Abstract

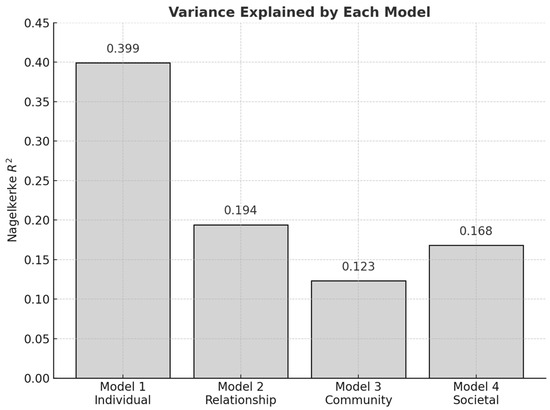

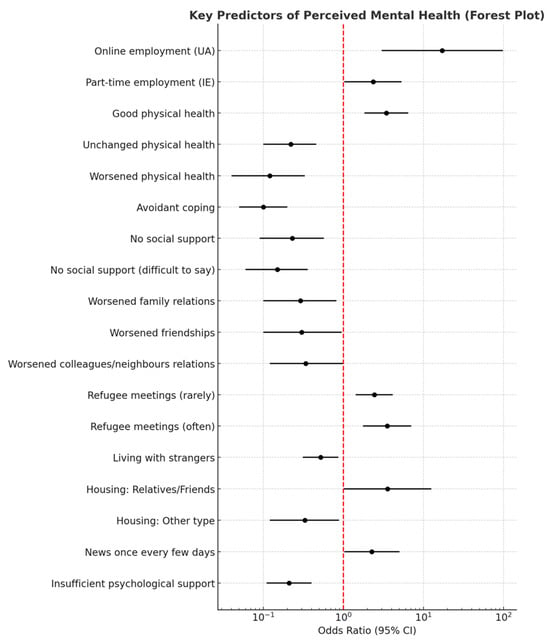

This study examines the perceived mental health of Ukrainian female forced migrants in Ireland through the lens of the socio-ecological model (SEM). Using binomial logistic regression on a 2023 online survey dataset (N = 656), it explores multi-level predictors across individual, relationship, community, and societal domains. Results indicate that individual-level factors explain the largest proportion of variance in perceived mental health (Nagelkerke R2 = 0.399). Employment status, self-rated physical health, and coping strategies were key determinants: part-time employment and good physical health were associated with higher odds of good perceived mental health. In contrast, avoidant coping and worsening health were associated with poorer outcomes. Relationship-level factors (R2 = 0.194) also contributed significantly; lack of social support and deteriorating family or friendship ties were linked to poorer mental health, whereas participation in refugee meetings was strongly protective. Community-level factors (R2 = 0.123) revealed that unstable housing, living with strangers, and declining neighbourhood relationships were associated with reduced mental well-being. At the societal level (R2 = 0.168), insufficient access to psychological support and excessive exposure to Ukrainian news were associated with poorer outcomes, while moderate news engagement was protective. The findings highlight the multifaceted nature of refugees’ perceived mental health, emphasising the interdependence of personal resilience, social connectedness, and systemic support.

1. Introduction

Migration research differentiates between voluntary and forced migration, with forced migration often involving higher levels of trauma exposure and more complex psychosocial needs (Bakewell 2021). The war in Ukraine has caused unprecedented displacement, affecting millions of lives. Ukrainian forced migrants occupy a unique position granted Temporary Protection status under the EU Council Directive 2001/55/EC (Council of the European Union 2001) within this spectrum: while they benefit from relatively open legal pathways in the EU, the sudden and violent nature of their displacement, combined with ongoing war, presents significant mental health risks.

Ireland has welcomed a significant number of displaced persons from Ukraine relative to its population. As of June 2025, there were 80,031 beneficiaries of temporary protection (BTPs); of these, 46% were women aged 20 years and older, 26% were men, and 29% were minors, highlighting a predominantly female and child profile (Central Statistics Office 2025b). Similar demographic trends are observed across the European Union: by mid-2025, adult women accounted for approximately 45% of all BTPs, and minors accounted for approximately 31% (Eurostat 2025).

At the beginning of 2025, 26,474 BTPs were employed, and 48,568 arrivals had engaged with Intreo Public Employment Services’ employment support events. Just over half reported that limited English proficiency was hindering their job search. Education levels were notably high: of 31,156 individuals with a recorded highest qualification, 60% held a university degree. Taken together, the data depict a highly educated, professionally experienced cohort whose primary barrier to labour market entry is linguistic rather than skills-based (Central Statistics Office 2025a).

Ukrainian arrivals are entitled to free public healthcare and access to public education for children. However, in practice, systemic challenges remain, including shortages of suitable housing, long waiting times for public healthcare, and limited mental health infrastructure tailored to migrants’ needs.

In Ireland, BTPs can access the public health system operated by the Health Service Executive, and some, depending on age and health status, are eligible for medical cards (free patient access to health services). Targeted initiatives include resources in Ukrainian and psychosocial support provided by the HSE and the Irish Red Cross (Health Service Executive 2024; Irish Red Cross 2024a, 2024b).

However, policy changes from March 2024, such as reducing weekly allowances for those in state-provided accommodation and introducing a 90-day limit for new arrivals, have made conditions more restrictive. From 10 November 2025, the State further tightened the arrangement by limiting newly arriving BTPs to just 30 days in state-provided accommodation before they must secure alternative housing. Civil society organisations have warned that these changes increase the risks of poverty, housing insecurity, and exploitation, especially for women.

Public attitudes towards refugees and migrants in Ireland remain mixed. Research by the Economic and Social Research Institute (ESRI) indicates that while there is broad solidarity with those displaced by the war in Ukraine, concerns persist regarding the perceived pressure on housing, healthcare, and education services (ESRI 2025a). Attitudes are not uniform across society: people living in disadvantaged communities and in areas where migrant populations have recently increased tend to express more negative views (ESRI 2025b). The studies emphasise that these perceptions are shaped less by direct competition for resources at the local level than by national narratives of scarcity and service strain. Such dynamics have implications for experiences of discrimination, social cohesion, and belonging, which, in turn, influence mental health outcomes for refugee populations.

Across Europe, Ukrainian refugees report increased symptoms of depression, anxiety, and psychological distress, consistent with the broader refugee literature (Buchcik et al. 2023). Mental health services in Ireland, already under pressure before 2022, face additional difficulties due to rising demand from forced migrants. O’Connor and colleagues’ research emphasises that Ireland’s mental health system entered the COVID-19 pandemic with significant pre-existing structural weaknesses (O’Connor et al. 2021). Studies on refugees have highlighted cultural mismatches between service provision and migrants’ expectations, language barriers, and logistical issues such as transportation and waiting times. For Ukrainian women, these challenges intersect with childcare responsibilities, economic and housing insecurity, and language barriers, which further restrict access to psychosocial support. Despite these obstacles, many Ukrainian female forced migrants demonstrate remarkable resilience by engaging in community building, cultural adaptation, language learning, caring for children and the elderly, and maintaining informal peer support networks, particularly through social media.

From a legal perspective, the European Union Temporary Protection Directive has been extended until 4 March 2027, with formal procedures still in progress (Council of the European Union 2025). This guarantees continued residence rights and access to services but also prolongs a “temporary” status with uncertain prospects, which may increase psychological stress among displaced women. Ireland’s reception of Ukrainian migrants under the Temporary Protection Directive signifies an unprecedented shift in migration policy.

The socio-ecological model (SEM), originally developed by Bronfenbrenner (1979), offers a comprehensive framework for analysing various levels of influence on health. According to SEM, health outcomes are affected not only by individual characteristics but also by interpersonal, community, and societal factors. In refugee research, SEM is increasingly used to conceptualise the multiple layers of determinants of mental health, illustrating how complex interactions between personal, relational, and structural conditions—including pre-, peri-, and post-migration stressors such as social isolation, unemployment, poverty, discrimination, family separation, legal uncertainty, and unsafe living conditions—impact mental health outcomes (Miller and Rasmussen 2017).

Applying the socio-ecological model to forced migrant populations marks a key methodological shift by moving beyond individual explanations of refugee health and emphasizing the influence of social determinants, structural constraints, and policy contexts (Carmona et al. 2023). Refugee women experience complex health challenges shaped by trauma, migration experiences, and sociocultural displacement. Using the social-ecological model, Hawkins et al. (2021) found that individual factors such as language barriers and low health literacy intersect with interpersonal, organizational, and community influences to impact health outcomes. Social support improves access to care and mental well-being but is often limited by isolation and communication difficulties. The authors emphasize that a culturally safe, multilevel approach—integrating mental health screening, social support, and interorganizational collaboration—is essential to promote health equity among refugee women.

Previous research on refugee and forced migrant mental health has predominantly focused on either individual-level risk factors (trauma exposure, coping mechanisms, and pre-migration stressors) or structural determinants (housing, healthcare access, and socio-economic conditions) (Bogic et al. 2015; Hawkins et al. 2021). However, few studies have examined multiple ecological levels simultaneously to determine their relative contribution to perceived mental health outcomes. These limits understanding of how individual vulnerabilities interact with broader systemic conditions to shape psychosocial well-being among displaced populations.

Forced migration also affects men and women differently. Women often experience distinct gendered vulnerabilities, including heightened exposure to gender-based violence, exploitation, and insecurity during both displacement and resettlement (Tadesse et al. 2024). These risks are compounded by gendered social roles and caregiving responsibilities, which may exacerbate stress and constrain opportunities for integration.

In the Irish context, recent scholarship has begun to address migrant health more broadly, yet notable gaps remain. An updated scoping review of migrant health research in Ireland found that despite growth in the field, studies specifically examining the mental health of forced migrants and refugees remain limited, with very few employing multi-level or socio-ecological frameworks (Cronin et al. 2024). Ukrainian women, in particular, frequently arrive with dependent children and/or elderly relatives, bearing a dual burden of caregiving and adaptation to complex integration systems. Despite these intersecting pressures, empirical research exploring their combined effects on mental health remains scarce.

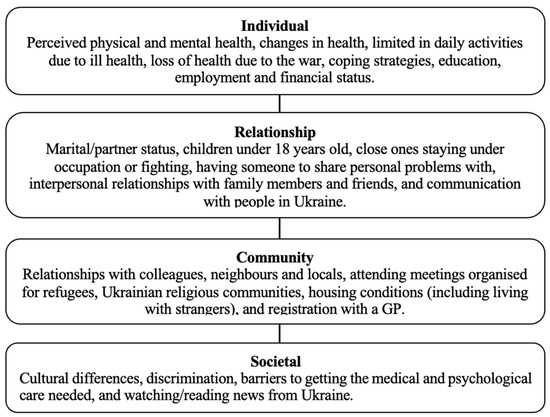

Although the socio-ecological model (SEM) has gained prominence in public health and migration research for capturing multi-level determinants of well-being, its application to refugee mental health in Ireland is still underdeveloped. This represents a critical research gap at the intersection of gender, displacement, and mental health, underscoring the need for integrative, context-specific, and gender-sensitive approaches within the Irish setting. This study explores the factors influencing the perceived mental health of Ukrainian displaced women living in Ireland, employing a socio-ecological framework and considering predictors across four interconnected domains, as visually summarised in Figure 1. This figure illustrates the multilayered influences on refugee mental well-being.

Figure 1.

Socio-ecological model of perceived mental health of Ukrainian forced migrant women.

Understanding how refugees perceive their mental health within the host country environment and identifying the most influential factors across ecological levels are essential for guiding policy and intervention strategies. By estimating logistic regression models for each ecological level separately, the study aims to identify the factors most strongly associated with perceived mental health and to assess the relative importance of each level within the socio-ecological framework. The findings will add to the expanding body of literature emphasising the importance of multi-level determinants of forced migrant mental well-being. They will provide evidence to support policies and interventions that promote both individual resilience and structural integration.

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Online Survey

The data were collected through an online survey conducted in 2023 among Ukrainian female forced migrants living in Ireland. The inclusion criteria included being a female aged 18 or older and having come to the Republic of Ireland due to the war (from 24th February). The survey included questions about demographic details, self-assessed physical health and its changes during the war, self-assessed mental health, coping strategies, having loved ones left in Ukraine, family, friends, and community relationships, as well as interpersonal networks, housing situations, access to medical services, psychological support, cultural differences, and humanitarian support. The survey was designed in Ukrainian. The survey was disseminated via non-governmental organisations that assist refugees and social media groups where Ukrainian refugees participated (Facebook, Telegram, and Viber). Participation was voluntary and anonymous, with informed consent obtained from all respondents before data collection.

The study concentrated on women, given that around 80% of displaced Ukrainians who arrived in Ireland were female and often accompanied by children. This gender imbalance primarily reflects wartime conscription measures and legal restrictions preventing men of conscription age from departing Ukraine.

2.2. Coping Strategies Measure

The study used the BRIEF-COPE instrument, which contains 28 items that measure coping strategies across 14 subscales: active coping, planning, instrumental support, positive reframing, acceptance, emotional support, humour, religion, venting, self-distraction, denial, behavioural disengagement, substance use, and self-blame. Responses were scored on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = “I have not been doing this at all” to 4 = “I have been doing this a lot”), with 2.5 as the scale’s midpoint. For analysis, coping was grouped into three main categories: problem-focused coping (directly addressing stressors), emotion-focused coping (managing emotions and thoughts related to stress), and avoidant coping (disengaging from the stressor or its emotional impact) (Carver et al. 1989; Huijts et al. 2012). The Ukrainian version of the Brief-COPE has been previously validated and shown to be reliable. The overall internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) was 0.81, while reliability for the three dimensions ranged from 0.65 to 0.77 (Mazhak et al. 2024).

3. Results

Jamovi statistical software (version 2.4.12.0) was employed to conduct descriptive and logistic regression analyses (The Jamovi project 2023; R Core Team 2022; Fox and Weisberg 2020).

3.1. Demographic Characteristics of the Sample

Descriptive statistics for the sample variables (N = 656) included in the regression analysis are shown in Supplementary File S1. The sample mainly consists of adults aged 30–40 (41.0%) and over 40 (40.5%), with a smaller proportion under 30 (18.6%), and an average age of 38.6 years. Educational attainment is generally high, with 78.4% of women holding at least a university degree. Before the war, most respondents had relatively stable financial situations, with 63.6% able to meet their basic needs, including food, clothing, and some savings, and 15.5% able to afford expensive purchases. However, their current economic status has worsened, with nearly half reporting that they are somewhat (23.3%) or significantly worse off (25.2%) than they were before. Employment in Ireland remains limited, with 18.8% working full-time, 15.7% part-time, and 60.7% unemployed. Overall, the profile indicates a highly educated group, with limited labour market participation and declining financial stability since displacement.

Family responsibilities are significant, with 59.6% of people having children under the age of 18. The war continues to affect their families directly: 63.1% say a close relative lives near the frontline or is under shelling, and 27.3% have close ones fighting on the frontline. Despite these pressures, social support remains relatively resilient, with 64.8% reporting they have someone to share personal problems with, and relationships with family and friends generally stay steady. Information consumption and connections to Ukraine remain strong: 57.8% follow Ukrainian news several times a day, and 24.1% communicate with contacts in Ukraine multiple times daily. In terms of coping strategies, respondents scored highest on problem-focused strategies (M = 2.93), followed by emotion-focused (M = 2.41) and avoidant strategies (M = 2.15). This indicates a tendency towards proactive coping despite considerable challenges in health, housing, and social integration.

Patterns of social participation varied, with 43.9% attending refugee meetings rarely and 12.5% attending often, while more than a third (35.4%) did not participate at all. Housing conditions were dominated by refugee housing (49.8%) and the Accommodation for Protection Applicants (APA) programme (27.4%), with one-third (33.2%) living with strangers. Only 12.7% reported cultural differences, and 9.9% reported experiencing discrimination as refugees in the host country.

Regarding the health assessment, more than half (56.4%) of women self-reported poor physical health, with 27.9% indicating a deterioration in the past month. A notable 16.8% reported the need for ongoing medical supervision, and 72.6% registered with a family doctor, through whom they access the Irish healthcare system. Overall, 17.1% of women rated their mental well-being positively, while 82.9% described their mental health as fair or poor.

The data reveal significant barriers in access to medical and psychological care, with the most reported obstacles being language difficulties (48.8%), long waiting times (44.8%), and challenges navigating the healthcare system (37.8%). Financial and structural barriers were also present, including high costs (29.4%), lack of specialized doctors (25.6%), and limited insurance coverage (20.9%). In terms of humanitarian support, most respondents reported sufficient financial aid (76.6%) and housing (69.7%), while access to food (63.8%) and information about job opportunities (51.6%) was more constrained. However, medical and psychological needs remain particularly underserved: nearly half reported insufficient access to necessary medical aid (47.3%) and psychological support (45.6%), while dental care showed the greatest gap, with 62.8% stating it was not adequately available. These findings highlight that despite relative stability in basic resources, healthcare access, especially psychological and dental services, remains critically insufficient. The descriptive statistics of the study sample are provided in Supplementary File S1.

3.2. Statistical Analysis

The primary outcome of interest was self-reported mental health status. Responses were dichotomised to show whether participants reported experiencing mental health issues or no such issues. This binary outcome variable allowed the estimation of odds ratios in logistic regression analyses. Binomial logistic regression analysis was used to examine predictors of mental health status across four levels of the socio-ecological model. The models were specified as follows: Model 1: Individual-level factors; Model 2: Relationship-level factors; Model 3: Community-level factors; and Model 4: Societal-level factors. Model performance was assessed using the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), Nagelkerke’s R2, and classification accuracy. Predictors were retained in the models based on statistical significance (p < 0.05) and theoretical relevance grounded in the socio-ecological framework. The models demonstrated varying levels of explanatory power, with Nagelkerke’s R2 values ranging from 0.123 to 0.399. Figure 2 presents the variance explained (Nagelkerke R2) by each level of the socio-ecological model.

Figure 2.

Variance explained (Nagelkerke R2) by each model.

Statistically significant predictors of perceived mental health across all models are shown in Table 1. All predictors for each model are listed in Supplementary File S2.

Table 1.

Statistically significant predictors of perceived mental health across all models.

3.3. Individual-Level Factors

The individual-level logistic regression Model 1 demonstrated the strongest explanatory power among the four models, with an AIC of 488 and a Nagelkerke’s R2 of 0.399, indicating a good fit. Several predictors in this model were statistically significant and notably associated with mental health outcomes. Age and education level, pre-war financial situation, current economic status, having lost health due to the war, limitations in daily activities, number of chronic diseases, and intention to return to Ukraine were not significantly related to mental health. However, employment status was significantly associated with mental health (Table 1). Using respondents employed part-time in Ireland as the reference category, those working full-time in Ireland had significantly lower odds of the perceived mental health (OR = 0.43, p = 0.042). In contrast, respondents who were working remotely for an employer in Ukraine had substantially better perceived mental health compared with part-time workers in Ireland (OR = 7.33, p = 0.024). However, this estimate should be interpreted with caution because only nine women in the sample reported remote employment in Ukraine, and their comparatively better mental health may reflect the continuity and perceived stability of maintaining pre-migration employment rather than an actual effect of remote work itself. Participants who were not working also had a lower perceived mental health status than the reference group (OR = 0.47, p = 0.031).

Furthermore, self-reported physical health was another significant factor: participants reporting good perceived physical health had substantially higher odds of reporting good mental health than those with poor perceived physical health (OR = 3.45, p < 0.001). Compared with those whose physical health got better, those whose health stayed the same (OR = 0.22, p < 0.001) or got worse (OR = 0.12, p < 0.001) had markedly lower odds of better perceived mental health. Unexpectedly, respondents who reported “no” need for continuous medical supervision had lower odds of better-perceived mental health than those who reported such a need (OR = 0.39, p < 0.05), possibly due to an unmeasured mediator.

Coping strategies also played a crucial role; while problem- and emotion-focused coping were not significantly related to outcomes, avoidant coping was strongly associated with a lower likelihood of reporting good mental health (OR = 0.10, p < 0.001).

Collectively, these findings highlight the critical importance of personal coping strategies, employment type, and overall physical health in shaping mental health outcomes among Ukrainian displaced women. Individual-level factors had the most significant impact on perceived mental health, as indicated by the highest R2 value in the model. Working part-time in Ireland, maintaining remote employment in Ukraine, and reporting good physical health were all strongly associated with better perceived mental health. Conversely, avoidant coping strategies were closely linked to poorer perceived mental health, and any decline in physical health over the past month, whether unchanged (compared to improvement) or deteriorating, was also associated with worse perceived mental health.

3.4. Relationship-Level Factors

The logistic regression Model 2, which assessed relationship-level predictors of mental health, demonstrated a modest fit, with an AIC of 563 and a Nagelkerke’s R2 of 0.194. Although its explanatory power was lower than that of the individual-level model, several relationship-based variables were significantly associated with perceived mental health. Marital status was not significantly related to mental health; however, not having children under 18 was marginally associated with lower odds of perceiving good mental health (OR = 0.59, p < 0.05), suggesting that caregiving roles and stronger social networks linked to motherhood may offer emotional support and structure that buffer psychological distress.

Social support proved to be a strong predictor of relationships. Compared to participants who had someone to confide in, those without such support (OR = 0.23, p < 0.01) and those who answered, “difficult to say” (OR = 0.15, p < 0.001) had considerably lower odds of good mental health. The quality of relationships was also crucial, as deteriorating relationships with family members (OR = 0.29, p < 0.05) and friends (OR = 0.30, p < 0.05) were significantly associated with poorer perceived mental health.

Communication patterns also mattered. Communicating with people in Ukraine once every few days was associated with higher odds of perceived good mental health compared to having multiple contacts daily (OR = 2.12, p < 0.05). All other communication frequencies—once per day, once per week, once per several weeks, having no possibility, or having no desire to communicate—were not significantly associated with perceived mental health. This pattern suggests that moderate communication may offer emotional connection and support without the heightened stress that can accompany frequent updates about the war in Ukraine.

Therefore, within the relationship domain, maintaining regular but not excessive communication with relatives and friends in Ukraine (once every few days) was linked to better mental health, suggesting that balanced contact may be protective. The lack of close confidants, whether due to having no one to share personal problems with or uncertainty about such support, was strongly associated with poorer perceived mental health. Additionally, deterioration in relationships with family members or friends predicted poorer perceived mental health, reflecting the vital role of interpersonal quality and stability in mental well-being.

3.5. Community-Level Factors

The community-level logistic regression Model 3 showed the lowest explanatory power among the four domains, with an AIC of 588 and a Nagelkerke’s R2 of 0.123. Despite the modest model fit, several community-related variables were found to be significantly associated with mental health outcomes. The type of housing is related to mental health outcomes, as people living with relatives or friends are significantly more likely to report good mental health compared to those in refugee-specific accommodation (OR = 3.56, p = 0.048). Conversely, individuals living with strangers have considerably lower chances of perceived good mental health (OR = 0.52, p < 0.05). These findings indicate that moving into stable and supportive housing environments fosters a sense of normality and psychological stability, while unstable housing can negatively impact mental well-being.

Moreover, social interactions within the community proved vital. Respondents who reported that their relationships with neighbours and colleagues had deteriorated had significantly lower odds of perceived good mental health than those who reported improvements (OR = 0.34, p = 0.047). This finding illustrates how declining local social ties can increase distress and weaken psychological resilience among forcibly displaced females.

Additionally, participating in community activities, especially refugee meetings, emerged as a strong protective factor. Attending such meetings was associated with higher odds of perceived good mental health, both when participation was reported rarely (OR = 2.43, p < 0.001) and when it was reported frequently (OR = 3.52, p < 0.001). This underscores the importance of organised community gatherings in providing opportunities for social support, information exchange, and collective coping.

In summary, the findings from Model 3 illustrate the dual role of community-level conditions. Supportive housing, positive neighbourly relationships, and participation in refugee meetings served as protective factors. Conversely, living in unstable housing, sharing accommodation with strangers, and declining relationships with neighbours and colleagues posed risks to mental well-being. These outcomes emphasise that the community environment can either promote resilience or increase vulnerability, depending on the quality and stability of available resources and relationships.

3.6. Societal-Level Factors

The societal-level Model 4 showed a moderate fit, with an AIC of 517 and a Nagelkerke’s R2 of 0.168. Although the explanatory power was lower than that of the individual-level model, several societal-level predictors demonstrated significant associations with perceived mental health outcomes among Ukrainian displaced women.

Perceived cultural differences and experiences of discrimination did not show significant relationships with perceived mental health. Similarly, most barriers to healthcare access, such as difficulties navigating the healthcare system, insufficient English proficiency, waiting times, costs, and a lack of doctors, were not significantly associated with perceived mental health. However, one structural barrier emerged as a strong predictor, as respondents who reported insufficient access to psychological support had markedly lower odds of perceived good mental health (OR = 0.21, p < 0.001). These findings emphasise the central role of service accessibility as a key structural determinant of psychological well-being.

Moreover, Ukrainian news consumption showed a significant association with perceived mental health only for one category. Compared with respondents who checked the news several times per day, those who followed the news once every several days had higher odds of reporting good mental health (OR = 2.27, p = 0.043). All other news consumption frequencies were not statistically significant. This suggests that moderate exposure to news may help individuals stay informed without the emotional strain associated with constant monitoring of the war.

To sum up, Model 4 highlights the role of structural conditions in shaping mental health among Ukrainian displaced women. Most societal-level factors were not significant, but limited access to psychological support was strongly associated with reduced odds of good mental health, making it the key negative predictor. Moderate news consumption (once every several days) was associated with better perceived mental health compared with persistent monitoring. Overall, the findings emphasise that access to psychological care and balanced exposure to information are crucial structural determinants of psychological well-being.

Across the four models, predictors of perceived mental health appeared at multiple levels of the socio-ecological model. Figure 3 presents odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals for significant predictors across the four models. Dots indicate OR values, horizontal lines show 95% CIs, and the red dashed line marks the null value (OR = 1).

Figure 3.

Forest plot of key predictors of perceived mental health.

Perceived mental health among Ukrainian displaced women was shaped by factors across all socio-ecological levels. Individual factors were most influential, with good physical health, employment, and non-avoidant coping linked to better perceived mental health. Relationship-level support, stable community ties, and participation in refugee activities are also associated with mental health. At the societal level, limited access to psychological support was the strongest negative predictor. Overall, well-being depended on a combination of personal, relational, community, and structural conditions.

4. Discussion

The current study examined factors influencing perceived mental health among Ukrainian female refugees using the socio-ecological model, which offers a comprehensive, multi-level framework for understanding mental health outcomes among forced migrants by analysing connected levels of influence: individual factors, interpersonal relationships and social support, community contexts, and broader societal levels. The findings emphasise the multi-layered nature of mental health among Ukrainian women in displaced populations.

4.1. Individual Level

The prevalence of individual-level factors reflects a particular vulnerability window: these women are in displacement, managing recent trauma and ongoing war anxiety while bearing acute caregiving responsibilities. At the individual level, exposure to pre- and peri-migration trauma, war-related loss, and ongoing concern for family members left behind in Ukraine or actively fighting in the war are key predictors of mental distress, depression, anxiety, and PTSD among displaced Ukrainian forced migrants (Ellis et al. 2024; Mazhak et al. 2024; Mazhak and Sudyn 2025; Mykhaylyshyn et al. 2024).

Employment status emerged as a significant determinant of perceived mental health among Ukrainian female refugees. Consistent with previous literature emphasizing the protective role of employment, having a job may enhance well-being by providing financial stability, daily structure, and a sense of purpose (Modini et al. 2016). However, the current findings suggest that the quality and nature of employment may be more influential than employment status alone.

Women engaged in full-time work in Ireland reported significantly lower odds of good perceived mental health than those working part-time, potentially reflecting strain from high work demands or challenges in achieving work–life balance. This finding highlights the importance of flexibility and autonomy in work arrangements, particularly for mothers balancing caregiving responsibilities with integration demands. Flexible or remote positions help alleviate stress associated with demanding roles. Conversely, participants who maintained remote employment in Ukraine had substantially higher odds of better-perceived mental health. This association should be interpreted cautiously, as only nine women in the sample reported remote employment in Ukraine. Their comparatively better mental health may reflect the stability and continuity of maintaining pre-migration employment rather than a direct causal effect of remote work itself.

In contrast, participants who were not employed demonstrated lower perceived mental health compared with part-time workers in Ireland. This aligns with prior evidence indicating that unemployment can negatively affect psychological well-being by reducing social engagement, sense of purpose, and economic security (Wanberg 2012). These findings suggest that employment flexibility and continuity may play a critical role in supporting migrant women’s mental health. Additionally, language proficiency likely moderates these effects, influencing access to employment, help-seeking behaviours, navigation of the host country’s healthcare system, and self-efficacy (Davitian et al. 2024; Těšinová et al. 2024). Overall, the pattern highlights the potential importance of stable, locally based employment for supporting the mental health of displaced Ukrainian women in Ireland.

Consistent with previous research (Bogic et al. 2015)., these findings underscore the bidirectional and interdependent nature of physical and mental health among displaced populations. Individuals experiencing improvements in their physical health may perceive themselves as more capable of managing daily stressors, adapting to new environments, and fulfilling familial or social responsibilities, thereby reinforcing psychological well-being. Conversely, declining physical health may contribute to feelings of helplessness or loss of control, both of which are established predictors of poor mental health outcomes among refugees (Bogic et al. 2015).

The unexpected association between the absence of a need for continuous medical supervision and poorer perceived mental health warrants further investigation. One possible explanation is that participants who acknowledge ongoing medical needs may also be more engaged with healthcare providers, which could foster a sense of support and reassurance. This finding highlights the complex interplay between healthcare engagement, perceived health status, and psychological adaptation in post-migration contexts.

Consistent with other research, the coping style proved to be crucial. This study pattern reinforces the well-documented association between avoidant coping and adverse psychological outcomes among displaced or trauma-affected populations. Avoidance may offer short-term relief by reducing exposure to stressors; however, over time, it tends to exacerbate distress by hindering emotional processing and effective problem-solving (Dawson and Golijani-Moghaddam 2020). It has been shown that ineffective coping mechanisms put migrants at risk for mental illnesses such as depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Conversely, effective coping may improve refugees’ health (Huijts et al. 2012). In contrast, individuals who engage in effective coping often demonstrate greater resilience and more favourable mental health outcomes.

Overall, these results show that personal coping styles, job type, and physical health are key to mental well-being among displaced Ukrainian women. Individual factors mattered most: part-time work in Ireland and good physical health correlated with better mental health, while avoidant coping and recent declines in health were linked to poorer outcomes.

4.2. Relationship Level

At the relationship level, the findings emphasise that relational stability and balanced communication are vital to sustaining mental well-being among displaced Ukrainian women. The protective effects of supportive relationships are consistent with the broader literature, which demonstrates that social connectedness fosters emotional regulation, buffers against stress, and enhances resilience during displacement (Sim et al. 2019; Slewa-Younan et al. 2015). Conversely, the detrimental impact of relational deterioration underscores how interpersonal conflict, family separation, social isolation, or loss of trust can erode coping resources and amplify vulnerability to anxiety and depression (Nickerson et al. 2010).

In the study, maintaining moderate, stable contact with relatives and friends in Ukraine appears to offer continuity and emotional reassurance, supporting identity and belonging while avoiding the psychological overload associated with constant exposure to distressing news. Excessive communication, particularly multiple daily contacts, may inadvertently sustain emotional fatigue, thereby diminishing perceived mental health (Anjum 2023).

In the relationship level, balanced communication with relatives and friends in Ukraine was linked to better mental health, while lack of close support or worsening relationships predicted poorer well-being.

4.3. Community Level

At the community level, the findings illustrate that community environments can either enhance resilience or intensify vulnerability, depending on the stability, safety, and social cohesion they provide. The present results reinforce longstanding evidence that housing quality is one of the strongest community-level determinants of refugee mental health. Studies across the EU have consistently shown that overcrowded, unstable, or institutional accommodation arrangements undermine psychological well-being. In contrast, private, family-based, or community-oriented housing promotes a sense of autonomy, predictability, and safety (Spira et al. 2025). Evidence from large-scale studies in Germany and other EU contexts indicates that refugees residing in collective or shared accommodations, often among unfamiliar co-residents, experience higher psychological distress and lower life satisfaction compared to those living in private or family-based housing (Walther et al. 2020; Hajak et al. 2021). Conversely, stable living arrangements that foster social support, such as cohabiting with relatives or close friends, tend to enhance perceived safety, belonging, and emotional resilience (Schilz et al. 2023). Similar findings were observed in our study: participants living with relatives or friends were more likely to report good perceived mental health than those residing in refugee-specific accommodation. In contrast, individuals living with strangers were less likely to perceive their mental health positively, suggesting that familiar and supportive living arrangements may serve as a protective factor.

Beyond housing, local social ties and neighbourhood relations played a pivotal role in shaping mental health outcomes among displaced Ukrainian women. Participants who experienced a decline in their relationships with neighbours or colleagues reported poorer perceived mental health, consistent with broader evidence that weak local social networks contribute to social isolation and hinder successful adaptation (Albers et al. 2021). In contrast, active participation in community-based initiatives and refugee meetings emerged as a strong protective factor. Such collective spaces foster social connection, shared meaning-making, and emotional resilience, in line with findings that sociability and communal engagement enhance psychological well-being among displaced groups (Olcese et al. 2024).

The results also highlight the importance of community-level support structures, including host-family schemes, diaspora networks, and civil-society programmes. Evidence from Ireland’s Red Cross Safe Homes initiative and international research demonstrates that structured and well-supported hosting arrangements provide both practical assistance and emotional stability, thereby reducing the psychological strain associated with housing insecurity (Fornaro et al. 2025; Mazhak et al. 2024). When effectively managed, these community mechanisms not only facilitate social integration but also mitigate distress by fostering a sense of belonging and relational trust.

Collectively, these findings underscore that social embeddedness at the community level, through stable neighbourhood ties, supportive housing arrangements, and opportunities for collective participation, is a crucial determinant of mental well-being during displacement.

4.4. Societal Level

At the societal level, entitlement to healthcare does not always lead to actual access. An Irish study of Ukrainian refugees found that language barriers, difficulties with appointments, long waiting times, transport issues, and limited engagement with GPs hindered referrals to mental health services (O’Reilly et al. 2025). Over half of respondents needed an interpreter, yet few received one, a quarter missed appointments due to transport problems, and most had not been asked about their mental health. Similar systemic barriers, such as a lack of information, long waiting times, and financial constraints, are reported across Europe (Kardas et al. 2025). Irish national policy frameworks emphasise intercultural responsiveness in mental health care. Sharing the Vision (2020–2030) outlines a stepped and integrated model of service delivery, and its 2025–2027 Implementation Plan reinforces these priorities, focusing on inclusive and culturally sensitive practices (Health Service Executive 2025). To improve access, the HSE also provides multilingual resources, including guides translated into Ukrainian (HSE). However, effective implementation relies on expanding professional interpretation services and ensuring affordability across primary and psychological care.

At the societal level, access to psychological support proved to be the most vital factor. Insufficient psychological support was strongly associated with poorer perceived mental health, while inadequate financial, food, or housing assistance was not a significant predictor. This highlights the growing understanding that providing culturally sensitive psychological and psychosocial services, through provider cultural competence, language alignment, and adaptation to refugees’ understanding of mental health, is crucial for refugee well-being (Satinsky et al. 2019). Research on Ukrainian refugees arriving in Ireland reveals particularly concerning mental health outcomes, with 75.4% of respondents reporting that mental health was not addressed during healthcare consultations, indicating substantial gaps in mental health screening and support systems (O’Reilly et al. 2025).

Beyond structural barriers in healthcare access, Ukrainian media consumption also plays a critical role in shaping psychological well-being. In line with the relationship-level results, moderate engagement with news and media was associated with better mental health, likely because it fosters awareness, connectedness, and a sense of agency in an uncertain context. However, frequent exposure has been consistently linked to heightened anxiety, hopelessness, and trauma reactivation (Liu and Liu 2020). For forcibly displaced Ukrainians, persistent consumption of war-related updates may prolong grief, intensify fears for relatives, and inhibit psychological recovery.

Therefore, access to psychological support emerged as the most critical determinant of well-being, balanced Ukrainian media engagement appears protective, whereas constant exposure to conflict-related content exacerbates distress. Together, these findings highlight that equitable access to psychological care and mindful information environments are essential for sustaining refugees’ mental health.

4.5. Limitations and Future Research

This study is cross-sectional, which limits the ability to make causal inferences. Future longitudinal research is necessary to examine how individual, relational, community, and societal factors interact over time. The reliance on online data collection may have led to the exclusion of women with lower levels of education, limited financial resources, or insufficient digital skills. In addition, it is also important to further examine how legal status of temporary protection may affect levels of stress and psychological well-being. Finally, qualitative research would enrich these findings by providing deeper insights into how refugees themselves understand and navigate the interplay of these determinants.

5. Conclusions

A complex interaction of personal, relational, and systemic factors influences mental health among Ukrainian forcibly displaced women. Targeted interventions should focus on reducing avoidant coping, supporting secure employment, and enhancing access to health services and community networks. Multilevel strategies are crucial for promoting psychological well-being.

This study used a socio-ecological framework to examine the factors influencing perceived mental health among refugees. The results indicated that individual factors, particularly perceived physical health, employment status, and coping strategies, contributed most to variations in perceived mental health. However, relationship factors such as social support and the quality of personal connections also played an important role. Community-level conditions, including housing arrangements, local social ties, and neighbourhood relations, as well as society-level resources—especially access to psychological support and Ukrainian news consumption habits—further influenced the outcomes.

The study has several implications for policy and practice. First, mental health programmes for refugees should not focus solely on trauma but also address ongoing social and structural conditions that influence mental well-being. Second, community-based interventions that promote social connectedness and participation may offer accessible, low-cost, and effective ways to improve mental health. Third, policies should prioritize access to psychological support alongside financial aid, as limited access to such services was the strongest societal-level predictor of poor mental health.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded from https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/socsci14120714/s1, Table S1: Descriptive statistics of Ukrainian female forced migrants in Ireland (N = 656); Table S2: Socio-Ecological Model & Perceived Mental Health.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.M. and D.S.; Methodology, I.M. and D.S.; Validation, I.M.; Formal analysis, I.M.; Investigation, I.M.; Resources, I.M.; Data curation, I.M. and D.S.; Writing—original draft, I.M.; Writing—review & editing, I.M. and D.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the European Union under the MSCA4Ukraine program, project ID: 101101923/AvH-ID: 1233386, awarded to I.M. Financial support was provided for the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland Ethics Committee (ID: 212639195, 25 September 2023) and followed the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

The study adhered to established ethical standards for research involving human participants. All participants provided electronic informed consent before taking part. Participation was voluntary, with no financial or material incentives. Data were collected anonymously, and no personally identifiable information was stored or analyzed.

Data Availability Statement

Data generated and analysed during this study are accessible from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Albers, Thomas, Silvia Ariccio, Laura A. Weiss, Federica Dessi, and Marino Bonaiuto. 2021. The role of place attachment in promoting refugees’ well being and resettlement: A literature review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18: 11021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjum, Gulnaz, Mudassar Aziz, and Hadar Khasrow Hamid. 2023. Life and mental health in limbo of the Ukraine war: How can helpers assist civilians, asylum seekers and refugees affected by the war? Frontiers in Psychology 14: 1129299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakewell, Oliver. 2021. Unsettling the boundaries between forced and voluntary migration. In Handbook on the Governance and Politics of Migration. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 124–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogic, Marija, Anthony Njoku, and Stefan Priebe. 2015. Long-term mental health of war-refugees: A systematic literature review. BMC International Health and Human Rights 15: 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bronfenbrenner, Urie. 1979. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Buchcik, Johanna, Viktoriia Kovach, and Adekunele Adedeji. 2023. Mental health outcomes and quality of life of Ukrainian refugees in Germany. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 21: 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carmona, Gloria, Kashmira Sawant, Reema Hamasha, Fernanda Lima Cross, Susan J. Woolford, Ayse G. Buyuktur, Sarah Burke Bailey, Zachary Rowe, Erica Marsh, Barbara Israel, and et al. 2023. Use of the socio-ecological model to explore trusted sources of COVID-19 information in Black and Latinx communities in Michigan. Journal of Communication in Healthcare 16: 389–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, Charles S., Michael F. Scheier, and Jagdish Kumari Weintraub. 1989. Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 56: 267–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Central Statistics Office. 2025a. Arrivals from Ukraine in Ireland: Series 15. CSO. Available online: https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/fp/p-aui/arrivalsfromukraineinirelandseries15/ (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Central Statistics Office. 2025b. Arrivals from Ukraine in Ireland Series 16. CSO. Available online: https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/fp/p-aui/arrivalsfromukraineinirelandseries16/ (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Council of the European Union. 2001. Council Directive 2001/55/EC of 20 July 2001 on minimum standards for giving temporary protection in the event of a mass influx of displaced persons and on measures promoting a balance of efforts between Member States in receiving such persons and bearing the consequences thereof. Official Journal of the European Communities L212: 12–23. [Google Scholar]

- Council of the European Union. 2025. EU Member States Agree to Extend Temporary Protection for Refugees from Ukraine. Press Release. Available online: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2025/06/13/eu-member-states-agree-to-extend-temporary-protection-for-refugees-from-ukraine/ (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Cronin, Anne, Ailish Hannigan, Nuha Ibrahim, Yuki Seidler, Blessing Olamide Owoeye, Wigdan Gasmalla, Tonya Moyles, and Anne MacFarlane. 2024. An updated scoping review of migrant health research in Ireland. BMC Public Health 24: 1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davitian, Karina, Peter Noack, Katharina Eckstein, Jutta Hübner, and Emadaldin Ahmadi. 2024. Barriers of Ukrainian refugees and migrants in accessing German healthcare. BMC Health Services Research 24: 1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, David L., and Nima Golijani-Moghaddam. 2020. COVID-19: Psychological flexibility, coping, mental health, and wellbeing in the UK during the pandemic. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science 17: 126–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Economic and Social Research Institute (ESRI). 2025a. Community Context Affects Attitudes Towards Immigration. ESRI. July 22. Available online: https://www.esri.ie/news/community-context-affects-attitudes-towards-immigration (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Economic and Social Research Institute (ESRI). 2025b. People in Disadvantaged Communities Have More Negative Attitudes Towards Immigration, ESRI Report Finds. The Irish Times. July 22. Available online: https://www.irishtimes.com/ireland/social-affairs/2025/07/22/people-in-disadvantaged-communities-have-more-negative-attitude-towards-immigration-esri-report-finds/ (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Ellis, Emily, Cassie Hazell, and Oliver Mason. 2024. The mental health of Ukrainian refugees: A narrative review. Academia Medicine 1: 6232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. 2025. Temporary Protection for 4.28 Million People in May 2025. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/w/ddn-20250710-1?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Fornaro, Michele, Claudio Ricci, Nicolas Zotti, Claudio Caiazza, Luca Viacava, Avihai Rubinshtain Tal, Raffaella Calati, Xenia Gonda, Georgina Szabo, Michele De Prisco, and et al. 2025. Mental health during the 2022 Russo-Ukrainian War: A scoping review and unmet needs. Journal of Affective Disorders 373: 12–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, John, and Sanford Weisberg. 2020. Companion to Applied Regression. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/package=car (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Hajak, Vivien L., Srishti Sardana, Helen Verdeli, and Simone Grimm. 2021. A systematic review of factors affecting mental health and well-being of asylum seekers and refugees in Germany. Frontiers in Psychiatry 12: 643704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawkins, Maren M., Marin E. Schmitt, Comfort Tosin Adebayo, Jennifer Weitzel, Oluwatoyin Olukotun, Anastassia M. Christensen, Ashley M. Ruiz, Kelsey Gilman, Kyla Quigley, Anne Dressel, and et al. 2021. Promoting the health of refugee women: A scoping literature review incorporating the social ecological model. International Journal for Equity in Health 20: 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health Service Executive. 2024. Getting Healthcare in Ireland. HSE Ireland. Available online: https://www.hse.ie/eng/services/healthcare-in-ireland/english/getting-healthcare.html#mental-health (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Health Service Executive & Department of Health. 2025. Sharing the Vision: A Mental Health Policy for Everyone—Implementation Plan 2025–2027. HSE Ireland. Available online: https://www.hse.ie/eng/about/who/mentalhealth/sharing-the-vision/sharing-the-vision-a-mental-health-policy-for-everyone-implementation-plan-2025-to-2027.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Huijts, Irene, Wim Chr. Kleijn, Arnold A. P. van Emmerik, Arjen Noordhof, and Annemarie J. M. Smith. 2012. Dealing with man-made trauma: The relationship between coping style, posttraumatic stress, and quality of life in resettled, traumatized refugees in the Netherlands. Journal of Traumatic Stress 25: 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irish Red Cross. 2024a. Mental Health and Psychosocial Supports for Ukrainian Refugees. Irish Red Cross. Available online: https://www.redcross.ie/ukraine-crisis-appeal/ (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Irish Red Cross. 2024b. Pledging Your Home: A Spotlight on Irish Hospitality for Those Displaced from Ukraine (Safe Homes Ireland Final Report). International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. Available online: https://www.redcross.ie/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Safe-Homes-Final-Report.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Kardas, Przemyslaw, Iryna Mogilevkina, Nilay Aksoy, Tamas Ágh, Kristina Garuoliene, Marta Lomnytska, Natalja Istomina, Rita Urbanaviče, Björn Wettermark, and Nataliia Khanyk. 2025. Barriers to healthcare access and continuity of care among Ukrainian war refugees in Europe: Findings from the RefuHealthAccess study. Frontiers in Public Health 13: 1516161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Cong, and Yi Liu. 2020. Media exposure, anxiety, and mental health during COVID-19: The moderating role of media literacy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17: 4720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazhak, Iryna, Ana Carolina Paludo, and Danylo Sudyn. 2024. Self-reported health and coping strategies of Ukrainian female refugees in the Czech Republic. European Societies 26: 411–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazhak, Iryna, and Danylo Sudyn. 2025. Psychometric assessment of the Beck anxiety inventory and key anxiety determinants among Ukrainian female refugees in the Czech Republic. Frontiers in Psychology 15: 1529718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Kenneth E., and Andrew Rasmussen. 2017. The mental health of civilians displaced by armed conflict: An ecological model of refugee distress. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences 26: 129–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modini, Matthew, Sadhbh Joyce, Arnstein Mykletun, Helen Christensen, Richard A. Bryant, Philip B. Mitchell, and Samuel B. Harvey. 2016. The mental health benefits of employment: Results of a systematic meta-review. Australasian Psychiatry 24: 331–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mykhaylyshyn, Ulyana B., Anatoliy V. Stadnik, Yuriy B. Melnyk, Jolita Vveinhardt, Madalena S. Oliveira, and Iryna S. Pypenko. 2024. Psychological stress among university students in wartime: A longitudinal study. International Journal of Science Annals 7: 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickerson, Angela, Richard A. Bryant, Zachary Steel, Derrick Silove, and Robert Brooks. 2010. The impact of fear for family on mental health in a resettled Iraqi refugee community. Journal of Psychiatric Research 44: 229–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connor, Karen, Margo Wrigley, Rhona Jennings, Michele Hill, and Amir Niazi. 2021. Mental health impacts of COVID-19 in Ireland and the need for a secondary care mental health service response. Irish Journal of Psychological Medicine 38: 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olcese, Martina, Francesco Madera, Paola Cardinali, Gianluca Serafini, and Laura Migliorini. 2024. The role of community resilience as a protective factor in coping with mental disorders in a sample of psychiatric migrants. Frontiers in Psychiatry 15: 1430688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, Niall, Emmet Smithwick, Eoin Murphy, and Aisling A. Jennings. 2025. The challenges experienced by Ukrainian refugees accessing General Practice: A descriptive cross-sectional study. Family Practice 42: cmaf012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. 2022. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Satinsky, Emily, Daniela C. Fuhr, Aniek Woodward, Egbert Sondorp, and Bayard Roberts. 2019. Mental health care utilisation and access among refugees and asylum seekers in Europe: A systematic review. Health Policy 123: 851–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilz, Laura, Solveig Kemna, Carine Karnouk, Kerem Böge, Nico Lindheimer, Lena Walther, Sara Mohamad, Amani Suboh, Alkomiet Hasan, Edgar Höhne, and et al. 2023. A house is not a home: A network model perspective on the dynamics between subjective quality of living conditions, social support, and mental health of refugees and asylum seekers. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 58: 757–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, Amanda, Lucy Bowes, and Frances Gardner. 2019. The promotive effects of social support for parental resilience in a refugee context: A cross-sectional study with Syrian mothers in Lebanon. Prevention Science 20: 674–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slewa-Younan, Shameran, Maria Gabriela Uribe Guajardo, Andreea Heriseanu, and Tasnim Hasan. 2015. A systematic review of post-traumatic stress disorder and depression amongst Iraqi refugees located in western countries. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 17: 1231–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spira, Janelle, Dafni Katsampa, Hannah Wright, and Kemi Komolafe. 2025. The relationship between housing and asylum seekers’ mental health: A systematic review. Social Science & Medicine 368: 117814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadesse, Gebresilassie, Fantahun Andualem, Gidey Rtbey, Girum Nakie, Girmaw Medfu Takelle, Ayenew Molla, Asnake Tadesse Abate, Getasew Kibralew, Mulualem Kelebie, Setegn Fentahun, and et al. 2024. Gender-based violence and its determinants among refugees and internally displaced women in Africa: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 24: 2851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Těšinová, Jolana Kopsa, Karolína Dobiášová, Marie Jelínková, Elena Tulupova, and Michal Koščík. 2024. Professionals’ and Intercultural Mediators’ Perspectives on Communication with Ukrainian Refugees in the Czech Healthcare System. Health Expectations 27: e14171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Jamovi project. 2023. Jamovi. [Computer Software]. Available online: https://www.jamovi.org (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Walther, Lena, Lukas M. Fuchs, Jürgen Schupp, and Christian von Scheve. 2020. Living conditions and the mental health and well-being of refugees: Evidence from a large-scale German survey. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 22: 903–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanberg, Connie R. 2012. The individual experience of unemployment. Annual Review of Psychology 63: 369–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).