Quality of Life and Well-Being of Older Adults in Nursing Homes: Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Critical Appraisal

2.6. Content Synthesis

3. Results

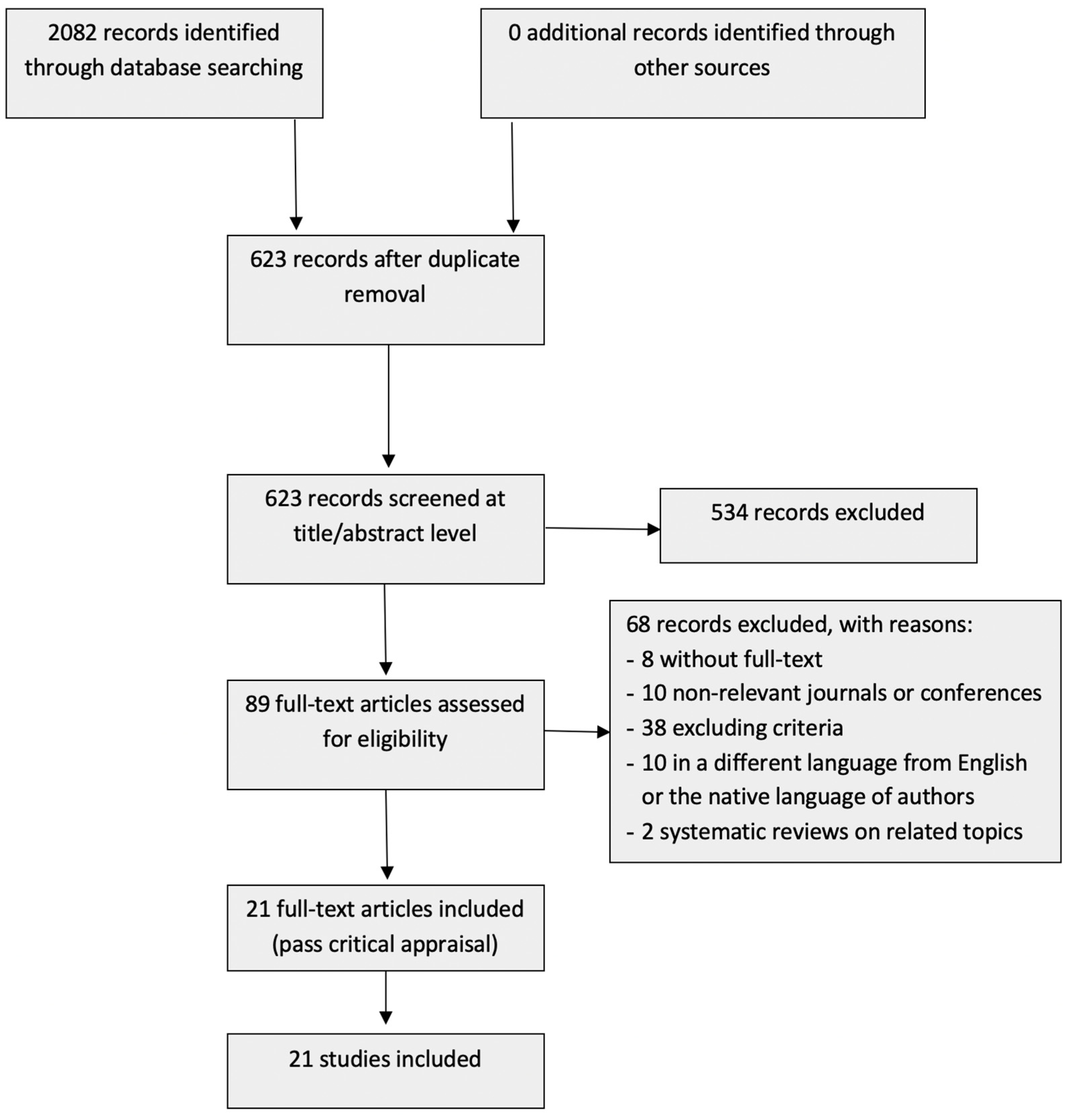

3.1. Selection Process

3.2. Characteristics of the Studies Included in the Content Synthesis

3.3. Methodological Quality Assessment

3.4. Findings of the Studies

3.4.1. QoL and WB Models or Scales

3.4.2. Stakeholders’ Views and Perceptions of QoL and WB

3.4.3. Determination of QoL and WB through Factors and Their Relationships

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adra, Marina Gharibian, John Hopton, and John Keady. 2015. Constructing the meaning of quality of life for residents in care homes in the Lebanon: Perspectives of residents, staff and family. International Journal of Older People Nursing 10: 306–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adra, Marina Gharibian, John Hopton, and John Keady. 2017. Nursing home quality of life in the Lebanon. Quality in Ageing and Older Adults 18: 145–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspden, Trefor, Siobhan A. Bradshaw, E. Diane Playford, and Afsane Riazi. 2014. Quality-of-life measures for use within care homes: A systematic review of their measurement properties. Age and Ageing 43: 596–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowling, Ann, Matthew Hankins, Gill Windle, Claudio Bilotta, and Robert Grant. 2013. A short measure of quality of life in older age: The performance of the brief Older People’s Quality of Life questionnaire (OPQOL-brief). Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics 56: 181–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burack, Orah R., Audrey S. Weiner, Joann P. Reinhardt, and Rachel A. Annunziato. 2012. What matters most to nursing home elders: Quality of life in the nursing home. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 13: 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, Ashleigh, Helen Hall, and Beverley Copnell. 2016. A guide to writing a qualitative systematic review protocol to enhance evidence-based practice in nursing and health care. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing 13: 241–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carcavilla González, Nuria, Juan J. García Meilán, Juan Carro Ramos, Israel Martínez Nicolás, and Thide E. Llorente Llorente. 2021. Development of a subjective quality of life scale in nursing homes for older people (CVS-R). Revista Española de Salud Pública 95: e202102020. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, Yinfei, Christine A. Mueller, Fang Yu, Kristine M. Talley, and Tetyana P. Shippee. 2021. The Relationships of Nursing Home Culture Change Practices With Resident Quality of Life and Family Satisfaction: Toward a More Nuanced Understanding. Research on Aging 44: 174–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godin, Judith, Janice Keefe, E. Kevin Kelloway, and John P. Hirdes. 2015. Nursing home resident quality of life: Testing for measurement equivalence across resident, family, and staff perspectives. Quality of Life Research 24: 2365–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, Maria J., and Andrew Booth. 2009. A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information and Libraries Journal 26: 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugan, Gørill, Jorunn Drageset, Beate André, Kamile Kukulu, James Mugisha, and Britt Karin S. Utvær. 2020. Assessing quality of life in older adults: Psychometric properties of the OPQoL-brief questionnaire in a nursing home population. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 18: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johs-Artisensi, Jennifer L., Kevin E. Hansen, and Douglas M. Olson. 2020. Qualitative analyses of nursing home residents’ quality of life from multiple stakeholders’ perspectives. Quality of Life Research 29: 1229–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, Rosalie A., Kristen C. Kling, Boris Bershadsky, Robert L. Kane, Katherine Giles, Howard B. Degenholtz, Jiexin Liu, and Lois J. Cutler. 2003. Quality of life measures for nursing home residents. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences 58: 240–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kloos, Noortje, Hester R. Trompetter, Ernst T. Bohlmeijer, and Gerben J Westerhof. 2019. Longitudinal associations of autonomy, relatedness, and competence with the well-being of nursing home residents. The Gerontologist 59: 635–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kmet, Leanne M., Linda S. Cook, and Robert C. Lee. 2004. Standard Quality Assessment Criteria for Evaluating Primary Research Papers from a Variety of Fields. Alberta: Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research. [Google Scholar]

- Kohl, Christian, Emma J. McIntosh, Stefan Unger, Neal R. Haddaway, Steffen Kecke, Joachim Schiemann, and Ralf Wilhelm. 2018. Online tools supporting the conduct and reporting of systematic reviews and systematic maps: A case study on CADIMA and review of existing tools. Environmental Evidence 7: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laybourne, Anne, Penny Rapaport, and Gill Livingston. 2021. Long-term implementation of the Managing Agitation and Raising QUality of lifE intervention in care homes: A qualitative study. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 36: 1252–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Diana Tf, Doris Sf Yu, and Alice Nl Kwong. 2009. Quality of life of older people in residential care home: A literature review. Journal of Nursing and Healthcare of Chronic Illness 1: 116–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Yang-Tzu, Pei-En Chen, Chia-Yu Liu, Wu-Hsiung Chien, and Tao-Hsin Tung. 2021. The Association between Quality of Life and Nursing Home Facility for the Elderly Population: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Gerontology 15: 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maenhout, Annelies, Elise Cornelis, Dominique Van de Velde, Valerie Desmet, Ellen Gorus, Lien Van Malderen, Ruben Vanbosseghem, and Patricia De Vriendt. 2020. The relationship between quality of life in a nursing home and personal, organizational, activity-related factors and social satisfaction: A cross-sectional study with multiple linear regression analyses. Aging & Mental Health 24: 649–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, Marita, Jessica Byers, Lucy Busija, David Mellor, Michelle Bennett, and Elizabeth Beattie. 2021. How important are choice, autonomy, and relationships in predicting the quality of life of nursing home residents? Journal of Applied Gerontology 40: 1743–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, Roger, Daniel Drewniak, Torsten Hovorka, and Liane Schenk. 2019. Questioning the questionnaire: Methodological challenges in measuring subjective quality of life in nursing homes using cognitive interviewing techniques. Qualitative Health Research 29: 972–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, David, Alessandro Liberati, Jennifer Tetzlaff, and Douglas G. Altman. 2009. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine 151: 264–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nordin, Susanna, Kevin McKee, Helle Wijk, and Marie Elf. 2017. The association between the physical environment and the well-being of older people in residential care facilities: A multilevel analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing 73: 2942–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, Matthew J., Joanne E. McKenzie, Patrick M. Bossuyt, Isabelle Boutron, Tammy C. Hoffmann, Cynthia D. Mulrow, Larissa Shamseer, Jennifer M. Tetzlaff, Elie A. Akl, Sue E. Brennan, and et al. 2021. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramesona, Bayu Anggileo, and Surasak Taneepanichskul. 2018. Factors influencing the quality of life among Indonesian elderly: A nursing home-based cross-sectional survey. Journal of Health Research 32: 326–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riesenberg, Lee Ann, and Ellen M. Justice. 2014a. Conducting a successful systematic review of the literature, part 1. Nursing 44: 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riesenberg, Lee Ann, and Ellen M. Justice. 2014b. Conducting a successful systematic review of the literature, part 2. Nursing 44: 23–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, Amy Restorick, and Karen J. Ishler. 2018. Family involvement in the nursing home and perceived resident quality of life. The Gerontologist 58: 1033–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, Carol D. 1991. Possible selves in adulthood and old age: A tale of shifting horizons. Psychology and Aging 6: 286–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenk, Liane, Roger Meyer, Anja Behr, Adelheid Kuhlmey, and Martin Holzhausen. 2013. Quality of life in nursing homes: Results of a qualitative resident survey. Quality of Life Research 22: 2929–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scocco, Paolo, and Mario Nassuato. 2017. The role of social relationships among elderly community-dwelling and nursing-home residents: Findings from a quality of life study. Psychogeriatrics 17: 231–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stern, Cindy, Zoe Jordan, and Alexa McArthur. 2014. Developing the review question and inclusion criteria. AJN The American Journal of Nursing 114: 53–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Straker, Jane K., Karl Chow, Karel Kalaw, and Xi Pan. 2011. Implementation of the 2010 Ohio Nursing Home Family Satisfaction Survey Final Report. Oxford: Scripps Gerontology Center. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, James, and Angela Harden. 2008. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Mededical Research Methodology 8: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Biljon, Lizanlé, and Vera Roos. 2015. The nature of quality of life in residential care facilities: The case of white older South Africans. Journal of Psychology in Africa 25: 201–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Biljon, Lizanlé, Vera Roos, and Karel Botha. 2015. A conceptual model of quality of life for older people in residential care facilities in South Africa. Applied Research in Quality of Life 10: 435–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHOQOL Group. 1998. Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. Psychological Medicine 28: 551–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe. 2013. Measurement of and Target-Setting for Well-Being: An Initiative by the WHO Regional Office for Europe: Second Meeting of the Expert Group: Paris, France, 25–26 June 2012. Genève: World Health Organization and København: Regional Office for Europe. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Menglian, Yang Yang, Dan Zhang, Xia Zhao, Yaoyao Sun, Hui Xie, Jihui Jia, Yonggang Su, and Yuqin Li. 2018. Association between social support and health-related quality of life among Chinese rural elders in nursing homes: The mediating role of resilience. Quality of Life Research 27: 783–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Dongjuan, Jie Gao, Liqin Chen, Huanyu Mou, Xiaorong Wang, Jiying Ling, and Kefang Wang. 2019. Development of a quality of life questionnaire for nursing home residents in mainland China. Quality of Life Research 28: 2289–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Search String | Database or Further Sources (Results) |

|---|---|

| TITLE((“nursing home” OR “care home” OR “retirement home” OR “old’s people home” OR “home for the elderly” OR “residency for the elderly” OR “residential care”) AND (“quality of life” OR “life quality” OR “well-being”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (SUBJAREA, “MEDI”) OR LIMIT-TO (SUBJAREA, “NURS”) OR LIMIT-TO (SUBJAREA, “SOCI”) OR LIMIT-TO (SUBJAREA, “PSYC”) OR LIMIT-TO (SUBJAREA, “HEAL”) OR LIMIT-TO (SUBJAREA, “MULT”)) AND (PUBYEAR > 2010 AND (PUBYEAR < 2022)) | Scopus (402) |

| (TI = (((“nursing home” OR “care home” OR “retirement home” OR “old’s people home” OR “home for the elderly” OR “residency for the elderly” OR “residential care”) AND (“quality of life” OR “life quality” OR “well-being”)))) AND PY = (2011–2021) | Web of Science (322) |

| In title: (“nursing home” OR “care home” OR “retirement home” OR “old’s people home” OR “home for the elderly” OR “residency for the elderly” OR “residential care”) AND (“quality of life” OR “life quality” OR “well-being”) Limit: [between 2011 AND 2021] | Wiley online library (48) |

| ((“nursing home”[Title] OR “care home”[Title] OR “retirement home”[Title] OR “old’s people home”[Title] OR “home for the elderly”[Title] OR “residency for the elderly”[Title] OR “residential care”[Title]) AND (“quality of life”[Title] OR “life quality”[Title] OR “well-being”[Title])) AND (“1 January 2011”[Date-Publication]: “31 December 2021”[Date-Publication]) | PubMed (231) |

| ti(“nursing home” OR “care home” OR “retirement home” OR “old’s people home” OR “home for the elderly” OR “residency for the elderly” OR “residential care”) AND ti(“quality of life” OR “life quality” OR “well-being”) [exclude “press”] Limit: [between 2011 AND 2021] | ProQuest in all databases (575): Medline (226) APA PsycInfo (132) Health & Medical Collection (122) Nursing & Allied Health Premium (106) Publicly Available Content Database (72) Psychology Database (61) Sociological Abstracts (45) Social Services Abstracts (30) Sociological Abstracts (25) ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global (19) Others (6) |

| ti(“nursing home” OR “care home” OR “retirement home” OR “old’s people home” OR “home for the elderly” OR “residency for the elderly” OR “residential care”) AND ti(“quality of life” OR “life quality” OR “well-being”) Limit: [between 2011 AND 2021] | EBSCOhost in all databases (498): Medline (228) CINAHL Complete (207) Global Health (27) CAB Abstract (17) Others (19) |

| ((title:”nursing home”) OR (title:”care home”) OR (title:”retirement home”) OR (title:”old’s people home”) OR (title:”home for the elderly”) OR (title:”residency for the elderly”) OR (title:”residential care”)) AND ((title:”quality of life”) OR (title:”life quality”) OR (title:”well-being”)) Limit: [between 2011 AND 2021] | Emerald (6) |

| Question | Carcavilla González et al. (2021) | Godin et al. (2015) | Xu et al. (2019) | Haugan et al. (2020) | Burack et al. (2012) | Duan et al. (2021) | Kloos et al. (2019) | McCabe et al. (2021) | Maenhout et al. (2020) | Nordin et al. (2017) | Pramesona and Taneepanichskul (2018) | Roberts and Ishler (2018) | Scocco and Nassuato (2017) | Wu et al. (2018) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 8 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 9 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 10 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| 11 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 12 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| 13 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 14 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Score | 18 | 20 | 22 | 21 | 18 | 22 | 17 | 19 | 22 | 19 | 18 | 22 | 19 | 20 |

| Max. | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 |

| % | 82% | 91% | 100% | 95% | 82% | 100% | 77% | 86% | 100% | 86% | 82% | 100% | 86% | 91% |

| Question | Adra et al. (2015) | Adra et al. (2017) | Johs-Artisensi et al. (2020) | Meyer et al. (2019) | Schenk et al. (2013) | van Biljon et al. (2015) | van Biljon and Roos (2015) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| 6 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 7 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 9 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 10 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Score | 15 | 15 | 16 | 16 | 15 | 16 | 16 |

| Max. | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| % | 75% | 75% | 80% | 80% | 75% | 80% | 80% |

| Authors/Year and Title | Country/Sample | Aim | Classification | Methodology/Design | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carcavilla González et al. (2021) Development of a subjective quality of life scale in nursing homes for older people (CVS-R) | (Spain) n = 99 (development, 36.4% professionals, 30.3% residents, 33.33% family members) n = 225 (validity, 62% professionals, 23% residents, 14% family members) | To develop and validate a QoL questionnaire for nursing home residents in Spain | QoL and WB models or scales | Literature review. Pilot study. Factorial analysis of principal components, evaluation of the internal consistency for its reliability (Cronbach’s alpha coefficient) | A validated and reliable questionnaire to measure QoL in NHs, contemplating the perception of residents, family members, and professionals (with 27 questions and 9 dimensions) |

| Godin et al. (2015) Nursing home resident quality of life: testing for measurement equivalence across resident, family, and staff perspectives | (Canada) n = 319 (residents), n = 397 (family members), n = 862 (staff), n = 23 (nursing homes) | To explore the factor structure of the interRAI self-report nursing home QoL survey and to develop a measure that will allow researchers to compare predictors of QoL across resident, family, and staff perspectives | QoL and WB models or scales | Exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis | A model with a four-factor structure (i.e., care and support, food, autonomy, and activities) across resident, family, and staff perspectives. A tool that researchers can use to compare predictors of QoL |

| Xu et al. (2019) Development of a quality of life questionnaire for nursing home residents in mainland China | (mainland China) n = 176 residents (development) n = 371 residents (validation) | To develop and validate a QoL questionnaire for nursing home residents in mainland China | QoL and WB models or scales | Exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis. Descriptive statistics. Resident interviews, literature reviews, expert panels, and pilot studies. | A nursing home QoL questionnaire with satisfactory reliability and validity, it has 9 domains and 38 items including physical health, food enjoyment, security, environmental comfort, autonomy, meaningful activity, interrelationships, family relationships, and mood |

| Adra et al. (2015) Constructing the meaning of quality of life for residents in care homes in the Lebanon: Perspectives of residents, staff and family | (Lebanon) n = 20 (residents), n = 8 (family caregivers), n = 11 (care staff), across 2 nursing homes | To explore the perspectives of QoL for a sample of older residents, care staff and family caregivers, so far little is known about its meanings from an Arabic cultural perspective and context | Stakeholders’ views and perceptions of QoL and WB | Category analysis. Analytical interpretation | Four categories emerged: maintaining family connectedness; engaging in worthwhile activities; maintaining and developing significant relationships; and maintaining and practicing spiritual beliefs |

| Adra et al. (2017) Nursing home quality of life in the Lebanon | (Lebanon) n = 20 (residents), n = 8 (family caregivers), n = 11 (staff), across 2 nursing homes | To explore perceptions, perspectives, and meaning of QoL for a sample of older residents, care staff, and family caregivers in two nursing homes in Lebanon | Stakeholders’ views and perceptions of QoL and WB | Category analysis | Three distinct but interrelated properties of QoL emerged from this process: “maintaining self”, “maintaining identity”, and “maintaining continuity”. The dynamics that exist within and between each of these properties provide an indicator about shared and distinct meanings and the implications for care practice |

| Johs-Artisensi et al. (2020) Qualitative analyzes of nursing home residents’ quality of life from multiple stakeholders’ perspectives | (US) n = 138 (residents), n = 138 (nursing assistants), n = 46 (social workers), n = 46 (activities directors), n = 46 (administrators) | To identify contributory factors to resident QoL, as well as analyze areas of commonality in qualitative responses | Stakeholders’ views and perceptions of QoL and WB | Multi-step, inductive approach in order to conduct a thematic analysis to assess patterns of meaning within the datasets from the interview questions | Confirm previous research findings of resident-centered care contributing to residents QoL and distinguish between various stakeholders’ perspectives within the nursing home settings. Contributory factors: Activities, Autonomy/Respect, Comfortability/Environment, Contributory Service, Emotional Well-Being, Familial Communication, Food/Drink, Quality of Care, Sense of Community, Spirituality/Religion, Staff and Resident Relationships. Staff and Resident Relationships were important to all stakeholders. Greater alignment between nursing assistants and residents. Residents did not rank Quality of Care as one of their top contributory factors, but staff and management all included the |

| Meyer et al. (2019) Questioning the Questionnaire: Methodological Challenges in Measuring Subjective Quality of Life in Nursing Homes Using Cognitive Interviewing Techniques | (Germany) n = 16 residents, across 4 care homes | To analyze how older adults in residential care facilities interpret and process response stimuli received from a questionnaire on subjective QoL. To gain methodological insights into the way a survey instrument on subjective QoL can adequately represent individual ratings, as well as expectations regarding different aspects of QoL | Stakeholders’ views and perceptions of QoL and WB | Analysis conducted by consensus using cognitive interviewing techniques within a qualitative validation study | Development of QUISTA assessment tool (QoL in Residential Care). Subjective QoL as a multidimensional construct that includes aspects considered important to nursing home residents. The operationalization of these dimensions as questions based on QoL dimensions reconstructed from their original form (the residents themselves described and reflected on what constitutes dimensions of subjective QoL). The comparison of subjective assessments of QoL aspects (the “actual” state) with personal preferences in relation to the same aspects (the “desired” state) |

| Schenk et al. (2013) Quality of life in nursing homes: Results of a qualitative resident survey | (Germany) n = 42 residents across 8 nursing homes | To identify dimensions of life that nursing home residents perceive as having a particular impact on their overall QoL | Stakeholders’ views and perceptions of QoL and WB | The interviews analyzed using the documentary method | Ten central dimensions of subjective QoL were derived from the interview data: social contacts, self-determination and autonomy, privacy, peace and quiet, variety of stimuli and activities, feeling at home, security, health, being kept informed, and meaningful/enjoyable activity. Some of these dimensions are multifaceted and have further subdimensions |

| van Biljon et al. (2015) A Conceptual Model of Quality of Life for Older People in Residential Care Facilities in South Africa | (South Africa) n = 19 residents across 3 nursing homes | How do older adults conceptualize their QoL in residential care facilities in terms of cause-and-effect relations between domains of QoL, based on the six domains deriving from the work of van Biljon and Roos. To obtain a conceptual model of QoL that is reflective of the system dynamics of how older adults construct their QoL in residential care facilities | Stakeholders’ views and perceptions of QoL and WB | Interactive Qualitative Analysis | A conceptual model of QoL for older adults in residential care facilities, with 6 domains (spirituality, health, meaningfulness, sense of place, autonomy, and relationships). The domains with the power to reinforce this system were spirituality and autonomy. The domain of spiritually has a cognitive and behavioral transformational ability and has the potential to constructively assist older adults with emotional regulation, health aspects, and also to deal with adversities. Furthermore, autonomy has the potential to give older adults a sense of self-esteem and purpose which will reinforce their ability to live meaningful lives |

| van Biljon and Roos (2015) The nature of quality of life in residential care facilities: The case of White older South Africans | (South Africa) n = 41 residents across 4 nursing homes | To explore QoL as perceived by older adults residing in residential care facilities in South Africa | Stakeholders’ views and perceptions of QoL and WB | Narrative reflections on QoL in journals. Qualitative research to explore and describe participants’ understanding and interpretation of QoL. Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis to analyze the data | The resident older adult South Africans regard QoL as a spiritually informed worldview of life events, coping with challenges and being mindful of others. The residents perceived QoL to include proximity and quality and reciprocity with others |

| Haugan et al. (2020) Assessing quality of life in older adults: Psychometric properties of the OPQoL-brief questionnaire in a nursing home population | (Norway) n = 188 residents across 27 nursing homes | To test the psychometrical properties of the OPQoL-brief questionnaire among cognitively intact nursing home residents | Relationships between QoL factors | Principal component analysis and confirmative factor analysis | Evidence related to the dimensionality, reliability, and construct validity; all of the items considered interrelated measurement properties. Of the original 13 items, 5 showed low reliability and validity; excluding these items revealed a good model fit for the one-dimensional 8-item measurement model, showing good internal consistency, and validity for these 8 items (anxiety, depression, self-transcendence, meaning-in-life, nurse-patient interaction, and joy-of-life) |

| Burack et al. (2012) What matters most to nursing home elders: Quality of life in the nursing home | (US) n = 62 residents across 3 nursing homes | To determine those components of nursing home QoL that are associated with older adults’ satisfaction so as to provide direction in the culture change journey | Predictors of QoL | A cross-sectional study using a survey administered face-to-face. Regression analysis | After accounting for cognitive and physical functioning, among the QoL domains, dignity, spiritual well-being, and food enjoyment remained predictors of overall nursing home satisfaction. Additionally, dignity remained a significant predictor of older adults’ satisfaction with staff |

| Duan et al. (2021) The Relationships of Nursing Home Culture Change Practices With Resident Quality of Life and Family Satisfaction: Toward a More Nuanced Understanding | (US) n = 102 administrators | To test the domain-specific relationships of culture change practices with resident QoL and family satisfaction, and to examine the moderating effect of small-home or household models on these relationships | Relationships between QoL factors | Descriptive statistics to describe NH characteristics, culture change domain scores, resident QoL scores, and family satisfaction scores. A linear regression model, separately, for the summary scores of resident QoL and family satisfaction, and their domain scores | Culture change operationalized through physical environment transformation, staff empowerment, staff leadership, and end-of-life care was positively associated with at least one domain of resident QoL and family satisfaction, while staff empowerment had the most extensive effects. Implementing small-home and household models had a buffering effect on the positive relationships between staff empowerment and the outcomes |

| Kloos et al. (2019) Longitudinal Associations of Autonomy, Relatedness, and Competence With the Well-being of Nursing Home Residents | (Netherlands) n = 128 physically frail residents in somatic long-term care units at 4 nursing homes | To test the longitudinal relations of the satisfaction of three basic psychological needs (satisfying nursing home residents’ needs for autonomy, relatedness, and competence) to the subjective well-being of nursing home residents and to determine whether a balance among the satisfaction of the three needs is important for well-being | Relationships between WB factors | Correlations between subscales. Hierarchical multiple regression analysis | All three needs (autonomy, relatedness, and competence) were related to both well-being measures over time, although autonomy had the strongest relationships. Only autonomy and competence were uniquely associated with depressive feelings, and only autonomy was uniquely associated with life satisfaction. The need satisfaction balance score was related to well-being independent of the autonomy and relatedness scores |

| McCabe et al. (2021) How Important Are Choice, Autonomy, and Relationships in Predicting the Quality of Life of Nursing Home Residents? | (Australia) n = 604 residents across 33 nursing homes | To evaluate the contribution of resident choice, as well as the staff–resident relationship, to promoting resident QoL | Predictors of QoL | Hierarchical regression | Two of the four predictor variables (resident choice over socializing and the staff–resident relationship) significantly contributed to resident QoL |

| Maenhout et al. (2020) The relationship between quality of life in a nursing home and personal, organizational, activity-related factors and social satisfaction: a cross-sectional study with multiple linear regression analyses | (Belgium) n = 171 cognitively healthy residents across 73 nursing homes | To investigate QoL in nursing home residents and the relationship with personal, organizational, activity-related factors, and social satisfaction | Relationships between QoL factors | Cross sectional survey. Multiple linear regression (forward stepwise selection) | Results suggest that a higher QoL in nursing homes can be pursued by strategies to prevent depression and to improve nursing home residents’ subjective perception of health (e.g., offering good care) and social networking |

| Nordin et al. (2017) The association between the physical environment and the well-being of older people in residential care facilities: A multilevel analysis | (Sweden) n = 200 residents across 20 nursing homes | To investigate the associations between the quality of the physical environment and the psychological and social well-being of older adults living in residential care facilities | Relationships between WB factors | A cross-sectional survey of care facilities. Multilevel analysis | Cognitive support in the physical environment was associated with residents’ social well-being, after controlling for independence and perceived care quality. No significant association was found between the physical environment and residents’ psychological well-being |

| Pramesona and Taneepanichskul (2018) Factors influencing the quality of life among Indonesian elderly: A nursing home-based cross-sectional survey | (Indonesia) n = 181 residents across 3 nursing homes | To examine the level of QoL and factors influencing QoL amongst older adult NH residents in Indonesia | Predictors of QoL | Descriptive statistics. Multivariate linear regression | Perceived adequacy of care and reason for living in an NH were highlighted as predictors of QoL amongst older adult NH residents |

| Roberts and Ishler (2018) Family Involvement in the Nursing Home and Perceived Resident Quality of Life | (US) n = 14,979 family members across 839 nursing homes | To study the relationship between family involvement and family perceptions of nursing home residents’ QoL | Predictors of QoL | Hierarchical linear modelling was used to examine the association between family involvement and other predictors with perceived resident QoL | Although most of the variability in family member perceptions of resident QoL was observed at the individual level (residents and families), characteristics of the facilities were also significantly associated with perceived resident QoL. Family involvement was a strong predictor of perceived resident QoL: families who visited frequently and provided more help with personal care perceived lower resident QoL, while those who communicated frequently with facility staff had higher perceptions of resident QoL. The negative association between helping with more personal care and perceiving lower resident QoL was attenuated when family members communicated more regularly with facility staff. However, as family member age increased, the positive association between communication with facility staff and resident QoL diminished. Family members who are spouses, older, non-White, and highly educated perceived resident QoL as lower |

| Scocco and Nassuato (2017) The role of social relationships among elderly community-dwelling and nursing-home residents: findings from a quality of life study | (Italy) n = 207 older adults (n = 135 community-dwelling residents, n = 72 nursing home residents across 2 nursing homes) | To compare World Health Organization QoL brief version (WHOQOL-BREF) scores of the community of older adult dwelling residents and nursing home residents, based on the assumption that QoL, particularly social relationships, may be perceived differently according to residential setting | Relationships between QoL factors | Linear regression model. Logistic regression model | Depressive symptoms correlated with low scores in all WHOQOL-BREF domains. The variables that correlated with living conditions in a nursing home were older age, male gender, lower physical domain scores, and higher social relationship scores |

| Wu et al. (2018) Association between social support and health-related quality of life among Chinese rural elders in nursing homes: the mediating role of resilience | (China) n = 205 residents across 5 nursing homes | To confirm the relationship between social support and health-related QoL (HRQOL) among rural Chinese older adults in nursing homes, and to examine the mediating role of resilience in the impact of social support on HRQOL | Relationships between QoL factors | Cross sectional study. Statistical analysis. Correlation matrix, with Pearson’s coefficients for continuous variables or Spearman’s coefficients for nominal and ordinal variables. Mediation analysis | Social support was positively related to QoL among older adults. In addition, the mediating role of resilience in the relationship between social support and QoL is confirmed |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rodríguez-Martínez, A.; De-la-Fuente-Robles, Y.M.; Martín-Cano, M.d.C.; Jiménez-Delgado, J.J. Quality of Life and Well-Being of Older Adults in Nursing Homes: Systematic Review. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 418. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12070418

Rodríguez-Martínez A, De-la-Fuente-Robles YM, Martín-Cano MdC, Jiménez-Delgado JJ. Quality of Life and Well-Being of Older Adults in Nursing Homes: Systematic Review. Social Sciences. 2023; 12(7):418. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12070418

Chicago/Turabian StyleRodríguez-Martínez, Antonia, Yolanda María De-la-Fuente-Robles, María del Carmen Martín-Cano, and Juan José Jiménez-Delgado. 2023. "Quality of Life and Well-Being of Older Adults in Nursing Homes: Systematic Review" Social Sciences 12, no. 7: 418. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12070418

APA StyleRodríguez-Martínez, A., De-la-Fuente-Robles, Y. M., Martín-Cano, M. d. C., & Jiménez-Delgado, J. J. (2023). Quality of Life and Well-Being of Older Adults in Nursing Homes: Systematic Review. Social Sciences, 12(7), 418. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12070418