Abstract

The management of natural hazard events has significant consequences for the well-being of the operators who find themselves intervening in these situations. In order to protect their mental health and ensure an effective response in support of the community, it is necessary to identify the factors that protect the well-being and resilience of operators and to exploit and enhance them. This rapid systematic literature review aims to detect and summarize evidence about protective factors of resilience and well-being among natural hazard events helpers; the literature was searched for on Scopus, Web of Science, Pub-med, and PsycINFO, resulting in 876 records. After a full-text screening, 84 records were selected to meet the inclusion criteria and examined in this paper. The results underline the variety of research methods and samples adopted by the included studies. Moreover, the results highlight the relevance of both the role of individual factors, such as personality aspects, coping strategies, and the level of exposure to the disaster/community, and the role of organizational/social factors, such as training, organizational issues and social support on the well-being and resilience of helpers. In conclusion, this rapid review indicates that the empowerment of helpers is an important source of resilience; it must be promoted inside the organization both at an individual and supportive level (through, for example, training on self-care strategies) and at a more organizational and social level, enhancing internal and team resources.

1. Introduction

A disaster is defined as the consequence of a large-scale ecological breakdown in the relationship between a population and its environment, where the demands placed on available resources exceed their capacity (Gunn 2007). In such situations, the disaster overwhelms the response capabilities of the affected community, leading to a breakdown in social structures, severely impairing the ability of survivors to function and respond normally (Pérez-Sales 2004). Natural hazard events, particularly, are such disasters that are caused by sudden-onset natural hazards. The term “natural” disaster is used for ease, although the magnitude of the consequences of sudden natural hazards is a direct result of the way individuals and societies relate to threats originating from natural hazards. The magnitude of the consequences is therefore determined by human action, or the lack thereof (IASC 2011). Responding to natural hazard events necessitates the rapid deployment of a wide array of resources aimed at containing the crisis. Disaster management is inherently complex, involving collaboration among a broad network of agencies, authorities, professionals, and organizations that work together to ensure public safety, provide relief, and support community recovery and reconstruction. In emergency contexts, a fundamental priority is to support and assist the affected population by safeguarding and promoting mental health and psychosocial well-being. This requires coordinated efforts among humanitarian actors to strengthen community resilience (Norris et al. 2008).

The word “resilience” originates from the Latin resilire, which translates to “to leap back” or “to bounce back.” Across various disciplines, it conveys the idea of rebounding. In 1973, Holling introduced the concept into socio-ecological studies, describing it as a system’s ability to withstand disturbances while maintaining its core functions (Gunderson et al. 2012). The American Psychological Association (APA) similarly describes resilience as the capacity to positively adapt when confronted with adversity or significant stress (APA 2025). According to the literature about resilience, it is a construct linked to many other factors, such as adaptive coping strategies (Masten 2001), positive emotions (Tugade et al. 2004), or trauma adaptation (Bonanno 2004). Moreover, in the disaster management context, some aspects are associated with the individual resilience of workers and volunteers, for example, the leadership behaviors of managers (Salehzadeh 2019) or co-workers’ support (Dutta and Rangnekar 2024), coordination, and communication at intraorganizational and interorganizational levels (Fahim et al. 2014).

In this framework, therefore, it is crucial to be aware that the incisiveness of the emergency response depends on the ability to adequately value and protect the human resources involved. The contributions of helpers, individuals who respond to disasters, whether paid staff or volunteers (Quevillon et al. 2016), among which we consider first responders, humanitarian workers, NGO members, and humanitarian volunteers (IASC 2007), as well as cultural and linguistic mediators, whose presence is particularly relevant in multicultural and highly vulnerable contexts, must therefore be recognized. Their mental health and psychosocial well-being, the safeguarding of which is recommended by the main bodies regulating humanitarian intervention (WHO 2011; IASC 2007), represents a strategic element not only for the quality of the intervention, but also for the overall resilience of the emergency response system and for the ultimate goal of empowering the affected community. Indeed, according to the literature, it seems that experiences as a disaster first responder or volunteer can lead to severely compromised individual well-being and mental health (Hagh-Shenas et al. 2005; Saito et al. 2022; Maeno et al. 2024).

Throughout the past decades, research on disaster responses and mental health has largely concentrated on documenting the psychological consequences experienced by helpers. Indeed, most previous research has emphasized psychopathology over resilience. Meta-analyses and systematic reviews have focused heavily on mental health challenges and treatments following disasters, particularly focused on Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and dysfunctional emotional activity (PTSD; e.g., Arena et al. 2025; Aporosa et al. 2025; Martínez and Blanch 2024; Liang et al. 2019; Marocco et al. 2025a, 2025b), while protective mechanisms aimed at favoring resilience have often remained secondary. Moreover, when it comes to strategies aimed at enhancing coping interventions in the face of natural hazard events, the existing literature frequently examines single determinants in isolation, such as self-coping strategies or improvisation skills (Çakaloğlu et al. 2025; Briones et al. 2019). Recent research has acknowledged the complexity of an integrative resilience framework (Çakaloğlu et al. 2025), yet it often remains focused on the analysis of specific disasters’ effects. Hence, there appears to be a notable absence of studies that have attempted to integrate individual, organizational, and social dimensions into a cohesive resilience framework, encompassing diverse types of natural hazard events, including a different range of cultural and geographical contexts.

Thus, to address these gaps, the objective of this rapid systematic review is to examine how the resilience and well-being of helpers can be supported, particularly by emphasizing the critical importance of empowering the responders themselves and ensuring the protection of their mental and physical health (Quevillon et al. 2016). In this framework, resilience is not considered solely as an individual personality trait, but rather as a collective trait that applies to the entire team, organization, or system;0 in this sense, contextual and organizational factors are explored as fundamental and influential for the well-being of operators.

Aims of the Study

To this end, protective factors of the resilience of professionals and volunteers are examined in the literature, in order to collect and evaluate individual and collective resources of these groups. These resources play a primary role in promoting community resilience in populations that have suffered natural hazard events. Thus, our primary research question is as follows:

What are the protective factors of the resilience and well-being of helpers involved in natural hazard events management?

More specifically, we aimed to investigate the following:

What is the impact of individual factors of helpers involved in natural hazard events management on their resilience and well-being?

What is the impact of social or organizational aspects in favoring and empowering the resilience and well-being of helpers involved in natural hazard events management?

2. Methods

2.1. The Rapid Systematic Review Approach

A rapid systematic review of the literature was conducted in April 2025 to examine the protective factors supporting resilience and well-being among helpers involved in the management of natural hazard events. According to Tricco et al. (2017), a rapid review is a type of knowledge synthesis in which components of the systematic review process are simplified or omitted to produce information in a short period of time. This approach was adopted due to constraints in time and available resources, consistent with the methodological guidance for conducting rapid reviews (Tricco et al. 2017).

This review was not registered in a public database, due to its rapid nature and time constraints, factors commonly associated with rapid evidence syntheses.

2.2. Search Strategy

The review process was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) framework (Page et al. 2021). An overview of the literature regarding the chosen research topic allowed us to define the main subtopics and thus organize the search by keywords. The chosen word string was: “relief operator*” OR “relief worker*” OR “first responder*” OR “humanitarian relief worker*” OR “helper*” OR “relief organization*” OR “first aid responder*” OR “public health worker*” OR “rescue personnel” OR “volunteer*” AND “natural disaster*” OR “earthquake*” OR “flood*” OR “hurricane*” OR “tsunami*” OR “wildfire*” OR “volcanic eruption*” OR “drought*” OR “tornado” OR “volcano” AND “protective factor*” OR “resilience” OR “wellbeing” OR “well-being” OR “well being” OR “psychological well-being” OR “psychological well being” OR “psychological wellbeing” OR “growth” OR “mental disorder*” OR “mental health” OR “stress” OR “post-traumatic stress disorder” OR “PTSD” OR “trauma”.

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The search was limited to peer-reviewed journal research articles published in English about the protective factors of the resilience and well-being of natural hazard events’ emergency helpers. In this review, according to the definition by Quevillon et al. (2016), we use the term “helpers” to refer to individuals who respond to disasters, whether paid staff or volunteers. Thus, all the articles about survivors or victims of natural hazard events were excluded, as well as articles about non-natural hazard events (wars, man-made disasters, and environmental disasters…). Qualitative, quantitative, or mixed-method papers were included, whereas non-research articles (e.g., review papers, dissertations, and book chapters) were not considered in this rapid systematic review. Regarding the papers’ outcomes, papers that do not provide information on factors that promote resilience, well-being, and the mental health of operators were excluded. Furthermore, articles whose full text was not available or was available in a language other than English were excluded.

2.4. Data Extraction and Selection

The literature search was conducted on Scopus, PsycINFO, Web of Science, and Pub-med databases and identified 1468 records. In the database searches, no filters were applied based on discipline or year of publication; since this is a cross-disciplinary topic, the aim of this choice was to obtain a more comprehensive overview of the topic of interest.

These records were uploaded into Rayyan.ai software (Mourad et al. 2016), an Intelligent Research tool, aimed at optimizing the papers’ coding and selection: it allows researchers to import citations, remove duplicates, work in teams, and annotate the reasons for inclusion/exclusion.

The selection of studies was conducted by a single reviewer, with retrospective verification in doubtful cases by the second author. This choice was dictated by time and resource constraints, considering that this was a rapid systematic review. This procedure is consistent with the methodological recommendations for rapid reviews (Tricco et al. 2017), although it represents a recognized limitation in terms of the potential risk of bias in the selection phase.

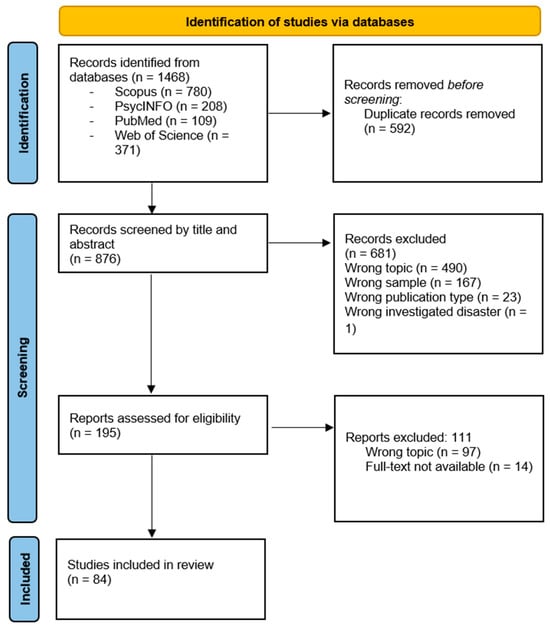

Firstly, a duplicate check was performed, resulting in 592 duplicates. Thus, 876 records were selected for the title and abstract screening. Then, after the title and abstract screening, 681 records were excluded for the following reasons: 490 for the wrong topic of paper, 167 for considering an incorrect sample, 23 for wrong publication type, 1 for wrong investigated disaster. Following the full-text screening, an additional 111 records were removed due to the inadequacy of their contents, which were incoherent with the main themes of this article. Finally, 84 records were included in the review for meeting the established inclusion criteria. Below the PRISMA flowchart of the selection process is presented (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart.

2.5. Quality Assessment of Included Studies

The quality and risk of bias of the 84 eligible studies were assessed using (CASP 2024) checklists for quantitative and qualitative research, and the Mixed-Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT; Hong et al. 2018) for mixed-method studies. This evaluation aimed to ensure that all included studies met methodological standards and to reduce potential bias, thereby enhancing the reliability and validity of the findings in this rapid systematic review. Both the CASP and MMAT provide structured frameworks for critically appraising the rigor, credibility, and trustworthiness of individual studies. By systematically assessing each study’s quality, we sought to strengthen the overall evidence base regarding protective factors of resilience and well-being among responders to natural hazard events.

All studies included in the review met or exceeded the threshold for adequate methodological quality, as indicated by scores of six or higher out of ten on the CASP and three or higher out of five on the MMAT. Quality assessment was not performed for Hsiao et al. (2019), Li et al. (2023), McBride et al. (2018), Saito et al. (2022), and Thormar et al. (2012, 2016) due to their longitudinal studies nature for which there was no systematic quality assessment tool found. Full details of the quality assessment are available in the Supplementary Materials.

3. Results

3.1. Type of Studies

Included studies adopted both qualitative research design, using interviews, focus groups, or reports, and quantitative research design, implementing various types of questionnaires and surveys, and mixed research design (Table 1).

Table 1.

Classification of the included articles.

Qualitative methods were used in 23 studies: for example, in Bronisch et al. (2006), Qiu et al. (2024), Schechter (2008), Ren et al. (2018), and Wang et al. (2013). Differently, quantitative methods were implemented in 53 articles: for instance, in Ai et al. (2013), McBride et al. (2018), Wang et al. (2011), Maeno et al. (2024), Saito et al. (2022), Thormar et al. (2012), and Hagh-Shenas et al. (2005). Finally, eight studies employed mixed-methods, such as Snell et al. (2014) and Guglielmi et al. (2017).

3.2. Samples of the Selected Studies

This section presents the samples of participants involved in the studies included in the review. Since disaster management involves numerous actors, the researchers deemed it appropriate to include this type of classification in the review in order to provide a more accurate overview of the studies included. Samples of studies are various and cover a wide range of emergency professionals and volunteers.

3.2.1. Volunteers

According to the revised papers, the samples were diversified across studies, with a significant number involving civilian volunteers. For instance, Iseri and Baltaci (2024) included civilian volunteers among their study participants, while Scuri et al. (2019) focused on volunteers active during the 2016 Central Italy earthquake. A range of formal volunteer organizations were also represented: Thormar et al. (2012, 2016) and Koçak et al. (2025) focused on Red Cross volunteers involved in post-disaster interventions, while Paton (1994) involved members of a charitable disaster relief organization. Clukey (2010) studied disaster relief volunteers’ experiences.

The role of spontaneous and non-professional volunteers was highlighted in recent research. Fekete and Rhein (2024) studied spontaneous civilian volunteers who played a pivotal role in disaster response, while Bekircan et al. (2024) investigated disaster volunteers who received online psychological first aid. These participants were primarily non-professionals who benefited from remote support interventions aimed at enhancing resilience and reducing stress. Other studies looked at diverse volunteer groups more broadly: Cristea et al. (2014) focused on volunteers engaged in activities such as meal preparation for displaced individuals, camp sanitation, and the distribution of clean linens; Vannier et al. (2021) included both volunteers and coordinators; and Bhushan and Kumar (2012) studied female relief volunteers who had participated in the post-tsunami relief operations in India, specifically. Zachariah et al. (2023) conducted studies involving trained volunteers, while Dewi et al. (2023) explored disaster workers by comparing trained staff and untrained volunteers.

Additionally, some studies looked at specialized or context-specific volunteers. Kaufmann et al. (2020) studied voluntary canine search and rescue dog handlers, while. Li et al. (2023) and Dass-Brailsford and Thomley (2012) included adult mental health volunteers in their quantitative study. Several studies focused on student volunteers: Hagh-Shenas et al. (2005) incorporated student volunteers into their mixed sample, whereas Ai et al. (2011, 2013) specifically focused on undergraduate and graduate student volunteers enrolled in mental health programs.

3.2.2. First Responders and Relief Personnel

Several studies have examined the psychological and operational experiences of individuals involved in disaster response, drawing from a wide range of first responder and relief personnel samples. Many of these focused specifically on professional first responders. For example, Wyche et al. (2011) studied first responders who assisted Hurricane Katrina survivors, while Iseri and Baltaci (2024) included professional firefighters and search and rescue workers in their exploration of the mental well-being of disaster relief professionals. Police officers and other law enforcement personnel were included in samples of other studies too. These include Adams et al. (2011), McCanlies et al. (2017), Heavey et al. (2015), Snell et al. (2014), and Surgenor et al. (2015). Komarovskaya et al. (2014) explored the experiences of both police and firefighters, while Chang et al. (2003, 2008) and Paton (1994) focused solely on firefighters.

Several studies targeted disaster relief teams and rescue personnel, both local and international. These include the works by Soffer et al. (2011), which examined the reactions of rescue personnel members involved in body extraction during the Haiti earthquake, and Wang et al. (2013, 2016), who focused on local disaster relief officials and workers engaged, for instance, in providing healthcare, distributing materials, and working for reconstruction and resettlement. Conversely, Qiu et al. (2024) interviewed emergency assistant personnel covering management, logistics, security, or medical support positions, and Blomberg et al. (2024) researched different types of local and international disaster responders, mainly from medical, urban rescue, and management and coordination positions. Similarly, Yikilmaz et al. (2024) targeted disaster response workers active in earthquake response and employed at the Disaster and Emergency Management Presidency in Turkey.

Other studies encompassed both professional and volunteer disaster responders. Fekete (2021) and Fekete and Rhein (2024) included both professional and volunteer operational forces involved in the 2021 German flood response and Hagh-Shenas et al. (2005) included a mixed group of student volunteers along with Red Crescent workers and firefighters. Similarly, Putman et al. (2012) looked at faith-based relief providers, both workers and volunteers, from an organization that worked with Katrina evacuees in the state of Texas.

Gonzalez et al. (2019) studied a general responder population, comparing it with community members, and Kc et al. (2019) interviewed 11 disaster management experts in Nepal, including academics, government and military officials, police officers, and humanitarian recruiters. McBride et al. (2018) differentiated between traditional responders (ambulance, fire, police, and military) and non-traditional responders such as utility workers, construction crews, teachers, Māori Wardens, and NGO staff. Finally, some studies focused on specific responder demographics or local personnel, for example, Huang et al. (2013) and Liao et al. (2002) focused specifically on male rescue workers. Sakuma et al. (2015) included only local responders such as firefighters, municipal workers, and hospital medical staff.

3.2.3. Mental Health and Healthcare Professionals

Regarding disaster rescue, moreover, some authors implemented research on mental health and healthcare professionals: Bronisch et al. (2006) studied a multidisciplinary team (emergency physicians from Munich-Schwabing, psychiatrists, psychologists, paramedics, pastors, and those with trauma therapy experience), Lambert and Lawson (2013) focused on counselors, and Ren et al. (2018) had a mixed sample of ten counselors, three psychiatric nurses, four psychiatrists, and six social workers. Like the latter was the study of Razakarivony et al. (2021) whose participants were professionals from the French medical–psychological emergency units (24 psychiatrists, 15 paramedical staff, and 14 psychologists).

In general, several other studies examined public health workers’ disaster response experience. For instance, Mash et al. (2013, 2023), Fullerton et al. (2013), and Ursano et al. (2014) focused on public health workers from the Florida Department of Health; Guglielmi et al. (2017) explored nurses, social workers, physicians, and administrative staff experiences from the Modena Local Health Authority. Similarly, Fahim et al. (2014) had a varied sample composed of physicians, nurses, program managers, epidemiologists, and social workers/psychologists and Schenk et al. (2017) focused on medical rescue workers including physicians, nurses, and organizational leaders. Also, Peng et al. (2024) involved emergency medical first responders from 42 hospitals across 6 provinces in China in their system-based training program. The study evaluated their psychological well-being, coping skills, and perceptions of their professional quality of life. Similarly, Ma et al. (2020) and Hsiao et al. (2019) studied emergency medical technicians and paramedics from the Tainan City Government Fire Bureau, whereas Tang et al. (2015) explored experiences of both military and non-military medical rescue workers and Kang et al. (2015) investigated medical rescuers both from local and supporting forces. Lee et al. (2017) studied disaster relief team members related to the health profession (e.g., doctors and nurses). Conversely, Parlak et al. (2025), Mert and Koksal (2025), Celebi Cakiroglu et al. (2025), and Shih et al. (2002) focused on nurses working and volunteering in disaster areas. Similarly, Ueda et al. (2017) included 819 social welfare workers.

Additionally, Ayalon (2006), Berger et al. (2016), and Gelkopf et al. (2008) implemented studies with school counselors, psychologists, and mental health workers, whereas Dass-Brailsford (2008) and Schechter (2008) reported the experiences of disaster mental health responders deployed after Hurricane Katrina. Finally, Ng et al. (2009) involved professional and volunteer leaders in disaster mental health responses from across China in a training program using testing and evaluation.

3.2.4. Military Personnel

Other articles explored the protective factors of resilience in military personnel: Wang et al. (2011) included male soldiers which participated at the emergency management caused by the Wen-Chuan earthquake and Cetin et al. (2005) was examined 434 conscripted military personnel in rescue operations and 154 non-rescuers. Maeno et al. (2024), Saito et al. (2022), and Nagamine et al. (2020) focused on the Japan Ground Self-Defense Force, one of the three main components of the Japanese armed forces. Finally, Krishna and Damle (2017) focused on military and paramilitary officials.

3.2.5. School Personnel

Some of the explored studies implemented research on school personnel involved in disaster relief efforts. Hugelius et al. (2017) included teachers operating after the Christchurch earthquake in New Zealand. Ayalon (2006) and Berger et al. (2016) investigated the impact of training programs on educators, teachers, and school counselors.

3.2.6. Mixed Sample

Some studies involved mixed samples. van der Velden et al. (2012) explored a mixed sample of rescue workers including firefighters, police officers with trained dogs, nurses, surgeons, and communication staff. Similarly, Lanza et al. (2018) examined a diverse group of first responders, including firefighters, police officers, EMTs, mental health practitioners, clergy, and emergency phone responders and Shepherd et al. (2017) included in police officers, firefighters, ambulance staff, and school teachers involved in disaster responses in Christchurch, New Zealand. Finally, Johnson et al. (2025) interviewed decision makers and information providers about their experiences during flood events, whereas Scharffscher (2011) involved representatives of women’s organizations and local and national non-governmental organizations based in Batticaloa, as well as international humanitarian agencies.

3.3. Protective Factors of Resilience and Well-Being of Natural Hazard Events Helpers

The thematic analysis of protective factors of resilience and well-being among helpers was carried out by three researchers. Themes were identified through recursive reading, manual coding, and resolving disagreements through discussion and consensus. No statistical methods were used, as the approach was qualitative/interpretive. The principal findings regarding the protective factors of the resilience and well-being of natural hazard events helpers are synthesized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Principal findings regarding protective and risk factors of resilience and well-being of natural hazard events.

3.3.1. Training

The training factor appears to be fundamental for the resilience of rescue workers and volunteer helpers in the studies considered. Disaster preparedness training should include psychological and moral dimensions, not just technical skills (Hugelius et al. 2017), providing relief workers with the possibility of retrieving and processing the daily events of emergency management.

It emerged that training promotes a sense of self-efficacy, self-mastery (Gelkopf et al. 2008), self-compassion, and self-care (Lanza et al. 2018), and reduces stress and the risk of developing psychopathology (Dewi et al. 2023; Scuri et al. 2019). Moreover, as reported in Ng et al. (2009), Ayalon (2006), and Schechter (2008), a training program contributes significantly to the building of the national and local capacity to deliver psychological first-aid and psychosocial response management to assist the populations who have been affected by disaster, increasing both the helpers’ and the community’s resilience. Also, in Kc et al. (2019), untrained bystanders appeared more vulnerable than professionals; training and post-deployment health monitoring emerged as mitigation strategies, whereas the latter was often lacking, especially for unaffiliated volunteers.

The impact of specific training programs is examined in the studies by Gelkopf et al. (2008) and Berger et al. (2016), both of which implemented the universal school-based resiliency intervention, ERASE-Stress. Gelkopf et al. (2008) reported improvements in professional self-efficacy, the sense of mastery, personal optimism, and the use of cognitive coping strategies. Berger et al. (2016) found that the intervention led to reduced PTSD symptoms, lower levels of compassion fatigue, and burnout, and increased compassion satisfaction, professional self-efficacy, optimism, hope, resilience, and improved coping strategies.

Training in psychology and self-care strategies has emerged and become very important and useful for the mental health and well-being of rescue workers (Dass-Brailsford and Thomley 2012; Ren et al. 2017; Krishna and Damle 2017; Kang et al. 2015). Furthermore, Dass-Brailsford (2008) and Ren et al. (2017) emphasized the importance of a cultural approach in population-oriented psychosocial interventions, the influence of trainers’ attitudes and behaviors on trainees, and the idea that training (as an intervention) should be grounded in local realities and culture, in line with workers’ needs and responsive to survivors’ expectations, rather than being based on abstract theories or imported models.

The person’s experience as a rescuer, whether or not they have already been involved in managing other emergencies, is also investigated as a training factor, including those having already been involved in other disaster management and having received training resulting in less negative outcomes (Hagh-Shenas et al. 2005). Differently, older age is associated with higher psychological vulnerability, potentially due to cumulative stress or reduced resilience (Iseri and Baltaci 2024; Nagamine et al. 2020).

Contrary to previous studies, findings by Tang et al. (2015) and Thormar et al. (2012) indicated that training is not a significant predictor of health-related quality of life or of the absence of psychopathology, respectively. This result may serve as a reminder to policymakers to critically examine the content and quality of the rescue training provided to personnel prior to deployment. There is a clear need to promote comprehensive and systematic disaster relief training among helpers.

3.3.2. Individual Personality Factors

A contributing factor to resilience was individual perceptions and personal experience, which shaped how responders engaged with a situation. Personal attitudes, interpretations of events, and coping strategies influenced levels of resilience, motivation, and initiative-taking. Thus, while some individuals were able to adapt and act proactively, others struggled in the absence of external support structures (Fahim et al. 2014).

Regarding individual personality factors, Ai et al. (2013) explored altruism and perceived spiritual support, which resulted in the protection of resilience with optimism and hope as mediators. The latter two also emerged as strengths in Ai et al. (2011), although with some cultural differences between European Americans and African Americans, among whom hope seems to be more important as a protective factor of resilience. Moreover, optimism and altruism also emerged as relevant resilience factors in Wang et al. (2013) and Hugelius et al. (2017), respectively. Li et al. (2023) explores these constructs too and, as in Surgenor et al. (2015), optimism results in a significant protective factor of post-traumatic stress symptoms, whereas altruism does not, and has a non-significant impact. However, according to Cristea et al. (2014) empathic concern buffered depression, confusion, and general distress between volunteers from across Italy.

Ma et al. (2020) and Hsiao et al. (2019) focused on personality traits and PTSD prevalence in emergency medical personnel; in the former, an anxious personality emerged as significant risk factor for PTSD according to the multivariate model, and perfectionism and introversion were not. In the latter, perfectionism and guilt/self-blame resulted related to higher PTSD scores. This evidence is interesting because the samples of both the studies originate from the Tainan City Government Fire Bureau. Huang et al. (2013) and Liao et al. (2002) investigated personality traits too, revealing that highly neurotic personalities and personalities prone to anxiety are risk factors for distress experiences.

Regarding coping, some studies investigated the role of coping strategies, as buffers against psychopathology, on the resilience of helpers; in Chang et al. (2008), coping emerged as moderator between the stress experienced and its effect on individuals, depending on exposure intensity levels. Soffer et al. (2011) explored the extent to which practitioners believed they had handled the situation after the disaster, finding high levels of perceived coping. Moreover, in Shepherd et al. (2017), McBride et al. (2018), and Surgenor et al. (2015), maladaptive/dysfunctional coping (e.g., denial, venting, and self-blame) was linked to higher PTSD and lower resilience, whereas adaptive coping (e.g., acceptance and planning) was associated with higher resilience, although with some gender differences. In Li et al. (2023) and Huang et al. (2013), negative coping strategies, such as self-blame or repression, had a small but consistent effect on distress in the former and were positively associated with PTSD in the latter. Similarly, in Schenk et al. (2017) passive coping styles (such as drinking or smoking) were more related to stress symptoms, and in Chang et al. (2003, 2008), some specifical coping strategies were linked to less distress: positive reappraisal, distancing, and escape-avoidance strategies were associated with post-traumatic morbidity. Adams et al. (2011) reported that emotion-focused coping was prevalent between officers of the police department of New Orleans, examples such as communication with others, detachment, and prayer were key factors. Problem-focused coping (e.g., planning and direct action) was less prevalent due to chaotic conditions and a lack of operational infrastructure; resilience was rooted in emotional regulation, solidarity, and informal peer support.

Wang et al. (2013) found that coping experiences included the following: finding meaning and purpose in life through relief work, the suppression or avoidance of grief, greater appreciation for life, hardiness, letting nature take its course, and making up for loss. Moreover, Mert and Koksal (2025) report evidence consistent with the above, and identified maintaining a positive mindset, relying on optimism or fate, seeking support from family and peers, being professional in dread, expressing emotions, relying on team dynamics, and upholding professional ethical values as coping mechanisms in nurses who helped during the 2023 Turkish earthquake. Relating to others, appreciation of life and proactive coping were key dimensions of post-traumatic growth in Bhushan and Kumar (2012) too. Religious coping was also investigated: in Putman et al. (2012), positive religious coping, particularly religious helping and spiritual connections through shared spiritual practices like prayer, scripture reading, and worship, were used and were protective for faith-based relief providers, whereas self-directing religious coping (a religious coping strategy in which the person relies primarily on their own resources and decisions to deal with stressful situations, interpreting their autonomy as a gift or responsibility bestowed by God; Pargament et al. 1988) was identified as a negative coping strategy linked to burnout.

Finally, traumatic previous experiences, such as exposure to childhood/adolescent physical victimization, were explored in Komarovskaya et al. (2014), resulting in significant statistical predictors of several mental health outcomes between police members and firefighters.

3.3.3. Level of Exposure to Disaster/Community

Saito et al. (2022) and Nagamine et al. (2020) reported how being personally affected by a disaster was a risk factor for mental health in a sample of military personnel, whereas, according to Wang et al. (2016), participation in disaster relief may have been beneficial for a sample of aid workers who were also survivors. Similarly, in Hugelius et al. (2017) the dual role of being both responder and survivor emerged as generator of emotional complexity, requiring the individual to contend with the psychological conflict between the positive emotions associated with providing help and the negative emotions arising from their own experience of victimization. In Kang et al. (2015) it also emerged that local rescuers had significantly lower well-being scores with respect to supporting external rescuers, suggesting a negative outcome of being part of the community that needed help.

Moreover, according to Heavey et al. (2015), the heavy involvement of police officers deployed during Hurricane Katrina was significantly associated with higher Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) scores, suggesting a distress consequence of involvement grade during emergency operations. Gonzalez et al. (2019), in line with these studies, found that greater exposure severity was associated with higher PTSD prevalence. Additionally, they showed that being a responder, as opposed to a community member, was linked to experiencing lower levels of distress.

Similarly, Wang et al. (2011), Thormar et al. (2012), Kang et al. (2015), and Fullerton et al. (2013) explored the impact of disaster exposure on psychopathology symptomatology, revealing that a greater intensity of exposure corresponds to a greater intensity of symptoms in relief workers and volunteers. Similar conclusions are found in Soffer et al. (2011). However, in Shepherd et al. (2017), disaster exposure does not predict mental health alterations, but singular exposure trauma events do. Surprisingly, Lambert and Lawson (2013) and Ren et al. (2018) found that counselors who were personally affected by a disaster had significant levels of post-traumatic growth, higher than volunteers who were not, in the former. Similarly, Zachariah et al. (2023) reported that volunteers experienced resilience and personal growth, even if emotional strain emerged due to repeated exposure to trauma and adverse conditions; self-care routines (exercise, debriefing, and grounding techniques) helped to mitigate distress. In Thormar et al. (2016), more resilient volunteers were more likely to perform body recovery tasks, suggesting a positive outcome even from such unpleasant activities, or a reason to implement them.

In Cetin et al. (2005), moreover, it is reported that identification with deceased victims, especially when the rescuer imagines themselves or a friend as the victim of the disaster, is associated with higher levels of PTSD symptoms among disaster workers: particularly, handling human remains and empathizing with victims have been classified as emotionally distressing in Ma et al. (2020) and Hsiao et al. (2019). In Surgenor et al. (2015) distress was generated by exposure to grotesque scenes and in Huang et al. (2013), near-death experiences, contact with corpses, witnessing of the deceased or seriously injured, severe trauma during rescue, or working at the epicenter, are factors strongly associated with psychopathology in responders. However, according to Bekircan et al. (2024), receiving an intervention of PFA significantly reduces involuntary exposure symptoms and increases resilience scores.

In Bronisch et al. (2006) a Disaster Victim Identification team reported to have no contact with the relatives of victims, as a protective factor of resilience and well-being. Similarly, in Krishna and Damle (2017), high public expectations, exposure to death and destruction, and an inability to save lives despite best efforts are suggested as stress factors for military officials.

3.3.4. Organizational Factors

Organizational elements emerge as fundamental to the well-being of care workers, as evidenced by the experience of Thormar et al. (2016), which revealed that extended working hours are directly linked to anxiety and subjective health symptoms at 18 months, and emphasized the importance of early organizational support, particularly six months after a disaster, as a crucial buffer against PTSD, depression, and anxiety. Their findings underscore how feeling safe and supported, especially through sustained team leadership, is central to volunteer resilience, similarly to what was found by Snell et al. (2014) in police staff. Yikilmaz et al. (2024) explore the impact of leadership on the well-being of relief workers, revealing a significant effect of servant leadership on their emotional exhaustion. It is an approach to leadership that focuses on the well-being and development of team members rather than the power or control of the leader: the servant leader focuses on helping others grow and reach their full potential, creating a positive and productive work environment. Specifically, the effect of leadership emerged as being mediated by workplace buoyancy, the capacity to effectively handle the difficulties and setbacks that are inherent in the workplace and commonly experienced by many individuals (Yikilmaz et al. 2024).

The findings in Ren et al. (2017) and Parlak et al. (2025) align with previous ones: the former highlights the role of interprofessional cooperation, ongoing supervision, and role-modeling in bolstering psychological safety; the latter underlines that moral commitment in volunteering helped nurses cope with their difficult experiences of organizational coordination and communication. Similarly, Ueda et al. (2017) point to the damaging effects of poor internal communication, reinforcing the importance of peer support networks in mitigating mental health issues. Communication, participation, structure, roles, and responsibilities, also by the first responders’ team in Wyche et al. (2011), are indicated as the main components to engage with when aiming to strengthen team resilience. Also, in Mash et al. (2013) common concerns included lack of role clarity, inadequate deployment planning, and extremely long work hours, often ranging from 12 to 16 h per day. Stress was further intensified by inconsistent crew overlap and frequent job reassignments, which disrupted continuity and increased workload confusion. Rest and support are identified as essential by employees of the Turkish Red Crescent organization in Koçak et al. (2025), and their absence is highlighted as a source of stress.

Similarly, in Lanza et al. (2018), workplace stigma and fear of discrimination, united with lack of systemic support emerged as risk factors for psychological issues, whereas in Sakuma et al. (2015), lack of communication had the same impact. In Fahim et al. (2014), a primary driver of support needs was unclear expectations and systemic disorganization, which contributed significantly to responders’ emotional distress. Participants described experiences of uncertainty, confusion, and fear stemming from undefined roles, poor coordination across teams and organizations, inadequate safety protocols, and a lack of both training and psychological/physical support. The absence of psychological counseling emerged as risk factor for the mental health impairment of military responders in Wang et al. (2011) too; moreover, since participation in psychological counseling was voluntary, the authors suggest that non-participation may be a symptom of avoidance, associated with the development of post-traumatic stress.

The disaster relief volunteers sample from Clukey (2010) reported organizational challenges too. One of the most salient issues cited was frustration with leadership: many volunteers cited inefficiencies resulting from inexperienced or inadequately trained leaders, which frequently hindered timely and effective decision making. In numerous cases, volunteers found themselves needing to “work around the rules” to address urgent needs of the population, often bypassing formal procedures. The problem was further exacerbated by leadership turnover, which led to a loss of institutional knowledge and poor coordination. Compounding these issues was a lack of interpersonal and communication skills among supervisors, which negatively affected morale and hindered team cohesion. Similarly in Paton (1994): firefighters sample reported role uncertainty, leadership problems, inactivity, lack of support, and staff issues as main stressors, whereas volunteers’ sample was affected by challenges in inter-team relations too. Organizational inefficiencies, such as inaccurate needs assessment and poor resource management, hindered effectiveness and added stress in nurses too, according to Shih et al. (2002).

Fahim et al. (2014) interviewed participants reported difficulties also in the coordination between all the organizations that affect rescue operations: a breakdown in coordination and leadership structures led to early response efforts as chaotic, fragmented, and lacking a clear chain of command. Moreover, reports of egocentric behavior and territoriality, particularly among larger organizations, undermined the collaborative spirit necessary for effective collective action of responders. This aspect emerged in Scharffscher (2011) too, specifically regarding the difficult relationship between local women’s relief initiatives and international relief workers operations in Batticaloa. Disconnection between these two sources of resilience may have led to a disempowerment of local capacities, flaws in the international relief activities, and reduced resilience among Batticaloan women.

Leadership itself introduces unique pressures, as Razakarivony et al. (2021) note: psychiatrists leading teams reported elevated stress due to heavy responsibilities, unfamiliar colleagues, and unstable environments. Interestingly, Wang et al. (2016) offer a counterpoint by suggesting that being immersed in relief work may provide emotional structure and connection, possibly protecting volunteers from acute grief. However, Nagamine et al. (2020) warn that prolonged deployments and excessive workloads upon return can heighten mental health risks, illustrating the delicate balance between engagement and overload.

Moreover, informal leaders, such as neighborhood heads, community figures, and religious leaders, play a vital role in disaster response by offering emotional support and guidance to volunteers. Though not formally part of the volunteer structure, they emerge organically within communities and foster morale and stress relief through informal conversations and relational presence. Their influence is rooted in trust, cultural familiarity, and shared values, making them key contributors to volunteer well-being during crises (Dewi et al. 2023).

Information and communication failures were reported as crucial problems for helpers in Fekete (2021), highlighting the need for better digital tools, risk maps, and interorganizational transparency. The study calls for improved coordination and leadership training, factors highlighted as essential for volunteers in Vannier et al. (2021): indeed, they reported that coordinators fostered inclusive, caring environments, facilitated bridging and bonding across diverse groups and that leadership contributed to emotional support, structure, and encouragement. Similarly, in Mash et al. (2013) negative experiences included poor communication, lack of leadership, besides prolonged shelter shifts and in Fekete and Rhein (2024) emotional stress was linked to lack of rest, unclear roles, as well as the level of exposure to trauma. In van der Velden et al. (2012) participants resulted with no significant increase in psychopathological symptoms: positive team dynamics, collaboration and strong support from colleagues and superiors post-return are reported as deployment experiences.

In Lee et al. (2017) organizational issues were particularly prominent between responders, including conflict with the control tower, delayed decision making, and reversed orders, all of which contributed to confusion and operational inefficiency. Respondents also pointed out a lack of expert consultation and sudden shifts in mission priorities as further sources of stress. Systemic shortcomings, such as poor coordination with other organizations and inadequate disaster preparedness, were frequently cited. Interpersonal dynamics also emerged as a recurring concern, with volunteers describing difficulties in cooperating with unfamiliar team members, confusion regarding roles and duties, and strained collaboration, undermining team cohesion. Overwork and manpower shortages further exacerbated the pressure on teams. Post-deployment, volunteers noted challenges such as administrative backlog and perceived low collaboration from colleagues who had not participated in the response.

Finally, in Johnson et al. (2025), intraorganizational and interorganizational themes were highlighted between information providers and decision makers of emergency management. Open communication between all the elements involved in the response, such as external support, significantly reduced the pressure on the team. Moreover, the necessary changes in leadership style were reported as positive: a calm and authoritative style is considered essential for guiding the team, while a playful and less serious style is considered useful for reducing tension and boosting morale.

3.3.5. Social Support

Social support is consistently identified in the literature as a key protective factor for psychological resilience among disaster and crisis responders (Huang et al. 2013). For example, in Snell et al. (2014), ties with family and community are cited as resources for coping and resilience; moreover, the strengthening of these bonds is pointed out by police officers as one of the positive consequences of the disaster. Similarly, from Qiu et al. (2024), it emerged how improving emotional and social contact and decreasing emotional distance is fundamental for the psychological well-being of emergency personnel.

Several studies emphasize different dimensions of social support. Bronisch et al. (2006) highlight the role of personal social ties, through both phone contact with family members during deployments and group cohesion, likewise reported by Dewi et al. (2023) and Celebi Cakiroglu et al. (2025). Similarly, the support and understanding of colleagues (Wang et al. 2013; Maeno et al. 2024; Thormar et al. 2012; Hugelius et al. 2017; Guglielmi et al. 2017) has been widely recognized as essential. However, Mash et al. (2023) found that although support from supervisors and coworkers contributed positively to recovery, the ability to rely on family and close friends had the most profound impact on psychological well-being. In Schenk et al. (2017), disconnection from family or friends appeared as a risk factor for mental health, whereas regular communication with family and supportive team interactions were protective factors. Contrarily, work–family conflict notably increased the risk of psychopathology (Wang et al. 2013) and being criticized by members of the community emerged as a risk factor of distress in Ueda et al. (2017).

Unexpectedly, in McBride et al. (2018), higher perceived social support correlated with higher PTSD, highlighting the complexity of the phenomenon itself. In contrast, in McCanlies et al. (2017), social support negatively correlated with PTSD and resilience significantly mediated the relationship between social support and distress symptoms.

Kaufmann et al. (2020) studied the role of social acknowledgement on volunteers’ mental health and general disapproval emerged as key risk factor for psychopathology, whereas manageability, which refers to a person’s perception of having the internal and external resources (such as training, team support, and personal resilience) needed to cope with challenges and stressful situations, is a significant protective factor. Similarly, Thormar et al. (2016) highlighted how less resilient volunteers report lower social acknowledgement and self-efficacy. Moreover, in Ursano et al. (2014), the role of collective efficacy, defined as social cohesion among neighbors and a willingness to intervene for the common good, in mitigating the stress caused by disaster relief operations, was studied. It emerged that disaster workers living in communities with higher collective efficacy, both at the community level and as individually perceived, had a lower risk and severity of PTSD, suggesting that collective efficacy may promote recovery by fostering a sense of safety, optimism, social support, and shared responsibility, which helps to reduce stress and trauma after disasters.

Blomberg et al. (2024) introduce social support not only as a resilience factor but also as a self-care strategy, highlighting the critical value of informal, peer-based interactions within teams. Krishna and Damle (2017) reached the same conclusions, since emotional support, peer debriefing, buddy care, and walk-around monitoring are reported as recovery facilitators from stress experienced during rescue operations. Similarly, in Mash et al. (2013), positive workplace support perception seems to be linked to team cohesion, emotional reassurance, and workplace flexibility.

4. Discussion

According to this review, the resilience and well-being of the helpers involved in relief efforts from natural hazard events appeared to be affected by many factors, both at an individual level and at a collective/organizational level. In this framework, individual and team empowerment are inseparable. Drawing from this interdependence, international, local, and organizational guidelines and policies should align towards a common goal: protecting workers and volunteers who intervene in emergency situations caused by natural hazard events This can be obtained by strengthening and enhancing the resources available to these individuals. Below, we highlighted the results of the review by addressing the specific research questions identified to conduct this study.

What is the impact of the individual factors of helpers involved in natural hazard events management on their resilience and well-being?

To this primary aim, specific individual traits are more effective than others in preventing mental health impairment. As noted by Fahim et al. (2014), individual perceptions, personal characteristics, and coping strategies mediate resilience, determining how responders engage with crisis. Traits such as altruism, spirituality, hope, and optimism are consistently associated with higher resilience and lower psychopathology (e.g., Ai et al. 2011). On the other hand, certain personality traits, such as neuroticism, anxious disposition, perfectionism, and self-blame, were linked to higher PTSD prevalence (e.g., Ma et al. 2020), suggesting that personality vulnerabilities play a critical role in post-disaster mental health outcomes.

Coping mechanisms also significantly mediate resilience. Some strategies, such as acceptance and planning, are associated with higher resilience and lower PTSD (e.g., Shepherd et al. 2017) than others (e.g., denial, venting, and self-blame), which are linked to increased psychological distress (Huang et al. 2013). Moreover, coping can be interpreted in broader existential and social terms. Responders reported finding meaning and purpose in their work, cultivating appreciation for life, and drawing strength from faith, fate, family, and peer support (Wang et al. 2013). Similarly, Bhushan and Kumar (2012) found that relating to others and proactive coping were related to resilience and post-traumatic growth among helpers. Collecting this type of evidence, which is closely tied to individual characteristics, is particularly valuable during the recruitment process for both staff and volunteers operating in emergency contexts. Moreover, such information provides managers and organizations with crucial insights, allowing them to monitor employees more effectively and to offer enhanced support before and after disasters, especially to those identified as having higher risk factors. Documenting this evidence is also essential for developing targeted informational and training materials for personnel working in these sensitive environments. Additionally, it enables organizations and associations to design well-being and support initiatives tailored to the specific needs of their workforce.

Severe exposure to disaster constitutes a significant risk factor for the mental health of emergency responders too. Generally, lower levels of exposure are associated with more favorable psychological recovery. However, some studies (e.g., Lambert and Lawson 2013; Zachariah et al. 2023) suggest more nuanced findings, indicating that greater exposure, under certain conditions, for example, when it also involves the mutual emotional sharing of experiences between professionals/volunteers and survivors, may also contribute to positive psychological outcomes, such as enhanced resilience and post-traumatic growth.

Organizational policies should consider and internalize this evidence, seeking to meet the specific needs of members and promoting, in general, self-care and functional coping and adaptation strategies. Moreover, reassigning tasks that require greater exposure to disaster and grief on a case-by-case basis could lead to the better preservation of the mental health of workers and promote positive outcomes in relief work.

What is the impact of social or organizational aspects in favor of and empowering the resilience and well-being of helpers involved in natural hazard events management?

However, as was strongly highlighted in this review, the well-being and empowerment of helpers stems not only from a form of individual support, but above all from collective elements relating to training, team cohesion, organizational and social support, and collaboration within and between organizations and institutions. In this scenario, training and preparation emerge from the literature reviewed in this paper as fundamental resources for helpers. Most of the studies that have investigated the impact of training on the resilience and well-being of helpers agree that it is protective for them and for the efficacy of the relief interventions. The finding underscores the importance for policymakers rigorously evaluating the adequacy, relevance, and overall quality of the rescue training programs offered to helpers. A well-designed disaster training program should go beyond technical instruction to address the psychological, emotional, and contextual demands of emergency responses. It should enhance personal resilience, professional competence, and community resilience, while being culturally grounded and responsive to real-world conditions. Moreover, as highlighted by all the organizational issues reported by responders in the analyzed studies, it would be desirable that training programs aim to train helpers as a cohesive group, not just as individuals capable of providing assistance to affected populations, with a view to building a group identity based on shared beliefs and objectives, the achievement of which is founded on mutual trust and collaboration. Within this framework, social support, mutual encouragement, strong intra- and inter-team bonds, recognition of individual roles, and structured yet responsive leadership and coordination emerge as essential components of responders’ resilience and collective empowerment and, in particular, play a crucial role in buffering the adverse effects of disaster work by fostering team-based problem-solving and informal coordination strategies. When teams are collectively empowered, they not only function more effectively on an operational level but also demonstrate greater emotional resilience, especially in contexts where formal support structures are insufficient or absent.

5. Conclusions, Limitations, and Future Directions

This review aims to illustrate and analyze the protective factors of resilience and well-being among helpers who find themselves involved in emergencies caused by natural hazard events. What emerges is that resilience must be strengthened on two fronts: the individual and the organizational–social ones. In fact, forms of individual empowerment, focused, for example, on learning adaptive coping strategies and training in self-care strategies, combined with collective empowerment, based on strengthening intra- and inter-organizational social bonds and team cohesion, are fundamental tools for maintaining resilience and well-being in highly demanding contexts such as emergencies. Obtaining this type of information serves two important purposes. Firstly, it provides guidance to organizations and associations on the recruitment and protection of professional and volunteer staff. Secondly, highlighting the coexistence of aspects related to the individual and aspects related to organizations in the development of resilience among helpers can be useful in guiding future research directions on the topic. In this sense, future research could focus on holistically capturing the dimensions of resilience and well-being among workers, thus including the study of both individual and organizational variables. Alternatively, the same variables that can be studied at the individual level could be analyzed at the team or organizational level, as these are composed of people who share similar affinities and experiences. Further research is needed to investigate these aspects.

This research has several methodological limitations that must be acknowledged. First, the review did not incorporate the gray literature. The gray literature often contains valuable empirical evidence, practical insights, and context-specific findings that may not be represented in peer-reviewed publications. Excluding these sources increases the likelihood of publication bias, as studies reporting null, mixed, or context-dependent results are less likely to appear in academic journals. Consequently, the evidence base considered in this review may be narrower than the actual state of knowledge. Future reviews should integrate the gray literature to achieve a more comprehensive and balanced understanding of the topic. Second, study selection was conducted primarily by a single reviewer, with retrospective verification in doubtful cases by the second author. Although this procedure is consistent with the pragmatic constraints of rapid systematic reviews, it nonetheless introduces a potential risk of selection bias. Relying on one reviewer for the initial screening may lead to inconsistencies in the application of inclusion and exclusion criteria and may limit the thoroughness of the process. Future work would benefit from involving multiple independent reviewers throughout all phases of the study’s selection to enhance reliability and reduce bias. Finally, demographic characteristics (e.g., age, gender, ethnicity, and cultural background) were not included in the analysis. This choice was aligned with the research objectives, which focused on risk and resilience factors and aimed to derive practical implications to support organizational strategies for strengthening the well-being of helpers. Nevertheless, the absence of demographic information limits the ability to contextualize the findings, reduces insight into potential differential effects across subgroups, and restricts the assessment of equity-related considerations. Incorporating demographic variables in future analyses would allow for a more nuanced interpretation of results and support the development of more inclusive and tailored organizational interventions.

In the end, we believe that these insights can guide future work in two main ways. First, they call for multilevel research examining how individual and organizational factors interact over time to shape resilience, including studies that clarify how individual and social empowerment can be effectively promoted. Second, they provide a foundation for targeted and evidence-based interventions that combine individual adaptive coping strategies with organizational and collective empowerment, grounded in stronger intra- and inter-organizational coordination and communication.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/socsci14120708/s1: Table S1: Quality assessment of the eligible studies using the CASP for Qualitative studies Checklist, adapted from the critical appraisal skills program; Table S2: Quality assessment of the eligible studies using the CASP for Cross-Sectional Studies Checklist, adapted from the critical appraisal skills program; Table S3. Quality assessment of the eligible studies using the CASP for Randomized Controlled Trials Studies Checklist, adapted from the critical appraisal skills program; Table S4. Quality assessment of the eligible studies using the MMAT for Mixed Methods Studies Checklist, adapted from the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing, Conceptualization, E.G.; Writing—review and editing, S.M.; Writing—review and editing, M.C., T.G.; Conceptualization, Writing—review and editing, Supervision, A.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This article involved a review of the existing published literature, so no ethical approval was required.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Adams, Terri, Leigh Anderson, Milanika Turner, and Jonathan Armstrong. 2011. Coping through a disaster: Lessons from Hurricane Katrina. Journal of Homeland Security and Emergency Management 8: 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, Amy L., Carol Plummer, Hanae Kanno, Grace Heo, Hoa B. Appel, Cassandra E Simon, and Clarence Spigner. 2011. Positive traits versus previous trauma: Racially different correlates with PTSD symptoms among Hurricane Katrina-Rita volunteers. Journal of Community Psychology 39: 402–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, Amy L., Roslyn Richardson, Carol Plummer, Christopher G Ellison, Catherine Lemieux, Terrence N Tice, and Bu Huang. 2013. Character strengths and deep connections following Hurricanes Katrina and Rita: Spiritual and secular pathways to resistance among volunteers. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 52: 537–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychological Association (APA). 2025. Available online: https://dictionary.apa.org/resilience (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Aporosa, S. Apo, Dennis Itoga, Julia Ioane, Jan Prosser, Sione Vaka, Emily Grout, Martin J. Atkins, Mitchell A. Head, Jonathan D. Baker, Tanecia Blue, and et al. 2025. Innovating through tradition: Kava-talanoaas a culturally aligned medico-behavioral therapeutic approach to amelioration of PTSD symptoms. Frontiers in Psychology 16: 1460731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arena, Andrew F., Mikayla Gregory, Daniel Collins, Bojana Vilus, Richard Bryant, Samuel B. Harvey, and Mark Deady. 2025. Global PTSD prevalence among active first responders and trends over recent years: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review 120: 102622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayalon, Ofra. 2006. Appeasing the sea: Post-tsunami training of helpers in Thailand, Phuket 2005. Traumatology 12: 162–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekircan, Esra, Galip Usta, and Kemal Torpuş. 2024. The effect of psychological first aid intervention on stress and psychological resilience in volunteers participating in 2023 earthquakes centered in Kahramanmaraş, Turkey. Current Psychology 43: 11383–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, Rony, Hisham Abu-Raiya, and Joy Benatov. 2016. Reducing primary and secondary traumatic stress symptoms among educators by training them to deliver a resiliency program (ERASE-Stress) following the Christchurch earthquake in New Zealand. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 86: 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhushan, Braj, and J Sathya Kumar. 2012. A study of posttraumatic stress and growth in tsunami relief volunteers. Journal of Loss and Trauma 17: 113–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blomberg, Karin, Jason Murphy, and Karin Hugelius. 2024. Self-care strategies used by disaster responders after the 2023 earthquake in Turkey and Syria: A mixed methods study. BMC Emergency Medicine 24: 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonanno, George A. 2004. Loss, trauma, and human resilience: Have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events? American Psychologist 59: 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briones, Fernando, Ryan Vachon, and Michael Glantz. 2019. Local responses to disasters: Recent lessons from zero-order responders. Disaster Prevention and Management: An International Journal 28: 119–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronisch, Thomas, Markos Maragkos, Christoph Freyer, Andreas Müller-Cyran, Willi Butollo, Regina Weimbs, and Peter Platiel. 2006. Crisis intervention after the Tsunami in Phuket and Khao Lak. Crisis 27: 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Celebi Cakiroglu, Oya, Gamze Tuncer Unver, and Suleyman Cakiroglu. 2025. Traces of Earthquake: Traumatic Life Experiences and Their Effects on Volunteer Nurses in the Earthquake Zone–An Interpretative Phenomenological Study. Public Health Nursing 42: 899–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetin, Mesut, Samet Kose, Servet Ebrinc, Suat Yigit, Jon D. Elhai, and Cengiz Basoglu. 2005. Identification and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in rescue workers in the Marmara, Turkey, earthquake. Journal of Traumatic Stress: Official Publication of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies 18: 485–89. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Chia-Ming, Li-Ching Lee, Kathryn M. Connor, Jonathan R. T. Davidson, and Te-Jen Lai. 2008. Modification effects of coping on post-traumatic morbidity among earthquake rescuers. Psychiatry Research 158: 164–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Chia-Ming, Li-Ching Lee, Kathryn M. Connor, Jonathan R. T. Davidson, Keith Jeffries, and Te-Jen Lai. 2003. Posttraumatic distress and coping strategies among rescue workers after an earthquake. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 191: 391–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clukey, Lory. 2010. Transformative experiences for Hurricanes Katrina and Rita disaster volunteers. Disasters 34: 644–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristea, Ioana A., Emanuele Legge, Marta Prosperi, Mario Guazzelli, Daniel David, and Claudio Gentili. 2014. Moderating effects of empathic concern and personal distress on the emotional reactions of disaster volunteers. Disasters 38: 740–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. 2024. CASP Checklist. Available online: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/ (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Çakaloğlu, Teslime, Gülseren Keskin, Hande Kekreli Göylüsün, and Kadir Okan Bağiş. 2025. Psychological well-being of search and rescue personnel involved in the Kahramanmaraş earthquakes: An evaluation in terms of resilience. Journal of Health Psychology. advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dass-Brailsford, Priscilla. 2008. After the storm: Recognition, recovery, and reconstruction. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice 39: 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dass-Brailsford, Priscilla, and Rebecca Thomley. 2012. An Investigation of Secondary Trauma Among Mental Health Volunteers after Hurricane Katrina. Journal of Systemic Therapies 31: 36–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewi, Yuli A., Cahyo Seftyono, Koentjoro Soeparno, and Leo Pattiasina. 2023. Psychological Adjustment after the Cianjur Earthquake: Exploring the Efficacy of Psychosocial Support and Collaborative Leadership. E3S Web of Conferences 447: 04002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, Anjali, and Santosh Rangnekar. 2024. Co-Worker Support for Human Resource Flexibility and Resilience: A Literature Review. In Flexibility, Resilience and Sustainability. Singapore: Springer, pp. 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahim, Christine, Tracey O’Sullivan, and Dan Lane. 2014. Supports for health and social service providers from Canada responding to the disaster in Haiti. PLoS Currents 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fekete, Alexander, and Beate Rhein. 2024. More Help Was Offered—But Was It Effective? First Responders and Volunteers in the 2021 Flood Disaster in Germany. Geosciences 14: 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fekete, Alexander Fekete A. 2021. Motivation, satisfaction, and risks of operational forces and helpers regarding the 2021 and 2013 flood operations in Germany. Sustainability 13: 12587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fullerton, Carol S., Jodi B. A. McKibben, Dori B. Reissman, Ted Scharf, Kathleen M. Kowalski-Trakofler, James M. Shultz, and Robert J. Ursano. 2013. Posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and alcohol and tobacco use in public health workers after the 2004 Florida hurricanes. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness 7: 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelkopf, Marc, Pamela Ryan, Sarah J. Cotton, and Rony Berger. 2008. The impact of “training the trainers” course for helping tsunami-survivor children on Sri Lankan disaster volunteer workers. International Journal of Stress Management 15: 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, Adam, Rehana Rasul, Lucero Molina, Samantha Schneider, Kristin Bevilacqua, Evelyn J. Bromet, Benjamin J. Luft, Emanuela Taioli, and Rebecca Schwartz. 2019. Differential effect of Hurricane Sandy exposure on PTSD symptom severity: Comparison of community members and responders. Occupational and Environmental Medicine 76: 881–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guglielmi, Dina, Michela Vignoli, Lucia Camellini, Maria Cristina Florini, Massimo Brunetti, and Marco Depolo. 2017. When helpers need help: A case study on the 2012 earthquakes in Italy. Work 58: 185–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunderson, Lance H., Craig Reece Allen, and Crawford S. Holling, eds. 2012. Foundations of Ecological Resilience. Washington, DC: Island Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gunn, Angus M., ed. 2007. Encyclopedia of Disasters: Environmental Catastrophes and Human Tragedies. 2 vols. London: Bloomsbury Publishing USA. [Google Scholar]

- Hagh-Shenas, Hassan, Mohammad Ali Goodarzi, Gholamreza Dehbozorgi, and Hassan Farashbandi. 2005. Psychological consequences of the Bam earthquake on professional and nonprofessional helpers. Journal of Traumatic Stress: Official Publication of The International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies 18: 477–83. [Google Scholar]

- Heavey, Sarah Cercone, Gregory G. Homish, Michael E. Andrew, Erin McCanlies, Anna Mnatsakanova, John M. Violanti, and Cecil M. Burchfiel. 2015. Law enforcement officers’ involvement level in Hurricane Katrina and alcohol use. International Journal of Emergency Mental Health 17: 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Quan Nha, Pierre Pluye, Sergi Fàbregues, Gillian Bartlett, Felicity Boardman, Margaret Cargo, Pierre Dagenais, Marie-Pierre Gagnon, Frances Griffiths, Belinda Nicolau, and et al. 2018. Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), version 2018. Registration of Copyright (#1148552), Canadian Intellectual Property Office, Industry Canada. Available online: http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com/w/file/fetch/127916259/MMAT_2018_criteria-manual_2018-08-01_ENG.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Hsiao, Yin Ying, Wei Hung Chang, I Chun Ma, Chen-Long Wu, Po See Chen, Yen Kuang Yang, and Chih-Hao Lin. 2019. Long-term PTSD risks in emergency medical technicians who responded to the 2016 Taiwan earthquake: A six-month observational follow-up study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16: 4983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Junhua, Qunying Liu, Jinliang Li, Xuejiang Li, Jin You, Liang Zhang, Changfu Tian, and Rongsheng Luan. 2013. Post-traumatic stress disorder status in a rescue group after the Wenchuan earthquake relief. Neural Regeneration Research 8: 1898–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hugelius, Karin, Annsofie Adolfsson, Per Örtenwall, and Mervyn Gifford. 2017. Being both helpers and victims: Health professionals’ experiences of working during a natural disaster. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine 32: 117–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC). 2007. IASC Guidelines on Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Emergency Settings. Geneva: IASC. [Google Scholar]

- Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC). 2011. Operational Guidelines on the Protection of Persons in Situations of Natural Disasters. Hanover: Brookings-Bern Project on Internal Displacement. [Google Scholar]

- Iseri, Ali, and Recep Baltaci. 2024. Psychological Impact of Disaster Relief Operations: A Study Following Consecutive Earthquakes in Turkey. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness 18: e128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, Danielle, Sarah Harrison, Céline Cattoën, Jordan Luttrell, and Paula Blackett. 2025. ‘That still haunts me a little bit’: Decision-makers and information providers’ experiences of recurring flood events. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 118: 105216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Peng, Yipeng Lv, Lu Hao, Bihan Tang, Zhipeng Liu, Xu Liu, Yuan Liu, and Lulu Zhang. 2015. Psychological consequences and quality of life among medical rescuers who responded to the 2010 Yushu earthquake: A neglected problem. Psychiatry Research 230: 517–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, Milena, Matthias Gelb, and Mareike Augsburger. 2020. Buffering PTSD in canine search and rescue teams? Associations with resilience, sense of coherence, and societal acknowledgment. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17: 6184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]