Abstract

Sexualized substance use or ‘chemsex’ is a key element in the syndemic of violence and infection in gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men. Chemsex is more prolific amongst men who have sex with men but is also associated with high risk behaviours that can negatively impact on health and wellbeing in heterosexual, bisexual men and women, and in homosexual women too. This qualitative study investigated perceptions and experiences of chemsex, motivations, cisgender male sex work, consent, economic exploitation, and ways to address and reduce harms. We conducted semi-structured interviews with health care providers and their clients—including sex workers and their customers (n = 14) between the ages of 28 and 46 years following a purposive sampling strategy. Interview topics included perceptions and experiences of chemsex use, reasons for drug use and chemsex, and proposals to address harms associated with chemsex in the UK. Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed, coded, and analysed using Grounded Theory. The findings revealed a stepwise process of chemsex use in a ‘ladder of consent’, whereby the process starts with willing participation that is both highly pleasurable and controllable. Sexual polydrug activity often descended in rungs so that lines of consent became blurred, and even broken, resulting in physical detriment and financial exploitation. Strategies for elevation back up the consent ladder also emerged. The findings clarify the conditions of willing participation, the stepwise relationship to exploitation, and the support strategies that help re-empower individuals whose lives get taken over by chemsex, including peer-to-peer support, poly-centres, and smartphone apps to climb back up the consent ladder to improve the health, safety, and social rights of sex workers.

Keywords:

consent; chemsex; sex work; MSW; men who have sex with men; MSM; qualitative; Grounded Theory 1. Introduction

1.1. Sex Work

Sex work has moved, like so much other commerce, from print-based advertising onto smartphone apps, as well as website chatrooms and web-based geosocial networking apps (MacPhail et al. 2015; Morris 2018). Male sex workers commonly use apps to recruit clients, and such e-commerce brings with it the ability to screen clients, organise payment, and state what they are willing to offer before meeting (McLean 2015). Smartphone apps make it easy to invite people to come to the sex parties which usually take place in private residences (Ahmed et al. 2016) and to purchase sex or drugs, so technology has had an integral role in the relationship between sex work and chemsex (Stuart 2019). Gay men already face social stigma for their sexuality, and Perkins and Bennett (1985) theorized that entering sex work is easier after having already broken one social taboo. Similar hypotheses have been made about drug taking. The high saturation of male sex workers (MSW) means that it is not unknown for MSW to offer services, such as chemsex, that are sexually risky owing to the level of competition (MacPhail et al. 2015).

Selling sexual services is a stigmatised activity, and possession of the three main chemsex drugs is a criminal act in the United Kingdom. As most male sex workers wait until after services to receive payment, chemsex also increases the risk of financial exploitation. This combination of factors can create an exploitative and possibly dangerous work environment in which ethical and legal questions are raised around consent if someone falls unconscious because of overdosing (Adfam 2019). It would be very difficult for a sex worker, if they were to overdose, to consent to any sexual activity that subsequently happens.

1.2. Chemsex

Chemsex is ordinarily understood as being sexual activities while under the influence of drugs. It emerged as a notable issue in the 2000’s and often involves group sex or a high number of partners in one session (also called party and play (PnP)) (Bourne et al. 2014). It is a widespread practice, and chemsex is known to occur across high income countries in Europe including Germany (Graf et al. 2018; Deimel et al. 2016), The Netherlands (Evers et al. 2020), Ireland (Van Hout et al. 2019), the USA (Spinelli et al. 2020; Okafor et al. 2020), Canada (Chettiar et al. 2010; Flores-Aranda et al. 2019), Singapore (Tan et al. 2018), and Hong Kong (Wang et al. 2020). Studies show that there have been changes in chemsex and sexual behaviour over the past twenty years (Sewell et al. 2019) and that the practice of chemsex is ever-changing as markets of paid labour and drug consumption evolve (Pirani et al. 2019).

Men who have sex with men (MSM) have higher rates of drug use compared to the general population, including the use of mephedrone1, crystal methamphetamine2, gamma-hydroxybutrate (GHB)/gamma-butryrolactone (GBL)3, ketamine, cocaine, cannabis, ecstasy/MDMA, volatile nitrites (poppers), and sildenafil (Viagra). Traditional ‘club’ drug, such as ecstasy and cocaine, appear to have given way to the increasingly popular chemsex drugs, in part due to their ability to increase and sustain sexual arousal for extended periods of time. Chemsex is not necessarily commonplace among the general MSM population but use of other harmful drugs is high among MSM (and bisexual and men and women), who do engage in chemsex (Kohli et al. 2019; Lawn et al. 2019). In the past five years, researchers have reported a rise in the use of three drugs used to facilitate, elongate, and enhance sexual activities in chemsex (Stuart 2019).

The drugs most commonly used in chemsex are mephedrone, crystal methamphetamine (meth), and GHB/GBL. These drugs bring risks because mephedrone and crystal meth can induce psychosis, and GHB/GBL is easy to overdose on (Adfam 2019). All three main chemsex drugs can cause a psychological reliance on them, and GHB is commonly overdosed on because the difference between being intoxicated and falling into a coma is minimal, and levels above forty milligrams can be fatal (Oliveto et al. 2010; McCall et al. 2015). Due to the illegal status of GHB, it is difficult for its consumers to ascertain its concentration, which can vary from 1 mg to 40 mgs (Galicia et al. 2011), and this lack of regulation means that users can accidently overdose when GHB is highly concentrated. Indeed, one in five users have reported overdosing within a one-year period (Winstock 2015). Mephedrone was a so-called ‘legal high’ until 2010, and it has similar qualities and effects as amphetamines and can interfere and inhibit short-term memory. Overdosing on the drug can cause the body to overheat or elevate the user’s heartbeat, and mixing it with other stimulants can increase these effects (Bourne et al. 2014). Methamphetamine, on the other hand, has been reportedly used to stay awake, enhance energy, and also inhibit appetite. Some men have also been known to have erectile problems while taking it so have used sildenafil (Viagra) to counterbalance those effects (Schilder et al. 2005). Methamphetamine may also have long term effects of psychosis, exhaustion, and damage to various tissues (Bourne et al. 2014).

The drugs are taken orally or anally in a practice known as ‘booty bumping’, and there is a sub-group of users who inject the drugs, which is known as ‘slamsex’ (Pakianathan et al. 2016). To a lesser extent, cocaine, ketamine, and other illicit drugs are used (Bourne et al. 2014; Bourne et al. 2015). A thematic analysis by Bourne et al. (2014) of 30 interviews with men in south London who had used the three chemsex drugs in the year of the interview found that the irregular concentration of GHB/GBL could cause overdosing, and the majority of their participants reported overdosing for this reason. A small proportion of participants reported issues around consent while under the influence of the drugs. Others raised concerns about the drugs causing harm to mental or physical wellbeing as the stigma around taking part in Chemsex-related activities precluded them from accessing harm reduction services.

The motivations and values around combining sex and illicit drugs was qualitatively studied by Weatherburn et al. (2017), and the experiences of current and former methamphetamine takers was documented by Flores-Aranda et al. (2019) in Canada to explore crystal meth patterns and their use of services related to chemsex practice. Participants reported feeling more confident with their partners and feeling more sexually attractive, and they were more able to overcome their barriers to sexuality. The intensification of drug use, and in particular injection use, could change the positive perception of sexual life. Thus, for some participants, substance use takes more space and their sexual experiences become less satisfactory.

Sexual health services face growing challenges from bacterial STIs, which have reached record levels among MSM, for example (Kohli et al. 2019). In data from 16,065 respondents in a cross-sectional analysis by Kohli et al. (2019), the use of chemsex drugs has been associated with higher rates and risks of antibiotic resistant gonorrhea. Combining sex and drugs, including oral erectile dysfunction medication, has been found to be associated with high-risk sexual behaviours and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). The increasing prevalence and awareness of chemsex poses a serious public health challenge for health professionals and social scientists attempting to understand the motivations and risks involved and to avoid the pain illustrated in many survival stories (e.g., Smith and Tasker 2018).

1.3. Stigma

As chemsex has been linked to having lots of sexual partners, Giorgetti et al. (2017) looked at the chemical effects and damage that regular chemsex drug use has on the body of the individuals, along with the cultural and social factors behind it. They found that people could experience rectal trauma, penile abrasions, and a higher risk of contracting STI’s. Their findings are informative for health providers as regards the common signs and symptoms of an overdose. They also suggested that the shame and stigma of taking part in chemsex related activities needed to be researched more, and solutions found to reduce these may also be required.

The effects that chemsex drug use had on health outcomes for MSM was studied by Stevens et al. (2019) in a cross-sectional analysis of clients of the clinic Antidote. They found that men who accessed services for chemsex use were more likely to be HIV+, to have injected drugs, used pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) within the last year, and have had six or more sexual partners in the previous ninety days. They found a link between drugs and clients who were younger and employed, who were more likely to use mephedrone. They also found that the use of GHB/GBL independently meant that the individuals were less likely to inject drugs or be HIV+, though there were also higher reports of suicidal ideation. Such findings suggest that a wide range of issues arise when individuals take part in chemsex, but their needs are not met by current health service provision. They also commented on a lack of effective communication between drug and sexual health services and a need for chemsex surveillance. They suggested that chemsex should be viewed as a higher risk for MSM than alcohol or cocaine. Stevens et al. (2019) also suggested that building services around the issues would enable adaptation of the services as needed.

1.4. Contemporary Policy Concern

Chemsex drugs emerged as an area of concern to policymakers in the wake of some high profile court cases. First, in the case of Stephen Port, the coroner reported that he had used lethal doses of GHB, which had consequently killed four young men. Port was charged with rape, sexual assault, and murder. The case hints at a form of sexual gratification gained from purposefully overdosing and raping men (Davies 2016). Videos were used as evidence showing that men were intentionally drugged to the point of passing out before Mr Port carried out sexual acts on them. The case highlighted a lack of police education around the drugs, as they were not able to connect the murders through the drug GHB, and it drew attention to the possible stigma around the drugs, which could hinder harm reduction efforts (Davies 2016). In January 2020, the case of Reynhard Sinaga brought chemsex drugs to the fore when he was convicted of 159 cases across four separate trials including 136 unprotected anal rapes he filmed on two mobile phones. He spiked victims’ drinks with a substance, thought to be GHB, to render them unconscious. The CPS North West Crown Prosecutor said that “the issue for prosecutors was largely one of proving a lack of consent” (Crown Prosecution Service 2020). These cases of evident criminality contrast with the case of Alexander Parkin which was prosecuted following the death of 18 year old Miguel Jimenez, the boyfriend of a London barrister, Henry Hendron. The 45 year old Parkin faced trial in 2017 over claims he sold crystal meth, ecstasy, and ‘liquid ecstasy’ GBL from his flat in London. He was sentenced to community service for supplying Henry Hendron with drugs, and in September 2020 Parkin was arrested and then tried in November 2020 for possession with intent to supply £13,000 worth of Class A to C drugs. A report on Parkin stated that a “former BBC radio producer who became the ‘go-to-guy’ on the Chemsex drugs scene is facing a jail sentence for dealing in crystal meth” (Kirk 2020). While there is a vast difference between the first two cases of obvious criminal predation and the latter one of a tragic accident, these cases all raised the profile of chemsex drugs to policy makers.

1.5. Policy Context in the UK

As GHB/GBL are class C drugs under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 (2019), mephedrone is a class B drug, and crystal methamphetamine is a class A drug, all can carry a prison sentence, a fine, or both, if found in a person’s possession. Given the clear evidence from the research literature about the need for a supportive role for policy and the commissioning environment for chemsex in England the Advisory Committee for the Misuse of Drugs (ACMD) prioritised a workstream on chemsex to involve a consultation with a range of stakeholders and provide advice on other approaches of value in reducing the availability, demand, and harms of GHB, GBL, and closely related compounds. The initial advice of the ACMD was expected by Autumn 2020 in a letter from Prof Owen Bowden-Jones to Rt. Hon. Priti Patel, MP, ACMD (2020). On 6 January 2020, however, Home Secretary Priti Patel commissioned the Advisory Committee for the Misuse of Drugs (ACMD) to carry out an urgent review of the classification of gamma-hydroxybutyric acid (GHB) and gamma-butryrolactone (GBL) and closely related compounds under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 (2019) and the scheduling of both drugs under the Misuse of Drugs Regulation 2001. The course of policy consultation has thus shifted from service provision towards a more penal direction despite the fact that tougher penal postures are never the answer to public health questions. Chemsex drugs are specifically used to enhance and facilitate sex and can blur lines of consent—a concept which remains under-researched and under-theorised in a chemsex context. It is to be hoped that a greater understanding of consent will improve service approaches.

1.6. Service Approaches

Service funding often focuses support more on heroine, crack cocaine, and alcohol, and chemsex users and professionals report that referral to these mainstream drug services would be unsuitable for chemsex participants (McCall et al. 2015). Researchers have started to explore the psychosocial and sexual characteristics associated with chemsex (Parry et al. 2017; Hibbert et al. 2019), and in a continuum of care it has been suggested that general practitioners (GPs) may have a valuable harm reduction role in this growing phenomenon (Ma and Perrera 2016; Bakker and Knoops 2018). Studies of tailored services have met with some success, for example, in a prospective cohort study by Sewell et al. (2019) which investigated changes in chemsex activity of 1167 MSM over a three year period using online questionnaires. In a large longitudinal study, they explored the use of three chemsex drugs (mephedrone, crystal meth, and GHB/GBL), the frequency of chemsex sessions, and measures of sexual behaviour. They found chemsex and the use of two drugs in particular, mephedrone and GHB/GBL, significantly declined, alongside most measures of sexual behaviour, with the exception of condomless anal intercourse (CLAI) with more than one or more than two partners. The study shows a strong negative association between time spent on the study and mephedrone and GHB/GBL, but not crystal methamphetamine. One reason for their findings on the reduction in chemsex prevalence and chemsex specific drugs could be that the specialist centres for chemsex support, where interventions were specifically tailored to MSM reporting chemsex, means that their results may be a reflection on the effectiveness of specialist services at providing support and interventions to reduce chemsex among a specific group of MSM (Sewell et al. 2019), such as sex workers. Furthermore, engagement with questionnaires that encourage reflection on behaviour may play a part as participants become more conscious of the consequences of their choices, which could have led to behaviour change on sexual risk behaviours, STI diagnosis, and HIV testing over time. In addition, a study by Evers et al. (2020) showed that almost one in four MSM practicing chemsex expressed a need for professional counselling on chemsex-related issues. They recommended that STI healthcare providers should assess the need for professional counselling in MSM practicing chemsex, especially in MSM with the above-mentioned characteristics. Following an authoritative systematic review, Maxwell et al. (2019) found that while a minority of MSM engage in chemsex behaviours, these men are at risk of it negatively impacting on their health and well-being, and further research is required to examine high risk chemsex behaviours, impacts of chemsex on psycho-social well-being, and if chemsex influences uptake of PrEP and sexual health screening. In this context, few activities are higher risk than commercial sexual activity.

1.7. Aims

Specialist services were scarce, even before the Sars-CoV-2 global pandemic impacted on all health services, with very few services available to reduce harms and increase safety. It is a key area of public health concern to promote the health and wellbeing of MSM, especially MSW, to develop best practice for specialist support services that address the phenomenon of chemsex. This paper will explore the potential harm connected to the taking of these drugs that sex workers may face. It will examine the dangers that health professionals working in the field highlight, what campaigners observe, and how those who take part in chemsex activity view the intended and unintended effects of policy frameworks and legal regulation on commercial chemsex in a UK context. Furthermore, we aim to clarify conditions of exploitation that can occur in consensual activity and identify any possible new methods, policies, and regulations to improve the health and safety of MSW so that harms can be minimised or eradicated and stigma reduced in both occupational and leisure settings.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Procedure

Participants were recruited through a purposive sampling strategy; the first bloc of participants gave evidence to a policy working group on harm reduction in sex work for a national political party which was chaired by the first author (Phase 1). When the first bloc of participants was interviewed, it was by the policy working group (comprising 8–10 people) and often in pairs. These participants were all interviewed on the Parliamentary estate (usually Portcullis House) in London, England. From their evidence, chemsex emerged as a serious issue in need of a tailored and specific research study, and these sessions provided the material for the formal interview questions. A further study (Phase 2) was carried out to interview people one-to-one. In Phase 2, participants were provided the interview schedule prior to their interview, as the purpose was to gain their expert knowledge and opinion. Participants chose a place and a time to be interviewed that suited them. The majority of interviews took place in a quiet room in the faculty building; two interviews took place over the telephone. In both studies, sex work was operationally defined as ‘the exchange of money (or its equivalent) for the provision of a sexual service between consenting adults within the terms agreed by the seller and the buyer’ and as such it was considered as paid labour that may involve economic exploitation. Individuals carrying out such labour should have recourse to the same government protection, occupational, and social rights extended to other workers (see Brooks-Gordon et al. 2017).

2.2. Interviews

Semi-structured interviews were conducted, and interview questions formulated from the evidence on chemsex, the growing literature on chemsex, and on male sex work. The interviews lasted approximately forty minutes and were recorded with the participants’ informed consent. The interview schedule was drafted and then tailored to each participant, depending on their role; this was reviewed after each interview, and the schedule evolved as the transcripts were reviewed by the authors. Interviews initially covered inter alia: experiences of chemsex and male sex work through their role; emerging issues in male sex work caseload; HIV, STIs, and antiretrovirals; main issues with associated activities like slamsex; safety protocols around the drugs taken to facilitate chem/slamsex; and what the state and/or health service protection would look like. These were extended throughout the data gathering process via theoretical sampling to embrace issues that arose, including: facilitators and/or barriers to exploitation; health, safety, and social rights; trends in practices among MSM; best methods of supporting (mental/physical/social); and adequate support within chemsex contexts to ensure safety for sex workers and men who have sex with men.

2.3. Participants

Participants comprised clinical service providers, health professionals, and advocates and campaigners who support sex workers and/or antiretroviral therapy (ART) promotion. There were fourteen participants comprising 10 men and 2 women; all participants were allocated a pseudonym in the transcripts for anonymity. Some were past chemsex participants themselves, others had either paid for or sold sex on an incidental basis as well. Interviewees’ roles ranged from clinical psychologists, health counsellors, homelessness hostel staff, sexual health clinic practitioners, community mental health clinicians, police drug advisors, a mental health lead in a drug addiction charity, an NGO sex work charity project manager, and PrEP charity advocates. All either had a caseload that included clients who had taken part in chemsex, were recovering drug users themselves, or had taken part in chemsex and occasionally sold sex or hired male sex workers. Participants’ ages ranged between 28 and 46 years, and they were anonymised, respectively, as: Sarah, Freya, Andrew, Mark, James, Bryan, Casey, Ged, Hal, Peter, Raj, Uvi, and Sven. The women both identified as heterosexual and cisgender, and the men all identified as gay cisgender men. All participants were delivering the support to people involved in these activities, so were able to provide up-to-date information on what is happening in an ever-changing phenomenon and were able to report and discuss current thinking and developments from the ‘front-line’. Most participants lived in or near London, with others from Brighton, Birmingham, Manchester, Coventry, Scotland, and Liverpool.

2.4. Analysis

Grounded Theory, which is the process of developing and creating theories grounded in the data, was used to analyse the interview transcripts. After initial and axial coding and saturation is achieved, the theory emerges from the data (Glaser and Strauss 1967). The process requires the constant comparative analysis of the transcripts. This iterative process helped the researchers to uncover one core category and various sub-categories, along with the properties and dimensions of the emerging theory, as specific key concepts, which are described reflexively below, emerged and were all followed up in the research.

2.5. Materials

The recording app on an iPhone 5s and a Victure Digital Voice Recorder were used to record the interviews so that the data could be transcribed. Two interviews carried out over the phone were recorded on the voice recorder. The website OTranscribe.com was used to transcribe the data.

2.6. Ethical Approval

Ethical approval was granted by the Ethics Committee in the School of Psychology at Birkbeck, University of London. Informed consent was given via email before the interviews and also written and signed by both the researchers and participants when they met. The ethical guidelines of both the British Sociological Society and the British Psychological Society were closely adhered to, and participants had the right to withdraw their data at any time. Participants were informed about all aspects of the project and debriefed after the interview.

2.7. Reflexivity

One of the authors, who identifies as gay, held a priori some of the concerns that participants brought up and it had underpinned his interested in the topic, which is that young men coming into the gay scene may consider chemsex as the archetype of gay sex. This was a motivating factor for working on the project. This issue, however, would prove to be a function of lack of education around chemsex rather than a widely held view as the research progressed and featured less in the interviews than initially expected. The first author’s motivation was to uncover hitherto unknown aspects of a growing phenomenon and develop policy in a way that improves health and safety for sex workers. This author, a cisgender woman, was moved and shocked by the sheer fragility of consent, which emerged first in a policy working group interview, and by the vulnerability of male participants as they described their chemsex experiences. The information left her, and some of the other members of the policy committee, stunned for a while by what they had heard. Both authors’ preconceptions were challenged by the findings as to the nature of chemsex interactions in a variety of ways. Firstly, the impact of the drugs on otherwise stable lives long after the party had ended. Secondly, both authors were affected by the matter-of-fact way that overdosing was spoken about and, third, neither had truly comprehended, prior to the research, the sheer uninhibited thrill of the loss of control that participants gained from chemsex.

3. Results

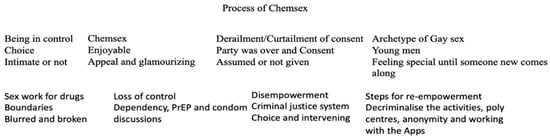

The analysis revealed a stepwise process in chemsex participation and exploitation that we have conceptualised as ‘the consent ladder’. We uncovered a categorical progression through chemsex use from being in control to disempowerment—and sometimes back to control again. This had the stepwise process of ‘being in control’, ‘chemsex’, ‘derailment’, ‘levels of consent’, ‘sex work for drugs’, ‘loss of control’, ‘disempowerment’, and then ‘steps to re-empowerment’. The analysis, shown in Figure 1, illustrated the attraction of getting into chemsex in the first place, and revealed how intricate the nature of consent is in a chemsex context. It also showed the ways in which individuals who lose control can be dis-empowered. Steps re-empowerment were possible, but also involved working with the tech companies that make the smartphone apps, peer-to-peer support, and poly-centres to help support the issues that arise when individuals lose control during chemsex practices.

Figure 1.

The Chemsex Consent Ladder—A Stepwise Process.

3.1. Being in Control

Participants highlighted that the majority of them were in control of their drugs use and enjoyed the benefits of it, as voiced in ‘the vast majority…go to parties and enjoy the sex’ (James) when talking about the general chemsex using population they knew. In addition, there was evidence that escorts have control in the services they provide as they reported that ‘some escorts are happy for sort of a straightforward hour’ without drugs, and they could choose to take the drugs depending on ‘how intimate’ they wanted to be with the clients (Mark). These reports evidenced all the elements of control and choice. This was related to the next step in the process and focuses on the positives in taking part and the allure of chemsex.

3.2. Allure of Chemsex

Clinical health providers commented that they could see the ‘appeal of crazy wild sex’ because ‘G…is an aphrodisiac; in small doses it is euphoric’ (Sarah). It highlights that there is something so appealing about the chemsex drugs and the parties; even as a health professional, she could see the attraction. This was mirrored in the other interviews: ‘Slamming…gives you quite an amazing feeling’ said Bryan, and the accounts gave insight into the reasons why people get into chemsex in the first place and the factors that keep them going back for more. The drugs were conceptualized differently to other narcotics: ‘G and T are seen as party drugs, whereas crack and heroine are seen as addictions’ (Casey). The participants reported a ‘glamourizing’ of the drugs in the name change from injecting to ‘slamming’ and ‘if you call it something…more glamourized, then that’s fine’ (Peter). In line with Goffman’s theory of stigma, the glamourizing of the drugs could be a possible reaction to the stigma and divergence from what were referred to as ‘old school…drug users’ by the participants.

3.3. Stepwise Ladder of Consent

The rungs of consent varied, and the derailment that could occur in chemsex was reported by all the participants: ‘for a minority of people that engage in it, it becomes problematic really, really quickly’ (James). This was seen as a small minority, and not everyone who does it has a problem and some people can manage it, but participants referred to the ‘come-down’ or ‘weepy Wednesday when the party was over’ (Andrew). This was conceptualised as falling off a ladder and marked the sobering up point and coming down from the drugs after a two or three day party. People would realise at this stage that things had not gone to plan and had then accessed health and/or help services. This would be the point when the men would start to lose their control regarding issues of consent, and if any crimes came about they were then reported. As one of the health workers stated:

‘I worked with one man who was struggling with his sexual identity, and he’d go to sex parties. He has been addicted to various different substances, and this particular bout of addiction was crystal meth and GHB, em, and he found it really difficult not to go on a bender and spend all of his money initially. He would go to sex parties and basically sell sex to get his next fix, but then he would go kind of a step further and he would maybe be unconscious and then not know what was happening to him, and he then went over on G, and I can’t remember how many times he ended up in intensive care. There are issues related to the drugs, there are issues related to consent, and there are issues related to just kind of the danger of blood born viruses. And then the selling sex for the drugs, and that sort of not intentional, maybe seen as sex work, but actually…’.(Freya)

Another participant described their own loss of control thus: ‘having this intimate experience is difficult so drugs help and yet there are other consequences of taking drugs, with what reactions to them and the dangers involved in taking them, to which I have been unconscious on a number of occasions and I am still alive as of today. But I am aware that there could have been any of those occasions where the combination of drugs I took might have, eh, you know, have seriously harmed me, or even possibly death’ (Sven).

The rungs of consent in commercial encounters were typified thus: ‘My experience is varied and there are escorts who are happy for a sort of straight forward hour of session, then you go away and that’s it. Others I’ve used crystal meth with or, you know, G, and it is deliberately there to enhance the sex possibly for longer; they also get paid longer, it varied, you know, if the sex goes on for two, three, four hours, and that is part of the fantasy with using drugs; we know that they do elongate the time that we play and you have more fun and I can’t lie over 20 years’ worth of experiences as I’m 40 next week. You know I have had a lot of good fun, but I have also seen a lot of harm and reactions to it, and male sex workers are obviously in that critical play position whereby do they decide not to and not have that as part of their deal of who they are meeting, or do they?’ (Andrew).

The participants also discussed the issue of consent when under the influence, when it is assumed, and when it has not been given. The participants reported what they called ‘steps’ or ‘nuances’ in gaining consent while people are under the influence of ‘methamphetamine that automatically makes their judgement clouded’ (Ged). This idea of clouded judgement was mirrored in the other interviews and was a possible explanation for the times that consent might have been assumed and the outcome of that being an innocent mistake when both parties have taken drugs: ‘someone who innocently…makes a mistake you may take as being deliberate’ (Mark). This was a possible explanation for those circumstances, though participants also talked about people who ‘deliberately’ cross those boundaries and the intentional overdosing of a person hung in the air ambiguously in the interviews.

There was also found to be a level of consent by the sex workers’ decisions to take part in chemsex or not, ‘it depends on how intimate the escort wants to be’ (Hal). This gave the impression that the workers had a choice and they also got benefits of more money when taking ‘chems’ while providing their services. Though, on the other side, consent was taken away when drugs were involved. In such cases they: ‘did things that they wouldn’t normally, which were beyond their boundaries’ (Peter). The boundaries and levels of consent were difficult to assess and maintain when drugs were involved. Participants reported the ‘nuances’ in these thin lines, and rungs that could be easily crossed or slipped off in these situations, and how sometimes they could be innocent mistakes and other times there could be a darker aspect to it. One participant noted:

‘If you are offering some sort of service and you now say this is the service and this is what I am willing to do, this is what’s on offer and, you know, take it or leave it. Hopefully, like a lot of jobs, there is room for discussion, a bit of leeway, but the problem is if you start taking drugs while you are working then you are sort of effectively handing over, you are potentially handing over your part of the bargaining to the client because the client is probably going to benefit from the situation more than yourself. Guys who were offered free drugs when they took a job then actually didn’t get paid and did things that they wouldn’t normally do, which were beyond their boundaries’.(Uvi)

Of the nuances of drug use and the need for support, another participant said of injecting drugs:

‘it’s a very intimate thing for two guys to get involved in slamming together; it’s actually breaking the skin and sticking something in someone’s skin. I think it’s more in line with self-harm than drug use, when you look at how people do it. There is more of an aggressive violent, eh, aspect to it as well, uhm. It’s quite worrying that, for some of the guys, their first exposure to drugs has been slamming them at a chemsex party and I think about people who have had a first exposure to drugs as an injecting drug user that it is a completely different ballgame because maybe they are not learning, you know, the subtleties, er, nuances around learning how to take drugs safely …it’s almost like walking in a bar and just going straight to the optics and drinking 6 or 7 whiskeys and not really learning about drinking a shandy or a beer and learning how to handle that. I think that in injecting communities, I am an ex-injecting drug user myself, there is an elder in that community who teaches people how to safely inject, and these used to be the go-to people, so, you know, people would sit down with them and teach them how to inject, what veins to use. Now, I just don’t think that that’s there in chemsex’.(Hal)

3.4. Archetype of Gay Sex

All of the participants discussed young men who come into the scene and see chemsex as an archetype of gay sex: ‘younger people who don’t know what to do but will do anything’ (Tim). This, however, was seen as a result of a lack of discussion around chemsex and gay sex in general which was reported by the participants, as in one who stated ‘seeing that the only way to be stimulated is to take drugs’ (Uvi). A commonly reported aspect of chemsex was the concept of chasing this stimulation, Andrew explains ‘you are young, and cute people will think that’s great and go after you’ (Andrew). Here, he discusses the people who get ‘procured’ into the chemsex lifestyle as a result of people making you ‘feel special’. There was clearly a predatory aspect to the way men are pursued and that ‘they go after you’ suggests a preying on the younger guys and making them feel special. Participants also talked about a period of time when ‘you are the one everyone wants until someone new comes along’ (Sven), indicating the competition that exists.

3.5. Sex Work for Drugs

As the process continues, it moves on to ‘derailment’ as the interviewees reported that people may get into sex work to pay for the drugs to which they had become addicted. Freya reported: ‘they do things they wouldn’t normally do, like have sex on drugs or have sex to get the money to get the drugs’. Participants also reported the issues that arise when sex working and being offered free drugs: ‘they took a job, then actually didn’t get paid’ (Raj). This offering of drugs in lieu of payment links to the loss of control because the drugs have given the bargaining to the client, and afterwards they could have assumed that they had paid them already. This links to the loss of control because the worker is assuming that they will get the pay and the ‘free drugs’ but they lose their bargaining power when they take the drugs, leading to further loss of control.

3.6. Loss of Control

This subcategory had two elements to it: loss of control in the general chemsex community and loss of control for the workers when they provide chemsex as a service. In the general chemsex community, there is loss of control in their drug taking practices. Sarah observes that: ‘quite quickly, it becomes psychologically dependent’. The loss of control applies to that turning point, from it all being fun and in control to it becoming an addiction to the drugs or lifestyle. Peter states: ‘negotiations around PrEP were difficult to manage if you have got a really hazy head’. There was also a loss of control over protective measures for HIV and other STIs when drugs were involved. Disinhibited by the drugs and the conversations and intentions about it, safe sex get forgotten about.

A commonly used term by the participants was ‘Going over on G’ and reflected the ease of overdosing on GHB/GBL. Freya related the experience of one man who had sex worked for drugs, and images and videos of him appeared on social media and pay-per-view sights, and someone else was getting the money for it while he received only the drugs: ‘sex that time for drugs, but then that was then sold so the sex work continued but he wasn’t even getting cash’—a wholly exploitative situation. Another participant said, ‘it feels like you are in control…then that actually gets turned around’ (Casy). In talking about the control that sex workers assumed they had because they were the ones selling the sex, the difficulty is that control is lost as a result of the drugs. This loss of control for sex workers was an important aspect because those who had done sex work reported: ‘we like to be in control of what we do’ (Uvi). This lack or loss of control could also be harmful to the workers mental wellbeing. Participants commented on the ‘saturation’ of the sex work field, which could possibly be the reason the workers were providing this as a service without the choice. They also commented on the control over what acts workers are willing to perform when drugs are involved; workers were more likely to do what they thought the client wanted rather than what they were willing to provide: ‘substances being involved you are…much more likely to maybe do what you think the person wants you to do’ (Bryan). The workers would then cross the boundaries that they would not usually cross because of possible peer pressure and the influence of the drugs. In this way they would fall down the rungs of the ladder of consent and into disempowerment.

3.7. Structural Disempowerment

Participants reported that the criminal justice system took away the power from the individuals when a crime was committed against them. They also reported a concern from sex workers in reporting crimes when drugs were involved, and one encapsulated it as: ‘they legislate everything out of sight, it’s just not working’ (James). Chemsex participants were worried about possibly being prosecuted for the drugs, and the assault might be overlooked owing to a drug classification, for example, ‘if it’s a class A drug and a group that is sometimes harder to overlook’. This disempowers the individuals as they cannot report the crimes that have been committed around issues of consent, and this applied to both non-commercial and commercial sexual activity.

A lack of education around consent seemed to be another factor of disempowerment. This lack of understanding of what consent is could be harmful to the individual mentally, and one participant said, ‘I certainly didn’t seem to realise that if you can’t consent then it is sexual violence’ (Ged). There was also a level of struggling to intervene when seeing someone not enjoying themselves that another reported: ‘having the guts to intervene and say…he is not looking well there, I think you should stop’ (Mark). This is a barrier, even for someone who knew about consent but still did not feel able to intervene because of the powerful force of compliance inhibited bystander action. Another participant reported lying over a young male sex worker’s body and pretending to be asleep so that older predatory men could not have sex with the young man until he had recovered enough to know what was happening.

3.8. Stepwise Re-Empowerment

One step to re-empowerment that permeated the interviews was the decriminalisation of the drugs. Participants reported that this would reduce the stigma around the drug taking in the wider society. Decriminalisation, it was argued, could also help bring back the power lost when a sexual assault has been committed because the worry of being prosecuted for the drugs used would be taken away. There was also a suggestion to de-criminalise sex work in the majority of interviews. This again was understood to possibly reduce the stigma surrounding sex workers. Freya said: ‘decriminalise activities like this, including substance use, and look at them as a health issue or a societal issue’. This move from the criminal justice system to health or societal issue was one that was mirrored in other interviews, and treating it like alcohol addiction was reported by other participants. This change from the criminal justice system to a health matter was one in which the participants reported, because they understood that it would be easier to manage people’s drug use if they treated it in the same way as people who had alcohol problems.

Education around consent and drug use was another step considered to help re-empower the individuals whose lives had been ‘taken over by sex work’. Education was also considered to help to open up a discussion around chemsex and accordingly reduce the stigma around it. Participants suggested that education around same sex partners and consent should be taught at schools, which could then reduce stigma: ‘consent is a major issue…it needs to be taught as education’ (Ged).

Taking time out from chemsex was a further way of taking back control, and participants talked about people they knew who would: ‘take every like third week or weekend off’ (Raj). This links back to the concept of control, that people have taken the time off to recover from the drugs. Many clinicians advised sex workers to do the same and take back the control, as the comedown from the drugs is usually a few days and this would eat into time that the workers could be seeing other clients and getting more money. The perceived saturation of the male sex work market, however, could be a barrier to doing this.

While digital technology and smartphone apps play an integral role in both the sex work and drug taking they were a barrier to support, and participants reported the possible ways in which apps could be applied to support and help instead. This was considered attainable because it was considered that: ‘the LGBT community are kind of the first…adopters’ (Sven). Participants suggested that this might be the progression of communication for the wider population too, with ideas around the placement of adverts on these apps to signpost other apps, which are there to help and provide support around the issues that chemsex brings, and when individuals have lost control. Helpful adverts were reported in most of the interviews, and a further suggestion was made of a space where people could ‘talk about things that went wrong or report users’ (Uvi). This could return power back to those individuals and links to the idea of peer-to-peer support that the other participants reported would also help by promoting success stories from people: ‘I also felt trapped, but I’m no longer trapped’ (Raj). They would also be able to ‘talk the language’ and not have someone who is not part of it telling you what to do. This links to the notion of the community having the skills within itself; one participant said: ‘teach him how to fish and he will feed himself for a lifetime’ (Tim), suggesting a role for education here also.

Further suggestions that emerged were a poly-centre where all clinical and practical help is in one place and people do not have to struggle with managing their time around the various appointments, as participants said that clients ‘feel that they can’t really structure their week to accommodate all of them’ (Sarah). The poly-centre could accommodate all the support needs that an individual has because of the issues from chemsex and could make the appointments manageable and anonymous. Such centres were considered to be able to tackle the stigma related to going to other mainstream services and deal with concerns that chemsex adherents had around using the drugs and being prosecuted.

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to explore the issues that arise at the interaction between chemsex and commercial sexual activity. The analysis of the interviews revealed that the stepwise process of chemsex begins as a pleasurable, so pleasurable that even health care professionals could see the appeal, and controllable activity. But, for a minority of participants, things could de-rail and become uncontrollable, disempowering, and exploitative. Willing participation in sex work could culminate in pressure to take and/or supply drugs and negate consent in other areas, and it could also escalate. It was therefore conceptualised in a ladder of consent in which participants could go up or down, and the conditions under which willing participation could turn to exploitation were clarified. The participants, informed by their health practice work or experience having taken part in chemsex, suggested ways to re-empower those individuals who lose control.

The glamourizing of certain drugs to differentiate them from other addictive drugs also took place; indeed, it is not unusual for a stigmatised group to change the name of an activity they are engaged in so that it is more socially acceptable. This supports classic theory on stigma (Goffman 1963) and reinforces previous findings on chemsex (Giorgetti et al. 2017). In this case, a change of terminology from injecting to ‘slamming’ drugs was adopted to make it more socially acceptable. Changing the name, however, was also a barrier to accessing support because people who use chemsex do not see themselves as being the same as injecting drug users per se and would not access the services that are available.

A major strength of the study was that the participants were able to provide frank answers to the dangers that may occur in these instances, and they did not hold back for fear of being stigmatised or prosecuted. They were able to highlight the issues and could give examples, either from their own experience or from those of the people they had supported, to enable re-empowerment. Limitations do however remain, and these include the size of the sample and its focus on cisgender male sex, as our participants did not contain nor refer to transgender men—it is therefore transferability that should be attempted from such findings rather than extensive generalizability. In the conceptualisation of a consent ladder, the study advances the theory of concept of consent to illustrate the nuances in the stepwise process from willing participation to loss of control. In this way, the study augments the work of Smith and Tasker (2018) on survival stories and advances the work on motivations and values by Flores-Aranda et al. (2019) and Weatherburn et al. (2017).

4.1. Implications for Service Development

This analysis helps expand the body of evidence for calls by Sewell et al. (2019) and Evers et al. (2020) for targeted service intervention for those at highest risk, along with gay population education so that young men arriving on the scene do not see it as archetypal gay sex.

Although the results do not contain any evidence of Stevens et al.’s (2019) findings of suicide ideation, there are some serious cases and there is specific support for their findings that services are not meeting needs. Our analysis suggest an importance for specialised services tailored to these specific drugs and the specific issues arising from taking part in chemsex. The fact that, in the UK, harm reduction is focused on more traditional addictions such as heroin or crack cocaine supports the findings of McCall et al. (2015). However, participants reported that these services are old-fashioned in the attitudes and services that they provide, still believing that, on the whole, injecting is still injecting. Therefore, maybe more specialised services along the lines of a one-stop-shop that maintain anonymity might be the solution, and the perceptions of pleasure and the process may help services to develop their practice.

Peer-to-peer support was reported to be a very valuable practice, as it was a move away from professionals telling them what to do to having someone who had experienced what they are talking about, which was an important and effective aspect for the individuals concerned. The analysis revealed that a possible barrier could be the NHS services not having that experiential knowledge, and a move towards more services providing complete anonymity would be an improvement, which most of the participants felt would be useful to reduce stigma.

The role of poly-centres where participants would be able to see doctors, dentists, and counsellors in one place was also raised, as this could help with time-management, with all the appointments that the individual might need after using chemsex over the weekend being available. Anonymity in these services is vital to ensure that people feel comfortable accessing them, as the fear of being prosecuted because of the barrier of the illegality of the drugs and paid sexual labour would be removed for most of the participants. These might help to overcome the issues raised by McCall et al. (2015), and these could help to update services so as to address the changing nature of chemsex use.

4.2. Implications for Education

Digital tools and smartphone apps play an important role because they are where people recruit others for parties, find clients, and also find the drugs (Stuart 2019). The findings suggest that, as the preferred communication for the MSM who take part in chemsex, smartphone platforms could be developed to help and offer support when needed and might be the next step in communication and service delivery (c.v Platteau et al. 2020). At present, the apps present a hinderance rather than a help, where they could be developed to provide support and also be used to signpost services digitally (or in person) to help support those people who are disempowered. Furthermore, educating people around consent and drugs would help people to feel empowered enough to intervene when someone is not enjoying it or has not consented and something untoward happens. Therefore, bystander education would be valuable, as would education on particular chemsex drugs to help inform men better of the risks, which may reduce the number of men slamming dangerously.

4.3. Future Research and Policy

The overdosing of individuals was both shocking and redolent of known cases that have appeared in the media. While past research has found that it is possible to make mistakes in the doses of GHB/GBL (Bourne et al. 2014, 2015), the findings support the idea that there is a group of people for whom this is a common occurrence. Future research needs to explore this in more detail. Furthermore, the motives for this, along with sexual gratification, thrill-seeking, and any malevolent behaviour all require further investigation. This study extends the findings of Tan et al. (2018) on destigmatizing and decriminalising, and augments their recommendations that if drugs were to be decriminalised, there might be a reduction of stigma around their use, and these men would be able to access more mainstream services, and if paid sex were decriminalized it would remove the multiple stigmas. The decriminalisation of sex work could certainly empower people to report crimes committed against them. Additionally, the shift from treating these activities from a criminal perspective to a health and societal perspective was reported as being a useful thing to do. These findings have implications for service recommendations and strategies to address the issues of those individuals taking part in chemsex who lose control in order to bridge the gaps and limitations of current services, which are not specialised and up-to-date enough. The findings from the first phase have already had an impact in a UK context on the public policy of a major political party (qv. Brooks-Gordon et al. 2017) and, with the addition of the subsequent findings from phase two, this study has contributed to progressive harm reduction policies by law enforcement bodies (qv. Sanders et al. 2020). The study strengthens the case for decriminalisation of both sex work and the drugs, which in turn could reduce the stigma, as regulating the drugs could help people better manage the issues around overdosing on GHB/GBL. Without consensus for government protection and occupational and social rights to extend to sex workers, the laws and regulations that allow exploitation to exist will persist.

5. Conclusions

Participants reported that there are positive elements to chemsex activities, when they are controlled and managed well, and not all people who take part in these activities struggle with their drug use. The purpose of the research was to highlight any possible issues surrounding these activities in order to clarify conditions of exploitation and willing participation. The consent ladder is therefore a significant theoretical development to the literature on chemsex and sex work, as well as a valuable tool for education, safety, and re-empowerment.

Author Contributions

B.B.-G. suggested the topic, supervised the data collection, and collected the data in phase one of the study. E.E. carried out the interviews in phase two of the project and did the first analysis of the phase two data. B.B.-G. amalgamated the data, and wrote the first draft of the paper. Both authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The Liberal Democrat Party provided administration support for the first phase of the study which was initial participant contact and room bookings for interviews.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was subject to ethical review and ethical approval was granted by the Ethics Committee in the School of Psychology at Birkbeck, University of London. The ethical guidelines of both the British Sociological Society and the British Psychological Society were closely adhered to, and participants had the right to withdraw their data at any time throughout the study.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was given via email before the interviews and also written and signed by both the researchers and participants when they met. Participants were informed about all aspects of the project and debriefed after the interviews.

Data Availability Statement

Raw data sets are subject to GDPR and not on the public domain.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- ACMD. 2020. Letter from Prof Owen Bowden-Jones to Home Secretary the Rt. Hon. Priti Patel MP on GHB/GBL and Related Compounds. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/867589/Letter_from_the_ACMD_to_the_Home_Secretary_-_GHB__GBL__and_related_compounds.pdf (accessed on 4 November 2020).

- Adfam. 2019. Chemsex More than Just Sex and Drugs. Information and Advice for Families, Partners and Friends. Available online: https://adfam.org.uk/our-work/supporting-families/chemsex (accessed on 4 November 2020).

- Ahmed, Alysha-Karima, Peter Weatherburn, David Reid, Ford Hickson, Sergio Torres-Rueda, Paul Steinberg, and Adam Bourne. 2016. Social norms related to combining drugs and sex (“chemsex”) among gay men in South London. International Journal of Drug Policy 38: 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, Ingrid, and Leon Knoops. 2018. Towards a continuum of care concerning Chemsex issues. Sex Health 15: 173–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourne, Adam, David Reid, Ford Hickson, Sergio Torres Rueda, and Peter Weatherburn. 2014. The Chemsex Study: Drug Use in Sexual Settings among Gay and Bisexual Men in Lambeth, Southwark and Lewisham. Technical Report. London: Sigma Research, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. [Google Scholar]

- Bourne, Adam, David Reid, Ford Hickson, Sergio Torres-Rueda, and Peter Weatherburn. 2015. Illicit drug use in sexual settings (‘chemsex’) and HIV/STI transmission risk behaviour among gay men in South London: Findings from a qualitative study. Sexually Transmitted Infections 91: 564–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks-Gordon, Belinda, Brian Paddick, Hannah Bettsworth, Sarah Brown, Charlotte Cane, Flo Clucas, Christopher Cooke, Simon Cordon, Sandra Hobson, Catrin Ingham, and et al. 2017. A Rational Approach to Harm Reduction. Policy Paper 126. Spring Conference. Liberal Democrats, United Kingdom. Available online: https://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/libdems/pages/13634/attachments/original/1487768795/SW_Policy_Paper_(Online).pdf?1487768795 (accessed on 2 November 2020).

- Chettiar, Jill, Kate Shannon, Evan Wood, Ruth Zhang, and Thomas Kerr. 2010. Survival sex work involvement among street-involved youth who use drugs in a Canadian setting. Journal of Public Health 32: 322–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crown Prosecution Service. 2020. CPS Website 6 January 2020. Available online: https://www.cps.gov.uk/north-west/news/britains-most-prolific-rapist-jailed-life-following-historic-prosecution (accessed on 29 October 2020).

- Davies, Caroline. 2016. Stephen Port’s Freedom to Kill Raises Difficult Questions for the Met. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2016/nov/23/stephen-ports-freedom-kill-difficult-questions-met-police (accessed on 23 November 2019).

- Deimel, Daniel, Heino Stover, Susann Hobelbarth, Anna Dichtl, Niels Graf, and Viola Gebhardt. 2016. Drug use and health behaviour among German men who have sex with men: Results of a qualitative, multi-centre study. Harm Reduction Journal 13: 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evers, Ymke J., Christian J. P. A. Hoebe, Nicole H. T. M. Dukers-Muijrers, Carolina J. G. Kampman, Sophie Kuizenga-Wessel, Decontee Shilue, N. C. M. Bakker, Sophie M. A. A. Schamp, W. C. J. P. M. Van Der Meijden, and Genevieve A. F. S. Van Liere. 2020. Sexual addiction and mental health care needs for men who have sex with men practicing Chemsex—A cross sectional study in The Netherlands. Preventative Medicine Reports 18: 101074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Aranda, Jorge, Goyette Mathieu, Valérie Aubut, Maxime Blanchette, and Frédérick Pronovost. 2019. Let’s talk about chemsex and pleasure: The missing link in Chemsex services. Drugs and Alcohol Today 19: 189–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galicia, Miguel, Santiago Nogue, and Òscar Miró. 2011. Liquid ecstasy intoxication: Clinical features of 505 consecutive emergency department patients. Emergency Medicine Journal 28: 462–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgetti, Raffaele, Tagliabracci Adriano, Schifano Fabrizio, Zaami Simona, Marinelli Enrico, and Busardo Francesco Paolo. 2017. When ‘Chems’ Meet Sex: A Rising Phenomenon Called “Chemsex”. Current Neuropharmacology 15: 762–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, Barney, and Anselm Strauss. 1967. The Discovery of Grounded Theory. Strategies for Qualitative Research. Mill Valley: Sociology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Graf, Niels, Anna Dichtle, Daniel Deimel, Dirk Sander, and Heino Stover. 2018. Chexsex among men who have sex with men in Germany: Motives, consequences and the response of the support system. Sex Health 15: 151–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffman, Erving. 1963. Stigma: Notes on the Management of a Spoiled Identity. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Hibbert, Matthew P., Caroline E. Brett, Lorna A. Porcellato, and Vivian D. Hope. 2019. Psychosocial and sexual characteristics associated with sexualised drug use and Chemsex among men who have sex with men (MSM) in the UK. Sexually Transmitted Infections 95: 342–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, Tristan. 2020. Evening Standard 3 Nov. Available online: https://www.standard.co.uk/news/crime/former-bbc-radio-producer-crystal-meth-alexander-parkin-b40460.html (accessed on 4 November 2020).

- Kohli, Manik, Ford Hickson, Caroline Free, David Reid, and Peter Weatherburn. 2019. Cross-sectional analysis of chemsex drug use and gonorrhoea diagnosis among men-who-have-sex-with-men in the UK. Sexual Health 16: 464–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawn, Will, Alexandra Aldridge, Richard Xia, and Adam R. Winstock. 2019. Substance-Linked Sex in Heterosexual and Bisexual Men and Women: An Online, Cross-Sectional ‘Global Drug Survey’ Report. The Journal of Sexual Medicine 16: 721–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Richard, and Sean Perrera. 2016. Safer ‘chemsex’: GPs’ role in harm reduction for emerging forms of recreational drug use. British Journal of Gern Practice m66: 4–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacPhail, Catherine, John Scott, and Victor Minichiello. 2015. Technology, normalisation and male sex work. Culture, Health & Sexuality 17: 483–95. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell, Steven, Maryam Shamanesh, and Mitzy Gafos. 2019. Chemsex behaviours among men who have sex with men: A systematic review of the literature. International Journal of Drug Policy 63: 74–89. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0955395918302986 (accessed on 4 November 2020). [CrossRef]

- McCall, Hannah, Naomi Adams, David Mason, and Jamie Willis. 2015. What is chemsex and why does it matter? BMJ 351: h5790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, Aandrew. 2015. ‘You can do it from your sofa’: The increasing popularity of the internet as a working site among male sex workers in Melbourne. Journal of Sociology 51: 887–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misuse of Drugs Act 1971. 2019. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1971/38/contents (accessed on 4 November 2020).

- Morris, Max. 2018. Incidental Sex Work: Casual and Commercial Encounters in Queer Digital Spaces. Doctoral dissertation, Durham University, Durham, UK. Available online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/13098/ (accessed on 4 November 2020).

- Okafor, Chukwuemeka N., Christopher Hucks-Ortiz, Lisa B. Hightow-Weidman, Manya Magnus, Lynda Emel, Geetha Beauchamp, Irene Kuo, Craig Hendrix, Kenneth H. Mayer, and Steven J. Shoptaw. 2020. Brief Report: Associations between Self-Reported Substance Use Behaviours and PrEP Acceptance and Adherence among Black MSM in the HPTN073 Study. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 85: 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveto, Alison, W. Brooks Gentry, Rhonda Pruzinsky, Kishorchandra Gonsai, Thomas R. Kosten, Bridget Martell, and James Poling. 2010. Behavioral Effects Of Gamma-Hydroxybutyrate (GHB) In Humans. Behavioural Pharmacology 21: 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakianathan, Mark R., Ming J. Lee, Bernard Kelly, and Aseel Hegazi. 2016. How to assess gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men for chemsex. Sexually Transmitted Infections 92: 568–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parry, Sarah, H. Curtis, David Chadwick, and British HIV Association (BHIVA) Standards Sub-Committee. 2017. Psychological Wellbeing and Use of Alcohol and Recreational Drugs: Results of the British HIV Association (BHIVA) National Audit 2017. London: British HIV Association. [Google Scholar]

- Perkins, Roberta, and Garry Bennett. 1985. Being a Prostitute: Prostitute Women and Prostitute Men. Sydney: George Allen and Unwin. [Google Scholar]

- Pirani, Filippo, Alfredo F. Lo Faro, and Anastasio Tini. 2019. Is the issue of Chemsex changing? La Clinica Terapeutica 170: e337–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Platteau, Tom, Corinne Herrijgers, and John de Wit. 2020. Digital Chemsex support and care: The potential of just-in-time adaptive interventions. International Journal of Drug Policy 85: 102927. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0955395920302668 (accessed on 4 November 2020). [CrossRef]

- Sanders, Teela, Dan Vajzovic, Belinda Brooks-Gordon, and Natasha Mulvihill. 2020. Policing Vulnerability in Sex Work and Prostitution: The Harm Reduction Compass Model. Journal of Policing and Society. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilder, Arn J., Thomas M. Lampinen, Mary L. Miller, and Robert S. Hogg. 2005. Crystal methamphetamine and ecstasy differ in relation to unsafe sex among young gay men. Canadian Journal of Public Health 96: 340–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sewell, Janey, Valentina Cambiano, Andrew Speakman, Fiona C. Lampe, Andrew Phillips, David Stuart, Richard Gilson, David Asboe, Nneka Nwokolo, Amanda Clarke, and et al. 2019. Changes in chemsex and sexual behaviour over time, among a cohort of MSM in London and Brighton: Findings from the AURAH2 study. International Journal of Drug Policy 68: 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Vivienne, and Fiona Tasker. 2018. Gay Men’s Chemsex Survival Stories. Sex Health 15: 116–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinelli, Matthew A., Nicole Laborde, Patrick Kinley, Ryan Whiteacre, Hyman M. Scott, Nicole Walker, Albert Y. Liu, Monica Gandhi, and Susan P. Buchbinder. 2020. Missed opportunities to prevent HIV infections among pre-exposure prohylaxis users; a population-based mixed methods study, San Francisco, United States. Journal of International AIDS Society 23: e25472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, Oliver, Monty Moncrieff, and Mitzy Gafos. 2019. Chemsex-related drug use and its associated with health outcomes in men who have sex with men: A cross-sectional analysis of Antidote clinic service data. Sexually Transmitted Infections 96: 124–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, David. 2019. Chemsex: Origins of the word, a history of the phenomenon and a respect to the culture. Drugs and Alcohol Today 19: 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Rayner K. J., Christina M. Wong, Mark I. Chen, Yin Y. Chan, Muhamad A. Bin Ibrahim, Oliber Z. Lim, Martin T. Chio, Chen S. Wong, Roy K. W. Chan, Lynette J. Chura, and et al. 2018. Chemsex among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men in Singapore and the challenges ahead: A qualitative study. International Journal Drug Policy 61: 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hout, Marie C., Des Crowley, Siobhan O’Dea, and Susan Clarke. 2019. Chasing the rainbow; pleasure, sex-based sociality and consumerism in navigating and exiting the Irish Chemsex scene. Culture Health Sexuality 21: 1074–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Zixin, Xue Yang, Phoenix K. H. Mo, Yuan Fang, Tsun K. M. Ip, and Joseph T. F. Lau. 2020. Influence of social media on sexualized drug use and Chemsex among Chinese men who have sex with men: Observational prospective cohort study. Journal of Medical Internet Research 22: e17894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weatherburn, Peter, Ford Hickson, David Reid, Sergio Torres-Rueda, and Adam Bourne. 2017. Motivations and values associated with combining sex and illicit drugs (‘chemsex’) among gay men in South London: Findings from a qualitative study. Sexually Transmitted Infections 93: 203–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winstock, Adam. 2015. New health promotion for chemsex and γ-hydroxybutyrate (GHB). BMJ 351: h6281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 1 | Street names for mephedrone include Meow Meow, MCAT, or plant food. |

| 2 | Street names for crystal methamphetamine are crystal, meth, ice, tina, or T. |

| 3 | Street names for GHB/GBL are G, Gina, or liquid ectstasy. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).