Abstract

This study investigates how Italian and American media frame climate change through politically oriented and, in some cases, populist narratives that challenge the principles of the open society. The analysis draws on a dataset of 71 items from eight outlets, evenly divided by country and political alignment, collected from Facebook posts that generated at least forty comments. A mixed-methods design was employed, including keyness analysis, topic modeling, keyword-in-context exploration, and qualitative content analysis. The findings show clear cross-national and ideological differences: conservative sources rely more heavily on politicized and populist framings, particularly in the U.S., where climate change is frequently narrated through an antagonistic “elites versus ordinary citizens” lens associated with skepticism toward scientific authority and sustainable technologies. Italian media display a more technocratic approach, emphasizing institutional, economic, and policy dimensions within the European context. Progressive sources in both countries rely more consistently on scientific and policy-oriented arguments, although American progressive outlets show higher political engagement than their Italian counterparts, likely in response to the stronger populist rhetoric and distrust of expertise found in U.S. conservative media. Overall, the results highlight how populist narratives can shape climate communication and influence the openness of public debate in different democratic contexts.

1. Introduction

Climate change appears as a significantly polarized topic, especially in the U.S. (Merry 2024). Zehr (2000) argues that acknowledging uncertainty within scientific expertise may weaken its perceived authority and allow competing actors to challenge it, particularly in the media, where this contributes to a divide between science and the public.

Political polarization appears closely tied to partisanship. Democrats are generally more aligned with the scientific community than Republicans (McCright and Dunlap 2011), while right-wing individuals tend to show stronger factual belief polarization, interpreting scientific evidence through ideological filters (Kossowska et al. 2023; Rekker and Harteveld 2024). Right-wing communication also tends to portray environmentalists as threats, using hostile metaphors such as “Nazis” or “terrorists” (Hoffarth and Hodson 2016). Elite cues further amplify these divides (Guber 2013).

Populist attitudes, especially those linked to the elite, further seem to reinforce this polarization. They also challenge the principles of the open society (Popper 1945), which rely on critical thinking, pluralism, and democratic mechanisms for peaceful reform. By framing political and scientific institutions as self-interested elites opposed to ordinary citizens, populist and antagonistic narratives risk narrowing the space for democratic deliberation. Hofmann (2024) identifies right-wing populism as a key predictor of conspiracy beliefs, while Kulin (2024) links it to whataboutism and climate inaction unless other countries act first. Huber et al. (2020) suggest that populist narratives can weaken trust in scientific and political institutions, thereby reducing support for climate policies among populist Republicans. By contrast, populist Democrats tend to express higher support when policies are perceived as fair and inclusive. This reflects the populist framing of elites as acting against the people (Hawkins and Rovira Kaltwasser 2017), suggesting that fairness perceptions may reduce institutional distrust. On the other hand, Swyngedouw (2010) argues that contemporary environmental governance is dominated by post-political and technocratic logics, framing climate change as a technical issue managed by experts rather than a matter of ideological debate. This depoliticized approach may enhance efficiency but limits democratic deliberation and alternative perspectives.

This study adopts a Science and Technology Studies framework, drawing on Actor-Network Theory (ANT). As Jasanoff (2003, 2004) notes, scientific knowledge may in fact operate as both a means of governance and conflict and a site where science and political order are co-produced. Besel’s (2011) notion of climate change as a “black box” of consolidated scientific knowledge is also central to this research. When such knowledge is questioned in the public sphere, its stability is challenged, opening space for renewed debate in which rhetoric plays a key role in shaping the actor-network. The study explores how media discourse constructs public understandings of climate change and whether populist narratives contribute to this framing.

The research questions are as follows:

RQ1.

Are the media narratives regarding climate change politicized in both countries?

RQ2.

If so, how does the political orientation of sources influence the language and rhetoric of the media sources and shape the main differences between the two countries? In particular, do they employ populist or anti-elitist framings that affect the openness of public debate?

RQ3.

What are the issues that capture media interest the most?

RQ4.

Which human actors and factors are the most prominent in media discourse, and how are they framed in relation to institutional trust, expertise, or political conflict?

We employed a mixed-methods design. A keyness analysis addresses RQ1 and RQ2 by identifying politicized linguistic patterns, while topic modeling highlights the major themes and actors (RQ3 and RQ4). The cross-country comparison (RQ2) is further examined through topic modeling, a keyword-in-context (KWIC) analysis and a Qualitative Content Analysis (QCA), providing deeper insight into rhetorical and narrative structures.

The article proceeds as follows: the next section presents materials and methods, followed by the results and a discussion on their broader socio-political implications.

2. Materials and Methods

Given that the U.S. represents a paradigmatic case of ideological polarization, where climate change has become a partisan identity issue (McCright and Dunlap 2011), this study therefore adopts a comparative design focusing on Italy, situated within the EU’s policy framework and more in line with Swyngedouw’s (2010) perspective, and the U.S. The two countries also differ structurally in their media systems, with the U.S. following a liberal pluralist model and Italy a polarized pluralist one (Hallin and Mancini 2016). Comparing the two cases allows for a more detailed examination of the extent to which the politicization of climate communication is shaped by media framing, ideological polarization, and populist discourse.

The study draws on media content from four Italian and four U.S. outlets. The Italian sample includes Il Sole 24 Ore and Libero Quotidiano (conservative) and Il Post and La Repubblica (progressive); the American sample includes Breitbart and The Daily Caller (conservative) and The New York Times and The Washington Post (progressive). The eight sources were selected because of their wide reach and relevance in their respective countries. They include established newspapers and influential media producers that play a significant role in shaping public opinion, including through social media and Facebook in particular.

A total of 71 items were collected and analyzed (36 from Italy and 35 from the U.S.), evenly distributed by political orientation (18 progressive and 18 conservative for Italy; 18 progressive and 17 conservative for the U.S., as one Daily Caller post was unavailable), amounting to 25,745 words. The dataset was retrieved from Facebook to examine the mechanisms of politicization in the dissemination of content and includes news articles shared through posts as well as original captions accompanying images or short videos. All items were published between October 2023 and June 2024 and generated at least forty comments to ensure comparable levels of public engagement. The corpus was constructed using the keywords “climate change,” “ecoactivism,” “ecoactivists,” “ecologism,” “ecoterrorism,” “ecoterrorists,” “environmentalism,” “Green Deal,” “sustainability,” and “sustainable development.” These keywords were intentionally selected not to capture the full climate coverage of each outlet, but to identify segments of discourse where political conflict, polarization, or potentially populist narratives are more likely to emerge.

The items were saved in .txt format, including the title, full text, and, when applicable, subheadings or captions for posts and short videos. The files were imported into R (R Core Team 2021) and processed with the Quanteda package (Benoit et al. 2018). Standard preprocessing removed both standard and user-defined stopwords, as well as words occurring fewer than five times and those shorter than three characters.

We applied a mixed-methods approach to explore the polarization of climate discourse in the media and to identify the key actors and narratives involved.

A keyness analysis was first conducted to highlight words that occur with statistically significant frequency (Chen 2023) in conservative versus progressive media sources. This step allowed for the identification of distinctive rhetorical and terms and provided an answer to RQ1 and RQ2.

Subsequently, topic modeling was performed to identify latent themes (Murel and Kavlakoglu n.d.) and main actors in both countries’ discourse. This technique addressed RQ3, RQ4, and added further insights to RQ2, with regard to the major differences between Italy and the U.S.

Finally, a keyword-in-context (KWIC) analysis supported the qualitative phase of the study providing the base for a Qualitative Content Analysis (QCA). Specific keywords related to science and politics were selected and examined in context to better understand how these concepts were articulated across politically oriented sources (Fobbe 2024). The subsequent QCA ensured a qualitatively detailed interpretation of the results (Mayring 2014), providing a deeper understanding of RQ2. Both steps were carried out with MAXQDA, a software for qualitative and mixed-methods data analysis (VERBI Software 2021).

Taken together, these methods are intended to complement and reinforce one another: keyness identifies lexical differences, topic modeling allows key themes and actors to emerge, KWIC analysis provides contextualization of selected terms, and QCA offers a comprehensive and detailed qualitative interpretation that enriches the quantitative analyses.

3. Results

It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

3.1. Keyness Analysis

To address RQ1 (politicization of climate change) and RQ2 (how the political orientation of sources influences their language and rhetoric), a keyness analysis was performed based on the political orientation of sources from each country. The analysis aimed to identify the words most likely to appear in each group, with Italian terms accompanied by their English translations.

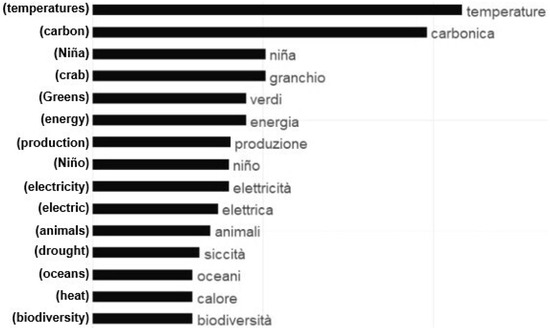

Figure 1 illustrates the 15 keywords with the highest keyness in progressive sources, which appear to predominantly concern scientific and environmental matters. Terms such as “temperatures,” “Niña,” “Niño,” and “drought” suggest that the discourse may focus on technical aspects of climate and weather, including extreme phenomena. Energy-related issues also seem relevant, as indicated by “energy,” “production,” and “electricity.” References to biodiversity and fauna, including “biodiversity,” “crab,” and “animals,” further suggest attention to ecological dimensions. Political references are limited and appear primarily linked to environmental contexts, particularly the 2024 European elections, where the Green Party is the only explicit mention.

Figure 1.

Keyness of Italian progressive sources. The plot displays the top 15 key terms. The horizontal axis represents chi2 values.

Figure 2 indicates that content from Italian conservative sources may be more oriented toward political and economic aspects. Technological themes are also present, as suggested by references to cloud seeding (“nuvole,” “semina”). The terms “Meloni,” “left,” and “government” imply that climate-related issues might be framed through political lenses intersecting with economic considerations. The prominence of “capitalism,” along with “labor,” “NRRP” (National Recovery and Resilience Plan), and “market,” points to an economic interpretation of climate discourse, which also appears to incorporate social dimensions such as “wealth” and “inequalities,” potentially reflecting concerns over disparities in access to environmental resources and policies.

Figure 2.

Keyness of Italian conservative sources. The plot displays the top 15 key terms. The horizontal axis represents chi2 values.

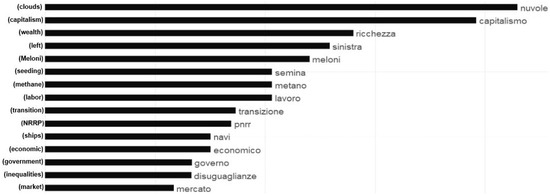

Figure 3 presents the American sample, where a pattern similar to the Italian case can be observed. On the left side, the keywords from progressive sources appear predominantly focused on scientific and technical aspects of climate change, including “heat,” “ice,” “temperatures,” “atmosphere,” and “carbon.” The term “Mann” likely refers to climatologist Michael E. Mann, IPCC author and shared recipient of the 2007 Nobel Peace Prize; its occurrence may relate to media coverage of his lawsuit against two right-wing bloggers accused of defamation (The Guardian 2024). Mentions of “E.P.A.” (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency) and “scientists” suggest that the discourse may address not only scientific and research-oriented issues but also the defense of scientific credibility against politically motivated skepticism. The presence of “batteries,” “vehicles,” and “cars” indicates possible attention to electric mobility and its role in climate mitigation.

Figure 3.

Keyness of American progressive (left) and conservative (right) sources. The plots display the top 15 key terms. The horizontal axis represents chi2 values.

On the right side of the figure, the discourse in conservative American media appears more politically and economically oriented. The keyword “offshore” may refer to large-scale wind energy investments, particularly in California, supported by “wind,” “DOE” (U.S. Department of Energy), and “contracts.” References to “Bezos” and “yacht” might point to critiques of wealthy elites, while “food” could relate to debates on sustainable food systems, potentially reflecting concerns about social and economic inequality. The mention of Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell may be linked to his statement that climate policy lies within the competence of elected officials rather than the Fed (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System 2023). The appearance of “ChatGPT” could be associated with claims that the tool favors environmental policies or reproduces mainstream scientific perspectives (Williams 2024). The term “painting” likely refers to acts of climate activism involving artworks, whereas “Roman” and “plague” may evoke historical analogies employed in climate-related narratives.

Overall, these findings contribute to addressing RQ1 and RQ2, suggesting that in both countries progressive media tend to emphasize scientific and environmental aspects, whereas conservative outlets may frame climate change primarily through political and economic perspectives. This pattern appears to support the presence of politicization in climate discourse and highlights significant differences in language and rhetoric across political orientations, particularly in the American context.

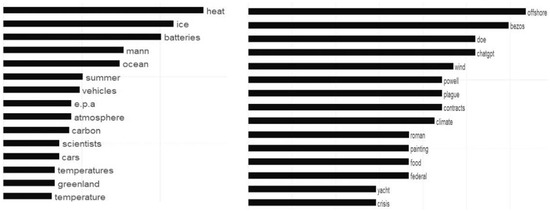

3.2. Topic Modeling

To investigate the major differences between the two countries analyzed (RQ2), the main issues covered by the media sources (RQ3), and the principal human actors and factors involved in the discourse (RQ4), topic modeling was applied to the Italian and U.S. media samples to examine public opinion formation. A Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) model, a probabilistic approach that treats words and documents as exchangeable (Del Gobbo et al. 2021), was implemented through the “textmodel_lda” function of the quanteda package in R to identify latent thematic structures. The model was estimated with ten topics, selected after initial exploratory runs. For each topic, twenty terms were extracted to provide an overview of its main lexical components, and English translations were added for the Italian outputs.

Table 1 displays the topics related to the Italian sample from 1 to 5.

Table 1.

Topic modeling results, Italian media (Topic 1–Topic 5).

Topic 1 focuses on pollution and weather conditions, with “Niña,” “Niño,” and “temperatures” indicating attention to emissions and environmental impacts. “Cars,” “traffic,” and “pollutants” suggest concern with transport and air quality, while “soil,” “waters,” and “drought” may extend the focus to environmental degradation. References to “Paris,” “Europe,” and “law” point to calls for European regulation, and “study” indicates scientific grounding.

Topic 2 seems to address the ecological transition in its technological, political, and social dimensions. “Nuclear,” “gas,” and “electricity” highlight debates on sustainable energy, while “labor,” “Meloni,” “NRRP,” and “COP28” likely link the issue to national and international policy. Mentions of “Enel,” “France,” and “emissions” suggest coordination between domestic measures and European strategies. “Generation” and “security” may refer to the group Last Generation and its contested activism.

Topic 3 appears to center on environmental activism, particularly actions by Last Generation. Terms such as “security,” “Gucci,” “gallery,” and “paint” indicate coverage of protests often framed as public order concerns. “Government” may relate to both political responses and activist demands, while “fossil” points to opposition to fossil fuels as a recurring theme.

Topic 4 tends to focus on weather conditions, as shown by “temperatures,” “rains,” and “snow.” “Drought” may emphasize extreme weather, while “Copernicus” and “preindustrial” link to historical climate data, suggesting an institutional and empirical framing of climate history.

Topic 5 may concern sustainable mobility and the socio-economic aspects of the green transition. “Railway,” “vehicles,” and “decarbonization” indicate focus on transport, while “capitalism,” “wealth,” and “inequalities” reflect attention to the social impact of transition policies. “Politics,” “European,” and “resources” link the discussion to the EU, and “data” and “report” suggest references to research evidence.

Table 2 displays the topics from 6 to 10.

Table 2.

Topic modeling results, Italian media (Topic 6–Topic 10).

Topic 6 seems to focus on climate research and technological mitigation strategies. “CO2,” “emissions,” “methane,” and “electric” suggest attention to alternative fuels and sustainable transport, while “pyrolysis” and “costs” indicate interest in energy production from waste and its economic implications. The topic reflects a technology-oriented approach to climate solutions.

Topic 7 concerns biodiversity loss and ecosystem protection. “Crabs,” “insects,” and “plants” point to species preservation, likely in Mediterranean contexts. “Data,” “research,” and “studies” indicate a scientific framing, while “gardens” and “Milan” suggest urban greening initiatives. “Risk” and “mass” may link biodiversity concerns to activism.

Topic 8 tends to address European political dynamics, particularly the 2024 elections. “Parliament,” “parties,” and “Greens” suggest attention to electoral debates on environmental issues, while “farmers” likely refers to the 2024 protests across Europe. Mentions of “government” and “minister” appear limited, supporting a predominantly supranational framing.

Topic 9 seems to focus on precipitation and extreme weather, especially drought, with “Sicily” and “farmers” suggesting regional vulnerability and agricultural impacts. “Cloud,” “seeding,” and “Dubai” likely point to interest in weather modification technologies.

Topic 10 appears to compare fossil fuels and renewables, as indicated by “renewables,” “solar,” “coal,” and “electricity.” “Emissions” likely links the topic to sustainability and clean transport, while “China,” “COP28,” and “researchers” suggest international and scientific perspectives in environmental policymaking.

Overall, the Italian media discourse appears broad and multi-dimensional, with a stronger focus on European and international policies than on domestic politics. Renewable energy and sustainable mobility, particularly in relation to carbon dioxide emissions, emerge as central themes. Research is also consistently present (Topics 1, 5, 6, 7, 9, and 10), with references to the EU’s Copernicus program in Topic 4. Notably, research is portrayed mainly through practical and technological applications, while environmental activism tends to be framed through security concerns.

Moving to American media content, Table 3 displays the topics from 1 to 5.

Table 3.

Topic modeling results, American media (Topic 1–Topic 5).

Topic 1 focuses on the effects of climate change on glaciers and sea levels, as indicated by “ice,” “ocean,” and “glaciers.” The discussion likely concerns Antarctic and Greenland ice melt and its impact on the Atlantic Ocean, with “freshwater” pointing to water scarcity. References to “scientists,” “research,” and “gigatons” suggest a scientific framing, while “space” and “meteorites” may indicate interest in satellite monitoring.

Topic 2 is politically and policy oriented, centered on the Democratic administration, as suggested by “Biden,” “president,” and “campaign.” Mentions of the “E.P.A.,” “emissions,” and “regulations” indicate an emphasis on climate policy and air quality, while “electric,” “vehicles,” and “cars” point to attention to clean mobility within the governmental agenda.

Topic 3 focuses on climate education, as shown by “school,” “teachers,” and “students.” The recurrence of “science,” “scientific,” and “study” points to the educational role of scientific knowledge. “ChatGPT” may relate to debates on AI alignment with mainstream science, and “Roman” and “plague” possibly serve as historical references in climate discourse.

Topic 4 concerns weather conditions, reflected in “temperatures” and “record,” with “scientists,” “Copernicus,” and “preindustrial” likely referring to climate history. Mentions of “travel,” “Paris,” and “Athens” may connect climate change with tourism, while “fossil” and “fuels” may indicate discussion of the environmental costs of travel.

Topic 5 appears to address the policymaking dimension of the energy transition, with “economic,” “political,” and “November” likely linking it to the electoral context. References to “DOE,” “federal,” and “policies” locate the debate at the national level, while “Powell,” “Europe,” and “gas” suggest intersections between economic policy, international comparisons, and energy costs. “Security” and “report” indicate broader social and informational considerations.

Table 4 displays topics from 6 to 10.

Table 4.

Topic modeling results, American media (Topic 6–Topic 10).

Topic 6 focuses on wind energy, particularly offshore turbines, as indicated by “wind,” “offshore,” and “turbines.” The emphasis on California and New Jersey likely reflects their investment in this sector. “Costs” and “power” point to efficiency and infrastructure, while “company,” “contracts,” and “rates” suggest a commercial and regulatory framing.

Topic 7 seems to compare fossil fuels and renewable energy sources, with “electricity,” “solar,” and “wind” contrasted to “coal” and “gas.” The focus appears economic and technological, revolving around cost–benefit and performance aspects, as reflected by “costs,” “companies,” “power,” “batteries,” and “storage.”

Topic 8 is mainly research-oriented, as suggested by “science,” “university,” and “scientists.” “Rotation” and “hockey” likely allude to the hockey stick graph, supported by the mention of “Mann” and his “court” case against climate denialists. Mentions of “plants,” “pools,” and “backyard” may point to research applications in urban sustainability.

Topic 9 tends to center on climate science and air pollution, as suggested by “CO2,” “greenhouse,” “atmosphere,” and “emissions.” “Experts,” “scientists,” and “research” highlight the role of expert knowledge, while “beef,” “gases,” “land,” and “water” suggest attention to livestock-related emissions. The reference to “Climeworks” indicates interest in carbon removal technologies.

Lastly, Topic 10 focuses on environmental activism, with references to the Riposte Alimentaire protest at the Louvre (“painting,” “soup,” “Mona Lisa”). “Security” and “attack” suggest a framing of activism as a public order issue. The link between “food,” “fund,” “Bezos,” and “meat” points to sustainable food initiatives tied to elite figures, possibly reflecting narratives that associate environmental issues with elite interests.

Overall, the analyzed American media sample appears to focus primarily on science, research, and climate education (featured in Topics 1, 3, 4, 8, and 9, with smaller references in Topic 5); on renewable energy sources and their comparison with fossil fuels (Topics 4, 5, 6, and 7); on emissions and air pollution (Topics 2 and 9); and on environmental policymaking (Topics 2 and 5). Elite criticism emerges as closely connected to environmental activism (Topic 10), suggesting that the delegitimization of environmental concerns can be framed within a broader discourse of elite criticism.

In conclusion, American media content appears more politically oriented than Italian coverage, which tends to focus more on European policymaking. Research references are more frequent in U.S. media and include theoretical aspects, whereas Italian coverage emphasizes technological applications. Both discuss climate history, though climate education appears only in the American sample. Renewable energy appears central in both, while electric vehicles seem to receive greater attention in Italian outlets. Sustainable food, by contrast, is largely absent from Italian discourse. In both contexts, environmental activism is framed through security narratives, and concerns over wealth inequalities emerge, though they appear more politicized in the American sample through the “elite vs. people” frame. Denialism appears to be limited to the American content, emerging mostly indirectly, such as through references to the Mann defamation case.

3.3. Kwic Analysis and Qca

To provide a detailed perspective on RQ2 (differences between the two countries), a KWIC analysis and a QCA were conducted on all items in the dataset. The analysis included titles, subheadings (where available), article bodies, and captions for posts and short videos.

Based on the keyness and topic modeling analyses, a set of keywords related to science and politics was identified for each country, with additional terms associated with populism to explore their presence in media discourse.

In the Italian case, the keywords were: “agricoltori” (farmers), “attivist*” (activist*), “COP28,” “destra” (right), “elite*/élite*,” “espert*” (expert*), “Europa/europe*” (Europe/European), “Generazione” (Generation, referring to the activist group Last Generation), “governo” (government), “Meloni,” “mercato” (market), “negare/negazionis*” (deny/denial*/denier*), “politic*,” “popol*” (people*), “populism*,” “ricerc*” (research), “ricercat*” (researcher*), “scettic*” (skeptic*), “scientific*” (scientific), “scienz*” (science*), “scienziat*” (scientist*), “sinistra” (left), “sovran*” (sovereign*), “studio/studi” (study/studies), “Verdi” (Greens).

For the U.S., the keywords were: “activist*,” “Bezos,” “Biden,” “celebrit*,” “conservative*,” “Democrat*,” “denial*/denier*/deny,” “DOE,” “elite*,” “E.P.A./EPA,” “Europe/European*,” “expert*,” “globalis*,” “left,” “liberal*,” “Mann,” “people*,” “politic*,” “populism*,” “president,” “protester*,” “Republican*,” “research,” “researcher*,” “right,” “science*,” “scientific,” “scientist*,” “skeptic*,” “sovereign*,” “study/studies,” and “Trump.”

For both analyses, a 10-word window before and after each keyword was selected to provide comprehensive context.

For Italian content, MAXQDA extracted 323 associations through the “Keyword in Context” function. After the removal of 202 irrelevant entries, the final dataset included 116 associations (56 from progressive and 60 from conservative sources). For the U.S., MAXQDA produced 526 associations; after manually excluding 332 irrelevant entries, the final dataset comprised 190 associations (119 from progressive and 71 from conservative sources).

A manual coding process was conducted for each country using MAXQDA. The cleaned Italian KWIC dataset was imported for analysis. Three macro-categories were defined from the main themes: “Political Behavior,” “Science and Expertise,” and “Social Behavior,” each subdivided inductively through close reading.

“Political Behavior” included four subcodes: “(De)politicization of Climate Issues,” “European and International Politics,” “Ideological Narratives,” and “Partisanship and Political Conflict.”

“Science and Expertise” comprised “Data and Research,” “Distrust in Science/Climate Skepticism,” “Extreme Weather Events,” and “Sustainable Technologies and Clean Energy.”

“Social Behavior” included “Activism and Collective Action,” “Economic Dimensions,” and “Public Opinion.”

These codes could be used simultaneously within the same association to capture all potentially present dimensions.

“Political Behavior” was the most frequent macro-category, with 73 coded segments, followed by “Social Behavior” (56) and “Science and Expertise” (53). Within “Political Behavior,” “Ideological Narratives” (27) and “(De)politicization of Climate Issues” (21) were the most recurrent subcodes, while “Partisanship and Political Conflict” (13) and “European and International Politics” (12) appeared less often. “Social Behavior” mainly concerned “Activism and Collective Action” (32), whereas “Sustainable Technologies and Clean Energy” (25) and “Data and Research” (19) were prevalent in “Science and Expertise.”

Considering political orientation, progressive sources accounted for 75 coded segments and conservative ones for 107. Conservative outlets were particularly active under “Political Behavior” (52), especially in “Ideological Narratives” (24) and “(De)politicization of Climate Issues” (17). Progressive media, by contrast, concentrated on “Science and Expertise” (34), especially “Data and Research” (16) and “Sustainable Technologies and Clean Energy” (13). References to “Extreme Weather Events” were limited across both groups, as well as those to distrust in science, suggesting that overt denialist framings were not a main feature of the analyzed content.

Overall, these findings appear consistent with the quantitative analyses. Conservative content seems more politically framed, as indicated by the prevalence of “Political Behavior,” while progressive sources focus more on scientific and technological issues, in line with the keyness results.

The differences in approaching these two specific categories also deserve a more detailed look.

Conservative outlets tend to focus primarily on “Ideological Narratives” (24) and “(De)politicization of Science” (17). Progressive sources, by contrast, appear to emphasize “European and International Politics” (8), particularly in relation to EU environmental policy, while “(De)politicization of Climate Issues” (4) and “Ideological Narratives” (3) are less central. Attention to partisanship does not seem relevant for either orientation (7 and 6).

Differences also emerge in the approach to “Science and Expertise.” Progressive sources most often use “Data and Research” (16), showing references to empirical evidence, while conservative outlets focus more on “Sustainable Technologies and Clean Energy” (12). Progressive media also address this theme (13), which is in line with the topic modeling results suggesting the prominence of technological and energy issues in Italian discourse.

Conservative sources engage more frequently with “Social Behavior,” particularly “Activism and Collective Action” (21). This may reflect a framing of activism as a security concern or within an ideological lens, consistent with the prominence of “Ideological Narratives.” Progressive sources also address activism, though less frequently (11). “Economic Dimensions” are more frequent in conservative outlets (12 versus 4), consistent with their greater focus on market and policy implications, whereas “Public Opinion” remains marginal (3 and 5).

Switching to American content, the cleaned KWIC file was imported into MAXQDA for coding. To ensure comparability, the same macro-categories and subcodes used in the Italian analysis were applied, with one exception: “European and International Politics” was replaced by “Presidential Climate Regulations” to better capture the features of U.S. climate politics. As in the Italian analysis, codes could be applied simultaneously within the same segment.

A total of 276 code applications were assigned to the American material, 180 from progressive and 96 from conservative sources. “Political Behavior” was the most frequent macro-category, with 129 coded segments, followed by “Science and Expertise” (108) and “Social Behavior” (39). Within “Political Behavior,” “(De)politicization of Climate Issues” (48) and “Partisanship and Political Conflict” (32) were the most recurrent subcodes, while “Ideological Narratives” (22) and “Presidential Climate Regulations” (27) appeared slightly less often. “Science and Expertise” mainly included “Data and Research” (44) and “Sustainable Technologies and Clean Energy” (35), whereas “Distrust in Science/Climate Skepticism” (22) and “Extreme Weather Events” (7) were less frequent. “Social Behavior” referred mostly to “Activism and Collective Action” (16).

Progressive sources accounted for 79 code applications within “Political Behavior”: 33 for “(De)politicization of Climate Issues,” 6 for “Ideological Narratives,” 26 for “Partisanship and Political Conflict,” and 14 for “Presidential Climate Regulations.” Science and Expertise” reached the same total (79): 35 for “Data and Research,” 14 for “Distrust in Science/Climate Skepticism,” 7 for “Extreme Weather Events,” and 23 for “Sustainable Technologies and Clean Energy.” “Social Behavior” appeared 22 times, with 6 for “Activism and Collective Action,” 10 for “Economic Dimensions,” and 6 for “Public Opinion.” “

In conservative sources, the codes were more concentrated under “Political Behavior” (50): 15 for “(De)politicization of Climate Issues,” 16 for “Ideological Narratives,” 6 for “Partisanship and Political Conflict,” and 13 for “Presidential Climate Regulations.” “Social Behavior” occurred 17 times, with 10 for “Activism and Collective Action,” 3 for “Economic Dimensions,” and 4 for “Public Opinion.” “Science and Expertise” was applied 29 times: 9 for “Data and Research,” 8 for “Distrust in Science/Climate Skepticism,” and 12 for “Sustainable Technologies and Clean Energy.” No segment was coded with “Extreme Weather Events.”

These results seem to support the quantitative findings. Progressive sources display a higher number of associations and coded segments, which may indicate a stronger emphasis on scientific themes already suggested by the keyness analysis. The frequent use of “(De)politicization of Climate Issues” (33) and “Partisanship and Political Conflict” (26) tends to refer to defenses of scientific expertise against politically motivated criticism, contributing to explaining this balance between “Political Behavior” and “Science and Expertise.”

Conservative outlets, by contrast, show a more concentrated use of “Political Behavior” (50), particularly through “Ideological Narratives” (16) and “(De)politicization of Climate Issues” (15). The comparatively lower frequency of “Science and Expertise” (29) and “Data and Research” (9), together with the absence of “Extreme Weather Events,” may suggest a weaker focus on scientific aspects and stronger ideological and political framings. The keyness results support this interpretation, with “Roman” and “plague” likely referencing historical analogies used to normalize climate issues.

The prominence of “Data and Research” in progressive content (35) supports their scientific orientation, while the focus on “Sustainable Technologies and Clean Energy” (12) in conservative sources suggests interest in the political and economic aspects of the green transition. The coexistence of “Ideological Narratives” and elite-related criticism, including references to sustainable food production, further indicates that conservative discourse on environmental technologies may be intertwined with broader political and economic considerations.

In conclusion, in both Italy and the U.S., content from conservative sources tends to display a stronger political connotation than that from progressive ones. Some relevant differences, however, emerge across the two contexts. In Italy, progressive outlets appear comparatively less politicized, as their discourse is more oriented toward scientific data and European environmental policies, suggesting a preference for empirical and institutional framings of climate change.

The American case differs. Progressive sources appear more openly politicized, often engaging with partisan dynamics when addressing climate skepticism. This may reflect the stronger association between skepticism and political identity in the U.S., where climate change tends to be debated as a partisan issue rather than as a matter of scientific consensus.

In both countries, sustainable innovation appears closely linked to political and institutional measures, with the EU in Italy and presidential regulations in the U.S., suggesting that the green transition is largely framed as a political process shaped by decision-making institutions.

In Italy, particularly among conservative sources, this link also takes on an economic dimension, as market implications appear emphasized. In the U.S., conservative outlets likewise refer to economic aspects, though less extensively, which may reflect a higher degree of politicization, where political conflict tends to overshadow alternative or economically positive perspectives.

These differences align with the broader prominence of ideological narratives in American content, while in Italian discourse they appear mainly connected to eco-activism. Activism itself is more visible in Italian media, often politically framed, whereas in the American case it seems marginal.

Overall, Italian discourse appears broader, more varied, and less politicized than the American one, consistent with the results of the quantitative analyses.

4. Ant Analysis of Climate Controversies

The results are interpreted through the lens of Actor-Network Theory to examine how the analyzed media construct narratives around climate change.

Following Besel’s (2011) view of climate change as a black box, the findings suggest that its reopening is driven mainly by conservative media outlets, particularly in the U.S. These outlets seem not only to promote alternative narratives of climate change but also challenge, to some extent, established scientific positions.

Political interpretations appear prominent, suggesting that climate science may be framed within broader political and economic considerations. The QCA seems to support this tendency, as the limited use of science-related codes indicates a possible preference for politically oriented framings.

A further perspective is provided by Kukkonen et al.’s (2020) framework of justificatory logics networks, which, when applied to topic modeling, helps illustrate how various logics may relate to the actors involved.

Italian sources display a diverse landscape of justificatory logics. Topic 1 suggests a primarily scientific-institutional orientation centered on data and pollutants, while references to the EU, the Paris Agreement, and legal frameworks also indicate a political dimension focused on governance. Topic 2 seems to combine economic–political and technological considerations, oriented toward cost–benefit evaluations of energy sources, and social justice elements linked to labor and activism. Topic 3 indicates a mix of social justice and political-delegitimizing logics, where activism is framed as a security issue requiring institutional intervention.

Topics 4 and 7 seem more consistent with a scientific-institutional logic emphasizing meteorological and empirical data. Topic 5 appears to combine economic–political, social justice, and technological justifications, reflecting attention to market dynamics, inequalities, and decarbonization.

Topic 6 appears to integrate scientific, technological, and economic dimensions, focusing on research, emissions reduction, and cost considerations. Topic 8 seems predominantly political, relating to European elections and the role of Green Parties, and may frame climate change as a collective political responsibility. Lastly, Topics 9 and 10 tend to merge scientific and technological logics concerning meteorological data, cloud seeding, and renewables, with potential agricultural implications.

Overall, Italian discourse integrates economic–political, scientific, and technological justifications.

In the American sample, a different configuration emerges. Topic 1 reflects a scientific-institutional logic focused on data and observation, while Topic 3 similarly appears to center on climate education within formal institutions. Topic 2 seems to combine political and technological logics tied to the Biden administration and climate regulation, highlighting the link between sustainable innovation and presidential policymaking and pointing to the partisan dimension of climate discourse in the United States.

Topic 4 again appears to emphasize scientific data but introduces economic elements such as tourism and fossil fuel consumption. Topic 5 appears to combine multiple justificatory logics. Political reasoning seems most prominent, with references to the federal government and the 2024 elections, which may indicate that climate regulation is framed as a partisan matter influenced by broader political interests. The mention of Europe could suggest a geopolitical dimension, while economic cost–benefit considerations emerge in the comparison between fossil fuels and renewables. A social justice element also seems present, with concerns about the social effects of climate policies.

Topics 6 and 7 tend to focus on technological and economic aspects of clean energy. Topic 8 seems to be scientific-institutional, yet may also reflect the contested authority of science. Topic 9 appears to combine scientific and technological reasoning related to emissions and agriculture. Finally, Topic 10 may present a political logic with elements of social justice and elite criticism, particularly regarding sustainable food initiatives.

Overall, American discourse integrates economic–political, scientific, and technological justifications, with political elite criticism emerging as an additional element.

5. Discussion

In conclusion, we attempt to address the research questions.

The keyness analysis provides insights into the politicization of climate change in media narratives (RQ1), suggesting that it is more pronounced in the U.S. than in Italy. References to the EPA and DOE, tied to Biden’s climate regulations, may indicate a close link between climate discourse and partisan dynamics. In Italy, political references also emerge but seem to frame climate change mainly as an institutional and economic policy issue.

Regarding how the political orientation of media sources influences their language and rhetoric (RQ2), as well as the presence of populist narratives that may hinder the principles of the open society, the keyness analysis highlights distinct discursive features across political alignments. Progressive outlets appear to focus more on scientific aspects, while conservative ones seem to stress political and economic themes, often linked to the green transition. These patterns seem to align with Jasanoff’s (2003) view of ideological politicization of science.

The QCA and topic modeling suggest that, in both countries, conservative media tend to display stronger politicization, consistent with McCright and Dunlap’s (2011) evidence that Democrats are more aligned with scientific consensus than Republicans. However, U.S. progressive outlets appear more politically engaged than Italian ones, likely because climate skepticism in the U.S. appears more closely tied to partisanship, consistent with factual belief polarization (Kossowska et al. 2023; Rekker and Harteveld 2024). Progressive outlets may thus adopt explicit political framings to counter denialist attacks. Italian progressive discourse, instead, seems to rely more on scientific evidence and EU policymaking.

Further difference concerns how conservative sources seem to frame sustainable technologies. In both countries, these tend to be discussed within political-institutional contexts (the EU in Italy and presidential regulations in the U.S.). Italian outlets appear to emphasize economic implications and market aspects, while American ones, though acknowledging these dimensions, seem to privilege political interpretations that may limit alternative perspectives. Sustainable technologies may be linked to wealthy elites and may thus be presented as connected to broader political and economic interests, in line with the framing of elites against the people (Hawkins and Rovira Kaltwasser 2017).

Italian topics seem to focus more on applied and technological aspects (Topics 2, 3, 5, 6, 9, and 10), whereas American topics (2, 5, 6, and 7) tend to reflect political framings. The U.S. sample also gives greater attention to theoretical research (Topics 1, 3, 4, 8, and 9), while in Italy only Topics 4 and 7 mainly address empirical and meteorological aspects.

In both countries, activism tends to be framed through political and security perspectives, consistent with Hoffarth and Hodson (2016) on the tendency of right-wing discourse to depict environmentalists as threatening figures. In the U.S., however, it appears more marginal and acquires a class dimension, often connected to elite criticism, a feature not evident in the Italian sample. This contrast is also reflected in topic modeling: the Italian analysis includes a dedicated topic on activism (Topic 3), with minor references in Topics 2 and 7, whereas in the U.S. Topic 10 combines activism with elite criticism regarding investments in sustainable food. The latter theme, together with climate education in formal institutions (Topic 3), seems to emerge only in the American sample.

Climate history also appears differently framed. In Italy, it emerges mainly through institutional and data-driven perspectives, as in Topic 4, which refers to the EU’s Copernicus program and its systematic monitoring of climate trends. This seems consistent with the Italian tendency to frame climate issues through empirical and policy-based narratives. In the U.S., by contrast, historical climatological references often appear to normalize or minimize current climate change, presenting it as cyclical rather than primarily anthropogenic. This distinction may help explain the comparatively higher degree of politicization in the U.S., where climate change appears frequently discussed in ideological rather than scientific terms.

Further supporting this interpretation is the way climate policymaking is represented in the two contexts. In the U.S., it appears influenced by partisan dynamics and closely linked to the Democratic administration’s environmental agenda. References to Biden, the EPA, and the Department of Energy (Topics 2 and 5) suggest that climate policy is framed as a component of federal governance and electoral competition, supporting the relevance of elite cues (Guber 2013). This configuration reflects Zehr’s (2000) view that uncertainty can challenge scientific authority and Jasanoff’s (2004) notion of co-production between science and politics. Denialist arguments, such as those surrounding Mann’s lawsuit, may be seen as part of these contestations, consistent with the lack of support for climate policies due to the reduction of trust in science and institutions linked to populist narratives (Huber et al. 2020).

In contrast, the analyzed Italian media appear to frame climate policymaking largely within European and international dynamics, as suggested by the references to the EU and COP28, with limited attention to national politics. Giorgia Meloni is mentioned in Topic 2 in relation to the economic and social implications of European climate policies and clean energy, while Topic 8 focuses on the European elections and the role of Green Parties. Conversely, the American sample tends to present climate policymaking mainly as a federal matter, detached from supranational frameworks. This, together with the previously mentioned ideological rather than economic approach to sustainable technologies observed in the analyzed conservative sources, appears consistent with the tendency toward climate inaction described by Kulin (2024). In contrast, the Italian discourse seems closer to what Swyngedouw (2010) describes as a technocratic and managerial approach to climate governance, as climate change tends to be framed mainly through institutional and policy-based perspectives rather than political conflict.

Topic analysis also sheds light on the main issues emphasized in media coverage across both contexts (RQ3). Economic and political themes appear alongside scientific and technological perspectives, particularly in debates on fossil fuels, renewable energy, and climate policymaking. Activism emerges in both samples, though in the U.S. it appears more marginal and linked to elite criticism.

Topic modeling also offers insights into RQ4, concerning the most prominent human actors and factors in media discourse. In the Italian sample, the main human actors include national and European politicians, scientists, and activists, while explicit denialist voices appear marginal. Factors such as fossil fuels, renewable energy, electric vehicles, climate policies, and the market reflect the economic and technological orientation of the debate. In the American sample, the key human actors comprise political and institutional figures (such as President Biden and the DOE), scientists, activists, and wealthy individuals such as Bezos, seemingly mentioned in relation to elite criticism. The main factors include climate policies, emissions, fossil fuels, renewable sources, the economy, and clean technologies such as wind and electric energy.

Table 5 summarizes these actors and their roles within national climate narratives, highlighting how they relate to institutional trust, scientific expertise, and political conflict.

Table 5.

Main actors and their roles in climate change discourse.

Overall, the analyses suggest that Italian media discourse addresses a broader range of climate issues and appears less politicized than the American one. In both contexts, conservative sources appear to favor political framings emphasizing economic and cost–benefit aspects of sustainable technologies. This approach seems more technocratic in Italy, consistent with Swyngedouw’s (2010) notion of depoliticized governance, whereas in the U.S. it is more overtly political, reflecting stronger ties to the Democratic administration and contestation of scientific authority (Zehr 2000). These patterns seem to align with Jasanoff’s (2004) co-productionist view which emphasizes the reciprocal shaping of scientific knowledge and politics.

The contrast between populist and technocratic framings suggests that climate communication functions as a key arena where the authority of scientific expertise, policymaking, and political identities intersect and are continuously negotiated, revealing how polarization shapes both the perception of science and the politics of climate action.

This study aims to shed light on how Italian and American democratic systems may exhibit different forms of weakness. In the U.S., polarization over climate science appears to reflect a broader decline in trust toward both scientific expertise and political institutions, to the point where science itself can become a marker of partisan identity. In Italy, by contrast, climate communication seems to take place in more depoliticized terms, often adopting a technocratic and managerial framing. This may indicate a tendency to delegate the management of climate-related issues to experts, which could in turn limit public discussion.

By comparing these two cases, this study suggests that the politicization of science may depend on specific political and cultural contexts, shaped by media dynamics and possibly reinforced by populist narratives. Such dynamics may pose threats to democratic deliberation and to the effective implementation of climate policymaking, given their potential to polarize political opinions and collective behavior, with science itself becoming a contested issue. Understanding these dynamics could help inform more effective approaches to climate communication and contribute to building greater trust in scientific and policymaking institutions. It is therefore important that science and mass communication be grounded in facts rather than become arenas of political dispute.

At the same time, it can support the protection and promotion of a collective understanding of the principles of the open society, grounded in pluralism and democratic debate, and facilitate transparent, open, and more inclusive decision-making processes.

6. Conclusions

This study suggests that the Italian and American media sources analyzed address climate-related issues from different perspectives, the former adopting a more technocratic approach and the latter a more political one, reflecting their respective political and media environments. These dynamics shape public engagement with climate change and, more importantly, with scientific communication, influencing both individual and collective perceptions of the issue. Given the urgency of addressing climate change and the risk that political polarization may slow down or limit the implementation of environmental policies, it is important that journalistic practices adopt a more neutral and less polarized approach. Such an orientation could encourage broader public participation in decision-making and policymaking processes, support democratic dialogue across different social groups, and make scientific evidence more accessible to audiences without specialized expertise, in accordance with the principles of the open society.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.D.L. and M.M.; methodology, A.D.L. and M.M.; software, A.D.L.; formal analysis, A.D.L.; investigation, A.D.L.; writing—original draft preparation, A.D.L.; writing—review and editing, A.D.L. and M.M.; supervision, M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by NextGenerationEU Italy PNRR DM 351, grant number D53C22002400005.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors used ChatGPT 4.1 exclusively for linguistic revision and readability purposes. The AI tool was not used to generate any textual content, data, or interpretative material.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Benoit, Kenneth, Kohei Watanabe, Haiyan Wang, Paul Nulty, Adam Obeng, Stefan Müller, and Akitaka Matsuo. 2018. quanteda: An R package for the quantitative analysis of textual data. Journal of Open Source Software 3: 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besel, Richard D. 2011. Opening the “Black Box” of Climate Change Science: Actor-Network Theory and Rhetorical Practice in Scientific Controversies. Southern Communication Journal 76: 120–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. 2023. Statement by Chair Jerome H. Powell on Principles for Climate-Related Financial Risk Management for Large Financial Institutions. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. October 24. Available online: https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/pressreleases/powell-statement-20231024b.htm (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Chen, Alvin. 2023. Chapter 6 Keyword Analysis. Corpus Linguistics NTNU ENC 2036. March 17. Available online: https://alvinntnu.github.io/NTNU_ENC2036_LECTURES/keyword-analysis.html#keyword-analysis (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Del Gobbo, Emiliano, Sara Fontanella, Annalina Sarra, and Lara Fontanella. 2021. Emerging Topics in Brexit Debate on Twitter Around the Deadlines. Social Indicators Research 156: 669–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fobbe, Seán. 2024. Key Word in Context (KWIC) Analysis and Lexical Dispersion Plots. Seán Fobbe. November 1. Available online: https://seanfobbe.com/tutorials/kwic-lexical-dispersion/ (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Guber, Deborah L. 2013. A Cooling Climate for Change? Party Polarization and the Politics of Global Warming. American Behavioral Scientist 57: 93–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallin, Daniel C., and Paolo Mancini. 2016. Ten Years After Comparing Media Systems: What Have We Learned? Political Communication 34: 155–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, Kirk A., and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser. 2017. The Ideational Approach to Populism. Latin American Research Review 52: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffarth, Mark R., and Gordon Hodson. 2016. Green on the outside, red on the inside: Perceived environmentalist threat as a factor explaining political polarization of climate change. Journal of Environmental Psychology 45: 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, Diana L. 2024. Exploring the Extremes: The Impact of Radical Right-Wing Populism on Conspiracy Beliefs in Austria. Social Sciences 13: 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, Robert A., Lukas Fesenfeld, and Thomas Bernauer. 2020. Political populism, responsiveness, and public support for climate mitigation. Climate Policy 20: 373–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasanoff, Sheila. 2003. (No?) accounting for expertise. Science and Public Policy 30: 157–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasanoff, Sheila. 2004. States of Knowledge: The Co-Production of Science and the Social Order. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kossowska, Małgorzata, Paulina Szwed, and Gabriela Czarnek. 2023. The Role of Political Ideology and Open-Minded Thinking Style in the (in)Accuracy of Factual Beliefs. Political Behavior 45: 1837–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kukkonen, Anna, Mark C. J. Stoddart, and Tuomas Ylä-Anttila. 2020. Actors and justifications in media debates on Arctic climate change in Finland and Canada: A network approach. Acta Sociologica 64: 103–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulin, Joakim. 2024. Climate whataboutism and rightwing populism: How emissions blame-shifting translates nationalist attitudes into climate policy opposition. Environmental Politics 34: 979–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayring, Philipp. 2014. Qualitative Content Analysis: Theoretical Foundation, Basic Procedures and Software Solution. Klagenfurt: Available online: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-395173 (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- McCright, Aaron M., and Riley E. Dunlap. 2011. The politicization of climate change and polarization in the American public’s views of global warming, 2001–2010. Sociological Quarterly 52: 155–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merry, Melissa K. 2024. Climate change news coverage, partisanship, and public opinion. Climatic Change 177: 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murel, Jacob, and Eda Kavlakoglu. n.d.What Is Topic Modeling? IBM. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/think/topics/topic-modeling (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Popper, Karl. 1945. The Open Society and Its Enemies. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. 2021. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Rekker, Roderik, and Eelco Harteveld. 2024. Understanding factual belief polarization: The role of trust, political sophistication, and affective polarization. Acta Politica 59: 643–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swyngedouw, Erik. 2010. Apocalypse Forever? Post-political Populism and the Spectre of Climate Change. Theory, Culture & Society 27: 213–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Guardian. 2024. US Climate Scientist Michael Mann Wins $1m in Defamation Lawsuit. The Guardian. February 9. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2024/feb/09/us-climate-scientist-michael-mann-wins-1m-in-defamation-lawsuit (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- VERBI Software. 2021. MAXQDA. Berlin: VERBI Software. Available online: https://www.maxqda.com/products/maxqda (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Williams, Thomas D. 2024. Alarmists Praise ChatGPT as Defender of ‘Climate Emergency’. Breitbart. February 5. Available online: https://www.breitbart.com/environment/2024/02/05/alarmists-praise-chatgpt-as-defender-climate-emergency/ (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Zehr, Stephen C. 2000. Public representations of scientific uncertainty about global climate change. Public Understanding of Science 9: 85–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).