Abstract

The literature on lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans*, intersex, and queer (LGBTIQ) politics has established the interplay between domestic and transnational norms and political tactics. However, knowledge about how local LGBTIQ activists understand, negotiate, and employ transnational LGBTIQ campaigns and tactics over time remains limited. This article builds on literature on the dynamics between national and transnational LGBTIQ politics. Based on interviews with Cypriot LGBTIQ activists, it examines how they adapt their perceptions and employments of LGBTIQ activism and politics when the transnational LGBTIQ movement interacts with local norms around gender and sexuality, and what the impact of this interaction is on the boundaries of LGBTIQ in-group exclusion and inclusion. The analysis of the interview material identifies three approaches toward transnational LGBTIQ politics that participants express over time: Ambivalence toward, acclamation of, and resistance toward transnational LGBTIQ politics. I argue that these different approaches show that the dynamics between national and transnational LGBTIQ activism and politics are not static and that the relationship between “norm” and “queer” is both messy and productive. I further argue that activists’ understandings, negotiations, and employments of transnational LGBTIQ campaigns and tactics in contentious contexts may reinforce and/or challenge national LGBTIQ politics’ normativization and queer emancipatory politics. Therefore, beyond contributing to discussions about the national–transnational relationship in LGBTIQ politics, the article demonstrates the importance of studying LGBTIQ activists’ views for gaining a well-rounded understanding of this issue.

1. Introduction

Queerness and queer are not about the heroic and triumphant distancing from the normative … Such positionalities are never static, they are always shifting … The architecture of social injustice is always about deciphering and confronting the vexed meeting points of various axes of difference.(Manalansan 2018, pp. 1288–89)

Differences over how we understand things and what our priorities are, are not necessarily bad … It’s essential that we continue to focus on legal and policy goals. However, I welcome the formation of more radical groups that focus on other tasks … It’s good to have multiple groups, as long as we complement, rather than undermine, each other.(VN, Accept-LGBTI Cyprus activist 2021)

Many sociologists and political scientists agree that, during the last decades, “Europe” has become a bastion of lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans*, intersex, and queer (LGBTIQ) rights and that, despite difficulties associated with particularities of national context, the Europeanization and transnationalization of LGBTIQ rights and advocacy have enabled LGBTIQ activism and the adoption of LGBTIQ law and policy at the national level (e.g., Ayoub 2013, 2015, 2016, 2019; Ayoub and Paternotte 2014; Slootmaeckers et al. 2016; Swimelar 2017).1 Others point to the power asymmetries between the European “core” and “peripheries” and argue that, in some contexts, the mainstreaming of transnational LGBTIQ campaigns and tactics has overshadowed pre-existing queer political possibilities and restricts future ones, thus contributing to forms of exclusion and relational privilege among LGBTIQs across and within national borders (e.g., Ammaturo 2014, 2015; 2017; Bilić 2016; Freude and Vergés Bosch 2020; Rahman 2013, 2014).

Despite its invaluable insights, most of the research on (trans)national LGBTIQ politics and activism in Europe tends to focus on Western and on Central and Eastern European countries, while Southern European countries remain underexamined. Studying LGBTIQ politics and LGBTIQs’ perceptions of LGBTIQ politics in contexts characterized by complex discursive intersections amidst Europeanization and other transnationalization processes that have escaped the focus of previous research, is important for our knowledge about (trans)national LGBTIQ politics and activism. It also has theoretical and practical implications for a nuanced understanding of social movements, contentious politics, and the effects of Europeanization and transnationalization processes within and across national borders (Ayoub 2016; Ayoub and Paternotte 2014; Binnie 2016). Moreover, for the most part, the existing literature focuses on specific time phases of the interaction between national LGBTIQ movements and the transnational LGBTIQ movement. However, LGBTIQ activism and politics, and the dynamics between national and transnational LGBTIQ activism and politics, are not static (Ayoub 2016; Ayoub and Chetaille 2020; Bracke 2012; Manalansan 2018). Additionally, their development is not always or necessarily linear toward substantive equality for, and horizontal equality among, all sexuality- and gender-nonconforming people, as homonationalism that extends beyond the state apparatus and manifests itself among LGBTIQ groups indicates (Mole 2017; Puar 2007, 2013; Rexhepi 2016). Furthermore, there is little empirical knowledge about how local LGBTIQ activists themselves understand, negotiate, and employ transnational LGBTIQ campaigns and tactics over time. Most research on the topic focuses on movements as the unit of analysis, while accounts of activists’ agency and the ways in which this agency shapes and is shaped by (trans)national LGBTIQ activism and politics remain scarce (Evangelista 2022; Jasper 2004; Thoreson 2012).2

Drawing on the premise set by Martin F. Manalansan IV (Manalansan 2018) in the epigraph and motivated by the LGBTIQ in-group differences referred to in the interview excerpt above, in this article, I attempt to address these gaps from the perspectives of LGBTIQ activists in Cyprus. There are many reasons that make the focus on Cyprus and on Cypriot LGBTIQ activists compelling: Cyprus is a European Union (EU) member-state at the margins of “Europe”, divided along ethnic lines and marked by colonialism, conflict, occupation, and tensions about the content and boundaries of national and “European” identity, not least in relation to nonconforming genders and sexualities. To understand long-lasting patterns of unequal power relations produced by “western/European” imperialism and colonialism and the dynamics, reach, and limits of new forms of transnational relations, such as Europeanization, it is important to focus on the contentious margins. Moreover, given that the demarcating line between “center” and “periphery” is porous, focusing on the margins can produce valuable knowledge about the “center” as well (Comaroff and Comaroff 2012, pp. 5, 46). Theory does emerge from the experience of the periphery and, to adequately understand the world on a planetary scale, the notion that knowledge produced from a position of privilege—i.e., in the “western/European” center—is universal knowledge, needs to be challenged (Connell 2007, pp. ix–x). Therefore, studying Cyprus makes an important contribution to current conversations on Europeanization/transnationalization and LGBTIQ politics.

Drawing from 100 interviews conducted from 2009 to 2022, I examine participants’ views and negotiations on, and employments of, transnational LGBTIQ campaigns and tactics, and the concomitant shaping and development of Greek-Cypriot LGBTIQ activism and politics since the late 2000s. The following research questions guide the analysis: How do local LGBTIQ activists adapt their perceptions and employments of LGBTIQ activism and politics when the transnational LGBTIQ movement mixes with local norms around gender and sexuality? And what is the impact of this interaction between the local and the transnational on the boundaries of LGBTIQ in-group exclusion and inclusion within the state? Answers to these questions are essential for understanding the processes and agency that shape the spaces in, and the ways through which minority groups in contentious contexts can pursue their political objectives. They are also significant for comprehending the opportunities and limitations of queer activism and politics (Broad 2020; Evangelista 2022; Jasper 2004; Manalansan 2018).

An in-depth qualitative analysis of the interviews identifies three approaches toward transnational LGBTIQ politics that participants express over time: Ambivalence toward, acclamation of, and resistance toward transnational LGBTIQ politics. I note participants’ positive views on transnational LGBTIQ politics and its positive impact on national LGBTIQ activism, during the early years of Greek-Cypriot LGBTIQ activism. However, I find that, in more recent years, LGBTIQ activists tend to associate transnational LGBTIQ politics with the normativization of national LGBTIQ politics and the exacerbation of LGBTIQ in-group exclusions and hierarchical differentiations based on relational privilege. Therefore, I contribute to scholarly discussions about whether and how activists’ understandings, negotiations, and employments of transnational LGBTIQ politics in contentious contexts may reinforce and/or challenge national LGBTIQ politics’ normativization and queer emancipatory politics.

Interdisciplinary in scope, the article draws from the insights of social movement, feminist, LGBT, Europeanization, and queer studies. Inspired from Rocío R. García’s (García 2020, p. 441) idea of negotiating difference in collective action as “a necessarily fraught and messy endeavor”, it highlights the often-ignored complexities of (re)constructing and labeling sexuality- and gender-nonconforming selves and others, as well as the ways in which these complexities impact LGBTIQ activism and politics. Motivated by Martin F. Manalansan IV (Manalansan 2018) and John Andrew G Evangelista’s (2022) approach to “queer” and to LGBTIQ activists’ affinities as messy, it pays attention to the national sociopolitical conditions that facilitate and/or necessitate certain employments of (trans)national LGBTIQ politics at certain points in time. Therefore, it does not treat national LGBTIQ activists or politics as fixed either in “neoliberal cooptation” or in “queer subversion” (Ayoub 2019; Broad 2020; Evangelista 2022; García 2020). Additionally, it does not employ the terms “Europe”, “west”, or the other pole of the dichotomy that these terms instigate—i.e., “rest” and “periphery”—as essential geographical entities. Problematizing the division and hierarchization of the world, and interrogating the homogenization of regions and historical experiences, it treats these concepts as non-monolithic, fluid, and permeable political, social, economic, and cultural constructs, and as discursive categories that it aims to question (Lewis and Wigen 1997; Puar 2007, 2013; Said 1978; Szulc 2022).

I begin with a brief outline of the predominant literature on the relationship between national and transnational LGBTIQ politics and activism and point to some of its oversights. I then provide an overview of the development of Greek-Cypriot LGBTIQ politics and activism. Next, I describe the employed research methods before presenting the analysis of the interview material. I conclude with a summary of the article’s findings and implications and suggest avenues for future research.

2. On (Trans)national LGBTIQ Politics and Activism: Normativity and Resistance in a Changing (Trans)national Landscape

Europeanization and other transnationalization processes may further complicate the relationship between nationalism, gender, and sexuality, and further politicize LGBTIQ issues. Therefore, particularly as an object of study in the context of EU expansion and of concomitant Europeanization and other transnationalization processes, the relationship between transnational and national LGBTIQ politics and activism has spurred a plethora of research. A considerable part of this research argues that the transnationalization of LGBTIQ rights and politics has facilitated the recognition and protection of LGBTIQ rights at the national level and has created political opportunities for national and transnational LGBTIQ mobilization (e.g., Ayoub 2013, 2015, 2016, 2019; Ayoub and Paternotte 2014; Slootmaeckers et al. 2016; Swimelar 2017). Although the Europeanization/transnationalization of LGBTIQ issues has not always and everywhere been an uncomplicated process, it has facilitated LGBTIQ rights recognition and mobilization at the national level, as well as the formation of alliances and the creation of solidarity across borders. Moreover, transnational non-governmental organizations (NGOs) have played a decisive role in this process—and particularly in norm visibility and diffusion (Ayoub 2014, 2016)—and, therefore, to the successes of national LGBTIQ organizations (Ayoub and Chetaille 2020; Holzhacker 2012; Paternotte and Seckinelgin 2015).

However, another part of this literature (also) argues that the transnationalization of LGBTIQ politics and rights discourses does not lead to, and even inhibits, positive sociocultural change at the national level, while it also restricts grassroots LGBTIQ agency (e.g., Ammaturo 2014, 2015, 2017; Bilić 2016; Freude and Vergés Bosch 2020; Rahman 2013, 2014). The transnationalization of the LGBTIQ movement has facilitated legal victories within national contexts, particularly in Europe. Nevertheless, it has also led to LGBTIQ identities becoming less politicized, shifted national LGBTIQ movements’ goals toward rights, and rendered LGBTIQ movements assimilationist (Butterfield 2016, 2020; Kollman 2013; Rao 2014). Moreover, the mainstreamization and normalization of LGBTIQ politics tend to favor those in the mainstream, construct and reify notions of homonormativity and transnormativity, and therefore exclude the other “others” at the margins (Colpani and Habed 2014; Rahman 2013, 2014; Richardson 2005).3

Based on their employment on the ground, Europeanization/transnationalization and their accompanying discourses and activism paradigms may become elitist and exclusionary, as they may replicate colonial discourses and logics that construct national sexuality- and gender-nonconforming communities as lacking agency, and these communities’ cultures as “backward” (Bilić 2016; Evangelista 2022; Freude and Vergés Bosch 2020; Rao 2014). As Laura Eigenmann (2022, p. 96) explains, “LGBTI rights now often figure as a symbol for states and societies that wish to portray themselves as modern and progressive”. This is often the result of state efforts and national politics: Nationalist political forces portray “others” as “backward” and as carriers of monocultures that are incompatible with the “European/western” value of sexual and gender diversity, to keep them outside the borders of “civilized” “Europe/west” (Ammaturo 2014, 2015, 2017; Klapeer 2017; Kulpa 2014; Puar 2007, 2013). In this way, LGBTIQ rights become part of the EU’s identity construction against both external and internal enemies and challengers—including nationalists and Eurosceptics who oppose LGBTIQ rights—and a self-affirmation instrument (Eigenmann 2022; Slootmaeckers 2019). As Christine M. Klapeer (2017, p. 44) argues, “LGBTIQ inclusive development strategies have not only been enabled by a ‘dangerous liaison’ with homo(trans)nationalist norms and policies but are also at risk to reinstate tropes of an EUropean sexual exceptionalism”. Furthermore, numerous analyses show that, in some contexts, the mainstreaming of transnational LGBTIQ campaigns and tactics has contributed to the creation of forms of exclusion and relational privilege among national LGBTIQs (e.g., Bilić 2016; Kulpa 2014; Kulpa and Mizielińska 2016; Rahman 2013, 2014). Some sexuality- and gender-nonconforming individuals constitute themselves as LGBTIQs both by adopting “western”/“European” transnational discourses and identities, and by differentiating themselves from sexuality- and gender-nonconforming “others”, whom they perceive as inferior (Bracke 2012; Rao 2014).

This literature yields invaluable knowledge about how national LGBTIQ politics are shaped in the context of Europeanization and other transnationalization processes, and concurs that these processes have had varied and mixed effects both at the national and the transnational level in relation to LGBTIQ politics. Nonetheless, research on the impact of the mainstreaming of transnational LGBTIQ campaigns and tactics in contexts in the margins of Europe, and particularly in the Southern European context, remains limited, as remains research that makes LGBTIQ activists themselves and their perspectives its focus. Research with sexuality- and gender-nonconforming people outside the “west” and the EU “core” contributes to these people’s empowerment, highlights the contingent ways in which agency and politics form and function, and helps in decolonizing and denormativizing LGBTIQ studies and politics (Jasper 2004; Namaste 2005, 2015; Pereira 2019). It is also necessary for interrogating the asymmetries not only of Europeanization and transnationalization, but also of which interpretations of LGBTIQ politics and of sexuality- and gender-nonconforming existence count as legitimate within specific contexts, at the transnational level, and within scholarship (Aizura et al. 2014; Blackwood 2008; Chiang and Wong 2016).

Although still scarce, research on LGBTIQ politics and activism that focuses on activists’ perspectives is increasing and highlights the importance of activists’ understandings and agency in the shaping of (trans)national LGBTIQ activism and politics. For example, Polletta et al. (2021) study the consequences of movement professionalization and find that the introduction of expert discourses within movements, and their employment and reiteration by activists, leads to remaking political problems into technical ones. Furthermore, as the authors explain, “[these] discourses make certain experiences normative in a way that marginalizes other experiences and those speaking for them” (ibid., p. 70; see also Hindman 2019). García (2020) examines difference in collective action and describes its negotiation “as a necessarily fraught and messy endeavor” for strengthening social justice movements. The author challenges the position that sees difference as an obstacle in collective mobilization and argues that “activisms attuned to difference can produce more flexible, dynamic collective action capable of tackling converging oppressions and privileges” (ibid., p. 441). Therefore, García (ibid., p. 443) concludes by advocating for what they term “politicmaking” and they define “as the ongoing creation of ways of making sense of and being in politics—a form of intersectional sensibility—that make visible the intersectional dynamics rendered invisible in mainstream, nonintersectional politics”.

Evangelista (2022) focuses on national LGBTIQ activism and politics outside the “west”. The author highlights the political, material, and ideological exigencies confronting LGBTIQ activists that compel them not to succumb to, but to deploy the imperial narrative of “western/European” sexual exceptionalism. The author distances themselves from what they describe as “a perfunctory notion” of labeling LGBTIQ movements “as essentially complicit to the Western liberal empire” and to homonationalism, and argues that queer is messy (ibid., pp. 348–49). Namely, transgression and normativity are not the two opposite/opposing poles of sexuality- and gender-nonconformity activism and politics. Rather, as Manalansan (2018, p. 1288) explains, “norm and queer are not easily indexed or separable but are constantly colliding, clashing, intersecting and reconstituting;” a mess that generates possibilities. Therefore, Evangelista (2022) concludes that, depending on national context particularities and the opportunities and difficulties with which they are faced, national LGBTIQ activists may both deploy and/or disrupt neoliberal, normalized, institutionalized, professionalized, and NGOized LGBTIQ politics.4

3. Queer in Cyprus? The Cypriot Context

Aiming to contribute to this body of research, this article zooms in on Cypriot LGBTIQ activists’ perspectives and examines how they understand, negotiate, and employ transnational LGBTIQ politics over time whilst located between national and transnational circuits of power and discourse, thus concomitantly shaping national LGBTIQ politics and activism.

LGBTIQ rights and politics represent an increasingly politicized and contentious issue in domestic politics in several contexts, while nationalist powers that derive their strength from bolstering binary and exclusionary discourses of sexuality, gender, race, ethnicity, and citizenship are on the rise (Ayoub and Page 2020; Ayoub et al. 2021; Paternotte 2018). In nationalist contexts and amidst the rise of the far-right and anti-gender politics and the neoliberal cooptation of LGBTIQ politics, belonging tends to be defined in juxtaposition to exclusion and specific practices, experiences, and identities—including sexual and gender identities—are privileged and rewarded through the sanctioning of others (e.g., Chasin 2000; Mole 2017; Paternotte and Kuhar 2018). As Phillip M. Ayoub, Douglas Page, and Sam Whitt (Ayoub et al. 2021, p. 470) explain, the “us”-versus-“them” distinction in terms of gender and sexual identities tends to be more prominent in places characterized by intense debates about preserving an “authentic” national identity, which some believe to be threatened by fluid concepts that are unconfined to boarders, such as non-normative sexualities and genders. Cyprus, whose historic turns have caused a profound crisis in Cypriot identity, is an example of this place (Kamenou 2016).

The beginnings of the Greek-Cypriot LGBTIQ movement can be traced to the activism of Alecos Modinos, who formed the Cypriot Gay Liberation Movement in 1987. Amidst a nationalistic and LGBTIQ-hostile environment that hindered collective mobilization, using his ties to the Greek-Cypriot political elite, Modinos lobbied for the decriminalization of same-sex sexual conduct. Since his efforts failed, he turned to the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) that decided in his favor in 1993. Warned with expulsion by the Council of Europe, the Republic of Cyprus (RoC) parliament was forced to decriminalize same-sex sexual conduct in 1998, amidst intense opposition by the Orthodox Church of Cyprus and conservative political actors. After the late 1990s, LGBTIQ issues were again pushed into invisibility until 2009, when a new LGBTIQ organization—Accept-LGBTI Cyprus (Accept)—formed.5 Using the RoC’s inability to completely ignore LGBTIQ rights claims due to its EU-membership ensuing responsibilities, and some politicians’ wish to appear to be “EU-friendly”, Accept adopted an elite-targeting approach and pushed for LGBTIQ legal recognition (ibid.).

Through this politics, Accept succeeded the recognition of same-sex civil partnerships and the adoption of hate speech and crime legislation in 2015 and the criminalization of so-called “conversion therapies” in 2023. However, despite these important wins, a substantial part of its constituency—and particularly its gender-nonconforming members—has been growing critical of Accept’s elite-targeting, compartmentalized, and NGO-activism approach, which they see as not promoting substantive, intersectional equality. Therefore, it has distanced itself from Accept, which it sees as establishing hierarchizations and exclusions within the national LGBTIQ community (Kamenou 2021). As a result, in June 2021, Accept practically dissolved. Most of its board members stepped down due to irresolvable disagreements on several issues among themselves, and among the organization’s board and members. In March 2022, some of Accept’s remaining board members organized an open-to-the-public information meeting to signal Accept’s restart and to announce elections for a new board, which took place in May 2022. It remains to be seen whether the relaunched Accept will manage to (re)gain the trust of old and new members, what its priorities, aims, and strategies will be, and how it will interact with other, more radical LGBTIQ groups that formed during its inaction.6

In sum, EU-admission and the transnational connections that Europeanization facilitated have provided LGBTIQ activists in Cyprus the legitimacy and resources to engage in advocacy and lobbying with the government and political elites, which resulted in some legal and policy wins. This has been important for the development of the national LGBTIQ movement in a sociopolitically conservative environment. However, over time, the legitimization of this LGBTIQ politics as the “professional” and “serious” way of pursuing LGBTIQ objectives has marginalized other types of activism and restricted dialogue within the larger LGBTIQ community (Butterfield 2016). As Comaroff and Comaroff (2012, p. 7) explain, “because the history of the present reveals itself more starkly in the … [“periphery”], it challenges us to make sense of it, empirically and theoretically, from that distinctive vantage”. Additionally, understanding the “metropole-apparatus” into transnational space and the interplay between this apparatus and the dynamics of “peripheral societies” is important for transforming theory, subverting its universalisms, and decolonizing and democratizing knowledge production (Connell 2007, p. 229; Comaroff and Comaroff 2012, p. 49). Therefore, the story of LGBTIQ politics and activism in Cyprus illustrates the implications of Europeanization for (trans)national LGBTIQ politics and activism, as well as the messiness and productivity of the “norm”–“queer” relationship in relation to the negotiation of difference in collective action (Evangelista 2022; García 2020; Manalansan 2018).

4. Materials and Methods

To examine LGBTIQ activists’ views and negotiations on, and employments of, transnational LGBTIQ politics and the concomitant shaping and development of Greek-Cypriot LGBTIQ activism and politics since the late 2000s, in this article, I draw on data from interviews with 100 participants that addressed their experiences as LGBTIQ individuals and activists living in Cyprus. I conducted the interviews from 2009 to 2022 as part of three research projects on sexuality- and gender-nonconforming identities, activism, and politics in Cyprus. This decade witnessed important political, economic, and social shifts in Europe and in individual European countries, not least in respect to LGBTIQ issues—e.g., the rise to power of far-right parties, growing anti-gender mobilization, and the passage of both pro- and anti-LGBTIQ laws (Page 2019; Paternotte 2018; Szulc 2022). Collecting sets of interviews across the span of more than one decade introduces a temporal dimension to the analysis of the issues under investigation. This allows for noting consistency or changes in LGBTIQs’ understandings, negotiations, and employments of (trans)national LGBTIQ politics and activism, thus qualifying and extending existing studies on the topic. Moreover, it produces a more nuanced understanding of the interactions between national and transnational LGBTIQ discourses and politics paradigms, and of these interactions’ impact both on interviewees’ approaches to (trans)national LGBTIQ politics and activism, and on LGBTIQ (in-group) inclusion and exclusion over time.

To avoid homogenizations and essentializations, I employed participant-centered research practices—e.g., I structured interviews as conversations to allow participants to discuss issues they saw as important, asked broad open-ended questions to enable detailed accounts, maintained the role of active listener, and asked participants for comments and feedback on the interview experience. This approach places LGBTIQ people and their accounts and needs at the center of the research activity and allows them to influence the knowledgebase of the topic under examination. In doing this, it helps in minimizing unequal power relations between the researcher and the participants and producing findings that are meaningful to the latter (McCrory and O’Donnell 2016; Orbuch 1997; Riessman 2008). Therefore, I used interviews as tools to prioritize participants’ voices and gain an insight into marginalized knowledges. By sharing their stories through interviews, participants can challenge and complicate homonormative, white, western queer epistemologies, and the politics of knowledge production (Browne and Nash 2016; Namaste 2005, 2015). Using this approach also allowed me to locate participants within multiple, complex, overlapping, and often conflicting currents of national and transnational discourses and practices and, therefore, to investigate the various aspects of their everyday life, activism, politics, and resistance beyond normativized NGO structures (Gouweloos 2021; Levy and Hollan 2015; Namaste 2005, 2015).

Additionally, adhering to the principles of intersectionality (e.g., Anthias 2012; Crenshaw 1991; Yuval-Davis 2015), beyond recruiting and giving voice to marginalized groups, this analysis attempts to examine the relationships that affect them intersectionally. Namely, it recognizes and foregrounds participants’ identities, agency, and sociopolitical realities as complex, intersectional, and multidimensional, whilst not ignoring structural power relations in our understanding of them (Choo and Ferree 2010). Moreover, it interrogates in-group systems of privilege and domination—e.g., cisgenderism, maleness, and “Europeanness” (Gouweloos 2021). In doing this, it aims to be responsive to the concerns of LGBTIQ people who have been subjugated and colonized by ciscentric and heterocentric, but also by homonormative and transnormative, analyses of sexuality and gender nonconformity and of LGBTIQ political mobilization, and to highlight their perspectives as valuable sources of critique and knowledge. Consequently, it contributes to the decolonization and denormativization of “queer” and of LGBTIQ politics, by noting and challenging the workings of colonialism, imperialism, and Europeanization and transnationalization processes, as these become evident in the participants’ stories (Aizura et al. 2014; Crenshaw 1991; Namaste 2005, 2015; Pereira 2019).

To recruit interviewees, I used a snowball sampling method that began with personal networks. This method proved to be effective, as it facilitated the building of rapport during the interviews, interviewees’ openness to the researcher, and forthcoming responses to the interview questions, as referrals made by peers or acquaintances helped in developing trust. Trust and rapport between myself and participants increased over time due to my long-term research engagement in Cyprus on LGBTIQ politics and my active and public support of the Cypriot LGBTIQ community—e.g., through public speeches and media interventions. Adhering to the research principles of reflexivity, which involves acknowledging and interrogating one’s subject position in the power relations of research (Rooke 2009, p. 157) and employed theoretical conventions and conceptual frameworks (Namaste 2005, p. xi), also contributed to the building of trust and rapport (Atkinson and Flint 2001; Day 2012). For example, when asked, I was honest and forthcoming about my sexual and gender identity, even when this was not shared by participants, while I actively sought participants’ interpretations of their experiences. Furthermore, I reassured every participant that, despite my position in the power relations of research, I would uphold ethical principles in research and not misrepresent them in my work.

A spread of participants with varying backgrounds and characteristics in terms of age, place of residence, family status, number of children, education level, ethnicity, and class was sought and achieved. A summary of participants’ characteristics can be found in Table A1. However, to maintain participant engagement, I chose to avoid asking direct questions about participants’ identities as simple reflections of background characteristics. Rather, I focused on asking questions that would help me understand how participants construct their understandings and agency that would, therefore, produce the information needed to address my research questions.

The interviews lasted between 1 and 3 h and covered paths to LGBTIQ activism; experiences of LGBTIQ activism; and attitudes toward national and transnational LGBTIQ politics and activism. I audio-recorded interviews upon participants’ agreement and later transcribed them verbatim. I analyzed the transcripts to identify key themes and recurrent ideas. I used thematic narrative analysis to capture how participants defined and constructed their experiences, and to include their voices without presuming uniformity in their approaches while examining the workings of power and agency (Orbuch 1997; Riessman 2008). The analytic questions posed to the material followed from the research questions and centered around why participants decided to engage in LGBTIQ activism; their experiences as LGBTIQ activists; and their opinions about national and transnational LGBTIQ activism and politics. Additional details about materials and methods can be found in Appendix A.

5. Findings

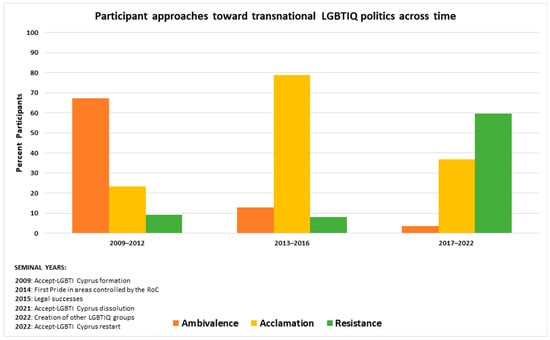

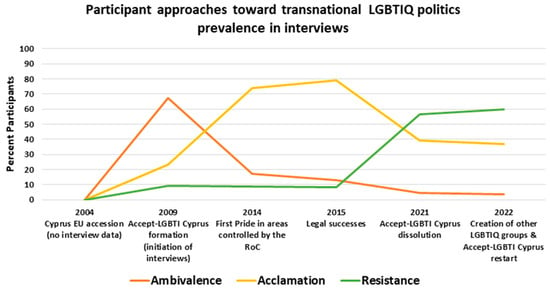

Three main themes were identified from the material from the 100 interviews conducted over 13 years, named as follows: Ambivalence toward transnational LGBTIQ politics; acclamation of transnational LGBTIQ politics; and resistance toward transnational LGBTIQ politics. I discuss the three approaches toward LGBTIQ politics in this order in the following three subsections.7 A visual representation of the development and transformation of these approaches over time and of when they became more prevalent in interviews can be seen in Figure 1 and Figure 2 below.

Figure 1.

Participant approaches toward transnational LGBTIQ politics across time.

Figure 2.

Participant approaches toward transnational LGBTIQ politics prevalence in interviews.

5.1. Ambivalence toward Transnational LGBTIQ Politics

Highlighting national context differences and challenging the idea of a single, universal, transnational LGBTIQ identity, Jeffrey Weeks (2007, p. 218) argues that “the Western [LGBTIQ] … is not seated at the top of an evolutionary tree, the only model of development, and notions of what it is to be sexually different are likely to be radically modified” (see also Blackwood 2008). In interviews I conducted in the late 2000s, participants expressed ambivalence toward transnational LGBTIQ discourses and politics paradigms. Most participants were reluctant to self-identify using sexuality and gender identity labels encompassed in the “LGBTIQ” acronym. Interviewees reported that they do not like these identity labels, or the politics with which these are associated, as they perceived transnational “western/European” LGBTIQ identities and politics as unfitting to their needs and social, cultural, and political realities. For example, a Greek-Cypriot female participant explained:

Generally, I don’t like identities. I don’t like labelling people … One doesn’t need to state to the other person: “Hi, I’m X, and this is my sexual identity”. This [statement of sexual identity] has nothing to do with anything.(KG, 2009)

However, in interviews I conducted in the mid-2010s—when the national LGBTIQ movement had become more established based on the adoption of the vocabulary and politics paradigms of the transnational LGBTIQ movement—some interviewees described using identities that are not always intelligible to them as a way of belonging to a community (Blackwood 2008). Pointing to the role of politics of language and naming in activism and collective action in erasing, partially recognizing, “rebranding”, or emancipating marginalized people and groups (García 2020), a Greek-Cypriot gender-nonconforming participant stated:

Furthermore, participants did not distinguish between “gay”/“lesbian”/“trans*” and “queer”—i.e., a term that is often employed to resist the fixity of sexual and gender identities, such as “gay”, “lesbian”, and “trans*” (Butler 1990, 1993). They appeared to be uninterested in, or unconvinced by, the different connotations that the “gay/lesbian/trans*” versus “queer” terms have assumed in “western/European” sexuality and gender identity politics and scholarship. Particularly in relation to the term “queer”, most interviewees rejected it as a term for describing non-normative sexual desire or gender expression, thus raising the questions of whether the meaning of “queer” travels across borders and what it means in Europe (Paternotte 2018, p. 62). As a Greek-Cypriot male participant said, “I have a very positive attitude toward how I describe myself … ‘Queer’ is like a piss bomb” (SM, 2017).It’s not that … I have any problem using it [i.e., the term “trans*”], but it doesn’t really make sense to me. In a way, it doesn’t cover me. I was who I am before the trans* label came to Cyprus and became popular … Before … I would say “I’m a woman”. Now I say, “I’m a trans* woman” … I like the fact that, now, we have a small family.(ZD, 2016)

According to Paul EeNam Park Hagland (1997, p. 372), “the very notion of LGBT politics read as a unified movement that is invariable across countries, cultures, and even epochs becomes a globalizing or totalizing history, an essentialist construction”. Participants’ opinions about LGBTIQ politics reflected this argument. Most of them reported that although mainstreamized transnational identities captured by the “LGBTIQ” acronym could be, and are being, used to premise political mobilization, they themselves would not mobilize under the “LGBTIQ” banner. As a Greek-Cypriot male participant foregrounded:

I’m proud to be gay, but … I wouldn’t feel comfortable being part of such [i.e., an LGBTIQ] group … The decriminalization [of same-sex conduct] did not affect me in any way; because when you go out somewhere and people realize that you are gay, they get annoyed. So, it doesn’t make a difference whether it was decriminalized or not.(JZ, 2009)

Participants’ approaches to transnational LGBTIQ discourses as reflected in these statements seem to be calling into question the applicability of transnational LGBTIQ discourses and politics—and the relevance of the identity politics-versus-queer politics debate—in places, such as Cyprus, where predominant heterocentric and ciscentric discourses and institutional practices negatively impact LGBTIQs’ ability to see themselves as citizens and exercise political agency (Evangelista 2022; Thoreson 2012). Some interviewees’ opinions on LGBTIQ rights substantiate this argument. For example, a Greek-Cypriot female participant explained:

Raising a child is a huge responsibility and same-sex relationships are more problematic than straight ones … It’s easier for them [i.e., same-sex people] to have fights and break up, and this will have negative effects on the child. I hold the same belief about same-sex marriage also.(EL, 2009)

A Greek-Cypriot male participant explained:

These statements illustrate the relationship between ambivalence toward transnational LGBTIQ politics and dominant ciscentric and heterocentric discourses in Cyprus. Other work has also reported that fear of discrimination and social marginalization inhibits the embracing of transnational LGBTIQ identities and creates ambivalence toward transnational LGBTIQ politics (Altman 1996b; Ayoub 2016; Bilić 2016).[Me and my partner] tell our families, the neighbors etc. that we are roommates, even though we know they know or they suspect… Because, this way, there’s no problem … If we explicitly said we are a gay couple, things would have been different, and we don’t want to go through this … This is how things in Cyprus are, you know?(LR, 2009)

Nonetheless, this ambivalent identification with transnational LGBTIQ politics, particularly during the early years of Cypriot LGBTIQ politics and activism, also illustrates willingness to question mainstream transnational LGBTIQ discourses about how sexuality- and gender-nonconforming identities, and politics are constituted and manifested. For example, a Greek-Cypriot male participant stated:

This ambivalent identification with, and willingness to question mainstream transnational LGBTIQ discourses, such as “coming out”, paradoxically occurs within ciscentric and heterocentric national discourses that negatively affect LGBTIQs’ lives. This, then, shows the messy conditions where the productive willingness to question mainstream transnational LGBTIQ politics ironically occurs within conditions of fear of being discriminated against, when LGBTIQ activists begin to identify with mainstream transnational LGBTIQ politics. In this sense, the ambivalence is messily critical but also acquiescent at the same time (Ayoub 2016; Evangelista 2022; Manalansan 2018).Personally, I wouldn’t want to “come out” in the sense of going out there into society and yelling it [i.e., that I’m not heterosexual] … As I told you before, I live my life and people probably think that I’m a metrosexual. … I think that if I lived under the “gay label”, my life would be much different.(WT, 2009)

In transnational LGBTIQ discourses and politics, “coming out”, renouncing one’s closeted self, and publicly manifesting one’s sexuality- and/or gender-nonconforming self has been conceptualized as a political, social, and cultural event that signals the constitution of the LGBTIQ subject as a political agent, and as a step toward responsible LGBTIQ citizenship (Bobker 2015; Hindman 2019; Meeks 2006). Nevertheless, although mainstreamized and transnationalized, particularly in places outside the “western/European” core, the ideas of the “closet” and of “coming out” have not been conceptualized as the sine qua non of the constitution of the gender- and/or sexuality-nonconforming agent, or of the formation of nonconforming sexuality and gender identity politics (Boellstorff 2007; Crawford 2008; Kulpa and Mizielińska 2016). As participants’ understandings and negotiations of transnational LGBTIQ discourses and politics show, “coming out” and the public affirmation of a non-heterosexual and/or non-cisgender identity is not uniformly seen as self-constituting or as a political act. This necessitates critically examining how discourses and practices that relate to mainstream transnational LGBTIQ politics stand in relation to the operations not only of heteronormativity and cisnormativity, but also of homonormativity and transnormativity (Ammaturo 2014, 2015, 2017; Klapeer 2017; Kulpa 2014; Mole 2017). However, it also necessitates examining the processes through which national LGBTIQ movements frame their claims and identities over time, within non-static and complex sociopolitical environments, and amidst multi-level discursive opportunities. Sometimes, this involves embracing transnational LGBTIQ discourses and politics, whilst rooting them in local contexts and linking them to indigenous articulations of queer identity (Ayoub and Chetaille 2020; Weeks 2007).

The rhetoric of transnational and allegedly widely embraced LGBTIQ identities, and of a supposedly transnational LGBTIQ movement that is representative of sexuality- and gender-nonconforming people everywhere despite local particularities may be problematic, as it could (re)establish hierarchical relations between “metropolises” and “peripheries” (Altman 1996a, 1996b; Drucker 2015; Evangelista 2022; Manalansan 1995). As Manalansan (1995, pp. 425–26) explains, the transnationalization of the LGBTIQ movement essentially defines LGBTIQ liberation by “tracing the trajectories of modernity”. Nevertheless, as the next subsection will demonstrate, it is due to their swiping force and appeal as tokens that notions and constructs, such as “Europeanization”, “westernization”, “modernity”, and “progress” have often facilitated national LGBTIQ mobilization, particularly in places where opportunities for the formation of LGBTIQ politics and activism were lacking and, in the case of Cyprus, progressively led to the development of a strong national LGBTIQ movement.

5.2. Acclamation of Transnational LGBTIQ Politics

In interviews I conducted from the late 2000s until the mid-2010s, participants reported that, amidst an LGBTIQ-hostile environment, the formation of LGBTIQ activism and politics in Cyprus, and the legal successes of LGBTIQ activism, would not have been possible without the funding, training, and support available to national groups by the “European” center through transnational LGBTIQ umbrella organizations, thus confirming the findings of previous research (e.g., Ayoub 2013, 2015, 2016, 2019; Ayoub and Paternotte 2014; Slootmaeckers et al. 2016; Swimelar 2017). However, what merits attention are the ways in which some interviewees described themselves as LGBTIQs and LGBTIQ activists through the employment of discourses about “Europe/the west” versus “the rest”.

Focusing on the post-9/11 war-on-terror United States context, Puar (2007, p. xi) elaborates the concept of “homonationalism” to describe the “connections among sexuality, race, gender, nation, class, and ethnicity in relation to the tactics, strategies, and logistics” of the US nationalist, imperialist, and exceptionalism project, and modes of (neo)liberal tolerance toward sexual minorities that sustain and reinforce the heteronormative, cisnormative, racist, and classist underpinnings of this project. Namely, homonationalism functions as a regulatory script of normative LGBTIQ-ness that aligns with this project, and of illegitimate queerness that must be extinguished in the name of this project (ibid, p. 2). As Puar (ibid, p. 39) demonstrates, the disaggregation between “national gays” and “sexual others” is based on invocations of orientalist tropes, in which LGBTIQ subjects themselves participate.

The concept has travelled well beyond the US and has been used by scholars studying its role in definitions of Europeanness (e.g., Ammaturo 2015; Colpani and Habed 2014; Freude and Vergés Bosch 2020; Kulpa 2014; Rexhepi 2016). Some of these scholars point to the ways European homonationalism functions both as a top-down process stemming from international human rights institutions and within nation-states to achieve sociopolitical goals, and describe its negative effects in creating and solidifying a false dichotomy between tolerant and intolerant EU member-states and between a queer-friendly “west” and a homophobic and transphobic “periphery” (e.g., Ammaturo 2015; Freude and Vergés Bosch 2020; Rexhepi 2016). The idealization of “western/European” countries and cultures as “progressed” in relation to LGBTIQ issues, and the attribution of this characteristic exclusively to the “west” and to Western Europe (Szulc 2022), was common among both Greek-Cypriot and Turkish-Cypriot participants. For example, a Greek-Cypriot male interviewee reported:

[Cypriot] people haven’t suddenly become gay. It’s just that, nowadays, they allow themselves to become visible … Maybe this has to do with the fact that Cyprus has become a member of the EU. During the past fifteen-twenty years, we started coming closer to Europe. More and more young people go [to university] in the United Kingdom and in the United States—especially in these two countries … So, as more young people go abroad to study, we [i.e., Cypriots] become more open-minded; because they [i.e., young people] came out of the box. But whoever doesn’t come out of the box remains the same … Now, you might think I’m telling you that there has been a change. Well, yes, but only among those people who leave their country [i.e., Cyprus].(XP, 2009)

Inscribing LGBTIQ rights in imaginations of “Europe” and the “west” (Szulc 2022, p. 387) while trying to define themselves as LGBTIQs and to enact political agency, some participants replicated the colonial discursive binarism that hierarchically organizes the world into a “civilized” “western/European” center, and a “less civilized” periphery (Almenia 2018; Lewis and Wigen 1997; Said 1978). Namely, they distinguished between the “west/Europe”, which they described as an LGBTIQ haven, and LGBTIQ-hostile, “non-European”, and “backward” Cyprus. Additionally, they distinguished between the “enlightened” Cypriots who escape the confines of their country, live abroad and, as a result, constitute themselves as proper LGBTIQ subjects, and the Cypriots who do not distance themselves from their “backward” native place and culture and, therefore, do not manage to constitute themselves as legitimate LGBTIQ subjects or as political agents. Indicatively, a Greek-Cypriot male activist said:

This [i.e., that there are various forms of discrimination against LGBTIQs in Cyprus] is also related to the fact that [geographically] we are close to Muslim, Asian, and African countries so, whether we like it or not, we are affected [by their sociocultural trends]. These are close-minded societies and because we are affected by them, we do not broaden our horizons … Nobody [i.e., none of the politicians] is really trying to change the country’s foundations to make it more liberal, more European, more tolerant.(GC, 2009)

When translated and shifted to a locally resonant language by oppressed groups and individuals—a process that Ayoub (2016, p. 34) describes as “norm brokerage”—“western/European” and transnational LGBTIQ discourses and politics paradigms can help in bringing about positive change. However, in the case of Cyprus, although they have widened the space and offered a language and means for the formation and development of national LGBTIQ politics and activism, as the interview excerpts above demonstrate, they have also reinforced existing ideas about ethnic superiority. These opinions show not only the detrimental effects of predominant nationalist discourses, but also the replication of colonialist, Eurocentric, and “western”-centric discourses within national LGBTIQ politics and activism by national LGBTIQ activists, in the context of LGBTIQ politics and activism’s transnationalization (Kumari 2018). They confirm Szulc’s (2022, pp. 388, 394) finding that the rhetoric of “Rainbow Europe is employed … to create not only external but also internal sexual Others”, not least by LGBTIQs themselves.

Nationalist, homonationalist, and trans*chauvinist discourses are deeply embedded in predominant perceptions and understandings of gender and sexuality, while the production of the self as a sexual, gendered, and political subject is enmeshed in processes of power (Puar 2007, 2013). For example, commenting on the employment of the transnational/“European” LGBTIQ human rights discourse to convince Turkish-Cypriot politicians to decriminalize same-sex sexual conduct, a Turkish-Cypriot male activist explained:

What we are trying to explain to the politicians is: “Ok, you always mention that you are more European than the Greek-Cypriot politicians” … Europe is a good pressure tool. The other thing we are trying to explain to them is this: “If you let … [LGBTIQ activists help you] make the [legal] amendments before going to Court [i.e., before some Turkish-Cypriot LGBTIQ applicant resorts to the ECHR], this will help you prove what you are saying to others, to the EU. You are saying about yourselves that you are more European [than Greek-Cypriot politicians] but you must prove how [this is the case], in a way that makes sense”.(CH, 2009)

Similarly, a Turkish-Cypriot female activist reported:

Thanks to the support of … [transnational LGBTIQ] groups … we have learned how to talk to society and to politicians about these [i.e., LGBTIQ] issues as human rights and as European issues … In the north [of Cyprus], Europe has a lot of currency, because of the need to prove to ourselves and to others that we belong to the “west” and to Europe and to the EU.(DH, 2013)

These interview excerpts substantiate the argument that, as a result of the workings of European homonationalism, the idea of “Europe” assumes specific meanings and shapes understandings of (trans)national LGBTIQ politics and activism among LGBTIQ activists in ways that reinscribe the long-lasting dichotomy between “the west/Europe” and its “others” (Colpani and Habed 2014; Kulpa and Mizielińska 2016). Kulpa (2014, p. 443) convincingly argues that, in contexts “permanently ‘transitioning’ towards the West/Europe ideal”—in a process he terms “leveraged pedagogy”8—all LGBTIQ activists in the “periphery” need to do—or, the only thing they can do, given the lack of alternative options—is let themselves “be educated in the powerful pedagogical gesture of the West/European Modernity”.

As Ayoub (2015, p. 295) explains, LGBTIQ law and policies “have become symbolic of political modernity”, while LGBTIQ participants employed “Europeanness” as a marker of power and progress in previous research as well (e.g., Szulc 2022). Furthermore, the notions and concepts around which identities crystallize, determine the nature that LGBTIQ politics will have, as well as their appeal and success (Binnie 2015, 2016; Dhawan et al. 2016). As the interview excerpts above show, albeit strategically in some instances, both Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots couch LGBTIQ politics not simply in the language of “Europe”, but in a discourse of ethnic antagonism according to which reaching “modernity” before the ethnic “other” is the main objective. The acclamation of transnational LGBTIQ politics in a (still) LGBTIQ-hostile context that was, nonetheless, “‘transitioning’ towards the West/Europe ideal” (Kulpa 2014, p. 443) was part of a wider inter-ethnic contest of reaching this “ideal” first. Namely, it took place during a time that the RoC was trying to prove to the world that its EU admission was justified, while the self-proclaimed “Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus” was trying to prove to the world that it had been unjustly excluded from EU admission. The political opportunities created by this antagonism contributed to LGBTIQ activists’ prioritization of LGBTIQ rights legislation (Kamenou 2016).

LGBTIQ activists’ strategic utilization of European homonationalist discourses to fight for legislation further highlights the messy convergence between the transnational and national conditions that create opportunities for LGBTIQ activists amidst a hostile environment. However, as the next subsection will show, this has curtailed the national LGBTIQ movement’s ability to engage in intersectional politics and, consequently, to remain relevant to its constituency. Therefore, beyond addressing the question of whether the language, discourses, and tools of the transnational LGBTIQ movement are instrumental for the empowerment of sexuality- and gender-nonconforming people in the periphery of “Europe” and of the “west”, it is important to be attentive to the in-group hierarchizations, exclusions, and alienations that the relocation of the “west/Europe”-versus-the-“rest/periphery” power dynamics within the periphery itself creates and perpetuates (Evangelista 2022; Thoreson 2012). As Elijah Adiv Edelman (2018, p. 34) explains, it is through the “recognition of complex and unequal life, the humanization of the other, and even of the political enemy, that we can shift away from a reliance on exploitation, exceptional amnesia, and oppression toward movements that create livable realities for all”.

5.3. Resistance toward Transnational LGBTIQ Politics

The mid-2010s saw the heyday of transnational LGBTIQ discourses and politics in Cyprus as, with the support of the transnational LGBTIQ movement, the Greek-Cypriot LGBTIQ movement achieved legal successes. However, the peak of the Greek-Cypriot LGBTIQ movement coincided with growing criticisms against it. As interviewees reported, these criticisms concerned its uncritical adoption and replication of the transnational LGBTIQ movement’s discourses and politics paradigms and—due to this—its increasing neoliberalization, normalization, institutionalization, professionalization, and NGOization, which tend to distance movement organizations from their constituency (Ferguson 2019; Hindman 2011, 2019). The interviews I conducted from the mid-2010s onwards capture these criticisms. As some participants explained, Accept’s failure to address internal differences and differences between the organization and its constituency, which arose mostly due to Accept’s reluctance to shift from its employed identity- and rights-based LGBTIQ politics—in the footsteps of mainstream transnational LGBTIQ organizations—to more inclusive, intersectional, and counter-normative politics, alienated them from Accept. These escalating differences manifest themselves in Accept’s approach to non-cisnormative gender identities and to its gender-nonconforming members. For example, a trans* participant foregrounded:

There is this myth that LGBTIQs are a homogeneous group … We are trying to do something on our own and it’s the ultimate betrayal, although trans* people are the poor relative … We have our own group … because we can’t afford to wait until our time comes.(QJ, 2016)

There is often a tension between increasingly influential transnational discourses of nonconforming sexualities and genders and local ones that are frequently resistant and aspire to be anti-hegemonic (Klapeer and Laskar 2018; Manalansan 1995, 2018; Povinelli and Chauncey 1999). This is more often the case when the essentialisms and hierarchies embedded in neoliberal transnational LGBTIQ rights discourses and politics remain unscrutinized, thus ignoring structural and institutionalized oppression, and reinforcing already existing essentialisms and hierarchies at the national level. By equating “freedom” and “exercising choice” with rights and the institutional structures that rights serve—e.g., marriage and the heteronormative family—the rights language inhibits questioning what “freedom” really means. Therefore, an identity- and rights-based approach does not really challenge power, but only allows the already privileged gays and lesbians to gain more access to it, since rights take issues of debate out of politics, and thus reduce the importance of collective decision-making and of mutual self-creation (Butler 2004; Gouweloos 2021; Lehr 1999). Indicatively, while addressing the issue of Accept’s stance toward non-cisgenderism and the benefits and drawbacks of an identity- and rights-based approach, an Accept activist stated:

I know we need to be good and nice gays and lesbians, if the Church and the politicians are not to stone us to death! That’s why I side in favor of gay marriage … What I want is freedom, but I know that we can’t win, unless we play their game. Still, they [i.e., trans* individuals] should be represented. After all, we are claiming that we are representing them.(OA, 2010)

These statements point both to the creation of internal boundaries within social movements to exclude socially undesirable potential members and, thus, achieve acceptability and gain respectability (e.g., Bernstein 1997; Currier 2010; Gamson 1997), and to the problematics of the ongoing binary logics surrounding compliance/cooptation and revolution/subversion (Broad 2020; Evangelista 2022; García 2020; Thoreson 2012). Additionally, they ground the argument that static identity categorizations and discursive marginalization need to be challenged for activism to be inclusive and intersectional (García 2020; Hindman 2011). In the same vein, while commenting on the early 2010s disagreements within Accept over the participation of trans* and gender-nonconforming people in the organization, and over whether the “T” in the organization’s name—“Accept-LGBTI”—should stand for “transsexual” or “transgender”, another Accept activist said:

Knowing the terminology and being politically correct and all is nice. Nonetheless, debates like this mean nothing, unless we remain united and are clear about what we want to achieve. I personally do not care about labels. What I want to see is real change … Unless we focus on this and find ways to get along despite our differences, I don’t think we [i.e., Accept] will last much longer.(ZX, 2010)

Though not impossible, striking a balance between local modalities and increasingly pervasive transnational “European/western” discourses of nonconforming sexualities and genders, and between mainstream and counter-normative politics, is neither an evitable nor an uncomplicated process. Moreover, doing intersectional politics is a messy and difficult endeavor, as difference needs to be understood as a process rather than as an identity categorization, even though it is its difficulty that makes it emancipatory (García 2020, p. 455). Therefore, national LGBTIQ organizations cannot be blamed for not always being able to engage in subversive queer intersectional politics, particularly when they operate within a hostile environment (Evangelista 2022; Manalansan 2018). Nevertheless, the view that justice does not end in the recognition of rights and that the time is ripe for a shift toward queer intersectional and counter-normative politics, is progressively gaining ground. For example, an LGBTIQ activist stated:

We suck up to parties and politicians to give us what they will give us anyways because of Europe, like same-sex civil partnerships, and we think that we have achieved something … We [i.e., LGBTIQs] are their alibi so that they can pretend to be progressive, while most of them continue to talk about “the foreigner”, “the economic migrant” as the abomination … They sweep under the carpet their xenophobia, their nationalism, their power games, and we are the carpet! … They say, “give them some rights, the minimum ones, and it’s a win-win situation”. As if superficial rights, like same-sex civil partnerships, do away with injustice and all those things we, the privileged ones, pretend do not exist.(RF, 2018)

This excerpt substantiates findings of previous research according to which LGBTIQ activists locate LGBTIQ oppression and dehumanization not in the absence of laws and policies, but in systems of privilege and domination created and nurtured by capitalism, patriarchy, neoliberalism, and colonization (Evangelista 2022; Ferguson 2019; García 2020; Gouweloos 2021). Despite their positive role in legal successes at the national level, unless constantly problematized, mainstream transnational LGBTIQ politics may lead to merely parochial and “virtual equality” (Vaid 1995), which does not diffuse into the daily lives and realities of sexuality- and gender-nonconforming people. Queering queer politics in order that it may challenge homonormativity, transnormativity, exclusion, privilege, and power entails troubling neoliberal, mainstreamized, transnational LGBTIQ identities and the politics they premise; not negating difference or abandoning social and political concerns (Ward 2008). Commenting on some Cypriot LGBTIQ activists’ approach to sexuality- and gender- nonconformity and to LGBTIQ politics, another LGBTIQ activist reported:

I’m … disgusted by these fakes … who only care to show how cultured and supposedly queer and above-all-that they are, while sipping 20-euro cosmos … What about the high school dropout who is a construction worker or a plumber and who is gay or non-cis? … They don’t care such people exist … There is a huge difference between constructive disagreement and questioning things all of us erroneously used to believe at some point, and between having reached a point where we compete and fight each other over stupidities, to the extent that the [LGBTIQ] movement in Cyprus is falling apart.(PP, 2018)

Social movement studies have highlighted the important role emotions, such as anger produced by feelings of exclusion, play in social movements and mobilization (e.g., Gould 2009; Jasper 2014, 2018; Knops and Petit 2022; Taylor 2000). As Knops and Petit (2022, p. 170) explain, understood as relational, multidimensional, and dynamic concepts that include both individual activists’ emotions and the relations, transformations, and actions they engender, in certain situations and contexts, emotions of indignation may function “as a passage from a sense of powerlessness and inaction to increased feelings of agency and empowerment”. Otherwise phrased, activists’ emotions, including anger, which the participant quoted above expressed, may transform political action and lead marginalized groups to (re)claim political power. However, feelings of exclusion and experiences of marginalization do not necessarily, automatically, or directly lead to action. For experiences and feelings to turn into critiques and motivate action, a problem and specific responses and solutions to it need to be identified, while the context of mobilization and the sociobiographical trajectories of the individuals who experience them impact this process (Benford and Snow 2000; Knops and Petit 2022). In the case under examination in this article, participants feeling marginalized within Accept and/or feeling that Accept generates and sustains LGBTIQ in-group exclusions identified the problem as one of problematic employed campaigns and tactics, which uncritically mimic mainstream transnational LGBTIQ campaigns and tactics. Referring to principles of queer intersectionality in activist campaigns—that prioritize resistance toward: short-sighted institutional legitimacy-oriented strategies; the invocation of forms of diversity that exist elsewhere at the expense of acknowledging forms of diversity at home; and expansion of the range of activities understood to be political (Ward 2008, pp. 19, 139–41)—the solution they identified was their distancing from Accept and the formation of alternative LGBTIQ groups.

Other work on LGBTIQ activism and politics has already demonstrated that in-group inequalities and exclusions may stimulate the formation of new community spaces “rooted in more complex understandings of queerness and intersectional politics” (Gouweloos 2021, p. 242; see also Broad 2020; Ward 2008). Some interviewees’ opinions on (trans)national LGBTIQ activism and politics substantiate this finding. For example, commenting on his decision to leave Accept and create a new LGBTIQ group along with other former Accept members, another LGBTIQ activist explained:

What we need is to find our commonalities and to create ties, at the social and at the cultural level … One can’t be speaking of an LGBTIQ community when the community is not there … Being an LGBTIQ activist isn’t a job one does for an organization. It’s about how one lives every day, [about] how one is able and, most importantly, willing to understand others and reach out to them … despite whether this person is richer or more educated than others or has less needs.(XW, 2022)

This growing collective resistance toward mainstream transnational LGBTIQ politics and their replication at the national level, and the bifurcation of the LGBTIQ movement in a context characterized by complex discursive intersections amidst Europeanization and other transnationalization processes where nonconforming genders and sexualities continue to be devalued, further highlight the messy and productive conditions within which “norm” and “queer” are constantly colliding, intersecting, (re)imagined, and (re)negotiated, not least by LGBTIQ activists. A counter-normative, anti-essentialist, intersectional, and queer approach to LGBTIQ politics necessitates “that we define complex experiences as closely to their full complexity as possible and that we not ignore voices at the margin” (Grillo 1995, p. 22). It also requires realizing that “transnational organizing is, to a large extent, an elitist endeavor for resourceful, privileged groups” (Rolandsen Agustín 2013, p. 72). Therefore, the notion of mainstream, transnational LGBTIQ politics as a criterion of progress needs to be balanced with a degree of resistance to the transnationalization, institutionalization, professionalization, and NGOization of neoliberal schemes of sexuality- and gender-nonconformity politics, while the cultivation of inclusive and intersectional consciousness and practices needs to be set as a priority (Ayoub 2014, 2019; Broad 2020; Hindman 2011).

6. Conclusions

This article has examined how Cypriot LGBTIQs’ perceptions about national and transnational LGBTIQ politics and activism have developed and transformed over time, amidst the interplay between national and transnational LGBTIQ discourses of sexuality- and gender-nonconforming identities and politics, in the context of Europeanization and other transnationalization processes. The analysis of interviews has identified three approaches toward transnational LGBTIQ politics among LGBTIQ activists, from the early days of Cypriot LGBTIQ politics and activism until today: Ambivalence toward, acclamation of, and resistance toward transnational LGBTIQ politics. Despite initial ambivalence toward transnational LGBTIQ politics—particularly during the late 2000s, due to the predominance of nationalist and essentialist discourses and institutional practices that negatively impacted LGBTIQs ability to exercise political agency—Cyprus’s EU admission and Europeanization processes, and the concomitant expansion of the transnational LGBTIQ movement, enabled national LGBTIQs to mobilize. Some legal successes in the mid-2010s signaled the heyday of mainstream (trans)national LGBTIQ identity- and rights-based politics on the island. Nonetheless, this politics, and their accompanying discourses, did not do away with but, rather, reinforced already existing essentialisms, hierarchies, and ideas about ethnic superiority. By the late 2010s, in-group disagreements had already deeply divided the national LGBTIQ movement. These disagreements stemmed from the national LGBTIQ politics’ neoliberalization, institutionalization, professionalization, and NGOization, as well as from its prioritization of legal wins and neoliberal notions of equality—in the footsteps of transnational LGBTIQ organizations—over the development of inclusive, intersectional, and counter-normative politics and activism.

These findings highlight the dynamics and tensions between national and transnational LGBTIQ activism and politics (Ayoub 2016; Ayoub and Chetaille 2020; Bracke 2012; Manalansan 2018), and the messy but productive relationship between “norm” and “queer” (Evangelista 2022; Manalansan 2018), from LGBTIQ activists’ perspectives. They confirm that the processes through which national LGBTIQ movements outside the “western/European” center frame their claims and identities over time may not be fully captured by the clash between local and “western/European” discourses and politics paradigms. Therefore, this article highlights the importance of studying LGBTIQ activists’ accounts for better understanding (trans)national LGBTIQ politics and exemplifies the complex processes and agency that shape the spaces in which, and the ways through which, minority groups in contentious contexts can pursue their political objectives. It also contributes and speaks to other work on (trans)national LGBTIQ politics and activism, including work on shifts in norms and political attitudes toward nonconforming sexualities and genders at the domestic and transnational level that focuses on the role of temporality, generation, and age, as these are mediated by other social divisions, context, and national-transnational dynamics (e.g., Ayoub and Garretson 2017; Binnie and Klesse 2013; Plummer 2010, 2016). Furthermore, focusing on Cyprus and on Cypriot LGBTIQ activists, the article demonstrates that, in some contexts, there is a lot of ground to cover to “queer” queer politics, while “the transnational turn” also needs to be queered (Chiang and Wong 2016). Therefore, it points to the limitations and opportunities of queer activism and politics and, in doing this, it contributes to queer studies literature.

Queer normativity is as exclusionary as any normativity while, once it becomes a mere identity, “queer” becomes yet another marker of hierarchical differentiation and relational privilege. It is relegated from a tool of problematization and resistance to a symptom and cause of the neoliberal depoliticization of sexuality and gender nonconformity (Rawson 2010, p. 46). As Jane Ward (2008, p. 19) argues, “‘queer intersectionality’ is an approach that strives for racial, gender, socioeconomic, and sexual diversity, but also resists the institutional forces that seek to contain and normalize differences, or reduce them to their use value”. Therefore, it is crucial that LGBTIQ activists bring to the political forefront issues of intersectional marginalization, refuse the standard divisions of LGBTIQ identity politics, and shift from neoliberal, professionalized, and compartmentalized activism to an intersectional political approach, and to queer emancipatory politics. This points to the need for research on the ways in which activists engaged in contentious politics and located between national and transnational circuits of power and discourse, navigate these circuits and do queer intersectional politics. In a time of global interconnectedness facilitated by communication technologies (Ayoub and Garretson 2017; Binnie and Klesse 2013; Plummer 2010, 2016), the issue of whether and to what extent this process is also generational, and of the means and mechanisms through which generational shifts in queer thought and politics occur are particularly promising avenues for future research.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Interviews upon which this article draws were conducted as part of three research projects approved respectively by the KING’S COLLEGE LONDON Social Sciences, Humanities, and Law Research Ethics Subcommittee (protocol code: SSHL 08/09-4; date of approval: 13 November 2008), the DE MONTFORT UNIVERSITY Faculty of Health and Life Sciences Research Ethics Committee (protocol code 1758; date of approval: 11 May 2016), and the CYPRUS NATIONAL BIOETHICS COMMITTEE (protocol code 2021.01.268; date of approval: 13 December 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank all the participants who shared their perspectives and experiences with me. I would also like to thank colleagues who commented on drafts.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Additional Details about Materials and Methods

Appendix A.1. Participants by Age and Gender Self-Identification

Table A1.

Participants by Age and Gender Self-Identification.

Table A1.

Participants by Age and Gender Self-Identification.

| Participant Characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Characteristic 1 | N |

| Age | |

| 18–30 | 25 |

| 31–40 | 34 |

| 41–50 | 22 |

| 51–60 | 16 |

| >60 | 3 |

| Gender self-identification | |

| Male/man | 44 |

| Female/woman | 32 |

| Trans* male/man | 7 |

| Trans* female/woman | 5 |

| Other | 12 |

1 General categories and broad ranges used to ensure nonidentification of participants.

Appendix A.2. Procedures

Interviews upon which this article draws were conducted as part of three research projects. Before the interviews were conducted, the three research projects were respectively approved by the King’s College London Social Sciences, Humanities, and Law Research Ethics Subcommittee (protocol code: SSHL 08/09-4; date of approval: 13 November 2008), the De Montfort University Faculty of Health and Life Sciences Research Ethics Committee (protocol code 1758; date of approval: 11 May 2016), and the Cyprus National Bioethics Committee (protocol code 2021.01.268; date of approval: 13 December 2021).

For all three projects, a snowball sampling method was used, which began with personal networks with the Cypriot LGBTIQ community. Before deciding whether or not to agree to an interview, participants were given and asked to carefully read information sheets that described: The topic of the studies; the studies’ aims and objectives; what participation in the studies involved; how information from interviews would be used; participants’ rights in relation to agreeing to participate or not; participants’ rights in relation to withdrawing from participation; participants’ rights in relation to withdrawing information they had provided; procedures for raising complaints and seeking redress in relation to their participation in the research projects; the ways in which confidentiality, anonymity, and participants’ nonidentification would be assured in the handling and usage of the information provided by research participants; who the lead researcher was and ways of contacting her; and information relating to the approval the studies had received from Ethics Committees.

All participants provided informed consent by signing a consent form before the interviews. Participants were asked to carefully read, complete, and sign informed consent forms in which they confirmed that they: Had read and understood the research project information sheet; had had the opportunity to consider the information contained in the information sheet, ask questions, and have these questions answered satisfactorily; had understood that their participation was voluntary and that they were free to withdraw at any time without giving any reason; had understood that they were able to withdraw their data up to the point stated in the information sheet; agreed that non-identifiable quotes may be published in articles or used in conference presentations; agreed to the interview being audio-recorded; and agreed to participate in the study.

The interviews were conducted in person at a location chosen by the participant. Most participants asked that the interview takes place in their homes. Other chose the interview to be conducted in private study rooms at the University of Cyprus Library, or in my private office at the University of Cyprus. The interviews lasted between 1 and 3 h and the average length of interviews was between 2 h and 28 min. All interviews were audio-recorded upon participants’ consent and later transcribed verbatim in full. To maintain confidentiality and anonymity and to ensure participants’ nonidentification, personal information was removed from transcripts, and names mentioned during the interviews were replaced with fake initials.

Appendix A.3. Instruments