The Impact of Normalised Cross-Strait Relations on Regional Economics—An Empirical Study of Jiangsu Province

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Review and Theoretical Frameworks

2.1. International Political Relations and Their Implications for Economics: A Review

2.2. Theoretical Frameworks: Policies, Institutions and the Political Economy Signalling Model

2.3. Contextualising Cross-Strait Relations

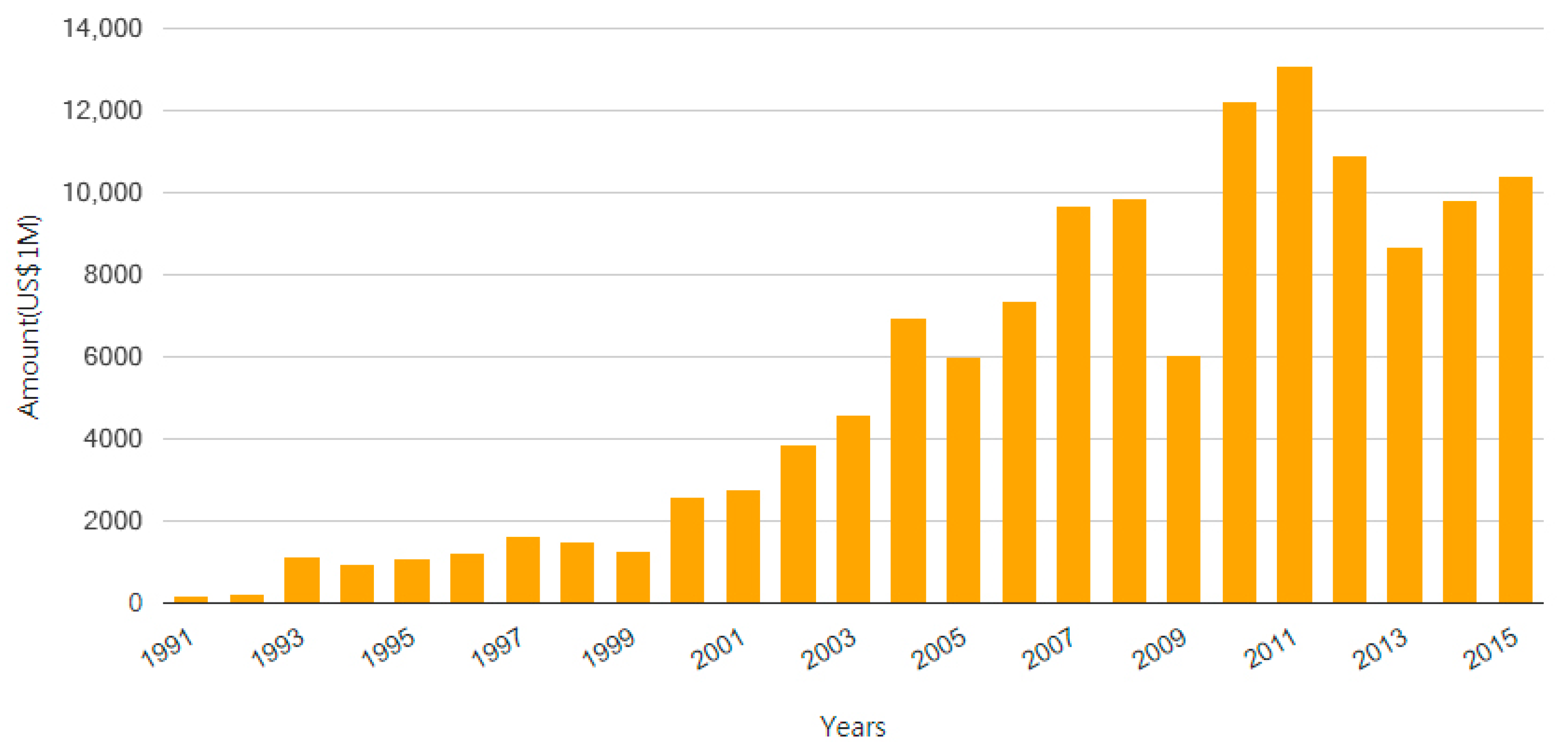

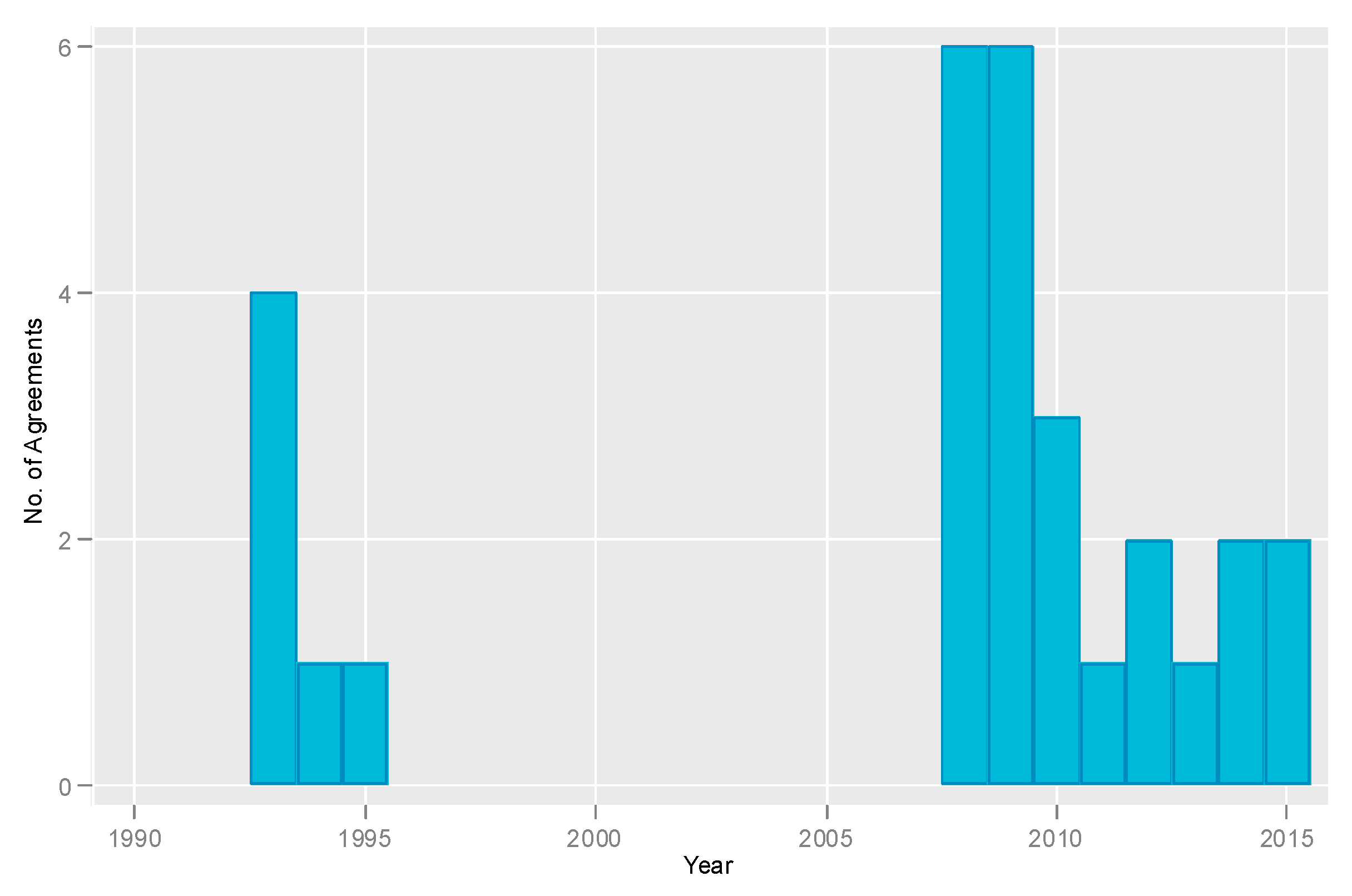

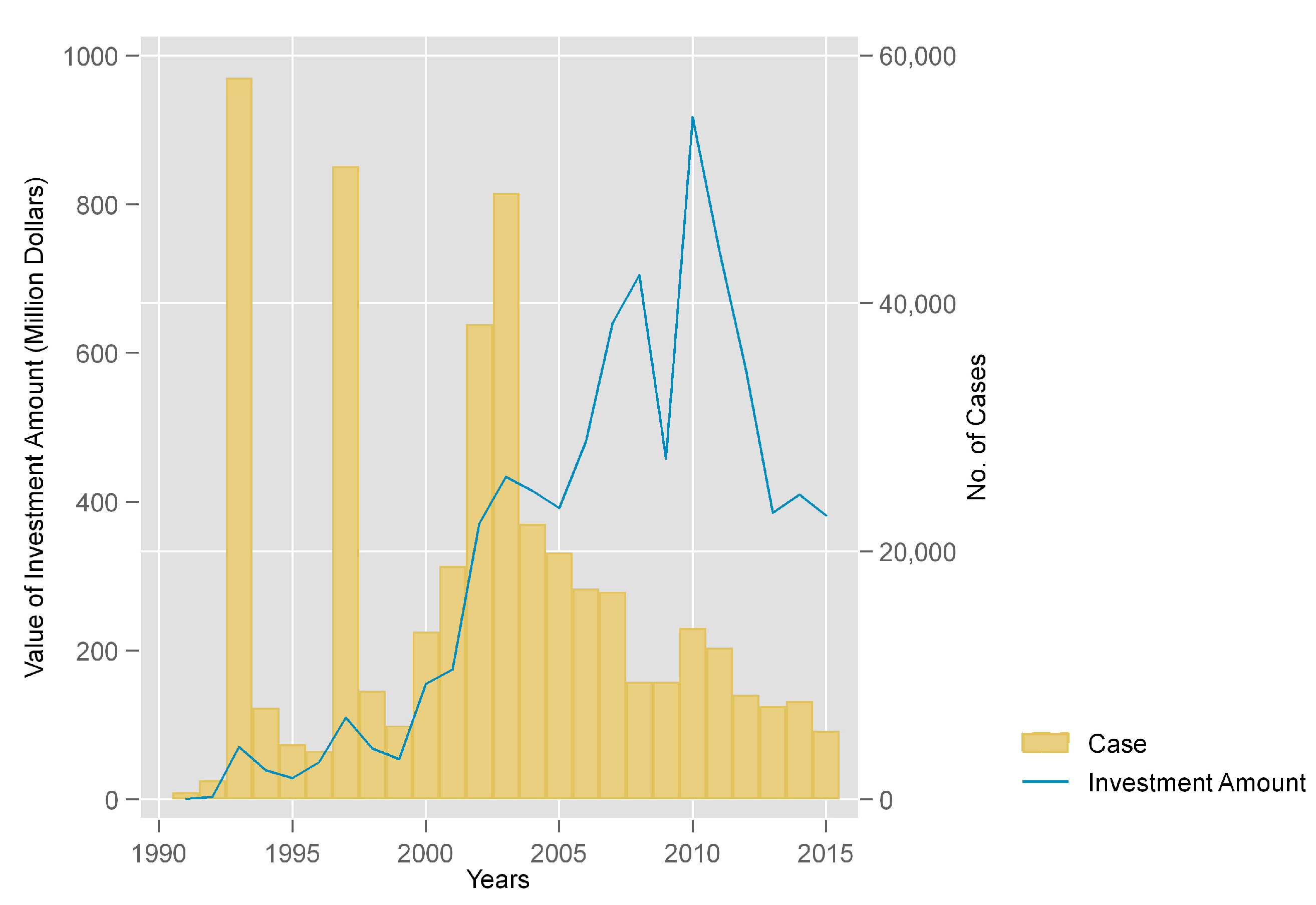

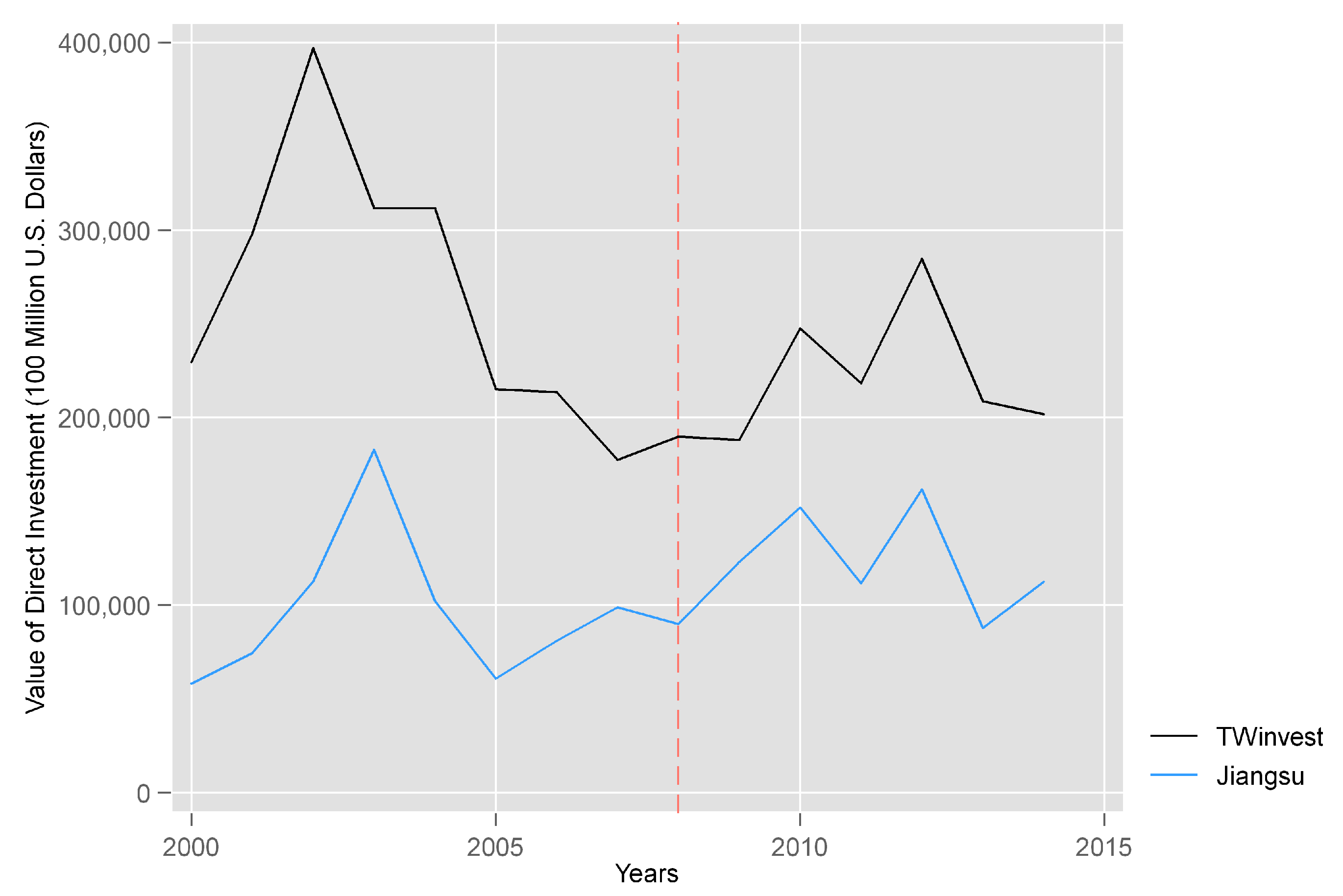

2.4. Economic Exchanges between Taiwan and Mainland China: Jiangsu Province as a Case Study

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Data Source and Introduction

3.2. Research Modelling and Hypotheses

3.3. Synthetic Control Method

3.4. Difference-in-Differences (DiD)

4. Results

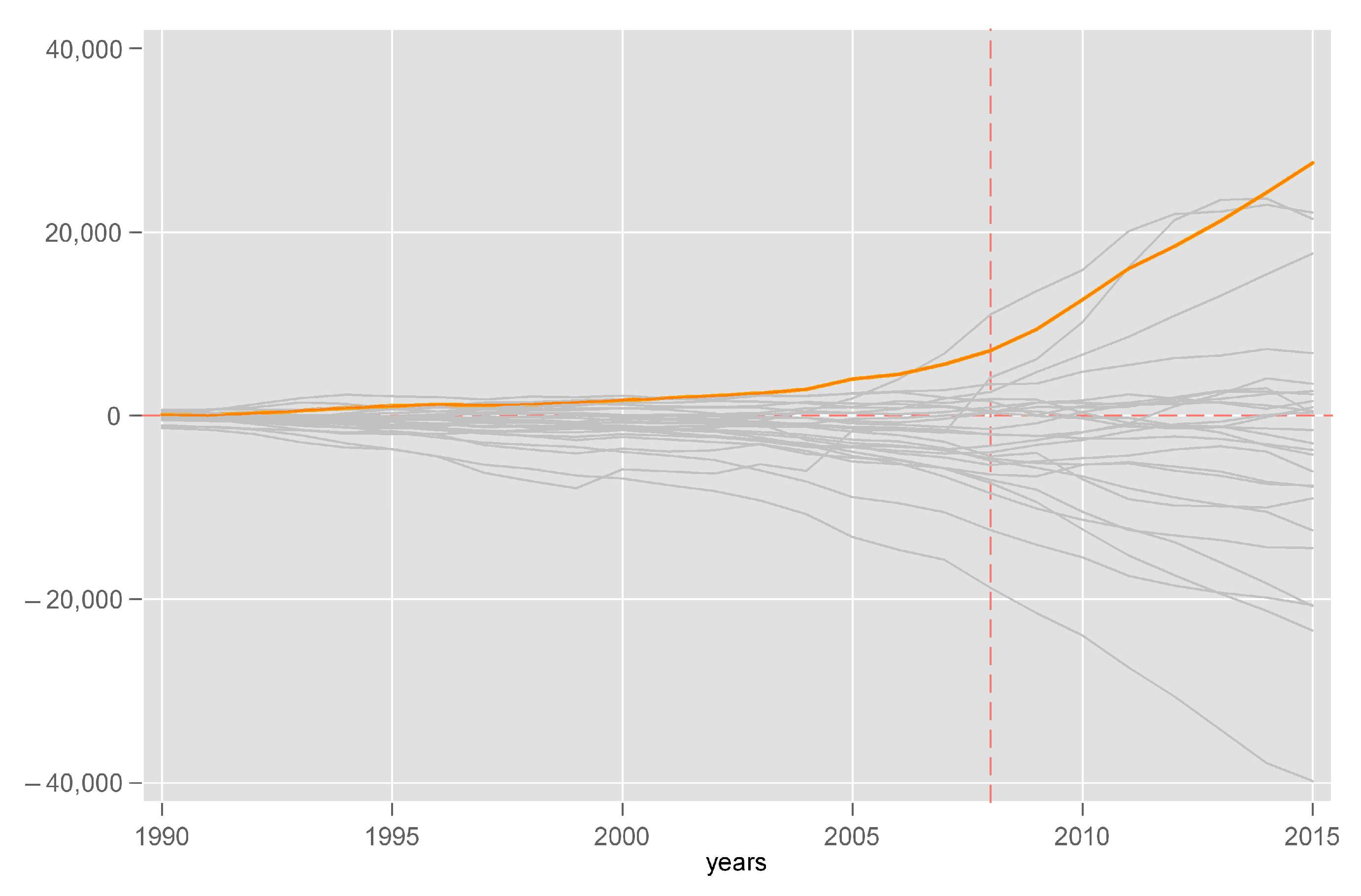

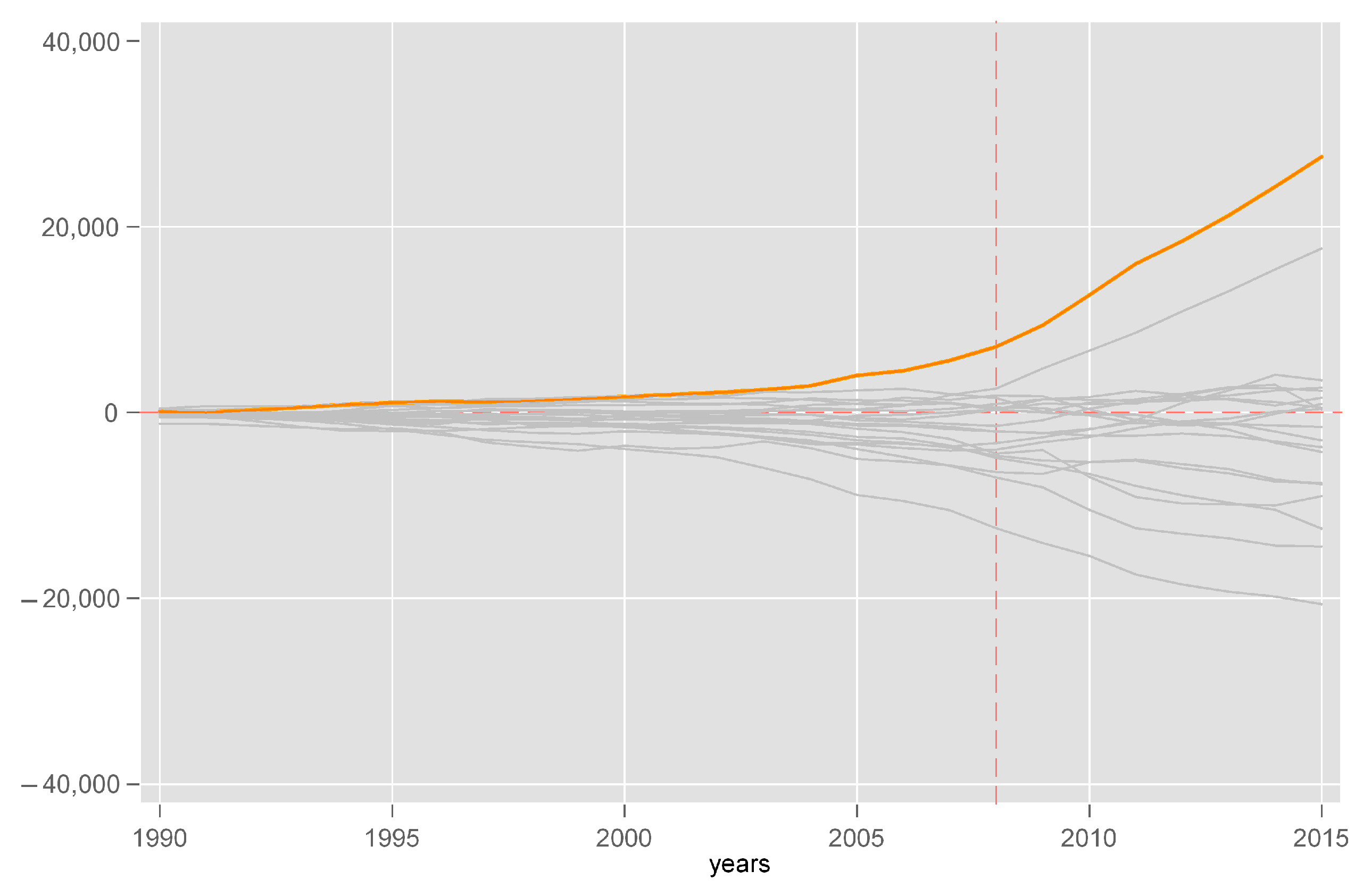

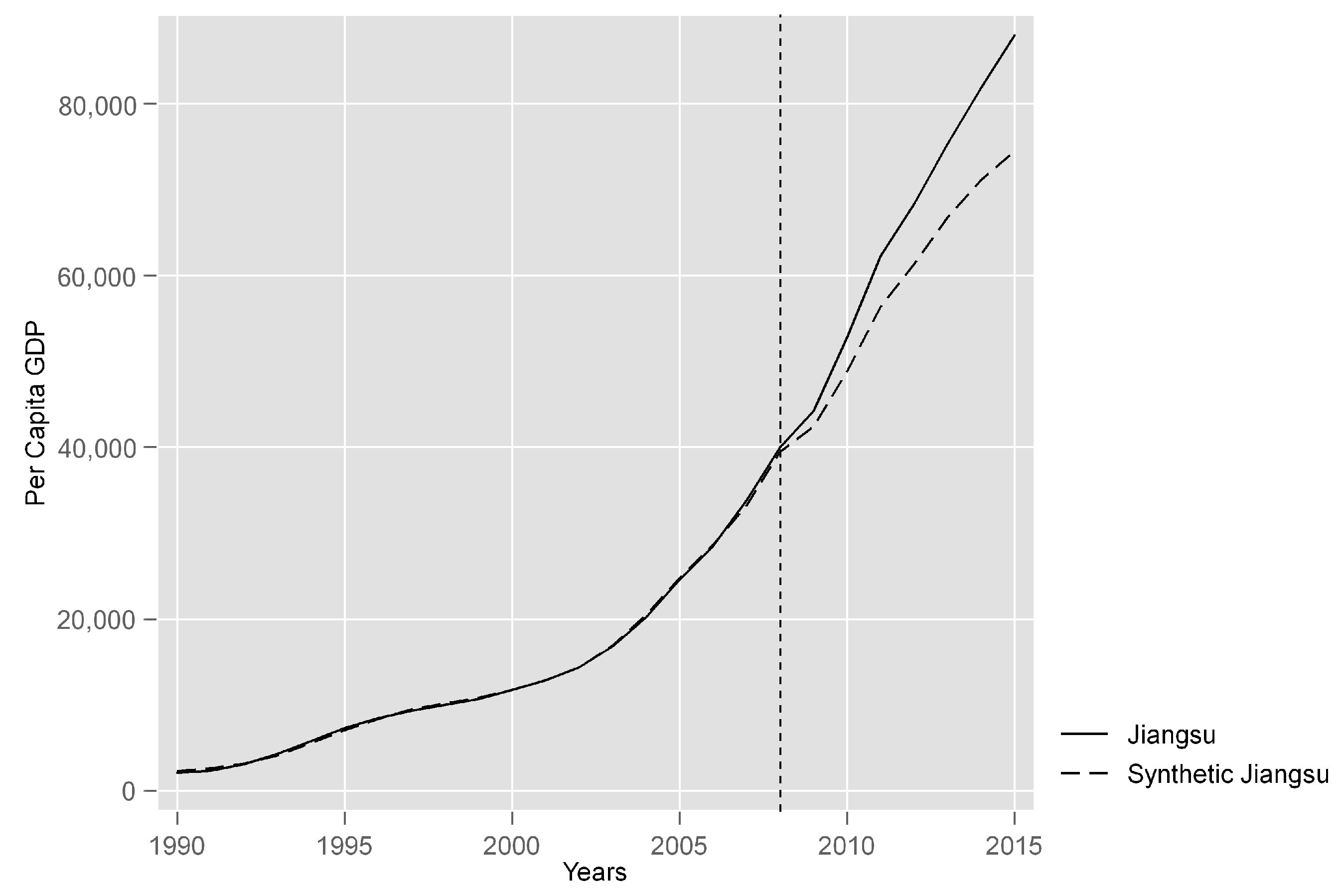

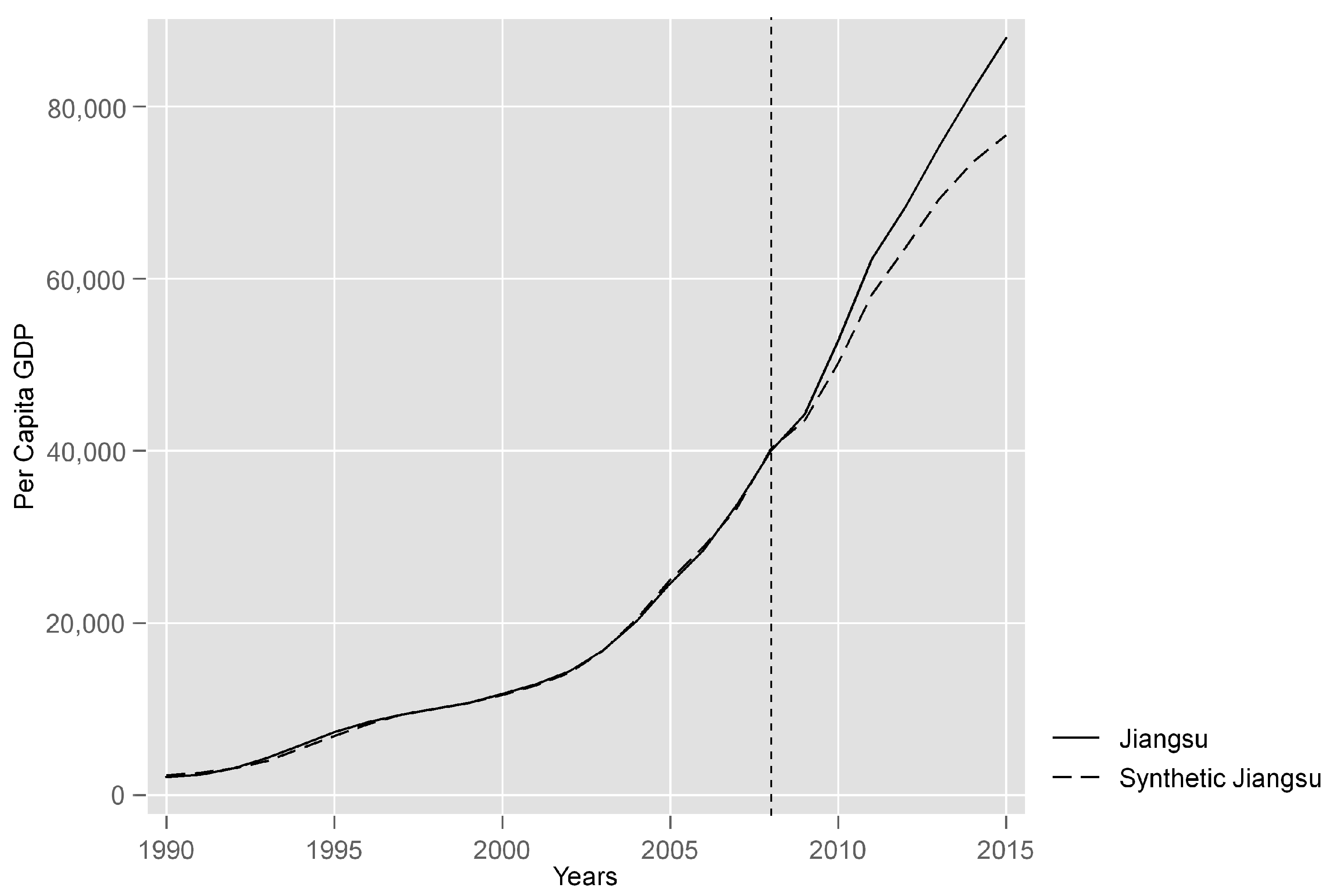

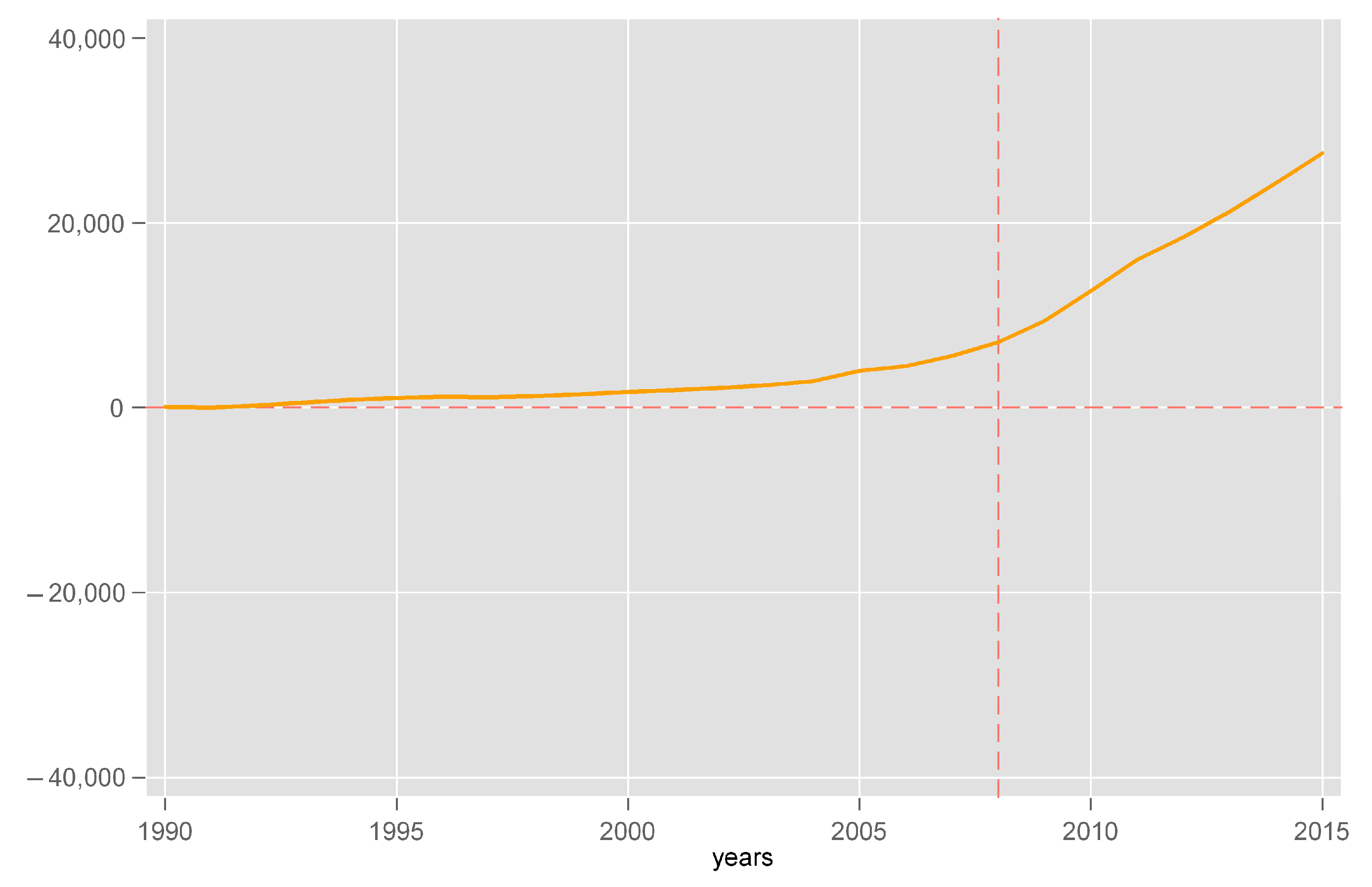

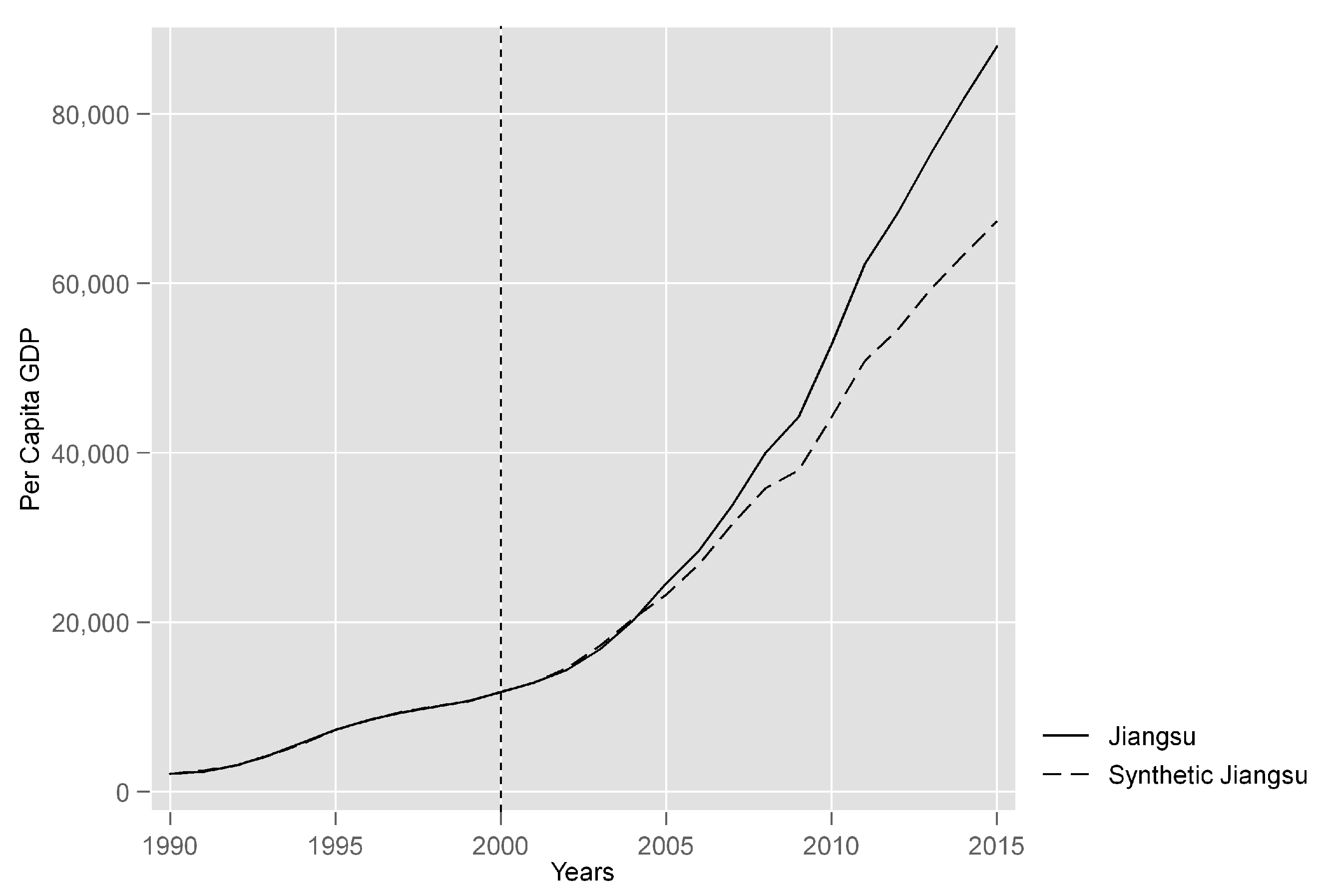

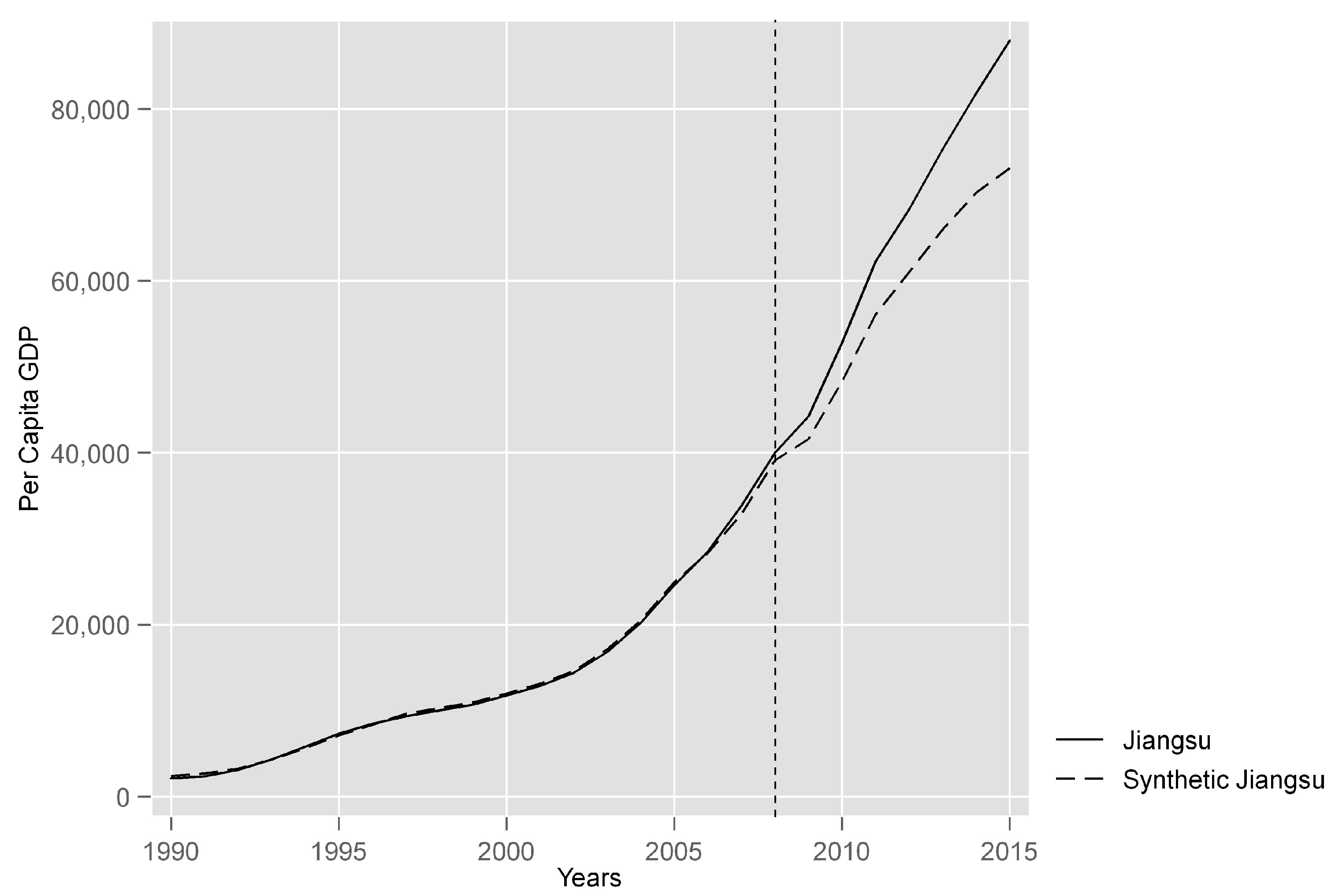

4.1. Results of the Design of Synthetic Control Methods

4.1.1. Baseline Result

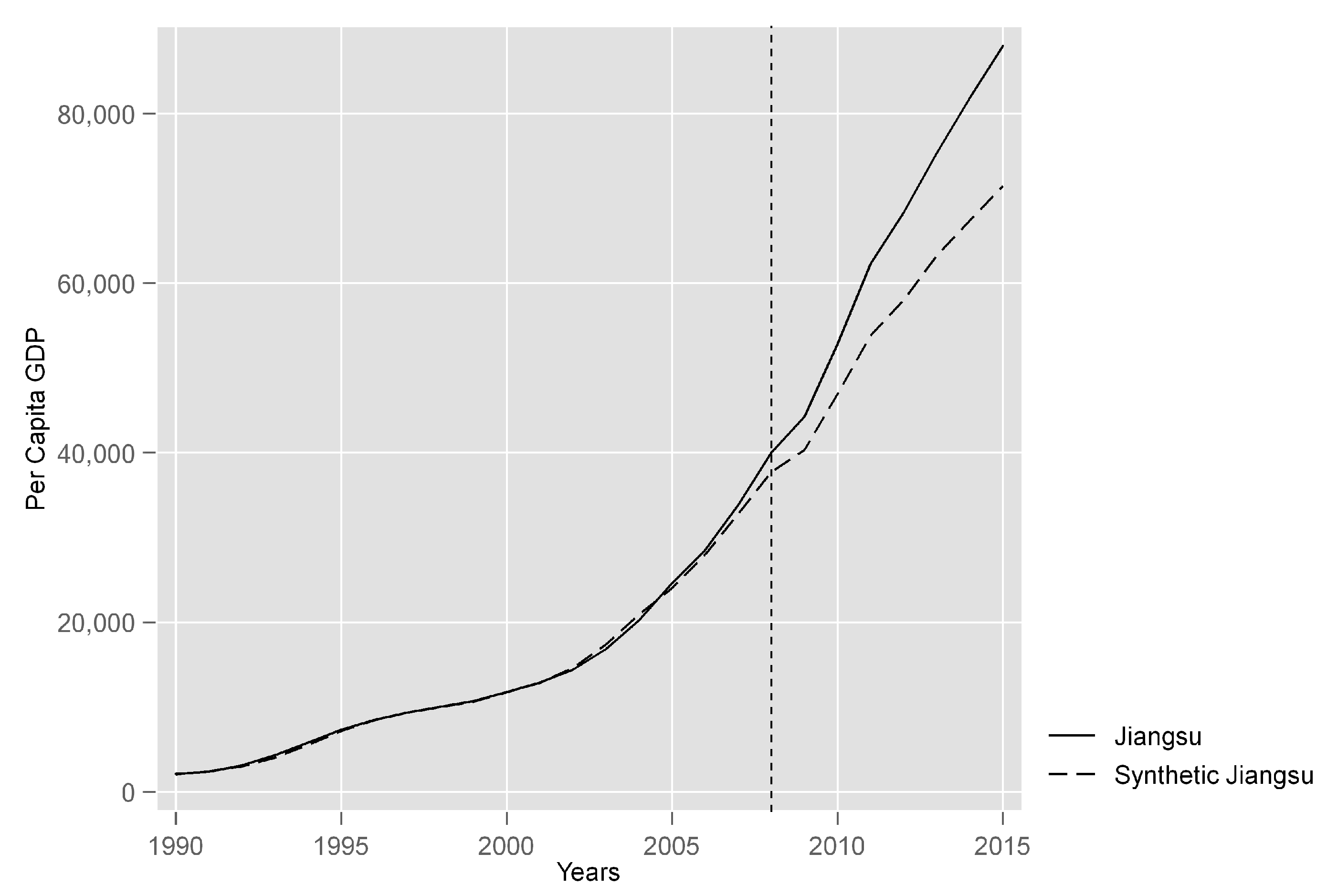

4.1.2. Spillover Effect: Other Specifications

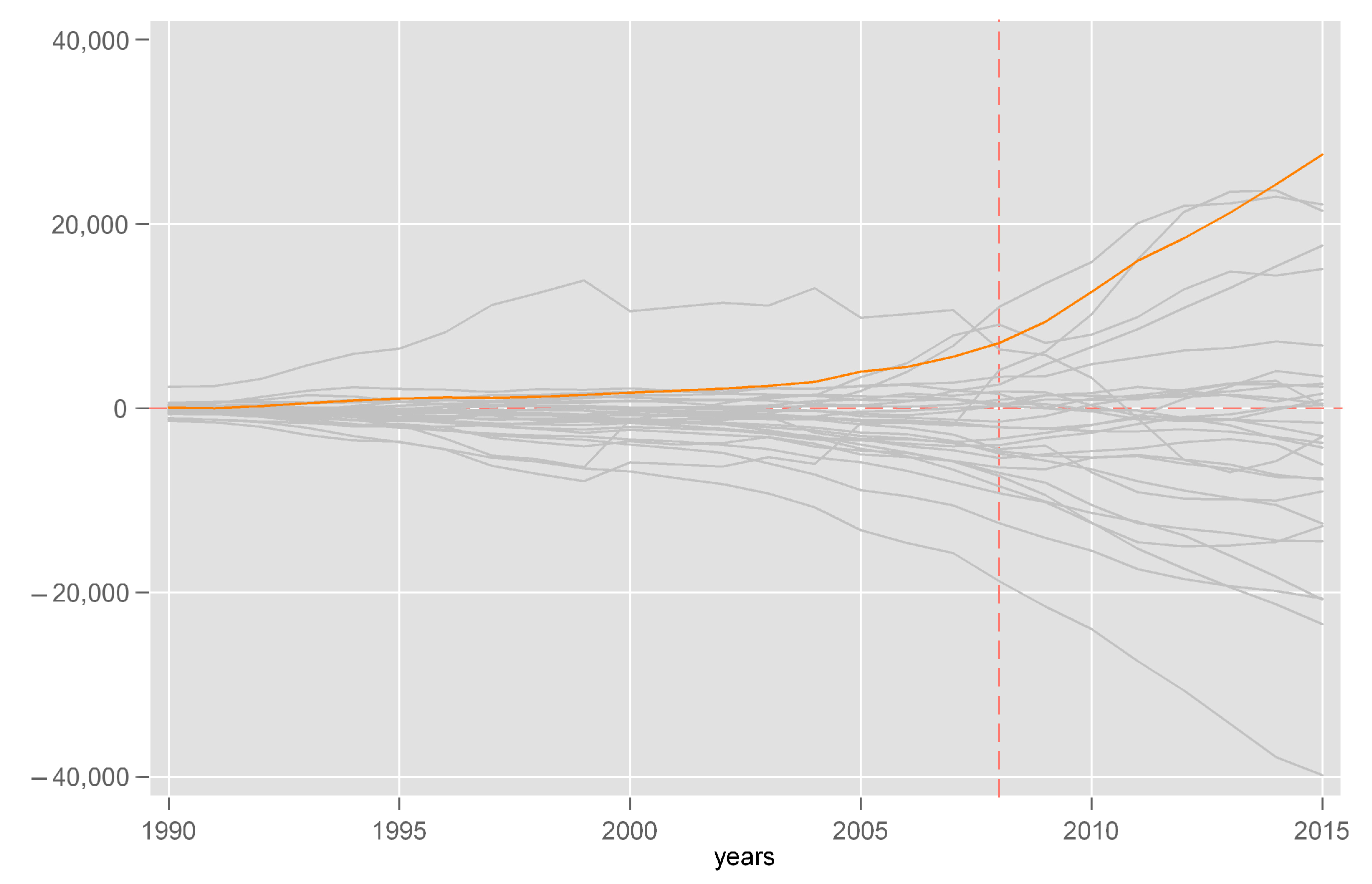

4.1.3. Placebo Test 1: Reassignment of the Treatment

4.1.4. Placebo Test 2: Normalisation of Cross-Strait Relations in 2000

4.1.5. Placebo Test 3: Shandong Province as the Treated Unit

4.1.6. Robustness Test 1: Alternative Samples in the Donor Pool

4.1.7. Robustness Test 2: Drop the Heavily Weighted Provinces

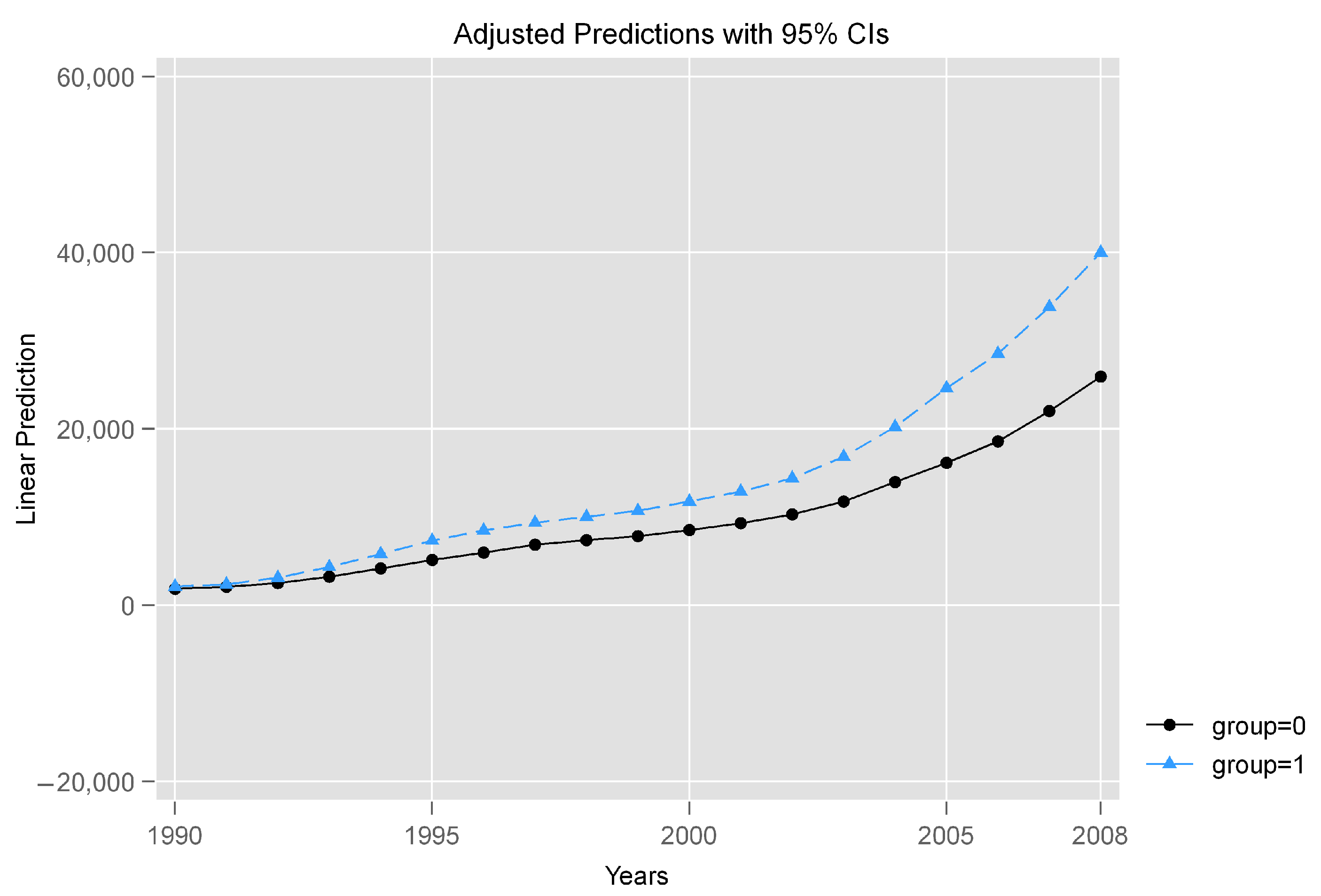

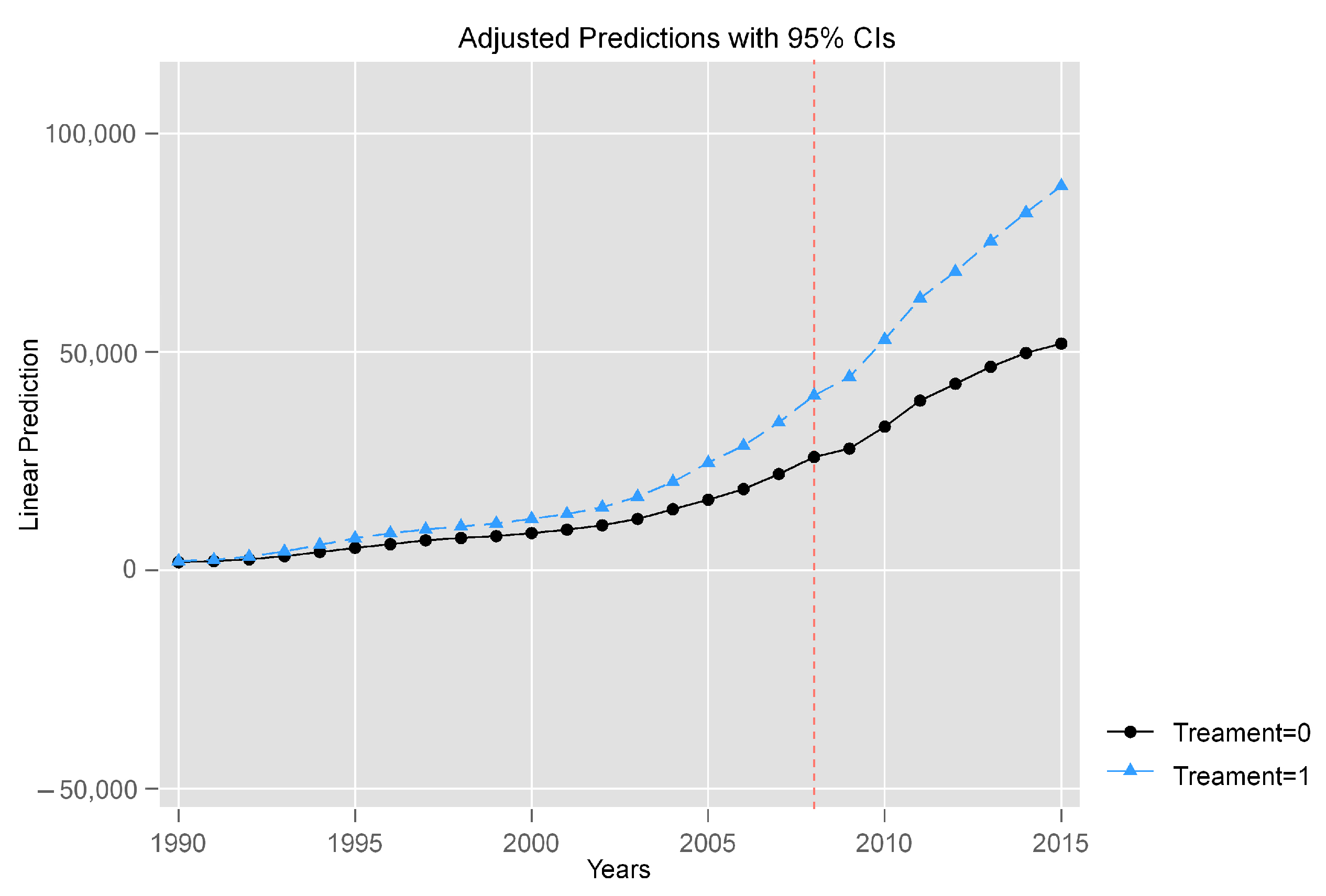

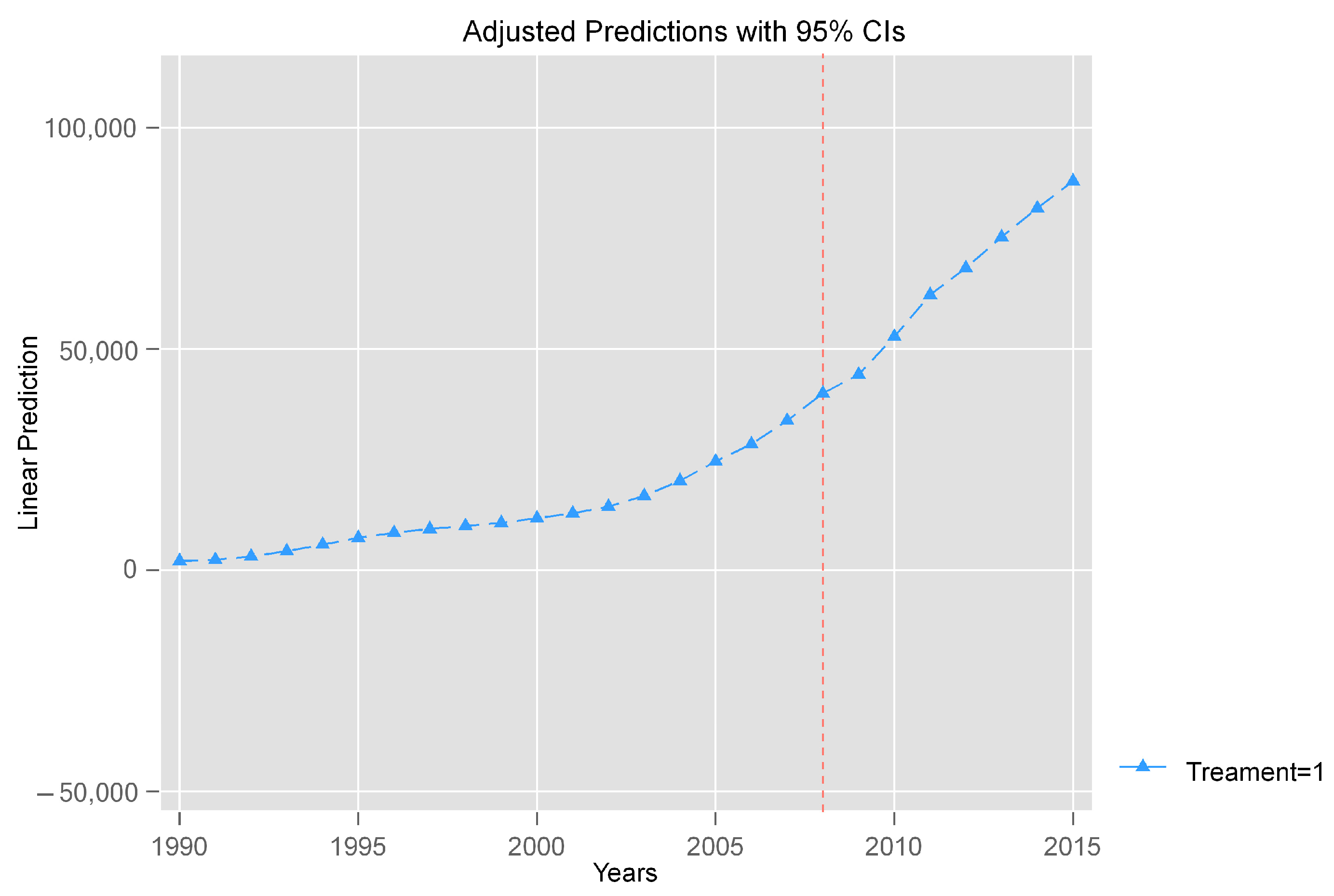

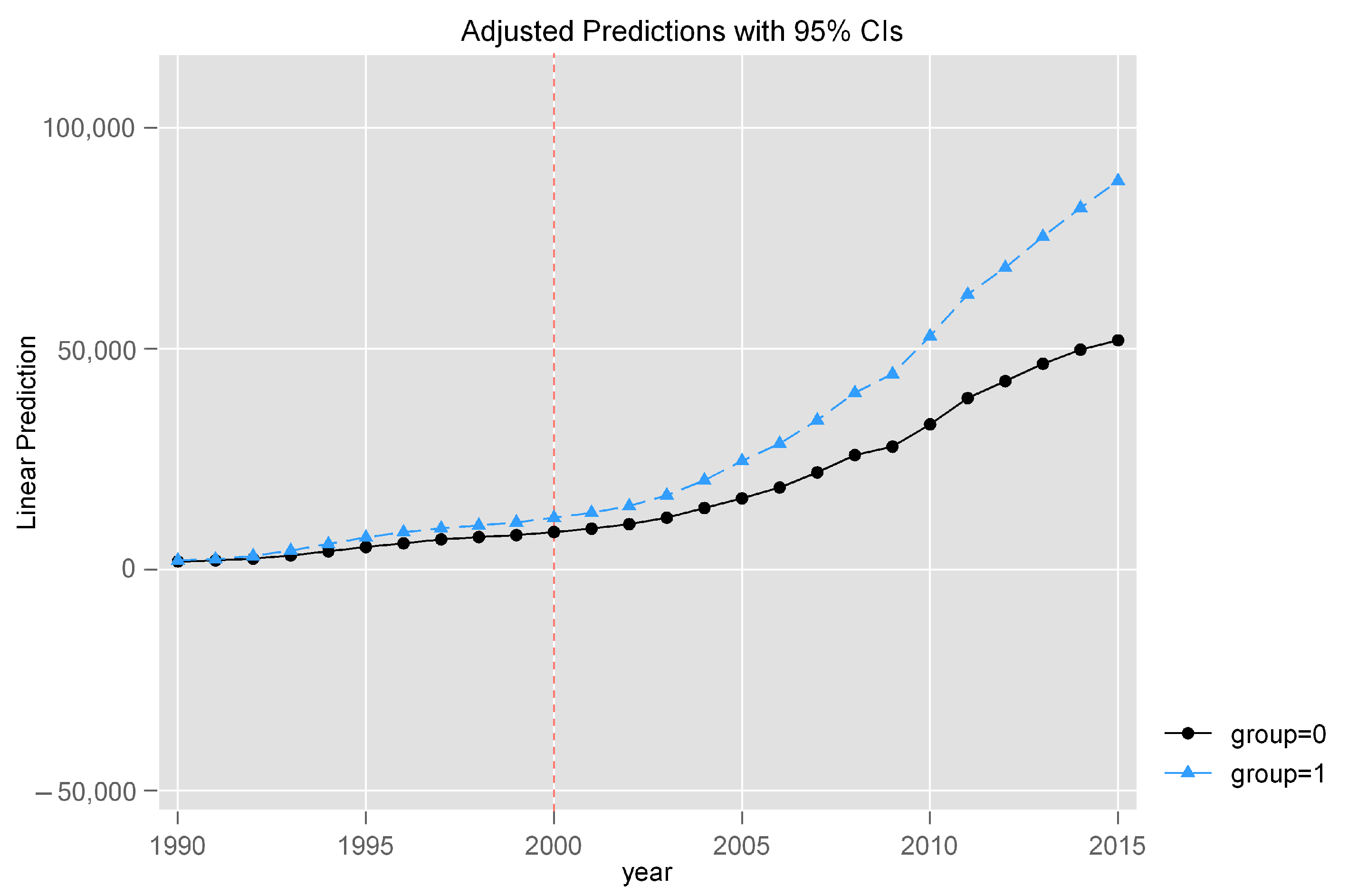

4.2. Results of Difference-in-Differences Design

4.2.1. Baseline Results

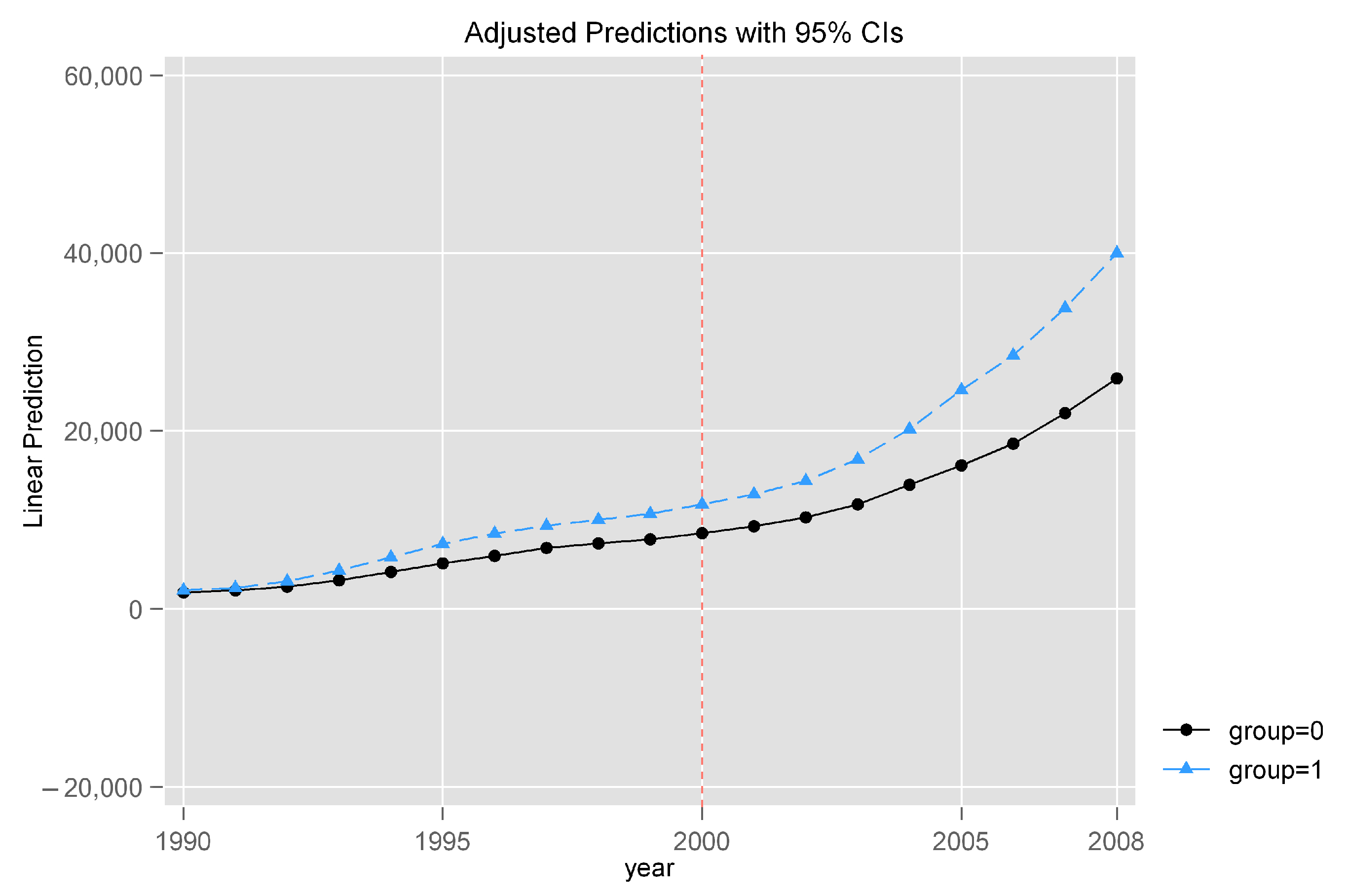

4.2.2. Robustness Test 1: Reassignment of the Treatment

4.2.3. Robustness Test 2: Spatial Placebo

4.2.4. Robustness Test 3: Alternative Samples in the Comparison Group

5. Discussion

5.1. Recollection of Theories

5.2. Empirical Implications

5.3. Limitation and Future Studies

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Stata Command

Appendix B. Table of Top 10 Investment Countries/Region of Taiwan

| Rank | Country/Region | Amount (Billion Dollars) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mainland China | 154,921.8 | 61.4 |

| 2 | British Overseas Territories | 30,017 | 11.9 |

| 3 | United States | 12,914.7 | 5.1 |

| 4 | Singapore | 10,910.9 | 4.3 |

| 5 | Vietnam | 8026.8 | 3.2 |

| 6 | Hong Kong | 5273.9 | 2.1 |

| 7 | Japan | 3812.5 | 1.5 |

| 8 | United Kingdoms | 2904.6 | 1.2 |

| 9 | Thailand | 2745.8 | 1.2 |

| 10 | Philippine | 1361.3 | 0.5 |

Appendix C. Comparative Case Study Using the Synthetic Control Method

| No. of Control Units | Weights Distribution | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 Control Units | Shandong | Tianjin | Guangdong | Zhejiang |

| 0.575 | 0.208 | 0.168 | 0.05 | |

| 3 Control Units | Shandong | Tianjin | Guangdong | |

| 0.578 | 0.22 | 0.202 | ||

| 2 Control Units | Shandong | Tianjin | ||

| 0.714 | 0.286 | |||

| 1 Control Units | Shandong | |||

| 1 | ||||

| Jiangsu | Synthetic Jiangsu | |

|---|---|---|

| PercentPrimary | 0.205 | 0.207 |

| PercentIndustry | 0.466 | 0.458 |

| PercentConstruction | 0.057 | 0.053 |

| PercentTranStoPos | 0.049 | 0.062 |

| PercentInvest | 0.433 | 0.427 |

| PerecentWholesale | 0.099 | 0.107 |

| PercentEmploymentPopu | 0.608 | 0.581 |

| ExpoImport | 2082.027 | 1377.619 |

| ln_Population | 8.913 | 8.631 |

| Jiangsu | Synthetic Jiangsu | |

|---|---|---|

| PercentPrimary | 0.205 | 0.207 |

| PercentIndustry | 0.466 | 0.459 |

| PercentConstruction | 0.056 | 0.053 |

| PercentTranStoPos | 0.049 | 0.064 |

| PercentInvest | 0.433 | 0.425 |

| PerecentWholesale | 0.099 | 0.107 |

| PercentEmploymentPopu | 0.609 | 0.576 |

| ExpoImport | 2082.027 | 1473.520 |

| ln_Population | 8.913 | 8.635 |

| Jiangsu | Synthetic Jiangsu | |

|---|---|---|

| PercentPrimary | 0.205 | 0.213 |

| PercentIndustry | 0.466 | 0.462 |

| PercentConstruction | 0.057 | 0.054 |

| PercentTranStoPos | 0.049 | 0.063 |

| PercentInvest | 0.433 | 0.443 |

| PerecentWholesale | 0.099 | 0.104 |

| PercentEmploymentPopu | 0.609 | 0.587 |

| ExpoImport | 2082.027 | 779.306 |

| ln_Population | 8.913 | 8.509 |

Appendix D. Table of Major Political Events

| Year | Event |

|---|---|

| 1991 | President Lee Teng-hui promotes Taiwan independence through legislation and independent groups |

| 1992 | Implementation of restrained trading and investment policies towards mainland China |

| 1992 | SEF and ARATS reach an agreement on the One-China Principle (92 Consensus) |

| 1993 | Wong-Gu meeting agreed on informal and cultural exchange across the Taiwan Strait |

| 1994 | Meetings arranged through SEF and ARATS are ceased due to the Qiandao Lakes Incidents |

| 1995 | President Lee Teng-hui conducts diplomatic visit to United States |

| 1995 | President Lee Teng-hui first raises the ‘Two-state theory’ |

| 1995 | The cessation of formal contact across the Taiwan Strait |

| 1996 | The mainland carries out four military inspections across the Taiwan Strait in two years |

| 1999 | The mainland conducts military exercises near the Taiwan Strait |

| 2001 | Chen Shui-bian is elected and removes the previously restrained economic policies towards mainland China |

| 2002 | President Chen Shui-bian proposes passing an independent referendum on legislation |

| 2003 | President Chen Shui-bian proposes withdrawing from the SEF and repeals previous unification principles |

| 2005 | The mainland establishes the Anti-Separatist Law to penalise actions that are in favour of Taiwanese independence |

| 2005 | Taiwan mounts “Taiwan Independence” protest |

| 2006 | President Chen Shui-bian proposes conducting independent referendum again |

| 2008 | Ma Ying-jeou is elected as president and resumes formal contact between SEFand ARATS |

| 1 | The key content of the 92 Consensus is that the One-China Principle is mutually recognised by both the Taiwanese government and the mainland government, and that it is not possible for other countries to interfere in this domestic issue across the Taiwan Strait. |

| 2 | Beijing, Shanghai and Guizhou are excluded. |

| 3 | Beijing, Tianjin, Shaanxi, Inner Mongolia, Shanghai and Guizhou are excluded. |

| 4 | Beijing, Tianjin, Shaanxi, Inner Mongolia, Liaoning, Heilongjiang, Shanghai, Guangdong, Hainan and Guizhou are excluded. |

| 5 | Eastern China covers 10 provinces and directly controlled municipalities near the coast or harbours: Beijing, Tianjin, Hubei, Shanghai, Jinagsu, Zhejiang, Fujian, Shandong, Guangdong and Hainan. |

References

- Abadie, Alberto. 2005. Semiparametric Difference-in-Differences Estimators. Review of Economic Studies 72: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abadie, Alberto, Alexis Diamond, and Jens Hainmueller. 2010. Synthetic control methods for comparative case studies: Estimating the effect of California’s tobacco control program. Journal of the American Statistical Association 105: 493–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abadie, Alberto, Alexis Diamond, and Jens Hainmueller. 2015. Comparative politics and the synthetic control method. American Journal of Political Science 59: 495–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abadie, Alberto, and Jens Gardeazabal. 2003. The economic costs of conflict: A case study of the Basque Country. American Economic Review 93: 113–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdella, Ahmed Berhan, Naghavi Navaz, and Fah Benjamin Chan Yin. 2018. The effect of corruption, trade openness and political stability on foreign direct investment: Empirical evidence from BRIC countries. International Journal of Advanced and Applied Sciences 5: 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, Daron, Simon Johnson, Amir Kermani, James Kwak, and Todd Mitton. 2013. The Value of Connections in Turbulent Times: Evidence from the United States. National Bureau of Economic Research 121: 368–391. [Google Scholar]

- Aisen, Ari, and Francisco Jose Veiga. 2013. How does political instability affect economic growth? European Journal of Political Economy 29: 151–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angrist, Joshu, and Jörn-Steffen Pischke. 2009. Mostly Harmless Econometrics: An Empiricist’s Companion. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baier, Scott, Jeffrey Bergstrand, and Michael Feng. 2014. Economic integration agreements and the margins of international trade. Journal of International Economics 93: 339–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balliet, Daniel, Joshua Tybur, Junhui Wu, Christian Antonellis, and Paul Van Lange. 2018. Political Ideology, Trust, and Cooperation: In-group Favoritism among Republicans and Democrats during a US National Election. The Journal of Conflict Resolution 62: 797–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, Katherine. 2003. Models and Measures in Trade-Conflict Research. In Economic Interdependence and International Conflict: New Perspectives on an Enduring Debate. Edited by Edward D. Mansfield and Brian M. Pollins. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, pp. 207–21. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, Thorsten, George Clarke, Alberto Groff, Philip Keefer, and Patrick Walsh. 2001. New tools in comparative political economy: The database of political institutions. The World Bank Economic Review 15: 165–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beine, Michel, and Serge Coulombe. 2007. Economic integration and the diversification of regional exports: Evidence from the Canadian–US Free Trade Agreement. Journal of Economic Geography 7: 93–111. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, Daniel, William Easterly, Nathan Nunn, and Shanker Satyanath. 2013. Commercial imperialism? Political influence and trade during the Cold War. American Economic Review 103: 863–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolt, Paul J. 2001. Economic Ties Across the Taiwan Strait: Buying Time for Compromise. Issues and Studies 37: 80–105. [Google Scholar]

- Brzezinski, Zbigniew, and John J. Mearsheimer. 2005. Debate: Clash of the Titans. Foreign Policy 146: 46–50. [Google Scholar]

- Busse, Matthias, and Carsten Hefeker. 2007. Political risk, institutions and foreign direct investment. European Journal of Political Economy 23: 397–415. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Kelvin G. 2011. Cross-Taiwan Straits Relations Since 1979 Policy Adjustment and Institutional Change across the Straits, Singapore. Hackensack: World Scientific. [Google Scholar]

- Chase, Michael, Kevin Pollpeter, and James Mulvenon. 2004. Shanghaied? The Economic and Political Implication of the Flow of Information Technology and Investment across the Taiwan Strait. Technical Report 133. Santa Monica: RAND Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Dean P. 2013. The Strategic Implications of Ma Ying-jeou’s “One ROC, Two Areas” Policy on Cross-Strait Relations. American Journal of Chinese Studies 20: 23–41. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Xiangming. 2018. Globalisation redux: Can China’s inside-out strategy catalyse economic development and integration across its Asian borderlands and beyond? Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 11: 35–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Xin. 2014. On the Interactive Route and Pattern of the Cross-Strait Economic and Political Relations. Journal of Beijing Union University (Humanities and Social Sciences) 12: 48–53. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, Gordon C. K. 2007. China Factors: Political Perspectives and Economic Interactions. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, Lee-in Chen. 2016. The pattern and impact of Taiwan’s investment in mainland China. In Emerging Patterns of East Asian Investment in China: From Korea, Taiwan and Hong Kong. London: Routledge, pp. 143–65. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, Yun-Han. 1997. The Political Economy of Taiwan’s Mainland Policy. Journal of Contemporary China 6: 229–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, P. 2008. Does Growing Economic Interdependence Reduce the Potential for Conflict in the China-Taiwan-U.S. Triangle? American Journal of Chinese Studies 15: 57–68. [Google Scholar]

- Conable, Barber B., Jr., and David M. Lampton. 1993. China: The coming power. Foreign Affairs 72: 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrado, Germana. 2020. Institutional quality and access to financial services: Evidence from European transition economies. Journal of Economic Studies 47: 1363–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, Patricia A. 1999. The Art of Economic Persuasion: Positive Incentives and German Economic Diplomacy. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dent, Christopher. 2005. Taiwan and the New Regional Political Economy of East Asia. The China Quarterly 182: 385–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dittmer, Lowell. 2017. Taiwan and China: Fitful Embrace. California: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ekanayake, E. M., A. Mukherjee, and B. Veeramacheneni. 2010. Trade blocks and the gravity model: A study of economic integration among Asian developing countries. Journal of Economic Integration 25: 627–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, R. 2006. The political economy of sanctions against North Korea. Asian Perspective 30: 5–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, Alexander L., and Andrew F. Bennett. 2004. Case Studies and Theory Development in the Social Sciences. Singapore: MIT. [Google Scholar]

- Gören, Erkan. 2014. How ethnic diversity affects economic growth. World Development 59: 275–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowa, Joanne, and Raymond Hicks. 2017. Commerce and Conflict: New Data about the Great War. British Journal of Political Science 47: 653–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C. Michael. 2005. Territorial economic integration and globalisation. In Tourism in the Age of Globalisation. London: Routledge, pp. 36–58. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Baran. 2021. Secondary sanctions mechanism revisited: The case of US sanctions against North Korea. In Research Handbook on Economic Sanctions. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 223–237. [Google Scholar]

- Harding, Harry. 1993. The Concept of “Greater China”: Themes, Variations and Reservations. The China Quarterly 136: 660–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, Jeffrey A., and Joan Edelman Spero. 2013. The Politics of International Economic Relations. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan, M. Aynul. 1999. Conceptual framework for growth triangles. (International Trade)(Report). Pakistan Development Review 38: 805–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayakawa, Kazunobu, Fukunari Kimura, and Hyun-Hoon Lee. 2013. How does country risk matter for foreign direct investment? The Developing Economies 51: 60–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, Uk, and Wondeuk Cho. 2012. The Economic Cooperation Framework Agreement between China and Taiwan and Its Implications for South Korea. Pacific Focus 27: 205–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Tsai-Lung, and Chih-Hai Yang. 2011. The economic cooperation framework agreement between China and Taiwan: Understanding its economics and politics. Asian Economic Papers 10: 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, Tzu-Chieh. 2017. Rethinking Public Diplomacy: A Study of China Exerting its Influence on Taiwan. Doctoral dissertation, Waseda University, Tokyo, Japan. [Google Scholar]

- Imai, Kosuke. 2017. Quantitative Social Science. An Introduction. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, Bora, and Hoon Lee. 2021. US–China commercial rivalry, great war and middle powers. International Area Studies Review 24: 135–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jong-A-Pin, R. 2009. On the measurement of political instability and its impact on economic growth. European Journal of Political Economy 25: 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastner, Scott. 2007. When Do Conflicting Political Relations Affect International Trade? Journal of Conflict Resolution 51: 664–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshk, Omar M. G., Brian M. Pollins, and Rafael Reuveny. 2004. Trade still follows the flag: The primacy of politics in a simultaneous model of interdependence and armed conflict. Journal of Politics 66: 1155–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Hyung Min, and David L. Rousseau. 2005. The classical liberals were half right (or half wrong): New tests of the “liberal peace,” 1960–88. Journal of Peace Research 42: 523–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, Min Gyo. 2009. The Senkaku/Diaoyu dispute and Sino-Japanese political-economic relations: Cold politics and hot economics? The Pacific Review 22: 205–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, Tse-Kang. 2017. Cross-Strait Economic Relations and China’s Rise: The Case of the IT Sector. In Taiwan and China: Fitful Embrace. Edited by L. Dittmer. Oakland: University of California Press, pp. 151–75. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Yuhua, Ze Jian, Wei Tian, and Laixun Zhao. 2021. How political conflicts distort bilateral trade: Firm-level evidence from China. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 183: 233–49. [Google Scholar]

- Libman, Alexander, and Evgeny Vinokurov. 2012. Regional integration and economic convergence in the Post-Soviet space: Experience of the decade of growth. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 50: 112–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lijphart, Arend. 1971. Comparative Politics and the Comparative Method. The American Political Science Review 65: 682–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Justin Yifu, Xifang Sun, and Ye Jiang. 2013. Endowment, industrial structure, and appropriate financial structure: A new structural economics perspective. Journal of Economic Policy Reform 16: 109–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Weidong, and Michael Dunford. 2016. Inclusive globalization: Unpacking China’s belt and road initiative. Area Development and Policy 1: 323–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Andrew G. 2003. Does trade follow peace? Post-war bilateral trade and expectations for recurrent conflict. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association, Philadelphia, PA, USA, August 28–31. [Google Scholar]

- Lupo Pasini, F. 2013. Economic stability and economic governance in the Euro Area: What the European Crisis can teach on the limits of Economic integration. Journal of International Economic Law 16: 211–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamoon, Dawood, and S. Mansoob Murshed. 2010. The conflict mitigating effects of trade in the India-Pakistan case. Economics of Governance 11: 145–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansfield, Edward D., Jon C. Pevehouse, and David. H. Bearce. 2014. Preferential trading arrangements and military disputes. In Power and the Purse. London: Routledge, pp. 92–118. [Google Scholar]

- Mattoo, Aaditya, Randeep Rathindran, and Arvind Subramanian. 2001. Measuring Services Trade Liberalization and Its Impact on Economic Growth: An Illustration. Washington, DC: World Bank Publications, vol. 2655. [Google Scholar]

- Najafi, Amir, and Hossein Askari. 2012. The Impact of Political Relations Between Countries on Economic Relations. PSL Quarterly Review 65: 247–73. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill, Stephen, Noémi Kreif, Richard Grieve, Matthew Sutton, and Jasjeet S. Sekhon. 2016. Estimating causal effects: Considering three alternatives to difference-in-differences estimation. Health Services and Outcomes Research Methodology 16: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obadić, Ivan. 2017. In Pursuit of Stability: Yugoslavia and Western European Economic Integration, 1948–1970. Doctoral dissertation, European University Institute, Fiesole, Italy. [Google Scholar]

- Pasara, Michael Takudzwa. 2020. An overview of the obstacles to the African economic integration process in view of the African continental free trade area. Africa Review 12: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccolino, Giulia. 2020. Regional integration. In The Routledge Handbook of EU-Africa Relations. London: Routledge, pp. 188–201. [Google Scholar]

- Pietrangeli, Giulia. 2016. Supporting regional integration and cooperation worldwide: An overview of the European Union approach. In The EU and World Regionalism. London: Routledge, pp. 9–43. [Google Scholar]

- Rashid, Mamunur, Xuan Hui Looi, and Shao Jye Wong. 2017. Political stability and FDI in the most competitive Asia Pacific countries. Journal of Financial Economic Policy 9: 140–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, Andrew M., James F. Burgess Jr., and Justin B. Dimick. 2015. Why We Should Not Be Indifferent to Specification Choices for Difference-in-Differences. Health Services Research 50: 1211–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabir, Samina, and Ahsan Khan. 2018. Impact of political stability and human capital on foreign direct investment in East Asia & Pacific and south Asian countries. Asian Journal of Economic Modelling 6: 245–56. [Google Scholar]

- Shambaugh, David. 2008. International Relations of Asia. Lanham: Rowan and Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Shee, Poon Kim. 2004. The political economy of Mahathir’s China policy: Economic cooperation, political and strategic ambivalence. Ritsumeikan Annual Review of International Studies 3: 59–79. [Google Scholar]

- Simmons, Beth A. 2005. Rules over real estate: Trade, territorial conflict, and international borders as an institution. Journal of Conflict Resolution 49: 823–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, Scott. 2009. China’s Rise and the Two Koreas: Politics, Economics, Security. Boulder: Lynne Rienner. [Google Scholar]

- Sutter, Karen M. 2002. Business Dynamism across the Taiwan Strait: The Implications for Cross-Strait Relations. Asian Survey 42: 522–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swank, Duane. 2002. Global Capital, Political Institutions, and Policy Change in Developed Welfare States. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tavares, Rodrigo, and Vanessa Tang. 2016. Regional Economic Integration in Africa: Impediments to Progress? In Comparative Regionalisms for Development in the 21st Century. London: Routledge, pp. 209–32. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, Chung-min. 2017. The Nature and Trend of Taiwanese Investment in China (1991–2014): Business Orientation, Profit Seeking, and Depoliticization. In Taiwan and China: Fitful Embrace. Edited by Lowell Dittmer. Oakland: University of California Press, pp. 133–50. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, Tung-Chieh, and Tongy Tai-ting Liu. 2017. Cross-Strait Relations and Regional Integration: A Review of the Ma Ying-jeou Era (2008–2016). Journal of Current Chinese Affairs 46: 11–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, Hans H., and Yun-Han Chu. 2015. Signalling peace: A theory of the ECFA and a peace dividend beyond the Taiwan Strait. In Taiwan and the ‘China Impact’. London: Routledge, pp. 128–47. [Google Scholar]

- Yahuda, Michael. 2012. The International Politics of the Asia Pacific. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Chyan, and Shiu-Wan Hung. 2003. Taiwan’s dilemma across the Strait: Lifting the ban on semiconductor investment in China. Asian Survey 43: 681–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Yung-Lieh, Tsui-Yueh Cho, and Ming-Hsiang Huang. 2017. Impacts of the economic cooperation framework agreement on banking cost efficiency in China and Taiwan a stochastic metafrontier approach. Hitotsubashi Journal of Economics 58: 121–41. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Jingwen, and Chunchao Wong. 2011. Political Environment and Economic Development: Analysis Based on the Evolution of Cross-Strait Relations. South China Economics 4: 31–39. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Baohui. 2011. Taiwan’s New Grand Strategy. Journal of Contemporary China 20: 269–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Jiangsu | Synthetic Jiangsu | Average of Comparison Provinces | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PercentPrimary | 0.205 | 0.207 | 0.279 |

| PercentIndustry | 0.466 | 0.458 | 0.371 |

| PercentConstruction | 0.057 | 0.053 | 0.068 |

| PercentTranStoPos | 0.049 | 0.063 | 0.065 |

| PercentInvest | 0.433 | 0.427 | 0.492 |

| PerecentWholesale | 0.099 | 0.107 | 0.094 |

| PercentEmploymentPopu | 0.609 | 0.581 | 0.530 |

| ExpoImport | 2082.027 | 1377.619 | 440.695 |

| ln_Population | 8.913 | 8.631 | 7.998 |

| Province | Synthetic Control Weights | Province | Synthetic Control Weights |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beijing | 0 | Henan | 0 |

| Tianjin | 0.208 | Hubei | 0 |

| Hebei | 0 | Hunan | 0 |

| Shananxi | 0 | Guangdong | 0.167 |

| Inner Mongolia | 0 | Guangxi | 0 |

| Liaoning | 0 | Hainan | 0 |

| Jilin | 0 | Sichuan | 0 |

| Heilongjiang | 0 | Guizhou | 0 |

| Shanghai | 0 | Yunnan | 0 |

| Zhejiang | 0.05 | Xizang | 0 |

| Anhui | 0 | Shanxi | 0 |

| Fujian | 0 | Gansu | 0 |

| Jiangxi | 0 | Qinghai | 0 |

| Shandong | 0.575 | Ningxia | 0 |

| Xinjiang | 0 |

| Jiangsu | Synthetic Jiangsu | |

|---|---|---|

| PercentPrimary | 0.205 | 0.221 |

| PercentIndustry | 0.466 | 0.443 |

| PercentConstruction | 0.057 | 0.055 |

| PercentTranStoPos | 0.049 | 0.061 |

| PercentInvest | 0.433 | 0.439 |

| PerecentWholesale | 0.099 | 0.106 |

| PercentEmploymentPopu | 0.609 | 0.591 |

| ExpoImport | 2082.027 | 887.309 |

| ln_Population | 8.913 | 8.651 |

| Per Capita GDP | Coef. | p > |t| | [95% Conf. Interval] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | 3843.73 (3019.27) | 0.2 | −2083.18 | 9770.65 |

| Treatment | 13,814.79 (1638.51) | 0 | 10,598.35 | 17,031.24 |

| Diff-in-diff | 20,726.52 (5443.07) | 0 | 10,041.61 | 31,411.42 |

| Year | 1306.89 (100.21) | 0 | 1110.17 | 1503.61 |

| Constant | −2,603,081 (200,273.20) | 0 | −2,996,223 | −2,209,939 |

| Adj R-squared | 0.6104 | |||

| R-squared | 0.6101 | |||

| N | 780 | |||

| F (4, 565) | 310.05 | |||

| Per Capita GDP | Coef. | p > |t| | [95% Conf. Interval] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | 1664.10 (2534.69) | 0.512 | −3314.46 | 6642.65 |

| Treatment | 2420.75 (1327.86) | 0.069 | −5028.89 | 187.39 |

| Diff-in-diff | 5739.87 (3682.81) | 0.12 | −1493.81 | 12,973.54 |

| Year | 1357.05 (120.53) | 0 | 1120.31 | 1593.78 |

| Constant | −2,701,936 (240,397) | 0 | −3,174,117 | −2,229,755 |

| Adj R-squared | 0.4073 | |||

| R-squared | 0.4115 | |||

| N | 570 | |||

| F (4, 565) | 98.75 | |||

| Per Capita GDP | Coef. | p > |t| | [95% Conf. Interval] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | 1343.37 (3462.76) | 0.698 | 5463.56 | 8150.30 |

| Treatment | 14,656.94 (2548.52) | 0 | 9647.17 | 19,666.70 |

| Diff-in-diff | 15,737.62 (6242.58) | 0.012 | 3466.25 | 28,008.90 |

| Year | 1625.875 (154.98) | 0 | 1321.22 | 1930.53 |

| Constant | −3,238,065 (309,735.50) | 0 | −3,846,928 | −2,629,201 |

| Adj R-squared | 0.6309 | |||

| R-squared | 0.6345 | |||

| N | 416 | |||

| F (4, 565) | 178.34 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, Y. The Impact of Normalised Cross-Strait Relations on Regional Economics—An Empirical Study of Jiangsu Province. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 493. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12090493

Li Y. The Impact of Normalised Cross-Strait Relations on Regional Economics—An Empirical Study of Jiangsu Province. Social Sciences. 2023; 12(9):493. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12090493

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Yunyan. 2023. "The Impact of Normalised Cross-Strait Relations on Regional Economics—An Empirical Study of Jiangsu Province" Social Sciences 12, no. 9: 493. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12090493

APA StyleLi, Y. (2023). The Impact of Normalised Cross-Strait Relations on Regional Economics—An Empirical Study of Jiangsu Province. Social Sciences, 12(9), 493. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12090493