Abstract

Workplace bullying is a critical concern in high-risk sectors such as construction and manufacturing, where high-pressure environments, strict deadlines, and hierarchical structures may intensify the problem. Despite its serious impact on workers’ well-being and productivity, research in these sectors, particularly in Indonesia, is limited. This study examined the prevalence of workplace bullying, contributing factors, and its effects on mental health among construction and manufacturing workers. It also explored barriers to prevention and potential strategies for mitigation. A mixed-methods design was applied, involving 1029 workers (620 manufacturing, 409 construction). Quantitative data were collected using the Negative Acts Questionnaire—Revised (NAQ-R), while qualitative insights were obtained through Focus Group Discussions (FGDs). Analyses included chi-square tests, logistic regression, and thematic analysis. Bullying was more prevalent in construction, especially among younger and less experienced workers. Risk factors included work-related stress, role ambiguity, and gender dynamics. FGDs revealed underreporting due to absent policies, weak leadership, and workplace cultures that normalized aggression. Workplace bullying remains a significant issue in both sectors in Indonesia. Strong anti-bullying policies, effective leadership, and comprehensive training are essential. Transforming organizational culture toward inclusivity and support is critical to addressing this challenge.

1. Introduction

Workplace bullying has become a growing concern in the field of occupational health and safety (OHS), especially over the last three decades (Nielsen and Einarsen 2018). It is a global issue, with prevalence varying across countries and it significantly affecting both the physical and mental well-being of workers, as well as their job performance (Samsudin et al. 2018; Javed et al. 2023). Bullying in the workplace can range from verbal insults to physical threats and aggression.

In the United Kingdom, studies estimate that about 10–20% of workers have faced workplace bullying over the past ten years. In a survey covering over 70 organizations, around 10.6% of employees reported experiencing bullying in the last six months, while another survey found that number soaring to 34.5% (Silviandari and Helmi 2018). The Workplace Bullying Institute’s data further reveals that men are responsible for 67% of bullying incidents, and they are also the primary victims (58%). Women, on the other hand, make up 33% of bullies, with 65% of female bully victims being women and 35% being men (Namie and Namie 2021).

Workplace bullying is not just a problem in developed countries; it is also widespread in developing nations such as Indonesia. For instance, a troubling case recently took place at Hasan Sadikin Hospital in Bandung, West Java, where a medical specialist student faced both verbal and physical bullying by a senior colleague during their clinical practice (Siswadi 2024). In Surabaya, a study found that nearly half (49%) of 123 workers had witnessed bullying firsthand (Gunawan et al. 2009).

Another study in Indonesia involving 3,140 workers showed that while 89.2% claimed they had never been bullied, 8.1% said they had experienced it rarely, and 2.1% admitted to facing it occasionally. In terms of perpetrators, coworkers were the most common culprits (8.5%), followed by direct supervisors (2.4%) and other organizational supervisors (2.1%), with the majority of bullies being male (6.3%). Interestingly, 74% of respondents reported good mental health, while 16% showed signs of mild mental disorders (Erwandi et al. 2021). Despite these statistics, workplace bullying in Indonesia is rarely discussed openly. Many organizations choose to keep such incidents under wraps to protect their reputation and avoid investigations. As a result, detailed data on workplace bullying in Indonesia remains scarce (Erwandi et al. 2021; Pertiwi and Satrya 2022).

Workplace bullying has serious consequences for both productivity and well-being (Alam et al. 2025; Ronha and Rodrigues 2025; Omrani 2022; Quinn et al. 2025). In industries such as construction and manufacturing sectors, high-pressure work environments, tight deadlines, and rigid hierarchies often act as triggers and facilitators for bullying. Research shows that these sectors experience higher rates of workplace bullying compared to others. This was found to be largely due to the intensive teamwork required, differences in social status, and a lack of support in the workplace culture (Feijó et al. 2019).

In Indonesia, the majority of research on workplace bullying has focused on general work environments, for example, offices and healthcare settings, with little attention given to high-risk industries such as construction and manufacturing. Yet, these sectors are the backbone of the national economy, employing millions of workers who face high levels of job stress and significant physical and mental risks. Understanding the extent and nature of bullying in these industries is essential for creating effective interventions and building healthier, more productive work environments.

Bullying and employees’ reactions to it are shaped by organisational conditions. Factors such as organizational changes, feelings of procedural injustice, and a toxic work environment are closely linked to higher rates of bullying. Similarly, leadership styles that are authoritarian, destructive, or overly controlling tend to lead to more incidents of bullying. Other contributing factors include job characteristics, including flexible work arrangements, role confusion, interpersonal conflicts, low job satisfaction, monotonous tasks, heavy workloads, and high workplace pressure (Feijó et al. 2019; Bunce et al. 2024) These factors increase work-related stress, which in turn can affect job performance and negatively impact worker’s mental health, leading to issues like depression, anxiety, sleep disorders suicidal thoughts, and absenteeism (Holm et al. 2022).

This study adopts the Job Demands–Resources (JD-R) model to explain how organizational conditions contribute to workplace bullying. The JD–R framework posits that high job demands, such as excessive workload, unclear roles, and production pressure, can trigger strain responses that escalate into negative interpersonal behavior (Bakker and Demerouti 2007). At the same time, the absence of adequate job resources, including supportive leadership, clear procedures, and psychologically safe reporting systems, may intensify vulnerability among workers and reinforce the normalization of aggression. In high-risk sectors such as construction and manufacturing, these mechanisms operate more strongly because demands are structurally embedded in the organization of work and further amplified by competitive and hierarchical workplace cultures.

This study seeks to understand how common bullying is in the construction and manufacturing sectors and to identify the organizational and personal factors that contribute to such behavior. By taking a comprehensive approach, the research aims to make a valuable contribution to improving occupational health and safety policies in Indonesia. This study addresses the following research questions: (1) To what extent is workplace bullying prevalent in the construction and manufacturing sectors in Indonesia? (2) What individual, psychosocial, and organizational factors are associated with the likelihood of experiencing workplace bullying? and (3) How do workers in high-risk sectors perceive, respond to, and experience barriers to the prevention and control of bullying in the workplace?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

Focusing on construction and manufacturing industries, this study used a semi-quantitative, cross-sectional design that combines both qualitative and quantitative methods. For the qualitative element, Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) were held to explore workers’ experiences and perspectives on workplace bullying, including the challenges of prevention, possible solutions, policy suggestions, and the legal or regulatory impacts. For the quantitative element, surveys were distributed to measure how widespread bullying is in the workplace.

To ensure data confidentiality, the surveys were conducted anonymously, reducing the chance of employer interference. Before any data was collected, participants received clear, written information explaining the study’s goals and procedures, and they were asked to provide written informed consent. Focus group notes were anonymized and all data stored securely.

This study received approval from the Research Ethics Committee at the Faculty of Public Health, Universitas Indonesia (Approval Number: 602/UN2.F10.D11/PPM.00.02/2024).

2.2. Quantitative Research

The quantitative element was implemented through the distribution of questionnaires to measure the prevalence of workplace bullying. The study population consisted of 1296 workers recruited from two manufacturing companies and four construction companies. These companies were selected using purposive sampling based on their classification as high-risk sectors, company size (≥200 employees), and management willingness to provide access for data collection.

The inclusion criteria for the study were workers who had been employed for at least one year and were willing to participate.

The dependent variable in this study was the presence of workplace bullying, measured using the Indonesian version of Negative Acts Questionnaire—Revised (NAQ-R), with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.897 (Erwandi et al. 2021). In line with the original conceptualization of the construct, workplace bullying consists of three dimensions: work-related bullying, person-related bullying, intimidation towards a person. In this study, these three dimensions were analysed as subscales to describe underlying patterns of negative acts, while the main dependent variable was treated as a binary variable (bullied vs. not bullied). The NAQ-R consists of 22 items scored on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Never, 5 = Daily). Higher scores indicate more frequent exposure to negative acts.

In addition, independent variables included demographic characteristics, psychosocial aspects, measured using the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire III (COPSOQ III) (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.844), and psychological distress, assessed using the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10) (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.881) as prolonged exposure to bullying is known to escalate emotional exhaustion and distress, functioning as both a consequence and a reinforcing vulnerability factor. In addition, medical history and health conditions were included in this study based on the psychosomatic vulnerability model, which posits that workers with pre-existing illness may have reduced coping capacity, higher fatigue accumulation, and greater psychological strain, making them more vulnerable to mistreatment or exclusion in the workplace (Bahall and Bailey 2022; Attell et al. 2017; Xiao et al. 2022). Data collection for the questionnaire was conducted between July and November 2024.

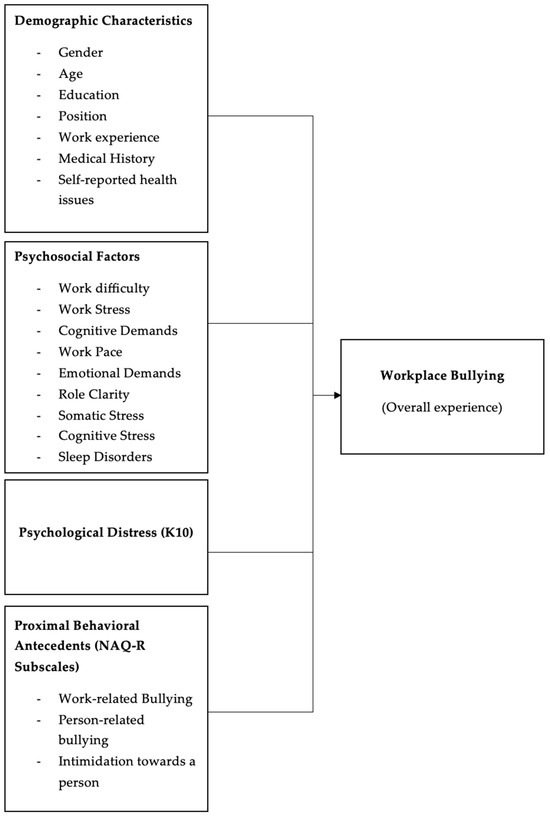

In this model (Figure 1), demographic characteristics, psychosocial work conditions, and psychological distress are conceptualized as distal antecedents of workplace bullying. The three NAQ-R subscales, namely work-related, person-related, and intimidation-based bullying, represent proximal behavioral predictors that capture specific negative acts contributing to the overall bullying experience. The dependent variable reflects the binary classification of bullying exposure (bullied vs. not bullied), consistent with the NAQ-R scoring framework.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model showing the antecedents of workplace bullying.

Univariate analysis was conducted using frequency percentages to describe the distribution of data by grouping them based on sector and bullying. Bivariate analysis using chi-square tests examined the association between bullying and various characteristics, including demographic factors, work related aspects (difficulty and stress), psychosocial factors, and bullying factors (Person-Related Bullying, Work-Related Bullying and Intimidation Towards a Person) (Erwandi et al. 2021). The multivariate analysis conducted by the researcher was multiple logistic regression with the backward logistic regression (LR) method used to identify the factors that most influence bullying in the workplace. Odds ratios (ORs) were also calculated, where values below 1 indicated protective factors, while values above 1 represented risk factors. All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics Grad Pack 29.0 PREMIUM.

2.3. Qualitative Research

The qualitative element was conducted utilizing focus group discussions (FGDs) in two industrial sectors, manufacturing and construction. Participants were selected using a purposive sampling technique, assisted by human resources and occupational health and safety (OHS) officers in each company. This approach ensured the inclusion of individuals from different organizational levels, including top management, middle management, and operational workers, representing a wide range of job functions and experiences. The selection criteria emphasized participants with at least one year of work experience and familiarity with organizational dynamics related to workplace interactions.

A total of six FGDs were conducted in the construction sector, with each group consisting of 6–8 participants. The sessions involved ten operational workers from various divisions, such as mechanics, administration, surveyors, drafters, engineers, general affairs, logistics, accounting, quality control, and civil engineering. Additionally, eight respondents from middle management, consisting of supervisors, and seven respondents from top management, including project managers, construction managers, site managers, engineering managers, quality control managers, procurement managers, and planning managers, participated in the discussions.

In the manufacturing sector, three FGDs were conducted, also comprising 6–8 participants per group. These included eight operational workers from different divisions, such as food ingredients, food products, planning, production support, general & administration, food laminating, quality assurance, and food product. Furthermore, seven respondents from middle management, including supervisors from divisions such as food ingredients, food products, production planning, production support, general administration, food laminating, and quality assurance, also participated. The FGDs focused on workers’ experiences and perceptions of workplace bullying, challenges in prevention and control, mitigation strategies, policy recommendations, and the legal and regulatory implications of workplace bullying.

The FGDs were conducted face-to-face between 17 July and 30 November 2024, with each session lasting between 90 and 120 min. All discussions were audio-recorded with participant consent, and the data were analyzed using thematic analysis with the assistance of NVivo software.

The data was thematically analyzed and in stages, starting with familiarization through repeated reading of FGDs transcriptions. The next step was the open coding process, which involved labeling relevant data to the research focus. Similar codes were then grouped into initial categories. These initial categories were further analyzed to identify interconnections between concepts, which were then developed into key themes. These themes encompassed experiences and perceptions of workplace bullying, challenges in prevention and control, mitigation strategies, policy recommendations, and legal and regulatory implications. To maintain the credibility of the analysis, the researchers employed a data triangulation strategy by comparing findings from various data sources across participants and FGD groups.

3. Results

Table 1 shows that this study reveals distinct patterns of bullying across demographic and occupational factors, with significant disparities between the manufacturing and construction sectors. The construction sector consistently exhibited higher bullying prevalence across nearly all demographic and occupational groups compared to manufacturing. 1029 respondents took part in this study, which consists of 620 manufacturing workers and 409 construction workers. Among the key factors influencing bullying risk, gender and work experience stand out. In the manufacturing sector, female workers experienced higher bullying rates than males (9.4% vs. 5.6%), whereas in the construction sector, the trend was reversed, with males being more affected (22.6% vs. 14.3%). In a similar situation, early career workers (1–5 years of work period) were more vulnerable to bullying, particularly in the construction sector, where the prevalence reached 24.3%.

Table 1.

Demographic factors, psychosocial factors, and bullying factors based on sectors and bullying.

Age also plays a key role in the prevalence of bullying. Across both sectors, younger workers (aged < 25 years) exhibited a higher likelihood of experiencing bullying. In the manufacturing sector, the prevalence was 13.6% for this age group, while in the construction sector, it was 24.5%. As workers aged, bullying prevalence in the manufacturing sector showed a declining trend, reaching its lowest among those aged 35–40 years (4.8%) and those older than 40 years (5.1%). In contrast, in the construction sector, bullying prevalence remained relatively high across all age groups, with only a slight decrease among employees older than 40 years (17.8%). This suggests that while experience and tenure may offer some protection in manufacturing, bullying in construction persists regardless of age.

Educational background also appears to be linked to bullying exposure, though its effects differ between sectors. In the manufacturing sector, undergraduate degree holders experienced the highest bullying prevalence (11.1%), while workers with vocational school, secondary school, or graduate-level education reported no bullying cases. On the other hand, bullying prevalence in the construction sector was highest among secondary school graduates (25.3%) and elementary school graduates (22.6%). Even workers with an undergraduate degree in construction faced notable exposure to bullying (20.0%), and interestingly, the only graduate-level employee in this sector reported experiencing bullying 100% of the time.

The disparities between sectors become even more pronounced when examining bullying prevalence by job position. In the manufacturing sector, assistant managers (13.3%) and managers (25.0%) reported the highest bullying prevalence, suggesting that individuals in higher-ranking positions may also be at risk of workplace harassment. Meanwhile, frontline workers and administrative staff experienced bullying at a rate of 6.3%, with slightly lower prevalence observed among staff (4.3%) and supervisors (8.1%). In the construction sector, however, frontline workers (22.9%) and staff (21.7%) were among the most affected groups. In construction, assistant managers reported the highest rate of bullying (50.0%), while supervisors (18.8%) and managers (0.0%) experienced it at much lower rates.

Beyond demographic and occupational factors, psychological stress appears to have a strong association with bullying prevalence. Workers dealing with high work-related stress reported a notable increase in bullying, with 6.8% of those in manufacturing and a much higher 23.0% in construction experiencing it.

Table 2 presents the results of bivariate analyses using the Chi-square test to examine associations between independent variables and workplace bullying. The results show a strong connection between several factors and the risk of bullying. Construction workers were at a higher risk compared to those in the manufacturing sector. Younger workers, especially those under 25, were more likely to experience bullying than their older colleagues. In addition, factors like education level, job position, and work experience were strongly associated with the occurrence of bullying. Psychosocial elements including work pace, emotional demands, role clarity, and sleep disorders were also closely tied to an increased risk of bullying. Notably, three factors had particularly high odds ratios (OR), including Person-Related Bullying, Work-Related Bullying, and Intimidation Towards a Person. Among these, Person-Related Bullying had the greatest impact, with an odds ratio (OR) of 8.668.

Table 2.

Characteristics and Risk Factors Associated with Bullying.

This study’s findings indicate that multiple factors significantly influence the likelihood of bullying as shown in Table 3. Work-related bullying emerged as the most influential factor, with an OR of 11.550, highlighting that employees experiencing work-related bullying are over 11 times more likely to be subjected to further bullying. Thus, also implied to intimidation towards a person was also a strong predictor, increasing the risk of bullying by approximately 4.357 times. Among the NAQ-R subcategories, work-related bullying was the most prevalent, followed by intimidation-based bullying, while person-related bullying appeared less dominant in comparison. On the other hand, certain factors demonstrated a protective effect against bullying. Greater work experience was significantly associated with a reduced risk, with an OR of 0.450. Additionally, higher emotional demands in the workplace were linked to a lower likelihood of experiencing bullying (OR = 0.122).

Table 3.

Results of multiple logistic regression analysis using the backward elimination method to identify factors associated with workplace bullying.

Five main categories of workplace bullying dynamics were identified based on qualitative data analysis. These categories include: (1) experiences and perceptions of workplace bullying, (2) challenges in prevention and control, (3) mitigation strategies, (4) policy recommendations, and (5) legal and regulatory implications, as shown in Table 4. Each category provides a more in-depth overview of the factors influencing the persistence and handling of bullying in the workplace.

Table 4.

Five main categories of workplace bullying dynamics.

- Category 1: Experiences and Perceptions of Workplace Bullying

- Verbal Bullying Incidents in the Workplace

The data analysis showed that the majority of workplace bullying identified was verbal. This pattern was consistent across both sectors, with male workers’ bullying being more prevalent, particularly at the staff level. Respondents revealed that they were most commonly subjected to verbal bullying, such as rude comments and verbal intimidation.

Bullying occurs quite frequently, particularly in the form of comments or remarks that may be demeaning. (R1, Staff, Manufacturing)

Furthermore, management also revealed that they received reports of incidents primarily dealing with verbal harassment.

We receive several reports each year, mainly related to verbal harassment….. (R1, Manager, Manufacturing)

This finding contrasts with the quantitative analysis, which showed that women experienced more frequent bullying in the workplace.

- Psychological Distress as a Consequence of Bullying

Psychological distress emerged as one of the most prominent consequences of workplace bullying. The forms of psychological distress experienced by respondents varied, ranging from feelings of depression and emotional exhaustion, anxiety, and hesitation to express opinions. Several victims described feelings of disrespect and insecurity in the work environment, which ultimately reduced self-confidence and willingness to take initiative.

It negatively affects mental well-being, as I often see reports about employees feeling stressed and emotionally exhausted due to workplace bullying. (R2, Supervisor, Construction)

This impact affects the individual’s psychological well-being and professional performance, such as decreasing work quality, reducing productivity, and leading some victims to resign from their jobs.

Bullying lowers victims’ confidence in completing tasks, causing them to perform only at the minimum required level. (R3, Manager, Construction)

Professionally, victims often lose motivation, experience a decline in productivity, and, in some cases, choose to resign from their jobs. (R4, Manager, Manufacturing)

- Perceiving Bullying Behaviors as Jokes or Banter

Data analysis shows that bullying is often perceived as a joke or a standard form of social interaction in the workplace in both sectors, manufacturing and construction. Most respondents considered such behavior merely part of “joking around” or entertainment, blurring the line between joking and harmful behavior.

Similarly, bullying is generally perceived as joking around, simply entertainment. (R5, Staff, Construction)

This perception makes bullying seem normal and even accepted as part of everyday work dynamics.

Bullying is often perceived as ambiguous and mistaken for ordinary workplace banter. (R8, Staff, Manufacturing)

- Category 2: Challenges in Prevention and Control

- Absence of Specific Anti-Bullying Policies

The lack of a clear anti-bullying policy is a significant obstacle to preventing and addressing bullying. This makes it difficult for workers to report cases without fear of repercussions and clarity on the protections available to them.

The absence of clear anti-bullying policies makes it difficult for employees to report cases without fear of consequences. (R1, Supervisor, Construction)

Most existing policies focus solely on physical aspects of Occupational Safety and Health (OSH), without addressing protections against bullying behavior. This indicates that protecting workers’ psychological safety has not received the same level of attention as physical safety.

- Poor Leadership Role Modeling

The findings suggest that authoritarian leadership styles and rigid hierarchical structures contribute to the difficulty of controlling workplace bullying.

Authoritarian leadership styles and rigid hierarchical structures can make bullying difficult to control. Some supervisors view excessive pressure as part of the workplace culture rather than as bullying. (R6, Supervisor, Construction)

A lack of leadership role models contributes to the normalization of bullying within teams, while a lack of direct oversight means incidents often go unnoticed by senior management.

A lack of leadership role models, leading some bullying behaviors to be normalized within teams. (R6, Manager, Manufacturing)

Furthermore, management’s tendency to view bullying as a personal matter between employees hinders a firm’s institutional response.

- Lack of Structured Awareness and Training Programs

The lack of systematic anti-bullying training and awareness programs creates a significant gap in understanding among both employees and managers. They often struggle to distinguish between bullying behavior and everyday interactions. The lack of formal training also contributes to weak policy implementation. While some companies have general rules regarding workplace behavior, their implementation is often ineffective due to a lack of education for both managers and employees.

Even when anti-bullying policies exist, their implementation is often ineffective due to insufficient training for managers and employees. Without proper education, many individuals fail to recognize that their actions may constitute bullying. (R8, Manager, Manufacturing)

As a result, prevention efforts are limited, and bullying cases continue to recur without effective intervention mechanisms.

- Distrust and Fear in Reporting Mechanisms

Despite management efforts to address workplace bullying, the lack of transparency in handling cases has led many employees to doubt the system’s effectiveness. While anti-bullying policies may be outlined in the employee code of conduct, including reporting and investigation procedures, implementation remains challenging. Many employees are reluctant to report incidents due to perceived unfairness or concerns about the impact on their careers.

The company has an anti-bullying policy outlined in the employee code of ethics, including reporting and investigation procedures. However, its effectiveness needs improvement, as many employees hesitate to report incidents due to concerns about potential career repercussions. (R1, Manager, Manufacturing)

As a result, existing policies are not functioning as intended, and bullying cases persist without an effective response.

- Cultural Normalization of Bullying Practices

Findings show that workplace bullying is often normalized through highly competitive and results-oriented organizational cultures. In this context, excessive pressure, harsh reprimands, and even aggressive behavior are not viewed as bullying but as part of everyday work practices.

In highly competitive work environments, excessive pressure is often normalized, even though it may constitute workplace bullying. Changing such deeply ingrained work cultures presents a significant challenge. (R3, Manager, Manufacturing)

A competitive work culture frequently encourages aggressive behavior, which some individuals perceive as normal. (R3, Staff, Manufacturing)

This normalization presents a significant challenge to prevention efforts, as bullying practices become ingrained in organizational culture and are difficult to separate from accepted work standards.

- Category 3: Mitigation Strategies

- Adaptation of Proven Best Practices

Some respondents emphasized the importance of companies adopting proven practices to address and handle workplace bullying effectively. This can be achieved through communication media such as posters, videos, and company apps to raise employee awareness. Furthermore, early intervention programs such as mentoring and support groups help employees share experiences and prevent escalation.

Establishing early intervention programs, such as mentoring systems or support groups where employees can share their experiences. This proactive approach helps prevent bullying from escalating into more severe issues. (R7, Manager, Manufacturing)

Enforcing firm and fair sanctions against perpetrators of bullying, regardless of position, also plays a crucial role in building a healthy, bullying-free workplace culture.

- Proactive Managerial Involvement in Prevention

Proactive managerial involvement is a key element in preventing workplace bullying. This can be achieved through increased supervision and employee interaction to detect potential cases early. Management also needs to enforce strict sanctions against perpetrators as a commitment to zero tolerance. Furthermore, a positive and inclusive work culture must be instilled from the outset, with leaders acting as role models and demonstrating fair and transparent leadership.

Instilling a positive and inclusive work culture from the outset, ensuring that all employees feel valued and have equal opportunities to contribute. Managers should act as role models by demonstrating fair and transparent leadership. (R2, Manager, Manufacturing)

An active role for management in supporting HR and ensuring coordination with the Occupational Health and Safety (OHS) team will strengthen the effectiveness of anti-bullying policies and create a healthier work environment.

Increase management oversight and interaction with employees to detect potential bullying early….Enforce strict penalties against perpetrators to deter bullying and reinforce zero tolerance….Foster an inclusive work culture that values every individual to create a positive environment. (R4, Supervisor, Construction)

- Category 4: Policy Recommendations

- Comprehensive Anti-Bullying Policy Frameworks

Participants emphasized the importance of clear and mutually understood policies. Policies must be clearly formulated, communicated to all employees, and easily understood by all parties.

Establish clear anti-bullying policies and ensure all employees understand them. (R1, Supervisor, Construction)

However, simply written policies will not be effective without a consistent socialization process. Therefore, companies need to conduct regular reviews to adapt policies to organizational dynamics and ensure their effective implementation.

Not only should policies be socialized, but they should also be reviewed regularly. (R2, Staff, Construction)

- Integration with Occupational Health and Safety (OHS) Policies

Several participants highlighted that a specific anti-bullying policy is not yet available but is still included within the OSH framework.

There is no specific policy in place, it may be integrated into the existing OSH policy. (R, Staff, Manufacturing)

Integrating the Health, Safety, and Environmental Management System (HSEMS) with workplace bullying prevention. (R, Supervisor, Manufacturing)

Integrating an anti-bullying policy into the OSH framework could be a strategic step, especially for companies that lack specific regulations. This approach positions bullying as a psychosocial risk that impacts occupational health and safety, thus gaining formal legitimacy in the company’s management system.

- Category 5: Legal and Regulatory Implications

- Limited Awareness of Existing Regulations

Most FGD employees were not entirely familiar with policies related to workplace bullying. Most employees were not entirely familiar with their company’s internal policies regarding bullying, as existing regulations generally focused only on Occupational Health and Safety (OHS) aspects. Furthermore, knowledge of national policies addressing workplace bullying was also minimal.

We are not entirely familiar with workplace bullying policies—our existing policies only cover OSH. (R4, Staff, Manufacturing)

This resulted in policies being less than optimal in protecting workers from bullying.

- Weak Enforcement of Regulatory Provisions

Several respondents stated that weak enforcement of workplace bullying regulations is a factor that allows this practice to continue.

Weak policies on handling workplace bullying—when companies lack clear procedures and strict sanctions, perpetrators feel they can act without consequences. (R1, Manager, Manufacturing)

The lack of tangible consequences for perpetrators makes them feel safe to repeat similar behavior. Furthermore, lack of company policies—handling procedures and disciplinary sanctions—creates space for perpetrators to act without fear of punishment. This situation is exacerbated by the absence of effective and safe reporting mechanisms, leaving victims often feeling unprotected and reluctant to report their experiences.

4. Discussion

This study showed that the prevalence of workplace bullying among construction workers is higher compared to the manufacturing sector. According to quantitative data, construction workers faced substantial risks, especially among young workers (<25 years) and new employees with work experience of 1–5 years. This finding aligns with a previous study showing that high-risk sectors with high workloads, tight deadlines, and rigid hierarchical structure are more vulnerable to bullying (Wright 2020; Matriano 2024; Man et al. 2022; Farr-Wharton et al. 2023). However, a different pattern is observed in relation to gender, where women in the manufacturing sector appear to be more vulnerable. Whereas in construction, male is more often affected. This might be that male workers in construction tend to be more competitive and masculine, and in manufacturing, the vulnerability of females is more evident in repetitive and interaction-intensive tasks.

Multivariate analysis revealed that work-related bullying becomes the dominant factor (OR = 11.55), following intimidation (IR = 4.35). This implies that high workload, low role clarity, and production pressure are the key contributing factors. The qualitative data of this study strengthened this finding, where respondents describe bullying as occurring intensively in terms of offensive comments, harsh reprimands, or excessive supervisory pressure. Many employees perceive such behavior as more ‘joking’ or as an element of workplace culture, which obscures its distinction from routine interactions. This process of normalization intensifies the problem, as bullying becomes regarded as acceptable and consequently remains unreported and unaddressed (Daley et al. 2025).

The impacts of workplace bullying on psychosocial factors are apparent, whereas psychosocial work factors in this study were conceptualized as antecedents rather than outcomes. Our study found a significant correlation between workplace bullying and sleep disorders, as well as psychosocial distress. Additionally, qualitative data revealed that some victims reported a loss of self-confidence, which led them to limit their performance to just meeting the minimum expectations. This is in line with the literature in that bullying has a strong association with depression, anxiety, and decreased productivity (Farr-Wharton et al. 2023; Ajibewa et al. 2025; Man et al. 2022; Moon and Mello 2021). Although not emerging as the strongest predictor in the regression model, the presence of chronic illness may still heighten vulnerability to bullying through psychosomatic strain mechanisms, as workers with ongoing medical conditions may have reduced coping reserves and be more prone to stigmatization in high-pressure work settings (Attell et al. 2017; Xiao et al. 2022; Bahall and Bailey 2022). Interestingly, high emotional demands appeared to function as a protective factor, likely due to workers’ greater familiarity with stress regulation and interpersonal interactions.

The main challenge in preventing workplace bullying is also identified. The absence of targeted anti-bullying policies, coupled with poor leadership modelling and scarce training, exacerbates the difficulty of addressing these cases. Some respondents expressed hesitation to report such incidents due to concerns about potential career repercussions. This reveals a gap between the written policies and how effectively they are actually enforced. Additionally, the highly competitive organizational culture often normalizes aggressive behavior as a way to meet targets, which ultimately damages the overall workplace environment. (Johnson et al. 2018; Hughes-Morgan et al. 2018; Quinn et al. 2025; Huesmann 2018)

Practically, these findings demonstrate that preventive interventions must target two levels, namely structural and cultural (Lee et al. 2013; Chowdhury 2025; Hawley and Williford 2015; Menestrel 2020; Okamoto et al. 2014). At the structural level, companies need to create a clear anti-bullying policy, integrate it into their occupational health and safety framework, and ensure there are secure reporting mechanisms in place. On the cultural level, it’s crucial to shift the organizational culture to one that values recognition, open communication, and supportive leadership. The qualitative findings, which show how bullying can be normalized as a ‘joke,’ highlight the need for ongoing awareness initiatives to address this issue. It has been evident that the central aspects of best practices for protecting and promoting worker safety, health, and well-being including leadership commitment; participation; policies, programs, and practices that support conducive working conditions; comprehensive and collaborative strategies; adherence to federal and state regulations and ethical standards; and data-driven change (Safe Work Australia 2016; Sorensen et al. 2018).

Additionally, it is important to note that the prevalence of bullying is linked to job position. In manufacturing, assistant managers and managers reported higher levels of bullying, whereas in construction, operators and staff were the most affected. Such patterns suggest that bullying is not limited to top-down dynamics but may also occur horizontally among colleagues or even in bottom-up forms. This highlights the need for an organization-wide approach, rather than focusing solely on the dynamics between superiors and subordinates. (Sun et al. 2025; Singh et al. 2021; Attell et al. 2017; Steele et al. 2020; Awashreh and Al Toobi 2025).

Therefore, this study contributes further evidence that bullying constitutes a serious psychosocial risk within high-risk industries in Indonesia. By combining both quantitative and qualitative methods, this study provides a more comprehensive understanding, linking statistical data with the real-life experiences of workers. Also, these findings suggest that bullying prevention in high-risk sectors should prioritize structural interventions targeting work design, role clarity, and supervisory practices, as work-related bullying was the most prevalent form. Strengthening reporting mechanisms and leadership accountability is particularly important to address intimidation-based acts that may be normalized as ‘discipline’. Early-career workers should also receive targeted protection and mentoring, as they appear to be the most vulnerable group. While there are some limitations, particularly the use of purposive sampling, which affects how widely the findings can be applied, the results offer a solid foundation for improving policies and prevention strategies related to workplace bullying in the construction and manufacturing sectors. Future research, especially studies with longitudinal design or organizational interventions, would help further strengthen the evidence and lead to more effective strategies for creating safer and healthier workplaces.

5. Conclusions

This study shows that workplace bullying is more common in the construction sector compared to manufacturing, with younger workers and those with 1–5 years of experience being particularly vulnerable. These findings align with previous studies showing that high-risk sectors characterized by heavy workloads and tight deadlines are more prone to bullying (Einarsen et al. 2020; Nielsen et al. 2022).

Key factors such as workload, role ambiguity, and production pressure were identified as major contributors to workplace bullying, supporting the risk–strain theoretical perspective that prolonged job stress increases exposure to negative acts (Einarsen et al. 2020). The multivariate analysis revealed that work-related bullying had the greatest impact, followed by intimidation, while workers with longer job tenure seemed to have some protection against bullying.

The primary challenges in preventing workplace bullying include the lack of clear anti-bullying policies, ineffective leadership models, and the absence of structured training and awareness programs. Similar findings have been reported in that organizational climate and managerial support play critical roles in shaping bullying (Salin 2003; Spagnoli et al. 2017). In many workplaces, a competitive culture normalizes bullying as just part of the job, which makes it harder to address. To tackle this, companies need to implement clear anti-bullying policies within their occupational health and safety (OHS) frameworks and create a more inclusive and supportive organizational culture, consistent with other studies that bullying prevention must operate at both structural and cultural levels, requiring active managerial engagement in policy enforcement and employee support (Sainz and Martín-Moya 2022; Rossen and Cowan 2012).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.K. and S.K.D.; methodology, A.K. and H.A.; software, B.A.S. and P.Y.; validation, A.K., S.K.D. and H.A.; formal analysis, A.K., F.F., B.A.S. and P.Y.; investigation, A.K., S.F. and S.S.R.; resources, A.K., S.F. and S.S.R.; data curation, A.K., F.F., B.A.S. and P.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, A.K., S.K.D., H.A., B.A.S., P.Y., F.F., S.F. and S.S.R.; writing—review and editing, A.K., S.K.D., H.A., B.A.S., P.Y., F.F., S.F. and S.S.R.; visualization, B.A.S. and F.F.; supervision, A.K.; project administration, S.F. and S.S.R.; funding acquisition, A.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Directorate of Research Funding and Ecosystem (DPER) Universitas Indonesia under Publikasi Terindeks Internasional (PUTI) Grant, grant number NKB-668/UN2.RST/HKP.05.00/2024.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Research Ethics Committee at the Faculty of Public Health, Universitas Indonesia (Approval Number: 602/UN2.F10.D11/PPM.00.02/2024 Approval Date 24 October 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the respondents while collecting data.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request, subject to restrictions related to privacy, confidentiality, and ethical considerations.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the support of the Occupational Health and Safety Department, Faculty of Public Health, Universitas Indonesia, and all participating companies. Special thanks are also extended to the enumerators who support this study. During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the authors used ChatGPT 5 for the purposes of rechecking the grammar and translation. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| OHS | Occupational Health and Safety |

| FGD | Focus Group Discussion |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| NAQ-R | Negative Act Questionnaire—Revised |

References

- Ajibewa, Tiwaloluwa A., Kiarri N. Kershaw, Mercedes R. Carnethon, Nia J. Heard-Garris, Lauren B. Beach, and Norrina B. Allen. 2025. Peer Bullying Victimization, Psychological Distress, and the Protective Role of School Connectedness among Adolescents. BMC Public Health 25: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, Mohammad Nurul, Imdadullah Hidayat-ur-Rehman, Rosy Dhall, Md. Abu Issa Gazi, Jamshid Ali, and Fariza Hashim. 2025. Is Workplace Bullying Responsible for Low Job Performance? A Twofold SEM-ANN Approach. Journal of Management World 2025: 139–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attell, Brandon K., Kiersten Kummerow Brown, and Linda A. Treiber. 2017. Workplace Bullying, Perceived Job Stressors, and Psychological Distress: Gender and Race Differences in the Stress Process. Social Science Research 65: 210–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awashreh, Raed, and Salim Al Toobi. 2025. Workplace Bullying and Its Effects on Job Performance: Evidence from the Health Sector. Journal of Applied Social Science 19: 19367244251324916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahall, Mandreker, and Henry Bailey. 2022. The Impact of Chronic Disease and Accompanying Bio-Psycho-Social Factors on Health-Related Quality of Life. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care 11: 4694–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, Arnold B., and Evangelia Demerouti. 2007. The Job Demands-Resources Model: State of the Art. Journal of Managerial Psychology 22: 309–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunce, Annie, Ladan Hashemi, Charlotte Clark, Stephen Stansfeld, Carrie Anne Myers, and Sally McManus. 2024. Prevalence and Nature of Workplace Bullying and Harassment and Associations with Mental Health Conditions in England: A Cross-Sectional Probability Sample Survey. BMC Public Health 24: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, Sunanda. 2025. Comprehensive approaches to bullying prevention: The role of evidence based programs, individualised interventions and school psychologists. TIJER—International Research Journal 12: 580–602. [Google Scholar]

- Daley, Sharon F., Muhammad Waseem, and Amanda B. Nickerson. 2025. Identifying and Addressing Bullying. Treasure Island: StatPearls Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Einarsen, Ståle Valvatne, Helge Hoel, Dieter Zapf, and Cary L. Cooper. 2020. Bullying and Harassment in the Workplace. Theory, Research and Practice. Boca Raton: CRC Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erwandi, Dadan, Abdul Kadir, and Fatma Lestari. 2021. Identification of Workplace Bullying: Reliability and Validity of Indonesian Version of the Negative Acts Questionnaire-Revised (NAQ-R). International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18: 3985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farr-Wharton, Ben, Ace Volkmann Simpson, Yvonne Brunetto, and Tim Bentley. 2023. The Role of Team Compassion in Mitigating the Impact of Hierarchical Bullying. Journal of Management and Organization 8: 1419–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feijó, Fernando R., Débora D. Gräf, Neil Pearce, and Anaclaudia G. Fassa. 2019. Risk Factors for Workplace Bullying: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16: 1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunawan, Ria, Sutyas Prihanto, and Listyo Yuwanto. 2009. Causes and the intensity of workplace bullying. Anima, Indonesian Psychology Journal 25: 47–54. [Google Scholar]

- Hawley, Patricia H., and Anne Williford. 2015. Articulating the Theory of Bullying Intervention Programs: Views from Social Psychology, Social Work, and Organizational Science. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology 37: 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, Kristoffer, Eva Torkelson, and Martin Bäckström. 2022. Workplace Incivility as a Risk Factor for Workplace Bullying and Psychological Well-Being: A Longitudinal Study of Targets and Bystanders in a Sample of Swedish Engineers. BMC Psychology 10: 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huesmann, L. Rowell. 2018. An Integrative Theoretical Understanding of Aggression: A Brief Exposition. Current Opinion in Psychology 19: 119–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes-Morgan, Margaret, Kalin Kolev, and Gerry Mcnamara. 2018. A Meta-Analytic Review of Competitive Aggressiveness Research. Journal of Business Research 85: 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, Iqra, Amna Niazi, Sadia Nawaz, Muhammad Ali, and Mujahid Hussain. 2023. Impact of Workplace Bullying on Work Engagement among Early Career Employees. PLoS ONE 18: e0285345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Anya, Helena Nguyen, Markus Groth, and Les White. 2018. Workplace Aggression and Organisational Effectiveness: The Mediating Role of Employee Engagement. Australian Journal of Management 43: 614–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Richard M., Anna Marie Vu, and Anna Lau. 2013. Culture and Evidence-Based Prevention Programs. Handbook of Multicultural Mental Health: Assessment and Treatment of Diverse Populations: Second Edition. Amsterdam: Elsevier Inc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, Xiaoou, Jiatong Liu, and Zengxin Xue. 2022. Effects of Bullying Forms on Adolescent Mental Health and Protective Factors: A Global Cross-Regional Research Based on 65 Countries. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19: 2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matriano, Maria Teresa. 2024. Organizational Structure, Its Drawbacks and Shortcomings and Overall Impact to Organizational Behavior. Gsj 12: 1873–82. Available online: https://www.globalscientificjournal.com/researchpaper/Organizational_Structure_Its_Drawbacks_and_Shortcomings_and_Overall_Impact_to_Organizational_Behavior.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Menestrel, Suzanne. 2020. Preventing Bullying: Consequences, Prevention, and Intervention. Journal of Youth Development 15: 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, Julia, and Zena R. Mello. 2021. Time among the Taunted: The Moderating Effect of Time Perspective on Bullying Victimization and Self-Esteem in Adolescents. Journal of Adolescence 89: 170–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namie, Gary, and Ruth Namie. 2021. 2021 Workplace Bullying Institute: U.S. Workplace Bullying Survey. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research 61: 202–19. Available online: https://workplacebullying.org/2021-wbi-survey/ (accessed on 10 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, Morten Birkeland, and Ståle Valvatne Einarsen. 2018. What We Know, What We Do Not Know, and What We Should and Could Have Known about Workplace Bullying: An Overview of the Literature and Agenda for Future Research. Aggression and Violent Behavior 42: 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, Morten Birkeland, Live Bakke Finne, Sana Parveen, and Ståle Valvatne Einarsen. 2022. Assessing Workplace Bullying and Its Outcomes: The Paradoxical Role of Perceived Power Imbalance Between Target and Perpetrator. Frontiers in Psychology 13: 907204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, Scott K., Stephen Kulis, Flavio F. Marsiglia, Lori K. Holleran Steiker, and Patricia Dustman. 2014. A Continuum of Approaches Toward Developing Culturally Focused Prevention Interventions: From Adaptation to Grounding. Journal of Primary Prevention 35: 103–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omrani, Ghaida’a Abdullah. 2022. The Effects of Workplace Bullying on Task Performance and Job Stress in Saudi Arabia. Journal of Human Resource and Sustainability Studies 10: 315–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertiwi, Ayu Putri, and Aryana Satrya. 2022. Workplace Bullying and Supervisor Support Effects on Turnover Intention: The Work-Family Conflict Mediation. Proceedings of International Conference on Economics Business and Government Challenges 5: 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, Susan, Wahed Waheduzzaman, and Nikola Djurkovic. 2025. Impact of Organizational Culture on Bullying Behavior in Public Sector Organizations. Public Personnel Management 54: 184–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronha, Larissa, and Rosa Isabel Rodrigues. 2025. Relationship Between Mobbing and Organizational Performance: Workplace Well-Being and Individual Performance as Serial Mediation Mechanisms. Merits 5: 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossen, Eric, and Katherine C. Cowan. 2012. A Framework for School-Wide Bullying Prevention and Safety. Bethesda: National Association of School Psychologists. Available online: https://www.infocop.es/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Bullying_Brief_12-1.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Safe Work Australia. 2016. Guide for Preventing and Responding to Workplace. No. May 30. Available online: https://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/doc/guide-preventing-and-responding-workplace-bullying (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Sainz, Vanesa, and Beatriz Martín-Moya. 2022. The Importance of Prevention Programs to Reduce Bullying: A Comparative Study. Frontiers in Psychology 13: 1066358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salin, Denise. 2003. Ways of Explaining Workplace Bullying: A Review of Enabling, Motivating and Precipitating Structures and Processes in the Work Environment. Human Relations 56: 1213–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samsudin, Ely Zarina, Marzuki Isahak, and Sanjay Rampal. 2018. The Prevalence, Risk Factors and Outcomes of Workplace Bullying among Junior Doctors: A Systematic Review. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 27: 700–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silviandari, Ika Adita, and Avin Fadilla Helmi. 2018. Bullying Di Tempat Kerja Di Indonesia. Buletin Psikologi 26: 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, Samiksha, Sunil Rai, Geeta Thakur, Suchi Dubey, Anurag Singh, and Ujjwal Das. 2021. Prevalence and Impact of Workplace Bullying on Employees’ Psychological Health and Well-Being. International Journal of Health Sciences 6: 1380–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siswadi, Anwar. 2024. Kasus Terbaru Bullying Mahasiswa Calon Dokter Spesialis, FK Unpad Beri Sanksi 7 Senior. Tempo.Co. Available online: https://tekno.tempo.co/read/1915123/kasus-terbaru-bullying-mahasiswa-calon-dokter-spesialis-fk-unpad-beri-sanksi-7-senior (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Sorensen, Glorian, Emily Sparer, Jessica A. R. Williams, Daniel Gundersen, Leslie I. Boden, Jack T. Dennerlein, Dean Hashimoto, Jeffrey N. Katz, Deborah L. McLellan, Cassandra A. Okechukwu, and et al. 2018. Measuring Best Practices for Workplace Safety, Health, and Well-Being: The Workplace Integrated Safety and Health Assessment. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 60: 430–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spagnoli, Paola, Cristian Balducci, and Franco Fraccaroli. 2017. A Two-Wave Study on Workplace Bullying after Organizational Change: A Moderated Mediation Analysis. Safety Science 100: 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, Nicole M., Bryan Rodgers, and Gerard J. Fogarty. 2020. The Relationships of Experiencing Workplace Bullying with Mental Health, Affective Commitment, and Job Satisfaction: Application of the Job Demands Control Model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17: 2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Siwen, Huan Chen, Yang He, Fuyang Yu, Yupei Yang, Haixiao Chen, and Tao Hsin Tung. 2025. Workplace Bullying and Turnover Intentions among Workers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Public Health 25: 2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, Sandra. 2020. Hierarchies and Bullying: An Examination into the Drivers for Workplace Harassment within Organisation. Transnational Corporations Review 12: 162–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Shujuan, Lei Shi, Fang Dong, Xiao Zheng, Yaqing Xue, Jiachi Zhang, Benli Xue, Huang Lin, Ping Ouyang, and Chichen Zhang. 2022. The Impact of Chronic Diseases on Psychological Distress among the Older Adults: The Mediating and Moderating Role of Activities of Daily Living and Perceived Social Support. Aging & Mental Health 26: 1798–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).