Abstract

Modern historiography has studied the influence of messianic and millennialist ideas in the Crown of Aragon extensively and, more particularly, how they were linked to the Aragonese monarchy. To date, research in the field of art history has mainly considered royal iconography from a different point of view: through coronation, historical or dynastic images. This article will explore the connections, if any, between millennialist prophetic visions and royal iconography in the Crown of Aragon using both texts and the figurative arts, bearing in mind that sermons, books and images shared a common space in late medieval audiovisual culture, where royal epiphanies took place. The point of departure will be the hypothesis that some royal images and apparently conventional religious images are compatible with readings based on sources of prophetic and apocalyptic thought, which help us to understand the intentions and values behind unique figurative and performative epiphanies of the dynasty that ruled the Crown of Aragon between 1250 and 1516. With this purpose in mind, images will be analysed in their specific context, which is often possible to reconstruct thanks to the abundance and diversity of the written sources available on the subject, with a view to identifying their promoters’ intentions, the function they fulfilled and the reception of these images in the visual culture of this time and place.

1. Introduction

On 21 March 1522, in Xàtiva, the second largest city of the kingdom of Valencia, a man dressed as a sailor climbed up on a catafalque, sword in hand, flanked by two other men playing trumpets. Surrounded by four harquebusiers and hundreds of soldiers, he made a speech as solemn as a sermon in which he declared himself the legitimate heir to the Trastámara dynasty and a challenger to the throne of Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor. He also acted as a spokesman for doctrines later deemed heretical by the Inquisition: he announced the imminent end of the world, revealed to him by Elijah and Enoch, declared victory against the Antichrist and stated that the ‘Quaternity’ included the Father, the Son, the Holy Spirit and the Sacrament, before asking for the goods collected at Xàtiva Collegiate church to be used in the war and to help the poor (Pérez García and Catalá 2000, pp. 140–74; Nalle 2002; Duran [1983] 2004, pp. 283–318).

The reconstruction of this figure and his speech is based on witness declarations at the Spanish Inquisition tribunal and on chroniclers who were generally against the Revolt of the Germanias, which shook the kingdom of Valencia between 1519 and 1522 with civil war-style battles between supporters of the crown and the viceroy on one side and the rebels on the other (García Cárcel 1981; Duran 1982; Vallés 2000; Pérez García 2017). In contrast, here, I aim to situate the Hidden King, or El Encubierto, and the ideas he echoed within a prophetic, millennialist tradition applied to the Crown of Aragon from the thirteenth century onwards. This approach will shed light on how such an eccentric figure, of obscure origins and enveloped in a supernatural aura, embodied by various individuals, was able to revitalise the dying Revolt of the Germanias and was hunted until the mid-sixteenth century by the courts and viceroys of Valencia, who saw these ‘hidden’ characters as a threat to royal power, due to their express desire to supplant it. In particular, it is relevant to examine how the Hidden King’s epiphany of 1522 was staged through narrations and ideas that had been circulating for centuries, both in the Court and as part of popular belief in the Crown of Aragon. To do so, images and texts will be used to explain the figure’s appearance and suggestion, as well as the subversive fallout of the episode that led to subsequent repression, still seen as late as 1541 (Bercé 1990, pp. 317–23; Pérez García and Catalá 2000).

Under the Crown of Aragon grew an eschatological vision that combined the contribution of Joachim of Fiore and of the Franciscan radicalism of the Beguines and the Fraticelli with the Ghibelline imperial legacy of the Staufen and Hispanic neo-Gothic prophetism, which longed for the full restoration of Christian dominion on the Iberian Peninsula over Islam (Pou [1930] 1996; Milhou 1983; Aurell 1992; Reeves [1969] 1993; Rousseau-Jacob 2015). Although there has been a broad and detailed analysis of the dissemination and reworking of an eschatological philosophy that foresaw a sacred mission for the monarchs of the Crown of Aragon thanks to various European and Hispanic traditions that spoke of an Emperor of the Last Days, a Hidden King or a New David called upon to defeat the Antichrist and establish the millennium before the Final Judgement (Milhou 1982; Aurell 1997; Duran 2004, pp. 157–350), there has been little trace of images that represented these messianic interpretations of Aragonese royalty. This gap in historiography is particularly surprising given the attention paid to the image of royal power in this series of kingdoms and principalities united by a monarchy that was aware of the value of visual media to strengthen its authority vis-à-vis rival powers in the European and Mediterranean area and other institutions, such as the Church, Parliament (the Corts), the nobility and urban powers (García Marsilla 2000; Español 2001; Serrano 2015a). Furthermore, research into representation of the king has tended to focus on other aspects of his image through portraits and other figurative media, as well as ceremonial, coronation, funerary and majestic images, rather than on the nuanced manifestation of the monarch as a messianic subject (Hedeman 1991; Perkinson 2009; Vagnoni 2017). Aragon was not a sacral monarchy, but a singularly messianic charisma could be expected from kings whose authority relied on genealogy, conquest and the law of the land; even if no member of the House of Aragon was ever canonized, expressions of piety and millennialist prophecies contributed to establish a transcendental profile of monarchy (Jaspert 2010, pp. 183–218).

The point of departure will be the hypothesis that some royal images and apparently conventional religious iconography are compatible with readings based on sources of prophetic and millennialist thought, which help us to understand the intentions and values behind particular figurative and performative epiphanies of the dynasty that ruled the Crown of Aragon from James I (1213–1276) until Ferdinand II the Catholic (1476–1516). The use of metaphor and allegory, the commemorative function and the implicit action in eschatological visions persuaded and informed observers of events, prophecies and missions that wrapped the Aragonese kings in a uniquely charismatic aura, staged through images and ceremonies. It is even worth wondering whether or not eschatological images of the monarchy interfered in royal power’s other forms of representation in the Crown of Aragon, thus making it unique. The final part of this article will discuss the possibility that the power vacuum created in 1516 by the death of the monarch may have led to the subversion of a collection of images and ideas that, although established in theory to praise royal authority, ended up challenging Emperor Charles V and royal officials in the Valencia of the Germanias.

With these purposes in mind, I will analyse the images in their specific context, which is often possible to reconstruct thanks to the abundance and diversity of the written sources available on the subject, with a view to identifying their promoters’ intentions, the function they fulfilled and the reception of these images in the visual culture of this time and place.

2. The Messianic Prophetism of the Kings of the Crown of Aragon

Apocalyptic thought determines the meaning of human history from the creation of the world and the coming of Christ and awaits the Last Judgement following a marked, precise temporal structure and trajectory, which is revealed in the final book of the Christian Bible as the definitive battle between good and evil and may be prophesied by visionary spirits. This belief is accompanied by the feeling, which sometimes seems to become a reality, that the end of this world is imminent and foretold by signs and events that will herald a millennium of peace and happiness after the defeat of the Antichrist until the final battle with Satan and the redemptive installation of the New Jerusalem (Revelation 20–21; Cohn [1957] 1970; McGinn 1979; McGinn 1994).

The battle against Islam and the expansion of the Christian kingdoms was inspired by the predictions of a tradition named ‘neo-Gothic’ due to its longing for the restoration of the old Hispania. The Islamisation of the Iberian Peninsula was considered punishment for the fall of the Visigoth kingdom and required redemption through the Reconquista, which had been heralded by prophecies attributed to Saint Isidore of Seville and was recalled by thirteenth-century chronicles such as Historia gothica by Rodrigo Jiménez de Rada or Estoria de Espana by Alfonso X of Castile. These ideas, which drove the campaigns against al Andalus during the Middle Ages, predicted the definitive defeat of Islam and were invoked until the conquest of Granada in 1492 and the final expulsion of the Moors in 1609 (Milhou 2000, pp. 12–13).

In the Crown of Aragon, the royal chronicles of James I, Bernat Desclot, Ramon Muntaner and Peter IV the Ceremonious, written in Catalan and not lacking in narrative power, offered a providentialist view of the king’s role in the war as a legislator and Christian knight in the battle against Islam and foreign enemies (Hauf 2004). These royal chronicles contained numerous predictions of a glorious destiny for the monarchs of Aragon, all the way from their birth to the moment of taking on fearsome enemies, or simply as instruments of the divine will. In his chronicle, James I told of the vision of a Franciscan from Navarre who predicted that a king of Aragon named James would restore Christianity in Spain (James I [1883] 1887, chp. 389, II, pp. 509–10). Later, Desclot and Muntaner, writing about the king’s birth, described the miracles that accompanied it, to which the king himself had alluded in his chronicle (Riquer 2000, pp. 49–93; James I [1883] 1887, chp. 5, I, pp. 9–11; chp. 48 I, pp. 100–2). Muntaner also recalled a sibyl’s prophecy about James II’s triumph in Sardinia, seeing the pallets on the Aragonese coat of arms as rods that would punish enemies: ‘And I wish you all to know that this is the lion of whom the Sibyl tells us; he with the device of the pales, will cast down the pride of many a noble manor’ (Muntaner [1920–1921] 2000, p. 545, chp. 272). Identifications with biblical heroes such as David and Moses can also be found in these texts to justify acts of war and claim divine support for the Aragonese cause. For instance, Peter III, who rescued Sicily from Angevin rule, was compared with Moses as the emancipator of the Israeli people in Egypt, while the defeat of the House of Anjou was equated with the disasters suffered by the Pharaoh and his army in the Exodus (Aguilar 2007).

Peter III’s claim to the Staufen legacy through his wife, Constance, and the War of the Sicilian Vespers (1282–1286) fostered the assimilation of Joachim of Fiore’s prophetism and its pseudo-Joachimite offshoots. This approach was characterised by political support of Ghibelline power as an agent for spiritual renovation and a tool to reform a corrupt Church, which wasted no time identifying with the Emperor of the Last Days of Judeo-Byzantine millennialist tradition (Alexander 1978; Milhou 1982; Reeves [1969] 1993, pp. 306–14; Möhring 2000; Potestà 2014). It was Arnau de Vilanova who initiated a radical, pseudo-Joachimite shift in these prophetic traditions in a number of his writings and identified Frederick III of Sicily, of Aragonese stock, as the protagonist of the renovatio mundi, which was to purify the Church and Christianity in general, convert Muslims and establish true evangelical life (Lee et al. 1989; Reeves [1969] 1993, pp. 314–18; Rodríguez de la Peña 1996–1997; Phillimore 2004; Rodríguez 2008). In the prophecy Vae mundo in centum annis, he heralded the arrival of a king, a New David, who would destroy the power of Islam in Spain and Africa until establishing a universal monarchy; the Emperor of the Last Days would then turn into a bat, which would emerge at the end of days to defeat the Antichrist, restore the Temple of Jerusalem and establish the millennium before the Final Judgement. Vilanova’s allegories of the bat and of the dragon of the Apocalypse, previously associated with Frederick II, became symbols of messianic hope embodied by the Crown of Aragon’s royals. This bore significant political connotations within the context of the exaltation of the dynasty and its conflicts with the Papacy during its Mediterranean expansion in Sicily, Sardinia and, later, Naples.

Similar prophetic ideas and images were reworked by Catalan-language authors throughout the fourteenth century, as attested by a host of preserved manuscripts (Bohigas 1920–1922; Bohigas 1928–1932; Bohigas [1928] 1982); sources collected by (Rousseau-Jacob 2015). Joachimite piece Summula seu Breviloquium super concordia Novi et Veteris Testamenti, written in the mid-fourteenth century, is one of the most examined examples of a reshaping of prophetic expectations in accordance with religious and political circumstances. An interpretation of history was applied to contemporary events to create the sense of a climax, of the imminent arrival of a new era, heralded by extraordinary signs and figures, which would leave the calamities of the present behind and would pave the way for the Kingdom of Heaven on Earth (Lee et al. 1989; Perarnau 1991; Hauf 1996).

The Crown of Aragon thus became the centre of eschatological expectations in the fourteenth century, taking on the role Jean de Roquetaillade had assigned to the French monarchy (Aurell 1990, pp. 319–33). While royal chronicles injected providential meaning into the historical mentality of the courtly and ecclesiastic circles that read them, the Joachimite or pseudo-Joachimite prophetism put forward by Arnau de Vilanova, by Peter John Olivi in Postilla super apocalypsim, by the Breviloquium and by an anonymous writer in De triplici statu mundi, among others, would reach wider groups linked to the Beguines, Lullism, Spiritual Franciscans, and all those who longed for a renovatio mundi faced with the impending Final Judgement, through preaching and circulation through other media (Rousseau-Jacob 2015). Aspirations to reform the Church, to convert Muslims and Jews definitively and to install a regime of justice and peace after the defeat of the Antichrist won many over, thanks to the power of the millennialist beliefs and hopes that grew stronger with every crisis (Lerner 1983; Hauf 1996). These prophecies contained a hint of subversion that made their followers a target for surveillance and persecution by the ecclesiastic authorities, such as inquisitor Nicolau Aymeric, or were tolerated when distributed in the vulgar tongue alongside educational, pious materials that could be read and shared aloud, when they took the form of brief, simple texts, such as the summary in Catalan of Roquetaillade’s Vademecum in tribulatione for laypeople (Hauf 1996; Kneupper 2016).

The monarchy was aware of the usefulness of these ideas to surround the figure of the king of the Crown of Aragon with messianic connotations, thus placing upon him, as Brother Dolcino had done with Frederick III of Sicily, hopes for Church reformation, the crusade against the infidels, the conversion of the Jews and the defeat of the forces of evil, which were conveniently equated with Islam, rival powers and even the Papacy when it opposed the Crown’s plans or sides had to be taken in the times of the Western Schism. The kings made use of these expectations on solemn occasions such as speeches before their kingdoms’ courts, evoking the feats of their forebears and classical and biblical examples with persuasive rhetoric and as much emphasis as they used to highlight the providential mission that ensured their subjects’ support (Cawsey 2002).

Author Francesc Eiximenis (c. 1330–1409), who moved between the Court and an urban audience, was partial to preaching and the unorthodox spiritual aspects of the Beguines and other dissident movements and found himself unable to avoid conflict with the monarchy’s interests. He irritated John I by evoking prophecies that heralded a change in the political order, including the end of all monarchies (except the French one), the taking of Jerusalem, the conversion of the Jews and the establishment of millennialist popular justice (Viera 1996). Following a reprimand from the monarch and the anti-Jewish pogroms of 1391, he changed his mind and removed the most problematic passages from his book Dotzé del Crestià in order to postpone the arrival of the millennium and safeguard the Aragonese monarchy’s mission and its alliance with the Papacy represented by Pedro de Luna’s title of Benedict XIII (Bohigas [1928] 1982; Lerner 2001, pp. 101–10). His contemporary saint Vincent Ferrer (c. 1350–1419) wrote an exposition and defense of his apocalyptic views in 1412 and announcing the arrival of the Antichrist, supposed to be born in 1403, and the imminent end of the world was the core of his preaching which contributed to increase apocalyptic expectations throughout his mission (Daileader 2016, pp. 137–59).

Meanwhile, in his 1365 visions, Infant (Prince) Peter of Aragon (1305–1381), who began to practise as a Franciscan in 1358, saw Henry II of Trastámara as the Spanish lion that would crush Islam, free the Jews and go to the Holy Land to worship at the tomb of Jesus, thus discrediting the French monarchy, in which Roquetaillade had put his trust. In one of his visions in Franciscan convent of Valencia, he heard a voice that urged him to join the Castilian troops against the Muslims, making a comparison with the Israelite army entering the promised land (Pou [1930] 1996, pp. 461–561; Lerner 1983, pp. 135–53; Genis 2002, pp. 129–39). This providential support of the Trastámara dynasty doubled in value when, as part of the Compromise of Caspe (1412) Ferdinand of Antequera was named as the new Aragonese monarch. This meant that the two political branches of apocalyptic prophetism—the Castilian neo-Gothic version, which backed the Trastámara family, and the Franciscan Ghibelline variety, inspired directly or indirectly by the Joachimites—converged on the throne occupied by Ferdinand’s sons, Alfonso V the Magnanimous (1416–1458) and John II (1458–1476). Ferdinand II (1476–1516) would make consistent use of prophecies, combining Castilian Neo-Gothic contributions, which foretold the restoration of unity and the liquidation of al-Andalus, with the apocalyptic predictions of the New David, restorer of Christianity, reformer of the Church, converter of Jews and champion who would lead the crusade to Africa and then to Jerusalem as a universal monarch (Duran 2004, pp. 157–258; Duran and Requesens 1997, pp. 50–67).

Prophetism strengthened Ferdinand II’s royal power and his legitimacy as the king consort of Castile through his marriage with Isabelle I, who was focused on defending her right to the throne against her adversaries. In 1486, Rodrigo Ponce de León, marquis of Cádiz, identified Ferdinand as the New David, the Hidden King and the rightful successor to Fernando III who would conquer first Granada then Jerusalem and restore Christianity. Then, in 1495, when visiting the Catholic Kings, German humanist and traveller Hieronymus Münzer cited a prophecy attributed to Joachim of Fiore to recognise them as the monarchs that were to defeat Islam definitively, take the Holy Places and evangelise a new world (Milhou 1983; Milhou 2000).

But the forces of millennialist prophetism could easily take on a subversive appearance. The death of Ferdinand II in 1516 left a vacuum that the new king, and emperor from 1519 onwards with the title of Charles V, could not fill; his figure was moulded as the humanist ideal of a Christian prince, which created a fracture in Hispanic political eschatology (Pérez García 2007, pp. 212–22).

3. Anachronistic Images, Prophetic Images?

Recognising reflections, connotations or rhetorical figures of an apocalyptic prophetic message and of the political eschatology of the Crown of Aragon in the preserved images available is not an easy task. It is assumed that a research strategy based on reading clues, traces and legends could offer additional insight of otherwise unnoticed intentions in images of the past (Ginzburg [1989] 2013, pp. 87–113). Prophecy revealed what was hidden. The message may appear embedded, even encrypted, in artworks and resist conventional iconographic analysis. Revealing it requires much more than examining texts and comparing with other earlier or contemporary images. Firstly, fourteenth- and fifteenth-century visual culture was only one pillar of what Zumthor (1987) called the triangle of medieval culture: oral expression, texts and figurative images interact in a field of communication and representation that involves all kinds of audiences. Although scholarly efforts have mainly focused on studying prophetic manuscripts in circulation, it is important to remember that most people were introduced to these ideas via oral means: speeches, sermons, narrations and readings. Moreover, the mnemonic value of images and the use of them in preaching suggest the multiplicity of meanings each story or figure may take on, codified by allegory and other rhetorical devices that make them enticing to decipher and that stick in the memory (Carruthers 1990; Bolzoni 2002; Baschet and Dittmar 2015; Serrano 2017). Reading or hearing a prophecy might well lend a messianic sense to royal epiphanies while a rhetorical allusion to an iconographic type or a particular image could put familiar representations under a different light in an eschatological context.

From a reception point of view, many of these images are retrospective, historical to an extent, and anachronistic, because they were created at another time or were projected to the future through memory and imagination and, in any case, continued to be observed and interpreted long after the time of creation (Didi-Huberman 2000; Nagel and Wood 2010). Their potential prophetic value comes down to their shaping of an account of the past, their structuring of it so that the future can be glimpsed and the end of time can be heralded, as is characteristic of the apocalyptic imagination. In addition to their historical or legendary character, most of these depictions were referring to a mythic past but were significant models for the present of their viewers and acquired a prospective value. They heralded the arrival of a messianic king who would fulfil prophetic expectations of victory, religious reform and conversion. Moreover, cyclical commemoration at urban festivals encouraged new interpretations of the past events adapted to day-to-day concerns and problems. Reception of images and performances appealed to irrational expectations and feelings difficult to read apart from formal and written records, but might be embedded in clues and traces present in the local historical context.

3.1. The Hero’s Task

The monarchs, now cast as the protagonists of great feats, were soon represented in a variety of visual media inspired by the courtly exaltation of official chronicles (Serra 2002; Serrano 2011a, 2011b; Molina 2013). The battles evoked through paintings had taken place at a specific time, but their figuration played with a sense of ambiguity in the representation of time and space. The scene contains barely any topographical information and time seems to stand still at a certain point of a cyclical journey that renews in pursuit of an end. This cyclical view of time set by liturgy and the festive calendar encouraged expectations of the return and periodical renewal of the great events of the history of salvation and, by extension, of human history. Within this context, we can reconsider battle scenes such as the paintings of Alcañiz Castle (Teruel), of the Saint George altarpiece (London, Victoria and Albert Museum 1217–1864, Figure 1), of the altarpiece dedicated to the same saint at Jérica Town Hall, and of Alfonso V’s prayerbook (Psalter and Hours, Dominican use, London, British Library, Additional 28962, f. 78r), as well as the piece painted by Pere Niçard in Mallorca, circa 1468–1470 (Mallorca, Museu Diocesà). On the murals at Alcañiz, it is possible that the representations of the taking of a city by the king of Aragon or the images of a military campaign with participation from knights of the Order of Calatrava, the lords of the castle, allude to episodes such as the taking of Valencia (1238) and the crusade against Almería at the time of James II (1309–1310), that Arnau de Vilanova encouraged with his work Regimen castra sequentium, as a reminder of the battle against Islam (Español 1992, pp. 30–32; Vilanova 1981).

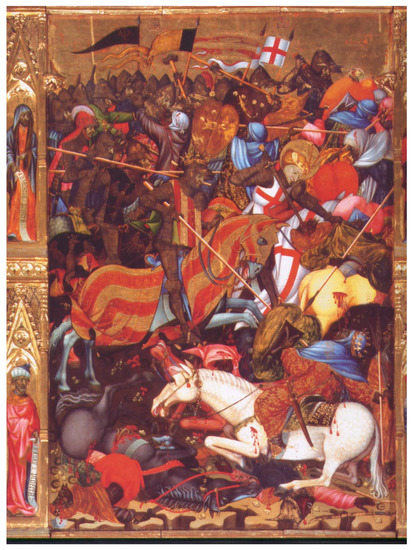

Figure 1.

Battle scene from the Altarpiece of Saint George, Valencia. London, Victoria and Albert Museum, 1217–1864. Used by permission.

The altarpieces in Valencia and Mallorca were commissioned by the brotherhoods dedicated to Saint George and were deeply rooted in each city. Both brotherhoods saw James I’s conquest as a decisive, historic event, during which divine favour had been displayed through the miraculous appearance of Saint George next to the Christian armies, just as he had helped the crusader army in their taking of Antioch. This episode was commemorated annually with a popular festival in which the whole urban community participated and the royal standard substituted the presence of the monarch himself. According to the classic doctrine of the king’s two bodies, the heir embodies dynastic continuity (Kantorowicz [1957] 1981), while at these events, the flag evoked the figure of the king, who was rarely present in the city for the occasion, to renew the meaning of the conquest as a crusade against the infidels. The standard bearer (the Criminal Justice in Valencia, the youngest Juror in Mallorca) was therefore dressed like the king, with armour, surcoat, gloves, helmet and winged dragon crest. The conquest sermon given during the festival in Valencia and Mallorca was based on passages from the royal chronicle or Llibre dels fets that described the taking of the two cities, and conferred a providentialist power on the events considered a crusade while projecting them onto the audience’s present circumstances (Narbona 2003, pp. 173–84; Granell 2017b; Molina 2018). The depiction in altarpieces of the battle of El Puig with saint George fighting side by side the Christian army referred not only to a historical event, but refreshed the crusader ideal in 15th century Valencia and might well have inspired Germanias rebels a hundred years later, if we account for the prominent role of the Saint George brotherhood at the beginning of the revolt and their meetings taking place in Saint George’s church where the retable now in Victoria and Albert Museum was then on display (Pérez García 2017, pp. 33–54; Gil 2019, pp. 46–68). A miniature with a similar compositional structure is included in Alfonso V’s psalter-book of hours, alongside the prayers the king must recite before entering battle against the infidels: preces pro intrandum bellum contra paganos (f. 78) from psalm 78, with a lament for the destruction of Jerusalem and the invocation of divine assistance. The royal emblems of millet and an open book personalise the king of Aragon’s heraldry, which appears to be a crusader and a fleeing army, which, by its weapons and saddles, is characterised as Muslim (Woods-Marsden 1990, pp. 14–15; Español 2002–2003, pp. 107–8; Molina 2011, pp. 106–7).

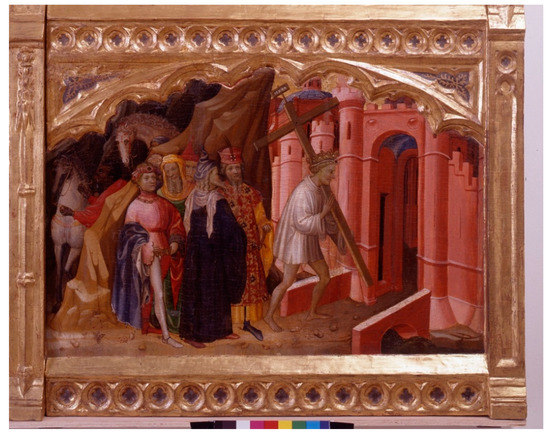

The idea of the crusade had been encouraged by the so-called Reconquista, but in terms of political eschatology, it went beyond conquering Iberian territories and aimed to take the battle against Islam to north Africa and Egypt and, ultimately, take back Jerusalem. This mission had been foreseen for the New David, or the bat in Vilanova’s prophecy. Its millennialist connotations are present in the representation of the Battle of Milvian Bridge on the Santa Cruz altarpiece at the Museo de Bellas Artes of Valencia (n. inv. 254), where Constantine’s troops appear as a crusader army defeating Maxentius’s legions, which are dressed and represented with signs of otherness associated with Muslims: dark skin, turbans and Andalusian saddled horses. Constantine himself is depicted twice: first envisioning the Christian sign of victory and then leading his army with a golden cross and the imperial eagle on his badge. This altarpiece, commissioned by Valencian official Nicolau Pujades, who was responsible for the Mudejars of Valencia and carried out diplomatic missions in the Nasrid Kingdom of Granada, responds to the crusader spirit that drove the two expeditions against the Barbary Coast (the Armada Santa) triggered by the attack against Torreblanca (Castellón) and the theft of the Eucharist from the local church (Díaz 1993, pp. 142–201; Sastre 1996). King Martin I himself congratulated the jurors of Valencia on joining the punitive expedition against the Barbary Coast, evoking Saint Paulinus of Nola’s personal offering to rescue his captive parishioners and examples from Roman history of the battle against Carthage: ‘and you, without a doubt, will have power over the successors to the aforementioned Africans, as Africa is today known as the Barbary Coast’ (Rubió 1908–1921, pp. 1, 390–91). It is plausible that the monarch may have wanted to recognise himself either in the victorious Constantine at Milvian Bridge or in the image of Heraclius returning the cross relic to Jerusalem in the final scene on the altarpiece (Figure 2), as he was a keen collector of relics and perhaps hoped, next to Benedict XIII, to take on a similar role to that of the Emperor of the Last Days evoked by Eiximenis at that time. In fact, Martin I had written to his son to recover a sword of Constantine from the royal palace in Palermo (Serrano 2015b, p. 661) and the aim of the 1398 and 1399 military expeditions was to retrieve the consecrated hosts of Torreblanca.

Figure 2.

Altarpiece of the Holy Cross: Heraclius returns the Holy Cross to Jerusalem. Valencia, Museo de Bellas Artes, n. inv. 254. Used by permission.

The coronation of Ferdinand of Trastámara in Zaragoza and the 1414 royal entry to Valencia were occasions used to extol the new king. As he was elected as part of the disputed Compromise of Caspe (1412) as a descendent on the female line, with the decisive support of Saint Vincent Ferrer, it was important to legitimise his ascent to the throne with figurative, extravagant language. Beyond genealogy, Ferdinand had earned the right to the throne through conquest, by subduing his rival candidate, James of Urgell, through force. Ferdinand’s success against Islam on the peninsula during the Granada War acted as a further endorsement of the king. The jurors of Valencia congratulated Ferdinand on taking Antequera in a 1410 letter, ‘praying the Lord helps you to fulfil your holy purpose of conquering and submitting that perverse nation to your hands, populating its kingdom with faithful Christians and adorning it with churches and altars where God’s name will be praised,’ (Rubio [1985] 2003, p. 213). A Valencian tapestry from the time portrayed this Battle of Antequera (García Marsilla 2011, pp. 180–81). At the coronation, Ferdinand was presented allegorically as being favoured by fortune, blessed by the Virgin and a hero in the fight against the infidels (Salicrú 1995; Massip 2010). It was no coincidence that these themes came up again on the carriages with tableaux vivants that paraded through Valencia for his royal entry, following the same route as the Corpus Christi procession (Narbona 2003, pp. 85–100; Cárcel and Garcia 2013; Massip 2013–2014). A millennialist tone was evident, partly inspired by the figure of Saint Vincent Ferrer, to whom one of the carriages was dedicated (Calvé 2019), and was used to strengthen Ferdinand’s legitimacy. The emblems of the griffin, the eagle and the tower alongside the Virgin in the garden combined a chivalric appearance with the devotion to the Virgin Mary that distinguished the new king (Ruiz 2009, pp. 74–81). Meanwhile, other carriages, such as those of the Wheel of Fortune and the Seven Ages of Man, lent themselves to more messianic connotations, like the idea of a monarch chosen to rule a world heading to its last age before the millennium (Massip 2013–2014).

3.2. Between Moses and Solomon: A Legislator by Divine Mandate

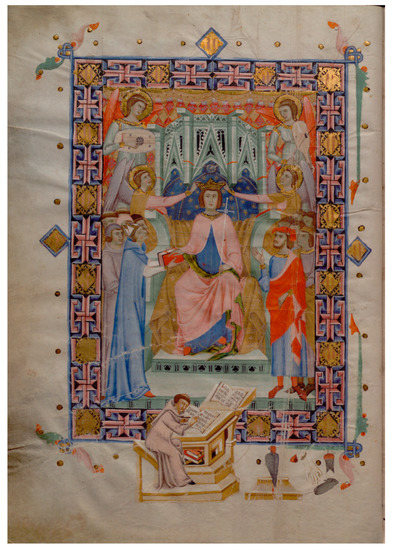

In the case of Valencia and Mallorca, the monarch had also acted as the founder of the kingdoms by granting them their own laws and institutions. From James I, the role of the king as lawgiver was conceived not only on the basis of Roman imperial codes but also implied a theological aspect, since God had appeared as legislator through the ten commands. Veneration of the king and his direct connection to God as lawgiver of the Old Covenant did have figurative consequences, serving as a way to exalt the royal image beyond conventional iconography. This was confirmed by the images of the king as legislator heading the Furs de València and Privilegis del Regne de Mallorca codices. These two manuscripts are especially interesting in terms of the different routes of association with the divine they propose. On the eve of the decisive Corts sessions of 1329–1330 in Valencia, when Alfonso IV declared the text lex universalis et unica dicti Regni, the authorities ordered a manuscript of the Furs de la ciutat e regne de València, a collection of the laws passed by monarchs from James I the Conqueror until that time (Villalba 1964, pp. 33–36; Ramón 2007, pp. 30–33). At the beginning of the book, we find illustrations of the monarchs sitting upon a throne in the shape of a bench, holding a sword as a symbol of justice, as the embodied sources of the city’s and the kingdom’s exclusive laws. These portrayals aimed to highlight both the nature of the laws and the monarch’s role as founder and legislator. One of them displays a king, likely Alfonso IV, before Christ in the border image in f. 113r of the Valencian Furs, receiving the book (Ramón 2007, p. 32; Serrano 2008, pp. 62–70). Alternatively, Llibre de franqueses i privilegis del Regne de Mallorca (c. 1334–1341) goes further by depicting a monarch-legislator in sede majestatis, sitting on a throne, under an extravagant canopy and flanked by angels who crown him while he delivers the codex of privileges being copied by the scribe at the bottom (Arxiu del Regne de Mallorca, codex 1, f. 13v, Figure 3). The supposed intention of both opulent manuscripts was for the city governments to reassert the freedoms and privileges of both kingdoms, but this assertion was compatible with the figurative exaltation of royal power embodied by the providential monarch, not to be seen as an individual portrayal, but rather as a generic, dynastic image of the founder and original legislator of Mallorca and Valencia, as confirmed by the heraldry displayed in the border. To some extent, the Mallorcan codex signals that royal power is of divine origins and is consistent with the pattern of an ‘in majesty’ image, but this is subject to the confirmation of the privileges updated by scribe Romeu des Poal when he copies them onto the manuscript (Escandell 2012, pp. 333–37). Certainly, these symbolic depictions lacked of apocalyptic sense, but prepared the ground for a messianic perception of the king as sacra majestas, enhanced by a political propaganda nurtured by Ghibelline and Vilanova’s prophetism in order to consolidate union of a Mediterranean power under the crown. Kingship was not only law-centered by involved also a new sense of authority and power in coronation ceremonies, funerals and speeches to the parliaments as much as royal imagery to represent a king of justice, never defeated (Corrao 1994, pp. 133–56; Serrano 2017, pp. 392–422).

Figure 3.

Llibre de franqueses i privilegis del Regne de Mallorca. Mallorca, Arxiu del Regne de Mallorca, codex 1, f. 13v. Used by permission.

3.3. The New David

The restorer of lost order, the renovatio mundi, had been equated in Arnau de Vilanova’s prophecies with the New David, who was to rebuild the temple on Mount Zion. These prophecies were presented to James II and Frederick III of Sicily in Interpretatio de visionibus in somnis dominorum Iacobi secundi regis Aragonum et Friderici tertii regis Siciliae eius fratis (1309), reworked in Catalan as Raonament d’Avinyó (1310), and left the identity of the papa angelicus and the New David ambiguous, but Frederick, then named the King of Trinacria, wasted no time in taking on this role, supported by the Fraticelli and Brother Dolcino, in particular. The Aragonese royals, meanwhile, like others, were tempted to identify themselves with the kings of the Old Testament, especially David and Solomon, as examples of wise, God-fearing monarchs. In the prologue of his chronicle, Peter IV the Ceremonious identified with David, as he believed God’s will had saved him from all dangers so that he might fulfil his providential mission: ‘And if we consider the great deeds performed in our time in the Kingdom of Aragon, as another David, whom it was said in 2 Samuel, 12: 10: “The sword shall not depart from my house.” Thus, in the time of Our rule, the knife of an enemy, whether of a stranger, a vassal, or of Our counsellors, has almost never departed from Our house. And, truly, Our wars and tribulations were prefigured in the wars and deeds of David’ (Peter IV 1980, pp. I, 128–29). However, the use made of the kings of Israel seems consistent with the prophetic connotations of the Aragonese monarch as the New David, not through personal identification but through association with the whole House of Barcelona. There is no visible intention to recognise a particular king in the images of David, but rather a foretelling of the dynastic will to carry out reforms and restore Christianity after the millennium. This can be perceived through David’s association with James I at the beginning of the text and through the royal shield of Peter IV the Ceremonious on the frontispiece of the Aureum opus of Alzira (Valencia), which is, in fact, a summary of the laws and privileges granted to the city of Valencia (Alzira, Archivo Municipal, Còdexs especials, 0.0/3, f. 1r). This codex, ordered by the jurors of Valencia, was a response to the evocation of the king who founded the kingdom as an exemplary figure who had evangelised the lands conquered by the Moors, granting them their own laws. In chronicles, the king’s longevity was compared to that of David and Solomon (Llibre dels fets, chapter 562 (Serrano 2008, pp. 62–70; Barrientos 2009, pp. 425–34; Granell 2017a, pp. 56–57)).

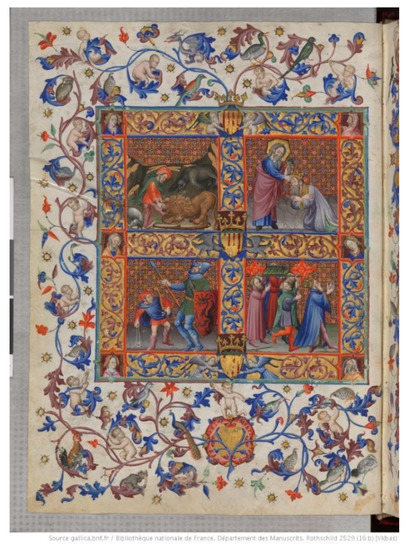

In the solemn Breviary of king Martin, the psalms are accompanied by a cycle of four scenes from David’s life on every page, the first of which is surrounded by crowned Aragonese emblems with, from top to bottom, putti, eagles, and angels wearing tunics, while in the corners, we find unidentified male and female busts (Bibliothèque nationale de France, ms. Rothschild 2529, f. 17v, Figure 4). The scenes on the left are from David’s youth and depict him as the vanquisher of the lion and of Goliath, while on the other side, he is portrayed being anointed by Samuel and leading the Ark of the Covenant procession into Jerusalem. In the latter images, the monarch is characterised as an ageing man with a crown dressed with royal decorum: a stark contrast to the younger, slight man wearing a hat facing the lion and the Philistine giant (Planas 2009, pp. 61–66). On this page, we also find the royal motto As a far fasses (‘do what you must’) at the bottom of the border, which corresponded to the Order of the Belt (‘Orde de la Corretja’), linked to his time as king of Sicily (Riera 2002, pp. 48–49). All of this suggests an association between David and the recipient and supporter of the illuminated manuscript, who had reached the throne 40 years after his brother John was killed accidentally, and who would bring a significant collection of relics to the royal chapel in Barcelona. When reproached by his adviser Francisco de Aranda for the pomp of the solemn coronation in Zaragoza, Martin invoked the precedent David and Solomon, among other kings of Israel (Rubió 1908–1921, pp. 2, 365–67; Serrano 2015b, p. 673). Martin was also represented on a throne with an open book in which the beginning of the Miserere (Ps 50, p. 3) was visible on the genealogical scroll of Poblet Monastery (Serra 2002–2003, p. 71).

Figure 4.

David stories in the Breviarium secundum ordinem Cisterciencium, also known as Breviary of king Martin of Aragon. Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, ms. Rothschild 2529, f. 17v. Used by permission.

As the Breviary was completed under the reign of Alfonso V, it is unsurprising that this monarch also insisted on being associated with David, the author of the psalms in his Psalter and Hours now in London, British Library Additional MS 28962. Whether praying or seeking forgiveness at the beginning of the Penitential Psalms (f. 346v), and particularly in mystical visions such as that of the duo viri—Saint Dominic and Saint Francis praying to Christ, flanked by the Virgin and Saint John the Baptist, in a city identified as the capital as one of the king’s states—at the beginning of the Miserere (f. 67v, Figure 5) identification of Alfonso with David is suggested (Español 2002–2003, pp. 96–97, 104–5; Planas 2015, pp. 232–36). This apocalyptic vision ties in with a common theme in Joachimite prophetism: the strength of the mendicant orders through their founders, who intercede before Christ, about to shoot arrows at the world (Arcelus 1991, pp. 21–112). This vision, refocused in the thirteenth century in favour of the Dominicans by Géraud de Frachet, retained all its popularity and relevance: so much so that it was represented on one of the carriages involved in the royal entry of Ferdinand I of Aragon, father of Alfonso V, into the city of Valencia in 1414 (Cárcel and Garcia 2013, pp. 12–18). It was described as ‘the vision Saint Dominic and Saint Francis saw with the three lances, denoting the end of the world’ and is not to be confused with the one Vincent Ferrer had during his illness in Avignon (Calvé 2016, pp. 186–97). Seeing from the initial letter alongside the guardian angel, the king discreetly becomes a visionary of the imminent end of the world and a mediator between the fearsome power of God and his people.

Figure 5.

Psalter and Hours, Dominican use (the ‘Prayerbook of Alphonso V of Aragon’). London, British Library Add MS 28962, f. 67v. Used by permission.

In that royal entry into Valencia in 1414, the dynasty’s new monarch was welcomed like a New David. Saint Vincent Ferrer had argued the legitimacy of the Trastámara candidate, even though he was a descendent to the Aragonese dynasty through the maternal line, by invoking the precedent of Jesus through Mary (Gimeno 2012) and the vision of Christ with the three lances, foreshadowed by the three darts thrust by Joab through the heart of Absalom, who would not wait for the succession (2 Samuel 18, pp. 9–15). Ferdinand I, meanwhile, had been patient and entrusted the verdict on his legitimacy to divine judgement; the electors at Caspe named him the heir, with decisive intervention from Vincent Ferrer in 1412, and thanks to his victories against the Moorish kingdom of Granada, he appeared to be a promising messianic monarch (Calvé 2019, pp. 69–70). Despite this dynastic change, the royal aura of David and Solomon continued to be projected onto the image of the king of Aragon.

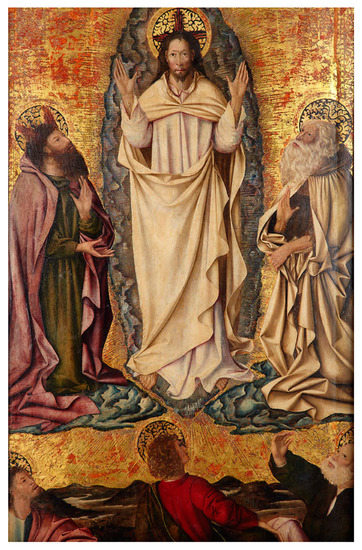

3.4. The Transfiguration: A Triumphant, Conciliatory Vision of Messiah

While Alfonso V the Magnanimous was working on the crusade plan launched by Valencian Pope Callixtus III, the Turkish advance was reaching the gates of Belgrade, where John Hunyadi’s and John of Capistrano’s victory halted Mehmed II’s army on 21 July 1456. News arrived in Rome on 6 August and it was commemorated with the Feast of the Transfiguration by Callixtus III, who had also requested that all churches sound their bells at midday during the siege on the Serbian capital. These events were echoed in the Crown of Aragon, where postponing sending a crusader contingent was not to hinder symbolic support for this battle against the infidels (Navarro 2003, pp. 149–50). Alfonso de Borja had been appointed bishop of Valencia in 1429 while he served as a special adviser to king Alfonso. To this backdrop, Joan de Bonastre, also a loyal adviser to Alfonso V, commissioned an altar in 1448 for Valencia cathedral with a triple dedication—to the Saviour, to Saint Michael and to Saint George—on which the Transfiguration would be accompanied by images of the two warrior saints par excellence (Saralegui 1960, pp. 5–10; Deurbergue 2012, pp. 67–70; Figure 6). A likely identification of the painter as Jacomart connects the preserved panel (Valencia, Museo de la Catedral) with the court artist of king Alfonso (Ferre 2000, pp. 1681–86; Gómez-Ferrer 2017, pp. 20–21). The use of the Transfiguration in the fight against the infidels was common in the Crown of Aragon in the fifteenth century, which explains the proliferation of the subject before and after the feast was established by a Valencian pope who had also supported Alfonso V in his campaigns and called for the Aragonese monarch to lead the crusade (Navarro 2003, pp. 81–180). Humanists like Flavio Biondo, Giannozzo Manetti, and Matteo Zuppardo in Alfonseis were keen to have him at the head of the crusade and attributed the Belgrade victory to the assistance given to Hunyadi and Scanderberg by Alfonso as the rightful figure who would continue the feats of Pompey the Great and Godfrey of Bouillon. Manetti attended a religious service in Naples Cathedral on 29 September 1455, Saint Michael’s Day, at which Alfonso V was expected to take the cross against the Turks, although this ended up happening on All Saints Day of the same year thanks to decisive mediation from Manetti (Navarro 2003, pp. 98–100; Botley 2004; Molina 2011, p. 99). Transfiguration had come back to the forefront in the Crown of Aragon over the course of the fifteenth century, perhaps thanks to the opportunity to confirm Christ’s role as the Messiah heralded by the Old Law and prophets in a context that was against Judaism but encouraged the conversion and assimilation of Neophytes; bishop Jaume Péreç of Valencia (1408–1490), in his Tractatus contra Judaeos, contended that the Old Covenant could not stand alone and was prefiguring the New Covenant (Peinado 1992). The parallel between transfigured Moses descending from the Sinai and the radiance of Jesus face and robe was a point of Jewish-Christian controversy (Moses 1996, pp. 20–49) and could be reinforced by the similar appearance of Christ and Moses in their portrayals, especially in the crossed nimbus of Christ and the red horns on Moses’ forehead, as can be observed in the Valencian panel, let alone the major role of Elijah and Moses in the depiction of this scene, especially if compared to those of apostles Peter, John and James, overwhelmed witnesses of the theophany. It was expressed through the panel paintings of Pina (Teruel), Xiva de Morella (Castellón), an altarpiece from Barcelona Cathedral, work by Bernat Martorell (ca. 1445–1448) and another, later, altarpiece in Tortosa Cathedral (ca. 1466–1480) (Molina 1999, pp. 57–87; Alcoy and Vidal 2015). This theme confirmed Christ as the Messiah and heir to a Jewish tradition to be assimilated, and perpetuated a resounding victory in the liturgical calendar for all of Christianity against its most feared enemy. The sense of eschatology in the Transfiguration as a foretaste of the glory of Jesus at the Parousia as he discloses another world was also rooted on Jewish traditions about the enthronization of the Messiah (Ramsey [1949] 2009, pp. 101–11).

Figure 6.

Master of Bonastre (Jacomart, also known as Jaume Baçó?), Transfiguration Altarpiece. Valencia, Museo de la Catedral. Used by permission.

3.5. The End of Days

The momentum behind prophetic thought depended on the sense of proximity of the millennium of peace and happiness that would last from the defeat of the Antichrist until the Final Judgement. At that time, the Emperor of the Last Days had to complete his mission: defeat the forces of evil, reform the Church with consensus from the papa angelicus, and convert the Jews and Muslims, by force or otherwise, to restore the holy city of Jerusalem. Such a cycle of spectacular visions of universal proportions was unlikely to find a comprehensive, eloquent visual translation, but it was not implausible for it to achieve resonance through images of the final stages liable to be investigated later.

Visual formulations created from the late-fourteenth century that heralded the coming millennium and were inspired by the work of Francesc Eiximenis renewed expectations in the upcoming millennium (Rodríguez 2005, pp. 117–21). The Final Judgement panel now in Munich, Alte Pinakothek, attributed to Gherardo Starnina, depicts among the blessed a pope, a bishop, an emperor, a king wearing the golden collar of a double crown and a queen, and some of them have been persuasively related to historical characters as king John I and queen Violant de Bar, or rather to king Martin I and queen Maria de Luna. The landscape of the doomsday has also been compared to those of Mallorca or the Charterhouse of Valldecrist, the latter reputedly reminiscent of the valley of Josaphat as the place of divine judgement (Miquel 2003, pp. 793–94; Serra 2016, p. 66; Palumbo 2015, pp. 325–54). In any case, a late sixteenth century source described in Valldecrist a painting of the Final Judgement in the presence of king Martin and queen Maria, on Christ’s right hand side, to remember the visionary insight of the valley of Josaphat who inspired the foundation of Valldecrist, and a lost inscription confirming it in the cloister next to Saint Martin’s chapel (Diago 1946, pp. II, 177).

The Trinity adored by All Saints and Saint Michael altarpiece from Valldecrist (New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art 39.54, Figure 7) offers an evocative composition of Joachim of Fiore’s passage in his Liber figurarum on the millennium, the unity of the Church and the conversion of the Jews (Lerner 2001, p. 31), and especially the comment from chapter 20 on the Apocalypse in Eiximenis’s Llibre dels àngels, treaty V, chapter 37: ‘the shackling of the Devil and the kingdom of saints with Christ, for one thousand years, before the Final Judgement’ (Eiximenis [1392] 1983, pp. 117–19; Lerner 2001, pp. 107–9). Commissioned around 1400 by Dalmau de Cervelló i Queralt, governor of the Kingdom of Valencia and friend of King Martin, for the San Martín Chapel in the Carthusian Monastery of Valldecrist (Altura, Castellón) founded by the monarch, the piece’s side panels depict the Saints’ adoration of the Trinity (Serra and Miquel 2009, pp. 78–79). Here, redemption is seen in a clearly apocalyptic context: Christ’s merits earned on the cross and his status as the Son of God, evident through the Trinity formula, are strengthened by the intercession of the Virgin Mary and the vision of the blessed adoring the Trinity, includes the Old Testament Patriarchs and All Saints, each identified with their individual name and organised by hierarchy, marks the start of the millennium. It was expected around that time, as stated by Francesc Eiximenis in the final stage of the Western Schism, when Benedict XIII could embody the angelic shepherd who, with the final emperor, would lead to that vision (Lerner 2001, pp. 107–9). The funerary function of the altarpiece from Valldecrist and a comparison with other, related pieces made by Valencian workshops around that time, such as the one from Portaceli now shared between New York’s Metropolitan Museum (12.192) and Lyon’s Musée des Beaux Arts (inv. B 1174 a/b) (Fuster 2012, pp. 75–96), or the Pedro de Puxmarín altarpiece in Murcia Cathedral (circa 1419), only emphasise the prophetic virtuality of that vision, nuanced by a kind of Marian devotion that was deeply rooted in Valencia and in the Court of Martin I the Humane, where her immaculate conception was supported through the image of the Veronica (Crispi 1996; Rodríguez 2007, pp. 169–93; Deurbergue 2012, pp. 156–89). Indeed, Virgin Mary, dressed as the Queen of Heaven, sits beside the Trinity upon the throne of grace, in a prominent place according to the sense of piety and devotion idiosyncratic of the Court of Martin and particularly of his queen, Maria de Luna, lieutenant of the kingdom of Valencia between 1401 and 1406 and dedicatee of Eiximenis’ Scala Dei. Queen Maria made a donation of 9000 gold florins to Valldecrist Charterhouse in 1403, just a few months before she obtained a papal bull, allowing her and her ladies to attend the Mass at any Carthusian monastery in the Crown of Aragon as long as she did not spend the night at the Charterhouse (Silleras-Fernandez 2008, pp. 115–37).

Figure 7.

The Trinity adored by all saints. New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art. Used by permission.

In this piece, we see in nuce two main means of exaltation of the Aragonese kings’ messianic mission. Firstly, Marian devotion is translated visually through ex-votos and scenes portraying the monarchs at the Virgin’s feet. This distinctive way of venerating the Virgin Mary was assimilated and ramped up by the Trastámara dynasty even before they became kings of Aragon following the Compromise of Caspe (1412), as reflected in the Virgin of Tobed (Prado Museum, n° inv. P008117, Figure 8), following on from the exaltation of Mary exhibited by James I and other Aragonese monarchs of the House of Barcelona (Ruiz 2009, pp. 71–112). This panel, commissioned before Count of Trastámara became king Henry II of Castille, shows him and his wife, Juana Manuel, with their son John (I), and one of the daughters, maybe Joan, as donors praying at the foot of the Virgin of Santa Maria de Tobed (Zaragoza). Both father and son are represented as kings of Castille-Leon as the crown and heraldry make it clear. However, this Marian devotion rarely reached the apocalyptic dimensions seen in the Valldecrist altarpiece, where Virgin’s intercession is dramatic and spectacular.

Figure 8.

The Virgin of Tobed with the donors Henry II of Castile, his wife Joan Manuel, and two of their children, John and Joan (?). Madrid, Prado (P008117). Used by permission.

Secondly, the angels that appeared as the kings’ guardians or champions of celestial militias in the fight against evil sometimes transformed into carriers of a messianic message with roots in Judeo-Christian tradition (Horbury 2003, pp. 57–59; Potestà 2014, p. 160). The popularity of angelic themes in the decoration of spaces for worship in castles and palaces has been linked to a desire to imitate the Chamber of the Angels in the papal palace in Avignon (Español 1998, pp. 58–68). In Valencia, the Chamber of the Angels was to be one of the most representative rooms of the royal palace and is mentioned in a letter from Martin I to Pere d’Artés as part of the royal lodge in 1405 (Español 1998, p. 63). For this or an adjacent room in the same royal apartment, known as Real Vell, Martí Lobet sculpted three angels with weapons and elements of dynastic heraldry from polychrome orangewood in 1432. One of them carried a helmet in one hand and a sword in the other; the second, a helmet with a thick strap ‘with a vibra or bat’ and a silver rapier with a gold handle; and the third, a helmet with the Siege Perilous and enamelled silver leaves in one hand and a silver axe with wooden handle in the other. Martí Lobet also sculpted three beasts from the same wood: one half friar, half dragon; another in the shape of a griffin; and the final one an eagle, which were supposed to be fighting the angels. All of this encourages an eschatological interpretation, with malevolent creatures being overcome by angels with royal heraldry (Archivo del Reino de Valencia, Mestre Racional, record 11607, f. 38r; Sanchis 1924, pp. 19–20).

3.6. Prophetic Emblems: The Dragon and the Bat

Among the symbols carried by these victorious angels are the Siege Perilous—the king’s personal emblem, alluding to the seat reserved for the best knight in Arthurian legend—and a fantastical being somewhere between a dragon and a bat, which the dynasty had adopted in its heraldry and on royal seals since the time of Peter IV the Ceremonious. This winged dragon, sometimes associated with the Apocalypse and a symbol of the dynasty (dragó sounds like d’Aragó, meaning from Aragon), was ambiguous: enemies saw this fearsome beast as malignant and apocalyptic, while Aragonese supporters used this emblem to assert the Staufen legacy (Jaspert 2010, pp. 214–15). The symbol’s identification with the figure of the Emperor of the Last Days was present since Arnau de Vilanova and his prophecy Vae mundo in centum annis contained in De mysterio cymbalorum Ecclesiae (Milhou 1982, pp. 64–75). Indeed, it was this author who declared the bat would devour the Moors on the Iberian Peninsula as though they were mosquitoes and would continue with its triumphal march until reaching Jerusalem. Francesc Eiximenis (Lo Crestià first book, chapters 102 and 247) declared that ‘From this house [of Aragon] it is prophesied that a monarch must rule over almost all’, proclaimed the dynasty unbeaten (‘never has a King of Aragon been defeated on the battlefield’), praised the house’s relics, interpreted the pallets on the coat of arms as rods on which the Church would be reformed, and extolled the victories over Islam in Valencia and Mallorca, hoping that this would be continued in Africa and would reach the Holy Land (Bohigas [1928] 1982, pp. 99–104).

The determination to adopt a frightful symbol and preserve its messianic connotations explains why, in heraldry, the figure becomes a dragon, snake and bat hybrid. In fact, the Catalan word vibra refers both to a winged dragon and a bat, as often seen in Valencian documents; indeed, the dragon that killed Saint George was also a vibra (Vives 1900; Ivars 1923, pp. 66–112; Duran [1987] 2004, pp. 164–74).

The crest from the Armería Real of Madrid (D.11) is one of the most outstanding pieces of this kind still preserved (Figure 9). Made from parchment, plaster and gold leather and painted to remain light on the helmet, it likely dates from the early fifteenth century and comes from Mallorca, where the winged dragon was used as a symbol of the crown at the Festa de l’Estendard, commemorating Martin I’s conquest by royal decree: ‘inter signia et al.ios apparatus regales nostram empresiam de la cimera sive timbre’ (Crooke 1898, pp. 139–41, Riera 2002, p. 54; Montero 2017, pp. 100–1).

Figure 9.

Crest with a dragon, also known as king Martin’s crest. Madrid, Armería Real (D.11). Used by permission.

Over time, this symbol of a monarchy with imperial, millennialist ambitions was adopted by the municipal governments of Valencia and Mallorca, which linked it retrospectively to James I the Conqueror as the founder of the kingdoms. In 1459, it was added to the royal standard of the city of the River Turia on the eve of the Saint George festival. Peter IV’s desire to use the vibra crest on seals and heraldry following the annexation of Mallorca (1343–1344) turned the helmet with winged dragon emblem into a dynastic symbol and reference to James I, which strengthened the link to the secular fight against Islam and the prophetic destiny foretold by Arnau de Vilanova, in texts attributed to him, by Francesc Eiximenis, by Surge, vespertilio, surge (1455) and even by Jeroni Torrella in De imaginibus astrologicis (1496) at the time of Ferdinand II the Catholic (Ivars 1923, pp. 75–76).

The motif proved to be to the monarchy’s liking, as the kings of Aragon used it from the time of Martin the Humane until Ferdinand II the Catholic, despite the dynastic change of 1412. Thus, it is depicted in the late fourteenth century in the famous Gelre Armorial as the crest on coat of arms of the King of Aragon [ARRAGOEN] (Brussels, Bibliothèque royale de Belgique, ms. 15652–5, f. 62r) and in the later Armorial of the Golden Fleece (Armorial de l’Europe et de la Toison d’or, Paris, Bibliothèque national de France. Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal, Ms 4790 f. 108r, Figure 10). Jean de Roquetaillade had thought Infant Ferdinand of Aragon to be bound to defeat king Peter I of Castille wearing on his helmet the crest of the bat super galeam vespertilionem gerit insigne armorum (Aurell 1990, pp. 351–53). Later, Infant Peter of Aragon’s vision of Henry of Trastámara as the embodiment of the bat foreseen in prophecies had not been in vain (Pou [1930] 1996, pp. 531–34): both Henry and his son John have just placed aside their helmets with dragon crests and royal Castilian heraldry in the Tobed ex-voto. A vibra or dragon appeared, fighting savages and knights, at Martha of Armagnac’s royal entry into Valencia in 1377 (Archivo Municipal de Valencia: Manual de Consells, A-16, ff. 159r-164r; Ivars 1923, pp. 103–4). Among the pageantry of his royal entry in Barcelona (1397), Martin I had particularly admired the eagle and the dragon, which were subsequently borrowed for his coronation in Zaragoza in 1399, where una gran vibra molt bella (‘a great and very beautiful viper’) throwing fire was fought by a group of knights, as witnessed by the chronicle of the event (Carbonell [1547] 1997, pp. 178–90). Alfonso V the Magnanimous had been portrayed as a bat in anonymous prophecies dating from 1449 onwards (Bohigas 1920–1922, p. 43; Aurell 1994; Barca 2000). As we have seen, he incorporated the symbol into his emblems on objects like medals, manuscripts, the royal tent in 1436 and his palace in Valencia (Duran 2004, pp. 217–21). Valencian notary Dionís Guiot described a vision of a king crowned with a vibra with a bat’s wings, as the champion of the crusade following the fall of Constantinople: ‘With a glorious demeanour/I saw a king wearing a crest on his head/a rampant dragon with bat wings’ (Duran 2004, p. 166).

Figure 10.

The King of Aragon, Armorial de l’Europe et de la Toison d’or, Paris, Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal, Ms 4790 f. 108r. Used by permission.

4. Conclusions

This prophetic frenzy culminated towards the end of the century and shifted focus onto Ferdinand II the Catholic: a plausible New David figure, a Hidden King who was to restore Spain, continue the conquest of Africa and reach the Holy City. The taking of Granada and the expulsion of the Jews in 1492, support for ecclesiastical reform, the annexation of the Kingdom of Naples and military success in north Africa encouraged this association both in Castile and in Aragon, while linking up with the Pseudo-Isidorian Hispanic tradition of the repair of Spain following the Moorish invasion and the millennialist visions of Arnau de Vilanova and other authors. Zoomorphic symbols, such as the eagle and the bat, were of great service to royal propaganda. Columbus’s arrival in the New World was seen, both by him and by the Court, as a good omen for the establishment of a universal monarchy and the arrival of a millennium of peace and happiness (Milhou 1983; Duran 2001, p. 305, Wittlin 1999; Ryan 2011, pp. 172–80).

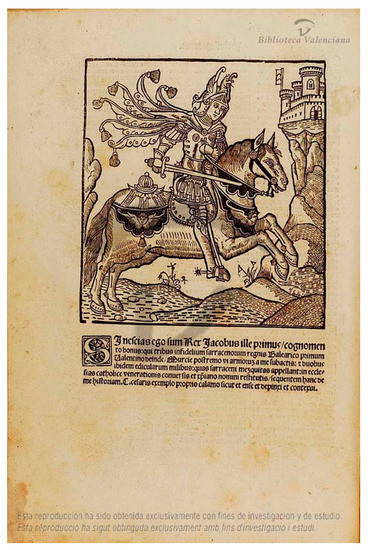

In 1515, Diego de Gumiel printed a book entitled Aureum opus, which listed the privileges granted by the monarchs of Aragon to the city of Valencia according to the records of the notary Lluís Alanyà (Alanyà 1515). There was hardly a year left before the independent dynasty of the Crown of Aragon would be abolished with the death of Ferdinand II the Catholic: a fitting time to remember the privileges enjoyed by the kingdom’s capital and the tale of its conquest, with the first-person testimony of King James I in his chronicle, included at the beginning of the book. James I was an amalgamation of the heroic figure of the conqueror and that of the legislator who had founded a new kingdom and granted it its own legal code through the furs. Both facets, that of the vanquisher of the Moors and that of the magnanimous legislator, along with the individual image of the monarch describing the feat in the first person and the institutional figure of the founder of the kingdom, were captured through the only two images printed on the book. On the frontispiece, the monarchy is represented with royal heraldry, meaning the Aragonese coat of arms with pallets below a dragon crest, while on folio 6v, the king figure is riding and gripping a sword, with full armour and a winged dragon crest, in front of a castle on a rock (Serra 2018, pp. 144–45); Figure 11. It is no coincidence that the same etching would be used for the novel Floriseo later that year and would be recreated by other printers in Seville and Toledo for chivalric romances (Bernal 1516; Guijarro 2002, pp. 205–23). The adventures of the protagonist of Floriseo were reminiscent of those captured in the more famous Tirant lo Blanch, which Cervantes considered the best book in the world: a Christian knight freeing the eastern empire and leading the crusade on successful campaigns until reaching India (Rubiera 1993; Hauf 1995, pp. 129–32).

Figure 11.

King James I in Lluís Alanyà, Aureum Opus regalium privilegiorum civitatis et regni Valentie cum historia christianissimi regis Jacobi ipsius primi conquistatoris, Valencia, 1515, f. 6v (Valencia, Biblioteca Valenciana). Used by permission.

These images, valid for representing both a fictional hero and messianic hopes invested in the monarchy towards 1500, were used subversively in Xàtiva in 1522. Without a specific, individual identity, they left the door open for an adventurer to associate himself with the Hidden King and ride the wave of expectation from all those who aspired to a renewal of the world they knew, to the definitive conversion of the Jews and Muslims, to the reconquest of Jerusalem and to the establishment of the millennium of the eternal gospel. The appearance of the Hidden King was to be linked subversively to the Aragonese dynasty, which held on to those prophetic hopes, but did not need an epiphany in a sacred place, let alone a formal coronation: his thundering image was forged in battles from which he emerged without a scratch, despite taking on fearsome enemies. Only one image of this and other individuals who hoped to take on the same role survived: the negative one broadcast by his enemies. However, his emergence could not remain independent of all the other images that suggested that a king of Aragon could embody that World Emperor heralded by prophets and visionaries, described in books and in the streets, glorified in royal entries and coronations, and captured through images of power and glory.

The monarchs of the Crown of Aragon had used the figurative arts as a means of communication and dynastic propaganda through various media (Serrano 2015a). However, while making them versatile and easy to update over time, the generic nature of many dynastic, triumphal and foundational images probably reduced the control the Court held over them: heraldry, dynastic and individual emblems, and generic and conventional portraits were easily used for exaltation purposes through rhetorical persuasion, but could possibly be adapted to subversive readings as well. These images effortlessly crossed the uncertain, permeable boundaries between popular mentality and Court culture, and the possibility of reproducing and disseminating them through etchings made them even more difficult to control.

The scarcity and problematic nature of figurative images of royal epiphanies is striking. These events had their own specific setting at the coronation in Zaragoza (Serrano 2012), the royal entry and the pledge to the laws and privileges: ceremonies that stirred up some discomfort among the Aragonese monarchs, as they compromised their authority through institutional consensus and agreement. Imagining the king victorious on the battlefield, against the infidels or any other enemy, and with the aura of a glorious destiny, blessed by divine selection foretold by prophets and visionaries instead of a ceremony of unction and consecration, was a unique artistic route inspired by the Court and promoted by urban oligarchies, but was not free from danger when someone took on these millennialist expectations.

The power vacuum created when Ferdinand II the Catholic died is evident through the subsequent lack of iconographic representation of the Hidden King or Emperor of the Last Days, which appeared in other contemporary European contexts (Guerrini 1997; Vassilieva-Codognet 2012). The figure was unable to survive the harsh oppression of the Revolt of the Germanias and the subsequent ‘encubertismo’ (Pérez García 2007, pp. 212–22), and Charles V and the humanists of the Imperial Court opted for other kinds of images and values. When the piece by Brother Juan Unay or Joan Alamany, Tractat de la venguda de l’Antichrist was printed again in Valencia in 1520, the figure of the New David, the Emperor of the Last Days and now the Hidden King, tailor-made for Ferdinand II the Catholic, did not seem suitable for a distant king who was reluctant to swear an oath to the furs of the Kingdom of Valencia, slow to defend his Valencian subjects when they felt in danger of a combined attack from the local Mudejars, Barbary pirates or even the Turk, and alien to the text’s strongly antisemitic message (Ramos 1997; Duran and Requesens 1997; Toro 2003). This material, however, could be transformed into subversive ideas in the hands of adventurers from Castile, who were ready to put themselves forward as heirs of the Trastámara dynasty and the real embodiments of the Hidden King, which is exactly what happened in Xàtiva in 1522 (Pérez García and Catalá 2000).

Funding

This research was carried out in the framework of the research project “Memory, Image and Conflict in Renaissance Art and Architecture: Germanias revolt in Valencia”and was funded by the Spanish Government MINECO/AEI/FEDER, UE grant number HAR2017-88707-P.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges the most valuable support for the English translation of this article offered by Bethan Cunningham. Oscar Calvé offered helpful suggestions and incisive observations.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Ávila, Aguilar, and Josep Antoni. 2007. Percutiebat lethaliter cauda gallos. Elements profètics en les cròniques de les vespres sicilianes. Llengua i literatura 18: 403–39. [Google Scholar]

- Alanyà, Lluís. 1515. Aureum Opus Regalium Privilegiorum Civitatis et Regni Valentie cum Historia Christianissimi Regis Jacobi Ipsius Primi Conquistatoris. Valencia: Diego Gumiel. [Google Scholar]

- Alcoy, Rosa, and Jacobo Vidal. 2015. El retaule de la Transfiguració de la catedral de Tortosa, obra contractada per Rafael Vergós i Pere Alemany. Matèria 9: 61–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, Paul J. 1978. The Medieval Legend of the Last Roman Emperor and Its Messianic Origin. Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 41: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcelus, Ulibarrena Juana María. 1991. Estudio introductorio. In Visionarios, Beguinos y Fraticelos Catalanes (Siglos XIII–XV). Madrid: Colegio Cardenal Cisneros. [Google Scholar]

- Aurell, Martin. 1990. Prophétie et messianisme politique. La péninsule Ibérique au miroir du Liber ostensor de Jean de Roquetaillade. Mélanges de l’Ecole Française de Rome. Moyen-Age 102: 317–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aurell, Martin. 1992. Eschatologie, spiritualité et politique dans la confederation catalano-aragonaise (1282–1412). In Fin du Monde et Signes des Temps. Visionnaires et Prophètes en France Mérdionale (fin XIIIe-Début XVe Siècle). Cahiers de Fanjeaux 27. Toulouse: Privat, pp. 191–235. [Google Scholar]

- Aurell, Martin. 1994. La Fin du monde, l’Enfer et le Roi. Revue Mabillon 5: 143–77. [Google Scholar]

- Aurell, Martin. 1997. Messianisme royal de la Couronne d’Aragon. Annales. Histoire Sciences Sociales 52: 119–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barca, Daniele. 2000. Alfonso il Magnanimo e la tradizione dell’immaginario profetico catalano. In XVI Congresso Internazionale di Storia Della Corona d’Aragona. Celebrazioni Alfonsine (Napoli 1997). Edited by Guido d’Agostino and Giulia Buffardi. 2 vols. Napoli: Paparo, pp. 1283–91. [Google Scholar]

- Barrientos, Lima Marisol. 2009. La representació del monarca en l’Aureum Opus d’Alzira; tipologies, models i particularitats. In El Trecento en Obres: Art de Catalunya i Art d’Europa al Segle XIV. Edited by Rosa Alcoy. Barcelona: Universitat de Barcelona, pp. 425–34. [Google Scholar]

- Baschet, Jérôme, and Pierre-Oliver Dittmar. 2015. Les images dans l’Occident médiéval. Turnhout: Brepols. [Google Scholar]

- Bercé, Yves-Marie. 1990. Le Roi Caché. Sauveurs et Imposteurs. Mythes Politiques Populaires Dans l’Europe Moderne. Paris: Fayard. [Google Scholar]

- Bernal, Fernando. 1516. Floriseo del Desierto. Valencia: Diego Gumiel. [Google Scholar]

- Bohigas, Pere. 1982. Prediccions i profecies en les obres de fra Francesc Eiximenis. In Aportació a L’estudi de la Literatura Catalana. Barcelona: Abadia de Montserrat, pp. 94–115. First Published 1928. [Google Scholar]

- Bohigas, Pere. 1920–1922. Profecies catalanes dels segles XIV i XV. Assaig bibliogràfic. Butlletí de la Biblioteca de Catalunya 6: 24–48. [Google Scholar]

- Bohigas, Pere. 1928–1932. Profecies de Merlí. Altres profecies contingudes en manuscrits catalans. Butlletí de la Biblioteca de Catalunya 8: 253–79. [Google Scholar]

- Bolzoni, Lina. 2002. La rete delle immaggini: predicazione in volgare dalle origini a Bernardino da Siena. Torino: Einaudi. [Google Scholar]

- Botley, Paul. 2004. Giannozzo Manetti, Alfonso of Aragon and Pompey the Great: A crusading document of 1455. Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 67: 129–56. [Google Scholar]

- Calvé, Mascarell Óscar. 2016. La Configuración de la Imagen de San Vicente Ferrer en el Siglo XV. Ph.D. Thesis, Universitat de València, Valencia, Spain. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10550/54943 (accessed on 22 October 2019).

- Calvé, Mascarell Óscar. 2019. L’entramès de Mestre Vicent: resplandor de la autoridad del predicador. Anuario de Estudios Medievales 49: 45–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbonell, Pere Miquel. 1997. Cròniques d’Espanya. Edited by Agustí Alcoberro. Barcelona: Barcino. First Published 1547. [Google Scholar]

- Cárcel, Ortí María Milagros, and Marsilla Juan Vicente García. 2013. Documents de la Pintura Valenciana Medieval i Moderna IV: Llibre de L’entrada de Ferran d’Antequera. Valencia: Universitat de València. [Google Scholar]

- Carruthers, Mary. 1990. The Book of Memory. A Study of Memory in Medieval Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cawsey, Suzanne F. 2002. Kingship and Propaganda: Royal Eloquence and the Crown of Aragon c. 1200–450. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cohn, Norman. 1970. The Pursuit of the Millenium. Revolutionary Milleniarians and Mystical Anarchists of the Middle Ages. New York: Oxford University Press. First Published 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Corrao, Pietro. 1994. Celebrazione dinastica e costruzione del consenso nella Corona d’Aragona. In Le Forme Della Propaganda Política nel Due e nel Trecento. Relazioni Tenute al Convegno Internazionale di Trieste (2–5 Marzo 1993). Rome: Ecole Française de Rome, pp. 133–56. [Google Scholar]

- Crispi, i Canton Marta. 1996. La verónica de Madona Santa Maria i la processó de la Puríssima organitzada per Martí l’Humà. Locus Amoenus 2: 85–101. [Google Scholar]

- Crooke, y Navarrot Juan Bautista. 1898. Catálogo Histórico-Descriptivo de la Real Armería de Madrid. Madrid: Hauser y Manet. [Google Scholar]

- Daileader, Philip. 2016. Saint Vincent Ferrer, His World and Life: Religion and Society in Late Medieval Europe. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Deurbergue, Maxime. 2012. The Visual Liturgy. Altarpiece Painting and Valencian Culture (1442–1519). Turnhout: Brepols. [Google Scholar]

- Diago, Francisco. 1946. Apuntamientos Recogidos por el P. M. Fr. Francisco Diago, O. P. Para Continuar los Anales del Reyno de Valencia Desde el Rey Pedro III Hasta Felipe II. Edited by José María Garganta. Valencia: Acción Bibliográfica Valenciana, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz, Borrás Andrés. 1993. Los Orígenes de la Piratería Islámica en Valencia: La Ofensiva Musulmana Trecentista y la Reacción Cristiana. Barcelona: CSIC-Institució Milà i Fontanals. [Google Scholar]

- Didi-Huberman, Georges. 2000. Devant le Temps: Histoire de l’Art et Anachronisme des Images. Paris: Minuit. [Google Scholar]

- Duran, Eulàlia. 1982. Les Germanies als Països Catalans. Barcelona: Curial. [Google Scholar]

- Duran, Grau Eulàlia. 2011. El mil lenarisme al servei del poder i del contrapoder. In De la unión de coronas al Imperio de Carlos V. Congreso Internacional (Barcelona, 21–23 de febrero de 2000). Edited by Ernest Belenguer. Madrid: Sociedad Estatal para la conmemoración de los Centenarios de Felipe II y Carlos V, vol. 2, pp. 293–308. [Google Scholar]

- Duran, Eulàlia. 2004. Estudis Sobre Cultura Catalana al Renaixement. València: Tres i Quatre. [Google Scholar]

- Duran, Eulàlia, and Joan Requesens. 1997. Profecia i Poder al Renaixement. València: Tres i Quatre. [Google Scholar]

- Eiximenis, Francesc. 1983. De Sant Miquel Arcángel. El Quint Tractat del ‘Libre Dels Àngels’. Edited by Curt Wittlin. Barcelona: Curial. First Published 1392. [Google Scholar]

- Escandell, Proust Isabel. 2012. The Illuminated Codex Book of Franchises and Privileges of the Kingdom of Majorca (Arxiu del Regne de Mallorca, cod.1): Portraits of the King under His Subjects’ Gaze. Ikon Journal of Iconographic Studies 5: 331–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Español, Bertran Francesca. 1993. Pinturas murales del castillo de Alcañiz. In El Cerro de Pui-Pinós y el Castillo de Alcañiz. Una Presencia Histórica; Alcañiz: Ayuntamiento de Alcañiz, pp. 30–32. [Google Scholar]

- Español, Bertran Francesca. 1998. Ecos artísticos aviñoneses en la Corona de Aragón: la capilla de los Ángeles del Palacio Papal. In El Mediterráneo y el Arte Español. Actas del XI Congreso del Comité Español de Historia del Arte. Valencia, 1996. Valencia: Generalitat Valenciana, pp. 58–68. [Google Scholar]

- Español, Francesca. 2002. Els Escenaris del Rei: Art i Monarquia a la Corona d’Aragó. Manresa: Angle. [Google Scholar]