisal are presented in Table 2 and Table 3. Table 2 corresponds to the qualitative studies assessed using the instrument by Lockwood et al. (2015), whereas Table 3 refers to the quantitative studies evaluated using the checklist by Moola et al. (2020). Both tables indicate the percentage of agreement obtained for each item and study.

Table 2.

JBI quality assessment of qualitative studies.

Table 3.

JBI quality assessment of quantitative studies.

The average inter-rater agreement in the risk of bias assessment was above 70% in all cases, suggesting adequate reliability in the coding and methodological quality appraisal of the included studies.

2.6. Synthesis of Results

All reported findings were extracted and thematically categorized according to the areas of application and study objectives (see Section 2.4).

Given the heterogeneity of contexts, participants, and research designs, a narrative synthesis was conducted, complemented by descriptive tables that organize the findings based on study characteristics, key results, and identified limitations. Finally, when quantitative data were available, descriptive statistics and effect size estimates reported by the authors were included.

3. Results

The documentary review identified a set of fifteen articles that address GSW from different geographical, thematic and methodological perspectives (Table 4). The selected studies come from well-established academic journals in the field of social work, such as International Social Work, British Journal of Social Work, Journal of Social Work, Social Sciences, Critical & Radical Social Work, among others. This diversity of sources reflects the growing interest in integrating environmental justice and sustainability into academic and professional social work agendas.

Table 4.

Description of selected articles for the GSW review.

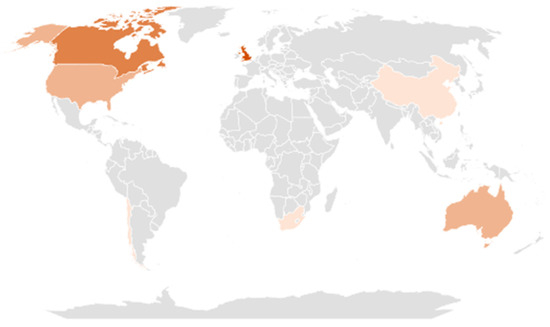

As shown in Table 4, in geographical terms, the articles cover a wide range of contexts, with contributions from the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, Australia, China, Chile, South Africa, and Zimbabwe (Figure 2). This allows us to observe how GSW is adapted and developed in settings with diverse socio-environmental realities. Regarding the topics addressed, the studies highlight issues such as food insecurity, post-disaster reconstruction, spatial justice, rural–urban migration, GSW professionalization, the gendered impact of climate change, the relationship between speciesism and social justice, and resilience in the face of pandemics. These topics reveal the multidimensional and cross-cutting nature of GSW, integrating social, environmental, political, and educational aspects. Taken together, these findings illustrate preliminary patterns suggesting that GSW is being applied mainly in contexts marked by socio-environmental vulnerability, such as disaster recovery, rural communities affected by climate change, and precarious socio-economic settings, although the evidence base remains fragmented and exploratory.

Figure 2.

Geographical distribution of studies by country; darker shades represent a higher number of studies.

Regarding the fields of application (Table 5), some articles focus on the development of professional and educational competencies, aiming to incorporate sustainability and environmental justice into the training of future social workers. Others adopt a more intervention-oriented perspective, analyzing the role of social work in community reconstruction after disasters, the creation of environmental ethical codes or the promotion of community participation in contexts of high environmental vulnerability. Additionally, some studies are centered on public policy and intervention models that integrate GSW into territorial planning, environmental justice and agricultural sustainability, particularly in rural communities or populations vulnerable to climate change.

Table 5.

Synthesis of approaches, applications and variables associated with GSW in the reviewed literature.

After describing the selected articles, relevant information was extracted to outline an operational definition of GSW, identify its main fields of application and systematize the conceptual variables associated with the reviewed literature, including new theoretical proposals and expansions of the traditional framework (Table 5). The results show that, although there is no single, consensual definition of GSW, the publications generally characterize it as a comprehensive, transdisciplinary, and integrative approach that articulates social justice, human rights and environmental sustainability within professional social work practice—occasionally incorporating post-anthropocentric and intersectional perspectives. This broad characterization coexists with the absence of a single, precise operational definition, reflecting both the richness and the challenges of the field. Such polysemy may be seen as a strength, enabling adaptability across diverse socio-cultural and territorial contexts, but also as a limitation when it comes to building common standards for training, evaluation, or the institutionalization of GSW.

Regarding the fields of application, the studies emphasize the role of GSW in contexts of natural disasters, climate change, post-disaster community reconstruction processes, and environmental crises associated with poverty and socioeconomic precariousness. An emerging area identified relates to the training and professionalization of social workers, with proposals aimed at incorporating environmental sustainability and climate justice into the discipline’s educational programs. There is also growing interest in spatial justice and the strengthening of community resilience, particularly in rural areas and territories affected by extractive industries or intensive industrialization. Furthermore, some studies highlight applications of GSW in ethical disaster planning, including the consideration of non-human species.

The variables that define GSW in the analyzed literature include, recurrently, the interdependence between human and ecosystem well-being, community participation, equity in access to environmental resources, transdisciplinary approaches to intervention, resilience in the face of socio-environmental crises, critique of the dominant social paradigm, post-anthropocentric perspectives, and the agency of non-human beings. The incorporation of a gender perspective is also noteworthy, particularly in rural communities and in those where climate change directly affects food security and local livelihoods. In addition, the findings allow a distinction between attributes that appear consistently across studies (core attributes) and those that are context dependent (peripheral attributes). Core attributes could include: (1) the integration of social and environmental justice; (2) human–ecosystem interdependence; and (3) community participation. Peripheral attributes include post-anthropocentric perspectives, intersectional ecofeminist frameworks, and links to global sustainability agendas. Identifying these core and peripheral elements clarifies what distinguishes GSW from closely related frameworks, such as Environmental Social Work, and reduces ambiguity regarding its operational boundaries.

Overall, the findings reflect the consolidation of an emerging paradigm of intervention that goes beyond traditional social work by integrating the ecological dimension as a central and inseparable component of social practice. This approach promotes a model of development that combines social and environmental justice, with particular attention to populations in situations of socio-environmental vulnerability and to environmentally degraded territories, underscoring the need to strengthen the role of social work in socio-environmental management and climate action.

The reviewed studies (Table 6) demonstrate the methodological and thematic diversity with which Green Social Work (GSW) has been addressed. Although qualitative approaches predominate, particularly the use of case studies, interviews, and document analysis, there is also a quantitative study that examines environmental attitudes among social work professionals using a validated scale. This trend highlights the importance of understanding the experiences and narratives of communities affected by environmental issues, by deeply analyzing subjective experiences and community processes. However, it also limits the possibility of generalizing findings or assessing the long-term impacts of GSW, pointing to a significant research gap. Moreover, many of the variables discussed in these studies are presented predominantly in conceptual or normative terms rather than as operational constructs, which limits comparability across studies and underscores the early stage of theoretical consolidation in the field. Alongside empirical studies, there are also conceptual contributions that expand GSW’s theoretical framework through intersectional, ecological, and post-anthropocentric perspectives. The findings show that implementing GSW in diverse contexts has had a significant impact in areas such as professional training, post-disaster reconstruction, and community activism. Studies focus on both educational contexts and direct community intervention, evidencing the versatility of this approach. Additionally, the intersectionality of the issues addressed through GSW is emphasized. The reviewed literature indicates that GSW functions as a key tool to mitigate structural inequalities and strengthen community participation in environmental governance. Overall, the findings reflect a growing recognition of social work’s role within the socio-environmental agenda. The need to integrate ecological knowledge and adaptation strategies into public policies and professional training is emphasized, aiming to promote more sustainable and equitable responses to environmental challenges. Innovative proposals, such as including non-human animals as ethical and political subjects, further expand GSW’s scope toward post-anthropocentric frameworks.

Table 6.

Type of study and results.

The limitations identified in the reviewed studies point to both methodological and structural challenges in the implementation of Green Social Work (GSW) (see Table 7). These include a lack of financial and time resources, reliance on community cooperation, and limited scalability. Another significant challenge is the restricted generalizability of the results. Additionally, the findings highlight the absence of empirical studies that assess the effectiveness of GSW.

Table 7.

Limitations identified by the authors in the examined articles.

4. Discussion

The findings of this review suggest that Green Social Work (GSW) is beginning to consolidate as a relevant approach within social work, particularly due to its capacity to integrate two key concepts, environmental justice and sustainability, within vulnerable contexts. However, although most articles agree in characterizing GSW as a transdisciplinary and socially just approach, a shared operational definition is still lacking. This absence limits the ability to compare studies and systematize practices across contexts. Establishing minimum areas of consensus would support greater conceptual coherence without dismissing the pluralism and diversity that characterize the field. For the purposes of this review, GSW is understood as a professional, community-based, and policy-oriented approach that integrates social and environmental justice to address the structural drivers of socio-ecological vulnerability. This operational definition emphasizes three key elements: (1) the inseparability of ecological and social well-being; (2) the need for interventions that combine direct practice with structural and institutional action; and (3) the use of transdisciplinary methods to strengthen community resilience. Making this definition explicit provides conceptual coherence across the included studies and responds directly to the lack of a consensual definition identified in the literature.

In terms of practical application, GSW is primarily implemented in highly vulnerable contexts: rural communities, areas affected by climate change, or natural disasters. In these settings, GSW functions as a tool for community resilience, local empowerment, and structural transformation. Furthermore, some studies expand its theoretical framework by incorporating ecofeminist, interspecies, or post-anthropocentric approaches, such as Fraser et al. (2021), suggesting a conceptual evolution toward more inclusive and critical models. This evolution connects with frameworks like Environmental Social Work (ESW), also referenced in the literature to explore the relationship between social work and the environment. ESW has been widely addressed in the literature as a framework that seeks to link social work with environmental issues, incorporating ecological, educational, and preventive perspectives (Gray et al. 2013). This approach emphasizes the need for the profession to recognize the interdependence between people and their natural environment, promoting environmental awareness and sustainable practices within professional practice. However, GSW represents a more critical perspective, committed to social change through the transformation of the social, economic, and political structures that generate socio-environmental inequalities (Dominelli 2012).

In conceptual terms, GSW can be situated within core debates in environmental sociology that challenge the assumption that human societies are exempt from ecological limits and divorced from biophysical processes. Classic contributions in this field have highlighted the need to move from a human-exemptionalist view of social life toward a “new ecological paradigm” that recognizes the dependence of social systems on ecosystems and the unintended consequences of overexploiting them (Dunlap and Catton 1979). From this perspective, environmental problems are not merely technical or natural phenomena but are deeply embedded in social structures, power relations, and patterns of production and consumption (Hannigan 2006; Pellow and Nyseth Brehm 2013). GSW translates these insights into the domain of social work by framing ecological crises as expressions of social stratification and by linking environmental harms to unequal distributions of risk, protection, and political voice.

Environmental sociology has also shown that environmental burdens and benefits are unevenly distributed along lines of class, race, ethnicity, and place, giving rise to an environmental justice agenda that treats ecological degradation as a form of social inequality rather than a purely environmental issue (Hannigan 2006; Pellow and Nyseth Brehm 2013). Within this framework, professional fields and institutions play a key role in either reproducing or challenging these inequalities. GSW can therefore be understood as a professional and institutional response to socio-ecological crises: it positions social work as an actor that not only supports communities in contexts of climate vulnerability and disaster, but also contests the policies and development models that systematically expose marginalized populations to higher levels of environmental risk. This alignment with environmental sociology reinforces the analytical capacity of GSW to connect everyday practice with broader structures of power, inequality, and ecological transformation.

This theoretical development has also influenced social work education and training. The reviewed studies consistently highlight the importance of integrating environmental dimensions into curricula and student training (Androff et al. 2017; Breen et al. 2023; Wu and Greig 2022). Moreover, they emphasize the need to equip professionals with tools to act in scenarios involving climate crises and disasters. However, this educational approach has been primarily developed through specific case studies, often based on limited samples or restricted to particular geographical contexts, which hampers the generalizability of findings (Dominelli 2014; Shaw 2011; Downey et al. 2023).

With regard to professional practice, studies focusing on direct intervention (Ku and Dominelli 2018; Dominelli and Ku 2017) emphasize the value of GSW in community reconstruction following a disaster. However, institutional support is needed to sustain these initiatives beyond the local level. Similarly, GSW’s presence in public policy remains weak, limiting its reach and continuity. This weak institutional positioning is closely linked to the lack of professionals and educators with specialized training in GSW (Dominelli and Ku 2017), which hinders its integration into academic programs, public agendas, and regulatory frameworks. Therefore, it is crucial to promote recognition of GSW as a cross-cutting approach in education, research, and practice. Professional social work operates as a key institutional actor in responding to socio-environmental challenges, yet its potential remains underdeveloped in most national systems. Institutional arrangements, such as fragmented governance, limited environmental mandates, and insufficient intersectoral coordination, constrain the ability of social workers to address ecological risks at the structural level. GSW highlights that effective responses require integrating social work into disaster governance, climate adaptation strategies, territorial planning, and community resilience programs. Strengthening institutional support and expanding the profession’s environmental competences would enable social work to function not only as a front-line responder but also as an agent capable of shaping socio-environmental outcomes through policy influence and systemic intervention.

Variables commonly associated with GSW in the reviewed literature include human–ecosystem interdependence, equitable access to resources, community participation, sustainability, spatial justice, and, in some cases, non-human agency. This range of variables suggests not only a broadening of the theoretical framework but also an intent to redefine the epistemological and ethical foundations of contemporary social work. However, many of these variables are presented conceptually or normatively, without clear empirical development. This presents a challenge for practical application and research, highlighting the need to operationalize these variables methodologically and generate evidence of their effectiveness in specific contexts. Additionally, the review identified several thematic gaps. Topics such as circular economy, sustainable urban planning, policy advocacy in environmental regulation, or the relationship between social work and green technologies are underrepresented. This lack suggests an opportunity to expand the GSW field into emerging areas that are crucial for ecological transition and intergenerational justice.

These methodological shortcomings are also reflected in the limitations acknowledged by the authors themselves. Specifically, there is a notable reliance on exploratory designs, case studies, and documentary approaches, which limits the generalizability of findings and the establishment of robust comparative frameworks. Empirical studies often report small sample sizes, limited participant diversity, and, in some cases, a lack of validated instruments. This pattern occurs both locally and internationally, making it difficult to systematically assess the effectiveness of GSW in practice. Similarly, the literature reveals a scarce use of longitudinal designs and an overreliance on qualitative studies with small samples. This impedes impact evaluation and underscores the need to strengthen research methodologies by incorporating quantitative and/or mixed-method approaches and conducting medium- to long-term assessments.

Furthermore, a disconnect is observed between the theoretical principles of the GSW model and its practical implementation. Although Dominelli (2018) proposes a well-defined sequence of steps (risk assessment, planning, action, and implementation), few studies adopt this framework comprehensively. Only the works of Ku and Dominelli (2018) and Dominelli and Ku (2017) demonstrate a structured application of the model, highlighting a gap between theory and practice. This points to the need for tools that facilitate systematic application, as well as mechanisms to assess effectiveness. Additionally, one of the core principles of GSW, evidence-based development and community participation (Dominelli 2012), is rarely met in the reviewed studies. While some employ participatory methodologies such as action research, there are no systematic mechanisms to integrate community experience with scientific knowledge, which limits the validity and practical relevance of findings.

The review shows that social work, traditionally focused on social and economic aspects, has paid little attention to climate change and the links between environmental degradation and inequality. GSW seeks to address this gap by broadening its scope to include ecological issues and new forms of vulnerability. This represents a significant theoretical shift, albeit with limited development to date. In this regard, Dominelli and Ku (2017) suggest that GSW has not yet managed to influence or become integrated into public policy, partly due to the lack of trained professionals, researchers, and educators in this field. This shortage limits the profession’s ability to effectively address challenges such as climate change, deforestation, health deterioration, well-being, or displacement caused by environmental crises.

To achieve real impact, it is essential that universities, governments, and non-governmental organizations recognize GSW as a key cross-cutting tool in both training and professional practice. One possible strategy is to include theoretical content on environmental justice, sustainability, and ecological ethics in university curricula for social work, while also analyzing how to intervene in different problem scenarios from a GSW perspective (e.g., solving case studies on defending farmers’ rights, disaster response, etc.). Likewise, incorporating practitioners’ experience into public policy design, especially in post-disaster recovery plans, can strengthen social responses to environmental emergencies.

This review has some limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the use of specific search criteria may have excluded relevant studies published in other languages or adopting related approaches. Second, among the analyzed articles, there is a predominance of qualitative designs and case studies, which provide interpretive depth but limit generalizability. Moreover, several studies are based on small, self-selected samples or focused on specific contexts, making it difficult to extrapolate findings. Finally, there is limited inclusion of longitudinal evaluations, and few studies systematically apply the GSW model, highlighting the need for further theoretical, methodological, and applied development.

5. Conclusions

In summary, this review meets the proposed research objectives by identifying both the potential and the current limitations of GSW. The findings confirm its presence across various domains of social work, although unevenly distributed, and show that its implementation is concentrated in highly vulnerable contexts, particularly disaster recovery, rural communities, and socio-environmentally precarious settings. A central limitation is the absence of a shared operational definition, which constrains the systematization of practices, hampers cross-study comparability, and reflects the early stage of theoretical consolidation in the field. The working definition proposed in this review contributes a clearer analytical foundation, while acknowledging the need for further empirical validation. The empirical development of GSW remains restricted and dominated by qualitative, exploratory, and small-scale studies, meaning that current conclusions should be interpreted as emerging trends rather than definitive evidence. Methodological shortcomings, including the lack of preregistered or standardized protocols, limited longitudinal evaluations, heterogeneous conceptualizations, and the absence of shared metrics, further limit the possibility of cumulative knowledge. Moreover, its integration into education and professional training continues to be incipient and fragmented, relying on isolated initiatives rather than consolidated frameworks. Overall, these findings point to both significant advances and persistent challenges, underscore the need to strengthen GSW not only as a conceptual framework but also as a practical tool for training, intervention, and social transformation. In doing so, GSW not only addresses the environmental crisis but also renews social work’s commitment to human rights, justice, equity, and sustainability, reinforcing its relevance in an increasingly interdependent and crisis-prone world.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/socsci14120720/s1, Supplementary Table S1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.L., B.H., and C.R.; methodology, M.L., M.L.R.-R., C.C., B.H., and C.R.; validation, M.L., M.L.R.-R., C.C., B.H., and C.R.; investigation, M.L., M.L.R.-R., C.C., and C.R.; data curation, M.L., M.L.R.-R., C.C., and C.R.; writing—original draft preparation, M.L., M.L.R.-R., C.C., and C.R.; writing—review and editing, B.H.; visualization, M.L., M.L.R.-R., and C.R.; project ad-ministration, M.L., and C.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Alamgir, Md. Shamsul, Jun Furuya, Satoshi Kobayashi, Most Sayma Rahman Binte, and Md. Rabiul Ahmed. 2021. Farm Income, Inequality, and Poverty among Farm Families of a Flood-Prone Area in Bangladesh: Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment. GeoJournal 86: 2861–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Androff, David, Cheryl Fike, and Jessica Rorke. 2017. Greening Social Work Education: Teaching Environmental Rights and Sustainability in Community Practice. Journal of Social Work Education 53: 399–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkmann, Jörn, Adeel Jamshed, Jillian M. McMillan, Daniel Feldmeyer, Yusuke Totoki, and William Solecki. 2022. Understanding Human Vulnerability to Climate Change: A Global Perspective on Index Validation for Adaptation Planning. Science of the Total Environment 803: 150065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowles, Wendy, Heather Boetto, Peter Jones, and Jennifer McKinnon. 2016. Is Social Work Really Greening? Exploring the Place of Sustainability and Environment in Social Work Codes of Ethics. International Social Work 61: 503–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breen, Karen, Michelle Greig, and Hsiu-Fang Wu. 2023. Learning Green Social Work in Global Disaster Contexts: A Case Study Approach. Social Sciences 12: 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, Urie. 1979. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Buhaug, Halvard, and Nina von Uexkull. 2021. Vicious Circles: Violence, Vulnerability, and Climate Change. Annual Review of Environment and Resources 46: 545–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buttel, Frederick H. 1987. New Directions in Environmental Sociology. Annual Review of Sociology 13: 465–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañeda-Meneses, Pablo. 2024. Trabajo Social Ambiental en Chile: Avanzando hacia un Green Social Work. Prospectiva. Revista de Trabajo Social e Intervención Social 38: e21213501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominelli, Lena. 2012. Green Social Work: From Environmental Crises to Environmental Justice. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dominelli, Lena. 2013. Environmental Justice at the Heart of Social Work Practice: Greening the Profession. International Journal of Social Welfare 22: 431–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominelli, Lena. 2014. Promoting Environmental Justice through Green Social Work Practice: A Key Challenge for Practitioners and Educators. International Social Work 57: 338–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominelli, Lena. 2018. The Routledge Handbook of Green Social Work. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Dominelli, Lena. 2020. A Green Social Work Perspective on Social Work during the Time of COVID-19. International Journal of Social Welfare 29: 346–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dominelli, Lena, and Hung-Bin Ku. 2017. Green Social Work and Its Implications for Social Development in China. China Journal of Social Work 10: 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downey, Helen, Elisha Spelten, Kate Holmes, Sarah MacDermott, and Patrick Atkins. 2023. A Green Social Work Study of Environmental and Social Justice in an Australian River Community. Social Work Research 47: 207–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, Riley E., and William R. Catton, Jr. 1979. Environmental Sociology. Annual Review of Sociology 5: 243–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, Heather, Nicole Taylor, and Damien W. Riggs. 2021. Animals in Disaster Social Work: An Intersectional Green Perspective Inclusive of Species. The British Journal of Social Work 51: 1739–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, Mel, John Coates, and Tiani Hetherington. 2013. Environmental Social Work. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hannigan, John. 2006. Environmental Sociology, 2nd ed. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). 2014. Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). 2023. AR6 Synthesis Report: Climate Change 2023. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/syr/ (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Jarvis, Darryl. 2013. Environmental Justice and Social Work: A Call to Expand the Social Work Profession to Include Environmental Justice. Columbia Social Work Review 11: 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, Hung-Bin, and Lena Dominelli. 2018. Not Only Eating Together: Space and Green Social Work Intervention in a Hazard-Affected Area in Ya’an, Sichuan of China. The British Journal of Social Work 48: 1409–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockwood, Craig, Zachary Munn, and Kylie Porritt. 2015. Qualitative Research Synthesis: Methodological Guidance for Systematic Reviewers Utilizing Meta-Aggregation. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare 13: 179–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marlow, Christine, and Chris van Rooyen. 2001. How Green Is the Environment in Social Work? International Social Work 44: 241–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthies, A.-L., Kati Närhi, and David Ward, eds. 2001. The Eco-Social Approach in Social Work. SoPhi Publication No. 58. Jyväskylä: SoPhi, University of Jyväskylä. ISBN 951-39-0914-X. [Google Scholar]

- Moola, Sandeep, Zachary Munn, Catalin Tufanaru, Edoardo C. Aromataris, Kerry Sears, Raluca Sfetcu, Michelle Currie, Rizwan Qureshi, Paul Mattis, Kylie Lisy, and et al. 2020. Chapter 7: Systematic Reviews of Etiology and Risk. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. Edited by E. Aromataris and Z. Munn. Adelaide: Joanna Briggs Institute. Available online: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Muchacha, Munyaradzi, and Mudavanhu Mushunje. 2019. The Gender Dynamics of Climate Change on Rural Women’s Agro-Based Livelihoods and Food Security in Rural Zimbabwe: Implications for Green Social Work. Critical and Radical Social Work 7: 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, Ilona M., Diana Reckien, Christian P. O. Reyer, Rachel Marcus, Virginie Le Masson, Lindsey Jones, Andrew Norton, and Olivia Serdeczny. 2017. Social Vulnerability to Climate Change: A Review of Concepts and Evidence. Regional Environmental Change 17: 1651–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, Matthew J., Joanne E. McKenzie, Patrick M. Bossuyt, Isabelle Boutron, Tammy C. Hoffmann, Cynthia D. Mulrow, Larissa Shamseer, Jennifer M Tetzlaff, Elie A Akl, Sue E Brennan, and et al. 2021. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 372: n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardeck, John T. 1988. An Ecological Approach for Social Work Practice. The Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare 15: 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellow, David N., and Hollie Nyseth Brehm. 2013. An Environmental Sociology for the Twenty-First Century. Annual Review of Sociology 39: 229–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsay, Stewart, and Jennifer Boddy. 2017. Environmental Social Work: A Concept Analysis. The British Journal of Social Work 47: 68–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richmond, Mary. 1922. Social Diagnosis. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, Todd V. 2011. Is Social Work a Green Profession? An Examination of Environmental Beliefs. Journal of Social Work 13: 3–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viscarret Garro, Juan Jesús. 2007. Modelos y Métodos de Intervención en Trabajo Social. Madrid: Alianza Editorial. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Hsiu-Fang, and Michelle Greig. 2022. Adaptability, Interdisciplinarity, Engageability: Critical Reflections on Green Social Work Teaching and Training. Healthcare 10: 1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).