Women’s Wise Walkshops: A Participatory Feminist Approach to Urban Co-Design in Ferrara, Italy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Feminist Epistemologies, Urban Studies and Spatial Analysis

2.2. Urban Traversals as an Instrument of Participatory Planning and Community Engagement

2.3. Walkability and Urban Quality of Life

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design and Theoretical Framework

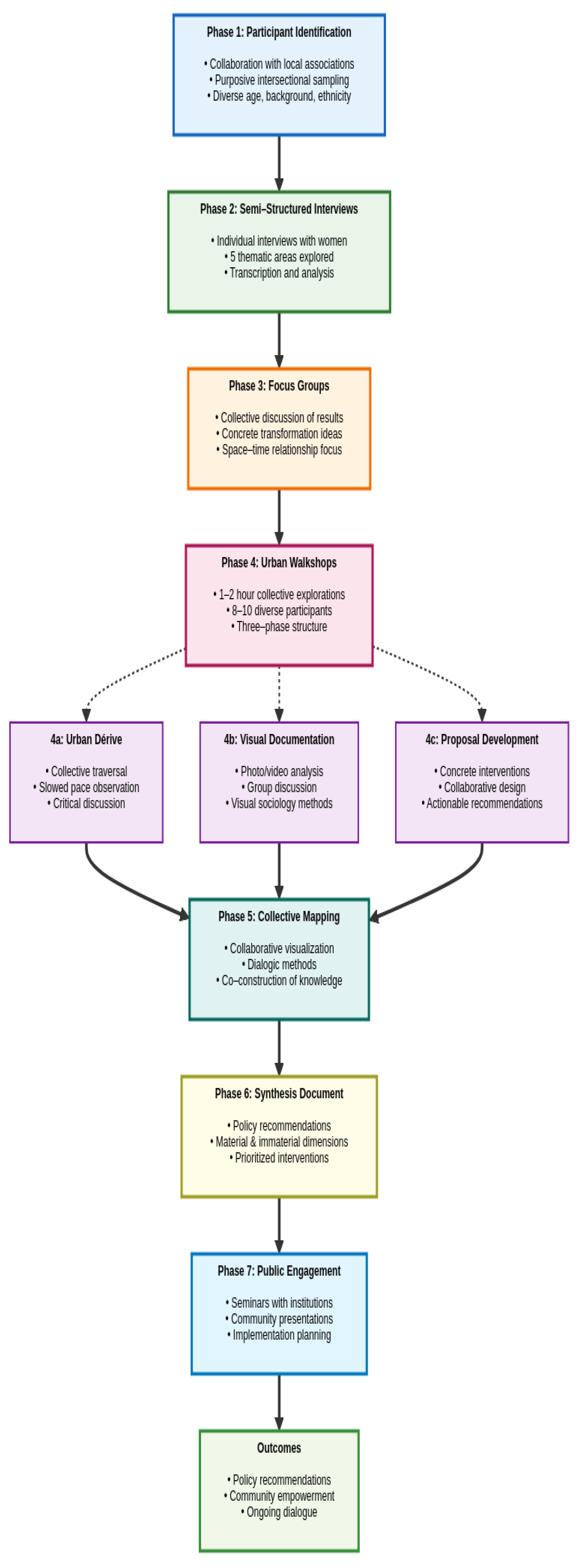

3.2. The Women’s Wise Walkshops (WWW) Framework1

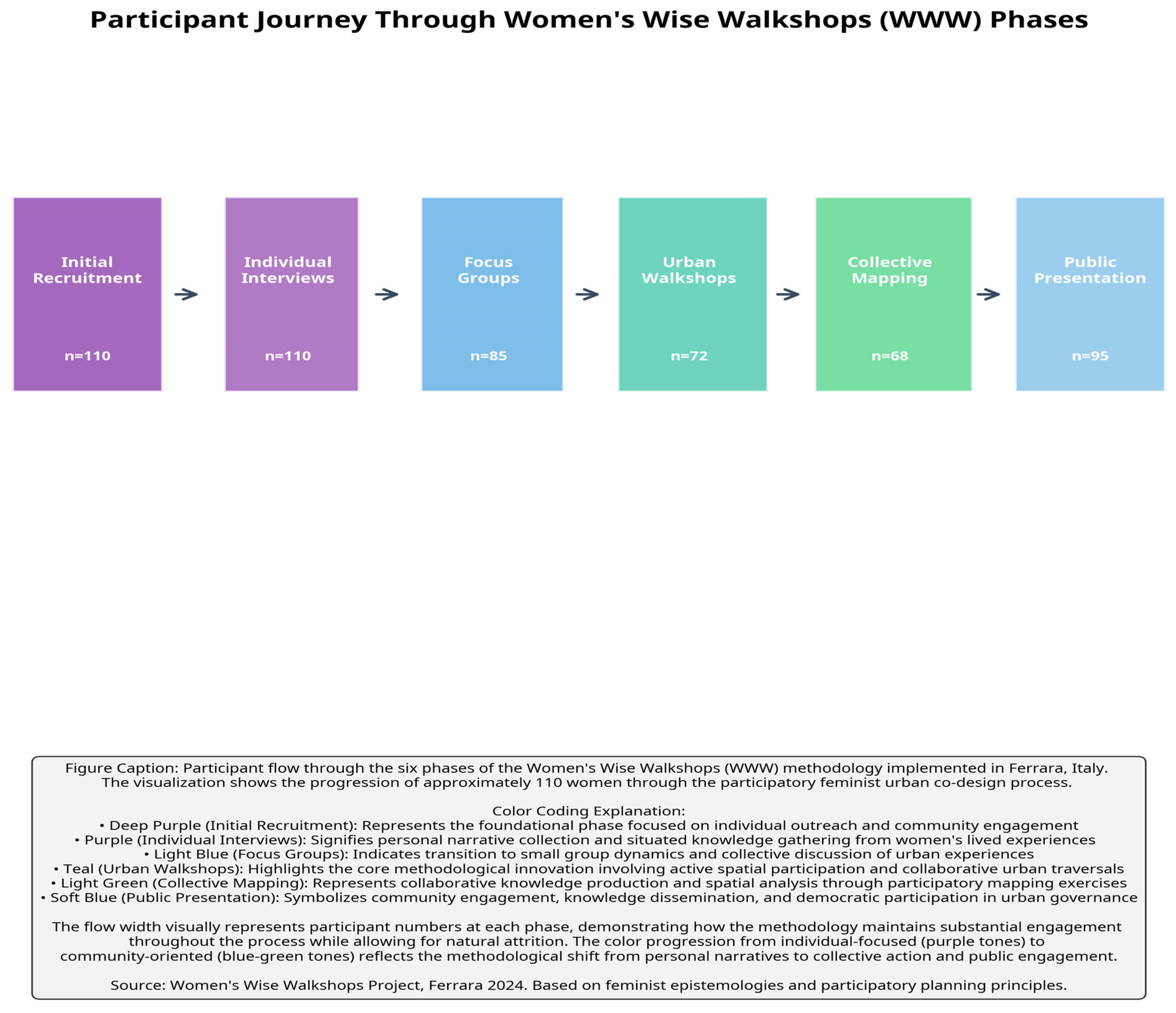

- Phase 1: Participant Identification and Recruitment

- Phase 2: Semi-Structured Interviews

- Presence and usage patterns: Frequency of use and motivations for using public urban spaces.

- Social gathering spaces: Characteristics and quality of spaces for community interaction.

- Mobility systems: Features and quality of transportation and pedestrian infrastructure.

- Urban infrastructure quality: Perceived quality of neighborhood and city spaces in terms of material and immaterial infrastructure.

- Enhancement opportunities: Identification of elements that could improve urban livability.

- Phase 3: Focus Groups

- Phase 4: Urban Walkshops

- Phase 5: Collective Thematic Mapping

- Phase 6: Synthesis and Policy Recommendations

- Phase 7: Public Engagement and Dissemination

3.3. Case Study Context: Ferrara, Italy

3.4. Data Collection and Analysis

3.5. Ethical Considerations and Limitations

4. Qualitative Results

4.1. Overview of Findings

4.2. Primary Themes from Interview Analysis

4.2.1. Physical Activity and Health Infrastructure

4.2.2. Security and Safety Concerns

4.2.3. Cultural Decentralization and Access

4.2.4. Infrastructure Quality and Maintenance

4.2.5. Social Gathering Spaces and Community Building

4.2.6. Participatory Processes and Democratic Engagement

4.2.7. Mobility Systems and Transportation Equity

4.2.8. Urban Beauty and Environmental Quality

4.3. Visualand Spatial Analysis

4.3.1. Spaces of Sociability

4.3.2. Local Commerce and Economic Vitality

4.3.3. Urban Insecurity and Infrastructure Deficits

4.4. Thematic Analysis and Synthesis

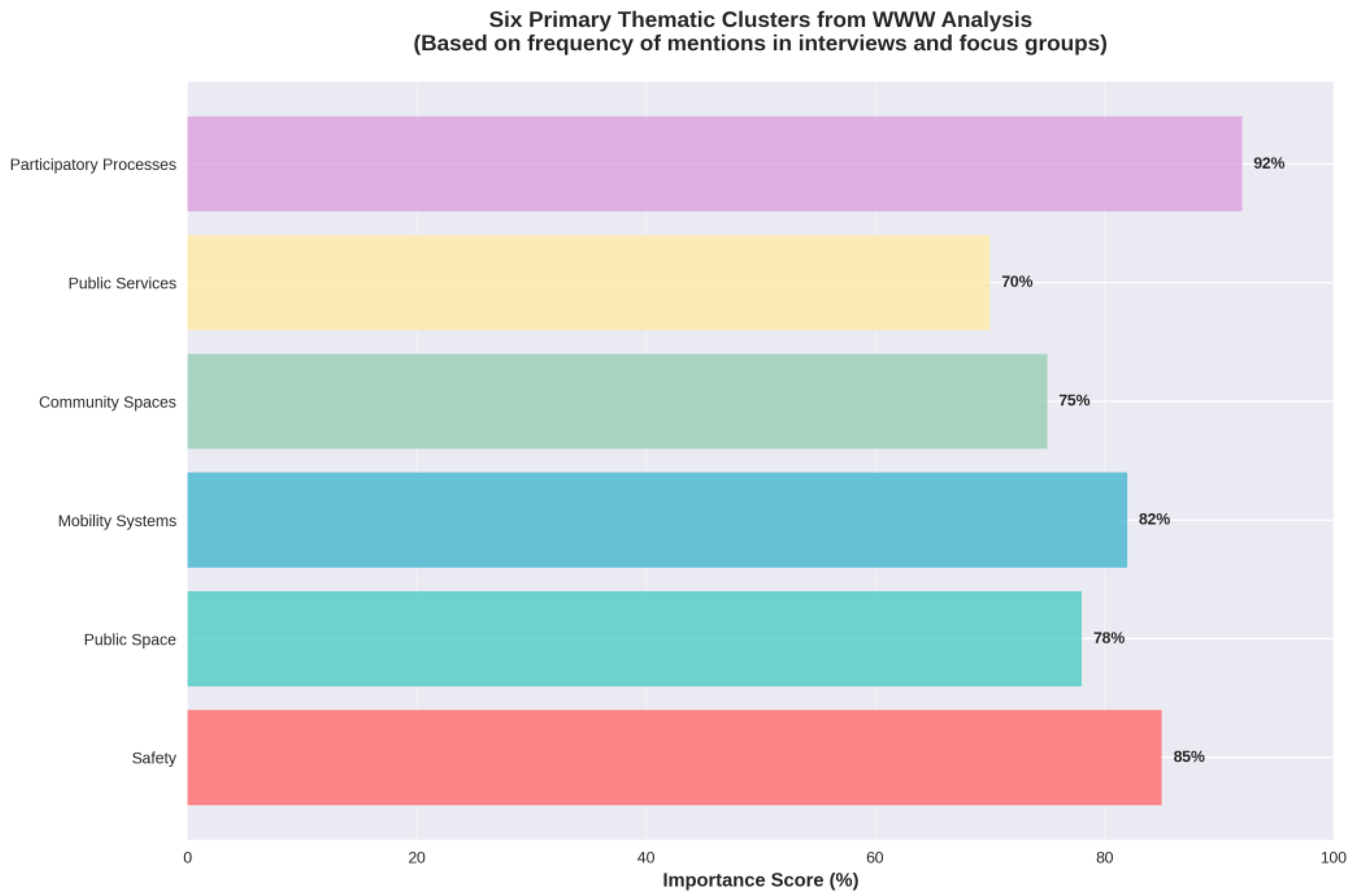

4.4.1. Six Primary Thematic Clusters

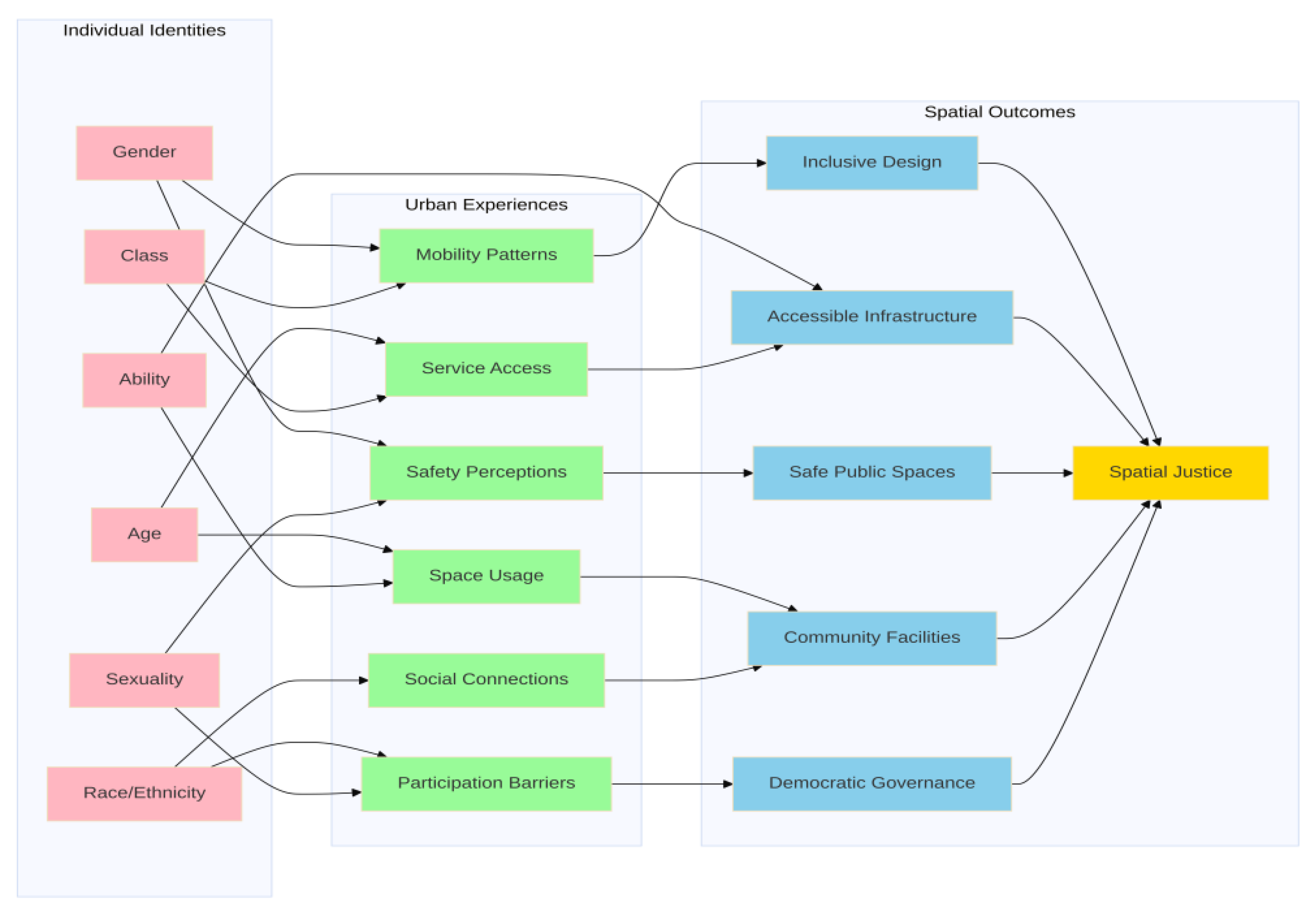

4.4.2. Interconnections and Systemic Relationships

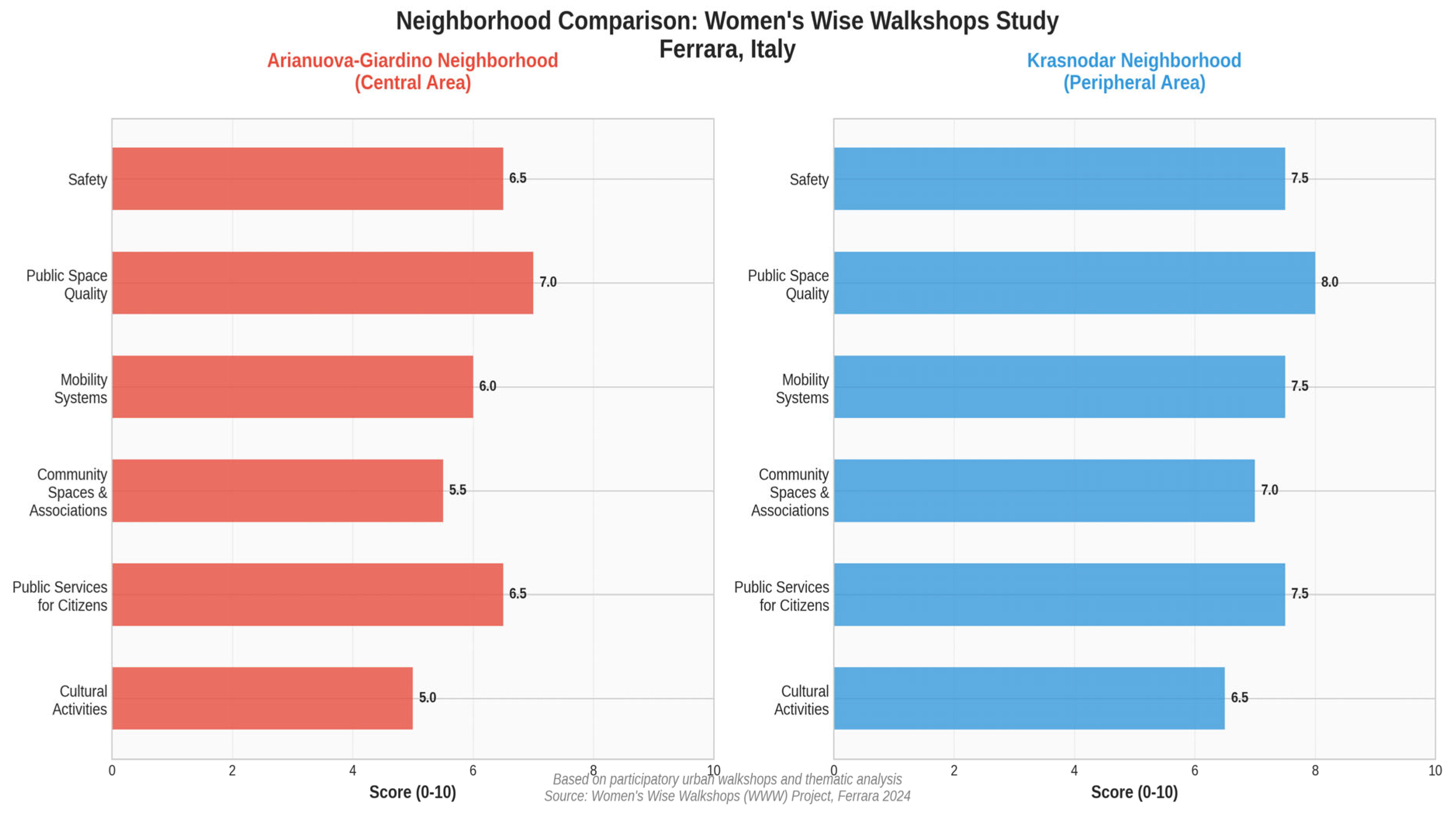

4.5. Comparative Analysis Across Neighborhoods

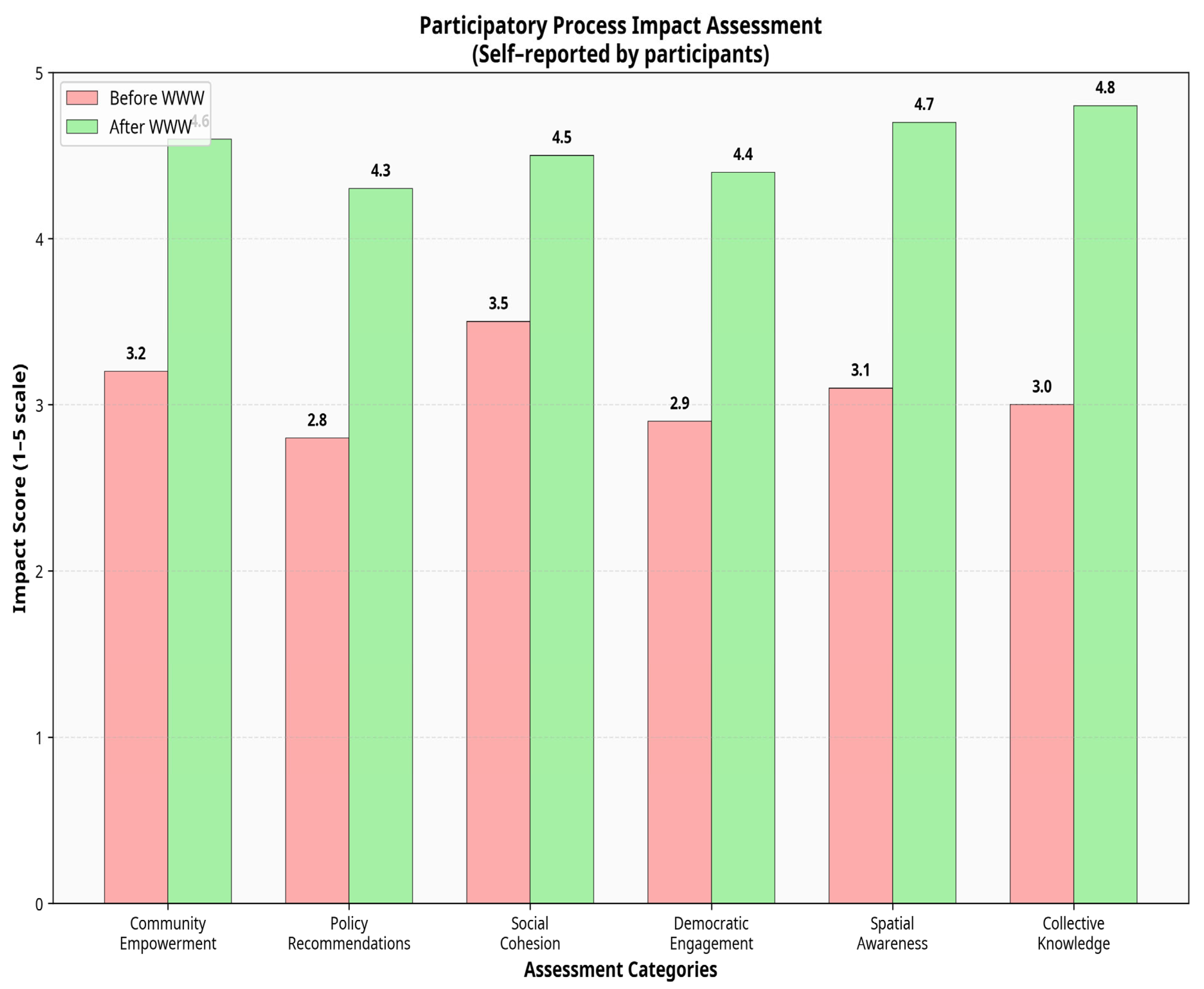

4.6. Participant Empowerment and Knowledge Production

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contributions to Feminist Urban Studies

5.2. Methodological Innovations and Participatory Practice

5.3. Spatial Justice and Urban Rights

5.4. Intersectionality and Urban Experience

5.5. Community Empowerment and Democratic Engagement

5.6. Implications for Urban Planning Practice

5.7. Challenges and Limitations

5.8. Broader Implications for Urban Governance

5.9. Contributions to Medium-Sized City Studies

6. Conclusions

Summary of Key Findings

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviation

| WWW | Women’s Wise Walkshops |

| 1 | The walkshop WWW was conducted within the framework of the national project Age It. Ageing well in an ageind society. Initially aimed exclusively at older women, it was later broadened to include women in general, adopting an intersectional inclusion approach that transcended the age variable. |

References

- Arnstein, Sherry R. 1969. A Ladder of Citizen Participation. Journal of the American Planning Association 85: 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, Zygmunt. 2000. Liquid Modernity. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Beebeejaun, Yasminah. 2017. Gender, Urban Space, and the Right to Everyday Life. Journal of Urban Affairs 39: 323–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, Walter. 1999. The Arcades Project. Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Blidon, Marianne. 2019. Still a Long Way to Go: Gender and Feminist Geographies in France. Gender 26: 1039–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, Judith. 1990. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, Judith. 2007. Cram101 Textbook Outlines to Accompany: Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity, by Judith Butler. Cambridge: Academic Internet Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Carrera, Letizia. 2011. Donne e lavoro. Mondo dei lavori e mondi della vita. Bari: Palomar. [Google Scholar]

- Carrera, Letizia. 2022a. Designing Inclusive Urban Places. ItalianSociological Review 12: 141–58. [Google Scholar]

- Carrera, Letizia. 2022b. La flâneuse. Lo sguardo obliquo nella città. Fuori Luogo 10: 15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Carrera, Letizia. 2022c. La flâneuse. Sguardi ed esperienze al femminile. Milano: Franco Angeli. [Google Scholar]

- Carrera, Letizia. 2022d. (Ri)educate to PoliticalParticipation: The Democratic Challenge. Athens Journal of Social Sciences 9: 161–72. [Google Scholar]

- Carrera, Letizia. 2024. Lo sguardo delle donne per immaginare e progettare una città différence friendly. In Sguardi diversi. Riflessioni, analisi, immagini, pratiche. Edited by Letizia Carrera. Bari: Progedit, pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Carrera, Letizia. 2025. Gender walkshops: The potential of the female gaze in (re)design the city. International Journal of Gender Studies in Developing Societies 5: 124–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrera, Letizia, and Marina Castellaneta. 2023. Women and Cities. The Conquest of Urban Space. Frontiers in Sociology 8: 1125439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collie, Natalie. 2011. Cities of the Imagination: Science Fiction, Urban Space, and Community Engagement in Urban Planning. Futures 43: 424–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, Patricia Hill. 2000. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment, 2nd ed. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw, Kimberlé. 1989. Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum 1989: 8. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw, Kimberlé. 1991. Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color. Stanford Law Review 43: 1241–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Beauvoir, Simone. 1963. Nature of the Second Sex. London: The New English Library. [Google Scholar]

- Debord, Guy. 1958. Theory of the derive. InternationaleSituationniste 2: 62–66. [Google Scholar]

- De Carlo, Giancarlo. 2015. Architecture’s Public. Edited by Peter Blundell Jones, Doina Petrescu and Jeremy Till. Architecture and Participation. London: SponPress, pp. 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- de Certeau, Michel. 1980. L’invention du Quotidien. Paris: Gallimard. [Google Scholar]

- Dovey, Kim, and Elek Pafka. 2020. What Is Walkability? The Urban DMA. Urban Studies 57: 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkin, Lauren. 2017. Flâneuse: Women Walk the City in Paris, New York, Tokyo, Venice, and London. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. [Google Scholar]

- Ewing, Reid, and Susan Handy. 2009. Measuring the Unmeasurable: Urban Design Qualities Related to Walkability. Journal of Urban Design 14: 65–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falú, Ana. 2007. Women in the City: On Violence and Rights. Santiago: Ediciones SUR. [Google Scholar]

- Fenster, Tovi. 2005. The Right to the Gendered City: Different Formations of Belonging in Everyday Life. Journal of Gender Studies 14: 217–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garfinkel, Harold. 1967. Studies in Ethnomethodology. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gearin, Elizabeth, and Carletta S. Hurt. 2024. Making Space: A New Way for Community Engagement in the Urban Planning Process. Sustainability 16: 2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffman, Donald. 2017. RELATIONS in PUBLIC: Microstudies of the Public Order. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Grosz, Elizabeth. 1994. Volatile Bodies Toward a Corporeal Feminism. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Haraway, Donna. 1988. Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective. Feminist Studies 14: 575–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, Sandra G. 1991. Whose Science? Whose Knowledge?: Thinking from Women’s Lives. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Healey, Patsy. 2006. Collaborative Planning: Shaping Places in Fragmented Societies. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Hooks, Bell. 1984. Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center. New York and London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hooks, Bell. 1999. All about Love: New Visions. New York: Harper Perennial. [Google Scholar]

- Hooks, Bell. 2004. The Will to Change: Men, Masculinity, and Love. New York: Washington Square Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, Jane M. 1961. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: The Modern Library. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Jiayi, Nadia Bertolino, and Kexin Huang. 2023. Gender Walks in the City: An Exploratory Study on Gender-Responsive Urban Planning. In Urban Redevelopment and Revitalisation. A Multidisciplinary Perspective. Paper presented at ISUF 2022, Łódź and Kraków, Poland, June 6–September 11. Lodz: Lodz University of Technology Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, Leslie. 2020. FEMINIST CITY: Claiming Space in a Man-Made World. London: Verso Books. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, Henri. 1967. The Right to the City. In Writings on Cities. Oxford: Blackwell, pp. 147–59. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, Henri. 1991. The Production of Space. Translated by Donald Nicholson-Smith. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Magnaghi, Alberto. 2000. Il progetto locale. Turin: Bollati Boringhieri. [Google Scholar]

- Massey, Doreen. 1994. Space, Place, and Gender. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, C. Wright. 1959. The Sociological Imagination. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mulvey, Laura. 1999. Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema. In Film Theory and Criticism: Introductory Readings. New York: Oxford UP. [Google Scholar]

- Nesci, Catherine. 2007. Le flâneur et les flâneuses: Les femmes et la ville à l’époque romantique. Grenoble: Ellug. [Google Scholar]

- Nuvolati, Giampaolo. 2006. Lo sguardo vagabondo: Il flâneur e la città da Baudelaire ai postmoderni. Bologna: Il Mulino. [Google Scholar]

- Nuvolati, Giampaolo. 2008. Resident and non-resident populations: Quality of life, mobility and time policies. Journal of Regional Analysis and Policy 38: 105–18. [Google Scholar]

- Nuvolati, Giampaolo. 2009. L’interpretazione dei luoghi: Flânerie come esperienza di vita. Florence: Firenze University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nuvolati, Giampaolo. 2013. Il flâneur nella città contemporanea. Bologna: Il Mulino. [Google Scholar]

- Nuvolati, Giampaolo. 2020. Urban Flânerie and the Cognitive Mapping of Cities. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Proudfoot, Jesse. 2019. The Stakes of Situated Knowledges. Dialogues in Human Geography 9: 158–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadler, Simon. 1999. The Situationist City. Cambridge: The Mit Press. [Google Scholar]

- Secchi, Bernardo. 2010. La città del ventesimo secolo. Rome: Laterza. [Google Scholar]

- Secchi, Bernardo. 2013. La città dei ricchi e la città dei poveri. Rome: Laterza. [Google Scholar]

- Spain, Daphne. 2000. Gendered Spaces. Chapell Hill: University of North Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zibell, Barbara, Doris Damyanovic, and Ulrike Sturm. 2019. Gendered Approaches to Spatial Development in Europe. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Zukin, Sharon. 1995. The Cultures of Cities. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Carrera, L. Women’s Wise Walkshops: A Participatory Feminist Approach to Urban Co-Design in Ferrara, Italy. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 609. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14100609

Carrera L. Women’s Wise Walkshops: A Participatory Feminist Approach to Urban Co-Design in Ferrara, Italy. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(10):609. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14100609

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarrera, Letizia. 2025. "Women’s Wise Walkshops: A Participatory Feminist Approach to Urban Co-Design in Ferrara, Italy" Social Sciences 14, no. 10: 609. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14100609

APA StyleCarrera, L. (2025). Women’s Wise Walkshops: A Participatory Feminist Approach to Urban Co-Design in Ferrara, Italy. Social Sciences, 14(10), 609. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14100609