Abstract

Modern social work is inseparable from the provision of timely and practical assistance to vulnerable populations, including forced migrants. In the context of increasing geopolitical instability and the growing influx of displaced people, social workers are increasingly required to serve this group not as exceptional but as regular clients. However, significant barriers—such as restrictive social policies and the inadequate preparation of social workers—limit forced migrants’ access to quality support services. This article examines the strengthening of core social work competencies in the learning process (e.g., through developing intercultural communication skills and applying experiential learning and trauma-informed methods). The article presents the results of an empirical study implemented within the Erasmus+ project “Improved Social Workers” in Lithuania and Cyprus. A mixed-methods research strategy combining observations, psychodiagnostic techniques, and reflexive analysis was employed in this study. Quantitative data revealed an increase in social workers’ communicative tolerance and a reduction in ethnocentrism. At the same time, qualitative analysis highlighted significant growth in both professional and personal aspects of the participants’ lives. Following training, both Lithuanian and Cypriot social workers reported improved intercultural communication, increased sensitivity to trauma, and enhanced professional skills. The findings underscore the importance of training social workers to effectively address the complex needs of forced migrants.

1. Introduction

Every year, the dynamics of migration around the world become increasingly complex. Military conflicts, climate change, and complex emergencies are changing the world we know. It has been estimated that, in 2020, 281 million people (3.6% of the world’s population) lived outside their country of birth. As of the end of 2024, the most recent reporting period, 123.2 million people had been forced to flee their homes globally due to persecution, conflict, violence, human rights violations, or events seriously disturbing public order. Unfortunately, more than 1 in every 67 people on Earth has been forced to flee their homes (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, UNHCR 2025). This figure, defined as the global number of international migrants, is almost double that in 1990 (European Commission 2023). With the increase in the number of migrants, the population of particularly vulnerable persons (forced migrants and refugees) is also growing (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, UNHCR 2023). While being a forced migrant is not inherently a vulnerability, the growing number of forced migrants and refugees increases the risk of a rise in structurally disadvantaged and potentially vulnerable groups due to systemic barriers and unequal access to services. The fundamental human rights of these groups are often violated, and they are at risk of social exclusion. However, it is essential to acknowledge that forced migrants are not treated equally across groups, nationalities, or contexts. In recent years—particularly since the beginning of the military conflict in Ukraine in 2022—there has been a noticeable shift in EU migration policy, with significantly more favorable and inclusive measures applied to Ukrainian forced migrants. The implementation of the EU Temporary Protection Directive (2001/55/EC) ensured immediate access to legal residence, employment, healthcare, education, social support, and family reunification, bypassing lengthy asylum procedures and detention. This situation highlights a form of positive discrimination that differs from the more restrictive and deterrent-oriented policies often applied to forced migrants from other regions, such as Syria, Afghanistan, Iraq, or Palestine.

Social work with forced migrants has a rich history in the profession, is rooted in local contexts, and aims to engage with and include local communities. While the core legal definition of a “refugee” has remained stable since its codification in the 1951 Refugee Convention, these interpretations and applications have evolved through regional instruments, such as the 1984 Cartagena Declaration and the 1969 OAU Convention. These instruments have broadened the scope of protection to include individuals fleeing generalized violence, environmental disasters, or human rights violations. In this context, the term “forced migrant” is used deliberately to encompass its broader meaning, including not only recognized refugees but also individuals granted asylum, subsidiary protection, or temporary protection. According to the International Organization for Migration (IOM 2019) and the European Migration Network (EMN) Glossary (2023), a forced migrant is an individual who is compelled to move due to threats to their life or livelihood, whether from conflict, persecution, environmental degradation, or development projects. Scholars (e.g., Jacobsen and Majidi 2023; Palattiyil et al. 2021; Stankovic et al. 2021) employ the term when analyzing displacement driven by political or social causes. As such, the concept highlights shared protection needs among diverse categories of displaced persons, extending beyond the narrow legal definition of refugee status.

Aspects such as the limited visibility and eligibility for formal welfare services of forced migrants, their temporal “liminality,” and their non-linear patterns of mobility have significant consequences for social work practice, research, and the education of social workers (Boccagni and Righard 2020). In this context, an important task for international social work is to create a system that involves communities and ensures they are at the center of efforts to strengthen the capacities of all social workers (Popescu and Alonzo 2021). Social workers themselves play an equally important role in this process. Research (Bartkevičienė and Bubnys 2012; Demidenko 2019; Štuopytė and Demidenko 2021) has indicated that social workers frequently serve as the primary and most influential figures in supporting forced migrants. Gustafsson et al. (2023) identified social workers as key individuals and social work as the main subject of migrant “integration.” Social workers play a crucial role in guiding migrants through the adaptation process, providing information and educational resources, and facilitating their integration into the host society. However, performing these functions requires not only professional training (education) for social workers but also competencies specific to working with forced migrants (e.g., working with traumatized individuals, ability to work in an intercultural environment).

The challenges faced by social workers require continuous learning and improvement of professional competencies. High-quality support that effectively responds to the needs of forced migrants can only be delivered by social workers who are adequately trained and engaged in continuous professional development. Boccagni and Righard (2020) have emphasized the need to invest in the reflexivity of students and practitioners of social work, given both the complexity of building up trust-based relationships with forcibly displaced people and the risk of cultivating essentialized, stigmatizing, or nativist representations about them. Experiential learning is a particularly effective method in social worker training (Štuopytė and Demidenko 2021), as it allows learning through personal experience, reflection, and practical action. The unique, independently evaluated experiences of the social worker help the learner to improve (Slušnys and Šukytė 2016). Social work is complex (Wolf-Branigin 2009) because it involves understanding emerging social movements, promoting human rights and psychological resilience in target populations, and understanding the interdependence of communities. In this context, taking into account the challenges faced by social workers when working with forced migrants, a project was developed and implemented—Enhanced Social Workers—enhancing intercultural communication competences for social workers in the provision of assistance to forced migrants (Project No. 2023-1-LT01-KA210-ADU-000151010). The aim of the project’s activities is to enhance the intercultural communication competencies of social workers in Lithuania and Cyprus through the use of experiential learning methods, which have been selected as the most suitable for this purpose (Gurova and Godvadas 2015; Štuopytė and Demidenko 2021). The primary direct target groups and beneficiaries of the project activities are social workers and refugee curators who assist forced migrants. Improving the competences of social workers is closely linked to greater opportunities for forced migrants to receive professional assistance and integrate more successfully into the host country’s society. As part of this project (April and August 2024), a study was conducted to improve the competencies of social workers which are necessary to assist forced migrants and refugees. This article aims to highlight attitudinal shifts among social workers supporting forced migrants in Cyprus and Lithuania during the training process. The research methods included analysis of the scientific literature, qualitative content analysis, the psychodiagnostics method, and observation.

2. Review of the Literature

The provision of support to individuals facing social exclusion is among the key functions performed by social workers, with forced migrants constituting being a particularly vulnerable group affected by such exclusion. Although the individual experiences of forced migrants in terms of integration are not homogeneous (Demidenko 2019), most migrants experience social exclusion. As a socially vulnerable group, forced migrants experience psychological and personal alienation (tendencies toward alienation in interpersonal relationships in the context of scientific and technological development) and socio-cultural segregation (Demidenko 2019). The overall experience of forced migrants in terms of integration (in various areas) is less successful than that of the local population (Spencer 2004; Phillimore and Goodson 2006; Gurung 2011; Tatar 1998, 2015; Hernandez and Cervantes 2011; Demidenko 2019), and these individuals’ traumatic experiences further complicate their situation.

In this context, social workers must be able to get to know their clients, understand their traumatic experiences, and strive to develop their competencies.

2.1. Trauma and Its Impact on Work with Forced Migrants

Forced migration, as a disruptive and often unplanned process, is associated with an increased risk of psychosocial and mental health challenges. This heightened risk stems from the need to rebuild personal relationships and social networks; the stress of navigating unfamiliar social, educational, cultural, or economic systems; and the broader impact of such systemic transitions (Kirmayer et al. 2007). To avoid conceptual ambiguity in discussing trauma, it is important to clarify that the term forced migrants, as used in this article, serves as an umbrella category that includes refugees, asylum seekers, as well as individuals holding humanitarian or other forms of legal status. Although not all forced migrants experience trauma-related disorders, research indicates that those most likely to be affected belong to the most vulnerable subgroup—refugees. Nevertheless, forced migrants with other legal statuses are also frequently exposed to cumulative stressors associated with displacement. These stressors, often sensory and ongoing in nature, can have a significant impact on psychological well-being. As Molendijk et al. (2024) note, many forced migrants suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, and anxiety, and benefit from psychological interventions such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR), expressive/art therapies, mindfulness-based approaches, narrative exposure therapy (NET), and psychoeducation, all of which are effective in reducing trauma-related symptoms. Among forced migrants, refugees constitute the group with the highest prevalence of trauma-related mental health conditions. For instance, the prevalence of PTSD among refugees can reach up to 37.9% (James et al. 2022), depression up to 75% (Slewa-Younan et al. 2015), and anxiety disorders up to 40% (Nguyen et al. 2022). For practitioners and service providers working with trauma-affected populations, it is essential to recognize the specific and context-dependent nature of stress experienced by forced migrants (Guskovict and Potocky 2018). A culturally sensitive approach is increasingly recognized as the most promising framework for understanding the diverse manifestations of trauma within this population (Maercker et al. 2019).

A growing body of contemporary scholarship on trauma and mental health underscores the critical importance of culturally sensitive approaches to care. For example, Kirmayer and Gómez-Carrillo (2023) highlighted the significance of adopting an eco-social perspective in both mental health theory and practice. Hinton and Bui (2019) proposed an intercultural framework for understanding trauma-related disorders, particularly in the context of PTSD. Additionally, Gross and Killikelly (2019) introduced the concept of sociosomatics, which further expands the culturally informed understanding of trauma and its manifestations.

According to recent research, even the experience of trauma-related grief and loss is influenced by the cultural context (Maercker et al. 2019). When it comes to assisting refugees, cultural differences often manifest themselves in typical behavior, ethnic, or national origin. These forms of identity are themselves cultural constructs based on norms and conventions (Maercker et al. 2019). When assisting traumatized forced migrants, it is essential to follow the principles of culturally sensitive assistance. In the context of providing support to refugees, cultural sensitivity performs several critical functions (Štuopytė and Demidenko 2024). First, it enables refugees to articulate their experiences and concerns in ways that are meaningful within their own cultural, familial, and community frameworks. Second, it assists professionals in interpreting the diagnostic relevance of symptoms and behaviors, as well as in understanding forced migrants’ culturally shaped expectations and normative assumptions. Third, it facilitates the development of support strategies and interventions that are culturally appropriate and responsive. Finally, attention to culture is essential not only for the effectiveness of interventions but also for their meaningful evaluation. Given this, professionals working with forced migrants need intercultural communication skills and essential knowledge about trauma and the current adaptation process of forced migrants (Štuopytė and Demidenko 2024). Social workers also need knowledge about the different situations of forced migrants in the pre-migration, migration, and post-migration phases.

Analyzing the psychosocial challenges faced by forced migrants, the World Health Organization (2006) underscores that the entirety of their lived experience—including past events, current circumstances, and anticipated future—unfolds as a process of transition through distinct phases. Five phases of the refugee crisis are identified:

- Catastrophe—marked by a sense of total collapse and overwhelming despair as individuals perceive their world to be falling apart.

- Self-determination—the moment of deciding to flee one’s country, often accompanied by a complex interplay of fear, necessity, and agency.

- Dissociation—frequently described by forced migrants as a sensation of “floating in the air,” reflecting a state of psychological detachment and confusion, often likened to a form of oblivion.

- Confrontation and reaction—a phase during which individuals begin to process their emotions and experiences. This stage often surfaces intense affective responses, including anger and aggression.

- The phase of reconciliation and new life—characterized by efforts to integrate past experiences and reorient toward the future, often involving the reconstruction of identity and the pursuit of stability in a new context (World Health Organization 2006).

It should be noted that even forced migrants living in a safe country of asylum can experience anxiety, depression, and chronic post-traumatic stress disorder (Molendijk et al. 2024; James et al. 2022). Trauma-induced mental health disorders are complex and must be assessed within the broader spectrum of mental illness, taking a holistic approach to individual trauma histories and evaluating each case separately (Gojer and Ellis 2014). Decision-makers, immigration officials, and social workers need to be trained to assess trauma-related conditions, taking into account the spectrum of mental health diagnoses, which includes not only PTSD but also other contexts, such as cultural, social, and political factors (Nowak et al. 2023). When providing psychosocial support to traumatized forced migrants, it is important to understand that a fundamental feature of all traumatic events (whether violence, natural disasters, military action, etc.) is the deprivation of power and a specific separation of the victim from other people (Sambucini et al. 2020). With this in mind, assistance should be based on restoring power to the traumatized person and establishing new, secure relationships (Sambucini et al. 2020).

In discussions on the provision of complex psychotherapeutic support for individuals who have experienced trauma, the importance of adequate training for all professionals involved should be strongly emphasized. Not only psychologists but also social workers must know the methods of working with people experiencing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), as well as understanding the conditions for their application and the principles of their operation (Štuopytė and Demidenko 2024). Psychologists and psychotherapists play a vital role in comprehensive psychosocial support. Their knowledge and skills are specific, but the role of social workers in the assistance process is also valuable (Štuopytė and Demidenko 2024). Gustafsson et al. (2023) highlighted the problem that social workers often lack the competencies to choose methods of activity or social work practices that would help in solving the problems faced by forced migrants. It is essential that each care provider clearly understands their role and that of their colleagues, as well as the work processes and methods, without creating unreasonable expectations for themselves or the client. Crucially, every professional working with traumatized individuals must be capable of establishing a positive, constructive, and empowering therapeutic relationship (Spinelli 2007). Such a relationship is a fundamental precondition for the recovery from psychological disorders and the restoration of social functioning (Spinelli 2007, 2014).

Researchers (Popescu and Libal 2018; Im and Swan 2021; Levenson 2020) have argued that trauma-informed care best reflects the preparedness of all helping professionals (not just psychologists or psychiatrists) for working with forced migrants who have experienced trauma. Trauma-informed care in work with forced migrants is an approach that recognizes the pervasive impact of pre-, during-, and post-migration trauma and integrates that understanding into all aspects of service delivery. It is underpinned by principles of safety, trust, empowerment, collaboration, cultural responsiveness, and avoidance of re-traumatization. Practitioners who adopt trauma-informed care view client symptoms—such as somatization or mistrust—as adaptive responses to trauma and engage migrants in culturally aware, participatory, and empowering ways to foster healing and resilience.

Knowledge about trauma and its consequences is also important for the protection of social workers themselves as it is well known that burnout, exposure to trauma, and secondary traumatic stress are occupational hazards for workers in the service sector (Guskovict and Potocky 2018). As social workers must be able to manage stress, knowledge of refugee trauma, social risks, and other factors involved in assisting can help to manage stress when working with this sensitive client group. Training social workers to acquire new skills and improve existing ones is becoming an important priority.

2.2. Experiential Learning Method in Social Work Education

Understanding forced migrants as a vulnerable client group means changing the attitude of social workers toward them and developing the competencies of social workers which are necessary for successful work. Analysis of scientific sources revealed that experiential learning theories (Kolb 1984; Kolb and Kolb 2018) and experiential learning methods are frequently employed in social work training. Cheung and Delavega (2014) identified the importance of the experiential learning model in the learning process of social workers, while the results of a qualitative study by Robinson et al. (2022) highlighted the benefits of experiential learning in developing and applying ethical values in future social workers. McBride (2024) discussed strengthening social work education through the use of case studies and the application of experiential learning theory by integrating simulations. Lorenzetti et al. (2022) emphasized that experiential learning is a crucial aspect of social worker training facilitating the integration of theory with practice. For this reason, experiential learning methods can be applied to the development of intercultural competencies in social workers (Mauro et al. 2023).

Why experiential learning? The four-stage cycle of experiential learning (experience, reflection, thinking, and action) is the most widely recognized and utilized concept in experiential learning theory (ELT) due to its simplicity and practicality (Kolb and Kolb 2018). According to scientists, this experiential learning cycle can be applied to the development of curricula that actively involve learners in the learning process, serving as an alternative to the overused and ineffective traditional information transfer model (Kolb and Kolb 2018).

According to McBride (2024), reflection is essential when developing competencies based on experiential learning theory (ELT) within the experiential learning cycle. Reflection provides training participants with the opportunity to closely examine themselves and their environment during a specific experience, to recognize the emotions accompanying the experience, and to share their observations with other participants in the experience (Godvadas et al. 2014). McBride (2024) emphasized that, when using the experiential training model, it is essential to include practical/simulation tasks in the practice course as this provides an opportunity to enhance the social worker’s skills and later apply them in real-world activities. The basis of experiential learning is activity or specific experiences. What is experienced during training later becomes the basis for social workers to reflect on the experience, get to know themselves and others, conclude, and discover what is important to them (Godvadas et al. 2014).

The training leader plays a crucial role in training, and their ability to work with a group and establish and maintain appropriate relationships is essential (Štuopytė and Demidenko 2021). In order to achieve change during experiential learning, a balance is needed between security, when we feel calm and stable, and tension, when there is a strong need to learn something new. Security for the participant during experiential learning is created by getting to know the group and its leader, providing the opportunity for the participant to choose how much to participate in activities, and offering and receiving support and mutual assistance (Godvadas et al. 2014; Štuopytė and Demidenko 2021).

Thus, experiential learning is effective for training social workers because it allows for learning through personal experience, reflection, and practical actions. With this in mind, a training program was developed and implemented for the participants of this study.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Process

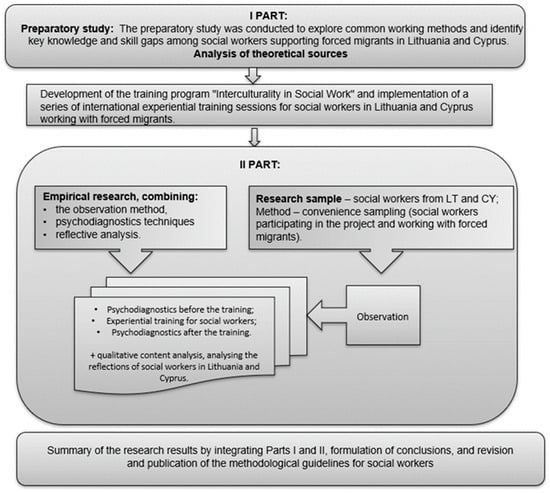

The article presents research findings obtained during the implementation of the international project “Enhancing Intercultural Communication Competences for Social Workers in the Provision of Assistance to Forced Migrants” No. 2023-1-LT01-KA210-ADU-000151010, funded by the EU Structural Fund Erasmus+. The project was carried out from 1 December 2023 to 31 December 2024 in Lithuania and Cyprus. It is important to note that the project’s funding had no influence on the conduct of the research or the integrity of its results. The research design is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The research design.

Preparatory stage. At the beginning of the project, a preparatory study was conducted to identify which working methods are most commonly used by social workers in Lithuania and Cyprus in their work with forced migrants, as well as to determine which knowledge and skills are most lacking among social workers in both countries who provide support to forced migrants. Based on the “world café” method, the preparatory study analyzed which working methods Lithuanian and Cypriot social workers lack when providing support to forced migrants. The world café method is a structured conversation process designed to foster knowledge exchange and collective creativity, where participants discuss thematic questions in small groups resembling a café setting (UNICEF 2024). The world café process took place in 8 intercultural discussion groups, where Lithuanian and Cypriot social workers shared their methods of working with forced migrants.

After each discussion in one “café,” the groups rotated, allowing ideas to travel and expand through participants. The structure and process of the world café method were as follows:

Preparation: A “café” atmosphere was created with 5 tables equipped with pencils and paper, each table seating 4 social workers.

Introduction: The facilitator explained the purpose of the process, the ground rules, and the structure of the forum.

Small Group Rounds: Three discussion rounds were held, each lasting about 20 min. Each round started with a discussion around a specific question. After each round, participants—except for the “table host”—moved to another table. The “table host” always stayed at their table and presented the key ideas from previous discussions to the new group.

Questions: Participants were asked three questions:

- What is the profile of your clients—forced migrants (nationality, characteristics, strengths, challenges)?

- What working methods do you most often use in your practice with forced migrants (similarities and differences in the work of Lithuanian and Cypriot specialists with forced migrants)?

- What innovative working methods and competences are most lacking for social workers when working with forced migrants?

Harvest: After the final round, a large collective discussion took place. The facilitator helped the “table hosts” to write down or post the main insights on large sheets visible to all. The world café process concluded with a synthesis that not only addressed the key questions but also highlighted aspects of intercultural communication between Lithuanian and Cypriot social workers.

The collected data were analyzed using qualitative thematic analysis to identify recurring themes and patterns. These insights informed the development of a training program tailored to the actual needs of social workers in both countries. The pilot study was conducted in January 2024 in Lithuania (with the participation of Cypriot and Lithuanian social workers).

The most pressing needs were identified in this study as the development of intercultural communication competencies, the provision of support for traumatized refugees, and the enhancement of social workers’ psychological resilience.

Based on the needs identified during the pilot study of social workers in Lithuania and Cyprus, training sessions were planned, using a variety of methods to develop inter-cultural communication competence, trauma-informed care, and psychological resilience.

Following the preparatory study, a training program was developed and implemented.

To assess the impact of the training program, psychodiagnostics attitude research was conducted before and after the training in order to monitor changes in the communicative attitudes of the participants. The psychodiagnostics study was conducted between April and August 2024. The study was then conducted in three stages:

In the first stage, before participating in the training, Lithuanian and Cypriot social workers underwent psychodiagnostics testing to assess their communication preferences. The first stage of the study took place in April 2024 in Cyprus, prior to the training.

In the second stage, social workers from Lithuania and Cyprus participated in joint training. The training took place in both Cyprus and Lithuania between April and August 2024 and consisted of two training sessions (each comprising four days of experiential learning). The participants were social workers from Lithuania and Cyprus working with forced migrants.

In the third stage, psychodiagnostics of intercultural communication among the study participants was conducted after they participated in the training. The third stage of the psychodiagnostics assessment took place in August 2024, following the final training session held in Lithuania.

3.2. Participants in the Study

This study employed non-probability purposive sampling, a method frequently used in small-scale or pilot studies when the research targets specialized sub-groups, such as social workers with experience working with forced migrants. Purposive sampling is especially appropriate in experiential interventions, where the aim is not statistical generalization but in-depth understanding within a specific context (Cohen et al. 2018). In accordance with the project’s aims, the target group consisted of social workers who work with forced migrants in Lithuania (N = 10) and in Cyprus (N = 10). In total, 20 social workers participated in the study, with ages ranging from 25 to 45 years (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of study participants (Lithuania and Cyprus).

Participants were recruited using a convenience sampling strategy, and involvement in both the training program and the research was voluntary. All participants had prior professional experience working with forced migrants, which ensured the relevance of their perspectives to the objectives of the study.

All participants involved in the project and the related research activities provided informed consent to participate by signing consent forms in accordance with established ethical research standards. The confidentiality of the data collected during the study was strictly maintained, with all research materials securely stored by the project applicant.

The demographic composition of participants shows that women were strongly dominant in both countries, reflecting broader gender trends within the social work profession. The distribution of professional experience demonstrates a relatively broad yet limited range (1–10 years in Lithuania and 1–8 years in Cyprus). This indicates that the sample included practitioners with a range of experience but no participants with long-term professional trajectories (i.e., more than 10 years). Such a sample may be considered suitable for experiential training and research as it allows less experienced professionals to become acquainted with new methods and to acquire practical knowledge during the experiential learning process. After the training, these competences can be compared across participants while also reflecting the professional realities of frontline social workers working with forced migrants in both countries.

3.3. The Training Program

The structure of the experiential education program analyzed was based on multi-band cultural contact, experiential learning, and the practice of social participation activities, as well as multicultural education. The training program consisted of three main module topics (Štuopytė and Demidenko 2024):

Module 1: Development of intercultural communication competence;

Module 2: Psychosocial characteristics of forced migrants;

Module 3: Practical guidelines for the application of methods.

The first and second modules consisted of both theoretical knowledge and practical skills, while the third module focused on consolidating practical skills. However, beyond the transmission of knowledge, each module integrated a strong experiential learning component. The training process created a multi-layered intercultural encounter: on the one hand, Lithuanian and Cypriot social workers interacted with one another in an intercultural setting; on the other hand, they engaged in simulations designed to reproduce situations involving a second intercultural context—their work with clients who are forced migrants from diverse countries and backgrounds.

In the first module, participants engaged in simulations in which they practiced establishing constructive and trust-based relationships with forced migrant clients while simultaneously learning to set professional boundaries. These exercises allowed social workers to rehearse the complexity of communication when cultural codes, expectations, and vulnerabilities differ across client groups.

The second module deepened the experiential dimension by introducing simulated cases in which clients not only came from different cultural backgrounds but also had experienced varied psychological traumas. In a safe training environment, social workers experimented with new methods for working with trauma-affected forced migrants. Importantly, simulations also emphasized the dual task of care: supporting clients while at the same time developing strategies for self-care. This was highlighted as essential for preventing burnout, given the emotional burden of working with traumatic client narratives.

The third module was oriented toward the safe application and integration of newly acquired knowledge and practical tools. Lithuanian and Cypriot participants experimented with methods such as metaphorical cards, selected elements of the MindSpring approach, and techniques of alternative communication. These tools were applied in practice-based simulations of real-life situations with forced migrants, thus enabling participants not only to test innovative methods but also to reflect collectively on their applicability across different socio-cultural contexts.

Accordingly, the training program can be characterized as a hybrid model of theoretical and experiential education, in which simulations and intercultural contact serve as mediating mechanisms between knowledge and practice. By situating professional learning within intercultural and trauma-informed contexts, the program fostered both the development of professional competence and the resilience of social workers facing the challenges of contemporary migration.

Systematic observation was carried out throughout all stages of the experiential learning process in order to assess the impact of the program and the experiential training on social workers. In addition, changes in participants’ communicative attitudes were evaluated by comparing pre- and post-training assessments by employing a psychodiagnostic method as the primary tool of measurement.

3.4. Study Methods

A mixed research strategy and a multi-method approach, combining observation methods, psychodiagnostics techniques, and reflective analysis, were utilized in this study. A group of social workers from Lithuania and Cyprus was observed over a specific period. Data was collected through repeated assessments conducted before, during, and after the training. The research team systematically recorded and analyzed the data to explore changes in participants’ attitudes toward working with forced migrants.

The following methods were used in the study:

- (a)

- Observation under controlled conditions, with an observer present.

- (b)

- Psychodiagnostics techniques designed to assess participants’ communication preferences.

- (c)

- Qualitative content analysis, analyzing the reflections of social workers in Lithuania and Cyprus.

The observation process was conducted during the experiential training sessions for Lithuanian and Cypriot social workers, allowing for the direct recording of participants’ behaviors, communication styles, and engagement in experiential learning activities. The researcher was present throughout the observation, ensuring systematic data collection within a structured setting.

Observation was carried out according to a predefined observation protocol, which highlighted key aspects such as participants’ activity in discussions, ability to apply new methods, intercultural communication strategies, and responses to simulated scenarios. The researcher recorded both quantitative indicators (e.g., frequency of participation in discussions and completion of practical tasks) and qualitative aspects (e.g., quality of interaction, depth of reflection, and emotional responses to situations involving forced migrants).

Moreover, the observation was non-invasive, aiming to minimize the influence of the study on participants’ behavior. The researcher documented observations, which were later analyzed to identify recurring themes, strengths, and challenges in the experiential learning process. This approach ensured that the observation data reflected genuine participant reactions and engagement levels, allowing for a systematic evaluation of the training’s impact on their professional competencies.

The study used psychodiagnostics techniques. Psychodiagnostics refers to the systematic application of psychological methods and tools to assess individual characteristics, including personality traits, emotional states, cognitive abilities, and attitudes. In this study, psychodiagnostics attitude assessment was employed before and after the training to monitor potential changes in the participants’ communicative attitudes toward working with forced migrants. This approach enabled the researchers to evaluate not only observable behavior but also underlying psychological dispositions that may influence professional interactions. It is important to note that one of the researchers holds qualifications in psychology and psychotherapy, which enables her to apply psycho-diagnostics methods validly and professionally.

A modified version of Boiko’s psychodiagnostic questionnaire of communicative attitudes (Raigorodskij 2015) was employed in this study. This instrument, widely used in psychological diagnostics, is designed to identify negative communicative attitudes that may interfere with effective interaction and social engagement. The questionnaire consists of 25 statements, to which respondents answer “Yes” or “No,” with each response assigned a fixed score according to the content of the statement. Scores are grouped into three dimensions:

- General communicative tolerance, indicating the overall level of communicative tolerance without focusing on specific target groups.

- Situational and professional communicative tolerance, reflecting attitudes toward particular individuals or colleagues, shaped by situational or professional contexts.

- Typical communicative tolerance, capturing preferences or biases toward particular social groups, such as immigrants, people with disabilities, or individuals of different nationalities.

This last dimension is particularly relevant for analyzing social workers’ communicative attitudes toward forced migrants. Changes observed in this dimension after the training are considered especially significant within the context of the study.

The assessment procedure involves summing the points assigned to each “Yes” or “No” response and calculating scores according to each of the three dimensions. The tool’s content validity is grounded in psychological theories of communicative barriers, attitudes, and social schemas. Its structured design and clear scoring system enable reliable data collection and analysis, making it suitable for use in intercultural research contexts.

In this study, the Boiko questionnaire was used in conjunction with observation and the analysis of participant reflections, providing a comprehensive understanding of the effects of the experiential training. While the instrument is practical and time-efficient, it has certain limitations: there are no standardized norms by age or gender, and data on cross-validation with other methods are lacking. Despite these constraints, the method provided valuable supplementary psychodiagnostic information, complementing qualitative observations of participants’ communicative behavior and engagement in experiential learning activities.

A qualitative content analysis was conducted to examine the written reflections of social workers from Lithuania and Cyprus following their participation in the training. The analysis employed a systematic coding process, combining open and axial coding to capture both the detailed and broader dimensions of participants’ experiences (Strauss and Corbin 1998). During open coding, each line of the written reflections was examined to identify and label meaningful units of information, addressing the questions “What is this about?” and “What is the point?” (Strauss and Corbin 1998). This line-by-line microanalysis allowed for the initial generation of categories, providing a granular understanding of participants’ perceptions, emotions, and learning outcomes. Open coding involved defining, naming, categorizing, and describing key elements of the data, creating a foundation for deeper analytical interpretation.

Following open coding, axial coding was applied to reassemble the fragmented data and explore the relationships between categories and subcategories. This step enabled the researchers to refine and integrate the initial codes, producing more precise and contextually grounded explanations of the phenomena under investigation. Through this iterative process, three primary categories emerged from the reflections: (1) improved intercultural communication skills, (2) a deeper understanding of the traumatic experiences of forced migrants, and (3) strengthened professional and personal competencies of social workers.

The combination of open and axial coding provided both descriptive and interpretive insights, allowing the research team to capture the complexity of participants’ experiences while maintaining methodological rigor. This approach not only facilitated the identification of key learning outcomes, but also highlighted how the training impacted social workers’ professional practice, intercultural sensitivity, and personal growth.

3.5. Research Ethics and Limitations

The following ethical principles of the study were followed (Orb et al. 2001):

- Autonomy: The study participants had the right to decide for themselves whether to participate in the study.

- Goodwill: The study participants were informed about the purpose and goals of the study, as well as the format of data submission. The data provided did not affect the status or work situations of the study participants.

- Justice: All data provided by the study participants were analyzed.

- Confidentiality: The study participants were not asked to provide their last name or status information.

It should be noted that forced migrants are considered a vulnerable population, and social workers frequently encounter the traumatic experiences of these individuals. Therefore, involving social workers in the research requires a professional, sensitive, and ethically grounded approach. The research was led by a professional psychologist with over 20 years of experience in psychological counselling for refugees and a specialist in trauma psychology. The project was implemented by the governmental social organization (Lithuania), the Cyprus NGO, and a Lithuanian NGO. These institutions work directly in Lithuania and Cyprus with social workers who, in turn, work with forced migrants. The project partners obtained the consent of all participants to participate in the research and training, as well as to use their data for research purposes, in accordance with the principles of confidentiality.

Limitations of the study: The small convenience sample and the high motivation of the participants limit the applicability of this study’s results. Both Lithuanian and Cypriot social workers voluntarily participated in the experiential training and the study, expressing a desire to acquire new knowledge and skills, which may have influenced the results obtained. Furthermore, although this study sought to minimize researcher bias in various ways, the findings may still be subject to the subjective interpretation of the research team.

4. Data and Analysis

4.1. Preparatory Study Data

During the preparatory study, an analysis of the opinions of social workers in Lithuania and Cyprus regarding the cultural and psychosocial characteristics of forced migrants was conducted, revealing no significant differences. Using “world café” method, the participants were asked to reflect on three key areas: (1) the profile of their clients—forced migrants, including nationality, personal characteristics, strengths, and challenges; (2) the working methods most commonly applied in their practice, with attention to similarities and differences between Lithuanian and Cypriot contexts; and (3) the innovative working methods and competences that social workers perceive as most lacking when working with this target group. This approach not only allowed for the identification of common trends across the two countries but also highlighted shared challenges in addressing the complex needs of forced migrants. The results of the “world café” process revealed that social workers from both countries highlighted several key characteristics and challenges faced by their clients who are forced migrants:

- −

- Forced migrants represent diverse cultural backgrounds, necessitating that service providers demonstrate cultural sensitivity and competence. Notably, Lithuania hosts a larger proportion of Russian-speaking forced migrants, which reduces language barriers compared to the situation in Cyprus.

- −

- The majority of forced migrants have experienced trauma, often accompanied by mental health issues, with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) being the most prevalent condition.

- −

- Forced migrants encounter significant challenges related to acculturation and adapting to new cultural norms and societal expectations within the host country.

- −

- Forced migrants span various age groups (including children, families, and older adults), each presenting distinct needs and vulnerabilities.

- −

- Cultural factors significantly shape communication styles, trauma coping strategies, and help-seeking behaviors among forced migrants. Unlike Cyprus, Lithuania has recently seen an influx of Ukrainian war refugees. Given the historical and cultural proximity between Ukrainian and Lithuanian cultures, their communication patterns and trauma coping mechanisms tend to be more culturally aligned than those from Arab cultural backgrounds.

- −

- The majority of forced migrants have experienced the loss of social networks and separation from loved ones due to forced displacement.

- −

- Both Lithuanian and Cypriot social workers emphasize that adopting an individualized approach to working with forced migrants or refugees is essential.

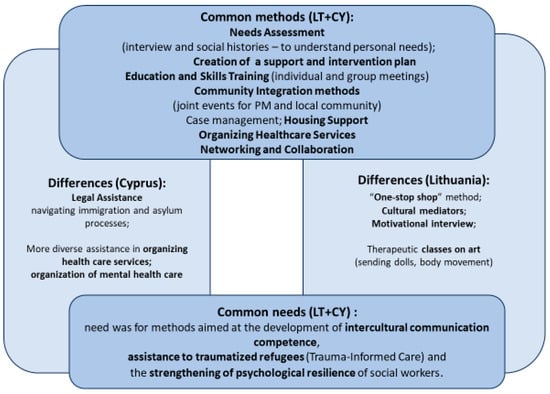

After identifying the profiles of the study participants—forced migrants—and analyzing the opinions of social workers in Cyprus and Lithuania on the psychosocial characteristics of forced migrants, the study focused on the working methods most commonly used in practice when assisting forced migrants (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Methods used by social workers when working with forced migrants and their training needs.

The comparative analysis of practices in Lithuania and Cyprus reveals both convergences and divergences in the methods applied to support refugees and migrants.

Common methods (Lithuania and Cyprus): Several core methodologies are consistently employed across both national contexts. Central to these practices is the systematic assessment of individual needs, typically undertaken through structured interviews and the collection of social histories. This process informs the development of individualized support and intervention plans, which serve as the foundation for tailored assistance. Additionally, both contexts prioritize education and skills training, delivered through individual consultations as well as group sessions, to foster self-sufficiency and integration. Community integration strategies, such as joint activities involving both refugees/migrants and host community members, are also widely applied, facilitating intercultural engagement. Furthermore, case management, housing support, and the coordination of healthcare services are integral components of assistance, complemented by an emphasis on networking and inter-institutional collaboration to ensure a holistic and coordinated response.

Distinctive approaches in Cyprus and Lithuania: In the Cypriot context, a notable distinction is the provision of legal assistance, particularly in navigating the complexities of immigration and asylum procedures. Cyprus also demonstrates a broader scope of healthcare-related interventions, with explicit emphasis on the organization of mental health services, reflecting an acknowledgment of the psychological vulnerabilities of refugee populations.

Lithuania, in contrast, is characterized by several innovative practices. The “one-stop shop” model consolidates multiple services within a single access point, thereby reducing bureaucratic barriers and increasing accessibility. The deployment of cultural mediators facilitates intercultural communication and mutual understanding between refugees and host institutions. In addition, Lithuania employs motivational interviewing as a psychosocial technique to encourage personal agency and resilience. Furthermore, therapeutic art-based interventions, including practices such as doll-making and body movement therapy, are utilized to support emotional expression and trauma recovery.

Shared needs (Lithuania and Cyprus): Despite these contextual variations, both countries report similar unmet needs. There is a pronounced demand for methodologies that strengthen competency in intercultural communication, enabling more effective interactions between refugees and host communities. Moreover, the necessity of trauma-informed care is emphasized, underscoring the prevalence of psychological trauma among refugees. Finally, attention is drawn to the need for measures aimed at enhancing the psychological resilience of social workers, acknowledging the emotional and occupational challenges associated with sustained engagement in refugee support services. It should be noted that the results of this preparatory study, conducted using the “world café” method, were utilized in the development of the training program. The methods used in the training program are presented in more detail in the methodological guidelines (Štuopytė and Demidenko 2024).

4.2. Data and Analysis of the Psychodiagnostic Study

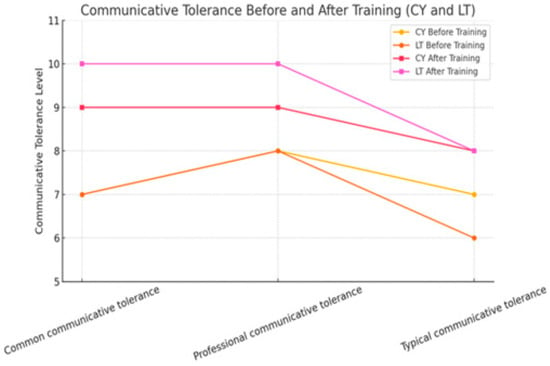

The communicative attitudes of Lithuanian and Cypriot social workers engaging with forced migrants were assessed psychodiagnostically using a modified Boiko methodology. This assessment was administered at two time points: before and after the experiential training program.

Before the start of the activities, most participants in both groups (Lithuanian and Cypriot) had an above-average level of standard communicative tolerance (N = 7 in the Cypriot group and N = 7 in the Lithuanian group). This reveals a common approach to others, reflecting general preferences shaped by the participants’ own experiences, values, and attitudes.

Similar results showed situational and professional communicative tolerance to specific persons or workers. However, the level of typical communicative tolerance, which shows preferences for such groups as immigrants, people with disabilities, and individuals from different nationalities, was at a moderate level. Some social workers from Lithuania (N = 1) and Cyprus (N = 2) were identified as having negative preferences and ethnic stereotyping.

Following participation in the program, the level of standard communicative tolerance increased (N = 10 in the Lithuanian group and N = 9 in the Cyprus group). The general preferences of participants became overwhelmingly positive (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Communicative tolerance before and after training.

Analyzing the results of the psychodiagnostic study, it should be noted that no statistically significant differences were identified between the attitudes of Lithuanian and Cypriot social workers. It should also be noted that the experiential education program’s impact is identified in the area of typical communicative tolerance, after new experiences of direct cross-cultural communication. After presenting the traumatic experiences of refugees using experiential learning methods and multicultural education, negative attitudes and ethnic stereotyping of participants from both groups decreased. After training, only one social worker’s attitude remained at a lower level of communicative tolerance. This suggests that targeted experiential training may have a positive impact on communicative attitudes.

4.3. Data and Analysis of the Reflection

These empirical results are complemented by the analysis of reflections. The analysis of social workers’ reflections on the training they experienced was conducted using the content analysis method and identified three essential categories: (1) improved intercultural communication skills; (2) more profound understanding of the traumatic experiences of forced migrants; (3) strengthened professional and personal skills of social workers.

Participants’ reflections provide insights into the development of improved intercultural communication skills:

…we talk a lot about interculturality and work with refugees from different countries, but I had never had such a practical ‘touch’ of what intercultural communication really is until now(CY 4)

…I’ve never been a closed person, but being in an intercultural environment, learning to be even more open to everything that is ‘different’… helped me become even more open…(CY 7)

…there came a deeper understanding that we are very different, and at the same time, very similar as human beings. Truly useful training…(LT 2)

…it was very interesting to participate in training together with colleagues from another country… this kind of ‘double internationalism’—refugees from different countries, and colleagues—social workers—who are foreigners… I think I’ve become even more open to people from other cultures…(CY 9)

The qualitative findings indicate that participants enhanced their intercultural communication skills through the experiential training. They reported gaining practical insights into working in culturally diverse settings, becoming more open to differences, and developing a deeper understanding of both diversity and shared human experiences. Training alongside colleagues from other countries further reinforced these skills and perspectives.

The following are participants’ reflections, highlighting their deeper understanding of the traumatic experiences of forced migrants:

…I knew about migrant trauma because I work with them. However, the training was more about understanding than just knowing. Now, I understand them differently.(CY 1)

…that realisation that it is not so much about what happened, but how and to what extent the traumatic event impacts the current life of the forced migrant—this is a new, different kind of understanding of how my clients feel as they ‘return’ to their trauma every day…(LT 5)

…I studied trauma during my university years, but this training helped me better understand both the refugees and their trauma, and how to work with trauma(LT 7)

…it helped me better understand the traumas and experiences of refugees(CY 10)

The results suggest that participants developed a deeper understanding of trauma-informed approaches through the training. They reported moving beyond theoretical knowledge to a more nuanced comprehension of how past traumatic experiences affect refugees’ current lives and daily functioning, enhancing their capacity to respond empathetically and effectively in practice.

The analysis of the reflections also identified strengthened professional and personal skills of social workers:

…I trust myself more because I learned and tried several new working methods. They are proactive but also easy to apply in my work with forced migrants(CY 9)

I have grown as a professional and experienced significant personal growth.(CY 8)

During the intercultural training, I had the opportunity to get to know Lithuanian colleagues and their work with refugees, and I gained new skills in intercultural communication, trauma-informed care, MindSpring, and other methods. Truly valuable…(CY 2)

…in the training, I did not just learn—I experienced… and that is probably more important than just theoretical knowledge. I grew both as a professional and as a person. I really liked that this was a practical intercultural training—I got to know and learn together with Cypriot colleagues(LT 10)

…I really enjoyed the in-depth methods in intercultural communication, support for trauma survivors, metaphorical cards, alternative communication, and more… I feel stronger because I’ve tested these methods myself and can confidently apply them in my work…(LT 6)

…at work I often deal with refugees who have experienced trauma, and I used to feel uncomfortable. I’m not a psychologist, and I worried that my wrong reaction might harm the client… now I feel more confident…(CY 5)

…we work with people from different ethnic backgrounds and thought we already understood cultural differences, but that knowledge wasn’t fully grounded. The practical training helped me feel unafraid of being open to those differences…(LT 4)

The findings indicate that participants experienced growth on both professional and personal levels. They reported increased confidence in applying new methods, including trauma-informed approaches and intercultural communication techniques, in their work with forced migrants. Engagement in practical, experiential training allowed participants to consolidate theoretical knowledge through hands-on experience, fostering both skill development and self-assurance. Moreover, many highlighted that the training enhanced their openness, adaptability, and overall professional resilience, reflecting a meaningful integration of personal and professional growth.

5. Discussion

The results of this study complement those reported in other scientific research. The preparatory study conducted with social workers in Lithuania and Cyprus revealed significant gaps in existing training programs, particularly regarding methods that enhance intercultural competence, trauma-informed care, and practitioners’ psychological resilience. These findings align with the theoretical insights of Bartkevičienė and Bubnys (2012); Demidenko (2019); Boccagni and Righard (2020); and Štuopytė and Demidenko (2021), who emphasized the importance of context-specific, tailored training for social workers in increasingly complex and multicultural work environments.

The results from psychodiagnostic assessments and the observation process indicate that experiential learning has a positive influence on participants’ communication attitudes in both countries. Following training, the social workers demonstrated higher levels of general communicative tolerance and more positive attitudes toward intercultural interactions. These outcomes suggest that direct engagement in cross-cultural communication, combined with a deeper understanding of refugee trauma and experiential learning approaches, can significantly reduce ethnic stereotyping and biases. Similar arguments have been made by scholars such as Spencer (2004); Phillimore and Goodson (2006); Gurung (2011); Tatar (2015); Demidenko (2019); Major et al. (2013); and Montgomery and Foldspang (2008), who highlighted that negative societal attitudes toward migrants hinder integration and well-being.

Reflections further emphasize the need for training programs that directly address social workers’ practical and emotional needs. Observed improvements in intercultural communication skills corroborate previous research on the value of experiential learning in social work education (Godvadas et al. 2014; Mauro et al. 2023; Štuopytė and Demidenko 2021), which highlights its role in fostering empathy, critical self-reflection, and the capacity to navigate complex, culturally diverse contexts—essential competencies when working with forced migrants.

Participants also reported a deeper understanding of trauma and its manifestations among forced migrants, indicating strengthened trauma-informed care competencies. This aligns with Levenson (2020); Popescu and Libal (2018); and Im and Swan (2021), who argued that trauma-informed approaches are essential in preparing social workers to support clients with complex post-traumatic experiences. Integrating trauma-informed principles into social work training enhances practitioners’ ability to respond sensitively and competently to the lived realities of forced migrants.

Overall, this study contributes to the growing body of research advocating for a holistic, reflective, and participatory approach to social work training. The findings support the development of evidence-based programs that enhance technical skills while fostering values of empathy, tolerance, and cultural humility. These results highlight the importance of systematic investment in experiential and trauma-informed training models to better equip social workers to meet the multifaceted needs of forced migrants.

6. Conclusions

Forced migrants represent an increasingly visible and vulnerable client group in social work practice. Their complex needs, shaped by trauma, displacement, and cultural dislocation, require sensitive and specialized support. The aim of the “Enhanced Social Workers” project, conducted in Lithuania and Cyprus, was to address these challenges through the development of a targeted experiential training program for social workers. During the preparatory phase, the key needs of Lithuanian and Cypriot social workers regarding intercultural experiential learning and innovative work methods were identified. Based on these insights, the program was designed to enhance skills in intercultural communication, trauma-informed care, and psychological resilience.

To evaluate the program’s effectiveness, a three-stage empirical study was conducted, integrating multiple methods—psychodiagnostics, observation, and reflection analysis—to examine social workers’ communicative attitudes, engagement in experiential learning, and reflections on the training’s benefits. Psychodiagnostic data revealed increased communicative tolerance and reduced ethnocentric attitudes, observations showed growing participation in intercultural simulations, and qualitative reflections indicated both professional and personal development. Analysis of participant reflections highlighted three key themes: improved intercultural communication skills, a more nuanced understanding of the trauma experienced by forced migrants, and strengthened professional and personal capacities. Participants emphasized that experiential and collaborative learning—conducted alongside colleagues from different national and cultural contexts—enhanced both their competence and confidence in their practice. They reported increased awareness of trauma, improved intercultural skills, and greater confidence in applying innovative methods. Experiential learning and cross-national collaboration played crucial roles in strengthening practical skills and fostering more empathetic attitudes.

The program’s impact extended beyond knowledge acquisition to changes in social workers’ approaches toward culturally diverse and trauma-affected clients. Participant feedback emphasized the training’s relevance, depth, and effectiveness. Overall, the findings underscore the importance of sustained investment into social worker training grounded in experiential learning and trauma-informed principles. Strengthening professional capacities through participatory action research is crucial for providing responsive and humane support to forced migrants in complex migration contexts.

The distinctiveness of this study lies in its integrative and cross-cultural design, which surpasses conventional training programs focused solely on intercultural competence or trauma-informed care. The study was innovative in several respects. First, it adopted a multi-method approach, combining observation, psychodiagnostic assessment, and reflective analysis to monitor changes in social workers’ communicative attitudes and professional perspectives, enhancing the depth of the findings. Second, its cross-cultural comparative framework, involving social workers from Lithuania and Cyprus, allowed for the analysis and comparison of attitudes toward working with forced migrants in different socio-cultural and institutional contexts. Third, experiential learning in a dual intercultural context promoted attitudinal change throughout the program as participants learned together across national and cultural boundaries, experiencing both community belonging and cultural representation. In summary, although the individual elements of the training (intercultural competence, trauma-informed care, and experiential learning) are not new, the combination of methods, cultural perspectives, and an integrated curriculum within a shared learning context makes this intervention innovative in design, implementation, and cross-national scope.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.D. and E.Š.; methodology, V.D. and E.Š.; software, V.D. and E.Š.; validation, V.D. and E.Š.; formal analysis, V.D. and E.Š.; investigation, V.D. and E.Š.; resources, V.D. and E.Š.; data curation, V.D. and E.Š.; writing—original draft preparation, V.D. and E.Š.; writing—review and editing, V.D. and E.Š.; visualization, V.D. and E.Š.; supervision, V.D. and E.Š.; project administration, V.D. and E.Š.; funding acquisition, V.D. and E.Š. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partly funded by the European Commission under the Erasmus+ program, project No. 2023-1-LT01-KA210-ADU-000151010.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (1975, revised in 2013) and approved by the Kaunas Kolegija Higher Education Review Board (protocol No D3-3 and date of approval 1st February 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to ethical and privacy concerns.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to our study participants and the project “Enhanced Social Workers“ (Strengthening the Competences of Social Workers)—Strengthening the intercultural communication skills of social workers assisting forced migrants; partners from the Cyprus NGO “KIBOTOS “ and the Social Projects Institute. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funding sponsors had no role in the design of the study, in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, and in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EMN | European Migration Network |

| ELT | Experiential learning theory |

| IOM | International Organization for Migration |

| NGO | Non-governmental organization |

| PTSD | Post-traumatic stress disorder |

| UNHCR | United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees |

| UNICEF | United Nations Agency for Children |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Bartkevičienė, Aistė, and Remigijus Bubnys. 2012. Socialinis Darbas su Prieglobstį Gavusiais Užsieniečiais: Metodinė Priemonė. Šiauliai: Šiaulių Kolegija. [Google Scholar]

- Boccagni, Paolo, and Erica Righard. 2020. Social work with refugee and displaced populations in Europe: (dis)continuities, dilemmas, developments. European Journal of Social Work 23: 375–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, Monit, and Elena Delavega. 2014. Five-Way Experiential Learning Model for Social Work Education. Social Work Education 33: 1070–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Louis, Lawrence Manion, and Keith Morrison. 2018. Research Methods in Education, 8th ed. New York: Routledge and Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Demidenko, Valentina. 2019. Educational Factors of Forced Migrants’ Integration into Society. Ph.D. dissertation, Kaunas University of Technology, Kaunas, Lithuania, June 20. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. 2023. Knowledge for Policy: Increasing Significance of Migration. Available online: https://knowledge4policy.ec.europa.eu/increasing-significance-migration_en (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- European Migration Network (EMN) Glossary. 2023. Available online: https://home-affairs.ec.europa.eu/networks/european-migration-network-emn/emn-asylum-and-migration-glossary_en (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Godvadas, Paulius, Gintė Jasienė, and Artūras Malinauskas. 2014. Patirtinio Refleksyvaus Mokymo Taikymo Vietos Bendruomenėse Metodika. Vilnius: VšĮ Kitokie Projektai. [Google Scholar]

- Gojer, Julian, and Adam Ellis. 2014. Post-traumatic Stress Disorder and the Refugee Determination Process in Canada: Starting the discourse. New Issues in Refugee Research 207: 3–26. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/media/post-traumatic-stress-disorder-and-refugee-determination-process-canada-starting-discourse-dr (accessed on 9 May 2025).

- Gross, Carina Salis, and Clare Killikelly. 2019. Sociosomatics in the context of migration. In Cultural Clinical Psychology and PTSD. Edited by Andreas Maercker, Eva Heim and Laurence J. Kirmayer. Göttingen: Hogrefe Publishing, pp. 41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Gurova, Tatjana, and Paulius Godvadas. 2015. Patyriminio ugdymo metodo veiksmingumas dirbant su socialiai pažeidžiamais jaunais žmonėmis. Socialinis darbas. Patirtis ir metodai 15: 97–118. Available online: https://www.lituanistika.lt/content/69393 (accessed on 9 May 2025).

- Gurung, Yogendra Bahadur. 2011. Migration from Rural Nepal: A Social Exclusion Framework. Himalaya, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies 31: 12. Available online: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol31/iss1/12 (accessed on 9 May 2025).

- Guskovict, Kristen L., and Miriam Potocky. 2018. Mitigating Psychological Distress Among Humanitarian Staff Working With Migrants and Refugees: A Case Example. Advances in Social Work 18: 965–82. Available online: https://journals.indianapolis.iu.edu/index.php/advancesinsocialwork/article/view/21644/22058 (accessed on 9 May 2025). [CrossRef]

- Gustafsson, Kristina, Eva Norström, and Linnéa Åberg. 2023. Social workers as targets for integration. Nordic Social Work Research 13: 550–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, Donald J., and Wendy D. Cervantes. 2011. Children in Immigrant Families: Ensuring Opportunity for Every Child in America. Report from the Foundation for Child Development. First Focus. New York: Foundation for Child Development. Available online: https://www.fcd-us.org/children-in-immigrant-families-ensuring-opportunity-for-every-child-in-america/ (accessed on 9 May 2025).

- Hinton, Devon E., and Eric Bui. 2019. Variability of PTSD and trauma-related disorders across cultures: A study of Cambodians. In Cultural Clinical Psychology and PTSD. Edited by Andreas Maercker, Eva Heim and Laurence J. Kirmayer. Göttingen: Hogrefe Publishing, pp. 23–39. [Google Scholar]

- Im, Hyojin, and Laura E. T. Swan. 2021. Working towards Culturally Responsive Trauma-Informed Care in the Refugee Resettlement Process: Qualitative Inquiry with Refugee-Serving Professionals in the United States. Behavioral Sciences 11: 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Internation Organization for Migration (IOM). 2019. Glossary on Migration. Available online: https://www.scribd.com/document/678130052/2019-IOM-Glossary-on-Migration?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Jacobsen, Karen, and Nassim Majidi, eds. 2023. Introduction to the handbook on forced migration: A critical take on forced migration today. In Handbook on Forced Migration. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- James, Peter Bai, Andre M. N. Renzaho, Lillian Mwanri, Ian Miller, Jon Wardle, Kathomi Gatwiri, and Romy Lauche. 2022. The prevalence of anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder among African migrants: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research 317: 114899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirmayer, Laurence J., and Ana Gómez-Carrillo. 2023. A cultural-ecosocial systems view for psychiatry. Frontiers in Psychiatry 14: 1031390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirmayer, Laurence J., Morton Weinfeld, Giovanni Burgos, Guillaume du Fort, Jean-Claude Lasry, and Allan Young. 2007. Use of health care services for psychological distress by immigrants in an urban multicultural milieu. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 52: 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolb, Alice, and David Kolb. 2018. Eight important things to know about the experiential learning cycle. Australian Educational Leader 40: 8–14. Available online: https://learningfromexperience.com/downloads/research-library/eight-important-things-to-know-about-the-experiential-learning-cycle.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Kolb, David A. 1984. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development. Hoboken: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Levenson, Jill. 2020. Translating Trauma-Informed Principles into Social Work Practice. Social Work 65: 288–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzetti, Liza, Diane Lorenzetti, Jeffery Halvorsen, Meena Durrani, and Rita Dhungel. 2022. Community-Based Experiential Learning: An Emerging Framework for Transformative Learning in Social Work Education. International Journal of Critical Pedagogy 12: 99–124. Available online: https://janeway.uncpress.org/ijcp/article/id/827/ (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Maercker, Andreas, Eva Heim, and Laurence J. Kirmayer, eds. 2019. Cultural Clinical Psychology and PTSD. Göttingen: Hogrefe Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Major, Joe, Jane Wilkinson, Kip Langat, and Ninetta Santoro. 2013. Sudanese young people of refugee background in rural and regional Australia: Social capital and education success. Australian and International Journal of Rural Education 23: 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauro, di Maura, Birgit Sandu, and Johanna Pacevicius. 2023. Building Intercultural Competences: A Handbook for Regions and STAKEHOLDERS. Assembly of European Regions (AER). Bologna: ART-ER S. cons. p. a. [Google Scholar]

- McBride, Gabriella. 2024. Enhancing social work education: A praxis-based teaching case study on integrating simulation through experiential learning theory. Social Work Education 44: 811–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molendijk, Marc, Charlotte Baart, Jan Schaffeld, Zeynep Akçakaya, Charlotte Rönnau, Marike Kooistra, Rianne de Kleine, Celina Strater, and Louise Mooshammer. 2024. Psychological Interventions for PTSD, Depression, and Anxiety in Child, Adolescent and Adult Forced Migrants: A Systematic Review and Frequentist and Bayesian Meta-Analyses. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy 31: e3042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, Edith, and Anders Foldspang. 2008. Discrimination, mental problems and social adaptation in young refugees. European Journal of Public Health 18: 156–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Thomas P., Maria Gabriela Uribe Guajardo, Berhe W. Sahle, Andre M. N. Renzaho, and Shameran Slewa-Younan. 2022. Prevalence of common mental disorders in adult Syrian refugees resettled in high income Western countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry 22: 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, Anna Christina, Niklas Nutsch, Tessa-Maria Brake, Lea-Marie Gehrlein, and Oliver Razum. 2023. Associations between postmigration living situation and symptoms of common mental disorders in adult refugees in Europe: Updating systematic review from 2015 onwards. BMC Public Health 23: 1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orb, Angelica, Laurel Eisenhauer, and Dianne Wynaden. 2001. Ethics in Qualitative Research. Journal of Nursing Scholarship 33: 93–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palattiyil, George, Dina Sidhva, Amelia Seraphia Derr, and Mark Macgowan. 2021. Global trends in forced migration: Policy, practice and research imperatives for social work. International Social Work 65: 1111–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillimore, Jenny, and Lisa Goodson. 2006. Problem or Opportunity? Asylum Seekers, Refugees, Employment and Social Exclusion in Deprived Urban Areas. Urban Studies 43: 1715–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, Marciana L., and Dana Alonzo. 2021. Creating SPACE: A Conceptual Framework for Rights-Based International Social Work and Social Development. Advances in Social Work 21: 1064–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popescu, Marciana L., and Kathryn Libal. 2018. Social Work With Migrants and Refugees: Challenges, best practices, and future directions. Advances in Social Work 18: i–x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raigorodskij, Daniil. 2015. Prakticeskaja Psichodiagnostika: Metodiki i Testi. Samara: Bakhrakh-M. [Google Scholar]