Abstract

Two areas that have scientifically erupted in the last two decades are the sciences of meaning and of character strengths, yet the integration of these areas has been minimal. Some studies have drawn significant connections between character strengths and meaning in life; however, the samples have been limited, the measures have not measured or separated the types of meaning, and/or the studies have not gathered data from participants on the nuances of meaning. We conducted a large-scale, mixed methods study with 23,641 participants, spanning more than 100 countries. We measured the 24 character strengths using the VIA Inventory of Strengths and the three components of meaning—coherence/comprehension, significance/mattering, and purpose—using the Multidimensional Existential Meaning Scale. Participants shared their observations on how their chosen character strength was helpful for coherence, purpose, and significance. Meaning scales were significantly correlated with all character strengths. The strongest predictors of overall meaning were hope, spirituality, zest, curiosity, and gratitude. We found gender differences for character strengths and types of meaning, as well as age trends. Finally, we qualitatively analyzed the answers explaining the selections of character strengths, and assessed differences between gender and age. We discuss the findings within this intersection as well as ramifications for the scientific synergy of character strengths and meaning.

1. Introduction

The ancient philosopher Aristotle (Aristotle 2001) coined the concept of “eudaimonia” to refer to human flourishing as achieved through the development of one’s full potential and the cultivation of virtue. This concept complements hedonic well-being, which is centered around pleasure-seeking. Over time, various conceptual definitions and operationalizations emerged to describe the psychological experience of eudaimonic well-being. One such definition explicitly integrates individuals’ sense of meaning and purpose in life and the cultivation of their virtues and character strengths: “Eudaimonia, as a subjective state, refers to the feelings present when one is moving toward self-realization in terms of developing one’s unique individual potentials and furthering one’s purposes in living” (Waterman et al. 2008, p. 42). In line with Aristotle’s view, the highest human good involves activities that are purposeful and are goal-directed (Ryff and Singer 2008).

However, although the connection between character strengths and meaning in life seem natural and synergistic, and while these two areas in the science of well-being have erupted in the last two decades, the scientific integration of these areas has been minimal.

2. Meaning in Life: A Tripartite View

Throughout history and across cultures, individuals from various backgrounds, including philosophers, religious scholars, social scientists, and ordinary people, have grappled with the question of meaning in life. Experiencing life as meaningful is considered a fundamental human need (Baumeister 1991; Frankl 1963). In recent decades, there has been a substantial increase in empirical research that affirms the critical role that meaning in life (MIL) plays in promoting human flourishing and serves as a coping mechanism for navigating life’s adversities and suffering (e.g., Czekierda et al. 2017; Damon 2008; Janoff-Bulman and Yopyk 2004; Linley and Joseph 2011; Steger 2012; Steger et al. 2009). For instance, individuals with higher levels of MIL tend to have more positive future orientations, hope, life satisfaction, happiness, and optimism (King et al. 2006; Mascaro and Rosen 2006; Steger and Frazier 2005; Steger et al. 2006; Steger et al. 2008). Individuals with a strong sense of meaning also exhibit better coping abilities when faced with adversity, enabling them to adapt more effectively to stressful situations. They experience lower levels of depression (Mascaro et al. 2004) and are less vulnerable to psychopathology (e.g., Debats 1999). Longitudinal studies have also found a positive association between higher levels of MIL and preventive behaviors among older individuals (Zhang et al. 2022).

However, the abstract and multifaceted nature of the construct of meaning in life presents a significant challenge in both conceptual and empirical terms. Although significant progress has been made in the assessment and understanding of meaning in life, some scholars (e.g., Heintzelman and King 2014; Leontiev 2013) have pointed out that the field still struggles with definitional ambiguity and overly simplistic approaches that fail to acknowledge the complex conceptual scope of MIL as a construct. For example, meaning and purpose have been claimed to be treated as “identical constructs in some instances and distinct constructs in others”, which further increases conceptual confusion (George and Park 2013, p. 365).

The current common integrative conceptualization conceptualizes MIL as comprised of three central facets: comprehension/coherence, purpose, and mattering/significance1 (George and Park 2013; Martela and Steger 2016). Each of the three facets taps into unique, fundamental dimensions of human experience, with varying psychological roots and distinct functions that may serve in human life (Steger et al. 2008). The first facet, coherence, reflects the cognitive aspect of meaning in life. It centers on individuals making sense of their life experiences and finding ways to render them comprehensible. People with a strong sense of coherence tend to feel that their life makes sense and is coherent (Baumeister 1991; George and Park 2016). This aspect is closely related to the Meaning Maintenance Model (MMM); (Heine et al. 2006) literature which proposes that meaning is rooted in the expected relationships and associations that individuals construct and apply to their surroundings (Heine et al. 2006). This is based on the idea that humans possess an innate drive to comprehend their environment; thus, when individuals perceive inconsistencies between their interpretation of a specific situation and their overarching beliefs and worldviews, it can lead to a sense of discomfort. This, in turn, can prompt efforts to make sense of the situation and reduce the distress experienced, in order to regain a sense of coherence (e.g., Park 2010; Proulx and Inzlicht 2012).

The second facet, purpose, refers to the motivational aspect and the degree to which individuals feel that their lives are being directed and motivated by valued life goals. In other words, it is defined as a “central, self-organizing life aim that organizes and stimulates goals, manages behaviors, and provides a sense of meaning” (McKnight and Kashdan 2009, p. 242). This aspect is closely related to the literature on goal engagement, self-regulation, and future orientation (see George and Park 2013; Martela and Steger 2016). The third facet of meaning, significance, refers to the existential aspect of meaning. The concept of significance is often used interchangeably with mattering, and it pertains to the perceived worth and value of one’s life and reflects the degree to which individuals believe that their existence holds importance and value. People who have a high sense of mattering/significance tend to believe that their presence carries considerable weight and has long-lasting impact (George and Park 2013; Martela and Steger 2016).

Overall, the tripartite view of meaning in life (MIL) unpacks the concept into three distinct facets or subconstructs, which allows for a more nuanced understanding and multidimensional assessment of MIL (MEMS; George and Park 2017). However, given that the common thread that runs through all three aspects of meaning in life is reflective interpretation of one’s experiences (Martela and Steger 2016), it is still unclear which specific underlying internal processes are at play in the development of each of these facets. Despite the burgeoning research and emerging understanding of the concept of meaning in life, its sources, and its contribution to human functioning, more knowledge is needed to better understand how people form a sense of coherence, purpose, and significance in their lives.

3. Character Strengths

The science of character strengths quickly unfolded to nearly 1000 studies by the end of 2023 (VIA Institute 2023). This multitude of studies includes examinations of character strengths measurement, classification/typology, outcomes, interventions, cross-cultural differences, expressions in different population groups (e.g., military, teachers, healthcare professionals, disability groups), contexts (organizations, education, healthcare, parenting), topical domains (e.g., mindfulness, peace psychology, nature connection, spirituality), and spans well-being areas (e.g., positive relationships, achievement, health behaviors) and adversity areas (e.g., stress, psychopathology, medical illness, conflicts, natural disasters, trauma, terrorism). The emerging science and practices have culminated in a multifaceted definition: Character strengths are positive personality traits that reflect personal identity (i.e., who we are), produce positive outcomes (e.g., boosting well-being such as positive emotions and meaning in life while managing adversity such as conflicts, anxiety, and stress), and contribute to the greater collective good (Niemiec 2018). The character strengths discussed here encompass the VIA Classification of character strengths, a comprehensive consensual nomenclature of 24 character strengths nesting under six virtues (Peterson and Seligman 2004). This work involved examining what is best in human beings across the globe (McGrath 2015), including remote cultures (Biswas-Diener 2006) and ancient philosophies, religions, and contemporary scientific literature (Dahlsgaard et al. 2005). The categorization of character strengths include, for example, curiosity and perspective (virtue of wisdom), bravery and honesty (virtue of courage), kindness and social intelligence (virtue of humanity), leadership and fairness (virtue of justice), humility and self-regulation (virtue of temperance), and hope and gratitude (virtue of transcendence) (Peterson and Seligman 2004).

4. Integration of Character Strengths and Meaning in Life

Despite growing interest and developments in both fields of meaning and character strengths, only scant and sparse scientific endeavors have been made thus far to integrate between them. For example, theoretical and practical exploration of the potential interplay between character strengths and spirituality has been suggested, specifically in terms of how spirituality involves the pursuit of the sacred and the search for meaning (Niemiec et al. 2020). In studies that have examined the construct of meaning, interesting findings have emerged. All character strengths were found to be associated with meaning in life and orientation toward meaning (Littman-Ovadia and Steger 2010; Peterson et al. 2007; Peterson and Park 2012). For instance, Peterson and colleagues (Peterson et al. 2007) conducted an exploratory investigation to examine how character strengths relate to the three authentic happiness orientations—pleasurable, engaging, and meaningful modes of existence (Seligman 2002). The study found that all 24 character strengths played a significant role in accounting for variance in all three happiness orientations, but the effect was the most pronounced in the meaningful orientation. The character strength of spirituality showed the strongest association with meaning, while the character strengths of zest, hope, and gratitude also displayed high correlations with meaning. Another study conducted by Allan (Allan 2015) showed that, not only were all 24 character strengths positively associated with a meaningful life, but also that a balance in specific strengths was crucial for experiencing a meaningful life. Their study found that high levels of alignment between the pairs of kindness and honesty, love and social intelligence, and hope and gratitude were linked to a meaningful life. Purpose, one of three core dimensions of meaning in life, has been examined in relation to character strengths. In the largest, global study of purpose and strengths to date (N = 60,000), the character strengths of hope, spirituality, zest, perseverance, and curiosity had the largest effect sizes with purpose (Weziak-Bialowolska et al. 2023). The study used the short form of the Purpose in Life Test (Schulenberg et al. 2011). Taken together, these findings suggest that, to experience a meaningful life, there is benefit to cultivating multiple character strengths, rather than focusing on one or two.

Although existing studies on integration have drawn a number of significant connections between character strengths and meaning in life and outlined promising directions, the samples have been limited, the measures have not separated or examined the components of meaning, and/or the studies have not examined nuances of meaning from the participant perspective. Previous studies have thus far focused on a general understanding of meaning, rather than taking into account a more nuanced and multidimensional perspective that considers the three components of meaning. Each component refers to a different dimension in the experience of meaning in life. This raises the question of which character strengths facilitate a sense of coherence, purpose, and significance, and why?

The objective of the present study was therefore to examine these components of meaning separately in order to more deeply understand the nuances of meaning: how individuals derive meaning from their world, pursue purpose, and feel significant to others and the world. Examining the ingredients or unique character strengths pathways for each will help to advance the science of meaning and the science of character strengths and potentially lead to more nuanced interventions for facilitating meaning in life. For example, the component of purpose, which involves transcending oneself, looking towards the future in a positive manner, and striving, may be expected to be associated with character strengths such as spirituality, hope, and perseverance. The component of significance or mattering, which refers to connections, may be associated with character strengths like love, as well as heart-based character strengths such as gratitude and kindness. The component of coherence or sense-making may be associated with character strengths that involve wisdom and knowledge, such as perspective (gaining a broader understanding), curiosity (exploring the world), and spirituality due to the element of making sense of the universe.

The present study takes an explorative mixed-methods approach to investigate how people from a large-scale sample view the interplay between their character strengths and specific aspects of meaning in life. It also takes into consideration the possible contribution of gender and age. Specifically, the study aimed to achieve the following objectives: (1) to analyze the correlation between valid measures of meaning components and character strengths, (2) to examine the relative importance of character strengths across gender and age differences, (3) to assess the personal significance of one’s character strengths for achieving each of the meaning components (i.e., coherence, purpose, and significance), and (4) to gain insights into the reasons behind the selection of each character strength and identify gender and age differences.

5. Method

5.1. Participants

This study was conducted using a convenience sample of individuals taking the VIA Inventory of Strengths (i.e., VIA Survey) to provide character strengths rank-order results to users of the www.viacharacter.org website (accessed on 1 May 2023). After completion of this measure, participants were invited to answer optional, additional questions with the following prompt: “Would you please answer some additional questions for research purposes? Your doing so would contribute to advancing the science of character strengths and you also would be providing permission to VIA to share your confidential responses with the research team. Thank you for your help!”. Participants were then invited to complete the 15 items in the Existential Meaning Scales Questionnaire and three open-ended items; this was followed by optional demographic items. Data was collected between 21 January and 28 January 2022. The total sample included 23,641 participants; 22,082 participants answered at least one of the 15 questions included in the Existential Meaning Scales Questionnaire; 20,739 answered all questions; 15,883 participants reported their age (up to 17: 2%; 18–24: 32%; 25–34: 23%; 35–44: 19%; 45–54: 14%; 55–64: 7%; 65+: 2%); 22,471 reported their country (the ten most prevalent countries were United States: 57%; Australia: 8%; Canada: 7%; United Kingdom: 5%; India: 2%; Philippines: 2%; Singapore: 2%; Japan: 1%; South Africa: 1%; New Zealand: 1%); 13,524 reported their household income (Less than USD 20,000: 21%; USD 20,000 to USD 34,999: 12%; USD 35,000 to USD 49,999: 10%; USD 50,000 to USD 74,999: 14%; USD 75,000 to USD 99,999: 11%; Over USD 100,000: 32%); 16,860 reported their gender (69.1% women, 29.4% males, 1.5% other); and 15,635 reported their education (No schooling completed: 3%; High school: 13%; Professional degree: 31%; Bachelor’s degree: 31%; Master’s degree: 18%; Doctorate degree: 3%).

5.2. Measures

Sociodemographic questionnaire. Participants were invited to provide information concerning their gender, age, education level, income levels, occupation, and nationality.

The Multidimensional Existential Meaning Scale (MEMS) (George and Park 2017) assesses the MIL dimensions coherence (or comprehension), purpose, and significance (or mattering), with a total of 15 items. Sample items include: “My life makes sense” (coherence subscale; “I have overarching goals that guide me in my life” (purpose subscale); “Whether my life ever existed matters even in the grand scheme of the universe” (significance subscale). Likert type responses are given on a seven-point scale (1 = Very strongly disagree; 7 = Very strongly agree). This self-report is described in the introduction section. In our study, scales were calculated for participants who answered at least 3 out of the 5 questions in each scale. Accordingly, 21,553 participants had valid values in all three scales. Alpha Cronbach’s internal reliability coefficients of the coherence, purpose, and significance scales in the present study were 0.90, 0.91, and 0.88, respectively, and for the full scale, 0.89.

VIA Inventory of Strengths (Peterson and Seligman 2004; VIA Institute 2003) measures 24 universal character strengths. The default measure for adults on the VIA Institute website is the VIA-IS-P, which is 96-question (four questions per strength), all positive-keyed, all using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “very much unlike me” to “very much like me.” Sample items from the VIA-IS-P include the following: I have many interests (curiosity); I never brag about my accomplishments (humility); Others come to be for advice (perspective); “I experience deep emotions when I see beautiful things” (appreciation of beauty) and “I always keep my promises” (honesty).

It is a reliable and valid measure of the 24 character strengths. Studies have shown the mean reliability across the 24 scales of the VIA-IS-P is 0.77, and when the criterion of strengths behaviors was assessed, the mean correlation across the 24 strengths of the VIA-IS-P with the behavior criterion was 0.53 (McGrath 2019). The original scales of the VIA-IS instruments showed sufficient reliability (e.g., alphas of 0.70 or greater; Peterson and Seligman 2004). Good reliability and concurrent validity for this scale was established (McGrath 2022).

Open-ended questions. We invited participants to select the character strength (from a drop-down list of the 24 strengths, with short definitions) that is most important for their coherence, significance, and purpose; they could choose the same or different strength for each of the three. After each drop-down selection, they were then invited to write their observations on how the character strength is helpful for making sense of the world (coherence), helpful in pursuing valued goals and providing a sense of purpose (purpose), and helpful in feeling they make a difference in the world (significance).

5.3. Data Analysis

5.3.1. Quantitative Analyses

We aimed to predict each of the three MIL dimensions and the overall meaning by the 24 character strengths, and therefore, stepwise regressions were conducted. Due to the large sample, the p-value for entering variables was set at 0.0001, and for removing variables at 0.0005. Multicollinearity was assessed using the tolerance index.

In order to assess whether the strengths selected by women differed from those selected by males, a difference in proportions test was calculated for each strength under each of the three questions. In order to assess whether the strengths selected were a function of age, a chi-square for independence test was calculated for each strength separately for each of the three questions. In both types of analyses, in order to avoid type I error due to multiple comparisons and large numbers, a conservative alpha of 0.001 was used.

In order to assess the relationship between the Multidimensional Existential Meaning Scales of coherence, purpose, and significance, and the five most frequent strengths selected for each of the three questions (making sense of life and the world, pursuing valued goals and providing a sense of purpose, and feeling that one’s existence is of significance and making a difference in the world), repeated measures ANOVA’s were calculated with the repeated measures of the values in coherence, purpose, and significance scales, and the independent variables were the groups of participants selecting each of the five most frequent strengths, separately for each of the three questions. Significant interactions between the existential scales and strengths were followed by Tukey HSD post hoc comparisons.

5.3.2. Qualitative Analyses

As mentioned, after selecting the character strength that is most helpful for each of the three topics in question, participants were asked to explain their selections. The answers were analyzed through a thematic analysis grounded in a social constructionist framework (Denzin and Lincoln 1994). Since the quantity of answers was so large, only the six most frequent strengths for each of the three questions were analyzed. The six most frequent strengths accounted for a majority of the answers. The specific percentages covered were coherence—56%, purpose—57%, and significance—59%.

For each one of the eighteen groups (6 strengths × 3 questions), 200 answers were selected using stratified non-proportional sampling. Answers were stratified by gender (males and women) and age (up to 24, 25–34, 35–44, 45–54, 55 and over), and 20 answers were randomly selected from each of the 10 strata (gender by age).

Overall, 3600 answers were analyzed (18 groups × 200 answers). For each of the 18 groups, the following process was followed: First, 100 answers were randomly selected within each group of 200, and two independent coders were asked to form themes by grouping those coded concepts that seemed to relate to the same phenomena. A third researcher combined the themes while taking into consideration similarities and differences between the coders, aiming at a maximum of 8 themes. For each final theme, two or three representative answers were selected for aiding in the classification process. In the next step, two independent coders coded the 200 sentences, tagging each sentence into the final themes. Each sentence could be tagged for more than one theme. Cohen’s kappa (Cohen 1960) was used as a measure of agreement between the two raters, separately for each theme. Only themes with Cohen’s kappa larger than 0.5 and including more than 20 sentences were further analyzed. In such analyses, only sentences that were categorized by both raters under the same theme were used. Chi square for independence tests were used to assess whether the proportion of men and women differed within each theme. Differences between the age groups were assessed using Linear-by-Linear Association Chi square tests.

6. Results

6.1. Quantitative Results

The number of participants included in the analyses presented below range between 20,739 and 22,082. Participants were mostly women (69%), from more than 100 countries, but mostly from the U.S. (57%), with an age mode of 18–24 years old (32%), a mode yearly income of over USD 100,000 (32%) and mostly with a professional degree (31%) or a Bachelor’s degree (31%).

Table 1 presents the means of the 24 universal character strengths and Pearson correlations between the strengths and the three MIL dimensions and the overall meaning value. The strengths with the highest means were honesty, kindness, fairness, appreciation of beauty, and judgment. All correlations were significant at the p < 0.001 level. The five character strengths that showed the highest correlations with overall meaning were hope, spirituality, gratitude, zest, and curiosity.

Table 1.

Means of the 24 character strengths and their Pearson correlations with MIL dimensions.

Stepwise regressions predicting the three MIL dimensions and the overall measure by the character strengths yielded extremely significant results. Table 2 summarizes the beta coefficients obtained from the four regressions performed. Coherence was significantly predicted by 15 of the character strengths, explaining 43% of its variance (R = 0.656, F(15, 22,070) = 1113, p < 0.001). The five strongest predictors were hope, gratitude, zest, kindness (negative beta, but a good value of tolerance = 0.672), and spirituality. The character strengths that did not enter the predicting formula were bravery, teamwork, creativity, fairness, honesty, humor, judgement, love of learning, and self-regulation. Purpose was significantly predicted by 14 of the character strengths, explaining 42% of its variance (R = 0.647, F(14, 21,915) = 1127, p < 0.001). The five strongest predictors were hope, curiosity, spirituality, forgiveness (negative beta, tolerance = 0.782), and appreciation of beauty (negative beta, tolerance = 0.712). The character strengths that did not enter the predicting formula were bravery, prudence, teamwork, creativity, fairness, gratitude, honesty, judgement, and kindness. Significance was significantly predicted by 16 of the character strengths, explaining 43% of its variance (R = 0.657, F(16, 21,993) = 1043, p < 0.001). The five strongest predictors were spirituality, hope, zest, gratitude, and judgment (negative beta tolerance = 0.583). The character strengths that did not enter the predicting formula were bravery, teamwork, creativity, forgiveness, forgiveness, honesty, and perseverance and social intelligence. Overall meaning was significantly predicted by 17 of the character strengths, explaining 55% of its variance (R = 0.743, F(17, 22,072) = 1604, p < 0.001). The five strongest predictors were hope, spirituality, curiosity, zest, and gratitude. The character strengths that did not enter the predicting formula were bravery, teamwork, creativity, fairness, forgiveness, honesty, and love of learning.

Table 2.

Beta regression coefficients obtained in the regressions predicting the three MIL dimensions and the overall measure by the character strengths.

Among participants who offered character strengths selections to meaning pathways, their highest character strengths on the VIA Inventory were honesty, kindness, fairness, appreciation of beauty, and judgment. This aligns well with reports on the frequency of character strengths across countries (e.g., McGrath 2015).

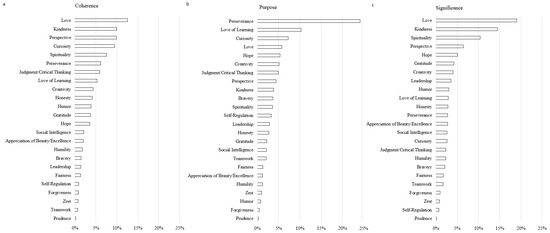

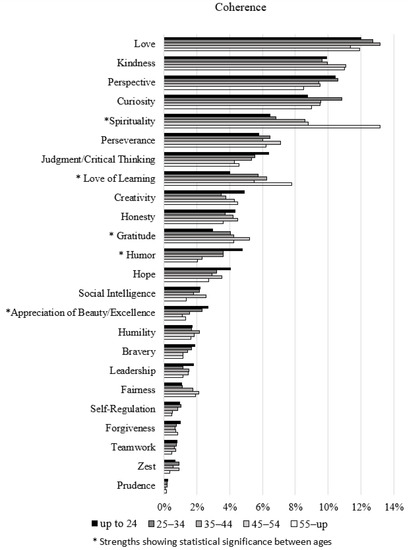

Figure 1a–c present the percent of participants selecting each strength (in descending order) in answer to the questions “Select the character strength that is most helpful for making sense of your life and the world” (Figure 1a), “Select the character strength that is most helpful to you in pursuing valued goals and providing you a sense of purpose” (Figure 1b), and “Select the character strength that is most helpful for feeling that your existence is of significance and that you make a difference in the world” (Figure 1c).

Figure 1.

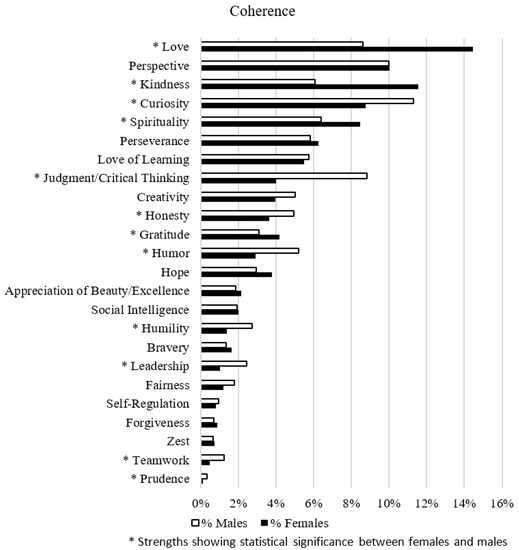

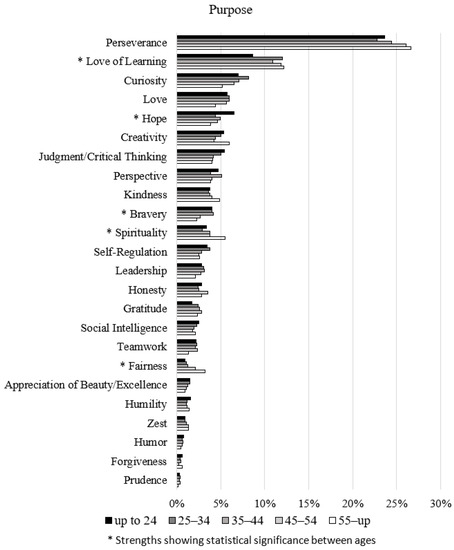

Percentage of participants selecting each of the character strengths following the questions (a) “Select the character strength that is most helpful for making sense of your life and the world” (Coherence), (b) “Select the character strength that is most helpful to you in pursuing valued goals and providing you a sense of purpose” (Purpose), and (c) “Select the character strength that is most helpful for feeling that your existence is of significance and that you make a difference in the world” (Significance). Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4 present the percentage of women and men selecting each strength for coherence (Figure 2), purpose (Figure 3), and significance (Figure 4). Strengths reaching statistical significance between women and men are marked by an asterisk preceding the strength name. As can be seen in Figure 2, for the question “Select the character strength that is most helpful for making sense of your life and the world?”, women significantly chose more love, kindness, spirituality, and gratitude than men, whereas men significantly chose more curiosity, judgment/critical thinking, honesty, humor, humility, leadership, teamwork, and prudence as compared to women.

Figure 2.

Percentage of men and women selecting each of the character strengths following the question “Select the character strength that is most helpful for making sense of your life and the world”.

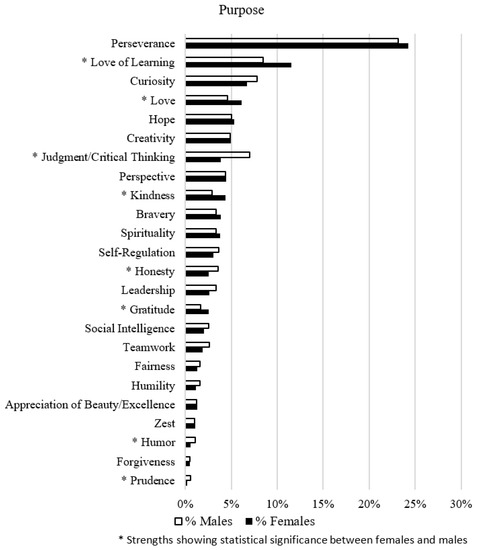

Figure 3.

Percentage of men and women selecting each of the character strengths following the question “Select the character strength that is most helpful to you in pursuing valued goals and providing you a sense of purpose”.

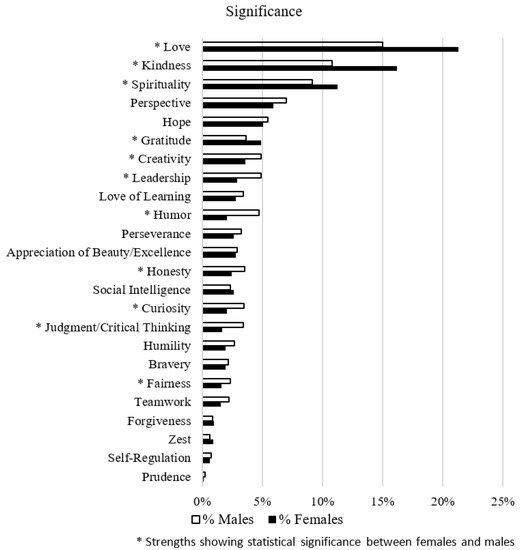

Figure 4.

Percentage of men and women selecting each of the character strengths following the question “Select the character strength that is most helpful for feeling that your existence is of significance and that you make a difference in the world”.

As can be seen in Figure 1a, the five most frequent strengths for making sense of life and the world were love, kindness, perspective, curiosity, and spirituality. As can be seen in Figure 1b, the five most frequent strengths for helping pursue valued goals and providing a sense of purpose were perseverance, love of learning, curiosity, love, and hope. As can be seen in Figure 1c, the five most frequent strengths for helping feeling that one’s existence is of significance and making a difference in the world were love, kindness, spirituality, perspective, and hope.

As can be seen in Figure 3, for the question “Select the character strength that is most helpful to you in pursuing valued goals and providing you a sense of purpose”, women significantly chose more love of learning, love, kindness, and gratitude than men, whereas men significantly chose more judgment/critical thinking, honesty, humor, and prudence as compared to women.

As can be seen in Figure 4, for the question “Select the character strength that is most helpful for feeling that your existence is of significance and that you make a difference in the world”, women significantly chose more love, kindness, spirituality, and gratitude than men, whereas men significantly chose more creativity, leadership, humor, honesty, curiosity, judgment/critical thinking, and fairness, as compared to women.

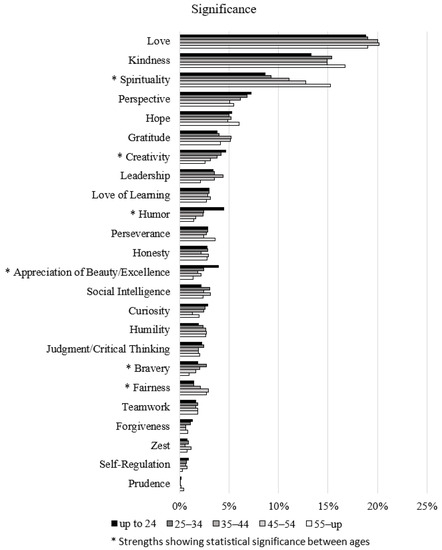

Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7 present the percentage of each of five age groups selecting each strength for coherence (Figure 5), purpose (Figure 6), and significance (Figure 7). Strengths reaching statistical significance between ages are marked by an asterisk preceding the strength name. As can be seen in Figure 5, for the question “Select the character strength that is most helpful for making sense of your life and the world?”, a significant increase through lifetime was obtained for spirituality, love of learning (with an exception at age 45–54), and gratitude (with an exception at age 55+), while a significant decrease was obtained for humor and appreciation of beauty/excellence (with an exception at age 45–54).

Figure 5.

Percentage of participants by age group selecting each of the character strengths following the question “Select the character strength that is most helpful for making sense of your life and the world”.

Figure 6.

Percentage of participants by age group selecting each of the character strengths following the question “Select the character strength that is most helpful to you in pursuing valued goals and providing you a sense of purpose”.

Figure 7.

Percentage of participants by age group selecting each of the character strengths following the question “Select the character strength that is most helpful for feeling that your existence is of significance and that you make a difference in the world”.

As can be seen in Figure 6, for the question “Select the character strength that is most helpful to you in pursuing valued goals and providing you a sense of purpose”, a significant increase through lifetime was obtained for love of learning (with an exception at age 25–34), spirituality (with an exception at age 25–34), and fairness, while a significant decrease was obtained for hope (with an exception at age 25–34) and bravery (with exceptions at ages up to 24 and 25–34).

As can be seen in Figure 7, for the question “Select the character strength that is most helpful for feeling that your existence is of significance and that you make a difference in the world”, a significant increase through lifetime was obtained for spirituality and fairness (with an exception at age 55-up) while a significant decrease was obtained for creativity, humor, appreciation of beauty/excellence (with an exception at age 45–54), and bravery (with an exception at age up to 24).

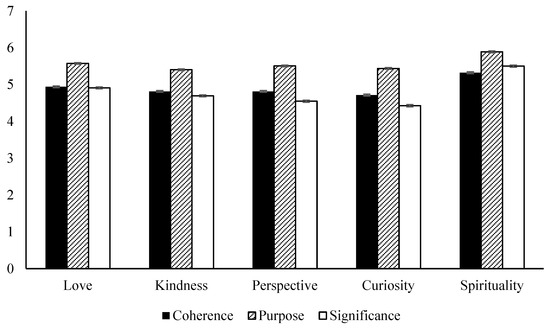

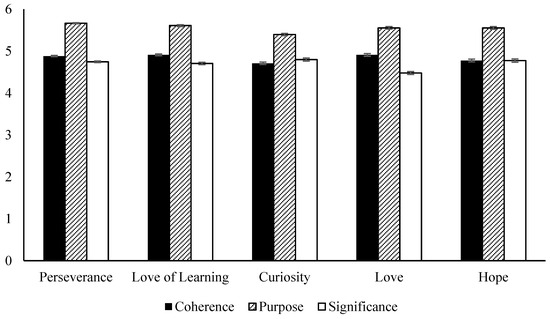

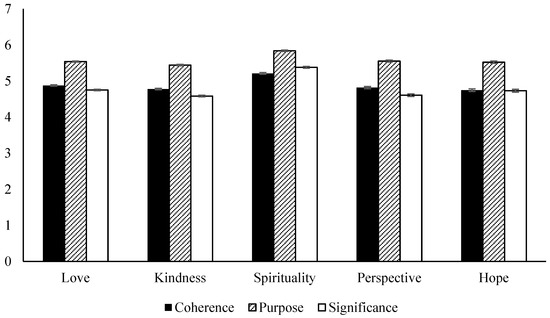

Repeated measures ANOVA with the repeated measures of the values in coherence, purpose, and significance and the five most frequent strengths selected for making sense of life and the world (coherence) as the independent variable, yielded a significant interaction (F(8, 21,142) = 62.16, p < 0.001, partial eta squared = 0.023), see Figure 8. Post hoc tests revealed that, in all cases, purpose was always significantly higher than coherence and significance, but the differences between coherence and significance were a function of the strength selected. Participants who selected love did not significantly differ between coherence and significance, however participants who selected kindness, perspective, and curiosity had significantly higher values in coherence than in significance (all p’s < 0.001), while participants who selected spirituality had significantly higher values in significance than in coherence (p < 0.001).

Figure 8.

Means of the scales of coherence, purpose, and significance separately for participants who selected the five most frequent strengths for making sense of life and the world.

Repeated measures ANOVA with the repeated measures of the values in coherence, purpose, and significance and the five most frequent strengths selected for pursuing valued goals and providing a sense of purpose as the independent variable yielded a significant interaction (F(8, 22,064) = 8.96, p < 0.001, partial eta squared = 0.003), see Figure 9. Post hoc tests revealed that, in all cases, purpose was always significantly higher than coherence and significance, but the differences between coherence and significance were a function of the strength selected. Participants who selected hope did not significantly differ between coherence and significance, however participants who selected perseverance, love of learning, and love had significantly higher values in coherence than in significance (all ps < 0.001), while participants who selected curiosity had significantly higher values in significance than in coherence (p < 0.001).

Figure 9.

Means of the scales of coherence, purpose, and significance separately for participants who selected the five most frequent strengths for pursuing valued goals and providing a sense of purpose.

Repeated measures ANOVA with the repeated measures of the values in coherence, purpose, and significance and the five most frequent strengths selected for feeling that the existence is of significance and making a difference in the world as the independent variable, yielded a significant interaction (F(8, 23,380) = 40.57, p < 0.001, partial eta squared = 0.014), see Figure 10. Post hoc tests revealed that, in all cases, purpose was always significantly higher than coherence and significance, but the differences between coherence and significance were a function of the strength selected. Participants who selected hope did not significantly differ between coherence and significance, however participants who selected love, kindness, and perspective had significantly higher values in coherence than in significance (all p’s < 0.001), while participants who selected spirituality had significantly higher values in significance than in coherence (p < 0.001).

Figure 10.

Means of the scales of coherence, purpose, and significance separately for participants who selected the five most frequent strengths for feeling that the existence is of significance and making a difference in the world.

6.2. Qualitative Results

Table 3 presents the themes obtained for the explanation of each strength, and for each of the three questions used. Themes with Cohen’s kappa over 0.5 are marked with a gray background. As can be seen in the table, the number of reliable themes per strength ranged between 0 and 4, with a mode of 2.

Table 3.

Themes obtained for the explanation of each strength, for each of the three questions asked.

Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6, display illustrative instances of explanations corresponding to themes that describe strengths with Cohen’s kappa > 0.5.

Table 4.

Explanations provided by the participants regarding their selection of character strengths that contribute to coherence, categorized into thematic groups.

Table 5.

Explanations provided by the participants regarding their selection of character strengths that contribute to purpose, categorized into thematic groups.

Table 6.

Explanations provided by the participants regarding their selection of character strengths that contribute to significance, categorized into thematic groups.

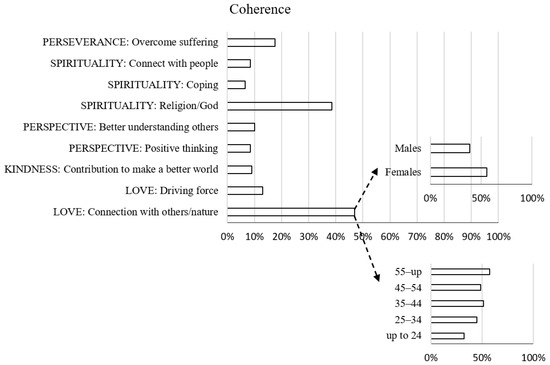

Figure 11 presents the percentage of sentences falling under each of the themes, only for themes that were found to be sufficiently reliable (Cohen’s kappa > 0.5), as explanations of the strengths selected for question 1: “Select the character strength that is most helpful for making sense of your life and the world?”. The figure also presents themes that were found to significantly differ between men and women and between age groups. As can be seen for the theme “connection with others/nature” as an explanation for selecting the strength love, women selected this theme significantly more than men (p = 0.016), and there was a significant linear trend for increasing with age (p = 0.03).

Figure 11.

Percentage of sentences under each of the reliable themes for the character strengths that are most helpful for making sense of life and the world, and significant differences of gender and age.

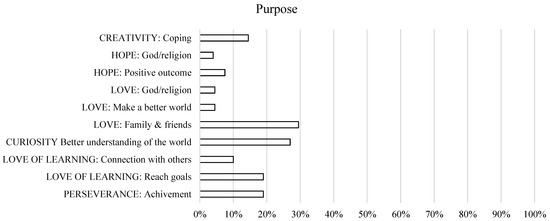

Figure 12 presents the percentage of sentences falling under each of the themes, only for themes that were found to be sufficiently reliable (Cohen’s kappa > 0.5), as explanations of the strengths selected for question 2: “Select the character strength that is most helpful to you in pursuing valued goals and providing you a sense of purpose”. No significant differences were obtained between men and women, nor as a function of age.

Figure 12.

Percentage of sentences under each of the reliable themes for the character strengths that are most helpful in pursuing valued goals and providing a sense of purpose.

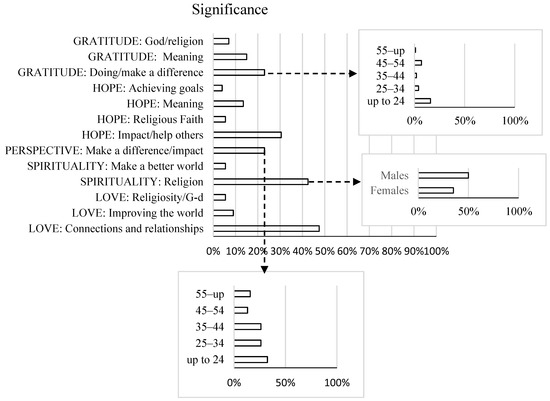

Figure 13 presents the percentage of sentences falling under each of the themes, only for themes that were found to be sufficiently reliable (Cohen’s kappa > 0.5), as explanations of the strengths selected for question 3: “Select the character strength that is most helpful for feeling that your existence is of significance and that you make a difference in the world”. The figure also presents themes that were found to significantly differ between men and women and between age groups. As can be seen for the themes “doing/making a difference” as an explanation for selecting the strength gratitude, and “make a difference/impact”, as an explanation for selecting the strength perspective, a significant linear reduction was obtained as a function of age (p = 0.004 and p = 0.03, respectively). In addition, men significantly selected the theme religion more than women (p = 0.02), as an explanation for the strength spirituality.

Figure 13.

Percentage of sentences under each of the reliable themes for the character strengths that help in feeling that existence is of significance and that one can make a difference in the world, and significant differences of gender and age.

7. Discussion

The results of the present study suggest that character strengths displayed strong associations with not only meaning in life in general, but with each dimension of meaning in life. This suggestion is based on two independent results: (1) Correlations between meaning in life dimensions and strengths means derived from the VIA Inventory of Strengths; (2) comparisons between dimensions of meaning in life among participants who chose their most important character strengths for providing coherence, purpose and significance. From the first series of results all character strengths were strongly correlated with the dimensions of meaning in life. The character strengths that showed the highest correlations with total meaning were hope, spirituality, gratitude, zest, and curiosity. These are the same top five strengths found in the initial study that looked at character strengths and meaning by Peterson and colleagues (Peterson et al. 2007), using a different measure of meaning. There is convergence with the findings of other studies that have generally found similar character strengths (curiosity, spirituality, gratitude) as well as others (appreciation of beauty, social intelligence, perspective) to be related to meaning when informant reports were woven into the study (Wagner et al. 2019). Interestingly, these same five strengths we found to be most correlated with total meaning were also the best predictors of total meaning, indicating their unique contribution to meaning in life. Specific to the meaning dimensions, the strongest character strengths predictors were hope, spirituality, zest, gratitude, and appreciation of beauty (the latter was a negative relationship) for coherence; hope, spirituality, curiosity, forgiveness, and appreciation of beauty (the latter two were negative relationships) for purpose; and spirituality, hope, zest, gratitude, and judgment (the latter was a negative relationship) for significance. The strengths of hope and spirituality reflect the most consistent, general, impactful role across the dimensions of meaning indicating the importance of an orientation that is based in future-mindedness, optimism, and the sacred. The additional role of an exploratory approach, especially for making sense of the world, an energetic and appreciative approach, especially for displaying purpose and feeling like one matters to others, are also noteworthy and substantial. The negative relationships for appreciation of beauty, forgiveness, and judgment for different dimensions are interesting. The negative values could be a result of multi-collinearity. However, since tolerance values were in the acceptable range, it seems that the values represent a negative unique contribution once the effects of other variables are taken into account. It is possible that these findings reflect an overuse of strengths that impact the meaning dimension, as it has been discussed and empirically supported that too much use of character strengths can be associated with negative results and might reflect an imbalance or a narrowing of one’s attention and resources (Niemiec 2019). Further exploration might examine whether too much aesthetic and sensory appreciation of beauty, letting go (forgiveness), and analysis/critique (judgment) might have negative ramifications for the pursuit of meaning in life.

From the second series of results involving participants’ reports on the strength most important for them to use for each pathway, some character strengths aligned with all three pathways (e.g., love) while others were uniquely strong for one dimension in particular (e.g., hope, for significance). While curiosity, spirituality, and hope were featured among the top five participants’ self-reports, there were additional strengths that featured strongly (e.g., love, kindness, and perspective). This indicates that there are some similarities and differences in individuals’ preferences for strengths’ use and their character connection to meaning in life. This also points to the importance of scientific studies continuing to differentiate among the elements of life meaning (e.g., (George and Park 2016; Martela and Steger 2016; Martela and Steger 2023), as well as the different contributions that core parts of positive personality can have on meaning.

More specifically, the five most frequently selected strengths which facilitate a sense of comprehension were love, kindness, perspective, curiosity, and spirituality. The five most frequent strengths which facilitate a sense of purpose were perseverance, love of learning, curiosity, love, and hope. The five most frequent strengths which facilitate a sense of significance/mattering were love, kindness, spirituality, perspective, and hope. Taking the character strengths and tripartite elements of meaning together, we suggest that, in order to optimally make sense of the world, feel that one’s existence is of significance, and pursue purpose-driven goals, people might need to turn deep within, up and beyond, and sideways and interconnectedly in their life meaning journey (Mayseless and Russo-Netzer 2017). The frequently selected character strengths support this notion. The turning inward (i.e., deep within) for exploration is facilitated by curiosity and love of learning to build knowledge and foster greater wisdom, and perhaps using the determination of perseverance and the optimism of hope to support the inward work toward meaning. The sideways and interconnected element involving finding meaning with others is likely facilitated by the character strength patterns of love and kindness and perhaps also the honesty and humor strengths to bring authenticity and also fun and lightheartedness to relationships. The up and beyond element is supported by the connecting outside oneself with the spirituality strength and the wider, long-view quality brought by the strength of perspective. These examples show the synergy brought forth by the common patterns of character strengths expression across the dimensions of meaning and their importance to the wider journey of life meaning.

Interestingly, love was found to be the character strength aligned with all three pathways of meaning in life. This reflects the centrality of love to individuals’ experience of meaning in life, essentially representing that which makes us “come most fully alive and feel most fully human” (Fredrickson 2013, p. 10), and “the ultimate and highest goal to which man can aspire” (Frankl 1946, p. 57). The unique characteristics of connection, expanded awareness of oneself, others, and the world, and a sense of transcendence beyond one’s self-interest (Fredrickson 2013), which constitute aspects of the character strength of love, may be at play in people’s understanding and cultivation of their sense of meaning in life. Through love, individuals can establish meaningful relationships and connections with others, which in turn can provide a sense of purpose and direction in life, as well as providing them with a sense of significance and mattering. Love can also help individuals make sense of their experiences, as they can view their experiences and challenges in the context of the broader human experience and feel a sense of empathy and understanding for others who have faced similar difficulties.

The gender differences that emerged were quite interesting. For coherence and making sense of the world, women significantly chose more love, kindness, spirituality, and gratitude, whereas men significantly chose more curiosity, judgment/critical thinking, honesty, humor, humility, leadership, teamwork, and prudence. In terms of the dimension of purpose, women significantly chose more love of learning, love, kindness, and gratitude, while men significantly chose more judgment/critical thinking, honesty, humor, and prudence. In terms of significance and having a sense of mattering, women significantly chose more love, kindness, spirituality, and gratitude, whereas men significantly chose more creativity, leadership, humor, honesty, curiosity, judgment/critical thinking, and fairness.

Thus, for the three dimensions of meaning, women were significantly higher in selecting traditional heart-based strengths (e.g., love, kindness, gratitude) while men were significantly higher in choosing traditional mind-oriented strengths (e.g., judgment, honesty, prudence). These patterns appear to align with traditional gender roles relating to women and emotions/heart and men and thinking/mind. Perhaps this indicates the preferences to explore perceptions of meaning per one’s default toward mind or heart. The differences for women also align with the results of a meta-analysis of gender differences in character strengths that revealed, across studies, only four differences, which were all in favor of women being higher than men in terms of selecting love, kindness, gratitude, and appreciation of beauty (Heintz et al. 2017) (in our study, the first three being salient for women across all three meaning dimensions). Future studies should aim to further unpack these differential trends between men and women in their salient character strengths in relation to the three meaning components.

Age trends showed an increase over the years for spirituality, love of learning, and gratitude for the coherence pathway. This indicates an ongoing quest for learning, a seeking of the sacred in life and trying to make more sense of the universe, and an appreciation for life that grows over time. The decrease in humor and appreciation of beauty for coherence over the years might reflect a growing seriousness toward life (humor) and decreased attentiveness and use of senses to engage and appreciate the world. For purpose, the increase over the years in love of learning, spirituality, and fairness shows the importance of valued life goals involving growth in learning, an inclusiveness of others, and connections outside oneself. The decrease in hope and bravery over the years for purpose might reflect a decreased willingness to take risks and move out of one’s comfort zone (Russo-Netzer and Cohen 2022) and less hopefulness about the diminishing future. For significance, spirituality and fairness increased through the lifetime showing, again, the crucial role of the pursuit of or communing with the sacred for meaning-making. The trend for increases in fairness indicates a pursuit of a more emotional meaning—a mattering—and that the pursuit and expression of fairness and justice is important for mattering. For significance, there was a decrease in creativity, humor, appreciation of beauty, and bravery. These might reflect a decreasing use of these strengths in relationships as their focus (except for humor) is more intrapersonal than interpersonal. Future research may further explore this direction, especially given the fast-paced digital world of our time which prioritizes stimulation and distraction over depth and nuance of individuals’ engagement in creativity, humor, appreciation of beauty, and bravery.

When comparing the three components of meaning in life, we found that purpose was the most important, irrespectively of the character strength selected. However, differences existed between coherence and significance. In terms of differences between character strengths for making sense of life and the world, participants who selected kindness, perspective, and curiosity had significantly higher values in coherence than in significance, while participants who selected spirituality had significantly higher values in significance than in coherence. For character strengths related to purpose, participants who selected perseverance, love of learning and love had significantly higher values in coherence than in significance, while participants who selected curiosity had significantly higher values in significance than in coherence. In terms of significance, participants who selected love, kindness, and perspective had significantly higher values in coherence than in significance, while participants who selected spirituality had significantly higher values in significance than in coherence. These findings further highlight that people are able to distinguish between the three dimensions of meaning (Martela and Steger 2023) and underscores potential underlying mechanisms which support each as a unique experience and manifestation in people’s lives.

The qualitative analysis helped delve into nuances of responses exploring character strength uses for coherence, significance, and purpose. In examining themes found to be sufficiently reliable, the most common themes for coherence, starting with the most frequent, were connecting with others and nature (love), connecting through religion/God (spirituality), overcoming suffering (perseverance), love as a driving force (love), better understanding others (perspective), connecting with people (spirituality), positive thinking (perspective), contribution to making a better world (kindness), and coping (spirituality). These dominant themes are what individuals identify as central ways to use one’s character strengths to make sense of one’s life and the world.

For purpose, the most common themes, starting with the most frequent, were family and friends (love), better understanding of the world (curiosity), reaching goals (love of learning), achievement (perseverance), coping (creativity), connection with others (love of learning), positive outcomes (hope), God/religion (love), making a better world (love), God/religion (hope). These purpose themes show several ways to use one’s character strengths in the service of pursuing valued goals; they reflect achievement to generate purpose, connections to family, friends, God, and the larger world, and coping with challenges along the way.

For significance, the most common themes, starting with the most frequent, were connections and relationships (love), religion/God (spirituality), impacting/helping others (hope), doing/making a difference (gratitude), impacting/making a difference (perspective), meaning (gratitude), meaning (hope), improving the world (love), God/religion (gratitude), making a better world (spirituality), religiosity/God (love), religious faith (hope), and achieving goals (hope). The use of different character strengths to connect spiritually, to engage in religious practices, and to make a positive impact and help others were most common for the meaning dimension of significance. These are themes of mattering—feeling that one makes a difference for the world and in the lives of others.

These qualitative themes may point specifically to how character strengths can serve as pathways to each dimension of meaning, and might thereby be important avenues for meaning-based interventions. For example, a large percentage of people would seem to relate directly to interventions that target the character strength of love for building relationships in order to foster deeper personal mattering. At the same time, a good percentage of people would relate to an intervention targeting one’s curiosity in order to build a better understanding of the world and thereby enhance purpose. For coherence, an intervention might target love to help people connect with nature to make greater sense of the world or target perseverance to facilitate understanding by creating new ways to overcome suffering.

8. Limitations

Despite the vast and diverse sample, more than 50% of the sample comprised of American participants. This may raise the possibility that the overall conclusions drawn from the study may not necessarily represent other populations, particularly in view of previous research highlighting the existence of cross-cultural variations in terms of the experience of meaning in life (e.g., Abu-Raiya et al. 2021; Russo-Netzer 2019; Steger et al. 2008).

In addition, the study relied on self-reported surveys as the main data source, a method commonly used to evaluate subjective experiences (Sheldon and Lyubomirsky 2007). However, this approach has the potential to generate a social desirability bias. To complement and enhance the credibility of the findings, future studies could employ additional methods such as behavioral measures to provide supporting evidence and reduce dependence on self-reported data. Finally, our sample overrepresented young people (76% of participants were under the age of 45), and women (70%). Accordingly, our results should be interpreted with reflection and further explored across gender and various life stages.

9. Conclusions and Future Directions

The character strengths of the VIA Classification have a robust connection with meaning in life. This is an intersection warranting substantial future investigation. The integration of character strengths and related areas such as mindfulness (Niemiec 2023) and spirituality (Niemiec et al. 2020) have articulated bidirectional pathways and explored interventions for each direction. For the latter, researchers described a grounding pathway by which character strengths bring balance and foundation to spirituality, and a sanctification pathway by which spirituality infuses a sacredness and deeper meaning to character strengths expression. As life meaning—and its dimensions—have many parallels with secular spirituality, these two directions of the grounding path and the sanctification path might be applied and explored in the character strengths and life meaning synergy.

As individual and collective pathways to each dimension of meaning, there appears to be substantial potential for designing intervention studies. As there are a myriad of strong relationships between character strengths and areas of meaning, different intervention approaches might be considered. Populations and settings in which more life meaning is needed and/or most desired might be a focal point. Researchers and practitioners have several options, such as taking a global approach and targeting the boosting of the character strengths most strongly discussed by participants across the dimensions (e.g., love, kindness, perspective, spirituality). Another option is to focus on one dimension of meaning and target the top character strengths aligned therein; for example, a purpose researcher wanting to further explore the synergy of purpose and character strengths but also test interventions might frame a set of interventions for perseverance, love of learning, curiosity, love, and hope. A third intervention option is to target the signature strengths (not a focal point in this paper) of the individuals, which are the highest ranked strengths most central to the person’s identity. As there is substantial research from randomized studies on the benefit of using signature strengths in new ways (see meta-analysis on this intervention, (Schutte and Malouff 2019), this could be applied to meaning in life. In other words, participants could be invited to use their highest character strength in one way each day that builds significance (or coherence or purpose) in their life. (For examples of evidence-based interventions on each of the 24 character strengths, see Niemiec 2018). Our findings also revealed interesting insights about gender and age patterns. The intervention approaches discussed above could be applied accordingly to men only, women only, or particular age groups.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.R.-N. and R.M.N.; methodology, P.R.-N. and R.T.; validation, P.R.-N., R.T. and R.M.N.; data curation R.M.N.; writing—original draft preparation, P.R.-N.; writing—review and editing, R.T., R.M.N. and P.R.-N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the use of secondary, third-party data.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data can be made available upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. One of the authors is employed by the VIA Institute where the anonymized data was collected.

Note

| 1 | Please note that for purposes of consistency, this paper uses the term “coherence” as synonym for “comprehension”, and the term “significance” as synonym for “mattering”. |

References

- Abu-Raiya, Hisham, Tali Sasson, and Pninit Russo-Netzer. 2021. Presence of meaning, search for meaning, religiousness, satisfaction with life and depressive symptoms among a diverse Israeli sample. International Journal of Psychology 56: 276–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allan, Blake A. 2015. Balance among character strengths and meaning in life. Journal of Happiness Studies 16: 1247–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aristotle. 2001. Nichomachean ethics. In The Basic Works of Aristotle. Edited by Richard McKeon. New York: The Modern Library, pp. 928–1112. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister, Roy F. 1991. Meanings of Life. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Biswas-Diener, Robert. 2006. From the equator to the North Pole: A study of character strengths. Journal of Happiness Studies 7: 293–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Jacob. 1960. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement 20: 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czekierda, Katarzyna, Anna Banik, Crystal L. Park, and Aleksandra Luszczynska. 2017. Meaning in life and physical health. Health Psychology Review 11: 387–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahlsgaard, Katherine, Christopher Peterson, and Martin E. P. Seligman. 2005. Shared virtue: The convergence of valued human strengths across culture and history. Review of General Psychology 9: 203–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damon, William. 2008. The Path to Purpose: Helping Our Children Find Their Calling in Life. New York: Simon and Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Debats, Dominique Louis. 1999. Sources of meaning: An investigation of significant commitments in life. Journal of Humanistic Psychology 39: 30–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denzin, Norman K., and Yvonna S. Lincoln, eds. 1994. Handbook of Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Frankl, Viktor E. 1946. Man’s Search for Meaning. New York: Pocket Books. [Google Scholar]

- Frankl, Viktor E. 1963. The Will to Meaning: Foundations and Applications of Logotherapy. New York: Meridian. [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson, Barbara L. 2013. Love 2.0: Creating Happiness and Health in Moments of Connection. London: Penguin Book. [Google Scholar]

- George, Login S., and Crystal L. Park. 2013. Are meaning and purpose distinct? An examination of correlates and predictors. The Journal of Positive Psychology 8: 365–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, Login S., and Crystal L. Park. 2016. Meaning in life as comprehension, purpose, and mattering. Review of General Psychology 20: 205–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, Login S., and Crystal L. Park. 2017. The multidimensional existential meaning scale: A tripartite approach to measuring meaning in life. The Journal of Positive Psychology 12: 613–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heine, Steven J., Travis Proulx, and Kathleen D. Vohs. 2006. The meaning maintenance model: On the coherence of social motivations. Personality and Social Psychology Review 10: 88–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heintzelman, Samantha J., and Laura A. King. 2014. Life is pretty meaningful. American Psychologist 69: 561–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heintz, Sonja, Christoph Kramm, and Willibald Ruch. 2017. A meta-analysis of gender differences in character strengths and age, nation, and measure as moderators. Journal of Positive Psychology 14: 103–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janoff-Bulman, Ronnie, and Darren J. Yopyk. 2004. Random outcomes and valued commitments: Existential dilemmas and the paradox of meaning. In Handbook of Experimental Existential Psychology. Edited by Jeff Greenberg, Sander. L. Koole and Tom Pyszczynski. New York: Guilford Press, pp. 122–38. [Google Scholar]

- King, Laura A., Joshua A. Hicks, Jennifer L., Krull, and Amber K. Del Gaiso. 2006. Positive affect and the experience of meaning in life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 90: 179–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leontiev, Dmitry A. 2013. Personal meaning: A challenge for psychology. The Journal of Positive Psychology 8: 459–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linley, Alex P., and Stephen Joseph. 2011. Meaning in life and posttraumatic growth. Journal of Loss and Trauma 16: 150–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littman-Ovadia, Hadassah, and Michael F. Steger. 2010. Character strengths and well-being among volunteers and employees: Towards an integrative model. The Journal of Positive Psychology 5: 419–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martela, Frank, and Michael F. Steger. 2016. The three meanings of meaning in life: Distinguishing coherence, purpose, and significance. The Journal of Positive Psychology 11: 531–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martela, Frank, and Michael F. Steger. 2023. The role of significance relative to the other dimensions of meaning in life. An examination utilizing the three dimensional meaning in life scale (3DM). The Journal of Positive Psychology 18: 606–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascaro, Nathan, and David H. Rosen. 2006. The role of existential meaning as a buffer against stress. Journal of Humanistic Psychology 46: 168–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascaro, Nathan, David H. Rosen, and Leslie C. Morey. 2004. The development, construct validity, and clinical utility of the spiritual meaning scale. Personality and Individual Differences 37: 845–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayseless, Ofra, and Pninit Russo-Netzer. 2017. A vision for the farther reaches of spirituality: A phenomenologically based model of spiritual development and growth. Spirituality in Clinical Practice 4: 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, Robert E. 2015. Character strengths in 75 nations: An update. Journal of Positive Psychology 10: 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, Robert E. 2019. Technical Report: The VIA Assessment Suite for Adults: Development and Initial Evaluation, rev. ed. Cincinnati: VIA Institute on Character. [Google Scholar]

- McGrath, Robert E. 2022. A summary of construct validity evidence for two measures of character strengths. Journal of Personality Assessment 105: 302–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKnight, Patrick E., and Todd B. Kashdan. 2009. Purpose in life as a system that creates and sustains health and well-being: An integrative, testable theory. Review of General Psychology 13: 242–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemiec, Ryan M. 2018. Character Strengths Interventions: A Field-Guide for Practitioners. Boston: Hogrefe. [Google Scholar]

- Niemiec, Ryan M. 2019. Finding the golden mean: The overuse, underuse, and optimal use of character strengths. Counseling Psychology Quarterly 32: 453–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemiec, Ryan M. 2023. Mindfulness and Character Strengths: A Practitioner’s Guide to MBSP, 2nd ed. Göttingen: Hogrefe. [Google Scholar]

- Niemiec, Ryan. M., Pninit Russo-Netzer, and Kenneth Pargament. 2020. The decoding of the human spirit: The integration of spirituality with the science and practice of character strengths. Frontiers in Psychology 11: 2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Crystal L. 2010. Making sense of the meaning literature. Psychological Bulletin 136: 257–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, Christopher, and Martin E. P. Seligman. 2004. Character Strengths and Virtues: A Handbook and Classification. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, Christopher, and Nansook Park. 2012. Character strengths and the life of meaning. In The Human Quest for Meaning: Theories, Research, and Applications. London: Routledge, pp. 277–95. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, Christopher, Willibald Ruch, Ursula Beermann, Nansook Park, and Martin E. P. Seligman. 2007. Strengths of character, orientations to happiness, and life satisfaction. The Journal of Positive Psychology 2: 149–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proulx, Travis, and Michael Inzlicht. 2012. The five “A”s of meaning maintenance: Finding meaning in the theories of sense-making. Psychological Inquiry 23: 317–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo-Netzer, Pninit. 2019. Prioritizing meaning as a pathway to meaning in life and general well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies 20: 1863–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo-Netzer, Pninit, and Geoffrey L. Cohen. 2022. If you’re uncomfortable, go outside your comfort zone’: A novel behavioral ‘stretch’ intervention supports the well-being of unhappy people. Journal of Positive Psychology 18: 394–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, Carol D., and Burton H. Singer. 2008. Know thyself and become what you are: A eudaimonic approach to psychological well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies 9: 13–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulenberg, Stefan E., Lindsay W. Schnetzer, and Erin M. Buchanan. 2011. The purpose in life test-short form: Development and psychometric support. Journal of Happiness Studies 12: 861–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schutte, Nicola S., and John M. Malouff. 2019. The impact of signature character strengths interventions: A meta-analysis. Journal of Happiness Studies 20: 1179–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, Martin E. P. 2002. Authentic Happiness. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon, Kennon M., and Sonja Lyubomirsky. 2007. Is it possible to become happier? (And if so, how?). Social and Personality Psychology Compass 1: 129–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, Michael F. 2012. Experiencing meaning in life. In The Human Quest for Meaning. Edited by Paul T. P. Wong. London: Routledge, pp. 165–84. [Google Scholar]

- Steger, Micahel F., and Patricia Frazier. 2005. Meaning in life: One link in the chain from religiousness to well-being. Journal of Counseling Psychology 52: 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, Michael F., Patricia Frazier, Shigehiro Oishi, and Matthew Kaler. 2006. The meaning in life questionnaire: Assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. Journal of Counseling Psychology 53: 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, Micahel F., Shigehiro Oishi, and Todd B. Kashdan. 2009. Meaning in life across the life span. Journal of Positive Psychology 4: 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, Michael F., Todd. B. Kashdan, Brandon A. Sullivan, and Danielle Lorentz. 2008. Understanding the search for meaning in life: Personality, cognitive style, and the dynamic between seeking and experiencing meaning. Journal of Personality 76: 199–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VIA Institute. 2003. VIA Adult Survey. Available online: viacharacter.org/surveys/takesurvey (accessed on 1 April 2023).

- VIA Institute. 2023. What the Research Says about Character Strengths. Available online: viacharacter.org/research/findings (accessed on 1 April 2023).

- Wagner, Lisa, Fabian Gander, Rene T. Proyer, and Willibald Ruch. 2019. Character strengths and PERMA: Investigating the relationships of character strengths with a multidimensional framework of well-being. Applied Research in Quality of Life 15: 307–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterman, Alan S., Seth J. Schwartz, and Regina Conti. 2008. The implications of two conceptions of happiness (hedonic enjoyment and eudaimonia) for the understanding of intrinsic motivation. Journal of Happiness Studies 9: 41–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weziak-Bialowolska, Dorota, Piotr Bialowolski, and Ryan M. Niemiec. 2023. Character strengths and health-related quality of life in a large international sample: A cross-sectional analysis. Journal of Research in Personality 103: 104338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Dexing, Zijun Xu, Zuyao Yang, Weiju Zhou, Peter Man-Hin Cheung, Eric Kam-Pui Lee, Baoliang Zhong, Xu Dong, Li Xue, Xie Yaojie, and et al. 2022. Association of meaning in life with preventive healthcare use among Chinese adults: Are there age and gender differences? BMC Public Health 22: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).