Abstract

Cross-national public opinion surveys show that a significant majority of young people are frequently exposed to hateful content on social media, which suggest the need to better understand its political implications. This systematic narrative literature review addresses three key questions: (1) Which factors have been explored in political science as the main drivers of hate speech on social media? (2) What do empirical studies in political science suggest about the political consequences of online hate speech? (3) What strategies have been proposed within the political science literature to address and counteract these dynamics? Based on an analysis of 79 research articles published in the field of political science and international relations retrieved from the Web of Science Core Collection, this review found that online hate is linked to social media platform policies, national and international regulatory frameworks, perceived threats to in-group identity, far-right and populist rhetoric, politically significant events such as elections, the narratives of traditional media, the post-truth environment, and historical animosities. The literature shows that hate speech normalizes discriminatory behavior, silences opposing voices, and mobilizes organized hate. In response, political science research underscores the importance of online deterrence mechanisms, counter-speech, allyship, and digital literacy as strategies to combat hate during the social media era.

1. Introduction

Hate speech, generally defined as expressions of abuse that target individuals or groups based on their religion, race, ethnicity, nationality, gender and/or disability (Kearns et al. 2022), remains a persistent problem on social media platforms. Cross-national public opinion surveys indicate that a significant majority of young people are exposed to hateful content on social media (Reichelmann et al. 2021), and there is evidence that such exposure has adverse effects on mental health, intergroup/interpersonal interaction, and socialization (Keighley 2022; Müller and Schwarz 2023). Hate speech on social media has also significant political implications. While political actors such as governments, leaders, civil society groups, and international organizations have been recognized as critical to address and counteract hate speech (Car and Immenkamp 2025; Michalon 2025), current studies suggest that online hate is also used as a tool to advance certain political goals such as mobilizing political support, (re)constructing in-group/out-group boundaries, and shaping public policies and discourse (Ridwanullah et al. 2024). The aim of this review is to situate the growing body of political science research that examines how political factors both contribute and constrain the spread of online hate.

This paper, through a systematic narrative literature review, asks three key questions with the aim of stimulating critical reflection and debate in the field. The first question is ‘Which factors have been explored in political science as the main drivers of hate speech on social media?’ Research on communication, media and psychology has emphasized that hateful online activity can be explained by sociodemographic characteristics, attention-seeking behavior, hedonic entertainment preferences, social identity, lack of clear social media rules and regulations, the frequency of use of social media, and personality traits such as lack of empathy (Frischlich et al. 2021; Schmid et al. 2024). This review discussed alternative explanations in political science research, such as the role of populist rhetoric, the impact of elections, the silencing of political opposition, and national and international legal frameworks. The second question is ‘What do empirical studies in political science suggest about the political consequences of online hate speech?’ This review synthesized evidence from political science scholarship and showed that online hate speech reinforces social hierarchies, undermines political visibility and participation of marginalized groups and politicians, and strengthens exclusionary agendas promoted by far-right actors. The final question is ‘What strategies have been proposed within the political science literature to address and counteract these dynamics?’ This review focused on unique perspectives that political science studies bring to broader discussions on combating hate speech. While research on computer science has focused on developing automated hate speech detection techniques, such as TF-IDF, lexicon-based methods, and deep learning, communication and media studies have explored ethical considerations and challenges in social media environments and social media users’ perceptions of content moderation systems (Ben-David and Matamoros-Fernandez 2016; Matamoros-Fernández 2017; Moore 2018; Zhang et al. 2018; Zhang and Luo 2019). This review identified that political science studies have mostly emphasized the role of online platform governance, restrictive deterrence, counter-speech, social sanctioning, elite influence, digital activism, effective allyship, and youth media literacy.

This review also showed that political science scholarship draws on a diverse set of theoretical frameworks to explain the drivers, consequences and countermeasures of hate speech on social media. Social identity theory has been used to understand how in-group/out-group dynamics fuel prejudice and exclusion, while queer theory and intersectional feminism has been used to explain how online hostility is further structured through heteronormative and intersecting axes of race, gender, sexuality, religion, and class. The networked agenda-setting model explains how traditional media framing can spill over into hostile discourse on social media, and the discursive opportunity structure framework emphasizes how low-cost digital networking facilitates organized online hate. Spiral of silence theory accounts for how fear of isolation discourages individuals from challenging discriminatory behavior, whereas social learning theory posits how exposure to hateful or extremist content, particularly among younger users, might normalize such discourse within peer networks. Deterrence theory, in return, illustrates how sanctions can regulate hateful behavior. Taken together, these perspectives provide a multi-layered account of online hate, spanning micro-level effects on individual attitudes and behavior, meso-level dynamics of group identity and socialization, and macro-level processes of political communication and institutional response.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. The next section discusses the reasons behind hate speech. The third section explores its political consequences. The paper then presents the suggested strategies for addressing online hate speech. It concludes with the discussion of results, limitations of the existing study, and directions for future research.

2. Materials and Methods

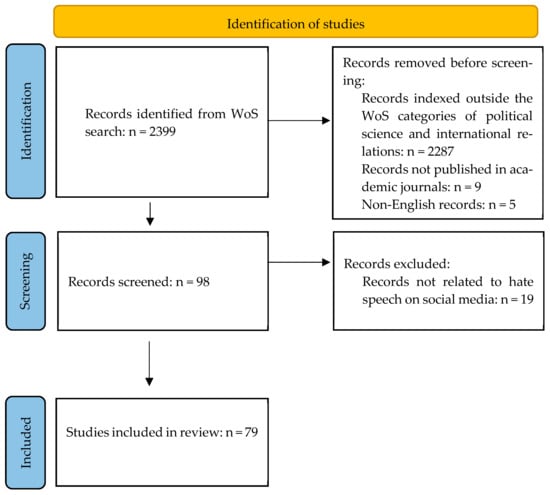

This paper employs a narrative literature review, which shifts focus from categorizing studies by methodological approaches and bibliographic characteristics to survey the state of knowledge in the field and synthesize key findings, provoking arguments, policy implications, and practical suggestions (Baumeister and Leary 1997). A weakness of narrative reviews is considered as the lack of systematic criteria on how to gather related literature. Following Ferrari’s (2015) recommendation, to increase transparency in the selection criteria, this paper adopted the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) criteria to identify the relevant political science research as presented in Figure 1 (Page et al. 2021).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

The literature search was conducted by the author on 27 October 2024 using the Web of Science (WoS) Core Collection, which was selected for its comprehensive coverage of peer-reviewed journals and its consistent editorial standards that ensure reliability and comparability across studies (Mongeon and Paul-Hus 2016). The search included combinations of the terms “hate speech,” “racist,” “sexist,” “racism,” and “sexism” with “social media,” “Twitter”, “YouTube” and “Facebook”. No filters were applied regarding publication year or search field. To ensure disciplinary coherence, the search was restricted to peer-reviewed journal articles published in the WoS categories of Political Science and International Relations. This approach guaranteed relevance to the theoretical and methodological frameworks commonly used in the field. This search initially identified 103 articles.

To focus solely on English-language publications, one Russian, two Italian, and two Spanish articles were excluded, narrowing the selection to 98. Limiting the review to English helped avoid inconsistencies in translation that could affect the interpretation of key concepts such as hate speech and racism, which often carry different meanings across languages. Also, covering non-English publications would have required extensive multilingual resources beyond the scope of this project. A further manual screening eliminated 19 articles that were unrelated to online hate speech. These articles appeared in the initial search because the keywords matched terms in the topic, title, journal name, abstract or keywords, but their content focused on topics like digital feminism or consent in childbirth, which are not directly relevant to hate speech on social media. The final dataset consists of 79 relevant articles, listed in Appendix A. Each article was analyzed for its contributions to three main areas: (1) drivers of online hate speech, (2) political consequences of such discourse, and (3) mitigation strategies proposed within the political science literature.

3. Results

3.1. Drivers of Hate Speech

A large body of research in computing, communication, and media studies has examined the drivers of online hate speech, emphasizing the interplay between algorithms, platform policies, technical features, and governance structures (Matamoros-Fernández 2017; Siapera and Viejo-Otero 2021; Tan 2022). One recurring theme is the lack of a standardized definition of what constitutes hate across different platforms (Hietanen and Eddebo 2022; Korre et al. 2025). Content flagged as hateful on one platform may remain unmoderated on another, undermining overall efforts to foster safe online communication. Political science scholarship has extended this debate by suggesting that platforms’ flexible definitions of harm, violence, and hate speech are shaped by shifting political climates and existing power hierarchies. Their choices tend to offer greater protection to socially and politically dominant groups while leaving marginalized communities more exposed to abuse, thereby reinforcing whose experiences are deemed worthy of protection (DeCook et al. 2022). This is particularly evident on fringe platforms like 4chan, 8chan, and Gab, which, as scholars have shown, rely on more relaxed definitions of hate speech and enforce related moderation rules less strictly compared to mainstream sites (Rieger et al. 2021). Hobbs et al. (2024), for example, examined extremist rhetoric toward Muslims and Jews across Gab, 4chan, and Reddit. They found that during the Trump presidency and after the 2021 Capitol riot, fringe platforms became key spaces for far-right groups coalescing around White and Christian nationalist ideologies, where religious minorities were persistently depicted as foreign threats.

Mainstream global social media sites, by contrast, tend to operate with stricter but still broad guidelines. Their moderation target severe and visible forms of harm, such as statements depicting “Muslims as barbarians,” while allowing symbolic or implicit forms of boundary-making to persist, for example, comments like “Muslim food smells so weird” (DeCook et al. 2022; Vidgen and Yasseri 2020, p. 69). Social media platforms’ moderation mechanisms also do not involve traditional gatekeeping practices that filter content before being published. The responsibility for detecting and moderating hate posts are usually distributed among various actors, including platform administrators, human moderators, end-users, and algorithmic tools. This fragmented approach often results in non-complementary strategies that leave room for hate speech to persist (Konikoff 2021). Adding to the complexity, the rules and definitions governing hate speech on social media sites are subject to frequent, and often undocumented, changes over time (Dubois and Reepschlager 2024). A notable example of this problem is the incident documented by Caldevilla-Domínguez et al. (2023), where Facebook allegedly changed its algorithm during the Ukraine war without public notice to allow negative comments about Russians. Such unannounced changes make it difficult for users to track policy evolution and leave them uncertain about whether a content will face moderation. The policy changes also usually address specific set of issues within particular political contexts. For example, when Twitter suspended President Donald Trump following the Capitol Riot on 6 January 2021, human rights activists from the Global South criticized the platform for selectively applying its suspension and hate speech rules. They brought attention to similar instances of online behavior by political leaders in their own countries, which they believed warranted similar intervention but were overlooked (Konikoff 2021). Einwiller and Kim (2020), through interviews with online content providers in the United States, Germany, South Korea, and China, also found significant variation in platform governance strategies across countries. In China, platforms commonly used preventive blocking to avoid hosting politically and commercially sensitive content and encouraged users to report harmful online communication directly to state authorities. Both South Korean and Chinese platforms also avoided encouraging counter-speech in their policies compared to those from the United States and Germany.

Examining the policy documents of three major platforms (Facebook, Twitter (now X), and YouTube), DeCook et al. (2022) demonstrated that the strategically selected definitional frameworks and moderation policies were a sign of how mainstream social media sites perceived their roles in the political and digital spaces. They suggested that the American media and technology corporations “driven by certain cyberlibertarian ideals” prioritized decentralized self-regulation with a focus on organizational interests and political pressure rather than legal oversight addressing structural injustices (DeCook et al. 2022, p. 73). In general, by moderating more physical and obvious forms of harm, the mainstream platforms showed at very least an impression of concern while sidestepping contentious issues. The vague rules and definitions enabled platforms to evade accountability without threatening their business interests and brand image (Kim 2024).

Studies reviewed here have also pointed out that legal inconsistencies in regulating social media across different parts of the world create ambiguity in online practices (Mchangama and Alkiviadou 2021). Illustrating this diversity, Tan (2022) compared regulatory frameworks in the United Kingdom, Australia, and New Zealand. The United Kingdom explored imposing statutory duties of care on social media platforms, recognizing online hate speech as a form of harm and aiming to hold platforms accountable for user safety. However, these policy efforts were criticized for their vague definitions of hate and the high legal threshold needed to pursue violations. Australia adopted a more structured approach; major platforms signed a code developed under Australian legislation that defines key terms such as harm, freedom of expression, misinformation, and disinformation. Meanwhile, New Zealand lacked specific laws addressing online hate speech and relies primarily on social media platforms to self-regulate in accordance with general safety standards.

Beyond these three countries, other nations have also adopted diverse strategies. Einwiller and Kim (2020) reported that Germany’s Network Enforcement Act required social media platforms to swiftly remove illegal content, while South Korea’s Network Act allowed temporary blocking of harmful accounts. Duy (2020) showed that the Norway Supreme Court ruled that hateful content targeting specific individuals or groups, particularly when they lacked relevance to public debate, falls under Norway’s hate speech legislation, reinforcing the principle that online platforms were not spaces where speech was entirely unrestricted. De Gregorio and Stremlau (2023) claimed that in many African countries, governments took a more forceful approach, resorting to slowing down internet access or imposing full shutdowns rather than working collaboratively with social media platforms to address harmful content. Both approaches were criticized—the first approach for framing “online violence as individual acts” instead of recognizing it as “organized” and “networked”, and the second, for suppressing political discourse, activism, and information-sharing (De Gregorio and Stremlau 2023; Galpin 2022, p. 165). Within this context, social media platforms often justified their noncompliance with national regulatory efforts in regions like Africa and Asia by framing their concerns as a defense of freedom of speech and a resistance to censorship. However, the assumption that all regulatory efforts are inherently repressive or noneffective undermines legitimate calls for hate speech regulation. Moreover, scholars have highlighted that by refusing to engage with local governance frameworks, social media companies consolidated control over digital spaces and denied local governments the opportunity to address region-specific challenges (De Gregorio and Stremlau 2023; Irving 2019; Wilson 2022). Within the European context, a European Parliament directive in 2022 emphasized that “what is illegal offline has to be illegal online”, reflecting the EU’s intent to “take back control from big and US-based enterprises” and create a “golden standard” for digital regulation (Schlag 2023, p. 269). The European Union’s Digital Services Act aims to harmonize digital regulation among Member States by imposing clear obligations on online platforms, regarding illegal content, disinformation, freedom of expression, media pluralism, and user safety. However, as Schlag (2023) argued achieving uniform standards across the EU has remained a challenge due to the EU’s limited competence over criminal law and the diverse interpretations of free speech among member states.

As a driver of hateful language on social media, political science research has also focused on perceived threats to in-group identity. Social identity theory suggests that individuals strive to maintain a positive image of their ingroup and emphasize negative characteristics of outgroups to reinforce group boundaries and enhance self-esteem. Hate speech directed at the disadvantaged often serves to exert power, justify own social status, and legitimize others’ social exclusion (Başpehlivan 2024; Ibrahim 2019; Mlacnik and Stankovic 2020; Unlu and Kotonen 2024; Vera 2023). For example, a study by Said-Hung et al. (2023) examining Tweets from Spanish political actors found that hateful discourse was often expressed through anti-immigrant, xenophobic, and misogynistic messages, rather than through general insults. These posts emphasized intergroup differences and blamed non-Spanish individuals for societal problems and violence. Examining the Facebook pages of the United Kingdom Independence Party and Spain’s far-right party VOX, Lilleker and Pérez-Escolar (2023) found that posts framing immigrants as burdens on social and health services or as competitors for local jobs often attracted hateful comments. Ukrainian refugees, who were viewed as sharing core European values, received less hate than Muslim immigrants, who were portrayed as culturally incompatible. Vera (2023) demonstrated that racist tweets surged when Jaime Vargas, the president of Ecuador’s largest indígena organization, urged security forces to defy government orders. This call acted as a trigger for the progovernment community (the in-group), prompting them to engage more rapidly with racist content than with nonracist content. Likewise, Sánchez-Holgado et al. (2023) similarly observed an increase in hateful comments targeting trans individuals after Spain’s government passed the Trans Law, which allowed gender self-identification, with transwomen frequently portrayed as threats to cisgender women and children.

Multiple other studies have also emphasized how gender identity threats prompt misogynistic responses. For example, Pettersson et al. (2023) examined a 2021 Finnish video that ridiculed the Prime Minister Sanna Marin and her women-led government. They showed that far-right populist discourse framed liberal-feminist politicians advocating for minority rights as internal enemies and as incompatible with their idealized image of a traditional hierarchical society. In a similar vein, Meriläinen’s (2024) demonstrated that, in Finland, male ministers occupying traditionally masculine roles such as the defense or finance ministries received less hate speech compared to male ministers in roles perceived as feminine, such as education or social services. Moreover, female ministers were particularly vulnerable to hate speech when they held traditionally masculine portfolios. In Blanco-Herrero et al.’s (2023) study women journalists in Spain, Italy, and Greece reported experience of harassment significantly more than their male colleagues. Radics and Abidin (2022) brought attention to how policing and criminalization of homosexuality in Singapore reinforced restrictive gender roles, isolated LGBTQ+ individuals and increased their exposure to online hate speech. Tembo (2024) discussed how the YouTube video ‘Sesa Joyce Sesa’, produced in the lead-up to Malawi’s 2014 elections, exemplified the ways cultural and religious discourse marginalize women in politics. The video, allegedly created by the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), targeted President Joyce Banda, portraying her as unfit to govern solely because of her gender. Drawing on patriarchal norms, the campaign equated Banda’s leadership with disorder, using imagery of sweeping dirt to symbolize her removal from public life. Religious metaphors further reinforced the idea that women belong in the private sphere and should not assume positions of authority (Duy 2020).

The poststructuralist approach suggests that social identities do not have a priori existence, and instead become meaningful through discourse (Zhang 2020). Political science literature has specifically emphasized how right-wing populist discourse plays a central role in constructing ‘otherness’ by framing certain groups as threats and reinforcing social hierarchies, defined as “the ranked esteem that is accorded to social groups” (Breyer 2025, p. 810), on social media. Populist leaders accentuate group differences and amplify fears of the ‘other’ by using “hyperbolic language, black-and-white dichotomies, and metaphors of conflict to evoke emotions such as fear, resentment and anger,” thereby drawing voter attention and distinguishing themselves from mainstream parties (Breeze 2019, p. 89; Kentmen-Cin et al. 2025). They also rely on strategic authenticity to “legitimize impoliteness and exclusivism”, which in turn “validate also extreme expressions of social exclusivism, such as nationalism, sexism, and racism” (Enli 2025, p. 94). Together, these rhetorical strategies foster the proliferation of online hate and signals to individuals that such framing is socially acceptable (Siegel and Badaan 2020). Askarzai (2022), for example, examined right populist Senator Pauline Hanson’s tweets on a burka ban in Australia, and found that her tweets attracted similar orientalist and Islamophobic narratives depicting Muslims as potential terrorists, hyper-masculine, and unwilling to assimilate. Bhatt et al. (2024, p. 288) identified that Trump’s referencing COVID-19 as “Chinavirus” triggered racial consciousness in White Americans “both in terms of in-group pro-white affinity and significant out-group racial and ethnic animosity.” Consequently, the frequency of racist comments, specifically towards those with Asian heritage increased. Dai et al.’s (2024) analysis of Tweets from the United States found similar results. Trump’s rhetoric was associated with a rise in anti-Asian hate speech on Twitter across counties nationwide. This finding implied that the influence of political leaders’ scapegoating language transcends political boundaries and affects the attitudes of a wide range of voters. Baladrón-Pazos et al.’s (2023) study revealed a different pattern. They examined whether the Spanish political parties’ Twitter activity fostered hate speech and increased polarization in the first 60 days of the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022. Their results showed that hateful speeches by more radical parties did not yield higher engagement compared to more moderate parties’ messages.

There are also studies that highlight how far-right actors leverage the opportunities presented by social media to amplify their messages targeting immigrants, minority groups, and political opponents. The far-right extremism is fundamentally built upon doctrines of racial and patriarchal superiority through narratives of existential threats that can only be mitigated through radical measures. Digital platforms enable these actors to create echo chambers beyond their immediate personal or community networks for spreading and normalizing their radical viewpoints (Berger et al. 2020; Hobbs et al. 2024; Marcks and Pawelz 2022; van Haperen et al. 2023). For example, Scrivens’s (2024) analysis of posts by both violent and non-violent right-wing extremists on the Stormfront Canada forum revealed that non-violent right-wing communities primarily shared ideological content with anti-government and conspiratorial themes, while violent counterparts concentrated more on mobilization efforts through extremist anti-Semitic rhetoric. Fangen (2020, p. 465) found that anti-Islamic Facebook groups in Norway used dehumanizing language to depict Muslims as unsophisticated and culturally inferior, and as security threats, claiming they were “worth nothing”. Moreno-Almeida and Gerbaudo (2021) analyzed internet memes from Moroccan far-right Facebook pages and found that the far-right accused progressive women and LGBTQ+ community of being an internal enemy and weakening traditional Moroccan family values.

However, scholars caution against a blanket assumption that all far-right discourse universally targets immigrants, women and LGBTQ+ individuals, as such generalizations ignore the global hierarchies, socio-political dynamics and historical contexts. For example, Fiers and Muis (2021) demonstrated that European far-right parties adapted their targets of existential threat to the “discursive opportunities” available in their national cultural environment. These parties often used a dual strategy in which they framed progressive values such as gender equality and LGBTQ+ rights as threats to cultural, natural, and moral order, while simultaneously referring to these very rights as markers of their own cultural superiority, with which they justify criticism of patriarchal practices in Muslim communities and thus reinforce anti-immigrant and Islamophobic sentiments. Their exploitation of gender equality in anti-Islam campaigns might be therefore rarely reflected in their broader narrative. Zhang (2020) analyzed how Chinese right-wing commenters on the social media platform Zhihu constructed national identity and global imaginaries. The study revealed that the 2015 refugee crisis in Europe and the 2016 presidential election in the United States were pivotal moments that exposed Chinese users to Western far-right rhetoric, which they reinterpreted to criticize Western liberalism. Adopting a realist authoritarian and social-Darwinist perspective, users framed China’s focus on economic growth and social order as signs of national superiority, while attributing the West’s decline to the rise of egalitarian and postmaterialist values promoted by the so-called white left.

Several studies have highlighted a connection between politically significant events and the proliferation of online hate. For example, Hobbs et al. (2024) found that anti-Jewish rhetoric increased after the 2017 Unite the Right rally in the United States. Similarly, misogynistic verbal attacks against Julia Gillard intensified after she became the first female Prime Minister of Australia in 2010 (Sawer 2013). Elections, in particular, serve as pivotal moments with broad media coverage and high public engagement, creating fertile ground for the spread of extremist narratives. Siegel et al. (2021) linked the 2016 United States presidential election to a rise in hate speech on social media, while, during the 2016 Romanian parliamentary elections, Meza et al. (2018) observed an increase in hate speech targeting welfare recipients, influenced by the Social Democrat Party’s campaign. These findings indicate that political leaders, who are, ideally, “responsible for minimizing the risk of social disorder through community reassurance”, may instead activate online hate and social othering through divisive rhetoric, particularly during electoral campaigns (Burnap and Williams 2015, p. 224).

Studies in political science have also recognized the role traditional media plays in shaping hate speech. The networked agenda-setting model suggests that traditional news outlets highlight important issues in public agenda, determine the emotional tone surrounding them and also how those individual topics are contextually linked in a broader narrative. The networked approach is critical for understanding the substantive and affective cues that individuals depend on to make sense of complex news stories (Su et al. 2020). Building on this model, Meza et al. (2018), for example, highlighted that hate speech targeting refugees and Muslims in Romania on Facebook corresponded with two events: peaks in media coverage of the European refugee crisis in 2015 and 2016 and the Social Democratic Party’s nomination Sevil Shhaideh, a Muslim woman, as a prime ministerial candidate. Similarly, in Hungary, there was a surge in mentions of the topics of violence, “refugees, Muslims, religious holidays, government and stupidity” following news reports about assaults on women during the 2015/16 New Year’s Eve celebrations in Cologne, Germany (Meza et al. 2018, p. 40).

Scholars have also drawn attention to the post-truth environment, where “the contemporary hybridized media” often strategically shares “disinformation, fake news and rumor bombs” on controversial issues to capture audience attention (Galpin and Vernon 2024, p. 424). Such media coverage can translate into broader online hatred and distrust, particularly against reputable minority opinion leaders. Galpin and Vernon (2024) have shown how queer theory and intersectional feminism explain online hate speech directed at minoritized political experts in the post-truth era by revealing the discursive processes that shape whose knowledge counts as legitimate. From a queer theoretical perspective, expertise is not only a matter of competence but is embedded in heteronormative frameworks. Online discourses of toxic masculinity attempt to exclude women and queer individuals from the category of expert, and thus from knowledge production, by positioning masculine science as rational and objective while devaluing research that acknowledges positionality, embodiment, and gendered experiences. Intersectional feminism further suggests that these exclusions do not operate along single axes of identity but through intersection of gender, race, sexuality, religion, and class. An example is the case of women academics in the United Kingdom who were presumed to be non-British and faced significant online vitriol during the Brexit debate after right-wing newspapers sensationalized and undermined their expertise (Galpin and Vernon 2024).

Lastly, existing studies have shown that historical animosities, postcolonial legacies, and collective memories of trauma can shape a society’s emotional culture and influence online group interactions (Baker and Rowe 2013; Meza et al. 2018). For example, Serrao (2022) demonstrated how social media reinforced longstanding prejudice against communities from Northeast Brazil (nordestinos), rooted in 19th-century whitening policies and sustained through cultural production and internal migration. During the 2014 and 2018 presidential elections, support from nordestinos for the left-wing Workers’ Party (Partido dos Trabalhadores) and President Dilma Rousseff triggered spikes in xenophobic hate speech on online platforms, with Southeastern Brazilians portraying nordestinos as historically lazy, incompetent and welfare dependent. These digital hostilities revealed the postcolonial emotional legacies that continue to define group boundaries and notions of African heritage and Blackness in Brazil, fueling online and offline abuse.

3.2. The Consequences of Online Hate Speech

Political science research has critically examined how online hate speech affects minorities, political actors, and collective action. An important line of research is whether individuals who rely on social media for communication and news are more prejudiced compared to those who use traditional media. The underlying argument is that exposure to hate speech on social media normalizes discriminatory behavior, as digital platforms often lack the normative constraints and gatekeeping mechanisms found in traditional media. This normalization process deepens societal divisions and reinforces polarizing views. To test this argument, Soral et al. (2020) analyzed data from a two-wave nationwide online survey in Poland to assess how different media consumption patterns related to Islamophobic attitudes and the acceptance of anti-Muslim hate speech. The study found that individuals who frequently used digital media showed significantly higher levels of Islamoprejudice and greater acceptance of hate speech compared to those with lower digital media use. However, all groups showed similar levels of secular criticism of Islam, indicating that increased digital media use does not necessarily correspond to greater political awareness.

Another line of research has focused on the silencing effects of persistent exposure to online hate speech. Drawing on spiral of silence theory, scholars argue that when hate escalates into extreme abuse, it can isolate victims through fear and ultimately deter them from expressing their views and participating in public discourse (Chaudhry and Gruzd 2020; Noelle-Neumann 1974; Tembo 2024). This is an important area of inquiry for political science because far right actors, in particular, use isolation and silencing techniques on social media to reproduce political marginalization and polarization (Said-Hung et al. 2023). For example, Galpin (2022) reported that UK Labour MP Jess Phillips reduced her Twitter presence following a rape-related tweet by far-right YouTuber Carl Benjamin, which in turn hindered her campaign efforts and interactions with voters. Similarly, Sawsan Chebli, a Muslim member of Germany’s Social Democrat Party, deactivated her Facebook account after facing misogynistic and racist attacks, driven by the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) for her advocacy against sexism.

An alternative strand of research has examined the toll hate speech takes on political office holders and candidates. Constructive criticism is essential for a functioning democracy, enabling politicians to understand their constituents’ needs and concerns. However, when criticism escalates into abuse, in the forms of threats, harassment, and defamation, it can harm politicians’ mental health, sense of safety and willingness to engage in public discourse, thereby also degrading the quality of democratic debate (Pedersen et al. 2024; Petersen et al. 2024). Cross-country studies highlighted the prevalence of online hate speech targeting politicians. In Germany, for example, over half of surveyed local mayors reported experiencing personal insults and hostility on social media (Bauschke and Jäckle 2023). These issues were particularly acute for women and LGBTQ+ politicians. In the United Kingdom, during the European Parliament elections, a majority of women candidates faced abusive and sexist online comments during their campaigns (Vrielink and van der Pas 2024). Trauthig’s (2024, p. 158) study of Facebooks posts in Libya showed that hate speech against women politicians often included calls for violence, portraying them as “criminal, worthy of rape, sexual exploitation and religious castigation”.

Political science has also explored the role of social media in enabling organized hate and violence through the lens of the discursive opportunity structure framework. This approach emphasizes how social media platforms expand the tools available to political activists, facilitating the dissemination of messages, increasing legitimacy, and recruiting new members. Unlike earlier social movements, this fourth wave of activism allows individuals to participate with minimal effort and cost. For instance, users can support causes by retweeting, using strategic hashtags, or joining social media groups, without requiring formal memberships or advanced coordination (Anselmi et al. 2022). These networked interactions with like-minded people, including those who would otherwise be difficult to reach, foster group solidarity and motivate individuals to engage in similar hateful acts, thereby legitimizing radicalized content (Ndahinda and Mugabe 2024; Williams et al. 2023). Social media is also instrumental in enforcing in-group norms through public shaming, for example, policing members of the majority who express empathy for or solidarity with marginalized communities (Schissler 2024). Lastly, social media allow attackers to coordinate their actions efficiently by sharing the information about targets and insult methods, bypassing traditional organizational structures (Trauthig 2024; Wahlström and Törnberg 2021).

3.3. Countering Online Hate Speech

Social media sites have combated hate speech via three strategies: automated detection techniques, human moderators, and user reports. However, all three methods have drawbacks. Automatic hate-speech detection may fail to capture symbolic forms of hate, manual reporting systems can be slow or inconsistent in addressing harmful content, and marginalized users may lack the tools or knowledge needed to navigate these systems effectively (Galpin 2022; Konikoff 2021; Matamoros-Fernández 2017; Matamoros-Fernández and Farkas 2021). Beyond these technical and procedural challenges, the success of hate speech regulation also depends on broader structural conditions. Social media companies must have a business incentive and legal motivation to act against hate speech, and the countries in which they operate must offer clear, consistent, and enforceable legal frameworks on free speech, hate speech, and digital regulation. Given these complexities, political science scholars have emphasized the need for a multifaceted approach that includes user sanctions, transparent regulatory frameworks, engagement in counter-speech, and allyship (Chaudhry and Gruzd 2020; Ndahinda and Mugabe 2024; Wilson 2022).

Building on deterrence theory, Yildirim et al. (2023) tested an innovative approach to reducing hate speech by issuing suspension warnings to individuals engaging in such behavior on social media. The study found that warnings, especially those stressing the legitimacy of penalties, significantly reduced hate speech on Twitter by encouraging users to reflect on the consequences of their language and thus fostering self-regulation. Beyond proposing such alternative mechanisms, political science research has also challenged the effectiveness of existing moderation practices. Chaudhry and Gruzd (2020), for example, showed that real-name policies, such as those enforced on Facebook, were insufficient to curb hate speech when attackers viewed their targets as deserving of hatred. Their study of racist comments on France’s burkini ban revealed that online perpetrators justified their remarks by framing burkinis as symbols of criminal minorities or tools for concealing weapons in terrorist attacks. In doing so, perpetrators portrayed their hate speech as aligned with in-group interests, minimizing the likelihood of social sanctions (Burnap and Williams 2015). As a solution, Chaudhry and Gruzd (2020) suggested that social media platforms should publicly share data on the volume of hateful content removed. This transparency would inform researchers, policymakers, and the public about the scope of hate speech and the effectiveness of moderation efforts (Chaudhry and Gruzd 2020). Vidgen and Yasseri (2020) further advanced this discussion by demonstrating the importance of distinguishing between degrees of hate speech for effective monitoring and intervention. Using a dataset of tweets posted by political parties and far-right accounts from the United Kingdom, Vidgen and Yasseri (2020) developed a machine learning classifier to detect both weak (implicit) and strong (explicit) Islamophobia. Their analysis showed that weak Islamophobia often took the form of subtle exclusion and stereotyping, while strong Islamophobia involved overt slurs, threats, and calls for exclusion. This fine-grained detection, they argue, would equip platforms, policymakers, and civil society actors to better track the normalization of hostility and anticipate when subtle forms of prejudice escalated into more explicit and harmful rhetoric.

At the individual level, counter-speech, which involves directly addressing hateful messages through logical arguments, emotional appeals, or humor, has been highlighted as an effective strategy. While ignoring hateful narratives may reduce their visibility, it risks implying tacit acceptance. Instead, direct confrontation can provide alternative perspectives to those exposed to it, rallying positive sentiments toward the victims (Gerim and Özoflu 2022). Scholars suggest that politely and peacefully confronting racist and sexist content can also act as a social sanctioning mechanism that would shame abusers, encourage them to reevaluate their behavior and discourage further similar posts (Baider 2023). Emphasizing attackers’ superordinate identities, such as religious or national affiliations, can further enhance the effectiveness of counter-speech by “by redefining what it means to be a member of an ingroup and directing ingroup favoritism toward a more inclusive category of people” (Siegel and Badaan 2020, p. 839). When criticism aligns with perpetrators’ social identity, it carries greater normative weight and is more likely to prompt behavior change. One obstacle to counter-speech, as predicted by spiral of silence theory, is that both victims and observers of hate speech may hesitate to respond out of fear of marginalization or a desire to avoid social disapproval. However, this is not always the case, as Chaudhry and Gruzd (2020) found in their analysis of user comments on the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation’s Facebook page, where many individuals actively challenged racist narratives. They suggested that such engagement was driven by a belief in the legitimacy of their stance and a personal concern for the issue of racism.

Online confrontations of hate extend beyond individual reactions to social media posts. The Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement exemplifies how digital activism can amplify marginalized voices and directly challenge racial hierarchies in everyday life (Gürcan and Donduran 2021). Since its inception in 2013, “Black Twitter” has used social media to make “the black body present and newsworthy, thereby undercutting political colorblindness” (Vanaik et al. 2018, p. 839). After the killing of George Floyd in 2020, the BLM online activity peaked as the COVID-19 pandemic’s restrictions increased reliance on social media for social engagement (Cormack and Gulati 2024). Scholars showed that the affordances of social media helped activists to coordinate and synchronize in their reaction to subjugation of Blacks (van Haperen et al. 2023), exposed the White majority to how Blacks experience racial discrimination (Crowder 2023), and allowed White allies to take on cooperative and supportive strategies (Clark 2019). Yet the same visibility that empowered activists also left them vulnerable to backlash. Opponents exploited the #BlackLivesMatter hashtag to intimidate the movement. One interesting case was the hacking of BLM activist DeRay Mckesson’s Twitter account, which was used to post messages aimed at discrediting him and undermining the movement’s credibility (van Haperen et al. 2023). Effective allyship from privileged groups can mitigate some of these challenges, but research suggests that this requires recognition of privilege, a commitment to abandoning racist assumptions, and intentional actions that center the voices and needs of marginalized groups. This approach distinguishes allies from “a friend who may be high on affirmation but not on informed action” or “an activist who may be an informed actor but not necessarily affirming” (Clark 2019, p. 524). Analysis of White allyship in the Black Lives Matter movement demonstrated how White allies’ strategic digital discursive practices not only supported the anti-racist fight in digital spaces but also helped raise awareness among other Whites about individual and structural prejudices (Clark 2019).

There is also a growing literature on how anti -hate messages from influential figures such as celebrities and political or religious leaders carry normative weight and can mobilize broader public support, especially when their identity and social status align with those of the perpetrators (Merrill and Copsey 2022; Munger 2017). Those with greater proficiency in social media and access to professional support tend to respond more assertively, highlighting the critical role of resources, skills, and external assistance in navigating online hostility effectively (Bauschke and Jäckle 2023). Arora et al. (2024) explored how elected officials of color respond to hate speech. Examining Twitter data from 2021, they found that following highly publicized incidents of anti-Asian discrimination, Asian American members of Congress received more online support in terms of likes and retweets when they condemned such discrimination, compared to other Congress members who made similar statements. However, this trend reflects the systemic issue of selective empathy within the broader public sphere. Public interest in issues affecting minoritized communities is often inconsistent, influenced heavily by current media narratives and the visibility of specific events rather than by a deeper and sustained commitment to addressing injustice (Arora et al. 2024).

Drawing on social learning theory, existing work have also drawn attention to the measures that would reduce the impact of exposure to hateful and violent messages on younger adults. The impact of digital technology in the lives of Millennials is particularly important, as research in the United States shows 80 percent of this group reported that they “sleep with a cell phone and their social lives often center in and through media technology platforms and devices” (Maxwell and Schulte 2018, p. 1184). When young individuals are exposed to online extremist worldviews during their socialization process, they perceive these perspectives as reasonable and commonplace (Pauwels and Schils 2016). This also aligns with social identity theory, which claims that when individuals have limited knowledge about outgroup members, they rely on stereotypes, biases, or shared narratives within their in-group to interpret and respond to others (Gonzálvez-Vallés et al. 2023). Social media algorithms exacerbate this issue by creating thinking cocoons that reinforce pre-existing beliefs, as platforms curate content based on users’ previous online behavior (Maxwell and Schulte 2018). To address this, scholars advocate for enhancing digital literacy among the young. Such efforts should focus on helping them critically analyze and recognize instances of racism, sexism, intersectionality and hate speech in online spaces. Additionally, increasing digital literacy must be complemented by education on the socio-historical roots of racism and misogyny to foster a deeper understanding of its systemic and cultural dimensions (Coopilton et al. 2023). This combined approach can equip younger generations with the tools to navigate online environments responsibly and challenge hurtful narratives effectively.

4. Discussion

This paper examined how political science research contributes to our understanding of the proliferation, consequences, and countering of hate speech on social media. While social network sites present a valuable platform for social interaction, self-expression, and identity-building, they have also faced criticism for enabling abusive practices that denigrate individuals or groups based on their religious, ethnic, racial and/or gender identity (Kearns et al. 2022). Much of the existing scholarship on this issue has been led by computer science, communication, and engineering (Ben-David and Matamoros-Fernandez 2016; Matamoros-Fernández 2017; Moore 2018; Zhang et al. 2018; Zhang and Luo 2019), producing literature reviews that systematically categorize the existing studies according to their methodological approaches, thematic areas, years of publication, journal outlets, and author affiliations (Alkomah and Ma 2022; Matamoros-Fernández and Farkas 2021; Paz et al. 2020; Tontodimamma et al. 2021; Unlu and Yilmaz 2022). Political science literature offers an alternative perspective, situating online hate within the broader dynamics of power, understood here as the capacity of dominant actors to control narratives, regulate participation, and reproduce social hierarchies.

Through a systematic narrative literature review, this paper discussed what political science tells us about hate speech on social media and asked three questions: (1) Which factors have been explored in political science as the main drivers of hate speech on social media? (2) What do empirical studies in political science suggest about the political consequences of online hate speech? (3) What strategies have been proposed within the political science literature to address and counteract these dynamics? There is plentiful evidence that social media has enhanced political participation through civic activism, such as online petitions, digital campaigns, and discussion forums (Friess et al. 2021; Gil de Zúñiga et al. 2012, 2014). It enables grassroots movements to take political action at low cost, requiring only a smartphone and minimal technical knowledge. Especially for minority politicians, who may lack the resources to campaign outside social media, it lowers barriers by increasing their visibility through personalized campaigns, online interaction, and information dissemination (Larsson and Moe 2012). However, political science research has also revealed that, at the individual level, exposure to hate speech on social media fosters prejudice, fear, distrust, and isolation and often result in feelings of inefficacy, diminished social trust in society, and decreased political participation (Bauschke and Jäckle 2023; Unlu and Kotonen 2024). Beyond the individual, online hate contributes to international tensions, such as the surge of anti-Asian sentiment during the COVID-19 pandemic, which reinforced global racial hierarchies (Tan 2022). At the structural level, hate speech on social media operates as a gatekeeping mechanism, reinforcing stereotypes, damaging the social desirability of minority politicians, discouraging them from promoting controversial issues, and reducing their interest in pursuing political careers (Pedersen et al. 2024; Petersen et al. 2024; Vrielink and van der Pas 2024). It also creates discursive opportunities for organized hate, increasing its legitimacy and facilitating the recruitment of new members.

This literature review also highlighted that countering online hate demands coordinated efforts at multiple levels. Social media platforms should strengthen moderation by combining automated tools with human oversight, increase transparency by publishing data on removed content, and recognize the importance of addressing not only explicit slurs but also subtler forms of hate that normalize hostility. They also need to engage with local civil society to ensure that harmful content by political leaders is not overlooked in non-Western contexts. Governments should develop clear and enforceable regulatory frameworks that balance freedom of expression with harm prevention. Educators and civil society actors likewise play a crucial role by fostering digital literacy, encouraging counter-speech and allyship, and strengthening resilience among targeted groups.

Despite advancements, there remain critical gaps in the study of online hate speech that future research must address. Much of the existing work has focused on how majority groups target minorities, while comparatively little attention has been paid to how marginalized groups perceive one another, respond to attacks, and engage in solidarity or, in some cases, division (Bhatt et al. 2024). This gap partly stems from the difficulty of identifying users’ ethnic, religious, or gender identities on social media, where personal information is often fabricated, incomplete, or kept private. Despite these challenges, a possible line of research would be on how individuals express their subgroup distinctiveness and resist generalizations. Another avenue for future research is the relationship between fear of isolation and in-group/out-group conflict. Spiral of silence theory suggests that fear of isolation discourages individuals from countering hateful content, while social identity theory argues that perceived out-group threats make hateful discourse appear legitimate to in-group members. Future research could explore whether the silencing effects among majority members are stronger when group identities are more salient.

This review also faced several limitations. First, the search terms applied in WoS were limited to combinations of “hate speech,” “racist,” “sexist,” “racism,” and “sexism” with “social media,” “Twitter”, “YouTube” and “Facebook”. Including keywords such as hostility would enable future studies to examine a broader range of aggressive behaviors that may not be explicitly labeled as hate speech. This could allow for the analysis of microaggressions and antagonistic interactions that fall outside legal or platform definitions of hate speech (Bor and Petersen 2022). Second, the review focused exclusively on English-language articles which may have led to the omission of some relevant studies on the spread of online hate speech in non-English-speaking countries. Third, while the WoS Core Collection provides high-quality sources with consistent academic standards, its coverage relies on editorial criteria and business models that privilege English-language journals, often from countries with longer academic publishing traditions. This can result in an overrepresentation of work from the United States, the United Kingdom, and Western Europe, while regional or non-English contributions remain underrepresented (Mongeon and Paul-Hus 2016). This limitation should be kept in mind when interpreting the findings of this review. Finally, given the time required for conducting the search, writing the manuscript and awaiting the outcome of the peer review process some recently published studies may not have been included.

Funding

This research was funded by the European Union Horizon-Europe Program, in the call HORIZON-CL2-2022-TRANSFORMATION-01-08, in the project “Recognition and Acknowledgement of Injustice to Strengthen Equality” (RAISE), grant agreement 101094684.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Publications on Hate Speech on Social Media in Political Science Research as indexed by the WoS index.

Table A1.

Publications on Hate Speech on Social Media in Political Science Research as indexed by the WoS index.

| Authors | Article Title | Journal | Publication Year | Author Keywords |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anselmi, G; Maneri, M; Quassoli, F | The Macerata shooting: digital movements of opinion in the hybrid media system | Partecipazione E Conflitto | 2022 | Digital Movement; Italy; Racism; Social Media; Terrorism |

| Arora, M; Kim, HJ; Masuoka, N; Stout, CT | How Crises Shape Interest in Elected officials of Color: Social Media Activity, Race and Responsiveness to Members of Congress on Twitter | Political Communication | 2024 | Minority Representatives; Twitter; Asian Americans; Congress; Political Communication |

| Askarzai, B | The Burqa Ban, Islamophobia, and the Effects of Racial Othering in Australian Political Discourses | Australian Journal of Political and Society | 2022 | |

| Baider, F | Accountability Issues, Online Covert Hate Speech, and the Efficacy of Counter-Speech | Politics and Governance | 2023 | Accountability; Argumentative Strategies; Counter -Speech; Covert Hate Speech; Emotional Appeal |

| Baker, SA; Rowe, D | The power of popular publicity: new social media and the affective dynamics of the sport racism scandal | Journal of Political Power | 2013 | Emotions; Media Scandal; Power; Racism Scandal; Social Media |

| Baladrón-Pazos, AJ; Correyero-Ruiz, B; Manchado-Pérez, B | Spanish Political Communication and Hate Speech on Twitter During the Russian Invasion of Ukraine | Politics and Governance | 2023 | Hate Speech; Polarization; Political Communication; Political Parties; Political Social Responsibility; Russia; Spain; Twitter; Ukraine |

| Baspehlivan, U | Theorising the memescape: The spatial politics of Internet memes | Review of International Studies | 2024 | Humour; International Relations Theory; Internet Memes; Social Media; Space; Pop Culture |

| Bauschke, R; Jäeckle, S | Hate speech on social media against German mayors: Extent of the phenomenon, reactions, and implications | Policy and Internet | 2023 | Baden-Wuerttemberg; Communication Culture; Local Politics; Online Violence; Survey |

| Berger, JM; Aryaeinejad, K; Looney, S | There and Back Again How White Nationalist Ephemera Travels Between Online and offline Spaces | Rusi Journal | 2020 | |

| Bhatt, P; Shepherd, ME; McKay, T; Metzl, JM | Racializing COVID-19: Race-Related and Racist Language on Facebook, Pandemic Othering, and Concern About COVID-19 | Political Communication | 2024 | Facebook; Social Media; Racism; COVID-19 |

| Blanco-Herrero, D; Splendore, S; Alonso, MO | Southern European Journalists’ Perceptions of Discursive Menaces in the Age of (Online) Delegitimization | Politics and Governance | 2023 | Discursive Menace; Greece; Hate Speech; Italy; Journalists; Legitimacy of Journalism; Southern Europe; Spain |

| Burnap, P; Williams, ML | Cyber Hate Speech on Twitter: An Application of Machine Classification and Statistical Modeling for Policy and Decision Making | Policy and Internet | 2015 | Twitter; Hate Speech; Internet; Policy; Machine Classification; Statistical Modeling; Cyber Hate; Ensemble Classifier |

| Caldevilla-Domínguez, D; Barrientos-Báez, A; Padilla-Castillo, G | Dilemmas Between Freedom of Speech and Hate Speech: Russophobia on Facebook and Instagram in the Spanish Media | Politics and Governance | 2023 | Deontology; Facebook; Freedom of Speech; Hate Speech; Instagram; Media; Meta; Russia; Russophobia; Social Media |

| Chaudhry, I; Gruzd, A | Expressing and Challenging Racist Discourse on Facebook: How Social Media Weaken the Spiral of Silence Theory | Policy and Internet | 2020 | Racism; Facebook; Social Media; Online Hate; Spiral of Silence |

| Clark, MD | White folks’ work: digital allyship praxis in the #BlackLivesMatter movement | Social Movement Studies | 2019 | Black Lives Matter; Hashtag Activism; Racial Justice; Social Media; Twitter; White Allies |

| Coopilton, M; Tynes, BM; Gibson, SM; Kahne, J; English, D; Nazario, K | Adolescents’ Analyses of Digital Media Related to Race and Racism in the 2020 US Election: An Assessment of Their Needs and Skills | Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science | 2023 | Digital Literacies; Online Civic Reasoning; Critical Race Digital Literacy; 2020 Election; Critical Race Media Literacy; Adolescent Civic Engagement; Computational Propaganda |

| Cormack, L; Gulati, J | Black lives matter messaging across multiple congressional communication mediums | Politics Groups and Identities | 2024 | Black Lives Matter; Political Communication; Race; Movements; Congress |

| Crowder, C | When #BlackLivesMatter at the Women’s March: a study of the emotional influence of racial appeals on Instagram | Politics Groups and Identities | 2023 | Social Media; Racial Appeals; Gender; Emotion; Race |

| Dai, YY; Gao, JJ; Radford, BJ | From fear to hate: Sources of anti-Asian sentiment during COVID-19 | Social Science Quarterly | 2024 | COVID-19; Pandemic; Anti-Asian Racism; Social Media; Health Policy |

| De Gregorio, G; Stremlau, N | Inequalities and content moderation | Global Policy | 2023 | |

| DeCook, JR; Cotter, K; Kanthawala, S; Foyle, K | Safe from harm: The governance of violence by platforms | Policy and Internet | 2022 | Discourse Analysis; Harm; Platform Governance; Platform Policy; Symbolic Violence |

| Dubois, E; Reepschlager, A | How harassment and hate speech policies have changed over time: Comparing Facebook, Twitter and Reddit (2005–2020) | Policy and Internet | 2024 | Content Analysis; Harassment; Hate Speech; Platform Governance; Social Media |

| Duy, IN | The Limits to Free Speech on Social Media: On Two Recent Decisions of the Supreme Court of Norway | Nordic Journal of Human Rights | 2020 | Hate Speech; Freedom of Speech; Social Media |

| Einwiller, SA; Kim, S | How Online Content Providers Moderate User-Generated Content to Prevent Harmful Online Communication: An Analysis of Policies and Their Implementation | Policy and Internet | 2020 | Content Filtering; Content Moderation; Harmful Online Communication; Online Abuse; Online Content Providers |

| Enli, G | Populism as Truth: How Mediated Authenticity Strengthens the Populist Message | International Journal of Press-Politics | 2025 | Authenticity; Mediated Authenticity; Politics; Performance; Populism; Trump |

| Fangen, K | Gendered Images of us and Them in Anti-Islamic Facebook Groups | Politics Religion & Ideology | 2020 | |

| Fiers, R; Muis, J | Dividing between ‘us’ and ‘them’: the framing of gender and sexuality by online followers of the Dutch populist radical right | European Journal of Politics and Gender | 2021 | Populist Radical Right; The Netherlands; Gender; Sexuality; Social Media; Facebook |

| Galpin, C | At the Digital Margins? A Theoretical Examination of Social Media Engagement Using Intersectional Feminism | Politics and Governance | 2022 | Brexit; Digital Activism; European Public Sphere; Feminism; Intersectionality; Online Harassment; Online Violence; Populist Radical Right; Social Media; Transphobia |

| Galpin, C; Vernon, P | Post-truth politics as discursive violence: Online abuse, the public sphere and the figure of ‘the expert’ | British Journal of Politics & International Relations | 2024 | Epistemological Populism; Gender; Harassment; Hate Speech; Hybrid Media System; Intersectionality; Online Abuse; Post-Truth; Public Sphere; Queer Theory; Sexuality; Social Media |

| Gerim, G; Özoflu, MA | Let the man know his place!: Challenging the Patriarchy Embedded in Social Language via Twitter | Romanian Journal of Political Science | 2022 | Women’s Movement in Turkey; Linguistic Sexism; Twitter Feminism; Gendered Discourse; Critical Discourse Analysis |

| Gonzálvez-Vallés, JE; Barquero-Cabrero, JD; Enseñat-Bibiloni, N | Voter’s Perception of Political Messages Against the Elite Classes in Spain: A Quasi-Experimental Design | Politics and Governance | 2023 | Demonization; Elite Classes; Hate Speech; Polarization; Political Discourse; Social Networks |

| Gürcan, EC; Donduran, C | The Formation and Development of the Black Lives Matter Movement: A Political Process Perspective | Siyasal-Journal of Political Science | 2021 | American Politics; Black Lives Matter; Civil Rights; Political Process; Racism; Social Movements |

| Hobbs, W; Lajevardi, N; Li, XY; Lucas, C | From Anti-Muslim to Anti-Jewish: Target Substitution on Fringe Social Media Platforms and the Persistence of Online and offline Hate | Political Behavior | 2024 | |

| Ibrahim, AM | Theorizing the Journalism Model of Disinformation and Hate Speech Propagation in a Nigerian Democratic Context | International Journal of E-Politics | 2019 | Alternative Facts; Disinformation; Dislike; Fake News; Hate Speech; Information Disorder; Nigerian Democracy; Nigerian Journalism; Nigerian News Media; Political Campaign; Post-Democracy |

| Irving, E | Suppressing Atrocity Speech on Social Media | Ajil Unbound | 2019 | |

| Kim, HY | What’s wrong with relying on targeted advertising? Targeting the business model of social media platforms | Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy | 2024 | Moral Complicity; Business Models; Targeted Advertising; Dominant Platforms; Taxation |

| Konikoff, D | Gatekeepers of toxicity: Reconceptualizing Twitter’s abuse and hate speech policies | Policy and Internet | 2021 | Content Moderation; Deterrence Theory; Gatekeeping Theory; Hate Speech; Responsibilization; Twitter |

| Lilleker, D; Pérez-Escolar, M | Demonising Migrants in Contexts of Extremism: Analysis of Hate Speech in UK and Spain | Politics and Governance | 2023 | Extremism; Far -Right Parties; Hate Speech; Immigration; Social Media; Spain; UK |

| Marcks, H; Pawelz, J | From Myths of Victimhood to Fantasies of Violence: How Far-Right Narratives of Imperilment Work | Terrorism and Political Violence | 2022 | Far Right; Radicalization; Political Violence; Social Media; Narratives; Hate Speech; Dangerous Speech |

| Maxwell, A; Schulte, SR | Racial Resentment Attitudes Among White Millennial Youth: The Influence of Parents and Media | Social Science Quarterly | 2018 | |

| Mchangama, J; Alkiviadou, N | Hate Speech and the European Court of Human Rights: Whatever Happened to the Right to offend, Shock or Disturb? | Human Rights Law Review | 2021 | Freedom of Expression; Hate Speech; Social Media; European Court of Human Rights |

| Meriläinen, JM | The Role of Gender in Hate Speech Targeting Politicians: Evidence from Finnish Twitter | International Journal of Politics Culture and Society | 2024 | Hate Speech; Cyberbullying; E-Democracy; Online Communication; Twitter |

| Merrill, S; Copsey, N | Retweet solidarity: transatlantic Twitter connectivity between militant antifascists in the USA and UK | Social Movement Studies | 2022 | Mediated Solidarity; Antifa; Digital Antifascism; Transnationalism; Translocality; Social Media |

| Meza, R; Vincze, HO; Mogos, A | Targets of Online Hate Speech in Context. A Comparative Digital Social Science Analysis of Comments on Public Facebook Pages from Romania and Hungary | Intersections-East European Journal of Society and Politics | 2018 | Social Media; Hate Speech; Romania; Hungary; Digital Social Science; Text Mining |

| Mlacnik, P; Stankovic, P | The Disappearance of Political Jokes in Post-Socialist Slovenia | Communist and Post-Communist Studies | 2020 | Political Jokes; Slovenia; Post-Socialism; Politicians |

| Moreno-Almeida, C; Gerbaudo, P | Memes and the Moroccan Far-Right | International Journal of Press-Politics | 2021 | Misogyny; Racism; Arab Right; Middle East and North Africa; Pepe the Frog; Yes Chad Meme; Dank Memes; Marinid Flag; Make America Great Again |

| Munger, K | Tweetment Effects on the Tweeted: Experimentally Reducing Racist Harassment | Political Behavior | 2017 | Online Harassment; Social Media; Randomized Field Experiment; Social Identity |

| Ndahinda, FM; Mugabe, AS | Streaming Hate: Exploring the Harm of Anti-Banyamulenge and Anti-Tutsi Hate Speech on Congolese Social Media | Journal of Genocide Research | 2024 | Hate Speech; Conspiracy Theories; Social Media; Banyamulenge; Tutsi; Drc Conflict; Violence |

| Pauwels, L; Schils, N | Differential Online Exposure to Extremist Content and Political Violence: Testing the Relative Strength of Social Learning and Competing Perspectives | Terrorism and Political Violence | 2016 | Belgium; Differential Association; Exposure; New Social Media; Political Violence; Social Learning; Youth Delinquency |

| Pedersen, RT; Petersen, NBG; Thau, M | Online Abuse of Politicians: Experimental Evidence on Politicians’ Own Perceptions | Political Behavior | 2024 | Social Media; Online Abuse; Politicians; Sexual Harassment; Gender; Partisanship; In-Group Favoritism; Ideology; Political Trust; Measurement; Experiment |

| Petersen, NBG; Pedersen, RT; Thau, M | Citizens’ perceptions of online abuse directed at politicians: Evidence from a survey experiment | European Journal of Political Research | 2024 | Online Abuse; Citizens’ Perceptions; Partisanship; Political Ideology and Trust; Gender |

| Pettersson, K; Martikainen, J; Hakoköngäs, E; Sakki, I | Female Politicians as Climate Fools: Intertextual and Multimodal Constructions of Misogyny Disguised as Humor in Political Communication | Political Psychology | 2023 | Multimodality; Critical Discursive Psychology; Misogyny; Political Mobilization; Finns Party; YouTube |

| Radics, G; Abidin, C | Racial harmony and sexual violence: Uneven regulation and legal protection gaps for influencers in Singapore | Policy and Internet | 2022 | Gender; Influencers; Law; Race; Sexuality; Singapore; Social Media |

| Said-Hung, E; Moreno-López, R; Mottareale-Calvanese, D | Promotion of hate speech by Spanish political actors on Twitter | Policy and Internet | 2023 | Hate Speech; Political Communication; Political Groups; Social Media; Twitter |

| Sánchez-Holgado, P; Arcila-Calderón, C; Gomes-Barbosa, M | Hate Speech and Polarization Around the Trans Law in Spain | Politics and Governance | 2023 | Hate Speech; Lgtbi; Polarization; Public Perception; Spain; Trans Law; Transphobia; Twitter |

| Sawer, M | Misogyny and misrepresentation: Women in Australian parliaments | Political Science | 2013 | Gender Politics; Misogyny; Representation; Women Political Leaders; Women’s Policy |

| Schissler, M | Beyond Hate Speech and Misinformation: Facebook and the Rohingya Genocide in Myanmar | Journal of Genocide Research | 2024 | Hate Speech; Misinformation; Facebook; Rohingya Genocide; Myanmar |

| Schlag, G | European Union’s Regulating of Social Media: A Discourse Analysis of the Digital Services Act | Politics and Governance | 2023 | Content Moderation; Digital Services Act; EU Regulation; Freedom of Expression; Social Media Platforms |

| Serrao, R | Racializing Region: Internal Orientalism, Social Media, and the Perpetuation of Stereotypes and Prejudice against BrazilianNordestinos | Latin American Perspectives | 2022 | Social Media; Racism; Bolsonaro; Partido Dos Trabalhadores; Northeast; Nordestinos |

| Siegel, AA; Badaan, V | #No2Sectarianism: Experimental Approaches to Reducing Sectarian Hate Speech Online | American Political Science Review | 2020 | |

| Soral, W; Liu, JH; Bilewicz, M | Media of Contempt: Social Media Consumption Predicts Normative Acceptance of Anti-Muslim Hate Speech and Islamoprejudice | International Journal of Conflict and Violence | 2020 | Hate Speech; Social Media; Islamophobia; Social Norms |

| Tan, RC | Social Media Platforms Duty of Care-Regulating Online Hate Speech | Australasian Parliamentary Review | 2022 | |

| Tembo, NM | Women, political violence, and the production of fear in Malawian social media texts | International Feminist Journal of Politics | 2024 | Political Violence; Fear; Malawi; Sexism; Social Media |

| Trauthig, IK | This is the fate of Libyan women:‘ contempt, ridicule, and indifference of Seham Sergiwa | Conflict Security & Development | 2024 | Libya; Social Media; Hate Speech; Gender-Based Violence; Middle East; Social Movements; Public Sphere |

| Unlu, A; Kotonen, T | Online polarization and identity politics: An analysis of Facebook discourse on Muslim and LGBTQ plus communities in Finland | Scandinavian Political Studies | 2024 | LGBTQ Plus; Muslim; Political Polarization; Social Identity Theory; Social Media |

| Unlu, A; Yilmaz, K | Online Terrorism Studies: Analysis of the Literature | Studies In Conflict & Terrorism | 2022 | |

| van Haperen, S; Uitermark, J; Nicholls, W | The Swarm versus the Grassroots: places and networks of supporters and opponents of Black Lives Matter on Twitter | Social Movement Studies | 2023 | Black Lives Matter; Grassroots; Networks; Social Media; Social Movements; Swarm |

| Vanaik, A; Jengelley, D; Peterson, R | Reframing racism: political cartoons in the era of Black Lives Matter | Politics Groups and Identities | 2018 | |

| Vera, SV | Rage in the Machine: Activation of Racist Content in Social Media | Latin American Politics and Society | 2023 | Racism; Social Media; Indigena Protest; Machine Learning; Ecuador |

| Vidgen, B; Yasseri, T | Detecting weak and strong Islamophobic hate speech on social media | Journal of Information Technology & Politics | 2020 | Hate Speech; Islamophobia; Prejudice; Social Media; Natural Language Processing; Machine Learning |

| Vrielink, J; van der Pas, DJ | Part of the Job? The Effect of Exposure to the Online Intimidation of Politicians on Political Ambition | Political Studies Review | 2024 | Political Ambition; Gender; Online Intimidation; Social Media; Violence Against Women in Politics |

| Wahlström, M; Törnberg, A | Social Media Mechanisms for Right-Wing Political Violence in the 21st Century: Discursive Opportunities, Group Dynamics, and Co-Ordination | Terrorism and Political Violence | 2021 | Discursive Opportunities; Interaction Ritual; Political Violence; Radical Right; Social Media |

| Wang, X; Zhang, Y; Wang, SG; Zhao, K | MIGRANT INFLOWS AND ONLINE EXPRESSIONS of REGIONAL PREJUDICE IN CHINA | Public Opinion Quarterly | 2021 | |

| Williams, TJV; Tzani, C; Gavin, H; Ioannou, M | Policy vs reality: comparing the policies of social media sites and users’ experiences, in the context of exposure to extremist content | Behavioral Sciences of Terrorism and Political Aggression | 2023 | Extremism; Online; Social Media |

| Wilson, RA | The Anti-Human Rights Machine: Digital Authoritarianism and The Global Assault on Human Rights | Human Rights Quarterly | 2022 | |

| Yildirim, MM; Nagler, J; Bonneau, R; Tucker, JA | Short of Suspension: How Suspension Warnings Can Reduce Hate Speech on Twitter | Perspectives on Politics | 2023 | |

| Zhang, CC | Right-wing populism with Chinese characteristics? Identity, otherness and global imaginaries in debating world politics online | European Journal of International Relations | 2020 | China; Chinese Identity; Discourse Analysis; Liberal World Order; Right-Wing Populism |

References

- Alkomah, Fatimah, and Xiaogang Ma. 2022. A literature review of textual hate speech detection methods and datasets. Information 13: 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anselmi, Guido, Marcello Maneri, and Fabio Quassoli. 2022. The Macerata shooting: Digital movements of opinion in the hybrid media system. Partecipazione e Conflitto 15: 846–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, Maneesh, Hannah June Kim, Natalie Masuoka, and Christopher T. Stout. 2024. How crises shape interest in elected officials of color: Social media activity, race and responsiveness to Members of Congress on Twitter. Political Communication 42: 268–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askarzai, Benafsha. 2022. The burqa ban, Islamophobia, and the effects of racial ‘othering’ in Australian political discourses. Australian Journal of Politics and History 68: 218–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baider, Fabienne. 2023. Accountability issues, online covert hate speech, and the efficacy of counter-speech. Politics and Governance 11: 249–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, Stephanie Alice, and David Rowe. 2013. The power of popular publicity: New social media and the affective dynamics of the sport racism scandal. Journal of Political Power 6: 441–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baladrón-Pazos, Antonio José, Beatriz Correyero-Ruiz, and Benjamín Manchado-Pérez. 2023. Spanish political communication and hate speech on Twitter during the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Politics and Governance 11: 160–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Başpehlivan, Uygar. 2024. Theorising the memescape: The spatial politics of internet memes. Review of International Studies 50: 35–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, Roy F., and Mark R. Leary. 1997. Writing narrative literature reviews. Review of General Psychology 1: 311–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauschke, Rafael, and Sebastian Jäckle. 2023. Hate speech on social media against German mayors: Extent of the phenomenon, reactions, and implications. Policy and Internet 15: 223–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-David, Anat, and Ariadna Matamoros-Fernandez. 2016. Hate speech and covert discrimination on social media: Monitoring the Facebook pages of extreme-right political parties in Spain. International Journal of Communication 10: 1167–93. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, J M, Kateira Aryaeinejad, and Seán Looney. 2020. There and back again how White nationalist ephemera travels between online and offline spaces. Rusi Journal 165: 114–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, Priya, Michael E. Shepherd, Tara McKay, and Jonathan M. Metzl. 2024. Racializing COVID-19: Race-related and racist language on Facebook, pandemic othering, and concern about COVID-19. Political Communication 42: 286–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Herrero, David, Sergio Splendore, and Martín Oller Alonso. 2023. Southern European journalists’ perceptions of discursive menaces in the age of (online) delegitimization. Politics and Governance 11: 210–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]