Are Schools Learning Organizations? An Empirical Study in Spain, Bulgaria, Italy, and Turkey

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Leadership Styles in Education

1.2. Schools as Learning Organizations

- -

- Shared Vision: members share an image of what the organization wishes to achieve. Leaders of a learning organization will establish goals shared by all members of the community.

- -

- Personal Mastery: constant personal commitment to learning, excellence, and the vision of the organization. Leaders will always encourage constant learning.

- -

- Team Learning: the idea that two brains are better than one and the process of learning together.

- -

- Mental Models: held beliefs and assumptions that influence both organizational and personal behavior and perspectives.

- -

- Systems thinking: a framework where all parts affect each other and are perceived as interrelated.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methodology

2.2. Tools: Interviews Protocol

2.3. Participants

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

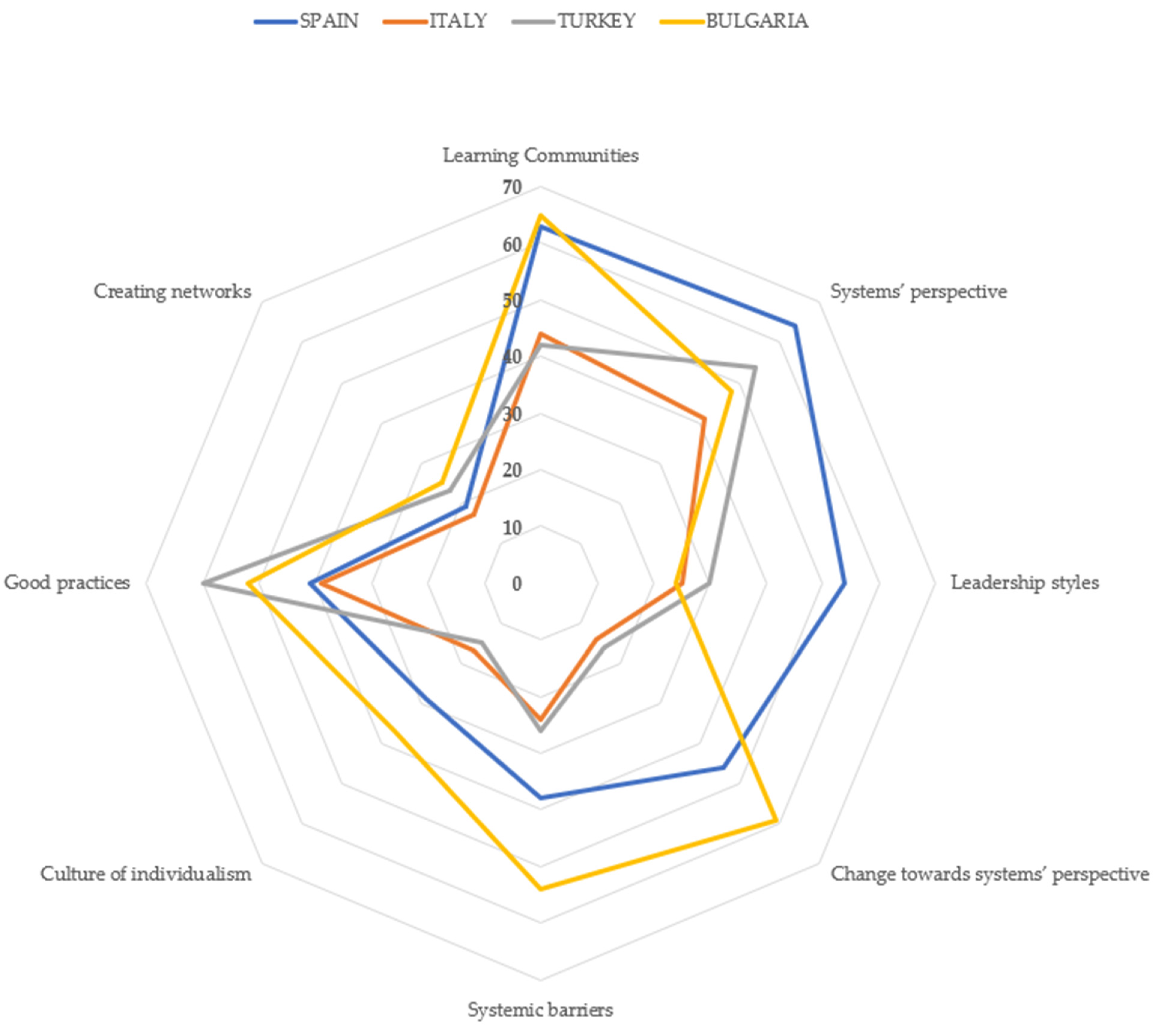

- Learning Communities: Spain and Bulgaria exhibited relatively higher occurrences of Learning Communities compared to Italy and Turkey. Spain had the highest frequency, followed by Bulgaria.

- Systems’ Perspective: Spain and Bulgaria, again, showed higher instances of the Systems’ Perspective. Italy and Turkey had lower frequencies in this aspect.

- Leadership Styles: Spain had the highest frequency of Leadership Styles, whereas Italy, Turkey, and Bulgaria had lower occurrences.

- Change towards Systems’ Perspective: Bulgaria had the highest frequency in this category. Spain had a moderate occurrence, while Italy and Turkey had lower frequencies.

- Systemic Barriers: Bulgaria had the highest frequency of Systemic Barriers, indicating that this aspect was discussed frequently in interviews conducted there, while Italy had the lowest frequency.

- Culture of Individualism: Bulgaria showed the highest occurrence of Culture of Individualism, followed by Spain. Italy and Turkey had even lower frequencies in this category.

- Good Practices: Turkey exhibited the highest frequency of Good Practices, followed by Italy and Bulgaria. Spain had a lower occurrence of this aspect.

- Creating Networks: Creating Networks had relatively low frequencies across all countries. Turkey had the highest frequency, followed closely by Italy and Bulgaria. Spain had the lowest frequency in this category.

3.1. Learning Communities & Systems’ Perspective: Transforming a School into a Learning Community

“The common participation to the life opportunity, a multicultural approach, and an emotional growth is the main content of the educational projects that the school is promoting with students in different grades/classes/subjects or levels during the school year. The social inclusion is one of the main goals of the school”.(S08, teacher 1)

“What works for us are horizontal structures, for example, the meetings that are truly effective are the ones we all have every week, like level tutorials, because that’s where common projects are generated, and common projects are solved. It’s a horizontal thing”.(S13, principal)

3.2. Leadership Styles—Moving Forward: Ups and Downs of Transformational or Pedagogical Leadership

“Unfortunately, the principals are recruited with a selection foreseeing the drafting of an essay in Italian, we do not have the tools to identify these soft skills for leadership, and perhaps these soft skills are not even at the center of the selection process”.(S07, principal)

“In public schools, the director doesn’t have that freedom, to choose the teachers nor to form the team… So, it depends on leadership and the director’s ability to engage people with the projects”.(E11)

“Focus-oriented trainings are carried out in MoNE, especially in the change of specialization of teachers. For example, in recent years, in addition to general in-service trainings such as “Inclusive Education”, trainings contributing to the development of the teacher in the field are carried out”.(E9)

“The only tool for monitoring the training that teachers receive is a record of the courses they have attended. However, it is not evaluated whether that training has a real impact in the classroom”.(E14)

“University professors who are leading projects, and I am involved in some of them, in which they have never set foot in a classroom and are asking classroom teachers for something that is impossible if they are not prepared beforehand”.(E15)

“I would like to add that we need an urgent change in the teaching plan. I had lots of conversations with colleagues teaching Informational Technologies. The teaching plan should start with preparing students to make presentations”.(S03, teacher 2)

“Generally, there is no information sharing mechanism, but groups work actively and support each other. Since our school has many teachers and departments, it is difficult to act together, and each class has different needs. We prefer to solve problems quickly within the group”.(S10, teacher 1)

3.3. Good Practices: Applying System’s Perspective in Education

“The Learning Schools are where an enlightened manager meets with teachers willing to give him credit, and there a real community is born that involves the territory and parents, which animates the students and there are innovation laboratories open”.(S06, principal)

“Open lessons for sharing teaching practices are conducted at both internal and national levels”.(E02)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Establishing a sense of urgency/needed change

- 1.1

- Do you remember any particularly significant moment of change in your school?

- 1.2

- Can you explain it please? What caused the change?

- 1.3

- (It could be, for example, a demographic, socio-economic or legislative change or an internal or external crisis or change).

- Forming a powerful coalition/Leadership and organizational culture

- 2.1

- How did you react in the face of this difficult or critical situation/change?

- 2.2

- How did you communicate the situation to your team? Who were the first people you communicated it to? How did you work with the whole school to come up with a possible solution? What decisions had to be made during the process of change and who took part into it?

- 2.3

- Did you involve teachers, parents and students, external partnering organizations, etc.?

- 2.4

- Did you need external help in the form of training, mentoring, coaching, etc.?

- Creating and communication the vision

- 3.1

- How did you work on the vision and mission of your school in way that supported changing this situation?

- 3.2

- How did you work with inter-generational differences in the team?

- 3.3

- Were there persons who resisted or continue to resist this change? How have you dealt with this resistance?

- 3.4

- How was the new vision or decision to change communicated to the educational community?

- 3.5

- What type of school would you like this to be in a few years’ time?

- Empowering others to act on the vision

- 4.1

- Did you assess the capacity of your staff to go through the change in terms of existing knowledge and qualification? Was there a plan how to fill any existing gap?

- 4.2

- Which persons within the educational community were key in promoting this change?

- 4.3

- Is there a mechanism for sharing knowledge and experience in your school among teachers in one department and/or among departments? Can you explain how this happens in practice?

- Planning for creating short-term wins

- 5.1

- What short-term objectives were established for changing the critical situation?

- 5.2

- What practical steps did you take and what tools did you use? (Task groups, research groups, interdisciplinary teams, external networks, experts mentoring and couching, etc.).

- 5.3

- Of these steps, which do you think were most successful? Which were least successful?

- 5.4

- Can you explain that please?

- Consolidating improvements and producing still more change

- 6.1

- Once these objectives were attained, what other mid- to long-term objectives were established?

- Institutionalizing new approaches

- 7.1

- Did these newly established objectives cause changes to strategic plans or school planning/practices?

- 7.2

- How were they followed up? Was there any change in your staff development plan? Can you give an example? Did it lead to sustainable innovation in the school environments, teaching process, etc.?

Appendix B

- Knowledge assessment

- 1.1

- Schools are in a situation of rapid change. It requires an upgrade in the staff/teachers’ capacity and expertise. How is that achieved in your country?

- 1.2

- Are there any instruments for teacher qualification tracking or knowledge mapping that are being used?

- 1.3

- Is there a professional development plan on team and individual level?

- Knowledge gathering

- 2.1

- What internal and external sources for staff training do schools in your country use to fill in the gaps in staff expertise?

- 2.2

- Would you give examples of such instruments (training programs, qualification courses, mentoring and couching practices)?

- 2.3

- What are the leadership training programs in the educational field in your country?

- Knowledge capturing and synthesis

- 3.1

- How efficient are existing teachers training and qualification programs? Do they lead to any practical implications, and do they solve existing problems in schools?

- 3.2

- What is the practical application of the obtained knowledge in the schools (new methodologies, new tools, new programs etc.)?

- Knowledge sharing

- 4.1

- How is the new knowledge disseminated in the organization?

- 4.2

- What are the best practices for knowledge sharing from the individual teacher to his/her department or the entire school?

- 4.3

- What are the ways for knowledge sharing on team level?

References

- Adams, Donnie, and Noni Nadiana Md Yusoff. 2020. The Rise of Leadership for Learning: Conceptualization and Practices. International Online Journal of Educational Leadership 3: 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, Joonkil. 2016. Taking a Step to Identify How to Create Professional Learning Communities—Report of a Case Study of a Korean Public High School on How to Create and Sustain a School-Based Teacher Professional Learning Community. International Education Studies 10: 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkrdem, Mofareh. 2020. Contemporary Educational Leadership and Its Role in Converting Traditional Schools into Professional Learning Communities. International Journal of Educational Leadership and Management 8: 144–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, Matthew. 2017. Transformational Leadership in Education. International Social Science Review 93: 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, Bernard M. 1985. Leadership and Performance Beyond Expectations. New York and London: Harper & Row. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, Bernard M. 1997. Does the Transactional–Transformational Leadership Paradigm Transcend Organizational and National Boundaries? American Psychologist 52: 130–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, Bernard M. 2000. The Future of Leadership in Learning Organizations. Journal of Leadership Studies 7: 18–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, Bernard M., and Ronald E. Riggio. 2006. Transformational Leadership. London: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolívar, Antonio. 2019. Una Dirección Escolar Con Capacidad de Liderazgo Pedagógico. Madrid: Editorial La Muralla. [Google Scholar]

- Bolman, Lee G., and Joan V. Gallos. 2010. Reframing Academic Leadership. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Börü, Neşe. 2020. Organizational and Environmental Contexts Affecting School Principals’ Distributed Leadership Practices. International Journal of Educational Leadership and Management 8: 172–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullough, Amanda, Richard Cotton, Ali Dastmalchian, Peter W. Dorfman, and Carolyn Egri. 2020. GLOBE 2020: The Latest Findings on Cultural Practices, Culture Change, and Leadership Ideals. Academy of Management Proceedings 2020: 17374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, James MacGregor. 1978. Leadership. New York: Harper & Row Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, John W. 2009. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, John W., and Cheryl N. Poth. 2017. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. Los Angeles and Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, John W., and Timothy C. Guetterman. 2018. Educational Research: Planning, Conducting, and Evaluating Quantitative and Qualitative Research. London: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- D’Angelo, Anne M., and Mary Katherine O’Brien. 2022. Where we go from here: A Call to Action in International Higher Education. In Mestenhauser and the Possibilities of International Education. Abingdon: Taylor and Francis, pp. 211–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deal, Terrence E., and Kent D. Peterson. 1998. Shaping School Culture: The Heart of Leadership. San Francisco: Jossey Bass Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Fullan, Michael. 2001. Leading in a Culture of Change; San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED467449 (accessed on 2 June 2023).

- Hairon, Salleh, Jonathan Wee Pin Goh, and Tzu-Bin Lin. 2014. Distributed Leadership to Support PLCs in Asian Pragmatic Singapore Schools. International Journal of Leadership in Education 17: 370–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallinger, Philip. 2003. Leading Educational Change: Reflections on the Practice of Instructional and Transformational Leadership. Cambridge Journal of Education 33: 329–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallinger, Philip. 2005. Instructional Leadership and the School Principal: A Passing Fancy That Refuses to Fade Away. Leadership and Policy in Schools 4: 221–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallinger, Philip. 2011. Leadership for Learning: Lessons from 40 Years of Empirical Research. Journal of Educational Administration 49: 125–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallinger, Philip, and Kenneth Leithwood, eds. 2013. Leading Schools in a Global Era. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, Geert, Gert Jan Hofstede, and Michael Minkov. 2010. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind. New York: McGraw Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Hudzik, John K., and Joan McCarthy. 2012. Leading Comprehensive Internationalization: Strategy and Tactics for Action. NAFSA: Association of International Educators. Available online: https://blog.stetson.edu/world/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/comprehensive-internationalization.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2023).

- Huffman, Jane B., and Kristine A. Hipp. 2001. Creating Communities of Learners: The Interaction of Shared Leadership, Shared Vision, and Supportive Conditions. International Journal of Educational Reform 10: 272–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huong, Vu Thi Mai. 2020. Factors Affecting Instructional Leadership in Secondary Schools to Meet Vietnam’s General Education Innovation. International Education Studies 13: 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jazzar, Michael, and Robert Algozzine. 2006. Keys to Successful 21st Century Leadership. Critical issues in educational leadership. Boston: Allyn & Bacon. [Google Scholar]

- Kleiner, Art, Bryan Smith, Charlotte Roberts, Peter M. Senge, and Richard Ross. 1994. The Fifth Discipline Fieldbook: Strategies for Building a Learning Organization. London: Hachette UK. [Google Scholar]

- Kools, Marco, and Louise Stoll. 2016. What Makes a School a Learning Organisation? OECD Education Working Papers 137. Paris: OECD Publishing, vol. 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kools, Marco, Louise Stoll, Bert George, Bram Steijn, Victor Bekkers, and Pierre Gouëdard. 2020. The School as a Learning Organisation: The Concept and Its Measurement. European Journal of Education 55: 24–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotter, John P. 1990. Leading Change. Available online: https://www.hbs.edu/faculty/Pages/item.aspx?num=137 (accessed on 14 April 2023).

- Kotter, John P. 1996. Leading Change. Boston: Harvard Business School Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kotter, John P. 2008. Developing a Change-Friendly Culture. Leader to Leader 2008: 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malm, James R. 2008. Six Community College Presidents: Organizational Pressures, Change Processes and Approaches to Leadership. Community College Journal of Research and Practice 32: 614–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marty, Gayla, Anne M. D’Angelo, and Mary Katherine O’Brien. 2023. Josef Mestenhauser, an International Life and Mind. In Mestenhauser and the Possibilities of International Education. Illuminating Pathways for Inquiry and Future Practice. Internationalization in Higher Education Series; London: Routledge, pp. 2–13. [Google Scholar]

- Mestenhauser, Josef A. 2002. In Search of a Comprehensive Approach to International Education: A Systems Perspective. In Rockin’ in Red Square: Critical Approaches to International Education in the Age of Cyberculture. Berlin: Lit Verlag, pp. 165–213. [Google Scholar]

- Mestenhauser, Josef A. 2011. Reflections on the Past, Present, and Future of Internationalizing Higher Education: Discovering Opportunities to Meet the Challenges. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Global Programs and Strategy Alliance. [Google Scholar]

- Northouse, Peter G. 2007. Leadership Theory and Practice, 4th ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Pacchiano, Debra, Rebecca Klein, and Marsha Shigeyo Hawley. 2016. Reimagining Instructional Leadership and Organizational Conditions for Improvement: Applied Research Transforming Early Education. Ounce of Prevention Fund. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED570105 (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Padrós, Maria, and Ramón Flecha. 2014. Towards a Conceptualization of Dialogic Leadership. International Journal of Educational Leadership and Management 2: 207–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, T., R. Carr, and J. Doldan. 2018. Strength Found through Distributed Leadership. Educational Viewpoints 38: 32–34. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, Kent D., and Terrence E. Deal. 1998. How Leaders Influence the Culture of Schools. Educational Leadership 56: 28–30. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, Kent D., and Terrence E. Deal. 2002. The Shaping School Culture Fieldbook. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Schnellert, Leyton, and Deborah L. Butler. 2021. Exploring the Potential of Collaborative Teaching Nested within Professional Learning Networks. Journal of Professional Capital and Community 6: 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senge, Peter M. 2006. The Fifth Discipline: The Art & Practice of The Learning Organization. New York: Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Sparks, Jana’. 2021. Understanding Transformational Leadership during a Time of Uncertainty. Alabama Journal of Educational Leadership 8: 10–15. [Google Scholar]

- Sukarmin, Sukarmin, and Ishak Sin. 2022. Influence of principal instructional leadership behaviour on the organisational commitment of junior high school teachers in Surakarta. Malaysian Journal of Learning and Instruction 19: 69–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Bulgaria | Italy | Turkey | Spain |

|---|---|---|---|

| S01: urban and public | S06: rural and public | S09: rural and private | S13: rural and public |

| S02: rural and public | S07: urban and public | S10: urban and public | S14: urban and private |

| S03: urban and public | S08: urban and private | S11: urban and public | S15: urban and private |

| S04: urban and private | S12: urban and public | S16: urban and private | |

| S05: urban and public |

| Bulgaria | Italy | Turkey | Spain |

|---|---|---|---|

| E01: university affiliated | E05: university affiliated | E09: university affiliated | E13: university affiliated |

| E02: government affiliated | E06: university affiliated | E10: university affiliated | E14: government affiliated |

| E03: government affiliated | E07: university affiliated | E11: government affiliated | E15: university and government affiliated |

| E04: government affiliated | E08: government affiliated | E12: government affiliated |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sierra-Huedo, M.L.; Romea, A.C.; Aguareles, M. Are Schools Learning Organizations? An Empirical Study in Spain, Bulgaria, Italy, and Turkey. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 495. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12090495

Sierra-Huedo ML, Romea AC, Aguareles M. Are Schools Learning Organizations? An Empirical Study in Spain, Bulgaria, Italy, and Turkey. Social Sciences. 2023; 12(9):495. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12090495

Chicago/Turabian StyleSierra-Huedo, María Luisa, Ana C. Romea, and Marina Aguareles. 2023. "Are Schools Learning Organizations? An Empirical Study in Spain, Bulgaria, Italy, and Turkey" Social Sciences 12, no. 9: 495. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12090495

APA StyleSierra-Huedo, M. L., Romea, A. C., & Aguareles, M. (2023). Are Schools Learning Organizations? An Empirical Study in Spain, Bulgaria, Italy, and Turkey. Social Sciences, 12(9), 495. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12090495