1. Introduction

The effects of social media on the political debate and their use in the election campaign were widely discussed politically and in the media during the 2025 federal election in Germany. A particular focus of the discussion was the importance of social media and digital formats for the voting behavior of young voters. Based on the observation that an increasing number of young people in Germany state that they inform themselves about politics primarily or even exclusively on social media (

infratest dimap 2025), numerous media outlets suggested that the election campaign needed to move online in order to get to young voter groups, as “Gen Z” could only be reached there (

Mrazek 2025). Based on the election results and post-election studies, which show a clear tendency among young voters towards the right and left fringes of the party spectrum (

Sonnenberg 2025), it was suggested that this voting decision was at least encouraged by the targeted social media strategies of the respective parties. In particular, the wide reach of individual representatives from the radical right Alternative for Germany (AfD) and the socialist Left Party on social media was seen as evidence that the election is decided online among young voters (

Hoppenstedt 2025) and that, particularly, the far-right AfD succeeded in shaping public opinion via social media (

Fairless 2025). In this context, the question was also raised as to what extent this reflects a change in the political socialization process: since young people primarily inform themselves about political issues via social media, it could also be assumed that politicization and their own political positioning are shaped by digital exchange (

Abendschön and Tausendpfund 2025). This assumes a generational effect, as seen in popular science debates about work and Gen Z’s motivation, though scientists increasingly question whether such a uniform effect exists (

Schröder 2018;

Rudolph and Zacher 2022). While these debates took up a great deal of public attention in the immediate aftermath of the German federal elections, they were mainly based on the analysis of content on social media accounts, both official party accounts and private accounts with political content (

Bösch and Geusen 2025). In addition, the SPARTA project (

SPARTA 2025), among others, was able to show at an aggregate level that the two extreme parties, Left and AfD, scoring highly with young voters, are particularly successful on social media platforms such as TikTok—often linked to individual high-reach politicians such as Heidi Reichinnek (

Schmalzried 2025). However, there is still a lack of analyses at the individual level that bring together the individual use of digital channels in the run-up to elections with the election advertising carried out there and ultimately, with possible effects on voting intention.

Against this background, this article investigates the effects of social media and digital channels on the information and voting behavior of young voters (aged 18–30) in the context of the 2025 German federal election. Given the relatively limited empirical research available to date on the real-world impact of social media on political attitudes and, above all, the voting behavior of young people, we take a decisively exploratory approach in this article. Based on a survey of three groups of young people from southern Germany with different educational backgrounds and career goals (vocational school students, students at universities of applied sciences for public administration, and political science students at a university), we focus on a total of four research questions. Based on (i) an overview of political interest and preferred political information channels, we examine (ii) which digital and/or analog channels young people use to communicate about political topics and with whom, (iii) which social media platforms they were particularly exposed to political topics on in the run-up to the federal election, and (iv) to what extent correlations between these digital campaigns and voting behavior can be identified.

2. Research on the Effects of Digitalized Political Communication on the Voting Behavior of Young Voters

With the increasing importance of digital election campaigns, not least fueled by developments in American presidential elections, scientific interest in the effect on the voting behavior of young voters in particular has also grown (

Lilleker et al. 2025;

Carvalho et al. 2023). In addition to problems of data access, major challenges in providing actual evidence of concrete effects on actual voting behavior persist (

Dimitrova and Matthes 2018). Despite all public and journalistic interest, this may explain why the number of systematic, empirically oriented studies on this topic—providing insights at the individual level—remains rather limited.

In the context of Danish parliamentary elections,

Ohme et al. (

2018) identify a “reinforcement effect” among first-time voters with regard to their voting decision through corresponding social media postings. In another study,

Ohme (

2019) shows that first-time voters were comparatively more often addressed directly by political actors via digital channels, but that this did not result in an above-average participation effect. Similarly,

Gherghina and Rusu (

2021) work out in the context of the Romanian presidential elections that social media influences the voting behavior of first-time voters, especially when their political understanding and interest are rather low.

Lee et al. (

2020) focus on the relationship between how social media platforms are used by their users and the probability that these users will also express their political ideals on them. While they found that, for a sample of US Facebook users, “relational use of social media was positively associated with political expression on Facebook” (

Lee et al. 2020, p. 1), this does not necessarily translate into an effect on voting behavior.

In a comparative study of the effects of politically oriented communication on social media among the EU’s 27 countries at the aggregate (country) level,

Mutascu et al. (

2025) found that, while communication on social media by left-wing parties decreased their chances at the ballot box, the opposite was true for right-wing parties. This makes social media an important tool for right-wing parties’ campaigns (

Mutascu et al. 2025, p. 11). Using aggregate data,

Bär et al. (

2025) also demonstrate that the number of votes received by constituency candidates in the 2021 German Federal Elections increased significantly with the number of impressions of their political ads on Facebook and Instagram (200,000 impressions, costing only about EUR 2000, predicted a 2.1% increase in votes). At the 2021 federal elections, this would have swayed the outcome in 12 out of 299 constituencies. The authors argue that this effect is substantial, particularly given that the majority of German voters are relatively old, whereas young voters, who can be best targeted via social media advertising, are much fewer in number (

Bär et al. 2025, p. 8–9). A randomized field experiment during the 2018 midterm elections in Florida instead yielded only extremely small effects of political advertisement on Facebook and Instagram at the precinct level (

Coppock et al. 2022).

There are also numerous studies from the global south on the effects of online political messaging and social media campaigns on young voters. Given the higher share of young people in these societies, the potential effects are particularly relevant here. A study from Ghana shows that political messages on social media can help to increase political efficacy, political knowledge, and political participation among young voters (

Dankwah and Mensah 2021). However, no partisan effects were tested in their analysis. Studies from Malaysia, on the other hand, provide mixed evidence:

Hassan et al. (

2024) show, based on a structural equation model, that, apart from political credibility and informativeness, two aspects inherent in social media are particularly relevant for communication with young voters and their final voting decision: interactiveness and political satire. This highlights the importance of direct engagement with voters and non-traditional political communication strategies, including entertainment elements (

Hassan et al. 2024, p. 1832). Based on a sample of Malaysian first-time voters,

Tan (

2022) finds, on the other hand, a negative effect of social media usage on voting behavior. Participants who relied heavily on social media for political information were less likely to register as voters and to actually vote in elections (

Tan 2022, p. 7–8).

Taken together, all these studies provide inconclusive evidence on the real-world effects of social media political campaigning.

Turning to Germany, systematic evidence for such effects—apart from the study by

Bär et al. (

2025)—is missing for the most part.

Hügelmann (

2023) found a stabilization effect in the turnout of young voters, which could at least indirectly (also) be attributed to a stronger approach via social media. However, the author also emphasizes the problem of drawing conclusions from the increased use of social media in election campaigns regarding the effectiveness in influencing individual voting behavior. This is where this article comes in, as it attempts to look at the effect of digital political communication over the course of the election campaign on voting intentions, not only in aggregate—as in

Bär et al. (

2025), but also at the micro level.

3. Research Questions

While this paper focuses on the actual occurrence and effects of digital campaigns, especially via social media, on individual voting behavior, we were also interested in the general impact of increased social media use on processes of political socialization. Accordingly, the investigation is divided into four sub-studies, each investigating a specific set of research questions.

The first sub-study tries to provide some context regarding the general political interest of young voters and how they obtain political information. It is assumed that political interest is not distributed equally among young voters, especially when different layers of politics (e.g., communal, federal) are considered. Given the stronger media coverage, it is suggested that federal politics and international politics attract higher interest levels than state or local politics.

R1a: How strong is the interest of young voters in local politics, state politics, federal politics, and international politics?

R1b: To what extent do young voters rely on digital and social media to inform themselves about politics?

The second sub-study addresses the change in dynamics of debating political issues online or offline as an important prerequisite of the political socialization process. When adolescents obtain political information primarily through social media or the internet, it seems plausible that the political exchange, e.g., discussing political topics, also shifts towards the digital space.

R2: Do young voters debate political issues online in forums and social media rather than with family members and friends in an offline setting?

The third sub-study turns to the actual digital campaigning strategies used to reach young voters. Based on the previous findings that political parties increasingly use digital means to reach voters more effectively (

González-Cacheda and Cancela Outeda 2025;

Sandri et al. 2024), we wanted to investigate how political parties use different channels and platforms to reach young voters. For the purposes of this study, we are using the term ‘digital campaigning strategies’ in a very specific way. Our focus is exclusively on how a party attempts to reach young voters online. We deliberately avoid dealing with the different types of content, psychological persuasion strategies and framing techniques that may be employed (these are clearly topics in their own right), and instead focus on the channels that young voters used to obtain political information in the run-up to the federal election and the types of approaches (direct/indirect) that parties chose to reach young voters online.

R3a: Do young voters experience different levels of exposure to political information across different digital channels and social media platforms?

Additionally, we were interested in the respective sources of political information. Parties could either try to address young voters directly, leverage the popularity of high-ranking candidates, or connect with young voters through intermediaries, e.g., influencers (

Von Sikorski et al. 2025), or viral marketing tactics (

Leppäniemi et al. 2010) that involve “using” private accounts to spread political messages. While parties may prefer the direct approach to control the message, using influencers provides them with a different level of connectivity and authenticity vis-à-vis the target audience, bridging the gap between political parties and the youth (

Weber 2017).

R3b: Do political parties use both direct and indirect approaches to reach young voters online?

The fourth sub-study focuses on the impact of digital political campaigns on voting behavior. Given the lack of studies assessing the impact of digital campaigning on the individual level, we were interested in the self-perception of young voters regarding their influenceability in contrast to other people. We were specifically interested in a potential illusory superiority bias (

Hoorens 1993), meaning that voters will underestimate the effect of political campaigning on their voting behavior relative to other individuals.

R4a: Do young voters rate the influence of online political posts during election campaigns on others higher than the influence on themselves?

Finally, we investigated the effect of exposure to political posts on individual voting behavior. In light of the emerging evidence suggesting that populist parties can leverage social media particularly well for campaigning, also because emotional content, e.g., on migration, anti-elite themes, or gender, is algorithmically promoted on platforms such as TikTok (

Cartes-Barroso et al. 2025;

González-Aguilar et al. 2023;

Phillips 2025), we formulate the following research question.

R4b: Is the likelihood of voting for populist parties higher for those who are exposed to much political content on social media?

Messenger groups, e.g., on Telegram or Signal, which can be open or closed and typically do not exercise any control over the content posted there (unlike platforms such as Facebook or Instagram, where there is greater control over content), have become an alternative for many people, who see them as a functional equivalent to social media platforms. Due to the perceived lack of control and often encrypted communication, it is plausible to assume that these groups (especially the closed ones) are used to exchange political views that are far removed from the political mainstream and may even be directed against the political system itself.

R4c: Is the likelihood of voting for the radical right AfD higher for those who are exposed to political content on messengers?

4. Materials and Methods

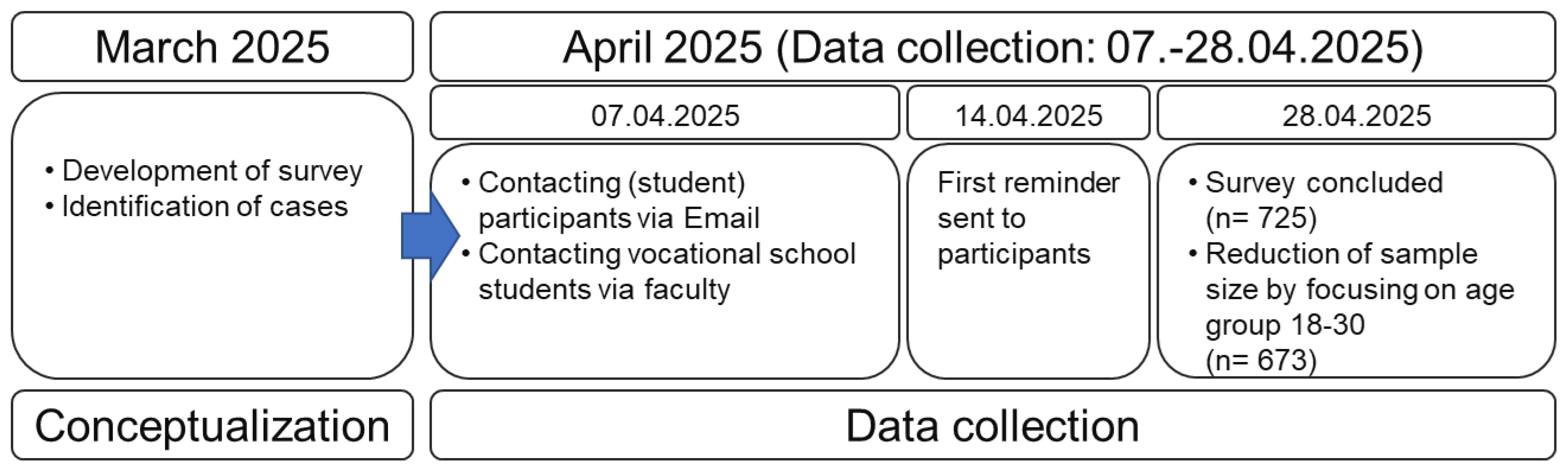

This study is based on an online survey conducted in the wake of the 2025 federal election (survey period 7–28 April 2025). The questionnaire can be found in the

Supplementary Material S1. A total of 725 people took part in the survey. The survey was conducted among students at two universities of applied sciences for public administration (Univ. Appl. Sci. Ludwigsburg,

n = 404) and Univ. Appl. Sci. Kehl (

n = 171), political science students at the University of Freiburg (

n = 90), and pupils at a vocational school in Rhineland-Palatinate (

n = 60). Vocational schools train students for specific careers, while universities of applied sciences in administration prepare them for local civil service. Political science students at universities may pursue academic or professional paths. In this way, the aim was to include young people from different educational backgrounds in the sample, such that, although the sample is not a representative sample of young people in Germany, certain potentially different characteristics—such as educational background or level of education—can be analyzed in relation to the research question. At the same time, the sample only contains people who currently live in the southwest of Germany (BW or RP). While this prevents generalizations of our results to other parts of Germany, it can be reasonably assumed that for our research questions related to internet and social media usage before elections, other covariates such as age, gender, or educational background are more important. Therefore, keeping the geographic region constant is not a major problem.

As we are interested in the views of young people in this analysis, all people who stated that they were older than 30 were removed from the sample (

n = 52; the relatively high number of older participants is mainly due to students at Ludwigsburg University of Applied Sciences, including former soldiers and second-degree students). Of the remaining 673 participants, the vast majority answered all the questions in the questionnaire (

Figure 1). Since this study is based on an anonymous online survey, no ethics approval was required under German law. Personal data (e.g., age and gender) were processed with participants’ explicit written consent per GDPR Art. 9 (2) §a. Participants could withdraw at any time without consequences. Although not medical research, the study follows the WMA Declaration of Helsinki’s ethical principles (

https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki/ accessed on 5 December 2025). Replication data and documentation are available at Harvard Dataverse:

https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/QYL98L.

The largest proportion of missing values (3.9%) was the question about the party voted for in the 2025 general election (see

Appendix A Table A1).

Table 1 provides an initial overview of the data. In vocational schools, there are particularly many in the youngest age group of 18–21-year-olds. At 21.4 years, the average age there is also somewhat lower than in the other three groups, where it ranges between 22.2 (Ludwigsburg and Freiburg) and 22.5 years (Kehl). There are also slightly more men than women in the sample at the vocational school, whereas all three other groups contain twice as many women as men in some cases. In percentage terms, the university had the highest number of people who indicated “diverse” in their gender.

5. Results

5.1. Sub-Study 1: General Political Interest of Young Voters and Preferred Means of Political Information

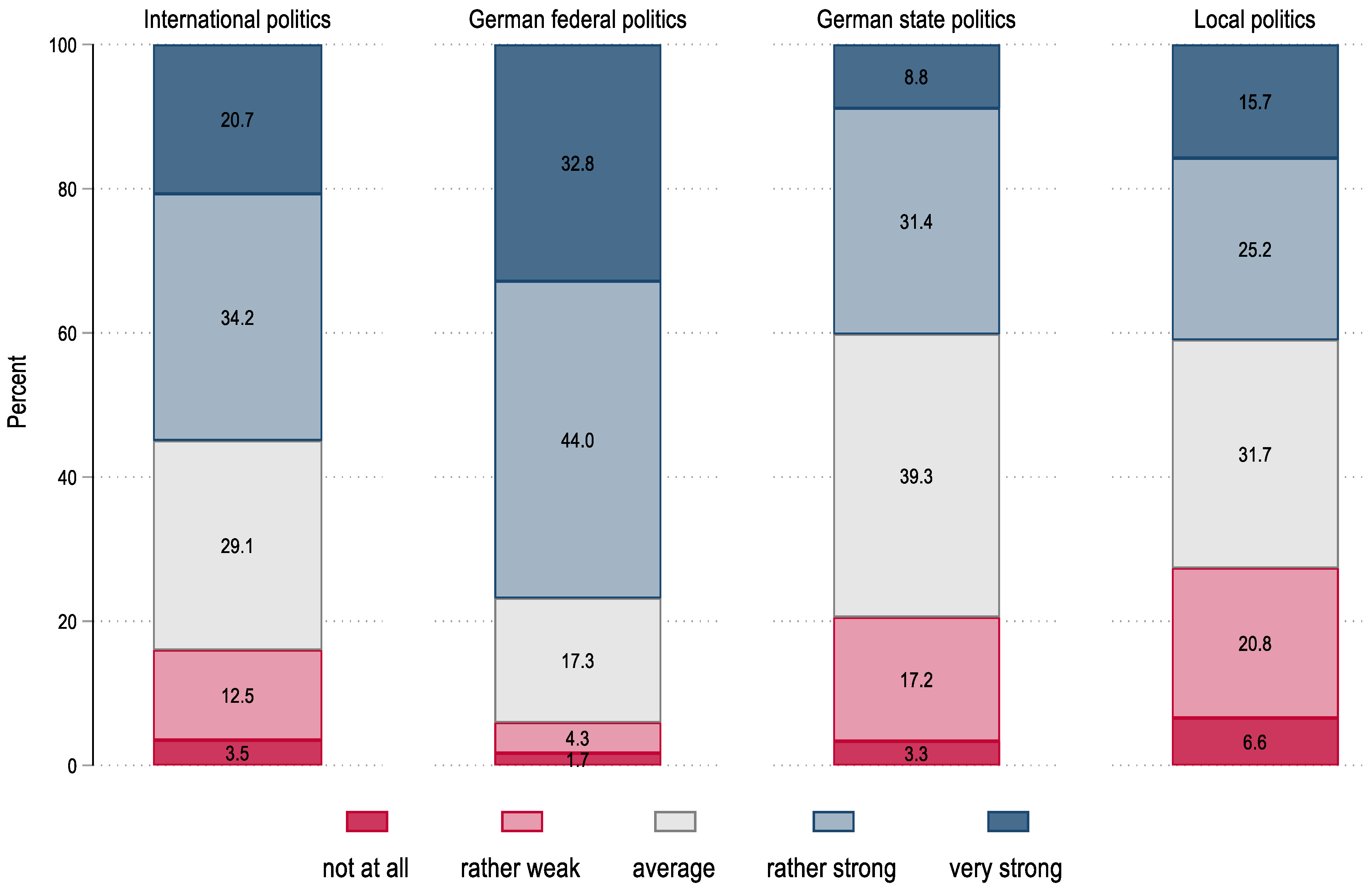

In order to gain a deeper understanding of the political interest of young voters, the participants were asked to indicate their interest in politics differentiated by levels (local, state, federal, international). Overall, there are clear differences in the level of interest in the different political levels (see

Figure 2). While more than ¾ of participants indicated a rather strong or very strong interest in federal politics, this figure is around 55% for international politics and only around 40% for state and local politics. The proportion of those stating only a weak interest or no interest at all is also highest in these areas.

There are also certain differences when differentiated by gender, age, and the four survey groups (see

Figure 3). While interest in federal politics is highest among both men and women compared to the other three policy areas, men are more interested in international politics, while women—and of these, especially slightly older ones—are more interested in state and federal politics. However, this difference is partly a composition effect of the sample, since, as

Table 1 has shown, older women are particularly strongly represented in the two schools of public administration, where there is generally a greater interest in state and local politics. At the same time, the chart shows that there does not appear to be a uniform age effect for both genders. Particularly in the age range with the most participants (approx. 19–24 years), the values for average interest in politics are not clearly systematic. Only interest in state and local politics appears to increase slightly among women as they become older, but this, in turn, is probably due at least in part to the composition effect mentioned above. In general, interest in politics (at all levels) is less pronounced among vocational school students than among the two student groups. In a direct comparison between the two types of university, the different levels of interest in local politics are particularly pronounced. However, this is hardly surprising in that students at universities of public administration almost inevitably have to have an interest in local politics for their future careers. The lower part of

Figure 3 also shows the distinctiveness of political science students, who consistently report a very strong interest in international and federal politics, but whose interest in state and local politics is almost at the same low level as that of vocational school students.

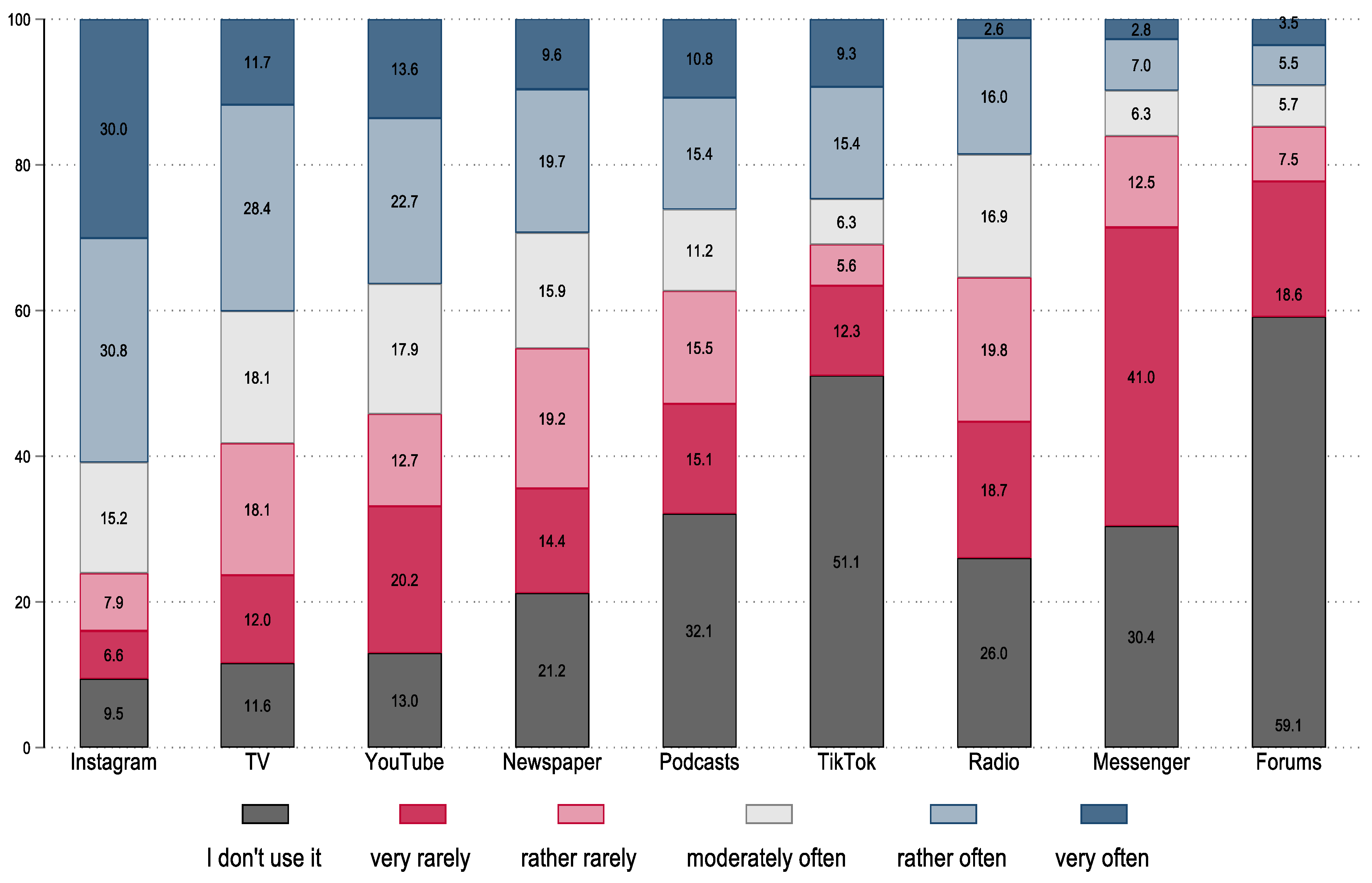

Figure 4 shows which channels young people use most frequently to obtain political information. Instagram is by far the most popular channel among participants. Sixty percent say they use Instagram very often or fairly often to obtain information about politics. In contrast, the more traditional information channels—TV, newspapers, and radio—are used by only about 40, 30, and 20 percent, respectively. The large differences regarding channels that are not used at all are also interesting. While Instagram, TV, and YouTube are very rarely not used at all and are therefore present in the lives of almost all young people, the TikTok platform and internet forums are only used by a minority of participants. This finding is surprising since public perception has recently often suggested an image of an all-encompassing “

TikTokization of politics” among young people (

Ruhland 2025). Podcasts, which played an important role in the last US presidential election campaign, also seem to be far less relevant in Germany.

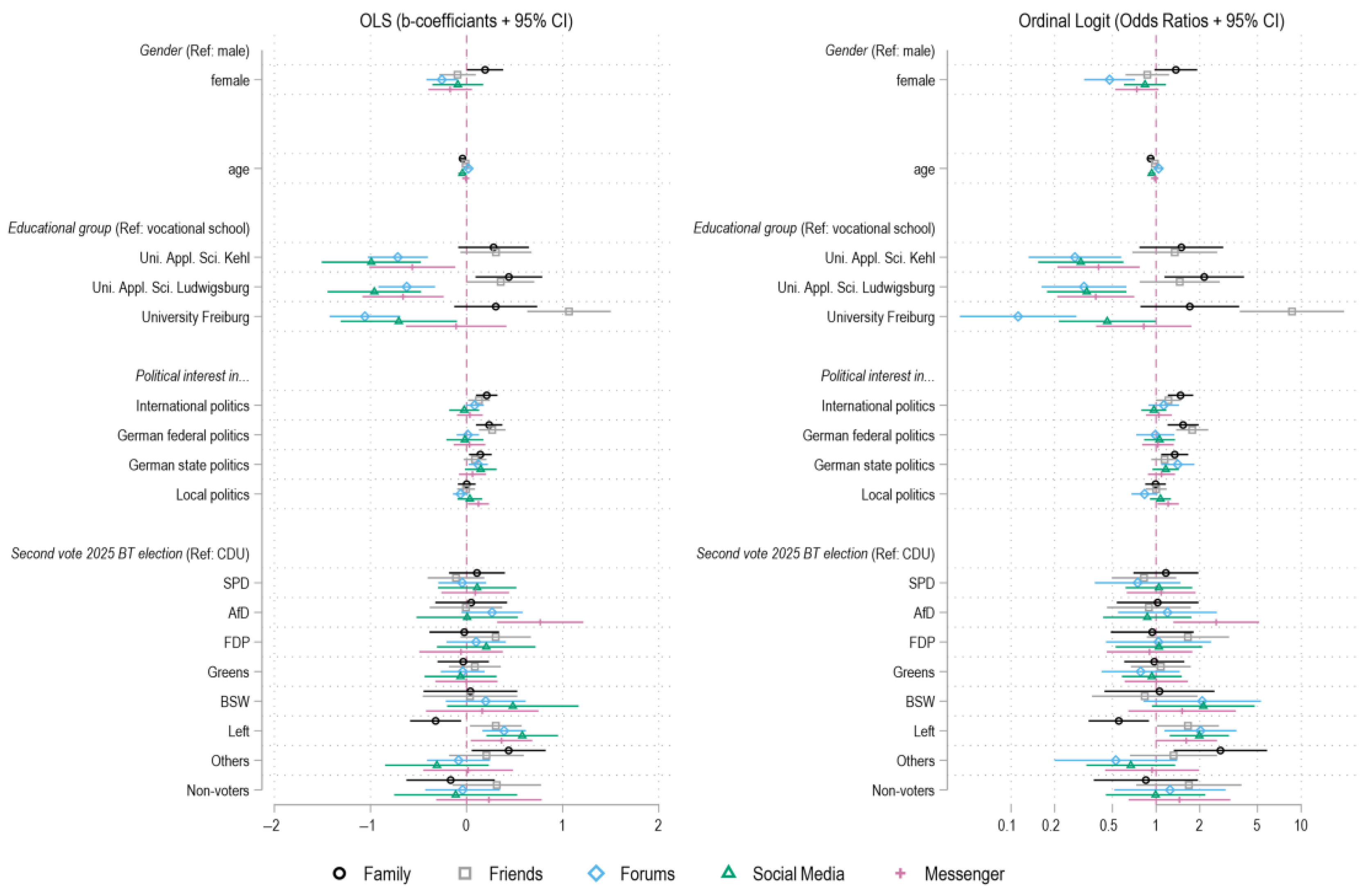

In order to investigate whether there are systematic differences in the use of the individual channels for political information, an OLS regression is estimated, which includes socio-demographic factors (age, gender and recruitment group as a proxy for education level) and political variables (the previously described political interest in the four political levels and the question of which party was voted for in the 2025 federal election) as explanatory factors (see

Figure 5). The six-point scale of the frequency of using a channel for political information from “I do not use” to “very often” is assumed to be metric for simplicity’s sake, and an ordinal logistic regression estimated as a crosscheck gives an almost identical picture in terms of effects and significance (see

Appendix A Figure A1). For this reason, the OLS results, which are somewhat easier to interpret, are reported here.

There are some very clear differences in usage behavior. For example, age is negatively correlated with the frequency of obtaining political information via TV, Instagram, and TikTok: ceteris paribus, an additional year of TV use leads to an estimated 0.076 lower value on the six-point frequency scale. For Instagram and TikTok, it would even be 0.1 and 0.11. What seems small at first becomes more meaningful when considering the maximum age range in our sample: a 30-year-old participant, on average, gives 1 whole point less on the frequency scale from 0 to 5 for TV and 1.3 and 1.4 points less for Instagram and TikTok than an 18-year-old. Podcasts, on the other hand, are mainly used by older people for political information. There are only a few differences in terms of gender (here and in the following regression analyses, we drop the very small ‘diverse’ gender category, which only comprises eight participants; no meaningful statistical statements would be possible for them): women use newspapers, forums, and YouTube less frequently, whereas they use Instagram and TikTok slightly more often to obtain political information. In terms of educational groups, it is particularly evident that political science students at the University of Freiburg use newspapers and podcasts more frequently for political information. In general, it is also clear that it does not make sense to assume a uniform use of information channels, especially regarding digital channels. While YouTube and Instagram are used about equally across all four education groups, messengers, forums, and TikTok are particularly popular among vocational school students. In contrast, university students use podcasts for political information more frequently than all other groups.

There are also certain differences in terms of political variables. Those with a strong interest in local politics are more likely to use traditional media such as newspapers and radio. While Instagram is also used, they use internet forums significantly less often to inform themselves about politics. Interest in the other three political levels, on the other hand, is less significantly linked to the frequency of use of a particular information channel. However, a high level of interest in state-level politics is positively correlated with the use of radio and internet forums. In contrast, those interested in international politics more often use podcasts and YouTube to inform themselves about politics. A high interest in federal politics, on the other hand, is positively correlated with the use of newspapers and Instagram. There are much clearer differences in relation to the party voted for in the 2025 federal election. Voters of the AfD, the Left, and non-voters inform themselves less frequently via TV than the reference group of Christian Democratic Union (CDU) voters. Conversely, it is precisely these voters who are more likely to inform themselves via forums than CDU voters. The AfD is also the only party whose voters are significantly more likely to obtain political information via internet forums compared to the other parties. While there are no major differences among voters of the various parties on Instagram, participants who voted for the AfD, the Linke, and, above all, the populist Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance (BSW) use TikTok significantly more often for political information.

5.2. Sub-Study 2: Changes in Dynamics of Debating Political Issues Online or Offline

Figure 6a shows where and with whom the participants discuss political issues across the entire sample. Family and friends are by far the most relevant spheres in which political exchange takes place. Only a small minority state that they use the internet to discuss political issues very regularly or at least fairly regularly. Forums and messengers are never used by more than half of the participants to talk about politics. But even on social media, more than 75 percent rarely discuss political topics. It can therefore be stated that political exchange still takes place mainly “offline” in the young age cohort we examined.

Analogous to the procedure for the frequency of use of the various information channels, an OLS regression was calculated to determine the extent to which certain groups of people prefer to communicate about politics with family, friends, or via one of the three online channels (see

Figure 6b). The analysis shows that women discuss politics more often with family, but less often than men in internet forums. Age only plays a role in exchanges within the family: older respondents do this less frequently than younger respondents. In terms of educational groups, there are again clearer differences. While university students talk about politics with friends much more frequently than the reference group of vocational school students, they use forums and social media less often than the latter. When it comes to the use of messengers, however, university students do not differ from vocational students, in contrast to students at universities of public administration, who use messengers less frequently for political exchange. Looking at the four variables that measure political interest, it can be seen that the greater the political interest in international and federal politics, the more frequently participants discuss politics with family and friends. The more interested respondents are in state politics (or local politics), the more likely they are to use forums (or messengers) for political exchange. Looking at the participants according to their voting decision, there are only relatively minor differences. For example, people who voted for the AfD are significantly more likely to discuss politics via messenger than the comparison group of CDU voters. Those who voted for the Left, on the other hand, talk less often about politics with their family and more often via forums and social media—again in comparison to CDU voters.

5.3. Sub-Study 3: Digital Campaigning Strategies Used to Reach Young Voters

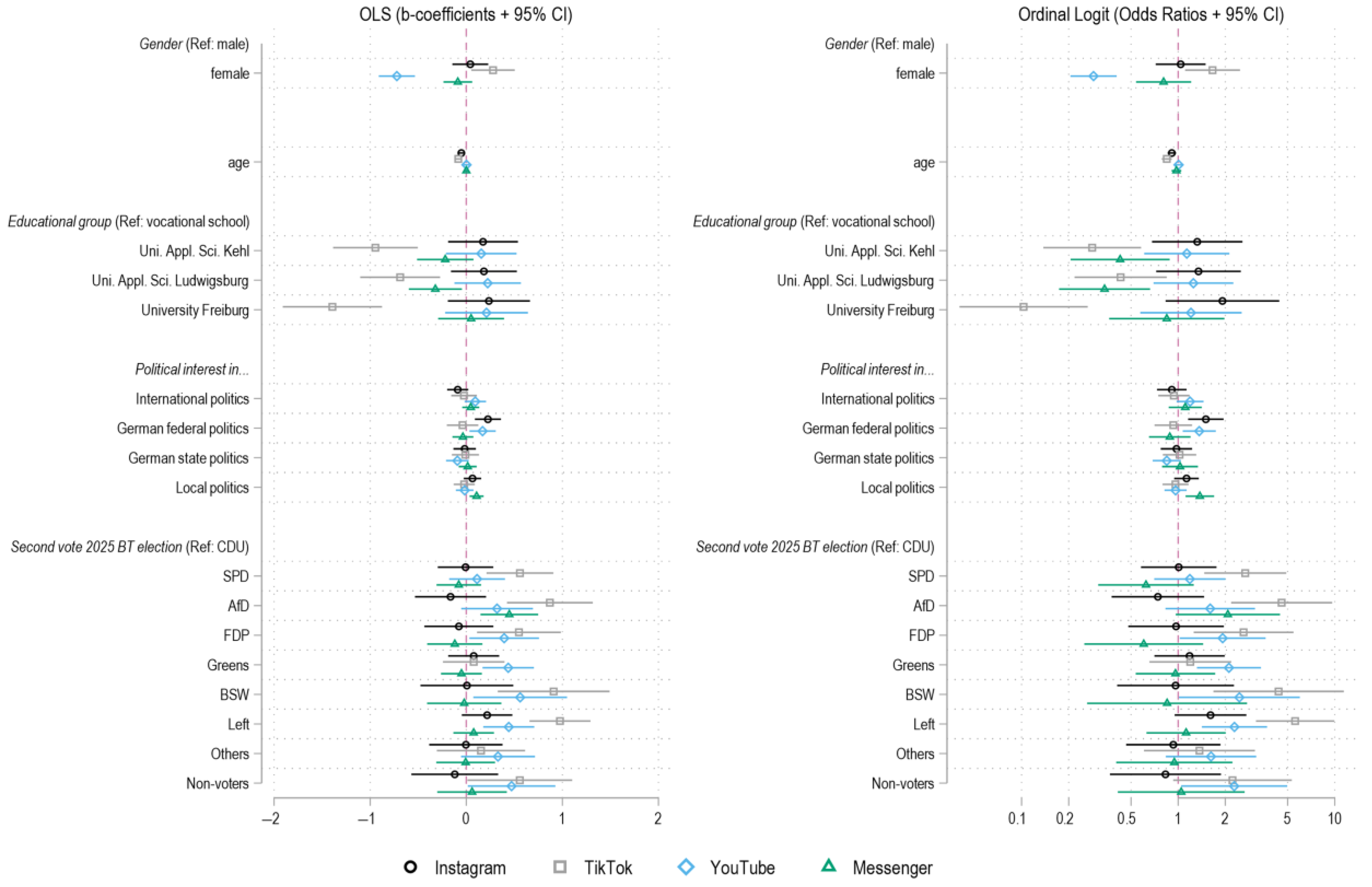

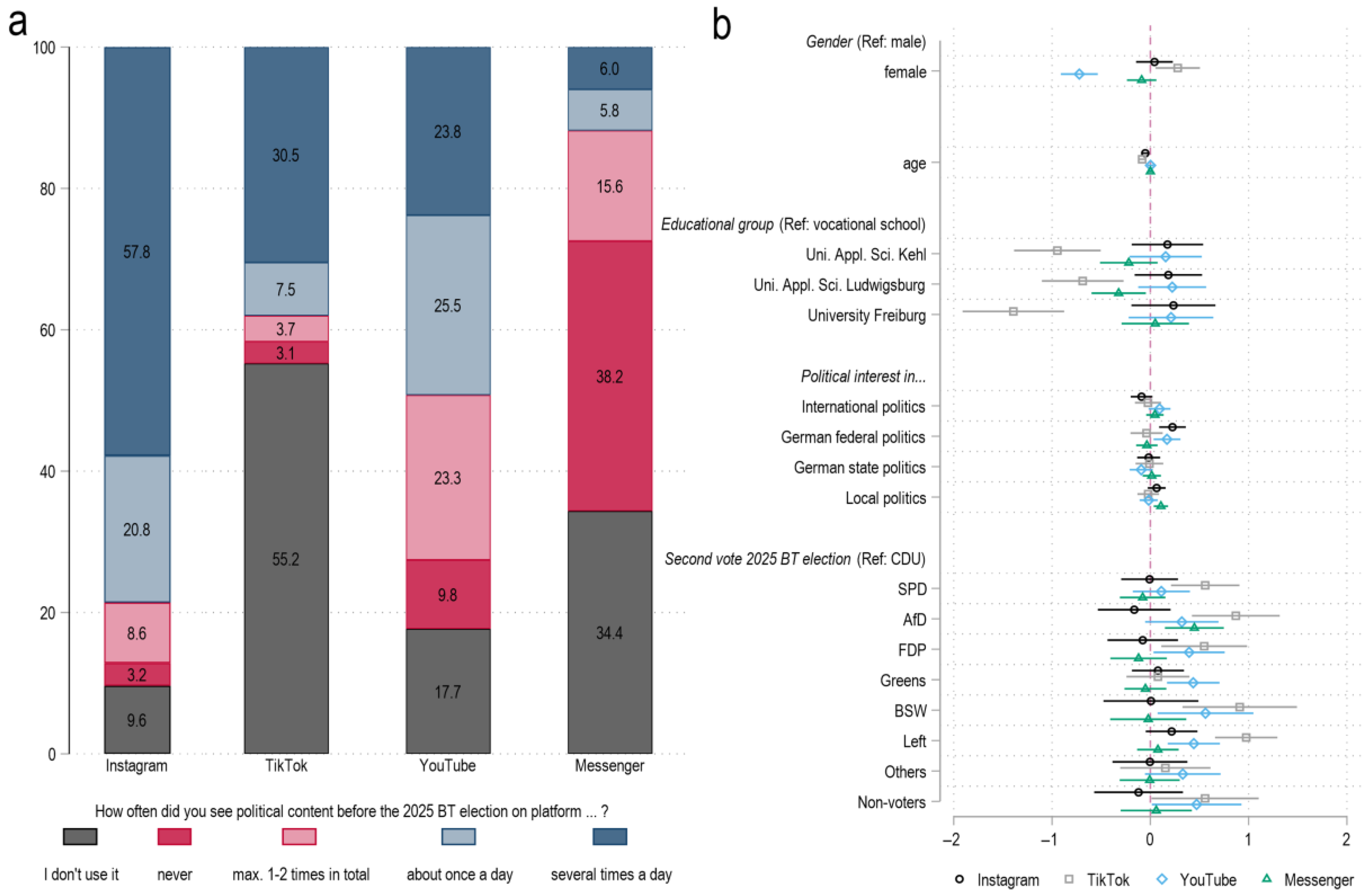

Figure 7a is dedicated to the question of which online channels were used to present political content to young people in the run-up to the 2025 federal election. In general, Instagram was the most important platform here. Almost 80% of respondents stated that they were shown political content there at least once a day before the election. The vast majority of users on TikTok also receive political content at least once a day. However, as shown above, it must be taken into account here that a much larger proportion of respondents do not use TikTok at all. Participants were reached by political content much less frequently via YouTube and especially via Messenger.

In a second step, an OLS regression is used to test whether certain groups of people were shown political content more frequently via certain channels in the run-up to the German federal elections (see

Figure 7b). For this analysis, the two categories “I do not use” and “never” were merged into a single category, as it makes no difference from the participants’ perspective whether someone does not use a platform at all or has only not been shown any political content there. The results indicate that certain groups of people were indeed more likely to see political content on certain platforms. For example, in comparison to men, women saw less political content on YouTube, but saw it more often on TikTok. The older the respondents, the less frequently they were shown political content on TikTok and Instagram. With regard to the education groups, differences are particularly evident in relation to TikTok. Vocational school students in particular frequently saw political content on this platform before the election. However, the level of political interest in one of the four levels plays a subordinate role. The only significant effects can be seen for federal politics (the greater the interest, the more frequently political content was displayed via Instagram and YouTube) and local politics (the greater the interest, the more frequently political content was displayed via Messenger). The following picture emerges when comparing respondents according to their second vote in the 2025 federal election: Compared to the reference of CDU voters, no voter group shows a significantly different frequency of having been presented with political content via Instagram. The situation is different with TikTok. While CDU and Green voters obviously used this channel less frequently, voters of the Left, the BSW, and especially the AfD were shown political content significantly more often before the election. AfD voters also stand out in that they are the only ones who saw political content significantly more often via Messenger during the election campaign. On the other hand, the differences are smaller for YouTube: CDU voters were shown political content somewhat less frequently via this channel compared to almost all other voter groups.

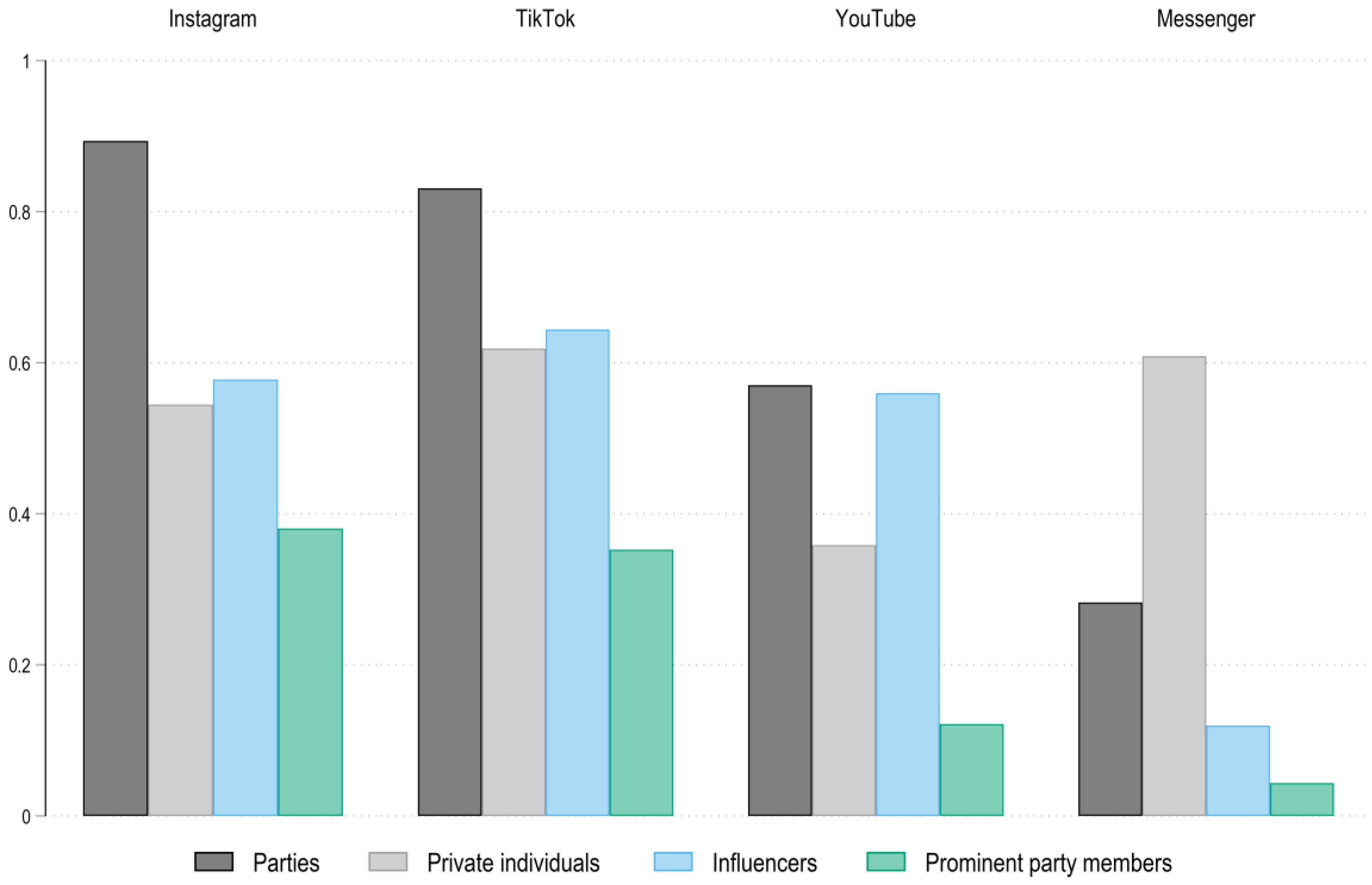

Respondents were then asked from whom these posts that they perceived as political content came: from political parties, private individuals, influencers, or well-known politicians. Respondents could select several answers if they had seen political posts from different groups.

Figure 8 shows the result. On both Instagram and TikTok, between 80 and 90 percent of respondents stated that the political content they saw in the run-up to the general election also came from political parties. However, prominent party members were identified as senders much less frequently. While Instagram and TikTok differ only marginally in terms of the composition of the senders of political posts, it can be seen that influencers were associated with political posts just as often as parties on YouTube. Prominent party members, on the other hand, only very rarely: Only just over 10% of those who saw political items on YouTube stated that these were from prominent party members. The latter is also the case with messengers, where private individuals in particular are associated with the political content that was disseminated before the parliamentary elections.

Even though the majority of online political posts seen by respondents during the election campaign did not appear to come from prominent party members, it is interesting to see which politicians were perceived as particularly active. Heidi Reichinnek (Left Party) dominated TikTok and, with Green candidate Robert Habeck, also Instagram. Other politicians—even Chancellor Olaf Scholz (Social Democratic Party, SPD) and challenger Friedrich Merz (Christian Democratic Union, CDU)—were mentioned less often (see

Appendix A Table A2 for a top-10 list).

5.4. Sub-Study 4: Impact of Digital Political Campaigns on Voting Behavior

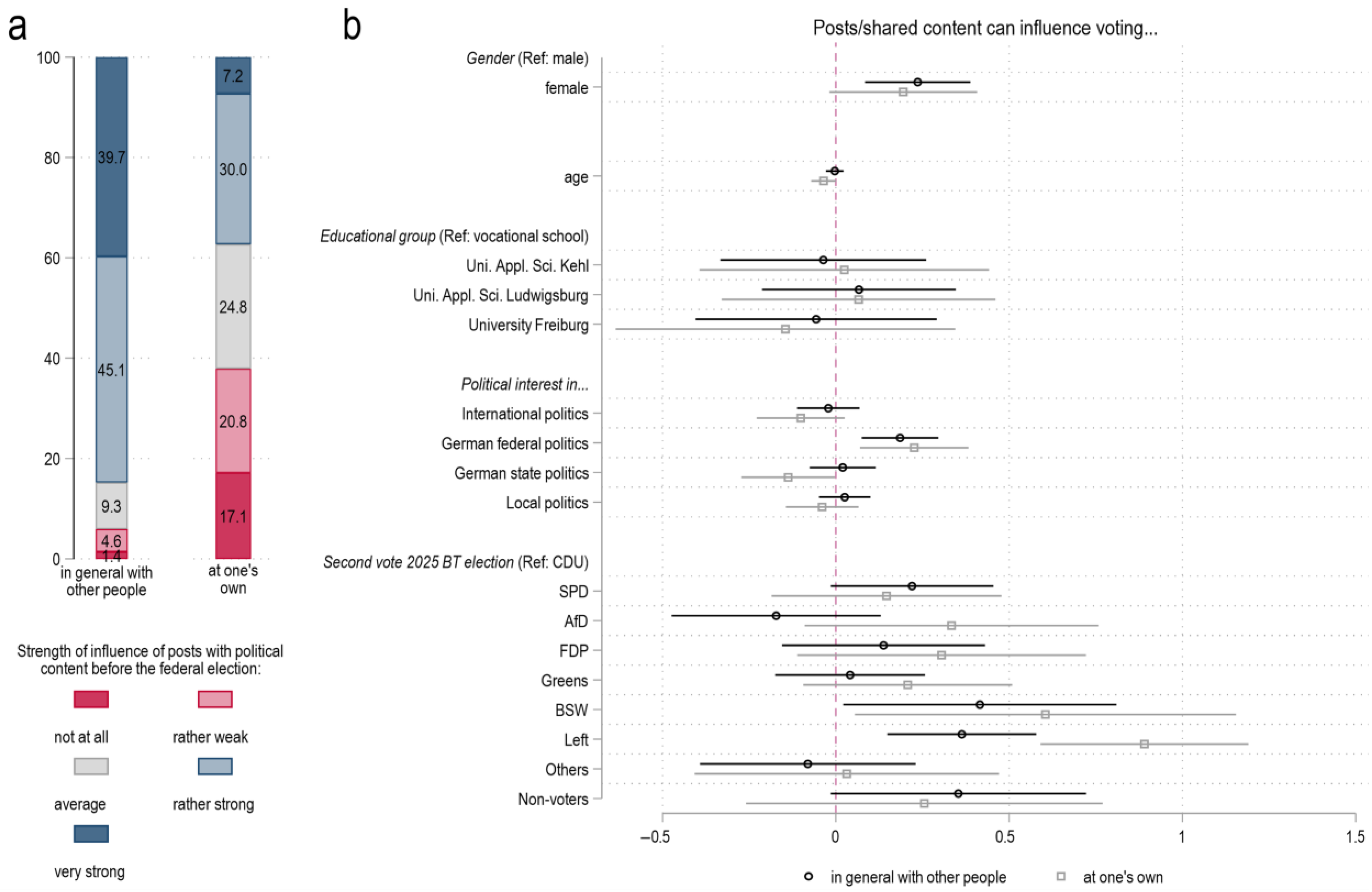

Respondents were asked to indicate the extent to which they believe that such political content, which is disseminated via the online channels mentioned, can influence other people or themselves in their voting decision.

Figure 9a shows that while around 85% of respondents assume that other people can be rather or even very strongly influenced by such posts, only 37% assume this for themselves. The result of the OLS regression shows that certain groups of people are more likely to assume that others or themselves are influenced than others (see

Figure 9b). Women in particular believe that others can be influenced by such posts. However, there are no significant differences according to age and education group. The more interested a respondent is in federal politics, the more likely they are to assume that posts will influence their decision to vote in the federal election. Compared to CDU voters, BSW and Linke voters in particular assume that other people, but above all themselves, are strongly influenced by posts in their own voting decision.

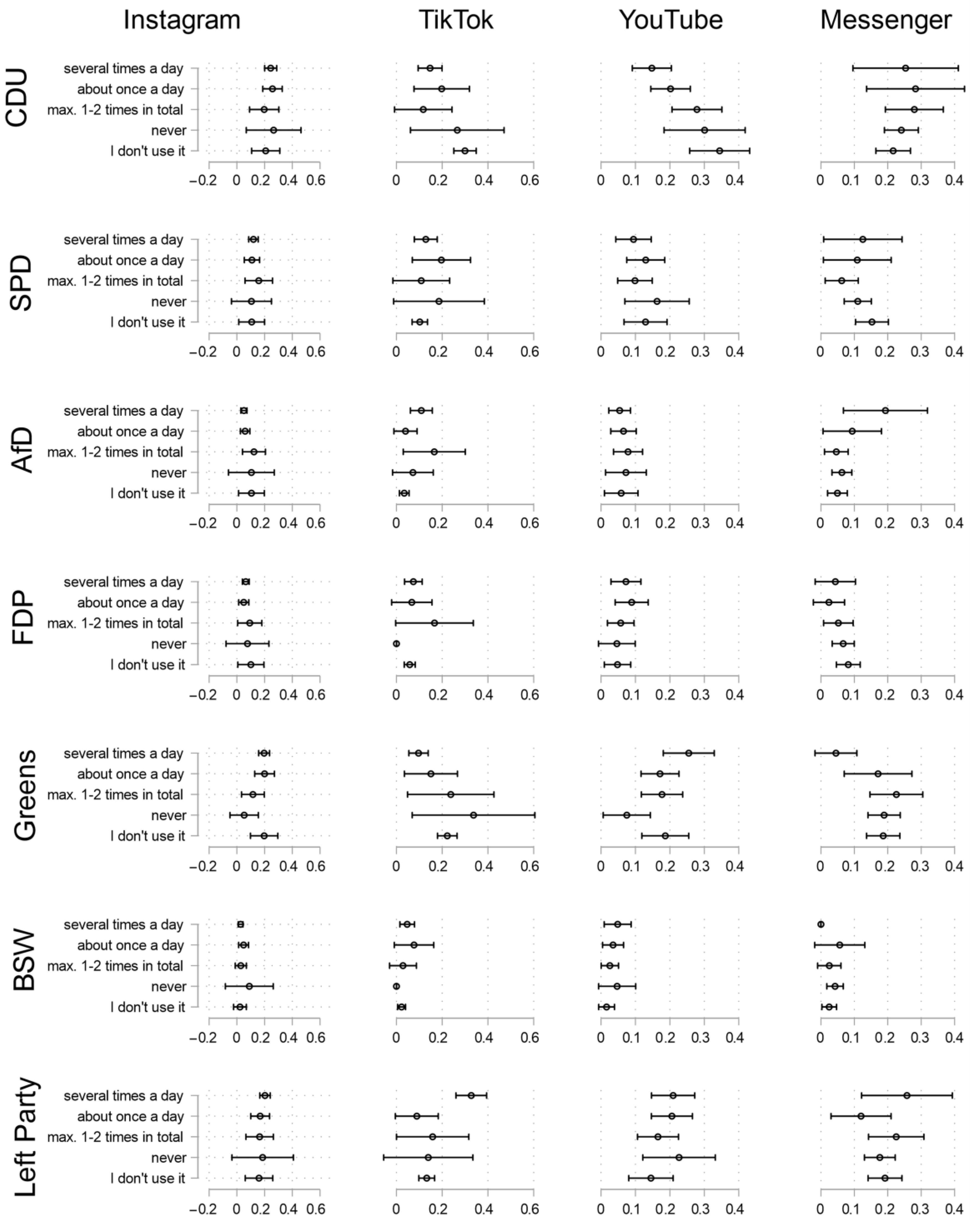

As a final step of the analysis, the voting decision is now modeled using a multinomial logistic regression depending on the frequency of having been presented with political content via certain online channels before the elections. In addition to this independent variable, which is of primary interest to us at this point, the models also control for the factors known from the previous analyses: gender, age, education group, and political interest for the four political levels.

Figure 10 presents the predicted probabilities of voting for a particular party estimated on the basis of this model when the frequency with which a person was shown political content via Instagram (or TikTok, YouTube, or Messenger) before the general election changes.

The plots show that if political topics were disseminated on certain online channels before the general election, this may well have led to a higher probability of voting for certain parties. However, it can be said that no channel has the same statistical effect on all parties; a differentiated approach is required here. For example, people who were presented with political content on TikTok several times a day before the federal election had a predicted probability to vote for the Left Party of around 35% which is significantly higher than for any other party in this group. Accordingly, the Left Party benefited the most from frequent TikTok posts, whereas the opposite picture prevails for the Greens on TikTok: the more often someone saw political topics on TikTok before the election, the less likely they were to have voted for the Greens. However, the Greens benefit the most from frequent political YouTube videos, whereas this is not the case for the CDU. No party can systematically benefit from frequent Instagram posts. While it makes no significant difference to the likelihood of voting for the AfD whether one has seen many YouTube or TikTok videos or Instagram posts with political content before the election, this radical right party benefits from frequent political content in messenger groups.

6. Discussion

Much has been written and debated over the course of the 2025 German federal election about how central the digital election campaign was for the political socialization and “winning over” of young voters and how it was the cause of voting trends towards the political fringes. However, the empirical substantiation of these claims has been largely missing. Although there are already some studies on the effects of digital election campaigns on young voters, they mostly focus on a specific platform—e.g., TikTok (

Zamora-Medina et al. 2023)—and, in particular, on fundamental mobilization and perception effects—e.g., in relation to voter registration (

Unan et al. 2024) or the persuasion strategies used there (

Gherghina and Mitru 2023). Building on this research, the aim of this study was to examine in more detail the role that digital channels can play in the general political socialization, information, and persuasion of young voters in the context of election campaigns.

The first key finding here is that, contrary to popular belief, we do not find a clear generational effect. While 18–30-year-olds use traditional media less and prefer platforms like Instagram, differences within this group exist in political interest and media use. Notably, TikTok’s importance for attracting young German voters is questionable, despite many studies highlighting its role in political information (

Cervi et al. 2023;

Zamora-Medina et al. 2023). In fact, at least in our sample, this channel clearly plays a much less important role for a large number of young voters—with the exception of voters from the AfD, Linke, and BWS parties—than is generally assumed, even if an educational effect can be identified here: vocational school students (identified as the group least interested in politics) in particular use TikTok. In line with previous studies (

Olof Larsson 2023), Instagram appears to be the most important digital source of political information for young voters, but there are also differences in the preferred channels depending on political orientation.

Secondly, the assumption that the exchange on political topics and thus in part also the further political socialization of young voters is increasingly shifting online (

Oberle et al. 2023) cannot be confirmed on the basis of the present study. While the young voters in our sample do increasingly rely on digital means to become politically informed, they continue to discuss political issues primarily offline with family and friends. Only among young AfD and Left Party voters does digital exchange appear to play a greater role. In this context, it is conceivable that this avoidance of digital spaces is triggered by the fear of incomprehension in the social environment for politically rather extreme opinions (

Shim and Oh 2019). The online disinhibition effect (

Lapidot-Lefler and Barak 2012), according to which online communication is conducted more openly by communication participants, partly because it is perceived as more anonymous—which also includes the possibility of advocating extremist positions more easily—should also be mentioned at this point. As a result, the dangers of political polarization—not for all young people—but for those who are active in extremist echo chambers online are rightly being increasingly considered by research (

Bliuc et al. 2021;

Su et al. 2022).

It is clear that the German federal election campaign has become more digital, particularly with regard to young voters, and that the parties have become more involved with the information environments of the younger generation. This applies in particular to the “central election campaign arena” Instagram: Almost 80 percent of respondents said they had been shown political content there at least once a day before the election. The vast majority of users also receive political content on TikTok at least once a day, although this channel appears to be far less relevant to society as a whole due to its significantly lower usage compared to Instagram and YouTube. Nevertheless, it should not be overlooked that the way in which TikTok’s style of content presentation is partly adopted by other platforms, leading to what can also be described as a partial

TikTokization of the social media landscape (

Brauer 2025;

Fischer et al. 2025). In this respect, it is certainly relevant when it is shown that TikTok, which in our study is primarily used by vocational school students for political information, is said to have a politically polarizing effect (

Boppana 2022;

Widholm et al. 2024). Participants reached political content much less frequently via YouTube and especially via Messenger.

The results indicate that certain groups of people were indeed more likely to be shown political content via certain platforms. In addition to gender and age effects with regard to TikTok, an education and party preference effect should be emphasized. Here, vocational school students in particular frequently viewed political content before the election, as did voters of the Left, the BSW, and, above all, the AfD. On the one hand, this result could be explained by “simple” political messages that are easy to communicate in the logic of the platform. On the other hand, it could also be due to the greater presence of the parties (

Righetti et al. 2022), which specifically contribute to certain content going viral. These are often influencers (

Riedl et al. 2023) who initially operate non-political channels, but who take clear political positions in these channels, such as

Aktien mit Kopf,

Vermietertagebuch, or

Hoss & Hopf.

Party content dominates, but influencers also appear to be increasingly important in digital election campaigns, as has already been shown in other studies (

Goodwin et al. 2023)—also for the German context (

Borchers 2025;

Klüver 2024;

Sehl and Schützeneder 2023). However, content from individual prominent party members played a far less important role than often portrayed in the media debate—Heidi Reichinnek certainly still had the greatest influence here.

This study supports the finding that people usually overestimate themselves, including with regard to the ability of political information to influence voting decisions. 85% of respondents assume that other people can be rather or even very strongly influenced by such posts, but only 37% assume this for themselves. Further analysis showed that the likelihood of voting for certain parties is certainly related to political content on suitable channels. This correlation was particularly evident in the case of Die Linke and TikTok. In light of this empirical data, the Heidi Reichinnek effect, as stated by the media, cannot be entirely dismissed.

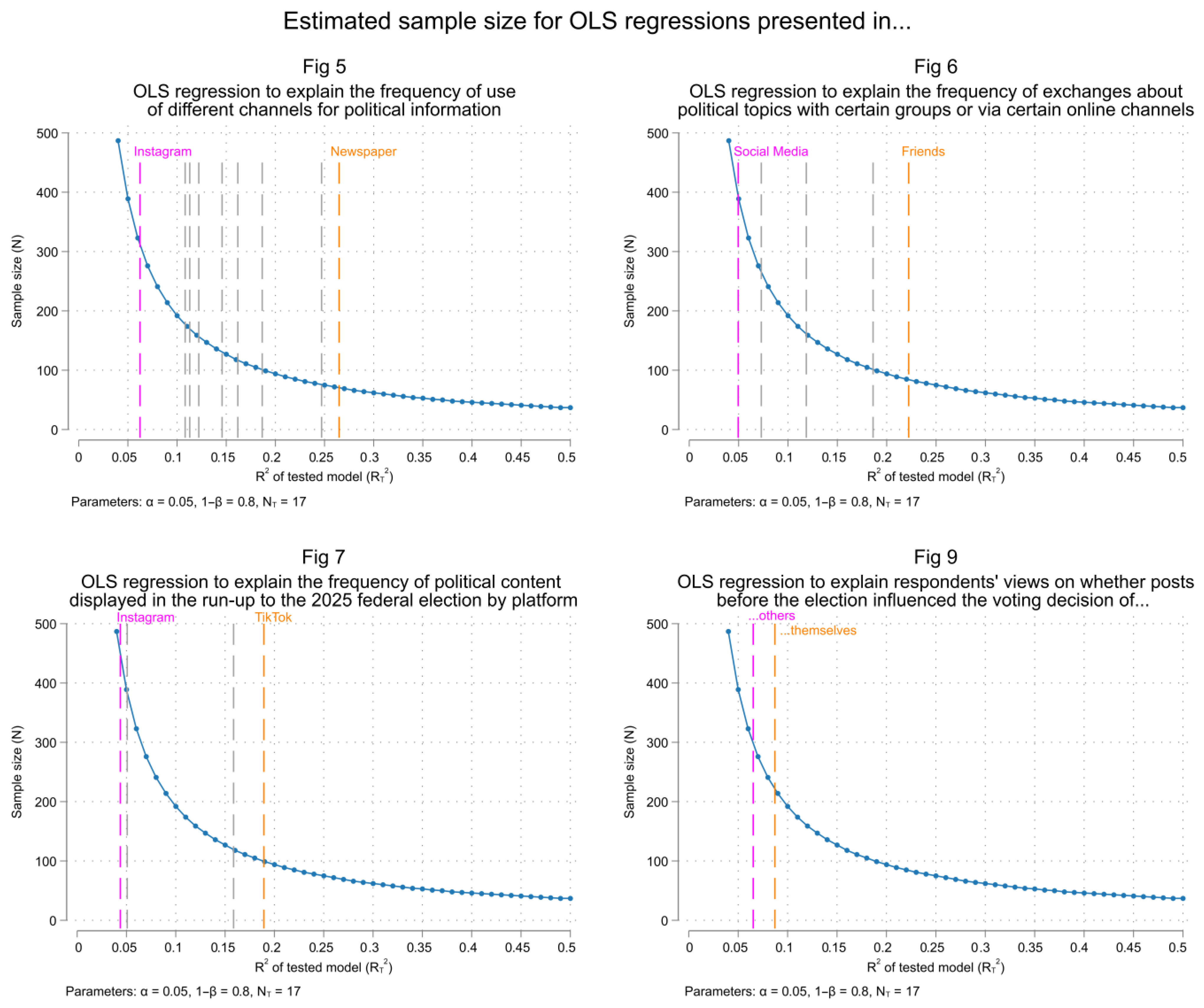

When interpreting the results, several limitations must be considered. Firstly, it is a relatively small and non-random sample, in which care was nevertheless taken to ensure that people from different educational backgrounds were included. Sample size calculations based on a statistical power of 80% nevertheless show that the samples used in the OLS regression models are sufficiently large (

Appendix A,

Figure A4). The regional focus of the analysis on respondents from southern Germany also makes it possible to control for other variables that moderate the relationship between the use of social media and voting decisions, but this also makes it impossible to transfer the results to the group of all young people in Germany. At this point, it would be interesting for future studies either to use representative samples according to region, educational background, and income situation, or to specifically look for respondents in regions with particularly conspicuous voting patterns (e.g., East German Saxon Switzerland, which strongly supports the AfD, versus the liberal-left academic city of Münster in western Germany).

Secondly, the survey was conducted up to 2 months after the federal election, which can lead to distortions in response behavior—in particular, the questions about the online contributions seen before the election are certainly subject to a certain loss of memory. For this reason, when analyzing the effects on the voting decision, we also use the comparatively easy-to-answer question about which platform was used to display a lot/less political content in the run-up to the election, and not more specific questions about which parties/politicians were particularly present on which platform. Although the latter would be very interesting, it is not feasible with a post-election survey, in which respondents are unlikely to remember the political content viewed for just a few seconds in the weeks/months before the election. To determine how the situation regarding digital campaigning for young voters, as we have outlined for the 2025 federal election, will develop in the future—for example, whether individual parties will focus even more strongly on certain online channels and how the electorate will react to this—can only be clarified through multiple repeated cross-sectional analyses and, in the best case, panel studies.

A third limitation of this study is its very narrow understanding of ‘digital campaigning strategies’, only focusing on the channels young voters use to inform themselves about politics and the type of approach parties use to reach young voters (direct or indirect via influencers). Clearly, the term digital campaigning strategies also includes the questions of which topics are brought forward, how specific political questions are framed, and which psychological persuasion methods are being used. While the broad and exploratory approach of this article does not allow for an examination of these aspects, our results complement studies that focus on factors such as the personalization and emotionalization of campaigns on social media (

Geise et al. 2025), political or conflict framing in online advertisement (

Stier 2016;

van der Goot et al. 2024), or the question whether parties emphasize owned or rival issues in their digital campaigning (

Thiele and Seliger 2025).

Finally, we simply took the political content that young voters saw online as a basis for asking whether the presentation of certain content was related to certain voting intentions. There are two things to note here. First, on platforms such as TikTok or Instagram in particular, algorithms decide largely which content is presented to users. Recent studies show that emotionally charged, out-group-hostile, and conflict-intense content are particularly amplified on social media (

Milli et al. 2025). An analysis of the mechanisms of this algorithmic content allocation is therefore central to better assessing the starting point of our analysis. The algorithm might also hide the sender of the content, which is a problem when asking our participants who these senders are. Nevertheless, the relatively coarse distinction between parties, private individuals, influencers, and popular party members that we apply here should make it possible for participants to name the sender. Secondly, the correlation we have identified between certain political content presented to young voters (e.g., The Left is strong on TikTok) and voting intentions can be interpreted causally in both directions. On the one hand, it is possible that a person who already has a firmly established political worldview is only presented with content from certain parties because of this ideological position. On the other hand, it is also possible that a person who is not yet so politically committed is increasingly drawn in a certain political direction because of certain digital content, thus solidifying their voting intention in a certain direction. Potentially, both effects could also reinforce each other, making it extremely difficult to identify cause and effect, even with panel data. Yet, what our analysis shows is that there exists a clear correlation between the frequency with which young persons view political content on different online channels and their voting decision.

Despite these limitations, our exploratory results undoubtedly contribute to a broader understanding of the forms and impact of an increasingly digital election campaign and can serve as a starting point for further research. The consideration of the impact of political content at the individual level deserves additional attention, as there are clear differences in the usage behavior but also in the display of political content via different digital channels among young voters. On the one hand, further empirical research that focuses on the demand side of political communication can help to demystify presumably superior populist actors in social media and, on the other hand, contribute to increasing the effectiveness of political campaigns.