1. Introduction

Achieving universal access to quality education for all girls and boys is central to the Sustainable Development Goal 4 (SDG 4), which calls for “inclusive and equitable quality education and lifelong learning opportunities for all” by 2030. Global agreements reflect the widespread agreement on the importance of compulsory and tuition free education which is called for at the primary level in the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) and the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR). Extending years of compulsory education, as well as tuition free education, has been the focus of IGO and civil society efforts (

Sheppard 2022;

Gruijters et al. 2024;

UNESCO 2016). Yet there are still an estimated 78 million primary-school-age children, 64 million lower-secondary-school-age children, and 130 million upper-secondary-school-age children out of school globally (

UNESCO 2025).

1.1. National Policies That Can Support Greater School Attendance and Educational Attainment

Compulsory education can have a marked impact on children’s access to schools. By making education compulsory, governments assume responsibility for ensuring educational provision, which often leads to greater public investment in schools (

Grépin and Bharadwaj 2015;

Sarkar 2016;

Wang et al. 2020). Compulsory education also obligates parents to provide this opportunity to children.

Importantly, it is the combination of compulsory and tuition-free education that has the greatest potential impact both on increasing attendance and reducing inequalities. A series of studies has shown the effectiveness of compulsory schooling in increasing educational attainment as well as in reducing inequality across gender in Europe (

Brunello et al. 2009;

Elsayed 2019;

Momo et al. 2021;

Milovanska-Farrington and Farrington 2023;

Rauscher 2014) and one study showed the effectiveness of increasing years of compulsory education on educational secondary school entry across LMICs (

Diaz-Serrano 2020). Particularly relevant to the question of compulsory education in Africa is a study of seven sub-Saharan African countries showing that making lower secondary education compulsory, as well as tuition free, increased educational attainment by 1.6 grades for girls and 1.4 grades for boys, with the largest improvements amongst children from families in the lowest wealth quintile (

Martin et al. 2025).

1.2. Out-of-School Children in Africa

Although education remains a top priority for people across Africa, an increasing number of Africans are dissatisfied with their government’s effort to address educational needs (

Amakoh 2022). Half of the world’s out-of-school children live in sub-Saharan Africa (

UNESCO 2025). Within the region, girls, children living in rural areas, children from poorer families, and children with disabilities are more likely to be out of school (

UNESCO 2024;

UNICEF 2022).

While only a first step, the passage by countries of national policies to make education compulsory and tuition free is a critically important step. While compulsory education can markedly increase the number of children attending school, the degree to which different groups of children and youth benefit depends on how successfully it is implemented. To our knowledge, no research has focused on examining the extent of implementation in Africa, where implementation can present particular challenges due to limited resources, high numbers of children living in urban slums, and limited access to schools in rural areas.

Using policy data from 51 African countries and data on school attendance from 35 African countries, we assess the implementation of compulsory education laws, as well as differences in the extent of implementation across gender, household location, and household wealth.

2. Methods

To assess the implementation of compulsory education laws, we first identified countries that have made school compulsory at the primary and lower-secondary levels in Africa, one of the regions with the highest percentages of out-of-school children. Because there is widespread agreement on the importance of removing financial barriers to education by making it tuition free, and tuition charges create implementation barriers, particularly for poorer families, we limit our sample to countries that have made education tuition free as well. We then use the percentage of children reported as attending school to measure whether laws are well implemented, including disparities in implementation across gender, household location, and household wealth.

2.1. Policy Data

Country-level data on policies and legislation regarding compulsory and tuition-free education were drawn from a database constructed by the WORLD Policy Analysis Center. This study builds on past work examining where countries have passed laws making education tuition free and compulsory (

Moriyasu et al. 2025;

Raub and Heymann 2021;

Heymann et al. 2014;

Milovantseva et al. 2018). This database provides comprehensive details on education laws and policies across 51 African countries from 1990 to 2019, documenting whether education at each level of schooling from primary through the completion of secondary was designated as compulsory and tuition free, the respective years of policy adoption, and the official ages of schooling. The database construction relied on national legislation and official country documents available primarily via the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization’s (UNESCO) Observatory on the Right to Education supplemented with legislation available through individual country legislative repositories. Data coding was conducted independently by two researchers who then reconciled their answers. Countries with means-tested programs or free education only for poorer students were not considered to guarantee tuition-free education. To validate that constitutional rights, laws, and policies mandating tuition-free education were in place, country reports and other secondary sources were consulted. If these sources indicated that tuition fees continued to be charged despite a legal guarantee, the country was coded as not providing tuition-free education. Other types of fees, such as for textbooks or uniforms, were excluded from this analysis.

2.2. Outcome Data

The individual-level data used in this study come from the Demographic Health Surveys (DHS).

1 The DHS are nationally representative cross-sectional household surveys conducted in 90 low- and middle-income countries. During the sampling process in each country, households were randomly selected from a comprehensive list of all households within a designated primary sampling unit.

Our sample includes 687,276 children of official school ages across 35 African countries, drawing on DHS data available between 2010 and 2019 to capture the situation in a country in the last decade before the COVID-19 pandemic.

2 Observations with missing values on age or the characteristics used in our analysis were omitted. These accounted for less than 0.1% of the total sample.

The main outcome of interest is a binary variable of whether the household member has attended school at any time during the school year. We also utilized data on the household member’s gender along with data on household location and wealth index. The wealth index is constructed by the DHS and is a composite measure of the household’s standard of living calculated using principal component analysis on the household’s ownership of selected assets. The index is divided into quintiles from the poorest to the richest.

2.3. Analyses Conducted

We first examined whether the countries had adopted policies on compulsory and tuition-free education at the primary and lower-secondary levels at least one year before the DHS was conducted. Among countries that had passed tuition-free and compulsory education, we then calculated how many children were reported as attending school among those whose age matched with the official ages for primary and lower-secondary levels. Calculations utilized the weights for household members generated by IPUMS-DHS (

Boyle et al. 2022). To examine gender disparities in education, we calculated attendance for sub-groups of household members based on their gender. Comparison of the percentage attending school between genders was conducted using weighted

t-tests. We then used regression analysis to examine the association between overall rates of attendance and gender gaps at the primary level; too few countries made secondary school compulsory to carry this analysis for it. For both levels, we also examined differences in attendance by household location and household wealth using weighted

t-test.

3. Results

3.1. Adoption of Laws and Policies and Sample of Children

Table 1 shows the years of the DHS along with the years of adoption of the two policies for the three levels of education across the thirty-five African countries in our sample. A total of 27 of the 35 countries (77%) in our sample had made primary education tuition free and compulsory at least one year prior to the survey year. Far fewer had made lower secondary tuition free and compulsory: just 15 of the 35 countries (43%). Only a minority of countries, 2 of 35 (6%), had made upper secondary tuition free and compulsory.

The sample is consistent with policies across the African Union after accounting for improvements in laws and policies overtime. As of 2023, 92% of African Union countries had made primary education tuition free and compulsory compared to 67% for lower secondary and just 15% for upper secondary (

WORLD Policy Analysis Center 2025).

As shown in

Table 2, the sample of 687,694 children has a mean age of 11.34 years and an equal gender distribution. Of the sampled household members, 66% reside in rural areas. Nearly three-quarters of children (74.2%) are reported as having attended school.

3.2. Primary Schooling

Table 3 presents the data on whether primary-school-aged children attended school across African countries that have made education tuition free and compulsory. It reveals considerable variation in the share of children who were reported as having attended school.

Several countries have more than 90% of primary-school-aged children reported as having attended school. Among the countries with compulsory and tuition-free education policies in place, Gabon has the highest share of children in school (97.5%). It is followed by Congo (95.9%), Namibia (95.5%), Kenya (94.7%), and Rwanda (92.9%). In contrast, most countries show moderate reported attendance rates ranging between 60 and 90%. For example, Angola, Mozambique, and Nigeria have less than 3 out of every 4 primary school-aged children reported as attending school. Particularly concerning are the countries with the lowest attendance rates, including Senegal (55.6%), Mali (55.2%), Chad (49.8%), and Burkina Faso (44.6%). These figures indicate that almost half or more of primary-school-aged children are out of school.

Implementation does not appear to be driven by when countries adopted tuition-free and compulsory education policies. Shaded countries in the table have adopted policies more recently. Strong implementation is seen amongst countries that adopted laws less than 5 years prior to the survey. Likewise, countries that have had policies in place for 10 or more years (no shading in the table) are seen at all implementation levels.

3.3. Secondary Schooling

Table 4 presents the proportion of lower-secondary-school-aged children reported as having attended school across African countries that made this level of schooling free and compulsory prior to the DHS survey. As with primary education, there is a wide range in whether children are reported as having attended school at the lower-secondary level among countries.

Among countries with both compulsory and tuition-free lower-secondary education policies, Gabon has the highest reported attendance (97.8%), followed by Kenya (96.4%), Malawi (95.2%), Egypt (93.4%), and Congo (90%). An almost equal number of countries have moderate attendance ranging between 60 and 90%. Once again, there is no relationship between when countries adopted tuition-free and compulsory education policies and whether the policy is well implemented.

3.4. Disparities in Attendance

3.4.1. Primary Schooling

Gender:

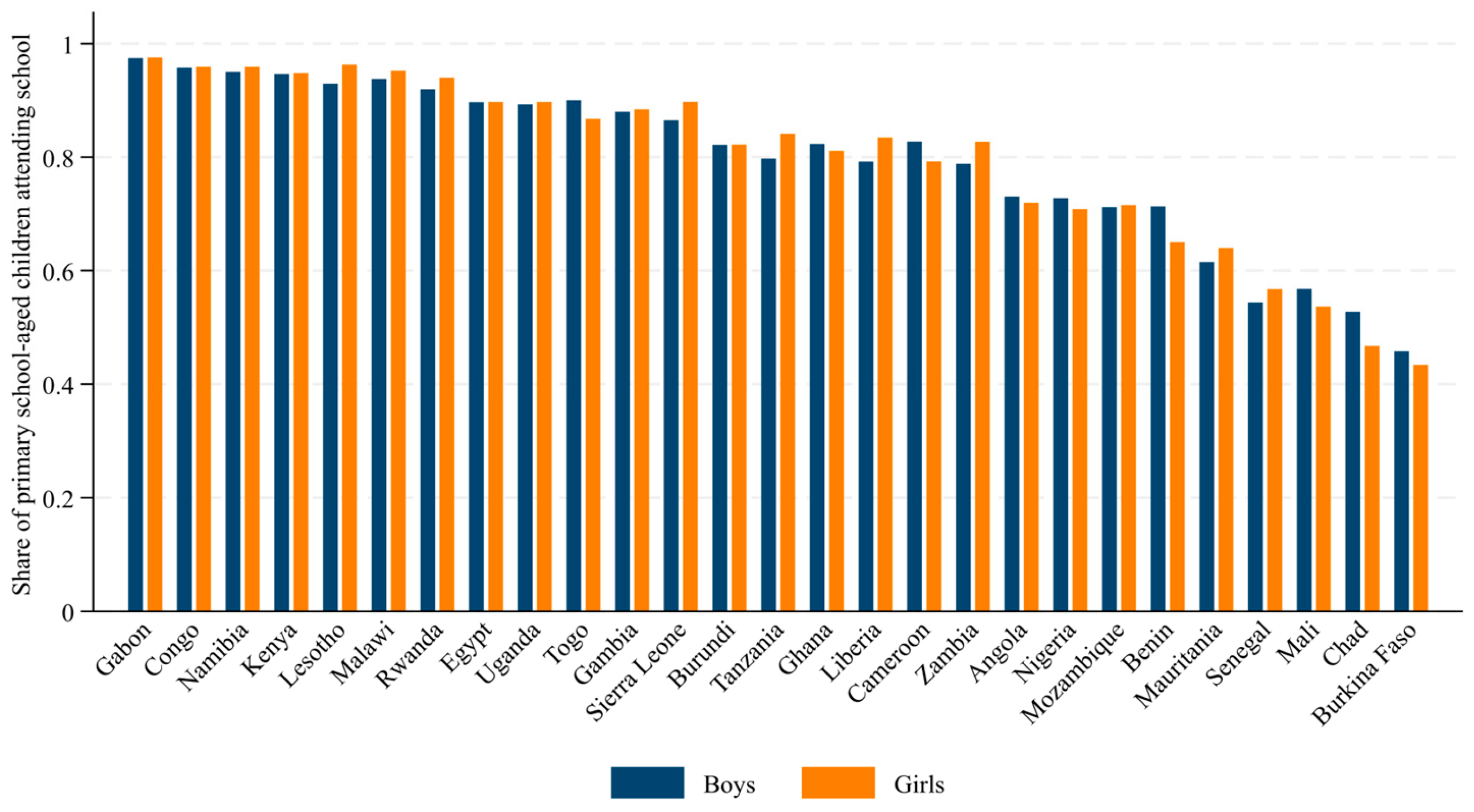

Table 5 and

Figure 1 show the gender-disaggregated attendance rates at primary school across the 27 countries with compulsory and tuition-free education policies. In 20 of the 27 countries studied, girls were as likely or slightly more likely than boys to be reported as attending school. No countries with total reported attendance of more than 90% have gender disparities that disadvantage girls. Even in countries with moderately high levels of reported attendance (70–89%), only 3 of the 14 countries have gender gaps in reported attendance that disadvantage girls. However, as the total attendance dips below 70, 4 out of the 6 countries have gender disparities that disadvantage girls, ranging from 2 to 6 percentage points lower reported attendance.

As shown in

Table 6, regression analysis shows that overall attendance is associated with a reduced gender gap. That is, a 10-percentage point increase in the percentage of primary-school-aged children reported as being in school is associated with a 0.8 percentage point decrease in the gap between male and female attendance.

Gender and household location: As shown in

Table 7, in nearly all countries, girls and boys living in urban areas were more frequently reported as having attended school than their peers living in rural areas. Differences between urban and rural attendance were smaller amongst countries where more primary-school-aged children overall were reported as having attended school than in countries with lower reported attendance. For example, in the Republic of the Congo 97% of girls living in urban areas were reported as having attended school compared to 94% of girls living in rural areas. In contrast, girls living in urban areas in Burkina Faso were more than twice as likely to be reported as having attended school compared to girls living in rural areas (76% compared to 36%).

Gender and household wealth: As shown in

Table 8 and

Table 9, in all twenty-six countries

3 studied, children from households in the richest wealth quintile were more frequently reported as having attended school compared to children from households in the poorest wealth quintiles. This difference was statistically significant in all but one country (which had a small sample size). Differences across class for girls were smaller in countries where overall reported school attendance was relatively high (1 to 16 percentage points among countries where at least 90% of primary school-aged children were reported as being in school). In contrast, among countries with less than 70% of primary-school-aged children reported as being in school, disparities between girls from the richest and poorest wealth quintile were 30 to 55 percentage points. Boys from poorer wealth quintiles faced similar levels of disadvantage as girls.

3.4.2. Secondary Schooling

Gender: As shown in

Table 10 and

Figure 2, gender disparities that disadvantage girls in secondary school are more common than in primary school. Two of the five countries with total reported attendance of over 90% have small gender disparities that disadvantage girls (1 to 3 percentage points). Three of the four countries that have overall reported attendance below 70% have a gender disparity that disadvantages girls, ranging from 4 to 13 percentage points.

Gender and household location: As shown in

Table 11, in all but one country studied with tuition-free and compulsory lower secondary and available data on children living in urban and rural areas, girls living in urban areas were more likely to be reported as having attended school than girls living in rural areas. Similarly to primary education, differences were smaller in countries with higher overall reported attendance.

Gender and household wealth: As shown in

Table 12, in 13 of the 15 countries studied with tuition-free and compulsory lower secondary, girls from households in the highest wealth quintile were more likely than girls from households in the lowest wealth quintile to be reported as having attended school. Similarly to primary-school-aged children, disparities were smaller amongst countries with higher overall levels of reported attendance, ranging from −2 to 13 percentage points for girls in countries with at least 90% of lower-secondary-school-aged children reported as having attended school. For countries with overall lower-secondary-aged attendance below 70%, disparities in attendance between the richest and poorest girls ranged from 37 to 44 percentage points.

4. Discussion

Using data on whether children had attended school from twenty-seven African countries that had made education tuition free and compulsory, this study finds that once education becomes compulsory, it is possible to achieve gender parity in education. In 20 of the 27 countries studied, primary-school-aged girls were as likely or slightly more likely than boys to be reported as attending school. Regression analysis showed an association between increased overall attendance for primary-school-aged children and reduced gender disparities in attendance. However, among countries with poor implementation of compulsory primary education laws, girls are more likely to be out of school than boys. Disparities were also observed more frequently at the lower-secondary level.

There were important differences in girls’ school attendance across household location and social class. Overwhelmingly, rural girls were more likely to be out of school than urban girls. Similarly, in all countries, girls from the poorest households were more likely to be out of school than girls from the richest households. Importantly, in countries where overall implementation was high, the gaps for girls across location and social class were small, indicating strong implementation is feasible in rural areas and in poorer neighborhoods. However, in countries with overall weaker implementation, the gaps point to implementation failures for poor and rural girls, even while education is reaching a majority of girls in urban areas or from wealthier families. Boys in rural areas or from poor households were also more likely to be out of school than those from urban areas or wealthier households, indicating an implementation failure for the majority of rural and poor children in countries with overall weaker implementation.

This study demonstrates that compulsory education laws are working in many African countries and supports existing research evidence that gender gaps can be narrowed when legal frameworks are implemented. At the same time, the disparities found underscore the need for targeted implementation in rural areas and poorer neighborhoods of urban areas. Importantly, implementation gaps were not related to when policies were adopted. The passage of time alone is not enough to ensure implementation reaches all girls and boys, but rather countries with implementation gaps need to take targeted steps to ensure children living in rural areas and from poor areas are able to access education.

This is the first quantitative study to examine the implementation of compulsory education laws across twenty-seven African countries and assess the gaps for both gender equity and disparities among girls. This study has two main limitations. First, to conduct this large-scale study, we relied on a simple measure of whether children had attended school at any time during the school year. Future research should examine disparities in more detailed measures of implementation, such as whether children are regularly attending school. Second, data were not available on why children were not attending school to better understand why implementation gaps occurred. Alongside, futures research to deepen our understanding of what the implementation barriers are in countries that have poor implementation, in-depth qualitative studies should look at the countries that are having greater success at ensuring children attend school. These studies should examine the extent to which budgetary allocations, human resources dedicated to implementation, campaigns for norm change, and other policy approaches are working to achieve education for all.

5. Conclusions

Secondary education is crucial for enabling individuals to access jobs that earn a decent income, helping to lift families out of poverty. While many African countries have made strong progress by both passing compulsory tuition-free education laws and ensuring girls and boys are in school at the primary level, greater gaps emerge at the lower secondary level. For girls, secondary education is also a strong predictor of health for the next generation (

Sperling and Winthrop 2015;

Kidman and Heymann 2018). The benefits of girls’ education also go beyond individual women and their families to increase national GDP (

World Bank 2019) and life expectancy (

Gadoth and Heymann 2020). To realize the promise of girls’ education, it is critical that countries that have already taken the important step of making education tuition free and compulsory take the next step to ensure that it is implemented for all girls and boys regardless of where they live or their family’s economic situation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.B., A.R. and J.H.; methodology, B.B., A.M., A.R. and J.H.; formal analysis, B.B. and A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, B.B., A.R. and J.H.; writing—review and editing, A.M.; visualization, B.B. and A.M.; supervision, A.R. and J.H.; project administration A.R. and J.H.; funding acquisition, A.R. and J.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation (2023-02155-GRA).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethics or IRB approval is not required for secondary research using publicly available data that cannot be re-identified per 45 U.S. CFR 46.104 d(4).

Informed Consent Statement

This study is exempt as it is a secondary analysis relying exclusively on a secondary, publicly available, and de-identified dataset, and did not involve any intervention or interaction with individuals, nor the use of identifiable private information.

Data Availability Statement

The original policy data presented in the study are openly available at worldpolicycenter.org. Restrictions apply to the availability of the outcome data. Data were obtained from IPUMS and the DHS Program and are available at idhsdata.org and dhsprogram.com with the permission of the DHS Program.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Data for most countries were obtained from the IPUM-DHS ( Boyle et al. 2022). When a survey was not available on IPUMS-DHS, it was harmonized by the staff at the WORLD Policy Analysis Center using the IPUMS codebook to ensure consistency of methods. |

| 2 | Some DHS was conducted over two to three years starting in 2019; we use only those interviews conducted in 2019. The 2019 samples in Gambon and Gambia were all from urban areas. |

| 3 | Gabon was excluded due to insufficient sample sizes within wealth quintiles, which prevented reliable estimation. |

References

- Ajayi, Kehinde, and Phillip Ross. 2020. The effects of education on financial outcomes: Evidence from Kenya. Economic Development and Cultural Change 69: 253–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amakoh, Kelechi. 2022. Declining Performance: Africans Demand More Government Attention to Educational Needs. Afrobarometer. Available online: https://coilink.org/20.500.12592/551xwt (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Banks, Lena Morgon, and Maria Zuurmond. 2015. Barriers and Enablers to Inclusion in Education for Children with Disabilities in Malawi. Oslo: Norwegian Association of Disabled. [Google Scholar]

- Boyle, Elizabeth Heger, Miriam King, and Matthew Sobek. 2022. IPUMS Demographic and Health Surveys: Version 9. Version 9. With ICF. Minneapolis: IPUMS and ICF. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunello, Giorgio, Margherita Fort, and Guglielmo Weber. 2009. Changes in compulsory schooling, education and the distribution of wages in Europe. The Economic Journal 119: 516–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chicoine, Luke. 2019. Schooling with learning: The effect of free primary education and mother tongue instruction reforms in Ethiopia. Economics of Education Review 69: 94–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Serrano, Luis. 2020. The duration of compulsory education and the transition to secondary education: Panel data evidence from low-income countries. International Journal of Educational Development 75: 102189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsayed, Mahmoud. 2019. Keeping kids in school: The long-term effects of extending compulsory education. Education Finance and Policy 14: 242–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadoth, Adva, and Jody Heymann. 2020. Gender Parity at Scale: Examining Correlations of Country-Level Female Participation in Education and Work with Measures of Men’s and Women’s Survival. EClinicalMedicine 20: 100299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grépin, Karen, and Prashant Bharadwaj. 2015. Maternal education and child mortality in Zimbabwe. Journal of Health Economics 44: 97–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruijters, Rob, Mohammed Abango, and Leslie Casely-Hayford. 2024. Secondary school fee abolition in Sub-Saharan Africa: Taking stock of the evidence. Comparative Education Review 68: 370–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heymann, Jody, Amy Raub, and Adèle Cassola. 2014. Constitutional Rights to Education and Their Relationship to National Policy and School Enrolment. International Journal of Educational Development 39: 121–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iddrisu, Abdul Malik, Michael Danquah, Alfred Barimah, and Williams Ohemeng. 2020. Gender, Age Cohort, and Household Investment in Child Schooling: New Evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa (No. 2020/9). WIDER Working Paper. Helsinki: The United Nations University World Institute for Development Economics Research (UNU-WIDER). [Google Scholar]

- İşcan, Talan, Daniel Rosenblum, and Katie Tinker. 2015. School fees and access to primary education: Assessing four decades of policy in Sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of African Economies 24: 559–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keats, Anthony. 2018. Women’s schooling, fertility, and child health outcomes: Evidence from Uganda’s free primary education program. Journal of Development Economics 135: 142–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidman, Rachel, and Jody Heymann. 2018. Prioritising Action to Accelerate Gender Equity and Health for Women and Girls: Microdata Analysis of 47 Countries. Global Public Health 13: 1634–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, Adrienne, and Isaac Mbiti. 2012. Access, sorting, and achievement: The short-run effects of free primary education in Kenya. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 4: 226–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, Alfredo, Aleta Sprague, Amy Raub, Bijetri Bose, Pragya Bhuwania, Rachel Kidman, and Jody Heymann. 2025. The Combined Effect of Free and Compulsory Lower Secondary Education on Educational Attainment in Sub-Saharan Africa. International Journal of Educational Development 113: 103218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milovanska-Farrington, Stefani, and Stephen Farrington. 2023. Compulsory education and fertility: Evidence from Poland’s education reform in 1956. International Economics and Economic Policy 20: 139–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milovantseva, Natalia, Alison Earle, and Jody Heymann. 2018. Monitoring Progress Toward Meeting the United Nations SDG on Pre-Primary Education: An Important Step Towards More Equitable and Sustainable Economies. International Organisations Research Journal 13: 122–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momo, Michelle, Sofie Cabus, and Wim Groot. 2021. Evidence on the marginal impact of a compulsory secondary education reform in Senegal on years of education and changes in high school decisions. International Journal of Educational Research Open 2: 100058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriyasu, Callahan, Adele Cassola, Aleta Sprague, Amy Raub, and Jody Heymann. 2025. Realizing the Right to Education for All: Approaches to Removing Barriers Based on Gender, Disability, and Socioeconomic Status in 193 Countries. International Journal of Educational Development 117: 103348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshoeshoe, Ramaele, Cally Ardington, and Patrizio Piraino. 2019. The effect of the Free Primary Education policy on school enrolment and relative grade attainment in Lesotho. Journal of African Economies 28: 511–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussa, Wael, and Carina Omoeva. 2020. The long-term effects of universal primary education: Evidence from Ethiopia, Malawi, and Uganda. Comparative Education Review 64: 179–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasqua, Silvia. 2005. Gender bias in parental investments in children’s education: A theoretical analysis. Review of Economics of the Household 3: 291–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raub, Amy, and Jody Heymann. 2021. Progress in National Policies Supporting the Sustainable Development Goals: Policies That Matter to Income and Its Impact on Health. Annual Review of Public Health 42: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rauscher, Emily. 2014. Hidden gains: Effects of early US compulsory schooling laws on attendance and attainment by social background. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 36: 501–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, Pauline. 1995. Female education and adjustment programs: A crosscountry statistical analysis. World Development 23: 1931–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, Chanchal Chand. 2016. Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Act, 2009 and its implementation. In India Infrastructure Report 2012. New Delhi: Routledge India, pp. 33–43. [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard, Bede. 2022. Toward Free Education for All Children. Human Rights Watch. Available online: https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/12/07/toward-free-education-all-children (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Soni, Anita, Marisol Reyes Soto, and Paul Lynch. 2022. A review of the factors affecting children with disabilities successful transition to early childhood care and primary education in Sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Early Childhood Research 20: 59–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperling, Gene, and Rebecca Winthrop. 2015. What Works in Girls’ Education: Evidence for the World’s Best Investment. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. 2016. Education 2030: Incheon Declaration and Framework for Action Towards Inclusive and Equitable Quality Education and Lifelong Learning for All. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000245656 (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- UNESCO. 2024. Global Education Monitoring Report, 2024/5, Leadership in Education: Lead for Learning. GEM Report UNESCO. Paris: UNESCO. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. 2025. SDG4 Scorecard Progress Report on National Benchmarks: Focus on the out-of School Rate. GEM Report UNESCO and Unesco Institute of Statistics. Paris: UNESCO. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF. 2022. Seen, Counted, Included: Using Data to Shed Light on the Well-Being of Children with Disabilities. Available online: https://data.unicef.org/resources/children-with-disabilities-report-2021 (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Wang, Dehua, Jie Zou, and Zhonggen Mao. 2020. Schooling and income effect of education development in China: Evidence from the National Compulsory Education Project in China’s poor areas. China Finance and Economic Review 9: 24–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. 2019. The World Bank Africa Human Capital Plan. Available online: https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/910151554987573474-0010022019/original/HCPAfricaScreeninEnglish.pdf (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- World Bank, and UNICEF. 2009. Abolishing School Fees in Africa: Lessons from Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Malawi, and Mozambique. Development Practice in Education. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/2617 (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- WORLD Policy Analysis Center. 2025. WORLD Education Laws 2023. Version 1.1. With WORLD Policy Analysis Center. Harvard Dataverse. Cambridge: Harvard. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).