Abstract

The main purpose of this study is to clarify the difference in disaster resilience between survivors and victims’ families by analyzing the language used in popular literature on disaster cases. The results showed that there were differences in emotions, behaviors, attitudes, role perceptions, etc., between survivors and victims’ families in dealing with a disaster. In particular, survivors remember and think about the situation that occurred at the time of the disaster, which creates resilience to the incident, while victims’ families attempt to establish resilience to the incident by investigating the facts and government countermeasures. While survivors were focused on building their own resilience, victims’ families were more focused on improving government countermeasures to prevent such accidents from recurring. This can be considered as social or national resilience. Based on this comparative analysis, it is necessary to prepare various theoretical foundations for disaster preparedness and resilience, while further elaborating the theory.

1. Introduction

Disasters disrupt habitual and institutionalized patterns of behavior and produce a social shock that leads to social and personal change. Historical examples show that the problems and weaknesses of a given society and the existing social order change after a disaster, while relevant values and essentials are realized (Solnit 2010). Literary works influence audiences’ reactions: children can increase their understanding of various races through multicultural works (Altieri 1993), while didactic literary works help confirm the value and identity of local communities (White 1998).

Most literary works reflect the social aspects of the times. In disaster-ridden areas, disasters naturally appear in literary works. However, although various studies of literary works have been conducted (Clarke 2005; Demers 1993; Razi 2012), there are few systematic studies of literary works related to disasters (Gardner 2014; Liverman and Sherman 2015; Quarantelli 1980), because, when analyzing literary works, researchers lack multiple perspectives or attempts to observe. From a literary perspective on disasters, no concrete research has been conducted on analyzing disaster preparedness or resilience (Iwata-Weickgenannt 2019; Serrano-Muñoz 2019; Han 2020).

On 16 April 2014, the Sewol ferry, carrying a total of 476 persons from Incheon to Jeju Island, sank in the sea near Jindo, leaving 304 passengers either dead or missing. Given that the majority of victims were high-school students, the bereaved parents experienced tremendous shock and pain (Lee et al. 2017). Moreover, factors that added to the stress, such as the failure to rescue passengers due to poor response, sensational and political media reports, the lack of a search process for missing persons, controversy over the enactment of special laws, and the lifting of the sunken Sewol ferry, hindered the normal mourning process and caused long-lasting psychological difficulties, such as re-experience, anger, depression, and isolation (Lee et al. 2017).

According to a survey on support for victims of the Sewol ferry disaster (2016), 60 out of 145 family members of the victims (41.4%) considered suicide, while 6 attempted suicide. In May 2015, one year after the disaster, a victim’s father in his 50s killed himself (Ilbo 2017). Another study reported that 96 of 131 family members of the victims (73%) severed social relations while 87 (67%) quit their jobs (Park 2015). Although four years have passed since the sinking of the Sewol ferry in 2014, the psychological and social pain experienced by the bereaved has been widely reported (Lee et al. 2018a; Woo et al. 2015; Yang et al. 2015).

The present study goes beyond general discussions on the organization (Bajek et al. 2008; Buckland and Rahman 1999; Kirschenbaum 2019), disaster management systems (Abrahams 2001; Alazawi et al. 2011; Careem et al. 2006), and disaster management techniques (Fajardo and Oppous 2010; Jha et al. 2008; Van Oosterom et al. 2006) of disaster research and instead asks, “How much can the experience of an indirect crisis situation through literary works help in a crisis?”.

Literary works influence recipients, provoking various reactions. Altieri (1993) claimed that multicultural works can improve children’s understanding of various races, while White (1998) asserted that didactic literary works help confirm the value and identity of the community.

In other words, no concrete research has been conducted that centers on human nature in disasters from a literary perspective. Therefore, a new approach is necessary to find, analyze, and theorize the abilities of systems and organizations to flexibly respond to crises.

We have entered an era in which everyday life is a disaster due to severe climate change and the economic crisis (depression) that has been accelerating since 2008. While disasters are ever-present, there is little discussion in popular culture about overcoming them. The main objective of this study is to reveal the development direction of national disaster management in the modern age by promoting pro-social behaviors in society through an analysis of disaster literature.

The main purpose of this study is to clarify the difference in disaster resilience between survivors and victims’ families by analyzing the language in popular literature on disaster cases. Through this analysis, this study aims to uncover the development direction of disaster management in the modern state.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Survivors’ Resilience

Many disaster survivors suffer long-lasting mental health disorders. According to Rodriguez and Kohn (2008), most disaster survivors have mild or strong mental illness, but only a few receive medical treatment. For most disaster survivors, there is a large psychological impact, and the memories of those affected by the disaster persist for a long time (Joseph et al. 1992), particularly for younger survivors.

According to a long-term follow-up study by Green et al. (1994) on children who survived a disaster, post-traumatic stress disorder gradually decreased over the 17 years after the disaster. However, thoughts of suicide and abnormal behaviors, such as self-destruction, were also revealed.

Morgan et al. (2003) found that life-threatening disaster experiences in childhood remained as trauma for as long as 33 years and had a long-term effect on disaster resilience. According to Gleser et al. (1978), in disaster survivors psychological stress and thoughts regarding toward those who did not survive the disaster often lead to a feeling of self-rescue.

Generally, long-term follow-up studies on overcoming PTSD are mainstream in disaster survivor resilience studies (Fernandez et al. 2017; Hamblen et al. 2017; Lowe et al. 2018; North et al. 2020; Shang et al. 2019). There is a deep connection between disaster survivor resilience and mental health, with differences based on age group (children, adolescents, or adults), but there are also commonalities in long-term mental health and quality of life effects. Therefore, mental health treatment services are a major factor in improving disaster survivors’ resilience, with rehabilitation a vital factor in promoting resilience, and the social support system and community experts’ support also helpful factors (Laksmita et al. 2020).

2.2. Resilience of the Victim’s Family

The family members closest to the victims of a disaster are affected for various reasons, from witnessing the disaster to losing family members. They are harmed in the short or long term, both economically and mentally. However, studies on the necessity of countermeasures for families of disaster victims are insufficient (Dorn et al. 2006).

Kristensen et al. (2010), Lenferink et al. (2017), Boelen et al. (2008), and Huh et al. (2017) found that survivors experience “complex grief” after a disaster, meaning that the loss of a family member is combined with economic loss, unemployment, employment for a living, and a demand for social support to solve the problem.

Davis (2013) has called for a study on negligence, responsibility, and injustice in the problems facing many casualties and survivors of disasters. Bereaved families demand material measures and an apology for the damage caused by the government to overcome the conflict and mental and economic damage that occur through sudden bereavement (Davis and Scraton 1999).

Cao et al. (2013) found a prevalence of 59.5% in family dysfunction among families bereaved by a disaster, including economic difficulties due to old age, divorce or widowhood, direct exposure to the death of children, not having children after a disaster, and creating a poorer family economy.

Despite knowledge of adequate psychosocial support for those facing death, loss, and severe stress in the context of major disasters, it is important to understand what those affected expect from government officials and public leaders. In Jong and Dückers’ (2019) review of studies on the role of government in helping disaster survivors, they found that survivors expect the government to help them recover from disasters in a fair, compassionate, equal, and reliable way. They expect support with practical needs related to the disaster, and assume that the government will coordinate network partners and break bureaucratic barriers.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

In this study, we analyzed two literary works: an essay by the families of disaster victims called The Day Knocked on Our Window (Sewol Ferry Disaster Writers Records 2019), which is a record of families of those on the Sewol ferry; and Spring Will Come Again (Sewol Ferry Disaster Writers Records 2016), a record of the survivors of the disaster (Sewol ferry survival student: 16 April 2014) (Sewol Ferry Disaster Writers Records 2016, 2019).

Since disaster resilience tracks change after a disaster, The Day Knocking on Our Window (Sewol Ferry Disaster Writers Records 2019) is important for giving voice to the victims’ families five years after the event, while Spring Will Come Again (Sewol Ferry Disaster Writers Records 2016) gives voice to survivors two years after the event. These works were selected because they directly targeted survivors and victims’ families (Sewol Ferry Disaster Writers Records 2016, 2019).

We selected these two works for the following reasons. First, it is the first essay written for survivors and their families after a social disaster in Korean society (Sewol Ferry Disaster Writers Records 2016, 2019). Second, the essay is composed based on the interview format of survivors and victims’ families and can be used for language network analysis or interview analysis (Kalocsányiová and Shatnawi 2021; Uekusa 2019; Yari et al. 2019). Third, the Sewol ferry disaster is an unprecedented accident that has caused national trauma for a long time in Korean society (Lee et al. 2018b; Kang 2021; Chung et al. 2021; Lee and Khang 2020). Therefore, it can be a basic data that helps to find the resilience of local communities and countries.

3.2. Method

The text-mining technique’s simple keyword frequency analysis is useful for analyzing differences between two texts and for identifying the author’s intention, particularly in literary works (Amado et al. 2018; Choi et al. 2021; Sapach 2020). R was used for text mining, while NodeXL and UCINET64 were used for semantic network analysis. First, from the text collected using R, an open-source statistics program, we (1) removed special characters, (2) cut the text into word units, (3) divided each word into words and endings, and (4) extracted only words (nouns) from them. The data were purified in the following order:

The frequency of occurrence words was analyzed, and the weights of the occurrence words were analyzed in a table. Additionally, to analyze the connectivity between words, bigrams were extracted using R, and the number and centrality of the connecting lines were analyzed using NodeXL. A language network chart was created using NodeXL. A convergence of integrated correlation (CONCOR) analysis was conducted to form clusters by determining the similarity of keywords using the UCINET64 program.

3.3. Analysis

The indices used to compare the differences between network structures derived from language network analysis are the number of links (degree) and centrality, which represent the local characteristics of individual nodes (Jang and Choi 2012). Centrality is an index that evaluates the degree of closeness of each node to the center and is classified into closeness centrality, betweenness centrality, and eigenvector centrality (Hur 2010; Son 2002).

First, closeness centrality indicates how close one node is to another, with the distance between two nodes as the core concept. A high closeness centrality means that the word can be easily linked with another word (Son 2002). Betweenness centrality is a numerical value of the mediating role of a node. A word with high betweenness centrality influences the relationship between other words and plays the role of linking (mediating) words within the network (Lee and Hong 2016). Eigenvector centrality is an index for searching for central words in the overall structure of a network (Bonacich 1987). It considers not only the number of linked nodes but also their importance (Han et al. 2015). In this study, we identified the centrality of a word in the network by using eigenvector centrality according to Doerfel and Connaughton (2009).

Furthermore, the CONCOR, a language network analysis technique, is appropriate for identifying the main topic of a text by deriving a cluster formed by similar words (Kang et al. 2018). This analysis method finds the relationship between blocks by conducting a Pearson correlation analysis of matrices between words that appear simultaneously and identifying blocks of similar nodes based on them (Lim and Joung 2019). It analyzes the similarity between nodes by finding nodes at the same position structurally in the linked relationships of nodes (Kang et al. 2018).

CONCOR analysis was conducted to analyze the similar clusters and structures of words with the main meaning by referring to the eigenvector centrality and number of connected nodes. In this analysis, a dendrogram that categorizes input words was generated using a hierarchical cluster analysis method representing the structural equivalence relationship.

4. Discussion

4.1. Keyword Analysis of Literature Works of the Sewol Ferry Disaster

To analyze keywords related to the disaster in two works, 13,685 words were extracted from Spring Will Come Again, while 18,897 words were extracted from The Day Knocked on Our Window. A total of 100 words were extracted according to their frequency of occurrence and organized as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Top 100 words in frequency.

Frequently-appearing words are as follows: First, words related to the entities associated with the accident were common. Survivors often mention persons who were with them at the time of the accident, such as friends, people, us, and teachers. Victims’ families often mention persons related to the victims, such as fathers, mothers, children, and parents.

Equally common are expressions regarding the situation. Survivors use expressions associated with the urgent situation at the time, such as time, phone, situation, hospital, and life jacket. Victims’ families use situational expressions such as bereaved, phone, situation, Paengmok Port, Sewol ferry, school, company, gym, and workplace. This indicates that there are differences between survivors and victims’ families regarding situations and places.

Thirdly, there are expressions of emotions. Survivors use many such expressions, including worry, sorry, wrong, anguish, and comfort, while victims’ families express similar but different emotions, such as worry and tears.

Fourth are expressions related to resilience. When examining words related to overcoming and recovering from a disaster, survivors use many words to overcome mental wounds, such as memory, story, help, comfort, and effort, while victims’ families use many policy-related words, such as fact-finding, president, government, and special law (Table 1).

In general, resilience refers to the phenomenon of recovering from a physical or mental shock. Resilience in a disaster situation refers to a state in which the victim returns to the state before the disaster occurred. Here, the words memory and story are related to counseling, which is often used as a technique for overcoming general PTSD syndrome (Jung 2019; Mahn et al. 2021; Tanaka et al. 2020). The words help, comfort, and effort can be related to the words of help and effort to return to daily life in a disaster situation (Tyler and Sadiq 2018; Mosby et al. 2021; Meduri 2021). The words president, government, and special law generally refer to words in terms of prevention and recurrence prevention after a disaster, and resilience in disasters is highly related to prevention (Turudić and Britvić Vetma 2021; Kansra 2019).

To examine words that appeared simultaneously, a language network analysis was conducted, and the number of connection lines, betweenness centrality, closeness centrality, and eigenvector centrality were checked (Table 2 and Table 3). As a result of analyzing the language networks of survivors, the total number of links was 13,705, and the average number of links per word was 6103. Centrality analysis revealed that the averages of betweenness centrality, closeness centrality, and eigenvector centrality were 5046.70, 0.0000728, and 0.000257, respectively. When examining the eigenvector centrality in the literature of victims’ families, we was the highest, followed by thought, child(ren), situation, talk, phone, appearance, day, last, Jindo Island, sorry, worry, sea, company, special law, missing person, fact-finding, and truth (Table 4 and Table 5).

Table 2.

Indices for the analysis results of the language network of survivors.

Table 3.

Indices for the analysis results of the language network of victims’ families.

Table 4.

Eigenvector Centrality Survivor Top 100 Words.

Table 5.

Eigenvector centrality of victims’ family top 100 words.

Next, according to the results of the language network analysis of victims’ families, the total number of links was 19,501, while the average number of links per word was 5913. Centrality analysis revealed that the averages of betweenness centrality, closeness centrality, and eigenvector centrality were 7702.082, 0.000048, and 0.000174, respectively. Among the words that appeared in the literature of survivors and victims’ families, the top 100 words with a high weight based on eigenvector centrality were extracted, and the network of extracted words was examined. As a result of analyzing the eigenvector centrality in the literature of survivors, thought had the highest centrality, followed by people, friends, us, then, friend(s), real, parents, younger siblings, time, story, teacher, worry, that day, etc. (Table 4 and Table 5).

First, the centrality of thinking appeared equally high in the literature of survivors and victims’ families because the study data were analyzed as replies or contents describing respondents’ opinions. Thought is a function of counting and judging objects (Korean dictionary) and is generally used to express one’s opinion on a specific object.

In the literature on survivors, friends, brothers, and younger brothers who were victims of the Sewol ferry disaster were connected with words that recalled the time of the incident, such as real, memory, worries, and circumstances. Equally present were words that evoke accompanying persons at the time of the incident, such as friends and teachers, and guardian words such as mom, dad, and parents.

In the literature on victims’ families, later, appearance, real, sound, time, and story were directly linked to the situation at the time. Paengmokhang, photo, last, and image were directly linked to words associated with the victim.

Regarding the difference in words between survivors and victims’ families, survivors used many words related to the situation and accompanying persons at the time of the incident, while appearing to have a negative connection to the situation and content of the incident and the government’s response.

4.2. Classification of Subjects through the Analysis of Similar Word Clusters in Literature on the Sewol Ferry Disaster

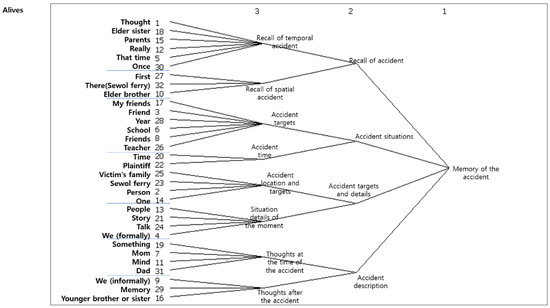

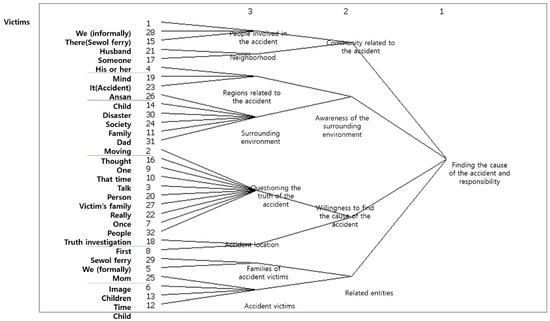

As a result of the analysis, a total of four similar word clusters were generated from the literature on survivors and victims’ families, and four themes were derived by synthesizing the words in each cluster (Figure 1 and Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Similar word clusters and meanings of survivors.

Figure 2.

Similar word clusters and the meanings of victims’ families.

As a result of conducting a similar word cluster analysis (CONCOR) on the survivors’ essay, overall themes were derived for the memory of the victim, family, and accident. First, the first language cluster, consisting of elder sister, parents, that time, etc., and the second language cluster, consisting of first, there (Sewol ferry), and elder brother are related to the survivor’s memory of the person he recalled at the time of the accident. In other words, it can be said that it is a word about the memory of the time when the Sewol Ferry sank, and the memories of one’s parents, brothers, and sisters there. However, the first word cluster contains the concept of time, while the second word cluster contains the concept of space. Therefore, the two similar word clusters were named ‘Recall of temporal accident’ and ‘Recall of spatial accident’, respectively, and the upper theme was named ‘Recall of accident’.

As the third language cluster—My friends, Friend, Year, School, Friends, and Teacher—consists of words referring to the victim of the accident at the time, and the fourth language cluster—Time and Plaintiff—refers to the time of the accident, the two similar clusters were named ‘Accident targets’ and ‘Accident time’, respectively, and the upper theme was named ‘Accident situations’.

The fifth language cluster—Victim’s family, Sewol ferry, Person, One—is composed of words referring to the victim’s family and the location of the accident, and the sixth language cluster—People, story, talk, we (formally)—refers to the content of the accident. Thus, the two similar clusters were named ‘Accident location and targets’ and ‘Situation details of the moment’, respectively, and the upper theme was named ‘Accident targets and details’.

The seventh language cluster—something, mom, mind, and dad—is a summary of the thoughts that survivors had at the time of the accident, and it seems that children at the disaster site recalled their thoughts about their parents. The last and eighth language cluster—we (formally), memory, younger brother or sister—are thoughts after the accident, which can be seen as memories at the disaster site and things about the younger brothers who were lost in the disaster situation. These two similar cluster words were named ‘Thoughts at the time of the accident’ and ‘Thoughts after the accident’, and the upper theme was named ‘Accident description’. The second highest theme of the survivor’s essay was named ‘Memory of the accident’.

As a result of conducting a similar word cluster analysis (CONCOR) on the victim’s family essay, the themes of the remaining family, the truth of the accident, finding the truth, and the environment were derived. First, We (informally), There (Sewol ferry), and Husband can be seen as words that include families and places related to an accident. Someone, His, or Her can be seen as words that include indirect neighbors and people related to the accident. The first word cluster contains subjects that are directly related to the accident, and the second word cluster contains subjects that are indirectly related to the accident. Therefore, the two similar word clusters were named ‘People involved in the accident’ and ‘Neighborhood’, respectively, and the upper theme was named the ‘Community related to the accident’.

The third word cluster—Mind, It (Accident), and Ansan—is composed of words that mean areas with high relevance to the accident, and the fourth word cluster—Child, Disaster, Society, Family, Dad, Moving—consists of words related to the surrounding environment associated with the accident. These two similar cluster words were named ‘Regions related to the accident’ and ‘Surrounding environment’, and the upper theme was named ‘Awareness of the surrounding environment’.

The fifth language cluster—Thought, One, That time, Talk, Person, Victim’s family, Really, Once, People, Truth investigation—refers to words related to finding the cause, truth, and responsibility at the time of the accident, and the sixth language cluster—First, Sewol ferry—concerns the place at the time of the accident. These two similar cluster words were named ‘Questioning the truth of the accident’ and ‘Accident location’, and the upper theme was named ‘Willingness to find the cause of the accident’.

The seventh language cluster—We (formally), and Mom—is a language cluster indicating the victim’s family, and the eighth language cluster—Image, Children, Time, Child—is a language cluster indicating the victim and the victim’s family. These two similar cluster words were named ‘Families of accident victims’ and ‘Accident victims’, and the upper theme was named ‘Related entities’. The second highest theme of the victim’s family essay was named ‘Finding the cause of the accident and responsibility’.

4.3. Sub-Conclusions

According to the analysis of the language network results, the major difference between the survivors’ essay and the victims’ family essay is the memory and recollection of the accident. First, according to the survivors’ essay, survivors have memories and recollections focusing on the person at the time of the accident, the circumstances at the time of the accident, and the content of the accident. Second, the victims’ family essay goes deeper into the question of the person at the time of the accident, the family left behind, the cause of the accident, the person responsible for the accident, and the truth about the accident.

Therefore, we believe that in order to strengthen resilience after a disaster, it is necessary to distinguish between the crisis management of the victim of the accident and the victim’s family related to the accident. In the case of the victim of the accident, a way to relieve the trauma of the accident is needed (Massazza et al. 2021; Le Roux and Cobham 2021; Bountress et al. 2020), and in the case of the victim’s family, a policy (Lee et al. 2020; Park and Bae 2022; Atkinson and Curnin 2020) is needed to relieve the injustice caused by sacrifice and help the left behind families and communities to lead normal lives.

5. Conclusions

With the Sewol ferry disaster in 2014, problems related to social disasters and corruption became social issues. Studies have been conducted in various fields on the Sewol ferry disaster and social disasters, but no in-depth analysis through literary works has been conducted (Huh et al. 2017; Chae et al. 2018; Kee et al. 2017).

Disaster-related literary works do not have a unified conclusion, and the themes are diverse. Considering this diversity, we can indirectly experience new perspectives on disasters in human society (Baque 2019; Chovanec 2019), and learn how the damage of disasters affects its victims. Such experiences enable an indirect experience of trauma in a disaster situation, thereby leading to the acquisition of a mindset for disaster prevention (Thornber 2021).

In addition, literary analysis can not only predict the cause and damage scale of disasters, but also examine the emotional aspects (social exclusion, disgust). This can be used to tackle complex questions about various types of violence caused by disasters (Bhattacharya 2020; Uyheng 2020). In particular, literary texts depicting real disasters are the most powerful works that explore the lives of disaster victims. This reveals how individuals and disasters have affected their lives (Potts 2018; Mika 2018).

Through a text analysis of disaster literature, this study summarizes the characteristics and significance of survivors’ and victims’ families’ perceptions. The results showed differences in emotions, behaviors, attitudes, role perceptions, etc., as perceived by survivors and victims’ families in dealing with a disaster.

First, the group and meaning of the similar words of survivors are as follows. The first theme is the feelings and conditions of survivor’ targets. There are two sub-themes: “the person concerned and feelings” and “the subject involved and the situation at the time”. This theme is formed of words about thoughts, older sisters, parents, first, brother, there, real, once, and related subjects, thoughts, and feelings. In particular, it is composed of words about victims composed of friends, school, and teachers, and words related to the time of the victim, such as time.

The third subject is the victim and the content, which is composed of two sub-themes: ‘the place and object’ and ‘the content of the situation at the time’. This topic consists of words related to ‘place and object of damage’, such as the Sewol ferry, people, and survivors, and words such as stories, story, and people as ‘the content of the situation at the time’.

The fourth theme was emotion and resilience at the time, and was composed of two sub-themes: ‘Emotion’ and ‘Resilient Emotion’. It is composed of words containing emotions such as mind and something, and meaningful words to remember the situation at the time related to memory and construct resilience through it.

Next, the similar word clusters and meanings of victims’ families are as follows. The first is a cluster of ‘objects and subjects’, composed of two sub-themes, the related object and the related subject, in which words are formed around husband, who, our related person, and the subject. The second is the subject of ‘damage situations and emotions’, and consists of two sub-themes: ‘damage-related areas and emotions’ and ‘damage situation’. Words are formed for the area where the victims live, such as Ansan, and the change of circumstances according to the damage situation, such as tragedy, the world, and moving.

The third theme is ‘request to the government for recovery of the case’, which includes two sub-themes: ‘feelings and demands of the government’ and ‘place of damage’. This theme is composed of words that refer to a transparent and truthful case resolution, such as surviving family, real, once, truth finding, and words for the Sewol ferry, the same damage place as the first.

The fourth theme is related to the subject and is composed of two sub-themes: ‘victim’s family’ and ‘victim’. It is composed of words that recall related subjects through their mothers, children, and appearance.

In particular, survivors remember and think about the situation at that time and develop resilience to the incident, while victims’ families attempt to establish resilience to the incident by investigating the facts and government countermeasures.

While survivors focused on building their own resilience, victims’ families were focused more on improving government countermeasures to prevent such accidents from recurring. This can be considered as social or national resilience.

In this study, we analyzed two literary works in which survivors and victims’ families participated to explore the meaning of disaster literary works. However, this study is limited in that it analyzed literary works containing the opinions of only some survivors and victims’ families. Future work should elaborate the results of this study by preparing various theoretical foundations to build disaster preparedness and resilience by analyzing various literary works related to disasters, including essays.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.-A.K., J.-E.L., E.S. and S.I.R.; methodology, S.-A.K. and S.I.R. software, E.S.; validation, J.-E.L. and S.-A.K.; formal analysis, S.-A.K.; investigation, E.S.; resources, S.-A.K.; data curation, S.-A.K. and J.-E.L.; writing—original draft preparation, S.-A.K., S.I.R. and E.S.; writing—review and editing, S.-A.K. and J.-E.L.; visualization, S.-A.K.; supervision, J.-E.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2020S1A5B8103910).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We express our gratitude to Changbi for allowing us to analyze the works The Day Knocked on Our Window and Spring Will Come Again.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Abrahams, Jonathan. 2001. Disaster management in Australia: The national emergency management system. Emergency Medicine 13: 165–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alazawi, Zubaida, Saleh Altowaijri, Rashid Mehmood, and Mohmmad B. Abdljabar. 2011. Intelligent disaster management system based on cloud-enabled vehicular networks. Paper presented at 2011 11th International Conference on ITS Telecommunications, Graz, Austria, June 15–17; pp. 361–68. [Google Scholar]

- Altieri, Jennifer L. 1993. African-American stories and literary responses: Does a child’s ethnicity affect the focus of a response? Reading Horizons 3: 33. [Google Scholar]

- Amado, Alexandra, Paulo Cortez, Paulo Rita, and Sergio Moro. 2018. Research trends on big data in marketing: A text mining and topic modeling based literature analysis. European Research on Management and Business Economics 24: 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, Cameron, and S. Curnin. 2020. Sharing responsibility in disaster management policy. Progress in Disaster Science 7: 100122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajek, Robert, Yoko Matsuda, and Norio Okada. 2008. Japan’s Jishu-bosai-soshiki community activities: Analysis of its role in participatory community disaster risk management. Natural Hazards 44: 281–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baque, Giulia. 2019. Environmental Disaster in Japanese Literature: Narrativizations of Time and Space in Oe Kenzaburo’s Somersault. Ph.D. dissertation, Leiden University, Leiden, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya, Sourit. 2020. Disaster and Realism: Novels of the 1943 Bengal Famine. In Postcolonial Modernity and the Indian Novel. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 41–95. [Google Scholar]

- Boelen, Paul A., Marcel A. van den Hout, and Jan van den Bout. 2008. Factor structure of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms among bereaved individuals: A confirmatory factor analysis study. Journal of Anxiety Disorder 22: 1377–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonacich, Philip. 1987. Power and centrality: A family of measures. American Journal of Sociology 92: 1170–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bountress, Kaitlin E., Amanda K. Gilmore, Isha W. Metzger, Steven H. Aggen, Rachel L. Tomko, Carla Kmett Danielson, Vernell Williamson, Vladimir Vladmirov, Kenneth Ruggiero, and Ananda B. Amstadter. 2020. Impact of disaster exposure severity: Cascading effects across parental distress, adolescent PTSD symptoms, as well as parent-child conflict and communication. Social Science & Medicine 264: 113293. [Google Scholar]

- Buckland, Jerry, and Matiur Rahman. 1999. Community-based disaster management during the 1997 Red River flood in Canada. Disasters 23: 174–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Xiaoyi, Xiaolian Jiang, Xialin Li, Man-Chun J. H. Lo, Rong Li, and Xinman Dou. 2013. Perceived family functioning and depression in bereaved parents in China after the 2008 Sichuan earthquake. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing 27: 204–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Careem, Mifan, Chamindra De Silva, Ravindra De Silva, Louiqa Raschid, and Sanjiva Weerawarana. 2006. Sahana: Overview of a disaster management system. Paper presented at 2006 International Conference on Information and Automation, Colombo, Sri Lanka, December 15–17; Vol. 69, pp. 361–66. [Google Scholar]

- Chae, Jeong-Ho, Hyu Jung Huh, and Won Joon Choi. 2018. Embitterment and bereavement: Example of the Sewol ferry accident. Psychological Trauma Theory Research Practice and Policy 10: 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Sujin, Hyopil Shin, and Seungshik S. Kang. 2021. Predicting audience-rated news quality: Using survey, text mining, and neural network methods. Digital Journalism 9: 84–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chovanec, Jan. 2019. Early Titanic Jokes: A disaster for the theory of disaster jokes? Humor 32: 201–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, Ji-Bum, Eugene Choi, Leo Kim, and Byeong Je Kim. 2021. Politicization of a disaster and victim blaming: Analysis of the sewol ferry case in Korea. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 69: 102742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, Norma. 2005. Bluestocking fiction: Devotional writings, didactic literature, and the imperative of female improvement. In Women, Gender and Enlightenment, 1st ed. Edited by S. Knott and B. Taylor. London: Palgrave MacMillan, pp. 460–73. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, Howard. 2013. Taking crime seriously? Disaster, victimization, and justice. In Expanding the Criminological Imagination. Edited by A. Barton, K. Corteen, D. Scott and D. Whyte. Devon: Willan Publishing, pp. 148–79. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, Howard, and Phil Scraton. 1999. Institutionalised conflict and the subordination of ‘loss’ in the immediate aftermath of UK mass fatality disasters. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management 7: 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demers, Patricia. 1993. Heaven Upon Earth the Form of Moral and Religious Children’s Literature to 1850. PhilArchive Copy v1. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, Available online: https://philpapers.org/rec/DEMHUE-2 (accessed on 1 March 2021).

- Doerfel, Marya L., and Stacey L. Connaughton. 2009. Semantic networks and competition: Election year winners and losers in US televised presidential debates, 1960–2004. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 60: 201–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorn, Tina, C. Joris Yzermans, Jan J. Kerssens, Peter M. Spreeuwenberg, and Jouke van der Zee. 2006. Disaster and subsequent healthcare utilization: A longitudinal study of victims, their family members, and control subjects. Medical Care 44: 581–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fajardo, Jovilyn Therese B., and Carlos Oppous. 2010. Mobile disaster management system using Android technology. WSEAS Transactions and Communications 9: 343–53. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez, Cristina A., Benjamin Vicente, Brandon D. Marshall, Karestan C. Koenen, Kristopher L. Arheart, Robert Kohn, Sandra Saldivia, and Stephen L. Buka. 2017. Longitudinal course of disaster-related PTSD among a prospective sample of adult Chilean natural disaster survivors. International Journal of Epidemiology 46: 440–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sewol Ferry Disaster Writers Records. 2016. Spring Will Come Again. Seoul: Changbi, Available online: https://www.changbi.com/books/65149?board_id=9601 (accessed on 1 March 2021).

- Sewol Ferry Disaster Writers Records. 2019. The Day Knocked on Our Window. Seoul: Changbi, Available online: https://www.changbi.com/books/78293?board_id=11595 (accessed on 1 March 2021).

- Gardner, William O. 2014. Narratives of collapse and generation: Komatsu Sakyō’s disaster novels and the Metabolist Movement. Japan Forum 26: 306–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleser, Goldine C., Bonnie L. Green, and Carolyn N. Winget. 1978. Quantifying interview data on psychic impairment of disaster survivors. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 166: 209–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, Bonnie L., Mary C. Grace, Marshall G. Vary, Teresa L. Kramer, Goldine C. Gleser, and Anthony C. Leonard. 1994. Children of disaster in the second decade: A 17-year follow-up of Buffalo Creek survivors. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 33: 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamblen, Jessica L., Fran H. Norris, Kerry A. Symon, and Thomas E. Bow. 2017. Cognitive behavioral therapy for postdisaster distress: A promising transdiagnostic approach to treating disaster survivors. Psychological Trauma: Theory Research Practice and Policy 9: 130–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Soon-Mi. 2020. Disaster Humanities after the Pandemic. Journal of Humanities Therapy 11: 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Kyung Hoon, Young Su Seo, and Geun Byung Park. 2015. Structural Analysis of Subway Station Network Using Social Network Analysis. Seoul: The Korean Society for Railway, Available online: http://railway.or.kr/Papers_Conference/201501/pdf/KSR2015S008.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2021).

- Huh, Hyu J., Seung Huh, So H. Lee, and Jeong-He Chae. 2017. Unresolved bereavement and other mental health problems in parents of the Sewol ferry accident after 18 months. Psychiatry Investigation 14: 231–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hur, Myung-Hoe. 2010. Introduction to Social Network Analysis Using R, 1st ed. Seoul: Freeacademy Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Ilbo, Segye. 2017. Unhealed Wounds… Parents’ Minds Are Still Trapped in a “Child Swallowed Belly”. Available online: http://www.segye.com/newsView/20170414002601?OutUrl=naver (accessed on 14 April 2021).

- Iwata-Weickgenannt, Kristina. 2019. The roads to disaster, or rewriting history from the margins—Yū Miri’s JR Ueno Station Park Exit. Contemporary Japan 31: 180–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Jeong-Woo, and Kyoung-Ho Choi. 2012. Statistics act analysis using semantic network analysis. Journal of Korean Official Statistics 17: 53–66. Available online: www.kci.go.kr/kciportal/ci/sereArticleSearch/ciSereArtiView.kci?sereArticleSearchBean.artiId=ART001708697 (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Jha, Maya N., Jason Levy, and Yang Gao. 2008. Advances in remote sensing for oil spill disaster management: State-of-the-art sensor technology for oil spill surveillance. Sensors 8: 236–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jong, Wouter, and Michel L. A. Dückers. 2019. The perspective of the affected: What people are confronted with disasters is expected from government officials and public leaders. Risk Hazards and Crisis in Public Policy 10: 14–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Joseph, Steve, Bernice Andrews, Ruth Williams, and William Yule. 1992. Crisis support and psychiatric symptomatology in adult survivors of the Jupiter cruise ship disaster. British Journal of Clinical Psychology 31: 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, Joo-Young. 2019. Socio-psychological recovery from disasters through the neighborhood storytelling network: Empirical research in Shinchimachi, Fukushima. International Journal of Communication 13: 21. [Google Scholar]

- Kalocsányiová, Erika, and Malika Shatnawi. 2021. ‘He was obliged to seek refuge’: An illustrative example of a cross-language interview analysis. Qualitative Research 21: 846–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, EunKyo. 2021. Impact of disasters on community medical screening examination and vaccination rates: The case of the Sewol Ferry Disaster in Ansan, Korea. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness 15: 286–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, Wook G., Yui S. Ko, Hak R. Lee, and Jai L. Kim. 2018. A study of the consumer major perception of packaging using big data analysis -Focusing on text mining and semantic network analysis. Journal of the Korea Convergence Society 9: 15–22. [Google Scholar]

- Kansra, Deepa. 2019. International Human Rights Framework and Disasters. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3656196 (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Kee, Dohyung, Gyuchan T. Jun, Patrick Waterson, and Roger Haslam. 2017. A systemic analysis of the South Korean Sewol ferry accident—Striking a balance between learning and accountability. Applied Ergonomics 59: 504–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kirschenbaum, Alan. 2019. Chaos Organization and Disaster Management, 1st ed. London: Routledge, pp. 1–336. [Google Scholar]

- Kristensen, Pal, Lars Weisaeth, and Trond Heir. 2010. Predictors of complicated grief after a natural disaster: A population study two years after the 2004 Southeast Asian tsunami. Death Studies 34: 137–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laksmita, Okki D., Min-Huey Chung, Yuan-Mei Liao, Joan E. Haase, and Pi-Chen Chang. 2020. Predictors of resilience among adolescent disaster survivors: Path analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing 76: 2060–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Roux, Isabella H., and Vanessa E. Cobham. 2021. Psychological interventions for children experiencing PTSD after exposure to a natural disaster: A scoping review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Dong Hun, and Minsoo Khang. 2020. Parenting school-aged children after the death of a child: A qualitative study on victims’ families of the Sewol ferry disaster in South Korea. Death Studies 44: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Ju-Yeon, Sung-Wan Kim, and Jae-Min Kim. 2020. The impact of community disaster trauma: A focus on emerging research of PTSD and other mental health outcomes. Chonnam Medical Journal 56: 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Mina N., and Juhyun H. Hong. 2016. Semantic network analysis of government’s crisis communication messages during the MERS outbreak. The Journal of the Korea Contents Association 16: 124–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, Nabin, Jiwon Min, Sangwoo Han, Kanguk Lee, Minyoung Shim, Jeong-Ho Chae, and Hyunnie Ahn. 2017. Exploring bereaved family members grief process and experiences toward disaster support services based on the interviews with disaster support workers at Sewol ferry accident. Ment. Health Soc. Work 45: 5–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Sang Min, Hyesung Han, Kuk-In Jang, Seung Huh, Hyu Jung Huh, Ji-Young Joo, and Jeong-Ho Chae. 2018a. Heart rate variability associated with posttraumatic stress disorder in victims’ families of Sewol ferry disaster. Psychiatry Research 259: 277–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, So Hee, Eun Ji Kim, Jin-Won Noh, and Jeong-Ho Chae. 2018b. Factors associated with post-traumatic stress symptoms in students who survived 20 months after the Sewol ferry disaster in Korea. Journal of Korean Medical Science 33: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenferink, Lonneke I. M., Jos de Keijser, Geert E. Smid, A. A. A. Manik J. Djelantik, and Paul A. Boelen. 2017. Prolonged grief, depression, and posttraumatic stress in disaster-bereaved individuals: Latent class analysis. European Journal of Psychotraumatology 8: 1298311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lim, Eun J., and Soon H. Joung. 2019. A study on social issues according to expansion of carpool service. Journal of Consumer Culture 22: 19–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liverman, Diana M., and Douglas R. Sherman. 2015. Natural hazards in novels and films: Implications for hazard perception and behaviour. In Geography, the Media and Popular Culture. London: Routledge, pp. 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, Sarah R., Megan N. Young, Joie Acosta, Laura Sampson, Oliver Gruebner, and Sandra Galea. 2018. Disaster survivors’ anticipated received support in future disasters. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness 12: 711–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahn, Churnjeet, Caroline Scarles, Justin Edwards, and John Tribe. 2021. Personalising disaster: Community storytelling and sharing in New Orleans post-Katrina tourism. Tourist Studies 21: 156–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massazza, Alessandro, Helene Joffe, Philip Hyland, and Chris R. Brewin. 2021. The structure of peritraumatic reactions and their relationship with PTSD among disaster survivors. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 130: 248–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meduri, Yamini. 2021. Personnel needs assessment in times of crisis: A focus on management of disasters. RAUSP Management Journal 56: 390–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mika, Kasia. 2018. Disasters, Vulnerability, and Narratives: Writing Haiti’s Futures. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, Louise, Jane Scourfield, David Williams, Anne Jasper, and Glyn Lewis. 2003. The Aberfan disaster: 33-year follow-up of survivors. The British Journal of Psychiatry 182: 532–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mosby, Kim, Traci Birch, Aimee Moles, and Katie E. Cherry. 2021. Disasters. In Handbook of Rural Aging. London: Routledge, pp. 111–15. [Google Scholar]

- North, Carol S., Erin Van Enkevort, Barry A. Hong, and Alina M. Surís. 2020. Association of PTSD symptom groups with functional impairment and distress in trauma-exposed disaster survivors. Psychological Medicine 50: 1556–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, Gi-Muk. 2015. A technical approach to post-traumatic stress disorder of the Sewol ferry victims’ parents. The Journal of Korea Contents Association 15: 134–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Ji-Min, and Sung-Man Bae. 2022. Impact of depressive, anxiety, and PTSD symptoms in disaster victims on quality of life: The moderating effect of perceived community resilience. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 69: 102749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potts, Adam. 2018. SOUNDS OF DISASTER: Sonic encounters with blanchot. Angelaki 23: 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Quarantelli, Enrico Louis. 1980. Study of Disaster Movies: Research Problems, Findings, and Implications. Available online: http://udspace.udel.edu/handle/19716/447 (accessed on 14 April 2021).

- Razi, A. 2012. Didactic functions of Persian literature. Didactic Literature Review 4: 97–120. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, Jorge J., and Robert Kohn. 2008. Use of mental health services among disaster survivors. Current Opinion in Psychiatry 21: 370–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapach, Sonja. 2020. Tagging my tears and fears: Text-mining the autoethnography. Digital Studies/Le Champ Numerique 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano-Muñoz, Jordi. 2019. Reading after the Disaster. Education About Asia 24: 30–35. [Google Scholar]

- Shang, Fanhong, Krzysztof Kaniasty, Sean Cowlishaw, Darryl Wade, Hong Ma, and David Forbes. 2019. Social support following a natural disaster: A longitudinal study of survivors of the 2013 Lushan earthquake in China. Psychiatry Research 273: 641–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solnit, Rebecca. 2010. A Paradise Built in Hell: The Extraordinary Communities That Arise in a Disaster, 1st ed. New York: Penguin, pp. 1–368. [Google Scholar]

- Son, D. W. 2002. Social Network Analysis, 1st ed. Seoul: Kyung Moonsa, pp. 1–254. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, E., H. Iso, A. Tsutsumi, S. Kameoka, Y. You, and H. Kato. 2020. School-based psychoeducation and storytelling: Associations with long-term mental health in adolescent survivors of the Wenchuan earthquake. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Thornber, Karen. 2021. Fukushima Fiction: The Literary Landscape of Japan’s Triple Disaster by Rachel Di Nitto, and: The Earth Writes: The Great Earthquake and the Novel in Post—3/11 Japan by Koichi Haga. The Journal of Japanese Studies 47: 259–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turudić, Marko, and Bosiljka Britvić Vetma. 2021. State and compensation in case of natural disasters-on legal protection and transparency. Zbornik Radova Pravnog Fakulteta u Splitu 58: 441–58. [Google Scholar]

- Tyler, Jenna, and Abdul-Akeem Sadiq. 2018. Friends and family vs. government: Who does the public rely on more to prepare for natural disasters? Environmental Hazards 17: 234–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uekusa, Shinya. 2019. Disaster linguicism: Linguistic minorities in disasters. Language in Society 48: 353–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Uyheng, Joshua. 2020. ORDINARINESS IN DISASTER: Notes from Rereading Story during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Perspectives in the Arts & Humanities Asia 10: 183–207. [Google Scholar]

- Van Oosterom, Peter, Siyka Zlatanova, and Elfriede M. Fendel. 2006. Geo-Information for Disaster Management, 1st ed. Berlin: Springer, pp. 393–519. [Google Scholar]

- White, Mark B. 1998. The rhetoric of edification: African American didactic literature and the ethical function of epideictic. Howard Journal of Communication 9: 125–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, Hyekyung, Youngtae Cho, Shim Eunyoung, Kihwang Lee, and Gilyoung Song. 2015. Public trauma after the Sewol ferry disaster: The role of social media in understanding the public mood. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 12: 10974–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yang, Hee Jung, Hae Kwan Cheong, Bo Youl Choi, Min-Ho Shin, Hyeon Woo Yim, Kim Dong-Hyun, Kim Gawon, and Soon Young Lee. 2015. Community mental health status six months after the Sewol ferry disaster in Ansan, Korea. Epidemiology and Health 37: e2015046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yari, Arezoo, Ali Ardalan, Abbas Ostadtaghizadeh, Yadolah Zarezadeh, Mohsen Soufi Boubakran, Farzam Bidarpoor, and Abbas Rahimiforoushani. 2019. Underlying factors affecting death due to flood in Iran: A qualitative content analysis. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 40: 101258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).