Abstract

Qualitative research has been increasingly used in the field of psychology. Consequently, concerns about the development of students’ skills in qualitative research have arisen. The main goal of this paper is to characterize the current state of art of the qualitative research teaching in Portuguese bachelor’s degrees in psychology. A documentary analysis was performed, and the data collection was conducted through an online search: first on the website of the General Directorate of Higher Education, and afterwards on the online sites of each of the Portuguese universities where the first cycle of psychology is taught. A content analysis was made by two coders and a discussion about categories was made until a consensus was reached. The data revealed the existence of 31 undergraduate courses in psychology at 31 Portuguese teaching institutions. There were 12 undergraduate courses at 12 public universities, and 19 undergraduate courses at 19 private universities. Despite the diversity in the study plans in the degree of psychology, most of them included qualitative research methodology teaching. However, the data analysis revealed different designations of the curricular units (CUs) related to qualitative research, as well as a different number of credits (European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System—ECTS). In addition, there were variations in the academic year in which the qualitative research CUs were taught and registered in their syllabi. This study indicates that undergraduate Portuguese psychology students generally have some training in qualitative research but the way it is carried out and the training contents are not uniform for all the existing degrees. It is important to reflect on the importance of qualitative research in psychology and further studies on qualitative methods teaching practices are still needed.

1. Introduction

Qualitative research is a form of scientific research that is recognized as a fully fledged research domain (Denzin and Lincoln 2017). Nevertheless, qualitative research is currently facing a redefinition of its position in the production of science and its characterization. New challenges are being created, and new nomenclatures are emerging (e.g., qualitative research or qualitative inquiry) (Denzin and Lincoln 2017). Despite this, qualitative research continues to be seen from the perspective of studying the social environment in a naturalistic context, aiming to interpret and make the world visible, as well as to transform it (Denzin and Lincoln 2017). Nevertheless, due to the diversity of techniques that can be applied, the designation of qualitative research is still an umbrella expression that embraces the multifariousness of methods and approaches that can be used within the qualitative research framework (Saldaña 2011).

In general, qualitative research methods can be characterized into three main types concerning the use of words, images, and observation, which can be used in a combined or isolated form (De Souza et al. 2018). There may be multiple data sources (e.g., interviews transcripts, fieldnotes, photographs, videos, Internet sites) (Saldaña 2011); for this reason, qualitative researchers can be seen as a bricoleur because they manage different materials that must be interpreted and given meaning (Denzin and Lincoln 2017).

Qualitative research can be used in a wide range of scientific areas, such as education, sociology, anthropology, and psychology (to mention but a few) (Saldaña 2011). However, in the field of psychology, quantitative methods have been the prevalent means of psychological scientific production (Povee and Roberts 2014; Roberts and Castell 2016; Roberts and Povee 2014; Rubin et al. 2018; Wiggins et al. 2015). Despite its secondary role, qualitative research in psychology has been carried out by some researchers, and questions about the way that qualitative research should be conducted in this scientific domain have emerged. Consequently, epistemological issues have been discussed. For instance, concerning epistemological topics, some authors defend the idea that psychology should adopt a “generic qualitative inquiry” to investigate “people’s reports of their subjective opinions, attitudes, beliefs, or reflections on their experiences, of things in the outer world” (Percy et al. 2015, p. 78) because sometimes traditional approaches do not seem to be an appropriate way to support the research. The use of a generic frame for some psychological research is suggested by Percy et al. (2015), rather than the typical qualitative approaches that are well-described in the literature, such us phenomenology, case study, ethnography, narrative, and grounded theory (Creswell 2007).

In fact, qualitative studies have moved forward and, in recent years, psychology journals focusing on qualitative research have been established (Brinkmann 2017). An important factor in the use of qualitative research in psychology is the Publication Manual of the American Psychology Association (APA) (2020) and its specific sections on Reporting Standards for Qualitative Research and Reporting Standards for Mixed Research Methods. This manual and a previous work published by Levitt et al. (2017) are important milestones in the recognition of qualitative research in psychology and development of quality qualitative studies.

Due to the growing acceptance of qualitative research, Murray (2019) organized a Special Issue dedicated to its progress over the previous 40 years in European countries. The author emphasized the value of rethinking qualitative research, mainly its purposes and assumptions, and how it can contribute to equality and social justice, specifically the evident significance of the use of qualitative methods after the communist era for Czech and Slovak psychologists, who deemed qualitative research an opportunity to develop new and critical approaches (Masaryk et al. 2019). Kovács et al. (2019) conducted research in some Central–Eastern European countries (Hungary, Slovakia, Czech Republic, Poland, and Romania), analyzing articles published after those countries joined the European Union. They again highlighted the importance of political and social background in qualitative research and found a predominance of constructivist/interpretivist approaches, as well as mixed paradigms. Effectively, the authors suggested that maybe “the true nature of the qualitative approach is that it does not require a rigorously defined identity and formula or systematically structured frames” (Kovács et al. 2019, p. 369). In fact, Restivo and Apostolidis (2019) explained how important the expansion of mixed methodologies can be for qualitative research. They mentioned that qualitative research was underrepresented in France, despite its growing representation, over the last 20 years, mainly due to the use of mixed methodologies. Therefore, these authors considered triangulation and mixed research designs to be an asset to the development of qualitative research.

Looking at the Spanish case, Gemignani et al. (2019) evidenced the use of qualitative research to understand and change the social reality after a dictatorship. However, a predominance of quantitative studies was registered, despite the existence of a nuclei of qualitative researchers. They argued that perhaps this small number could be explained by the competitive publication process and the perception that qualitative researchers are less appreciated. Again, mixed research was referred as a possibility for investigations and when dealing with the complexity of the studied phenomena. Gemignani et al. (2019) highlighted a sign of hope for qualitative research by referring to the National Agency for Quality Assessment and Accreditation of Spain (ANECA), who stated, in 2005, that the study plans for psychology should include qualitative and quantitative research methods so that students could develop skills in both areas. With that in mind, we can also note the situation in the United Kingdom (UK), where most of the study plans for psychology degrees incorporate qualitative methods at present (Riley et al. 2019). This is a result of a previous path and reflects the consolidation of qualitative research in psychology. In this country, it seems that the use of qualitative research in psychology has been recognized in a more structured way. For instance, in 2005, the Qualitative Methods in Psychology (QMiP) Section of the British Psychology Society (BPS) was created in a context in which several qualitative studies were taking place. However, qualitative research was associated with a minority status and achieving government-level quantitative research systems is still a challenge that needs to be addressed (Riley et al. 2019).

We can see that as more work is carried out using qualitative methods, and throughout the appropriation of qualitative research in psychology, discussions about the quality of qualitative researchers arose as well as discussions about qualitative research teaching. Although there are several manuals about qualitative research, there are still few investigations into teaching qualitative methods and the best evidence-based practices (Castell et al. 2022; Wagner et al. 2019).

In general, teaching qualitative research requires several changes to be made by teachers (Amado 2014), and the domain of psychology is not exempt from these (Gibson and Sullivan 2012). Thinking of qualitative research as an integral and required part of psychology professionals’ training, as Howitt (2010) suggested, implies thinking about training opportunities and modalities. Thus, it is being demanded that qualitative research is taught to psychology students and implemented in the study plans, for instance, in the United States (US) (Rubin et al. 2018). In Europe, in the UK, teaching qualitative research seems to be more frequent, at least in clinical psychology training programs that registered some training in this methodology in 1992 (Harper 2012). It is worth mentioning that, in the UK, psychology training programs must include qualitative research methods according to the national bodies (Gibson and Sullivan 2018). Obviously, the implementation of qualitative research training practices is determined by the department researchers and their dominant practice, background, openness to qualitative research and willingness to truly invest in qualitative research teaching (Cox 2012; Gibson and Sullivan 2018).

Concerning psychology students’ training, the European Federation of Psychologists Associations (EFPA), for those pursuing an academic education and professional training of psychologists’ standards, offers a framework for the curriculum for EuroPsy certification (European Certificate in Psychology). As can be seen on their webpage, in the first phase of the EuroPsy certification curriculum, that is, the Bachelor’s degree, students must have curricular units (CUs) that include qualitative research to promote the development of their methodological knowledge (“qualitative and quantitative methods”) and methodological skills (“Data acquisition training, qualitative analysis”) (EuroPsy 2022a). In the second phase of the EuroPsy certification curriculum, concerning master’s degrees, students must have the opportunity to develop their qualitative methodology knowledge (“Qualitative research design, including advanced interviewing and use of questionnaire, qualitative data analysis”) and skills, especially the “skills training in above mentioned methods and techniques” (EuroPsy 2022b). However, the EFPA guidelines are not mandatory and different universities across Europe can stipulate different study plans, including or not including qualitative research teaching.

Castell et al. (2022) presented a very interesting study where they summarize important points for psychology qualitative teachers to consider. Recognizing qualitative research as a legitimate research approach, they defended the idea that qualitative topics such as epistemological approaches, methodologies, and analysis must not be taught at once. They also highlighted the importance of qualitative students embracing uncertainty. Several authors referred to epistemology and methodologies as the main topics in teaching qualitative research, which might enable students to develop the research skills required in qualitative research (Clarke and Braun 2013; Terkildsen and Petersen 2015). Experiential activities have long been recommended (Fontes and Piercy 2000) and practical demonstrations in the field of psychology have been presented (e.g., Danquah 2017; Soares et al. 2020), as well as suggestions for teachers (e.g., Forrester and Koutsopoulou 2008).

In Portugal, the country in which the present study is taking place, research on teaching qualitative investigation in psychology is scarce, although some work on pedagogical practices and the impact of classes on qualitative research methods has already been carried out (Antunes 2017a, 2017b; Antunes and Araújo 2021).

Thus, starting from the gap in qualitative research and qualitative research teaching in psychology in Portugal, we designed this study to better understand psychology students’ training in this methodology. Therefore, the main goal of this paper is to characterize the current state of the art in qualitative research teaching in the Portuguese bachelor’s degrees in psychology through the analysis of the official study plans. Therefore, four research questions were formulated: (1) Is qualitative research included in the students’ training? (2) Is qualitative research recognized as a fully fledged research domain? (3) What are the main topics related to qualitative research in the syllabi? (4) What teaching methods are used?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

As the purpose of this study was to obtain a better understanding of the Portuguese reality, a documentary analysis was performed (Silva 2021). A documentary analysis is a suitable option because: (a) the collected documents may reveal data related to the topic; (b) the data may reveal questions and other situations that need to be considered in the research; (c) supplementary data may be provided by the collected documents and may make important contributions to the field; (d) the available documents may check changes and developments over time; and (e) documents may be analyzed to verify or corroborate findings (Bowen 2009). According to Morgan (2022), the “document analysis is a valuable research method that has been used for many years” (p. 64). When following this method, a range of documents (e.g., newspaper articles or institutional reports) can be analyzed using quantitative or qualitative methods (Morgan 2022).

2.2. Materials and Procedures

To collect the information, the categories were a priori defined and organized in a grid. Those categories were: name of the CU (it is important to identify the CU and note whether it is seen as a specific domain); academic year (it is important to know when students learn qualitative research); semester (it is meaningful to know when students are taught qualitative research); number of credits: European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System (ECTS) (it is important to know the credits associated to the CUs because they are related to the time students dedicate to the CU); program (it is important to understand the main themes being taught because of the variety of topics in qualitative research); teaching methodologies, including evaluation (it is significant to know the teaching and learning process as well as the evaluation process); and access link (it is important to credit the information source).

A documentary analysis was performed, and the data collection was conducted through an online search divided into two phases:

- (a)

- First, on the website of the General Directorate of Higher Education, Portuguese teaching institutions offering bachelor’s degrees in psychology were found;

- (b)

- Second, on the online sites of each of the Portuguese universities, where the first cycle of Psychology is taught, online documents (information at the webpages) about qualitative research methods were searched.

The online search was conducted separately by two researchers, filling in the grid, and following the described steps. One researcher conducted the online search in October 2022 and January 2023, and the other researcher conducted the online search in February 2023. After comparison and discussion, a last online search was conducted in April 2023 to check the information.

The collected data revealed the existence of 31 undergraduate courses in psychology at 31 Portuguese teaching institutions. Specifically, there were 12 undergraduate courses at 12 public universities (Table 1), and 19 undergraduate courses at 19 private universities (Table 2).

Table 1.

Public universities with a psychology degree.

Table 2.

Private universities with a psychology degree.

No approval from the Ethics Committee of the researcher’s institution was needed to conduct this research because it did not involve human participants or health-related data collection. Despite that, data were processed according to the General Data Protection Regulation and were used strictly for research purposes.

2.3. Data Analysis

As mentioned before, the collected information was organized in the grid, so a comparison could be made between data and a respective analysis could be carried out. A comparison and discussion of the collected data was made by two coders until consensus was reached. To analyze the content of the documents, the contributions of Bardin (2008) were followed, namely, the preparation of the material, and the questioning and interpretation of data. Specifically, the main steps of analysis were:

- (a)

- First, the qualitative research curricular units (CUs) or CUs related to qualitative research in the study plans were identified;

- (b)

- Second, the syllabus of the selected CUs was analyzed, considering the a priori defined categories: name of the CU; academic year; semester; number of ECTS; program; and teaching methodologies, including evaluation.

After checking the study plan of each university, the contents of the CUs related to research methods (mentioning qualitative research or a general designation) were analyzed. All public universities had online information about their CUs related to qualitative research (Table 1). Four psychology degrees at private universities only had general designations for the CUs and did not have available online information about them, so they were not included in that specific analysis (Table 2). In one psychology degree at one private university, CUs related to qualitative research, were not found. Thus, for the purpose of this study, CU data from 12 psychology courses at public universities and 14 psychology courses at private universities were considered. In these 26 psychology undergraduate courses, 31 CUs related to qualitative research were found, with 16 CUs at public universities and 15 CUs at private universities, but only seven of the latter had programs that were available online, so the others could not be included in the program analysis (Table 3 and Table 4). The information (document) collected about each CU was coded with the letter F and an alphanumeric number.

Table 3.

CUs related to qualitative research in psychology degrees at public universities.

Table 4.

CUs related to qualitative research in psychology degrees at private universities.

3. Results

At present, psychology undergraduate courses exist at 31 Portuguese teaching institutions: 12 of them are public and 19 are private. Thus, from the available data, in 26 psychology undergraduate courses, 31 CUs related to qualitative research were found. The collected data showed diversity in the general study plans of the universities and concerning the presence of qualitative research/methodologies. Most of the undergraduate study plans that were analyzed included the teaching of qualitative research methodologies. However, differences in the designation of the research methods regarding the curricular units (CUs), taught academic year, and number of their European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System (ECTS), as well as in the formulated syllabus, were registered. These concrete results are shown in the following.

3.1. Designations of the CUs Related to Qualitative Research

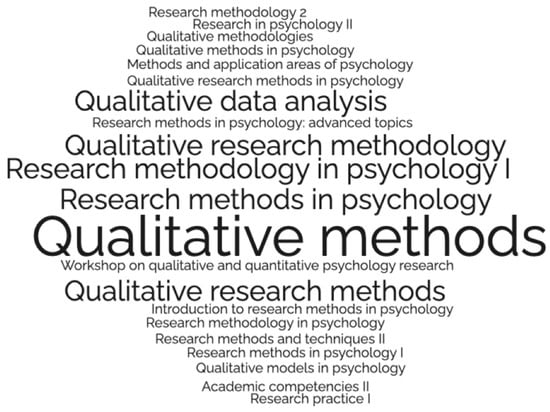

We registered 21 different CU designations for the 31 CUs related to qualitative research (Figure 1). From those 21 CU designations, the most frequent were qualitative methods (n = 4) and research methods in psychology (n = 4), followed by research methodology in psychology I (n = 2), qualitative research methodology (n = 2), qualitative research methods (n = 2) and qualitative data analysis (n = 2), while the other 15 appeared just once.

Figure 1.

Designations of the CUs.

Of all the 21 CU designations, only 9 included the specific word “qualitative”: workshop on qualitative and quantitative psychology research, qualitative research methods in psychology, qualitative research methods, qualitative research methodology, qualitative models in psychology, qualitative methods in psychology, qualitative methods, Qualitative methodologies, and qualitative data analysis.

The other CUs were designated by generic names (research practice I, research methods in psychology: advanced topics, research methods in psychology I, research methods in psychology, research methods and techniques II, research methodology in psychology I, research methodology in psychology, research methodology 2, research in psychology II, methods and application areas of psychology, introduction to research methods in psychology, and academic competencies II), except the workshop on qualitative and quantitative psychology research, which included both methods explicitly.

3.2. Frequency of CUs Related to Qualitative Research

The 31 CUs related to qualitative research from 26 psychology undergraduate courses were distributed in the study plans along the three academic years of the degree (Table 5). However, they were more frequent in the second year (n = 13), followed by the first year (n = 12), and much less frequent in the third year (n = 5).

Table 5.

Frequency of CUs related to qualitative research at public and private universities.

3.3. Number of ECTS of the CUs Related to Qualitative Research

The data analysis revealed that, in addition to these differences, the CUs related to qualitative research were also dissimilar concerning the respective number of ECTS (Table 6). Nevertheless, most of them had six ECTS, mainly from psychology courses at public universities.

Table 6.

Frequency of the CUs related to qualitative research concerning their ECTS at public and private universities.

3.4. Programs of the CUs Related to Qualitative Research

The content analysis of the programs of the UCs related to qualitative research revealed two main categories:

- (a)

- CUs with topics on both quantitative and qualitative methods (n = 14);

- (b)

- CUs with topics exclusively about qualitative methods (n = 9).

Table 7.

Subcategories of CUs with topics on both quantitative and qualitative methods.

Table 8.

Subcategories of CUs with topics exclusively focused on qualitative methods.

3.5. Teaching Methodologies (Including Evaluation)

The content analysis of the teaching methodologies (including evaluation) of the UCs related to qualitative research revealed that these are generally organized in theoretical and practical classes (sometimes laboratorial practices also exist). The teaching and learning process is developed through three methods:

- (a)

- Expositive, mainly theoretical classes, where teachers explain the qualitative research contents (e.g., “The expositive techniques used in the theoretical classes are fundamental to clarify the concepts associated to the curricular unit.”—F11);

- (b)

- Interrogative, sometimes used in conjunction with the expositive method, where teachers ask students and determine their understanding of the subject (“…specific aspects are presented and discussed with the students…”—F2);

- (c)

- Active, mainly practical classes, which demands students’ interaction, application of knowledge and active development of qualitative research skills (e.g., “There will feature examples of previous research to illustrate methods and techniques. Supporting materials will be available in the form of manuals or obtained through students’ own research. Practical exercises will be conducted in class, such as construction of instruments for the collection of qualitative data, simulation of interviews and focus groups, as well as data analysis using the software MAXQDA.—F17).

Regarding the evaluation process, qualitative research teachers generally evaluate the competences developed by the students during the semester through:

- (a)

- Written exams, asking students to answer questions individually (one or two exams);

- (b)

- Research works, requiring students to develop qualitative research skills (group work and sometimes individual work).

4. Discussion and Conclusions

The analyzed data made it possible to achieve the objective of the study, that is, to provide an overview of the qualitative research methods being taught in Portuguese bachelor’s degrees in psychology. In fact, most of the undergraduate Portuguese psychology courses contain some training in qualitative research methods. However, differences could be found in CUs related to qualitative research. Since there is no description of the current situation of psychology qualitative research teaching in Portugal as there is for other European countries (Gemignani et al. 2019; Kovács et al. 2019; Masaryk et al. 2019; Restivo and Apostolidis 2019; Riley et al. 2019), this work makes a contribution to that issue.

According to data collection, in the Portuguese psychology students’ training there is, generally, an opportunity to learn qualitative research. Undergraduate Portuguese psychology degrees seem to be in line with the standards of EuroPsy (2022a) for a bachelor’s degree. So, if students from that psychology course want to ask for the European Certificate in psychology, they meet the conditions regarding the training methodology, knowledge (“qualitative and quantitative methods”) and methodological skills (“Data acquisition training, qualitative analysis”) (EuroPsy 2022a). Hence, it would be expected that qualitative research methods are contained in the study plans in European psychology universities. Thus, it would be also expected that the Portuguese universities might consider the aforementioned guidelines in their study plans, despite their not being mandatory, so future psychologists can obtain EuroPsy certification. However, not all countries contain qualitative research teaching in their study plans (Castell et al. 2022), and neither do all Portuguese psychology courses have it (e.g., we found one psychology course degree without qualitative training).

Following a closer look at the undergraduate courses and the CUs related to qualitative research, diversity in the syllabi was found. Very different syllabi were registered, which might be due to the autonomy that Portuguese universities possess to organize their academic plans if they are approved by the National Agency of Assessment and Accreditation of Higher Education (Agência de Avaliação e Acreditação do Ensino Superior (A3ES)). This heterogeneity may also correspond to the heterogeneity of teaching objectives or reflect the incipient stage of qualitative research teaching in our country and universities, and teachers are still mainly embedded in quantitative research (Cox 2012; Gibson and Sullivan 2018). This Portuguese Agency has not clearly assumed qualitative research to be an asset in psychology students’ training, as opposed to Spain, the neighboring country of Portugal (Gemignani et al. 2019), and UK (Gibson and Sullivan 2018), where national boards have determined this.

The data seem to reveal the supremacy of quantitative methods, especially CUs that teach quantitative and qualitative methods. In all the study plans, students have more training in quantitative research, similarly to what has been found in other countries (Povee and Roberts 2014; Roberts and Castell 2016; Roberts and Povee 2014; Rubin et al. 2018; Wiggins et al. 2015) and testified by Portuguese students (Antunes 2017a; Antunes and Araújo 2021).

In fact, some UCs contain qualitative research, but its inclusion is only introductory and generic. However, in other cases, the syllabus includes a wider range of contents in a manner similar to syllabi containing CUs exclusively related to qualitative research. Therefore, it is important to note what Castell et al. (2022) said about not teaching all topics at the same time, and consider that this is the students’ first introduction to qualitative research. If teachers assume that qualitative research is a valid and scientific perspective (Castell et al. 2022), the undifferentiated designations of the CUs and respective programs must be considered. We think that the lack of specificity might be related to teachers assuming they are qualitative researchers and adopting a mixed position, teaching both qualitative and quantitative methods. In fact, the difficulties faced by qualitative researchers to be recognized and qualitative projects should also be sponsored in other countries, as documented in the literature (e.g., Gemignani et al. 2019; Riley et al. 2019).

It is true that the diversity and ambiguity of qualitative research might lead to the miscellaneous syllabi we found, and this might also reflect the different authors’ perspectives (Castell et al. 2022). Nevertheless, the categories and subcategories found in the curricular program analysis (reflecting epistemological and methodological topics) seem to reveal teachers’ concerns regarding students’ learning of qualitative research and consequent development of research skills, albeit at an initial level (Clarke and Braun 2013; Terkildsen and Petersen 2015). The teaching methods and students’ evaluation demonstrate that teachers want to explain epistemological positions and train students in the development of qualitative skills through experiential activities such as practical exercises or teamwork (Clarke and Braun 2013; Fontes and Piercy 2000; Terkildsen and Petersen 2015).

The uncertainty that Castell et al. (2022) recommended that students embrace must be adopted by teachers as well. The picture we drew about qualitative research showed the challenging task that qualitative research teachers face when teaching, as already mentioned in the literature (Amado 2014; Gibson and Sullivan 2012). No guidelines are available in the field in Portugal and teachers can learn from the experience of the few existing works by foreign authors (e.g., Danquah 2017; Forrester and Koutsopoulou 2008; Soares et al. 2020). Although qualitative research is not mandatory in Portuguese undergraduate psychology courses, a growing interest in those research methods has been registered and, as in other countries, we think that Portuguese psychology courses are growing able to accommodate this research perspective (Roberts and Castell 2016; Rubin et al. 2018).

The results corroborate the need to study teaching practices focusing on qualitative methods (also in Portugal) because there is limited research available in the field about teaching qualitative methods and the best evidence-based practices (e.g., Antunes 2017a, 2017b; Antunes and Araújo 2021; Castell et al. 2022; Danquah 2017; Wagner et al. 2019).

Despite the contributions of this study, some limitations should be addressed. Firstly, some private universities did not have information about their study plans available online, so it was not possible to analyze their data and, consequently, we did not obtain “the whole picture” about the Portuguese psychology courses. Secondly, some of the available information was too generic; knowing the specific contents would help to deepen the knowledge and understanding of the syllabi. Therefore, information collected directly from teachers (through interview or survey) would be an asset. Lastly, there was limited transferability of these findings to other courses or fields due to the nature of the study.

In sum, future studies could be conducted focusing on bachelor’s degrees as well as in master’s degrees to better know and understand the state of qualitative research teaching to future Portuguese psychologists. The present paper has revealed part of the current situation in the psychology field.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.P.A.; methodology, A.P.A. and S.M.; formal analysis, A.P.A. and S.M.; investigation, A.P.A. and S.M.; data curation, A.P.A. and S.M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.P.A. and S.M.; writing—review and editing, A.P.A. and S.M.; visualization, A.P.A. and S.M.; supervision, A.P.A.; project administration, A.P.A.; funding acquisition, A.P.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was financially supported by Portuguese national funds through the FCT (Foun-dation for Science and Technology) within the framework of the CIEC (Research Center for Child Studies of the University of Minho) projects under the references UIDB/00317/2020 and UIDP/00317/2020.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data analyzed and presented in this study are referenced in the published article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Amado, João. 2014. A Formação Em Investigação Qualitativa: Notas Para a Construção de Um Programa. In Investigação Qualitativa: Inovação, Dilemas e Desafios. Edited by António Pedro Costa, Francislê Neri Souza and Dayse Neri Souza. Oliveira de Azeméis: Ludomédia, vol. 1, pp. 39–67. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychology Association (APA). 2020. Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association, 7th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychology Association. [Google Scholar]

- Antunes, Ana Pereira. 2017a. Ensinar Investigação Qualitativa: Experiência de Unidade Curricular Num Curso de Mestrado Em Psicologia Da Educação [Teaching Qualitative Research: Experience of a Curricular Unit in a Masters Course in Educational Psychology]. Paper presented at CNaPPES 2016: Congresso Nacional de Práticas Pedagógicas No Ensino Superior, Lisbon, Portugal, July 14–15; Edited by Patrícia Rosado Pinto. pp. 219–25. Available online: https://cnappes.org/cnappes-2016/files/2014/03/Livro-de-Atas-do-CNaPPES-2016-3.pdf (accessed on 7 October 2022).

- Antunes, Ana Pereira. 2017b. Formação Académica Em Metodologia Qualitativa: Prática Pedagógica Em Psicologia Da Educação. Revista Lusofona de Educacao 36: 147–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunes, Ana Pereira, and Sara Barros Araújo. 2021. Qualitative Research Teaching in (Educational) Psychology: Perceived Impact on Master’s Degree Students. Revista Lusofona de Educacao 51: 153–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardin, Laurence. 2008. Análise de Conteúdo, 4th ed. Lisboa: Edições 70. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, Glenn A. 2009. Document Analysis as a Qualitative Research Method. Qualitative Research Journal 9: 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkmann, Svend. 2017. Humanism after Posthumanism: Or Qualitative Psychology after the ‘Posts’. Qualitative Research in Psychology 14: 109–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castell, Emily, Shannon Muir, Lynne D. Roberts, Peter Allen, Mortaza Rezae, and Aneesh Krishna. 2022. Experienced Qualitative Researchers’ Views on Teaching Students Qualitative Research Design. Qualitative Research in Psychology 19: 978–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, Victoria, and Virginia Braun. 2013. Teaching Thematic Analysis: Overcoming Challenges and Developing Strategies for Effective Learning. The Psychologist 26: 120–23. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, Rebecca D. 2012. Teaching Qualitative Research to Practitioner-Researchers. Theory into Practice 51: 129–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, John W. 2007. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches, 2nd ed. London: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Danquah, Adam N. 2017. Teaching Qualitative Research: A Successful Pilot of an Innovative Approach. Psychology Teaching Review 23: 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, Maria Cecília, Minayo António, Pedro Costa, and Revista Lusófona De Educação. 2018. Fundamentos Teóricos Das Técnicas de Investigação Qualitativa. Revista Lusófona de Educação 40: 139–53. Available online: https://revistas.ulusofona.pt/index.php/rleducacao/article/view/6439 (accessed on 8 April 2023).

- Denzin, Norman K., and Yvonna S. Lincoln. 2017. Introduction: The Discipline and Practice of Qualitative Research. In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research, 5th ed. Edited by Norman K. Denzin and Yvonna S. Lincoln. London: Sage, pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- EuroPsy. 2022a. Curriculum Content of the First Phase Bachelors. Available online: https://europsy-bg.com/en/bachelors-degree/ (accessed on 7 October 2022).

- EuroPsy. 2022b. Curriculum Content of the Second Phase Masters. Available online: https://europsy-bg.com/en/masters-degree/ (accessed on 7 October 2022).

- Fontes, Lisa Aronson, and Fred P. Piercy. 2000. Engaging Students in Qualitative Research through Experiential Class Activities. Teaching of Psychology 27: 174–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrester, Michael A., and Gina Z. Koutsopoulou. 2008. Providing Resources for Enhancing the Teaching of Qualitative Methods at the Undergraduate Level: Current Practices and the Work of the HEA Psychology Network Group. Qualitative Research in Psychology 5: 173–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemignani, Marco, Sara Ferrari, and Isabel Benítez. 2019. Rediscovering the roots and wonder of qualitative psychology in Spain: A cartographic exercise. Qualitative Research in Psychology 16: 417–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, Stephen, and Cath Sullivan. 2012. Teaching Qualitative Research Methods in Psychology: An Introduction to the Special Issue. Psychology Learning & Teaching 11: 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, Stephen, and Cath Sullivan. 2018. A Changing Culture? Qualitative Methods Teaching in U.K. Psychology. Qualitative Psychology 5: 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, David J. 2012. Surveying Qualitative Research Teaching on British Clinical Psychology Training Programmes 1992–2006: A Changing Relationship? Qualitative Research in Psychology 9: 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howitt, Dennis. 2010. Introduction to Qualitative Methods in Psychology. London: Pearson Education Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Kovács, Asztrik, Dániel Kiss, Szilvia Kassai, Eszter Pados, Zsuzsa Kaló, and József Rácz. 2019. Mapping qualitative research in psychology across five Central-Eastern European countries: Contemporary trends: A paradigm analysis. Qualitative Research in Psychology 16: 354–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitt, Heidi, Sue Motulsky, Fredrick Wertz, Susan Morrow, and Joseph G. Peterotto. 2017. Recommendations for Designing and Reviewing Qualitative Research in Psychology: Promoting Methodological Integrity. Qualitative Psychology 4: 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masaryk, Radomír, Magda Petrjánošová, Barbara Lášticová, Nikoleta Kuglerová, and Wendy Stainton Rogers. 2019. A story of great expectations. Qualitative research in psychology in the Czech and Slovak Republics. Qualitative Research in Psychology 16: 336–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, Hani. 2022. Conducting a Qualitative Document Analysis. Qualitative Report 27: 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, Michael. 2019. Some thoughts on qualitative research in psychology in Europe. Qualitative Research in Psychology 16: 508–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Percy, William H., Kim Kostere, and Sandra Kostere. 2015. Generic Qualitative Research in Psychology. Qualitative Report 20: 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Povee, Kate, and Lynne D. Roberts. 2014. Qualitative Research in Psychology: Attitudes of Psychology Students and Academic Staff. Australian Journal of Psychology 66: 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restivo, Léa, and Thémis Apostolidis. 2019. Triangulating Qualitative Approaches within Mixed Methods Designs: A Theory-Driven Proposal Based on a French Research in Social Health Psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 16: 392–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, Sarah, Joanna Brooks, Simon Goodman, Sharon Cahill, Peter Branney, Gareth J. Treharne, and Cath Sullivan. 2019. Celebrations amongst challenges: Considering the past, present and future of the qualitative methods in psychology section of the British Psychology Society. Qualitative Research in Psychology 16: 464–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, Lynne D., and Emily Castell. 2016. ‘Having to Shift Everything We’ve Learned to the Side’: Expanding Research Methods Taught in Psychology to Incorporate Qualitative Methods. Frontiers in Psychology 7: 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, Lynne D., and Kate Povee. 2014. A Brief Measure of Attitudes towards Qualitative Research in Psychology. Australian Journal of Psychology 66: 249–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, Jennifer D., Sarah Bell, and Sara I. McClelland. 2018. Graduate Education in Qualitative Methods in U.S. Psychology: Current Trends and Recommendations for the Future. Qualitative Research in Psychology 15: 29–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldaña, Jonny. 2011. Fundamentals of Qualitative Research. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, Carlos Guardado. 2021. Investigação Documental [Documentary Research]. In Manual de Investigação Qualitativa: Conceção, Análise e Aplicações. Edited by Sónia P. Gonçalves, Joaquim P. Gonçalves and Célio Gonçalo Marques. Lisboa: PACTOR, pp. 103–23. [Google Scholar]

- Soares, Laura Cristina Eiras Coelho, Ariane Agnes Corradi, and Déborah David Pereira. 2020. O Ensino de Métodos Qualitativos Em Psicologia: Ampliando Perspectivas Científicas Sob o Enfoque de Direitos Humanos. Curriculo Sem Fronteiras 20: 459–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terkildsen, Thomas, and Sofie Petersen. 2015. The Future of Qualitative Research in Psychology—A Students’ Perspective. Integrative Psychological and Behavioral Science 49: 202–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, Claire, Barbara Kawulich, and Mark Garner. 2019. A Mixed Research Synthesis of Literature on Teaching Qualitative Research Methods. SAGE Open 9: 2158244019861488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiggins, Sally, Alasdair Gordon-Finlayson, Sue Becker, and Cath Sullivan. 2015. Qualitative Undergraduate Project Supervision in Psychology: Current Practices and Support Needs of Supervisors across North East England and Scotland. Qualitative Research in Psychology 13: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).